Abstract

This paper focuses on ordination procedures specific to women in Chinese Buddhism, and on the positions adopted by bhikṣuṇīs regarding the procedures’ asymmetrical nature in contemporary China. Dual ordinations, according to which aspiring bhikṣuṇīs must present themselves in front of both an assembly of fully ordained nuns and of monks in order to be “properly” ordained, were restored by Longlian (隆莲 1909–2006) in 1982. Śikṣamāṇā ordinations, which postulate that women should train for an additional two years before receiving full ordination when their male counterparts do not have to, have also become increasingly common since the 1980s. Based on fieldwork conducted between 2015 and today, both on-site and online, this paper asks whether asymmetry should be considered similar to subordination with regard to ordination procedures. It looks into Rurui’s (如瑞, 1957–) position on the matter, as Longlian’s student and one of the most influential bhikṣuṇī of her generation. While recent survey data will be useful in addressing the issue of representation, qualitative data will question the role of vertical networks in perpetuating a teacher’s legacy, ultimately leaving us to wonder if asymmetry might not be actively sought after by contemporary Chinese Buddhist bhikṣuṇīs in order to improve their status.

1. Introduction

Chinese Buddhist bhikṣuṇīs1 often seem to hold a privileged position compared to their counterparts in other Asian countries. This is due to the fact that they have access to full ordination. Working specifically on the largest and most influential bhikṣuṇī temple in mainland China, Mount Wutai’s Pushou temple (五台山普寿寺), asymmetry—understood here as a dissimilarity in bhikṣus’ and bhikṣuṇīs’ situations—was not a primary concern of mine. Its residents were indeed accomplished, learned, and praised by bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs alike, ostensibly reaching for gender equality through higher education, which at the time did not warrant further investigation. However, they also promoted distinct ordination procedures for female monastics, which called into question that ideal image and prompted me to reexamine asymmetry in the context of Chinese Buddhist ordination procedures. This paper was initially conceived as part of a larger one that would give the reader a comprehensive overview of ordination issues faced by Chinese Buddhist bhikṣuṇīs in the course of the 20th century2. The first part, which now appears as a separate paper in this Special Issue on “Gender Asymmetry and Nuns’ Agency in the Asian Buddhist Traditions”, mainly dealt with concerns from the Republican era. It centered on the eminent bhikṣuṇī Longlian’s (隆莲 1909–2006) role in promoting and passing on what she deemed to be orthodox procedures—however asymmetrical (Bianchi 2022). This paper constitutes a second part that focuses on Longlian’s and other masters’ legacy in contemporary China. By looking into one of her students from the new generation, Rurui (如瑞, 1957–), who is currently leading the Pushou temple, I wished to investigate the role of vertical networks in influencing one’s position regarding female monastics’ ordinations, and to analyze that position.

When dealing with the issue of ordination in Buddhism, one can hardly miss the inherent asymmetry. Even though female Chinese Buddhist monastics have access to full ordination (juzu jie 具 足 戒 or dajie 大 戒), which is not the case everywhere in Asia, they still have to go through procedures that are different from those undergone by male monastics. Dual ordination (erbuseng jie 二部僧戒) is one such procedure. The Vinaya, a body of texts specifically focused on monastic discipline, indeed states that to receive full ordination, a female candidate should present herself in front of an assembly of ten bhikṣuṇīs and ten bhikṣus in succession, a rule that does not apply to male candidates (Heirman 2002, pp. 75–79). Dual ordinations were seldom held until very recently, in 1982, when the bhikṣuṇī Longlian restored and promoted this procedure, together with her colleague and friend, the bhikṣuṇī Tongyuan (通愿 1913–1991)3. It has since been included in official regulations in 2000, and is now part of the standardized triple-platform ordination system (santan dajie 三坛大戒). This particular system is currently used during officially sanctioned ceremonies, and consists of conferring śrāmaṇera or śrāmaṇerī (male or female “novices”), full and bodhisattva ordinations at one place and time4. What this translates to in the Chinese Buddhist tradition is that both men and women shall first take the ten śrāmaṇera or śrāmaṇerī precepts (shami jie 沙弥戒 or shamini jie 沙弥尼戒)5, then the 250 bhikṣu precepts (biqiu jie 比丘戒), or 348 bhikṣuṇī precepts (biqiuni jie 比丘尼戒)6 according to the dual ordination procedure, and all shall finally take the bodhisattva precepts (pusa jie 菩萨戒)7. Another procedure that this paper will address is the Śikṣamāṇā ordination (shichani jie 式叉尼戒)8, which marks the beginning of a probationary period of two years only applicable to women. This specific period is first mentioned in the gurudharma, a set of eight rules specific to women that the Buddha supposedly enacted as a condition to create the bhikṣuṇīs’ order9. The Śikṣamāṇā was never a common figure in Chinese Buddhist nunneries until the 20th century (Heirman 2008, pp. 133–34). Although this figure is not yet part of the official system, implementing this two-year extra-study period is slowly becoming customary for Chinese Buddhist nunneries.

Consequently, Chinese Buddhist bhikṣuṇīs or aspiring bhikṣuṇīs have to answer to both the bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs’ communities, take more precepts than their male counterparts, and study longer. These are only some of the forms of asymmetry in Chinese Buddhism. To understand how these asymmetries effect contemporary female Chinese Buddhist monastics, I ask in this paper: What meaning does this term have in this particular context? Why would Chinese Buddhist bhikṣuṇīs promote these asymmetrical procedures? Although asymmetry is often considered to be synonymous with inferiority or subordination in patriarchal societies, as evidenced by most cases introduced in this Special Issue, it can also be understood in the literal sense of two things being different from one another, being unequal, or imbalanced. In this paper, I argue that there is indeed asymmetry in the Chinese Buddhist tradition, but that asymmetry can mean something other than subordination when actively sought after by bhikṣuṇīs themselves. Longlian’s view suggest a different definition of this concept, as her advocating for distinct ordination procedures meant higher status and independence. What is Rurui’s relationship with that legacy? How are the lives of contemporary bhikṣuṇīs influenced by their positions? The first section of this paper will be devoted to actualizing ordination numbers to give asymmetry a quantitative framework, as well as a qualitative one, and make known one of the crucial challenges faced by Chinese Buddhist bhikṣuṇīs in the past few decades. Then, I will dive into the influential role of vertical networks in perpetuating the teachers’ views on ordination procedures for female monastics, and specifically examine Rurui’s ties to Longlian and Tongyuan. I will finally address Rurui’s position on procedures specific to female monastics, such as dual or śikṣamāṇā ordinations, and the general model she wishes to set for the next generation of Chinese bhikṣuṇīs.

2. Asymmetry in Numbers: A Quantitative Approach to Ordination

Since Deng Xiaoping’s (邓小平, 1904–1997) reforms of 1978 (gaige kaifang 改革开放), Buddhism has slowly been recovering from the eradication period of the Cultural Revolution. Official numbers from 1997 show that there were approximately 70,000 members of the Chinese Buddhist saṅgha at the time, including bhikṣus, bhikṣuṇīs, and śrāmaṇera/śrāmaṇerī, living in 8000 temples, while in 2006 there were 100,000 members of the saṅgha living in 15,000 temples (Ji 2009, pp. 10–12). More recently, in 2012, the Buddhist Association of China (BAC, Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 中国佛教协会) estimated 100,000 Chinese Buddhist saṅgha members in 28,000 temples. In 2014, the former State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA, Guojia zongjiao shiwuju 国家宗教事务局) maintained that the Chinese Buddhist clergy amounted to an even lower 72,000 members (Wenzel-Teuber 2015, p. 28), and that the number of Chinese Buddhist sites reached a total of 28,247 in early 2015 (Guojia zongjiao shiwuju 2020)10. While these somewhat growing figures indicate some form of revitalization for Chinese Buddhist monasticism since the 1980s, at least concerning the building and rebuilding of Chinese Buddhist sites, they are still far from reaching pre-1949 numbers. As a matter of fact, when comparing official data published by the Buddhist Chinese Association (BCA, Zhongguo fojiao hui 中国佛教会)11 in the 1930s (Welch 1967, pp. 411–20) and by the BAC in 2012, one can see that the saṅgha has only recuperated 13.6% of the numbers reported in the 1930s. However, it must be noted that numbers published by official institutions are more likely to show stagnation than the exponential increase of the Buddhist clergy to promote atheistic values. There even seems to be a decrease in the number of śrāmaṇera, and in student enrollment at the Buddhist Institute of China (Zhongguo foxueyuan 中国佛学院) since the year 2000 (Gildow 2020, pp. 21–24). Although these numbers testify to some quantitative reality for Chinese Buddhism, as well as signify the goals set by the governing authorities, they still do not include unofficial members of the clergy or unregistered temples, do not set apart śrāmaṇera/śrāmaṇerī and fully ordained monks and nuns, and do not provide reliable information on the proportion of śrāmaṇerī and bhikṣuṇīs. Thus, they must be considered relatively inadequate in representing the current development of lived monastic Buddhism, especially that of Buddhist bhikṣuṇīs, in mainland China.

