1. Introduction

Millennia after millennia, religiousness and amazement have often gotten along well enough, because wondering is the art story tellers master when they seek to impress, and what they cause is a smile, and what they reap is applause. In a similar vein, amazement is what brings together priests (lamas or shamans) and parishioners when they build temples to the further glory of Very Important Persons, and their images are carried out in colorful processions in feasts and holy days. Throughout history and across cultures, religion and humor have been acknowledged as universals, but their nexus has been overlooked, and has received scant attention from psychologists, psychiatrists, philosophers, and anthropologists during the 20th and 21st century (

Carbelo-Baquero 2006). Homo Religiosus and Homo Ridens business cards have been exchanged once in a blue moon. Their profile is different: religious versus laughing persons.

The notion of Homo Ridens (laughing person) may be dated back to Aristotle (384–322 BC). He made clear in his essay On the Parts of Animals that men and women are the only animals that laugh (

Aristotle 350 BCa, Book I, Section 10), and in his essay History of Animals stressed that the first laugh marks the baby’s transition to humanness, and the primary evidence of having acquired a soul in the new-born was laughter (

Aristotle 350 BCb, Book VII, Section 10). This cut-off point has been the secular criterion used by Orthodox and Catholic church persons.

Homo Risibilis (laughable person) is a variant advanced by Democritus (460–370 BC) as self-referential laughter. It was regained in the 11th century by a Benedictine monk, Notker Labeo, in his commentary on Aristotle’s Categories. “It means the ridiculous human being, and its thesis is that being aware of our necessary ridicule liberates us from it” (

Amir 2014). Seneca (4 BC–65 AC), Thomas More (1478–1535), Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592), and Friedrich Nieztsche (1844–1900) found themselves in such humor. On this trail, two Nobel prize winners in Literature published essays, Henri Bergson in 1900 (1859–1941), and Luigi Pirandello in 1908 (1867–1936). Their perspective was peculiar of humanities, that is, belles-lettres, sometimes yes, sometimes no, the antithesis of divinity studies.

The notion of Homo Religiosus (religious person) may be dated back to Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BC). He mentioned “homines religiosi Sibyllae placere dixerunt”, that is “religious persons to please the Sybils, they said “in his Letters to the Friends (1.7.4). Their target was the world of augurs (in caves, in lakes), of omen and oracular books (in the tradition of Nostradamus) at the disposal of the Senate as vade mecums in case of natural disasters and supernatural prodigies. Ritual prescriptions prevailed, that is, liturgies, but not theology (

Palacios Chinchilla 2015). In the 20th century, this notion was rescued by Gerardus Van der Leeuw (1890–1950), and highlighted by Mircea Eliade (1907–1986): the Homo Religiosus “always believes that there is an absolute reality, the sacred, which transcends this world but manifests itself in this world, thereby sanctifying it and making it real” (

Eliade 1963, p. 202). Their perspective was divinity studies, the antithesis of humanities, of natural or of social sciences, sometimes yes, sometimes no among top decision-makers in universities.

The first objective in this article is the contrast between the laugh of God and the sin of laughter. It is approached in

Section 2. It is the backbone of this inquiry on how religious men and women digested centuries with or without a sense of humor. Religiousness is what psychologists mainly examine, that is individual beliefs or practices, acts, attitudes, abuses, conversions, feelings, mental health, social behaviors; in the terminology of William James (1842–1910), the varieties of religious experiences. However, they do not so much examine religions, understood as “an institutional (and thus primarily material) phenomenon, defined by their boundaries, differentiated by requirements of membership” (

Miller and Thoresen 2003, p. 27) where sacred texts breed discourses of a theological or moral deliberation.

Daniel Kahneman, a professor of Psychology who obtained the Nobel award in Economics in 2002, made it clear in his autobiography: “I was more interested in what made people believe in God than I was in whether God existed, and I was more curious about the origins of people’s peculiar convictions about right and wrong than I was about ethics” (accessible in the website of the

Nobel Foundation (

2002)).

The second objective is to annotate a psychological model that crumbles the process that underlies in the nuances and contrasts achieved when someone makes others smile with reference to a concrete religion, and for those religious believers that smiled, acknowledging that what they heard or saw amused them. In

Section 3, this model is identified, and jokes with religious connotations are scrutinized as examples. In the same vein, images used as macro-memes online get verbalizations that emerge and detect instances of stereotypes about religious persons, congregations, or ways of dressing that give rise to popular jokes of good or bad taste, which often reflect appreciation or contempt. The incongruity model discloses the psychological mechanism involved in the emergence of amusement and laughter in the disparity between what appears as appropriate or inappropriate. From there, it follows to feel offended or not offended, and for those who are annoyed to speak of sin, if the one who jokes or laughs is a parishioner.

The third objective is to spell out what happens when religious authorities or practitioners consider it a transgression what is at stake, and dissuasive measures need to be undertaken.

Section 4 addresses a model that deals with the use of transgression in graphic designs, paintings, sculptures, galleries, and exhibitions. Those who are influential, and decide, point out that religiosity and sense of humor have their limits, and by default are incompatible, and the inquisitors appear and are self-confident, and understand they have something to say and do. One consequence is that clerical or not clerical judges know how to sit on the bench of the accused, painters, singers, dancers, entertainers that in their sets, with their makeup, with their jocularity evidenced they were transgressors, and their art was questioned, and often have been condemned because the cloth with which the soutanes are made also make the gowns. The crochet sleeves of the classic priest’s albas, and the crochet sleeves worn by magistrates, prosecutors and court lawyers come from the same or similar workshops. Thus, humor is dangerous because the humorist invents ways of seeing the same facts, the same sacred faces, the same rites, and ceremonies hilariously, and the joyful heart of readers, observers, and jesters just sweep. If they are brilliant, their self-esteem is clairvoyant: they are the true rebels.

These are conceptual and long-established terms in the field that appear here and there in this article. This is the background.

The fourth objective changes the focal point. Sense of humor cannot be reduced to jokes, because humor manifests itself in everyday situations in which the wit of the humorist reaps smiles and laughs; sometimes positive humor, sometimes negative, sometimes about oneself, sometimes about relatives, either at home or in the workplace. In psychological terms, the outcome may be two quandaries: affiliative versus aggressive humor, self-promoting versus self-deprecating humor (

Martin 2003).

Section 5 examines 11 categories in the context of social interactions where religious topics and jocoseness come in and out in conversations, in celebrations, in death and memories. It is a taxonomy of religious laughter.

The focus of this article is on a sample of creative religious authors exhibiting astonishment and sense of humor. They had been painters, sculptors, writers, nuns or monks, story tellers: they produced, they invented, they dreamed up, and knew how sensitive religious topics are, in some religions, but not in all. In general, they were all considered troublemakers, blasphemous, post-mortem sinners, all their impious masterpieces confiscated, their graves destroyed because a crowd decided it so: a crowd or the chief executive officer or a cabinet in control without any right to appeal, without any defense attorneys, and with only prosecutors.

A theocracy is not a democracy, and theocratic laws have, why not, a divine origin, revealed. Thousands of humorists have been martyrs because they shared an archetypal and esoteric belief: innocuous art will decline very soon. The shocking masterpiece comes before or after the controversy. It may be considered inappropriate because its offensive subject matter may outweigh the rest. The target/objective may be inappropriate because someone is ready to behave like a god and get away with it. It was inappropriate, out of place, four centuries ago, but not the day after tomorrow in this place or emergency. Camouflage is not only a self-protection device (of subject, target, or time) but, why not, for instance, an old but heretical divinity in disguise, transformed, without warning, with a new look, believe it or not.

A case study of narratives and graphics has been the methodology used, and examples are integrated into those categories hanging, each time, from the previous numbered epigraph.

2. From the Laugh of God to the Sin of Laughter

The two verses of Psalm 2 (mentioned before the introduction) seem to be the first of two passages in biblical literature where it is mentioned that God laughs and scoffs. The context is a prayer song emphasizing that when a nation rages, God laughs, and destruction is the aftereffect because, suddenly, the wrath of God steps in. In Psalm 37:13, “the Lord laughs at the wicked, for he knows their day is coming” reveals the same mindset: the settling of accounts. Fearsome is the Lord who laughs (Deus Ridens). Stronger He is, and has the final say.

