Abstract

Marian apparitions attract modern masses since the 19th century. The radical message of the apparition asking for penitence and the return of public and politics to God resonated well within major parts of Catholicism. While popes kept promoting Marian pilgrimages in order to secure their public and political standing throughout the 20th and 21st century, they tried to control the masses and to attenuate the messages. Particularly since the Second Vatican Council, the popes tamed mobilization. Instead of stirring up the masses, popes kept modest at Marian apparitions sites. A quantitative analysis of the papal documents issued during papal journeys to Fatima, the most political apparition of the 20th century, shows that a modest religious discourse about God and world had been presented instead of promoting the critical messages of the apparition. Following the methodological ideal of parsimony, the analysis concentrates on the most uttered words during the journeys and compares the four pontificates since Paul VI. Instead of stressing the radical message of Fatima, which is introduced in the discussion of the findings, the pontificates share a modest Catholic discourse.

1. Introduction

Modern Marian apparitions have a long history of mobilizing the masses. The mass production of devotional objects, such as the Medaille miraculeuse of Rue due Bac in Paris, spread Marian devotions associated with these apparitions across the Catholic world. When Lourdes was connected to the railway system, it became the paradigmatic shrine for modern Marian pilgrimage and devotion (Harris 1999; Kaufman 2005; Körner 2018). As Diarmaid MacCulloch pointed out, “Protestants went on trains to the seaside, Catholics to light a candle in a holy place” (MacCulloch 2010, p. 820). However, Marian pilgrims did not only light candles and buy souvenirs, or hoped for healing of their health or a betterment of their private situation. Marian apparition came with a strong political message. In the context of an ongoing secularization process, the Virgin Mary appeared in order to warn public and politics to return to God, flee sin, pray the rosary and do penitence in order to avoid the threatening chastisement of God for the sacrileges of the times (Di Stefano and Ramón Solans 2018; Hermkens et al. 2009a; Margry 2020; Maunder 2018; Zimdars-Swartz 2014).

Within the Catholic universe, the authenticity and thus the legitimacy of an apparition depends on the final acceptance of the seers’ claims by the local bishop and the pope. If the pope accepts that the seers have indeed encountered the Virgin Mary, the apparition is taken as given. This papal power to review and judge, to accept and reject apparitions binds Marian apparitions and popes closely together. The papacy of the late 19th and the first half of 20th century increasingly mobilized these masses for the struggle first against liberalism, then against nazism and, primarily, communism. The event of the apparitions and its critical messages against an increasingly secular public and state (Margry 2020) were used as a force against the modern errors, as Pope Pius IX condemned liberalism, nationalism and socialism in his famous syllabus of 1864. Masses were understood as partners against anti-papal, liberal, laicist and nationalist elites. Under the pressure of national and liberal, later also fascist and socialist, movements, the popes were often ready to side with the masses as soon they embraced Catholicism, whatever ideologies they found attractive in addition. Marian devotion was an important vehicle for this agenda. Leo XVI’s seminal encyclical Rerum Novarum (1891) marked the beginning of a Catholic socialism that resisted atheist Marxism but argued for labor rights against capitalist exploitation. The popes were also ready to side with nationalist projects if they allied with Catholicism. Pius XI agreed to the Lateran Treaties with Italy under fascist rule in 1929, which established the State of the Vatican City and compensated the loss of the Papal State financially and, maybe most importantly, secured a dominant position of the Catholic Church within the Italian education system. The secular radical and totalitarian ideologies competed for the masses and the popes were ready to engage in this contestation. They made deals and compromises with various elites and states but were keen on having a direct contact with the Catholic masses. Marian apparitions helped them to engage with the faithful masses in order to strengthen their piety but also in order to project the power of mass mobilization externally (Barbato and Heid 2020; Duffy 2014; Pollard 2014).

In 1917, during World War I and the pontificate of Benedict XV, the most important Marian apparition of the 20th century happened in Fatima, Portugal (Bennett 2012; Bertone and De Carli 2008; Walsh 1990). The seers’ claim was accepted as authentic by the local bishop and the pope in 1930. The message of Fatima echoes the strong call for conversion and penitence of the previous apparitions, after the revelation of the first of two secrets. In 1942, on October 31, Pope Pius XII broadcasted via Radio Vatican his consecration of the world to the Immaculate Heart of the Virgin Mary, accompanied by his substitute Montini, the later Paul VI. Via radio he was connected with the Portuguese episcopacy gathering in Fatima for the 25th anniversary of the apparition. Since that event, the public ties of popes and Fatima never ceased to exist. Popes visited the place since Paul VI started papal travelling. John Paul II repeated the consecration of the world in 1982 after he associated the failure of the attempt on his life on the 13th of May 1981 to the protection of Our Lady of Fatima. In 2000, the much debated third secret, in which the execution of a pope took place in a destroyed city, was published by the Congregation of the Faith and interpreted by the then prefect Joseph Ratzinger and later Pope Benedict XVI; the first two secrets about hell, war and Russia were already published in 1942, which established an anti-communist discourse that dominated the Fatima perspective during the initial years of the Cold War. At the centennial of the apparition, Pope Francis canonized the seer children Jacinta and Francisco. They had died at a young age from the Spanish flue soon after the apparitions and had been beatified by John Paul II in 2000.

While the papal relation to Fatima might have been closer than to any other Marian site and the messages of Fatima were as demanding as those of previous apparitions, papal calls to follow the demands of messages were much more moderate than the close relations and interactions could indicate. While the popes obviously continued to back the apparition site, they did not urge the faithful flock which gathered there to act according to the revealed messages. This claim is based on the analysis of the addresses the popes gave during their visits in Fatima and Portugal. During a period of 50 years, from the 50th to the 100th anniversary, four papal visitors came to Fatima. Paul VI was there in 1967 in order to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the apparition. John Paul II came three times: in 1982 to thank for the survival of the assassination attempt; in 1991 for the anniversary of his survival and then in the Holy Year 2000 for the beatification of Jacinta and Francisco. Pope Benedict XVI visited Fatima in 2010 for the anniversary of the beatification. Pope Francis came in 2017 to celebrate the 100th anniversary and to canonize Jacinta and Francisco.

The analysis in this article is based on a broader sociological understanding of politics. A narrower understanding of politics focuses on states, governments and public policies, and its binding and enforceable decisions. It tends often to exclude religion, religious actors or religious masses, particularly under the condition of a secular framework of governance as it has been established in Europe since the 19th century. Within this secular framework of politics, political power is measured and legitimized within the matrix of the state and its institutions. Religious actors, such as the pope, are integrated in such a narrow framework of politics as provider of ethics and values. There is an extensive debate going on how to find a normative and empirically fitting place for religious actors in politics and political analysis. Certainly, both sides have their merits, however this broad debate on religion and politics cannot be tackled here. Charles Taylor’s work might be mentioned as an outstanding example of this debate (Taylor 2007).

