Piety, Power, or Presence? Strategies of Monumental Visualization of Patronage in Late Antique Ravenna †

Abstract

1. The Creation of a Visual Language

2. Visual Innovations

3. The Establishment of a Visual Language

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agnellus. 2006. Liber Pontificalis Ecclesiae Ravennatis. Edited by Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis. Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Mediaevalis 199. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Amici, Angela. 2000. Imperatori Divi nella decorazione musiva della chiesa di San Giovanni Evangelista. Ravenna Studi e Ricerche 7: 13–57. [Google Scholar]

- Andaloro, Maria, and Serena Romano. 2002. L’immagine nell’abside. In Arte e Iconografia a Roma: Dal Tardoantico Alla fine del Medioevo. Edited by Maria Andaloro and Serena Romano. Milano: Jaca Book. [Google Scholar]

- Andreescu Treadgold, Irina. 1992a. Materiali, iconografia e committenza nel mosaico ravennate. In Storia di Ravenna. Dall’età bizantina all’età ottoniana. Ecclesiologia, cultura e arte. Edited by Antonio Carile. Venezia: Marsilio, vol. II.2, pp. 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Andreescu Treadgold, Irina. 1992b. The mosaic workshop at San Vitale. In Mosaici a S. Vitale e Altri restauri: Il Restauro in Situ di Mosaici Parietali. Atti del Convegno Nazionale sul Restauro in Situ di Mosaici Parietali (Ravenna, 1–3 Ottobre 1990). Edited by Anna Maria Iannucci, Cesare Fiori and Cetty Muscolino. Ravenna: Longo, pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Andreescu Treadgold, Irina. 2007. I mosaici antichi e quelli ottocenteschi di San Michele in Africisco: Lo studio filologico. In San Michele in Africisco e l’età Giustinianea a Ravenna. Atti del Convegno (Ravenna, Sala Dei Mosaici, 21–22 Aprile 2005). Edited by Claudio Spadoni and Linda Kniffitz. Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana Editoriale, pp. 113–41. [Google Scholar]

- Angiolini Martinelli, Patrizia. 1968. Corpus Della Scultura Paleocristiana, Bizantina ed Altomedioevale di Ravenna. Altari, Amboni, Cibori, Cornici, Plutei con Figure di Animali e con Intrecci, Transenne e Frammenti Vari. Roma: De Luca, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Augenti, Andrea, and Enrico Cirelli. 2016. San Severo and Religious Life in Ravenna during the Ninth and Tenth Centuries. In Ravenna: Its Role in Earlier Medieval Change and Exchange Its Role. Edited by Judith Herrin and Jinty Nelson. London: Institute of Historical Research, pp. 297–322. [Google Scholar]

- Augenti, Andrea, Neil Christie, and Jozsef Laszlovsky, eds. 2017. La Basilica Di San Severo a Classe. Scavi 2006. Bologna: Bononia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Avitus. 2016. Epistolae. Edited by Elena Malaspina. Translated by Marc Reydellet. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini Lippolis, Isabella. 2000. Il ritratto musivo nella facciata interna i S. Apollinare Nuovo a Ravenna. In Atti el VI Colloquio Dell’associazione Italiana per lo Studio e la Coservazione del Mosaico. Edited by Federico Guidobaldi and Andrea Paribeni. Ravenna: Il Girasole, pp. 647–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bardill, Jonathan. 2004. Brickstamps of Constantinople. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Barnish, Samuel J. B. 1985. The wealth of Iulianus Argentarius: Late antique banking and the Mediterranean economy. Byzantion 55: 5–38. [Google Scholar]

- Barsanti, Claudia, and Alessandra Guiglia Guidobaldi. 1992. Gli elementi della recinzione liturgica ed altri frammenti minori nell’ambito della produzione scultorea protobizantina. In San Clemente. La scultura del VI secolo (San Clemente Miscellany IV. 2). Edited by Federico Guidobaldi, Claudia Barsanti and Alessandra Guiglia Guidobaldi. Roma: S. Clementem, pp. 68–270. [Google Scholar]

- Beghelli, Michelle. 2018. Due frammenti di arcata di ciborio e di lastra lapidea da Ravenna, Piazza Kennedy (chiesa di Sant’Agnese). In Medioevo Svelato. Storie dell’Emilia-Romagna Attraverso L’archeologia (Catalogo Della Mostra). Edited by Sauro Gelichi, Cinzia Cavallari and Massimo Medica. Bologna: Ante Quem, pp. 305–6. [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez, José M., and Téogenes Ortego. 1983. Mosaicos Romanos de Soria. Corpus de Mosaicos de España VI. Madrid: Instituto Español de Arqueología "Rodrigo Caro" del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanović, Jelena. 2017. The Framing of Sacred Space: The Canopy and the Byzantine Church (ca. 300–1500). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bovini, Giuseppe. 1956. Note sul presunto ritratto musivo di Giustiniano in S. Apollinare Nuovo di Ravenna. Annales Uniansitatis Saradmsis, Philosophie-Lettres 5: 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bovini, Giuseppe. 1957. Massimiano di Pola arcivescovo di Ravenna. Felix Ravenna 74: 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bovini, Giuseppe. 1974. Note sulle iscrizioni e sui monogrammi della zona inferiore del Battistero della Cattedrale di Ravenna. Felix Ravenna 107–8: 89–130. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Thomas S. 1979. The Church of Ravenna and the imperial administration in the seventh century. The English Historical Review 94: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, Leslie. 1997. Memories of Helena: Patterns in imperial female matronage in the fourth and fifth centuries. In Women, Men and Eunuchs. Gender in Byzantium. Edited by Liz James. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 52–75. [Google Scholar]

- Caillet, Jean-Pierre. 2003. L’affirmation de l’autorité de l’êvêque dans les sanctuaires palêochrétiens du haut Adriatique: De l’inscription à l’image. Δελτίον Τῆς Χριστιανικῆς Ἀρχαιολογικῆς Ἑταιρείας 24: 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Carile, Maria Cristina. 2012. The Vision of the Palace of the Byzantine Emperors as a Heavenly Jerusalem. Spoleto: CISAM. Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo. [Google Scholar]