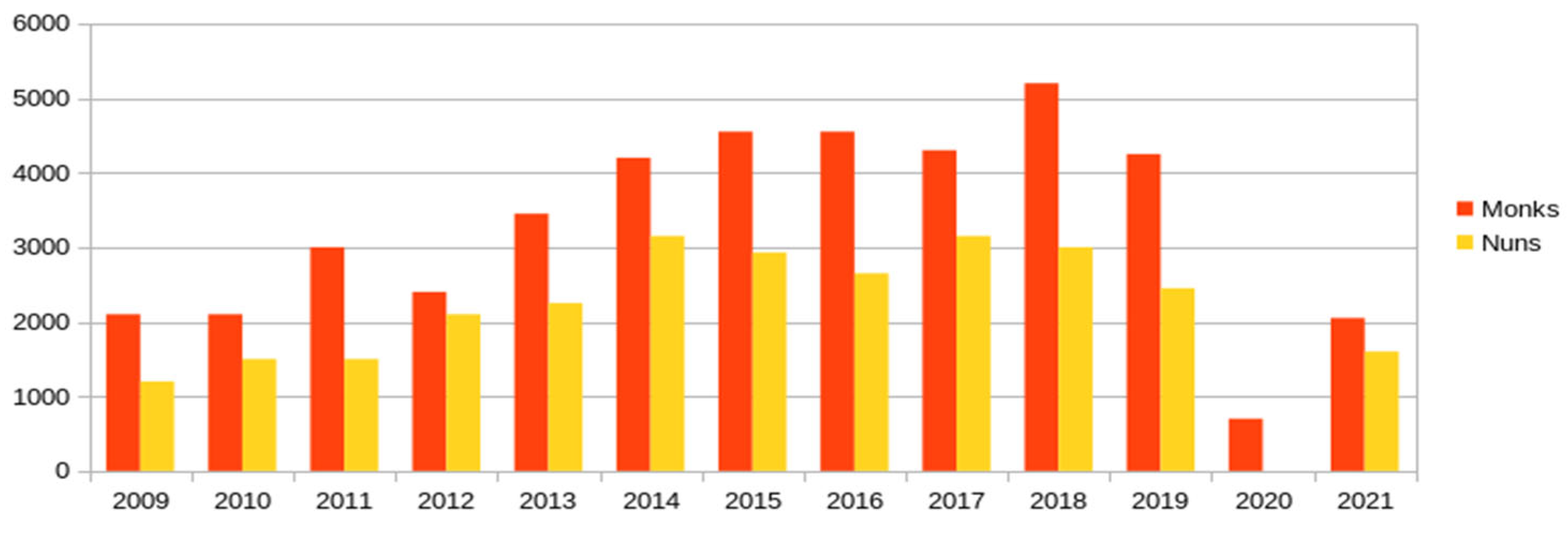

Looking specifically at ordination ceremonies, which resumed at the beginning of the 1980s, can provide a more accurate quantitative medium to visualize gender asymmetry in Chinese Buddhism. The first ordination ceremony of the post-Maoist era was held in early 1981 for forty-seven male candidates. The second one, organized by Longlian according to the dual ordination procedure, was held in early 1982 for nine female candidates (Bianchi 2019, pp. 154–55). Only in 1993 were the ordination procedures standardized by the promulgation of the first “National Administrative Measures for triple-platform ordinations by Chinese Buddhist temples” (Quanguo hanchuan fojiao siyuan chuanshou santan dajie guanli banfa 全国汉传佛教寺院传授三坛大戒管理办法). This text initially limited the number of ceremonies to five sessions a year and the number of participants to 200 per session. As the number of ordinations regularly exceeded these limitations in the 1990s, and in an attempt to control its growth (Ji 2009, p. 11; 2012, pp. 14–15), the BAC published new “Administrative measures” in 2000. They not only allowed designated temples to hold five to eight sessions a year and ordain 300 people per session, but also stipulated that from then on dual ordination procedures were to be held for female monastics. Consequently, there seem to have been a general increase in ordination numbers, with an average of 2774 per year between 1994 and 1999, and 4430 between 2000 and 2009 (Wen 2012, p. 38). According to Wen’s figures, a total of 60,944 people were ordained between 1994 and 2009, including 21,331 women, bhikṣuṇīs thus representing about 35% of these ordinations. At the end of 2011 a new change was made to the “Administrative measures” and the quotas were once again raised. The number of authorized ordination sessions per year was brought to a vague “about ten”, and the maximum number of participants per session to 350 (Ji 2012, pp. 14–15). Only two years later, in 2014, did this new attempt at regulation impact the overall number of ordinations. However, there seemed to be a significant increase in bhikṣuṇīs’ ordinations as early as 2012, exceeding 2000 for the first time (see Table 1). Table 1 and Figure 1 both show that 2012 is when the gap between bhikṣuṇīs’ and bhikṣus’ ordinations virtually closed, and the proportion of bhikṣuṇīs’ ordinations was highest. No similar bump in numbers is observed for bhikṣus at the time. This might suggest that because female monastics had fewer opportunities to get ordained, they were more likely to take advantage of the hike in quotas. Although there is no significant evolution in the following years, let us note that the highest number of ordinations was in 2018. The sudden drop in 2020 and 2021 should of course be attributed to the COVID 19 pandemic and to the subsequent cancellations of ordinations ceremonies. Finally, and in comparison with the aforementioned 35% of bhikṣuṇīs’ ordinations between 1994 and 2009 (Wen 2012, p. 38), numbers from Table 1 allow us to ascertain that there has been a slight increase in the following period, bhikṣuṇīs representing 39.31% of the overall ordinations from 2009 to 2021.12

Table 1.

Official ordination numbers per year since 2009 *.

Figure 1.

Number of male and female monastics’ official ordination ceremonies per year since 2009 (source: author).

Since 2011, the ordination quotas have not changed, but looking into the body of the official regulatory texts, one can notice a few new additions. A single sentence was added to the 2019 “Administrative measures” to limit the number of requests for ordination ceremonies from Buddhist associations in provinces, autonomous regions and provincial-level municipalities to one per year. Moreover, and in comparison with those previously published in 2016, the 2019 “Administrative measures” reassert and accentuate the separation between bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs, and further insist on the necessity of dual ordinations. Indeed, within the first section entitled “General dispositions”, article 6 now stipulates that “Conferring bhikṣuṇī precepts must always be done according to the dual ordination system, and conferring said precepts should be taking place in a temple for female monastics”13. In Section 2 “Requirements and necessary qualifications for temples conferring ordinations”, article 1 part 5 also adds that “At the time dual ordination is bestowed, there should be two temples acting as ordination sites, a distinction being made between temples for male and female monastics” (Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 2019, p. 11)14. These additional provisions suggest that dual ordination has not been systematically implemented since it was restored by Longlian in 1982 and included in the official system in 2000 and that when implemented the strict separation between bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs’ temples has not always been observed. However, dual ordination is now explicitly stated as such in new announcements, and the ordination sites clearly identified.

Among other things, regulations and standardization of these ceremonies allow us to determine the number of ordinations organized each year, and the potential number of candidates. Looking into these figures also raises another question, that of representation. Indeed, it has to be noted that if there are systematically fewer bhikṣuṇīs’ ordinations than bhikṣus’, it is primarily because there are fewer bhikṣuṇīs to choose from as ordination masters, and fewer temples to appoint as ordination platforms15. Consequently, there are fewer ordination ceremonies organized for female monastics than for male ones each year, respectively seven for twelve in 2019, nine for fifteen in 2018, nine for thirteen in 2017 and so on, bhikṣuṇīs’ ordination sessions generally representing between 35% and 40% of all ordination sessions held per year (Chonghe 2022). This would explain the proportions obtained in Table 1, and raise the following question: would there be more female Buddhist candidates to ordination than male ones given the opportunity? Some scholars argue that the proportion of ordained practicing bhikṣuṇīs has remained unchanged since 1993, with 30% of the Chinese Buddhist clergy being bhikṣuṇīs (Ji 2009, pp. 10–12). If the pool of female religious specialists is indeed lower, this will account for the lower number of temples and masters to choose from for ordination ceremonies and for lower possibilities to be represented. However, others advise that we take this information with caution. Indeed, according to Gildow (2020), there is an upward trend for bhikṣus to disrobe, which means the proportion of bhikṣuṇīs might well be more important than anticipated: there might be as many as 40,000 bhikṣuṇīs for 30,000 bhikṣus in mainland China in 2018, as stated by one of his informants (21–24). This surprising information from mainland China might compare to the situation of Buddhism in Taiwan16, and certainly give a whole new perspective to the representation issue.

3. The Teacher’s Influence: Continuity through Vertical Networks

At first glance, the Pushou temple does not seem to best exemplify the asymmetrical distribution of opportunities and resources for bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs outlined by these figures. Located on one of China’s four sacred Buddhist mountains, Mount Wutai, and established in 1991, this “star” temple (Qin 2000, p. 13) indeed currently hosts the largest community of female monastics in the People’s Republic of China (hereafter PRC)17. The number of residents is approximately 600 bhikṣuṇīs and bhikṣuṇīs-in-training but can reach 800 during the summer retreat (anju 安居), considered the busiest time of the year. In 2019, there were exactly 799 people living in the temple at the time of the summer retreat, a number that accounts for permanent residents and those who only join in yearly classes and activities. Moreover, the Mount Wutai Nuns’ Institute for Buddhist Studies (Zhongguo Wutaishan nizhong foxueyuan 中国五台山尼众佛学院) created in 1992 within the temple is unsurprisingly the largest Institute for Buddhist Studies (foxueyuan 佛学院) in the PRC. It aims at training a generation of female Buddhist leaders in compliance with both the Vinaya regulations and political requirements. The abbess of Pushou temple and president of the Institute, Rurui, is recognized as such a leader by both the government and her peers18. As she occupies high positions within the institutional system, she is particularly well placed to act as a representative of the Chinese Buddhist bhikṣuṇīs’ community. In addition to being at the head of the largest Buddhist temple and Institute in the country, she has indeed been sitting as vice-president of the Buddhist Association of Shanxi (Shanxi sheng fojiao xiehui 山西省佛教协会) since 1997, and as one of the BAC’s vice presidents since 2010. She was also named deputy chief administrator (fu mishu zhang 副秘书长) of the BAC in 2002, and acted as deputy director of the Chinese Buddhism Educational Administration and Teaching Methods Committee (Hanchuan fojiao jiaowu jiaofeng weiyuanhui 汉传佛教教务教风委员会) from 2015 to 202019.