The papal case is particularly interesting in this respect as the popes are without doubt both religious and political actors. The pope is not only the ruler of the Church who is able to make binding decisions, which are embedded in the legal system of Canon law, he is also the monarch of a state (Vatican City). While his micro state has only a limited reach, the institution of the Holy See, which is a legal subject of international law, turns the pope into a diplomat among states and an eminent political global player. A growing debate in political sciences and related interdisciplinary fields takes this political aspect of the papal agency into account (Barbato 2021, 2020; Barbato et al. 2019; Bátora and Hynek 2014, pp. 87–111; Rooney 2013).

The popes are certainly pastors, but they are also politicians. One could argue that the popes are, due to their role as leaders of the Church, foremost politicians or that their pastoral duty is indeed a political one, as the shepherd has the duty to provide goods for and protection to the flock. On the other hand, one could argue that there is a tension between this-worldly political service to mankind, including the well-being of the Catholic community and the Church institutions, and a more spiritual concern for the salvation of the souls, Catholic and others, or to be witness for God’s will. The analysis here does not dare and does not need to delve into the lacuna of these tricky, controversial and fundamental issues. The limited argument here points just at the tension between the radical Marian message of Fatima and the moderate wording of papal addresses. As the tension is overall stable during various pontificates, it cannot be explained by the particular and personal attitude of the popes alone. The analysis has to take the institutional, public and political settings of the papacy into account. Due to the eminent political implications of the message which have been used from the beginning of the apparitions to criticize and legitimize political power (Bennett 2012), the integration of the phenomenon into the political and public spheres seems adequate. However, that does not reduce the phenomenon to an issue of power politics. The political and diplomatic aspect, which is analyzed here, is just one part of the puzzle.

The study is based on a quantitative analysis of all documents related to the Fatima visits of each pontificate as presented by the homepage of the Holy See (www.vatican.va, accessed on 13 May 2021). Voyant tools is used to indicate and present the most uttered relevant terms of each pontificate’s Fatima visit file. As will be presented in the next section, the result indicates that the papal discourse does not echo urgently the critical, radical and demanding messages of Fatima, or more precise: while all popes spoke about God and the world, the terms of sin, penitence and conversion do not appear among the most uttered terms. While the journeys show the willingness of the popes to keep the mass mobilization going, their moderate addresses indicate that they are satisfied with a tamed mobilization. To tame a mobilization means here to curb and calm down a movement not with the aim of stopping it but with the aim of mastering and controlling it. The Marian masses should be mobilized not in an all-out attempt to call for the conversion of the world, but as a public mass manifestation of Marian devotion controlled by the popes. The popes were able to channel the power of a tamed mobilization to invite those open to a Marian piety but not to offend those who are not. It seems that the popes after the Second Vatican Council, even those such as John Paul II with a strong personal Marian devotion, were not ready to embark again on an intransigent course against the modern world but preferred a diplomatic way to engage with public and politics. The Virgin of Fatima, instead, urged in dramatical gesture to a return to God.

2. Results: The Modesty of Papal Addresses during the Journeys to Fatima

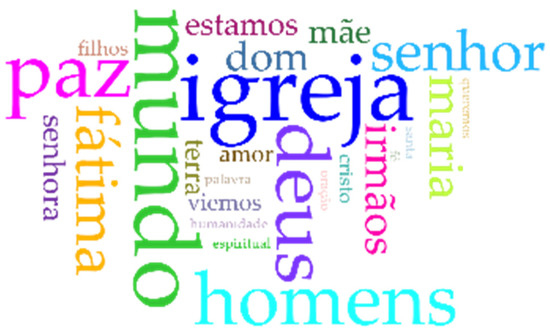

The analysis of all documents related to the papal trips to Fatima between 1967 and 2017 (Paul VI in 1967, John Paul II in 1982, 1991 and 2000, Benedict XVI in 2010, Francis in 2017) shows, as Figure 1 indicates, that foremost “God” (deus 333) and then on rank two “Church” (igreja 225) are the dominant terms, while “Mother” (mãe 194), “Christ” (cristo 176), “World” (mundo 158), “Heart” (curação 145), “Life” (vida 142), “Fatima” (fátima 134), “Love” (amor 128), “Mary” (maria 127), “Jesus” (jesus 120), “Lord” (senhor 117) and “brothers” (irmãos 106) were also significant. What the graphics does not display clearly is the importance of the terms related to “human/humanity” (homens, homem, humanidade 245). Together they are more often uttered than “Church”, only “God” is mentioned more frequently.

Figure 1.

Most relevant terms of all papal addresses on trips to Fatima (Voyant tools).

Following the results shown in Figure 1, it is fair to say that the popes stress in their discourses the relation of “God” and “World/Humanity” which is embodied in the “Church”. In line with the basic teaching of Catholicism, the popes preach that the Lord Jesus Christ, Mother Mary and the love of the heart are instrumental for this relationship that should dominate the life of the brothers and sisters in Christ gathered in Fatima. Often uttered world such as “Faith” and “Hope”, “Prayer”, “Peace” and “Light” fit in the general picture of a basic Catholic catechism, including additional terms for God or Mary. Apart from the term “Fatima”, at a first glance, nothing specific about Fatima seems to dominate the papal discourse. However, adding some qualitative insights to the quantitative analysis, the term “Heart” is linked in more than half of the cases to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, which plays a prominent role in the Fatima messages. That does, however, not change the overall picture: The popes come to Fatima and they speak about Fatima and the messages of Our Lady of Fatima, but they do not put the Fatima messages in the center of their addresses in and around Fatima. The popes do not press the urgent messages of Fatima in order to move the masses. The popes do not promote a special Fatima discourse that concentrates on specific terms such as “penitence”, “souls”, “sacrifices”, “sin”, “conversion”, “rosary”, but stick to the basic Catholic discourse that the popes promote in general. As such, through their moderate addresses, the popes tame the mobilization. This overall result is confirmed by taking a closer look at the four pontificates. While each pope, as we will see below, has his special vocabulary and preferences, the papal discourses do not differ much. Any specific Fatima related urgency or radical wording does not appear and is not part of the moderate papal discourse. In short, the popes tell only half of the story and attenuate the controversial, urgent and radical part of Fatima, thereby taming mobilization.

2.1. The Addresses of Paul VI

Paul VI visited Fatima in 1967. Portugal saw the last period of the authoritarian rule of António de Oliveira Salazar, a devout Catholic who integrated Fatima in the legitimization of his Stato Novo (Bennett 2012). After the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), the pope was not interested in coming too close to Salazar’s anti-communist ideology and his colonial wars. Peace was thus the most political issue that dominated the papal addresses during his Fatima and Portugal visit (Simpson 2008).

