Hybridity in the Colonial Arts of South India, 16th–18th Centuries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

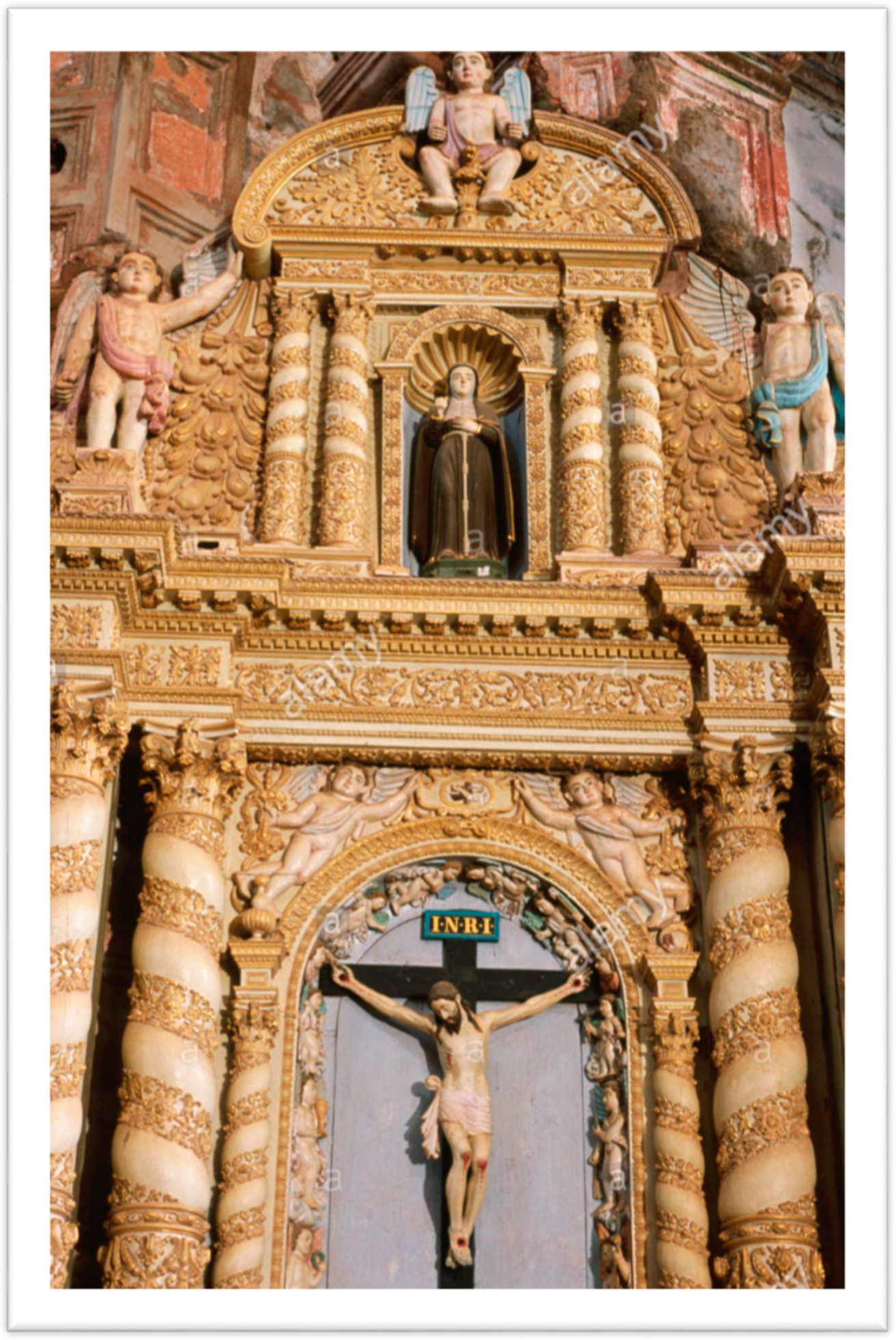

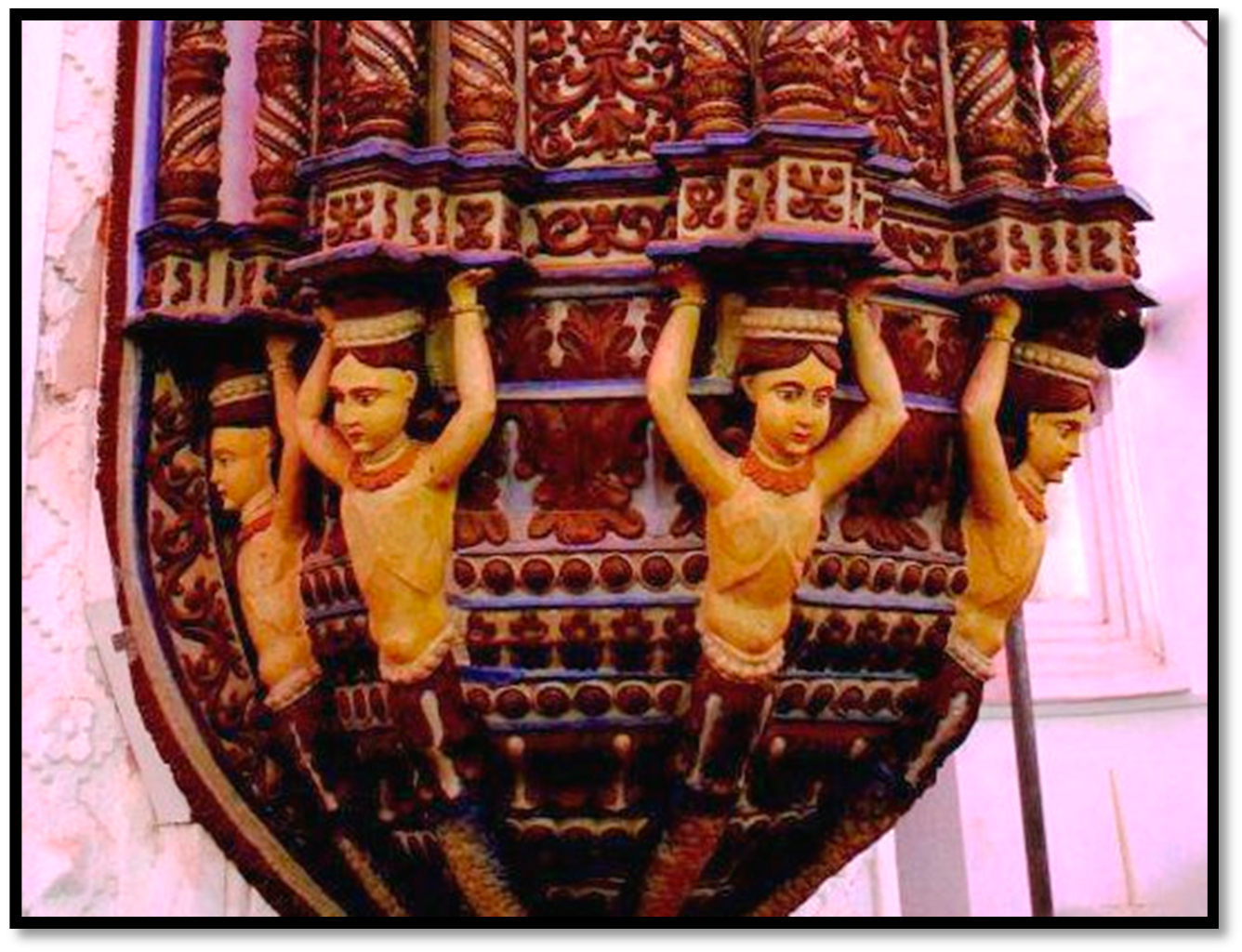

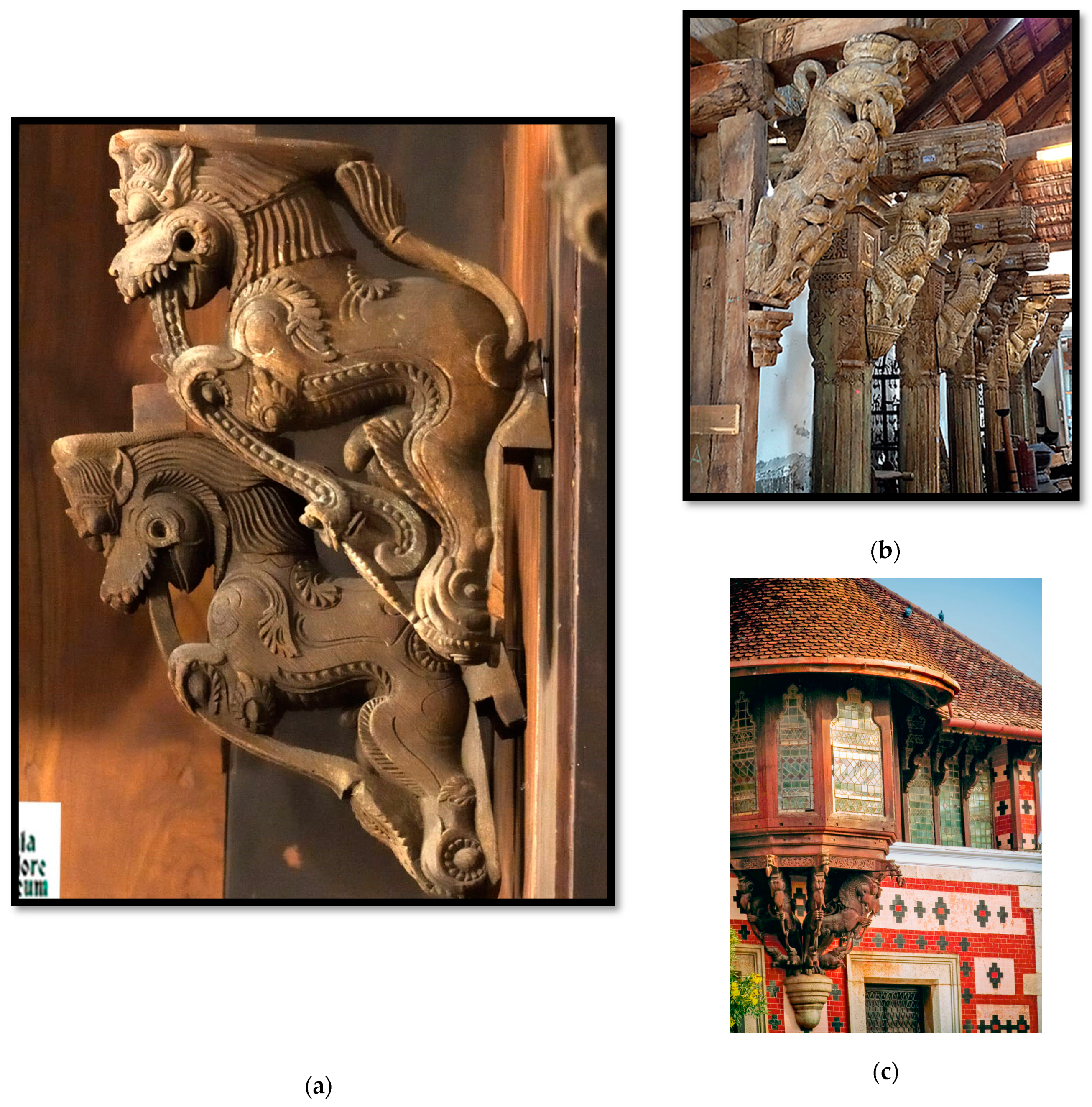

2. Polychrome Wooden Sculpture in Goan Churches

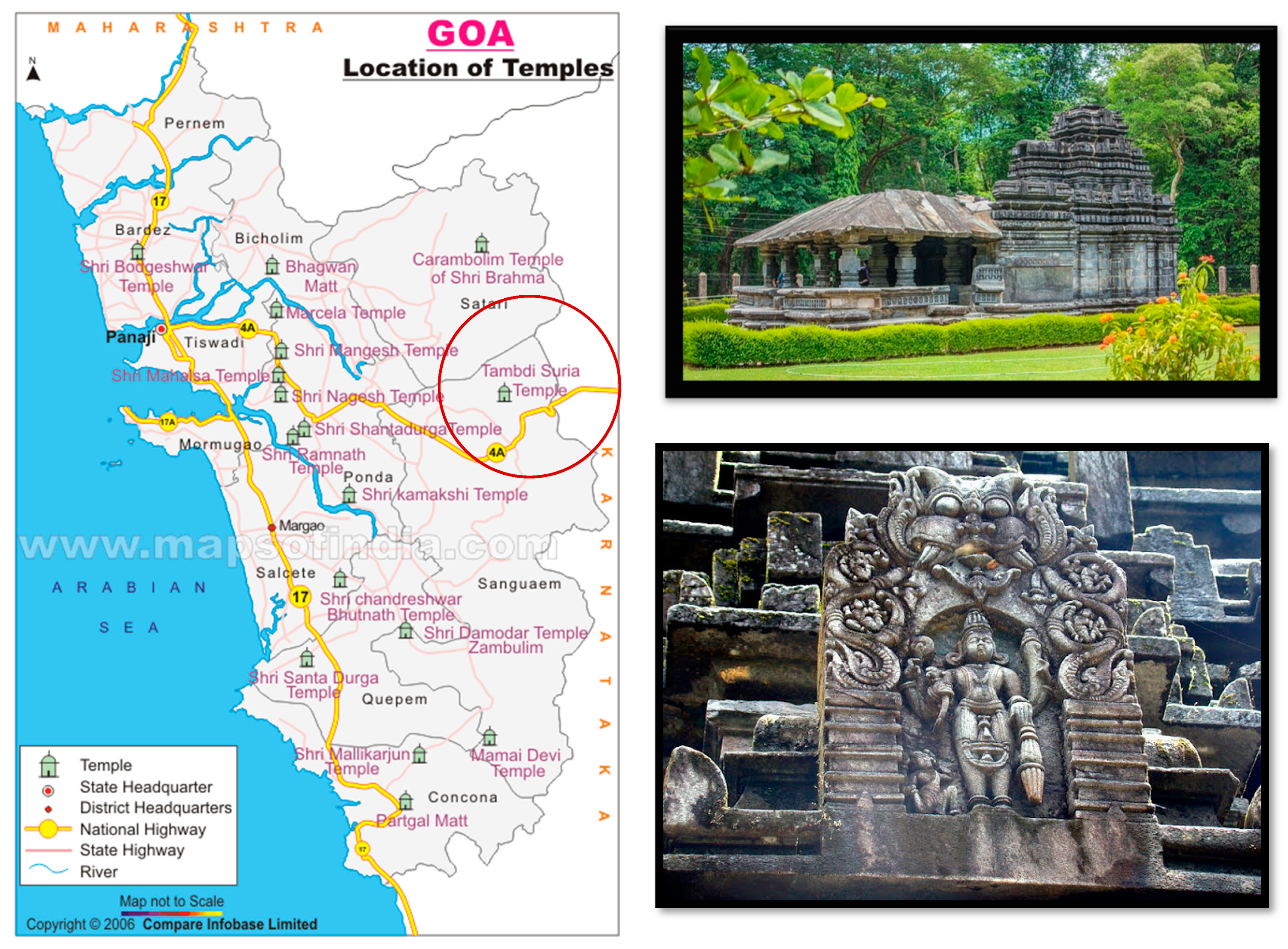

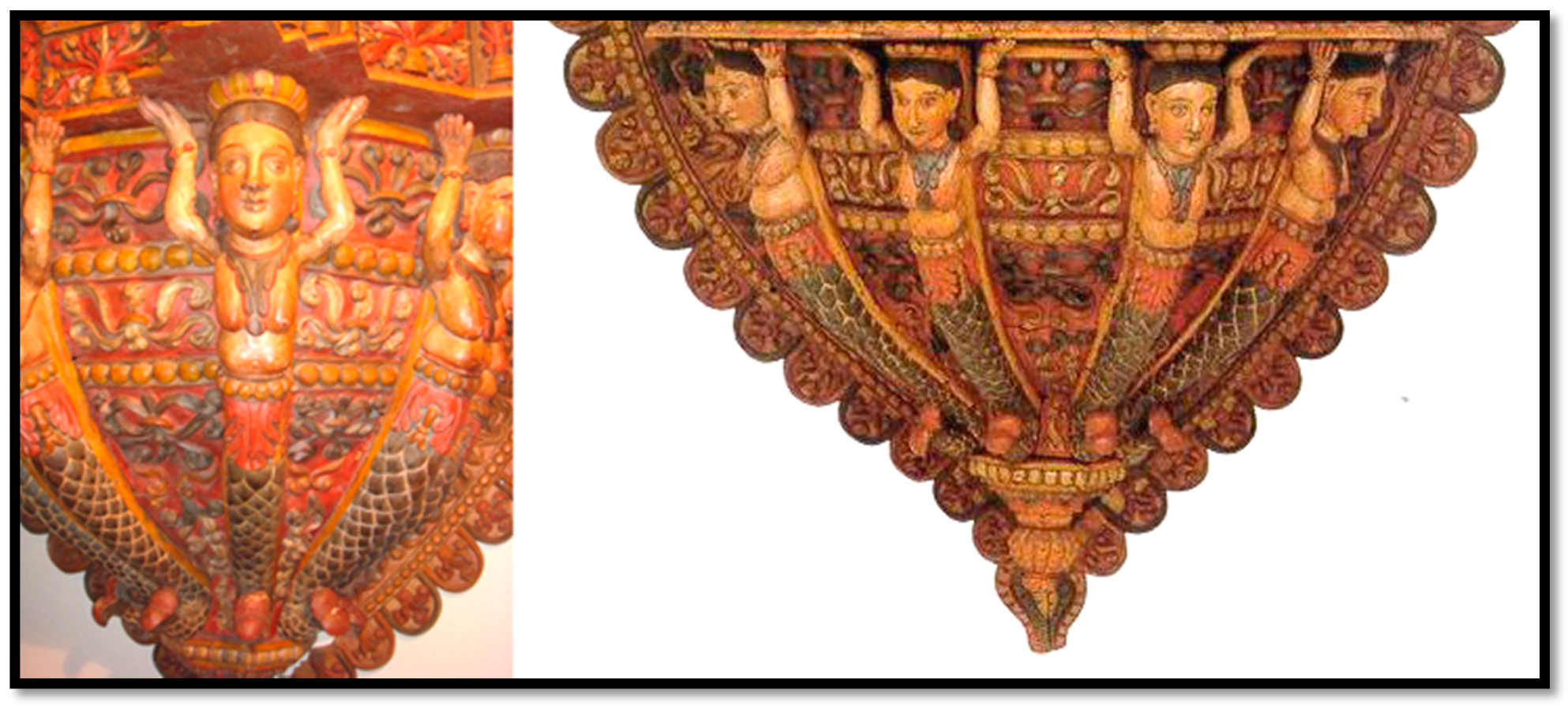

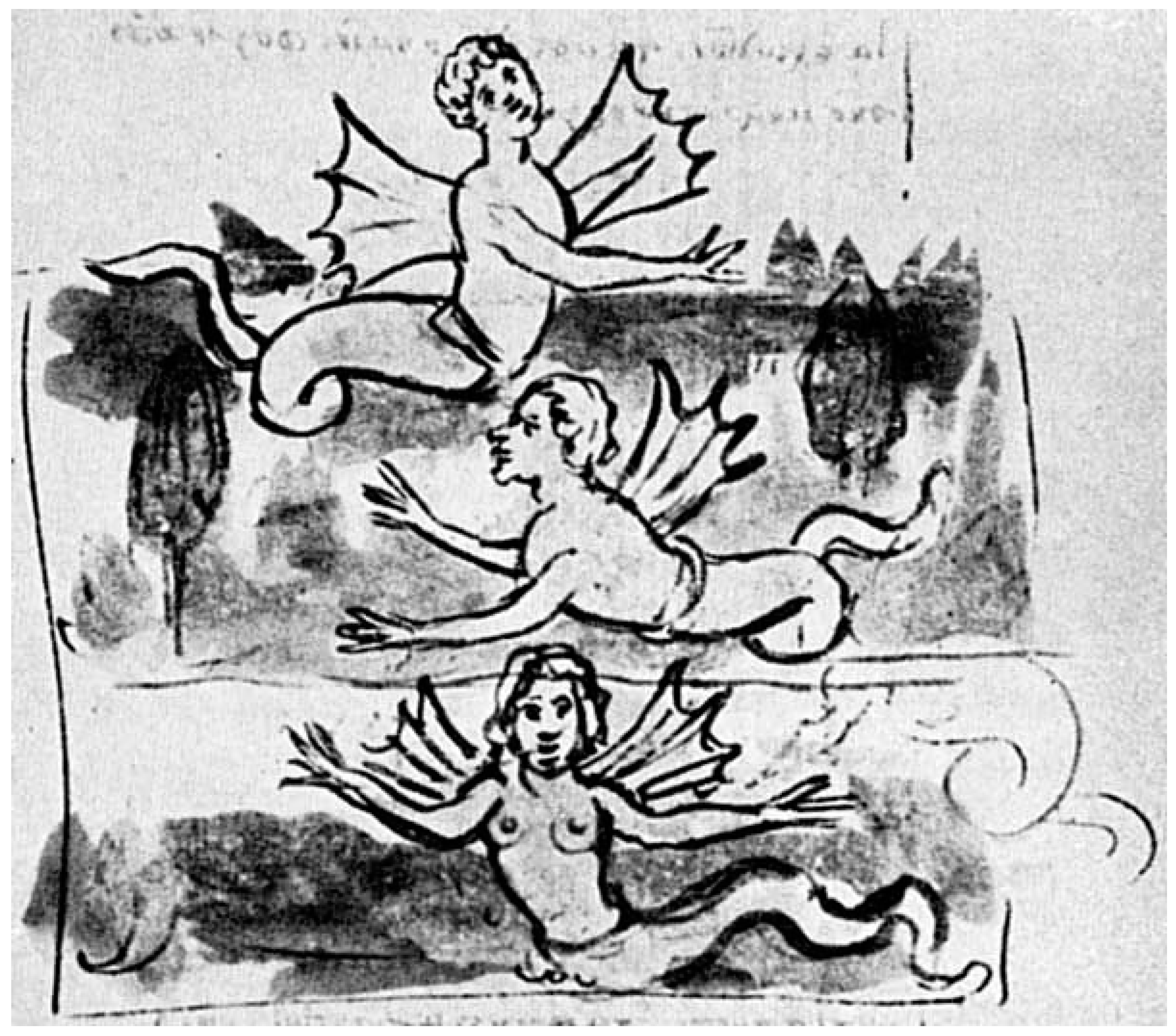

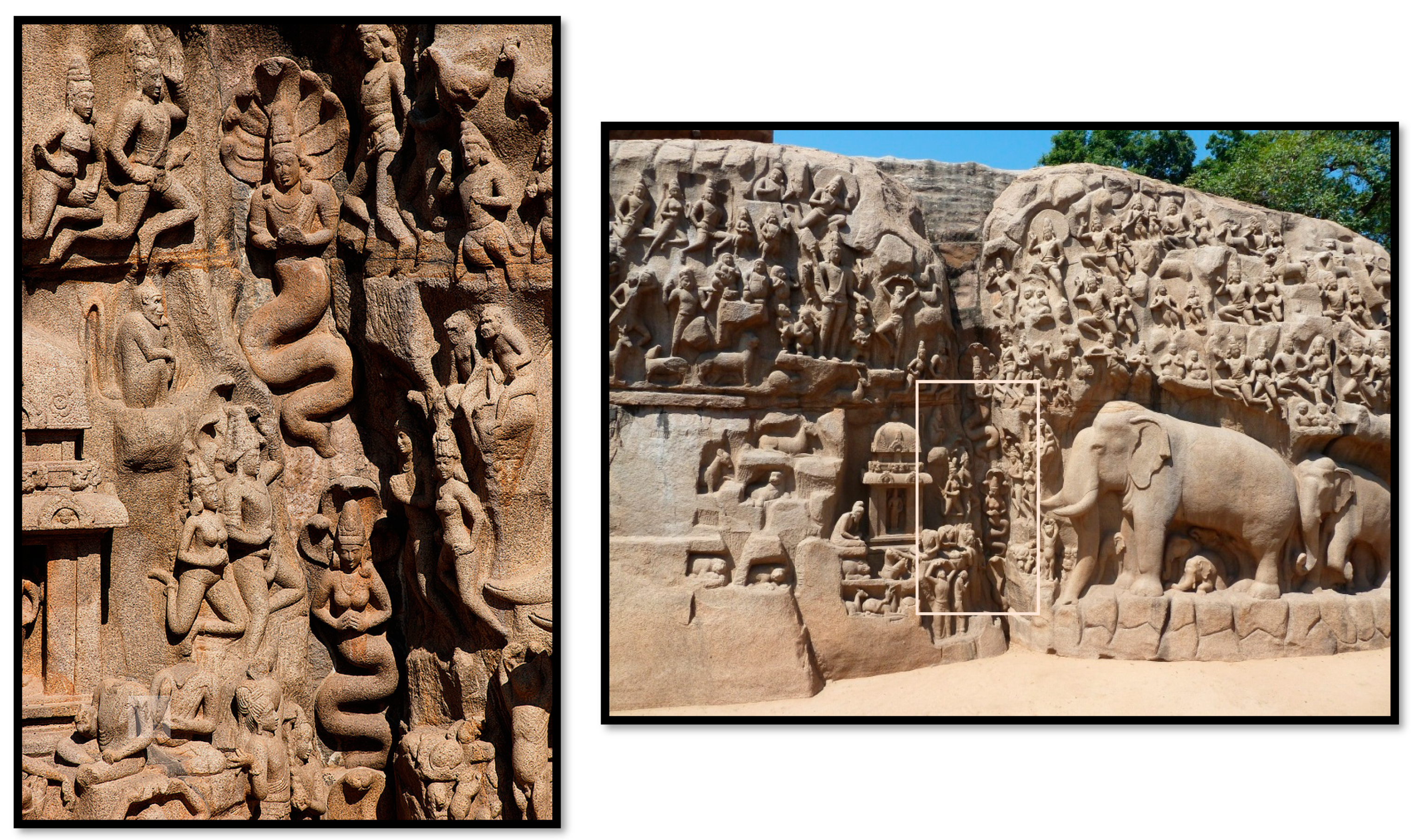

3. Human–Serpent Hybrids on Goan Pulpits

4. Colonial Architecture and Indigenous Traditions

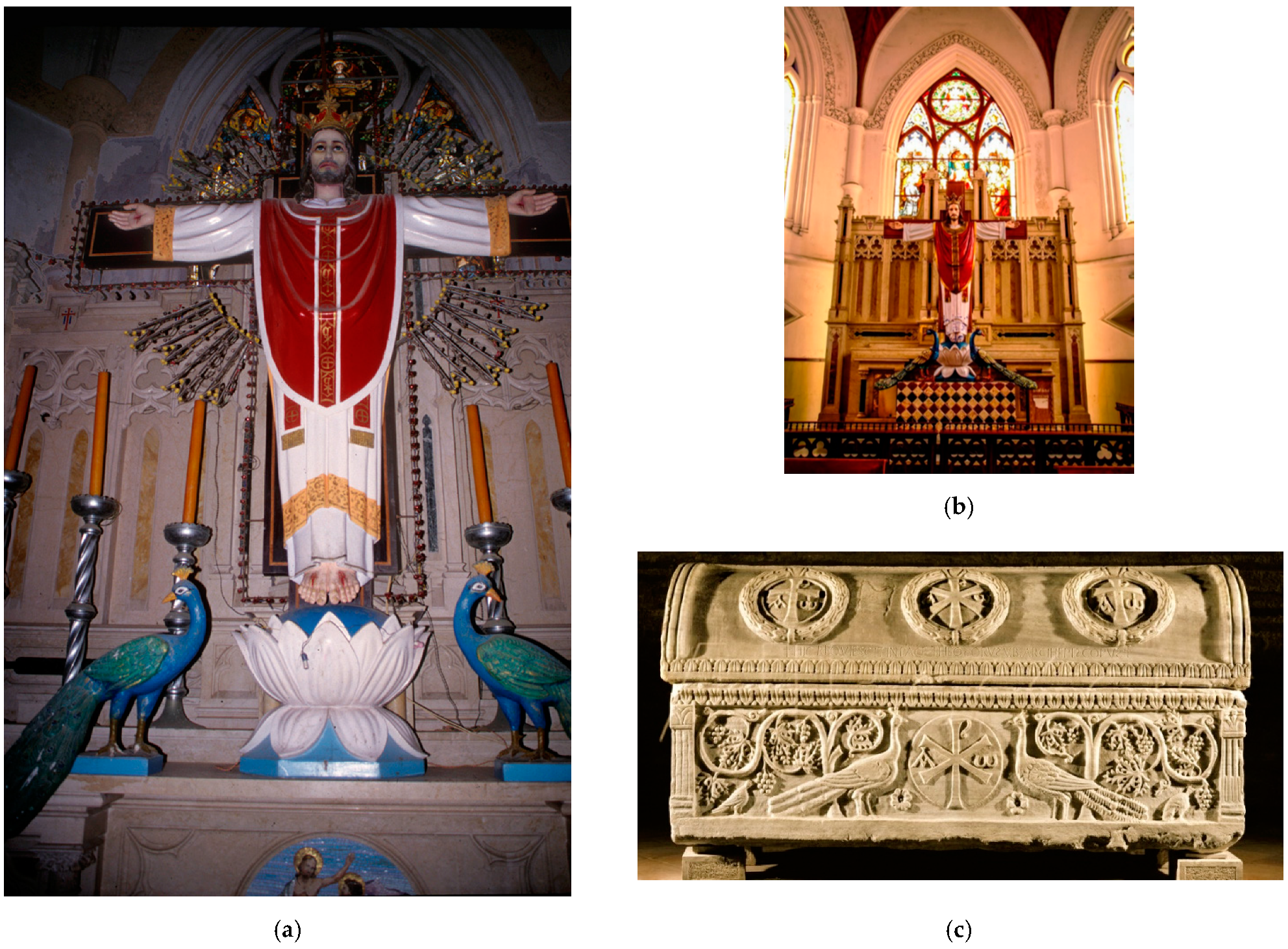

5. The St. Thomas Christians: Cultural Inheritance and Artistic Hybridity

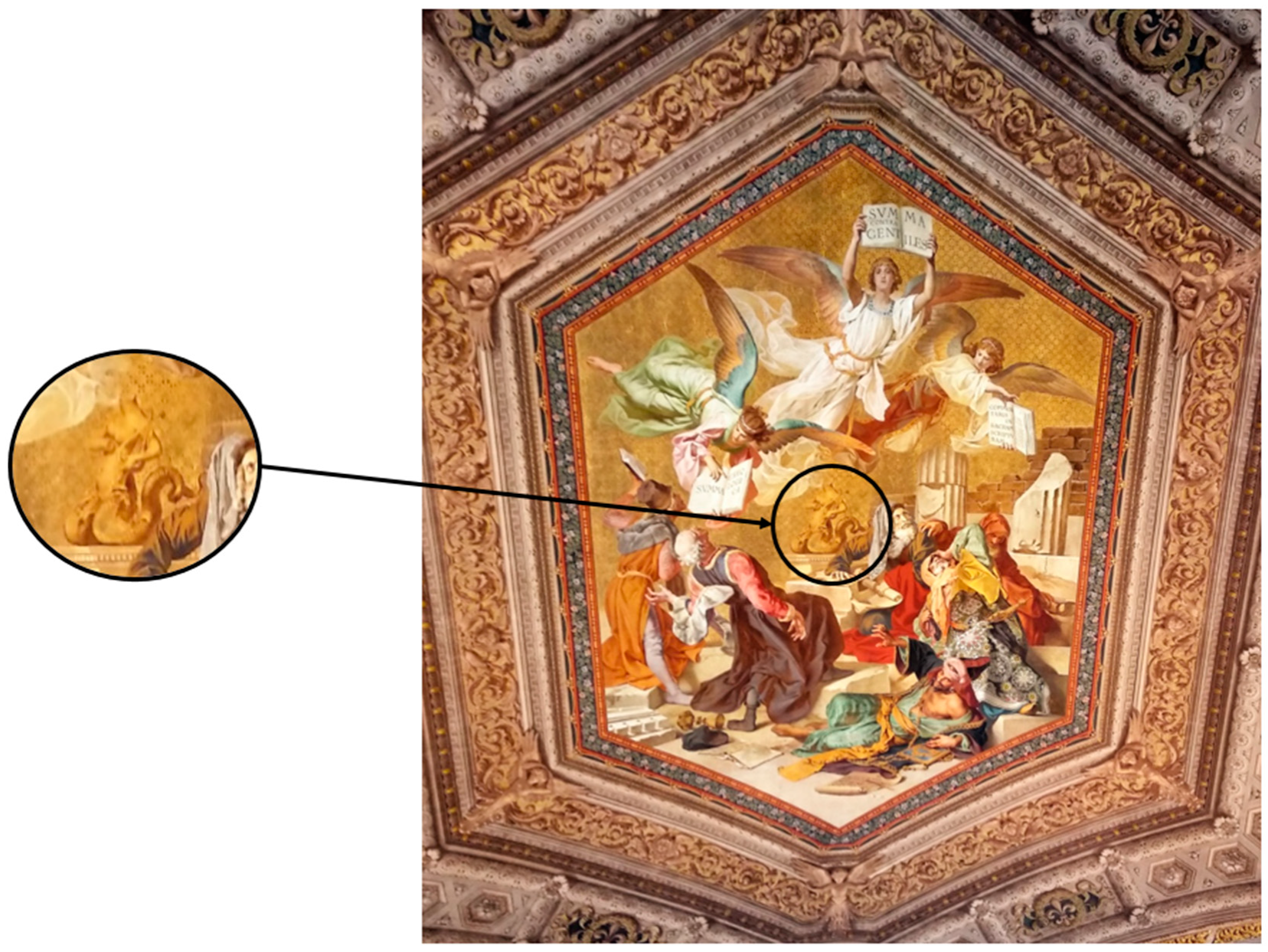

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