It is not a surprise, Exodus 13:21 is more explicit: “By day the Lord went ahead of them in a pillar of cloud to guide them on their way and by night in a pillar of fire to give them light, so that they could travel by day or night”. What is described is a volcano, and whoever has stood by its side knows that this is not a peaceful setting. Thus, the Lord and the pillar of smoke, the Lord, and the tongue of fire, all three deserve each other. A dreadful experience: King of Tremendous Majesty. “Neither the pillar of cloud by day nor the pillar of fire by night left its place in front of the people” (13, 22). Hence, His anger is biblical.

In the Quran, in Surah 53:43, it is highlighted that it is God who makes people laugh and weep. Left to their own devices, men and women cannot laugh. By themselves, there are no Homo Ridens. Divine determination prevails: no autonomy in human mood. That is all. In both traditions, the laughter of God is not a playful or funny moment. In other words, there is very little laughter in Semitic religions. Yahweh and Allah cannot be mocked, nor His messengers. The exception, Pontius Pilatus’ soldiers: they had a great time with their gibes when they decided to honor the crowned king of Jews: from Nazareth, Jesus.

It is not the case in the cluster of religions known as Hinduism. In the Hindu pantheon, Ganesha is the elephant head created by Shiva’s laughter. It is the “laughing God”, venerated not only in Hindu religious settings, but also in Buddhism and Jainism. In Japan, the Sun Goddess Amaterasu decided to lock herself up in a cave because she was angry with her brother, the Storm God. The eternal night was the outcome, and she decided to come out when the Goddess of Fertility danced with erotic movements and a large number of deities laughed aloud. The consequence is a connection between laughter and fertility in everyday language in Japanese, and thus, in several Shinto shrines, there are annual festivals where “Laugh, Laugh, Laugh!” is proclaimed in unison when parishioners dance, for instance, in Nagoya where the Atsuta Shrines organizes the annual Laughter Festival.

In Greece, funny were the extramarital adventures of Zeus: many neighbors felt inspired to talk about them slyly during the nightfall. The Dyonisia and the Anthesteria festivals in Athens were organized annually to honor God Dyonisius: laughter and happiness set the tone at sunset and at sunrise.

In Buddhism, it is known that Buddha remained silent when he was asked by Hindus about God and its existence. “Let’s not talk about this” is the typical answer that many monks learn by heart to avoid getting out of control. What is ubiquitous is that Buddha kindly smiles in sculptures and paintings, where his face is what is remembered. A word to the wise is enough.

The “sin of laughter” is a Catholic expression, well known in Spain, which may be traced back, first, to Plato (427–347 BC) because in his dialogue, Philebus, he makes clear that laughter—discerned as typical of Homo Risibilis, a laughable person—is a vice, and in The Republic, he connects laughter with violence (in Book 3) and with dishonor (in book 5). But laughter is viewed as a sin in the 4th century by Desert Fathers in the early Church history (

Smith 1931). The source were friars, instructor monks that often became priests, and, years later, bishops that preached and the parishioners that listened, and remembered that Jesus had “nowhere laugh, nay, nor smile but a little, no one at least of the evangelists had mentioned this. With regard to Paul, that he laughed, neither hath he said himself anywhere”. This is the historic argument of John Chrysostom (second half 4th century) in his sixth homily “on the gospel of Matthew” (

Chrysostom and Poer 2012, pp. 245–70). Furthermore, a very old remark attributed to the Greek dramatist Menander (342–290 BC), was remarked boringly whenever sense of humor emerged: “laughter is abundant in the mouth of fools” with the intention of playing down any hilarity in religious celebrations.

In the 21st century, the long-term consequences of such a reprehensible “sin of laughter” were tested psychologically at the Catholic University of Louvain through an experiment carried out in the laboratory (

Saroglou and Jaspard 2001). Twenty-nine participants watched a religious documentary, 27 individuals watched a humorous one, and 29 composed the control group. “This experimental study indicated that not only religiosity is negatively associated with humor creation but also that religion affects this humor performance. Religion, both as a trait and as a state, seems to predict low humor spontaneous responsiveness” (p. 42). “The hypothesized negative association between religious measures and humor creation turned out to be true only in the religiously stimulated group” (p. 43).

Previous studies (based on personality research with questionnaires) (

Saroglou 2002) also mentioned that “people high in dogmatism perceived themselves as not very humorous and needed more time to recognize humor than people low in dogmatism” (p. 193). Somehow, Homo Religiosus is not Homo Ridens.

This kind of religious practitioner is quite sensitive to what they consider the truth, with a great fascination with the literal truth of sacred text, with translation problems due to variations in language itself. St. Paul’s remarks in his epistle to Ephesians (5:4) are unequivocal: those living in Christ ought not to laugh, and not even to suffer laugh makers. If they get caught up in the moment, God’s wrath will come.

Using a survey style approach,

Ott and Schweizer (

2018) used 18 jokes and cartoons with religious connotations, and 6 clever religiously irreverent phrases. Online, 783 respondents (plus 294 unreliable surveys that were dismissed) appraised which ones were intelligible, funny, or offensive. A minimal floor value of 50 participants was used to differentiate between those identifying themselves as Agnostic (100), Atheist (80), Christian (153), Hinduist (52), Muslim (57), as well as non-practicing in each of the other faiths (75). The “others” category (17) included Jews, Buddhists, and Mormons. There was also a control group of 254 individuals who marked the other unspecified option as religion. These are their main findings.

Hindus excelled other groups in their ratings on funniness (above average in all the 24 jokes), and were second in offensiveness. They considered two thirds of jokes offensive, but funny.

Muslims eclipsed other groups in offensiveness, but they acknowledged that annoying jokes may be, also, “slightly funny” or okay, that is, they avoided the highest funniness ratings. A nuance to consider is that 95% of Muslims in the sample were between 20 and 39 years old, and they were online users.

The lower ratings in funniness in all the jokes were marked by Christians. Once more, Homo Religiosus and Homo Ridens were like water and oil.

Muslims and Christians marked as offensive jokes they considered targeted their respective religions.

Very low was the percentage of jokes considered offensive by Atheists and Agnostics.

A joke rarely was considered offensive by Atheists, who enjoyed irreverent jokes, and were less amused by well-mannered religious jokes. They marked as funny or hilarious jokes considered blasphemous by other groups.

In their responses to non- offensive jokes, no differences were detected between Atheists and Christians.

The number of Jews and Buddhists in the sample was irrelevant, thus they will not be addressed in this section.

3. The Sin of Laughter: The Incongruity Model

3.1. A Rational Psychological Background

It is somehow a paradox to start an article on the nexus between psychology and sense of humor quoting a not so well-known German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), notorious for his pessimism. He is also rarely quoted by psychologists with a scientific background because he was a rather speculative rational psychologist who often avoided illustrating his explanations with concrete examples, anecdotes, or reliable facts.

In his first inquiry approaching the world as representation (1818), he highlighted the seriousness and value of laughter because it “results from nothing but the sudden perceived incongruity between a concept and the real concepts that had been thought through it in some relation; and laughter itself is just the expression of this incongruity” (

Schopenhauer 1969, p. 59).

He followed the steps of Inmanuel Kant (1724–1804), focusing on the process of artistic creation and genius by delving into the sense of humor present in their work as artists: “Whatever is to arouse lively, convulsive laughter must contain something absurd (hence something that the understanding cannot like for its own sake). Laughter is an affect that arises if a tense expectation is transformed into nothing” (

Kant 1987, p. 203).

Anyhow, Homo Ridens has a rare perspective. Something absurd in the terminology of Kant is what, in the next section, will be approached, psychologically, as incongruity. “By absurd Kant means nosense: “how do crazy people find their way through the forest? They take the psychopath”. The pun here is a non sequitur; it has nothing to do with ascertaining one’s direction. It is an incongruous answer to the question” (

Carroll 2021, p. XVIII).

3.2. An Experimental Psychology Background

This understanding of how laughter emerges cognitively was substantiated experimentally, 123 years later, by

Eysenck (

1942), with three humor tests that included 100 verbal jokes, 52 humorous drawings with captions, and 37 paired photos sharing one similarity as well as other entirely different details: “laughter results from the sudden, insightful integration of contradictory or incongruous ideas, attitudes, or sentiments which are experienced objectively” (p. 307). The outcome is the emotion of joy, acknowledged in their answers by the subjects ranking the three sets of items in their order of funniness.

Here is an example of the verbal joke category:

“I hope you are not afraid of microbes”, apologized the paying teller as he cashed the school teacher’s check with soiled currency.

“Don’t worry” returned the young lady, “no microbes could live on my salary”.

