2. Discussion of Inquiry

Andrea della Robbia’s enameled terra cotta sculpted altarpieces were among the few images at the Observant Franciscan monastery in the fifteenth century (

Baldini 2012;

Miller 2003). Unlike Conventual Franciscans who emphasized St. Francis’ life and his miracles, the Observant order strictly followed the Rule of St. Francis, his vow of poverty, and love of the Virgin; Andrea’s La Verna altarpieces likewise reflect the Saint’s devotion to the life of Christ and to the Virgin. As the location of St. Francis’s stigmatization, it is not surprising that De Riciis’ 1493 chronicle focused on the Chapel of the Stigmata, the heart of the monastery, with Andrea’s

Crucifixion altarpiece by providing a verbal picture of how a worshipper experienced this chapel (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The

Crucifixion with Saints Francis and Jerome accentuated the anguish of the Virgin with an inscription along the base (Jeremiah’s Lamentations [I:12]: O all ye that pass by the way attend and see if there be any sorrow like my sorrow; O VOS OMNES QVI TRA[N]SITIS P[ER] VIAM ATTE[N] DITE ET VIDETE SI EST DOLOR SCIVT DOLOR MEVS). With these words, the Virgin refers to Jeremiah’s loss at the fall of Jerusalem in the Old Testament as a way to describe her own sorrow at the loss of her crucified son (

Wallis 1973, p. 14). Significant to the present inquiry is Fra de Riciis’ description of the beholder’s interactive experience before the

Crucifixion in this chapel. He records the worshipper’s specific recitation and kneeling devotional pose, which mirrors that of Saints Francis and Jerome in the altarpiece (

Chiappini 1927, p. 333;

Miller 2010). Although De Riciis mentioned the

Annunciation altarpiece, he, unfortunately, provided no comparable account for how pilgrims engaged with Andrea’s two earlier altarpieces in La Verna’s Chiesa Maggiore (

Chiappini 1927, p. 335). However, his own chronicle and other relevant Franciscan literature, such as the

Meditations on the Life of Christ, suggest that worshippers actively engaged with devotional imagery and objects to inspire a religious experience. Therefore, De Riciis’ description of the pilgrim’s absorbed, “somaesthetic” experience before the

Crucifixion encourages a consideration of how a beholder would have interacted with other images and inscriptions at La Verna. Allie Terry-Fritsch defined somaesthetics as an awareness for how the body is attuned to sensory, aesthetic experiences and argued that, as a critical framework, the “viewer is a powerful tool” in the discovery of meaning (

Terry-Fritsch 2020, chp. 1). Such an approach can rely on how the viewer makes meaning through touch or smell, for instance (

Classen 2012;

Sarnecka 2020;

Karmon 2016;

Quiviger 2010). This essay, however, considers, in part, how the fifteenth-century lay person or pilgrim relied on visual, spatial, and textual cues (spoken and written) to interpret the altarpieces in the Chiesa Maggiore. The

Annunciation and

Adoration altarpieces are also interpreted through a Franciscan lens and contextualized by the monastery as a way to examine how the altarpieces inspired devotional experiences at the monastery.

Like the

Crucifixion altarpiece, the viewer of the

Annunciation and

Adoration altarpieces (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) was encouraged to empathize with the Virgin Mary, who was a model of prayer and piety and in this way a devotional guide for the worshipper visiting the monastery (

Reinburg 2012, pp. 214, 218). While the

Crucifixion altarpiece in the most sacred space of the monastery inspired a physical, interactive response before it, the

Annunciation and

Adoration altarpieces when read together implied a similar, albeit more modest interaction with devotees arriving at La Verna who would construct meaning through their presence by visually connecting the two altarpieces. Location is a meaningful factor in appreciating the altarpieces and the objectives of their viewers. Pilgrims embarked on a journey to this New Jerusalem because of the site’s significance. Conditioned by various devotional practices, rituals, and texts, including domestic worship, pilgrims and lay worshippers brought such familiar practices with them to La Verna, prepared to engage with the environment and its images. In this way, the beholder can be appreciated as a “critical technology” that augments the meaning of the altarpieces (

Terry-Fritsch 2020, chp. 1).

The “phenomenon” of the New Jerusalem pilgrimage experience likely dates to 1491 and the

sacro monte of Varallo, but in many respects, as argued by Ritsema van Eck, La Verna is the “primordial

sacro monte” due to the site’s physical connections to Francis’s stigmatization and the belief that the mountain of La Verna split at the moment of Christ’s crucifixion (

Ritsema van Eck 2017, pp. 247–49). As access to the Holy Land itself became increasingly difficult for the Christian west in the fifteenth century, local alternatives, such as the

sacro monte (sacred mountain) were developed to simulate such a pilgrimage, but to a “new” Jerusalem in the West. Throughout the sixteenth century, New Jerusalems, such as that at Varallo, became elaborate architectural and sculptural programs to provide the experience of visiting the Holy Land but without the foreign travel. Anna Giorgi noted that at the time of Andrea’s first La Verna altarpiece, the

