1. Introduction

From 1840, tremendous changes to social patterns began to arise in modern China

1, which had a significant impact on the country’s traditional, old-fashioned education. In 1862, with the deep involvement of Mr. William Alexander Parsons Martin

2, a missionary of the American Presbyterian Church, the Qing government established the Imperial Tungwen College, the first foreign language school in modern China. This school brought in modern natural science courses and became a landmark of modern Chinese education reform.

From the second half of the 19th century, modern Western scientific and cultural knowledge began to enter China through various newly established schools, with an increasing number of missionaries also coming to China to initiate more up-to-date education. By founding Christian schools, translating books of modern science and technology, and introducing Western education, missionaries enabled the Chinese people to become aware of the changes in the world. Christian schools started with preschool education and special education, and gradually developed towards general basic education. Students in Christian schools could only go overseas for higher education, if they wished, after primary and secondary education. With an increasing number of people expected to receive higher education, missionaries began to establish Christian universities to realize their goal of cultivating talents with high degrees.

As early as during the initial period of Christian universities in China (the late 19th century to the early 20th century), Western missionaries were already paying abundant attention to discussing and summarizing their experiences. In 1907, the missionary, Mr. Young John Allen, introduced the founding process and characteristics of the Anglo–Chinese School (in Shanghai) and Soochow University (in Suzhou), as established by the Supervisory Committee, in his article

The History of the Supervisory Committee Founding Universities (included in the Multinational Communique, edited by himself) (

Allen 1907). This article also asserts that China was gradually opening up in its way of thinking and its ethos, and that it was the right time to establish universities to cultivate talent and scientific exploration.

Since the Middle Ages, universities have been generally established in Western society. With the help of missionaries, modern China also established this educational institution which was different from traditional schools. However, during those days, Western universities were no longer satisfied with providing undergraduate education and began to develop graduate education programs. Since the establishment of the Doctor of Philosophy degree at the University of Berlin, graduate education gradually developed in the United States, Britain, Japan, and a few other countries. It is thus necessary to discuss whether Christian universities in China also carried out graduate education in addition to offering undergraduate education during that period of time. According to the information we have collected so far, some Christian universities in China indeed developed graduate education, with representatives of St. John’s University, Aurora University, Soochow University, and the University of Nanking.

It should be noted that unlike national universities, which were under the direct jurisdiction of the government authorities, Christian universities in modern China had a “dual identity”—they had a foreign identity as they were funded and established by Western missionary societies and were registered abroad; however, they also had a Chinese identity since most of them were registered as private universities with the Chinese government during “the China Regaining Educational Right Movement” in the 1920s. Revolving around this topic, some thought-provoking issues include how Christian universities developed new-fashioned graduate education in Modern China, with its strong influence of feudal autocracy, within a relatively short period of time, and whether their academic degree qualifications were approved by the government authorities.

4. The Beginning of Graduate Education at the University of Nanking

At the beginning of the establishment of the University of Nanking, the government had not formulated a degree-granting system for universities, and there were no clear regulations on the registration of private universities. The

Ren Zi Kui Chou Educational System, the first educational system widely adopted across the country after the establishment of the Republic of China, only basically determined the first-level degree of higher education, i.e., the bachelor degree system, and subsequently designed the graduate education institution, i.e., the graduate school. It also put forward the idea of a higher-level degree system compatible with the graduate level of education, that is:

In graduate colleges, … the dean and other professors or hired scholars should be supervisors. There should be no lectures, and the supervisors should be assigned to various fields. At the beginning of a semester, research projects should be put forward, so that students could study them separately and regularly offer speeches and discussions.

Although the university attempted to develop a higher level graduate education, there was no constitution to follow.

During this period, a few other Christian universities had already organized graduate education. A previous study (

Zhu and Gao 1993, pp. 447–50) indicated that the earliest Christian university to make such an attempt in China was St. John’s University, which was before 1908, followed by Aurora University and Soochow University. However,

Yue (

2010a,

2010b) proposed that the earliest Christian university to develop graduate education in China was Aurora University in 1914. The central government included the graduates of Aurora University when they reviewed the candidate list for university diplomas, showing that “the Republic of China government recognized that Aurora University had the same qualification as national universities.” (

Aurora University Twenty-Five Years n.d.). To some extent, this acknowledges the legitimacy of Christian universities. Therefore, when the University of Nanking started to develop its graduate education, there was already a great deal of experience for reference.

