1. Introduction

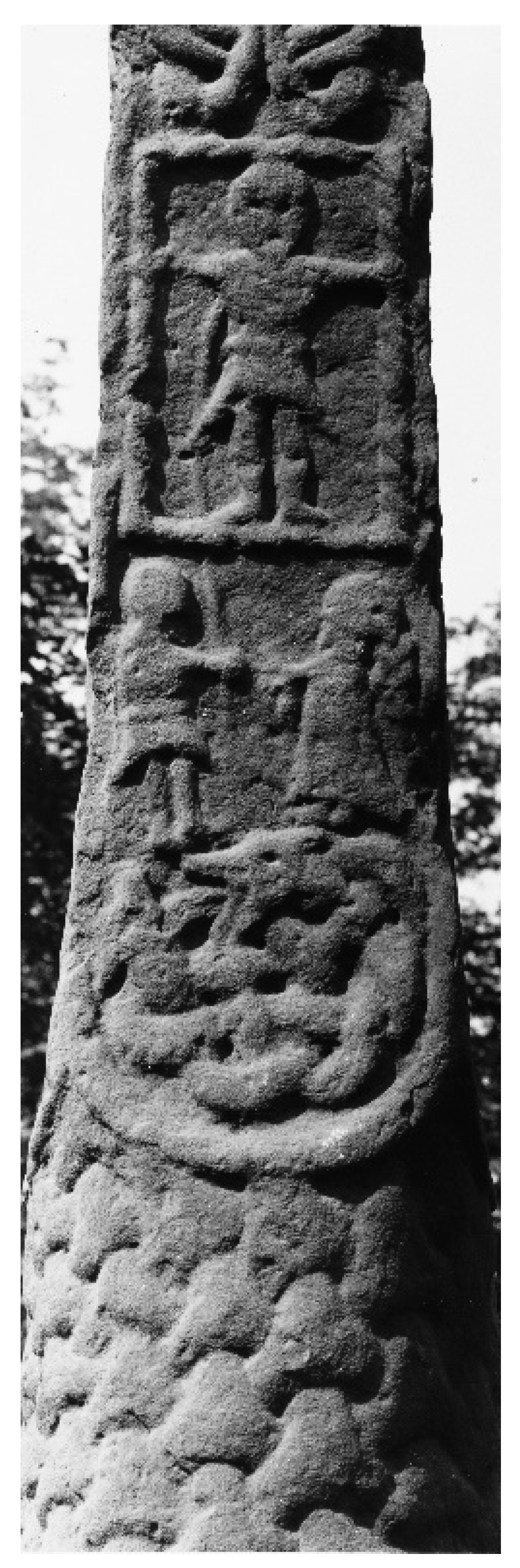

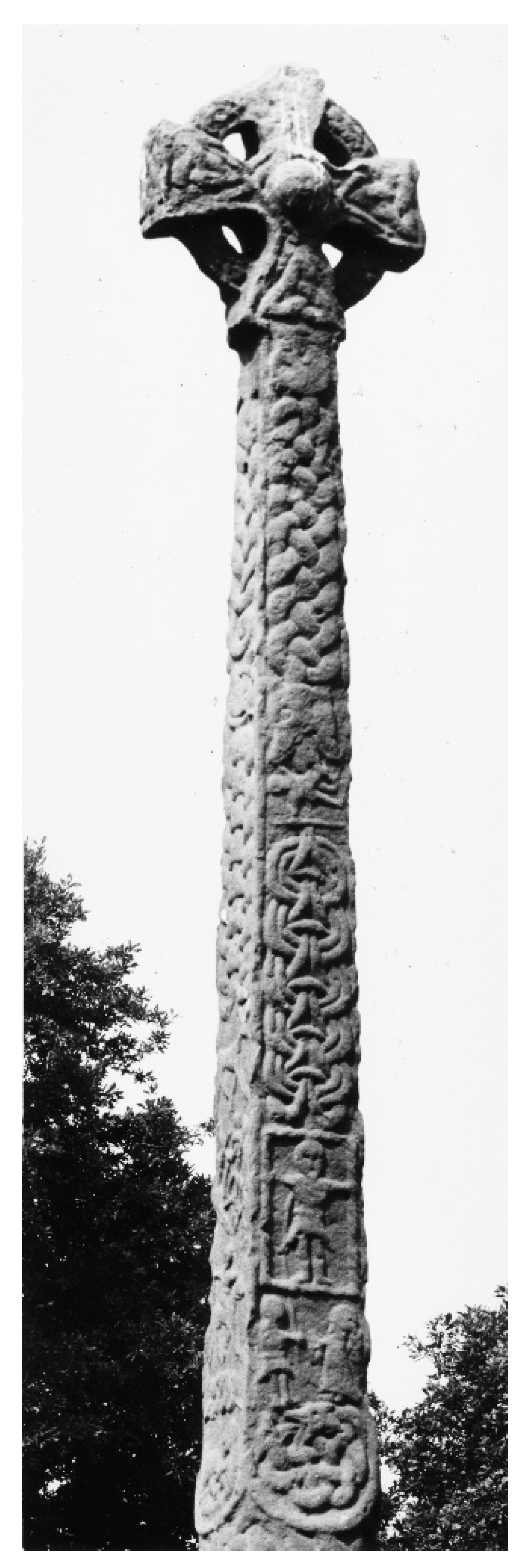

The Gosforth Cross (Cumbria) (

Figure 1) is perhaps one of the most well-known monuments produced in Anglo-Saxon England during the period of Scandinavian settlement in the late ninth and tenth centuries. The apparent Norse mythological nature of its extensive carved figural program has been considered unequivocal, despite its preservation on the monumental form of the cross—

the pre-eminent symbol of Christianity—and the inclusion of at least one overtly Christian subject: namely, the Crucifixion. Given this apparent disparity between the ‘pagan’ and Christian natures of the Gosforth Cross and its carvings, its figural program will be re-assessed here within its monumental context to demonstrate the Christian iconographic import of its carvings.

The complete cross-shaft dates to the first half of the tenth century and belongs to a group of round-shaft derivative crosses found throughout Lancashire, Cheshire, Western Yorkshire and the Peak District of Derbyshire and Staffordshire (

Bailey and Cramp 1988, pp. 101–3). At Gosforth, the lower portion of the cylinder is undecorated, while the upper is encircled by a multiple ring chain. All four faces of the shaft’s upper, rectangular portion are filled with figural carvings depicted on different planes, an arrangement that distinguishes it from the other round-shaft derivative crosses (

Bailey and Cramp 1988, p. 101). The absence of panel divisions to separate the figural schemes contrasts with the pre-Viking (Anglian) convention of displaying figural images within panels, and is understood to reflect Scandinavian artistic conventions paralleled on Gotlandic picture-stones or objects from the Oseberg ship burial, which depict seried narratives without ornamental elements dividing them (

Bailey 1980, p. 79;

Bailey 1996, p. 87). Indeed, the unusual proportions and Scandinavian visual features of the Gosforth Cross were recognized as early as 1883 by William Slater Calverley, who observed that “the general appearance of the cross, at a little distance is that of a gigantic Thor’s hammer” (

Calverley 1883, p. 375)—an observation that elides the cross-form of the monument. Calverley also identified the cross-shaft with the mythological Ash tree Yggdrasil; proposed Scandinavian mythological identifications for each figure carved on the four faces of the cross, including Loki and Sigyn at the base of Face A; and conflated Christ with various members of the Norse pantheon (

Calverley 1883, pp. 377–401).

Since then, with very few exceptions, the figural carvings of the Gosforth Cross have been assumed to represent Norse mythological episodes associated with Ragnarök, based on the mythological accounts preserved in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Old Norse texts produced in Iceland, which post-date the Gosforth Cross by two to three centuries (e.g.,

Calverley 1899, pp. 142–48;

Collingwood 1923, p. 242;

Kendrick 1949, pp. 68–69;

Davidson 1964, pp. 207–8;

Bailey 1980, pp. 125–31;

Bailey and Cramp 1988, pp. 102–3;

Bailey 1996, pp. 88–90;

Kopár 2012, pp. 91–101;

Rekdal 2014, p. 109). Although it is possible that early oral variants of these texts circulated in the Insular world, the temporally, geographically and culturally removed written versions of the myths continue to be invoked to identify the carvings. This approach has led to the Gosforth carvings and those of other monuments being regarded as ‘illustrations’ of the myths and legends recorded by twelfth- and thirteenth-century (Christian) Icelandic authors, rather than significant cultural products in their own right (e.g.,

Calverley 1899, p. 191;

Collingwood 1927, pp. 157, 170;

Kopár 2012, pp. 23–30, 33–41, 90–91). This view of the carvings further diminishes the significance of their monumental contexts, undermines the potential agency of those responsible for selecting the images and erases any potential responses they may have been intended to elicit from their intended tenth-century Anglo-Scandinavian audiences.