However, looking more closely at Rurui’s life and influences might help us understand Pushou temple’s contribution to the gender asymmetry issue at hand. Born in 1957, Rurui was only ordained after the opening of China in the 1980s like most of her peers from the same generation20. Little is known about her early educational background, only that she received a good enough education in her hometown of Taiyuan (太原), Shanxi (山西), that she was able to go to university. She indeed received a university degree in literature from Taiyuan Normal University (Taiyuan shifan xueyuan 太原师范学院) before studying Chinese language and literature at Beijing Normal University (Beijing shifan daxue 北京师范大学). She then went on to become a school teacher. After meeting with the bhikṣuṇī Tongyuan, she switched paths and received tonsure in 1981 at Fahai temple (法海寺), Shanxi. At the same time, she also acted as an assistant for one of the most eminent bhikṣuṇīs of the 20th century, Longlian, and followed her to the Aidao nunnery (爱道堂) in Chengdu, Sichuan. In 1984 she received her full ordination at Huayan temple (上华严寺) in Datong (大同), Shanxi, during the second dual ordination ceremony organized in mainland China after the reopening, making her one of the first bhikṣuṇīs of the contemporary era to be ordained according to this particular procedure. As Tongyuan acted as the main ordination master (or “master of the precepts” jieshi 戒师) in this 1984 ceremony (Wen 1991, p. 33; Li 1992, p. 257), Rurui became her ordination disciple. After receiving ordination, Rurui studied for a few years at the Sichuan Nuns’ Institute for Buddhist Studies (Sichuan nizhong foxueyuan 四川尼众佛学院) lead by Longlian. At a later date in the course of the 1980s, she went on to study Vinaya with Tongyuan at the Jixiang hermitage (Jixiang jingshe 吉祥精舍) in Shaanxi (陕西).

Rurui later founded Mount Wutai’s Pushou temple in 1991 and the Mount Wutai Nuns’ Institute for Buddhist Studies in 1992, at age 34. Although she has received several distinctions over the years, two of them seem worth mentioning as a testament to her official recognition as a Buddhist leader and her promotion of higher education for bhikṣuṇīs: she was nominated “Chinese Cultural Personality” (Zhonghua wenhua renwu 中华文化人物) in 2016, and received an honorary PhD degree in Buddhist Studies from the Thai Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University (MCU), in November 2017 (Péronnet 2020, p. 131)21.

Telling Rurui’s life story in such a factual way almost makes her teachers’ role seem anecdotal. However, I would argue that it is their particular influence that led her to promote inherently asymmetrical ordination procedures, such as dual and śikṣamāṇā ordinations, as the “proper” standard for female monastics. The importance of bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs’ networks in building individual trajectories and favoring certain types of practices has long been observed by scholars in Buddhist studies (DeVido 2015; Bianchi 2017; Campo 2019, 2020). It can be correlated to a larger social network approach that “[…] is grounded in the intuitive notion that the patterning of social ties in which actors are embedded has important consequences for those actors” (Freeman 2004, p. 2). Hierarchical relationships with masters or teachers in particular are at the core of a Buddhist leader’s and his or her temple’s identity. These vertical Buddhist networks are often centered on or created by eminent charismatic figures, and legitimize monastic communities associated with them by ensuring historical continuity and prestige. Welch addresses this question in his work and maintains that bhikṣus affiliate to these networks through religious “kinship”, loyalty to a charismatic figure, or even according to their region of origin (1967, pp. 403–5). Today, however, several other modes of affiliation could be added to that list. Monastic education, especially within institutes for Buddhist studies, plays a critical role in the construction of networks for bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs in China, creating relationships between students, or between students and teachers. Official Buddhist institutions or associations are also crucial in creating bonds between colleagues and developing affinities between Buddhist executives (DeVido 2015, pp. 79–80; Ashiwa and Wank 2005, p. 222). Other types of affiliation to contemporary Buddhist networks include shared interests or experiences (Schak 2009; Fisher 2014, 2020), membership with an international organization (Wang 2013), social engagement or activism (Huang 2018), and so on.

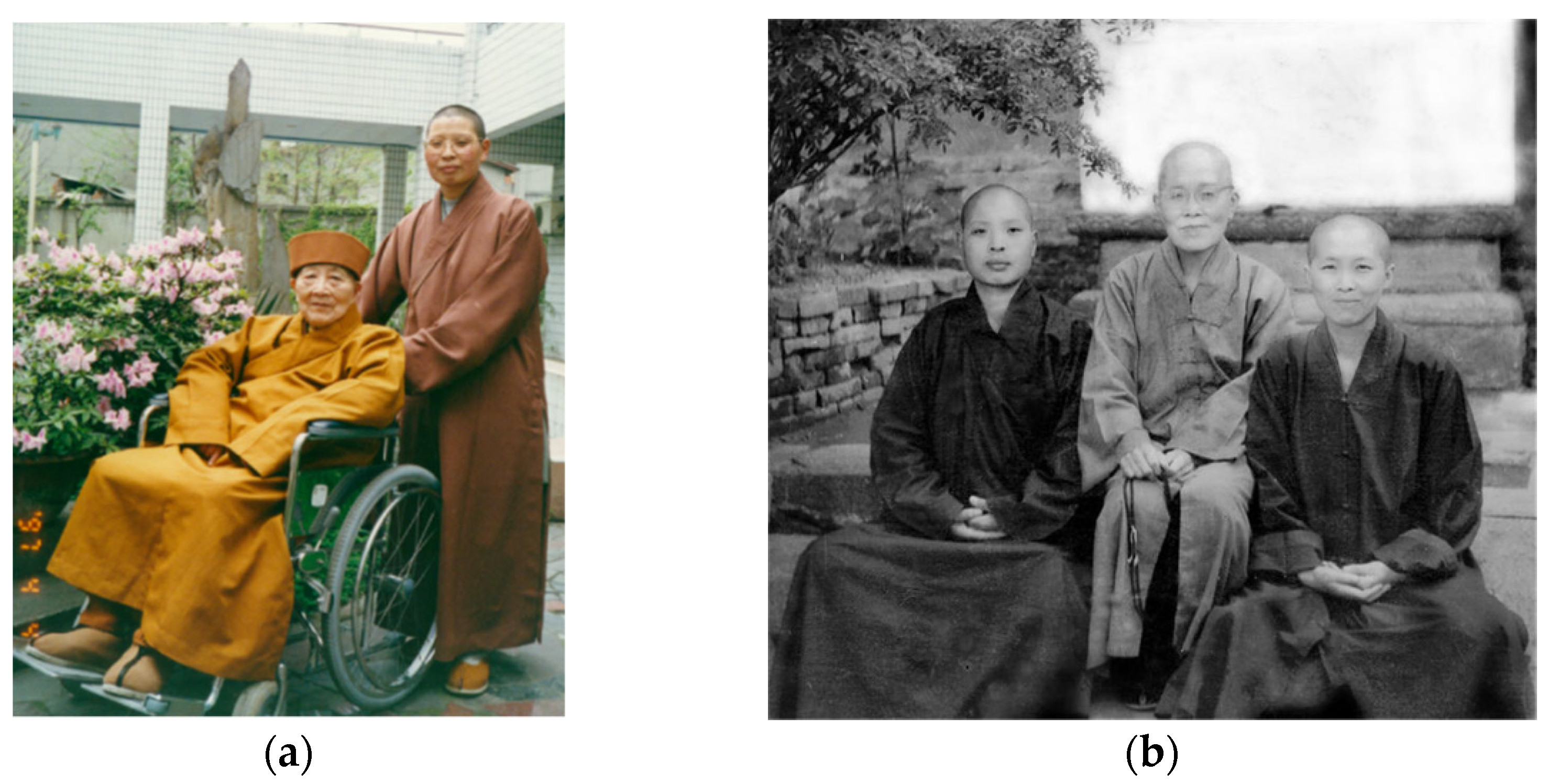

In Rurui’s case, affiliation to Longlian’s network is based on loyalty to a charismatic figure and relationship between teacher and student rather than on “kinship” (see Figure 2a). As mentioned earlier, she was Longlian’s assistant at the Aidao nunnery in Chengdu after she received tonsure in the early 1980s and studied with her at the Sichuan Nuns’ Institute for Buddhist Studies for a few years, but was never her dharma disciple—only a few students of Longlian were (Bianchi 2017, p. 295). Longlian was the one who restored the dual ordination procedure for bhikṣuṇīs in 1982. She also contributed to the development of śikṣamāṇā ordination and generally advocated for very rigorous Vinaya practice (Bianchi 2022, pp. 9–10)22. Her peers and students were well aware of and shared her positions. Contemporary Buddhist bhikṣuṇīs still refer to her when looking back at the evolution of Vinaya practices and the organization of the female monastic community over the past few decades (Chiu and Heirman 2014, p. 260). It seems that in their work on gurudharma rules, Chiu and Heirman have indeed established that “[…] changes are often the result of a leader’s educational influence” (2014, 260), which undoubtedly partially accounts for Rurui’s promotion of dual and śikṣamāṇā ordinations.

Figure 2.

Rurui and her teachers (source: Pushou temple). (a) Longlian & Rurui, 1997; (b) Rurui, Tongyuan, Miaoyin (妙音, 1957–), 1983, Nanshan temple (五台山南山寺).

