Living Islam in Prison: How Gender Affects the Religious Experiences of Female and Male Offenders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Researching Women and Religion in Prison

2.1. Researching Women and Islam in Prison

2.2. Intersectionality

3. Context of the Research and Methodology

- Who are, in socio-demographic and socio-religious terms, the Muslims who experience religious change in prison?

- Why do many prisoners choose to practice Islam in European prisons?

- What types of Islam are practiced in prison?

- What are the benefits and risks associated with Islam in prison?

- How are the processes of religious conversion and change managed by prison authorities and prison chaplaincies?

3.1. A Mixed-Methods Study

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Muslim Men and Women at HMP Parrett and La Citadelle

4. About the Sample: Socio Demographics and Religious Worldviews

4.1. Socio-Demographics

- -

- 71% were born Muslim.

- -

- 29% who had converted to Islam; 22% had done so in prison.

- -

- The sample clustered strongly in the 24–36-year-old age bracket.

- -

- Regarding ethnicity and national origin, there are differences between the three jurisdictions. For example, prisoners in England are predominantly of Asian (Pakistani and Bangladeshi) or Caribbean origin, with an important percentage of white British converts. Prisoners in Switzerland come from three main regions: the Balkans, North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, inmates in France are mainly with Maghreb origin. A second significant difference between the three jurisdictions is that the majority of Muslim prisoners in Switzerland are foreigners by law, whereas in England and France, if the majority are second or third generation immigrants, they have the nationality of the country of incarceration.

- -

- The sample’s levels of education were also typical of a prison population with 19.3% (n = 45) having no qualifications mirrored exactly by the same number with a university degree 19.3% (n = 45). Half of the sample had either completed compulsory secondary school education (26.6%) or had done some vocational training (24.9%).

- -

- The sample’s sentence length and the seriousness of their conviction ranged from lesser offences carrying a few months of sentence to high-profile terrorist offenders and sex offenders with multiple life sentences; 10% (n = 29) of the sample were on remand.

- -

- Denominationally, the sample predominantly self-identified as ‘Islam, no particular group’ (43%, n = 114) or “Isam, Sunni” (39%, n = 110), with a representation of Salafi Islam (12%, n = 32), Shia (2%, n = 4) or “Islam, other” (2.3%, n = 6)

