1. Introduction

I am a Hindu because I was born and brought up as a Hindu, but I am also an atheist and I mostly go to the temple for social reasons. But I do like some of the things that the Hindu culture represents—you know openness to other cultures etcetera.

This is what a young Sri Lankan Tamil man answered when I asked him about his relationship to the Hindu tradition. He was born in Sri Lanka, but grew up in Denmark, and is one of the many young Hindus in this country who try to find anchoring points to a tradition to which they feel attached, owing to their birth and upbringing, in a way that suits their lives in a Danish context.

His statement is of course not representative for all Hindus living in Denmark—it is one answer out of many possible

1—but it gives an example of one pole of the very wide spectrum that we have to take into consideration when dealing with Hinduism in Europe. And while his answer shows that his link to Hinduism is defined mostly culturally, socially or ethnically rather than religiously, other people who are Hindus by birth and of either Indian, Sri Lankan or Nepalese background now living in Denmark argue just the opposite. Unlike him, they link to what they call the religious dimension in the Hindu tradition and downplay part of the national–cultural link, which they tend to associate with “Danishness”. A litmus test for them is that they feel Danish when they visit family in India, Sri Lanka or Nepal. Instead, they refer to yoga as an important religious heritage derived from Hinduism, and they might worship a particular guru and like parts of the Hindu tradition that are easily relocated to a new geographical and cultural context (for instance, Hindu dance, Hindu food and some Hindu festivals, such as Holi and not least Diwali, which can be associated with Christmas).

The same thing applies when they refer to parts of the Hindu philosophical tradition with the focus on self-realisation and the understanding of Brahman as

nirguna (“without qualities”) that can take many different

saguna (“with qualities”) forms. This is used to explain that Hinduism has no limits when it comes to representing an overall belief system as

sanatana dharma (“eternal law/religion/ethics”), which can be expressed everywhere and in new universalistic forms. Other people—especially among the first generation of Hindus in Denmark, but also young Hindus when they become parents—mention the importance of keeping up the Hindu traditions, but also their relationship with the land of their origin as a kind of shared reference that forms a kind of cultural or group identity. They also often point to the temple as a culture bearer. This is what Jan

Assmann (

2006) and Danièle

Hervieu-Legér (

2000, pp. 124–25) call cultural or collective memory. Both of these authors emphasise that memory is culturally transmitted, located not solely within the individual but stored in institutions or texts. In this respect, the temple or cultural associations and some of the institutionalised rituals appear to be given particular importance. This is also the case in Denmark, in line with what Vasudha

Narayanan (

1992), who studied Hindu immigrants from India to the US, calls “templeisation”, pointing to a shift of religious observance and ritual practice from the home to the temple.

As mentioned above, in many ways this is also what can be noticed in Denmark, but it is important to emphasise that the temple can also be understood as a cultural and social meeting place. For instance, my research in Denmark shows that the young generation of Hindus in particular regard temple activities not as “religious-religious”, but as “culturally or socially religious”. Here it becomes evident that they categorise what they understand as religion in a much narrower sense than their parents, but they also challenge the understanding of Hinduism as orthopraxis or identificatory habitus (

Michaels 2004, pp. 5–12). What is obvious in an Indian context, where habitus (“what you actually do”) in daily practice is closely intertwined with dharma (“what you should do”), is challenged in a Danish context. An outcome of this is that identificatory habitus becomes subject to negotiation in the Danish context, and has to be adjusted to suit a country where there is very little religion in the public sphere. This does not mean that the strong signifiers of being a good Hindu have disappeared. Instead, they have been rationalised, compartmentalised and more individualised or universalised. They have also been concentrated or condensed and are therefore much stronger in their expression on special occasions. This is in line with Yves Lambert’s understanding of religion in modernity, where religion is not disappearing but is given new forms in the light of a secularised society (

Lambert 1999).

In other words, although the temple is a shared point of reference, people perceive its significance in different ways (see also

Wilke 2020).