However, Longlian was not Rurui’s only teacher and did not play a crucial part in the founding of Pushou temple. Tongyuan is the one who did (see Figure 2b). Rurui’s affiliation to Tongyuan does not fit within Welch’s definition of “kinship” either, even though the temple considers her its founding master. Indeed, Tongyuan applied an ideology throughout her life that was known as the “three no’s” (sanbu 三不): she decided not to take disciples, not to have her biography written, and not to write texts promoting her interpretation of Buddhist doctrine (Wen 1991, pp. 32–33). She nevertheless trained many female students, including Rurui, at the Jixiang hermitage, an institution she created specifically for the study of Vinaya in the Shaanxi province. Rurui was thus Tongyuan’s student, as well as her ordination disciple, and considers herself her heir, although she is not formally recognized as part of her lineage. Tongyuan was close to Longlian and met with her on several occasions over the years, sharing an interest in establishing orthodox procedures and practices for female monastics according to the Chinese Vinaya (Péronnet 2020, pp. 134–36). As a matter of fact, Longlian trusted her to act as ordination master during the first dual ordination ceremony of the post-Mao era in 1982. Tongyuan then organized the second one in 1984. Her wishes were to “[…] call upon the whole community of bhikṣuṇīs to establish a temple of the ten directions […]”23 in order to properly teach and study the Vinaya, which Rurui explicitly carried out by opening the Vinaya-centered Pushou temple the year of her teacher’s passing. The Pushou bhikṣuṇīs still revere Tongyuan as the master whose legacy they keep alive. Her relics are kept in a specific hall of the temple, the Hall for Remembering Kindness (Yi’en tang 忆恩堂), and her passing is commemorated every year on the twentieth day of the first lunar month. Even more significant is the threefold system implemented by Rurui at Pushou temple: “[…] Avataṃsaka as lineage, Vinaya as practice, Pure Land as destination […]” (Huayan wei zong, jielü wei xing, jingtu wei gui 华严为宗,戒律为行,净土为归)24. This was passed down from the monk Cizhou (慈舟1877–1957) to Tongyuan, her tonsure disciple, and from Tongyuan to Rurui, providing the temple with a sense of continuity as part of the Huayan school of Buddhism and as a Vinaya center (Wen 1991, p. 32; Yang 2011, p. 24)25.

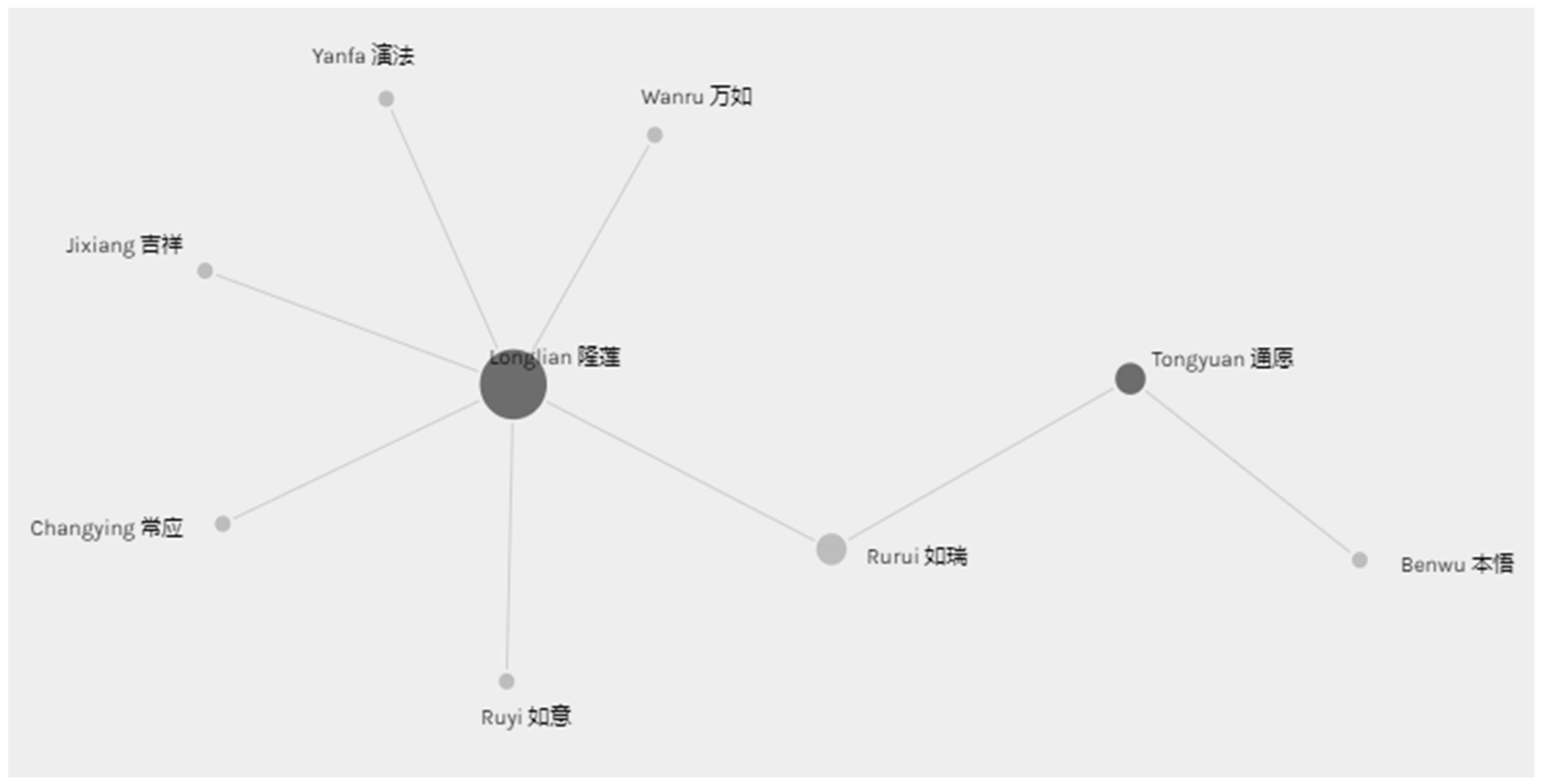

To sum up, the priorities Rurui set for Pushou temple and the Mount Wutai Nuns’ Institute for Buddhist Studies can be traced to a large extent to Tongyuan and Longlian’s teachings, especially in terms of monastic discipline. Rurui, but also others such as Wanru (万如 1956–), abbess of the Taiping temple (太平寺) in Wenzhou (温州), or Ruyi (如意 1963–), abbess of the Qifu temple (祈福寺) in Chengdu, affiliated to Tongyuan and/or Longlian’s networks by becoming their student at either the Sichuan Nuns’ Institute for Buddhist Studies or the Jixiang hermitage. Data collected during fieldwork and gathered by Chiu (2016, 2017), as well as with information found on each of these three institutions’ websites, show that they all promote ordination procedures that were not necessarily widespread in 20th century China until the 1980s, such as dual and śikṣamāṇā ordinations, which exemplifies the importance of legacy regarding ordination practices. Tongyuan and Longlian’s education networks can be further—although partially—exemplified by Figure 3. From online sources, the Buddhist educational background of these bhikṣuṇīs has been traced back to either Longlian or Tongyuan. Rurui, Wanru, and Ruyi all appear as part of this network visualization. After ascertaining the influence both eminent masters had in the fields of monastic discipline and education, one can only assume that other bhikṣuṇīs connected to their networks might have successfully promoted and implemented the same ordination procedures they did, thus spreading their teachers’ views on asymmetry. However, the extent of this phenomenon would certainly need to be researched further. In any case, Rurui followed in her teachers’ footsteps, ultimately designing a structure that would be able to carry out their vision and that of their masters before them26, into the present. Ideas were passed down from one generation to the next, “bridging the gap” (Campo 2019) to constitute a legacy: such is the role of vertical networks. Moreover, the continuity and prestige attached to these networks were one of the ways Rurui could obtain legitimacy, a necessary commodity for Buddhist institutions to survive in post-Mao China. It was legitimacy, as well as Rurui’s capacity to access the high spheres, that were crucial in mobilizing the financial, human, and symbolic resources allowing her to provide Chinese bhikṣuṇīs with a successful working model for “proper” ordination procedures (Péronnet 2021).

Figure 3.

Longlian and Tongyuan’s educational networks27 (source: author).

4. Advocating for Asymmetrical Ordination Procedures in Contemporary Times

Answering a question I asked about Longlian and Tongyuan’s influence on her promotion of Vinaya practices and on her management of Pushou temple, Rurui stated that:

These two high-merit bhikṣuṇīs believed that monastic discipline is at the root of monastics’ spiritual development, and that nuns ought to rely on the Buddhist system of receiving nuns’ precepts according to the dual ordination procedure. Ven. Tongyuan in particular spent all her life specializing in and spreading monastic discipline, training Śikṣamāṇā, bestowing dual ordinations, building a monastic community, and giving lectures about the precepts.

这两位大德比丘尼都认为戒律是出家修行的根本,比丘尼应依于佛制在二部僧中求受比丘尼戒。特别是通愿老法师,一生专弘戒律,培养式叉尼,传授二部僧戒,建立僧团,演说戒法。28

This quote first accentuates Rurui’s unique connection to Tongyuan. She, rather than Longlian, is presented as the one who made a great contribution to the field of Vinaya. She is the one whose legacy Rurui keeps alive by reproducing virtually everything she ever accomplished—specializing in the implementation and study of the Vinaya, promoting dual and śikṣamāṇā ordination procedures, building Pushou temple, giving lectures on various subjects, including monastic discipline, and so on. This particular quote also mentions Tongyuan and Longlian’s role in promoting dual ordination, a procedure that they deemed crucial to monastic discipline and the cultivation of Chinese bhikṣuṇīs (Bianchi 2022, p. 8). Since their time, it has been normalized as the “proper” way to conduct bhikṣuṇīs’ ordinations and has officially been included in the standardized triple-platform ordination system in 2000 (Ji 2009, p. 11; Bianchi 2019, p. 157). As Pushou temple is not part of the Buddhist sites authorized to hold ordination ceremonies, Pushou bhikṣuṇīs entirely depend on the standardized official system to get ordained and, as such, have no choice but to go along with the dual ordination procedure. Thus, it is worth mentioning that promoting it is not only considered a way to pursue ideals set by Rurui’s teachers or necessary in itself to support cultivation but is also in line with official regulations.

