Abstract

Rites of Initiation in early medieval Ireland have been studied only with reference to contemporary texts; recourse to other sources, most notably the substantial corpus of extant high crosses, has not been made. Here it will be demonstrated that the iconography and programmatic arrangement of the depictions of Noah’s Ark, the Baptism of Christ, and the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace can significantly advance theological and liturgical understanding of the early medieval rites of baptism and ordination in this region, indicating the central role of these biblical events and their associated literatures in these contexts. It will be further suggested that this relationship between text, image, and ritual points to the role of the high crosses in facilitating the liturgical rites of the early medieval Irish Church.

1. Introduction

Writing on the rites of initiation in the early Roman Liturgy, G.G. Willis lamented the deficiency of the sources for this subject (Willis 1994, pp. 129–30); the situation is little different in the Insular context. Writers such as Bede (672/3–735) and Adomnán (c. 624–704) recorded certain baptismal events, including the people and places involved, and an Ordo Baptismi is recorded in the late eighth-/early ninth-century Stowe Missal (RIA MS D ii 3; Fisher 1965, pp. 77–87); meanwhile, the rite of ordination is preserved in the mid-eighth century Vespasian Psalter (Cotton MS Vespasian A I) and the hymns in the Antiphonary of Bangor (Milan, Ambrosiana Library, MS C.5. inf; Colgrave and Mynors 1969, II.14, 16; Sharpe 1995, II.10; Warren 1881, pp. 187–89, 207–20; Gearhart 2013, p. 118; Billett 2014, p. 113; Hines 2015, p. 271). Here it will be demonstrated that this shallow pool of textual evidence can be deepened through investigation of the iconography of the mid-eighth to tenth-century Irish high crosses, suggesting a role in liturgical ritual for these monuments, and providing a better understanding of the theology and shape of these liturgies.

The free-standing, stone-carved high crosses found across the island of Ireland have long been understood as forming part of a wider early medieval ecclesiastical landscape, indicating the Christianity and sanctity of the space, but beyond this their role in the ecclesiastical life of the communities within whose bounds they stood has eluded scholars. Ultimately symbols of Christian piety, they may have been commissioned in the development and promotion of a saints’ cult; marked the site of a miracle, death or burial; marked out a pilgrimage route; or been the site of a particular event in the (local) Christian calendar (Stalley 2020, pp. 85–87). Recently, attention has turned to the physical position of the crosses within their communities and their performative relationship to the changing seasons and times of day, convincing arguments which strongly point to the role of the crosses in the enactment of liturgical rituals (Ó Carragáin 2011; Gefreh 2015; Pulliam 2020). Elsewhere I have shown that closer consideration of the carved iconographic schemes facilitates greater engagement with, and understanding of, the nature of the communities that commissioned and made these crosses, and how they used them. Application of this methodology here will further point to the liturgical functions of certain crosses (Henvey 2021).

While the relationships between medieval art generally, and iconography, liturgy and theology have been a burgeoning area of case-study-based research for some four decades, and the early medieval arts of Britain have been considered in this context, the carved programmes of the Irish crosses have not (Ó Carragáin 1986, 1987, 2006; Hawkes 1999, 2003, 2005; Palazzo 2006; O’Reilly 2013). Indeed, at Dewsbury (Yorkshire), Rothbury (Northumberland), and Breedon-on-the-Hill (Leicestershire) Jane Hawkes has identified the figural schemes, and their visual and (exegetical and liturgical) textual sources, to demonstrate that the iconographic choices made in the production of these monuments were intended to invoke the Christian sacraments of initiation and eucharist (Hawkes 2003). Here, an iconographic approach to the Irish crosses provides careful engagement with their carved details followed by comparison with earlier and contemporary Christian arts to identify and date their schemes and bringing this into conversation with the historical and textual evidence to further interpret their intended and perceived significance and meaning as well as their role in (preserving) contemporary liturgical practices. Interpretive sketches of the schemes discussed help to elucidate the details of the worn and weathered images and so facilitate closer engagement with the full iconography of each scene (Figures 1b, 2b, 4b, 5b and 8b); these were developed through multiple encounters with the crosses in varying seasons and times of day and are designed to show the totality of the extant carved details in a manner not achievable in a single photograph. Investigation of the iconographic choices and programmatic arrangement of the Baptism of Christ, Noah’s Ark, and the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace on these monuments will demonstrate that the carvings provide important evidence, complementary to that of texts, in the scholarly search for a better understanding of early medieval liturgical practices and that the crosses functioned to call to mind, and even facilitate, the rites of initiation of baptism and ordination as practised within the communities that commissioned them.

2. Iconography of Initiation

2.1. The Rite of Baptism

The space where baptisms took place has been distinctive from the earliest period of Christianity with the eighth-century Old Gelasian Sacramentary (Vat. Reg. Lat. 316) produced in Gaul recording that the baptismal rite included the processual movement from the church to the baptistery building (Ordo XI.90–5; Willis 1994, p. 127; Morris 1991, pp. 15–24). A similar particularity of space for the rite is also indicated, textually, in the Insular world: Carolyn Twomey has shown that the sacrament and liturgy of baptism took place outdoors, in rivers, until at least the tenth century; indeed, depictions of the Baptism of Christ on the Irish crosses—which in some cases predate depictions of the event elsewhere in the Insular world—may well echo this practice, picturing Christ and John the Baptist standing in flowing waters (Morris 1991, pp. 18–21; Twomey 2021). The idea of a ritual landscape outside the church building proper and involving the high crosses is certainly suggested in two early medieval Irish sources: an image in the eighth-/ninth-century Irish Gospel Book of Mulling (Dublin, TCD, MS 60; for alternative view see: Nees 1983) references crosses standing at various places throughout the hypothetical ecclesiastical enclosure; and the annals record a fire at Armagh in 1166 with its geographic spread described in terms of crosses named for saints (Hennessy and MacCarthy [1887] 1998, p. 153). Together, the naming practice for these crosses and the fact that they were invoked to reference the different spaces of the site suggests they functioned to delineate and distinguish each location for the remembrance of certain cults and the undertaking of particular rites. Indeed, that rituals of initiation, such as baptism and ordination, might take in a perambulation of the sacred space of the ecclesiastic grounds/bounds seems so logical it might be considered axiomatic. The iconographic programmes of some crosses certainly provide compelling evidence for this practice at those sites.