Annunciation (c. 1476), La Verna was on its way to becoming the “natural”

sacro monte and Jerusalem of the West as described by De Riciis in 1493 (

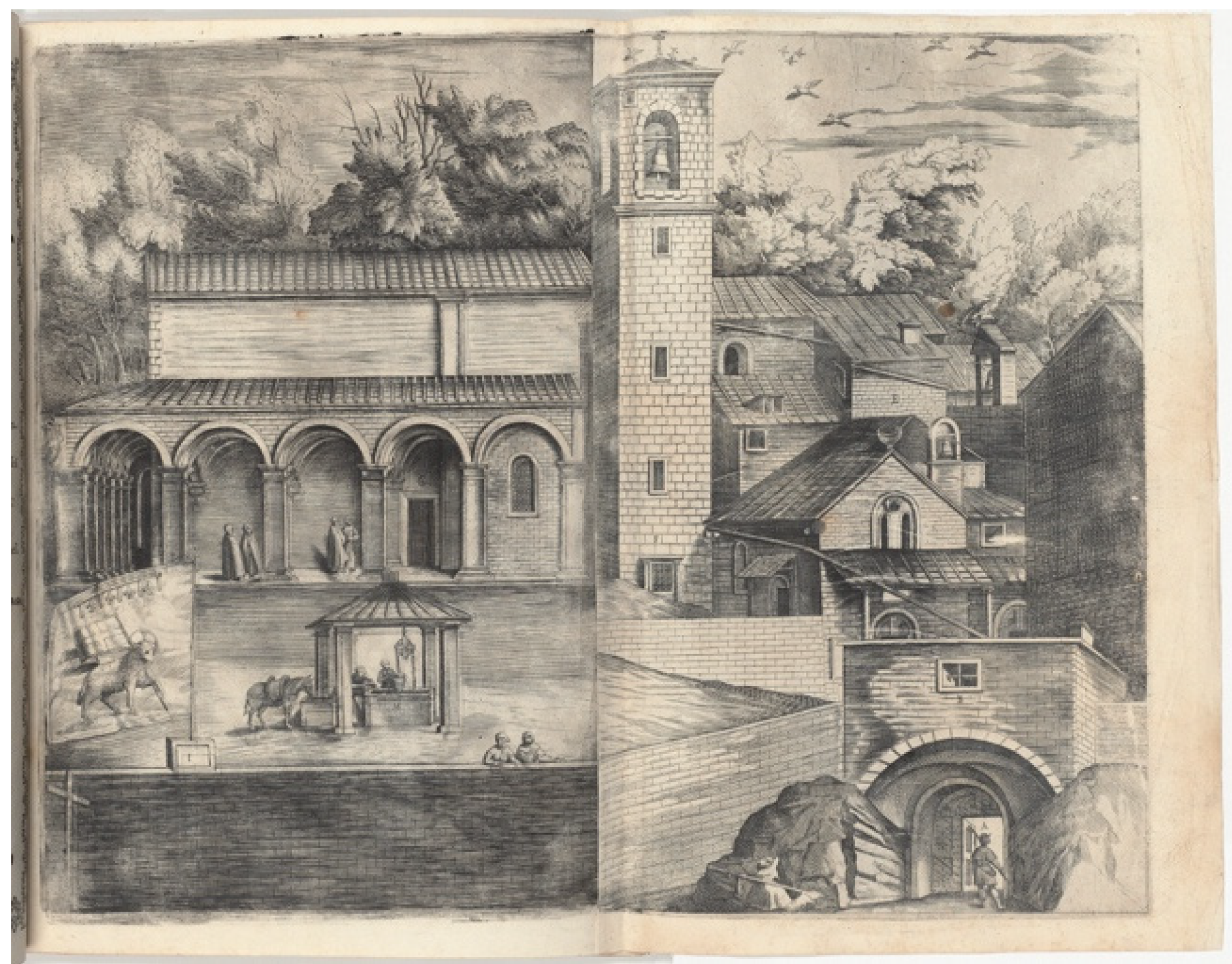

Giorgi 2012, pp. 56–57). Furthermore, she mentions Domenicino Ghirlandaio’s depiction of La Verna in the Sassetti Chapel in Florence’s S. Trinità (1483–1486,

Figure 2) as fairly characterizing the simplicity of the monastery before later architectural developments, such as the sixteenth-century additions of a guesthouse and a corridor leading to the Chapel of the Stigmata (

Giorgi 2012, pp. 56–57). By the time of Ghirlandaio’s fresco, most of Andrea’s La Verna altarpieces would have been installed.

Traditional art historical questions of interpretation and intention have rarely been posed to Andrea della Robbia’s numerous autograph works. This is true even of Andrea’s most frequently praised achievements, his La Verna altarpieces. A consideration of the

Annunciation and

Adoration reveals how Andrea and his work in enameled terra cotta complemented Observant Franciscan theology and how the compositions and inscriptions of these altarpieces in particular demonstrated Andrea’s artistic sensitivity and awareness of the devotional needs of visitors to the monastery’s public spaces and to the Chiesa Maggiore, in particular (

Baldini 2009, p. 417). The Virgin and her role in the Annunciation and Incarnation are uniquely emphasized in these altarpieces with their inscriptions to facilitate a refined understanding of the Incarnation as encouraged by Franciscan theology and devotional practices. The possible recitation of the Angelus prayer, with passages analogous to the inscriptions on Andrea della Robbia’s

Annunciation and

Adoration altarpieces in the Chiesa Maggiore, is discussed as an example of how the works inspired prayer.

3. La Verna and the Chiesa Maggiore in the Fifteenth Century

The La Verna monastery lacks a unified architectural plan, and its style and irregular appearance reflect the simplicity and poverty dear to Observant Franciscans.