Contemporary institutions hail back to historical narratives surrounding dual ordination, and other asymmetrical procedures such as śikṣamāṇā ordination. These narratives surprisingly configure asymmetries as what contributes to the distinctive of female monastics. In a comprehensive presentation document drafted by Pushou temple in 201729, the section relating to the Institute entitled “student monastics’ aptitudes, origins, and admission procedures” (学僧资质、来源及录取方式) presents dual ordination and all ordination requirements specific to female monastics as part of a special request from the Buddha himself, accounting for thorough compliance with these rules:

[One must] abide by the Buddha’s specific requirements for female monastics, that is to undergo two years of studies and training as a Śikṣamāṇā before receiving the full ordination, only then can the essence of dual ordination be considered genuine and satisfactory. Consequently, the Institute also attaches importance to the training and education that goes into moving up from śrāmaṇerī to Śikṣamāṇā to fully ordained nun. […] [One] must first study and train in the “pure practice” class for a year, meet every institutional standard and be officially tonsured, before she enters the śrāmaṇerī class to study for a year, then the Śikṣamāṇā class to study for two years. Only after having followed the six Śikṣamāṇā precepts can she receive the dual ordination and formally join the “department of disciplinary studies”.

遵循佛陀对尼众的特别要求,即必须经两年式叉尼学习锻练后再受具戒,才算真正圆满二部僧戒的实质。因此,学院也重视从小众到大尼次第而上的培养与教育。[…] 先在净行班学习锻练一年,各方面考核合格且正式落发后,再进入沙弥尼班学习一年,之后再入式叉尼班学习两年,式叉尼六法清净后才可受二部僧戒,正式进入戒学部学习。

This text makes it clear that agreeing to be trained as a Śikṣamāṇā and going through the dual ordination procedure is necessary for being admitted at the Mount Wutai Nuns’ Institute for Buddhist Studies, thus making it a contractual clause for getting access to higher education. It furthermore suggests that additional years of training and studying are a privilege that has to do with the Buddha’s special treatment of female monastics and that distinguishes them from male ones. In any case, differentiating features—or asymmetry—are emphasized. It is what sets bhikṣuṇīs apart from bhikṣus to mark them as distinctively pure.

As shown earlier, there seems to be at least another step necessary to the “proper” completion of dual ordination, a step that allows female monastics to study and be trained longer than male monastics. The śikṣamāṇā ordination marks the beginning of a two-year probationary period30 during which the Śikṣamāṇā must follow a set of six precepts if she is to claim full ordination. This ordination procedure can be seen as an asymmetrical one mainly because it constitutes an extra step in the bhikṣuṇīs’ career and has no equivalent for bhikṣus. Following Longlian and Tongyuan’s example, Rurui also advocates for this specific procedure and for an extended period of time between the śikṣamāṇā and the bhikṣuṇī ordination. This division was summed up as follows by one of my informants at Pushou temple:

Actually at that time we are called the female novice [śrāmaṇerī] only in the image aspect, in Chinese is “xintong shamini” [形同沙弥尼]. […] In your appearance you look like a monastic, but actually you haven’t taken any precepts […]. But after one year, we take the ten precepts of the female monastic. […] at that time we are called […] “fatong shamini” [法同沙弥尼]. In the morning we take the ten precepts of the female monastic and in the afternoon we’ll get the “shichani” [式叉尼] ceremony […]. Actually it happens in one day. […] At that time the “shichani” they don’t know exactly the name of the full “bhikkhuni”‘s precepts31, but they have to practice every precepts of “bhikkhuni”, [they are] actually already in their training program. And the “shichani” program will last for two years. If you can observe [the śikṣamāṇā precepts] very strictly and purely, then you are qualified to get the full ordination.32

The model promoted by the Pushou temple, based on Vinaya texts, thus advises a training period of at least three years before receiving dual ordination. One should first train for year as a śrāmaṇerī “in appearance”, before receiving both the ten śrāmaṇerī precepts and the six śikṣamāṇā precepts in one day. Then, the two-year probationary period serves as a way to practice not only the śikṣamāṇā precepts, but also the 348 bhikṣuṇī precepts that they will later take during full ordination, allowing them to experience and master them beforehand—an opportunity that male monastics do not have. The informant quoted above indeed considers this particular period to be “very significant training for the future female full ordination”, and states that “learning about the spirit of these [bhikṣuṇī] precepts […] is the main reason for regulating this probationary period. It helps female monastics to practice early and to be familiar with the full monastic’s life earlier”. In the same way that dual ordination seems to be essential to monastic discipline (Bianchi 2022, p. 12), śikṣamāṇā ordination is introduced in the presentation text above as the only way to ensure that dual ordination is “genuine and satisfactory”, and in the following quote as necessary to receive “valid” full ordination and be “qualified” as a bhikṣuṇī. Raising the question of what needs to be done by female monastics to be qualified enough also raises the very interesting issue of whether a value judgment is sometimes made against bhikṣus’ education prior to full ordination, as they do not receive the same drastic training as bhikṣuṇīs. Asymmetry, in this particular instance, is not only to be found in the number of training years, but also in the additional knowledge of the Vinaya and esteem that may come from it.

Although Longlian, Tongyuan, and now Rurui have been advocating for this probationary period, it is still not part of the official ordination system and is not mandatory by governmental standards to receive full ordination. Indeed, the necessary two-year interval between śrāmaṇerī and śikṣamāṇā ordinations—which are conferred the same day—and bhikṣuṇī ordination would seem to jeopardize the standardized triple-platform ceremonies that should be held in a reasonable time-frame but in “no less than a month” (Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 2019, p. 11). However, Longlian devised a system that would complement the official one as a “doctrinally orthodox adaptation to the contemporary institutional environment in which Buddhism finds itself in the PRC” (Péronnet 2020, p. 146). As it has been confirmed to me by several informants, the Pushou temple provides a concrete model for this complementary system: the śrāmaṇerī and śikṣamāṇā precepts are taken a few years before dual ordination, as prescribed by the Vinaya, and then śrāmaṇerī precepts are taken once more during official triple-platform ordination ceremonies. This working solution has led to the probationary period being more widely spread and recognized in mainland China33. Although the current “Administrative measures” do not mention the śikṣamāṇā ordination explicitly, they nevertheless advise that women should practice and study for two years after being tonsured, in contrast with the one year suggested for men (Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 2019, p. 12). Moreover, between 2014 and 2021, five calls for dual ordination ceremonies, out of fifty-five, specifically mentioned that female applicants should have taken the śikṣamāṇā precepts in order to register. Most of them required applicants to have spent at least two years training at a temple before applying (Chonghe 2022). Although there is still a long way to go before standardization, Chiu and Heirman’s research suggests that this practice is now increasingly common in Chinese Buddhist nunneries (Chiu and Heirman 2014, p. 260), and the multiplication of references to the additional two years of training for female monastics indeed testifies to its popularity.

One other step that the Puhsou temple promotes is the bodhisattva ordination. Because of the rigorous discipline of the mind that it requires, it is usually considered to be an advanced step in the monastic career, only found in the Mahāyāna tradition. During the ceremony, the already ordained bhikṣuṇī (or bhikṣu) takes ten major and forty-eight minor bodhisattva precepts, and sometimes receives incense burns (Chiu 2019, pp. 204–5). Once again, Rurui, and one of her assistants relaying her views, seem to think that this requires strict training:

[…] those who have just […] received the full ordination shouldn’t get the bodhisattva ordination immediately. Because you know, the bodhisattva ordination, especially the female one […], is very detailed, much more difficult to observe. So if one doesn’t have any basic training, […] one tends to make mistakes. So [Rurui] wants the female monastics to lay a very good foundation for the “bhikkhuni” education […]. Basically, those "bhikkhuni" should be educated, should be trained in a very careful way.34

According to the above quote, bodhisattva ordination is necessary to receive what is perceived as “proper” Buddhist education and thus become a monastic beyond reproach—one that can make “no mistake”. As these precepts are not, to my knowledge, gender-specific, it also seems particularly odd that my informant would stress their importance for “females” and associate them with “bhikkhuni” education, differentiating bhikṣuṇīs from bhikṣus even when there is no difference to make. An explanation might lie in the fact that bodhisattva precepts are reputed particularly difficult to observe. As such, bhikṣuṇīs who would be willing and able to take them should be recognized as even more worthy, and ultimately be praised as experts in monastic discipline. Rurui’s position on the matter, and that of her students, seems to gravitate once more towards providing bhikṣuṇīs with a chance to develop their spiritual cultivation and raise their status even further.

As this has proved to be somewhat of a delicate subject to ask about, it is difficult to know to which extent the bodhisattva ordination is first received as part of the triple-platform ordination system and then again later on, just as the śrāmaṇerī ordination. However, one other informant in Pushou temple, who in 2019 had just been ordained according to the triple-platform system, assured me that she had not yet taken the bodhisattva precepts. She planned to do it two years later, after studying for some time at the Institute of Buddhist Studies for Nuns, which she said was the expected thing to do. She would then receive bodhisattva ordination a second time, two years after full ordination. Thus, this process of combining Vinaya requirements with official expectations would also seem to apply to bodhisattva ordination, at least in the case of Pushou temple.

After Longlian and Tongyuan’s mostly theoretical model, Pushou bhikṣuṇīs advocate for separating the different ordination procedures in time, and strive to make it work to complement the standardized system. Rurui, although not as prolific on this topic as her teachers, can be seen as an enforcer of their ideals, effectuating asymmetrical training in Vinaya studies while dealing with the evermore present regulations of monastic development. This distinct rigorous training lead Pushou temple to “establish a model”35 and be recognized as “an advanced unit and a paragon of Buddhist practice among the PRC’s nunneries”36 (Péronnet 2021, pp. 135–36). By knowingly insisting on the bhikṣuṇīs’ career being different from that of the bhikṣus, Rurui and her peers give the female monastic community more time to study, cultivate, and perfect themselves. They ultimately position bhikṣuṇīs as easily identifiable religious specialists and scholars in possession of enough symbolic and material resources to access higher positions and legitimately act as representatives for the monastic community at large.

