1. Introduction

Educating interiority is an intrinsic part of educating a child for life and helping to develop the faculties that allow them to have a meaningful experience of life (

Alonso 2014;

Torralba 2015;

Otón 2018). It is an educational priority as a person without self-awareness is easily manipulated; that is why the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child incorporates the importance of providing a response to the spiritual needs of children and teenagers in four of its articles (17, 23, 27, and 32).

The concept of ‘spirituality’ used in this research project must be understood in relation to the meaning of life (

Kvarfordt and Sheridan 2007;

Eaude 2009), to what it really can mean to be fully human (

Moss 2011) and, thus, as a transversal and broader space than simply a religious one. In this sense, the sociology of religion (

Casanova 2019) shows that Europe is progressing towards the deinstitutionalization of religion that makes private and subjective forms of religiosity emerge, which is what Luckmann qualifies as invisible religion (

Knoblauch 2003). Society does not recognize these new forms of religiosity as religion, but rather as spirituality. Spirituality is a universal dimension of human experience, a concept that includes various belief systems (

Zohar and Marshall 1994;

Watson 2006;

Crisp 2008). Spiritual development involves becoming less self-focused and learning to transcend individual interests (

Gilligan and Furness 2006;

Canda and Furman 2010;

Nye 2019).

A spiritual person is reflective about their interests and motives, is curious about the world, and looks at life as a whole in making decisions (

Martínez-Rivera et al. 2020). To provide a holistic approach to children’s services, spirituality must be taken into account (

Watson 2006).

Furthermore, as it is shown in

Ní Raghallaigh’s (

2011) research, the spiritual dimension is an important part of one’s worldview, and closely related to the direction in which each person builds their life based on the personal decisions they make. We cannot talk about spirituality without interiority (

Radford 2006) as the spiritual dimension is a consequence of a developed inner life. Human interiority is, thus, a set of elements making up a person that is not directly perceived by the senses but, as

Crisp (

2008) and

Adams (

2009) assert, are part of lived experience. It is in the inner world that knowledge and life experiences are managed. This inner dimension is an important source of help to overcome difficult situations in life (

Vanistendael 2003;

Jackson et al. 2010;

Basset 2011;

Ní Raghallaigh 2011).

The universe of interiority comprises thoughts, emotions, memories, motivation, desires, fantasies, joys, and moments of sadness (

Torralba 2015). The spiritual dimension of the person is fed by all of these to build up the meaning of life.

It is easy to see that the contemporary Western world is showing a greater and greater interest in the non-material needs of the person, in other words, in interiority and spirituality (

Crisp 2008;

Moss 2011;

Benavent 2014). Recent research relating to spirituality and social work also brings to light that in the last 20 years, there has been a noticeable increase in interest in this theme (

Furness and Gilligan 2010;

Canda and Furman 2010;

Seinfeld 2012;

Hodge 2017). The research also highlights the importance and interest of building up interiority and some of the benefits associated with this work, and for this reason, it would be highly beneficial for educational institutions to incorporate it into their projects. This has been confirmed by social work studies on interiority with children and teenagers (

Scott 2003;

Mercer 2006;

Kvarfordt and Sheridan 2007;

Ní Raghallaigh 2011;

Nye 2019).

A holistic approach to the person involves an anthropology that considers the inner or spiritual dimension as something that everyone has (

Watson 2006;

Crisp 2010;

Benavent 2014). Inside every child, there are spiritual desires for happiness, fullness, a sense of solidarity, and kindness that are waiting to be stimulated by some adult (

Basset 2011;

Torralba 2015), and it is very important to allow children to express their spiritual voice, to recognize it and to nurture it (

Adams 2009). It is in the field of interiority where the conditions are given for subjectivity, feelings, the ability to listen, and awareness. It is also the place of self-awareness, from where they can distance themselves from reality.

However, there is still a reluctance to use the concept of spirituality due to the religious connotations of the term (

Scott 2003;

Canda and Furman 2010). The insistence that is reflected in documents such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (

United Nations 1989) and the

Delors (

1996) Report has not always been explicitly put into practice in social and educational projects and has sometimes been regarded as being of lesser or minor importance.

