The Buffering Effect of Spirituality at Work on the Mediated Relationship between Job Demands and Turnover Intention among Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Job Demands and Turnover Intention

1.2. Burnout as a Mediator between Job Demands and Turnover Intention

1.3. Spirituality at Work as a Moderating Resource

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Quantitative and Emotional Job Demands

2.2.2. Spirituality at Work

2.2.3. Burnout

2.2.4. Turnover Intention

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Missing Data Analysis

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Mediation Models

3.3.1. Model 4a: Quantitative Job Demands, Burnout, and Turnover Intention

3.3.2. Model 4b: Emotional Job Demands, Burnout, and Turnover Intention

3.4. Moderated Mediation Models

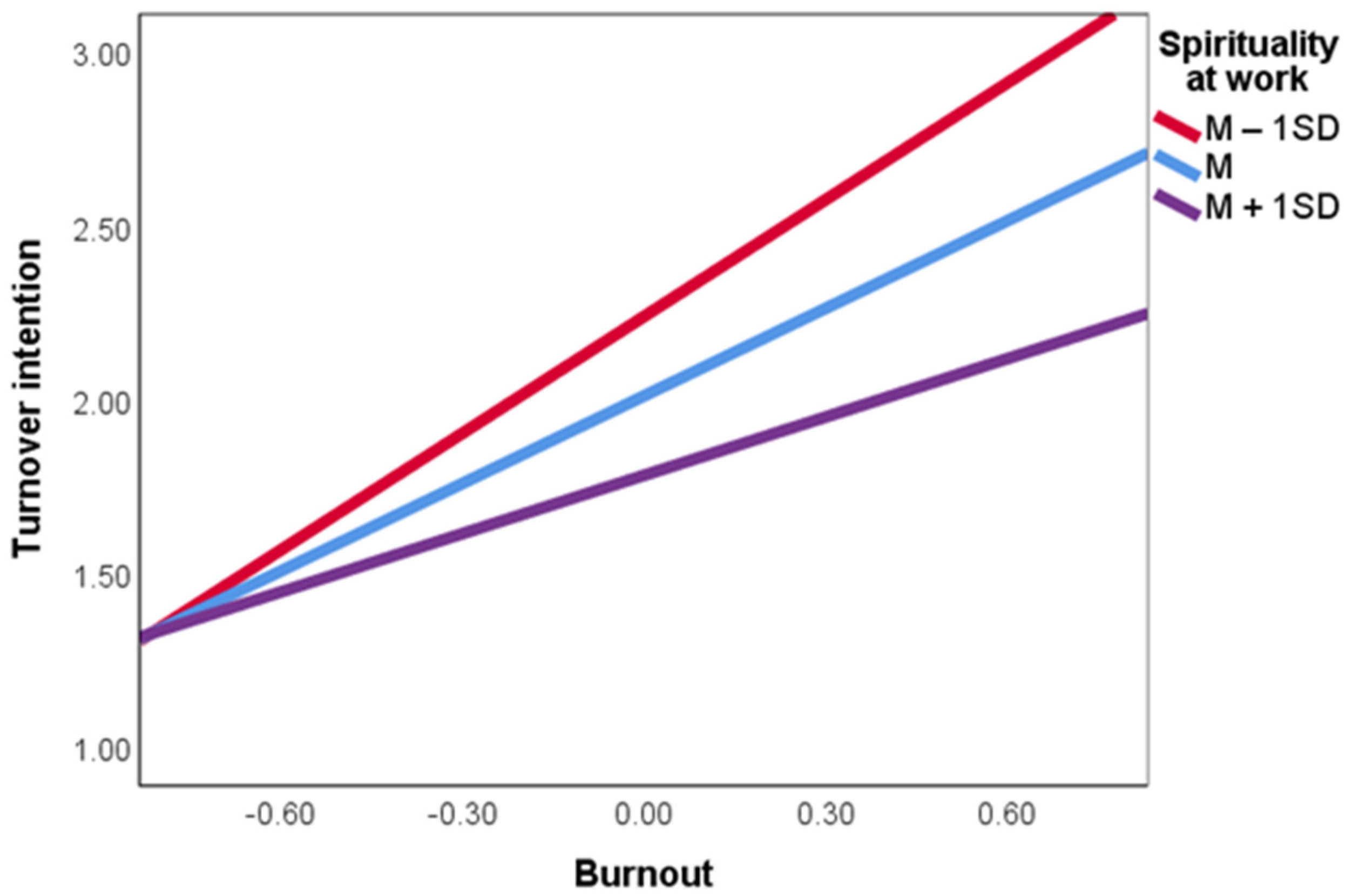

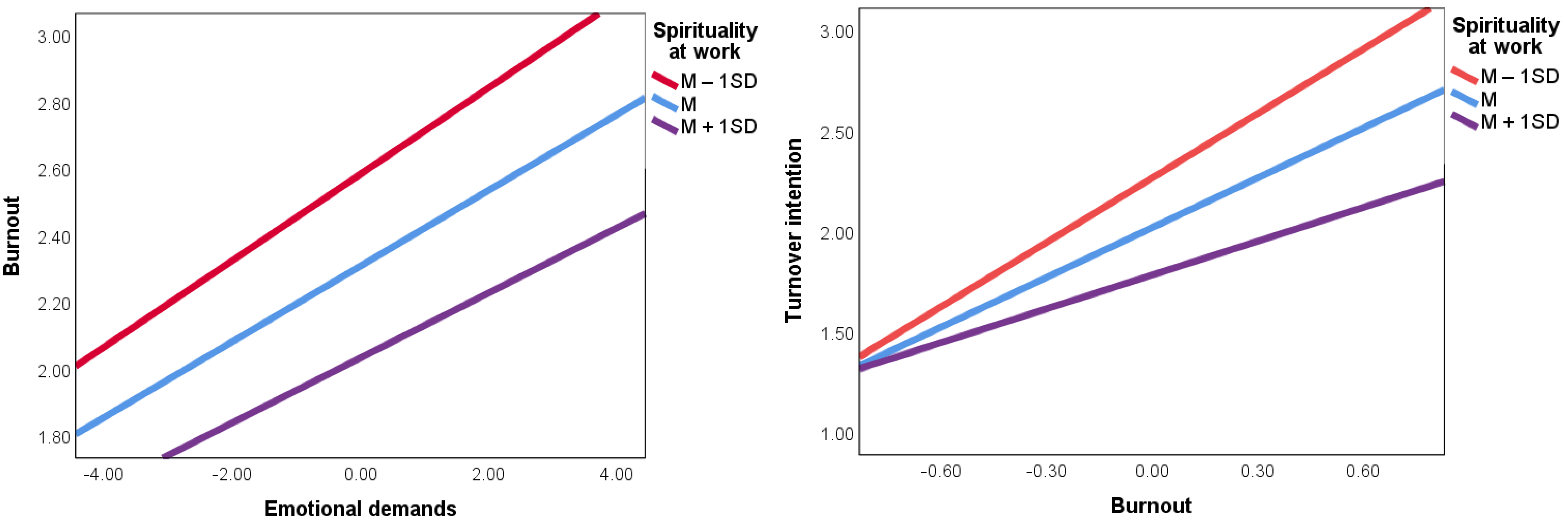

3.4.1. Model 59a: Spirituality as a Moderator of the Relationships between Quantitative Job Demands, Burnout, and Turnover Intention

3.4.2. Model 59b: Spirituality as a Moderator of the Relationships between Emotional Job Demands, Burnout, and Turnover Intention

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboobaker, Nimitha, Manoj Edward, and K. A. Zakkariya. 2019. Workplace Spirituality, Employee Wellbeing and Intention to Stay: A Multi-Group Analysis of Teachers’ Career Choice. International Journal of Educational Management 33: 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affrunti, Nicholas W., Tara Mehta, Dana Rusch, and Stacy Frazier. 2018. Job Demands, Resources, and Stress Among Staff in after School Programs: Neighborhood Characteristics Influence Associations in the Job Demands-Resources Model. Children and Youth Services Review 88: 366–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, Bilal, Yuosre Badir, and Umar S. Kiani. 2016. Linking Spiritual Leadership and Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Influence of Workplace Spirituality, Intrinsic Motivation, and Environmental Passion. Journal of Environmental Psychology 45: 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, Leona S., and Stephen G. West. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Joseph A., and Stephanie L. Mueller. 2013. The Revolving Door: A Closer Look at Major Factors in Volunteers’ Intention to Quit. Journal of Community Psychology 41: 139–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, Amal, and Mohammad A. Awan. 2011. Moderating Affect of Workplace Spirituality on the Relationship of Job Overload and Job Satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics 104: 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, Matthew R., and Tamar Mendelson. 2014. Feasibility and Preliminary Outcomes of a Yoga and Mindfulness Intervention for School Teachers. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion 7: 156–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansley, Brandis M., David E. Houchins, Kris Varjas, Andrew Roach, DaShaunda Patterson, and Robert Hendrick. 2021. The Impact of an Online Stress Intervention on Burnout and Teacher Efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education 98: 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, Alexander-Stamatios, Aikaterini Ploumpi, and Marina Ntalla. 2013. Occupational Stress and Professional Burnout in Teachers of Primary and Secondary Education: The Role of Coping Strategies. Psychology 4: 349–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmos, Donde P., and Dennis Duchon. 2000. Spirituality at Work. Conceptualization and Measure. Journal of Management Inquiry 9: 134–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azharudeen, N.T., and Anton A. Arulrajah. 2018. The Relationships among Emotional Demand, Job Demand, Emotional Exhaustion and Turnover Intention. International Business Research 11: 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, Łukasz. 2015. Does Job Burnout Mediate Negative Effects of Job Demands on Mental and Physical Health in a Group of Teachers? Testing the Energetic Process of Job Demands-Resources Model. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health 28: 335–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baka, Łukasz. 2019. Kopenhaski Kwestionariusz Psychospołeczny (COPSOQ II). Podręcznik do Polskiej Wersji Narzędzia. Warszawa: CIOP-PIB. [Google Scholar]