Those who have eschewed this scholarly trend, however, have acknowledged both the Christian nature of the monumental form, and that of its iconographic import (

Calverley 1883, p. 375;

Parker and Collingwood 1917, p. 110;

Berg 1958, p. 33;

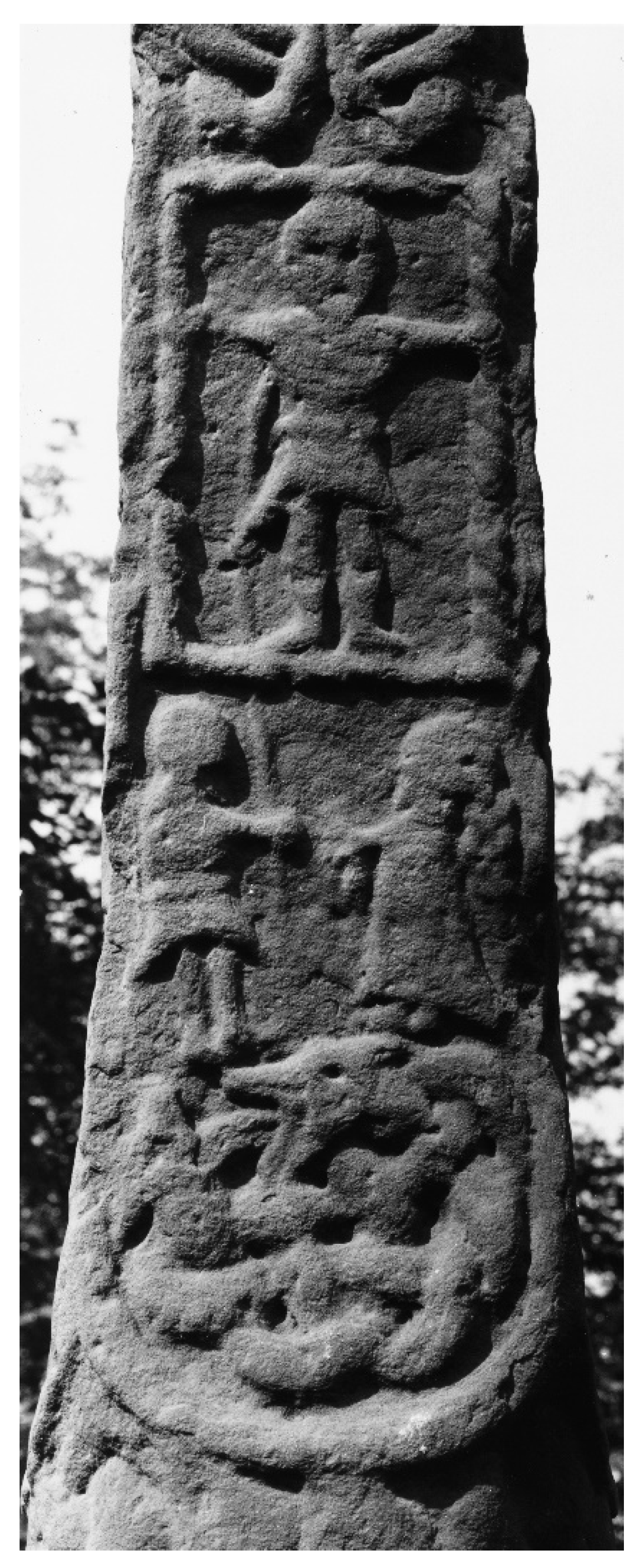

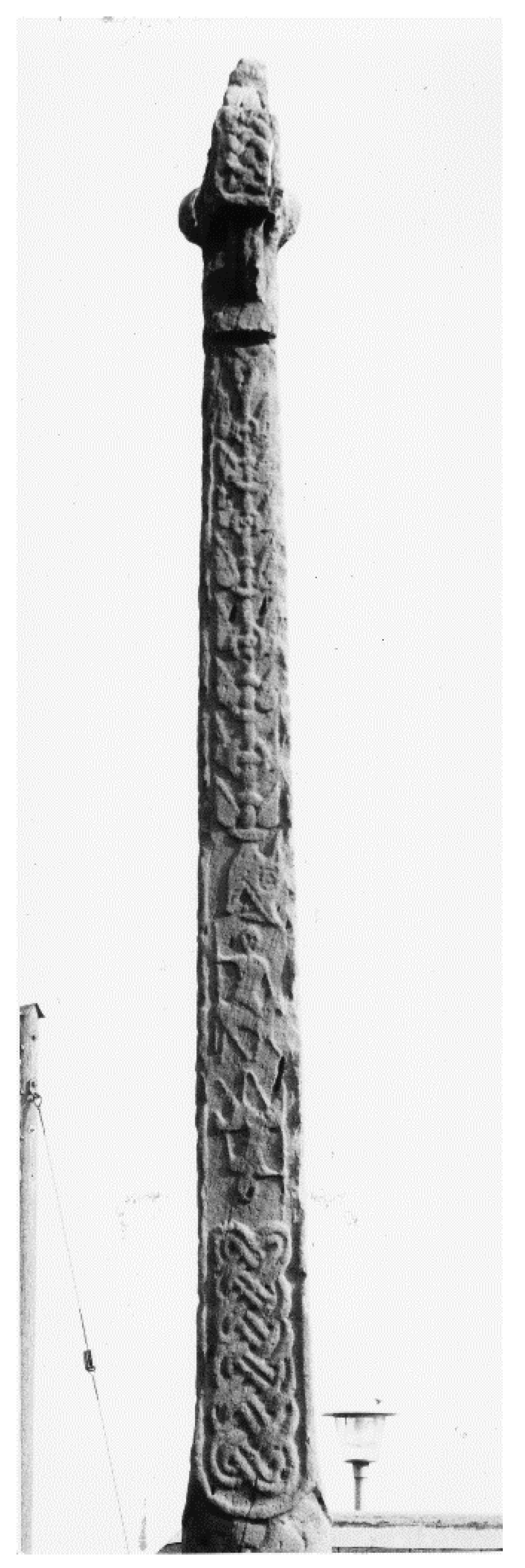

Bailey 2000, pp. 20–22). Significantly, this has enabled the figural scheme depicted at the base of Face C (

Figure 2), originally identified as Odin, Baldr or Heimdallr crucified above the Midgard serpent (

Calverley 1883, pp. 389–92;

Colley March 1891, p. 86;

Calverley 1899, pp. 153–58;

Berg 1958, p. 29), to be re-identified as a rare example of a cross-less Crucifixion, which finds only two extant tenth-century sculptural analogues at Bothal (Northumberland) and Penrith, Cumbria (

Figure 3) (

Parker and Collingwood 1917, p. 105;

Berg 1958, p. 30;

Cramp 1984, pp. 165–66 [Bothal 2];

Bailey 1980, p. 127;

Bailey and Cramp 1988, pp. 101–2 [Gosforth 1], 140–42 [Penrith 11];

Bailey 1996, pp. 87, 89;

Kopár 2012, p. xviii).

Nevertheless, the scholarly preoccupation with the presumed ‘pagan’ nature of the sculptures has persisted, resulting in the perception that the carvings document the religious accommodation and/or acculturation of the incoming Scandinavian settlers (

Kopár 2012, pp. 144–47, 149–53, 163–65). While some of the Gosforth carvings may represent secular subjects, they are also deliberately ambiguous; the conscious choice to display them on a monumental cross suggests that they could express other (Christian) significances—a phenomenon certainly found on contemporary Anglo-Scandinavian monuments, such as the Leeds cross (

Doviak 2020a, pp. 172–77;

2020b, pp. 118–31). Despite the prioritization of the apparently ‘pagan’ carvings at Gosforth, Richard Bailey has highlighted the prominent location of the Crucifixion scheme above the transition from the shaft’s round to square portions, just above head height, making it one of the most visually accessible schemes to early medieval viewers (

Bailey 2000, pp. 20–21).

Given this distinct placement, it is possible to identify numerous unusual features in the Crucifixion scheme that enhance its prominence and underscore the Christian nature of both the scheme and the monument overall. It will be argued here that such features were consciously selected and arranged to express complex (Christian) theological concerns relevant to, and appropriate within, their Anglo-Scandinavian cultural milieu. Although a female figure of Scandinavian type is included, for example, the implications of her potential Christian associations remain relatively understudied (

Berg 1958, pp. 30–32;

Bailey 1980, pp. 130–31;

Bailey 1996, p. 89;

Bailey 2000, pp. 20–21). This discussion will demonstrate that the figure was consciously selected for its potential ambiguity, which was intended to elicit a devotional response from the viewer(s) that involved contemporary interests in the veneration of the cross.

Perhaps even more significant, however, is the ornate, cabled framing device employed to enclose the figure of the Crucified. In the light of the Scandinavian visual conventions used elsewhere on the shaft this frame is anomalous, suggesting that it was consciously invoked to emphasize this figure in a complex arrangement that recalls the format of painted wooden panels: icons. The details of the frame suggest that it was intended as a skeuomorph of the painted panels displayed in contemporary churches, with the implication that this feature would work in tandem with the figures included in the scheme to inspire contemplation and elicit devotional responses, associated with the veneration of the cross and the revelation of Christ’s divine nature from the viewer(s) in a manner analogous to panel paintings. Moreover, the Christian theological concerns expressed by the arrangement of the Crucifixion scheme appear to be complemented by the accompanying (deliberately ambiguous) figural schemes elsewhere on the cross-shaft. It is thus worth reconsidering the potential symbolic significance(s) of the Crucifixion within its monumental context—that of the cross—which was unequivocally associated with Christianity.

2. Icons in Anglo-Saxon England

The Gosforth Crucifixion scheme, located at the base of Face C (East), comprises two confronting, profile human figures situated beneath a third, frontal figure who wears a short, belted kirtle. This figure, identified as Christ based on his cruciform pose, is enclosed by a rectangular frame grasped in his outstretched hands, which protrude in front of it. Below, the figure on the right wears a ponytail hair arrangement and a trailing dress, and holds a curved object in her hands, while that on the left, identified as the spear-bearer Longinus, wears a short kirtle and holds a spear that crosses behind the frame to pierce Christ’s side. Although the scheme was originally considered to derive from Irish models because of the arrangement of Longinus beneath Christ (

Berg 1958, pp. 30–31;

Bailey 1980, p. 130;

Bailey and Cramp 1988, pp. 102–3;

Bailey 2000, p. 20;

Kopár 2012, pp. 94–95), Bailey rejected any such origins on the basis that the scheme contains no explicitly Irish features; rather, he argued that it was adapted for representation according to Scandinavian visual conventions, as suggested by the style and dress of the profile female figure accompanying Longinus (

Bailey 1980, p. 230).

The surrounding frame has been deemed an unusual feature in this context, but given the emphasis on the Scandinavian-style female figure below (

Bailey 1980, pp. 130–31;

Bailey 1996, pp. 87–89;

Kopár 2012, pp. 94–101), the full implications of the decision to include the frame and its intended functions have yet to be considered. The absence of frames elsewhere on the cross-shaft indicates, at the very least, that it was deliberately included to accentuate the figure within. Its ornate cabled decoration, rectangular form and the emphasis on the figure within suggest that this skeuomorphic feature was consciously invoked by those responsible for designing the cross to establish a visual connection with the format of painted icons. Further analysis of the frame demonstrates that it was intended to elicit the viewer’s contemplation of complex Christian theological concerns that were relevant to, and appropriate within, the Anglo-Scandinavian cultural milieu of the cross.

