Abstract

Pilgrimages on the Ways of St. James are becoming increasingly popular, so the number of pilgrims registered in Santiago de Compostela has been rising continuously for several decades. The large number of pilgrims is accompanied by a variety of motives for a contemporary pilgrimage, whereby religion is only rarely mentioned explicitly. While pilgrimage was originally a purely religious practice, the connection between pilgrimage and religion is less clear nowadays. Therefore, this paper examines whether and in which way religion shows itself in the context of contemporary pilgrimages on the Ways of St. James. For this purpose, 30 in-depth biographical interviews with pilgrims are analyzed from a sociological perspective on religion by using a qualitative content analysis. This analysis reveals that religion is manifested in many ways in the context of contemporary pilgrimages, whereby seven forms of pilgrim religiosity can be distinguished. They have in common that pilgrims shape their pilgrim religiosity individually and self-determined, but in doing so they rely on traditional and institutional forms of religion. Today’s pilgrim religiosity can therefore be understood as an extra-ordinary form of lived religion, whose popularity may be explained by a specific interrelation of individual shaping and institutional assurance of evidence.

1. Introduction

The relation between pilgrimage and religion is often difficult to grasp, especially with regard to contemporary pilgrimages. Historically, pilgrimage on the different Ways of St. James has been documented since the 9th century (Herbers 2016). In those early and initial pilgrimages, we are undoubtedly faced with a religious practice. That is to say, because the destination of the Way of St. James is the Galician town of Santiago de Compostela, where the tomb of Apostle James the Elder is presumed to be located (Herbers 2007). The Gospel of Luke (Lk 5,10) as well as the Gospel of Matthew (Mt 4,21; Mt 17,1–13; Mt 26,37) report about his life. Both gospel writers portray not only James’ calling as a disciple of Jesus Christ, but also his participation in various stages of Jesus’ ministry. Furthermore, the Acts of the Apostles deals with James’ execution by King Herod Agrippa I in 43 AD (Acts 12:1ff.). According to the 12th century Liber Sancti Jakobi (Herbers 1984), James had endeavored to mission the Iberian Peninsula, but failed and returned to Jerusalem, where he was martyred. His body was then taken by two of his disciples to a boat that was guided by an invisible hand to the coast of Galicia. Here they searched for a dignified resting place for James and finally found it in a remote forest, where they built a crypt. Over the centuries, this burial place was initially forgotten until the beginning of the 9th century, when the hermit Pelagius spotted stellar constellations that seemed to point to a specific location (Drouve 2007, p. 61). Bishop Theodemir and King Alfonso II then had a church built over the supposed tomb, which was replaced by the present cathedral in the 11th century. Whether or not the bones of St. James the Apostle are actually in the crypt is disputed among historians. Nevertheless, this religious tale initiated the first pilgrimages to Santiago des Compostela, so that the Ways of St. James became well-travelled in the Middle Ages. In addition to religiously motivated pilgrimages for the purpose of petition and thanksgiving, penitential and punitive pilgrimages imposed by the church were also widespread that time (Ashley and Deegan 2009).

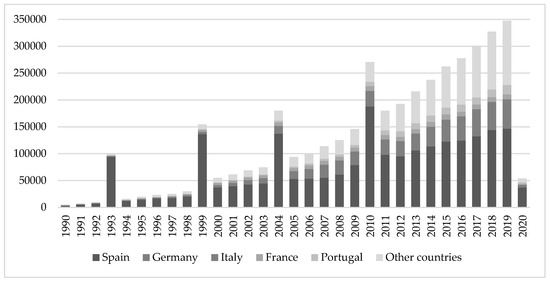

A similar strong link between pilgrimage and religion can be found in some major religions until today. Consider, for example, the Islamic Hajj to Mecca, which, as one of the five pillars of Islam, still has a high theological significance and the character of a religious obligation (Hammoudi 2007). In regard to Christian pilgrimage, by contrast, the relation between pilgrimage and religion is less obvious today (Chemin 2012). Though the Ways of St. James are still managed by a religious institution: the Catholic Church. It registers pilgrims in Santiago de Compostela and issues pilgrimage certificates to those who arrive at the destination. In addition, the Catholic Church periodically proclaims so-called Holy Years, during which the number of pilgrims increases on average to two and a half times the usual level. Finally, the Catholic Church offers a wide range of services along the Ways of St. James, such as pilgrim hostels and blessings, as well as pilgrim services and confessions in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. At the same time, the number of registered pilgrims has increased impressively in recent decades—not least due to successful branding campaigns, European political support, and massive investments in the infrastructure of the Ways of St. James routes (Frey 1997; Lois González 2013; Pack 2018). In 2019, more than 350,000 pilgrims were registered in Santiago de Compostela, for the most part from Spain, Germany, Italy, France, and Portugal (Figure 1). After a COVID-19-related collapse in the number of pilgrims in 2020, the Galician regional government expects growth rates of around eight percent per annum again in the coming years (CETUR 2009; Lopez et al. 2017).