- Baka, Łukasz, and Beata A. Basinska. 2016. Psychometric Properties of the Polish Version of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI). Medycyna Pracy 67: 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, and Martin C. Euwema. 2005. Job Resources Buffer the Impact of Job Demands on Burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 10: 170–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Jari J. Hakanen, Evangelia Demerouti, and Despoina Xanthopoulou. 2007. Job Resources Boost Work Engagement, Particularly When Job Demands Are High. Journal of Educational Psychology 99: 274–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhuizen, Nicolene, Sebastiaan Rothmann, and Fons Van de Vijver. 2014. Burnout and Work Engagement of Academics in Higher Education Institutions: Effects of Dispositional Optimism. Stress and Health 30: 322–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, Joachim, Axel Stamm, Katharina Virnich, Karen Wissing, Udo Müller, Michael Wirsching, and Uwe Schaarschmidt. 2006. Correlation between Burnout Syndrome and Psychological and Psychosomatic Symptoms among Teachers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 79: 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickerton, Grant R., Maureen H. Miner, Martin Dowson, and Barbara Griffin. 2014. Spiritual Resources in the Job Demands-Resources Model. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 11: 245–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, Grayson, and Stef M. Shuster. 2020. Emotional Labour, Teaching and Burnout: Investigating Complex Relationships. Educational Research 62: 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, Geoffrey D., and N. Maritza Dowling. 2008. Teacher Attrition and Retention: A Meta-Analytic and Narrative Review of the Research. Review of Educational Research 78: 367–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, Arthur P., and Walter R. Nord. 1990. Work and Meaning: Definitions and Interpretations. In Meanings of Occupational Work: A Collection of Essays. Edited by Arthur P. Brief and Walter R. Nord. Lexington: Lexington Books, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brotheridge, Céeste M., and Raymond T. Lee. 2002. Testing a Conservation of Resources Model of the Dynamics of Emotional Labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 7: 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, Stephanie, Joanna Napierala, Antonis Bessios, Eve Mägi, Agnieszka Pugacewicz, Maria Ranieri, Karen Triquet, Koen Lombaerts, Nicolas Robledo Bottcher, Marco Montanari, and et al. 2021. What Did We Learn from Schooling Practices During the COVID-19 Lockdown. EUR 30559 EN. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, Karen C., and George R. Gray. 2000. A Framework for Accommodating Religion and Spirituality in the Workplace. Academy of Management Perspectives 14: 124–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Education Development. 2013. Nauczyciele w Roku Szkolnym 2012/2013. Available online: http://bc.ore.edu.pl/Content/631/raport+nauczyciele+2012-2013_do+BC.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Centre for Public Opinion Research. 2020. Religijność Polaków w Ostatnich 20 Latach. Available online: https://cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2020/K_063_20.PDF (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Chang, Mei-Lin. 2009. An Appraisal Perspective of Teacher Burnout: Examining the Emotional Work of Teachers. Educational Psychology Review 21: 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charzyńska, Edyta, and Agata Gardzioła. 2015. Duchowość w pracy jako czynnik chroniący przed wypaleniem zawodowym–mediacyjna rola satysfakcji z pracy. Humanizacja Pracy 2: 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ching-Fu, and Ting Yu. 2014. Effects of Positive vs Negative Forces on the Burnout-Commitment-Turnover Relationship. Journal of Service Management 25: 388–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Zhen J., Xi Zhang, and Douglas Vogel. 2011. Exploring the Underlying Processes between Conflict and Knowledge Sharing: A Work-Engagement Perspective 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 41: 1005–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, Francesco, Manoj Sharma, Salvatore Zaffina, and Nicola Magnavita. 2020. Spirituality and Prayer on Teacher Stress and Burnout in an Italian Cohort: A Pilot, Before-After Controlled Study. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmura-Rutkowska, Iwona, Marcin Korczyc, and Wiktoria Niedzielska-Galant. 2020. Powrót do Szkoły–Obawy i Potrzeby Środowiska Nauczycielskiego. Raport z Wyników Sondażu Ja, Nauczyciel. Available online: https://ja-nauczyciel.pl/news/nauczycielskie-obawy-raport-ja-nauczyciel (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Chughtai, Aamir A. 2013. Linking Affective Commitment to Supervisor to Work Outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology 28: 606–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D. Jean, Julie Long, Lee Schaefer, C. Aiden Downey, Pam Steeves, Eliza Pinnegar, Sue McKenzie Robblee, and Sheri Wnuk. 2015. Early Career Teacher Attrition: Intentions of Teachers Beginning. Teaching Education 26: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Corso, Laura, Alessandro De Carlo, Francesca Carluccio, Daiana Colledani, and Alessandra Falco. 2020. Employee Burnout and Positive Dimensions of Well-Being: A Latent Workplace Spirituality Profile Analysis. PLoS ONE 15: e0242267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, Charlotte. 2013. The Framework for Teaching Evaluation Instrument, 2013 Instructionally Focused Edition. Available online: https://usny.nysed.gov/rttt/teachers-leaders/practicerubrics/Docs/danielson-teacher-rubric-2013-instructionally-focused.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- De Carlo, Alessandro, Damiano Girardi, Alessandra Falco, Laura Dal Corso, and Annamaria Di Sipio. 2019. When Does Work Interfere with Teachers’ Private Life? An Application of the Job Demands-Resources Model. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, Jan, and Christian Dormann. 2003. The DISC Model: Demand-Induced Strain Compensation Mechanisms in Job Stress. In Occupational Stress in the Service Professions. Edited by Maureen F. Dollard, Anthony H. Winefield and Helen R. Winefield. London: Taylor & Francis, pp. 43–74. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Friedhelm Nachreiner, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2001. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Ioanna Vardakou, and Aristotelis Kantas. 2003. The Convergent Validity of Two Burnout Instruments: A Multitrait-Multimethod Analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 19: 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Karina Mostert, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2010. Burnout and Work Engagement: A Thorough Investigation of the Independency of Both Constructs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 15: 209–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmes, Michael, and Charles Smith. 2001. Moved by the Spirit: Contextualizing Workplace Empowerment in American Spiritual Ideals. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 37: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, Barry A. 1991. Crisis in Education: Stress and Burnout in the American Teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Federičová, Miroslava. 