Even when social workers show a positive attitude to including the need to develop interiority in social and educational practice (

Hodge 2015), they often admit that this question was not explored adequately during their training (

Kvarfordt and Sheridan 2007;

Limb and Hodge 2010;

George and Ellison 2015). We observed in this study that social workers do not feel comfortable incorporating practical elements into their work to build up interiority in children, although they value the role of the inner dimension in the development of a person.

For this reason, these workers have been given a voice in this study to explore these contradictions and the difficulties they face when addressing interiority in their work in social and educational centers that care for children and teenagers outside school hours.

Other studies show that various difficulties hinder the education of the inner dimension in childhood and adolescence. Firstly, although spiritual development is given official recognition in the school curriculum in some countries, this is not enough to guarantee full application in daily practice (

Adams 2009).

Secondly, another of the difficulties that recurrently appears in research is the lack of non-religious vocabulary to address these matters, because, nowadays, there are proposals for spirituality that are not unequivocally linked to religion (

Comte-Sponville 2006). Although many people indeed develop their spirituality within the framework of a religious community, a traditional idea of identifying spirituality with religion can lead to confusion and narrow-minded attitudes on the part of workers (

Hodge 2017). From this point of view, professionals must be sensitive to the religious culture of children and adolescents.

Thirdly, there are difficulties related to multiculturality, as the culture of children and teenagers can generate different inner needs, which are expressed in diverse ways (

Canda and Furman 2010;

Stern and Shillitoe 2019). Religious identity, which is a dynamic issue that changes thanks to the influence of cultural diversity, is still maintained, in some cases and especially among teenagers, despite living in a multicultural society. Education must encourage children and teenagers to explore what is important to them and for the culture in which they live (

Eaude 2019). Social workers must be sensitive to this to help them to negotiate and construct their identity (

Moulin-Stozek 2017).

Finally, workers have no suitable framework of comprehension to deal with themes related to interiority (

Mercer 2006). Those who work with children usually place little importance on the spiritual beliefs that they express. Many aspects related to inner life are difficult to narrow down and define (

Nye 2019).

Although several authors have reflected from a theoretical perspective on the needs of interiority in children and teenagers, there are few social and educational studies that assess the difficulties faced by workers when they tackle this interior dimension educationally.

The aims of this research were to:

Analyze the difficulties of social workers when dealing with interiority with children and teenagers on two levels: the factors that they believe can make building up interiority difficult and those that make their own practice difficult.

Identify the main strategies that social workers use to cope with these difficulties.

2. Materials and Methods

The current research used a concurrent mixed method design, with qualitative and quantitative data, from the Cuestionario de Interioridad para Profesionales de Adolescencia e Infancia (CIPAI) (Questionnaire on Interiority for Professionals Working with Teenagers and Children), on developing interiority. The questionnaire was completed by professionals working with children and teenagers.

The questionnaire CIPAI, apart from the initial sociodemographic data, consists of four blocks of questions, both open and closed or with a Likert scale: the first block asks about the specific experience with the group of children and adolescents with whom the professional works (16 questions), the second block inquiries into the institution where the professional works (10 questions), the third block is about the work carried out by professionals in the socio-educational center (11 questions) and, finally, a fourth block asks about the conceptual aspects and personal opinion of the professional (64 questions).

The study was carried out in a network of non-profit private social and educational centers that form part of the XACS (Network of Social and Educational Centers), around Barcelona (Spain). It is coordinated by Pere Tarrés Foundation, a Catholic institution with more than 60 years of experience in education and social services. It is relevant to highlight that these socio-educational centers work with an open and respectful look towards all forms of religiosity and spirituality.

This network comprises 23 social and educational centers serving 3770 children, with public and private funding. The social-educational centers form part of the Public Social Services established by Decree 142/2010, of 11 October, passed by the Parliament of Catalonia. The law describes them as ‘preventive day service outside school hours, which supports, encourages and promotes the structuring and development of personality, socialization, acquisition of basic learning and leisure, and compensates for social and educational deficiencies of children, working individually, in groups, with families and networking with the community’.

2.1. Participants

A total of 198 professionals working in 23 centers were invited to take part in the study, of whom 128 replied to the questionnaire, which represented a response ratio of 64.6%. All the participants were informed of the aims of the study and their permission was asked to complete it. Participation was completely voluntary. All subjects provided informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Pere Tarrés Faculty.