2.1.1. Iconography of The Baptism of Christ (Matthew 3:13–17; Mark 1:10–11; Luke 3:21–22)

The depictions of the Baptism of Christ on the early medieval Irish crosses will here be iconographically investigated to demonstrate how contemporary theological beliefs and liturgical practices were reflected in the imagery and, in turn, the value of these images to the study of historical liturgies. Robin Jensen, Everett Ferguson, and Twomey have each discussed the absence of a dominant iconographic type for the depiction of the rite of baptism in the early Church as deriving from individualised local ritual practices (Ferguson 2009; Jensen 2012; Twomey 2021). While a number of scholars have discussed the connection between Christ’s Baptism, the sacrament as it developed in the Apostolic Age, and the impact of both doctrine and ritual practice on the medieval imagery, the context of the Irish material has not been hitherto considered (Strzygowski 1885; Cullmann 1950; Burnish 1985; Ferguson 2009; Jensen 2012).

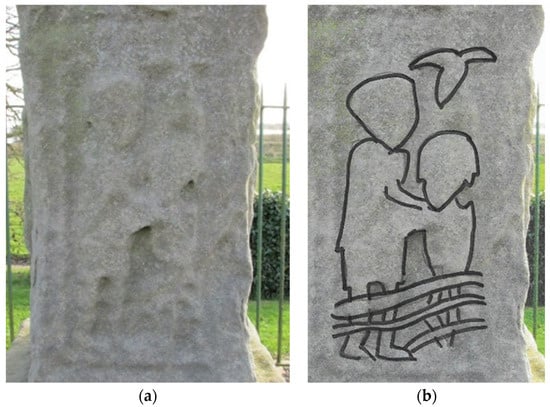

Individual elements of the recorded story of Christ’s Baptism are variably employed in depictions of the event developed at each site, and these are each discussed here, in turn. The concise passages in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke contain the elements essential to the Baptism’s perceived status as a theophany: the dove of the Holy Spirit, and the voice of God. An iconographically abbreviated version preserved on the cross at Arboe (Tyrone) includes these features: the figures of the Baptist (left) and the diminutive Christ, with the dove above his head (right), stand together facing one another in flowing water (Figure 1a,b). Christ’s Baptism, however, is depicted on eight further Irish crosses dating to between the mid-eighth and mid-tenth century, each of which presents variations on this established iconography (Arboe N1 (Tyrone), Armagh W3 (Armagh), Boho W4 (Fermanagh), Camus E2 (Londonderry), Donaghmore E3 (Tyrone), Galloon East W2 (Fermanagh), Broken Cross, Kells E1 (Meath), Killary W2 (Meath), Tall Cross, Monasterboice W2 (Louth)); these are worth exploring in more detail to establish what the visual choices and developments reveal about the rite as celebrated at these sites.

Figure 1.

(a,b). Baptism of Christ, N1, Arboe cross. Early ninth century. Arboe, Co. Tyrone. Photograph: Megan Henvey; Interpretive Sketch: Megan Henvey.

The flowing water, primary in the enactment of baptism, was a fixed feature of the imagery from the earliest period and is attested in all the Irish cross depictions as a series of horizontal or curving lines through the bottom half of the schemes. This iconography was, unsurprisingly, developed directly from John the Baptist’s practice which involved immersion in water in what was a temporary and preparatory symbolic washing away of sin (Cullmann 1950, p. 10; Morris 1991; Twomey 2021). Early exegetes understood that this type of purification was unnecessary for Christ himself; for Augustine, Jesus’ submission to Baptism by water indicated his humility; ‘He willed to be baptized by John in water, not that any iniquity in him might be washed away, but that his great humility might be commended’ (In aqua ergo baptizari voluit a Ioanne, non ut eius iniquitas ulla dilueretur sed ut magna commendaretur humilitas; Enchiridion to Laurentius on Faith, Hope, and Charity, 14 ed. van den Hout et al. 1969, p. 49; trans. Parker 1857, p. 116). Indeed, according to Matthew 3:15, Christ’s submission to this baptism was a crucial moment in salvation history, marking the beginning of his messianic ministry (Cullmann 1950, p. 16). Importantly, in the context of this discussion, it enabled the significance of the water to be understood as transforming from the symbolic to the actual. From an early date it was understood that Christ’s Baptism sanctified water for all future baptisms and that all life came from water (Souter 1919, pp. 48–54; Cullmann 1950, pp. 48–53; Ferguson 2009, p. 109). In an Insular context the importance of naturally flowing water for conducting a baptism is attested in Adomnán’s Life of St Columba, for when:

no water [was] to be found in that spot… the saint turned aside to the nearest rock, where he knelt and prayed a little while. When he stood up, he blessed the face of the rock, and at once water bubbled out from it…(Sharpe 1995, p. II.10. p. 161)

Thus, while the flowing waters in which Christ is depicted as baptised conforms to the typical iconography of the event, this is best understood as a deliberate reflection of the belief that it was this act that purified the baptismal waters for all and furthermore reflects contemporary practice where the rite of baptism continued to take place in open running water (Twomey 2021).

In each, however, of the Irish cross depictions of the event this water flows from two circular forms (Figure 2a,b), except at Armagh where they are replaced by a large, concave circle that may have featured an inset (of metal). With no iconographic precedent identified to date both Porter and Harbison considered the two circular forms to represent the two fonts Jor and Dan following Josef Strzygowski’s 1885 study which cites Josephus and Jerome alluding to this tradition (Strzygowski 1885; Porter 1971, p. 107; Harbison 1992, p. 251). Unlikely to reflect a liturgical or ritual function, this explicit reference to the river Jordan was perhaps intended to distinguish the depiction, readily identifiable as the locally practised rite of baptism, as the historic Baptism of Christ.

Figure 2.

(a,b). Baptism of Christ, E2, Camus cross-shaft. Ninth century. Camus-Macosquin Cemetery, Co. Londonderry. Photograph: Megan Henvey; Interpretive Sketch: Megan Henvey.