1 The Chiesa Maggiore is expectedly plain (

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), and as the largest and last church built on the mountain, it was intended to accommodate the growing number of pilgrims to La Verna (see

Mencherini 1924;

Pope-Hennessy 1979, p. 180;

Lazzeri 1913;

Baldini 2014). In 1432, Florence was designated as the monastery’s protector with its wool guild, the Arte della Lana, responsible for facilitating donations to it, which explains the guild’s shield of arms on the church. A 1451 papal indulgence by Nicholas V expedited the completion of the Chiesa Maggiore by 1470, only to have most of it destroyed by fire in 1472. Donations for its rebuilding dramatically increased after the fire, which perhaps created an opportunity for the monastery’s caretakers to provide some artistic and decorative unity to a monastery that otherwise lacked formal harmony (

Pope-Hennessy 1979, p. 180). The church was fully restored by 1509.

Brothers at Franciscan monasteries rarely participated in artistic commissions as such decisions were often left to superiors, confraternities, or individuals and their families (

Bourda 1996,

2004, esp. pp. 16–31 and 148–55). Given the expanded role of Florence in the maintenance of the monastery, it is no surprise to find prominent Florentine families supporting the rebuilding efforts at the monastery and as patrons for most of the altarpieces commissioned from Andrea della Robbia, another Florentine (

Tripodi 2014). Other than the inclusion of family crests or names, there is no evidence of patron involvement regarding the La Verna altarpiece commissions. Four of the five altarpieces have inscriptions and indicate family sponsorship. Specifically, the Niccolini arms flank the inscription on the base of the

Annunciation, declaring them as the work’s sponsor. This is the first altarpiece commissioned after the Chiesa Maggiore fire, and it is usually dated on stylistic grounds between 1476 and 1479 (

Tripodi 2014, p. 165;

Marquand 1919, p. 30). The balustrade on the

Adoration’s tempietto is dated (1479) and identifies its patron as Jacopo Brizi of Pieve S. Stefano (

Tripodi 2014, p. 165, n. 54;

Paloscia and Bernacchi 1986, p. 48;

Mencherini 1924, p. 676). Flanking the inscription on the

Crucifixion are the arms of the prominent Alessandri family of Florence; Tommaso Alessandri’s and Andrea della Robbia’s names appear in the monastery’s

entrata e uscita in August 1481, the year given to the altarpiece (

Miller 2010, pp. 163–64;

Tripodi 2014, pp. 152–53). S.M. degli Angeli, the first building erected at the monastery and where Francis and his followers performed the daily mass, includes the

Madonna della Cintola (

Figure 10). This altarpiece was installed in the mid-1480s, and certainly by 1488, when the Bartoli and Ruccellai families were joined by marriage, thus explaining the appearance of both family crests on the predella, which also includes banderole bearing angels and a tabernacle (

Tripodi 2014, pp. 159–60;

Marquand 1922, vol. I, p. 78). This is the only La Verna altarpiece with a tabernacle, which is appropriate given the chapel’s original function. The inscriptions on scrolls in the predella all refer to John 6:51 (I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live forever; and the bread which I shall give up for the life of the world is my flesh) and the Eucharistic function of the altarpiece and church. The

Ascension of Christ (c. 1490;

Figure 11), originally intended for the high altar in the Chiesa Maggiore, is the only altarpiece without an inscription or family crest. It is regarded as a Medici family commission given that the presbytery and choir of the Chiesa Maggiore were under Medici patronage since 1457 (

Domestici 1991, p. 76;

Domestici 1995, p. 50;

Gentilini 1994, p. 94). The work cannot date later than 1493 when it was mentioned by De Riciis in his visit to the monastery (

Chiappini 1927, p. 332). When the altarpiece was moved to the nearby Ridolfi chapel in 1601, it is conceivable that if there had been Medici

stemme, or an inscription, they were removed at this time. Two

robbiane niche figures,

St. Francis and

St. Anthony Abbot, to the left and right on the chancel archway in the Chiesa Maggiore, are also considered Medici commissions and attributed to Andrea. The

Ascension as the Chiesa Maggiore’s high altarpiece is considered briefly at the end.

Despite the different sponsoring families for Andrea’s La Verna altarpieces, a sense of harmony in both style and theme was achieved, suggesting a degree of coordination that reflected Franciscan themes and tastes, possibly inspired by the influential St. Bernardino of Siena (c. 1380–1444) (

Pope-Hennessy 1979, p. 184;

Muzzi 1998, pp. 47–48;

Salmi 1969). By at least 1474, Andrea established a relationship with the Franciscan church, and the Observant order, when he worked with the Ugurgieri family of Siena, during the rebuilding of St. Bernardino’s church there, the Osservanza (

Domestici 1995, pp. 47–48;

Muzzi 1998, pp. 47–48). Andrea’s

Coronation of the Virgin (c. 1474) was made for the Ugurgieri chapel in the Osservanza and dates to the years immediately preceding the La Verna

Annunciation. St. Bernardino of Siena appealed to reform-minded Observant Franciscans. He was known for his dedication to poverty, love of the Virgin Mary, and his YHS emblem (

Pastor 1969, pp. 97, 233;

Moorman 1988, pp. 369–83, 446;

Rarick 1990, pp. 124–45). Like St. Francis, St. Bernardino emulated Christ’s commitment to humility and poverty, and his faith thus mirrored Francis’ values and devotion to Christ. Furthermore, Bernardino’s sermons repeatedly characterized Francis as an

alter Christus by drawing parallels between them, especially by emphasizing the stigmatization, a point that was sure to resonate at La Verna (

Debby 2008, pp. 83–84). In short, Bernardino was extremely popular and influential, and whose flair and direct preaching style, in part, led to the relinquishment of many Conventual Franciscan convents to the Observants, including La Verna in 1431 (

Barfucci 1991, p. 64;

Ritsema van Eck 2017, p. 285;

Tanzini 2012, p. 234). Andrea della Robbia’s altarpieces at La Verna, created in the wake of St. Bernardino’s canonization (1450), not surprisingly resonated with Bernardino-inspired, Observant Franciscan themes.