In 1911, the board of trustees of the University of Nanking decided to register in New York State, USA. The University of New York approved the ability to award degrees to graduates (

Li 2016a, p. 143), which helped the University of Nanking to further develop graduate education. The University of Nanking Magazine, the publication organized by the University of Nanking, reported:

Since the establishment of our university, there have been many graduates over the years yet without the recognition of American universities. If they were to study in the United States, they would not be allowed to enter schools there. According to the official document decreed by Qu Jun, the Secretary of Education of New York State, and Ma Jun, the president of New York University, on 19 April 1911, our university was officially recognized as a comprehensive university. It says as follows: Since the recognition, the University of Nanking established in China has enjoyed the rights of Western universities. Besides, the diploma certificates that used to be issued by this university are now issued by the board of trustees of New York University and then transferred to the University of Nanking for the graduates. According to this, anyone who graduates from our university in the future is as good as graduating from an American university.

As a result, the University of Nanking (

Figure 2) obtained the right to award degrees by seeking foreign aid, and its graduate degrees were awarded by New York University in the United States. This provided graduates the guarantee of reputation and standard from foreign institutions and facilitated their opportunities to study abroad. The acquisition of the right to award degrees marked the establishment of the University of Nanking’s degree system and laid a good foundation for the subsequent development of its graduate education.

On 15 November 1913, the Chinese Christian Medical Council handed over the “China Oriental Medical University” founded by Dr. R. Shields to the University of Nanking, which became the medical department of the University of Nanking. The university also determined that students needed to study for seven years, and the degree of Doctor of Medicine would be conferred after graduation. The university specially formulated the Guide for Medical Education at the University of Nanking, which clearly stipulates the admission requirements, curriculum settings, and degree awards. Since this was the first Christian university to carry out medical education in China, the curriculum was based on the curriculum requirements of New York University in the United States, and there was also a weekly “Bible” course. However, when the medical education of the University of Nanking was just getting started, the China Medical Missionary Association held a meeting in Shanghai and decided to develop “first-class medical education”. For this reason, in 1917, the Mission Association asked to abandon the medical schools in East China and concentrate on the development of medical schools in Jinan, that is, the Medical Department of Qilu University in the future. Although the medical doctoral education of the University of Nanking had only been implemented for four years, and no medical doctorate had actually been awarded, graduate education at the University of Nanking was started. Medical doctoral education laid the foundation for the development of other professional graduate education at the University of Nanking.

5. The Subject Settings of Graduate Education at the University of Nanking

In the 1920s, Chinese society witnessed a huge revolution

5 and the associated turmoil caused the foreign faculties of the University of Nanking to return to their home countries one after another; indeed, even the principal, Arthur John Bowen, returned to the United States. In November 1927, the University of Nanking Council elected Chen Yuguang (

Figure 3), a Chinese chemist who had a deep connection with the university, as the new president. His first act after taking office was to get the university registered at the Republic of China government in Nanjing (

Wang 2004, p. 205). This was driven by the Chinese nationalist movement in the 1920s, and the University of Nanking took the initiative to follow this trend. A more realistic consideration was that although the University of Nanking had a foreign church background, it had survived in the Chinese context. To further the university’s reputation and the interests of its graduates, the university had to obtain recognition from the Chinese government. With the expansion of its scale, the expenditure required to continue running the university kept increasing, and relying solely on funds provided by foreign missions was no longer sufficient to meet the needs of the university. The Chinese board of directors of the university started to raise their own funding, but still urgently needed support from local Chinese resources. On 20 September 1928, the Republic of China government approved the registration of the University of Nanking, and it became the first Christian university approved by the Republic of China government (

Zheng 1994, p. 204). This determined that the University of Nanking must accept the management of the Chinese government and follow its policies and regulations while accepting the restrictions of the Western missionary societies. However, the Republic of China government, which did not have full authority, was not tough on its management of Christian universities. Instead, this move eased the impact of ordinary people on the Christian university and provided the University of Nanking with a relaxed environment for its development.

After the case was approved and the registration procedure was completed, the subject setting of graduate education became the primary concern of the University of Nanking. According to the fifth regulation of the

University Organization Law promulgated by the government authorities on 26 April 1929, “Anyone with three or more colleges can be called a university”. For this reason, the University of Nanking changed the original liberal arts faculty and sciences faculty into the liberal arts college and the science college, and the agriculture faculty and forestry sciences faculty into the agricultural college in 1930 to meet the requirements of the Chinese government. As noted by Dr. William P.

Fenn (

2005, p. 105), the Commissioner of the United Board for Christian Colleges in China, “One of the main obstacles facing Christian universities in the 1930s is their foreign Characteristics. No matter where these universities are or how eager they are to serve China, they are obviously foreign universities”.

