Rites of Initiation in the Early Irish Church: The Evidence of the High Crosses

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Iconography of Initiation

2.1. The Rite of Baptism

2.1.1. Iconography of The Baptism of Christ (Matthew 3:13–17; Mark 1:10–11; Luke 3:21–22)

no water [was] to be found in that spot… the saint turned aside to the nearest rock, where he knelt and prayed a little while. When he stood up, he blessed the face of the rock, and at once water bubbled out from it…

God, you who made Adam from the mud of the land, and when that man sinned in paradise, you did not consider that a sin of death, but you saw fit to restore him in sanctity through your own blood, and you will restore glorious Jerusalem.

(deus, qui adam de limo terrae fecisti, et ille in paradiso peccauit, et illum peccatum mortis non reputasti, sed per per sanguinem unigeniti tui recuperare digneris et in sancta, hirusalem glorientem reducis).Warren 1881, p. 207; trans.: Author

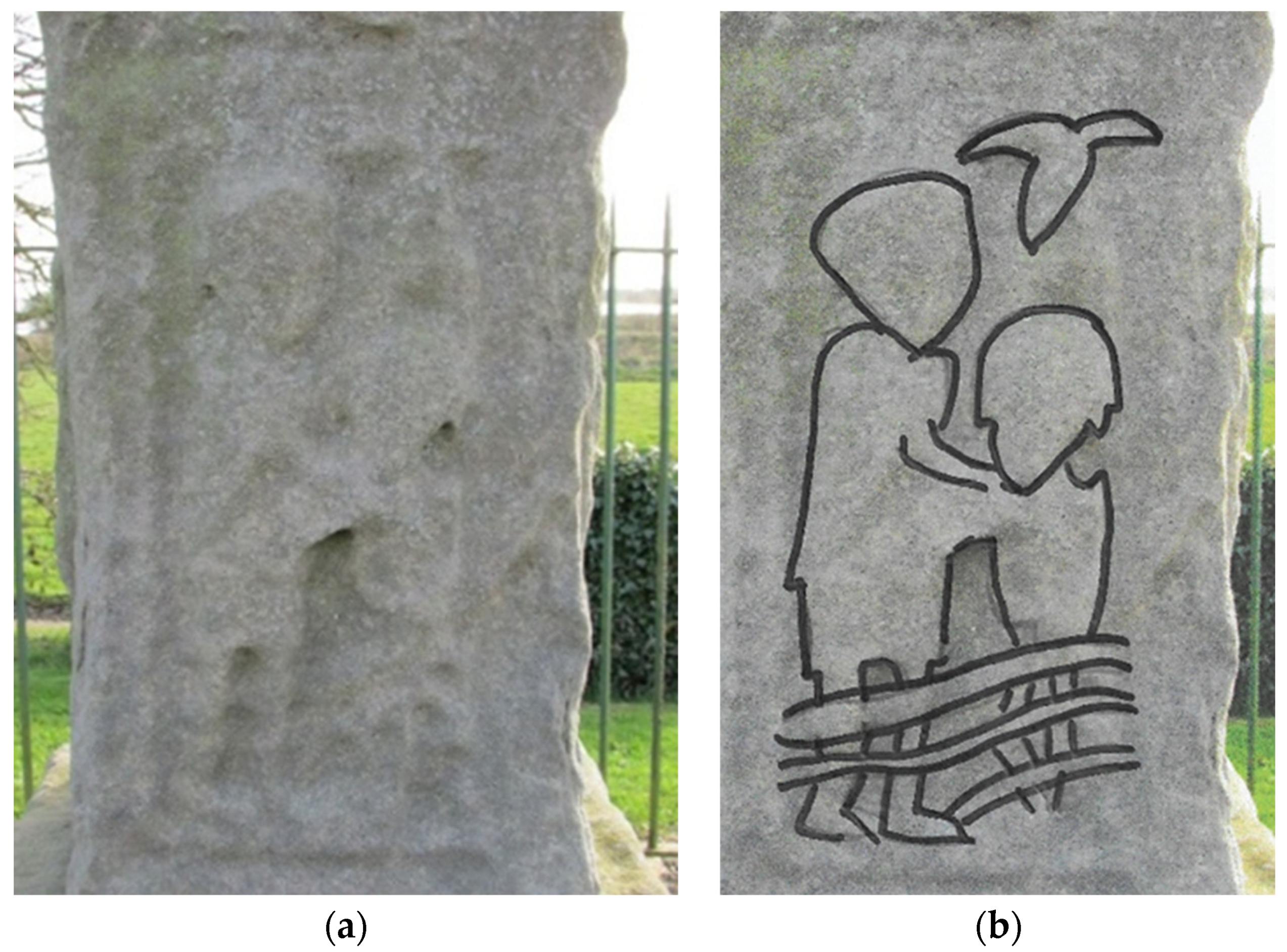

2.1.2. Iconography of Noah’s Ark (Genesis 8:1–11)

the dove, which carried the branch of the olive tree after the flood through the open window into the ark, that when the Lord was baptized in the Jordan the heavens were opened and the Holy Spirit descended in the form of a dove upon him.