As seen in the examples above, it is difficult to cluster Hindus in Denmark into a single group. The picture becomes no less diverse when we take into account not only the approximately 25,000 people of Hindu descent in Denmark, but also other groups or individuals who (from a polythetic point of view) have various characteristics which are important, but not essential to all forms of Hinduism;

2 for instance, certain yoga and guru groups. There are also many people of Danish descent who are inspired by ideas that are rooted historically in Hinduism, or in religions with an Indian origin (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism or Sikhism) more generally. For instance, the level of belief in reincarnation has risen sharply in recent years

3, and yoga in its many variations has become part of everyday practice for many Danes. The same can be said about the use of karma as an everyday phrase in the Danish language (

Fibiger 2020a). Consequently, and as a heuristic framework for studying Hinduism in Denmark and other places outside of India, I suggest four categories or types, three of which can be related to groups of people or individuals, and a fourth, I will call a tendency, rather than a category, as it is a floating—though rooted—signifier and never fixed. The first three categories are: (a)

Hindu by descent, being people who understand themselves as Hindus by birth and by descent; (b)

Hindu-related, being movements or groups of people that associate themselves explicitly with the Hindu or Vedic religions. (c)

Hindu-inspired, being associations or individuals who, from a polythetic analytical outsider point of view, are inspired by the Vedic or Hindu traditions without themselves reflecting much on the fact that this is where the inspiration comes from. This also means that in most cases they interpret or translate the ideas to a worldview they know.