4. Franciscan Theology and the Appeal of Enameled Terra Cotta

Della Robbia’s five La Verna altarpieces offer a sense of visual and thematic unity to the monastery due to their common medium and themes influenced by St. Bernardino of Siena, whose sermons often highlighted the worship of the Virgin. Pier Paolo Ugurgieri of Siena may have been instrumental in this coordination (

Domestici 1991, p. 73). Pier Paolo Ugurgieri was associated with the artist as early as 1474 from Andrea’s

Coronation of the Virgin commission for his family’s chapel in the Osservanza. Pier Paolo was provincial vicar of the Observant order and keeper of La Verna in 1472, at the outset of a post-fire rebuilding campaign of the Chiesa Maggiore, when Andrea’s earliest altarpieces, the

Annunciation and the

Adoration (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) were created (

Gentilini 1994, p. 90;

Muzzi 1998, p. 43). From the start of this rebuilding, enameled terra cotta was the preferred medium for the monastery’s ornament, and in the 1470s, this medium was practiced exclusively by the Della Robbia family of Florence. As a remote mountainous location, the monastery posed challenges of inclement weather and poor accessibility. From Vasari to present-day scholars, enameled terra cotta offered practical advantages for a location such as La Verna (

Boucher 2001, pp. 14–16;

Baldini 2012, p. 244). The novel medium tolerated weather fluctuations and even the largest of Andrea’s works, the

Crucifixion, made of 720 individual sections, could be transported safely by shipping those sections in several boxes from his Florence workshop to the monastery to be assembled on-site. The chronologically earlier

Annunciation and

Adoration altarpieces must have been perceived favorably, for the medium and artist were chosen for the monastery’s subsequent high altarpieces in its three most public devotional buildings.

Composed of eighty-six interlocking pieces of enameled terra cotta, the

Annunciation is considered one of Andrea’s finest and most elegant reliefs. Across the aisle is the slightly more rectangular, ninety-five-piece

Adoration altarpiece (1479). Within the relatively spare interior of the Chiesa Maggiore, the shiny blue and white altarpieces are prominent and seem to coordinate with each other visually and spatially. Each altarpiece is set within a tempietto which strengthens their physical and formal association and gives the impression they could be read as a pair (

Domestici 1991, p. 73;

Muzzi 2000, p. 517). Characteristic of Andrea della Robbia’s style, both altarpieces have blue backgrounds with white figures in modest relief and a minimal use of accent colors, such as green for flower stems or hay. Both are framed in white, the

Annunciation with a classical palmette motif, while the

Adoration also includes Andrea’s signature cherub heads along the top. God the Father appears in both but more modestly so in the balanced composition of the

Annunciation and more boldly with additional angels in the

Adoration. Compared to Andrea’s three later altarpieces here, the Annunciation and Adoration are small and more rectangular with a horizontal composition. The

Crucifixion,

Madonna della Cintola, and

Ascension include more color, are substantially larger, oriented vertically, and have a more narrative quality. That is, the compositions are animated with many more expressive and gesticulating figures that assist in narrating the scenes. By contrast, the

Annunciation and

Adoration are significantly more restrained.

Stylistic and compositional differences notwithstanding, the Della Robbia altarpieces are united by medium. Authors from Pliny the Elder to Lorenzo Ghiberti morally equated terra cotta with modesty, innocence, and humility, qualities which complemented Franciscan ideals of poverty and simplicity (

Muzzi 1998, p. 46;

Panzanelli 2008;

Miller 2013, pp. 8–9;

Cambareri 2016, p. 43). For instance, Fra Giovanni Dominici suggested such material associations when he advocated that domestic devotional objects be made of simple materials because costly materials could interfere with genuine piety (

Domenici 1927, p. 35). Because Franciscans likewise upheld the virtues of humility and simplicity, these ideals were applied to church adornment. Andrea’s sculpture in enameled terra cotta suitably matched Franciscan preferences.

Admittedly, though, Andrea’s altarpieces are not simply baked clay. They are shiny, reflective, and brilliant. Andrea Muzzi contended that the relationship between the simple, lowly medium of terra cotta and Franciscan art appealed to the Franciscan desire for poverty and simplicity only on an intellectual level because the terra cotta sculptures were ultimately covered with enamel (

Muzzi 1998, p. 46). Nevertheless, the reflective white of the Della Robbia enamel could also symbolize the “invisible light of God” as described in Marsilio Ficino’s

De Lumine, in which the luminous reflections of enamel are equated with spiritual splendor and purity (

del Bravo 1973, p. 26;

Gentilini 1992a, pp. 101–6). Enameled terra cotta satisfied, at least theoretically, the desire for a humble, simple art form whose luminescence was also theologically associated with divine light and purity (

Gentilini 1992b, p. 445;

Kupiec 2016, pp. 106–7). The spiritually symbolic overtones of the white enamel glaze harmonized with St. Bernardino’s Franciscan reform sensibilities in which white enamel was a spiritual metaphor for light, God, purity, clarity, and innocence (