2021. Teacher Turnover: What Can We Learn from Europe? European Journal of Education 56: 102–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouché, Elmari, Sebastiaan Rothmann, and Corne Van der Vyver. 2017. Antecedents and Outcomes of Meaningful Work among School Teachers. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 43: a1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, Louis W. 2003. Toward a Theory of Spiritual Leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 14: 693–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, Michael. 2014. Assessing the Incremental Validity of Spirituality in Predicting Nurses’ Burnout. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 36: 118–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, Tray, and Margarita Pivovarova. 2018. The Effects of Working Conditions on Teacher Retention. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 24: 604–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadi, Mohammed Y. 2017. The Impact of Workplace Spirituality on Voluntary Turnover Intentions through Loneliness in Work. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences 33: 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, Robert A., and Carole L. Jurkiewicz. 2003. Right from Wrong: The Influence of Spirituality on Perceptions of Unethical Business Activities. Journal of Business Ethics 46: 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsis, George, and Zoi Kortezi. 2008. Philosophical Foundations of Workplace Spirituality: A Critical Approach. Journal of Business Ethics 78: 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, Rodger W., Peter W. Hom, and Stefan Gaertner. 2000. A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Correlates of Employee Turnover: Update, Moderator Tests, and Research Implications for the Next Millennium. Journal of Management 26: 463–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, Cassandra M., Lucrecia Santibañez, and Glenn A. Daley. 2006. Teacher Recruitment and Retention: A Review of the Recent Empirical Literature. Review of Educational Research 76: 173–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, Jari J., Arnold B. Bakker, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2006. Burnout and Work Engagement among Teachers. Journal of School Psychology 43: 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, Jari J., Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Kirsi Ahola. 2008. The Job Demands-Resources Model: A Three-Year Cross-Lagged Study of Burnout, Depression, Commitment, and Work Engagement. Work & Stress 22: 224–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsten, Lennart, Katalin Bellaagh, and Klas Gustafsson. 2002. Utbränning i Sverige—En Populationsstudie. Stockholm: Arbetslivsinstitutet. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hee, Cordelia H.S., and Florence Y.Y. Ling. 2011. Strategies for Reducing Employee Turnover and Increasing Retention Rates of Quantity Surveyors. Construction Management and Economics 29: 1059–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. 2001. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Applied Psychology 50: 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Robert J. Johnson, Nicole Ennis, and Anita P. Jackson. 2003. Resource Loss, Resource Gain, and Emotional Outcomes among Inner City Women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 632–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Ji Y. 2010. Pre-Service and Beginning Teachers’ Professional Identity and Its Relation to Dropping out of the Profession. Teaching and Teacher Education 26: 1530–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Young J. 2012. Identifying Spirituality in Workers: A Strategy for Retention of Community Mental Health Professionals. Journal of Social Service Research 38: 175–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Xiumin, Qianqian Liu, and Mingzhu Zhang. 2021. Dual Stressors and Female Pre-School Teachers’ Job Satisfaction during the COVID-19: The Mediation of Work-Family Conflict. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 691498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 26.0. Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, Richard M. 2001. Teacher Turnover and Teacher Shortages: An Organizational Analysis. American Educational Research Journal 38: 499–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Brenda R., and Cindy S. Bergeman. 2011. How Does Religiosity Enhance Well-Being? The Role of Perceived Control. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 149–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janik, Manfred, and Sebastiaan Rothmann. 2015. Meaningful Work and Secondary School Teachers’ Intention to Leave. South African Journal of Education 35: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Maria T. 2021. Pupil-Teacher Ratio, Disciplinary Problems, Classroom Emotional Climate, and Turnover Intention: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial. Teaching and Teacher Education 105: 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, Fahri. 2010. Spirituality and Performance in Organizations: A Literature Review. Journal of Business Ethics 94: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppinen, Timo, Rauno Hanhela, Irja Kandolin, Antti Karjalainen, Antti Kasvio, Merja Perkiö-Mäkelä, Eero Priha, Jouni Toikkanen, and Marja Viluksela. 2010. Työ ja Terveys Suomessa 2009. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, David A. 2018. Moderation. Available online: http://davidakenny.net/cm/moderation.htm (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Kenny, David A. 2021. Mediation. Available online: http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Khasawneh, Samer. 2011. Learning Organization Disciplines in Higher Education Institutions: An Approach to Human Resource Development in Jordan. Innovative Higher Education 36: 273–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Lisa E., and Kathryn Asbury. 2020. ‘Like a Rug Had Been Pulled from Under You’: The Impact of COVID-19 on Teachers in England during the First Six Weeks of the UK Lockdown. British Journal of Educational Psychology 90: 1062–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Youngmee, and Larry Seidlitz. 2002. Spirituality Moderates the Effect of Stress on Emotional and Physical Adjustment. Personality and Individual Differences 32: 1377–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Joungyoun, Yeoul Shin, Eli Tsukayama, and Daeun Park. 2020. Stress Mindset Predicts Job Turnover Among Preschool Teachers. Journal of School Psychology 78: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, Pamela E., Jennifer M. Vaughn, Yeonsoo Yoo, Jonathan M. Tirrell, Elizabeth M. Dowling, Richard M. Lerner, John G. Geldhof, Jacqueline V. Lerner, Guillermo Iraheta, Kate Williams, and et al. 2020. Exploring Religiousness and Hope: Examining the Roles of Spirituality and Social Connections among Salvadoran Youth. Religions 11: 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinjerski, Val M. 2013. The Spirit at Work Scale: Developing and Validating a Measure of Individual Spirituality at Work. In Handbook of Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace: Emerging Research and Practice. Edited by Judi Neal. New York: Springer, pp. 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinjerski, Val M., and Berna J. Skrypnek. 2004. Defining Spirit at Work: Finding Common Ground. Journal of Organizational Change Management 17: 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinjerski, Val M., and Berna J. Skrypnek. 