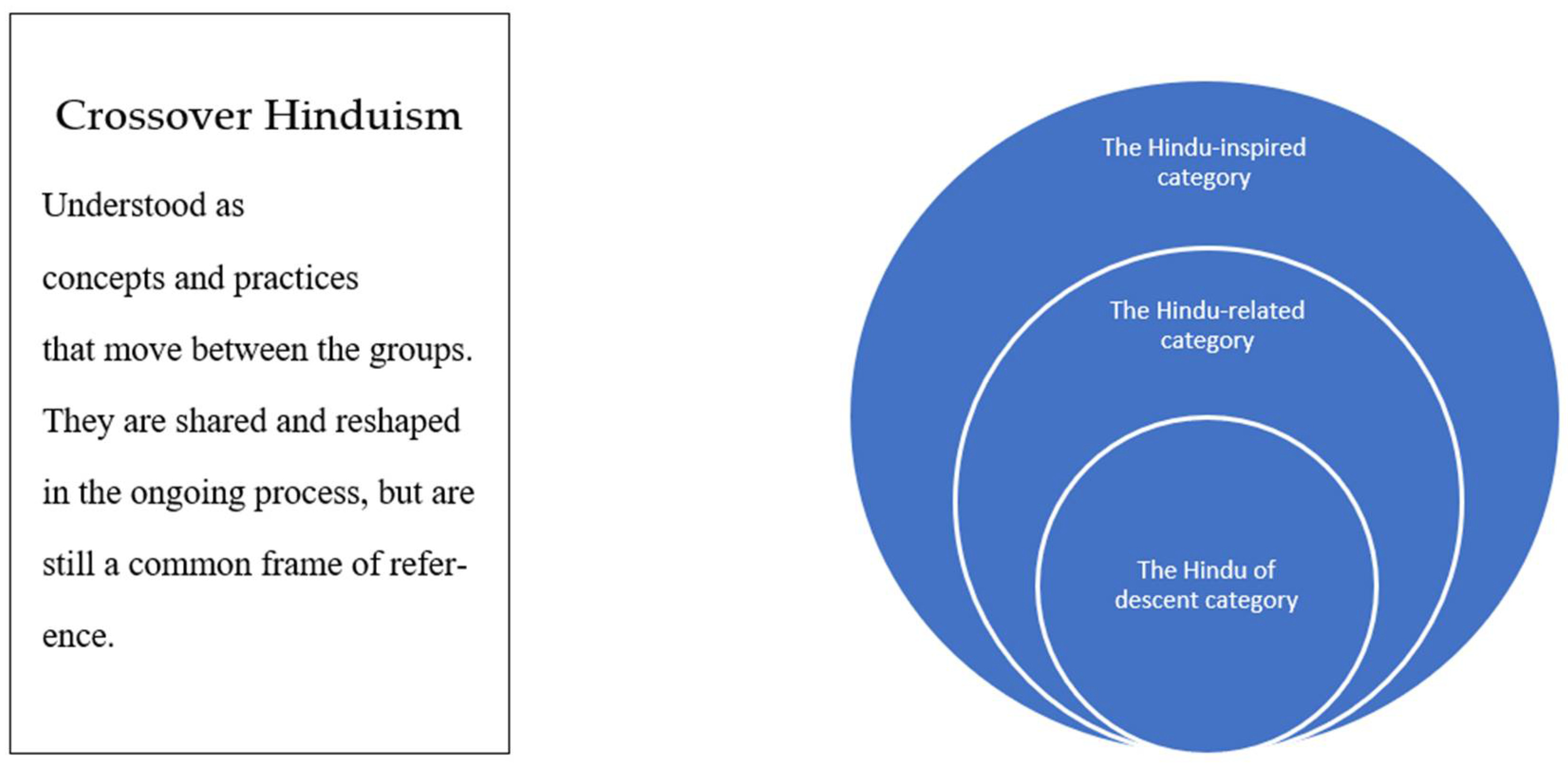

The fourth category or tendency I call: (d) Crossover Hinduism. This tendency can be understood as a kind of dialectical connecting network or meeting place between the three first categories. What is especially important in using this concept is that it emphasises that something is shared within all the three categories. This not only shows that parts of the Hindu tradition are widely shared, but also that concepts and practices can be interpreted differently. However because the interpretation and understanding of these concepts are continuously crossing borders between the different groups but also individuals, they will also continuously change some of their meanings in an ongoing process. In this process, the concepts can be extended or narrowed down depending on circumstances, but still within some kind of common frame of reference. I will give some examples of these crossover phenomena in the three groups outlined above as a, b and c. My hope is that these three categories or groups, supplemented with the suggested fourth, more blurred tendency, can be used as a heuristic framework for mapping, counting and discussing Hinduism in Europe.

My suggested group-categories are illustrated below. It is important to note that the figure should be understood in relation to identity or identification with the Hindu tradition from the strongest level in the smallest circle, to a weaker level in the periphery. This does not necessarily mean that people of Hindu descent practise Hinduism more than the other groups, but that they are much more aware of, or more explicit about, their sense of belonging to the Hindu tradition.

As stated above, the suggested categories shall only be understood as an overall heuristic framework. Within each group there are many subcategories, that again can be divided into even further sub-subcategories, and so on, depending on how fine-meshed an analysis one chooses to undertake. As an example, if we look at the overall category that is called Hindu by descent, further differentiation could be made between: (a) Hindus of either Indian, Sri Lankan and Nepalese descent. The differences between these groups can be observed religiously, culturally and also socially in Denmark. Religiously and culturally, it becomes obvious in that they do not share the same temples, they do not celebrate all the same festivals, they eat different forms of food, they have different understandings of caste and gender, and they do not share the same migration history. (b) Within these subcategories, further differentiations can be made between how they link to different localities in India or Sri Lanka and Nepal, to different local languages, and to caste and gender. (c) These sub-subcategories can be differentiated again in even new sub-sub-sub categories depending on gender, age, educational background, etcetera. This way of fine meshing can of course be done down to the individual level. Based on other parameters, the same fine-meshed analysis can be conducted within the other two suggested overall categories as well.

The main argument in this article is that despite the differences both between the categories and within the groups in the categories at an individual level, there are various kinds of shared references to certain concepts and practices, which is the reason for clustering them together. This is what I call Crossover Hinduism.