Domestici 1995, p. 47). Light was an essential symbol for St. Bernardino. His emblem was an emblazoned YHS monogram (Holy Name of Jesus), which depicted “rays of light” emanating from the monogram, often in yellow or gold, on a blue ground. This visual symbol of light was directly above and behind his head when he preached and became a popular devotional focal point for his congregants (

Debby 2008, p. 83). The radiating YHS emblem was augmented by St. Bernardino’s sermons which connected light and goodness. For example, he preached how “White is shining and resplendent: just as the virtuous soul is radiant and shines with the grace of God” (

St. Bernardino of Siena 1935, p. 168). The writings of the Dominican St. Antoninus, archbishop of Florence from 1446 to 1459, also associated white and purity, underscoring both the popular reach and influence of St. Bernardino but the growing familiarity of shining white as a symbol for purity and divinity (

Kupiec 2016, pp. 106–7;

Gentilini 1992a, p. 38). Catherine Kupiec elaborates that because white Della Robbia enamel literally reflected light, it could be conflated with light itself; thus Della Robbia altarpieces with enameled white figures could further communicate Christ as the Light of the World as from John 8:12 (2016, p. 106).

The symbolic meaning of white enameled terra cotta was broadly understood by fifteenth-century audiences, which legitimized among the faithful the outwardly sumptuous appearance of the lustrous and brilliant material. Pier Paolo Ugurgieri and other Franciscans could seize upon this familiar understanding and the words of St. Bernardino’s sermons and transform his metaphor of light into tangible reality through Andrea’s altarpieces. Taken together, the clay as well as the white enamel were understood as humble and pious materials and perfectly suited to the Franciscan caretakers at La Verna.

5. The Annunciation and Adoration: Inscriptions, Invocations, and Interaction

While the material of the altarpieces satisfies some general values of the Observant Franciscans, Andrea’s altarpieces at La Verna thematically, textually, and iconographically also demonstrate Andrea’s sensitivities to theological concerns and Renaissance devotional practices. Specifically, the

Annunciation and the

Adoration illustrate the Franciscan perspective of the Incarnation where Christ’s humanity and flesh pre-existed in the sinless Virgin. For instance, the Franciscan monk St. Bonaventure (c. 1217–1274), who wrote his

Journey of the Mind to God (1259) at La Verna, also stressed the Word and Incarnation in his theological writings and sermons. St. Bonaventure claimed that at the Incarnation it was “not simply that God became flesh, but that the Word, specifically, became flesh” and the flesh came from the Virgin Mary (

Hayes 1994, pp. 85–86;

Muzzi 2000, p. 521;

Bynum 1986, p. 422). Furthermore, Bonaventure, like the anonymous Franciscan author of the

Meditations on the Life of Christ, encouraged the

imitatio Christi, the imitation of Christ. The

Meditations urged the reader (viewer) to identify emotionally with the protagonists, particularly Christ and the Virgin (

imitatio Mariae)

. This text also explicitly stated, “let us contemplate the life of the Virgin in whom the Incarnation was effected” (

Bonaventura 1961, p. 10). Such empathetic imitation was a popular, contemporary form of devotion generally known as the

devotio moderna. Andrea della Robbia responded to such influences at La Verna where the concept of the Incarnation is similarly pronounced in these two Chiesa Maggiore altarpieces, and in which the significance of the Virgin and the Word/

verbum is distinct and crucial to their interpretation.

To address Franciscan theological and devotional needs, Andrea included inscriptions in all but one of the altarpieces at La Verna, which clarify the interpretation and foster worshipper interaction with the works and space. The La Verna altarpieces notwithstanding, base inscriptions of this nature are not regular features on Andrea della Robbia’s altarpieces. Of the others that include inscriptions, such as the Osservanza

Coronation of the Virgin, mentioned above, or the

Madonna and Child between Saints in the Medici Chapel in S. Croce (c. 1480), the inscriptions tend to identify the subject or patron. In the case of the Osservanza altarpiece, the inscription identifies the subject on a scroll within the composition. Notably, however, a Della Robbia

Crucifixion at Santa Maria Primerana in Fiesole (c. 1505–1550) duplicates the inscription from the La Verna

Crucifixion. Nevertheless, the La Verna base inscriptions are distinct. I suggest that the earliest two

robbiane altarpieces in the Chiesa Maggiore, the

Annunciation and

Adoration altarpieces, were intended visually, thematically, and textually as a pair to prompt pilgrim or beholder engagement. The altarpieces are across the nave aisle from each other (left and right, respectively) and, facing the entrance, are visible to the arriving worshipper (

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). Thus, rather than flush against the side walls of the church, the altarpieces are perpendicular to them, thus increasing their visibility from the church’s entrance. Specifically, the altarpieces coordinate within church environment and invite devotion through text and image.