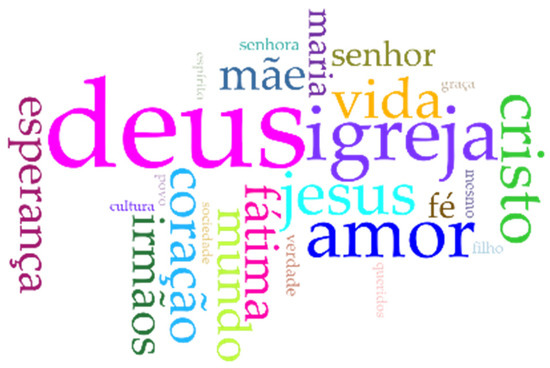

The most frequently uttered words of his addresses were the following: “Church” (igreja 28), “World” (mundo 22), “Peace” (paz 19), “God” (deus 18), “Men” (homens 17), “Fatima” (Fátima 15), “Lord” (senhor 14).

As Figure 2 indicates, “Church” and “World” were the key terms that had to be brought into a relationship in order to foster “Peace”. Fatima was also mentioned and the Virgin Mary was addressed in so many different terms that none of them made it into the seven most often uttered words. Nevertheless, the Fatima message was only implicitly present in the prominent term “Peace”. A story of God and Christ, the Lord, with men had to be told. The key terms of the apparition, however, such as “sin”, “penitence”, “rosary”, not to speak of “Russia”, had not become a mantra of the pope. The force of the apparition and its message had to be checked and tamed in order to work for the papacy and its peace agenda. Paul VI thereby established the diplomatic approach to a tamed mobilization of the Marian masses.

Figure 2.

Most relevant terms of the addresses of Paul VI on trips to Fatima (Voyant tools).

The corpus analyzed by Voyant tools includes all speeches and sermons delivered by the pope during his visit in Fatima and Portugal as provided by the homepage of the Holy See. Two speeches delivered in French were translated into Portuguese by Deep L.

Paul VI was the pope who initiated a new Ostpolitik towards Moscow after his predecessor John XXIII paved the way for such a realignment during the Cuban missile crisis. Portugal’s staunch anticommunist support was no longer as welcome as it had been before. Right-wing regimes in Catholic majority states, in contrast, came increasingly under the pressure of what has later been dubbed the third or Catholic wave of democratization (Huntington 1991; Troy 2009). Both circumstances made a radical mobilization in accordance with the message of the apparition unlikely. Nevertheless, Paul VI, who reestablished international papal travelling and turned it into a major tool for papal appearance and global visibility, did not spare himself the Marian site. Obviously, his idea of a global papal pilgrimage could not work without a visit to a Marian shrine. Instead of Lourdes, he chose the much more politicized shrine of Fatima. Fatima was his fourth journey and it took place two years after his speech at the UN assembly in New York. In the year of his Fatima trip, Paul VI visited also Turkey, where he made also a pilgrimage to Ephesus, which is associated with the earthly life of Mary. During his visit in Fatima, Sr. Lucia, the surviving seer child, now 60 years old, met him in public. The pope was, however, eager not to establish a too close contact to her. The impression that she revealed any messages to him had to be avoided at any costs. The pope sought the backing of the Marian masses but their mobilization had to be tamed in order to support him in his role on the diplomatic parquet. Due to Fatima’s radical message a full mobilization could have endangered the papal standing within a secular and enlightened world. Marian apparition and mass mobilization were welcomed but they were adapted to the papal political outreach and as such steered, controlled and for that purpose, tamed.

2.2. The Addresses of John Paul II

John Paul II visited Fatima and Portugal three times, in 1982, 1991 and 2000. His Marian piety and his anti-communism were beyond dispute. However, Fatima was initially not a prominent link of these two aspects for him. He went first to the popular Mexican shrine of the Virgen de Guadelupe and toured his fatherland Poland, including its Marian shrines. He managed to contain the Marxist version of Latin America’s liberation theology and supported the free and Catholic labor union in its struggle against the Communist Polish State without an initial link to Fatima. The attempt on his life in 1981 added a Fatima layer to his Marian piety but that did not turn into a more radical Marianist political approach. Even though he was an outspoken critic of communism and he was not shy in cooperating with the Reagan administration, which established full diplomatic relations with the Holy See during this period (Wanner 2020). He was also a staunch critic of what he called the culture of death, which he associated with liberal abortion and euthanasia laws and the consumer culture of capitalism in general. However, these political and moral views did not merge into a radical discourse in line with the message of Fatima.

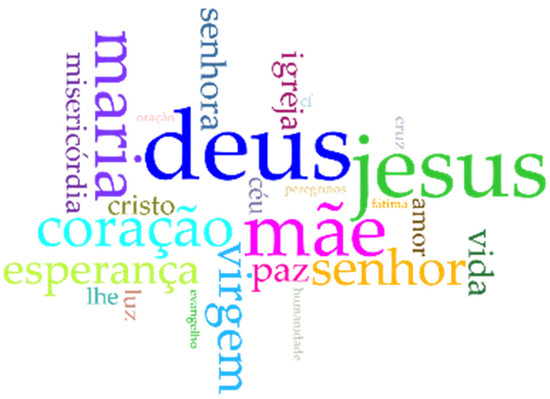

The message of John Paul II during his three trips to Fatima and Portugal was brought forward by the following words (See Figure 3): “God” (deus 216), “Church” (igreja 164), “Christ” (cristo 144), “Mother” (mãe 140), “Life” (vida 120), “World” (mundo 119), “Men” (homem 112).

Figure 3.

Most relevant terms of the addresses of John Paul II on trips to Fatima (Voyant tools).

Comparing these terms with the results of the analysis of the speeches of Paul VI one can detect some changes, but not a transformation of the strategy. “Peace” was replaced as the most important buzzword by “Life”, a key term of John Paul II’s pontificate which expressed a more militant attitude as life should be protected (“culture of life” in contrast to “culture of death”) and the whole life should be committed to God. The religious terms “God”, “Church”, “Christ”, in addition, came in focus, while “world” and “men” fell behind.

As in the case of Paul VI, integrated in the corpus analyzed by Voyant tools were all documents provided by the homepage of the Holy See as part of the journeys. A letter to the Bishops of Portugal in Italian and short greetings to German, English, French, Spanish and Polish speaking pilgrims have been translated by Deep L into Portuguese. Limiting the content analysis to only those documents which were presented in Fatima itself does not change the picture. The visit in the Holy Year 2000 was a short one dedicated to the beatification of the seer children Jacinta and Francisco. The content of this visit’s four rather brief addresses differs from the other ones. “Jacinta” (12), “Francisco” (12) and “Fatima” (16) were the most uttered words, only surpassed by “God” (deus 17).