In the wording of Schopenhauer in 1818, “all laughter therefore is occasioned by a paradoxical, and hence unexpected, subsumption, it matters not whether this is expressed in words or in deeds” (

Schopenhauer 1969, p. 59). In the wording of Eysenck, “other things being equal, the funniness of a joke is a direct function of the degree of contradiction or incongruity between the main ideas, attitudes, or sentiments contained in it, and the quality of the integration of these elements, as measured by the suddenness of, and the degree of insight resulting from, this integration” (p. 307).

In operational terms, jokes are “context-free and self-contained in the sense that they can be told in many conversational contexts” (

Long and Graesser 1988, p. 37). All the information needed (a narrative schema as stimulus) is dramatized by the storyteller, and predictions are launched by listeners, and they react because there is a mismatch between what they advanced and the oddity. The answer may entail amusement or puzzlement. Each joke, like a quiz, requires apprehension. This justifies why psychological researchers started to use jokes as tests. It is easy to transform adscriptions or answers to quantitative data and, thus, statistical analyses to identify reliable taxonomies and trends.

The qualitative approach entails creating or recreating the content, and the cognitive framework is discerning the subtext, and the outcome entails focusing more on sense of humor (instead of coarse manners, antipathy, or violence), taking into consideration that at least three characters are involved: (a) the humorist, that is, the Homo Ridens, the proactive author or clever mind; (b) the storyteller or entertainer; and (c) the audience, passive, and attentive listeners. The channel is the narrative they share: a joke is something that is said (written or drawn) to make people laugh.

3.3. An Information Processing Background

Thirty years later, another psychologist, Jerry M. Suls, started to study sense of humor as a particular and typical instance that illustrates how information-processing and problem-solving may come together (or may go off the point), and the outcome, spontaneous, a smile or a frown. His understanding of Homo Ridens was rooted in a new field of expertise, known as artificial intelligence, generated by the first two psychologists who obtained the Turing Award in 1975 (Computer Science, that is, Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon), and the Nobel Award in Economics in 1978 (Herbert A Simon).

Funny or not funny, the story is the result of a four-stage process. The first two, expectation and problem-solving, are a matter of cognitive understanding on what is going on. The third concerns reaction time, quick is the added value. The four conform a succulent bait to pick up the fish.

These three examples may facilitate an understanding of what the expectation stage and, afterwards, the problem-solving stage entail. These examples have been selected because there is a religious atmosphere. At first glance, they are not offensive.

When I was a kid, I used to pray every night for a new bike, until I realized the Lord doesn’t work that way. Thus, I stole one and asked Him to forgive me instead.

“My husband and I agreed to divorce for religious reasons. He thought he was God. I didn’t”.

The mother superior said to a novice, “with prayer open this meeting” and so she did in a soft voice. Two seats away, another nun, strained to hear, shouted: “I cannot here you!” The novice replied, “I am not talking to you”.

“In the first stage the perceiver finds his expectations about the text disconfirmed by the ending of the joke” (

Suls 1972, p. 82). Listeners find a discrepancy between their initial expectations about the story line and what comes to light by the ending phrase or word. In the first example, the illusion of a bike crops up, and God’s forgiveness is the reliable aftereffect. In the second example, the bull’s eye is the connection between the high self-esteem of her husband and the agnostic decision-making approach of his wife. In the third example, the ground zero is why praying and hearing-impaired frailty emerge together.

“In the second stage, the perceiver engages in a form of problem solving to find a cognitive rule which makes the punch line follow from the main part of the joke and reconciles the incongruous parts” (p. 82). The person tries to find out a logical, an intuitive or metaphorical way of thinking that resolves the amazement with the preceding narrative. The incongruity is rendered meaningful suddenly during the “aha!” juncture. In the first example, the faster quick fix is stealing. In the second, a divine self-esteem is not a sinful circumstance, but it is underappreciation by the wife. In the third example, the fine distinction is of who is talking with whom when praying coincidentally.

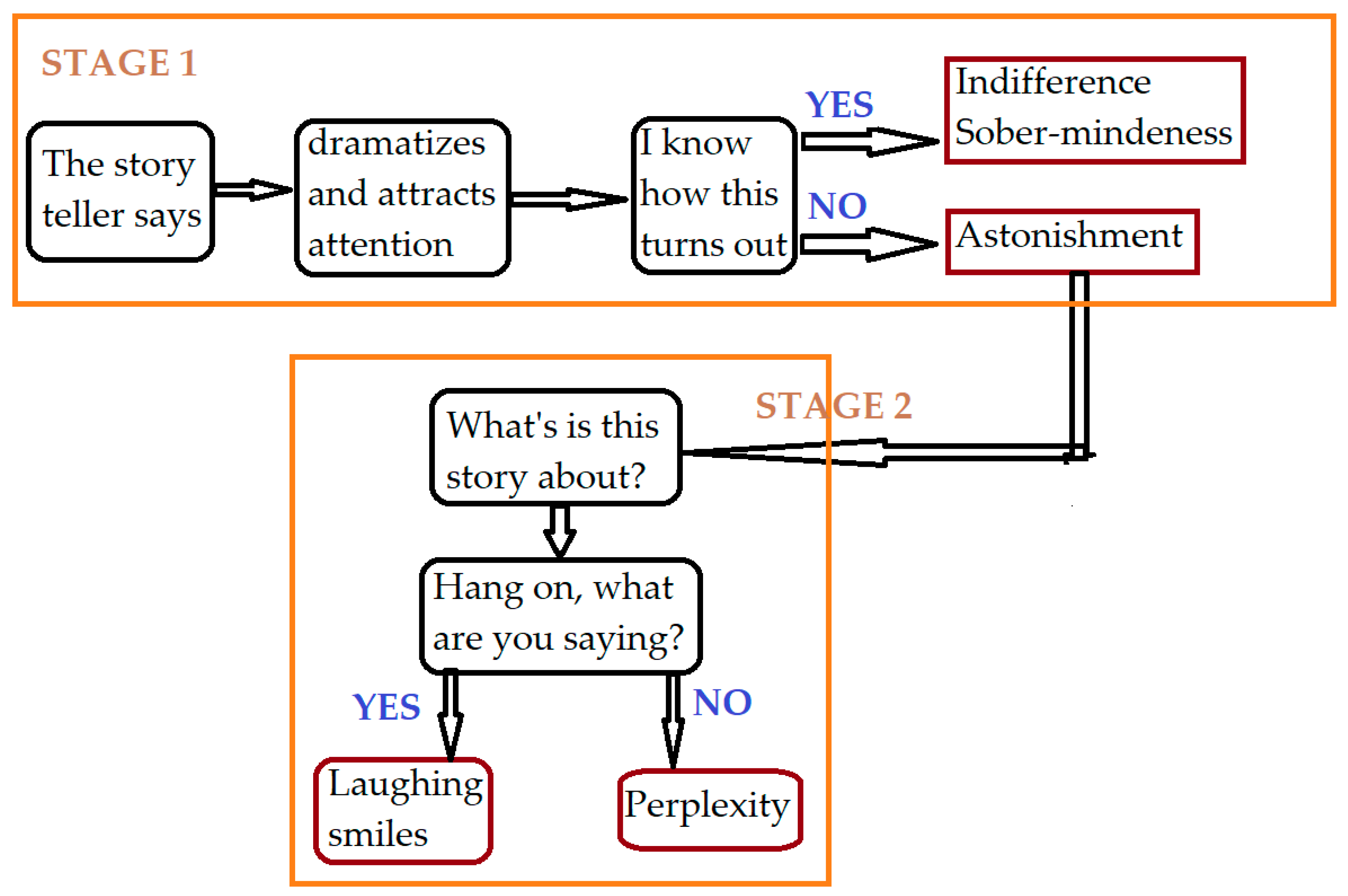

Figure 1 is

Suls’ (

1983) revised diagram that illustrates the proactive maneuver to combine suitably expectation with problem-solving.

“Incongruity of the joke’s ending refers to how much the punch line violates the recipient expectations” (

Suls 1972, p. 92). Storytelling is involved, because there is a narrative schema that is changed suddenly in the last phrase.

Literal meanings are explored first, and figurative meaning is surveyed if the initial connotations are disconfirmed by the ending. Sometimes, listeners guess alternative views, and start to smile or laugh before the punch line is revealed.

There is an overlap between these two stages emphasized by Suls empirically and those conjectures underlined by

Kant (

1987): “Humor means the talent for being able to put oneself at will into a certain frame of mind in which everything is estimated on lines that go quite off the beaten track (a topsy-turvy view of things) and yet on lines that follow certain principles, rational in the case of such a mental temperament” (p. 336). The reason-trick is to use no-reason, and the blow off is Homo Ridens.

