Abstract

This paper discusses the symbolic capital found within Islamic documents that were circulated in the UK during the COVID-19 outbreak. Specifically, the work explores “fatwas” and “other” similar documents as well as “guidance” documents (referred to as FOGs) that were disseminated in March–April 2020 on the internet and social media platforms for British Muslim consumption. We confine our materials to FOGs produced only in English. Our study takes its cue from the notion that the existence of a variety of documents created a sense of foggy ambiguity for British Muslims in matters of religious practice. From a linguistic angle, the study seeks to identify (a) the underlying reasons behind the titling of the documents; and (b) the construction of discourses in the documents. Our corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis (CA-CDA) found noticeable patterns that hold symbolic capital in the fatwa register. We also found that producers of “other” documents imitate the fatwa register in an attempt to strengthen the symbolic capital of their documents. Accordingly, fatwas act as the most authoritative documents in religious matters and are written by senior religious representatives of the Muslim community, whereas guidance documents were found to be most authoritative in health matters. The findings raise questions regarding the manner in which religious instruction may be disseminated in emergency situations. Based on this study, a call for the standardisation and unification of these diverse and sometimes contradicting religious publications may be worth considering.

Keywords:

British; corpus analysis; COVID-19; critical discourse analysis; fatwa; mufti; symbolic capital 1. Introduction

Controversy was sparked among the UK Muslim community on Friday 20 March, when hundreds of mosques across London, Birmingham, Leicester, parts of Lancashire, and other areas in the UK continued to accommodate Friday prayers (5Pillars 2020). Prayers continued for Muslims who did not show symptoms of COVID-19. The ulama’ “Muslim scholars” from Northwest England, at the time of issuing the fatwa on 17 March, strongly believed that the benefits of continuing the Friday prayers outweighed the risks of spreading COVID-19 (Shabbir 2020a). The debate continued as Muslim scholars in the UK argued that unless the government imposed a lockdown and a ban on social activity, continuing prayers in mosques was not a major concern. On 25 March, after having spent 10 days on a ventilator, an elderly Muslim from Walsall, Birmingham, died of COVID-19. A family friend of the deceased said to the Press: “It is imperative that we learn from this tragic loss and comply with Government guidelines to save lives” (Thandi 2020).

The conflicting messages in the UK during this crisis caught our interest, as they caused confusion among British Muslims. Ideally, what was required was a single fatwa that would deliver a clear message regarding the way in which Muslims should respond to the pandemic. The reality, on the contrary, was a myriad of documents being circulated via social media containing various titles including fatwa, guidance and other miscellaneous words.

In this article we studied 76 documents that offered religious advice on COVID-19 related matters. This was the number of documents available to us at the time of the research. These documents consisted of 14 fatwas, 6 guidance documents, and 55 documents with different titles. In order to understand the power dynamics at play between these documents, we categorised them based on their titles into fatwas, others and guidance (FOGs). Our findings reveal that fatwas and guidance documents are diametric opposites in respect to style and purpose. Documents in the other corpus combine features of fatwas and guidance and act as a bridge between the two. Furthermore, documents titled other appear to serve as fatwas informed by guidance.

In novel cases, presuming that Muslims are most likely to face doubt in matters of religion, ethics or law, they may consult an Islamic legal expert for a non-binding legal opinion on the matter, known as a fatwa. The one who seeks the fatwa is called a mustafti, and the specialist who offers the fatwa is the mufti (Skovgaard-Petersen 1997). As such, a fatwa is dialectical between the mufti and the mustafti. The mustafti may seek a fatwa personally or on behalf of a wider group. Likewise, the mufti may respond personally or may respond on behalf of a panel of muftis. Az-Zarkashi defines a mufti as “a person who has good knowledge of all Shari’a law and also practices it” (Sarwat 2014). Questions put forward to a mufti may relate to various contexts ranging from psychological issues to global problems. In this regard, a mufti is required to be up to date with current issues and developments and have a thorough understanding of Islamic jurisprudence (Wahid 2020). Moreover, the mufti is expected to fully understand the circumstances in which the mustafti sought the fatwa to ensure that it addressed the specific problem in context.

A fatwa, therefore, is a hegemonic interaction. The interaction is based on a hierarchy in which the symbolic capital lies in textual authority of the mufti, which is offered to the mustafti as religious advice (Awass 2014). Bourdieu (1991) proposed the idea of symbolic capital, which refers to a kind of capital that is not material wealth, but which can be used to advance one’s position and obtain power in social and cultural contexts. Ottenheimer explains that communicative competence is a form of symbolic capital that involves “every aspect of language, from pronunciation (accent) and word choice and grammar to styles of speaking (or signing)… spelling and writing style” (Ottenheimer 2008, p. 120). In Islamic discourse, the fatwas are considered to be powerful writings as they can influence the way society behaves.

However, in order to write a powerful fatwa, it must hold symbolic capital. In a corpus-based critical discourse analysis by Brookes and McEnery, the authors found that violent jihadist texts acquire symbolic capital through an accumulation of patterns of textual cohesion and rhetorical strategies (Brookes and McEnery 2020). This symbolic capital makes the reader want to pay attention to the writer and allows the author(s) of a fatwa the right to be heard. The communicative competence of a fatwa may include extrapolation of rulings based on the Qur’an and the sayings of Muhammad. Quoting these two sources could increase symbolic capital. Additional capital could be gained if they were quoted in Arabic. Moreover, mentioning the various opinions of renowned jurists from the various schools of thought in Islamic jurisprudence would also contribute to an increase in capital. A fatwa may also be endorsed and signed by the producer, who may refer to himself as mufti. These characteristics of the fatwa register may have high impact due to the symbolic capital they possess.

In the UK, muftis are required so that fatwas can be offered to British Muslims who have questions related to the religious issues they face. A major function that muftis serve is to uphold the maqasid al-shari’a, meaning “the objectives of the Shari’a”, which includes preservation of religious practices, life, intellect, wealth, dignity, and lineage. Questions related to these objectives would be best answered by muftis who have a deep understanding of the society and culture they live in. Likewise, the mufti should be knowledgeable with regard to government systems, as well as British culture. For this purpose, perhaps an ideal mufti would be one who is British-born and raised.

Fatwas have warranted the interest of many researchers in recent times (Caeiro 2017; Bunt 2003; Feldman 2005). Various issues have been raised with regard to the fatwa register in the UK in relation to bioethical matters, for instance, the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act 2015 (Ali 2019) and Max and Keira’s organ transplantation law 2020 (Ali and Maravia 2020). Likewise, during the coronavirus pandemic, the priority of Muslim religious scholars was to advise British Muslims on how to conduct themselves to curb the spread of COVID-19 (BBSI 2020).

In the UK, mosque imams and managers appear to have sought religious guidance from muftis with regard to continuing congregational prayers in mosques during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Muslims also sought guidance on other matters. These include the following: the correct way to deliver the Friday sermon; how to observe the fast during the imminent month of Ramadan (third week of April); and the proper manner in which the end-of-life rites of passage should be carried out for deceased Muslims who contracted COVID-19. Individual members of the Muslim community resorted to muftis for religious solutions to their dilemmas regarding a number of issues. These include whether to attend mosques or not, the methods of ritually washing and shrouding a deceased family member, and whether to observe the Friday prayer at home or the alternative early afternoon prayer (Zuhr). Additionally, targeted questions came from Muslim healthcare professionals working on the frontline. These questions included exemption from fasting for healthcare professionals who were required to work long shifts, as well as the question of resource allocation and triage.1

With the emergence of digital tools, fatwas are readily accessible online and on social networks in English. However, apart from documents that are explicitly titled fatwa, there exist a plethora of documents with different titles, which appear to function as fatwas. Such documents may display the style or format of a fatwa to strengthen their symbolic capital and may even refute an already existing fatwa. For instance, in relation to organ transplantation, Butt (2019) titled his work “An Opinion”, yet it was received by the media and other Muslim scholars as a fatwa (NHSBT 2019). While a text may be seen simply as a coherent and cohesive unit with its lexis and grammar, texts do not function alone (Koller 2012). Texts refer to other texts, creating intertextuality, refuting or supporting each other and giving the floor to other voices. Shiffrin argues that several functionally organised language units can comprise a discourse (Schiffrin 1994).

