Female Education in a Chan Public Monastery in China: The Jiangxi Dajinshan Buddhist Academy for Nuns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Jiangxi Dajinshan Buddhist Academy for Nuns

2.1. Enrollment and Scale

2.2. Students and Teachers

2.3. Curricula and Schedule

3. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1 | The five officially recognized religions are Buddhism, Daoism, Catholicism, Protestantism, and Islam. |

| 2 | See the document “China’s Policies and Practices on Protecting Freedom of Religious Belief” released by the State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China in April 2018: http://www.scio.gov.cn/zfbps/32832/ Document/1626734/1626734.htm (accessed 30 January 2019). |

| 3 | In the year 2000. |

| 4 | This estimate includes monks (bhikṣus), nuns (bhikṣuṇīs), probationers (śikṣamāṇās), and novice monks (śrāmaṇeras) and nuns (śrāmaṇerīs). |

| 5 | For a critical evaluation of concepts and literature on Buddhist education in twentieth-century China, see (Travagnin 2017). |

| 6 | According to (Long 2002, p. 188), the first seminary for monastics was established as early as 1903 by monk Liyun at the Kaifu Monastery in Hunan province. The first seminary to be styled foxueyuan, however, was the famous Wuchang Institute of Buddhist Studies (Wuchang foxueyuan 武昌佛學院) established by Taixu in 1922; on this academy, see (Lai 2017). |

| 7 | The list of Buddhist seminaries operating in China between 1912 and 1950 provided by (Holmes Welch 1968, appendix 2, pp. 285–87) does not distinguish seminaries for nuns. On Buddhist education in Republican China, see (Lai 2013). |

| 8 | This information is provided by Li Ming in his 2009 MA thesis on sangha education during the Republican period (“Minguo shiqi seng jiaoyu yanjiu 民國時期僧教育研究”, cited by (Gildow 2016, pp. 32–33)). |

| 9 | After closing and reopening, the Wuchang Female Institute of Buddhist Studies became the World Female Institute of Buddhist Studies (Shijie foxueyuan nüzhongyuan 世界佛學苑女眾院) in 1931: see (He 1999). |

| 10 | The Buddhist Academy of China was run and funded by the State: (Ji 2019, pp. 175–76). |

| 11 | According to (Gildow 2016, pp. 42–43), student-monks (xueseng 學僧) represented about 3% of China’s Han Buddhist monastic population in 2016, which means there are “at least fifteen times more seminarians than during the peak of seminaries during the Republic”. |

| 12 | According to Gildow’s informants, female “branch” seminaries, as other branch seminaries, are mostly or entirely independent from their male counterpart (Gildow 2016, pp. 204–5). |

| 13 | The Minnan Buddhist Academy, first established in 1925, was reorganized by Taixu in 1927; it ran until 1939, before closing due to the Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). |

| 14 | I visited this academy in July 2017. |

| 15 | |

| 16 | On this academy, see (Yang 2011, especially pp. 23–31, 39–49). On Pushou monastery, see (Péronnet 2021, 2022). |

| 17 | The importance of considering the pedagogical agendas of Buddhist educational enterprises was highlighted by Thomas Borchert in his study of Theravada monastic education in China (“Training Monks or Men: Theravāda Monastic Education, Subnationalism, and the National Sangha of China,” Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 28, no. 2, 2005: 241–72; cited in (Lai 2013, p. 171)). |

| 18 | For an interesting comparison with a female Daoist academy in contemporary China (the Kundao Academy 坤道學院 at Nanyue Mountain, in Henan province), see (Wang 2020). |

| 19 | I wish to express my deepest gratitude to retired abbess Yinkong, current abbess Duncheng, and Dajinshan’s whole monastic community for their openness and patience during all these years. |

| 20 | All names have been anonymized in this paper, except for those of the retired and current abbesses. |

| 21 | Monasteries are considered “large” in China if their community counts at least one hundred monastics. “Public” means that the monastery welcomes itinerant and permanent monastics coming from the whole country (in other words, the residence is not restricted to the abbot’s disciples). Moreover, properties of public monasteries belong to the whole Buddhist community (and not to the abbot), and in theory, their abbot is publicly elected (although this is not the case in the majority of public monasteries today, where the abbotship is passed down to the disciples of the retiring abbot). |