2. Crossover Hinduism

“Floating Hindu Tropes in European Culture and Languages” is the title of an article I wrote for Handbook of Hinduism in Europe in 2020, edited by Jacobsen and Sardella. In that article, I explored how some Hindu concepts, such as karma, Hindu practices, such as yoga, and the use of Ayurvedic medicine have become an integral part of European societies: from alternative lifestyles and therapies to healthcare and public institutions such as schools, kindergartens and prisons, and from new religions to mainstream cultures such as the advertising industry and everyday speech. Hindu-associated concepts and practices have extended their impact to many different spheres. They have become floating tropes and are embedded in both religious and secular spheres. As a result, they carry different meanings about the same practice or concept. The consequence is that they can be both a strong religious and spiritual signifier as well as being a secular signifier. They are lifted from their historical, religious roots, changing to adapt to contemporary time in European cultures and social contexts.

This does not mean that it is impossible to find some kind of common polythetic grounding, but it does emphasise the elasticity of these tropes. Whereas a religious meaning may be in focus in one context, it may be on the periphery or even absent in another. It is important to emphasise that the outcome is not that such floating signifiers do not have any anchors or roots. Instead, it can be concluded that the meaning given to a practice or a concept involves ongoing change or interpretations.

To explain why these particular tropes have become popular in Europe, I put forward two arguments in the article: firstly, I assume their popularity can be attributed to the fact that they can express or perform something that Western terms or Western-grounded practices cannot do in the same way. And secondly, they can be understood and practised in many different ways (semantic and practical elasticity) without losing their significance (semantic depth) (

Fibiger 2020a, pp. 764–66).

Many of the same characteristics apply to

Crossover Hinduism, a category or tendency that includes the above-mentioned tropes but also broadens the perspective in one respect while narrowing it down in another. For instance, I regard the dialectical tension between cultural appropriation (

Schneider 2003) and reappropriation (

Borup and Fibiger 2017) or the search for authenticity as especially important when it comes to Crossover Hinduism. What is involved here is eclecticism or syncretism not in a narrow sense, but in a wide and dialectical sense with both authenticity and adaptability being at stake in a mutual co-relation which can be called entanglement (

Ingold 2008). This corresponds to what Walter Benjamin labels a “dialectical image” in which both mirroring and mimesis are involved (

Urban 2003, p. 3;

Fibiger 2015). When religions, cultures and semantics meet, the result is often an amalgamation which may be more or less intentional, and which may include many different elements on different levels—from the exchange and fusion of different metaphysical ideas, worldviews and life views, to practices and ritual conduct. This underlines that syncretism in its widest sense is not a homogenetic and essentialistic phenomenon, but a dynamic and heterogenetic one, with changes and adaptations being more the general rule than the exception. This is not least the case when religion is analysed on a global, national and local scale; but it also applies when the focus is on the collective and/or individual level, between groups and minds—although some practitioners or bearers of a given tradition regard it as immutable.

This is also the case when it comes to Crossover Hinduism (see

Figure 1); but what I see as particularly important about this category or tendency is that concepts or worldviews are shared and defined as being important, but understood in different ways.

These different understandings also cross over the borders between the three proposed categories of groups in a constant flow. This means that the new understanding(s) or interpretation(s) of one concept in one group, for instance, the way karma is understood as “feel-good karma” (

Fibiger 2017a) in the group I call Hindu-inspired, can influence or extend the previous understanding of the same concept in the group comprising people of Hindu descent. On the other hand, these crossovers can also lead to stronger self-awareness of, and reflections on, the most important hallmarks within a given tradition—for instance, yoga. This is what I find especially among young second- or third-generation Danes of Hindu descent, who on the one hand like karma as a positive here-and-now “feel good” emotion, and on the other hand want to root yoga to the Hindu tradition, and disapprove of yoga being solely gymnastic and nothing else. As expressed to me by a young Hindu woman 22 years of age of Indian descent:

Sometimes I feel caught in between my Danish friend’s veneration for yoga and my strive for understanding the yoga-tradition as an old Hindu philosophy and practice. Yoga is not only gymnastic in the fitness centres. (Interview conducted in January 2018).