5. Conclusions: Subordination or Emancipation?

After looking into the asymmetrical aspects of ordination procedures, one can raise the issue that Chinese bhikṣuṇīs seem to be promoting their subordination to bhikṣus and encouraging gender inequality in an attempt to comply with the Vinaya and the gurudharma. The image that Pushou temple shows to the world, all the more visible during public rituals, is that of a temple full of competent, educated bhikṣuṇīs who still perpetuate a patriarchal vision of Buddhism through their rigorous approach to monastic discipline. Patriarchy in Buddhism is at least what scholars in gender and feminist studies wrote about at the end of the twentieth century (Gross 1981; Paul 1985; Willis 1985; Harris 1999), and what I first saw when confronted with this particular image. Promoting dual or śikṣamāṇā ordinations and, more generally, advocating for distinct procedures and practices for female monastics does seem to be putting them at a disadvantage. The number of opportunities female monastics are presented with, the number of candidates for dual ordination in recent years, the issue of representation, and the number of precepts and training years, certainly attest to the overwhelming presence of asymmetry in Chinese Buddhism.

However, we should move beyond these first impressions to see that the distinction between bhikṣus’ and bhikṣuṇīs’ experiences is not necessarily synonymous with subordination and can be actively sought after. Bhikṣuṇīs like Yinkong (印空 1921–) fight for equal opportunities and instruction by offering higher education to bhikṣuṇīs, sometimes creating asymmetry of their own by encouraging longer years of study that ultimately allow bhikṣuṇīs to be more knowledgeable than bhikṣus (Campo 2020, pp. 264–80; Campo forthcoming, p. 13). Advancing bhikṣuṇīs’ knowledge and status was always the goal behind the creation of the Mount Wutai Nuns’ Institute for Buddhist Studies, but also, perhaps more surprisingly so, behind the promotion of asymmetrical ordination procedures by Rurui and Pushou temple. In doing so, Pushou bhikṣuṇīs conform to the standardized ordination system recognized by the state and Vinaya regulations, and therefore are legitimating their place as “properly” ordained interlocutors to the official institutions and to the saṅgha. This “double legitimacy” process participates in them finding their place in Chinese society, improving their image and status, and ultimately seeking positions equivalent to those occupied by bhikṣus. What was passed down to Rurui through Longlian and Tongyuan’s networks, what provides Pushou temple with a sense of continuity, is the will to restore a form of orthodoxy for female monastics and, quite paradoxically, to promote bhikṣuṇīs as religious specialists and scholars with qualifications equal to or even higher than bhikṣus. Thus, contrary to what one might think at first, and although it does play on asymmetry, the concrete model set up by Longlian, advocated by Tongyuan, and implemented by Rurui, does not aim at perpetuating subordination or a patriarchal view of Buddhism but at elevating, or dare I say emancipating bhikṣuṇīs. That is not to say that institutional inferiority does not exist in Chinese Buddhism or that the current system is not informed by a history of gender discrimination, but that one should definitely take into account the various solutions devised to remedy it, besides fighting it head-on. Moreover, bhikṣuṇīs are active on several fronts and find additional ways to thrive within this somewhat conservative environment. One such way is higher education. The model they offered, and still offer, is then a dynamic process which aims to find a balance between traditional practices and a modern vision of the position of women in Buddhism.

Funding

My research on the Pushou temple and Buddhist nuns in contemporary China was funded by the PhD Research Scholarship from the Università degli Studi di Perugia; by the Joint Research PhD Fellowship from the Confucius Institute (Hanban); by the Field Scholarship from the French School of Asian Studies (EFEO); and by fieldwork grants from the French Center for Interdisciplinary Studies on Buddhism (CEIB) and the French Research Institute on East Asia (IFRAE).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This paper could not have been written without the financial and administrative support provided by the French Center for Interdisciplinary Studies on Buddhism (CEIB), the French Research Institute on East-Asia (IFRAE–Inalco), and the Università degli Studi di Perugia. I would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to Ester Bianchi for including me in this collaborative project and for always pointing me in the right direction. I would also like to thank Nicola Schneider for organizing the “Gender Asymmetry in the Different Buddhist Traditions Through the Prism of Nuns’ Ordination and Education” Conference together with Ester Bianchi and for her very helpful notes on this paper. I am finally indebted to Shi Hongzhi for her unfailing friendship and help over the years, and to Daniela Campo, Manon Laurent, Kati Fitzgerald and the anonymous reviewers for greatly improving this paper with their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I will use the Sanskrit term “bhikṣuṇīs” throughout this paper, to refer to fully-ordained nuns from the Chinese Buddhist tradition, unless indicated otherwise. |

| 2 | The original version of this paper was first presented at the “Gender Asymmetry in the Different Buddhist Traditions Through the Prism of Nuns’ Ordination and Education” Conference, which was held in May 2022 at the Università degli Studi di Perugia. It was first drafted as part of collaborative paper entitled “Assessing the Emergence and Impact of Nuns Dual Ordination in New Era China”, written together with Ester Bianchi (see her contribution to this Special Issue). |

| 3 | On Longlian and Tongyuan, see among others Wen (1991), Li (1992), Qiu (1997), Bianchi (2017), Péronnet (2020). |

| 4 | The triple-platform ordination system dates back to the early 17th century and was widespread during the Republican era, before being chosen as the only standardized ordination system in the contemporary People’s Republic of China (PRC). However, this is not the case in Taiwan, and even though the Buddhist Association of the Republic of China has been recommended it since the 1950s, other procedures are still used (Bianchi 2019). Some Taiwanese temples, such as Nanlin nunnery (南林尼僧苑), confer śrāmaṇera or śrāmaṇerī, full and bodhisattva ordinations on separate occasions. |

| 5 | The five basic precepts are as follows: one should abstain from 1. killing other sentient beings, 2. stealing, 3. engaging in sexual activity, 4. lying, 5. consuming alcohol. The five following ones prohibit 6. eating at inappropriate times, 7. using ornaments, perfumes, ointments, 8. watching or engaging in shows, dancing, singing, 9. sleeping on high or luxurious beds, 10. receiving gold and silver. |

| 6 | This is according to the prātimoksạ of the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya. The Dharmaguptaka Vinaya is one of three Vinayas still in use today, the one on which the Chinese Buddhist tradition is based. Within this body of texts is the prātimoksạ, a set of rules that the Buddha first listed to answer what he considered faults and that now regulate monastic life. About the bhikṣuṇī precepts of the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya see Lekshe Tsomo (1996); Heirman (2002). |

| 7 | There are ten major (shi chong jie 十重戒) and forty-eight minor (sishiba qing jie 四十八轻戒) bodhisattva precepts, that are only to be found in the Mahāyāna tradition (Chiu 2019, pp. 204–5). These precepts mainly come from an apocryphal text from the 5th century, the Brahmā’s net sūtra (Fanwang jing 梵网经), and might also be called Brahmā’s net precepts (fanwang jie 梵网戒) or Mahāyāna precepts (dasheng jie 大乘戒). The ten major precepts include the five basic ones, and add that one should abstain from 6. spreading the saṅgha’s faults, 7. congratulating oneself or speaking ill about others, 8. being miserly, 9. harboring anger, 10. speaking ill about the Three Jewels. Infringing any of these is a first class infraction (pārājika) and will result in the transgressor being expelled from the monastic community (Heirman 2009, p. 83). |

| 8 | According to the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, the Śikṣamāṇā has to follow six rules (liufa 六法): abstain from 1. engaging in sexual intercourse, 2. stealing, 3. killing other beings, 4. lying about one’s spiritual achievements, 5. eating at improper times, 6. drinking alcohol (Heirman 2002, pp. 67–75). Although the Śikṣamāṇā only has six rules to follow (as opposed to ten for śrāmaṇerī), she also has to learn and observe all the precepts for bhikṣuṇīs as per the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, something that was also mentioned to me by one of my informants who had just received the full ordination. Moreover, any transgression during this particular period would mean that the Śikṣamāṇā has to start over again, whereas only a confession is required during the novitiate. In that sense, the Śikṣamāṇā can be seen as a step forward on the path to nunhood. See Heirman (2008, pp. 133–34), and Chiu and Heirman (2014, pp. 258–60). |

| 9 | For a list of these eight fundamental rules, refer to Heirman (2002, pp. 64–65), but also to Schneider (2013) or Wijayaratna (1991) for different formulations. They can also be found directly at the source, in the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, by looking under T no.1428, 22: 923a22–b21 on the CBETA website (CBETA 2016). As they validate the subordination of bhikṣuṇbhikṣuīs to bhikṣubhikṣus and ratify institutional inequality within Buddhism, they are largely debated today and their authenticity is questioned, especially by Taiwanese bhikṣuṇīs (Chen 2011). |

| 10 | Numbers published in 2015 by the SARA used to appear on a database that listed all officially registered religious sites. Although the SARA was discontinued in 2018, the database could still be accessed up until very recently at the following address: http://www.sara.gov.cn/zjhdcsjbxx/index.jhtml (last accessed on 20 April 2020), but the website is now obsolete. |

| 11 | Created in 1929, the BCA was the BAC’s predecessor and the most influential Buddhist Association until 1949, when it moved to Taiwan. Its goal is to create a collective identity among Buddhists, and build an official image that satisfies the expectations of modern society. An elitist institution, it has always been a place to produce, distribute, and appropriate symbolic power (Ji 2015). |