| 22 | Yinkong was ordained by the Buddhist Chan leader Xuyun 虛雲 (ca. 1864–1959) in 1955 and received Dharma transmission in Xuyun’s Linji lineage from monk Benhuan 本煥 (1907–2012) in 1987. On Yinkong and for a bibliography, see (Campo and Despeux, forthcoming). |

| 23 | Interview with Yinkong conducted in October 2013. |

| 24 | Idem. |

| 25 | On Yinkong’s and Benhuan’s Dharma lineage, and on the way this particular form of religious kinship has connected the monastic leaders of the first half of the twentieth century to the senior generation of monks and nuns who first engaged in the Buddhist reconstruction of post-Mao China, see (Campo 2019). |

| 26 | In 2016, the Caodong Buddhist Academy (Caodong foxueyuan 曹洞佛學院) was established at Baoji Monastery 宝积寺 in Caoshan (Yihuang 宜黃 district of Fuzhou city). See its website http://csbjs.99.com/college (accessed on 11 October 2022). |

| 27 | From 1985 to 2005. |

| 28 | Fu Hui means “Good Fortune and Windom”. See their website http://www.fuhui.org/llearn_e/llearn.htm (accessed on 11 October 2022); see also (Laliberté 2022, p. 171). |

| 29 | Years of enrollment are 1994, 1996, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2013. After that, the academy enrolled in 2017, 2020, and 2022. |

| 30 | Counting from a minimum of 10 student-nuns to a maximum of 50. |

| 31 | More precisely, 268 student-nuns in the elementary program, 320 in the beginner program, and 159 in the intermediate program, that is, an average of 90 student-nuns graduating every three years in each of the three programs. |

| 32 | There were 99 student-nuns at the academy when I visited in 2015. |

| 33 | For the sake of comparison, the Sichuan Buddhist Academy for Nuns counted about 60 students in 2011: (Yang 2011, p. 40). |

| 34 | The Buddhist Academy for nuns of Pushou monastery at Wutaishan, which is the largest in the country, counted between 500 and 600 student-nuns in 2011, while the Sichuan Buddhist Academy for Nuns counted about 60 student-nuns (Yang 2011, pp. 23, 40). |

| 35 | See https://www.pusa123.com/pusa/news/hdyugao/130930.shtml (accessed on 11 October 2022). The 2020 call for applications (https://www.pusa123.com/pusa/news/hdyugao/125703.shtml, accessed on 11 October 2022) also included “to have decided on one’s own free will and with the consent of one’s teachers and seniors”. |

| 36 | In the 2020 call for applications, this sentence reads “strictly uphold monastic discipline and be familiar with the devotions of the five halls” (wutang gongke 五堂功課), that is, the two daily liturgies and formal meals plus one meditation session (https://www.pusa123.com/pusa/news/hdyugao/125703.shtml, accessed on 11 October 2022). |

| 37 | Depressive disorders were not mentioned in the 2020 call for applications. |

| 38 | See https://www.pusa123.com/pusa/news/hdyugao/130930.shtml (accessed on 11 October 2022). |

| 39 | The reason for this new requirement is unknown to me. It could be linked to the large genetic database that China is apparently building. |

| 40 | Including a green health code and a green State Department Epidemic Prevention and Control Trip Card, the obligation of not having traveled in high-risk areas in the past 14 days, and so forth. |

| 41 | See https://www.pusa123.com/pusa/news/hdyugao/130930.shtml (accessed on 11 October 2022). |

| 42 | When I visited in 2015, the oldest nun of the academy was aged 44 (she was born in 1971). The age limit for enrollment was of 30 years old when the academy was first established. |

| 43 | If we take as reference the average age limit of 28 years old provided by (Ji 2019, p. 190) for the period 1994–2013 and we compare it to age limits for the bachelor degree program of a few 2022 calls for applications, the required age limit was, for example, 30 years at the Buddhist Academy of China, the most selective in the country, 35 years at the male section of the Minnan Buddhist Academy, and 40 years at the male section of the Fujian Buddhist Academy (Fujian foxueyuan 福建佛學院). |

