Renewing a Prophetic Mysticism for Teaching Children Justly: A Lasallian Provocation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Why a Prophetic Mysticism to Teach Children Justly?

2.1. Preferential Option for Children in Christian Mission

- (i)

- Ethic of Justice for Children

Children have become a new measure of justice for the church ad intra, a measure that will determine our credibility to speak on matters of justice for children, born and unborn, in a world where poor children continue to suffer from having too much to bear and from given too little to develop properly.(ibid., p. 1030)

Jesus did not just teach how to make an adult world kinder and more just for children; he taught the arrival of a social world in part defined by and organized around children.(p. 60)

- (ii)

- Relational agency of children

2.2. Implications for Catholic Education

An adequate vision of the common good must account for the vulnerabilities and the possibilities of children and childhood, and bring children in from the margins to the center to insure that our assumptions about the “common” good are not distorted by the perspective of those in positions of power and privilege. With children’s experiences at the center, the common good of society allows for children as individuals, as members of families and other communities to flourish.

3. The Lasallian Charism

3.1. Teaching Children Justly: A Commitment to a Preferential Option for Children

God is so good that, having created us, he wills that all of us come to the knowledge of the truth. This truth is God himself and what he has desired to reveal to us through Jesus Christ, through the holy apostles, and through his Church. This is why God wills all people to be instructed, so that their minds may be enlightened by the light of faith.(M. 193.1)

The necessity of this Institute is very great, because the working class and the poor, being usually little instructed and occupied all day in gaining a livelihood for themselves and their children, cannot give them the instruction they need and a respectable Christian education. nor a suitable education. It was to procure this advantage for the children of the working class and of the poor that the Christian Schools were established.(para. 4–5, cited in De La Salle 2002)

The thesis of this pastoral letter is that the situation of poor children in today’s world is an unspeakable scandal that our Lasallian charism invites us to make solidarity with neglected, abandoned, marginalized, and exploited children a particular focus for our mission.

Our Rule concisely and poignantly links De La Salle’s progressive awareness of the situation of poor children with the origin and development of the Institute. As he became aware, by God’s grace, of the human and spiritual distress of ‘the children of artisans and of the poor,’ their neglect and abandonment moved him profoundly.(Johnston 2016, p. 457, emphasis his)

3.2. Prophetic Mysticism That Grounds Teaching as Incarnational Presence

Recognize Jesus beneath the poor rags of the child whom you have to instruct. Adore him in them … May faith lead you to [instruct] with affection and zeal, because these children are the members of Jesus Christ.(M. 96.3)

What holy audacity in our Magi, to enter the capital and make their way even to Herod’s throne! They feared nothing because the faith inspired them and the grandeur of [Christ] whom they were seeking caused them to forget and even to scorn all human considerations, considering the king to whom they were speaking to be infinitely beneath the one announced to them by the star.(M. 96.2)

3.3. Faith and Zeal as a Dynamic of Lasallian Prophetic Mysticism

Let it be clear, then, in all your conduct towards the children who are entrusted to you that you look upon yourselves as ministers of God, carrying out your ministry with love and a sincere and true zeal, accepting with much patience the difficulties you have to suffer, willing to be despised by men to be persecuted, even to give your life for Jesus in the fulfillment of your ministry.(M. 201.1)