The base of the

Annunciation altarpiece reads: ECCIE • A(N)CILLA • DO(MIN)I • FIAT • MIHI • SECV(N)DVM • VERBVM • TVV(M) (Behold the handmaid of the Lord; let it be done according to Thy Word). This text from Luke 1:38 is the Virgin Mary’s response to Gabriel’s announcement that she will bear the Christ child. The inscription thus identifies the image above as the moment

after Gabriel’s announcement when upon Mary’s acceptance, the Incarnation occurred, and the Word was made flesh. Andrea atypically placed the Virgin on the composition’s left with Gabriel at the right, who looks to the Virgin, perhaps listening to her response. A half-length figure of God the Father looks down on Mary, who just received her answer to Gabriel’s announcement. The descending Holy Spirit indicates Mary’s answer and acceptance of her role as the mother of God and the moment of the Incarnation. Andrea della Robbia included some traditional

Annunciation motifs, such as the symbolic lilies separating the two figures and the Virgin reading, presumably Isaiah’s prophecy of the virgin birth and Incarnation. However, placing the Virgin Annunciate on the left is uncommon in Italian Renaissance art (

Denny 1977, pp. 111–13). By reversing her traditional location, the Virgin Mary’s active speaking role is emphasized with her words on the base moving from left to right, establishing a narrative flow, and underscoring the Virgin as the vehicle of the Incarnation (

Denny 1977, p. 136). It is perhaps noteworthy that Andrea never again repeated this format. With the Virgin at the composition’s left, she is more legible from the entrance and faces the center of the church. Conceivably, this arrangement supports the left-to-right reading of the text as well as the site-specific nature of the work.

The Latin inscription on the base of the Adoration is essentially the immediate response to the Annunciation altarpiece: VERBVM CARO • FATTV(M) • EST • DE VIRGINE • M(ARI)A (the Word was made flesh from the Virgin Mary). Two points are clearly made in the Adoration inscription—not only is the Word, from God the Father, made flesh, but the flesh is of the Virgin Mary. God the Father with flanking half-length angels bearing a banderole of music reading Gloria in Excelsis Deo makes for a rather dynamic composition. The remaining imagery initially appears as a traditional Adoration or Nativity scene, but the base inscription defines it as the Incarnation through its reference in this case to John 1:14: the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us. Although the inscription alludes to John, the subtle deviation from it once again emphasizes the role of the Virgin Mary: the Word was made flesh from the Virgin Mary.

Zuzanna Sarnecka noted a similar shift in emphasis when it comes to this subject and inscription on domestic devotional objects (

Sarnecka 2019, pp. 176–77). Relatedly, the small-scale objects she considers are glazed terracotta for the home environment where they can be picked up and touched. Compositionally, the

Adoration is like many other smaller versions by Andrea and his uncle Luca della Robbia, with the haloed Child on a wedge of green hay off-center to subtly shift the focus to the adoring Virgin, whose head is nearly in the center of the composition. The compositional type had become popular in the 1450s as a “visual metaphor for the Incarnation, penitence, and eremitical religious devotion” (

Holmes 1999, p. 172;

Ruda 1993, pp. 218–28). Essentially the visual language of the Adoration or Nativity symbolized the Incarnation, and in the case of the La Verna altarpiece, the inscription literally defines it so. The popularity of this subject for the domestic environment likely accounts for the many smaller versions of this subject by Della Robbia (

Sarnecka 2019). In fact, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s

Virgin Adoring the Christ Child (after 1479) is described as a variant of the large Brizi (La Verna)

Adoration (

Figure 12); this smaller-scaled work would have been suitable for home worship, but as with most such objects, we cannot determine a specific household. Nevertheless, images of the Virgin and Child, in all media, are found in abundance in domestic inventories from the Italian Renaissance and frequently noted in bedchambers (

Cooper 2006;

Sarnecka 2020, p. 6). Another interesting parallel between the La Verna

Adoration and other Della Robbia versions, such as Luca della Robbia’s smaller-scaled

Nativity with Gloria in Excelsis (c. 1470; Boston Museum of Fine Arts) or the Della Robbia

Nativity panel variously attributed to one of Andrea’s sons in S. Maria degli Angeli, is the inclusion of musical references (

Sarnecka 2019, pp. 177–78).

Medieval and early Renaissance literature, such as the

Golden Legend or the

Meditations on the Life of Christ, advocates reading the altarpieces as visual and textual commentaries on the Incarnation. For example, the

Golden Legend’s account of the Annunciation explicitly connected it with the Incarnation: “And it was fitting that an angel should announce the Incarnation, because in this guise the fall of the angels was repaired… The Incarnation in sooth took place to repair not only the fall of man, but the ruin of angels….” (

da Voragine 1969, p. 204). The

Meditations also expressed how the Incarnation was immediate upon the Virgin’s acceptance: “Then the son of God forthwith entered her womb without delay…At that very point the Spirit was created and placed into the sanctified womb” (

Bonaventura 1961, p. 19). Andrea’s

Annunciation depicts the moment after Gabriel’s announcement, the Annunciate’s response and Incarnation. Through the focus on her response rather than Gabriel’s address, the altarpiece visually and textually promotes devotion to the Virgin. The inscriptions on both altarpieces fundamentally augment the interpretation of the image rather than merely identify the subject.

Roger Tarr discussed Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Annunciation (1344;

Figure 13) as a relevant example whereby the painting’s text elaborates on the image by eliciting a verbal or read response from the image’s beholder (

Tarr 1997, p. 77;

Van Dijk 1999). The visible “spoken words” within Lorenzetti’s

Annunciation also reflect on the Incarnation where instead of announcing that the Virgin will bear the Christ Child, Gabriel’s words on the painting read “

Non est (erit) impossibile apud Deum omne verbum” (Nothing is impossible for God’s Word) and Mary’s reply, “

ecce ancilla domini” (Behold the handmaid of the Lord) (

Tarr 1997, p. 225). Their words are worked into the gold ground of the painting as if they were actually spoken, issuing from their mouths. Mary’s response in Lorenzetti’s work leaves unsaid Luke’s remaining passage, let it be done according to Thy Word (

Tarr 1997, p. 226). Tarr contended the spoken word

verbum in this passage becomes “the vehicle for the transmission of God’s will” (1997, p. 226). The complete phrase in Andrea’s

Annunciation makes clear the Virgin has accepted her role according to the Word and her significance in the Incarnation.