The exemption of 2000 shows that a concentration on the Fatima story was possible but not chosen. Instead, John Paul II opted for the more general message of bringing the religious terms “God”, “Church”, “Christ” and “Mother”, which refers to Mary, Mother of God, in relation to the world of human life represented by “Life”, “World” and “Men”. As in the case of Paul VI, the terms “Sin”, “Penitence” or “Repentance”, “Hell”, “Rosary”, “Russia” did not play a quantitative role.

This is particularly telling for the thesis that the popes opted for a tamed mobilization and a diplomatic approach as the visits of 1982 and 1991 had a very dramatic background. Pope John Paul II came to Fatima to give thanks to the Virgin Mary who had, according to his faithful statements, protected him from an assassination attempt on his life. On 13 May 1981, the feast day of Fatima, the hired killer Ali Agca shot the pope from close range during a papal audience at St. Peter’s Square. The pope survived seriously injured. While men and motives behind the attack could not been identified, the so-called Bulgarian connection hinted at the KGB and the Soviet Union. It is likely that the Polish pope, whose visit to his fatherland in 1979 sent shock waves through the communist orbit and who continued to support Solidarity, the free and anti-communist and labor movement in Poland, should be eliminated. John Paul II never gave any indication of who he believed was behind the attack. However, he made clear who he thought had protected him by bringing one of the bullets to Fatima, where it was integrated in the crown of the statue of the Virgin Mary. In addition, John Paul II was a dedicated Marian pope who followed the spiritual advice of Louis-Marie Grignion de Montfort (Grignion de Montfort 1988) concerning the total consecration to Jesus in Mary to such an extent that he integrated an M for Mary into his papal coat of arms and made Grignion’s motto “Totus Tuus” (totally yours) his own. This pope was also so determined to consecrate Russia precisely in the way the apparition asked for that he did it twice. The surviving seer Sr. Lucia was pleased. However, as the German theologian Manfred Hauke showed in a detailed study, John Paul II was likewise determined to do this in the most diplomatic way possible as to not offend Russia publicly. He never uttered the word “Russia” during the consecration ritual in public (Hauke 2017). Even a pope so dedicated to Marian piety in general and the message of Fatima in particular was not willing to radicalize the masses. A tamed mobilization was understood much more in line with the diplomatic interests of the Vatican than an all-out-campaign of mobilizing the masses in line with the controversial message of the Fatima apparition.

2.3. The Addresses of Benedict XVI

As the prefect of the Congregation of the Faith, Joseph Ratzinger was involved in the publication of the third secret in 2000 (Ratzinger 2000). He provided the interpretation that accompanied the publication. Known for his rational approach to faith, he supported the authenticity of the experience of the seers but stressed also the symbolic nature of their visions. His sober approach meant that, despite his reputation as a conservative critic of what he called the “dictatorship of relativism” and his personal Bavarian Marian piety, he was also as Pope Benedict XVI not likely to return to an anti-modernist interpretation of the Fatima message. Nevertheless, in 2010, on the occasion of the anniversary of the beatification of the Shepherd Children of Fatima, he visited the shrine and stressed that Fatima is not a remnant of the past but still a sign for the future. His addresses, however, stayed within the established moderate papal discourse. “God” was the most important term by far (deus 91), “Church” (igreja 55) followed. “Love” (amor 44), “Christ” (Cristo 42), “Jesus” (Jesus 39), “Life” (Vida 36), “Heart” (coração 33), “Fatima” (Fátima 32), “Brothers” (irmãos 30), “Hope” (esperança 29) and “World” (Mundo 29) were also important.

As Figure 4 shows, there were some changes in comparison to the previous popes. “God” became even more prominent. “Love” became the most important buzzword before “Life”, “Heart” and “Hope”. As the term “World” ranked lower, one could argue that the discourse became a bit more pious and church-oriented. On the other hand, the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, became less prominent. Overall, however, the papal discourse showed no major innovations and the key words of the Fatima message do also in the addresses of Benedict XVI not appear on the radar.

Figure 4.

Most relevant terms of the addresses of Benedict XVI on his trip to Fatima (Voyant tools).

The pope, who has been dubbed by the yellow press as “God’s Rottweiler” for his arguably uncompromising conservative views, did not use the opportunity in Fatima to express an intransigent position towards the sins of a steadily secularizing modern world. Already as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Ratzinger preferred to act as a public intellectual who discusses his faith with agnostics. An example for this is his debate with Jürgen Habermas shortly before he became Pope Benedict XVI (Habermas et al. 2006). As pope, he chose the title “Caritas in veritate” (Benedict XVI 2009) for his first encyclical, but in Fatima he spoke more often about love than truth. In addition, for Benedict XVI, Fatima was not the place to make an effort to persuade public and politics to act in the urgent way of conversion and penitence as the message of Fatima demands it. His Regensburg Speech (Benedict XVI 2006), which included a quote of a Byzantine emperor arguably insulting the Prophet Muhammed, provoked public unrest and murder in some places of the world. This provocation was obviously an inadvertence. Benedict XVI was, as much as his predecessors, very careful not to be too provocative. His Fatima visit could have offered the opportunity to stress the coming chastisement if people do not convert to God. Instead of preaching about hell, he talked about “Love”, “Heart” and “Hope”. The urgency of the Fatima messages was not replicated and as such, not supported nor enforced. Again, a pope preferred to tame the mobilization of the Marian pilgrims that gathered in Fatima instead of leading them into a crusade against the modern world. In short, the popes use the masses to support the papal status in public, but not to form a rosary army fighting a spiritual holy war of penitence against the errors and sins of the world.

2.4. The Addresses of Francis

Pope Francis is seen by many as a global pope who distances himself from the traditional legacy of European Catholicism (Faggioli 2020; Franco 2013). From the very beginning of his pontificate, he positioned himself as a staunch critic of capitalism. Thus, it is certainly not a surprise that he did not push forward the anticommunist interpretation of Fatima. However, early on, in October 2013, he repeated the consecration of the world to the Immaculate Heart of the Virgin Mary and put his pontificate under the protection of the Virgin Mary. A Fatima Madonna was brought to the St. Peter’s Square where the act of consecration took place. The sermon the pope delivered is the best example of how the popes mobilize masses with their relations to Fatima while presenting an alternative story of Marian piety at this occasion. Instead of preaching anything about Fatima, Pope Francis used the gathering to promote mercy and the trust in God (Francis 2013).

His visit to Fatima in 2017 was short. It celebrated the centenary of the apparitions and Pope Francis canonized the seer children Jacinta and Francisco. In contrast to John Paul II’s short visit in 2000 in order to beatify the two children, no special focus on them could have been detected. The usual papal discourse prevailed. “God” (deus 44) is again the most important term by far. “Jesus” (Jesus 30), “Mary” (Maria 23), “Mother” (mãe 23), “Heart” (coração 22), “Virgin” 19 (virgem), “Lord” (senhor 18), “Hope” (esperança 17), “Peace” (paz 15), Church (igreja 14) followed.