- Carile, Maria Cristina. 2016a. Imperial icons in Late Antiquity and Byzantium. The iconic image of the emperor between representation and presence. Ikon 9: 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carile, Maria Cristina. 2016b. Memories of buildings? Messages in Late Antique architectural representations. In Images of the Byzantine World. Visions, Messages and Meanings. Edited by Angeliki Lymberopoulou. New York: Routledge, pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Carile, Maria Cristina. 2018. Imperial bodies and sacred space? Imperial family images between monumental decoration and space definition in Late Antiquity and Byzantium. In Perceptions of the Body and Sacred Space in the Medieval Mediterranean. Edited by Jelena Bogdanović. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Carile, Maria Cristina. 2019. Forms and ideas in the fifth-century Mediterranean: Bishop Neon and his mosaics in Ravenna. In La circolazione del Mosaico nell’Alto Medioevo. Idee, Forme, maestranze e materiali. Edited by Valentina Cantone. Roma: Viella, pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Caroli, Martina. 2005. Culto e commercio delle reliquie a Ravenna nell’Alto Medioevo. Bizantinistica 7: 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cartocci, Maria Cecilia. 1993. Alcune precisazioni sulla intitolazione a S. Agata della ‘Ecclesia Gothorum’ alla Suburra. In Teoderico il Grande e i Goti d’Italia. Atti del XIII Congressoiinternazionale di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo (Milano, 2–6 Novembre 1992). Spoleto: CISAM, Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, pp. 611–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ciampini, Giovanni. 1690. Vetera Monimenta, in Quibus Praecipue Musiva Opera Sacrarum, Profanarumque Aedium Structura, ac, Nonnulli Antiqui Ritus, Dissertationibus, Iconibusque Illustrantur. Roma: Ex Typohtaphia Joannis Jacobi Komarek Bohemi, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli, Enrico. 2008. Ravenna: Archeologia di una Città. Firenze: All’Insegna del Giglio. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, Salvatore. 2006. Le fortune di un banchiere tardoantico. Giuliano Argentario e l’economia di Ravenna nel VI secolo. In Santi, Banchieri, Re: Ravenna e Classe nel VI Secolo. San Severo il Tempio Ritrovato. Edited by Andrea Augenti and Carlo Bertelli. Milano: Skira, pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, Salvatore. 2014a. Banking in early Byzantine Ravenna. Cahiers de Recherches Médiévales et Humanistes 28: 243–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, Salvatore. 2014b. Constans II, Ravenna’s autocephaly and the panel of the privileges in St. Apollinare in Classe: A reappraisal. In Aureus. Volume Dedicated to Prof. Evangelos K. Chrysos. Edited by Taxiarchis G. Kolias and Konstantinos G. Pitsakis. Athens: Institute of Historical Research—NHRF Section of Byzantine Research, pp. 153–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, Salvatore. 2020. Bankers as patrons in Late Antiquity. In I Longobardi a Venezia. Scritti per Stefano Gasparri. Edited by Irene Barbiera, Francesco Borri and Annamaria Pazienza. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 235–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ćurčić, Slobodan, and Evangelia Hadjitriphonos. 2010. Architecture as Icon: Perception and Representation of Architecture in Byzantine Art, Exhibition Catalogue (Tessaloniki, Museum of Byzantine Culture, 6 November 2009–31 January 2010; Princeton, University Art Museum, 6 March−6 June 2010). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deichmann, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1951. Giuliano Argentario. Felix Ravenna, s. 3 56: 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Deichmann, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1974. Ravenna. Hauptstadt Des Spatantiken Abendlandes, II.1, Kommentar. Wiesbaden: Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Deichmann, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1976. Ravenna. Hauptstadt Des Spatantiken Abendlandes, II.2, Kommentar. Wiesbaden: Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Deichmann, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1989. Ravenna. Hauptstadt Des Spätantiken Abendlandes, II.3, Kommentar. Stuttgart: F. Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Delbrueck, Richard. 1929. Die Consulardiptychen Und Verwandte Denkmäler. Berlin-Leipzig: Walter de Gruyter, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Duval, Noël. 1994. Note sur un linteau mystérieux. In Salona I. Recherches Archéologiques Franco-Croates à Salone. Catalogue de la Sculpture Architecturale Paléochrétienne de Salone. Edited by Noël Duval, Emilio Marin, Catherine Metzger, Pascale Chevalier and Marie-Pascale Flèche Mourgues. Rome: École Française de Rome, pp. 313–14. [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond, Antony. 2016. Monograms and the art of unhelpful writing in Late Antiquity. In Sign and Design. Script as Image in Cross-Cultural Perspective (300–1600 CE). Edited by Brigitte Miriam Bedos-Rezak and Jeffrey F. Hamburger. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, pp. 219–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrua, Antonio. 1961. Lavori a S. Sebastiano. Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana 37: 227–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, Walter Otto. 1981. Das frühbyzantinische Monogramm. Untersuchungen zu Lösungsmöglichkeiten. Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik 30: 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, Walter Otto. 1984. Neue Deutungsvorschläge zu einigen byzantinischen Monogrammen. In Byzantios. Festschrift für Herbert Hunger zum 70. Geburtstag. Edited by Wolfram Hörandner, Johannes Koder, Otto Kresten and Erich Trapp. Wien: E. Becvar, pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, Walter Otto, and Werner Seibt. 1981. Neue Wege zur Deutung der Monogramma. Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik 31: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Frugoni, Chiara. 1983. Una lontana città: Sentimenti e immagini nel Medioevo. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Siegfried. 1943. Bildnisse und Denkmäler aus dem Ostgotenzeit. Die Antike 19: 109–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gardini, Giovanni, and Paola Novara, eds. 2011. Le collezioni del Museo Arcivescovile di Ravenna. Ravenna: Museo Arcivescovile di Ravenna. [Google Scholar]

- Gardthausen, Viktor Emil. 1966. Das alte Monogramm, 2nd ed. Stuttgart: K. W. Hiersemann. [Google Scholar]