Figure 1.

Pilgrims registered in Santiago de Compostela by nationality. Data: Archdiocese Santiago de Compostela. https://oficinadelperegrino.com/estadisticas/ (accessed on 3 April 2021).

Popular travel reports and pilgrimage novels suggest that contemporary pilgrimage on the Ways of St. James is not always a religious practice (Belmonte and Kazmiercak 2017)—consider, for example, Kerkeling’s (2009) book “I’m off then” or Estevez’s (2010) movie “The Way”. Also social science studies show that the multiplicity of pilgrims is accompanied by a wide diversity of pilgrimage motives (Amaro et al. 2018; Farias et al. 2019; Lois González and Santos Solla 2015; Oviedo et al. 2012; Reader 2007; Sime 2009). Motives related to the own self are mentioned with particular frequency (Gamper 2016; Gamper and Reuter 2012). In a multilingual survey of 1,142 pilgrims, more than half of the respondents said they wanted to “find themselves” during the pilgrimage (51.8%), followed by “escape from everyday life” (40.2%), “enjoy silence” (39.2%), “feel spiritual atmosphere” (34.6%), “enjoy nature” (34.4%), and “view beautiful landscapes” (32.9%). Thus, the most frequently mentioned motives were those that could be described as spiritual in a broad sense. Contemporary pilgrims are looking for silence, meaning in life and extra-ordinary experiences (Gamper and Reuter 2012, p. 220). With greater distance follow genuine religious motives for a pilgrimage such as “religious reasons” (23.4%), “get to know other religions” (22.4%), “repent toward God” (16.6%) and “visit Christian sites” (12.1%). Sporting ambitions, the search for adventure or touristic motives are mentioned even less frequently. Furthermore, it is remarkable that hardly anyone goes on pilgrimage “to reach the pilgrimage destination” (6.6%) (Table 1). On the basis of this frequency distribution, Gamper and Reuter (2012, p. 129) conclude that for today’s pilgrims, the goal of their pilgrimage is not the tomb of the Apostle James, but the journey to themselves.

Table 1.

Motives to undertake a pilgrimage on the Way of St. James ordered by frequency.

Gamper and Reuter cluster this broad spectrum of motives for a pilgrimage into five types of pilgrims by using a Principal Components Analysis (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin: 0.813, Bartlett test of significance: 0.000): culture- and landscape-interested touristic pilgrims (“Tourigrinos”), who often undertake pilgrimages together with relatives and friends, goal-oriented sports pilgrims (“Sportpilger”), for whom the physical challenge of a pilgrimage is paramount, and mostly younger fun pilgrims (“Spaßpilger”), who are looking for adventure and low-cost vacation opportunities. These three types of pilgrims play a subordinate role for this study and will not be considered in further detail below. In contrast, two other types of pilgrims distinguished by Gamper and Reuter are of high interest for the relation between pilgrimage and religion: traditional religious pilgrims (“traditionell religiöse Pilger”) and contemporary spiritual pilgrims (“Postpilger”). The relatively small group of traditional religious pilgrims is characterized by a firm, mostly denominationally bound faith. They see their pilgrimages as a confession of faith with the purpose of petition and thanksgiving. They often mention religious motives as an explicit reason for their pilgrimages. Contemporary spiritual pilgrims, on the other hand, represent by far the largest group of respondents. Their religiosity is characterized by a search for meaning and self-empowerment as well as by a relative independence from denominations. Accordingly, contemporary spiritual pilgrims most frequently mention self-related pilgrimage motives. Most of them started their pilgrimage, usually planned for several weeks or even months, without accompaniment, in order to find enough time for themselves. Gamper and Reuter therefore understand contemporary spiritual pilgrims not only as a prototype of contemporary pilgrims, but also as a prototype of a late modern need for individually shaped spirituality (Gamper 2016, p. 137; Gamper and Reuter 2012, p. 224). The two types of traditional religious and contemporary spiritual pilgrims will be explored in more detail below with regard to the significance and shaping of religion during their pilgrimages.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to elaborate whether and how religion is evident in the context of contemporary pilgrimages on the Ways of St. James, a secondary analysis of an interview study by Kurrat (2015) was carried out. In 2010, he conducted 30 in-depth biographical interviews—so-called narrative interviews (Schütze 1983)—with pilgrims, showing that contemporary pilgrims undertake their pilgrimages in typical biographical situations in order to reflect on their lives, cope with crises, take time off, shape biographical transitions, and construct new identities (Heiser and Kurrat 2015). Kurrat (2019) distinguishes five types of pilgrims, which emerged from his data: Balance pilgrims reflect and balance their lives. They are certain of their oncoming death on account of their advanced age or an illness. These pilgrims seek silence and moments of solitude for intensive reflections to remember the stations of their lives and to carry out balancing classifications. Crisis pilgrims reflect on a crisis and search for processing possibilities. An unplanned experience has shaken their lives massively. This occurrence is perceived as a shock and the pilgrimage shall be a way to overcome this feeling. Time-out pilgrims experience high demands in their profession at home and invest a lot of time in their occupations. The balance between private life and professional life is not given anymore and the occupational everyday life is considered as excessively burdening. These pilgrims undertake their pilgrimage to escape from their everyday life temporarily and to let ideas arise for priority changes. Transitional pilgrims find themselves in a rite of passage, e.g., after graduating and before becoming an employee or after their professional life and before retiring. Within these transition phases, the pilgrim’s past is reflected and future options are experimented. Finally, new start pilgrims have given up their profession and/or left their partners after a phase of massive irritation and want to begin a completely new life. During their pilgrimage, they try to find interpretation patterns for their ‘failed career’ and seek options for their future life. Their pilgrimage fulfills the function of an initiation.