Based on Shiffrin’s definition, we may reasonably accept that the various texts related to the discourse of Islamic practices and COVID-19 form one broad discourse. The main actors in this discourse involve muftis, Muslim scholars, and healthcare professionals. The COVID-19 outbreak may be seen as an issue that required utmost clarity considering that an ill-informed fatwa could potentially have caused a trajectory of deaths in the UK. However, granted that the titles of Islamic advice documents differ from a fatwa, this variation raises questions about power and authority. Does a document not titled a fatwa still function as a fatwa? Do Muslims view a guidance document as having the same religious authority as a fatwa? And what about documents whose titles consist of words other than guidance or fatwa? Which of these documents are British Muslims to follow? Such questions lead to uncovering the issue of power relations among British Muslims.

Power affects the construction of discourses because discourse, compared to a text, encompasses the entities beyond the textual level. Discourse comprises what is between the text, behind the text and the underlying goals of producing it. Karlberg claims that power does not necessarily mean conflict and oppression, and Western liberal discourses express power alternatively, in softer ways (Karlberg 2005). Thus, the intention of the documents is not just sharing advice, but also exhibiting power in society. Moreover, power is relative, and a single discourse producer and social actor could display different levels of power in various discourses (Fairclough 1989). In our study, we demonstrate the way in which fatwas, guidance documents and other documents (FOGs) related to Islam and COVID-19 appear to have operated in the UK.

Central to our study is the focus on authoritative voices involved in the document-making process. This focus requires qualitative research of the texts produced by Muslim scholars, which requires systematic linguistic analysis. To the best of our knowledge, such a study has not yet been carried out on fatwas related to COVID-19.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

Our study investigates the writing style of Islamic documents produced and circulated in English for British Muslim consumption. They include religious advice sought on the topic of mosque closures, funerary rites, fasting during Ramadan, and suspending Friday and daily prayers to help curb the spread of COVID-19. The individual or group who was involved in the document production process is referred to in this paper as the text producer(s). These documents were available online, on British mosque websites, or were published on the Facebook page or group page of the text producer(s). These documents were digitally circulated via email groups via reputable Muslim organisations, including the Muslim Council of Britain and the British Board of Scholars and Imams.

The timeframe for collecting these documents started in early March 2020 when the spread of the coronavirus was characterized as a pandemic. We determined 25 April as the cut-off date for collecting documents, as this was the date when Ramadan was established for all Muslims in the UK. Ramadan was used as the cut-off point because any document that contained instructions for the Muslim community would have ideally needed to be issued prior to Ramadan.

We collected a total of 76 documents and categorised them as either fatwas, guidance, or other documents (cf. Table 1). We categorised the documents based on the lexes the text producer of these documents used in the titles or the leading paragraphs. We found 14 documents clearly titled fatwa. The second category we created consisted of six texts titled guidance. Other was found to be the largest category, containing 56 texts, with a range of titles that neither contained the word fatwa, its variant spelling fatawa, nor guidance. The three categories are henceforth also referred to by their initials (F, O and G), and collectively as FOGs. Thus far, we have provided a basic overview of the FOG corpus. In Section 2.6, we explain, in further detail, the manner in which the FOG corpus was designed.

Table 1.

Summary of features for the fatwa, guidance documents and other documents (FOG) corpus.

A cursory glance of the titles of the documents does not show any pattern or indicate any reason as to why the titles vary. Our main question was as follows: Are the titles chosen arbitrarily or subjectively? To seek an explanation, we conducted textual analysis focusing on linguistic evidence to explain if there are any direct correlations between the language of the texts and their titles. We speculated that text producers rely on the language and contents of the text when formulating a title. As such, the titling of a document, amongst other factors, may depend on the audience, the mode of its delivery, and the location where the document was made available. Moreover, texts may contain the same lexical choices and content, yet still differ by title. Therefore, we decided to investigate what lies beyond the text by process of discourse analysis.

In a broader sense, discourse is the way in which the world is represented by the text and the rules that govern the text (Fairclough 2003). We looked beyond the text and considered the non-linguistic factors that shape and frame it. For this purpose, the object of discourse analysis includes the situation in which the text was produced, the recipients of the text, its purposes and the institutions involved.

2.2. Rationale for Applying CDA to Analysing FOGs

The wider non-linguistic factors alone are unable to provide a clear explanation for the way in which texts are titled. If we assume that, during lockdown, Muslim scholars in the UK, through official channels, prohibited visiting mosques, then the expectation from British Muslims would be to refrain from visiting mosques. As such, if, hypothetically (during the lockdown), a document titled Health hacks for mosques during lockdown was made available on a casual social media site for practicing Muslims, this may be viewed as challenging the status quo. Furthermore, the document may even be viewed as a political move against Muslim scholars, who hold an authoritative voice. The presence of different voices in society invites an understanding of power, which is not always simple to detect in discourse analysis. For this purpose, critical discourse analysis (CDA) is an effective approach that could unmask the phenomenon of power in discourse. Because our data are rooted in social and political issues, as well as bound to religion and culture, we took the CDA approach to discourse analysis to answer two main questions: (i) Are the titles in our FOG corpus arbitrary? (ii) Do the documents echo a social hierarchy among British Muslims?

CDA allows analysts to detect inequalities and injustice (Van Leeuwen 2006; Van Dijk 1993), discrimination, exclusion, power and the legitimation of power (Reisigl and Wodak 2016), as well as other social wrongs, using linguistic evidence. CDA employs such evidence to elucidate changes in politics, economy, and culture (Wodak 2001). By changes, we normally mean righting social wrongs or challenging negative tendencies in a society. Moreover, CDA is able to provide recommendations for solving social issues (Fairclough 2010, p. 235). Fairclough recommends focusing on one moment of a political event that is embedded into the broader context of such moments (Fairclough 2013, p. 179). By applying CDA, we intended to gain insight into the broader moments experienced by British Muslim society during our study period.

2.3. Fairclough’s Three-Dimensional Model

Among the plethora of approaches to CDA, we applied Fairclough’s three-dimensional framework (Fairclough 1995). This approach covers the intertextual, the social and political processes at work. We studied the textual, discursive, and social aspects. This approach helped us to uncover the links between titling and the social structure of Muslim society and to seek an answer regarding whether titling is arbitrary or subjective.

At a textual level, we analysed the data using corpus linguistic analyses, which identified particular words in the FOGs to assist us in the discourse analysis (see Section 2.7). We identified the most frequently recurring words and lexical bundles and then compared these words to see if there were any significant differences both in their frequency and use. As this is a pilot study to primarily identify patterns in titling, we decided to focus on basic lexes and syntax. On a lexical level, we analysed Arabic loanwords that are frequent in Islamic jurisprudence. We also looked for lexes, key phrases, modal verbs, and pronouns, and attempted to note frequent collocations and parenthetical phrases in the FOGs. Differences in language use indicated differences in the points of views of the text producers, such as the foci of the producers.

From a discourse perspective, we looked at the FOGs as part of the large and complex discourse on Islam and the coronavirus pandemic. This involved examining the wider social and political issues, cultural processes, and dominating ideologies in the British Muslim community at the time of the lockdown. From a social aspect, we examined social actor representation. In what follows, we explain this notion of social actors and their importance in the analysis of FOGs.

2.4. Social Actor Representation

Social actor representation helps to identify the agents of the discourse (Van Leeuwen 1996). Primarily, in CDA, social actors are people who are involved in discourse, and either perform actions themselves or have actions done to them within this discourse (Darics and Koller 2019). In other words, social actors are doers or passive objects, and their nominations are encoded into the text by linguistic means. A grammatical linguistic representation of social actors does not necessarily indicate a person who does an action, i.e., this does not equate to sociological agency (Van Leeuwen 2008, p. 221). In some cases, social actors are impersonalised, i.e., they are presented as inanimate objects (Van Leeuwen 2008, p. 59), as in the following statement:

The fatwa suggests that we are to be cautious about visiting iftars.