In early Christian and medieval images of the Baptism, Christ always stands fully upright in the flowing waters, facing the viewer (Schiller 1971, p. 132; Harbison 1992, p. 251). Depicted diminutively in early examples (Ferguson 2009, p. 124), he is later shown as tall, or taller, than the Baptist—as in the sixth-century paintings in the Catacombs of Ponziano, Rome—an antique convention indicating that he was of central importance (Ferguson 2009, p. 124, fig. 354). It is in keeping with this tradition that Christ is depicted equal in height to the Baptist on most of the Irish crosses suggesting that the model post-dates the sixth-century. At Arboe, however, the earlier type is preserved, facilitating two important significations: his humility, according to the typical aulic conventions depicting the person receiving a benefit as smaller than the patron (Ferguson 2009, p. 123); and the inclusion of the (now very worn) dove of the Holy Spirit above his head denoting the divine theophany of the historic event.

Christ’s nakedness is common to all iconographic types of the event and one explanation suggests that this is related to the ritual practice of baptism from the earliest period (Ferguson 2009, pp. 129–31). The early sources agree on the nakedness of a catechumen approaching the baptismal waters (Willis 1994, p. 129). For some early exegetes this represented a return to/rebirth in the pre-Fall innocence of Adam and Eve (Burnish 1985, p. 130). In a more specifically liturgical context, this frame of reference would have been familiar to early medieval Irish Christians, being attested in the Incipit of the baptismal liturgy as recorded in the Stowe Missal (Fol. 45b):

God, you who made Adam from the mud of the land, and when that man sinned in paradise, you did not consider that a sin of death, but you saw fit to restore him in sanctity through your own blood, and you will restore glorious Jerusalem.

(deus, qui adam de limo terrae fecisti, et ille in paradiso peccauit, et illum peccatum mortis non reputasti, sed per per sanguinem unigeniti tui recuperare digneris et in sancta, hirusalem glorientem reducis).Warren 1881, p. 207; trans.: Author

A circumambulatory reading of the Arboe cross and the Tall cross at Monasterboice makes this relationship explicit by presenting schemes involving Adam and Eve on the same, lowermost register. Ferguson has further argued that Christ’s nakedness in depictions of the Baptism—as at Arboe, Armagh, and Camus—reinforces themes linking him to figures receiving deliverance or healing, a connection drawn in the iconographic contexts of both the Arboe and Armagh crosses (Ferguson 2009, pp. 124, 128, 131). At Armagh it shares a register with both the Sacrifice of Isaac and Daniel in the Lions’ Den, while at Arboe, the Baptism is placed below a healing miracle on the same face of the cross, perhaps drawing on another passage from the Stowe Missal’s baptismal liturgy which may have been understood as a reference to Christ’s miraculous healing of the blind man, ‘Drive from him all blindness of heart’ (caecitatem cordis omnem ab eo expellens; Jn 9:1–12; fol. 48b; Warren 1881, p. 209; trans.: Whitaker and Johnson 2003, p. 276). Thus, Christ’s nakedness in the depictions at Armagh, Arboe, and Camus can be understood in the light of both contemporary theology and liturgical practice.

An element of the visual arrangement that does, however, distinguish the Irish examples is the way the Baptist stands, with Christ, in the flowing waters, rather than beside him on a mound, as was the norm in early Christian art: as in the mosaic in the early sixth-century Arian Baptistery, Ravenna (Figure 3) and on a sixth-century ivory, possibly from Syria, now in the British Museum (London, BM, Inv.1896,0618.1).

Figure 3.

Baptism of Christ, mosaic, fifth century, Arian Baptistery, Rome. Photograph: https://www.flickr.com/photos/paullew/11904056613 (accessed on 12 May 2020).

This iconographic divergence might reflect the nature of the ritual as practised in early medieval Ireland; the ecclesiastic performing the rite entered the water with the communicant, despite the cold conditions (Morris 1991, pp. 19–20). One of the earliest depictions of the event from Britain, in the tenth-century Benedictional of Æthelwold (London, BL, Add MS 49598, fol. 25r), also features John in the waters, suggesting that such practices were familiar across the Insular world.

Excepting the abbreviated depiction at Arboe, all Irish cross depictions of the Baptism also include between one and three additional figures, pictured either as busts, diminutive figures above the fonts, or as full-length figures flanking the action, and representing angels as witnesses or bystanders (Schiller 1971, p. 133; Jensen 2012, p. 186; Ferguson 2009, p. 129). Although wingless at all but Kells, the way in which these figures hover at Armagh, Camus, Donaghmore, Galloon, and Killary suggests flight, pointing to their identification as angels, which alongside the ‘laying on of hands’ by John the Baptist, can be understood as symbolic signifiers of the ‘bestowal of the Holy Spirit’ in keeping with early evangelical thought (Ferguson 2009, pp. 125–26). This is particularly pertinent at Armagh, Boho, and Camus where the dove is not discernible in the carvings. Further, Cullmann has explained the connection between Christ’s Baptism and miraculous deeds as being rooted in the faith of those who seek salvation, noting that this is not necessary of the catechumen—who may be an infant—but the congregation as a whole (Cullmann 1950, p. 55). Against this background, these figures, and the further, non-angelic, bystanders included on the Broken cross at Kells, and Tall cross at Monasterboice, may well have been intended to reference the faithful attendees; necessary witnesses to the baptismal act, again reflecting the rite as practised by the early Christian communities.

Overall, it is clear that depictions of the Baptism of Christ on the Irish crosses were developed and existed within a complex of theological and patristic writings, liturgical and ritual practices specific to the communities that made and used them. In reflecting the local practice of baptism taking place with both baptist and communicant standing in flowing/open waters, and with bystanders taking part, the study of these depictions provides important evidence for the early medieval rite of baptism in Ireland. This further enables the suggestion that the crosses themselves played a ritual function in the procession from the church to the water, particularly tenable at sites such as Arboe where the cross is positioned on the edge of a Lough. A brief consideration of the iconography of Noah’s Ark further recommends this interpretation.

2.1.2. Iconography of Noah’s Ark (Genesis 8:1–11)

As with the Baptism of Christ, the biblical story of Noah’s Ark contains a number of details, comparison with which facilitates identification of possibly six examples on the Irish crosses where the specific selection of certain elements of the iconography provides evidence for local theological beliefs surrounding, and liturgical recollections of, the event. The varied iconographic contexts of this scene at Armagh (Armagh), Camus (Londonderry), Donaghmore (Down), Kells Broken cross, Killary (both Meath) and less certainly at Killamery (Kilkenny), bears testimony to early Christian exegesis on the subject which saw it variously exploited typologically, a fact that makes its relative absence in Insular art generally all the more notable (Gatch 1975; Unger 1991; Harbison 1992, pp. 197–98; Lezzi 1994).