For this paper, the original German-language transcripts of these interviews were translated into English and reanalyzed using a structuring qualitative content analysis (Mayring 2015). The main categories were formed deductively and theory-based according to a multidimensional understanding of religion, which considers its cognitive, affective, and practical dimensions (Glock 1962; Molteni and Biolcati 2018). The subcategories were formed inductively and material-based. In this way, a total of 190 analytical units could be paraphrased and generalized to a defined level of abstraction. After the reduction of redundancies, 103 generalized paraphrases could be categorized. The sample includes 30 pilgrims from Germany and Switzerland who walked at least 400 km—and who started their pilgrimage unaccompanied. For this reason, only individual pilgrim religiosity can be examined in the following. However, one can assume that also religiously motivated social concerns can be found in the context of contemporary pilgrimages, especially among (religious) pilgrim groups. Among others, the survey data discussed in Section 1 provides indications of this.

3. Results

Altogether, seven forms of religion could be identified which are significant in the context of contemporary pilgrimages on the Ways of St. James: the feeling of having been called to the Way of St. James by a higher power, the intention of thanksgiving towards God through a pilgrimage, the interpretation of the physical strains as penance for sinful behavior in the past, the visit of churches as places of meditation, the search for religion, and the interpretation of experiences and meetings as miracles and sending. The first three forms are more common among traditional religious pilgrims, the other three among contemporary spiritual pilgrims. In addition, there is a seventh form of religion that is found with equal frequency among both types of pilgrims: the self-determined execution of core religious practices such as praying and attending church services (Table 2).

Table 2.

Forms of religion in the context of contemporary pilgrimages.

All seven forms of religion during contemporary pilgrimages on the Ways of St. James are explored below via exemplifying interview quotations.

3.1. Called on Way of St. James by a Higher Power

In many cases, traditional religious pilgrims feel called to the Way of St. James by a higher power. This applies, for example, to a 22-year-old Catholic who will finish his job training soon and who wants to ritually shape his transition into professional life by the pilgrimage1:

“I had the feeling: The way is calling me.”(P02, par. 11)

This feeling is also shared by a 51-year-old Catholic nurse who recently divorced:

“I’m actually here because I think somehow I was sent here from above.”(P28, par. 125)

As well as a 78-year-old Methodist who, as a former soldier, wants to reflect on his life and deal with his experiences during combat missions:

“I went into the church and stayed and came out wanting to do the Camino.”(P23, par. 14)

While the feeling of being called to the Way of St. James for the former soldier was already present before starting the pilgrimage, for a 70-year-old Catholic pensioner who also wants to look back on his life, it has developed in the course of the pilgrimage:

“By now I have to say: It is [...] not a wish, but it has been a calling [...]. In the beginning there was the wish to go the way, but more and more it became a calling.”(P26, par. 5)

Also for a 65-year-old former therapist, her pilgrimage is related to her retirement. She attributes her calling to the Way of St. James to angels:

“In 2006 I retired, on July 1 [...], and in December I received the message from my angels that I was prepared to go on the Way of Saint James. [...] I got the message in the evening and in the morning, I checked the internet. I said to my husband: ‘My angels told me to walk the Way of St. James, and now I have to see where it is.”(P09, par. 11)

3.2. Pilgrimage as Thanksgiving

In many cases, traditional religious pilgrims mention motives that were already typical for historical pilgrimages in the Middle Ages and early modern times, especially that of thanksgiving towards God. The pensioner, who wants to reflect on his life, describes it with the following words:

“I see the whole thing as a thankyou upwards. [...] I was successful in my life. And for that I would like to say thank you somehow.”(P26, par. 5)

A 35-year-old Russian Orthodox cashier would like to thank God especially for the well-being of her family. She has given up her life in Germany and wants to return to her Macedonian homeland after the pilgrimage.