Fatwa is the social actor, even though a fatwa itself cannot suggest anything, while the text producers can.

Productive social actor analysis can be conducted based on an examination of pronouns in the discourse (Darics and Koller 2019). The producer of a text may choose to use the pronouns I or we to construct in-group identities and they for out-group identities. These references may explain the construction of identities in the discourse, their interrelations, and attitudes. By including the audience and the text producers themselves within we, the text producers are able to emphasise their equality with their audience. By contrast, the pronoun they creates “otherness”. As the British Muslim community does not have any official religious institution, it is possible to infer the social strata of the authorities via an exploration of their discourses. We therefore investigated pronouns in the FOG documents to help us decipher the power relations in the British Muslim social structure. The following section explains these power relations and the way in which they may be evident from the titles of the FOG documents.

2.5. Power Relations

Power is central to CDA. Fairclough insists that power is enacted in the discourse, and the dominance of separate participants is normally visible from their interaction (Fairclough 1989). Power is a relative concept, because one discourse participant may have differing levels of power in different discourses and in relation to other participants. Dominance in power relations is achieved by strategies of struggle (Foucault 1982), and we seek to detect these strategies by linguistic means in our data.

In our study of the FOGs, we pay attention to power distribution among the discourse participants. We ask the following questions: In what way do text producers in the discourse position themselves? Who holds power and who is powerless? In what way is this dominance articulated linguistically? Fairclough argues that power distribution is understood, accepted, and followed by discourse participants when the discourse is institutionalised (Fairclough 1989)—for instance, the power of a doctor over a patient or that of the police over a witness. However, what happens if the institution itself is not formally established, as in the case of the British Muslim society? Despite the many jurists in the community, there is no legal recognition of them as having authority. By analysing the FOGs, power distribution can be unmasked in several ways. One way is by examining the modal verbs discourse participants use in relation to their interlocutors. For instance, do the text producers give commands, prohibit, or simply offer suggestions? The way in which text producers refer to their interlocutors and possibly other participants of the discourse could also reveal the distribution of power.

Given what has been discussed so far, we learn that, in fatwas, there is an interaction between the mustafti and the producer of the fatwa. The mustafti usually asks one or a number of questions, and the use of modal verbs, as in can we, for instance, indicates whether the mustafti is asking for permission or advice. The modal verbs in these interactions indicate the acceptance by the mustafti of the text producer’s unconditional expertise and knowledge in the field. This can be seen in the FOG corpus, for example, in the following questions:

Can we visit madrassas?

Are we allowed to attend Friday prayers?

We observe that a mustafti takes a less authoritative position compared to the text producers. We therefore examined the way in which modal verbs were used in the FOGs to uncover power relations.

As our study looks at 76 documents of varying lengths, there was a high probability that instances of a particular linguistic feature would be overlooked. To overcome this problem, CDA was combined with corpus linguistics to help make the data more accessible and statistically based. The field of corpus linguistics is defined by Baker and McEnery as “… a powerful methodology—a way of using computers to assist the analysis of language so that regularities among many millions of words can be quickly and accurately identified” (McEnery and Baker 2015, p. 1). A “corpus”, as defined by McEnery et al., is: “a collection of (1) machine-readable (2) authentic texts … (3) sampled to be (4) representative of a particular language or language variety” (McEnery et al. 2006, p. 5). Corpus linguistics has grown as a field and has assisted CDA in numerous studies. One remarkable example of corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis (CA-CDA) was by Baker et al. (2013), who used corpus methods to analyse a 140-million-word corpus of British newspaper articles to uncover Islamophobic attitudes in the British press. In the following section, we describe the corpus methods we used.

2.6. The FOG Corpus

Our FOG corpus is a specialised corpus with 76 texts, comprising a total of 109,711 tokens—meaning the total number of words. Despite being small in size relative to other major corpora used in other corpus studies, the size of the FOG corpus was purpose-built to answer our research questions.2 The corpus contained three sub-corpora; the F-corpus, which contained documents titled fatwas, the O-corpus, which contained documents that were titled neither fatwa nor guidance, and the G-corpus, which contained documents titled guidance. The key features of the FOG corpus can be revisited by referring to Table 1.

2.7. Corpus Methods and Tools

Corpus linguistics (CL) facilitates quantitative and qualitative analyses (Biber et al. 1998). The AntConc software offers key tools to assist our analysis, such as the frequency of words, word lists, lexical bundles, collocations, concordance plots, and concordances, and these help us to detect linguistic patterns in the FOG corpus (Anthony 2018).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Titles and Repeating Lexical Features

The most important finding was, primarily, the variation of titles. Table 1 illustrates that 56 of the 76 FOG documents were titled neither fatwa nor guidance, but with miscellaneous titles, including analysis, clarification, confirmation, guidelines, method, pathway, permissibility, plan of action, points, recommendation, response, ruling, and statement. By comparison, only 14 documents were titled fatwa and even fewer (six) documents were titled guidance. At the micro-level of our CDA analysis, we examined linguistic patterns and the textual characteristics of the discourse. For this purpose, we used AntConc software to examine Arabic loanwords, key phrases, lexes, modal verbs, and pronouns.

3.2. Main Content

The main difference in language use between the FOGs is noticeable in the fatwa and guidance documents. Both of these text types present the same themes, including safety rules, Islamic practices, and lockdown instructions. Both texts are aimed at informing British Muslims about the way in which rituals should be observed during the lockdown period.

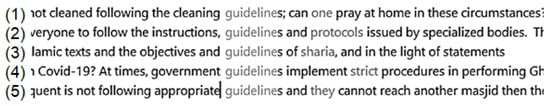

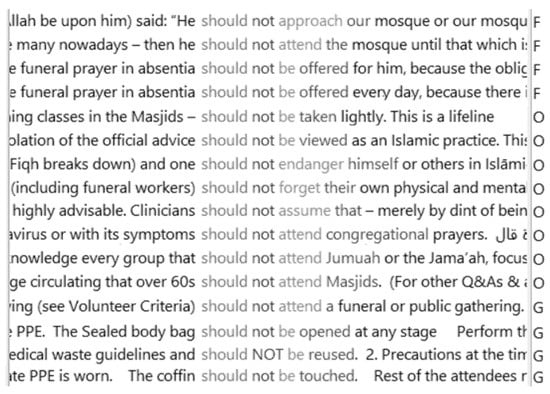

Our corpus search did not detect any instances of the word fatwa or its variant spellings in any of the six guidance documents. By comparison, the noun guidelines occurred five times in the F-corpus. Figure 1 reveals the way in which a reference to guidelines is made at times by the mufti and at other times by the mustafti. In line (1), a mustafti asks whether, if a mosque does not follow cleaning guidelines, in that case, praying at home would be allowed. Line (5) is from the same document and, on this occasion, the mufti explains that should a mosque fail to meet guideline requirements then praying at home is allowed. Line (2) talks about the Council of Senior Scholars advising Muslims to follow the instructions, guidelines and protocols issued by specialised bodies. we can assume this refers to government health guidelines. Line (3) is from the statement of a mufti, in which he mentions the guidelines of the Shariah. This use of the word guidelines does not refer to any government guidelines; rather, they refer to the ones that muftis follow in reaching Islamic verdicts. Line (4) is, again, from a mustafti, who asks about the funerary rites during lockdown, in light of the government guidelines in relation to washing the deceased.

Figure 1.

Instances of guidelines in the F-corpus.