Turning first to the typological significance of the bird in flight: in the upper centre of the panel at Killary (Figure 4) is a bird flying from right to left with a large branch in its beak; the worn condition of the panels at Armagh, Camus, and the Kells Broken cross make identification of the details at the top of those panels more difficult, although each does bear a similarly shaped, carved detail in the same position (at Kells it is to the left) which can be identified by comparison with the better-preserved scheme at Killary. At Donaghmore the break in the shaft has resulted in the loss of the upper portion of the scheme making it impossible to ascertain whether this detail was included. The significance of the bird lies in its typological relationship to the dove of the Holy Spirit at Christ’s Baptism. Bede, in his commentary on Genesis, for instance, set out how:

the dove, which carried the branch of the olive tree after the flood through the open window into the ark, that when the Lord was baptized in the Jordan the heavens were opened and the Holy Spirit descended in the form of a dove upon him.

It thus enabled the scene to be understood as a typological baptismal rebirth that included those in the ark: the faithful (Norberg 1982, pp. 914–17 Book XI, Letter 28).(Potest in columba, quae aperta post diluvium fenestra ramum olivae intulit in arcam, etiam hoc praefiguratum intelligi, quod, baptizato Domino in Jordane, aperti sunt coeli, et descendit Spiritibus sanctus in specie columbae super eum).Bede, In Gen., P.L. 91, Migne 1850, Col.101; trans. Kendall 2008, p. 195; Bk.8, Ch.10–11b

Figure 4.

Noah’s Ark, E3, Killary cross. Ninth–tenth century. Killary, Co. Meath. Photograph: http://www.irishstones.org/place.aspx?p=734&i=7 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

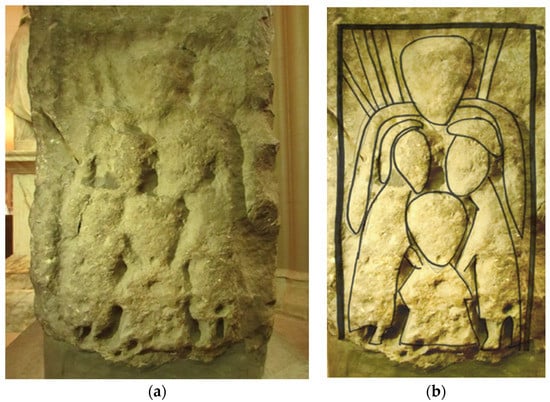

While for Augustine the ark was a symbol of the Church of which the incorruptible timbers and their contents were baptised by the waters (Walsh and Monahan 1952, pp. 480–84; Dods 1873, Tract VI, Para. 19; Jungmann 1972, p. 167), other writers reinforced this point with reference also to the dove (Deferrari 1963, Ch. 4, Para. 24; Jungmann 1972, p. 85; Kendall 2008, pp. 181–98; Oehler 1853, pp. 627–28; Souter 1919, p. 56). In an Irish context the waters are only (implicitly) present at Donaghmore (Down) through the fish below the ark (Figure 5a,b); it was the dove which thus performed the reference to baptism, typologically connecting Noah’s Ark and Christ’s Baptism as expounded in the writings of those whose texts circulated in the region at the time.

Figure 5.

(a,b). Noah’s Ark, W2, Donaghmore cross. Early ninth century. St Bartholemew’s Church of Ireland Graveyard, Donaghmore, Co. Down. Photograph: Megan Henvey; Interpretive Sketch: Megan Henvey.

Depictions of the ark itself form two main types: the rectangular box-type and a three-storeyed boat-type, the first appearing early in Christian art, as in the late-third-century Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter, Rome (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Noah’s Ark, Fresco, late-third century, Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter, Rome. Photograph: Nigel Morgan (York).

This has been understood to derive from the Hebrew (תבה/lebah), Greek (λάρναξ/appetee), and Latin (arca): words for ‘ark’ in the biblical texts that also denote box or chest (Unger 1991, p. 38; Lezzi 1994, pp. 302–3), while simultaneously facilitating cross-references to the ancient Greek story of Deucalion (Unger 1991, p. 38; Lezzi 1994, pp. 302–3; Clements 2010, esp. pp. 298–99). The second type, as preserved in the late-tenth-/early-eleventh-century Roda Bible (Paris, Bib. Nat. MS. lat. 6, fol. 9; Contessa 2009), emerged in early medieval contexts and developed through a different means of faithfully following the biblical text: focusing on the words spoken by God to Noah (Gen. 6:15–16). Neither of these types, however, explain the ark on the Irish crosses, where it forms a large, enclosed, seaworthy ship. The earliest example of this ship-type ark is preserved in the early-fifth-century frescoes in the Peace Chapel at El-Bagawat in Egypt (Figure 7) which offers a good comparator for that on the Irish crosses, particularly at Killary. The similarities between the El-Bagawat and Irish cross depictions have been variably explained as possible evidence of indirect links between the two regions, or as evidence of the artists’ familiarity with boat-forms – being coastal peoples (Contessa 2009, p. 264; Lezzi 1994, pp. 308, 310–12).

Figure 7.

Noah’s Ark, Fresco, early fifth century, Egypt, Peace Chapel at El-Bagawat. Photograph: https://www.akg-images.com/archive/-2UMDHU2YKNXJ.html (accessed on 22 May 2020).

However, the ubiquitous animal-headed and spiral-form prows on the Irish cross depictions of the ark do suggest an Insular iconographic tradition stemming from knowledge of either Viking or pre-Viking ships (or their pictorial representation) (Henry 1930; Bruce-Mitford 1970, pp. 146–48; Porter 1971, p. 106; Gatch 1975, p. 9; Farrell 1978, pp. 48–49; Unger 1991, p. 46; Lezzi 1994, p. 312), as it is preserved elsewhere in the c.1000 Anglo-Saxon Junius 11 manuscript (Oxford, Bod. Lib. Junius 11, pp. 65, 66, 68). Together, the form of the ship and the addition of the distinctive prows might suggest that the ultimate source for the ark-type on the Irish crosses was developed locally from an early eastern model, thus positioning it in an intermediary position in the development of the iconography in the West.