- Garipzanov, Ildar. 2018. Graphic Signs of Authority in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, 300–900. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grierson, Philip, and Melinda Mays. 1992. Catalogue of the Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and in the Whittemore Collection. From Arcadius and Honorius to the Accession of Anastasius. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Martin. 1989. A Temple for Byzantium. The Discovery and Excavation of Anicia Juliana’s Palace-Church in Istanbul. London: Harvey Miller. [Google Scholar]

- Herrin, Judith. 2020. Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hülsen, Christian, ed. 1924. Sant’Agata dei Goti. Roma: Sansaini. [Google Scholar]

- Iannucci, Anna Maria. 1984. Una ricognizione al Battistero Neoniano. Corsi di Cultura sull’Arte Ravennate e Bizantina 31: 296–339. [Google Scholar]

- Iannucci, Anna Maria. 1986. I vescovi Ecclesius, Severus, Ursus, Ursicinus, le scene dei privilegi e dei sacrifici in S. Apollinare in Classe. Corsi di Cultura sull’Arte Ravennate e Bizantina 33: 165–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovici, Vladimir. 2016. Manipulating Theophany. Light and Ritual in North Adriatic Architecture (ca. 400–ca. 800). Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Jastrzebowska, Elzbieta. 2002. S. Sebastiano, la più antica basilica cristiana di Roma. In Ecclesiae Urbis. Atti del congresso internazionale di studi sulle chiese di Roma (IV-X Secolo) (Roma, 4–10 settembre 2000). Edited by Federico Guidobaldi and Alessandra Guiglia Guidobaldi. Città del Vaticano: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, vol. 2, pp. 1141–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Mark. 1988. Toward a history of Theodoric’s building program. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 42: 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkenberg, Samuel. 2009. Com-Pressed Meanings. The Donor’s Model in Medieval Art to around 1300. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Kostof, Spiro K. 1965. The Orthodox Baptistery of Ravenna. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzke, Christine, and Uwe Albrecht, eds. 2008. Mikroarchitektur im Mittelalter: Ein gattungsübergreifendes Phänomen Zwischen Realität Und Imagination. Beiträge der Gleichnamigen Tagung im Germanischen Nationalmuseum Nürnberg vom 26. bis 29. Oktober 2005. Leipzig: Kratzke. [Google Scholar]

- L’Orange, Hans Peter. 1982. Studies on the Iconography of Cosmic Kingship in the Ancient World, 2nd ed. New Rochelle and New York: Caratzas Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Lavers, Marina. 1971. I cibori d’altare delle chiese di Classe e Ravenna. Felix Ravenna 102: 131–215. [Google Scholar]

- Leatherbury, Sean V. 2020. Inscribing Faith in Late Antiquity: Between Reading and Seeing. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lechner, Martin. 1978. Imago clipeata. In Reallexikon zur byzantinischen Kunst. Stuttgart: A. Hiersemann, vol. 3, pp. 353–69. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, Henri. 1934. Monogramme. In Dictionnaire D’archeologie Chretienne et de Liturgie. Paris: Librairie Letouzey et Ane, vol. XI.2, pp. 2369–92. [Google Scholar]

- Liverani, Paolo. 2006. Costantino offre il modello della basilica sull’arco trionfale. In L’orizzonte Tardoantico e le Nuove Immagini 312–468 (La Pittura Medievale a Roma, 312–1431, 1). Edited by Maria Andaloro. Milano: Jaca Book, pp. 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- Liverani, Paolo. 2007. L’architettura costantiniana, tra committenza imperiale e contributo delle élites locali. In Konstantin der Grosse. Geschichte—Archäologie—Rezeption. Edited by Alexander Demandt and Josef Engemann. Trier: Rheinische Landesmuseum, pp. 235–44. [Google Scholar]

- Longhi, Davide. 1996. Epigrafi votive di epoca placidiana in S. Giovanni Evangelista a Ravenna e in S. Croce di Gerusalemme a Roma. Felix Ravenna 149–52: 39–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lorentz, Friedrich. 1935. Theoderich-Nicht Justinian. Römische Mitteilungen 50: 339–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi, Giovanni. 1967. Orso. In Bibliotheca Sanctorum. Roma: Città Nuova, vol. 9, pp. 1248–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi, Giovanni. 1968. Severo. In Bibliotheca Sanctorum. Roma: Città Nuova, vol. 11, pp. 997–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg, Simon. 2014. Triumphal arches and gates of piety at Constantinople, Ravenna and Rome. In Using Images in Late Antiquity. Edited by Stine Birk, Troels Myrup Kristensen and Birte Poulsen. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 150–89. [Google Scholar]

- Mango, Cyril, and Ihor Sěvčenko. 1961. Remains of the church of St. Polyeuktos at Constantinople. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 15: 243–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, Čedomila. 2007. Founder’s Model—Representation of a Maquette of a Church? Zbornik Radova Vizantološkog Instituta 44: 145–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, Čedomila. 2013. Principles of the representation of the founder’s (Ktetor’s) architecture in Serbian Medieval and Byzantine art. In Serbia and Byzantium. Proceedings of the International Conference Held on 15 December 2008 at the University of Cologne. Edited by Claudia Sode and Mabi Angar. Frankfurt am Main and New York: PL Academic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Marsengill, Katherine. 2013. Portraits and Icons. Between Reality and Spirituality in Byzantine Art. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen, Ralph W. 2009. Ricimer’s church in Rome: How an arian barbarian prospered in a nicene world. In The Power of Religion in Late Antiquity. Edited by Andrew Cain and Noel Lenski. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 307–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mauskopf Deliyannis, Deborah, ed. 2004. Agnellus of Ravenna, The Book of Pontiffs of the Church of Ravenna. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mauskopf Deliyannis, Deborah. 2010. Ravenna in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mauskopf Deliyannis, Deborah. 2016. Episcopal commemoration in late fifth-century Ravenna. In Ravenna: Its Role in Earlier Medieval Change and Exchange. Edited by Judith Herrin and Jinty Nelson. London: Institute of Historical Research, pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzotti, Mario. 1950. Massimiano di Pola. Pagine Istriane 1: 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzotti, Mario. 1956. L’attività edilizia di Massimiano di Pola. Felix Ravenna 71: 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Michon, Étienne. 1905. Antiquités gréco- romaines provenant de Syrie: Conservées au Musée de Louvre. Revue Biblique 2: 564–78. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, Christine. 1996. ‘Lignum Vitae’ or ‘Crux Gemmata’? The cross on Golgotha in the early Byzantine period. Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 20: 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, Giovanni. 1991. Massimiano arcivescovo di Ravenna (546–556) come committente. Studi Romagnoli 42: 368–416. [Google Scholar]