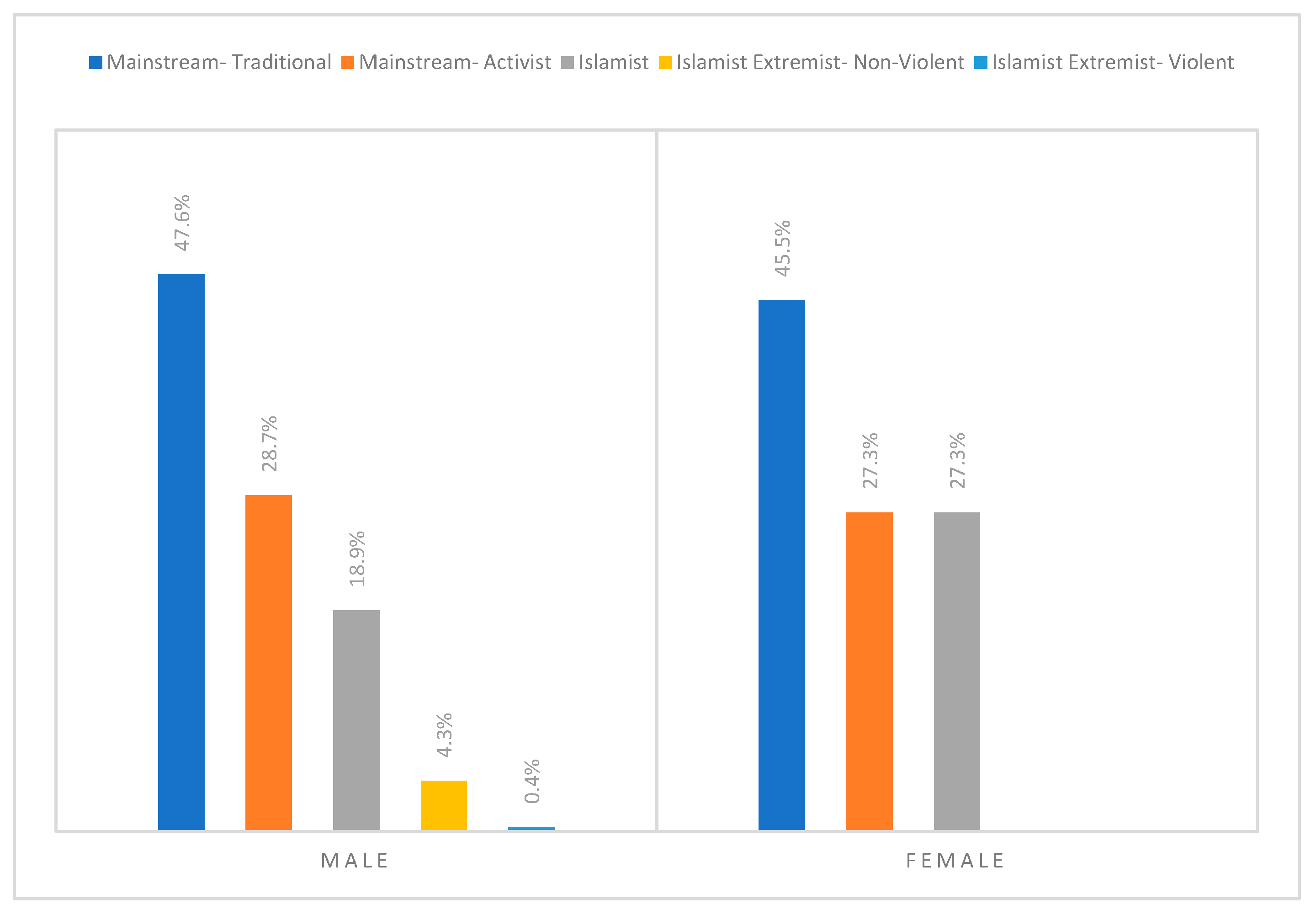

4.2. Religious Worldviews

- 22

- It is part of Islam to treat Muslims more fairly than non-Muslim.”

- 23

- “I avoid prisoners who are not Muslim.”

- 24

- “It is part of Islam to change things that are unfair in society.”

- 25

- “Islam teaches that wisdom can be found in many religions.”

- 26

- “Islam teaches that I must follow the law of this country.”

- 27

- “Islam teaches that the laws of this country should be replaced by Sharia Law.”

- 28

- “Islam teaches me that human life is sacred.”