Of the 128 professionals who answered the questionnaire, 72% were women. The mean age was 30.3 years (SD 7.9). A total of 16.4% had no university education, 61.7% had a degree or equivalent, and 17.2% also had postgraduate education. The remaining 4.7% had a basic educational level. At the same time, they had an average of 5.2 years’ experience in volunteering (SD 5.1) and an average of 5.9 years of work experience (SD 5.8). A total of 93% were working directly with children. Concerning children and teenagers, Islam is present in 20 centers, and Catholicism in 14. Few children from other religions are present.

2.2. Data Collection

The CIPAI questionnaire was designed ad hoc in two phases: firstly, semi-structured, in-depth interviews were held with key informers in the centers (n = 7), and the dimensions highlighted as relevant in the theoretical review were assessed. In the second phase, the items in the questionnaire were developed from the theoretical analysis and the result of the interviews. Then, a validation process was performed by judges (workers and scholars in social education) (n = 10). The resulting questionnaire was provided in person to the workers from the different centers in the first semester of 2019.

This article presents the results given to the three specific questions from the CIPAI that refer to the limitations and difficulties of working on interiority with a group of children and teenagers.

The first two questions were closed multiple-choice questions. The first question dealt with what the worker believed may (potentially) hinder dealing with interiority and the second, what the worker admitted is currently difficult to work on in real practice. The possible response variables were basic training of professionals; building up a personal inner life; tools and methodological strategies; activities that have previously failed; the children’s interest; the interest of the team of workers; institutional interest; cohesion of the work team; cohesion of the group of children or teenagers; none. The third question was open and proposed that the workers explained any difficulty related to interiority that they have encountered in the group they were working with and how they solved it.

2.3. Data Analysis

On the one hand, quantitative analysis (of the first two questions) consisted of establishing relationships between the potential and the real difficulties. The IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Program was used in all cases. On the other hand, qualitative analysis (of the third question) was performed with the help of Atlas TI.8. From the content of the answers and with the help of the theoretical framework, easily recognizable categories and subcategories were established. Subsequently, the categories were ranked, and the content of the text was analyzed and interpreted.

3. Results: Difficulties Perceived by Professionals and Strategies Used to Deal with Them

The research results are presented, following the aims of the research. Firstly, the difficulties that professionals believe they have are compared with those that really hinder their practice and are presented based on quantitative and qualitative data. Secondly, the strategies of dealing with and solving these difficulties are presented using only qualitative data.