- Muscolino, Cetty. 2011. Restauri Passati. In Il Battistero Neoniano. Uno Sguardo Attraverso il Restauro. Edited by Antonella Ranaldi, Cetty Muscolino and Claudia Tedeschi. Ravenna: Longo, pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri Farioli, Raffaella. 1969. Corpus Della Scultura Paleocristiana, Bizantina ed Altomedioevale di Ravenna: Basi, Capitelli, Pietre D’imposta, Pilastri e Pilastrini, Plutei, Pulvini. Edited by Giuseppe Bovini. Roma: De Luca, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Olovsdotter, Cecilia. 2005. The Consular Image. An Iconological Study of the Consular Diptychs. Oxford: John and Erica Hedges. [Google Scholar]

- Omari, Elda. 2014. Pavimenti a commessi laterizi con monogrammi. Le sponde del basso Adriatico a confronto: Puglia e Albania. In Atti del XIX Colloquio Dell’associazione Italiana per lo Studio e la Conservazione del Mosaico (AISCOM) (Isernia, 13–16 Marzo 2013). Roma: Edizioni Quasar, pp. 541–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ortenberg West-Harling, Veronica. 2016. The Church of Ravenna, Constantinople and Rome in the seventh Century. In Ravenna: Its Role in Earlier Medieval Change and Exchange. Edited by Judith Herrin and Jinty Nelson. London: Institute of Historical Research, pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, John, and Amanda Claridge. 1996. The Paper Museum of Cassiano Dal Pozzo, Early Christian and Medieval Antiquities. Paintings and Mosaics in Roman Churches. London: Harvey Miller Publishers, vol. II.2. [Google Scholar]

- Penni Iacco, Emanuela. 2004. La basilica di S. Apollinare Nuovo di Ravenna attraverso i Secoli. Bologna: Ante Quem. [Google Scholar]

- Priess, Baurat. 1927. Ein vergessenes Mosaik-Bildnis Theoderichs des Grossen in Ravenna. Zeitschrift für Bauwesen 77: 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, Corrado. 1902. Le tarsie marmoree dell’abside di San Vitale. Rassegna d’Arte 49: 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, Corrado. 1905. Monumenti veneziani nella Piazza di Ravenna. Rivista d’Arte 3: 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, Corrado. 1931. Battistero della Cattedrale (Monumenti: Tavole Storiche dei Mosaici di Ravenna 2). Roma: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, Corrado. 1934. Cappella Arcivescovile (Oratorio Di S. Andrea) (Monumenti: Tavole storiche dei mosaici di Ravenna 5). Roma: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato. [Google Scholar]

- Romanelli, Rita. 2011. Reimpieghi a Ravenna tra X e XII Secolo nei Campanili, Nelle Cripte e Nelle Chiese. Spoleto: CISAM. Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, Girolamo. 1589. Historiarum Ravennatum Libri Decem, 2nd ed. Venetiis: Ex typographia Guerraea. [Google Scholar]

- Roueché, Charlotte, and Denis Feissel. 2007. Interpreting the signs: Anonymity and concealment in late antique inscriptions. In From Rome to Constantinople. Studies in Honour of Averil Cameron. Edited by Amirav Hagit and Robert Barend ter Haar Romeny. Leuven: Brill, pp. 221–34. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, Eugenio. 1989. Scavi e scoperte nella chiesa di S. Agata di Ravenna. Notizie preliminari. In Actes du XIe Congrès International D’archéologie Chrétienne (Lyon, Vienne, Grenoble, Genève, Aoste, 21–28 Septembre 1986) (Publications de l’École Française de Rome, 123). Rome: École Française de Rome, pp. 2317–41. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, Eugenio. 1991. Sculture del Complesso Eufrasiano di Parenzo. Napoli: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, Eugenio. 2003. L’architettura di Ravenna Paleocristiana. Venezia: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti. [Google Scholar]

- Savini, Gaetano. 1914. Per i Monumenti e per la Storia di Ravenna. Ravenna: Scuola Tipografica Salesiana. [Google Scholar]

- Seibt, Werner. 2016. The use of monograms on Byzantine seals in the early Middle-Ages (6th to 9th centuries). Parekbolai 6: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Simson, Otto G. Von. 1948. Sacred Fortress: Byzantine Art and Statecraft in Ravenna. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spier, Jeffrey. 2010. Some unconventional early Byzantine rings. In Intelligible Beauty. Recent Research on Byzantine Jewellery. Edited by Chris Entwistle and Nöel Adams. London: British Museum Press, pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Spieser, Jean-Michel. 2015. Images du Christ: Des catacombes aux lendemains de l’iconoclasme. Genève: Droz. [Google Scholar]

- Stachowiak, Dominik. 2018. Church Models in the Byzantine Culture Circle and the Problem of Their Function. In NOVAE Studies and Materials VI. Edited by Elena Ju Klenina. Poznan: Instytut Historii UAM, pp. 243–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stroth, Fabian. 2021. Die Monogrammkapitelle der Hagia Sophia, der Sergios- und Bakchos-kirche und der Irenenkirche. Die justianische Bauskulptur Konstantinopels als Textträger. Wiesbaden: Reichert. [Google Scholar]

- Symmachus. 2002. Epistolae. Edited by G. A. Cecconi. Pisa: Giardini. [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, Arthur. 2005. Donation, dedication, and damnatio memoriae: The catholic reconciliation of Ravenna and the church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo. Journal of Early Christian Studies 13: 71–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeule, Cornelius C. 1965. A Greek theme and its survivals: The ruler’s shield (tondo image) in tomb and temple. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 109: 361–97. [Google Scholar]