“In a way, this is also a thankyou I want to say to God. My brothers and sisters are healthy, the baby is healthy, my family. This is so the main reason for me to be grateful.”(P12, par. 191)

3.3. Physical Pain as Penance for Sins

The desire for penance and forgiveness represents the third classical form of religion, which is still evident among traditional religious pilgrims today. Forgiveness plays an important role, especially for the former soldier:

“I walked for forgiveness. I am asking for forgiveness. And each of my Caminos has been asking for forgiveness. And then when you get older you may think about things you’ve done and you want to confess and you do.”(P23, par. 14)

The pensioner who wants to reflect on his life does so in a very systematic way: Every day he consciously thinks back to a distinct phase of his life. If he strongly feels the physical strain of long-distance walking on that particular day, he interprets this as a sign that he has made mistakes in the corresponding phase of his life—for which he now has to do penance:

“There are, of course, things you did wrong in your life, things you regret. That is what you think about here. And I ask for forgiveness. I think back a lot about the stations in my life and about my experiences. [...] And for the negative ones, I gladly accept the one or other blister or any joint pain. May it be as a penance or whatever.”(P26, par. 47)

3.4. Religious Core Practices

Traditional religious core practices are regularly performed by both traditional religious pilgrims and contemporary spiritual pilgrims on the Ways of St. James. However, these practices are not experienced as obligatory acts imposed by denominations, but rather as choices provided by religious traditions that can be taken whenever the individual pilgrim feels it is appropriate and helpful. This applies, for example, to praying. A 66-year-old Protestant retiree who started his pilgrimage after separating from his wife prefers to pray in community:

“These days, it’s like we embrace each other in the morning at the start, all three of us, and then we say a prayer and sing a Taizé song.”(P27, par. 35)

A 70-year-old Catholic retiree who started her pilgrimage after the unexpected death of her son prays regularly on the Way of St. James with the help of her rosary:

“I even took a rosary with me, which is blessed, and I sometimes say when I’m walking: Please help me move forward well.”(P08, par. 42)

Attending church services also counts among the core religious practices that contemporary pilgrims self-determinedly rely on. The many churches along the Ways of St. James regularly offer church services, which often include a blessing of pilgrims. For a 19-year-old Protestant student who has just graduated from high school and who is looking for inspiration for his future life, attending church services is a natural part of a pilgrimage:

“Whenever I walk through a town and have a look at the church, I also [...] take part in a church service. Because it’s just part of it for me. But at home I don’t go to church. Simply because I can do other things there that move me forward more in my life.”(P10, par. 59)

Also in the monasteries along the Ways of St. James, which often provide accommodation for pilgrims, regular services are celebrated, which are described as particularly impressive due to their special atmosphere:

“We were accommodated in a monastery hostel and in the evening a mass was celebrated in the monastery church followed by the blessing of the pilgrims. That was so moving. That was really so... The monks [...] asked the pilgrims to come to the altar and prayed together with them. [...] The spirit there, that was such a deep experience, [...] such a deep impression. From then on, I just walked and walked.”(P26, par. 05)

For some of the contemporary spiritual pilgrims, attending church services is a completely new experience. For example, for a 46-year-old non-denominational media executive who is taking time out from her stressful professional life on the Way of St. James:

“I’m not pious and faithful and walk into every church, although I take hundreds of pictures of them here. [Pilgrimage] doesn’t have the religious background for me so that I would say: I’m on the way spiritually and I’m searching for God. No. I also visit church services here and have had the pilgrim’s blessing given there. I found that very impressive. But people at home really shake their heads and [...] absolutely do not understand why. [...] I think the churches here are beautiful because you are really a part of it, whether you live in this place or not. From that point of view, I think it’s quite great. I’ve had communion here twice [...]. And the priest comes and even shakes hands with everyone, even though I don’t belong to the congregation. I don’t know something like that from home, but I find it very impressive. [...] It‘s wonderful.”(P24, par. 56)

3.5. Visiting Churches as Places of Meditation

However, contemporary spiritual pilgrims in particular use churches not only to attend services, but also as places of meditation where they can retreat to find silence and contemplation. One example is a 30-year-old non-denominational technician who came to the Way of St. James to reorient himself professionally. After some years of dissatisfaction with his occupation, he recently quit his job and wants to start a new professional life after his pilgrimage:

“I often go to churches on the way, sit down for five or ten minutes, enjoy the silence, contemplate, have a prayer as well. I include people who have become close to me on the way or friends and family from home in prayer. I believe for myself, have my own way. [...] At home I never went to church, I never did that at home, but I think when I’m back home I’ll do that from time to time, go to church. Because maybe it’s also good for you to have five minutes of peace.”(P15, par. 137)

Similarly, churches along the Ways of St. James are used by a 62-year-old senior executive, who is confronted with high professional demands in his everyday life:

“We always looked when we were resting somewhere where there is a church in such a small village. And then we usually went into this church, put our luggage down and each of us said a prayer in silence or simply tried to have a dialogue with God or at least with the feelings that one has in a church.”(P04, par. 23)

Also for a 46-year-old Catholic alternative practitioner who wants to cope with the death of her father, churches are important places to find peace and new strength:

“This entering into the churches. I think churches have always been built at places of power, and you feel that. You enter a church and suddenly there is silence, peace. You are also surrounded by such a... Okay, come down again. All this atmosphere, colorful windows, the sun shining in. It’s always a very special mood. I think that’s totally important.”(P07, par. 62)

3.6. Search for Religion

The pilgrimages of contemporary spiritual pilgrims are often related to biographical processes: They go on pilgrimage in specific life situations in order to cope with crises, to take time out and/or to undergo biographical changes. Their religiosity is more individually shaped and less dependent on denominations than that of traditional religious pilgrims. The search for religion can be reconstructed in all interviews conducted with contemporary spiritual pilgrims; however, it is expressed explicitly and proactively only in a few cases. For example, a 25-year-old Catholic student who has lost her also due to an experience of abuse in her childhood:

“It is also a motivation to reconnect a bit with what I’ve lost. [...] Now I have chosen the Way of St. James, simply, if I’m honest, because there is something religious there. And I think that I actually long for it a bit, because I can’t feel it at home.”(P01, par. 5)

Also a 23-year-old student who is about to graduate lost his connection to religion in recent years. Looking back, he is quite dissatisfied with his life as a student. After a few years of partying and leisure, he now wants to steer his life in a more reasonable direction. However, the desire for religion is less apparent in his case:

“For religious reasons I was thinking about walking the Way. I was looking for adventure. But religion was not a negative thing. It was something like: Oh, that could be good also. […] I think it’s what many people on the way are searching for. So, I think it’s why I’m doing the Camino.”(P19, par. 62)

For the alternative practitioner, religion is especially important during the transition into a new phase of life. In the context of biographical transformations, religious practices can function as rites of passage:

“I also do it [the pilgrimage, P.H.] for religious reasons. Because a period of life ends, a new one is coming. Just as an important final point, as the conclusion of a part and a new beginning, so to speak.”(P07, par. 52)

3.7. Interpretation of Experiences and Meetings as Miracles and God-Sent Experiences

Meetings with other pilgrims are often experienced as particularly intense. Numerous interviews report how quickly deep conversations about highly personal topics arise between pilgrims and how soon relationships develop that are experienced as extremely strong and intimate. This intensity of social relationships during a pilgrimage can be explained by the fact that social differences are minimized by the greatly reduced lifestyle during a pilgrimage, that the infrastructure of the Ways of St. James offers sufficient space and time for intensive exchange, and by the fact that many pilgrims go on pilgrimage because of biographical situations that can only be coped with in communicative exchange (Heiser 2012). This can be seen, for example, in the following report by the recently divorced nurse:

“The first one started to cry and talked about his problems, then the next one talked about his problems and then it went around [...]. One of them has a sick father, the other one is divorced and can’t cope with it [...]. So, everyone actually has his own reason for being here. The thesis we came up with, which no one could answer: Who sent us here at this time? Did someone send us here? And we all assumed that we were guided and sent by somebody, but we don’t know by whom.”(P28, par. 69)

In many cases, the interviewees describe the meetings during their pilgrimage as God-sent, for example, an 18-year-old Catholic high school student who wants to find out which profession he should choose:

“I don’t believe in coincidence anymore since I’ve been walking here. For example, after school I want to.... To become a teacher, you have to have an internship, and I want to do that in the U.S. at an elementary school. Who do I meet at six in the morning at the cathedral in Leon? Well, the principal of the second-best elementary school in the U.S., who invites me to write her because she would be very happy to have me at her school for two months. That’s not a coincidence, I can’t imagine. [...] Something brought up this meeting intentionally.”(P29, par. 304)

Especially the meetings with pilgrims who help others in difficult situations are described as sending, for example in the following interview passage of the cashier who wants to go back to Macedonia:

“Here on the way, when you are all alone and can’t continue walking because you have no more water, you say: God help me. He may not come in person, but someone comes. Another pilgrim or someone who helps or just shares a few words. [...] That’s not a coincidence, I’m convinced.”(P12, par. 239)

A similar story is told by a 52-year-old Protestant secretary who began her pilgrimage after separating from her husband:

“That stage of the way was very exhausting, but I managed to do it. Also with the help of an angel named Finn from Ireland, who appeared on my way as if he had just fallen from heaven. [...] I stopped once more with my backpack because it was too heavy for me, and I just ate my last banana, drank a sip of water. Then he came out of nowhere. [...] I got up, went along with him as a matter of course. [...] I saw this person as an angel, and he has been very good to me. He gave me a certain peace.”(P13, par. 11)

Such experiences are repeatedly described as miracles in the interviews, for example by the alternative practitioner already quoted and by the recently divorced retiree:

“We were there in a godforsaken area and there was just nothing [...]. I remember it was cold and such a grey, foggy day and I was incredibly hungry. And suddenly a woman is standing there and just offers you something home baked. And you think: There’s no such thing. [...] In the city you don’t think about it, because there’s Pizza Hut and McDonalds and [...] a bakery on every corner [...]. But here you might get the situation that you are really hungry. [...] And just at this moment there is an elderly woman who had just made fresh pancakes. It’s a miracle. You perceive that at that moment as a gift from God.”(P07, par. 106)

“At some point during the afternoon, both my calves said: Now we turn the power to zero, we don’t want any more. And that was the crucial point for me: What to do? Continue or give up? I then decided to continue but said to the others: Let me rest for a moment, I need to gather my strength [...]. So, I rested for a few minutes and, under the critical eyes of the others [...], took tiny little steps. And the miracle happened: It worked. And then I said to myself: The fact that you are lying in the dark valley, that is now transmitted to my private situation [...]. You want to get back to the top of the mountain, where the sun is shining. And you have to take steps. Yes, and that’s what I did. And that’s just so beautiful to transfer to my personal situation, where I also took steps to get out of the dark valley.”(P27, par. 3)

Finally, in describing contemporary pilgrim religiosity, two terms with religious connotations should not be ignored, which are used repeatedly in the interviews. The first is the term ‘sign’, which is used here by a 77-year-old Catholic pensioner who describes himself as a Templar:

“God sometimes shows me the way and also sometimes shows me that it’s better to stop from time to time on the Way of St. James and say: Have a rest. When it rains or when it’s really bad weather, I know: Okay, it’s a sign. Your body needs rest.”(P16, par. 75)

On the other hand, there are frequent reports of ‘lessons’ that can be learned during the pilgrimage. This is what a 23-year-old Catholic waitress does, for example, who came on the Way of St. James after a serious accident:

“You always get little lessons. Every person, in my opinion, has some kind of to-do list given to them by God or given to them by the universe. Like, for example, some people can never say no. And you are put in a similar situation until you act differently than you did before.”(P30, par. 171)

4. Discussion

The above presented results of the pilgrimage research on the Ways of St. James show: Compared to other pilgrimage motives, religion is only rarely mentioned explicitly as a motivation for a contemporary pilgrimage. However, religion is present in many ways also in the context of contemporary pilgrimages: Pilgrims feel called to the Ways of St. James by a higher power, they use their pilgrimage for thanksgiving and penance towards God, they pray, attend church services, meditate in churches and interpret their experiences as signs and wonders as well as their meetings with other pilgrims as God-sent. Therefore, not only the historical pilgrimage in the Middle Ages and early modern times can be described as a religious practice, but also the contemporary pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. If there is a wide continuity between traditional religious pilgrims today and pilgrims who travelled the Ways of St. James decades or even centuries ago could only show a systematic comparison with historical sources. At least, there is one significant difference between historical and contemporary pilgrimages: While pilgrimage in early times had the character of a religious duty imposed on the individual by the Catholic Church as religious institution—e.g., for the purpose of penance and punishment—pilgrimage religiosity today is shaped by the pilgrims themselves. They do not carry out religious practices because religious institutions make it obligatory, but because they experience religion according to their own motivation and carry it out in a way that they themselves consider appropriate for a given situation. Pilgrimage can therefore be described as a form of lived religion. This approach argues for not looking at religion from a narrowed perspective on its institutionalized forms: “[I]nstead of starting from official organizations and formal membership, I want to begin with everyday practice; instead of taking the experts and official theology as definitive, I will join the lived religion scholars in arguing that we need a broader lens that includes but goes beyond those things” (Ammerman 2014, p. 189f.). From the perspective of lived religion, religion does not simply disappear in late modern societies—as at least certain readings of the secularization paradigm suggest. Rather, it is persistent in form of diverse religious practices: “Looking at religion as when one moves beyond adherence gave less support to declensionist narratives: when one moves beyond adherence to institutions as the indicator, rather than seeing religion as disappearing under modernity, religion—as practices—appears to be proliferating” (Neitz 2011, p. 47). Lived religion is understood as actuality in which a situational execution of certain practices reproduces religion on and on (Hillebrandt 2012, pp. 25, 51). Thus, lived religion is not an approach that is limited to institutions or organizations, neither it is a purely individualization-based approach. Rather, the focus of lived religion is namely the interrelation of lived religious practices with religious institutions and traditions (Neitz 2011, p. 54). This interrelation between lived and institutionalized religion is highly diverse: the former is framed by the latter (Hall 1997, p. viii) and insofar supported as religious institutions provide objects, meanings and acts that religious practices rely on in their execution (Ammerman 2014, p. 157). In the case of contemporary pilgrimages, for example, one can think of using ecclesiastical hostels, attending church services, performing traditional pilgrimage rituals, and referring back to religious narratives.