Since the ancient Chinese education tradition emphasized literature and history rather than natural science and technology, and cultivation rather than skills, early Christian universities mostly retained a lot of content related to the ancient Chinese classics, despite their efforts to bring in Western education with natural science as its core. After the Christian universities were established, how to deal with this part of the content became a pressing problem. In the early days of their establishment, most missionaries believed that the advantages of Christian universities lay in their Western education instead of a traditional Chinese education, and that there was no way for them to compete with Chinese self-governed universities in the development of traditional Chinese education. Therefore, some Christian universities either removed this part of education or adopted a perfunctory attitude toward it. Generally speaking, due to the quality of students and market demand, Christian universities in coastal port areas tended to underscore English and professional subjects, while those in inland areas, especially Christian universities with relatively strong religious character, put more emphasis on content related to Chinese language and classics.

However, with the development and growth of Christian universities, it was gradually realized that if Christian higher education were to play a greater role and have a more profound impact on China, it would be necessary to be dedicated to the exchange and integration of Chinese and Western cultures, an inexhaustible source of their prosperity. Only with a better acknowledgement of traditional Chinese education could a deeper understanding of Chinese culture be gained. John Leighton Stuart, the President of Yenching University, once said, “Yenching’s goal is to integrate Chinese and Western knowledge and to adopt the strengths of each in order to benefit more”, and for this reason, “talents must be trained in both Chinese and Western knowledge. … Participation in Western education enables students to obtain extensive training, … and therefore, since the establishment of our university, the courses have been largely about the integration of Chinese and Western cultures in one furnace” (

Yenching News 1935). These accounts indeed represented a well-recognized perspective at that time.

Furthermore, in January 1925, when Luo Bingsheng, the director of the Higher Education Department of the Christian Educational Association in modern China, convened a meeting with leaders of Christian universities to discuss the future of Christian university education in China, the final conclusion was that, “In the future, if Christian universities want to make a significant contribution to China, they should be ‘more sinicized’. In other words, they should not only spread Western civilization but also become centers of Chinese culture. Young men and women of Christian universities should be trained to become outstanding members of the Republic of China with a deep understanding of Chinese culture and its application in their contemporary life, and this responsibility should best be borne by the Chinese people” (

Luo 2016, p. 418). Thus, after the 1920s, many Christian universities began to pay much greater attention to the development of humanities and social sciences and to dedicate themselves to the exchange and integration of Chinese and Western cultures.

As a result, the University of Nanking, according to the requirements of the Chinese government, set up colleges of art, science and agriculture

6 and began to develop graduate education in Chinese culture. Coincidentally, as early as 1914, when Charles Martin Hall, the inventor of the aluminum electrolysis method, died, he stipulated in his will that one-third of his estate must be used for education, part of which should fund some Christian universities in China for research into Chinese culture (

Wang 2018, p. 7). Hence, in 1928, Yenching University and Harvard University reached an agreement to establish the Harvard–Yenching Institute, funded by the Hall Fund, to specialize in Sinology research.

Therefore, when the University of Nanking received this donation in 1930, “it obtained a fund of USD 600,000, of which USD 300,000 was designated for the study of Chinese culture. Our university thus immediately established the Research Institute of Chinese Culture” (

Journal of the University of Nanking 1932). The purpose of this institute was very clear. It must first be consistent with the research direction specified by the fund, and simultaneously be consistent with that of the Harvard–Yenching Institute. In its external declaration, its purpose was stated as follows, “(1) To study and clarify the meaning of Chinese culture; (2) to cultivate talents who are specialized in the study of Chinese culture; (3) to assist our university’s liberal arts school to develop the academic process of studying Chinese culture; (4) to provide convenience for the teachers and students of our university to study Chinese culture” (

General Survey of the Private University of Nanking 1933, p. 40). In a nutshell, the Research Institute of Chinese Culture was dedicated to researching and promoting Chinese culture as well as cultivating professional talents to study Chinese culture.

The establishment of the Research Institute of Chinese Culture provided important conditions for the establishment of graduate education at the University of Nanking. On the one hand, it was a specialized research institution with considerable research strength and appropriate conditions to train advanced research talents; on the other hand, in the early 1930s, there was a surging voice in China to promote the status of Chinese local culture. The East China Christian Church hoped that the University of Nanking would be dedicated to the cultivation of senior talents in Chinese literature and history. At the same time, dozens of the university’s liberal arts graduates also jointly made such requests, hoping to continue their studies at school. Therefore, in 1934, the Faculty of Arts of the University of Nanking established the Sinology Research Class, and invited researchers from the Institute of Chinese Culture to serve as tutors, and recruited graduates from various universities in China who were interested in Chinese studies. The initial school system was two years in length. In research, the students recognized the topics, and the tutors gave guidance. This can be said to be an early example of postgraduate training in various universities in Southeast China (

Zhang 2002, p. 575). In the same year, the Government promulgated the “Interim Organizational Regulations for University Research Institutes”. The second regulation stipulated:

The research institutes are divided into research institutes of literature, science, law, education, agriculture, industry, commerce, and medicine… Before the establishment of the three research institutes, the various scientific research institutes established by the universities may not use the name of the institute.