4.3. The Religious Worldviews of Male and Female Muslim Prisoners Were Similar

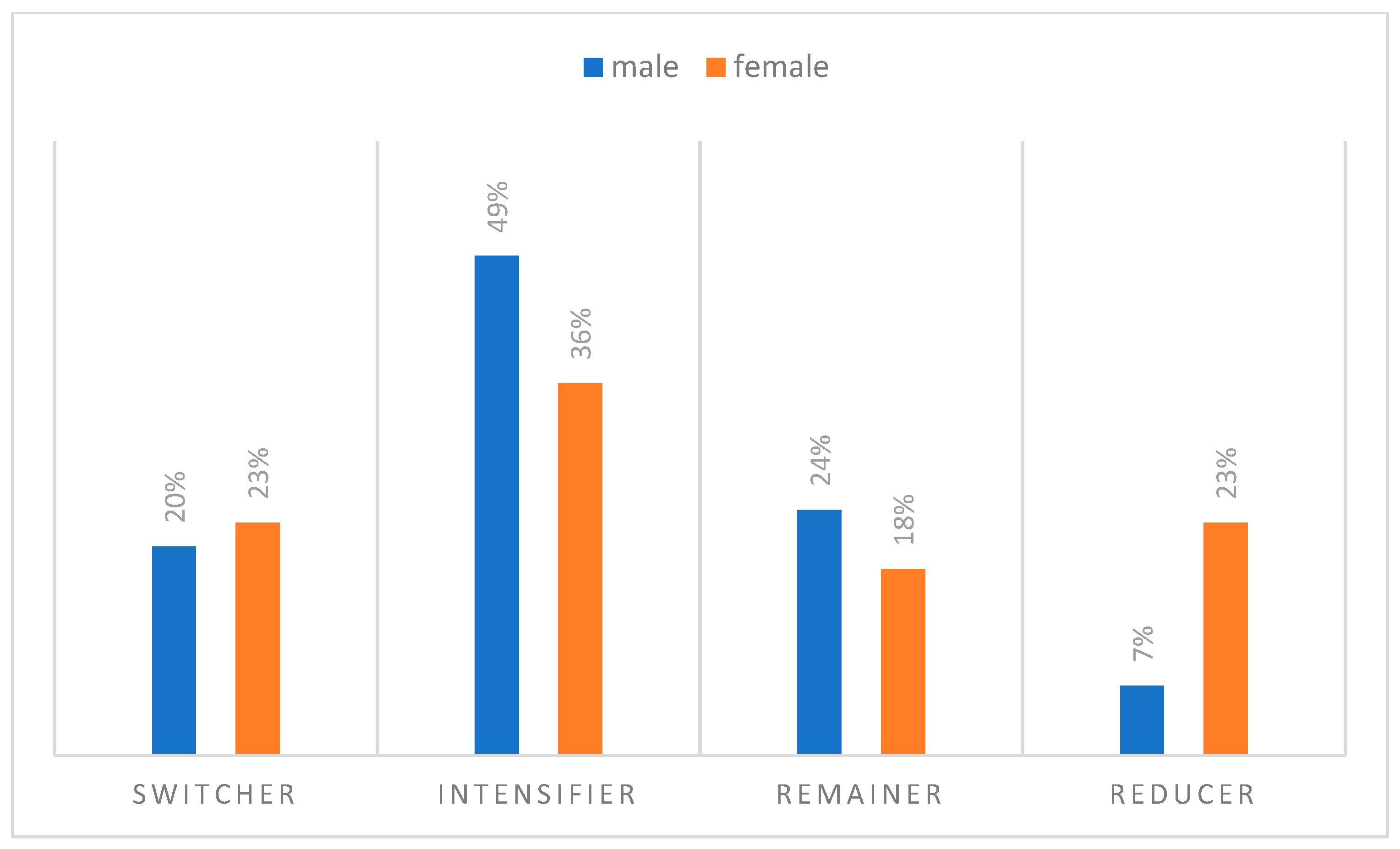

5. Impact of Imprisonment on the Religiosity of Male and Female Muslim Prisoners

- -

- Switching: choosing Islam for the first time from another faith or none, i.e., extra-faith and inter-faith conversion. This was identified though our quantitative data, if they answered “Yes” to Q3: I have changed my religion in prison.

- -

- Intensifying: becoming significantly more devout in terms of participants “strongly agreeing” that their faith was “more important” than before prison and “strongly agreeing” that they were “praying more” in prison, i.e., a form of intra-faith conversion. This was identified though our quantitative data.

- -

- Shifting: undergoing significant changes of Islamic worldview in prison, i.e., a form of intra-faith conversion. This was identified though our qualitative data.

- -

- Reducing: those becoming significantly less devout in prison in terms of participants “strongly disagreeing” that faith was “more important” than before prison and “strongly disagreeing” that they were “praying more” in prison. This was identified though our quantitative data.

- -

- Remaining: unchanging understanding and commitment to Islam in prison. This was identified though our quantitative data.