- Volbach, Wolfgang Fritz. 1976. Elfenbeinarbeiten der Spätantike und des frühen Mittelalters. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Volkoff, Angelina Anne. 2019. Power, family, and identity: Social and personal elements in Byzantine sigillography. In A Companion to Seals in the Middle Ages. Edited by Laura Whatley. Leiden: Brill, pp. 223–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, Giuliano. 2002. Il mattone di Iohannis. San Giusto (Lucera, Puglia). In Humana Sapit. Etudes D’antiquité Tardive Offertes à Lellia Cracco-Ruggini. Edited by Jean-Michel Carrié and Rita Lizzi Testa. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Perkins, Bryan. 2010. Where is the archaeology and iconography of Germanic arianism? In Religious Diversity in Late Antiquity (Late Antique Archaeology 6). Edited by David M. Gwynn and Susanne Bangert. Leiden-Boston: Brill, pp. 265–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Roger J. A. 2020. Philippianus: A late Roman Sicilian landowner and his use of the monogram. In People and Institutions in the Roman Empire. Essays in Memory of Garrett G. Fagan (Mnemosyne Supplement HACA 437). Edited by Andrea F. G Gatzke, Lee L. Brice and Matthew Trundle. Leiden: Brill, pp. 183–230. [Google Scholar]

- Zangara, Vincenza. 2000. Una predicazione alla presenza dei principi: La chiesa di Ravenna nella prima metà del sec. V. Antiquité Tardive 8: 265–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | For the basilica of San Giovanni Evangelista, still extant in today Ravenna, see (Russo 2003, pp. 23–41; Mauskopf Deliyannis 2010, pp. 63–70). On Galla Placidia’s building, most recently: (Herrin 2020, pp. 46–60). |

| 2 | On the basis of her philological reading of Agnellus, Vincenza Zangara suggests that Melchizedek, and not the bishop, was portrayed here (Zangara 2000, pp. 290–92). |

| 3 | Most probably these portraits decorated the intrados of the triumphal arch as portraits into roundels are located on the intrados of the greatest part of late antique triumphal arches across the Mediterranean; see, for instance, the medallions with female saints in the sixth-century Euphrasian Basilica at Poreć or the portraits of the apostles in the sixth-century churches of San Vitale in Ravenna and of Lythrangomi at Cyprus. Still, as evidenced in 16th-century drawings of S. Sabina at Rome (Ciampini 1690, t. 47), in the fifth century they could have been located around the triumphal arch. |

| 4 | Ravenna, Biblioteca Classense, Cod. 406, f. 11v, anonymous’ Tractatus hedificationis et constructionis ecclesie Sancti Johannis Evangeliste de Ravena. For discussion on this manuscript illumination: (Carile 2018, pp. 60–61). |

| 5 | Galla Placidia Augusta pro se et his omnibus hoc votum solvit (Rossi 1589, p. 101; CIL 11.276; ILS 818; RIS 1.2. 568, 570). Translation: “The Empress Galla Placidia fulfilled this vow on behalf of herself and all of these”. |

| 6 | Sancto ac beatissimo apostolo Iohanni euangelistae, Galla Placidia augusta cum filio suo Placido Valentiniano augusto et filia sua Iusta Grata Honoria augusta liberationis periculum maris uotum soluent (Agnellus 2006, LP, 42; Rossi 1589, p. 101; CIL 11.276; ILS 818; ILCV 20). Translation: (Malmberg 2014, p. 174). For discussion on the inscriptions, see (Longhi 1996; Amici 2000, p. 32; Zangara 2000, pp. 281–82; Malmberg 2014, pp. 174–75). |

| 7 | Confirma hoc, Deus, quod operatus es in nobis; a templo tuo in Ierusalem tibi offerent reges munera (Agnellus 2006, LP, 42; Rossi 1589, p. 102). Translation: “Confirm, o God, that which you have wrought for us; from your temple (in) Jerusalem kings shall offer you gifts” (Malmberg 2014, p. 174). For discussion, see (Amici 2000, p. 32; Longhi 1996, pp. 54–55; Carile 2018, p. 62). |

| 8 | Amore Christi nobilis et filius tonitrui Sanctus Iohannes arcana vidit (CIL 11.276b; ILS 818,2; ILCV 20b). Translation: “Noble for (his) love in Christ and the son of thunder, St. John saw the secrets.” Discussion in (Deichmann 1974, p. 109; Longhi 1996; Zangara 2000, p. 282). |

| 9 | The furnishing would have included a marble enclosure, perhaps an iconostasis and a canopy, which according to written sources was largely used in Ravenna. For a complete catalogue of the canopies with discussion of written sources: (Lavers 1971). Most recently fragments of another late antique canopy were discovered in the excavation of the basilica of Sant’Agnese: (Beghelli 2018). For the canopy in church architecture and liturgy, see (Bogdanović 2017). |

| 10 | The fact Galla Placidia, Valentinian, and Honoria were mentioned in the central part of the inscription suggests that their names would have been visible in the exact center of the space. On the comprehension of inscriptions by the late antique beholder, see most recently (Leatherbury 2020, pp. 14–18). |

| 11 | By tradition, the church built in the second half of the fifth century and probably restored in the sixth century (Deichmann 1976, pp. 283–97; Russo 2003, pp. 127–30) is associated with Bishop John Angeloptes; however, no source clearly attests that its foundation should be attributed to him. |

| 12 | Theodoricus rex hanc ecclesiam a fundamentis in nomine Domini nostri Iesu Christi fecit. Translation: “King Theoderic made this church from its foundations in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Mauskopf Deliyannis 2004, p. 200). For this church, see (Deichmann 1974, p. 128; Johnson 1988, pp. 85–86; Urbano 2005, pp. 75–76). |

| 13 | The apse mosaic of Sant’Andrea in Catabarbara, a fourth-century building transformed into Arian church in the second half of the fifth century, can be seen in Antonio Eclissi’s drawings (c. 1630), now held in the Dal Pozzo Collection of the Windsor Castle in London (WRL 9033) (Osborne and Claridge 1996, pp. 78–81). For the apse of Sant’Agata dei Goti fundamental are Alfonso Ciacconio’s 16th-century reproductions, see (Vatican City, Ms. Vat. lat. 5407) (Hülsen 1924, pp. 25–26, 192). |