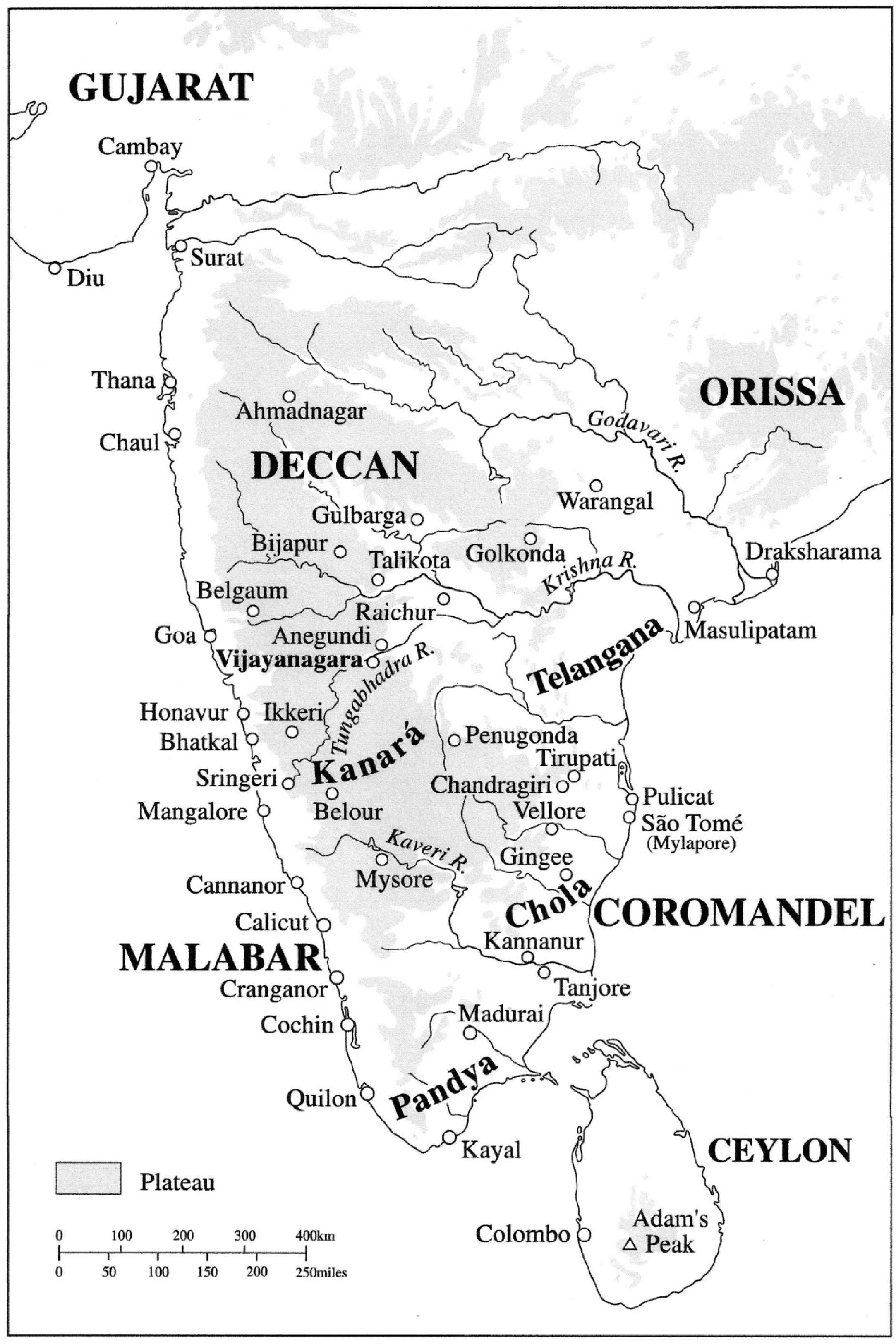

| 1 | Goa was ruled by Muslim invaders of the Deccan from 1312 to 1367. The city was then annexed by the Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar and was later conquered by the Bahmanī sultanate, which founded Old Goa on the island in 1440. Arabs had the monopoly of trade in the Malabar Coast until the arrival of the Portuguese. The Southwestern Coast of India was known as “Malabar” (a mixture of Tamil Malai and Arabic or Persian Barr, most probably) to the West Asians. Persian scholar al-Biruni (973–1052 AD) appears to have been the first to call the region by this name. |

| 2 | Ivory was commonly used in the local production of inlayed furniture, see: Pedro Dias, Mobiliário indo-português (Coimbra: Moreira de Cónegos, 2013). |