It thus enabled the scene to be understood as a typological baptismal rebirth that included those in the ark: the faithful (Norberg 1982, pp. 914–17 Book XI, Letter 28).(Potest in columba, quae aperta post diluvium fenestra ramum olivae intulit in arcam, etiam hoc praefiguratum intelligi, quod, baptizato Domino in Jordane, aperti sunt coeli, et descendit Spiritibus sanctus in specie columbae super eum).

For the bough of an olive tree, found outside and brought into the ark in the mouth of the dove, is the type of those who receive baptism indeed outside of the Church, but are fruitful with an abundance of charity and morally upright with pious devotion as if with the greenness of leaves.

Perhaps in fashioning the ark as a contemporary ship those responsible for the depictions on the crosses were indicating that the recent (Viking) invaders of the island presented an opportunity to undertake conversion and baptism. If the olive branch was, as Tertullian put it at a very early date, ‘a token which is held out even among the heathen as a harbinger of peace’ (mundi pacem caelestis irae praeco columba terries adnuntiavit dimissa ex arca et cum olea reversa; Oehler 1853, pp. 627–8; trans. Souter 1919, p. 56), then the inclusion of the dove—a symbol of the Holy Spirit present also at the Baptism—with the olive branch approaching the Viking-type ark/ship is a powerful statement of intent.(Ramus enim olivae foris inventus et ore columbae in arcam illatus typum gerit eorum qui extra Ecclesiam quidem baptisma percipiunt, sed pinguedine charitatis fructuosi, et pia intentione velut foliorum sunt viriditate integri).