Figure 2 is a variation of Suls’ diagram, developed by the author of this article, taking into consideration Kant’s suggestion, something rational versus something absurd. Distinctions, such as convergent versus divergent thinking, identified through factor analysis by the psychologist Joy P. Guilford (1897–1987), common-sense versus non-conformist argument (in the area of critical thinking), null versus alternative hypothesis (substantiated via statistical predictions with data), orthodoxy versus heterodoxy (notably relevant in the Christian tradition) are just categories to clarify why Homo Ridens and Homo Religiosus require a conventional and politically correct mindset, contrasted to an unconventional and iconoclastic mental make-up.

Convergent thinking is a psychological ability to look for logical and exclusive solutions to a problem, and it is somehow overlapped with what is meant as deductive thinking in philosophy. The common-sense argument is a way of alluding to factually disclosed hypotheses, gradually communicated, and shared via good judgement. The null hypothesis is a prediction that does not bring anything really new. It adds nothing to the situation. An orthodoxy in religious terms means the opinion, the belief, the dogma that is considered right, tailor-made by the hierarchy.

If a person follows this kind of train of thought, then laughter is not the sudden and quick outcome. No surprise emerges, but bewilderment appears.

In contrast, divergent thinking operates in the domain of creativity and inventiveness where different solutions are suitable for a given problem. It includes originality and variety. Non-conformist arguments entail changing the perspective, for instance, seeing daily life affairs standing with one’s head on the floor (this is a challenging and astonishing yoga exercise). An alternative hypothesis is a prediction that brings something new, with which advanced effects and relationships are confirmed. Heterodoxy entails disagreement in the way the Homo Religiosus deals with doctrines, system values, and priorities. It includes a dissatisfaction that gives rise to initiatives to discover new satisfactory outcomes or achievements. Laughter, joy, humor are the successful outcomes of these trains of thought. A defeat then flows into puzzlement.

Heterodoxy is the Achilles heel in the Homo Ridens, because often the outcome is considered provocative, disturbing, and sooner or later, it ends up in the news. In some countries, the religious Homo Ridens ends up in prison. They are rarely freedom fighters because their approach to dilemmas is intellectual.

The third stage deals with the time elapsed in the process of tracking the narrative, and finding out the common- or non-common-sense connotation implicit in the problem-solving condition. That is, the eureka moment that reconciles incongruous and congruous undertones. Almost instantaneously, the cognitive surprise effect, the clue, the solution is found: the sooner, the better the quintessential is. Spontaneously, the laughter, the smile looms. If it takes longer, the hint is lost, and a little bit confused; the person stops, and will not try a new solution again. No revelation, no laughter. It is the exact time of a joyful epiphany. Not catching the cognitive rule is a dead end in Suls’ model because the laughable way is, without a doubt, conspicuously absent.

The four stages may be approached metaphorically as a fishing tackle the storyteller uses to attract the attention of the audience, and manipulate and encourage the expression of emotions.

During the past four decades, Suls’ model has been examined and validated in different countries and research disciplines. To make the list short, only the last two studies detected are mentioned.

In Taiwan,

Wu and Chen (

2019) used Chinese ideograms and psychological quantitative tests, questionnaires, as well qualitative data, based on hilarious anecdotes, on a sample of 103 university students. “The results indicated that, after controlling for the influence of age and gender, the remote association was positively correlated with the incongruity resolution via humor comprehension, performance on insight problem solving positively predicted nonsense humor comprehension, and divergent thinking had no direct connection to either type of humor comprehension. This result is indicative of the specific association between the different cognitive components of creativity and the different types of humor comprehension” (p. 116). In fact, divergent thinking is mainly involved in the process of creating or improvising a humorous solution different from the one being heard.

In Spain,

Yus (

2020) developed an incongruity-resolution strategy that was tested first to classify 12 verbal jokes, and later, to classify 150 images—macro memes compiled via random search on the internet. The author differentiated between the type of incongruity and the iconographic expression.

A typical example of a meme that combines Homo Religiosus and Homo Ridens was raised in April 2021 by several European influencers campaigning for Muslim women’s rights. They protested against the ban of the veil in France or in Belgium, and denied that it was an oppressive ornament in Islam (

Figure 3).

It may be interpreted differently before and after the mass flight that took place the last week of August 2021 in which Afghan mothers with children at the airport of Kabul were terrorized by Taliban, and afraid of their life expectancy if they remained in the country where they were born and had obtained educational and professional degrees, as well as internal autonomy and outside recognition.

It became a meme because there have been imitations and different versions regarding the image with a headscarf: one person; several persons; a multitude. The top and the bottom text are the same, but together, they illustrate, psychologically, the incongruity model by checking out the emotional reaction at first glance, or after weighing other options.

It may have become a macro-meme if only the top text, “hands off” and the image appeared, and the second line was left open to obtain the comment, the suggestion that substitutes “my hijab”. It is intended that it reflects the attitudinal reaction of those persons answering, for instance, cases of Islamophobia.

It may be considered a social satire with religious connotations because how it is read by men or women, by Western or by Muslim women, by journalists, politicians, by religious leaders can be tested. The key issue is the ingenious suggestion, or the nonsensical interpretation.

“Memes are artifacts of digital culture that offer information about the culture that creates and distributes them through multimedia text messages, video, gifs, etc. on electronic media such as social networks, showing, in an ironic or satirical tone, situations or everyday events in the life of the group of people who share them” (

Cancelas-Ouviña 2021, p. 2).

4. The Sin of Laughter, the Transgression Model, Camouflage

Humor cannot be reduced to jokes because what produces amusement relies on a highly specific shared knowledge. The topic approached in the present conversation is context-bound to speakers and listeners in interaction. In English, the expression is wit. “The goals of the speaker are very different when planning a witty statement than when telling a joke. Wit differs from jokes in that its capacity to amuse is often secondary to social and communication goals. Jokes are highly stylized forms of expression. The cues that occur preceding a witty utterance may be subtler: a smile or a dead-pan expression” (

Long and Graesser 1988, p. 38). In operational terms, clever and amusing remarks are the white and the yolk of witticism. The umbrella is social psychology, because interpersonal interactions are involved.

In this section and in the next two sections, droll and surreptitious examples of witty and circumspect authors of chef d’ oeuvres, are introduced and mentioned briefly. They have been clever in public, and experts in camouflage, as required in their art. What audiences grasp is literarily or pictorially visible and reasonable, but what was intended adroitly remains inconspicuous and unnoticeable until the time comes for that guru to transform what was exoteric (that is, public) to esoteric (confidential) knowledge.

The first of these examples, Michelangelo’s mentor in his understanding of Hebrew names, biblical characters, open questions, perplexities, and teachings was, in Florence, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), the pioneer in what became known as Christian Kabbalah. That is, the Jewish spiritual practice baptized. Heavy metals analysis, carried out on his bones and mummified tissues, showed that there were potentially lethal levels of arsenic. He was poisoned (

Gallello et al. 2018). In Rome, the Italian painter, sculptor and architect, Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) fraternized with the clandestine group of Catholic humanists, known as the Spirituali, mentored by the British Cardinal Reginald Pole (1500–1558). The year before his death, he faced a troubling investigation for heresy launched by the Pope Paul IV (1476–1559). He ordered to cancel Michelangelo’s annuity from Saint Peter’s budget, and the elimination of his nudes in the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. Only Michelangelo knew how to build the scaffold needed; no other succeeded. In his deathbed, he ordained the destruction of all his manuscripts, notes, and sketches (

Blech and Doliner 2009). He was a hidden dissident, a heterodox, but not yet a heretic. In psychological terms, divergent thinking.

4.1. Graphic Humor and Transgression in Catholic Fine Arts: Camouflage

During the 20th century, graphic humor incremented its presence in mass media, but also in fine arts museums, sharing space and visitors with classical paintings, drawings, sculptures of religious contents, anecdotes of founders, leaders, myths, ceremonies, etc. From time to time, cases in dispute came to light as main news items on media broadcasting, newspapers, or magazines. For instance, the emotional reaction of Muslim worshippers against the Charlie Hebdo caricatures of the prophet Mohammed in 2006 (cost 150 lives), 2011, 2012, and the shooting of employees (12 deaths and 11 injured) in 2015. In this case, graphic humor was supported (through demonstrations and subscriptions) by several millions of freethinking westerners educated in democracy, or rejected as offensive by several millions of worshippers in theocracy, and zealots ready to launch massive demonstrations and hullabaloos.