A Gender Gap in the Prison’s Impact on Religiosity: Men Were Intensifiers; Women Were Reducers

- -

- Islam became (much) more important for 72.2% of male inmates, but for 59.1% of female prisoners;

- -

- while 69.1% of the men said that they prayed a bit more or much more in prison, only 50% of the women said the same;

- -

- While 71% of the men answered that they always fasted in the month of Ramadan, only 29% of the women did so;

- -

- while 3.3% of the men mentioned a diminution in the frequency of prayer and 4.1% said that they did not pray, 22% of the women acknowledged that they prayed less today than when they were free and 13% answered that they did not pray at all.

6. Why Did Prison Have a Different Impact on the Religiosity of Muslim Men and Women Prisoners?

6.1. Religion Was More Important to the Women before Prison

6.2. Prison Was a Place of Religious Deprivation for Women

“I don’t really get the time to pray. Since I’ve been here, I’ve wanted to pray, but I haven’t got time to. It’s like when we clean the cells, I don’t know what happens, but within seconds there is dust all over the floor and I don’t want to pray on a dirty floor (…) and you haven’t got anything to [perform ablution] with, so I had to keep an empty bottle to wash me”.

“I had a lot of time and during my time in my cell obviously I was locked up most of the time, all I could do was just pray and read the Quran and that was just it”.

6.3. The Gendered Impact of the Absence of Family

“That’s when I had to end it with him because, I didn’t think he was much of a family support towards his family with his mum being ill (…) he wasn’t the right man for me, so I ended it with him. It wasn’t working”.

“It’s not a nice place to be (prison), but God can forgive and forget so obviously hopefully God can forgive my sins and see some change for myself. I’ve got children as well who are obviously going to be affected by this. Yes, I’ve got seven”.

“And now I just feel even the girls on my wing they say that they respect me a lot because I am very calm and I’m very wanted when someone arguments with someone I want to sort out the problem for them even I didn’t see this. They tell me that I’ve got, I’m beautiful, I’m beautiful in my heart and I’m beautiful outside, I said ‘oh, this is very nice to hear this’. I always been good person.”(41, White convert, GB)

6.4. The Presence and Absence of High-Status Forms of Gendered Religiosity

“Yeah, I was mosque orderly, and a few months back, someone approached me and said to me, ‘how come there’s other brothers who have more wisdom than you?’ and I said ‘what do you mean by that?’ and they said ‘well, they’re always wearing the... ’ They called it their dress, so obviously they don’t know the name, the thobe [Islamic robe].”

6.5. Intersectional Disadvantage, Trauma and Involvement in Crime

“Yeah, but it was not my fault, I tried to help that guy, even with what he was doing for me, he was trying to rape me this time. He was fighting with me like he fight some boy. Yeah. And they gave me sentence, like life, but I was trying to help the guy.”

“I’ve done sincere tawba [made repentance] for it. If Allah’s forgiven me, Allah’s forgiven me but we both know Allah’s most forgiving. But whether or not I can be forgiven or not. But the things that pretty much bad as well, in a sense of it, and I’ve come back to the crime, I’m in for GBH [Grievous Bodily Harm], Section 18 with intent. I beat up a guy.

6.6. Performing a Collective Religious Identity as a Resource

“they dislike the culture that I am. I will walk around with my headscarf on all the time and people are going to start looking at me and laughing at me (…) I don’t if it’s my paranoia.”(24, mixed race, GB)

“For a start, when I came into prison, I wore the dupatta (a South Asian traditional dress), I kept the dupatta on, at least a scarf round my neck, or I kept the dress. And I have now had to change my style of dress because I don’t want to be judged or be beaten up or treated differently. (…) They’ve (the prison) changed me that I can’t identify in my own religion, because I’ve stopped wearing the stuff. It’s here, underneath my bed. I have the dupatta, I have the clothes, I stopped wearing them because I want to try to fit, which is bad really. Because they take away, they’ve taken away my identity and stripped me from my identity and stripped me from who I am because I’m not accepted anywhere.”(Maya 60, Asian, Intensifier, GB)