Bede stressed that the ark was capable of carrying a great load, floating on the waters, and weathering any storm not because of its form, but because it was under God’s protection (Kendall 2008, p. 183). Thus, its depiction as a sea-worthy ship was perhaps intended to reinforce that it was a safe vessel, something not achieved in the earlier, typological box-type ark (Gatch 1975; Unger 1991, p. 38; Lezzi 1994, pp. 304–5; Contessa 2009). There is, nevertheless, another explanation.

Within an exegetical context that interpreted the ark as the Church, and the flood waters as a type of baptism, Bede goes further, explaining how:

For the bough of an olive tree, found outside and brought into the ark in the mouth of the dove, is the type of those who receive baptism indeed outside of the Church, but are fruitful with an abundance of charity and morally upright with pious devotion as if with the greenness of leaves.

Perhaps in fashioning the ark as a contemporary ship those responsible for the depictions on the crosses were indicating that the recent (Viking) invaders of the island presented an opportunity to undertake conversion and baptism. If the olive branch was, as Tertullian put it at a very early date, ‘a token which is held out even among the heathen as a harbinger of peace’ (mundi pacem caelestis irae praeco columba terries adnuntiavit dimissa ex arca et cum olea reversa; Oehler 1853, pp. 627–8; trans. Souter 1919, p. 56), then the inclusion of the dove—a symbol of the Holy Spirit present also at the Baptism—with the olive branch approaching the Viking-type ark/ship is a powerful statement of intent.(Ramus enim olivae foris inventus et ore columbae in arcam illatus typum gerit eorum qui extra Ecclesiam quidem baptisma percipiunt, sed pinguedine charitatis fructuosi, et pia intentione velut foliorum sunt viriditate integri).Bede, In Gen., P.L. 91, Migne 1850, Col. 101; trans. Kendall 2008, p. 195; Bk.8, Ch.10–11b

The iconographic association of Noah’s Ark with baptismal themes on the Irish crosses further points to its possible role in the liturgy of baptism as practised in early medieval Ireland, and the role of certain crosses in these rituals. On the Kells Broken cross Noah’s Ark is depicted above Adam and Eve which, with a circumambulatory reading taking in the Baptism of Christ on the same—lowermost—register, facilitates engagement with themes of deliverance and salvation. A similar arrangement is present at Killary, where the association is yet more explicit: Noah’s Ark shares a register with the depiction of the Baptism. Thus, the baptismal liturgy as practised at these sites might have included reference to Noah’s Ark, reflected in the iconographic programmes of these crosses and further suggesting their role in the ritual celebration of baptism.

The development of the iconography of Noah’s Ark in early medieval Ireland, which includes the dove and Viking ship-type, points to a desire to convert and baptise those arriving on the island. The typological connection to the Baptism of Christ established in earlier exegeses which is specifically and deliberately employed in this iconography and certain of its programmatic associations might, furthermore, in the absence of textual sources, be seen to reflect the inference of this biblical event in the readings and prayers of the liturgy of baptism in early medieval Ireland.

2.2. The Rite of Ordination

Traditionally employed in relation to the initiation of preaching ecclesiastics (see, for e.g., Barrow 2018), in the context of early medieval Ireland where the roles of ecclesiastics were not so precisely defined (see, for e.g.,: Sharpe 1983; De Paor 1997, p. 182; Etchingham 1999, pp. 241–43), the little-attested rite of ordination may, therefore, have been used in a variety of contexts, and evidence for this is provided in the iconography of the high crosses. Roger E. Reynolds has importantly shown how images of ordinations from early medieval libelli for the rite—although few in number—can be usefully employed in the construction of an understanding of the practicalities of the ritual ceremony (Reynolds 1983). While no such images have been identified on the Irish crosses, another aspect of their carved programmes can be seen to closely align with the extant textual evidence of the rite of ordination in early medieval Ireland. The iconographic context of the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace reflects its invocation in the hymns of the rite of ordination as preserved in the Vespasian Psalter (fol. 150r–151r) and Antiphonary of Bangor (Warren 1881, pp. 187–94; Gearhart 2013, p. 118; Billett 2014, p. 113; Hines 2015, p. 271). Here, exploration of the iconography of this scheme and its programmatic placement on the Irish crosses, will demonstrate the role of the crosses in the preservation and celebration of this liturgy, as well as contribute to discussions surrounding the individualized character of early medieval ecclesiastic settlements and the role/s and responsibilities of those they housed.

Iconography of The Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace (Daniel 3:19–28)

Seven Irish crosses feature depictions of the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace: Arboe (Tyrone), Armagh (Armagh), Tall cross Monasterboice (Louth), Moone (Kildare), Seir Kieran (Offaly), Patrick and Columba Kells (Meath), and Galloon West (Fermanagh). On four it is placed in direct relationship with the depiction of Paul and Anthony in the Desert; here, an iconographic exploration of these depictions of the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace will point to a well-established association between the scheme and the rite through which Ireland’s early medieval religious took orders. Two studies of the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace distinguish iconographic typologies: Ann Walton deals exclusively with earlier second- to sixth-century depictions classifying a linear and pyramidal type, while Colum Hourihane focused on the Irish material distinguishing frontal-facing and kneeling-in-profile arrangements, understanding this as the final resolution of the imagery (Walton 1988; Hourihane 2001). It is clear that the Irish versions follow a common compositional type (Walton’s ‘pyramidal’) that is preserved on a fourth-century lamp in the Vatican; Hourihane’s further distinctions cannot be upheld, however, as the Three Hebrews adopt a number of varied poses (Walton 1988, p. 58; Portnoy 2017, pp. 107–8). Thus, here, each detail of the schemes will be considered in turn, with their theological and liturgical significances outlined.

The position of the flames in relation to the angel in the schemes at Armagh, Arboe, and Kells cross of Patrick and Columba points to a specific theological conception of the event. The flames of the furnace are depicted as vertical lines on the left and right at the top of the panel suggesting that the four figures are together in the furnace (Figure 8a,b), among the flames, as is the case in many of the earlier images, including the third-century Cappella Greca fresco (Walton 1988, p. 61). This suggests that the typical Irish iconography reflects a specific and complex theology involving the figure of the angel, which was developed from a late antique continental model (Hourihane 2001, pp. 73–76).

Figure 8.