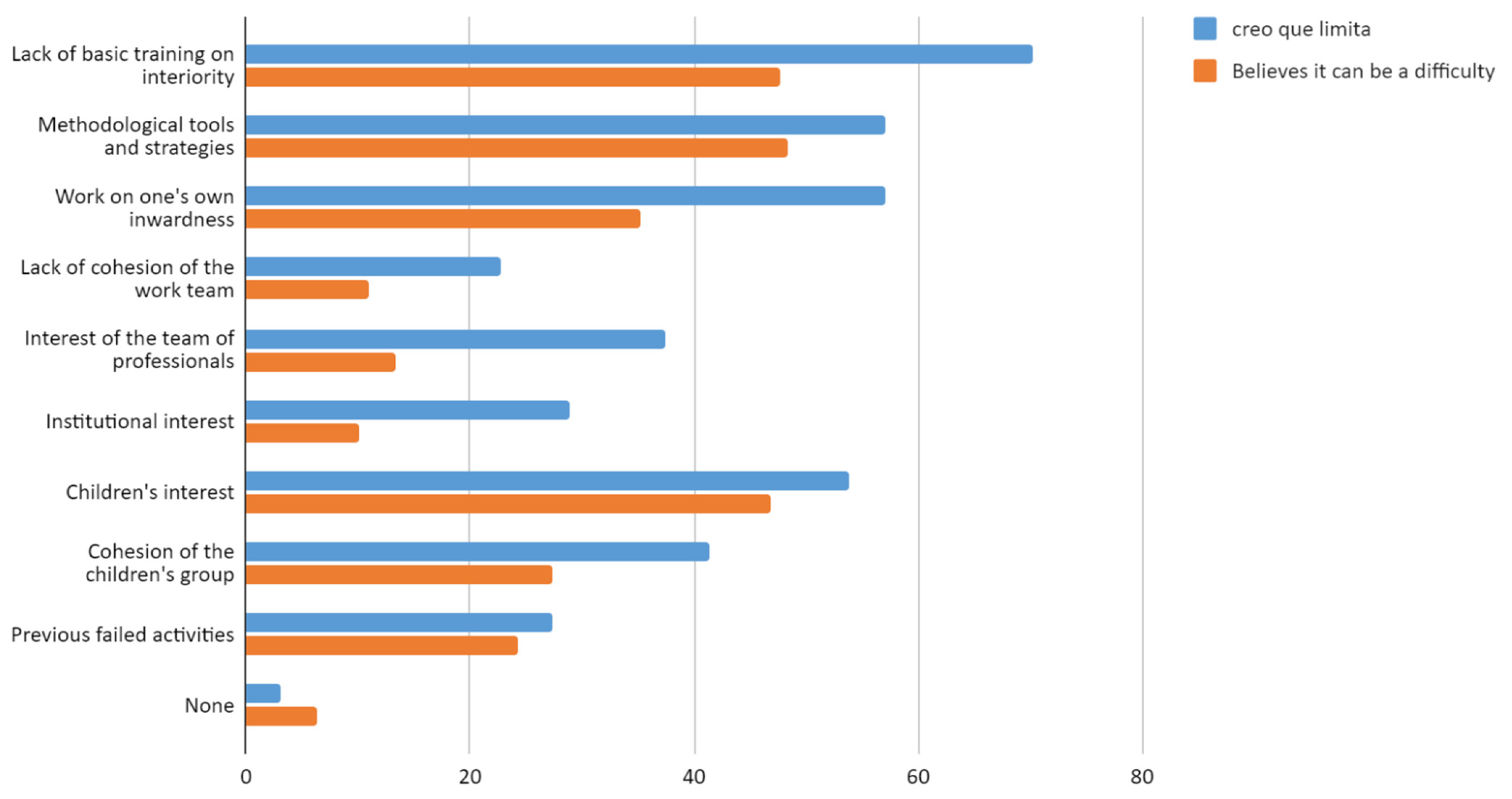

Figure 1 shows the comparative results between what is believed to be the difficulty and the items considered as a real difficulty in their job.

As can be seen in

Figure 1, the workers have greater beliefs regarding what can hinder work than what they admit really makes it difficult to perform this work for all the variables analyzed. Specifically, it is possible to highlight that workers’ basic training, building up a personal inner life, tools, and methodological strategies, as well as the children and teenagers’ interest in the subject, are the four aspects that workers find restrict them most. Of these, only three are recognized as a real difficulty in their professional context to help build up interiority. Developing a personal inner life is recognized as a real difficulty only by a third of the workers.

Below, we present the results obtained qualitatively, which show coincidence with two of the most highlighted quantitative aspects (Basic training on interiority and Cohesion of the work team). A further three relevant aspects seem to result from the mixed research model (Previous activities that have failed, The children’s interest, and Group cohesion of children).

3.1. Lack of Basic Training on Interiority

The lack of basic training on interiority is the most widely expressed restrictive belief (70.3%) and the most widely recognized difficulty (47.7%). Among the difficulties related to the lack of training, the professionals mentioned mainly the lack of a transversal approach, little coordination, or willingness on the part of the educational team, impediments to transmit or address interiority and, lack of space in most centers.

Regarding the lack of training, almost half of the professionals (48.4%) admit that they do not have tools or methodological strategies to work on interiority; however, working on one’s own interiority is seen as a limiting belief in 57% of the responses, but is admitted as a limitation in only 35.2%.

A total of 20 people explained difficulties related to organization and professional work, as exemplified as follows:

‘Lack of coordination with the work team, lack of training in the subject, narrow-minded attitudes of some workers, lack of transversal project in the center.’

(27:16)

Nine comments (7%) referring to the difficulties experienced trying to incorporate work on interiority into an educational project with a highly specific aim can also be highlighted. There is no space or time to do this work without forgetting the ‘main aim’, as this evidence specified:

‘I think that it is difficult to deal with interiority if there is a specific aim. For example, educational reinforcement: parents want their child to improve academically…not work on transcendental things.’

(8:17)

When workers detect difficulties in working on interiority, they develop actions related to emotional education and education in values, in which they feel competent. In these cases, aspects such as self-confidence, self-esteem, and peace are specifically dealt with.