6.7. The (in)Adequacy of Chaplaincy Activities

“I thought having my own religion would mean that I could rely on the chaplaincy and on the chaplaincy leaders. But they are rubbish in every sense, they are nonsense. They actually have too much work to do, too much pressure, they’re too overloaded with too much pressure that they actually cannot be bothered. They don’t give you any one-to-one, they don’t treat you as if you matter. It’s like you can just fumble your way through where you’re not really getting the help but you want to be able to concentrate on your own religion because that’s where you think you’ll get the help but you’re not getting it.”

6.8. The Need for Gender-Responsive Chaplaincy

“Yes I do the prayer, I pray five times a day. But at night, I dance, sorry to say that, but I dance, because it empties my head and keep me from falling in depression. So, I dance. I put on some music, and I dance. I don’t care what they say, I pray, and I dance, and I ask God for forgiveness. Nobody but the wardens can see me, so I don’t care, and I dance”.

“Then they asked me to join choir, so I joined the choir because I love to sing. And within this chance, it made me feel free, it made me feel, you know, singing, even though, it don’t matter how I sing. You know, singing songs and praising Allah, even though it’s not in Muslim, but singing songs made me feel Allah. Because I wanted to kill myself in the cell, last year.”

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For details of security categories see: https://prisonjobs.blog.gov.uk/your-a-d-guide-on-prison-categories, accessed on 14 April 2021. |

References

- Aday, Ronald H., Jennifer J. Krabill, and Dayron Deaton-Owens. 2014. Religion in the Lives of Older Women Serving Life in Prison. Journal of Women & Aging 26: 238–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ajouaou, Mohamed, and Ton Bernts. 2015. Imams and Inmates: Is Islamic Prison Chaplaincy in the Netherlands a Case of Religious Adaptation or of Contextualization? International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 28: 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, Nawal H., Robert R. Weaver, and Sam Saxon. 2004. Muslims in Prison: A Case Study from Ohio State Prisons. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 48: 414–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, Louise. 2001. ‘Muslim Brothers, Black Lads, Traditional Asians’: British Muslim Young Men’s Constructions of Race, Religion and Masculinity. Feminism & Psychology 11: 79–105. [Google Scholar]

- Becci, Irene, and Felicia Ghica. 2019. Pratiques et Appartenances Religieuses en Prison: Rapport d’un Enquête Quantitative dans Seize Établissements Pénitentiaires en Suisse. Working paper 14. Lausanne: ISSRC. [Google Scholar]

- Becci, Irene, and Mallory Schneuwly Purdie. 2012. Gendered Religion in Prison? Comparing imprisoned men and women’s expressed religiosity in Switzerland. Women Studies 41: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becci, Irene, Claude Bovay, André Kuhn, Schneuwly Purdie Mallory, Joelle Vuille, and Brigitte Knobel. 2011. Enjeux Sociologiques de la Pluralité Religieuse en Prison [Rapport de Recherche]. Lausanne: École d’études sociales et de la santé. [Google Scholar]

- Becci, Irene. 2012. Imprisoned Religion. Transformation of Religion during and after Imprisonment in Eastern Germany. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Beckford, James A. 2003. Sans l’État pas de transmission de la religion? Le cas de l’Angleterre. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 121: 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckford, James A., Danièle Joly, and Farhad Khosrokhavar. 2007. Les musulmans en prison en Grande-Bretagne et en France. Louvain: Presse Universitaire de Louvain. [Google Scholar]

- Beckford, James A., Sophie Gilliat, and Sophie Gilliat-Ray. 1998. Religion in Prison. Equal Rites in a Multifaith Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Béraud, Céline, and Claire de Galembert. 2019. La Fabrique de L’aumônerie Musulmane en France. Rapport de recherche 217.04.19.06. Paris: Direction de L’administration Pénitentiaire. [Google Scholar]