The protagonists of the lived religion approach cited here locate religion in everyday life. On the one hand, this is understandable, since everyday life is the space “in which the religious receives its own weight precisely because it is interwoven with the practical dimensions of life. Religiosity is not just an everyday phenomenon, but embedded in the practice of everyday life” (Schützeichel 2018, p. 94, translation: P.H.). On the other hand, such a focus on the relevance of religion to everyday life hides an important problem: it obstructs the view of extra-ordinary forms of religion. From the pilgrimage research, however, we know that it is particularly the extra-ordinary character of a pilgrimage that is a necessary condition for pilgrims to be able to reflect on their lives, to process life crises, to shape biographical changes, and to construct new identities (Heiser and Kurrat 2015, p. 149ff.; Kurrat 2015, p. 106ff.). Therefore, it seems appropriate to extend the lived religion approach to extra-ordinary religious practices.

Finally, if religion also has a major role to play in contemporary pilgrimages, it is imperative to discuss why the religious practice of pilgrimage remains so successful today, while other markers of the religious field (such as denomination membership or the performance of core religious practices such as attending church services and praying) have been in sharp decline in many parts of the world for decades. One possible answer to this question lies in the specific interrelation between individual shaping and the institutional context we find on the Ways of St. James. Namely, the self-determined shaping of pilgrimage religiosity is a necessary condition for the popularity of contemporary pilgrimage, but by no means a sufficient one. Rather, it must coincide with institutions and traditions that are able to ensure the evidence of religious practices. This is the case because self-determined religious practices are confronted with their own contingency in an increased manner. How is the individual pilgrim to know that the pilgrim religiosity he or she has shaped is ‘right’ and effective? What is needed here is an institutional context that guarantees the evidence of self-determined pilgrim religiosity. This is precisely why the majority of those affected in life crises and transitions do not go on pilgrimage just anywhere, but rather along the traditional Ways of St. James administered by the Catholic Church. The diverse individual shaping options and interpretation patterns thus meet on the same traditional path. Here, the church and the pilgrimage tradition provide contexts of meaning and forms of action, which pilgrims rely on in their individual execution of religious practices.

5. Conclusions

In the context of contemporary pilgrimages on the Ways of St. James one can find many forms of lived religion. Even pilgrims without any strong ties to religious institutions or traditions depend on these religious structures to get their agency as pilgrims. They still, and even increasingly, turn to traditional pilgrim routes rather than just going for random hikes in specific biographical situations. In addition, they do usually not invent new religious practices and interpretations along these routes but rather rely on old traditions for their individualistic journeys. Thus, there is a lot of individualism to be observed on the Ways of St. James—but just within traditional plots. To summarize: Individualistic spiritual agents get their pilgrimage agency from traditional religious structures without the intention to invent new practices. Thus, pilgrimage research impressively demonstrates that religious institutions and the individual shaping of religious practices do not represent dualistic opposites. On the contrary, both are constitutively depending on each other; it is only their interrelation that allows an explanation of the popularity of certain religious practices under the conditions of late modernity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable due to secondary analysis that solely used anonymized data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

3rd party data.

Acknowledgments

I thank Christian Kurrat for sharing his interview transcripts, for our numerous discussions about pilgrimage, and for his review of this paper’s manuscript. For their as critical as helpful comments I thank Frank Hillebrandt and Mariano Barbato as well as the journal’s reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Amaro, Suzanne, Angela Antunes, and Carla Henriques. 2018. A closer look at Santiago de Compostela’s pilgrims through the lens of motivations. Tourism Management 64: 271–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy T. 2014. Finding religion in everyday life. Sociology of Religion 75: 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, Kathleen, and Marilyn Deegan. 2009. Being a Pilgrim: Art and Ritual on the Medieval Routes to Santiago. Farnham: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte, Miguel Àngel, and Marcin Kazmiercak. 2017. Faith and Narrative: The Secularization of the Way of St. James through Literature. S. 159–83. In The Way of St. James: Renewing Insights. Edited by von Alarcón Enrique and Piotr Roszak. Pamplona: Eunsa. [Google Scholar]

- CETUR. 2009. Estudo da Caracterización da Demanda Turistica de Santiago de Compostela. Santiago de Compostela: CETUR. [Google Scholar]

- Chemin, Eduardo. 2012. Producers of meaning and the ethics of movement: Religion, consumerism and gender on the road to Compostela. In Gender, Nation and Religion in European Pilgrimage. Edited by von Jansen Willy and Catrien Notermans. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Drouve, Andreas. 2007. Die Wunder des Heiligen Jakobus. Legenden vom Jakobsweg. Freiburg: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Estevez, Emilio. 2010. The Way. New York: Producers Distribution Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Farias, Miguel, Thomas J. Coleman, James E. Bartlett, Lluis Oviedo, Pedro Soares, Tiago Santos, and Marís des Carmes Bas. 2019. Atheists on the Santiago Way: Examing Motivations to Go On Pilgrimage. Sociology of Religion 80: 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, Nancy L. 1997. Landscapes of Discovery. The Camino de Santiago and Its Reanimation, Meanings, an Reincorporation. Ann Arbor: UMI. [Google Scholar]