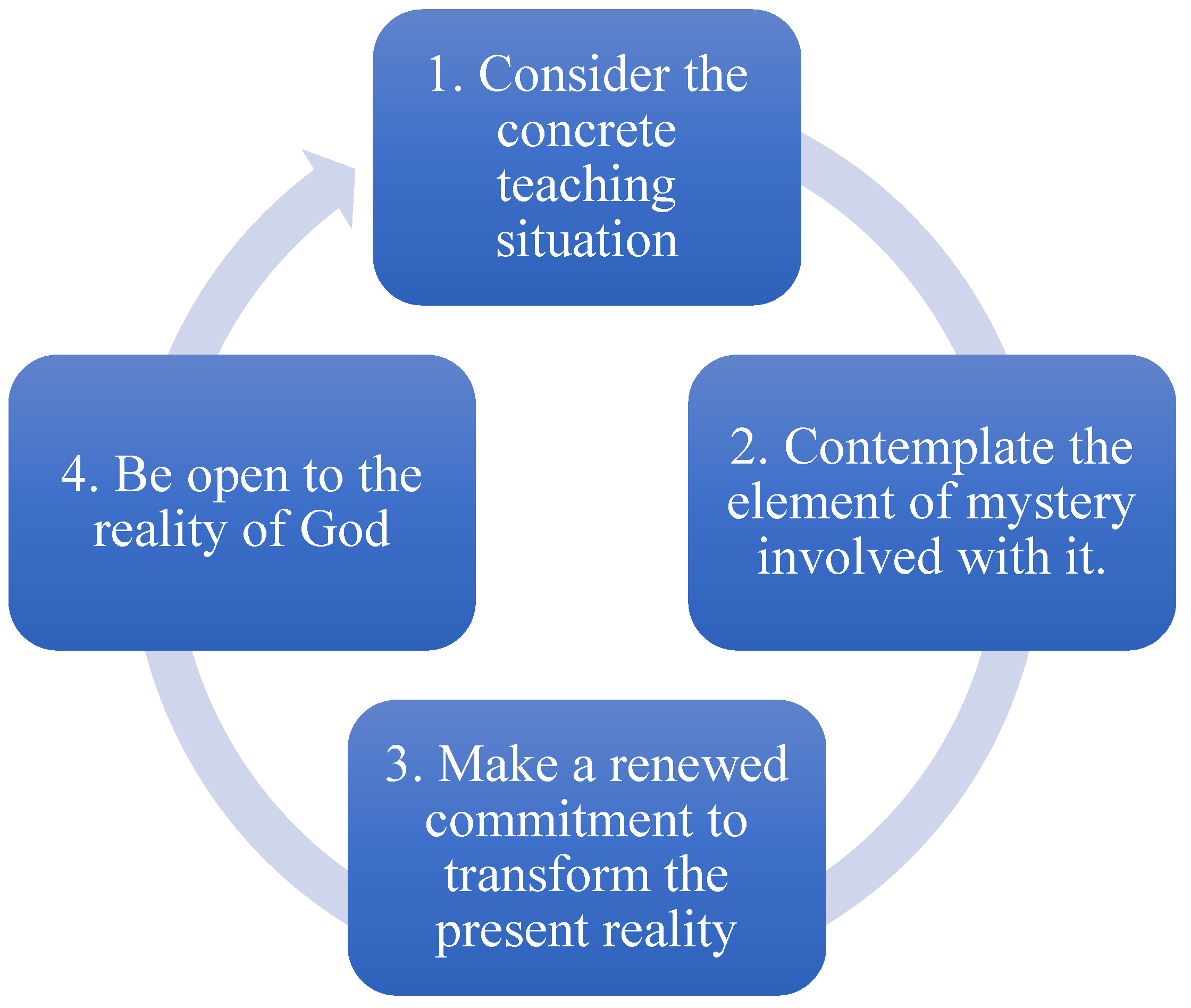

4. Toward a Praxis of Socially Engaged Contemplation

Look at the life you are living; be aware of the distressing situation of the youngsters that God has placed in your path; use that as a measure of what is at stake in your teaching service.(ibid., p. 225)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Meditations is a reference to De La Salle (1994). Hereafter cited in text as M., followed by the numbering used in this text. |

| 2 | |

| 3 |

References

- Berryman, Jerome W. 2009. Children and the Theologians: Clearing the Way for Grace. New York: Morehouse Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman, Jerome W. 2017. Becoming Like a Child: The Curiosity of Maturity beyond the Norm. New York: Church Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bingemer, Maria C. L. 2020. Mystical Theology in Contemporary Perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Mystical Theology. Edited by Edward Howells and Mark Allen McIntosh. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brothers of the Christian Schools. 2020. Declaration on the Lasallian Educational Mission: Challenges, Convictions and Hopes. Rome: Generalate. [Google Scholar]

- Bunge, Marcia J. 2006a. The Child, Religion, and the Academy: Developing Robust Theological and Religious Understandings of Children and Childhood. The Journal of Religion 86: 549–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, Marcia J. 2006b. The Dignity and Complexity of Children: Constructing Christian Theologies of Childhood. In Nurturing Child and Adolescent Spirituality: Perspectives from the World’s Religious Traditions. Edited by Karen Marie Yust, Aostre N. Johnson, Sandy Eisenberg Sasso and Eugene C. Roehlkepartain. Lanham: Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bunge, Marcia J., ed. 2001. The Child in Christian Thought. Grand Rapids and Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan, Kathleen A. 2017. Callings over a Lifetime: In Relationship through the Body, over Time, and for Community. In Calling All Years Good: Christian Vocation throughout Life’s Seasons. Edited by Kathleen A. Cahalan and Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, pp. 12–32. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, Miguel. 1994. Introduction to Meditations for the Time of Retreat. In Meditations by John Baptist de La Salle. Translated by Richard Arnandez, and Augustine Loes. Edited by Augustine Loes and Francis Heuther. Landover: Lasallian Publications, pp. 411–32. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, Miguel. 2012. Fidelity to the Movement of the Spirit: Criteria for Discernment [2007]. AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 3. Available online: https://axis.smumn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/46-206-1-PB.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Carter, Warren. 2002. The Magi and the Star We Follow. The Other Side 38: 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1982. Lay Catholics in Schools: Witnesses to Faith. Rome: Vatican. [Google Scholar]