| 44 | In 2022 calls for applications, the required age limit was 36 years at the Guangdong Buddhist Academy for Nuns, 38 years at the Jiangsu Buddhist Academy for Nuns (Jiangsu nizhong foxueyuan 江蘇尼眾佛學院) and Sichuan Academy for Nuns (bhikṣunīs and śrāmaṇerikās), 32 years at the female section of the Putuo Academy for nuns (Zhongguo foxueyuan Putuoshan xueyuan 中國佛學院普陀山學院), and 35 years at the female section of the Minnan Buddhist Academy (Minnan foxueyuan 閩南佛學院). For a few examples of age limits in 2022 calls for applications of male academies, see note 43. |

| 45 | See “Abolishing the One-Child Policy: Stages, Issues and the Political Process” on this (Scharping 2019). |

| 46 | We can consider, for example, that a single child born in 1979 turned 43 in 2022. |

| 47 | See, for example, the 2022 call for applications of the Fujian Buddhist Academy at https://www.pusa123.com/pusa/news/hdyugao/130925.shtml (accessed on 11 October 2022). |

| 48 | At the Fujian Buddhist Academy, the curriculum for the male section preconizes one year of preparatory program (yukeban), two years of specialized secondary program (zhongzhuanban 中專班), four years of a bachelor degree program (benkeban), and three years of a master degree program (yanjiuban). The curriculum for the female section preconizes two years of preparatory program, two years of specialized secondary program, four years of a bachelor degree program, two years of a higher Vinaya program (lüxue dazhuanban 律學大專班), and three years of a Vinaya master degree program (lüxue yanjiusheng ban 律學研究生班). See https://www.pusa123.com/pusa/news/hdyugao/130925.shtml (accessed on 11 October 2022). |

| 49 | Chinese Buddhists do not calculate this duration according to the number of full years, but according to the number of summer retreats one has passed as a novice. |

| 50 | The probationer (shichani 式叉尼) is an intermediate step between women’s novitiate and ordination, which is mentioned in Vinaya texts and nowadays making a comeback in Chinese monasteries. See on this (Heirman 2008; Chiu and Heirman 2014; Bianchi 2022). |

| 51 | For example, although the age limit for ordination is 59 years, a novice already aged 55, and who was unable to enroll at a Buddhist academy because she entered religion at 36 or 37, will find it difficult to be selected for ordination unless applications received by one of the ordaining monasteries do not exceed the quota allowed. |

| 52 | Interview conducted in July 2015. |

| 53 | That is, even if they do not possess the minimum junior high-school degree required for the preparatory program, but only an elementary school degree. |

| 54 | Interview conducted in March 2019. |

| 55 | In 2019, Buddhist courses for the Vinaya class included Shengyan’s Compendium of Vinaya Studies (Jielüxue gangyao 戒律學綱要), The Commentary on Karman in the Four-Part Vinaya (Sifenlü shanbu suiji jiemoshu 四分律刪補隨機羯磨疏, X. 727), The Sutra in 42 sections (Sishier zhang jing 四十二章經, T. 784), and a course on the Bodhisattva precepts. |

| 56 | That is, counting a dozen resident nuns. |

| 57 | Interview conducted in March 2019. |

| 58 | The teacher-nuns were almost all graduates of the Dajinshan academy and had received tonsure at Jinshan monastery. |

| 59 | Only assisted by two or three teacher-monks and teacher-nuns, at least until 2011: (Yang 2011, pp. 27–28, 39–40). |