2.2. The Rite of Ordination

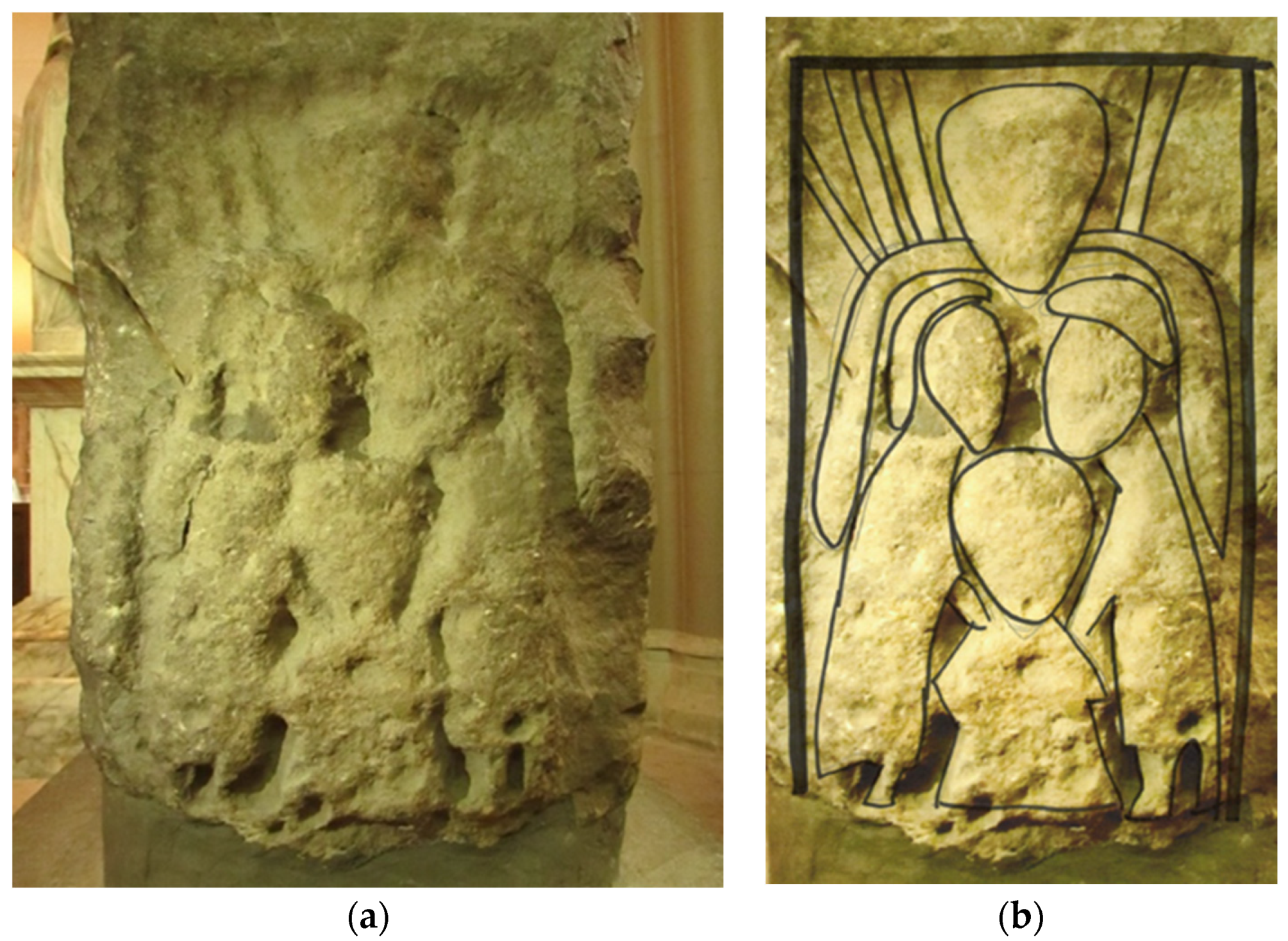

Iconography of The Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace (Daniel 3:19–28)

3. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, Elizabeth. 2018. Visualising the Old Testament in Anglo-Saxon England. Ph.D. thesis, University of York, York, UK. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, Julia. 2018. The Bishop in the Latin West 600–1100. In Celebate and Childless Men in Power: Ruling Eunuchs and Bishops in the Pre-Modern World. Edited by Almut Höfert, Matthew Mesley and Serena Tolino. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, Jesse. D. 2014. The Divine Office in Anglo-Saxon England: 597-c.1000. London: Henry Bradshaw Society. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Sid Arthur Jamesand Bradley. 1982, Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent.

- Bruce-Mitford, Robert. 1970. Ships’ Figure-heads in the Migration Period and Early Middle Ages. Antiquity 44: 146–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnish, Raymond. 1985. The Meaning of Baptism: A Comparison of the Teaching and Practice of the Fourth Century with the Present Day. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, Ruth. 2010. A shelter amid the Flood: Noah’s ark in early Jewish and Christian art. In Noah and His Book(s). Edited by Michael E. Stone, Aryeh Amihay and Vered Hillel. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 277–99. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Bertram Colgrave, and Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors. 1969, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Contessa, Andreina. 2009. Noah’s Ark and the Ark of the Covenant in Spanish and Sephardic Medieval Manuscripts. In Between Judaism and Christianity: Art Historical Essays in Honor of Elisheva (Elisabeth) Revel-Neher. Edited by Katrin Kogman-Appel and Mati Meyer. Leiden: Brill, pp. 171–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cullmann, Oscar. 1950. Baptism in the New Testament, Studies in Biblical Theology. London: SCM Press Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- De Paor, Liam. 1997. Ireland and Early Europe: Essays and Occasional Writings on Art and Culture. Dublin: Four Courts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Roy Deferrari. 1963, Theological and Dogmatic Works, The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press.