As Figure 5 shows, again we can see a slight change in the list of priorities. The Marian terms became again a slightly more prominent. ”God” and the “Lord Jesu” still dominate. “Church” but also the “World” became less important. “Heart”, “Hope” and, returning to the initial top rank, “Peace” are the buzzwords to deliver the papal message. New among the second ranking buzzwords such as “Light” (luz), “Life” (vida) and “Love” (amor) is “Mercy” (misericordia) which was a prominent term of the pontificate particularly in the extraordinary Holy Year which Pope Francis celebrated in 2015/2016 as a Jubilee of Mercy. This is the only term that Francis introduced to the papal Fatima discourse as his specific contribution. Apart from that, Francis, too, kept to the established papal discourse. The canonization and the centenary mobilized huge masses but again the pope preferred to tame the mobilization instead of hammering home the Fatima message’s urgency of penitence and conversion. Pope Francis stayed in line with his predecessors. Rumors that the XXXVII. World Youth Day would take place in Fatima did not materialize as Lisbon was chosen as the site of the feast that had to be postponed due to the corona crisis to 2023. The pope announced, however, that he will return to Fatima when he visits Portugal for that occasion. Thus, the papal mobilization of the masses of Fatima is most likely to be continued. Simultaneously, the message of Fatima might again be attenuated in order to support the moderate papal, instead of Fatima’s radical message.

Figure 5.

Most relevant terms of the addresses of Francis on his trip to Fatima (Voyant tools).

3. Discussion: “Penitence, Penitence, Penitence” or Why So Moderate?

The findings of the quantitative analysis of the papal documents issued during the trips of the popes to Fatima indicated a modest Catholic discourse. This papal modesty is striking as the message of Fatima is anything but modest. Sister Lucia remembered as part of the third secret, revealed during the apparition in July, an angel repeating three times the word “penitence” to avoid the persecution of the Church (Ratzinger 2000). As it has been briefly sketched in the introduction, the message of Fatima is one of penitence and conversion. The message of the Fatima is not a call to find some new gems in old religious semantics which can be translated into secular discourses to foster human flourishing, such as for instance the debate about a post-secular society (Habermas et al. 2006). The message warns of war, hell, the errors of Russia and a coming divine chastisement if the people do not stop offending God. The message is a strong call to accept God as the ultimate ruler, also for publics and politics. It calls for nothing else than the end of secular modernity and the public return to Catholicism.

The popes are still interested in mobilizing masses for the Catholic creed and the public and political status of the papacy in general and the Holy See in particular. That is why they come to Fatima. However, they tend to attenuate the messages and tame mobilization as they seem to prefer to avoid a return to the intransigent position of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century and opt for a diplomatic approach to secular public and politics instead.

3.1. The Message of Fatima

In 1917 the most important Marian apparition of the 20th century happed in Fatima, Portugal. In a sequence of monthly occasions, three shepherd children of a small village, Lucia, Jacinta and Francisco, encountered the Virgin Mary who entrusted several messages to them. While the children experienced resistance from their parents, and in particular from the state authority, who even had them imprisoned for a short period, masses were soon be fascinated by the claim. At October 13, a particularly vast crowd gathered on the open field of the apparition sites as the children had announced that the Virgin Mary would perform a miracle visible to all. The so-called Miracle of the Sun impressed the crowd, including those who gathered in order to observe the end of this swindle. Fatima soon became famous. However, it became also a hotly contested political issue as Portugal was reigned by a laicist government that tried to reduce the influence of the Church on public and politics. The initial Fatima shrine was destroyed by freemasons twice during this conflict. Fatima played a significant part in the end of these controversies and the establishment of an authoritarian rule leaning on Catholicism (Bennett 2012). After a decade-long review process, during which two of the three children died, while the oldest one, Lucia, became a nun, the bishop, backed by the pope, acknowledged the apparition in 1930 as authentic. During this time, the messages of Fatima were known for their call to return to God, penitence and rosary prayer, very much in line with the call from Lourdes, the major site of a Marian apparition in the 19th century, which set the course for how to interpret the apparitions and perform the pilgrimage. In the context of Beauraing, a Belgian site of Marian apparition, a bishop summarized those messages with “conversion and penitence, prayer and Jesus-Eucharist” and Pius XII declared in 1942: “to do penance, to change one’s life and flee sin, the principal cause of the great chastisements with which eternal justice pains the world (both quoted in Van Osselaer 2020, p. 144). Similar to as in Lourdes, the primary opponents in Fatima were firstly the liberal, laicist and secular state and its struggle against God and church. However, not all messages from 1917 were revealed, three secrets were kept private by Lucia who became a Carmelite nun and continued to have revelations. Backed by Pope Pius XII, two of these secrets were published during World War II in 1941. The first secret was about a vision of hell and the many souls who go there because of their sins and because there is not enough penitence and prayers for them; the second secret was about the threat of a major war, if people do not convert and the call to consecrate Russia to the Immaculate Heart of the Virgin Mary as a remedy. Pius XII consecrated the world to the Immaculate Heart of Mary in 1942. While some attribute to this consecration the turning points of the Second World War, El Alamein and Stalingrad (Höcht 1957), the lack of an explicit mention of Russia, Pius XII mentioned it indirectly but clearly (Pius XII 1942), raised questions about the fulfillment. Around the proper performance of that consecration expanded a controversy that led to several but still contested papal consecrations of the world, the latest by Pope Francis in 2013, while John Paul II’s consecration of 1984 is known as accepted by the seer Lucia as valid. Since the revelation of the secrets, anti-communism and for the time of the World War II also the resistance against National Socialism, became the primary context in which Fatima was integrated. The third secret that had not been published by Paul John XXIII after he read it in 1960 as asked by Lucia, caused many rumors about an apocalyptical event, including a nuclear war which was anticipated as the major threat during the Cold War (Margry 2020). In 2000, during the pontificate of John Paul II, the secret was published by the Vatican, accompanied by an interpretation of the then head of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith and later Pope Benedict XVI, which had been mentioned above already (Ratzinger 2000). The vision shows a man in white, obviously the pope, murdered at a hill in midst of a destroyed city and a group of other martyrs. John Paul II survived in 1981 an attempt on his life on May 13, which is the Fatima Day in the Liturgical Calendar of the Catholic Church. He ordered the Fatima files already when he was recovering in the hospital, sent the bullet to Fatima and visited Fatima in 1982, in order to thank the Virgin Mary for her protection. While the vision is seen by the interpretation as an image of the whole martyrdom of Christians during the 20th century, John Paul II is understood by some as the man in white, saved by his devotion to the Virgin Mary and the rosary prayers and penitence provided by the faithful. John Paul II insisted in 1984 in an interview that the visions of the secrets are not images of a determined future but warnings of what will come if people do not convert. The avoidance of a nuclear war and the sudden decline of Communism in Europe after 1989 lead to a controversy if the return of Russia, as promised in Fatima by the Virgin Mary, had been happened. When Benedict XVI visited Fatima in 2010, he stated the view that Fatima has not been fulfilled yet.