2006. Measuring the Intangible: Development of the Spirit at Work Scale. Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings 1: A1–A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodinsky, Robert W., Robert A. Giacalone, and Carole L. Jurkiewicz. 2008. Workplace Values and Outcomes: Exploring Personal, Organizational, and Interactive Workplace Spirituality. Journal of Business Ethics 81: 465–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosi, Isaac, Ibrahim Sulemana, Janet S. Boateng, and Robert Mensah. 2015. Teacher Motivation and Job Satisfaction on Intention to Quit: An Empirical Study in Public Second Cycle Schools in Tamale Metropolis, Ghana. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 5: 839–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, Tage S., Harald Hannerz, Annie Høgh, and Vilhelm Borg. 2005. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire—A Tool for the Assessement and Improvement of the Psychosocial Work Environment. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 31: 438–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Vineet, and Sandeep Kumar. 2014. Workplace Spirituality as a Moderator in Relation between Stress and Health: An Exploratory Empirical Assessment. International Review of Psychiatry 26: 344–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, Chris. 2001. Teacher Stress: Directions for Future Research. Educational Review 53: 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Eric, and Nancy Hogan. 2009. The Importance of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Shaping Turnover Intent: A Test of a Causal Model. Criminal Justice Review 34: 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Richard, and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lips-Wiersma, Marjolein, Kathy Lund Dean, and Charles J. Fornaciari. 2009. Theorizing the Dark Side of the Workplace Spirituality Movement. Journal of Management Inquiry 18: 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Roderick J.A. 1988. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83: 1198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Shujie, and Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie. 2012. Chinese Teachers’ Work Stress and Their Turnover Intention. International Journal of Educational Research 53: 160–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente, Laura, Marisa Salanova, Isabel Martínez, and Wilmar Schaufeli. 2008. Extension of the Job Demands-Resources Model in the Prediction of Burnout and Engagement among Teachers over Time. Psicothema 20: 354–60. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, Doune. 1999. Teacher Attrition: A Review of Literature. Teaching and Teacher Education 15: 835–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, Daniel J., and Lisa E. Kim. 2021. Towards an Understanding of Teacher Attrition: A Meta-Analysis of Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Teachers’ Intentions to Quit. Teaching and Teacher Education 105: 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, Christina. 2017. Finding Solutions to the Problem of Burnout. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 69: 143–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, Christina, and Michael P. Leiter. 1999. Teacher Burnout: A Research Agenda. In Understanding and Preventing Teacher Burnout: A Sourcebook of International Research and Practice. Edited by Roland Vandenberghe and A. Michael Huberman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, Christina, Susan E. Jackson, and Michael P. Leiter. 1996. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Mountain View: CPP, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- May, Douglas R., Richard L. Gilson, and Lynn M. Harter. 2004. The Psychological Conditions of Meaningfulness, Safety and Availability and the Engagement of the Human Spirit at Work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 77: 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloum, Adel, Masaharu Kumashiro, Hiroyuki Izumi, and Yoshiyuki Higuchi. 2008. Quantitative Overload: A Source of Stress in Data-Entry VDT Work Induced by Time Pressure and Work Difficulty. Industrial Health 46: 269–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michniuk, Anna. 2021. Dlaczego współcześni nauczyciele rezygnują z pracy w szkołach państwowych? Raport z badań. Rocznik Pedagogiczny 43: 153–65. Available online: https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/rp/article/view/28381 (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Milliman, John, Andrew J. Czaplewski, and Jeffery Ferguson. 2003. Workplace Spirituality and Employee Work Attitudes: An Exploratory Empirical Assessment. Journal of Organizational Change Management 16: 426–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näring, Gérard, Mariette Briët, and André Brouwers. 2006. Beyond Demand–Control: Emotional Labour and Symptoms of Burnout in Teachers. Work & Stress 20: 303–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, Noraini M., and Masyitah Zainuddin. 2011. Emotional Labor and Burnout among Female Teachers: Work–Family Conflict as Mediator. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 14: 283–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, Emmanuel, and Lloyd C. Harris. 2004. Work Intensification and Emotional Labour among UK University Lecturers: An Exploratory Study. Organization Studies 25: 1185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oman, Doug. 2013. Defining Religion and Spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2nd ed. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guildford Press, pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian, Raymond F., and Crystal L. Park. 2005. Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian, Raymond F., Robert A. Emmons, and Susan G. Keortge. 2003. Spiritual Well-Being, Spiritual Intelligence, and Healthy Workplace Policy. In Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance. Edited by Robert A. Giacalone and Carole L. Jurkiewicz. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe, pp. 123–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L., Lawrence H. Cohen, and Lisa Herb. 1990. Intrinsic Religiousness and Religious Coping as Life Stress Moderators for Catholics versus Protestants. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59: 562–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietarinen, Janne, Kirsi Pyhältö, Tiina Soini, and Katariina Salmela-Aro. 2013. Reducing Teacher Burnout: A Socio-Contextual Approach. Teaching and Teacher Education 35: 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Ken Kelley. 2011. Effect Size Measures for Mediation Models: Quantitative Strategies for Communicating Indirect Effects. Psychological Methods 16: 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, James C., and Debra L. Nelson. 2011. Principles of Organizational Behavior: Realities and Challenges. London: South-Western Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Räsänen, Katariina, Janne Pietarinen, Kirsi Pyhältö, Tiina Soini, and Pertti Väisänen. 2020. Why Leave the Teaching Profession? A Longitudinal Approach to the Prevalence and Persistence of Teacher Turnover Intentions. Social Psychology of Education 23: 837–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravalier, Jermaine M., and Joseph Walsh. 2017. Scotland’s Teachers: Working Conditions and Wellbeing. Bath: Bath Spa University. [Google Scholar]