Transgressor mechanism is the expression used by

Álvarez-Junco (

2016, p. 217) in his book that summarizes years of university teaching, research, and creativity. “Humor always makes us incorrect and transgressors, available and accomplices with others. Incorrect and transgressors because with humor, we enjoy attacking not only the social forms that have been imposed and constricted on us, but also other forms that are acceptable to us and even cherished”.

Here are two examples with a religious background that may clarify the intention, especially drafted for this article.

A prophet is a cultural form specific of three religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In the Jewish tradition, a prophet was a troublemaker, that is, a person with the gift of the gab (navi, in Hebrew), and, at the same time, a clairvoyant (choze, in Hebrew). The central premonition of thirteen out of sixteen prophets (mentioned in the Bible) was the destruction of the Hebrew temple, and only in three of these, the omen was restoration. The number of female prophets fluctuates (from none to 3, to 5 and 7 or 8) to the best of the ability and sensibility of the rabbi. Jesus, the Christ, was the prophet added by Christianity to the list: his mindset, also, was apocalyptic. In a similar vein, Islam introduced Mohammed as the final and definitive prophet in the list. In other religions, such as Buddhism, Taoism, Shintoism, Confucianism, Hinduism, Sikhism, and Jainism, the notion of prophet is conspicuously absent, and the terms “master”, “guru”, “teacher” prevail. The distinction between troublemakers and peacemakers makes sense in this topic.

Michelangelo provides many good examples of sense of humor in the Sistine Chapel frescos, in the exact room where the Popes are elected in the Vatican State.

For instance, on the wall above the main entrance door, the prophet Zechariah appears with the face of Julius II, nicknamed the Warrior Pope, below his coat of arms (

Figure 4). At first glance, it was an honor intended to feed his self-esteem. Himself and his successors, and future visitors would know his face, decade after decade, in the role of sponsor, and his Papacy duly identified, centuries ahead, through his coat.

However, only those with some expertise in Jewish prophecies may read between lines, and find the concealed intention of Michelangelo. The target in Zechariah’s voice was the imperativeness of rebuilding the temple, and of worshiping Yahweh as sanctioned in Israel. But there is a second hint behind the nape of the prophet: two friendly children reading his book over his shoulder, or maybe two mischievous kids, because in their eloquent and visible fist, the thumb appears inserted between the fore and middle fingers. This gesture in Mediterranean countries is known as the figure. The middle finger is the expression in other languages (

Blech and Doliner 2009). Revenge?

Álvarez-Junco (

2016) introduced nuances in what is meant by transgression in graphic humor, “visual tasks accessible to a cautious group of makers with strong expressive doses and fluid knowledge on the conception of an image” (p. 18).

Again, the hilarious example has been provided by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel ceiling. In the section devoted to the creation of the sun, the moon, and plants, on the right side, the classical figure of God springs up in the role of father with a long and grey beard. On the left side, God’s nape of the neck appears, as well as the soles of his feet, and his bare buttocks (juvenile?) through a gap in his purple robes. In other words, the rear end of the Absolute Being (

Figure 5).

During the restoration of the Sistine Chapel, a postage stamp for 350 lira was issued on the 8th April 1994 by the Vatican City to be circulated among philatelists, as well as through the post office. No negative reactions were reported by mass media. Mainly smiles when this miniature was introduced, an elucidation of churchly graphic humor.

Álvarez-Junco (

2016) insisted on what transgression in graphic humor means: “the unreal and fantastical world where we have been transferred, nullifying temporarily our usual mental system, establishing his own kingdom, where normal rules don’t exist but to be mocked” (p. 31).

Four-hundred and eighty years had elapsed, that is, 48 Popes, a large number of cardinals, bishops, Swiss guards, journalists, Italians, millions of tourists, yet none of them realized what was before their eyes. Again Michelangelo, again in the Sistine Chapel Frescos (

Figure 6).

The clever person was a 43-year-old practicing physician, specialized in obstetrics and gynecology. As a tourist and an educated person in the history of art, he carefully examined the section devoted to the creation of Adam, and realized that there was an encoded message. The vast majority of visitors, Western Art historians, and priests perceive that the already alive Adam, without touch, receives a bonus from God, the transcendental and creative genesis (

Meshberger 1990).

However, there is a third matching character in the fresco: the neuroanatomy of the brain as understood by Michelangelo, and printed in medical illustrations of the anatomy and pathology of the nervous system (

Netter 1983). What is the mysterious connection?

It was forbidden by civil and ecclesiastical laws to perform dissections of corpses with the purpose of knowing in detail the supporting framework of their anatomy. The access to temples and monasteries required a special permit, but alas! often there were silent agreements, in cellars, to use graveyards and obtain flayed dead bodies. Michelangelo conserved manuscripts of what he learned in Florence. In the reddish cloak surrounding God, the flowing green robe at the base embodies the vertebral artery, the cherub’s knees bring up the shape of the optic chiasm, the back of the angel, below God, the pons, the angel’s hip and leg the spinal cord. Further details and outlines can be seen in

Meshberger (

1990). The similarities are eloquent.

It is striking that in this fresco, which illustrates a social and sacred interaction, just the moment in which Adam was filled with the breath of life, his face expresses not enjoyment or surprise, nor zest for life, and bound and determined is the Creator’s visage: a blank stare in His eyes.

Again, in the Sistine Chapel section that illustrates the separation of light and darkness,

Suk and Tamargo (

2010) detected a ventral view of the brain stem, eyes, and optic nerve, as seen from below, directly above the altar (

Figure 7).

Michelangelo was playing and teasingly advising: it is forbidden, and you do not know yet (late 15th century) what is it that I know. Investigating with corpses he advanced what is known as neuroanatomy, centuries before it grew into a scientific discipline.

Álvarez-Junco (

2016) pointed the nexus between transgression and connivance. “The humorist’s mission is to create a framework that is shared with the spectator, getting him or her involved. The proposed game requires complicity. Both, author and spectator, should reflect, criticize or have fun together. The author should outline the proposal, facilitate it and make it intelligible, effectively enforced with an obligatory purpose: the comic efficacy” (p. 369).

Again Michelangelo, but this time with the Pietà, which can be visited in Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican (

Figure 8). It is a sculpture of a woman cradling the body of a man. If the man is Jesus after crucifixion, his age must be 30–33 years old, and thus, his countenance and body frame. However, the woman’s visage is younger, still a teenager, with the startling smoothness of her skin in marble.

There are two known classical interpretations, one attributed to ecclesial authorities: ageless is the Mother of God. The other view is the unrestricted viewpoint of Michelangelo: chaste virgins retain their beauty longer (

Blech and Doliner 2009). Did he nurture another restricted and secret standpoint?

In 2001, a 30 cm-high model in terracotta of the Pietà (

Figure 9) was submitted to the restoration of an expert, Loredana di Marzio: she detected great anatomical finesse. There was a woman, a man, and a cupid (only a torso, wings, quiver with arrows, and one arm that holds the hand of the deceased), next to the woman. The size of this terracotta was similar to others authored or attributed to Michelangelo and other sculptors of that century in Florence. Successive layers of painting were eliminated in the cleanup process.

In an inventory of properties in Bolonia (in a well-known family in the 16th century), this model in white argyle was mentioned as authored by Michelangelo, and it was venerated in a private chapel in 1581. It also appears in an oil painting by Annibale Carracci in 1599 that includes two cupids (

Crescentini 2019).

Jean de Bilhères (1434–1499), known as the cardinal of Saint Denis, commissioned the Pietá as soon as he saw the terracotta model. He was surprised by the quality, newness in the disposition of bodies, and the unprecedented dramatic perspective, far away from Roman canonical standards.

Carracci admired Michelangelo’s Pietà, as, a century later, he sketched three variations, and the final oil painting was venerated in a chapel (

Figure 10).

Michelangelo was educated and trained in Florence, under the protection of the Medici’s family. An open-minded cultural climate prevailed because invited guests and denizens from different religious traditions and schools spent some time teaching and copying and bringing into existence in the classrooms.

Just the opposite was the climate in Rome and the Vatican, both under control of the Pope and Cardinals. For instance, rabbinic talks and books were available in Florence, but not under the Pope’ jurisdiction and safeguard. Only buttoned-down knowledge and orthodox interpretations were welcome in Rome. The rabbi’s erudition and practices were rebuffed as Old Testament, and indicted as heretic before the inquisitorial court. That is, spontaneity and sense of humor were lost during the fault-finding scrutiny.