(a,b) Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace, N1, Armagh cross. Mid-eighth to early ninth century. St Patrick’s Church of Ireland Cathedral, Armagh, Co. Armagh. Photograph: Megan Henvey; Interpretive Sketch: Megan Henvey.

The angel, not included in the earliest versions, is clearly identifiable on the Irish crosses (Hourihane 2001; Walton 1988, pp. 57–58) and importantly occupies a space within the flames. Phyllis Portnoy has argued that the Irish cross iconographies might be understood as providing parallels for the missing iconographic programme of the Junius 11 manuscript (P. 185) which reads, ‘An angel … enfolded the noble youths in his arms under the fiery roof’ (Engel … freobearn fæðmum beÞeahte under Þam fyrenan hrofe, Krapp 1931, p. 185; Bradley 1982, p. 73). The deliberate focus on, and repetition of, OE fæđm (enfolded) is well-paralleled in the Irish iconography where the angel embraces the three Hebrews and effectively shields them from the fires of the furnace, as at Armagh (Portnoy 2017, pp. 107–8). This suggests that the iconographic type attested in most Irish depictions (excluding Moone which overall features imageries of almost entirely unique types) was developed locally with knowledge of both earlier continental models and with reference to ideas and texts circulating throughout the Insular world.

Having established the iconographic sources of this scheme on the Irish crosses we can turn to consider why it appears with such prevalence on these monuments. In a study of early Christian funerary art Jensen drew theological links between the Three Hebrews and Noah’s Ark, with which it was frequently juxtaposed, and argued that the predominant themes were martyrdom and/or resurrection (Jensen 2012, pp. 79, 84). In the later context of the Irish crosses, the event has generally been understood as part of a scheme relating to the Ordo Commendatio Animae, a prayer found in early medieval Irish texts including the ninth-century Martyrology of Oengus, and the Stowe Missal (Warren 1881, p. 226; Stokes 1905, pp. 284–88; Flower 1954; Roe 1966, p. 13; Henry 1967, pp. 142–44; Edwards 1983, pp. 26–27; Harbison 1992, pp. 350–81; 1999, p. 157; Herbert 1997; Jensen 2012, pp. 79, 84). However, the story of the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace as told in the Book of Daniel had a further, more prominent significance in early medieval liturgical practices, particularly in the Insular world, and it is in these contexts that the iconographic and programmatic variations of the scene on the crosses of Armagh, Arboe, the Tall cross Monasterboice, and Moone are perhaps best explained.

The importance of the Three Hebrews in the various forms of the early liturgy was stressed by Robert Farrell, following John Walton Tyrer (Farrell 1967, pp. 132–34). Daniel 3:1–90 was often read during the Easter Vigil or Holy Saturday service, including both the Song of Azarias and the Song of the Three, placing an emphasis (suited to the occasion) on God’s grace and mercy (Tyrer 1932, pp. 156–57; Farrell 1967, pp. 134–35). John Hines and Heidi Gearhart have both also highlighted that the Benedicite Canticle or Hymnum trium puerorum was central to the Gallican Rite, which is attested in an Insular context in the mid-eighth-century Vespasian Psalter and Antiphonary of Bangor (Warren 1881, pp. 187–94; Gearhart 2013, p. 118; Billett 2014, p. 113; Hines 2015, p. 271). Familiar in the liturgy, the prominence of the story is further attested in the Insular world in Muirchú’s employment of the narrative structure of Daniel 3:1–24 in the account of King Lóegaire’s attack on St Patrick, on the inscription on the possibly ninth-century Honington clip, and in the tenth-century Junius 11 manuscript which preserves the Old English poem (Daniel); this includes both prayers in its poetic narrative of the Book of Daniel (O’Loughlin 2000, pp. 99–103; Hines 2015; Portnoy 2017; Alexander 2018, pp. 174–75).

The centrality of the Hebrews’ prayers in Insular liturgy and poetry thus demonstrates a clear focus on their prayerfulness. Indeed, Warren noted that the Canticle was also included in the liturgy of Ember Saturday during which ordinations took place (Warren 1881, p. 190, n.4). On four of the seven crosses where this scheme is depicted, it is in direct relationship with the image of Paul and Anthony—the models of ascetic monasticism—Receiving Bread in the Desert. On these four crosses—Armagh, Arboe, the Tall cross Monasterboice, and Moone—this explicit relationship places careful emphasis on the need for a prayerful frame of mind. More crucially, it strongly suggests a direct reference in the programme of those crosses to the Ember Saturday liturgy of the rite of ordination, the ritual at which a person commits to live as Paul and Anthony. The crosses therefore can be understood to have functioned to call to mind one’s vows, and/or in the celebration of that liturgy. This further points to the nature of those communities, where members would take, or had taken, religious orders, the monastic character of which are suggested in the pairing of the scheme with the depiction of Paul and Anthony. This furthermore points to the individualized nature of ecclesiastic communities in early medieval Ireland, and the need to reconsider what is meant by ‘ordination’ in this context.

3. Conclusions

An iconographical investigation of the carved depictions and programmatic arrangements of the Baptism of Christ, Noah’s Ark, and the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace on the Irish high crosses has facilitated a number of new insights to both early medieval Irish liturgies of initiation, the role and function of the crosses themselves within the communities that commissioned, made and used them, and the individualized nature of these communities. Depictions of the Baptism that feature the flowing water with the distinctive iconography of both Christ and the Baptist standing in it has been shown to corroborate what has been gleaned from textual sources: that in the Insular world the ritual took place in open, flowing waters, and additionally to this, that the ecclesiastic performing the rite also stood in the water (Morris 1991; Twomey 2021). Meanwhile the varying number of non-/angelic bystanders reflects contemporary theological interests surrounding the event which dictated that their faith was essential to the rite. The particularity of the iconography of the double-circular form of the fonts of the river Jordan appears to support this in specifically referencing the river in which Christ was baptised, enabling recognition of the historical event of the past to those in the present otherwise personally familiar with the actions depicted. Thus, the iconography of the Baptism of Christ on the Irish crosses clearly reflects the contemporary, local, liturgical practice of this rite of initiation.