Given the prominence of the discourse around the apocalyptical visions of the three secrets, the importance given to Russia and communism, the urgency of conversion, penitence, sin, rosary, hell, war and martyrdom, a much more radical discourse could have been developed by the popes. Indeed, the 19th century and early 20th century papal discourse on secular modernity was much more radical and not shy of using strong words and condemnations. That changed with the aggiornamento of the Second Vatican Council, the modernization of the Church. The moderate speeches of the papal pilgrims in Fatima reflected the new diplomatic approach that was already evolving since Benedict XV’s pontificate during which the Fatima apparition occurred. Pius XII’s pontificate marked a watershed insofar as he performed the consecration in a diplomatic mode that sought not to offend the Anti-Hitler-Alliance in which Soviet Russia played a major part alongside the Western powers, with which he already cooperated during the war in order to bring an end of fascist rule in Italy and Europe. After the war, Pius XII sided openly with the liberal West and promoted Christian democrats in Italy and Europe, including the European integration project spearheaded by Catholics such as Robert Schuman, Alcide de Gasperi and Konrad Adenauer, also in order to prevent communists from gaining power in Italy and elsewhere in Europe. Thus, the anti-liberal, anti-secular part of the Fatima message was an obstacle for papal diplomacy. Particularly after the peace notes of John XXIII during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Pacem in Terra encyclical and the new Ostpolitik of Paul VI towards the Soviet Union and its Central and Eastern European orbit, an apocalyptical campaign against communism lost its place within in the papal discourse. Even John Paul II changed the strategy not entirely. As mentioned above, Manfred Hauke shows in his detailed study how the devote Marian pope was eager to perform the consecration as demanded by the Virgin Mary but without uttering the word “Russia” in public (Hauke 2017). After all, popes are also diplomats and politicians whose role determines them to put their pious belief second to the risk of eroding the status of the Holy See in international relations and the reputation of the Church within public opinion. Given the acknowledged impact of John Paul II in the decline and end of communist rule in Europe, the diplomatic strategy of a tamed mobilization seemed to be successful. In their specific ways, his successors, Benedict XVI and Francis did not change the overall diplomatic approach of a tamed mobilization.

The diplomatic explanation presented here is certainly not the only possible way to understand the tension between the radical discourse of the message of Fatima and the moderate papal discourse at the shrine in Fatima. The personal attitude of the popes towards Marian piety in general and Marian apparitions and Fatima in particular varied. A deeper analysis of the different personal approaches and backgrounds of the popes would be a very rich and fruitful field for research. Another important perspective could be a more qualitative analysis of the papal speeches in Fatima on their specific discourse of values and ethics and how the pope tried to influence public and political attitudes of pilgrims.

The limited aim here is to focus on the tension between the message of Fatima and the papal addresses at Fatima. Instead of supporting and enforcing the messages of Fatima, the popes seem to have opted for a tamed mobilization understood as an attempt to control but not to stop mobilization due to diplomatic concerns and in order to avoid a return to the previous papal intransigent stance towards secular modernity.

3.2. The Marian Pilgrims

An explanation of the modest papal addresses as an exercise in taming mobilization due to diplomatic concerns has to take not only the messages but also the pilgrim masses into account. Would these pilgrims be open to a papal discourse more in tune with the radicalness of the Fatima message? In short, we do not know, but we know that the popes did not even try, although there is evidence that the Marian pilgrims come to Fatima because they find its message attractive.

Petr Kratochvil (Kratochvil 2021) showed recently that Marian pilgrims still constitute a significant part of the modern world of pilgrimage and that their conservative Catholicism stands in contrast to the other dominant ideal type of spiritual pilgrimage that is often found on the Way of St. James to Santiago de Compostela. In the parlance of Danièle Hervieu-Léger (Hervieu-Léger 2004), the majority of Marian pilgrims can hardly be framed as seekers, while pilgrims on the Way of St. James can. Kratochvil used Turners classical approach for the purpose of his argument. Marian pilgrims gather as masses in order to reinform their established community of Marian devotees. He claims that they do not seek for a liminal experience in order to transcend boundaries and create new communities as spiritual pilgrims do (Kratochvil 2021). Or, in other words, most of them know the messages and might be ready to listen to a pope who preaches them. They do, as Kratochvil argues, not aim at a new experience beyond that creed. As Patrick Heiser showed, also the spiritual pilgrims on their way to Santiago use religious templates for their individual ways of seeking God and community: “Even pilgrims without any strong ties to religious institutions or traditions depend on these religious structures to acquire their agency as pilgrims. They still, and even increasingly, turn to traditional pilgrim routes rather than just going for random hikes in specific biographical situations. In addition, they do usually not invent new religious practices and interpretations along these routes but rather rely on old traditions for their individualistic journeys” (Heiser 2021, p. 11). If even those pilgrims who have no strong ties to the institution depend on the “traditional plots” (Heiser 2021, p. 11), the Marian pilgrims can safely be understood as converts in Danièle Hervieu-Léger’s parlance (Hervieu-Léger 2004). Most of them have at least an idea where they are going to. That does of course not mean that Marian pilgrims in Fatima or elsewhere are a homogenous group. Quite the contrary is the case. Diverse studies on Marian pilgrimages show that very different motivations bring pilgrims to Marian shrines (Hermkens et al. 2009a). Indeed, it is not likely that all of the Marian pilgrims are ready to act in accordance with how the message of Fatima urged them to do. More qualitative but also quantitative research on Marian pilgrims’ motivation and experiences is an important field for future studies as we do not have much empirical data on Marian pilgrims’ views. This lack can be explained by a certain consensus among scholars about Marian pilgrims. Hermken, Jansen and Notermans (Hermkens et al. 2009b, p. 1) note that Marian pilgrimage does not score particularly high in pilgrim studies as those pilgrimages “seem antimodern or resisting modernity” (Hermkens et al. 2009b, p. 2). Of course, these prejudices of researches cannot be taken as a proof for the attitude of all Marian pilgrims. However, scholars such as Charlene Spretnak (2004) or Robert A. Orsi (2009) and also several more recent studies (Di Stefano and Ramón Solans 2018; Margry 2020; Maunder 2018; Zimdars-Swartz 2014) who show a certain spectrum of piety and creed among Marian pilgrims cannot deny that a rift emerged within the Catholic Church after the Second Vatican Council concerning the Virgin Mary. Or in the words of Charlene Spretnak: “Most ‘progressive’ intellectuals in the Church, in fact, tend to consider any glorification of the Nazarene village woman as ‘Queen of Heaven’ to be theologically regressive and even dangerously reactionary—or, at least, in poor taste” (Spretnak 2004, p. 1). As stated above, that does not mean that Marian pilgrims are a homogenic group of conservatives in a political or religious sense—for instance being nostalgic about the Salazar regime and a more traditional Church. However, it is more likely, that Marian pilgrims were indeed influenced by a Marian discourse that takes the radical message of Fatima seriously. At least, during the decades of papal visits to Fatima, a bulk of literature emerged that was ready to present the radical message of Fatima and its public and political implications, including the role of the popes (Tindal-Robertson 1992; Petrisko 2002).