- Rego, Arménio, and Miguel Pina e Cunha. 2008. Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Commitment: An Empirical Study. Journal of Organizational Change Management 21: 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfeldt, Matthew, Susanna Loeb, and James Wyckoff. 2013. How Teacher Turnover Harms Student Achievement. American Educational Research Journal 50: 4–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagioni, Denise A.J., Francine N. Melanda, Arthur E. Mesas, Alberto D. González, Flávia L. Gabani, and Selma M. De Andrade. 2017. Physical, Psychological and Occupational Consequences of Job Burnout: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. PLoS ONE 12: e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santavirta, Nina, Svetlana Solovieva, and Töres Theorell. 2011. The Association between Job Strain and Emotional Exhaustion in a Cohort of 1028 Finnish Teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology 77: 213–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlan, Justin N., and Megan Still. 2019. Relationships between Burnout, Turnover Intention, Job Satisfaction, Job Demands and Job Resources for Mental Health Personnel in an Australian Mental Health Service. BMC Health Services Research 19: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Arnold B. Bakker. 2004. Job Demands, Job Resources, and Their Relationship with Burnout and Engagement: A Multi-Sample Study. Journal of Organizational Behaviour 25: 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, Lisa L., Joseph A. Allen, and Elizabeth R. Harp. 2016. Grin and Bear it: An Examination of Yolunteers’ Fit with Their Organization, Burnout and Spirituality. Burnout Research 3: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeps, Konstanze, Alicia Tamarit, Usue de la Barrera, and Remedios González Barrón. 2019. Effects of Emotional Skills Training to Prevent Burnout Syndrome in Schoolteachers. Ansiedad y Estrés 25: 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, Irvin S. 2001. Stress in 1st-Year Women Teachers: The Context of Social Support and Coping. Genetic Social and General Psychology Monographs 127: 133–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sekułowicz, Małgorzata. 2002. Wypalenie Zawodowe Nauczycieli Pracujących z Osobami z Niepełnosprawnością Intelektualną. Przyczyny–Symptomy–Zapobieganie–Przezwyciężanie. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp Donahoo, Lori M., Beverly Siegrist, and Dawn Garrett-Wright. 2018. Addressing Compassion Fatigue and Stress of Special Education Teachers and Professional Staff Using Mindfulness and Prayer. The Journal of School Nursing 34: 442–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Adnan, Aneeq Inam, Anila Rubab, Usama Najam, Naeem A. Rana, and Hayat M. Awan. 2019. The Spiritual Role of a Leader in Sustaining Work Engagement: A Teacher-Perceived Paradigm. SAGE Open 9: 2158244019863567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Bo, Nate McCaughtry, Jeffrey Martin, Alex Garn, Noel Kulik, and Mariane Fahlman. 2015. The Relationship Between Teacher Burnout and Student Motivation. British Journal of Educational Psychology 85: 519–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, Arjun K., and Lalatendu K. Jena. 2021. Interactive Effects of Workplace Spirituality and Psychological Capital on Employee Negativity. Management and Labour Studies 46: 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, Patrick E., and Niall Bolger. 2002. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychological Methods 7: 422–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbula, Silvia. 2010. Daily Fluctuations in Teachers’ Well-Being: A Diary Study Using the Job Demands–Resources Model. Anxiety, Stress & Coping 23: 563–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, Einar M., and Sidsel Skaalvik. 2014. Teacher Self-Efficacy and Perceived Autonomy: Relations with Teacher Engagement, Job Satisfaction, and Emotional Exhaustion. Psychological Reports 114: 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, Einar M., and Sidsel Skaalvik. 2018. Job Demands and Job Resources as Predictors of Teacher Motivation and Well-Being. Social Psychology of Education 21: 1251–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, Einar M., and Sidsel Skaalvik. 2020. Teacher Burnout: Relations between Dimensions of Burnout, Perceived School Context, Job Satisfaction and Motivation for Teaching. A longitudinal study. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 26: 602–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, Laura, Lesley E. Trudel, and Jeff Babb. 2021. I’ve Had It! Factors Associated with Burnout and Low Organizational Commitment in Canadian Teachers during the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research Open 2: 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Poza, Alfonso, and Fred Henneberger. 2004. Analyzing Job Mobility with Job Turnover Intentions: An International Comparative Study. Journal of Economic 38: 113–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, Paul E., Daniel J. Dwyer, and Steve M. Jex. 1988. Relation of Job Stressors to Affective, Health, and Performance Outcomes: A Comparison of Multiple Data Sources. Journal of Applied Psychology 73: 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprung, Justin M., Michael T. Sliter, and Steve M. Jex. 2012. Spirituality as a Moderator of the Relationship between Workplace Aggression and Employee Outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences 53: 930–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmokienė, Aurelija, Giedrė Genevičiūtė-Janonė, Loreta Gustainiene, and Kristina Kovalčikienė. 