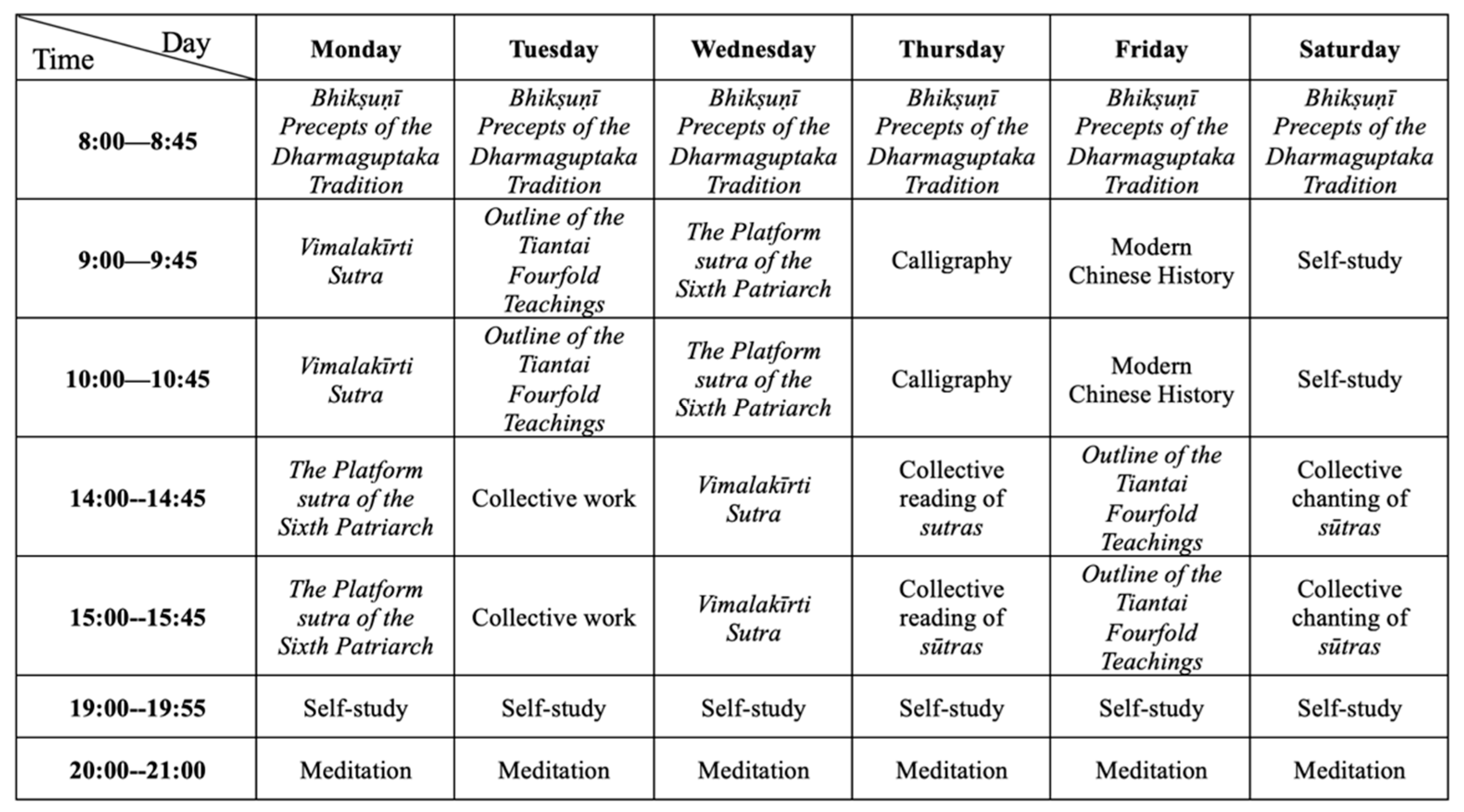

| 60 | The duration of each class is 45 min. |

| 61 | According to the academic dean in 2019, the volume of political courses would have surely increased in the following years (interview conducted in March 2019), but the COVID-19 pandemic apparently contributed to slowing down this development. |

| 62 | Making up for an overall agenda of 42 h per week, six days a week from Monday to Saturday. In 2019, student-nuns had three 45-min classes from 8:00 to 10:45 a.m., then two more from 2:00 to 3:45 p.m., plus self-study (zixi 自習) and meditation in the evening from 7:00 to 9:00 p.m. |

| 63 | On this tension, see (Gildow 2016, pp. 89–116; Ji 2019, pp. 195–99). |

| 64 | On Xuyun and his annalistic biography, see (Campo 2016). Not only Yinkong’s master Benhuan was a disciple of eminent Chan master and Buddhist leader Xuyun, but Yinkong was herself ordained by Xuyun in 1955. |