Were Michelangelo and the Cardinal of Saint Denis accomplices in the order commissioned in 1498? He was a Benedictine abbot, royal counselor, and ambassador. That is, a plenipotentiary delegate regarding power. He knew what he was doing in the selection process of this pupil sculptor, educated and trained under the Medici’s umbrella. The donation he paid was intended for the chapel of the King of France in Saint Peter’s Basilica. It was a diplomatic present of peace after the four years known as the Italian War that took place between 1494–1498.

There is another detail: the woman’s legs are open, and the man’s pelvis covers the space left (

Figure 11).

Scissoring sex is a metaphor used by Renaissance painters and sculptors to suggest that both (real or legendary) characters are lovers (

Santesso 1999). The legs of each one emulate the blades of scissors. There are three preparatory drawings by Carraci, and only one is catalogued in the Royal Collection of Windsor Castle, and the other two in a private collection (

Figure 12). The first one in

Figure 12 left, emphasizes the cross-legged posture as it appears in the Vatican’s Pietà. In the drawing in the middle, the head is placed on the tomb, and the drawing on the right is similar to the oil painting: the head and shoulder blades rest in the woman’s lap, but not the legs.

Michelangelo and Carracci were aware of the risks in the game they were playing. And

Álvarez-Junco (

2016) pointed out that new meanings are proclaimed as improvements, when, in fact, transgressions have been intended and reconsidered for camouflage. “Graphic humor precises the elaboration of a careful configuration that includes the conjunction ‘

contextualization + transgression’, that is, a perfect visual communication of the form-concept game. The goal of humor is to share the comic find. The extravagance of the piece must succeed in associating with the proposal of the humorist the joy of the receiver” (p. 37).

4.2. Graphic Humor and Transgression in Buddhist Fine Arts: No Camouflage

The Giant Reclining Buddha (

Figure 13) that is venerated in the Chaukhtatgyi Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar, supplies the counterpart. It is a common motif, an exquisite large statue, ranging from 10 to 182 m in old (2nd century) or 20th century temples in, at least, twelve Asian countries, as well as in the United States.

It is a counterpart because Buddha is dying of dysentery, surrounded by disciples, serene face, eyes gazing down, and cheeks smiling kindly. He reached the age of 80.

The one in Yangon exhibits bright red lips, white skin, and pink toenails. The head rests, forming a straight angle from wrist to elbow. It has an androgynous look (male or female?), with the cutis firm and soft (juvenile?). Worshippers sit down on the floor, enclosing the corpse that seems to be happy. Neither tears nor torture pop up. He does not seem to be bloodless.

This is the message: dying is the final ecstasy, the aftereffect of having lived well. Nothing to do with the idea of Pietá, a painful mother or sweetheart conspicuously absent. Dying is not the consequence of an original sin, fuzzily collective for having eaten a forbidden apple (or a fig, as Michelangelo painted in the Adam and Eve fresco in the Sistine Chapel). They sewed fig-leaves together because they felt naked, this is what Michelangelo and scholars used to read from the original text in Hebrew mentioned in their gatherings.

In fact, the resurrection, not the crucifixion, is the critical miracle, the challenging epiphany in Christianity. Lutheran ministers carry the cross on their chest, but Catholic priests add the dying man, a significant difference. From a psychological point of view, the insistence on the Good Friday eternal memento introduces a violent image and symbol into schools, for instance. That is, a tragic scenario with a man of sorrows, and the outcome is anticipated negative humor regarding death. The alternative, resurrection, as a gospel revelation, is set in scenario full of life, it is scheduled when spring begins, and thus, positive humor is the desired sequel. In rural settings, spring is the season of reproduction and breeding.

A day of meditation, or a social encounter to exchange food or to remember relatives or friends who have recently died is the main activity in some Asian countries to commemorate the passing away of Buddha (Parinirvana Day) (

Figure 14). It is the occasion of mulling over the aftermath of attaining enlightenment in this life. It takes place annually, either on the 8th or 15th of February: still winter in the northern hemisphere.

Believers are not crying around. They are pious partners and devotees, and the palette used by the graphic designer is multicolor. Orange prevails, and so many orange brushstrokes (from bright yellow to deep red) around him and lighted skulls suggest flames, embers, ashes. It is their clerical clothing, and they are expected to behave honorably. It is a lot more than posing.

5. The Sin of Laughter: Witticism and Religious Interactions, a Taxonomy

Humorous interactions were the research target of

Long and Graesser (

1988), both professors of psychology, specialized in linguistics at that time. They decided to elaborate a taxonomy of humorous interactions in real settings, that is, setting aside jokes. The method used is known as non-participant observation, and so, they observed and analyzed two different television talk shows, “in particular the guest-host interactions would be our source. Audience laughter was used as the measure of amusement. We analyzed 20 “Tonight” and 10 “Phil Donahue” shows for examples of wit. A remark was counted as a witticism if it was a statement that occurred during a guest-host interaction and the audience laughed” (p. 41).

The key aspect in their taxonomy of wit is to narrow down the speaker intention, paying attention to style, which is very personal. Monologues were considered jokes, and thus, discarded. Their categories are used as framework and examples, with a religious background, searching into literature or graphic art.

What makes this section special is that examples from literary sources of non-English writers and caricaturists are taken into consideration. For instance, Catholics knew they would get into trouble if they expressed directly what they thought. Penalties were prescriptive if the religious authority was informed. So, they strived primarily to conceal their intentions, and used humor to mimic. Contemporary readers smiled somehow, but two or three centuries later, unrepressed readers laughed. Others, such as Buddhists or Taoists, were not so concerned because religious penalties were of a descriptive nature. For instance, under the jurisdiction of the Dalai Lama, specific moral measures for practitioners or monks are not intimidating, they are just symptomatic.

Each of the eleven categories are depicted with prototypical examples requiring a religious context and cultural background. Interested readers may delve deeper into more advance aspects via online search engines. It is convenient to verify the degree of credibility of the source.

5.1. Irony

In Spain, there is a long tradition of processions, even in the 21st century, and mainly during the Holy Week, some silent and austere (largely in the central region known as Castile), others vivacious and luxurious (mainly in the South, Andalusia). In big cities, it has become, predominantly, an international trademark, that is, quality controls on what is done, because a lot is at stake that concerns the local economic activity (under the umbrella of tourism in the city hall) and only, indirectly, under the supervision of the bishop or the cathedral.

“The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha” is the main contribution of Spanish literature to Western culture, at least. The first part was published in 1605, and the second, ten years later, just the year before the death of the author, Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616), considered the first European pioneering novelist. The main characters, Don Quixote (a knight-errant, that is, a visionary) and Sancho Panza (his squire, a down to earth stubborn man) were featured in masquerades held the year the book was published and, what a coincidence, on Good Friday, because, just that day, the first-begotten son of the Spanish King was born, the successor. Celebrations took place in the streets, and the church bells rang.

In part 1, chapter 19, a procession is described. Night had fallen, and Don Quixote and Sancho came upon an array of lights that were approaching. At first glance, they believed that what they saw were ghosts: twenty-six males chanting in white, with torches on horseback, muttering in a plaintive tone. A litter in black followed them. In the bier, they carried the corpse of a man who died not far away, was buried, and had been exhumed to be reburied in another site. In the exchange of questions and answers, Don Quixote got angry and reacted with violence, and the mourners fled into the fields shouting that he was the Devil incarnated, and Don Quixote proclaimed, at the same time, that they were the “very devils of hell” because it was not a corpse, but a badly wounded knight that needed to be helped, both to recover and to take revenge.

Every Easter Saturday, similar processions take place in cities and towns, and the Spanish version paves the way to ceremonial similarities with the Man of Sorrows, that is, Jesus in the gospels: he died in the Golgotha, and was buried nearby in a borrowed sepulcher. At the crack of dawn on Sunday, Mary Magdalene went to take care and carry out the inhumation that was cut short. “Dead or badly injured” is a discussion launched when the Greek versions of gospels started to circulate, and there is animosity about what is meant by resurrection.

“Cervantes seems to be suggesting that there is no inherent difference between a religious procession and a vision of hell”. This is a scandalous proposition in the repressive environment of 1600, possible only to someone nurtured on Erasmus and his distaste for processions (

Johnson 1990, p. 13).

In fact, there is another procession described in chapter 52 (first part), and the aim is that the public rain prayers on behalf of the Immaculate Holy Virgin, her statue carried on wings by penitents. Don Quixote fantasized that she was an abducted Lady, and decided that he was the right knight to set the Lady free.