- De La Salle, John Baptist. 1994. Meditations by John Baptist de La Salle. Translated by Richard Arnandez, and Augustine Loes. Edited by Augustine Loes and Francis Heuther. Landover: Lasallian Publications. [Google Scholar]

- De La Salle, John Baptist. 2002. Rule and Foundational Documents. Translated and Edited by Augustine Loes, and Ronald Isetti. Landover: Lasallian Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dillen, Annemie, and Didier Pollefeyt, eds. 2010. Children’s Voices: Children’s Perspectives in Ethics, Theology and Religious Education. Leuven: Utigeveru Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Earl, Patricia Helene. 2007. Challenges to Faith Formation in Contemporary Catholic Schooling in the USA: Problem and Response. In International Handbook of Catholic Education: Challenges for School Systems in the 21st Century. Edited by Gerald Grace and Joseph O’Keefe. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, Robert J. 2001. The Mystical and the Prophetic: Dimensions of Christian Existence. In Christianity and the Mystical. Edited by Andrew Louth. London: The Way, pp. 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, Edward A. 1951. La Salle: Patron of All Teachers. Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gittins, Anthony J. 2002. A Presence that Disturbs: A Call to Radical Discipleship. Liguori: Liguori/Triumph. [Google Scholar]

- Goussin, Jacques. 2003. The Mission of Human and Christian Education: The Gospel Journey of John Baptist de La Salle. Translated by Finian Allman, Christian Moe, and Julian Watson. Edited by Gerard Rummery. Melbourne: Lasallian Education Services. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, Gerald, and Joseph O’Keefe. 2007. Catholic schools facing the challenges of the 21st century: An overview. In International Handbook of Catholic Education: Challenges for School Systems in the 21st Century. Edited by Gerald Grace and Joseph O’Keefe. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gundry-Volf, Judith M. 2001. The Least and the Greatest: Children in the New Testament. In The Child in Christian Thought. Edited by Marcia J. Bunge. Grand Rapids and Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hengemüle, Edgard. 2016. Lasallian Education: What Kind of Education is It? Translated by Rose M. Beal. Edited by William Mann. Winona: Institute for Lasallian Studies of Saint Mary’s University. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, Brendan, Karen-Marie Yust, and Cathy Ota. 2010. Editorial: Defining childhood at the beginning of the twenty-first century: Children as agents. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 15: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Allison, and Alan Prout, eds. 1997. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood: Contemporary Issues in the Sociology of Childhood, 2nd ed. London: Falmer. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, David H. 2005. Graced Vulnerability: A Theology of Childhood. Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, John. 2016. On the Defense of Children, the Reign of God, and the Lasallian Mission [January 1, 1999]. The Pastoral Letters of Br. John Johnston, FSC: 1986–2000. Napa: Lasallian Resource Centre, pp. 443–80. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, Carl, Jeffrey Calligan, and Jeffrey Gros, eds. 2004. John Baptist de La Salle: The Spirituality of Christian Education. New York: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Konz, D. J. 2014. The Many and the One: Theology, Mission and Child in Historical Perspective. In Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives. Edited by Bill Prevette, Keith J. White, C. Rosalee Velloso Ewell and D. J. Konz. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Bernard J. 2004. The Beating of Great Wings: A Worldly Spirituality for Active, Apostolic Communities. Mystic: Twenty Third Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon, John. 2009. Transmission of the Charism: A Major Challenge for Catholic Education. International Studies in Catholic Education 1: 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydon, John. 2021. Professor Gerald Grace and the concept of ‘spiritual capital’: Reflections on its value and suggestions for its future developments. In New Thinking, New Scholarship and New Research in Catholic Education: Responses to the Work of Professor Gerald Grace. Edited by Sean Whittle. London: Routledge, pp. 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Marquiegui, Antón. 2018. MEL Bulletin No. 52: Contribution of John Baptist de La Salle (1651–1719) to the Esteem for the Teaching Profession. Rome: Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools Secretariat for Association and Mission. [Google Scholar]