Icons are attested in Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical contexts prior to the late ninth- to tenth-century Scandinavian settlement, suggesting that they could have been encountered by those responsible for the Gosforth Cross. In his homily for Benedict Biscop (Homily I.13), for instance, Bede records that Benedict Biscop brought painted wooden panels depicting biblical subjects (

pincturas sanctarum historiarum) back from Rome that could be displayed “to teach those who looked upon them, inasmuch as those who are not able to read might learn the works of our Lord and saviour through beholding the images themselves” (

et ad instructionem intuentium proponerentur aduexit uidelicet ut qui per litterarum lectionem non possent opera domini et saluatoris nostril per ipsarum contuitum discerent imaginum:

Grocock and Wood 2013, pp. 16–17). While this does not indicate what form the images themselves may have taken, Bede’s account does suggest that their purpose was to elicit understanding of the Lord’s works amongst their viewers.

In his

Historia Abbatam Bede elaborates on the “paintings of holy images” (

picturas imaginum sanctarum), which included “images of the gospel stories” (

imagines euangelicae historiae), by underscoring their intended purpose of inspiring the viewer to recall explicit aspects of salvific history and their own position in that history (

Grocock and Wood 2013, pp. 36–37). Perhaps most significantly, Bede records how Benedict brought back additional images from his fifth journey to Rome that depicted the story of the Lord, as well as a series of paired Old and New Testament images (

Grocock and Wood 2013, pp. 44–45). Among these, one pair “compared the Son of Man raised up on the cross to the serpent raised up by Moses in the desert” (

Item serpenti in heremo a Moyse exaltato, Filium hominis in cruce exaltatum comparauit:

Grocock and Wood 2013, pp. 44–45).

Furthermore, Bede explicitly discusses how painted images were viewed and understood by contemporary audiences in

De Templo when explaining why carved and painted images are appropriate within ecclesiastical and other contexts (

Connolly 1995, pp. 90–92). Perhaps recalling the paired images displayed at Jarrow, Bede argues that if it was permissible for Moses to raise up the brazen serpent, it should be permissible to render images of the crucified Christ, so that his victory over death may “be recalled to the minds of the faithful pictorially” (

domini salutoris in cruce qua mortem uicit ad memoriam fidelibus depingendo reduce:

Hurst 1969, p. 212;

Connolly 1995, p. 91). His justification for this was that, alongside illustrating a living narrative of Christ’s story for those who were textually illiterate, the sight of paintings (understood as living writing;

Nam et pictura …

id est uiua scriptura, uocatur:

Hurst 1969, p. 213) of Christ triumphing over death or performing miracles would elicit compunction (

uel etiam alia eius miracula et sanationes quibus de eodem mortis auctore mirabiliter triumphauit cum horum aspectus multum saepe compunctionis soleat praestare contuentibus:

Hurst 1969, pp. 212–13;

Connolly 1995, p. 91) in the viewer. In the early Church, including Anglo-Saxon England, this was understood to be an interior awakening of awareness which generated contemplation—in this case of suffering caused by sin—though it could be expressed outwardly in the form of tears, and a subsequent desire for reunification with God (

Palmer 2004, pp. 449–50;

Baker 2015, pp. 264–70). Here, Bede makes explicit the associations between the act of viewing, compunction, the emotional response to the image, the action(s) depicted and contemplation: of the viewer’s own place in the history of salvation. In this cultural context, Nicholas Baker has demonstrated that Insular visual stimuli, depicting the consequences of sin or models of correct penitential attitudes, were consciously presented such that that they would elicit compunction in the viewer, often expressed outwardly through tears, enabling them to contemplate the image and adopt an appropriate penitential state (

Baker 2015, pp. 270–71).

Although Bede demonstrates that the painted panels were intended to elicit compunction in the viewer, which would facilitate a state of contemplation that brought them closer to God, the relationship between the painted panels and the monumental stone sculptures produced in this context are not addressed—although Bede does indicate that for him, painted panels were understood to be both wooden and stone (

Connolly 1995, pp. 91–92), and Jane Hawkes has argued that the subjects mentioned by Bede are reflected in those carved on the stone crosses produced by the Wearmouth-Jarrow sculptors (

Hawkes 2007a, pp. 28–30). She has also identified the iconic nature of frontally-disposed single, half or full-length figures carved on Anglian monuments, arguing that such images are analogous to the icons of the early Church and included both single figures as well as narrative schemes such as the Crucifixion (

Hawkes 2018, pp. 17–19;

Hawkes and Sidebottom 2018, pp. 77–78). Among the diagnostic features that designate the iconic nature of such figural carvings, Hawkes has observed that perhaps the most significant indicator of such an image is the presentation of the carved figure within a discrete panel enclosed by a frame, which could be supplemented by applied media such as paint, or glass or paste inset in the deeply drilled eyes of the figures (

Hawkes and Sidebottom 2018, p. 78).

These features demonstrate how painted wooden panels could be recreated in stone, such that the iconic images carved in stone functioned in a manner analogous to their two-dimensional wooden counterparts, by encouraging the viewers to contemplate the images enclosed within their frames. The public nature of the stone monuments corresponds to that of processional icons, which were intended to express the process of prayer visually and emphasize its importance in the process of intercession (

Pentcheva 2006, pp. 112–13). The iconic images of the carved stone panels could be encountered by a range of potential ecclesiastical

and secular audiences, meaning that the arrangement of the panels could inspire a response analogous to that of the processional icons, which would provoke the viewer’s compunction and contemplation, ultimately resulting in prayer. Iconic images continued to be carved on the monuments of Derbyshire and Staffordshire after Scandinavian settlement (

Hawkes and Sidebottom 2018, p. 80), and the deliberate selection and arrangement of the frame that encloses Christ in the Crucifixion scheme suggests this phenomenon was likewise being invoked at Gosforth. The frame makes an important distinction between the Christian and secular or mythological images of the iconographic program, indicating that those responsible for the cross intended to underscore the theological significance of the Crucifixion.

3. Creating an Icon: The Gosforth Crucifixion

As with the painted panels Bede described, carved iconic images were intended to elicit an initial state of compunction that would subsequently enable the viewer to contemplate and understand Christ’s divine nature and the salvation engendered by his sacrifice (

Hawkes and Sidebottom 2018, p. 78). While it is unlikely that the painted images mentioned by Bede provided the precise models for the Gosforth Crucifixion—although their stone counterparts suggested by Hawkes must have been encountered—Bede’s accounts do provide important evidence for how such images were perceived as tools intended to inspire compunction in the viewer, in order to elicit their contemplation of the events depicted.

Moreover, it is likely that those responsible for the Gosforth Cross intended to recreate an experience of viewing analogous to that described by Bede, by framing the carved figure of Christ and isolating it from the remainder of the program. The cabled feature surrounding the Crucifixion would have signified to the viewer that it was intended, at the very least, to be viewed as distinct from the other images, and for some might have recalled the framing devices used in manuscript art as thresholds intended to elicit the viewer’s compunction, enabling their contemplation (

Baker 2015, pp. 270–74); the decision to frame Christ is also in keeping with the pre-Viking tradition of depicting iconic images on stone monuments accessible to Scandinavian settlers. At Gosforth, the iconic nature of the Crucifixion is dependent on how the frame functions both within the scheme and the monument overall.

Icons were fundamentally perceived as any image or portrait depicting a single figure, whose isolation enabled it to be viewed and understood in a particular way, and Hans Belting has argued that although portrait-type images outranked narrative ones in Christian visual history, the icon-portrait derived its power from the previous existence of a historical person involved in specific narrative events (

Belting 1994, pp. 10, 47). The tension between portrait-icon and narrative image is evident in the Gosforth Crucifixion, where Christ is presented within a narrative scheme that includes Longinus, whose presence references the historical event of Christ’s death. Yet, the frame dividing Christ from the remainder of this scheme presents his image as a portrait to be venerated, rendering the scheme at once both an image of a historical event and an icon-portrait of the crucified Christ. The act of confining Christ to the frame at Gosforth facilitates an understanding of the figure as an isolated portrayal intended to be encountered in a specific manner. Furthermore, icons contained images of the sacred that were distinguished from representations of secular subject-matter because they were intended to be venerated, a distinction that was underscored by the disposition of the depicted figures who were shown in frontal, static poses, demanding veneration from the viewer (

Belting 1994, pp. 78–80). By separating the Crucifixion from the remainder of the carvings at Gosforth, the frame designates the scheme as an icon and signifies to the viewer that this is an image to be venerated. This is reinforced by the frontal, fixed arrangement of the figure within, a disposition unique on the cross, where all other figures are shown in profile.

The perceived importance of icon frames lay in their provision of points of access that rendered the depicted holy person present, a function that differs radically from that of modern frames, which enclose a space to separate it from the viewer, thereby creating a sense of distance that emphasizes the absence of the object or scene depicted (

Peers 2004, p. 2). Conversely, the framed icon engenders an interaction between viewer and object that is activated by the viewer’s gaze (

Pentcheva 2010, p. 5), enabling the depicted object or person to emerge beyond the frame into the space inhabited by the viewer. As a visual point of reference, the frame enclosing the Gosforth Crucifixion signifies to the viewer the image is intended to be encountered as an icon, simultaneously removing Christ from the viewer while also bringing him closer to the space they inhabit. Certain features and their arrangement within the scheme express the tension between Christ’s absence and presence for the viewer, as well as visually invoking his dual nature as a historical person (in the act of being crucified) and divine being who grasps the frame and so protrudes from it.