With the depictions of Noah’s Ark, the inclusion of the dove draws a further, clear typological reference to the rite, and the specific Viking ship-type with curling and beast-headed prows appears to suggest that the Christian communities responsible for the production of the crosses were aware of the opportunity to convert – and baptise – the contemporaneous incomers to the island. In the absence of textual accounts of the rite, it might be speculated that they included reference to the typological story of Noah’s Ark in the flood. More importantly, however, these findings together suggest that the high crosses may have played a role in the processual ritual of Baptism, as the clergy, catechumens, and congregation moved between the church and the flowing waters. The programmatic relationship between the depictions of the Baptism of Christ and Noah’s Ark has been shown to further support this contention.

The Antiphonary of Bangor already demonstrates that the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace featured in the liturgy of Ember Saturday when ordinations took place; here, the programmatic pairing of the iconography of the event with Paul and Anthony in the Desert on four high crosses suggests that this was a well-known liturgical rite, practised throughout early medieval Ireland. This, in turn, sheds light on the monastic character of those communities—reframing the application of the term ‘ordination’ in the context of early medieval Ireland—and further points to the role of high crosses as calling to mind the promises of the sacraments of initiation and/or the facilitation of their ritual occasion.

Overall, it can be seen that the iconography of the high crosses provides invaluable insights into the nature of the early medieval communities that made and used them; the function of the monuments themselves in Christian rituals; and their role as evidence complementary to that provided by extant texts in preserving early medieval liturgies, in particular the rites of baptism and ordination.

Funding

This research was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander, Elizabeth. 2018. Visualising the Old Testament in Anglo-Saxon England. Ph.D. thesis, University of York, York, UK. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, Julia. 2018. The Bishop in the Latin West 600–1100. In Celebate and Childless Men in Power: Ruling Eunuchs and Bishops in the Pre-Modern World. Edited by Almut Höfert, Matthew Mesley and Serena Tolino. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, Jesse. D. 2014. The Divine Office in Anglo-Saxon England: 597-c.1000. London: Henry Bradshaw Society. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Sid Arthur Jamesand Bradley. 1982, Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent.

- Bruce-Mitford, Robert. 1970. Ships’ Figure-heads in the Migration Period and Early Middle Ages. Antiquity 44: 146–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnish, Raymond. 1985. The Meaning of Baptism: A Comparison of the Teaching and Practice of the Fourth Century with the Present Day. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, Ruth. 2010. A shelter amid the Flood: Noah’s ark in early Jewish and Christian art. In Noah and His Book(s). Edited by Michael E. Stone, Aryeh Amihay and Vered Hillel. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 277–99. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Bertram Colgrave, and Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors. 1969, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Contessa, Andreina. 2009. Noah’s Ark and the Ark of the Covenant in Spanish and Sephardic Medieval Manuscripts. In Between Judaism and Christianity: Art Historical Essays in Honor of Elisheva (Elisabeth) Revel-Neher. Edited by Katrin Kogman-Appel and Mati Meyer. Leiden: Brill, pp. 171–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cullmann, Oscar. 1950. Baptism in the New Testament, Studies in Biblical Theology. London: SCM Press Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- De Paor, Liam. 1997. Ireland and Early Europe: Essays and Occasional Writings on Art and Culture. Dublin: Four Courts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Roy Deferrari. 1963, Theological and Dogmatic Works, The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press.

- Dods, Rev. 1873. Marcus. The Works of Aurelius Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, Lectures or Tractates on the Gospel According to St. John. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Nancy. 1983. An Early Group of Crosses from the Kingdom of Ossory. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 113: 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- Etchingham, Colmán. 1999. Church Organisation in Ireland A.D. 650 to 1000. Maynooth: Laigin Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, Robert T. 1967. The Unity of Old English Daniel. Review of English Studies 18: 117–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A. W. 1978. The Armagh Cross and Dunluce Castle Ship Representations: Some Problems of Interpretation. Irish Archaeological Research Forum 5: 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Everett. 2009. Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, John Douglas Close. 1965. Christian Initiation: Baptism in the Medieval West. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Flower, Robin. 1954. Irish High Crosses. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institute 17: 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatch, Milton McC. 1975. Noah’s Raven in Genesis A and the Illustrated Old English Hexateuch. Gesta 14: 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart, Heidi C. 2013. Work and Prayer in the Fiery Furnace: The Three Hebrews on the Censer of Reiner in Lille and a Case for Artistic Labor. Studies in Iconography 34: 103–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gefreh, Tasha. 2015. Place, Space and Time: Ion’s Early Medieval High Crosses in the Natural and Litugical Landscape. Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Harbison, Peter. 1992. The High Crosses of Ireland: An Iconographical and Photographic Survey. Bonn: R. Habelt, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Harbison, Peter. 1999. The Golden Age of Irish Art: The Medieval Achievement, 600–1200. New York: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, Jane. 1999. Anglo-Saxon Sculpture: Questions of Context. In Northumbria’s Golden Age. Edited by Jane Hawkes and Susan Mills. Thorpe: Sutton Publishing Ltd., pp. 204–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, Jane. 2003. Sacraments in Stone: The Mysteries of Christ in Anglo-Saxon Sculpture. In The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300–1300. Edited by Martin Carver. Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 351–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, Jane. 2005. Figuring Salvation: An Excursus into the Iconography of the Iona Crosses. In Able Minds and Practised Hands: Scotland’s Early Medieval Sculpture in the 21st Century. Edited by Sally M. Foster and Morag Cross. Leeds: The Society for Medieval Archaeology, pp. 259–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy, William Maunsell, and Bartholomew MacCarthy. 1998. Annála Uladh: Annals of Ulster or otherwise Annala Senait, Annals of Senata chronicle of Irish affairs from A.D. 431 to A.D. 1540. Edited by Nollaig Ó Muraíle. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, First publihsed in 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Françoise. 1930. Les Origines de L’Iconographie Irlandaise. Revue Archéologique 32: 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Françoise. 1967. Irish Art During the Viking Invasions (800–1020 A.D.). London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Henvey, Megan. 2021. Transmitted in Stone: Church Organisation in Early Christian Ireland. In Transmissions and Translations in Medieval Literary and Material Culture. Edited by Megan Henvey, Amanda Doviak and Jane Hawkes. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, Catherine. 1997. Psalms in Stone: Royalty and Spirituality on Irish High Crosses. Ph.D. thesis, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, John. 2015. The Benedicite Canticle in Old English Verse: An Early Runic Witness from Southern Lincolnshire. Anglia 133: 257–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourihane, Colum. 2001. De Camino Ignis: The Iconography of the Three Children in the Fiery Furnace in Ninth-Century Ireland. In From Ireland Coming: Irish Art from the Early Christian To the Late Gothic Period and Its European Context. Edited by Colum Hourihane. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Robin M. 2012. Baptismal Imagery in early Christianity: Ritual, Visual, and Theological Dimensions. Grand Rapids: Baker Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann, Josef A. 1972. The Early Liturgy to the Time of Gregory the Great. London: Darton, Longman & Todd. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Calvin B. 2008. Bede on Genesis. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krapp, George Philip. 1931. The Junius Manuscript, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Record 1. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lezzi, Maria Teresa. 1994. L’arche de Noe en forme de bateau: Naissance d’une tradition iconographique’. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiéval Xe–XII e Siècles XXXVII: 301–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migne, Jacques-Paul. 1850. Patologia Latina, 91: Bedae Venerabilis Opera Omnia. Paris: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Richard. 1991. Baptismal Places 600–800. In People and Places in Northern Europe 500–1600. Edited by Ian Wood and Niels Lund. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer, pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nees, Lawrence. 1983. The colophon drawing int the Book of Mulling: A supposed Irish monastery plan and the tradition of terminal illustration in early medieval manuscripts. Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies 5: 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, Dag, ed. 1982. S. Gregorii Magni: Registrum Epistularum Libri VIII–XIV, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina 140A. Turnholt: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. 1986. Christ over the beasts and the Agnus Dei: Two multivalent panels on the Ruthwell and Bewcastle crosses. In Sources of Anglo-Saxon Culture. Edited by Paul E. Szarmach. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, pp. 377–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. 1987. The Ruthwell Cross and Irish High Crosses: Some Points of Comparison and Contrast. In Ireland and Insular Art: A.D. 500–1200. Edited by Michael Ryan. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, pp. 118–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. 2006. Ruthwell and Iona: The meeting of Saints Paul and Anthony Revisited. In The Modern Traveller to Our Past: A Festschrift in Honour of Ann Hamlin. Edited by Marion Meek. Dublin: DPK, pp. 138–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. 2011. High Crosses, the Sun’s Course, and Local Theologies at Kells and Monasterboice. In Insular and Anglo-Saxon Art and Thought in the Early Medieval Period. Edited by Colum Hourihane. State College: Penn State University. [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin, Thomas. 2000. Celtic Theology: Humanity, World and God in Early Irish Writings. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, Jennifer. 2013. Seeing the Crucified Christ: Image and Meaning in Early Irish Manuscript Art. In Envisioning Christ on the Cross: Ireland and the Early Medieval West. Edited by Juliet Mullins, Jenifer Ní Ghrádaigh and Richard Hawtree. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 52–82. [Google Scholar]