- Dods, Rev. 1873. Marcus. The Works of Aurelius Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, Lectures or Tractates on the Gospel According to St. John. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Nancy. 1983. An Early Group of Crosses from the Kingdom of Ossory. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 113: 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- Etchingham, Colmán. 1999. Church Organisation in Ireland A.D. 650 to 1000. Maynooth: Laigin Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, Robert T. 1967. The Unity of Old English Daniel. Review of English Studies 18: 117–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A. W. 1978. The Armagh Cross and Dunluce Castle Ship Representations: Some Problems of Interpretation. Irish Archaeological Research Forum 5: 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Everett. 2009. Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, John Douglas Close. 1965. Christian Initiation: Baptism in the Medieval West. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Flower, Robin. 1954. Irish High Crosses. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institute 17: 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatch, Milton McC. 1975. Noah’s Raven in Genesis A and the Illustrated Old English Hexateuch. Gesta 14: 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart, Heidi C. 2013. Work and Prayer in the Fiery Furnace: The Three Hebrews on the Censer of Reiner in Lille and a Case for Artistic Labor. Studies in Iconography 34: 103–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gefreh, Tasha. 2015. Place, Space and Time: Ion’s Early Medieval High Crosses in the Natural and Litugical Landscape. Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Harbison, Peter. 1992. The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey. Bonn: R. Habelt, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harbison, Peter. 1999. The Golden Age of Irish Art: The Medieval Achievement, 600–1200. New York: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, Jane. 1999. Anglo-Saxon Sculpture: Questions of Context. In Northumbria’s Golden Age. Edited by Jane Hawkes and Susan Mills. Thorpe: Sutton Publishing Ltd., pp. 204–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, Jane. 2003. Sacraments in Stone: The Mysteries of Christ in Anglo-Saxon Sculpture. In The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300–1300. Edited by Martin Carver. Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 351–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, Jane. 2005. Figuring Salvation: An Excursus into the Iconography of the Iona Crosses. In Able Minds and Practised Hands: Scotland’s Early Medieval Sculpture in the 21st Century. Edited by Sally M. Foster and Morag Cross. Leeds: The Society for Medieval Archaeology, pp. 259–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy, William Maunsell, and Bartholomew MacCarthy. 1998. Annála Uladh: Annals of Ulster or otherwise Annala Senait, Annals of Senata chronicle of Irish affairs from A.D. 431 to A.D. 1540. Edited by Nollaig Ó Muraíle. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, First publihsed in 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Françoise. 1930. Les Origines de L’Iconographie Irlandaise. Revue Archéologique 32: 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Françoise. 1967. Irish Art During the Viking Invasions (800–1020 A.D.). London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Henvey, Megan. 2021. Transmitted in Stone: Church Organisation in Early Christian Ireland. In Transmissions and Translations in Medieval Literary and Material Culture. Edited by Megan Henvey, Amanda Doviak and Jane Hawkes. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, Catherine. 1997. Psalms in Stone: Royalty and Spirituality on Irish High Crosses. Ph.D. thesis, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, John. 2015. The Benedicite Canticle in Old English Verse: An Early Runic Witness from Southern Lincolnshire. Anglia 133: 257–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourihane, Colum. 2001. De Camino Ignis: The Iconography of the Three Children in the Fiery Furnace in Ninth-Century Ireland. In From Ireland Coming: Irish Art from the Early Christian To the Late Gothic Period and Its European Context. Edited by Colum Hourihane. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Robin M. 2012. Baptismal Imagery in early Christianity: Ritual, Visual, and Theological Dimensions. Grand Rapids: Baker Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann, Josef A. 1972. The Early Liturgy to the Time of Gregory the Great. London: Darton, Longman & Todd. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Calvin B. 2008. Bede on Genesis. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krapp, George Philip. 1931. The Junius Manuscript, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Record 1. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lezzi, Maria Teresa. 1994. L’arche de Noe en forme de bateau: Naissance d’une tradition iconographique’. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiéval Xe–XII e Siècles XXXVII: 301–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migne, Jacques-Paul. 1850. Patologia Latina, 91: Bedae Venerabilis Opera Omnia. Paris: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Richard. 1991. Baptismal Places 600–800. In People and Places in Northern Europe 500–1600. Edited by Ian Wood and Niels Lund. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer, pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nees, Lawrence. 1983. The colophon drawing int the Book of Mulling: A supposed Irish monastery plan and the tradition of terminal illustration in early medieval manuscripts. Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies 5: 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, Dag, ed. 1982. S. Gregorii Magni: Registrum Epistularum Libri VIII–XIV, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina 140A. Turnholt: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. 1986. Christ over the beasts and the Agnus Dei: Two multivalent panels on the Ruthwell and Bewcastle crosses. In Sources of Anglo-Saxon Culture. Edited by Paul E. Szarmach. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, pp. 377–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. 1987. The Ruthwell Cross and Irish High Crosses: Some Points of Comparison and Contrast. In Ireland and Insular Art: A.D. 500–1200. Edited by Michael Ryan. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, pp. 118–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. 2006. Ruthwell and Iona: The meeting of Saints Paul and Anthony Revisited. In The Modern Traveller to Our Past: A Festschrift in Honour of Ann Hamlin. Edited by Marion Meek. Dublin: DPK, pp. 138–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. 2011. High Crosses, the Sun’s Course, and Local Theologies at Kells and Monasterboice. In Insular and Anglo-Saxon Art and Thought in the Early Medieval Period. Edited by Colum Hourihane. State College: Penn State University. [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin, Thomas. 2000. Celtic Theology: Humanity, World and God in Early Irish Writings. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, Jennifer. 2013. Seeing the Crucified Christ: Image and Meaning in Early Irish Manuscript Art. In Envisioning Christ on the Cross: Ireland and the Early Medieval West. Edited by Juliet Mullins, Jenifer Ní Ghrádaigh and Richard Hawtree. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 52–82. [Google Scholar]

- Oehler, Franciscus, ed. 1853. Tertulliani: Quae Supersunt Omnia. Lipsiae: T. O. Weigel. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, Eric. 2006. Art and Liturgy in the Middle Ages: Survey of Research (1980–2003) and Some Reflections on Method. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 105: 170–84. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by John Henryand Parker. 1857, Seventeen Short Treatises of Saint Augustine. Oxford: Rivington.