Thus, the pilgrims are arguably not the reason for the popes to speak so gently. At least, the popes seem to shy back from the opportunity to create a liminality in the sense of Turner between them and the pilgrims that could break with a secular public. They do not use the opportunity of the Fatima message to create a liminal experience based on the radical call of urgent conversion and penitence. Of course, such an attempt could fail, such as others papal calls for action—from welcoming foreigners to fighting abortion. However, that does not explain why the popes did not try. One reason that could explain the puzzle is the diplomatic consideration of the popes concerning the reaction of publics and politics elsewhere to such a radical attempt to challenge the secular frame of modern public and politics.

4. Materials and Methods

To analyze the papal parlance, all the documents of the six papal journeys to Fatima were selected: Paul VI in 1967, John Paul II 1982, 1991 and 2000, Benedict XVI in 2010, and Francis in 2017. The resource for the texts was the homepage of the Vatican where all official documents are provided. While newer documents are usually provided also in an English translation, older documents are often only available in the language, they have been issued or delivered by the pope. For the first visit of Paul VI in 1967 the documents are not available in English. While for this journey and all the others papal trips almost all documents are available in the national language, Portuguese was selected as the language of the quantitative analysis. Some few words uttered in other language by John Paul II and Benedict XVI to greet international pilgrims and two addresses of Paul VI in front of a diplomatic audience, delivered in French, were translated with DeepL. The documents of each pontificate were formatted as a single text corpus in order to compare them. Apart from John Paul II who visited Fatima three times, all popes came so far only once. John Paul II made a short trip to beatify the two seer children Jacinta and Francisco in 2000. This short trip data containing only a few documents mentioned the name of the seer children more often than usual. This is significant, particularly in contrast to Francis who canonized the two children at the centennial of the apparition in 2017 but did not change the overall picture. For that reason, the three journeys of the pontificate of John Paul II formed together one text corpus for the final analysis and comparison with the other pontificates. In the section of the results, the most important words have already been provided for each pontificate together with the visualization of Voyant tools, which was also used to select the most frequently mentioned relevant terms.

As indicated already, the message of Fatima has been discussed at length in the literature. The expected keywords such as conversion, repentance, consecration, hell, war, sin and rosary are well documented in the literature. A specific body of documents and literature that could have been compared directly to the papal documents was not available. Nevertheless, such a quantitative comparison would have been particularly suitable to test the thesis. Further research could reflect on the biographical notes of Lucia or take a selection of the pilgrim’s guide to Fatima. For this study, basically a literature review provided the key words of the Fatima message. To provide at least a limited quantitative sample, the texts of the published secrets (Ratzinger 2000) had been brought together as a contrasting corpus.

To test the validity of the qualitative research about key words with a small quantitative test, the three published secrets were analyzed also with Voyant tools. The published texts of the three secrets are certainly too short to make valid quantitative claims. Nevertheless, they help to highlight the issue and underline the discussion of the literature with some quantitative material.

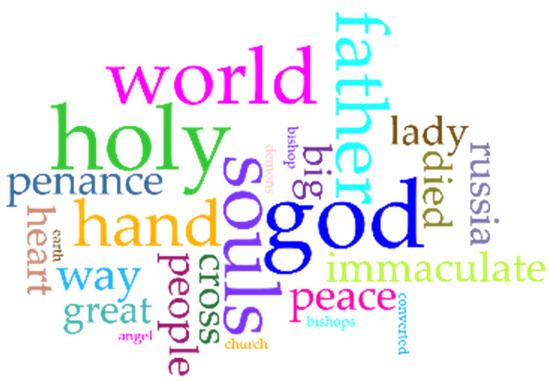

As seen on Figure 6, the result is telling. The most important terms are “God” (6), “Holy” (6), “Father” (5), “Souls” (5), “World” (5), “Hand” (4), [less visible as in singular and plural but together also prominent bishops/bishop 4], “Big” (3), “Cross” (3), “Died” (3), “Great” (3), “Heart” (3), “Immaculate” (3), “Lady” (3), “Peace” (3), “Penance” (3), “People” (3), “Russia” (3), “Way” (3) and among the terms mentioned twice are: “Angel”, “Church”, “Converted”, “Demons”, “End”, “Fear”, “Flames”. Again, as in the papal addresses “God” ranked high, the pope is an issue himself—“Holy Father” -, and the Virgin Mary appears as “Lady”. We read also again the familiar terms “World”, “Heart”, “Peace” and “Church”. However, among these well-known buzzwords suddenly the other discourse emerges: “Penance”, “Russia”, “Died”, “End”, “Fear” and “Flames” rank also high. The popes told only half of the story. The contested issues of the message of Fatima were omitted.

Figure 6.

Most relevant terms of the Secrets of Fatima (Voyant tools).

5. Conclusions

The question is: how do the popes deal with the strong and critical message in relation to the pilgrim masses of Fatima and a wider public and political audience? Do they continue the mobilization efforts of their predecessors in order to convert the world as the Virgin Mary asked? Obviously, the papal visitors are still interested in the mobilization of the masses. However, as a quantitative analysis of the addresses reveals, the popes show a certain moderateness in their words. Instead of insisting on penitence and rosary prayers, they speak more in general terms about God and the world. The return of the world to God is certainly in line with the message of Fatima. However, the popes do not repeat the terms that constitute the radicalness and urgency of the Marian messages to convert. They seem to prefer a tamed mobilization in line with the attenuated role the Virgin Mary has after the Second Vatican Council, as Charlene Spretnak (2004) argued. The analysis, supported by Voyant tools, is focused only on the papal addresses and shows the result of papal modesty, visualized by Voyant tools and following the ideal of parsimony. The discussion section takes these results in the context of the history of Fatima and sets in a qualitative interpretation the papal modesty in Fatima and Portugal since Paul VI in contrast to the messages and their history, including papal involvement. The claim is that since the Second Vatican Council, but already starting with Pius XII, the popes are more interested in a diplomatic approach to public and politics than in a radical confrontation. For that reason, the popes tamed the Marian mobilization. While the discourse of the Fatima messages suggested a strong wording of repentance, sin, conversion, rosary prayer, hell, Russia, war and apocalyptical punishments, the popes kept a modest tone in their addresses.