In both chapters, the mockery (Homo Risibilis) was that he was a madman, and given the circumstances, he could not know what was going on. For instance, during the Covid 19 pandemic (that is, 2020 and 2021), the tradition of organizing (with rain or shine) a procession from church A to B, with the statue of the Holy Virgin being carried out on shoulders, took place to ask for her mediation before God.

There is also irony in the way he was singled out, suggestively, by his squire as the “Knight of the Sad Figure”. It is another nickname for depression or melancholy after repeated failures.

In the procession described in chapter 52, the Holy Virgin is honored because “she was free from all stain”, as the text emphasizes. In 1604, the king Philip III made it mandatory in Spanish universities to swear that one firmly believed and endorsed such a dogma. Don Quixote was published in 1605. Thus, Cervantes knew what was at stake if it was detected that he was bantering with this notion with no basis in the New Testament, and not endorsed by Christian Orthodox Churches. This oath was de rigueur until the early 20th century. Both the ceremony and precise wording were included in the article 212 of the regulation of the kingdom’s universities sanctioned by the Queen Elizabeth II, dated 22nd May 1859.

In the background, there was also a conflict that may be explored with emotional distance and sense of humor (

Arias 2005). There were those insisting that the correct portrait of Mary, the mother of Jesus, must include a child in her hands, and she must be sitting down in a chair or throne. This view became popular among Catholics because it was the version endorsed mainly by the Dominican preachers, both here and abroad. There is an iconographic continuity with the Egyptian cult to Isis nursing the child Horus. In contrast, the Franciscan preachers argued that it must be a woman without child because she was Virgin and immaculate, and thus, she is represented standing and flying weightless over angels, moon, stars, and heavens. The iconography looks like a graceful drift from some elegantly dressed sculptures of Venus and Aphrodite. The Immaculate version achieved recognition in the Spanish mythology and folklore; thus, this iconography was included in the biography of Don Quixote, both beings, being fantasy, are not of this world. The Christian Orthodox Church have not endorsed the dogma of an Immaculate Conception, thus, not such iconography (

Figure 15).

5.2. Satire

Toba Sojo (1053–1140) was a Japanese painter that started as a Buddhist monk, followed as a high priest, and ended as Head Priest of the Tendai School in Japan. He enjoyed the advantages of community living, which boosted as his status increased gradually. Many of his life needs and affairs were settled collegially, and the privilege of one or more appointments of young assistants as pupils, who were motivated to do their best and learn under his direct supervision, in charge also of their spiritual progress; that is, above average in the quality-of-life standards of a beginner or a professional cartoonist.

A direct consequence of this was a set of four horizontal scroll paintings, the largest being 11 m long and 30cm wide, which contained only drawings in dark ink, no words at all. This antecedent of manga shows a religious park where a large number of anthropomorphic creatures, such as rabbits, foxes, frogs, monkeys, and other animals, fool around impersonating Buddhist priests, monks, and parishioners in a large variety of ceremonies.

Choju-giga (

Frolicking Animals) is the abbreviated tittle (

Figure 16). In the Western terminology, these are caricatures. Esoteric practices play a far-reaching role in initiations programs based on secret and undefined methods towards enlightenment.

On the left-hand side, an ape dressed as priest (his robe messed up) on his knees is praying to a grandiose frog that is a Buddha in full lotus posture with giant elephant ear leaves. In fact, this a pastiche of Buddha making the teaching gesture with his right hand, and honored by the sacred cobra. Behind them, there is a fox and a rabbit reading or reciting scriptures, again, dressed as second level priests.

“What are we to make of this apparent sacrilege? Was Priest Toba an idol breaker? Or was this an artful way of telling us not to worship our religious symbols? Don’t treat your religious symbols as if they were the realities they symbolize” (

Holmes and Horioka 1973, p. 96). In the terminology of

Álvarez-Junco (

2016), “humor uses the grotesque and peripheral in order to distance reality and break our barriers (p. 16). In other words, the Buddhist principle of cognitive, emotional, and premeditated detachment of self and honors.

5.3. Sarcasm and Hostility

Religions and money come together because temples, monasteries, and Zen gardens must be built and maintained. Two typical examples are Jesus and Buddha. Jesus was a zealot against the Roman Empire, and became, after the support of Constantine the Great (272–337 CE), the Son of God himself. Similar has been the progression of Siddhartha Shakyamuni: he was not interested at all in succeeding his father as a regional king, and became the Buddha with all kind of honors in the Chinese and Japanese empires, as well as in other kingdoms in Asia, such as Tibet, Thailand, Vietnam, or Korea (

Nakamura and Wiener 1964). In both cases, the evolution from political dissidence (the seed and the root of the movement) and the fertile branches, producing new seeds through cross-fertilization, is precisely a sample of surreptitious sarcasm. From schismatic to rulers or influencers.

Pilgrimage is the typical example that connects business affairs, agendas, and religious ceremonies by persuading those travelers with resources (but also eager to leave their home) to practice the art of discovering spiritual worlds beyond their neighborhood. A typical euphemism is the destination known as “the end of the world”. Idiosyncratic traditions can be found in different continents, but in Europe, Cape Finisterre has been a terminal station, century after century, in the northwest coast of Spain, just above Portugal. In pre-Christian times, the target was having the prerogative of seeing the last sun of the day in Europe. Nothing else far away.

Santiago de Compostela is the name of the city where the shrine of Saint James the Great reveres his human remains. Legendary has been the detail reported in the Acts of Apostles 12:2, where, because Herod the King chose to do so, he died by decapitation in the year 44 CE. Transported by angels to a ship, no rudder, and no sails, without a head, the cadaver was preserved in a cave where it remained forgotten for 800 years. Suddenly, it appeared in 814 CE because a hermit saw stars shinning from the ground, and commented his vision first to the local bishop, and afterwards to the king who ordered to have it buried, without a head, in a small church that was built.

This oral transmission and details have been examined by historians, archeologists, and contemporary information managers, and the outcome is, at least, incredible and, why not, hilarious. Homo Risibilis.

One of the consequences of the mutual support of Constantine the Great and bishops supporting his plans was the existence of dissidents interested in combining Christianity and Asceticism. The pulpiteer insisted on keeping aside the government of the Empire and the government of the Church. His name was Priscillian (340–385), bishop of Avila, and he was a leader of a gnostic and puritanical movement of celibates, known as Priscillianism, that remained strong in Spain, Italy, and France, until their decline after the Council held in Brague in 561 CE, where they were condemned as heretics. The regional emperor Magnus Maximus (335–388CE) ordered the beheading of Priscillian.

Thus, here is the sarcasm. The human remains (venerated with triumphal and annual celebrations, chaired by the King of Spain) are not those of the beheaded apostle James the Elder, nor of James, son of Alfeo (

Serrulla 2021). The alternative option is those of the beheaded Priscillian, that is, the heretic (

Chao 1999).

If you ask the tour guide “who is buried here” with malice, the polite answer often is “we may comment on this in the bus, but not in this cathedral”. The standard answer is “the Apostle” if you persist.

In the database of the National Institute of Statistics in Spain, the number of citizens whose name is Prisciliano was 99 men and 24 women in 2021, and their average age was 72-year-old. This name is conspicuously absent in Compostela and surrounding areas, but it appears in regions where Priscillianism was relevant fifteen centuries ago. When these persons were baptized in Spain, during the dictatorship of Franco (1939–1975), priests could reject this name as heretic, but did not. The wise eye and the hand that signed the baptismal certificate were of sage and educated churchmen, also the witnesses.

In relation to hostility the surah 49: 11 in the Quran has a clear preventive advice: O you who have believed, let not a people ridicule [another] people; perhaps they may be better than them; nor let women ridicule [other] women; perhaps they may be better than them. And do not insult one another and do not call each other by [offensive] nicknames. Wretched is the name [i.e., mention] of disobedience after [one’s] faith. And whoever does not repent—then it is those who are the wrongdoers.

In other words, it is mockery that is forbidden in Islam. However, in the six canonical books of hadith, there are about fifty anecdotes of Muhammad deriding or making fun of someone else. For instance, when he answered “no woman will enter the Paradise” to an old woman who asked him to invoke Allah to allow her to access the Paradise. She insisted, and he added, “only youthful and alluring hȗrȋes are welcome there”. She felt mistreated and irritated (Al-Qur’an; 56: 35–37)

5.4. Overstatement and Understatement

A typical case of overstatement is described in the 4th chapter of the first part of Don Quixote. He met a group of merchants and thought they were also errant knights. Riding his horse, he raises the spear, and they are requested, first, to acknowledge and, afterwards, to believe, confess, affirm, swear, and defend, without seeing her, that his imaginary Lady (Dulcinea del Toboso) is the fairest of all women. They say that they are ready to see her, but he makes it clear that they must acknowledge her beauty without seeing her. They were decided to please him even if she was grisly or unattractive. Enraged, feeling aggrieved, Don Quixote attacked one of them. The horse tripped and flipped him off, and the confreres knocked him down and beat him.