- Porter, Arthur Kingsley. 1971. The Crosses and Culture of Ireland. New York: Benjamin Blom. [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy, Phyllis. 2017. Daniel and the Angel’s Embrace: An Insular Innovation? In England, Ireland and the Insular World: Textual and Material Connections in the Early Middle Ages. Edited by Mary Clayton, Alice Jorgensen and Juliet Mullins. Temple: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam, Heather. 2020. Between the Embodied Eye and Living World: Clonmacnoise’s Cross of the Scriptures. The Art Bulletin 102: 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Roger E. 1983. Image and Text: The Liturgy of Clerical Ordination in Early Medieval Art. Gesta 22: 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, Helen M. 1966. The High Crosses of Kells. Rev. ed. Moattown: Meath Archaeological and Historical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, Gertrud. 1971. Iconography of Christian Art Volume I. London: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, Richard. 1983. Some Problems Concerning the Organization of the Church in Early Medieval Ireland. Peritia 3: 230–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Translated and Edited by Richardand Sharpe. 1995, Adomnán of Iona: Life of St Columba. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Souter, Alexander. 1919. Tertullian’s Treatises: Concerning Prayer, Concerning Baptism, Translations of Christian Literature. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Stalley, Roger. 2020. Early Irish Sculpture and the Art of the High Crosses. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, Whitley. 1905. Félire Óengusso Céli Dé: The martyrology of Oengus the Culdee, Henry Bradshaw Society 29. London: Harrison and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Strzygowski, Josef. 1885. Iconographie der Taufe Christi. Munich: Riedel. [Google Scholar]

- Twomey, Carolyn. 2021. Rivers and Rituals: Baptism in the Early English Landscape. In Meanings of Water in Early Medieval England, Studies in the Early Middle Ages. Edited by Carolyn Twomey and Daniel Anlezark. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer, John Walton. 1932. Historical Survey of Holy Week: Its Services and Ceremonial. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Unger, Richard W. 1991. The Art of Medieval Technology: Images of Noah the Shipbuilder. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van den Hout, M. P. J., E. Evans, J. Bauer, R. Vander Plaetse, S. D. Ruegg, M. V. O’Reilly, and C. Beukers. 1969. De Fide Rerum Invisibilium; Enchiridion Ad Laurentium de Fide et Spe et Caritate; De Catechizandis Rudibus; Sermo Ad Catechumenos de Symbolo. Sermo de Disciplina Christiana; De Utilitate Ieiunii; Sermo de Excidio Urbis Romae; De Haeresibus. CCSL 46. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Gerald G. Walsh, and Grace Monahan. 1952, (Augustine). The City of God, Books VIII–XVI. New York: Fathers of the Church, Inc.

- Walton, Ann. 1988. The Three Hebrew Children in the Fiery Furnace: A Study in Christian Iconography. In The Medieval Mediterranean: Cross-Cultural Contacts. St. Cloud: North Star Press of St. Cloud. Inc., pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Frederick Edward. 1881. The Liturgy and Ritual of the Celtic Church. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, E. C., and Maxwell E. Johnson. 2003. Documents of the Baptismal Liturgy, 3rd ed. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Geoffrey Grimshaw. 1994. A History of Early Roman Liturgy to the Death of Pope Gregory the Great. London: Henry Bradshaw Society. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Henvey, M. Rites of Initiation in the Early Irish Church: The Evidence of the High Crosses. Religions 2021, 12, 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050329

Henvey M. Rites of Initiation in the Early Irish Church: The Evidence of the High Crosses. Religions. 2021; 12(5):329. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050329

Chicago/Turabian StyleHenvey, Megan. 2021. "Rites of Initiation in the Early Irish Church: The Evidence of the High Crosses" Religions 12, no. 5: 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050329

APA StyleHenvey, M. (2021). Rites of Initiation in the Early Irish Church: The Evidence of the High Crosses. Religions, 12(5), 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050329