We can infer from the above instances that a mustafti may be concerned by the guidance documents and seeks the approval and clarification of a mufti before proceeding with religious practices. On the face of this, we inferred that guidance documents have a wider audience than fatwas and may include healthcare workers who serve Muslims. Whereas the audience of a fatwa is most likely to be the practising Muslim population, guidance documents may be of interest for even a non-Muslim audience. Assuming this to be true, it seems that a fatwa for a practicing Muslim holds more authority than guidance documents. We also found that other documents also have a position of authority alongside fatwas and guidance documents, as shall be discussed below in Section 3.10.

Practising Muslims are likely to be familiar with juristic terms. Therefore, juristic terms are widely used across fatwas without explanation, perhaps based on the assumption that the audience has shared background knowledge of these concepts. For example, we searched for Arabic loanwords and found that the term wajib, meaning obligatory, occurred 16 times in the F-corpus and O-corpus. The term is generally used to indicate the obligation of an act, behaviour, or custom. This finding entails a question about the purpose of the documents and their targeted readers. The use of juristic terms presupposes that the reader understands them and, moreover, that they are of concern to the reader. Thus, the target audience of fatwas and other documents appear to be practising Muslims. During lockdown, a number of practising Muslims wished to know what acts were wajib. For this purpose, the function of a fatwa would be to either obligate an act or to declare it non-obligatory.

Ghusl, meaning bathing the deceased, is another Arabic word and it occurred 164 times in 20 documents in all three corpora. In the F-corpus, ghusl was discussed in terms of permissibility, meaning that the fatwas discussed whether ghusl is generally allowed or not during the COVID-19 pandemic. The O-corpus and the G-corpus, on the other hand, discussed the safety of giving the ghusl in terms of health. For example, a guidance document explains the following:

- (1)

- If public health authority [sic] has given permission to carry out the ghusl then these steps will be followed, [sic] if not go to step…

The priority in this document was not to highlight the method for performing ghusl during the pandemic, but the importance of safety first. Similar instances in the G-corpus reveal that the primary goal of a guidance document is to consider health and safety more than to preserve the status quo of the way in which traditions are maintained.

3.3. Authority of the Prophet

We also found a high frequency of occurrences of Prophet and Messenger in the F- and O-corpora, with the G corpus also using these words, as illustrated in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Frequency of Prophet and Messenger in the FOG corpus, along with range.

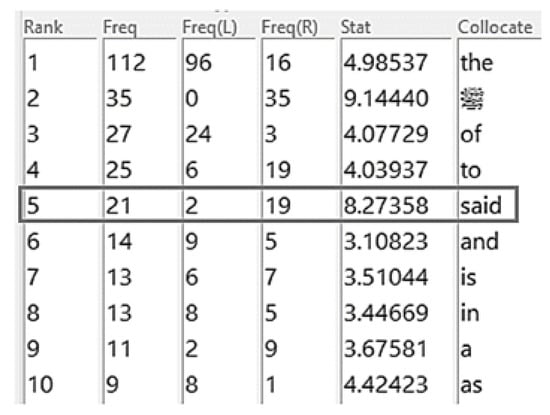

Table 2 shows that prophet occurred in eight fatwas, with a total of 36 occurrences. Messenger occurred in 10 documents, with a total of 80 occurrences. Based on the fact that these words occurred at a high frequency, we decided to examine them. A thorough examination of concordance lines for prophet and messenger in the F-corpus and O-corpus revealed that the words are used to quote Muhammad, who is referred to by English-speaking Muslims as the Prophet and Messenger of Allah. Moreover, Figure 2 reveals that the top 10 collocates for the noun Prophet in the O-corpus include words from the honorary phrase Peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, written either in English or as an Arabic symbol. These collocates were determined using a search span of 5:5, meaning the words that co-occurred five places to the left and right of prophet and messenger. One collocate that stands out is the transitive verb said, which requires an object. The object in this instance would be a quote spoken by Muhammad; moreover, the quote can either be direct or indirect speech.

Figure 2.

Top 10 collocations of Prophet.

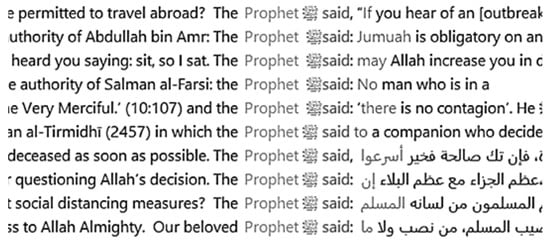

Quotes by the Prophet are better known as the “hadith”. References to the hadith, as illustrated in Figure 3, strengthen symbolic capital and the reliability of the instructions outlined by the producers of texts. This application of symbolic capital serves to convince the audience that the modifications in the practices appear not to contradict Islamic traditions. We can infer that the audience of other documents, like the audience of fatwas, are practising Muslims, who treat Muhammad honourably as a Prophet and look to him as an unconditional authority in their faith.

Figure 3.

The hadith of the Prophet of Islam.

3.4. Accountability

Our corpus search for lexical bundles found linguistic variations within the FOGs. In Table 3, we list three frequently occurring lexical bundles.

Table 3.

Frequency of frequent lexical bundles in the FOG corpus along with range.

These lexical bundles caught our attention due to their high frequency of occurrence and evoked further scrutiny in order to explain the reason why they prevailed in the F-corpus and O-corpus. An occurring feature located towards the end of fatwas and other documents is the lexical bundle Allah knows best, or its variant Allah Ta’ala knows best, which is used by producers to convey a commitment to conventional values—the idea, in Islam, that only God is empowered to know and state what the actual law is. The bundle is conventionally used when conceding that there is no fixed answer and, therefore, functions to help avoid overconfidence in one’s opinion and to allow room for other scholarly voices. Meanwhile, guidance documents are more precise, explicit, and provide fixed answers to questions and concerns; ergo, the lexical bundle Allah knows best is not found.

3.5. Endorsements

Approved by is another lexical bundle that is used repeatedly in fatwas to refer to social actors that endorsed these fatwas. The construction occurs 33 times in 32 texts. By comparison, no instance of the phrase was found in the guidance documents. All 33 instances were followed by a proper noun, along with the honorific title of mufti. This endorsement by a renowned mufti of a fatwa by a producer of lesser authority may also suggest why an endorsed other document gains a fatwa-like status. We discuss this in further detail in Section 3.10.

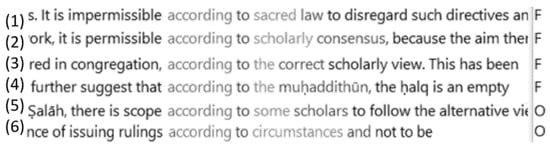

By comparison, another lexical bundle, according to, is found in all three text types. According to is commonly used to refer to an opinion that may or may not be the text producer’s own opinion. If the opinion is one that coincides with the text producer’s opinion, then such a technique—of quoting a more authoritative voice—can be a powerful rhetorical tool. This lexical bundle occurs in all three text types; however, on examining the concordance lines in the F-corpus and G-corpus, we found that each sub-corpus has a tendency to quote a different type of authority. Figure 4 reveals that fatwas contained instances of according to—in order to reiterate accepted values rooted in scripture, as well as scholarly views; references to sacred law (1); scholarly consensus (2); correct scholarly views (3); and the muḥaddithūn (4) help to strengthen the status quo in terms of the way in which a tradition is upheld.

Figure 4.

Instances of according to in the FOG-corpus.

The use of according to in the O-corpus shows that the references are more contextualised and specific. For example, by referring to some scholars (5), rather than a consensus, and mentioning circumstances (6), rather than the norm, the text producers are able to discuss issues in a manner that differs from the status quo. In other words, these qualifications indicate that producers of other documents are, as a result of a change in circumstances, questioning the status quo.

3.6. Modal Verbs

In linguistics, functional words are important for grammatical relations in sentences, even though they might not add extra lexical meaning. They include prepositions, determiners, conjunctions, pronouns, auxiliary verbs and modal verbs. We examine modal verbs, and then pronouns, since they stand out in the frequency analysis. Our findings regarding modal verbs, which are summarised in Table 4, illustrate that must, should, and do not occurred more frequently than other modal verbs in the corpus.