Verbum, both spoken and written in the Annunciate’s expanded response in the La Verna

Annunciation, literally supports the divine mystery above. The bold placement of the text across the base, furthermore, implies more than a passive spectator before the altarpiece but rather one who will read or speak the Virgin’s spoken words as well. Jessica Richardson elaborated on Tarr’s scholarship to suggest that “depicted speech” need not be contained within the pictorial space itself but rather can extend into the viewer’s space, where the beholder in front of the work completes its meaning, prayer, or ritual (2019, p. 354).

Biblical inscriptions were familiar features on Renaissance religious images to identify subjects, to make visible words spoken by the image’s protagonist, adding depth to an image’s interpretation through invocations that invite the beholder to participate in the event (

Richardson 2019;

Wallis 1973). Including the Virgin’s words as the inscription on the La Verna

Annunciation emphasizes the Incarnation and underscores her central role in it. Moreover, when the

Annunciation is read together with the

Adoration, the inscriptions invite prayer from the worshipper in the space before and between the two altarpieces. The pilgrim entering the Chiesa Maggiore, standing in the nave between these sculpted altarpieces, physically connects them and experientially creates additional meaning.

The

Adoration’s inscription also emphasizes that the “Word was made flesh from the Virgin Mary”, thus highlighting her role in the Incarnation, complementing her centrality in Andrea’s composition. This inscription might refer to a significant passage from the Nicene Creed recited at Mass, “…and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the Virgin Mary, and was made man.” Despite similarities between the inscription and the Creed, I would suggest that the Angelus prayer offers a closer parallel. In fact, the Angelus prayer’s most relevant passages unite the inscriptions on both the

Annunciation and

Adoration altarpieces. The Angelus, originally recited in the evening, at the supposed hour of the Incarnation, is a recitation that evolved among Franciscans, and, in fact, was encouraged by St. Bonaventure as a prayer dedicated to the Incarnation (

Thurston 1901,

1907):

Behold the handmaid of the Lord

Be it done according to thy Word.

The Word was made flesh

And dwelt among us

These passages from the Angelus, borrowing from both Luke and John, are then followed by Hail Marys, and the remaining prayer is likewise devoted to the Incarnation. The specific passages from the Creed and, more convincingly, the Angelus prayer support the visual and textual evidence in both altarpieces and suggest an interaction with and response (vocal or read) by the worshipper/pilgrim before the altarpieces as encouraged by contemporary literature and devotional practices. Regarding the Angelus, for instance, one must imagine a pilgrim, who, according to tradition, would pause at the compline bell to offer devotion to the Incarnation by reciting this prayer, verses of which are referenced on Andrea’s altarpieces. The inscriptions, particularly the text on the Annunciation, can refer to a viewer and reader, as well as to a speaker reciting the Virgin’s spoken response/inscription as one’s own prayer, who in an extreme act of piety empathizes with Mary by speaking her words. The sense of sound, real or imagined, augments the worshipper’s experience before the altarpieces. The musical references in the Adoration also simulate an auditory experience, but one that is loud and joyful, even if only imagined.

By considering the

Annunciation and

Adoration as a pair or as pendants, the beholder physically facilitates the interaction between the altarpieces. Allie Terry-Fritsch describes such an experience at an early sixteenth-century Franciscan pilgrimage site outside of Florence, dubbed the New Jerusalem at the

sacro monte of San Vivaldo in Tuscany (

Terry-Fritsch 2020, pp. 161–215). Visitors who made the pilgrimage to San Vivaldo visited its various spaces and structures built to create a simulated experience of visiting the Holy Land and its sacred locations. Among the visual experiences are a pair of relief sculptures on the exteriors of two buildings, an

Ecce Homo and a

Crucifige, between which the pilgrim would physically mediate the “spatial gap” between the works creating an immersive environment for the beholder to contemplate numerous devotional scenarios (

Terry-Fritsch 2020, pp. 193–94). As a

sacro monte, La Verna, too, was described as a Jerusalem in the West, but its sites of devotion were far less developed than San Vivaldo. However, La Verna had the virtue of being the actual site of St. Francis’ stigmatization as well as being formed at the moment of the Crucifixion. It was believed the formation of La Verna’s deep chasms and fissures occurred at the very hour of Christ’s death when the Gospel says that the rock split, Matthew 27: 50–52 (

Ritsema van Eck 2017, p. 259). Nevertheless, the devotional practices before and between images at these modestly later sites offer a meaningful way to consider the altarpieces in the Chiesa Maggiore. Worshippers arriving at La Verna, physically invested in the trek up the mountain, were eager to experience the environment where St. Francis lived and prayed (practices they sought to emulate). Within the austere interior of the Chiesa Maggiore, the two altarpieces, left and right of the nave, read like a prayer book or at least hint at such object association and familiar form of domestic devotion; both altarpieces and prayer books inspired devotional reading and engagement with imagery. Virginia Reinburg offers a useful analogy on medieval books of hours whereby the book provides the “personal script for prayer—as like the two panels of a diptych” (2012, pp. 214–17). Furthermore, in books of hours, the Annunciation was usually the first image illustrated and it was then followed by an invocation or “dialogue” with God (

Reinburg 2012, pp. 214–17). The diversity of objects used as meditational prompts in the Renaissance encourages a kind of cross-fertilization whereby one form could influence or inform how other forms were used and interpreted. The prayer book is also instructive for it reminds us that devotional reading rarely required a command of Latin or grammar, was often performed before images, and was a form of prayer that could be silent or vocal, in which the written words might only serve as initial prompts for the most familiar prayers that one “already knew by heart” (

Reinburg 2012, p. 111).