These considerations are enhanced by the decision to select the cross as the monument form for display; this implies at least nominal familiarity with the Crucifixion, if not a thorough understanding of its theological significances, and further suggests that the carvings were intended to carry Christian meanings appropriate to the monument form within the context of the conversion and Christianization of the Scandinavian settlers (

Abrams 1997;

Fletcher 1997, pp. 370–71;

Abrams 2000;

Abrams 2001;

Downham 2007, p. 34;

Abrams 2010;

Downham 2012, pp. 24–34;

Edmonds 2019, pp. 132–34). While the Christian origins of the monumental form have certainly been recognized (

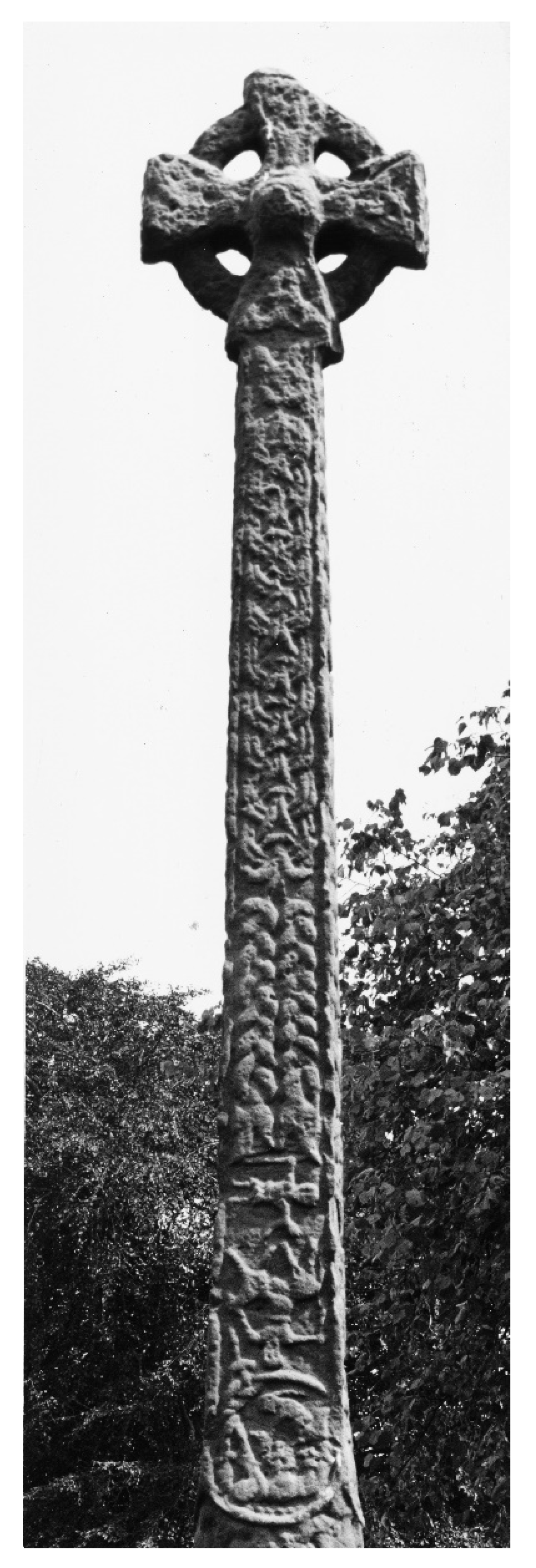

Berg 1958, pp. 32–34;

Bailey 2000, pp. 21–22), the particular elements selected and combined to form it have not been fully explored. Despite Calverley’s (erroneous) comparison of the Gosforth Cross to a gigantic Thor’s hammer, its great height (4.42 m;

Bailey and Cramp 1988, p. 100) and the slender proportions of the shaft render its cross-head visible from great distances. Furthermore, the protruding central boss (

Figure 4) and the four arms of the cross-head that extend beyond the wheel encircling them emulate the architectural profile of contemporary metal jewelry, and so point, in a visually familiar ‘language’, to the value invested metaphorically and physically/economically in the cross, suggesting that the form of the cross-head was deliberately selected to emphasize this connection.

Alongside these associations, other elements of the Gosforth Cross elicit connections with sites of Christian historical significance, which would have been apparent to those who encountered it in situ. Bailey has suggested that the location of Gosforth at the north-south crossing of a marshy plain may have been one of strategic importance (

Bailey 1980, p. 215). This has significant implications for how the cross might have been accessed and viewed when originally erected, in what is presumed to be its original stepped base (

Figure 5) (

Bailey and Cramp 1988, p. 100). This distinctive form has its counterparts elsewhere in the Insular world (

Roe 1965, pp. 220–24;

Werner 1990, pp. 100–6), but other choices such as a plain or rough-cut rectangular or square socle were available, suggesting that the stepped form was deliberately incorporated as a result of direct encounters with analogous monuments elsewhere, or through second-hand knowledge gained from those familiar with such monuments. Stepped bases are generally accepted as symbolic of the marble steps leading up to Golgotha (

Roe 1965, p. 220;

Fisher 2005, p. 86), implying that the Gosforth Cross was intended to recall Golgotha, and by extension, the Cross of the Crucifixion. This explicit reference suggests that the Gosforth monument’s designers expected its anticipated audience to understand the theological significance of Golgotha and the event signified by its base. The associations made explicit through the selection of the various forms of the monument’s component parts are reinforced and complemented by the Crucifixion scene carved on C.

As noted, this scheme is deliberately arranged to reference the historical moment of Christ’s death, as demonstrated by his cruciform pose, directly invoking his sacrifice on the cross, despite its absence. It may well have been deemed unnecessary, given the display of the scheme on a monumental cross whose typological features explicitly reference Golgotha, the historical setting of Christ’s Crucifixion; yet, the carved scene is distinguished from a purely historical narrative image by the exclusion of the cross, the instrument of Christ’s sacrifice, while the frame emphasizes Christ and removes him from the historical narrative and the discomforts he suffered in death in order to express his triumph. This would be entirely in keeping with the general trend of medieval art to collapse linear time in order to present historical moments, particularly those experienced by Christ, while simultaneously imparting his divinity into the present experienced by the viewer, and anticipating his future roles in salvific history (

Belting 1994, pp. 10–11). Furthermore, Christ’s death was understood as the essential condition of his victory, which would enable the subsequent reunification of the faithful with God at the Parousia (

Chazelle 2001, p. 164). The Gosforth Crucifixion depicts the precise moment that Longinus pierces Christ’s side, an event that occurred when Christ was already dead (John 19: 33–34), suggesting that he was deliberately arranged in a cruciform pose to reference the instrument of his death, while being presented

after his death to emphasize his triumph on the cross, and his role as the means to of salvation.

These nuanced distinctions are reinforced by the figural type selected for inclusion in the scheme, which shows Christ frontally, with open eyes and arms extended straight out to the side, an arrangement typical of early medieval Crucifixion schemes from the early fifth century, as evinced by an ivory panel dated.

c. 420–430, depicting this figural type (

Figure 6) (London, British Museum, 1856,0623.5). This type, depicting the living Christ, remained common through the ninth and tenth centuries in western Europe, including the Insular world, and further emphasized Christ’s wounds in an arrangement intended to celebrate Christ as victor over death. Although some Carolingian examples begin to show Christ with his head tilted to one side (

Hawkes 2018, p. 1;

Schiller 1972, pp. 104–5), and a late eighth-century example from Rothbury (Northumberland) depicts Christ with slightly drooping arms (

Cramp 1984, pp. 217–21;

Hawkes 1996, pp. 77–80), the figural type accentuating his suffering does not become commonplace in western European art until after the late eleventh century and indeed the straight-armed type continued to be produced in areas of southern England into the early eleventh century despite continental contacts, as demonstrated by an ivory Crucifixion panel of that date (

Figure 7) (London, British Museum, 1887,1025.14;

Hawkes 2018, p. 1;

Schiller 1972, pp. 142–44). The frontal arrangement of the Gosforth Christ and emphasis on the blood pouring from his side thus demonstrate that the figural type selected for the scheme was indeed intended to emphasize the victorious nature of Christ’s salvific death. Moreover, the conscious choice to include Longinus in the act of piercing Christ’s side anticipates Christ’s Second Coming, when it was said that they who pierced Christ shall look upon him (

Ecce venit cum nubibus, et videbit eum omnis oculus, et qui eum pupgerunt. Et plangent se super eum omnes tribus terrae. Etiam: amen: Revelation 1:7). By depicting Christ in a cruciform pose, accompanied by Longinus piercing his side to reference his death on the cross, while his open eyes convey that he was alive and victorious over death, the scheme thus reveals, in an abbreviated form, that humanity’s eternal salvation was dependent upon Christ’s suffering and sacrifice.

The frame surrounding the Gosforth Crucifixion facilitates further references to the collapse of Christ’s historical past with future salvific events: namely, his Second Coming. Although Lilla Kopár considered the iconography of the Gosforth Cross to fuse Christian and Norse eschatological events outside linear time (

Kopár 2012, pp. 93–104), she did not consider how this collapse brought Christian past and future into the viewer’s present, nor how this was enabled by the frame of the Crucifixion scheme. As demonstrated, this could dictate the viewer’s response by encouraging them to view the scheme as an icon, eliciting their compunction, which in turn would enable them to contemplate the significances underpinning the image, with the expectation that this would subsequently inspire prayer, bringing the viewer closer to the divine. As James Palmer has argued, the acknowledgement of sin and fear of judgment were considered critical to compunction (

Palmer 2004, p. 456). These elements appear to have further bearing on the significance of the Gosforth Crucifixion.

The cabled frame coalesces with, and is broken by, the extreme edges of Christ’s body: his hands and feet. These points of contact and projection, created between the frame and Christ’s cruciform pose, anticipate the eschaton. They are evident in the way the cabled frame is broken by Christ’s hands that protrude beyond the frame to grasp it, and his right foot, which steps beyond it. These features recall the Christ in Majesty depicted on the

c. 800 Last Judgment ivory (

Figure 8), held at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, whose arms are held aloft and extend beyond the edges of the mandorla surrounding him, while his right foot likewise extends past the lower confines of the lozenge. On the ivory, these features are combined to reference Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, his Resurrection and the moment of Parousia signifying the Second Coming, as well as the temporal and spatial collapse at the Last Judgment (

O’Reilly 1998, pp. 77–94;

Luiselli Fadda 2007, pp. 155–62;

Boulton 2013, pp. 288–89;

Gannon 2013, pp. 294–97).