| 65 | Buddhist courses for the preparatory program: The Sutra in 42 sections (Sishier zhang jing 四十二章經, T. 784), A Collection of Retribution Stories of the Buddhist Saints (Fojiao shengzhong yinyuan ji 佛教聖眾因緣集), The Sutra on the bhikṣuṇī Mahāprajāpatī, and “Study of Buddhist paraphernalia”. Buddhist courses for the bachelor degree program, first-year: “History of Buddhism”, “Fundamentals of Buddhism”, “The annalistic biography of Chan Master Xuyun”, The Lucid Introduction to the One Hundred Dharmas (Dasheng baifa mingmenlun 大乘百法明門論, T. 1614). Buddhist courses for the bachelor degree program, third-year: The Bhikṣuṇī Precepts of the Dharmaguptaka Tradition, The Vimalakīrti Sutra, The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, and The Outline of the Tiantai Fourfold Teachings (Tiantai sijiaoyi 天台四教儀, T. 1931). Buddhist courses for the master degree program, first year: The Bhikṣuṇī Precepts of the Dharmaguptaka Tradition, the Commentary on Karman in the Four-Part Vinaya, and “Monastic regulations in practice”. |

| 66 | On this ritual, see (Stevenson 2001). |

| 67 | If, at the academy, student-nuns obey Dajinshan hierarchy, during vacations, they are still under the authority of their tonsure master. |

| 68 | Interview conducted in March 2019. |

| 69 | On sport activities in Buddhist nunneries, see (Chiu, forthcoming; Heirman, forthcoming). |

| 70 | See also the example of Beijing Tongjiao nunnery 通教寺 restored in 1941 as a renowned and active Vinaya nunnery (DeVido 2015, p. 81; cited in (Bianchi 2022)). |

| 71 | Although the conferral of tonsure in public monasteries was strictly regulated (and often prohibited) by imperial and Republican Chinese monastic codes, it was and is generally practiced all over China. For this reason, tonsures are only conferred at the smaller Jinshan monastery on top of the hill, while ordinations are conferred at the larger Dajinshan monastery. |

References

- Bianchi, Ester. 2001. The Iron Statue Monastery. «Tiexiangsi», a Buddhist Nunnery of Tibetan Tradition in Contemporary China. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Ester. 2022. Reading Equality into Asymmetry: Dual Ordination in the Eyes of Modern Chinese Bhikṣuṇīs. Religions 13: 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, Daniela. 2016. Chan Master Xuyun: The Embodiment of an Ideal, the Transmission of a Model. In Making Saints in Modern China. Edited by David Ownby, Vincent Goossaert and Ji Zhe. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, Daniela. 2019. Bridging the gap: Chan and Tiantai Dharma lineages from Republican to post-Mao China. In Buddhism after Mao: Negotiations, Continuities, and Reinventions. Edited by Ji Zhe, Gareth Fisher and André Laliberté. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 123–51. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, Daniela, and Catherine Despeux. Forthcoming. Breaking through the illusion of life, similar to a dream’. Portrait of Yinkong 印空 (b. 1921), abbess of a Chan monastery in Jiangxi. In The Everyday Practice of Chinese Religions. Elder Masters and the Younger Generations in Contemporary China. Edited by Adeline Herrou. London: Routledge.

- Chiu, Tzu-Lung, and Ann Heirman. 2014. The Gurudharmas in Buddhist Nunneries of Mainland China. Buddhist Studies Review 31: 241–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Tzu-Lung. Forthcoming. Physical Exercise and Sporting Activities in Contemporary Taiwanese and Mainland Chinese Buddhist Monasteries. In "Take the Vinaya as Your Master": Monastic Discipline and Practices in Modern Chinese Buddhism. Edited by Ester Bianchi and Daniela Campo. Leiden: Brill.