- Béraud, Céline, Claire de Galembert, and Corinne Rostaing. 2016. De la Religion En prison. Paris: Presses universitaires de Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- Béraud, Céline, Corinne Rostaing, and Claire de Galembert. 2017. Genre et lutte contre la ‘radicalisation’. La gestion sexuée du ‘risque’ religieux en prison. Cahiers du Genre 63: 145–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castel de Bergerac, François. 2020. Rupture jihadiste. Les jeunes femmes de la prison de Fleury-Mérogis. In Les Territoires Conquis de L’islamisme. Paris: PUF, pp. 285–332. [Google Scholar]

- Kimberle, Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller, and Kendall Thomas, eds. 1995. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics and violence against women of color. Standford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Galembert, Claire. 2020. Islam & Prison. Paris: Editions Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Dix-Richardson, Felicia. 2002. Resistance to Conversion to Islam Among African American Women Inmates. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 35: 107–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabretti, Valeria. 2015. Dealing with Religious Differences in Italian Prisons: Relationships Between Institutions and Communities from Misrecognition to Mutual Transformation. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 28: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliat-Ray, Sophie. 2013. Understanding Muslim Chaplaincy. Farnham: Burlington, Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, Mark S. 2009. Prison Islam in the Age of Sacred Terror. The British Journal of Criminology 49: 667–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Sung Joon, Johnson Byron R., Anderson Matthew L., and Booyens Karen. 2019. The Effect of Religion on Emotional Well-Being Among Offenders in Correctional Centers of South Africa: Explanations and Gender Differences. Justice Quarterly, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Robert, and Hans Toch. 1983. The Pains of Imprisonment. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Khosrokhavar, Farhad. 2004. L’islam dans les Prisons. Paris: Balland. [Google Scholar]

- Khosrokhavar, Farhad. 2006. Quand al-Qaïda Parle Derrière les Barreaux. Paris: Grasset. [Google Scholar]

- Khosrokhavar, Farhad. 2016. Prisons de France. Violence, Radicalisation, Déshumanisation: Surveillants et Détenus Parlent. Paris: Robert Laffont. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Ariño, Julia, Gloria García-Romeral, Gemma Ubasart-González, and Mar Griera. 2015. Demonopolisation and dislocation: (Re-)negotiating the place and role of religion in Spanish prisons. Social Compass 62: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheron, Hugo. 2020. Le jihadisme Français: Quartiers, Syrie, Prisons. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, Tom, and Jeff Duncan. 2011. The Sociology of Humanist, Spiritual, and Religious Practice in Prison: Supporting Responsability and Desistance from Crime. Religions 2: 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraishi, Muzammil, and Rob Philburn. 2015. Researching Racism: A Guidebook for Academics and Professional Investigators. Newbury Park: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rhazzali, Khaled. 2016. Religious Care in the Reinvented European Imamate. Muslims and their guides in Italian Prisons. In Religious Diversity in European Prisons. Challenges and Implications for Rehabilitation. Edited by Irene Becci and Olivier Roy. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rostaing, Corinne. 2017. L’invisibilisation des femmes dans les recherches sur la prison. Les cahiers de Framespa, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarg, Rachel, and Anne-Sophie Lamine. 2011. La religion en prison. Norme structurante, réhabilitation de soi, stratégie de résistance. Archives de Science Sociales des Religions 153: 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarg, Rachel. 2016. L’expérience carcérale religieuse des pointeurs ou la recherche du salut. Justice Pénale Internationale, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Rache Zimmer, and Kathryn M. Feltey. 2009. “No Matter What Has Been Done Wrong Can Always Be Redone Right”: Spirituality in the Lives of Imprisoned Battered Women. Violence Against Women 15: 443–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneuwly Purdie, Mallory. 2011. “Silence... Nous sommes en direct avec Allah”. Réflexions sur l’émergence d’un nouveau type d’acteur en contexte carcéral. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 153: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneuwly Purdie, Mallory. 2013. Formating Islam vs. Mobilizing Islam in prison. Evidences from the Swiss case. In Debating Islam. Negociating Religion, Europe and the Self. Edited by Samuel M. Behloul, Suzanne Leuenberger and Andreas Tunger-Zanetti. Bielefeld: Transkript, pp. 98–118. [Google Scholar]