An analogous arrangement was likely intended at Gosforth, as indicated by the frame, but here, these associations are further elucidated by Christ’s cruciform posture, directly invoking the most significant moment in the Christian history of salvation: that of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. The frame surrounds Christ but does not entirely contain him, anticipating his return and enabling him to be viewed simultaneously within two worlds: that of the human, implied by the paired figures below and the spear held by Longinus, which intersects the frame, and the divine world, which is expressed by the frame separating Christ from the other figures carved on the cross, but which is yet unable to contain him. Christ’s posture and his emergence from the frame thus make explicit to the viewer that the Crucifixion was the event that enabled the Second Coming. In turn, the projection of his limbs suggests that both events should be viewed as facilitating the destruction of evil, an association further implied by the human figure confronting the serpent above.

In the context of this public monument, the frame signifies to its intended audiences (ecclesiastical or secular) the iconic nature of the scheme and highlights Christ’s pose, in turn conveying the intended symbolic significance of Christ’s sacrifice as the instrument of salvation, in order to elicit a devotional response from the viewer. It is clear that the frames of early medieval icons functioned as dynamic, interactive areas that could collapse or diminish the space between the viewer and the framed object of devotion, enabling the devotional object to enter the space before it that was inhabited by the viewer, thereby increasing its sacred presence (

Peers 2004, pp. 5–6;

Pentcheva 2010, p. 5). At first glance, Christ in the Gosforth Crucifixion appears to be enclosed and contained within the cabled frame, his removal from the space occupied by the viewer visually elucidating the inaccessible, immaterial nature of his divinity. Yet, his grasp of the vertical edges of the frame and his protruding right foot establish his emergence from its confines, creating the illusion of his corporeal presence in the ‘real’ space of the viewer. These features and the iconic nature of the image thus work in tandem to elicit the viewer’s compunction, inspiring their contemplation and prayer.

In short, the frame functions as a threshold, the projection of Christ’s limbs beyond its confines enabling him to enter the space occupied by the beholder, making his sacred presence a part of the viewer’s reality. This breakdown of spatial distinctions could only be activated by the viewer’s gaze and the unusual arrangement of its features, which were intended to stimulate compunction, in turn prompting contemplation that would induce prayer. The iconic format of the image, Christ’s cruciform pose, the inclusion of Longinus and the stepped base selected for the monument itself collapse the ‘real’ space occupied by the viewer with that of the sacred Christian past, thus enabling them to become an active participant in that salvific history. Consequently, the iconic nature of the image invoked the immaterial space associated with Christ’s death and his anticipated future return, in order to underscore the tripartite role of the cross as the implement of Christ’s death and triumph, and as the instrument of humanity’s salvation: concerns that were emphasized in contemporary liturgical ceremonies.

4. Attitudes of Adoratio: Viewing the Gosforth Crucifixion

Indeed, the iconic arrangement and cruciform pose of Christ have significant implications for how the image would have been viewed and understood by contemporary audiences: as an icon in stone, intended to invoke contemporary Christian theological concepts associated with the veneration of the cross, which were relevant within the wider cultural context of Anglo-Scandinavian England. While Bede’s accounts of the painted panels at Jarrow, and particularly his example of the crucified Christ and his victory over death, demonstrate that such images were intended to inspire the viewer’s compunction and contemplation, as a primarily interior experience intended to facilitate understanding of Christ’s divinity and the salvation enabled by his sacrifice on the cross, such concerns were also prevalent at the time the Gosforth Cross was erected as they formed a significant part of the liturgy performed in Anglo-Saxon England.

From the mid-ninth century, the liturgical ceremony of the

Adoratio crucis emphasized the

inner vision of the Crucified, as set out in scriptural references associated with the witness of Christ’s Second Coming and the Final Resurrection of the Dead (

Chazelle 2001, pp. 296–98). These may well explain the arrangement of the Gosforth Crucifixion, given its presentation of the crucified Christ as an icon translated to stone, but they may also explain the decision to include the apparently anomalous female figure depicted beneath Christ.

The

Adoratio was performed from at least the eighth century as part of the liturgy of Holy Week, where it was celebrated on Good Friday (

Bedingfield 2002, p. 123). It is preserved in the tenth-century

Regularis Concordia (London, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius A III), which, although produced in an Anglo-Saxon monastic context, records lay participation in the ritual and includes Old English Glosses, underscoring its significance in the liturgical calendar and pointing to vernacular interest (

Bedingfield 2002, pp. 126–32). The

Adoratio as performed in Anglo-Saxon England included a ritual elevation and unveiling of the cross, accompanied by prayers that drew attention to Christ’s presence upon it (

Bedingfield 2002, pp. 127–28). Furthermore, it shared features with earlier liturgical ceremonies, the

Exaltatio and

Inventio crucis, which were celebrated in the region from at least the early to mid-eighth century, and are referenced visually in the iconography of the Ruthwell Cross (Dumfriesshire) (

Carragáin 2005, p. 180). The readings for the

Exaltatio crucis (14 September) likewise made explicit connections between the cross, Christ and his victory, while also emphasizing Christ’s elevation on the cross as the means of liberating humanity from sin (

Carragáin 2005, pp. 190–92).

These liturgical celebrations all emphasized the veneration of the cross, a concept that continued to be expressed visually on ninth-century Anglo-Saxon crosses, as at Bakewell and Bradbourne (Derbyshire). Beneath the Crucifixion depicted on Face A of the cross-head of the Bakewell monument, two standing figures in the panel below gaze upward at the cross in an attitude of veneration (

Figure 9a). Hawkes has argued that this arrangement visually references the

Adoratio crucis, further emphasizing the relationships between sight and witnessing the Crucifixion, sight being the necessary faculty to facilitate contemplation (

Hawkes 2007b, pp. 438–48;

2018, pp. 11–16;

Hawkes and Sidebottom 2018, pp. 79, 105–13 [Bakewell 1]). An analogous arrangement is found at Bradbourne, where the Crucifixion is depicted in an iconic format at the base of Face A (

Figure 9b), a setting that would have been eye level for a viewer kneeling before the cross. Hawkes has identified this posture as the ritual attitude of

adoratio adopted in the ninth-century liturgical celebration, and has demonstrated that iconic arrangement and placement of the Crucifixion at the base of the cross would enable the viewer to participate in the event by becoming a witness to it (

Hawkes 2018, pp. 10–11;

Hawkes and Sidebottom 2018, pp. 79, 179–83 [Bradbourne 1]).

These sculptural precedents, which remained visible in the region settled by Scandinavians in the later ninth and tenth centuries, suggest that the Gosforth Crucifixion, too, was deliberately depicted at eye level and in an iconic format to elicit a devotional response from the viewer. Bailey has argued that the position of the Gosforth Crucifixion is unusual for tenth-century Northumbrian sculptures, Crucifixions generally being situated higher on the shaft or in the cross-head, but notably observed that the eye-level position at Gosforth demands the attention of the viewer (

Bailey 2000, p. 20). Yet, the Bradbourne example provides a precedent for placing such an image at the base of the cross-shaft, a trend that continued into the late ninth to tenth centuries, as demonstrated by the Crucifixion scheme at the base of Face C (

Figure 10) on the late ninth-/tenth-century fragmentary cross-shaft at Nunburnholme (Yorkshire).

The schemes on this cross are all arranged within individual panels according to Anglian visual conventions, but arguably, the most distinctive feature of the Crucifixion scheme is the pair of seated or crouching diminutive figures that flank the carved cross. They do not carry attributes, suggesting that they are deliberately ambiguous, while their grasp of the cross and gaze at the figure upon it imply an attitude of adoration. The arrangement was likely intended to elicit an analogous devotional response from the viewer, who, standing or kneeling before the cross-shaft, could contemplate the significance of the Crucifixion panel, the event it depicted and its place in the Christian history of salvation (

Doviak 2020a, pp. 171–72;

Doviak 2020b, pp. 187–89, 193–200). In the light of these sculptural antecedents, the placement of the Gosforth Crucifixion and the deliberately ambiguous figure it includes (

Figure 11) appear to be well in keeping with coeval visual presentations of theological concepts involving the veneration of the cross.

Indeed, the associations between Christ’s Crucifixion and the cross as the instruments of Christ’s victory over death emphasized in the

Adoratio and

Exaltatio crucis may go some way to explaining the Gosforth patrons’ decision to include the female figure depicted beside Longinus, beneath the crucified Christ. Before analyzing this potential connection, however, it is worth reviewing the identifications that have been assigned to this figure, given that its potential Scandinavian visual associations and mythological identity have dominated discussions of the scheme (

Calverley 1883, p. 397;

Parker and Collingwood 1917, p. 105;

Collingwood 1927, pp. 104–5;

Bailey 1980, p. 130;

Kopár 2012, pp. 98–101, 133).

Most recently, Kopár has proposed that the figure should be interpreted as a Valkyrie receiving a victorious warrior into Valhalla because she carries a horn and the scheme apparently articulates details preserved in twelfth-century Icelandic texts describing Odin or Odinic sacrifices, though only one of Kopár’s suggested parallels is relevant here: the spearing of the hero (

Kopár 2012, pp. 95–101). Moreover, she argued that the female figure, viewed as a Valkyrie, was a symbol of death and mortality, potentially associated with the mythological figure of Hel (

Kopár 2012, pp. 98–101, 133), despite the figure lacking any attributes definitively associated with Hel. Although the woman’s hairstyle, garments and horn attribute derive from Scandinavian models, they do not necessarily imply that she carries Norse mythological significance. The horn may simply be a female gender signifier, for example, as alcohol production was one of numerous domestic duties undertaken by early medieval women (

Jewell 2007, p. 57). Indeed, Judith Jesch has suggested that serving food and drink was the only parallel between mythological Valkyries and real Viking-age women (

Jesch 1991, p. 127), indicating that the vessel carried by the figure may represent any food or drink vessel, rather than one explicitly associated with Valhalla. It seems likely, therefore, that she was depicted within contemporary Scandinavian visual conventions to differentiate her from Longinus and Christ, and to ensure that she would be recognized as female by contemporary viewers.