2019. Job Demands-Resources and Personal Resources as Risk and Safety Factors for the Professional Burnout among University Teachers. Pedaogika 134: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Struyven, Katrien, and Gert Vanthournout. 2014. Teachers’ Exit Decisions: An Investigation into the Reasons Why Newly Qualified Teachers Fail to Enter the Teaching Profession or Why Those Who Do Enter Do Not Continue Teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education 43: 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swider, Brian W., and Ryan D. Zimmerman. 2010. Born to Burnout: A Meta-Analytic Path Model of Personality, Job Burnout, and Work Outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior 76: 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Stephen G., Alex M. Roberts, and Nicole Zarrett. 2021. A Brief Mindfulness-Based Intervention (bMBI) to Reduce Teacher Stress and Burnout. Teaching and Teacher Education 100: 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troesch, Larissa. M., and Catherine E. Bauer. 2020. Is Teaching Less Challenging for Career Switchers? First and Second Career Teachers’ Appraisal of Professional Challenges and Their Intention to Leave Teaching. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucholska, Stanisława. 2003. Wypalenie Zawodowe Nauczycieli. Lublin: KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Tuxford, Linda M., and Graham L. Bradley. 2015. Emotional Job Demands and Emotional Exhaustion in Teachers. Educational Psychology 35: 1006–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, Beatrice, Christine Brown Mahoney, and Yingzi Xu. 2019. Impact of Job Demands and Resources on Nurses’ Burnout and Occupational Turnover Intention towards an Age-Moderated Mediation Model for the Nursing Profession. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, Filip, Bram Spruyt, and Christophe Vanroelen. 2014. Burnout among Senior Teachers: Investigating the Role of Workload and Interpersonal Relationships at Work. Teaching and Teacher Education 43: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vegchel, Natasja, Jan De Jonge, Marie Söderfeldt, Christian Dormann, and Wilmar Schaufeli. 2004. Quantitative versus Emotional Demands among Swedish Human Service Employees: Moderating Effects of Job Control and Social Support. International Journal of Stress Management 11: 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, Jessica, and Rob F. Poell. 2019. Meaningful Work and Resilience among Teachers: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement and Job Crafting. PLoS ONE 14: e0222518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, Jessica, and Joost Van der Stoep. 2018. The Motivational Potential of Meaningful Work: Relationships with Strengths Use, Work Engagement, and Performance. PLoS ONE 13: e0197599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, Jessica, Daantje Derks, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2017. The Impact of Personal Resources and Job Crafting Interventions on Work Engagement and Performance. Human Resource Management 56: 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watlington, Eliah, Robert Shockley, Paul Guglielmino, and Rivka A. Felsher. 2010. The High Cost of Leaving: An Analysis of the Cost of Teacher Turnover. Journal of Education Finance 36: 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, Despoina, Arnold B. Bakker, Maureen F. Dollard, Evangelia Demerouti, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, Toon W. Taris, and Paul J. G. Schreurs. 2007a. When Do Job Demands Particularly Predict Burnout? The Moderating Role of Job Resources. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 766–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, Despoina, Arnold B. Bakker, Evangelia Demerouti, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2007b. The Role of Personal Resources in the Job Demands-Resources Model. International Journal of Stress Management 14: 121–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Mari, and Louis W. Fry. 2018. The Role of Spiritual Leadership in Reducing Healthcare Worker Burnout. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 15: 305–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Hongbiao. 2015. The Effect of Teachers’ Emotional Labour on Teaching Satisfaction: Moderation of Emotional Intelligence. Teachers and Teaching 21: 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, Dieter. 2002. Emotion Work and Psychological Well-Being. A Review of the Literature and Some Conceptual Considerations. Human Resource Management Review 12: 237–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., Kenneth I. Pargament, and Allie B. Scott. 1999. The Emerging Meanings of Religiousness and Spirituality: Problems and Prospects. Journal of Personality 67: 889–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Wen-Chi, and Jason Dahling. 2017. Workplace Spirituality Buffers the Effects of Emotional Labour on Employee Well-Being. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 26: 768–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 834 | 87.6 |