When workers are asked about solutions to this difficulty, they put forward the need to be trained in spiritual intelligence, self-awareness, resilience, moral sensitivity, and the celebration of diversity. The meaning of life, the belief system, loss and grief, suffering, serenity, and self-analysis also come up.

3.2. Lack of Cohesion of the Work Team

Of the professionals who believed that the lack of team cohesion could be a difficulty (22.7%), only half considered it a real difficulty (10.9%). On the other hand, the belief that a lack of professional interest can be a difficulty (37.5%) reduces to 13.3% when it is considered a real difficulty. A similar decrease is observed when referring to the lack of institutional interest (from 28.9% to 10.2%). In all three cases, it can be observed that the actual perceived difficulties are significantly lower than the belief in them.

Difficulties related to the professional team appear in various comments:

‘If the activity is well structured, but no thought has gone into encouraging cohesion in the group, the activity may fail. Depending on the group of educators, if they are apathetic, this makes it almost impossible.’

(12:17)

‘It would be positive to introduce work on interiority as long as it is defined beforehand, the professional team internalizes it, and the institution prioritizes it and contributes resources.’

(13:11)

Concerning strategies related to change-generating interventions, most deal with organizational changes and professional work (38 comments). Some of them are connected to methodological strategies such as incorporating new techniques, bearing in mind the children and teenagers, and teamwork:

‘We have to begin little by little and with realistic expectations. First, we need a cohesive group of professionals before working on other things. This has been achieved using many group dynamics activities, placing value on the team, encouraging, and praising good behavior, and promoting cohesion…’

(79:18)

3.3. Children’s Interest

Another of the difficulties expressed by over half the participants (46.9%) is related to children and teenagers’ interests. When workers talk of lack of interest in children as the main difficulty, they highlight the resistance to build up the ability to analyze themselves:

‘Normally they are young people who find it hard to speak about emotional themes and self-analysis as they are quite secretive, and this area is hardly ever brought forward for discussion. They think it’s a waste of time.’

(96:17)

This resistance also includes secrecy or mental blockage, lack of interest or motivation, lack of awareness of the relationship with others or the scarce willingness to create emotional ties and relationships, lack of sense, among others, which are some of the spiritual competencies that cause certain difficulties or place obstacles to satisfactorily address interiority:

‘At times, when we have tried to work on some more personal and/or emotional aspect, some children have refused to take part and become a little nervous; it’s as if they wanted to avoid dealing with interiority, to express themselves…’

(73:17)

Lack of interest or motivation, lack of awareness of the relationship with others or the scarce willingness to create emotional ties and relationships, and lack of sense are the main spiritual competencies that cause certain difficulties or place obstacles to satisfactorily address interiority.

Difficulties also arise in the low sense of connection or desire for the transcendent world, and, to a greater extent, in restrictive beliefs and lack of self-awareness and self-knowledge. By far, the greatest difficulties related to interiority are linked to the lack of serenity and calmness:

‘When we try to keep calm in group spaces, it normally doesn’t work.’

(78:15)

In this sense, some difficulties in developing spiritual intelligence connected with self-awareness, moral feelings, resilience, and exploration are also seen. A lack of emotional competencies is specifically related to interiority, including low self-esteem, low self-confidence, and lack of serenity, and particularly, of social competencies and emotional self-regulation:

‘Difficulty in managing emotions, the mental block experienced by the person that translates into negation and indifference in the face of most stimuli.’

(29:17)

‘They didn’t accept praise. To admit and show feelings.’

(61:17)

Some difficulties reveal the absence of values and, particularly, of empathy, friendship, and companionship. The workers consider the need to incorporate interiority-based activities into teaching values and attitudes of respect and coexistence, the consolidation of critical thinking, and the application of dialogue as a tool for understanding. The absence of skills and strategies to take collective decisions, the low commitment to the group, and the refusal to take on responsibilities were regarded as obstacles. In connection to self-esteem and lack of self-confidence, the lack of value they place on their own criteria to make decisions, and the communicative difficulties and strategies, they must argue their point:

‘They want you to decide for them when they have to decide on something important.’

(52:17)

‘They find it hard to talk about personal things and those related to identity. They also find it hard to stop and observe how they are feeling.’