| 12 | According to personal discussions I have had with other scholars in Buddhist studies, most triple-platform ordination ceremonies would seem to ordain more people than the actual number set by official regulations. We should at least add fifty people to the official quotas per ordination ceremony. Let us take the year 2019—the last year before ordination numbers plummeted due to the COVID 19 pandemic—as an example: taking into account these additional fifty participants per ceremony, bhikṣus’ ordinations would amount to 4850, and bhikṣuṇīs’ ordinations to 2800, which would bring the total to 7650. There is a difference of almost 1000 people between official numbers and this estimate, which would suggest that the practice of disregarding quotas is still very much alive today, and that the authorities are voluntarily downplaying Buddhist engagement. However, this does not influence the proportion of bhikṣuṇīs’ ordinations per year. |

| 13 | “第六条 传授比丘尼戒一律实行二部僧授戒制度,传授本法尼戒应在尼众寺院进行。” (Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 2019, p. 11). |

| 14 | “第十一条 […](五) 同期传授二部僧戒应有二座寺院作为传戒场所,分别为男众寺院和尼众寺院。” (Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 2019, p. 11). |

| 15 | As of today, temples that want to hold official triple-platform ordination ceremonies have to submit an official request to the local Buddhist Association. Only when their request has been duly examined and approved by the local Religious Affairs Department can they act as ordination platforms. For instance, according to Wen (2012, p. 35) only sixteen temples were approved as ordination platforms in 2009, among which six were temples for bhikṣuṇīs. According to my own data, nineteen temples acted as platforms in 2019, among which seven were temples for bhikṣuṇīs. The list of all officially sanctioned ordination platforms appears on Chonghe (2022). |

| 16 | In Taiwan, women have been ordained in large numbers after the ordination system was established in 1953. Since then, the number of female candidates has systematically been two to three times higher than the number of male ones, and as a consequence bhikṣuṇīs represent 75% of the monastic population (Li 2000; DeVido 2010). |

| 17 | That is, only when referring to communities of bhikṣuṇīs residing within the physical space of the temple. Much larger ones do exist, particularly in Tibetan Buddhism, gathered around religious buildings in large camps of makeshift huts. In Yachen Gar for instance, located in the Sichuan province, West of the city of Chengdu, the “monastery” or “camp” hosted around 10,000 Tibetan Buddhist nuns in 2018, according to unofficial figures (Oostveen 2020). |

| 18 | Rurui is, in fact, the “supervisor”, “administrator” or “head bhikṣuṇī” of Pushou temple, from the Chinese term zhuchi 住持, literally “dweller and sustainer of the dharma”. She is not called a fangzhang 方丈 however, a term historically used in Chan Buddhism to refer to the abbot’s quarters, and now used to refer to the male head of a monastery. To my knowledge, Longlian was the only bhikṣuṇī from the modern and contemporary era to be called a fangzhang, even though she wasn’t officially one. |

| 19 | Rurui’s record is available on the BAC’s website (Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 2015b). See also the webpage listing all members of committees for the Ninth Council of the BAC (Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 2015a). |

| 20 | In addition to scientific literature, I have been gathering biographical information about Rurui online on Pushou temple’s website (Pushou Temple 2019), or onsite on pamphlets, and caught glimpses of her life during formal and informal interviews. |

| 21 | This information was given to me by one of my informants, but can also be found on Pushou temple’s official WeChat account as well as on various websites. |

| 22 | Both procedures existed in mainland China but were never widespread in nunneries of the Chinese tradition. Dual ordination was first introduced in China in 433 by Sri-Lankan bhikṣuṇīs and later promoted by Vinaya specialists, although rarely used in the course of the centuries. Only during the Republican era was it advocated for by eminent Buddhist masters as the only orthodox ordination procedure for bhikṣuṇīs, and was restored as such by Longlian in 1982. The śikṣamāṇā ordination suffered a similar fate. It is part of the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, but historical sources suggest it was never common among Chinese nunneries (Heirman 2008, pp. 133–34). Although not included in the standardized system, śikṣamāṇā ordinations have been established by Longlian and her disciples together with dual ordination and is now more widespread than ever. |

| 23 | “[…] 就要号召全体尼众起来建十方道场。”. This particular quote is from a speech Tongyuan made to her disciples in 1981, and appears on Pushou temple’s website (Pushou Temple 2020). A temple of the ten directions (shifang conglin 十方丛林) is a specific category of temple also called “public”, usually big in size and belonging to the broader monastic community. The ten directions are the four cardinal directions, the inter-cardinal ones, along with the zenith and the nadir, meaning this particular type of temple would choose the abbot or abbess not from within the lineage or tonsure family but from the outside or from any “direction”. |

| 24 | A slogan that can be found in several texts about Pushou temple, for instance in Zhou (2012, p. 55), and on Pushou temple’s website (Pushou Temple 2020). |

| 25 | Cizhou is an eminent bhikṣu who was particularly active in the first part of the 20th century, a Vinaya specialist. He took part in a movement to revive Vinaya practices long forgotten in the Chinese Buddhist tradition, including ordination procedures (Campo 2017). However, not much has been written on him, and the reader could refer to his own work (Cizhou 2004). |

| 26 | Longlian’s master was Nenghai (能海 1886–1967), and the one who tasked her to restore dual ordination procedures for bhikṣuṇīs. Just as Cizhou, he was considered an expert in Vinaya, which he also taught, and advocated for a rigorous approach to monastic discipline. On Nenghai, see Bianchi (2009) and Wen (2003). |

| 27 | This figure was made using Palladio, a web-based visualization tool developed by the Humanities + Design research lab from Stanford University, available at https://hdlab.stanford.edu/palladio/, accessed on 26 July 2022. Data on the educational background of these particular bhikṣuṇīs was collected from various websites, from WeChat, from secondary sources, or even from exchanges with other scholars, before being entered into a table. |

| 28 | As Rurui was unavailable at the time of my visit, questions were transmitted to her in writing on 8 August 2019, and she answered in writing as well, on 19 September 2019. |

| 29 | This document is entitled “Pushou temple’s ‘Three-Plus-One’ project” (普寿寺三加一) and lists the specificities of all institutions contributing to this project, namely the Pushou temple, its branch-temple in Taiyuan the Dacheng temple (大乘寺), and the Bodhi Love association (Puti aixin xiehui 菩提爱心协会). It was given to me by a Dacheng bhikṣuṇī on June 2nd, 2017. About the “Three-Plus-One” project, see Péronnet (2020, pp. 141–42) and Mao (2015). |

| 30 | The gurudharma and various Vinaya texts, including the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya observed in mainland China, do mention a study period of two years before a Śikṣamāṇā can ask for ordination (Heirman 2008). However, there seems to be no more detailed information on the scheduling of this period, leaving it open to interpretation. When in the field, it has been brought to my attention that Pushou temple Śikṣamāṇā would only need to let two Chinese New Years pass, rather than taking the precepts for two whole years from date to date. If one took the śikṣamāṇā precepts right before a Chinese New Year, she could theoretically receive full ordination immediately after the second if she was considered to be ready, thus having only trained as a Śikṣamāṇā for a little more than a year. |

| 31 | The pali term bhikkhuni is used by my informant to refer to fully ordained Chinese Buddhist nuns and their 348 precepts. |

| 32 | This quote has been taken from a formal interview in English with a Pushou bhikṣuṇī, recorded on 16 August 2019. I took the liberty of polishing the English and taking out the repetitions, to make the content more accessible to the reader without loosing the original meaning. |

| 33 | However, even now, every nunnery in mainland China has not adopted this probationary period. As one of my informants puts it, “it seems very difficult for a lot of temples and female monastic to [include] this training program, so a lot of temples will ignore this aspect.” |

| 34 | This quote has been taken from the same formal interview in English with a Pushou bhikṣuṇī, recorded on 16 August 2019, than the aforementioned one. Here, the informant not only gives her own opinion, but as a spokesperson to Rurui, she also wishes to convey her teacher’s view on bodhisattva ordination. |

| 35 | “创立风范” (Bei 1994, p. 30). |

| 36 | “全国尼众寺院的先进单位和道风的典范” (Yang 2011, p. 23). |

References

- Ashiwa, Yoshiko, and David L. Wank. 2005. The Globalization of Chinese Buddhism: Clergy and Devotee Networks in the Twentieth Century. International Journal of Asian Studies 2: 217–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, Xin 悲心. 1994. Lüfeng qingliang—Fang Wutaishan nizhong san daochang 律风清凉—访五台山尼众三道场 [Vinaya on mount Qingliang: Investigating Three Nunneries on Mount Wutai]. Wutaishan yanjiu 五台山研究 4: 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Ester. 2009. The ‘Chinese lama’ Nenghai (1886–1967): Doctrinal tradition and teaching strategies of a Gelukpa master in Republican China. In Buddhism Between Tibet and China. Edited by Matthew Kapstein. Somerville: Wisdom Publications, pp. 295–346. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Ester. 2017. Subtle Erudition and Compassionate Devotion: Longlian, ‘The Most Outstanding Bhikṣuṇī’ in Modern China. In Making Saints in Modern China. Edited by David Ownby, Vincent Goossaert and Ji Zhe. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 272–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Ester. 2019. ‘Transmitting Precepts in Conformity with the Dharma’: Restoration, Adaptation and Standardization of Ordination Procedures. In Buddhism after Mao: Negotiations, Continuities, and Reinventions. Edited by Ji Zhe, Gareth Fisher and André Laliberté. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 152–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Ester. 2022. Reading Equality into Asymmetry. Dual Ordination in the Eyes of Modern Chinese Bhikṣuṇīs. Religions 13: 919. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/13/10/919 (accessed on 13 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Campo, Daniela. 2017. A Different Buddhist Revival: The Promotion of Vinaya (jielü 戒律) in Republican China. Journal of Global Buddhism 18: 129–54. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, Daniela. 2019. Bridging the Gap: Chan and Tiantai Dharma Lineages from Republican to Post-Mao China. In Buddhism after Mao: Negotiations, Continuities, and Reinventions. Edited by Ji Zhe, Gareth Fisher and André Laliberté. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 123–51. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, Daniela. 2020. Chinese Buddhism in the post-Mao era: Preserving and reinventing the received tradition. In Handbook on Religion in China. Edited by Stephan Feuchtwang. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar, pp. 255–80. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, Daniela. Forthcoming. Female Education in a Chan Public Monastery: The Dajinshan Buddhist Academy for Nuns. Religions 13.