Cervantes was smart enough for camouflage because somewhere close by was the Inquisition, but with sense of humor and the art of reading between the lines, this was a parody of the obligatory cult that overstated that a female farmer and villager may be, why not, the Holy Virgin and Holy Mother of God. This is what was demanded from every convert, either Jewish, Muslim, or Protestant, then and three centuries and a half afterwards in Spain. “This is not the language of knight errantry, but of religious conversion and instruction” (

Johnson 1990, p. 12).

At home, Dulcinea’s name was Andolza, a swineherd, and the names of the four brothers (plus two unnamed sisters) of Jesus are mentioned in the New Testament, and Mary was just a countrywoman in Nazareth. Domitilla the Elder, mother of the only emperor deified alive, Domitian (51–96), was never proclaimed as the mother of God, and yet they were born and died in the same century and empire. “The total number of persons who were raised to the rank of Divi during the five centuries from Julius Caesar to Valentinian III was seventy-four, of whom thirtyeight were rulers of the whole or a part of the empire, and sixteen were women” (

Burton 1912, p. 83).

A counterintuitive understatement is the lively dictum of Zen Master Linji YiXuan (IX century), founder of the school named after him: “If you meet a Buddha, kill the Buddha. If you meet a patriarch, kill the patriarch. If you meet an arhat, kill the arhat. If you meet your parents, kill your parents. If you meet your kinfolk, kill your kinfolk. Never be misled by others” (

Watson 1993 p. 52). This wording is connected to the transgression mechanism of humor highlighted by

Álvarez-Junco (

2016), and discussed in the previous section.

At first glance, these statements, besides surprising, are intriguing: is Linji being serious or is he just kidding? His instructions are not politically correct because, watch out, they may lead to murderous actions, which are incompatible with the first Buddhist precept: abstain from killing. However, the remark, “never be misled by others” sounds like an invitation not to be led astray by the tradition, either because it is written in a sutra, it is a recorded saying of a great master, or let us be cautious, it is a holy sculpture or painting, as often these become religious fetishes.

Heavenly visions, sooner or later, vanish: supernatural wonders, sooner or later, deflate. Levitation is not the goal nor the practice. If out of the blue, Buddha in the flesh, comes up to you from beyond, take it easy, you are being deluded, this is dualism, this is not the teaching. Disembodied from oneself, Buddha cannot be recognized. This is not a euphemism; he does not survive elsewhere.

In the Linji Zen School, each of these brief phrases can be savored without choking, and are used as mentoring tools to do the follow up of students. They are known as koan; each sentence in a capsule (

Wenger and Prieto 2007).

5.5. Self-Deprecation

“Only a good man, dressed in black, but not a monk, if he prays on and on” is the typical phrase, often heard when visiting an Orthodox Greek, Serbian, or Russian monastery, for instance, in Mount Athos, a monastic state in the peninsula of Chalkidiki in Greece. There are twenty male monasteries where only men are welcome as pilgrims in the 21st century, ever since the 9th century. Meteora is the Greek region where five nunneries may be visited.

“Pray without ceasing” is the catchphrase reported in the first epistle of Paul to Thessalonians (v. 5, 17), do this all day long and seven days each week, each monk or nun repeats, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, the sinner”. It is their practice; it is their way of appraising themselves with a negative sense of humor. This is more than modesty; it is a psychological method of opening up their minds, and tuning into God via this sacred muttering, or rather, mantra.

The intended outcome is a self-defeating mood that emerges in the context of a detrimental mindset. Homo Risibilis. Jesus Christ is the important one, the center, the omnipresent, and whoever prays, the periphery, in one continuous effort to ingratiate oneself to whoever is the Omni benevolent listener. Self-esteem is smashed deliberately. The mystic outcome is bliss.

From a psychological point of view, dating back to the 4th century, they are blaming themselves for sins that they have not committed. It is a matter of feeling bad, nurturing self-doubt and shame after making a mistake. Jesus Christ, compassionately keeps track. The devotee fractures the sense of self-worth; with zero power, he becomes the Lord’s addict.

A similar formula may be accommodated to the Mother of God (Theotokos eleison), “Mother, have mercy on me” (

Constantelos 1998), and the babyish mood.

5.6. Teasing

Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769) was a Zen Master, Rinzai style, and in his biography, there are several encounters with women ready to test his patience and commitment. Satsujo was a devoted child ready to bow in reverence to the Dharma. Her parents were concerned because she was already sixteen years old, and no suitor had proposed. They asked her to pray to Kannon, the bodhisattva of everlasting compassion and mercy.

So she did, day and night, all day long, saying and doing. It did not take long to have a waking up experience.

One morning, when approaching from behind to see her, her father realized that she was using a printed copy of the Lotus Sutra as a comfortable seating option. “What are you doing with your buttocks on this spiritual scripture?” he asked, and her reply was no less sure of herself: two of a kind, this amazing Sutra, and this amazing ass.

Resolute in her positive sense of humor, melting together what a religious congregation may distinguish as devotional or as profane. “I am reminded of the seamstress Rosa Park’s 1955 act of civil disobedience—simply sitting her tired bottom down on the seat of an Alabama bus and refusing to give up her place to a white man” (

Mansfield-Howlett 2013, p. 254).

The Lotus Sutra was written between 50 CE (seven chapters) to 150 CE (up to 28). Thus, it is wisdom literature of anonymous authorship, like the large majority of religious books of monotheistic creeds. Nicknames of sacrosanct celebrities (of more than one and a half or two thousand years ago), or multilingual angels and alien (their bodies do not have the same time-system).

In monotheistic religions, sacred texts are used in ceremonies in which God is worshiped. Thus, they do not joke lightly. By contrast, what is peculiar in Zen ceremonies is being aware of the inseparability, that is, the continuity of I as subject, the self as object (included what is within the body), and all networked existences.

Thus, the ass and the Sutra, a book that opens and closes like an accordion. It is not buffoonery; it is both a spiritual certitude and a material fact.

Janwillem Van De Wetering, a writer and Zen master in the Netherlands, who passed away in 2008, used a forgotten toy diplodocus as statue to worship in ceremonies with incense sticks. He was not kidding. Homo Risibilis. It was his effort and initiative to make conspicuous by its absence what is experienced as awakening.

5.7. Replies to Rhetorical Questions

During the last quarter of the 20th century, anthologies of female Zen masters in China and Japan, for instance, started to be published, mainly in English, as a direct consequence of nuns trying to connect with female lineages in monasteries. Then, by the 21st century, a draft list of female names circulated, and, afterwards, such a canon on female Zen ancestors were recited at least once a week, initially in the USA.

An enlightened nun was Jigju Ni Miaodao (or Miao-tao), who was the daughter of the Minister of Works first and the Minister of Rites afterwards, appointed by the emperor Son Huizong (1082–1135). So, she was an aristocrat, and thus, an influencer because her father died five years before the emperor. She was a decision-maker woman, and she was not a “rara avis” because a census done in 1021 reported 61,240 nuns (and 397,615 monks).

She started her training under the supervision of a Soto (or Caodong in China) Zen Master, and continued with Danhui Zonggao (1089–1163) from the Rinzai (or Linji) Zen School. She was one of the first to practice with koans, and her master detected and confirmed her awakening using this method. She developed her one style and ruled as abbess several conspicuous convents, one in Wenzhou, that still survives (

Levering 1999, pp. 188–219), but is almost dormant in 2020.

A mosaic of formalities takes place when an abbess (or abbot) takes office (the metaphor is “climbs the mountain seat” because monasteries were built on mountain tops). Processions, offering of fragrances, several statements written for the occasion, a new seat, several documents signed, receiving the Temple Seal, a new patched robe (kesa) sewn by sangha members, her first teaching, and then a question-and-answer exchange between the abbess and disciples, some affectionate and some intricate, and why not, unintelligible. In this context, this somehow drastic exchange took place.

A monk asked: “when words actually explain very little and cannot tune in with the listener, what then?”

Miaodao answered: “you are already falling into the hole; you are at the mercy of a bowel movement”.

Long has been the journey of this question and this answer. Charlatans have no place in the sangha. Deeds give much more of themselves. It is what it is conspicuous by its absence, close-mouthed or muted.

5.8. Clever Replies to Serious Statements