(16:17)

In our study, we found that difficulties related to freedom of conscience, respect for religious diversity, and lack of interreligious dialogue were regarded as being less important. Some difficulties are linked to religious dimension, associated with explicit situations of conflict, among others, such as gender differences (some people of Islamic religion do not want to do exercises with a person of the opposite sex) and the lack of group cohesion (not understanding the agnosticism of some versus the religious values of others).

Many workers refer to reactive responses that are not considered as a long-lasting solution in time (36 comments). Further, this kind of response does not deal with the causes or the truly restrictive elements. In fact, quite a few statements explicitly mention that the situation has not been solved (17 comments). Some professionals have decided to abandon the activity or restrain or temporarily separate the people who are perceived to be generating the difficulty:

‘First, when we detect something going on, a young person is invited to leave the space to breathe deeply. And then we talk to them to make them aware that they are not alone, and we are willing to listen if they need it.’

(57:18)

3.4. Cohesion of the Children’s Group

The most important set of comments refers to the cohesion of the group of children. The high number of children in a group, conflicts among group members, irregularity of attendance, and the lack of habit and of previous experience in building up interiority are some of the difficulties reported:

‘It was extremely complicated; the children constantly lost concentration and weren’t able to listen to their body.’

(38:16)

There are few explicit solutions to these difficulties. The most significant comment is the relevance that the reflection assembly and individual tutorial have:

‘Doing activities and using dynamic methods in the reflection room or group assembly to address topics worrying the group that they themselves have suggested. Offering a quiet space for calm and relaxation in the group’s own room.’

(38:17)

In connection with the aforesaid, 10 comments mention some difficulties related to the setting. Most of the comments refer to the difficulties caused by a restrictive perception, on the part of the families as well as children and teenagers, of the service offered by the center, which is exclusively linked to educational reinforcement. They also point out other difficulties such as the inherent diversity in the groups of children and teenagers and the complexity that their management implies—basic needs that are not covered and lack of knowledge of the language, for example:

‘There are basic needs that are not covered. In other words, food, housing, work. If these minimum requirements are not covered, the young people find that spirituality doesn’t give anything to them.’

(94:16)

On some occasions, dealing with interiority requires making changes in the environment. In these cases, workers deal with them through networking:

‘During the year, different services: school, open center, etc., are involved in intensive work to address these difficulties.’

(86:18)

3.5. Previously Failed Activities

Activities such as yoga, relaxation, and spaces and moments for silence have not always been a success before. This is perceived as a difficulty by 24% of the workers. They also refer to how hard it is to hold reflection meetings:

‘Last year we did relaxation workshops, but there was no way to make them get into the dynamics of the workshops. When one was quiet, another was playing around.’

(18:17)

Strategies used to deal with this difficulty comprise modifying elements such as finding individualized spaces, the reorganization of time to have greater availability, the ratio of workers, and the incorporation of the dimension of ‘fun’ (23 comments).

‘Working implicitly using play and games, because if it is explicit, they may reject it as sometimes they are not ready.’

(73:18)

Likewise, solutions that relate to addressing interiority from a transversal point of view are mentioned. Proposals are put forward to build up education in values; these imply working on dialogue as a social ability, as well as taking on responsibilities and behaving with a respectful attitude, consolidating as part of their personal culture, a culture of solidarity achieved critically, that is, understanding and assuming these values as their own.

‘Working on active listening and respect through activities and the dynamics of reflection, like assemblies or roleplaying, to put themselves in the other person’s shoes.’

(54:17)

Work on decision-making means making certain changes and requires developing a positive attitude to take part in and be willing to dialogue, as well as acquiring or improving communicative skills.

4. Discussion

With reference to the first aim, there are four aspects where greater difficulties can be found: workers’ basic training, building up a personal inner life, tools and methodological strategies, and the interest of the children and the teenagers themselves in the subject. In all of them, it is observed that the belief in difficulties is greater than the difficulties of professional practice.

When the workers specify the difficulties related to interest and to group cohesion among children, they mention the creation of moments of relaxation as a relevant difficulty. With reference to contents, most resistance is found in the ability to look inward, to create affective ties, and to the lack of serenity and calmness.

It has been detected that the very characteristics of the group of underaged people pose problems for workers to build up interiority, such as lack of willingness, lack of habit and previous experience in trying to work on interiority, and the basic needs to be covered.