Funding

This research was funded by German Research Foundation (DFG), grant number 426657443 and 288978882.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the academic editor.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Barbato, Mariano P., ed. 2020. The Pope, the Public, and International Relations. Postsecular Transformations. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Barbato, Mariano. 2021. International relations and the pope. In Handbook on Religion and International Relations. Edited by Jeffrey Haynes. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Barbato, Mariano, and Stefan Heid, eds. 2020. Macht und Mobilisierung. Der politische Aufstieg des Papsttums seit dem Ausgang des 19. Jahrhunderts. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Barbato, Mariano P., Robert Joustra, and Dennis Hoover, eds. 2019. Papal Diplomacy and Social Teaching. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bátora, Jozef, and Nik Hynek. 2014. Fringe Players and the Diplomatic Order. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict XVI. 2006. Apostolic Journey to München, Altötting and Regensburg: Meeting with the Representatives of Science in the Aula Magna of the University of Regensburg. September 12. Vatican (Online). Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2006/september/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20060912_university-regensburg.html (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Benedict XVI. 2009. Caritas in Veritate. June 29. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20090629_caritas-in-veritate.html (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Bennett, Jeffrey S. 2012. When the Sun Danced: Myth, Miracles, and Modernity in Early Twentieth-Century Portugal. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bertone, Tarcisio, and Giuseppe De Carli. 2008. The Last Secret of Fatima: My Conversations with Sister Lucia. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano, Roberto, and Francisco Javier Ramón Solans, eds. 2018. Marian Devotions, Political Mobilization, and Nationalism in Europe and America. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, Eamon. 2014. Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faggioli, Massimo. 2020. The Liminal Papacy of Pope Francis: Moving Toward Global Catholicity. Maryknoll: Orbis. [Google Scholar]

- Francis. 2013. Holy Mass on the Occasion of the Marian Day. Vatican (Online). Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/homilies/2013/documents/papa-francesco_20131013_omelia-giornata-mariana.html (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Franco, Massimo. 2013. The First Global Pope. Survival 55: 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grignion de Montfort, Louis-Marie. 1988. God Alone: The Collected Writings of St. Louis Mary de Montfort. Bay Shore: Montfort Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen, Benedict XVI, and Florian Schuller. 2006. The Dialectics of Secularization: On Reason and Religion. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Ruth. 1999. Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age. London: Allen Lane [u.a.]. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke, Manfred. 2017. Der Heilige Johannes Paul II. Und Fatima. In Fatima—100 Jahre danach: Geschichte, Botschaft, Relevanz. Edited by Manfred Hauke. Regensburg: Verlag Friedrich Pustet, pp. 246–303. [Google Scholar]

- Heiser, Patrick. 2021. Pilgrimage and Religion: Pilgrim Religiosity on the Ways of St. James. Religions 12: 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermkens, Anna-Karina, Willy Jansen, and Catrien Notermans, eds. 2009a. Moved by Mary: The Power of Pilgrimage in the Modern World. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Hermkens, Anna-Karina, Willy Jansen, and Catrien Notermans. 2009b. Introduction: The Power of Marian Pilgrimage. In Moved by Mary: The Power of Pilgrimage in the Modern World. Edited by Anna-Karina Hermkens, Willy Jansen and Catrien Notermans. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu-Léger, Danièle. 2004. Pilger und Konvertiten: Religion in Bewegung. Würzburg: Ergon-Verl. [Google Scholar]

- Höcht, Johannes Maria. 1957. Fatima Und Pius XII. Wiesbaden: Credo Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1991. The Third Wave. Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Suzanne K. 2005. Consuming Visions: Mass Culture and the Lourdes Shrine. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Körner, Hans. 2018. Die Falschen Bilder: Marienerscheinungen im französischen 19. Jahrhundert und ihre Repräsentationen. München: Morisel Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochvil, Petr. 2021. Geopolitics of Catholic Pilgrimage: On the Double Materiality of (Religious) Politics in the Virtual Age. Religions 12: 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. 2010. A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Margry, Peter Jan, ed. 2020. Cold War Mary: Ideologies, Politics, Marian Devotional Culture. Leuven: Leuven University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maunder, Chris. 2018. Our Lady of the Nations Apparitions of Mary in Twentieth-Century Catholic Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, Robert A. 2009. Abundant History: Marian Apparitions as Alternative Modernity. In Moved by Mary: The Power of Pilgrimage in the Modern World. Edited by Anna-Karina Hermkens, Willy Jansen and Catrien Notermans. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 215–25. [Google Scholar]

- Petrisko, Thomas W. 2002. The Fatima Prophecies. At the Doorsteps of the World. McKees Rocks: St. Andrew’s Production. [Google Scholar]

- Pius XII. 1942. Radiomessaggio di Sua Santità Pio XII. Preghiera per la consacrazione della Chiese e del genere umano al Cuore Immacolato di Maria. Sabato, 31 ottobre 1942. (Vatican online). Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xii/it/speeches/1942/documents/hf_p-xii_spe_19421224_radiomessage-christmas.html (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Pollard, John. 2014. The Papacy in the Age of Totalitarianism. 1914–1958. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ratzinger, Jospeh. 2000. The Message of Fatima. Vatican (Online). Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20000626_message-fatima_en.html (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- Rooney, Francis. 2013. The Global Vatican. Lanham: Rowman & Little Field. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Duncan. 2008. The Catholic Church and the Portuguese Dictatorial Regime: The Case of Paul VI’s Visit to Fátima. Lusitania Sacra 19–20: 329–78. [Google Scholar]

- Spretnak, Charlene. 2004. Missing Mary. The Queen of Heaven and her Re-Emergence in the Modern Church. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tindal-Robertson, Timothy. 1992. Fatima. Russia & John Paul II. Herefordshire: Fowler Wright Books, The Ravengate Press. [Google Scholar]

- Troy, Jodok. 2009. Catholic waves’ of democratization? Roman Catholicism and its potential for democratization. Democratization 16: 1093–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Osselaer, Tine. 2020. The Changing Face of the Enemy. The Belgian Apparitition Sites in the 1940s. In Cold war Mary: Ideologies, Politics, Marian Devotional Culture, KADOC Studies on Religion, Culture and Society. Edited by Peter Jan Margry. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 135–52. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, William Thomas. 1990. Our Lady of Fátima. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Wanner, Tassilo. 2020. Holy Alliance? The Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between the United States and the Holy See. In The Pope, the Public, and International Relations: Postsecular Transformations, Culture and Religion in International Relations. Edited by Mariano P. Barbato. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 171–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zimdars-Swartz, Sandra L. 2014. Encountering Mary: From La Salette to Medjugorje. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).