| Male | 118 | 12.4 |

| Age (M ± SD) | 46.54 | 9.59 |

| Religion | ||

| Religious | 747 | 78.5 |

| Non-religious | 51 | 5.3 |

| Agnostic | 142 | 14.9 |

| N/A | 12 | 1.3 |

| Relationship status a | ||

| Formal or informal relationship | 751 | 78.9 |

| Single | 106 | 11.1 |

| Divorced | 58 | 6.1 |

| Separated | 10 | 1.1 |

| Widow/widower | 20 | 6.1 |

| N/A | 1 | 0.1 |

| Job seniority (M ± SD) | 21.12 | 11.29 |

| School | ||

| Primary | 816 | 85.7 |

| Secondary | 136 | 14.3 |

| Type of school | ||

| Public | 913 | 95.9 |

| Private | 33 | 3.5 |

| N/A | 6 | 0.6 |

| Number of pupils in a school | ||

| <50 | 9 | 1.0 |

| 50–200 | 240 | 25.2 |

| 200–500 | 436 | 45.8 |

| 500–1000 | 243 | 25.5 |

| >1000 | 16 | 1.7 |

| N/A | 8 | 0.8 |

| Location of school | ||

| Village | 276 | 29.0 |

| Town with up to 20,000 inhabitants | 170 | 17.8 |

| Town with 20,000–100,000 inhabitants | 213 | 22.4 |

| Town with more than 100,000 inhabitants | 290 | 30.5 |

| N/A | 3 | 0.3 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Quantitative demands | 1 | ||||||

| (2) Emotional demands | 0.56 *** | 1 | |||||

| (3) Spirituality at work | −0.13 *** | −0.05 | 1 | ||||

| (4) Burnout | 0.41 *** | 0.37 *** | −0.44 *** | 1 | |||

| (5) Turnover Intention | 0.29 *** | 0.29 *** | −0.40 *** | 0.54 *** | 1 | ||

| (6) Gender a | 0.04 | −0.09 ** | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 * | 1 | |

| (7) Job seniority (years) | 0.07 * | 0.08 * | 0.12 *** | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 1 |

| M | 9.16 | 11.27 | 54.91 | 2.31 | 2.09 | 87.6% a | 21.12 |

| SD | 2.30 | 2.04 | 12.84 | 0.66 | 1.36 | – | 11.29 |

| Range | 3–15 | 3–15 | 13–78 | 1–4 | 1–6 | – | 1–52 |

| Outcome: Burnout | Outcome: Turnover Intention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | b | SE | t | b | SE | t |

| Model 59a | ||||||

| Quantitative demands (quant. dem.) | 0.101 | 0.008 | 13.04 *** | 0.061 | 0.017 | 3.57 *** |

| Spirituality (spir.) | −0.020 | 0.001 | −14.50 *** | −0.018 | 0.003 | −5.58 *** |

| Interaction 1 (quan. dem. × spir.) | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.70 | |||

| Gender | −0.003 | 0.054 | −0.06 | 0.169 | 0.108 | 1.56 |

| Job seniority | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.33 | −0.002 | 0.003 | −0.61 |

| Burnout (burn.) | 0.840 | 0.066 | 12.75 *** | |||

| Interaction 2 (quant. dem. × spir.) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.16 | |||

| Interaction 3 (burn. × spir.) | −0.022 | 0.004 | −5.02 *** | |||

| R | 0.564 | 0.591 | ||||

| R2 | 0.318 | 0.350 | ||||

| F statistic | F(5, 946) = 88.13; p < 0.001 | F(7, 944) = 72.54; p < 0.001 | ||||

| Model 59b | ||||||

| Emotional demands (emo. dem.) | 0.114 | 0.009 | 13.06 *** | 0.089 | 0.019 | 4.66 *** |

| Spirituality (spir.) | −0.021 | 0.001 | −15.53 *** | −0.019 | 0.003 | −6.05 *** |

| Interaction 1 (emo. dem. × spir.) | −0.001 | 0.001 | −2.15 * | |||

| Gender | 0.089 | 0.054 | 1.65 | 0.229 | 0.109 | 2.10 * |

| Job seniority | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.41 | −0.002 | 0.003 | −0.66 |

| Burnout (burn.) | 0.816 | 0.066 | 12.38 *** | |||

| Interaction 2 (emo. dem. × spir.) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.85 | |||

| Interaction 3 (burn. × spir.) | −0.020 | 0.004 | −4.52 *** | |||

| R | 0.567 | 0.596 | ||||

| R2 | 0.321 | 0.356 | ||||

| F statistic | F(5, 946) = 89.54; p < 0.001 | F(7, 944) = 74.40; p < 0.001 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charzyńska, E.; Polewczyk, I.; Góźdź, J.; Kitlińska-Król, M.; Sitko-Dominik, M. The Buffering Effect of Spirituality at Work on the Mediated Relationship between Job Demands and Turnover Intention among Teachers. Religions 2021, 12, 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090781

Charzyńska E, Polewczyk I, Góźdź J, Kitlińska-Król M, Sitko-Dominik M. The Buffering Effect of Spirituality at Work on the Mediated Relationship between Job Demands and Turnover Intention among Teachers. Religions. 2021; 12(9):781. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090781

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharzyńska, Edyta, Irena Polewczyk, Joanna Góźdź, Małgorzata Kitlińska-Król, and Magdalena Sitko-Dominik. 2021. "The Buffering Effect of Spirituality at Work on the Mediated Relationship between Job Demands and Turnover Intention among Teachers" Religions 12, no. 9: 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090781

APA StyleCharzyńska, E., Polewczyk, I., Góźdź, J., Kitlińska-Król, M., & Sitko-Dominik, M. (2021). The Buffering Effect of Spirituality at Work on the Mediated Relationship between Job Demands and Turnover Intention among Teachers. Religions, 12(9), 781. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090781