Her inclusion in the only overtly Christian scene on the shaft nevertheless implies that she was intended to be viewed and understood within Christian frames of reference, rather than as a Norse mythological figure inserted into the historical narrative of the Crucifixion. If intended to represent a Valkyrie welcoming a slain warrior to Valhalla, it is more likely that she would have been depicted confronting Christ, as on the Gotlandic picture-stones. While this arrangement may have been prevented by the narrow proportions of the cross-shaft, the sculptor did manage to include Sigyn on the same spatial planes as Loki and the serpent in the scheme depicted on A. This indicates that the female figure in the Crucifixion scheme was deliberately depicted on a separate plane from Christ, which is further reinforced by her position beyond the frame.

Thus, while the figural type used to depict the woman may have originated in Scandinavia and carried particular (but now lost) symbolic meanings associated with Scandinavian traditional mores, its insertion into the central Christian narrative represented on a monumental cross recontextualizes it and instils it with new symbolic significance(s). Potential Christian associations of the figure have certainly been observed (

Berg 1958, pp. 30–32;

Bailey 1980, pp. 130–31;

Bailey 2000, pp. 20–21), although her precise identity remains elusive. She was originally identified as (a Scandinavianised) Ecclesia collecting the blood of Christ in an arrangement derived from continental models, though Berg observed that the omission of Synagoga is unusual because the two are generally paired to express the triumph of the New Covenant over the Old (

Berg 1958, pp. 30–32). While this omission may also be attributed to the narrow proportions of the cross-shaft, if the serpents below the woman and Longinus had been excluded, there would have been enough space to include both Stephaton and/or Synagoga, implying that if the female figure indeed represented Ecclesia, Synagoga was deliberately omitted.

Furthermore, these allegorical figures, which began to be depicted from

c. 830, were also identifiable by their typical arrangement to either side of the cross with Ecclesia on Christ’s right, facing him and Synagoga on the left, facing away from the cross (

Schiller 1972, pp. 110–13). Although the Gosforth woman faces the cross, she is situated to Christ’s left, and given her position on the ‘wrong’ side of Christ it seems unlikely that she was intended to represent Ecclesia, but this does not preclude the possibility that she carried Christian associations. Indeed, Bailey has suggested that her position indicates she should be identified as Mary Magdalene carrying her alabastron, an appropriate counterpart to Longinus, with both figures symbolizing the converted heathen and the recognition of Christ’s divinity (

Bailey 1980, pp. 130–31;

Bailey 2000 pp. 20–21).

The Gosforth figure may also be viewed alongside other images of horn-bearing figures produced in Insular Christian contexts. Several examples occur in Old and New Testament scenes, but Carol Neumann de Vegvar has identified only two that accompany Crucifixion scenes: on Muiredach’s Cross, Monasterboice (Louth) and the Durrow Cross (Offaly). These schemes portray the denial of Peter with the horns symbolizing Peter’s weakness, although the scriptural accounts do not refer explicitly to feasting or drinking (

Neuman de Vegvar 2003, pp. 237–40). Being female, the Gosforth figure is unlikely to denote the denial of Peter, but the arrangement of other Insular figures carrying analogous attributes adjacent to the Crucifixion scenes nevertheless suggests a precedent, while her presentation according to Scandinavian conventions implies that this more readily signified her gender to contemporary audiences, despite her ambiguity.

Here, liturgical uses of horns may be relevant to understanding how this figure was viewed and understood by contemporary audiences. Although never used as chalices for performing the mass in the Anglo-Saxon Church, horns were used in services for the ordination of minor orders by the late tenth century, as recorded in Old English glosses to the late tenth- or eleventh-century Anderson Pontifical (London, British Library, Add. MS 577337;

Neuman de Vegvar 2003, p. 249). They are likewise mentioned in Anglo-Saxon hagiographies for dispensing consecrated liquids, such as water, among the catechumens, and in later medieval texts they are recorded as containers for the oil blessed by bishops and used for various anointings (

Neuman de Vegvar 2003, pp. 249–50). This range of uses demonstrates how contemporary Christian audiences may have interpreted the horn carried by the female figure at Gosforth.

This means that, first, it is unlikely she would have been interpreted as Ecclesia, for this allegorical figure is associated with the Eucharist, thus representing the liturgical ceremony from which horns were apparently excluded. Second, the liturgical use of horns as vessels for consecrated liquids supports Bailey’s suggestion that the Gosforth figure could have been viewed by contemporary audiences as representing Mary Magdalene with her alabastron, understood to signify the converted Christian. This would also explain her depiction alongside Longinus, another formerly non-Christian figure, beyond the frame enclosing Christ, suggesting at the very least, that the pair would be appropriate and relevant iconographic choices to include in a Crucifixion scheme, given the ongoing conversion and Christianization of incoming Scandinavian groups during the late ninth and tenth centuries, who likely formed the intended audience for this monument, as indicated by the selection of a traditional Scandinavian female figural-type.

Furthermore, such associations involving the phenomena of conversion and Christianization seem to be supported by other horn-bearing figures in Anglo-Saxon art. In late Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, horns are consistently depicted as attributes of figures who appear in negative contexts as symbols of

vanitas or to indicate that the figures are pre-Christian sinners (

Neuman de Vegvar 2003, pp. 241–44). Longinus was associated with (Roman) traditional beliefs until his apparent conversion after the Crucifixion (John 19: 34–37; Mark 15: 39–40; Matthew 27: 54; Luke 23: 47). It appears that the Gosforth sculptors used the framing device to communicate to contemporary audiences that, although these three figures belong to the same narrative moment, the lower pair are distinct from Christ and, by extension, were to be associated with traditional beliefs, initially excluding them from the salvation facilitated by Christ’s sacrifice. The absence of any feature dividing the pair from the serpent-like creature below may have further alluded to their previous associations. Moreover, Bailey has recognized that Longinus also symbolized the recognition of Christ, an association reinforced by an apocryphal tale in which Christ’s blood flowed into his eyes, literally opening them, and he has argued that the flow of blood depicted at Gosforth references this moment (

Bailey 1996, p. 89;

Bailey 2000, p. 21).

This suggests that sight and the theme of recognition were the crucial components linking the iconic image Christ with the two figures arranged below, particularly that of the ambiguous female figure. At Gosforth, the ancillary figures confront each other and face Christ, thus forming an additional frame for Christ in which their heads direct the viewer’s gaze to Christ’s crucified form. Ambiguous figures or donor images depicted on icons featuring the Crucifixion performed an analogous function by denoting the manner in which the beholder should view both the represented cross, and the cross-shaped object before them. One example, dated

c. 600, depicts the donor, Theodote, approaching Christ with gifts, representing to the viewer the correct model of adoration that would enable them to recognize the significance of Christ’s sacrifice (

Peers 2004, pp. 22–23). These concepts have particular relevance here: the devotional context and sense of depth imparted by the iconic frame surrounding Christ, and the arrangement of Longinus and the female figure beneath it suggests that they represent viewers standing before an icon. This may well explain why the Scandinavian female figural type was selected for display; her horn may have been interpreted as containing an offering or gift presented to Christ. Regardless of whether this was the case, the figures’ associations with conversion and recognition in this context nonetheless imply that they were intended to inspire compunction in the viewer, which would, subsequently, prompt a mimetic response enabling the beholder to contemplate the carved image of Christ and witness his divinity. The pair visually suggest the appropriate attitude for viewing the crucified Christ, as the historical figure, crucified and triumphing over death, and the figure yet to materialize in Judgment at the eschaton. This is indicated by Longinus’ piercing of Christ’s side, which references the historical event of the Crucifixion and is further underscored by the stepped base selected to support the monument, while Christ’s emergence from the frame anticipates his Second Coming. Glenn Peers has further highlighted that ahistorical, ambiguous figures were often included in iconic scenes of the Crucifixion to “represent the assimilation of viewer and object of devotion into a permanently commemorated relationship” (

Peers 2004, p. 19). This indicates another potential function of the female figure: to assimilate the viewer at Gosforth with the image of the Crucifixion, and with the monumental cross, generally, by representing the appropriate devotional attitude to be adopted.

Furthermore, as Celia Chazelle has argued, gazing at the cross underscored the recognition of Christ’s sacrifice as the source of redemption and sacred wisdom (

Chazelle 2001, p. 116). Although there is no cross in the Gosforth image, using the frame to isolate Christ from the remainder of the program emphasizes the extended arms of the cruciform pose. Early to mid-ninth-century treatises demonstrate that Christ’s death was understood to have blessed the cross and its form, rendering its visual representations sacred and enabling them to evoke memories of Christ’s sacrifice and the victorious nature of his death, in order to increase the devotion of the faithful (

Chazelle 2001, pp. 114–16). This goes some way to explaining the absence of a cross in the Gosforth Crucifixion, its presentation on a monumental stone cross notwithstanding; the cruciform pose of the figure explicitly invokes the cross of the Crucifixion, rendering Christ’s body synonymous with that cross.

The Gosforth frame, used to denote an icon, prompts the viewer’s compunction, this emotional response enabling them to perceive the two figures below, associated with sight, conversion and recognition, as standing before an icon. Together, these features would convey to the viewer that they should respond mimetically by contemplating the image, gazing upon Christ-as-cross, and adopt an appropriate attitude of adoration, elicited by contemplation. This would, in turn, inspire prayer, potentially in supplication for their salvation, encouraging a secondary mimetic response. In an attitude of prayer, the viewer would adopt the

orans pose, which assimilated their body with that of Christ on the cross (

Peers 2004, p. 13). For a viewer of the Gosforth Crucifixion to adopt the pose would thus create a ‘living image’ of the framed carving of Christ before which they stood. Christ and his presence were understood to be implicit in all forms of the cross, which included the imitative pose of the position of prayer, and an interruption to this posture was considered the equivalent of losing bodily and intellectual contact with God (

Peers 2004, pp. 27–28). In this context, the Gosforth image of Christ in the cruciform pose would encourage the viewer to maintain their attitude of prayer, thus increasing their contact with the divine, made present by contemplation of the iconic image before the viewer, its framed image of Christ creating a threshold between the human and divine worlds and emphasizing Christ’s role as victor over death.