- CBETA. 2016. Sifenlü 四分律 [Dharmaguptaka Vinaya]. Available online: http://tripitaka.cbeta.org/T22n1428 (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- Chen, Chiung Hwang. 2011. Feminist Debate in Taiwan’s Buddhism: The Issue of the Eight Garudhammas. Journal of Feminist Scholarship 1: 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Tzu-Lung, and Ann Heirman. 2014. “The Gurudharmas in Buddhist Nunneries of Mainland China”. Buddhist Studies Review 31: 241–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Tzu-Lung. 2016. Contemporary Buddhist Nunneries in Taiwan and Mainland China: A Study of Vinaya Practices. Ph.D. thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Tzu-Lung. 2017. An Overview of Buddhist Precepts in Taiwan and Mainland China. Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies 13: 150–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Tzu-Lung. 2019. Bodhisattva Precepts and Their Compatibility with Vinaya in Contemporary Chinese Buddhism: A Cross-Straits Comparative Study. Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies 17: 193–224. [Google Scholar]

- Chonghe 崇和. 2022. ZenMonk.cn. Available online: http://zenmonk.cn/stdj.htm (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Cizhou 慈舟. 2004. Cizhou chanshi jinian wenji 慈舟禅师纪念文集 [Collected works to commemorate Chan master Cizhou]. Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexueyuan 中国社会科学院. [Google Scholar]

- DeVido, Elise A. 2010. Taiwan’s Buddhist Nuns. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeVido, Elise A. 2015. Networks and Bridges: Nuns in the Making of Modern Chinese Buddhism. The Chinese Historical Review 22: 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Gareth. 2014. From Comrades to Bodhisattvas: Moral Dimensions of Lay Buddhist Practice in Contemporary China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Gareth. 2020. From Temples to Teahouses: Exploring the Evolution of Lay Buddhism in Post-Mao China. Review of Religion and Chinese Society 7: 34–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Linton C. 2004. The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. Vancouver: Empirical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gildow, Douglas. 2020. Questioning the Revival: Buddhist Monasticism in China since Mao. Review of Religion and Chinese Society 7: 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, Rita. 1981. Feminism from the Perspective of Buddhist Practice. Buddhist-Christian Studies 1: 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guojia zongjiao shiwuju 国家宗教事务局. 2020. Zongjiao Huodong Changsuo Jiben Xinxi 宗教活动场所基本信息 [Basic Information on Religious Sites]. Available online: http://www.sara.gov.cn/zjhdcsjbxx/index.jhtml (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Harris, Elizabet J. 1999. The Female in Buddhism. In Buddhist Women across Cultures. Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, Ann. 2002. Rules for Nuns According to the Dharmaguptakavinaya: The Discipline in Four Parts. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, Ann. 2008. Where is the Probationer in the Chinese Buddhist Nunneries? Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 158: 105–37. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, Ann. 2009. Speech is silver, silence is golden? Speech and silence in the Buddhist Samgha. The Eastern Buddhist 40: 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Weishan. 2018. The Place of Socially Engaged Buddhism in China: Emerging Religious Identity in the Local Community of Urban Shanghai. Journal of Buddhist Ethics 25: 531–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Zhe 汲喆. 2009. Fuxing sanshi nian: Dangdai zhongguo fojiao de jiben shuju 复兴三十年: 当代中国佛教的基本数据 [Thirty years of revival: Essential figures of contemporary Chinese Buddhism]. Fojiao guancha 佛教观察 5: 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Zhe. 2012. Chinese Buddhism as a Social Force: Reality and Potential of Thirty Years of Revival. Chinese Sociological Review 45: 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Zhe. 2015. Buddhist Institutional Innovations. In Modern Chinese Religion II: 1850–2015. Edited by Vincent Goossaert, Jan Kiely and John Lagerway. Leiden: Brill, pp. 729–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lekshe Tsomo, Karma. 1996. Sisters in Solitude: Two Traditions of Buddhist Monastic Ethics for Women a Comparative Analysis of the Chinese Dharmagupta and the Tibetan Mūlāsarvāstivada Bhikṣuṇī Prātimokṣa Sūtras. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Hongru 李宏如. 1992. Wutaishan Fojiao 五台山佛教 [Buddhism on Mount Wutai]. Taiyuan 太原: Shanxi gaoxiao lianhe chubanshe 山西高校联合出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yu-chen. 2000. Crafting Women’s Religious Experience in a Patrilineal Society: Taiwanese Buddhist Nuns in Action (1945–1999). Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Rujing. 2015. Chinese Bhiksunis in contemporary China: Beliefs and practices on Three-Plus-One Project. International Journal of Dharma Studies 3: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostveen, Daan F. 2020. Rhizomatic Religion and Material Destruction in Kham Tibet: The Case of Yachen Gar. Religions 11: 533. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/11/10/533 (accessed on 22 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Paul, Diana Y. 1985. Women in Buddhism: Images of the Feminine in Mahāyāna Tradition. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Péronnet, Amandine. 2020. Building the Largest Female Buddhist Monastery in Contemporary China: Master Rurui between Continuity and Change. Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies Special Supplement: 128–57. Available online: https://ocbs.org/when-a-new-generation-comes-up-buddhist-leadership-in-contemporary-china/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Péronnet, Amandine. 2021. Stabilire un’immagine di eccellenza: La costruzione di un modello monastico buddhista per monache nella Cina contemporanea”. Sinosfere 13: 134–46. Available online: https://sinosfere.com/2021/05/23/amandine-peronnet-stabilire-unimmagine-di-eccellenza-la-costruzione-di-un-modello-monastico-buddhista-per-monache-nella-cina-contemporanea/ (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Pushou Temple. 2019. A Brief Introduction of Master Rurui. Available online: http://www.pushousi.net/index.php/wap/info_18.html (accessed on 14 April 2019).

- Pushou Temple. 2020. A Brief Introduction of Master Tongyuan. Available online: http://www.pushousi.net/index.php/wap/info_54.html (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Qin, Wen-jie. 2000. The Buddhist Revival in Post-Mao China: Women Reconstruct Buddhism on Mt. Emei. Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Shanshan 裘山山. 1997. Dangdai Diyi Biqiuni: Longlian Fashi Zhuan 當代第一比丘尼——隆蓮法師傳 [The First bhikṣuṇī of the Modern era: Master Longlian’s Biography]. Fuzhou: Fujian meishu chubanshe 福建美术出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Schak, David C. 2009. Community and the New Buddhism in Taiwan. Minsu Quyi 163: 161–92. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Nicola. 2013. Le Renoncement au Féminin: Couvents et Nonnes Dans le Bouddhisme Tibétain. Nanterre: Presses Universitaires de Paris Nanterre. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jung-Chang. 2013. International Relief Work and Spirit Cultivation for Tzu Chi Members. In Buddhism, International Relief Work, and Civil Society. Edited by Hiroko Kawanami and Geoffrey Samuel. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 123–39. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Holmes. 1967. The Practice of Chinese Buddhism: 1900–1950. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Jinyu 温金玉. 1991. Yidai ming ni Tongyuan fashi 一代名尼通愿法师 [Ven. Tongyuan, famous nun of her generation]. Wutaishan yanjiu 五台山研究 2: 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Jinyu 温金玉. 2003. Nenghai fashi jielü sixiang yanjiu 能海法师戒律思想研究 [Researching master Nenghai’s Vinaya ideology]. Foxue yanjiu 佛学研究, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Jinyu 温金玉. 2012. Zhongguo dalu fojiao chuanjie huodong de huigu yu fansi 中国大陆佛教传戒活动的回顾与反思 [Review and assessment of Buddhist ordination activities in mainland China]. Zongjiao yanjiu 宗教研究, 14–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel-Teuber, Katharina. 2015. 2014 Statistical Update on Religions and Churches in the People’s Republic of China. Religions & Christianity in Today’s China 5: 20–41. Available online: https://www.china-zentrum.de/issues/page-3 (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Wijayaratna, Môhan. 1991. Les Moniales Bouddhistes: Naissance et Développement du Monachisme Féminin. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Janice D. 1985. Nuns and Benefactresses: The Role of Women in the Development of Buddhism. In Women, Religion and Social Change. Edited by Yvonne Y. Haddad and Ellison B. Findly. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 59–85. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xiaoyan 杨晓燕. 2011. Dangdai Nizhong Jiaoyu Moshi Yanjiu 当代尼众教育模式研究 [Research on Contemporary Educational Methods for Nuns]. Master’s thesis, Zhongyang minzu daxue 中央民族大学, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 中国佛教协会. 2015a. Di Jiu Jie Lishihui Ge Zhuanmen Weiyuanhui Zhuren, Fuzhuren, Weiyuan Mingdan 第九届理事会各专门委员会主任、副主任、委员名单 [List of Committee Directors, Deputy Directors, and Members for the Ninth Session of the BAC’s Council]. Available online: https://www.chinabuddhism.com.cn/cs1/2015-05-04/8823.html (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 中国佛教协会. 2015b. Rurui 如瑞. Available online: http://www.chinabuddhism.com.cn/djc/jjlsh/2015-04-25/8619.html (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 中国佛教协会. 2019. “Quanguo hanchuan fojiao siyuan chuanshou santan dajie guanli banfa” 全国汉传佛教寺院传授三坛大戒管理办法 [National Administrative Measures for triple platform ordinations by Chinese Buddhist temples]. Fayin 法音 10: 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Zhuying 周祝英. 2012. Wutaishan Huayanzong xianzhuang” 五台山华严宗现状 [The current situation of the Huayan school on mount Wutai]. Wutaishan yanjiu 五台山研究 112: 51–55. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).