| 3 | See note 13 and John Irwin, “Indian Textile Trade of the Seventeenth Century,” Part 4, Foreign Influences,” Journal of Indian Textile History 4 (1959); K. N. Chaudhuri, Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean, Cambridge, 1985; James Boyajian, Portu-guese Trade in Asia under the Habsburgs, 1580–1640 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993); Hugo Miguel Crespo, Jewels from the India Run, Lisbon, Fundação Oriente, Catalogue of the Exhibition at the Museu do Oriente Lisbon 2015. |

| 4 | Early Indian texts on architecture such as the Vishnudharmottara Purana (6th c. CE) and the Brihat-samhita of Varahmihiri (7th c. CE) laid down details regarding the choice of suitable wood and the ceremony of procuring timber from the forest. |

| 5 | The standard pigments were malachite, terra verte, red ochre, red lead, deep red lac dye, yellow ochre, ultramarine and kaolin or chalk. See O.P. Agrawal, “A Study of Indian Polychrome Wooden Sculpture Agrawal, Studies in Conservation, Vol. 16, No. 2 (May, 1971), pp. 56–68. |

| 6 | This has been discussed, for example, in the 15th Triennial Conference, New Delhi: 22–26 (September 2008): Preprints, by ICOM Committee for Conservation. Meeting, Vol. II, p. 933. |

| 7 | Simona Cohen, “Animal Heads and Hybrid Creatures: The Case of the San Lorenzo Lavabo”, in Animals as Disguised Symbols in Renaissance Art, Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2008, pp. 195–239. |