Table 4.

Frequency of modal verbs in the FOG corpus, along with range.

The content of the FOG corpus reveals that all three documents have a higher frequency of must, should, and do not; however, modal verbs are used in different contexts in all three corpora. Modal verbs were found to occur with instructions related to religious practices in the F-corpus, instructions related to health and safety in the G-corpus, and religious practices as well as health and safety in the O-corpus. This feature further supports our assumption that the purpose of the guidance documents is to prioritise health and safety above maintaining traditions. In fatwas, the modal verbs used by the text producers serve to guide readers on how to adapt their religious practices under unusual circumstances. To elaborate, the fatwas explain that, by regulating and modifying Islamic traditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, these modifications could curb the spread of the virus. In any respect, the fatwa also attempts to assure Muslims that the modified practices will also help them to maintain a balance between health and safety and commitment to their faith.

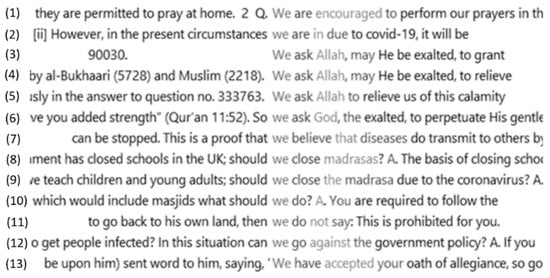

Figure 5 shows that, in the guidance documents, the advice was to refrain from any activity that would cause harm to one’s health. On the other hand, the advice in fatwas is related to rituals. For example, the guidance text discourages opening a sealed bag in a mortuary or touching a coffin and encourages the reader to be mindful of health matters. On the other hand, the fatwas discourage the observation of prayers at a mosque and encourages the observation of funeral prayers in one’s own home. In this section, we do not discuss the functions of must and do not. Instead, we discuss these modal verbs in Section 3.10, where we also discuss power relations.

Figure 5.

Instances of should not in the FOG corpus.

3.7. Pronouns

We examined the FOG corpus to explore the use of pronouns in order to establish which social actors are mentioned. Table 5 shows the number of times each pronoun occurred, with attention paid to (a) actual instances of each pronoun in each corpus and (b) a calculation of the number of times each pronoun would occur if each corpus consisted of 10,000 words. Because the lengths of each of the corpora vary, we used this calculation to normalise the output of the data.

Table 5.

Occurrences of pronouns in the FOG corpus.

An interesting pattern we found was the frequent use of the third-person singular pronoun he, which occurred 143 times in the F-corpus, shown in bold in Table 5 above. Upon closer inspection, we found 29 instances of these occurrences, capitalised as He (to mean God). We also found eight instances referring to Prophet Muhammad, and another 122 instances referring to various individuals, from traditional Muslim scholars to hypothetical individuals. The O-corpus had a similar resemblance. However, the G-corpus did not display the same features.

Frequent references to God, the Prophet Muhammad, and Muslim scholars again demonstrate the way in which other documents are fatwa-like. By contrast, guidance texts differ from fatwas in the sources that are referenced. Our examination of the pronouns led us to assume that fatwas emphasised the religious and traditional values and attitudes of their producers regarding issues related to COVID-19. A focus on emphasising health-related rules and regulations or the views of medical experts was, by comparison, found to a lesser degree. An elaborate discussion of we can be found in Section 3.9, where we also discuss power relations.

3.8. Diametric Content

We have thus far established that the F-corpus and the O-corpus have similar features and, likewise, the O-corpus and the G-corpus share features. Based on this finding, we found fatwas and guidance documents to be diametric in their style and purpose. On the one hand, fatwas provide explanations and rationale for changes in tradition and are oriented towards the practicing Muslim community as the intended audience. In this sense, fatwas in the F-corpus were peculiar, with their own lexical choices and lexical bundles.

On the other hand, guidance documents were found to contain concise instructions on appropriate action during the COVID-19 lockdown. These instructions were without reference to any fatwa or mufti, a theological explanation or any lyrical digression. Furthermore, guidance documents showed the least mention of religious expressions, yet showed frequent mention of matters related to health and safety; Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), was mentioned 53 times in three guidance documents. This finding leads us to assume that the guidance documents were intended not only for the British Muslim public, but also for the consumption of the wider public, including healthcare professionals. The producers’ intentions also play an important part in titling the papers, whether they aim to focus on safety and provide instructions or discuss the possibilities of practising religious traditions under lockdown restrictions.

The combination of CDA with the assistance of corpus methods allowed us to uncover important patterns in relation to FOGs. Consequently, we can assume that fatwas and guidance are diametric. The two text types have their subject matter in common, which, in our study, was Islamic practices that needed to be explained during the COVID-19 lockdown. Other characteristics of the texts, including word choice, goals, and the targeted audience, also differed. This elementary study of our FOG corpus gave us a hint with regard to the reason why the documents may be titled differently. This reason is perhaps that, besides the subject area, their aims differ. However, the question of the process behind the titling of other documents still remains unanswered. To address this part of the study, we analysed the texts to observe the ways in which their discourses are related. We conducted this stage of the analysis using corpus tools.

3.9. Power Relations through Social Actors and Titling

Our findings revealed that the lexical bundle approved by occurred six times in five fatwas. Upon examining the concordance lines, we found that all instances were endorsements of the fatwa by another senior scholar. We learnt from these instances that fatwas were voiced by a council of scholars. The 14 fatwas in the F-corpus were the products of four main producers. Two of the producers were from outside the UK: (1) mufti Ebrahim Desai, a respectable mufti based in South Africa and the main producer of the fatwa site Askimam.com; (2) the Saudi-based Syrian scholar Sheikh Salih al-Munajjid, general supervisor of Islamqa.info. (3) One fatwa in the F-corpus was produced by mufti Qazi Amjad Kakakhayl, who represents the Sharia Council of the UK. (4) The fourth producer, Yusuf Shabbir, who, despite the fact that he does not refer to himself officially as a mufti, produced a text entitled fatwa. Furthermore, all of Shabbir’s texts are endorsed by his father, Shabbir Ahmad, who also carries the honorific title of mufti.

An assumption that can be made from this information is that, in the British Muslim context, a document cannot simply be titled fatwa arbitrarily. Rather, such titling appears to be a privilege reserved for senior scholars. This privilege may be extended to non-senior scholars, as long as a senior scholar endorses their text. The endorsement then empowers the text to have a fatwa-like status.

Such privileges trigger important questions regarding the power relations in discourse. Fairclough states that power relations in discourse influence language use, which reveals the empowered and powerless participants of the discourse (Fairclough 1989). With this notion in mind, in our study, the empowered group consists of senior religious authorities that entitle documents fatwas. Publishing a document entitled fatwa signals power. We learn, therefore, that titling a document a fatwa depends not only on the linguistic peculiarities or the audience, but also the profile of the producer and their competence and acceptance for them to be allowed to entitle their documents fatwas.

To gain a better understanding of the in-group and out-group within the F-corpus, we investigated the first-person plural pronoun we. Figure 6 provides a sample of the way in which we is used in the F-corpus.

Figure 6.

We in the F-corpus.

We found 39 instances of we in 11 fatwas. A mustafti may use we to ask a question to a mufti on behalf of others that share the same concerns:

Concordance line 8: Should we close madrasas?

Concordance line 12: Can we go against the government policy?

In the response sections, the pronoun we is used occasionally to refer to a panel of scholars in order to give the response more authority:

- (2)

- In reaching this conclusion, we have also consulted with Mufti Ahmad Khanpuri (b. 1365/1946), Mufti Muhammad Tahir (Saharanpur), and Mufti Muhammad Salman Mansurpuri (b. 1386/1967) who have confirmed that there is no pouring water, taya-mmum, or masaḥ over the body bag (Shabbir 2020b).

We, in the above example, refers to the body of scholars that was involved in the fatwa process. Another example reads:

- (3)

- We highly advise that the following protocols be adhered to for ghusl, janazah, and burial arrangements (CCI 2020).