- Schneuwly Purdie, Mallory. 2019. Radicalisation de type jihadiste. Bilan et enjeux dans les prisons suisses. In Etat des Lieux et Évolution de la Radicalisation Djihadiste en Suisse. Edited by Miryam Eser Davolio, Mallory Schneuwly Purdie, Fabien Merz, Johannes Sall and Ayesha Rether. Zürich: ZHAW, pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schneuwly Purdie, Mallory. 2020. Quand l’islam s’exprime en prison. Religiosités réhabilitatrice, résistante et subversive. In Prisons, Prisonniers et Spiritualité. édité par Philippe Desmette et Philippe Martin. Paris: Hémisphères Éditions, pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Siraj, Asifa. 2010. “Because I’m the man! I’m the head”: British married Muslims and the patriarchal family structure. Contemporary Islam 4: 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, Asifa. 2012. ‘Smoothing down ruffled feathers’: The construction of Muslim women’s feminine identities. Journal of Gender Studies 21: 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalek, Basia, and Salah El-Hassan. 2007. Muslim Converts in Prison. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 46: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, Jörg, Judith Könnemann, Mallory Schneuwly Purdie, Thomas Engelberger, and Michaël Krüggeler. 2016. (Un)believing in Modern Society. Religion, Spirituality and Religious-Secular Competition. Ashgate. Farnham: Burlington. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Kuile, Hagar, and Thomas Ehring. 2014. Predictors of changes in religiosity after trauma: Trauma, religiosity, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 6: 353–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzebiatowska, Marta, and Steve Bruce. 2012. Why Are Women More Religious than Men. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Matthew, Lamia Irfan, Muzammil Quraishi, and Mallory Schneuwly Purdie. 2021a. Prison as a site of intense religious change: The example of conversion to Islam. Religions 12: 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Matthew, Lamia Irfan, Muzammil Quraishi, and Mallory Schneuwly Purdie. 2021b. Islam in Prison: Conversion, Extremism and Rehabilitation. Bristol: Bristol University Press, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Matthew. 2019. The Genealogy of Terror: How to distinguish between Islam, Islamism and Islamist Extremism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead, Linda. 2012. Gender Differences in Religious Practice and Significance. Travail, Genre et Société 27: 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crosstabulation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam Teaches That I Must Follow the Law of This Country | ||||||

| I Strongly Disagree | I Mainly Disagree | I Mainly Agree | I Strongly Agree | Total | ||

| Gender | male | 16 | 16 | 67 | 118 | 217 |

| female | 3 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 21 | |

| Total | 19 | 21 | 71 | 127 | 238 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schneuwly Purdie, M.; Irfan, L.; Quraishi, M.; Wilkinson, M. Living Islam in Prison: How Gender Affects the Religious Experiences of Female and Male Offenders. Religions 2021, 12, 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050298

Schneuwly Purdie M, Irfan L, Quraishi M, Wilkinson M. Living Islam in Prison: How Gender Affects the Religious Experiences of Female and Male Offenders. Religions. 2021; 12(5):298. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050298

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchneuwly Purdie, Mallory, Lamia Irfan, Muzammil Quraishi, and Matthew Wilkinson. 2021. "Living Islam in Prison: How Gender Affects the Religious Experiences of Female and Male Offenders" Religions 12, no. 5: 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050298

APA StyleSchneuwly Purdie, M., Irfan, L., Quraishi, M., & Wilkinson, M. (2021). Living Islam in Prison: How Gender Affects the Religious Experiences of Female and Male Offenders. Religions, 12(5), 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050298