Worshippers visiting La Verna were already conditioned by their everyday devotional routines practiced in their homes or hometown liturgical settings, and they brought those familiar rituals and practices with them to La Verna. Subsequently, the beholder at La Verna standing between the

Annunciation and

Adoration altarpieces had various approaches and strategies by which they could experience the works and space, which in turn could motivate deeper meaning and engagement. The tactility of the relief sculptures, their reflective surfaces, and their inscriptions as prompts for prayer, “activate and emplace” the worshipper at La Verna who drew upon a tradition where images were cues for various devotional activities to aid their meditative practices (

Terry-Fritsch 2020, p. 19;

Williamson 2004, pp. 386–87). These traditions included prayers before the popular Marian images found in fifteenth-century homes, often lit by candles during private devotions (

Sarnecka 2019;

Kupiec 2016, pp. 112–16). Given the similarity of theme and potentially material, such domestic works might have informed how visitors engaged with and perceived the Chiesa Maggiore altarpieces, especially when they were likewise illuminated by candles on the altars before them. This reciprocity of religious experiences and objects seems especially meaningful for domestic religious images in enameled terracotta or majolica as it could blur the distinction between familiar and unfamiliar settings. When one returned home from their visit to the

sacro monte of La Verna, for instance, their domestic devotional objects could have additional resonance because of this new experience. Zuzanna Sarnecka describes curious majolica model chapels and sanctuaries that were produced mostly in Urbino in the sixteenth century (

Sarnecka 2020). One such example is a model La Verna sanctuary that dates to 1521 (

Sarnecka 2020, pp. 12–13). The unknown owner might very well have used the miniature sanctuary to memorialize a pilgrimage to the monastery, like a devotional souvenir, to embark on a “mental pilgrimage” by visually navigating the different buildings in the model monastery and thereby interacting with it as a devotional aid (

Sarnecka 2020).

In 1493, Fra Alexandro de Riciis described practices that demonstrated how such cultural emplacement and imaginative connections occurred with worshippers to La Verna’s most sacred site in the Chapel of the Stigmata with its

Crucifixion altarpiece. The importance of location resounds potently in this chapel, and the

Crucifixion binds the subject to the location where St. Francis, meditating on Christ’s suffering, saw a vision of the seraphic crucifix and received the stigmata (

Miller 2010, p. 164). The

Crucifixion altarpiece served as a visual and textual prompt for the beholder, who would stand on the same rock as Francis to recreate and emulate his meditations and his visionary experience. The beholder experience in the Chapel of the Stigmata offers a model for how a beholder could engage with the

Annunciation and

Adoration altarpieces. Although lacking the profundity that resonates at the Chapel of the Stigmata, the Chiesa Maggiore was the largest public devotional church on the mountain, built with the intention of receiving eager worshippers. Just like the model sanctuary of La Verna mentioned above that could be picked up and explored with hands and eyes, visiting worshippers to the actual sanctuary likely sought to engage with the entire space of the remote sanctuary, including the Chiesa Maggiore.

Were one to enter the Chiesa Maggiore in the 1480s, one would see the two

tempietti housing and drawing attention to the

Annunciation and the

Adoration. Because they are visually and thematically related, one can imagine the worshipper connecting them, engaging with the altarpieces and the space. By 1493, the high altarpiece in the Chiesa Maggiore, the

Ascension of Christ (

Figure 11), was in place. The effect must have been stunning, with the

Annunciation and the

Adoration essentially flanking the much larger

Ascension (680 pieces) between them. Compared to the flanking altarpieces, the

Ascension is taller, more colorful, and includes many more full-length figures. The composition depicts the apostles and the Virgin Mary in the lower half of the altarpiece, closer to the beholder, and the ascending Christ flanked by three-quarter-length angels are in the upper half. The figures are more animated, expressive, and in bolder relief than Andrea’s work of the 1470s. The shape of the altarpiece echoes that of the chancel arch that originally framed the work when it was at the high altar, suggesting the artist and his workshop accommodated the space of its intended location. Without an inscription, one can only speculate on how the beholder might have interpreted the

Ascension especially in the context of the

Annunciation and

Adoration. While these two earlier works readily function as a pair, regardless of the presence of the high altarpiece, how might the

Ascension function with the pair? Visually and spatially, the three altarpieces read as a triptych across the space of the Chiesa Maggiore, with the

Annunciation and

Adoration as the “outer wings” to the central panel, for instance. Thematically, the “wings” of this triptych mark the beginning of Christ’s mortal life, while the

Ascension marks the end of his life on earth. Passages from the Golden Legend and the

Meditations on the Life of Christ promoted a reading of all three subjects together (

da Voragine 1969, p. 290;

Bonaventura 1961, pp. 381–82). For example, when referring to those who ascended with Christ, Jacobus da Voragine wrote of “certain angels who did not have full knowledge of the Mystery of the Incarnation, Passion, and Resurrection; and seeing the Lord ascending into Heaven by his own power, with a multitude of angels, and of holy men, they wondered at the mystery of the Incarnation and the Passion…” (1969, p. 290). Conceivably, then, the worshipper could continue to engage the space of the Chiesa Maggiore with the third altarpiece, one that also coordinated visually and possibly thematically with the

Annunciation and

Adoration.