- Gildow, Douglas. 2016. Buddhist Monastic Education: Seminaries, Academia, and the State in Contemporary China. Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- He, Jianming 何建明. 1999. Zhongguo jindai de fojiao nüzhong jiaoyu 中國近代的佛教女眾教育. Fojiao wenhua 佛教文化 6: 57–59. Available online: http://www.chinabuddhism.com.cn/a/fjwh/199906/14.htm (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Heirman, Ann. 2008. Where is the Probationer in the Chinese Buddhist Nunneries? Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 158: 105–37. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, Ann. Forthcoming. Body Movement and Sport Activities: A Buddhist Normative Perspective from India to China. In “Take the Vinaya as Your Master”: Monastic Discipline and Practices in Modern Chinese Buddhism. Edited by Ester Bianchi and Daniela Campo. Leiden: Brill.

- Ji, Zhe. 2012. Chinese Buddhism as a Social Force: Reality and Potential of Thirty Years of Revival. Chinese Sociological Review 45: 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Zhe. 2019. Schooling Dharma teachers: The Buddhist academy system and elite monk formation. In Buddhism after Mao: Negotiations, Continuities, and Reinventions. Edited by Gareth Fisher, Ji Zhe and André Laliberté. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 171–209. [Google Scholar]

- Jiangxi nizhong foxueyuan ershi zhounian yuanqing zhuankan 江西尼眾佛學院二十週年院慶專刊. 2014. Jiangxi Nizhong Foxueyuan, and Jiangxi Dajinshan Chansi, eds. Fuzhou: Jiangxisheng Fojiao Xiehui. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Rongdao. 2013. Praying for the Republic: Buddhist Education, Student Monks, and Citizenship in Modern China (1911–1949). Ph.D. dissertation, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Rongdao. 2017. The Wuchang ideal: Buddhist education and identity production in Republican China. Studies in Chinese Religions 3: 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberté, André. 2022. Chinese Religions and Welfare Regimes Beyond the PRC. Legacies of Empire and Multiple Secularities. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Darui. 2002. Buddhist Education in Sichuan. Educational Philosophy and Theory 34: 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péronnet, Amandine. 2021. Le temple Pushou 普壽寺 et le projet Trois-Plus-Un. Nonnes et modes de production du bouddhismecontemporain en Chine continentale. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Perugia and Inalco, Perugia, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Péronnet, Amandine. 2022. Embodying Legacy by Pursuing Asymmetry: Pushou temple and female monastics’ ordinations in contemporary China. Religions 13: 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharping, Thomas. 2019. Abolishing the One-Child Policy: Stages, Issues and the Political Process. Journal of Contemporary China 28: 327–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, Daniel B. 2001. Text, Image, and Transformation in the History of the Shuilu fahui, the Buddhist Rite for Deliverance of Creatures of Water and Land. In Cultural Intersections in Later Chinese Buddhism. Edited by Marsha Weidner. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 30–72. [Google Scholar]

- Travagnin, Stefania. 2017. Buddhist education between tradition, modernity and networks: Reconsidering the ‘revival’ of education for the Sangha in twentieth-century China. Studies in Chinese Religions 3: 220–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Robin R. 2020. From Female Daoist Rationality to Kundao Practice: Daoism beyond Weber’s Understanding. Review of Religion and Chinese Society 7: 179–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Holmes. 1968. The Buddhist Revival in China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xiaoyan 楊曉燕. 2011. Dandai nizhong jiaoyu moshi yanjiu 當代尼眾教育模式研究. Master thesis, Zhongyang Minzu Daxue, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Yuan. 2009. Chinese Buddhist Nuns in the Twentieth Century: A Case Study in Wuhan. Journal of Global Buddhism 10: 375–412. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campo, D. Female Education in a Chan Public Monastery in China: The Jiangxi Dajinshan Buddhist Academy for Nuns. Religions 2022, 13, 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111020

Campo D. Female Education in a Chan Public Monastery in China: The Jiangxi Dajinshan Buddhist Academy for Nuns. Religions. 2022; 13(11):1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111020

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampo, Daniela. 2022. "Female Education in a Chan Public Monastery in China: The Jiangxi Dajinshan Buddhist Academy for Nuns" Religions 13, no. 11: 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111020

APA StyleCampo, D. (2022). Female Education in a Chan Public Monastery in China: The Jiangxi Dajinshan Buddhist Academy for Nuns. Religions, 13(11), 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111020