| 14 | For a summary of scholarly hypotheses on the lost mosaics, see (Carile 2012, pp. 129–56). |

| 15 | In the mansion of the rich Philippianus at Gerace in Southern Italy, roof tiles, bricks, and floor mosaics bear the owner’s monogram (Wilson 2020). They are also found in the mosaics of the villa at Cuevas de Soria in Spain (Blázquez and Ortego 1983). |

| 16 | The monogram found on a threshold in the basilica of San Sebastiano at Rome was interpreted as Constantine’s or one’s of his sons (Ferrua 1961), but it may have not belonged to the original structure (Jastrzebowska 2002, p. 1151 n. 21). In the late fifth and sixth centuries, episcopal, aristocratic, or imperial monograms often decorated the floor tiles of monumental buildings in Apulia and Albania (Volpe 2002; Omari 2014). |

| 17 | According to Ildar Garipzanov’s extensive analysis, the first monograms in monumental settings should be attributed to Theoderic. However, he does not exclude that, in the East, monograms were already used in monumental architecture (Garipzanov 2018, pp. 166–67). |

| 18 | Such monograms are found on Maximian’s ivory chair and on an impost block now at the Museo Arcivescovile (Bovini 1974, pp. 116–20; Olivieri Farioli 1969, p. 86 no. 183). |

| 19 | This would be in contrast with the widespread use of block-monograms in the sixth century (Seibt 2016; Fink 1981). |

| 20 | Nevertheless, Deichmann excludes the possibility that the monograms were original (Deichmann 1974, p. 16). |

| 21 | According to a close-up analysis of the mosaic fragments, at Sant’Agata, the apse mosaic belonged to the sixth-century phase of the building under Archbishop Agnellus (Russo 1989, pp. 2323–24). However, in the fifth century, the apse could feature a similar scene with Christ at the centre of the apse, an iconography quite common at that time (Spieser 2015, pp. 317–97). |

| 22 | Cede, uetus nomen, nouitati cede uetustas! / Pulchrius ecce nitet renouati gloria Fontis. / Magnanimus hunc namque Neon summus que sacerdos / Excoluit, pulchro componens omnia cultu. Translation: “Yield, old name, yield, age, to newness! Behold the glory of the renewed font shines more beautifully. For generous Neon, highest priest, has adorned it, arranging all things in beautiful refinement” (Mauskopf Deliyannis 2004, p. 125). |

| 23 | On the monograms of Justinian’s churches at Constantinople, see Fabian Stroth’s much awaited monograph (Stroth 2021). Later in the sixth century, the use of monograms on monumental architecture spread in buildings promoted by emperors and bishops alike, as testified at San Clemente at Rome and the churches of Northern Adriatic (Barsanti and Guiglia Guidobaldi 1992, pp. 154–55; Garipzanov 2018, pp. 186–95, with references). |

| 24 | On the value of seals as legitimating a document and providing the mark of the responsible for that document even by means of a monogram (Fink and Seibt 1981; Spier 2010, pp. 15–16). |

| 25 | These monograms are the result of 19th-century interventions (Ricci 1934, t. 41–42), therefore they cannot be considered in this inquiry. |

| 26 | Fecit que non longe ab eadem domo monasterium sancti Andreae apostoli; sua que effigies super ualuas eiusdem monasterii est inferius tessellis depicta. Translation: “And not far from that house he built the monasterium of St. Andrew the apostle, and his image is depicted in mosaic inside this monasterium, over the doors” (Mauskopf Deliyannis 2004, p. 162). |

| 27 | This opinion is perhaps influenced by the major importance attributed by Agnellus to Maximian’s translation of St. Andrew’s relics from Constantinople to Ravenna (Agnellus 2006, LP, 76). |