Overall, workers do not identify any personal difficulties that contribute to building inwardness; rather, these difficulties are attributed to external factors such as the group of children, the project, and the environment. This contrasts with one of the most widely identified difficulties: the lack of basic training in interiority and spirituality. There is a broad consensus among authors (

Gilligan and Furness 2006;

Limb and Hodge 2010;

George and Ellison 2015) about the need for professionals to place more emphasis on exploring religious or spiritual beliefs during training, in professional practice, and in their own lives to become more sensitive to this issue.

On the other hand, results show that the workers associate educating interiority with work on emotions, and encounter difficulties related to low self-esteem, self-management of emotions, and lack of values. This, in part, reduces the concept of interiority to the field of emotions, excluding spiritual aspects relating to decision-making and meaning (

Zohar and Marshall 1994;

Otón 2018). These results highlight the difficulty of defining spirituality and interiority as stated in the literature review (

Adams 2009;

Hodge 2017). Even among workers that are sensitive to this theme, the difficulty of recognizing educational activities that work on spirituality or interiority can be observed. For this reason, it is advisable to conduct further in-depth studies on this matter.

Concerning the second aim, workers admit there are ways of dealing with the difficulties expressed on two levels: through structural changes and through social and educational intervention itself. On the first level, admitting that intervention is often reactive and involves restraining situations of difficulty, they propose spatial organization, as well as time and ratio changes. On the second level, however, there appear proposals related to the social and educational project, action plans, and activities. In this sense, dialogue skills, emotional education and education in values, and the ability to reflect are some of the strategies that are used to face these difficulties.

Certain difficulties revolve around the fact that children and teenagers have not had experiences of this kind. Based on the idea that interiority and spirituality are dimensions that are inherent in a person, whatever their situation, we suggest, following

Torralba (

2015), that work on these aspects can be performed at any moment of a person’s life cycle. In any case, it will be essential to bear in mind the changes that the concepts of religiosity and spirituality are experiencing in European society (

Knoblauch 2003).

It must be highlighted that simply intending to work on these dimensions does not produce sufficient results. Institutions need to plan and, consequently, put in place a schedule of activities in social and educational resources, which bear in mind the complexity with which interiority is expressed in a multicultural world, as highlighted by

Canda and Furman (

2010).

Reactive responses to conflicts and difficulties linked to interiority have generated dissatisfaction among workers. Despite centers being willing to work on interiority, difficulties are recognized when considering spaces and activities related to this task. The research shows evidence of the need for training in interiority to improve these interventions.

Although the need to work on the inner and spiritual dimension in children and teenagers has already been addressed by different researchers, in this case, the direct voice of workers in their social and educational intervention has been brought to the fore.

This research has been carried out in a series of centers with very similar characteristics, which has allowed for a highly homogenous observation. By trying to reach a widespread sample, it was not possible to access this sample through interviews, and that is why the open question was included in the questionnaire. The research suggests the possibility of exploring other centers with different characteristics and, at the same time, using a qualitative methodology for further in-depth study.

5. Conclusions

Thanks to this study, voice has been given to educational centers that have been able to express diverse restrictive beliefs to educate interiority in children. It is noted that these restrictive beliefs do not always coincide with the real difficulties encountered in professional practice. There are more restrictive beliefs to work on inwardness than real difficulties; therefore, the real barriers lie in the mentality of the professionals. The first difficulty to overcome is the limiting beliefs.

Workers admit that addressing interiority in children and teenagers is extremely important and essential, according to the characteristics of the comprehensive education of the socio-educational centers; however, they express real difficulties in integrating this dimension into their work in pedagogical practice.

Among the main difficulties brought up in this regard are those related to the group’s characteristics. The lack of willingness and resistance to work on self-analysis, the lack of values, and a deficit of emotional competencies are some of them. Nevertheless, other difficulties related to professional practice are also relevant: low level of basic training on interiority, building up a personal inner life and, the lack of tools and methodological strategies to address this topic.

In the analysis relating to the strategies that workers use to help build up interiority, reactive actions are mostly observable. These reactive responses do not satisfy workers as they are not long-lasting. There is a willingness to work on interiority, but training is needed to make improvements in these interventions.

This opens the possibility of replicating the study in different educational contexts, both at school and in the population that is not in a socially vulnerable situation, which would provide comparative information about the nature of the difficulties expressed by workers.