The producer emphasises that the body of scholars is empowered to give strong recommendations in these issues, and we fortifies this claim.

In some cases, fatwa producers may even use the singular pronoun I to act as an individual social actor while giving advice:

- (4)

- as I have said previously each madrasa is responsible for the safety of its staff and students (Kakakhayl 2020).

On occasions when muftis express their opinions using the first-person singular I, they appear to do so politely and without using strong statements, for example:

- (5)

- I do not believe the blanket statement is helpful (Kakakhayl 2020).

The social actor, the fatwa producer, articulates his belief through the phrase I do not believe instead of explicitly stating that a blanket statement is unhelpful. This toning down of the statement may be a case of politeness and indirectness and to sound less confrontational rather than imply uncertainty (Coates 1987).

By contrast, one guidance document showed clear distancing between the producers and the audience through the pronoun we. The text reads:

- (6)

- We want to ensure pilgrimages are safe and that they don’t lose money (CBHUK 2020).

Here, we excludes the pilgrim or the would-be pilgrim audience. Instead, we refers to the text producers who believe that they are responsible for the pilgrims’ safety and, therefore, have the right and expertise to provide advice and instruction. Another interesting use of we in the guidance document is found in the following statement:

- (7)

- we advise you to explore all options (CBHUK 2020).

The texts producers do not identify themselves as pilgrims. They also do not recognise pilgrims as an authority on health matters.

What can be said about the guidance documents is that its directness reveals the greater certainty of its authority compared to the authority found in fatwas. Fatwas, by comparison, appear to include more hedging, as evidenced by instances in the F-corpus, including:

- (8)

- All answers are time sensitive as it is a developing matter

- (9)

- Allah knows best (Kakakhayl 2020).

Furthermore, fatwa producers do acknowledge the authority of the government, as shown in the following statements:

- (10)

- According to the government’s latest guidelines, the PPE to be worn … (Shabbir 2020b).

- (11)

- You are required to follow the government’s directive (Kakakhayl 2020).

Moreover, our corpus search showed no reference to fatwas in guidance documents. This unidirectional feature of guidance texts may be an indication that the producers do not view fatwa producers as authorities in matters related to health and safety.

3.10. Situating the O-Corpus

Based on the foregoing discussion, we can assume that both fatwas and guidance documents reveal their intentions to maintain power in the discourse. However, between the two prototypical documents—fatwas and guidance —we observe a large number of documents titled with a plethora of different names, as mentioned in Section 3.1. How can these documents be situated in this multi-layered discourse on COVID-19 and Islam? Our CA-CDA leads us to find that other documents combine all features of both fatwas and guidance documents. A cursory biographical study of the text producers reveals the diverse community of producers to be Islamic scholars of different research interests, some whom have their own websites, YouTube channels, or blogs. The degree of their power may vary in certain micro societies, for instance, among bloggers. Nevertheless, their power cannot be compared with those demonstrated by fatwa and guidance producers because they do not have unconditional authority among the British Muslim population. We may position these text producers on a relatively equal level of authority in the religious hierarchy, meaning they have less power, and are positioned on a lower step than fatwa and guidance producers.

This lower position in the hierarchy of text producers, however, does not restrict them from challenging fatwas. To reveal what is said about fatwas in other documents, we closely examined the concordance lines where fatwas or their variants occurred in the other corpus.

Below is an example of such a disagreement:

- (12)

- Respectfully, I think there are holes in the Fatawa from a few scholars allowing people to follow Taraweeh behind a screen that most Fiqh councils have pointed out (Suleiman 2020).

The producer directly points to the flaws of the fatwa, whilst maintaining the mutual respect of the fatwa producers.

This feature confirms that the authority of fatwa producers is not something unquestionable. Officially, there is no grand mufti in the UK, and there is no centralised formal body that is in charge of issuing and adapting Islamic rulings. Nevertheless, informally, authorities exist, and their power is evident from their privilege in titling their documents as fatwas. While there are producers who readily challenge fatwas, in the O-corpus, such critics were not ambitious enough to title their critique a fatwa.

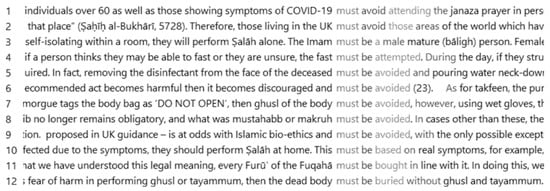

This power struggle can be also observed among less authoritative scholars in the O-corpus, wherein we found that the strong modal verb must occurred 115 times in 29 documents. A sample of strong prohibitions can be seen in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7.

Must in the O-corpus.

Similarly, in the O-corpus, we found 46 instances of do not in 26 texts that make strict and direct prohibitions, including:

- (13)

- but do not recite the Qur’an by holding it in your hands

- (14)

- while you are in it, do not leave that place…

By using strong modal verbs to obligate or prohibit the audience regarding religious matters, less authoritative scholars perhaps attempt to maintain their authority and demonstrate their expertise. However, as the fatwa title is avoided in these documents, this indicates a lower position among scholars. In any case, we cannot ignore the deliberate, specific titling of the papers by the producers. Thus, calling a paper a clarification might signal the author’s intention to discuss a particular fatwa and adapt it to the readers. However, the power hierarchy is also an eye-catching pattern in the diversity of the titles.

Secondly, intertextuality within the less empowered layer of discourse was higher than in the fatwa and guidance corpora. This intertextuality reveals important insights into the way in which other documents are received by their audience. A document that is not titled fatwa may still be received as a fatwa, as in the following example, where a mustafti wrote:

- (15)

- In relation to your Fatwa entitled No female to bathe female deceased and a previous one entitled Coronavirus deaths and ruling on Ghusl, we take note of the government’s most recent advice and the relaxation of the regulations for handling bodies infected with Coronavirus (Shabbir 2020c).

The mustafti refers to the documents of the interlocutor as fatwas, in spite of the fact that these documents were initially not titled fatwas. By referring to these documents as fatwas, the mustafti might be expressing his respect to the producer and showing his recognition of the latter’s authority in the discourse. The document producer, in turn, accepts the mustafti’s use of the term fatwa and appears to accept the compliment, even though the document was actually called an edict by the producer. The original document stated:

- (16)

- Please note this edict is based on the current situation in the UK as of 13 March 2020 (Shabbir 2020d).

Thirdly, our analysis on the discourse level of FOGs shows that documents are interrelated and intertextual. They refer to, refute and endorse one another and, at times, are found to criticise fatwas. Moreover, power and authority are acknowledged, to a degree, from the title choices. Our analysis of the 76 documents in the FOG corpus reveals a hierarchy of text producers among British Muslim scholars. In the following section, we explain the FOG analysis from a social perspective.

3.11. Bridging FOGs to the Wider Context

A critical analysis of FOGs on the social level outlines some complex issues and curious features of Muslim society in the UK. The fatwas in our collection refer to guidance documents, and quote government policy, whereas guidance documents, on the contrary, do not refer to fatwas. If we position the other documents between fatwas and guidance, we find that these other documents serve as fatwas informed by guidance documents. This function perhaps allows producers of other documents to refer to their own documents or to other documents as fatwas. To elaborate, a title containing the word permissibility was referred to as a fatwa by the producer of the same document in the same text. The text reads:

- (17)

- The purpose of this Fatwa is neither to gain fame, to challenge other jurists nor to gain credit for this effort (Al-Qadri 2020).

Along with this claim from the author regarding the competence to issue a fatwa, the producer hints that a fatwa may be produced to promote one’s name or fame, or to refute the positions of other experts. Despite the observation that less authoritative scholars do not title their papers officially as fatwas, there is still an obscure attempt to fight for power. Documents that were titled explicitly as fatwas were not found to explicitly discredit other documents. Moreover, there is an indirect welcoming of other voices when the phrase Allah knows best is included. Despite the fact that the origin of this phrase is rooted in classical Islamic scholarship, British culture also has indirectness embedded in its culture (Fox 2004, p. 19).