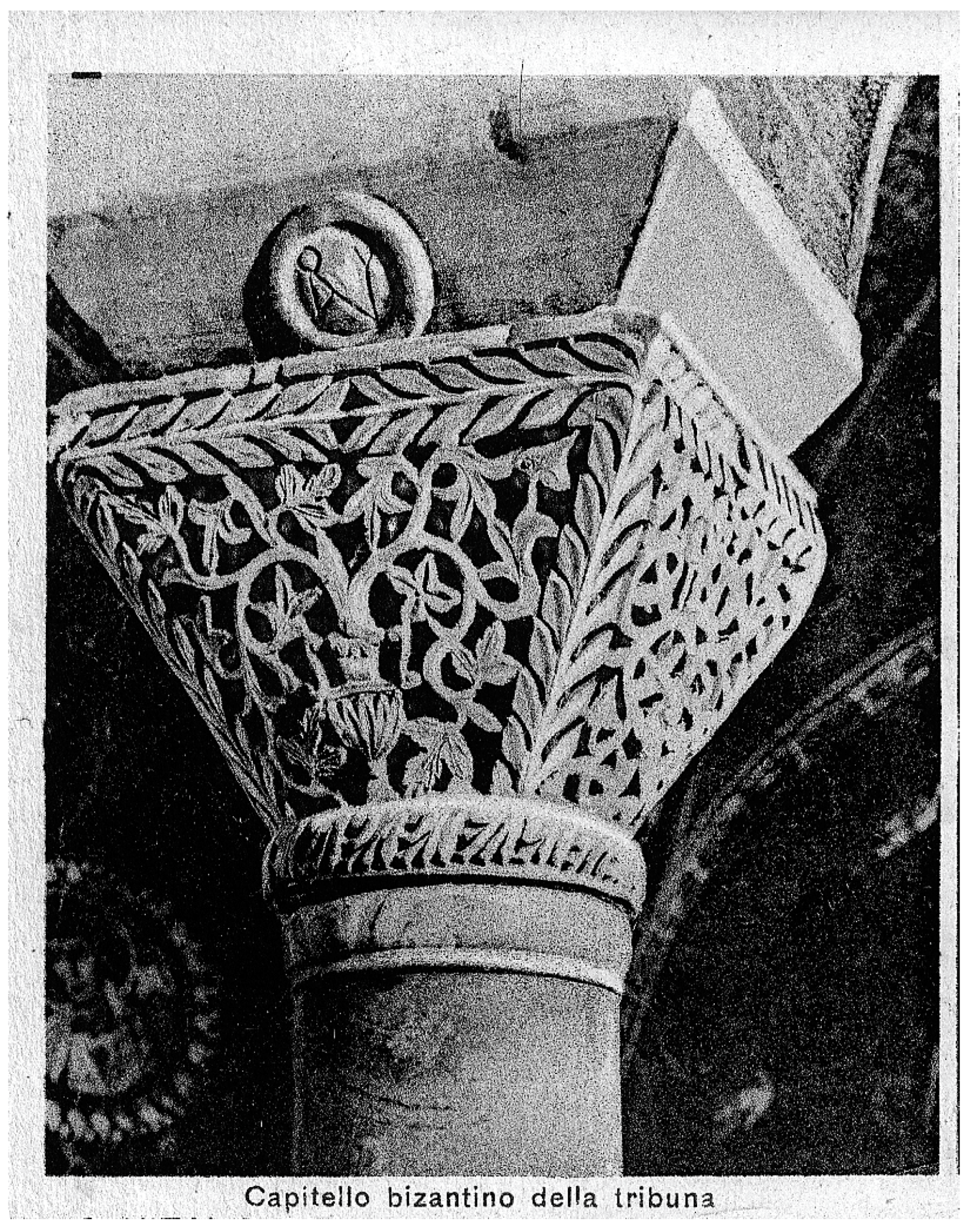

| 28 | The capitals are now held at the Museo Arcivescovile (inv. no. 69–70) (Gardini and Novara 2011). |

| 29 | On one capital are inscribed the words “PETRUS EPISC(opus) S(an)CTE(=ae) RAVEN(natis) ECCL(esiae) COEPTUM OPUS” and on the other “(a) (fund)AMENTIS IN HONORE S(an)C(to)R(u)M PEREECIT (=perfecit)”, translation “Peter, Bishop of the holy Church of Ravenna, completed this work started from its foundation in honor of the saints.” |

| 30 | The iconography of the church founder with the model in his hands spread in the Middle Ages across boundaries and cultures (for the Balkans: Marinković 2007, 2013; Stachowiak 2018; for the west: Klinkenberg 2009; more generally for models: Kratzke and Albrecht 2008; Ćurčić and Hadjitriphonos 2010). |

| 31 | Dedication inscription: Ardua consurgunt uenerando culmine templa / Nomine Vitalis sanctificata Deo./Geruasius que tenet simul hanc Protasius arcem, / Quos genus atque fides templa que consociant. / His genitor natis fugiens contagia mundi/Exemplum fidei martirii que fuit./Tradidit hanc primus Iuliano Ecclesius arcem, / Qui sibi commissum mire peregit opus./Hoc quoque perpetua mandauit lege tenendum,/His nulli liceat condere membra locis. / Sed quod pontificum constant monumenta priorum,/Fas ibi sit tantum ponere seu simile (Agnellus 2006, LP, 61). Translation: “The lofty temples rise to the venerable rooftop, sanctified to God in the name of Vitalis. And Gervase and Protase also hold this stronghold, whom family and faith and church join together. The father fleeing the contagions of the world was to these sons an example of faith and martyrdom. Ecclesius first gave this stronghold to Julian, who wonderfully completed the work commissioned to him. He also ordered it to be maintained by perpetual law that in these places no one’s body is permitted to be placed. But because tombs of earlier bishops are established here, it is allowed to place this one, or one like it” (Mauskopf Deliyannis 2004, p. 177). |

| 32 | Consecration inscription: Beati martiris Vitalis basilicam, mandante Ecclesio uiro beatissimo episcopo, a fundamentis Iulianus argentarius aedificauit, ornauit atque dedicauit, consecrante uiro reuerendissimo Maximiano episcopo, sub die .xiii. [kal. Maiarum, indictione .x.,] sexies p. c. Basilii iunioris (Agnellus 2006, LP, 77). Translation: “Julian the Banker built the basilica of the blessed martyr Vitalis from the foundations, authorized by the vir beatissimus Bishop Ecclesius, and decorated and dedicated it, with the vir reverendissimus Bishop Maximian, consecrating it on April 19, in the tenth indiction, the sixth year after the consulship of Basilius” (Mauskopf Deliyannis 2004, p. 192). |

| 33 | According to Agnellus, a similar inscription was placed in the narthexes of San Vitale and Sant’Apollinare in Classe that Maximian consecrated in 549. For the text and translation, see above n. 32. |

| 34 | [..] et in cameris tribunae sua effigies tessellis uariis infixa est (Agnellus 2006, LP, 72). Translation: “in the vaults of the apse his image is fixed in multicolored mosaic” (Mauskopf Deliyannis 2004, p. 187) (Mazzotti 1950, 1956; Bovini 1957; Montanari 1991). Possibly this was a full figure portrait, such as Ecclesius’s at San Vitale. |

| 35 | Consecration inscription: In honore sancti ac beatissimi primi martiris Stephani seruus Christi Maximianus episcopus hanc basilicam, ipso adiuuante, a fundamentis construxit et dedicauit die tertio Idus Decemb., indictione .xiiii., nouies p. c. Basilii iunioris (Agnellus 2006, LP, 72). Translation: “In honor of the holy and most blessed first martyr Stephen, Bishop Maximian, servant of Christ, by God’s grace built this church from the foundations and dedicated it on December 11 in the fourteenth indiction, in the ninth year after the consulship of Basilius the younger” (Mauskopf Deliyannis 2004, p. 187). Dedication inscription on the triumphal arch: Templa micant Stephani meritis et nomine sacra,/Qui prius eximium martiris egit opus./Omnibus una datur sacro pro sanguine palma, / Plus tamen hic fruitur, tempore quo prior est./Ipse fidem uotum que tuum nunc, magne sacerdos / Maximiane, iuuans, hoc opus explicuit. / Nam talem subito fundatis molibus aulam/Sola manus hominum non poterat facere. / Vndecimum fulgens renouat dum luna recursum / Excepta et pulchro condita fine nitet (Agnellus 2006, LP, 72). Translation: “The temple of Stephen shines, holy in relics and in name, he who first performed the exceptional act of martyrdom. The same palm is given to all for holy blood; however he benefits from it more who was earlier in time. He himself now assisting your faith and your vow, great priest Maximian has completed this work. For the hand of man alone could not so soon have made such a hall from its foundation walls. When the gleaming moon was new for the eleventh time, the church which had been begun shines established in beautiful completion” (Mauskopf Deliyannis 2004, p. 188). |