- McAleese, Mary. 2019. Children’s Rights and Obligations in Canon Law: The Christening Contract. Boston: Brill Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Marie. 2000. Spirituality in a Postmodern Era. In The Blackwell Reader in Pastoral and Practical Theology. Edited by James Woodward and Stephen Pattison. Malden: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 192–206. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-McLemore, Bonnie J. 2003. Let the Children Come: Reimagining Childhood from a Christian Perspective. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-McLemore, Bonnie J. 2017. Childhood: The (Often Hidden yet Lively) Vocational Life of Children. In Calling All Years Good: Christian Vocation throughout Life’s Seasons. Edited by Kathleen A. Cahalan and Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, pp. 38–62. [Google Scholar]

- Oswell, David. 2013. The Agency of Children: From Family to Global Human Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Alfred K. M. 2021. Whose Child is This? Uncovering a Lasallian Anthropology of Belonging and its Implications for Educating Toward the Human Flourishing of Children in Faith. Journal of Religious Education 69: 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevette, Bill, Keith J. White, C. Rosalee Velloso Ewell, and D. J. Konz, eds. 2014. Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, Ethna. 2014. Barely Visible: The Child in Catholic Social Teaching. Heythrop Journal 55: 1021–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, Mary M. Doyle. 2009. Children, Consumerism and the Common Good. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Salm, Luke. 2017. The Lasallian Educator in a Shared Mission. AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 8: 145–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage, Michel. 1999. The Gospel Journey of John Baptist de La Salle (1651–1719) [1984]. In Spirituality in the Time of John Baptist de La Salle. Translated by Luke Salm. Edited by Robert C. Berger. Landover: Lasallian Publications, pp. 221–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Jean-Louis. 2006. Discovering, living, sharing the gift of God. In Lasallian Studies No. 13: The Lasallian Charism. Edited by the International Council for Lasallian Studies. Translated by Aidan Patrick Marron. Rome: Brothers of the Christian Schools Generalate, pp. 49–180. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrake, Philip. 1991. Spirituality and History: Questions of Interpretation and Method. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrake, Philip. 2005. Christian Spirituality as a Way of Living Publicly: A Dialectic of the Mystical and Prophetic. In Minding the Spirit: The Study of Christian Spirituality. Edited by Elizabeth A. Dreyer and Mark S. Burrows. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, pp. 282–98. [Google Scholar]

- Strhan, Anna, Stephen G. Parker, and Susan Ridgely, eds. 2017. The Bloomsbury Reader in Religion and Childhood. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, Douglas. 1992. On the Suffering and Rights of Children: Toward a Theology of Childhood Liberation. Cross Currents 42: 149–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, John. 2010a. Childism and the Ethics of Responsibility. In Children’s Voices: Children’s Perspectives in Ethics, Theology and Religious Education. Edited by Annemie Dillen and Didier Pollefeyt. Leuven: Uitgeveru Peeters, pp. 237–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, John. 2010b. Ethics in Light of Childhood. Washington: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, John. 2017. Children’s Rights: Today’s Global Challenge. New York: Rowan & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, Karen. 2015. Childhood in a Global Perspective. Malden: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Werpehowski, William. 2012. Human Dignity and Social Responsibility: Catholic Social Thought on Children. In Children, Adults, and Shared Responsibilities: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Perspectives. Edited by Marcia J. Bunge. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, Todd D., and Tobias Winwright. 1997. Children: An Undeveloped Theme in Catholic Teaching. In The Challenge of Global Stewardship: Roman Catholic Responses. Edited by Maura A. Ryan and Todd David Whitmore. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 161–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Gregory. 2017. The Lasallian Educator according to John Baptist de La Salle. AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 8: 79–94. [Google Scholar]

| Four-Fold Rhythm in Lasallian Mystical Realism (Sauvage 1999) | Praxis of Socially Engaged Contemplation |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, A.K.M. Renewing a Prophetic Mysticism for Teaching Children Justly: A Lasallian Provocation. Religions 2022, 13, 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100893

Pang AKM. Renewing a Prophetic Mysticism for Teaching Children Justly: A Lasallian Provocation. Religions. 2022; 13(10):893. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100893

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Alfred Kah Meng. 2022. "Renewing a Prophetic Mysticism for Teaching Children Justly: A Lasallian Provocation" Religions 13, no. 10: 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100893

APA StylePang, A. K. M. (2022). Renewing a Prophetic Mysticism for Teaching Children Justly: A Lasallian Provocation. Religions, 13(10), 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100893