What I find especially interesting in this ongoing exchange is this tension or dialectic between (a) openness in which almost any understanding is acceptable, as long as it gives meaning, and (b) the search for authenticity. This tension can be traced in all the three groups, but in different ways or with different intensity.

I will now provide a few examples of this tension within all the three groups. I will focus primarily on yoga as an example, because this might be the best example of a meeting place that is also a contested space in a search for authenticity, although only when yoga is not appropriated in some way into a system of meaning such as Christianity.

I decided not to include Hindu crossovers to other religions, where the rooting is totally cut. I could have done so, and I invite other researchers to do this because the same patterns of entanglement and ongoing changes can also be observed in this crossover to other religions. What differs in this form of entanglement is that because the concepts or practices are appropriated intentionally into a special system of meaning, they are translated or adapted accordingly. So, from the perspective of this article, they do not constitute a Crossover Hindu phenomenon. Of course, we can find groups that are both. This is for instance the case with Christian yoga or cross yoga.

4 The group is openly inspired by the Hindu tradition, but at the same time the group reject the connection by reinterpreting the understanding of Karma yoga so that it fits into a Christian context.

The homepage for Christian yoga (

christianyoga.org, accessed on 15 June 2021) contains three long paragraphs on the three forms of yoga that are said to be presented in the Bhagavadgītā: Jñāna yoga, Bhakti yoga and Karma yoga. In the paragraph on Karma yoga, Jesus is regarded as a prototypical Karma Yogi. For this group, a prototypical Christian Karma Yogi is a person who does unselfish and altruistic deeds, for instance voluntary social work. However, the website emphasises that a Christian Karma Yogi differs from the ordinary Indian Karma Yogi. Traditional yoga practitioners generally try to turn their actions inwards, while Christian Karma Yogis turn them outwards, as explained on the homepage. On the one hand, the group is obviously inspired by the Hindu tradition, while on the other, they explicitly refrain from the Hindu rooting. Depending on point of view (insider–outsider), we can regard the group as Hindu-inspired, but as evidenced by the act of appropriation, the group do not regard themselves as such.

3. The Hindu-Inspired Group

In this category, I include all forms of Hindu-inspired practices and worldviews. I include Ayurvedic-inspired medicine and healing, karma as a strong trope, the idea of reincarnation as an explanation of the afterlife, the use of mantras, the reading of books written by or about Hindu gurus as an inspiration for new ways of living, trips on retreat to Hindu ashrams, yoga trips, etcetera. Many of these groups are more thoroughly described and analysed in

Handbook of Hinduism in Europe vol. I (

Jacobsen and Sardella 2020), for instance in the chapters that are written by Strube on New Age Religion, (

Strube 2020), Broo on Hindu Gurus (

Broo 2020), Newcombe on yoga (

Newcombe 2020), Warrier on Ayurveda (

Warrier 2020) and Fibiger on floating Hindu tropes such as karma (

Fibiger 2020a).

With regard to Hindu-inspired groups in particular, I find it important to have an ongoing discussion on how much a particular group can be said to be Hindu-inspired before it can be included in the category I call Hindu-related, and vice versa. The same can be discussed, when a person is linked to a religion by birth and uses this religion primarily for cultural or social purposes, and at the same time is inspired by the Vedic or Hindu tradition in the widest sense when it comes to belief or practices. As an example, I can refer to a middle-aged woman of Danish descent who expressed her relation to religion as the following:

I am a member of the Danish National Church, but I have added my own little bit of spice. Among other things. I believe in reincarnation, I like what Sai Baba says, and I practice yoga and have my own private Sanskrit mantra, which I once received from a guru and use when I do a little morning meditation.

(Woman, 45 years old)

The same discussion can in many ways also be relevant when it comes to young people of Hindu descent, who only feel linked to the Hindu tradition for cultural or social reasons. The difference between them and the woman quoted above are that the young people of Hindu descent still feel linked to dharma, both when it comes to certain behaviour patterns and in relation to caste and gender. In my interviews with young people of Hindu descent living in Denmark, this becomes especially obvious when it comes discussions of marriage, gender and how to raise a child (

Fibiger 2016).