| 36 | For the barracks of the Bandus Primus, see (Deichmann 1989, p. 40). |

| 37 | See above footnote n. 18. |

| 38 | |

| 39 | Namely, the greatest sixth-century churches of San Vitale and Sant’Apollinare in Classe, and the basilica of San Michele in Africisco; Agnellus’ attribution of the church Santa Maria Maggiore to Julianus’ munificence is dubious (Agnellus 2006, LP, 57, 59, 61, 63, 77). For discussion: (Deichmann 1951; Deichmann 1976, pp. 3–33; Barnish 1985; Caillet 2003; Cosentino 2006, 2014a, 2020). |

| 40 | See the dedicatory inscription set in silver tesserae in the atrium of San Vitale at footnote 31, the consecration inscription in the narthex of the same church at footnote 32. |

| 41 | Consecration inscription in the narthex of the basilica: Beati Apolenaris sacerdotis basilicam, mandante uiro beatissimo Vrsicino episcopo, a fundamentis Iulianus argentarius aedificauit, ornauit atque dedicauit, consecrante uiro beato Maximiano episcopo, die .vii. id. Maiarum, indictione .xii., octies p. c. Basilii (Agnellus 2006, LP, 77). Translation: “Julian the Banker built the basilica of the blessed priest Apollinaris from the foundations, authorized by the vir beatissimus bishop Ursicinus, and decorated it and dedicated it, with the vir beatus bishop Maximian consecrating it on May 9, in the twelfth indiction of the eight year after the consulship of Basilius” (Mauskopf Deliyannis 2004, pp. 191–92). For discussion on the inscriptions, see expecially: (Deichmann 1976, pp. 4–11; Caillet 2003). |

| 42 | For the dedication inscription in the atrium and the consecration inscription in the narthex of the church (Agnellus 2006, LP, 61, 77) see above footnote 31 and 32. The inscription on the reliquary now held at the Museo Nazionale in Ravenna is the following: Iulianus argent(arius) servus vest(er) praecib(us) vest(ris) basi(licam) a funda(mentis) perfec(it). Translation: “Julian the Banker, your servant took to completion this basilica from its foundations, with prayers to you.” |

| 43 | Another instance is found on a reliquary from El Bassah (Syria) and today at the Louvre, where the deacon Elias had his dedication carved on the lid (Michon 1905, p. 576). |

| 44 | See above footnote 41. For the inscription on Apollinaris’s tomb (CIL XI.1 n. 295): (Deichmann 1951, p. 8; 1976, pp. 4–5). |

| 45 | The opus sectile in the sanctuary of the church was reconstructed at the beginning of the 20th century on the basis of a surviving panel, showing Julian’s monograms at the sides of a porphyry circle, and archive documents; however the reconstruction raised a lively debate at that time (Ricci 1902; Deichmann 1976, pp. 134–35). |

| 46 | On the impost blocks, Julian’s monograms are in Greek, while in the marble slabs of the choir in Latin. |

| 47 | On the inutility of deciphering monograms: (Deichmann 1976; Fink and Seibt 1981; Caillet 2003) with discussion. |

| 48 | Julian’s monogram on the matroneum windows was sculpted in Ravenna according to Deichmann (1976, pp. 103, 111), as if local artisans could not achieve the perfection of artisans from Constantinople and as if artisans from Constantinople were all highly skilled. Indeed, this kind of opinion reflects an idealized vision that does not allow the growth of local proficiency in the provinces and regards art history as a continuous process of improvement. |

| 49 | Maximian was mentioned only in the inscription in the narthex and not in the one in the atrium, but he was immortalized by being depicted beside the emperor in the apse. |

| 50 | For their apparent indecipherability, Garipzanov hypothesizes that they could bear hidden messages directed to a few people who could read them (Garipzanov 2018, p. 163). However, this would be the only instance where monograms include entire messages and not just personal names and titles. |

| 51 | It is worth noting that in ancient sources, the monogram is not considered a word but a signum (Fink 1984, pp. 85–86) and that several monograms of different form belonged to the same person (e.g., Maximian’s monograms on his chair and on the capital described above or Areobindus’s monogram on his diptychs). |

| 52 | For they do not always include the title or office of the person, nor were they established by civil power; rather they hold a private character. |

| 53 | Anthony Eastmond defines monograms as “images that mark the presence of a donor or patron, who therefore becomes more as an abstract concept” (Eastmond 2016, p. 227). |

| 54 | In this sense, sixth-century monograms in monumental contexts may have also had the function to avoid phthonos (the Evil Eye) and magic (Roueché and Feissel 2007). |

| 55 | On the role of seals as a kind of “signature card”: (Volkoff 2019, p. 225). On the value of monograms in Roman antiquity, see also: (Symmachus 2002), Ep.II.12 (c. 385). |

| 56 | At the beginning on the 20th century the fresco was taken to the Museo Nazionale where it is still today. |

| 57 | A cross monogram of difficult reading was later reused in the belltower of the church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo (Romanelli 2011, pp. 120–21). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carile, M.C. Piety, Power, or Presence? Strategies of Monumental Visualization of Patronage in Late Antique Ravenna. Religions 2021, 12, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020098

Carile MC. Piety, Power, or Presence? Strategies of Monumental Visualization of Patronage in Late Antique Ravenna. Religions. 2021; 12(2):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020098

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarile, Maria Cristina. 2021. "Piety, Power, or Presence? Strategies of Monumental Visualization of Patronage in Late Antique Ravenna" Religions 12, no. 2: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020098

APA StyleCarile, M. C. (2021). Piety, Power, or Presence? Strategies of Monumental Visualization of Patronage in Late Antique Ravenna. Religions, 12(2), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020098