- Gamper, Markus. 2016. Postpilger auf historischen Kulturwegen. Eine soziologische Studie zur Pilgerkultur auf dem Jakobsweg. S. 121–39. In Kulturstraßen als Konzept. 20 Jahre Straße der Romanik. Edited by von Ranft Andreas, Wolfgang Schenkluhn and Nicole Thies. Regensburg: Schnell + Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Gamper, Markus, and Julia Reuter. 2012. Pilgern als spirituelle Selbstfindung oder religiöse Pflicht? Empirische Befunde zur Pilgerpraxis auf dem Jakobsweg. In Doing Modernity—Doing Religion. Edited by von Daniel Anna, Franka Schäfer, Frank Hillebrandt and Hanns Wienold. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 205–32. [Google Scholar]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1962. On the study of religious commitment. Religious Education. The Official Journal of the Religious Education Association 57: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, David D. 1997. Lived Religion in America: Toward a History of Practice. Princeton: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hammoudi, Abdellah. 2007. Saison in Mekka. Geschichte einer Pilgerfahrt. München: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Heiser, Patrick. 2012. Lebenswelt Camino. Eine einführende Einordnung. S. 113–37. In Pilgern Gestern und Heute. Soziologische Beiträge zur Religiösen Praxis auf dem Jakobsweg. Edited by von Heiser Patrick and Christian Kurrat. Berlin and Münster: Lit. [Google Scholar]

- Heiser, Patrick, and Christian Kurrat. 2015. Pilgern zwischen individueller Praxis und kirchlicher Tradition. Berliner Theologische Zeitschrift 32: 133–58. [Google Scholar]

- Herbers, Klaus. 1984. Der Jakobuskult des 12. Jahrhunderts und der "Liber Sancti Jacobi": Studien über das Verhältnis zwischen Religion und Gesellschaft im Hohen Mittelalter. Wiesbaden: Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Herbers, Klaus. 2007. Jakobus—der Heilige Europas. Geschichte und Kultur der Pilgerfahrten nach Santiago de Compostela. Düsseldorf: Patmos. [Google Scholar]

- Herbers, Klaus. 2016. Jakobsweg. Geschichte und Kultur einer Pilgerfahrt. München: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrandt, Frank. 2012. Die Soziologie der Praxis und die Religion—Ein Theorievorschlag. S. 25–60. In Doing Modernity—Doing Religion. Edited by von Daniel Anna, Franka Schäfer, Frank Hillebrandt and Hanns Wienold. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkeling, Hape. 2009. I’m off then. My Journey along the Camino de Santiago. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kurrat, Christian. 2015. Renaissance des Pilgertums: Zur biographischen Bedeutung des Pilgerns auf dem Jakobsweg. Berlin and Münster: Lit. [Google Scholar]

- Kurrat, Christian. 2019. Biographical motivations of pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 7: 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, Rubén C. 2013. The Camino de Santiago and its contemporary renewal: Pilgrims, tourists and territorial identities. Culture and Religion: An Interdisciplinary Journal 14: 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois González, Rubén C., and Xosé M. Santos Solla. 2015. Tourists and pilgrims on their way to Santiago. Motives, Caminos and final destinations. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 13: 149–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Lucrezia, Rubén C. Lois González, and Belén María Castro Fernandez. 2017. Spiritual Tourism on the way of Saint James and the current situation. Tourism Management Perspectives 24: 225–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, Philipp. 2015. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse, 12th ed. Weinheim: Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Molteni, Francesco, and Ferruccio Biolcati. 2018. Shifts in religiosity across cohorts in Europe: A multilevel and multidimensional analysis based on the European Values Study. Social Compass 65: 413–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neitz, Mary J. 2011. Lived religion: Signposts of where we have been and where we can go from here. In Religion, Spirituality and Everyday Practice. Edited by von Giordan Giuseppe and William H. Swatos. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo, Lluis, Scarlett de Courcier, and Miguel Farias. 2012. Rise of pilgrims on the Camino to Santiago: Sign of change or religious revival? Review of Religious Research 56: 433–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pack, Sasha D. 2018. Revival of the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela: The politics of religious, national, and European patrimony, 1879–1988. The Journal of Modern History 82: 335–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reader, Ian. 2007. Pilgrimage growth in the modern world: Meanings and implications. Religion 37: 210–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, Fritz. 1983. Biographieforschung und narratives Interview. Neue Praxis 13: 283–93. [Google Scholar]

- Schützeichel, Rainer. 2018. Kontexte religiöser Praxis. In Religion im Kontext—Religion in Context: Handbuch für Wissenschaft und Studium. Edited by von Schnabel Annette, Melanie Reddig and Heidemarie Winkel. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sime, Jennifer Naomi. 2009. The Aura of Pilgrimage: Traveling toward Santiago de Compostela in Modern Spain. Ann Arbor: UMI. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For more detailed descriptions of the pilgrim’s biographies see Kurrat (2015, p. 132ff.). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).