I find the development of yoga in Denmark or Europe in general especially interesting when discussing Hindu crossovers, but also in the discussion of where to draw a line between the categories I call Hindu-inspired and Hindu-related. This could include other religions who have made the yoga practice “theirs”, as the example of Cross-yoga showed, but also when it comes to the Danish National Church, where yoga has become a common practice. As pointed out by Newcombe, yoga is both an idea and a spectrum of related practices (

Newcombe 2020, p. 555), and is expressed today in many different forms. It can be found both as a secular training programme and as a spiritual, religious and philosophical system. A search on Google for “yoga” yields approximately 1,320,000,000 hits. This shows not only that yoga is popular, but also that it can emerge in many, many different contexts with multiple meanings.

I have followed the development of yoga groups in Denmark, and have noticed that from an overall perspective within the last few years, yoga has followed three lines of development that are in many ways contradictory. One is the secular line, in which yoga is connected to almost everything from wine and beer to paddle boards. You can even find yoga for dogs. Some fitness centres call yoga jo:ga to express the idea that their form of yoga has nothing to do with religion or spirituality.

The second line is where yoga is appropriated so that it suits a new system of meaning, such as the Christian. Here, practice and its philosophical or religious rooting are disconnected.

The third line is a search for authenticity or reappropriation, in which some Hindus by descent, yoga groups or yoga instructors want to connect or reconnect their form of yoga to at least some of its presumed roots. This is where a discussion of whether a certain yoga group is inspired by or related to Hinduism becomes important. This can be seen in the following quotation, which is an invitation for a course given to yoga instructors from a former student of mine. She has made a business offering courses for yoga instructors, or interested yoga practitioners, who want to know more about the background of yoga:

Do you also sometimes get confused about the Sanskrit vocabulary used in your yoga practice or teaching, and would you like to learn about some of the most central concepts like samādhi, dhyāna, mokṣa, aṣṭāṅgayoga and the sounds of the alphabet and the pronunciation of various asanas and mantras? This workshop is designed for anyone wanting to increase their knowledge of the use of Sanskrit in yoga!

4. The Hindu-Related Group

In this group I include the so-called new religions that are not only inspired by Hinduism, but either have many Hindu practices they try to follow according to the Hindu tradition, or have a Hindu guru as their pivot. Here are some of the most influential Hindu gurus who have had (and still have) an impact on the Hindu or Hindu-inspired landscape in contemporary Denmark and many other places in Europe: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1917–2008), the founder of transcendental meditation; Abhay Charanaravinda Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (1896–1977), the founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), commonly known as the “Hare Krishna Movement”; and Paramahansa Yogananda (1893–1952), who introduced his teachings of meditation and Kriya Yoga to many Europeans in his book “Autobiography of a Yogi”, as well as founding various organisations such as the Ananda Group and the Self-Realization Fellowship—which still function today in many European countries. These groups differ in terms of whether they understand themselves as Vedic or Hindu, but in the perspective of this article I will not differentiate between the ways the groups associate to the Hindu tradition, or consider this differentiation in any greater detail.

One of the most influential living Hindu gurus in Europe might be Shri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi (b. 1953), also known as Hugging Amma or just Amma (“Mother” in Tamil). She is a contemporary, transnational guru who travels around the world to offer healing or loving embrace to all, regardless of religious or non-religious affiliation. At the same time, the devotional patterns closely follow the Hindu devotional bhakti tradition, and Amma herself is inscribed in a goddess śākta theology. This dual constraint of being linked to the Hindu bhakti devotional tradition (authenticity), as well as to a universal spirituality that transcends all limits of religion (universality), is typical of the above-mentioned Hindu-related groups (

Fibiger 2017b).