| 8 | Jean Philippe Vogel, Indian Serpent-lore: Or, The Nāgas in Hindu Legend and Art, Probsthain, 1926; Indological Book House Edition, 1972. Esteban Garcfa Brosseau’s, “Nagas, Naginis y Grutescos: La iconograffa fantâstica de los pülpitos indoportu-gueses de Goa, Daman y Diu en los siglos XVII y XVIII” (PhD. Diss., UNAM, Mexico City, 2012). See Zupanov, “The Pulpit Trap”, pp. 298–315. and Midhun C. Sekhar, “Naga cult in Kerala”, in Kerala Naga Worship, Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute Thesis, chp. 4, 2015: https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/nagacultinkerala (accessed on 20 July 2021). |

| 9 | Naga representation is seen also in the wooden brackets of balikkal- maņdapa of the Thiruvanchikkulam Śiva Temple in Kerala (9th & 12th centuries). |

| 10 | See Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Art in the Jesuit Missions in Asia and Latin America, Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 2001; regarding the ‘Jesuit Style”, pp. 43–51; De Azevedo, “Churches of Goa”, pp. 3–6; António Nunes Pereira, “Re-naissance in Goa: Proportional Systems in Two Churches of the Sixteenth Century,” Presented at Nexus 2010: Relationships Between Architecture and Mathematics, Porto, 13–15 June 2010, Nexus Network Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2, (2011), pp. 373–96; Osswald, “Jesuit Art in Goa,” 263, pp. 274–76; L.B. Alberti (De re edificatoria, written between 1443 and 1452, published 1485); Sebastiano Serlio (Tutte l’opera d’architettura et prospettiva, Venezia, 1537), and Andrea Palladio (Le Antichità di Roma, Roma, 1554 and I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, Venezia, 1570). |

| 11 | e.g., The original ceiling was painted by the Florentine Bartolomeo Fontebuoni between 1613 and 1617. |

| 12 | Seventeenth century travelers Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri (Viaggi per Europa, 1693) and Pietro Della Valle (Viaggi, 1650–63) also likened the church to Sant’Andrea della Valle, which is the seat of the Theatine order. Regarding their writings on India, see Partha Mitter, Much Maligned Monsters, A History of European Reactions to Indian Art, Chicago & London, University of Chicago Press, (1977) 1992, 28–30, 40 and Nathalie Hester, Literature and Identity in Italian Baroque Travel Writing, Routledge, (2016): chp. 2. |