5. The Crucifixion in Context

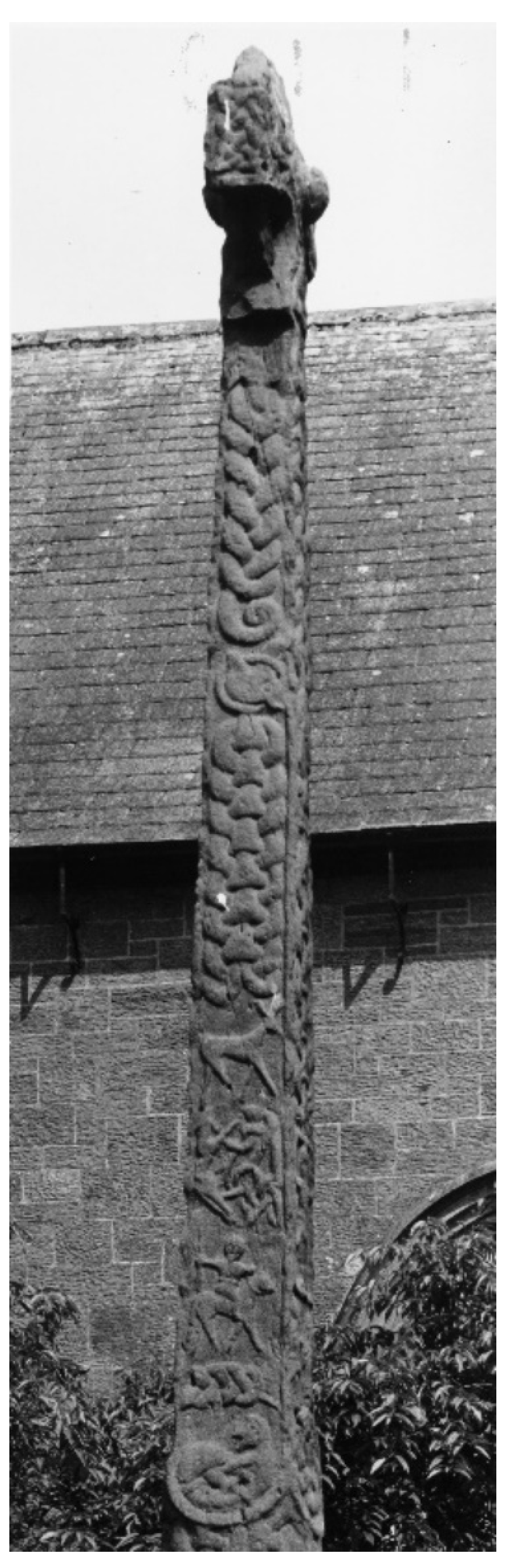

By viewing the frame enclosing Christ as a feature that both functions as a threshold bridging the human and divine worlds and signifies that the image should be viewed and understood as an icon—intended to make Christ present for the viewer, inspire the adoration of the cross and prayer—it becomes possible to discern potential Christian symbolic significances of the figural imagery carved on the remainder of the cross. As noted, these have generally been identified using twelfth- and thirteenth-century Icelandic texts to assign them various Norse symbolic significances. Face A (West) (

Figure 12) contains at its base a figural scheme presented in three registers, the lowermost comprising a supine figure with raised arms chained to a serpent, whose head hangs over the figure. Above, a kneeling female figure with the ponytail hair arrangement typical for this period holds out a bowl (

Bailey 1980, p. 79). The pair is ‘sheltered’ by a roof, enabling the scheme to be identified as depicting the god Loki, bound beneath the serpent and attended by his wife, Sigyn, who attempts to collect the snake’s acidic venom (

Calverley 1883, pp. 378–81;

Calverley 1899, pp. 142–47;

Collingwood 1923, p. 214;

Parker and Collingwood 1917, p. 102;

Bailey 1980, p. 128;

Kopár 2012, pp. 82–83). The inclusion of this scheme in the Gosforth program suggests that the patrons or those responsible for designing the cross anticipated that it would be viewed by those from a Scandinavian background, who possessed knowledge of Scandinavian traditional belief and its associated mythologies. Its placement opposite the Crucifixion depicted in the same position on C, however, may well indicate that the monument’s designers intended to juxtapose the two, perhaps extending the eschatological concerns invoked by the Crucifixion and the other carvings. Thus, within Christian frames of reference, Loki—receiving temporary relief from his suffering—may well represent those for whom the Final Judgment would bring an end to earthly torment: or render it permanent: a subject at the forefront of a viewer’s mind when contemplating the significances of the Crucifixion.

Above this scheme, an upside-down horseman carrying a spear was initially identified as Odin riding Sleipnir to consult Mimir (

Calverley 1883, pp. 383–84;

Calverley 1899, pp. 148–49;

Bailey and Cramp 1988, p. 102). Any potential association with Odin is unlikely, however, given the absence of any Odinic attributes (such as the single eye or two ravens) from the depiction. Furthermore, the horse has four legs, rather than the eight associated with all visual presentations of Sleipnir, as on the Gotlandic picture-stone Alskog Tjängvide I (Stockholm, Statens Historiska Museet, SHM 4171), rendering this identification far from convincing. Above the horseman, a human figure holding a spear and standing on a perpendicular plane has been interpreted as Heimdallr with the Gjallarhorn in his left hand (though this attribute is difficult to discern), rousing the gods for the final battle of Ragnarök (

Calverley 1883, p. 383;

Calverley 1899, p. 148;

Davidson 1964, p. 173;

Bailey 1980, p. 128;

Bailey and Cramp 1988, p. 102;

Kopár 2012, p. 92). Although unable to identify the horseman, Bailey suggested that its pairing with the remaining figures alludes to the enmity between Heimdallr and Loki, with Loki’s escape from his bindings representing the catalyst for Ragnarök (

Bailey 1980, pp. 128–29).

The arrangement of B (South) (

Figure 13) differs slightly from that of A, with a profile beast at the base, above which is a horseman that Bailey has tentatively proposed may represent the god Tyr. Unfortunately, this identification is based solely on the circumstantial evidence of “what appears to be a very short (admittedly left) arm”, and the horseman’s spatial relationship to the hound and bound beast above (

Bailey 2000, pp. 19–20). Above the horseman is a vertically-disposed hound, whose head faces upwards towards a horizontally-disposed hart. A short section of interlace lies on the same plane, below the hound’s legs. This interlace is not serpentine as has been claimed (

Parker and Collingwood 1917, p. 102), and its vertical arrangement is determined by the constraints of the cross-shaft. As recently as 2012, the scheme has been explained as the wolf Garm attacking the hart, Eikthyrnir, which symbolized the fountain of living waters (

Calverley 1883, pp. 386–88;

Kopár 2012, p. 93), despite Berg’s rejection of this identification because Eikthyrnir is neither a significant mythological figure, nor possesses any connections to Garm (

Berg 1958, pp. 36–37). Above the hart-and-hound motif, a run of ring chain terminates in a ring-encircled animal head, which Kopár identified as the wolf, Fenrir, devouring the sun. Yet, there are significant visual discrepancies between the ring chain zoomorph and the hound below, suggesting that this explanation is unlikely; rather it may simply have been understood as a beast with bound jaws, generally. Just below the cross-head on B is a further zoomorph.

As the hart-and-hound motif on B cannot be securely associated with any extant Norse mythological episodes (

Berg 1958, p. 37), it is at least possible that the scheme may have other (Christian) reference points. The motif occurs on tenth-century cross-shafts at Dacre (Cumbria) and Middleton (Yorkshire), where the monument type instills it with potential Christian significances regardless of its ultimate art-historical origins. As Bailey demonstrated using patristic texts, the hart and dogs of Psalm 21 were understood to allude to the moment of Christ’s Passion, enabling the motif to be viewed a symbol of the soul attacked by evil and/or symbolic of Christ’s Passion, with a visual referent in the early ninth-century Utrecht Psalter making this connection explicit (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS Bibl. Rhenotraiectinae I Nr. 32, fol. 24v;

Bailey 1977, pp. 68–69). In the light of these associations, it is plausible that the Gosforth hart-and-hound motif was intended to signify, within multivalent frames of reference, Christ’s Passion and the subsequent potential for redemption, thus providing a much more appropriate accompaniment to the Crucifixion on C than a pair of Norse mythological beasts.

Unlike A and B, Face C (East) (

Figure 14) contains two figural scenes separated by a run of ring chain, below which are two intertwined and confronting ribbon beasts with open jaws. As noted, the lower figural group depicts the Crucifixion, featuring Longinus and a Scandinavian-type female figure, although it was originally identified as Odin, Baldr or Heimdallr crucified, above the Midgard serpent. The upper group lies on a vertical plane above the ring chain and comprises a human figure holding a spear and confronting an open-mouthed beast, whose body is intertwined with that of another, whose head lies below the cross-head. This has long been interpreted as another Ragnarök episode described in twelfth-century texts: Viðarr’s revenge against the wolf that had slain Odin (

Calverley 1883, pp. 393–95;

1899, pp. 158–60;

Parker and Collingwood 1917, pp. 102–5;

Bailey 1980, p. 128;

Kopár 2012, pp. 75–77). Its pairing with the Crucifixion below has been understood to portray triumph over evil (

Bailey 1980, p. 128;

Kopár 2012, pp. 91–92), with the implication that the arrangement was intended to fuse Christian and Norse eschatological narratives (

Kopár 2012, pp. 93–94).

Building on this figure’s identification as Viðarr attacking Fenrir, Kopár suggested that the spear in the Crucifixion image and those carried by the horsemen elsewhere on the shaft reference the cult of Odin (

Kopár 2012, p. 110). Yet, the absence of other Odinic attributes (such as the valknut symbol, two ravens, a one-eyed figure or Sleipnir) suggests it is unlikely that any of these images were intended to recall Odin or his cult, and provides clear insight to the scholarly tendency to view the carvings as ‘illustrations’ of mythological episodes, contrary to the visual evidence. Furthermore, a general lack of resemblance between the two intertwined beasts in this scheme and the hound on B suggests that the intertwined beasts were unlikely to represent a wolf; rather, the scene may have been intended as a deliberately ambiguous representation of a hero defeating an evil being, given that this trope was common in Old English literature of the period, as demonstrated by several episodes in

Beowulf, preserved in the late tenth-century Vitellius manuscript (London, British Library, Cotton MS Vitellius A XV), for example, in which the titular character conquers numerous beasts (

Fulk et al. 2008, pp. 27–33 [ll. 739–852, 884–897], 51–54 [ll. 1497–1560]). On the other hand, alternative identifications for this beast and that at the top of B—as depictions of biblical Leviathans—can be pursued.