Thousands of people of European descent and Indian descent gather together when she visits European capitals such as Berlin, Barcelona, London and Copenhagen to give darshans. While many of the devotees of European descent have found what they understand as an alternative and meaningful religious or spiritual community they can relate to, many people of Indian Hindu descent find that she represents a form of Hinduism that suits their new way of living in a European society. In other words, with her as the pivot, they reconnect to a tradition from which they feel they have been disconnected.

This is an example of how this form of Crossover Hinduism, representing both universality and authenticity in a unique way, becomes a common meeting point for all devotees no matter what their descent, or how much or in what way they link to the Hindu tradition.

In some respects, this dialectic is also at play when focusing only on the group of Hindu descent, although in a slightly different way. Here the tension or negotiation between universality and authenticity becomes most evident between generations, but also between Hindus of Indian, Sri Lankan and Nepalese descent. Here questions about being the authentic bearer of the Hindu tradition is in play, as is the discussion of the right way of practicing in the temple.

Because the focus in this article is on Crossover Hinduism, I only refer briefly to the tensions between people of Hindu descent. For further details on this topic, please see my article called “Hinduism in Denmark” (

Fibiger 2020b), published in Jacobsen and Sardella (eds.), Handbook of Hinduism in Europe 2020 (

Jacobsen and Sardella 2020).

5. People of Hindu Descent

The group I categorise as being of Hindu descent, despite many internal differences, are the approximately 25,000 people who were born Hindu and who describe themselves as Hindus when asked about their religious or cultural affiliation. The group comprises primarily people from Indian, Sri Lankan or Nepalese backgrounds. This number has increased within the last few years, from 20,000 in 2018 to at least 25,000 today. The increase is primarily due to the large number of Hindus from India who come to Denmark to work for a certain period of time, but who may not settle permanently in Denmark. Most people of Hindu descent currently living in Denmark are Hindus of Indian descent (11–12,000 out of 15,135 people from India), followed by Hindus of Sri Lankan descent (around 10,000 out of 12,136 from Sri Lanka). A small number of Hindus in Denmark are of Nepalese descent (about 4000 out of 4899)

5. I will not discuss these figures or the differences between the groups in any greater detail, but will refer instead to (

Fibiger 2020b). What I find of particular interest with regard to Crossover Hinduism is the relationship between generations (first and second, but now also a third generation). While the first generation of Hindus in many ways want to maintain the traditions they know from India, Sri Lanka and Nepal, the second and third generations want to link to these traditions in a negotiated way (

Fibiger 2016). They want to combine their ambition to be a modern, young person in Denmark with their relationship to the Hindu tradition, which they still perceive as an important part of their identity, not least because it links them to a shared background with their parents. Here it becomes clear that the crossover forms of Hinduism that are given particularly positive connotations in the Hindu-inspired and the Hindu-related groups are taken more strongly into consideration as important parts of their Hindu identity. In this connection, yoga is given particular importance, although not in an unreflected or appropriated Danish way as mentioned above. In some ways they become more aware of its presumed Vedic and Hindu roots; in other ways they are happy that their tradition can provide Danes with something they appreciate.

Further, while most of the first generation of Hindus in Denmark seek authenticity by keeping up the rituals they know from their local roots in India, Sri Lanka or Nepal, the second and third generations seek authenticity in many of the crossover concepts or practices that appeal to groups other than people of Hindu descent, and besides understanding karma also as feel-good karma, they take part in some of the Hindu festivals mentioned in the introduction to this article.

As already mentioned, not all Hindus by descent are alike. I find many differences between the groups within this category; for instance, between Hindus of Indian, Sri Lankan or Nepalese descent, but also when it comes to Indian Hindus of Gujarati, Maharashtrian or Punjabi descent, who have organised themselves in particular cultural groups in Denmark. What they share is the need for finding a new “Hindu identity” in a Danish context. That is what Floya

Anthias (

2001) calls “translocal positionality” referring to the way “identities” are located outside old ethnicities and localities. Here I presume that Crossover Hinduism will play a role in balancing old concepts with a new setting.