| 13 | An amalaka (Sanskrit) is a segmented or notched stone disk, usually with ridges on the rim, located on the top of a Hindu temple’s shikhara or main tower. |

| 14 | Portuguese records mention the demolishing of pagodas (temples) of Meliahpor. A shiva temple had been constructed there in the 7th century. |

| 15 | The Franco-Venetian Livre des Merveilles du Monde or Devisement du Monde, written in 1298–1299, was a collaboration between Marco Polo and a professional writer of romances, Rustichello of Pisa; Among the early translations was the Latin Iter Marci Pauli Veneti, made by the Dominican brother Francesco Pipino in 1302. See Louis Hambis (ed.), Marco Polo, La Description du Monde, Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck, 1955, 256; E. R. Hambye, “Saint Thomas the Apostle, India and Mylapore: Two Little Known Documents,” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 23, Part I (1960), pp. 104–10, esp.108 for English translation of the quotation. See also Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1939), pp. 364–65. See Nile Green, “Ostrich Eggs and Peacock Feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam,” Al-Masaq, Vol. 18, No. 1 (March 2006), esp. 42–47, 56–57. |

| 16 | See Varghese, “Plaza Crosses of St. Thomas Christians,” 4 and Carlo G. Cereti, Luca M. Olivieri and f. Joseph Vazhuthanapally, “The Problem of the Saint Thomas Crosses and Related Questions: Epigraphical Survey and Preliminary Research,” East and West, Vol. 52, No. 1/4 (December 2002), pp. 285–310. |

| 17 | See e.g., St. Augustine, Civitate Dei, Book 21 Chapter 4. trans. H. Bettenson (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972), 968. It is also associated with the resurrection of Christ because it sheds it old feathers and grows new ones each year. |

References

- Dale, Thomas E. A. 2001. Monsters, Corporeal Deformities, and Phantasms in the Cloister of St-Michel-de-Cuxa. The Art Bulletin 83: 402–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Carolyn, and Dana Leibsohn. 2003. Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America. Colonial Latin American Review 12: 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaky, Madhusudan A. 2013. The Vyala Figures on the Medieval Temples of India. Religions of South Asia 7: 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Doniger, Wendy. 2009. The Hindus, an Alternative History. New York: Penguin Press, p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Gusella, Francesco. 2019. New Jesuit Sources on the Iconography of the Good Shepherd Rockery from Portuguese India: The Garden of Shepherds of Miguel de Almeida (1658). Journal of Jesuit Studies 6: 577–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, Nile. 2006. Ostrich eggs and peacock feathers: Sacred objects as cultural exchange between Christianity and Islam. Al-Masaq 18: 27–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, Alexander. 2014. Hindu-Catholic Encounters in Goa: Religion, Colonialism, and Modernity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henn, Alexander. 2018. Shrines of Goa: Iconographic Formation and Popular Appeal. South Asian Interdisciplinary Journal 18: 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitter. 1992. Much Maligned Monsters, a History of European Reactions to Indian Art. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- von Mitterwallner, Gritli. 1983. Testimonials of Heroism: Memorial Stones and Structures. Goa: Cultural Patterns 35: 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Moxey, Keith. 2008. Visual Studies and the Iconic Turn. Journal of Visual Culture 7: 131–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxey, Keith. 2013. A “virtual cosmopolis”: Partha Mitter in conversation with Keith Moxey. The Art Bulletin 95: 381–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osswald, Cristina. 2011. Jesuit Art in Goa between 1542 and 1655: From Modo Nostro to Modo Goano. In Reinterpreting Indian Ocean Worlds: Essays in Honour of Kirti N. Chaudhur. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, chp. 10. pp. 255–86. [Google Scholar]

- Malekandathil, Pius. 2012. Merchants, Markets and Commodities: Some Aspects of Portuguese Commerce with Malabar. In The Portuguese, Indian Ocean and European Bridgeheads, 1500–1800: Festschrift in Honour of Prof. K.S. Mathew. Edited by Pius Malekandathil T. and Jamal Mohammed. Muvattupuzha: Mar Mathews Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malekandathil, Pius. 2019. Maritime India: Trade, Religion and Polity in the Indian Ocean, Revised ed. Delhi: Primus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rubiés, Joan-Pau. 2002. Travel and Ethnology in the Renaissance: South India through European Eyes, 1250–1625. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. 2004. Explorations in Connected History: From the Tagus to the Ganges. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabout, Gilles. 2015. Spots of Wilderness. ‘Nature’ in the Hindu Temples of Kerala. Edited by Fabrizio Serra. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01306640/document (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Varghese, Barnett. 2018. Plaza Crosses of St. Thomas Christians. Overview, July 2018. Available online: https://www.sahapedia.org/plaza-crosses-of-st-thomas-christians (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Xavier, Felippe Neri. 1961. Resumo Historico Da Maravilhosa Vida, Conversões, e Milagres de S. Francisco Xavier, Apostolo, Defensor, e Patrono Das Índias: Segunda Edição, [Historical Resume of the Marvelous Life, Conversions, and Miracles of Francis Xavier, Apostle, Defender, and Patron of the Indies, 2nd Ed.]. Novo Goa: Impresa Nacional, p. 406. [Google Scholar]

- Zupanov, Ines G. 2015a. The Pulpit Trap: Possession and Personhood in Colonial Goa. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 65: 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupanov, Ines G. 2015b. The pulpit trap. In Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics. Cambridg: Peabody Museum Press, vol. 65, p. 299. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cohen, S. Hybridity in the Colonial Arts of South India, 16th–18th Centuries. Religions 2021, 12, 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090684

Cohen S. Hybridity in the Colonial Arts of South India, 16th–18th Centuries. Religions. 2021; 12(9):684. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090684

Chicago/Turabian StyleCohen, Simona. 2021. "Hybridity in the Colonial Arts of South India, 16th–18th Centuries" Religions 12, no. 9: 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090684

APA StyleCohen, S. (2021). Hybridity in the Colonial Arts of South India, 16th–18th Centuries. Religions, 12(9), 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090684