This competition for power in the discourse also involved another social actor—the National Health Service (NHS). Reference to the NHS is found in the guidance documents to establish that these documents are produced for the welfare of British Muslims. The overlapping of the two authorities occurred due to the sudden outbreak of coronavirus. A British-born Muslim has two identities—a British identity and a religious Muslim identity—which may influence the advice they choose to follow. Should they follow fatwas, guidance, or other works?

Interestingly, in Indonesia, which is predominantly Muslim, there are producers, who are willing to call themselves muftis or Muslim scholars and call their papers a fatwa with no hesitation (Wahid 2020). This shows the way in which the social and cultural context influences discourse and their participants, and how the social hierarchy and perception of power in the same religion may vary across cultures (Siebenhütter 2019).

To avoid conflicting information, scholars from the Islamic Culture Centre UK (ICCUK) merged two powerful bodies, British Islamic scholarship and the scholarship of healthcare professionals. The ICCUK plan of action reads:

- (18)

- Following the latest rulings (fatwa’s [sic]) from many reputable scholars, several Shari’ah Boards, as well as the latest UK governmental guidance and advice from medical organisations, the undersigned mosques have taken the unprecedented and difficult move to suspend all congregational services and activities (CBHUK 2020).

On the other hand, the following text from a statement argues that both religious and medical recommendations are necessary:

- (19)

- People need clear, accurate and actionable guidance to help orient their lives in a calm and informed manner. In a matter such as this, Muslims need trustworthy religious and medical advice so that they can take the proper precautions to help families and communities in need, and simultaneously raise their hands in supplication to God asking for peace and protection for humankind (AMHP 2020).

The other category has its advantages as well as disadvantages. In our digital era, this category gives an opportunity for a wider range of producers to voice themselves as experts and claim power. For instance, a group of producers were found in the other corpus to promote their suggestion to postpone fasting during Ramadan:

- (20)

- However, for those who will be unable to fast due to the strong likelihood of dehydration and severe thirst due to wearing PPE, along with the risk of making clinical errors which could potentially affect lives, the fasts can be postponed to a later date, as outlined in our Fatwa in this regard (Shabbir 2020e).

The producers of this document refer to an earlier document they published as a fatwa. On the one hand, this shows the freedom of speech and equal rights to express their opinions, which is a positive feature and mirrors the salient liberal ideology of contemporary British society (Leach 2015). On the other hand, the holy month of Ramadan, with all its practices, including fasting, is not an issue that can easily be changed by any scholar without expertise in Islamic jurisprudence, even if they proclaim their work to be a fatwa. Because fatwas produced by individuals do not have any official authority, this could be the reason that controversy was created among the general British Muslim population. This is perhaps due to the symbolic capital embedded within the manner and style in which texts are produced, meaning that they imitate the style of a fatwa.

Our CA-CDA has demonstrated that the titling of documents is not arbitrary. The differences between fatwas and guidance reveal underlying reasons for the differences in the titles chosen by the producers of the FOG documents. Among such reasons are the power relations in the Muslim community. As such, senior Muslim scholars hold a status in the community whereby they are informally empowered to call their documents fatwas. Government guidance documents are also empowered and have the same level of influence, but in a parallel domain to the religious institution. Other titles, such as statement, analysis, opinion, and so forth, along with their range of synonyms, are at the disposal of less authoritative scholars, who may choose any of these words that best describe their document. Titling rules can be seen as subconsciously shared and accepted by the pool of writers, who acknowledge the power relations in the discourse. Nevertheless, there appears to be no evidence of any official rules yet regarding the way in which Islamic documents, such as those discussed in this paper, should be titled.

The high polyphony, indirectness and diversity of the papers and their labels allowed a myriad of options regarding how Muslims should behave during the COVID-19 lockdown, how to complete religious practices in isolation, and how to adapt rituals under the new restrictions. This caused a dispute within the Muslim population, who were caught in an ongoing power struggle between senior and less authoritative Muslim scholars. Perhaps the logical solution might be a standardisation of documents, issued in collaboration with the NHS and senior muftis. By maintaining a healthy collaboration network, a clearer position could be reached in potential future emergencies (Padela and Basser 2012; Padela et al. 2011). The standardisation of document titles could also empower the British Muslim population to choose the advice that is presented to them without first needing to unravel the meanings of the titles of these documents.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we examined fatwas, guidance and other documents related to Islamic judicial and healthcare-related advice regarding COVID-19 for British Muslims during lockdown. Our corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis of these texts led us to find that the titling of documents follows an underlying hierarchy among Muslim scholars in the UK. Our analysis revealed that text producers do appear to follow particular writing conventions, at least at a subconscious level. We also found that fatwas and guidance documents are textually diametric. Other documents featured greater intertextuality and were found to respect the authority of muftis and their fatwas, but with reservations.

Text producers, including senior muftis, healthcare professionals, and other Muslim scholars in the UK, write in a register that holds high symbolic capital. Because fatwas appear to have the most authority, consequently, the fatwa register holds the highest symbolic capital. Therefore, documents intended to question fatwas are also found to be written in a similar register in order to have a similar impact. Furthermore, the references to fatwas and guidance in other documents evoke questions relating to influence. Particularly, the analysis allows us to hypothesise that some other documents are influenced by guidance documents. Moreover, other documents are aimed towards muftis so that wider issues are considered during the fatwa-writing process.

This small-scale study is limited by the data, because only COVID-19 related documents were included. Further examination into a wider range of Islamic documents may prove to be useful in order to gain additional insights into the discourse of British Muslims and how power is distributed among British Muslim scholars. The power struggle, together with the politeness in discourse created by British Muslim scholars, appears to have given rise to ambiguous and seemingly contradictory information regarding proceeding with religious practices during the pandemic. A step towards standardisation and collaboration by key stakeholders may prove to be useful for future matters related to national or global emergencies that may have an impact on Islamic rituals. Our pilot study was thus intended to give an impetus to social scientists to explore the discourse through a linguistic lens. As a tool, corpus analysis is not only useful, but is also perhaps necessary in order to empower researchers to analyse the vast number of documents published for British Muslims.