While parallels have been drawn between Leviathans and the dragon-like beasts carved on other Viking-age monuments, including the Gosforth ‘fishing stone’ (

Bailey 1980, pp. 124–32;

Bailey and Cramp 1988, pp. 108–9 [Gosforth 6]), such associations have not been proposed for the Gosforth Cross. Yet, in this context the ring around the jaws of the beast on B, can be explained as a literal interpretation of Job 40: 20–21, which questions whether the Leviathan’s tongue can be tied with a cord, a ring put through his nose or whether it is possible to bore through his jaw with a buckle. The Borre ring chain used for the beast’s body also finds explanation in Job 41: 6–8, which describes the Leviathan’s body as appearing like a series of molten shields with inseparable scales. This combination suggest that the sculptors attempted to ‘invent’ a Leviathan, which in this period had no fixed iconography, with features reflecting the scriptural accounts of that beast’s appearance. Its placement above the hart-and-hound motif may also be significant; if the hart-and-hound motif symbolized Christ’s Passion, its juxtaposition with the beast above would suggest that redemption could only be attained through Christ’s sacrifice, which enabled triumph over the beast, and by extension, all evil, as implied by its bound jaws.

This arrangement is echoed on C, where the beast confronted by the human figure above the Crucifixion may also have been intended to represent the Lord slaying the Leviathan with a sword as invoked in Isaiah 27: 1, where it is described as “bar serpent” and “crooked serpent” (In die illa visiabit Dominus in gladio suo duro, et grandi, et forti, super Leviathan, serpentem vectem, et super Leviathan, serpentem tortuosum, et occident cetum qui in mari est). The biblical beast appears to have been ‘invented’ here once again, combining a beast’s head similar to that on B, with a four-strand plait that comprises the ‘crooked’ body of the Leviathan. Although the figure holds a spear rather than sword, this does not preclude the possibility that contemporary audiences could interpret the scheme as a battle with the Leviathan, whose defeat would also signify triumph over evil; given their monumental Christian context, this hypothesis certainly offers a more appropriate analogue to the Crucifixion below than Viðarr’s revenge. The beast’s defeat, facilitated by Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, anticipates the eschaton, a concept implied in Revelation 20: 1–2, where the angel descends from heaven to bind Satan, described as dragon and serpent (draconem, serpentem antiquum), a factor that explains the ring ‘binding’ the beast’s jaws.

At the bottom of D (North) (

Figure 15), above a strip of interlace, are two horsemen carrying spears, the lower one shown upside-down, perhaps to suggest that they were engaged in combat (

Parker and Collingwood 1917, p. 108). This is plausible given the Scandinavian and Insular pictorial conventions of employing multiple planes within the same composition to portray depth. Above the upper horseman’s head, a triquetra surmounts a vertical rod, flanked by eight wing-like protrusions attached by rings, which terminates in an open-mouthed, fanged beast’s head. This creature has long been assumed to depict Freyr’s apocalyptic enemy, Surt, the fire beast, with the protrusions representing flames (

Calverley 1883, pp. 398–99;

Calverley 1899, p. 164;

Berg 1958, p. 38;

Kopár 2012, p. 92). This explanation, however, overlooks the resemblance of the protrusions and their attaching rings to wings, again demonstrating the overwhelming scholarly tendency to assign ‘pagan’ meanings to carvings on Scandinavian-period monuments; only Hilda Davidson rejected this interpretation, pointing to the absence of the attributes necessary to associate the creature with the mythological Surt (

Davidson 1964, p. 208), and suggesting that it may represent another beast, generally.

6. Summary

The Gosforth Cross has traditionally been viewed as a visual presentation of mythological episodes associated with Ragnarök. Yet, consideration of its immense scale, the selection of its monumental cross-form with stepped base and the placement of the Crucifixion scheme imply that it was intended as a major Christian monument in the landscape, rather than one in which Christian theology was “enriched and ‘illustrated’ by the pagan elements … to promote the understanding of the new religion” (

Kopár 2012, p. 155). Apart from perpetuating the perception of the carvings as ‘illustrations’, this view undermines the complex Christian associations that are invoked by the patrons’ deliberate selection of the ringed cross-head surmounting the shaft, which situates it in a wider network of Christian monuments throughout the Irish Sea region, and perhaps even more significantly, those associations invoked by the use of the stepped base, which references the most significant event in Christian theology, that of Christ’s Crucifixion at Golgotha.

Furthermore, re-assessment of its iconographic program demonstrates that only the carving of Loki and Sigyn at the bottom A can be securely associated with Norse mythology. Admittedly, many of the carvings, such as the riders and beasts, are ambiguous, possibly deliberately so, and this has been enhanced by the omission of panel divisions, in accordance with Scandinavian visual traditions. These include schemes formed of figures confronting beasts or serpents, whose multivalency would have appealed to viewers from both Christian and traditional backgrounds as representations of the defeat of evil. As several of these are situated near the cross-head, it is apparent that the defeat of evil is enacted by Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, a factor reiterated by the inclusion of the Crucifixion below, presented in an iconic format. Moreover, the multivalence of such deliberately ambiguous figures would enable them to be viewed and understood by secular audiences, who perhaps held traditional Scandinavian beliefs.

It is clear that the Crucifixion was intended as one of the most significant images in the Gosforth iconographic program, given its prominent and accessible placement. Christ’s Crucifixion may have been particularly recognizable to those who had yet to convert or were not fully Christianized, as it could be easily understood to portray the most crucial moment in Christianity. The image itself certainly emphasizes the moment of Christ’s sacrifice as that which enables his Second Coming and his ultimate triumph over evil, as alluded to by the sophisticated framing device and the figure confronting the serpent above. The frame enclosing Christ provides the scheme with an iconic nature, which encourages a state of compunction that will prompt the viewer to contemplate the significance of the event represented by the image. Such consideration of the image would emphasize Christ’s presentation within, and emergence from, the frame, details which further facilitate a visual collapse of time and space that simultaneously reference the historical event of the Crucifixion and anticipates the eschaton. Moreover, the frame separates Longinus and the female figure from Christ, an arrangement that accentuates their affiliations with Roman and Scandinavian traditional beliefs, respectively, and their status as converts, concepts which may have been relevant in the context of Scandinavian conversion and Christianization. The female figure of the Crucifixion may further be deliberately ambiguous given her representation according to Scandinavian visual conventions, although this does not necessarily mean she was perceived as ‘pagan’; the horn she holds could denote liturgical uses, and may elicit associations with Mary Magdalene.

Her separation from Christ, along with that of Longinus, may also have been intended to invoke concepts related to the veneration of the cross, a theme that featured prominently in the carved iconographic programs of tenth-century Anglo-Scandinavian crosses, including that from Nunburnholme. At Gosforth, however, the iconic arrangement of the crucified Christ facilitates the presentation of this concept. Here, the frame surrounding Christ signifies to the viewer that the image is to be viewed as an icon, intended to elicit compunction and contemplation, introspective experiences that would facilitate an understanding of Christ’s divinity and the salvation enabled by his sacrifice on the cross. Such concepts were further reflected in the contemporary liturgical celebrations of the Adoratio crucis, which emphasized sight and the inner vision of Christ. At Gosforth, sight and recognition were clearly crucial components linking Christ with the figures of Longinus and the woman depicted below. Their arrangement emphasizes the position of Christ, while the frame indicates the iconic arrangement and accentuates Christ’s cruciform posture, enabling Longinus and the woman to be perceived as standing before an such an image. Furthermore, while Longinus is recorded as recognizing Christ’s divinity at the Crucifixion in the scriptural accounts, the apocryphal narrative of the event suggested that his eyes were literally opened by the flow of Christ’s blood, a feature included in the Gosforth Crucifixion scheme. This suggests that Longinus and the accompanying female figure represented ‘witnesses’ to Christ’s Crucifixion, and his divinity, revealed at that event. In this context, the horn held before the female figure can be interpreted as a gift, presented to Christ in supplication.

Moreover, the arrangement of Longinus and the woman would encourage the viewer to reach a state of contemplation involving their fear of judgment, by providing visual models signifying the appropriate devotional attitude for viewing the crucified Christ. Inspired by compunction, contemplation of the details of this icon would enable the viewer to recognize Christ and contemplate his sacrifice on the cross. In turn, these factors would elucidate for the viewer Christ’s divine nature as revealed in his victory over death, a concept referenced visually by the figural type selected to depict Christ, and his emergence from the frame, anticipating the eschaton. The viewer’s recognition of Christ as both historical human and divine victor would thus enable them to contemplate their own place in the history of salvation, encouraging an outward response of prayer, in which they would adopt the orans pose, mimetically echoing that of Christ in the carving before which they stood. The adoption of this posture would assimilate the viewer with Christ, as Christ was understood to be present in all forms of the cross, including the imitative orans pose. The concern for procuring their own salvation may have further encouraged the viewer to reflect upon the image of Loki and Sigyn on the opposing face. Being the only image that can securely be associated with a Norse mythological episode, it may have represented for the early medieval viewer an admonitory image of the fate that awaited those who resisted acceptance of Christ and his Church as the way to salvation. Furthermore, the theological references to Christ’s Passion and victory over death, the veneration of the cross and triumph over evil encapsulated in the Crucifixion image appear to be repeated on B, albeit in an abbreviated and more ambiguous manner, in the motifs of the hart and hound and serpent with bound jaws. The monumental cross-form and its iconographic program thus appear to have been selected with the objective of communicating to its intended audience(s), through multivalent frames of reference, the significance of Christ’s Crucifixion as the catalyst for the Second Coming and the eternal salvation and triumph over evil to be achieved at this event, presented on the surface of the body of the cross(-shaft).