- Oehler, Franciscus, ed. 1853. Tertulliani: Quae Supersunt Omnia. Lipsiae: T. O. Weigel. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, Eric. 2006. Art and Liturgy in the Middle Ages: Survey of Research (1980–2003) and Some Reflections on Method. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 105: 170–84. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by John Henryand Parker. 1857, Seventeen Short Treatises of Saint Augustine. Oxford: Rivington.

- Porter, Arthur Kingsley. 1971. The Crosses and Culture of Ireland. New York: Benjamin Blom. [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy, Phyllis. 2017. Daniel and the Angel’s Embrace: An Insular Innovation? In England, Ireland and the Insular World: Textual and Material Connections in the Early Middle Ages. Edited by Mary Clayton, Alice Jorgensen and Juliet Mullins. Temple: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam, Heather. 2020. Between the Embodied Eye and Living World: Clonmacnoise’s Cross of the Scriptures. The Art Bulletin 102: 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Roger E. 1983. Image and Text: The Liturgy of Clerical Ordination in Early Medieval Art. Gesta 22: 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, Helen M. 1966. The High Crosses of Kells. Rev. ed. Moattown: Meath Archaeological and Historical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, Gertrud. 1971. Iconography of Christian Art Volume I. London: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, Richard. 1983. Some Problems Concerning the Organization of the Church in Early Medieval Ireland. Peritia 3: 230–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Translated and Edited by Richardand Sharpe. 1995, Adomnán of Iona: Life of St Columba. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Souter, Alexander. 1919. Tertullian’s Treatises: Concerning Prayer, Concerning Baptism, Translations of Christian Literature. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Stalley, Roger. 2020. Early Irish Sculpture and the Art of the High Crosses. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, Whitley. 1905. Félire Óengusso Céli Dé: The martyrology of Oengus the Culdee, Henry Bradshaw Society 29. London: Harrison and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Strzygowski, Josef. 1885. Iconographie der Taufe Christi. Munich: Riedel. [Google Scholar]

- Twomey, Carolyn. 2021. Rivers and Rituals: Baptism in the Early English Landscape. In Meanings of Water in Early Medieval England, Studies in the Early Middle Ages. Edited by Carolyn Twomey and Daniel Anlezark. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer, John Walton. 1932. Historical Survey of Holy Week: Its Services and Ceremonial. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Unger, Richard W. 1991. The Art of Medieval Technology: Images of Noah the Shipbuilder. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van den Hout, M. P. J., E. Evans, J. Bauer, R. Vander Plaetse, S. D. Ruegg, M. V. O’Reilly, and C. Beukers. 1969. De Fide Rerum Invisibilium; Enchiridion Ad Laurentium de Fide et Spe et Caritate; De Catechizandis Rudibus; Sermo Ad Catechumenos de Symbolo. Sermo de Disciplina Christiana; De Utilitate Ieiunii; Sermo de Excidio Urbis Romae; De Haeresibus. CCSL 46. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Translated and Edited by Gerald G. Walsh, and Grace Monahan. 1952, (Augustine). The City of God, Books VIII–XVI. New York: Fathers of the Church, Inc.

- Walton, Ann. 1988. The Three Hebrew Children in the Fiery Furnace: A Study in Christian Iconography. In The Medieval Mediterranean: Cross-Cultural Contacts. St. Cloud: North Star Press of St. Cloud. Inc., pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Frederick Edward. 1881. The Liturgy and Ritual of the Celtic Church. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, E. C., and Maxwell E. Johnson. 2003. Documents of the Baptismal Liturgy, 3rd ed. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Geoffrey Grimshaw. 1994. A History of Early Roman Liturgy to the Death of Pope Gregory the Great. London: Henry Bradshaw Society. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).