Author Contributions

Data curation, U.M. and M.A.; Formal analysis, U.M., Z.B. and R.A.; Investigation, U.M.; Methodology, U.M.; Software, R.A.; Supervision, U.M.; Visualization, U.M.; Writing-review & editing, U.M., Z.B., R.A. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 5Pillars. 2020. Hundreds of UK Mosques Remain Open for Jumu’ah Despite Closure Calls. 5Pillars. Available online: https://5pillarsuk.com/2020/03/20/hundreds-of-uk-mosques-remain-open-for-jumuah-despite-closure-calls (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Ali, Mansur. 2019. Three British muftis’ understanding of organ transplantation. Journal of the British Islamic Medical Association 2. Available online: https://jbima.com/article/three-british-muftis-understanding-of-organ-transplantation/ (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Ali, Mansur, and Usman Maravia. 2020. Seven Faces of a Fatwa: Organ Transplantation and Islam. Religions 11: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadri, Umar. 2020. Permissibility of Online Jumu’ah Prayer & Taraweeh Prayers Amidst Covid-19 Pandemic for Muslims in Ireland. Islamic Centre of Ireland. Available online: http://www.islamiccentre.ie/wp-content/uploads/Fatwa-on-Permissibility-of-Online-Jumuah-Taraweeh-during-Covid19-Islamic-Centre-of-Ireland-2.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- AMHP. 2020. Joint Statement from the National Muslim Task Force on Covid-19 Regarding the Global Coronavirus Pandemic Also Known as Sars-Cov-2 or Covid-19. American Muslim Health Professionals. Available online: https://amhp.us/covid19-statement (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Anthony, Lawrence. 2018. AntConc, Version 3.5.8. Computer Software. Available online: https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Awass, Omer. 2014. Fatwa: The Evolution of an Islamic Legal Practice and Its Influence on Muslim Society. Ph.D. thesis, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Paul. 2018. Corpus methods in linguistics. In Research Methods in Linguistics. Edited by L. Litosseliti. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 167–92. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Paul, Costas Gabrielatos, and Anthony McEnery. 2013. Discourse Analysis and Media Attitudes: The Representation of Islam in the British Press. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BBSI. 2020. Declarations. British Board of Scholars and Imams. Available online: http://www.bbsi.org.uk/declarations/ (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Biber, Douglas, Susan Conrad, and Randi Reppen. 1998. Corpus Linguistics: Investigating Language Structure and Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, Gavin, and Anthony McEnery. 2020. Correlation, collocation and cohesion: A corpus-based critical analysis of violent Jihadist discourse. Discourse & Society 31: 351–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunt, Gary. 2003. Islam in the Digital Age: E-Jihad, Online Fatwas and Cyber Islamic Environments. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, Muhammed Zubair. 2019. Organ Donation and Transplantation in Islam: An Opinion. NHSBTDBE. Available online: https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/16300/organ-donation-fatwa.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Caeiro, Alexandre. 2017. Facts, values, and institutions: Notes on contemporary Islamic legal debate. American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 34: 66–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBHUK. 2020. Hajj Advice 2020. The Council of British Hajjis UK. Available online: http://cbhuk.org/hajj2020 (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- CCI. 2020. Ghusl, Janazah & Burial During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Canadian Council of Imams. Available online: http://canadiancouncilofimams.com/wp content/uploads/2020/03/CCI_MMAC_Ghusl-and-Burial-Guidance.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Coates, Jennifer. 1987. Epistemic modality and spoken discourse. Transactions of the Philological Society 85: 110–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darics, Erika, and Veronika Koller. 2019. Social actors “to Go”: An Analytical toolkit to explore agency in business discourse and communication. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly 82: 214–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Norman. 1989. Language and Power. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 1995. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Boston: Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2010. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2013. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Noah. 2005. The democratic fatwa: Islam and democracy in the realm of constitutional politics. Oklahoma Law Review 58: 1–9. Available online: http://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1255&context=olr (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Foucault, Michel. 1982. The subject and power. Critical Inquiry 8: 777–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Kate. 2004. Watching the English: The Hidden Rules of English Behaviour. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Kakakhayl, Mohammed A. 2020. Questions Regarding Covid-19 in Regards to Masjid and Madrasa Attendance. Eternal Gardens. Available online: https://eternalgardens.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Questions-regarding-Masjid-and-Madrassahs.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Karlberg, Michael. 2005. The power of discourse and the discourse of power: Pursuing peace through discourse intervention. International Journal of Peace Studies 10: 1–23. Available online: http://myweb.facstaff.wwu.edu/~karlberg/articles/PowerofDiscourse.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Koller, Veronika. 2012. How to analyse collective identity in discourse-textual and contextual parameters. Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis across Disciplines 5: 19–38. Available online: http://www.academia.edu/download/31637581/CADAAD_2012_Koller.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Leach, Robert. 2015. Political Ideology in Britain. London: Macmillan Education. [Google Scholar]

- Maravia, Usman. 2020. Rationale for Suspending Friday Prayers, Funerary Rites, and Fasting Ramadan during COVID-19: An analysis of the fatawa related to the Coronavirus. Journal of British Islamic Medical Association 4: 10–15. Available online: https://jbima.com/article/rationale-for-suspending-friday-prayers-funerary-rites-and-fasting-ramadan-during-covid-19-an-analysis-of-the-fatawa-related-to-the-coronavirus (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Mautner, Gerlinde. 2016. Checks and balances: How corpus linguistics can contribute to CDA. In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. London: Sage, pp. 155–80. [Google Scholar]

- McEnery, Anthony, and Paul Baker. 2015. Corpora and Discourse Studies: Integrating Discourse and Corpora. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- McEnery, Anthony, Richard Xiao, and Yukio Tono. 2006. Corpus-Based Language Studies: An Advanced Resource Book. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- NHSBT. 2019. New Fatwa to Clarify Islamic Position on Organ Donation. Available online: https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/get-involved/news/new-fatwa-published-to-clarify-islamic-position-on-organ-donation/ (accessed on 30 June 2019).

- Ottenheimer, Harriet. 2008. The Anthropology of Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology. Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Padela, Aasim, and Taha Basser. 2012. Brain death: The challenges of translating medical science into Islamic bioethical discourse. Medicine & Law 31: 433. Available online: http://www.academia.edu/download/33648678/padela_basser-BDchallengestranslatingintoislamiclaw.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Padela, Aasim, Hasan Shanawani, and Ahsan Arozullah. 2011. Medical experts & Islamic scholars deliberating over brain death: gaps in the applied Islamic bioethics discourse. The Muslim World 101: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisigl, Martin, and Ruth Wodak. 2016. The Discourse-Historical Approach DHA. In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. London: Sage, pp. 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwat, Ahmad. 2014. Ushul Fiqih Ringkas [Concise Juridical Principles]. Jakarta: Rumah Fiqih Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin, Deborah. 1994. Approaches to Discourse. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Shabbir, Yusuf. 2020a. Coronavirus: Should Masjids Close? Islamic Portal. Available online: https://islamicportal.co.uk/coronavirus-should-masjids-close (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Shabbir, Yusuf. 2020b. Burial of Covid-19 Bodies and Ghusl. Islamic Portal. Available online: https://islamicportal.co.uk/burial-of-covid-19-bodies-and-ghusl (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Shabbir, Yusuf. 2020c. Ghusl for Coronavirus Infected Bodies. Islamic Portal. Available online: https://islamicportal.co.uk/ghusl-for-coronavirus-infected-bodies (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Shabbir, Yusuf. 2020d. Coronavirus Deaths and Ruling on Ghusl. Islamic Portal. Available online: https://islamicportal.co.uk/coronavirus-deaths-and-ruling-on-ghusl (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Shabbir, Yusuf. 2020e. Covid-19 and Guidelines for Ramadan and Eid. Islamic Portal. Available online: https://islamicportal.co.uk/covid-19-and-guidelines-for-ramadan-and-eid (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Siebenhütter, Stefanie. 2019. Sociocultural influences on linguistic geography: Religion and language. In Southeast Asia. Handbook of the Changing World Language Map. Edited by Stanley D. Brunn and Roland Kehrein. New York City: Springer, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Skovgaard-Petersen, Jakob. 1997. Defining Islam for the Egyptian State: Muftis and Fatwas of the Dar Al-Ifta. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, Omar. 2020. On Virtual Taraweeh. Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/imamomarsuleiman/posts/3109422849077735 (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Thandi, Gurdip. 2020. ‘True Gentleman’ the Latest Tragic Victim of Covid-19 in Walsall. Birmingham Mail. Available online: https://www.birminghammail.co.uk/black-country/true-gentleman-latest-tragic-victim-17981536 (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Van Dijk, Teun. 1993. Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society 4: 249–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, Theo. 1996. The representation of social actors. In Texts and Practices: Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis. Edited by Carmen Rosa Caldas-Coulthard and Malcolm Coulthard. London: Routledge, pp. 32–70. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2006. Critical discourse analysis. In Encyclopaedia of Language and Linguistics. Edited by Keith Brown. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 290–94. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2008. Representing social actors. In Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Analysis. Edited by Theo van Leeuwen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid, Muhammad. 2020. Rumah fiqih Indonesia: Challenging the fatwa shopping. Misykat Al-Anwar Jurnal Kajian Islam dan Masyarakat 3. Available on line: https://jurnal.umj.ac.id/index.php/MaA16/article/view/5549/3875 (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Wodak, Ruth. 2001. The Discourse–historical approach. In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. London: Sage, pp. 63–94. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For a detailed analysis of the fatwas surrounding these matters, see Maravia (2020). |

| 2 | For more details on corpus building, see Mautner (2016) and Baker (2018). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).