At the same time, it also clearly pointed out that the function of the institute was “to recruit university graduates to study advanced academic research and to provide faculty members with research convenience”. The promulgation of this law shows that modern China was gradually attaching considerable importance to the development of graduate education, which enabled graduate education to embark on a path of regularization and legalization. It also required church universities registered with the Chinese government to develop graduate education in accordance with the above regulations.

Based on this, the University of Nanking established three graduate training institutions, namely the History Department of the Humanities Research Institute, the Chemistry Department of the Science Research Institute, and the Agricultural Economics Department of the Agricultural Science Research Institute. In 1935, the University of Nanking prepared for the establishment of the History Department and the Department of Chinese Literature of the Research Institute of Liberal Arts on the basis of the program of Chinese studies. In 1936, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China approved the establishment of the History Department of the Research Institute of Liberal Arts (

The Second China Education Yearbook 1948, p. 162). Later, due to the outbreak of the Anti-Japanese War, graduate students were not officially recruited until 1940.

The Department of Chemistry of the Institute of Science and the Department of Agricultural Economics of the Institute of Agricultural Sciences began enrolling students in the fall of 1936. It is particularly worth mentioning that the agricultural sciences courses at the University of Nanking were unique among all church universities. In 1914, the American Presbyterian Mission (North) missionary, Joseph Bailie, awaring that China was a big agricultural country and that many poor people had no food and clothing, noted that, “agriculture and forestry talents are lacking” (

Nanjing University 1989, pp. 18–19). Therefore, he established the Agricultural Science in the University of Nanking. In 1915, Forest Science was created, and in 1916, the two branches of Agriculture and Forestry merged. In September 1936, the Institute of Agricultural Sciences welcomed its first four students, namely Chen Caizhang (supervised by Qiao Qiming, a Chinese professor, Master of Agricultural Economics, Cornell University, USA); Li Huiqian (supervised by Hedland, C.W., an American professor); Shao Dexin (supervised by John Lossing Buck, an American professor); and Xu Zhuanghuai (supervised by L.R. Raebum, a British professor). These postgraduate enrollment and training methods explored the avenue of developing postgraduate education in the University of Nanking in the future.

6. Miner Searle Bates and the Institutionalization of Graduate Education at the University of Nanking

As mentioned above, in 1929, the government of the Republic of China promulgated the “University Organization Law” and the “University Constitution”; however, neither of these two regulated for the training methods for graduate students. It was not until 1934 that the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China issued the “Interim Organizational Regulations for University Research Institutes”, where Article 9 stipulated graduate courses. This was the first time that the specific content of graduate education appeared in government regulations. In 1935, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China promulgated a series of decrees, for instance, “the Degree Awarding Law”, “the Degree Grading Rules” and “the Master Degree Examination Rules”, which provided guidance for the degree course examination, the review of dissertations, and degree awarding. For example, “a person awarded with a bachelor’s degree in accordance with this law, who studied in a public or private university, an independent research institute or a research institute of an independent college for more than two years and passed the examination of the institution could become a proposed candidate for master’s degree. Master candidates who passed the examination and was reviewed by the Ministry of Education should be awarded with a master’s degree by a university or an independent college. … Candidates for master’s or doctorate degrees must submit research papers” (

Ministry of Education of the Republic of China 1936, p. 129). As a result, a holistic graduate degree system, designed at the national level, was gradually formed. This meant that the graduate education activities of the University of Nanking needed to be carried out within the scope prescribed by the government. However, since the government had only determined rather basic frameworks for such, the specific operations were implemented by each college according to its own circumstances. Hence, the University of Nanking still retained considerable autonomy in the design of their graduate education system. From 1920 to 1950, Miner Searle Bates (

Figure 4), who worked at the University of Nanking for 30 years, made a significant contribution to the institutionalization of postgraduate training at the University of Nanking. In the summer of the same year, he returned to the United States and voluntarily accepted the church dispatch to work at the University of Nanking in China (

Ma et al. 2014, p. 1).

Since Bates had received a good higher education abroad, studied modern history in depth, and traveled to the European continent, the Near East, and India, he had a broad vision and knowledge as a missionary of the United Christian Missionary Society Disciples of Christ. He later became a professor and director of the History Department. Due to his good training in history and long-term, in-depth research on Chinese history and culture, he was able to provide detailed considerations and arrangements for the training goals, curricula, and teaching plans for talents in Chinese history and culture at the University of Nanking. He not only brought new knowledge of humanities and social sciences to the university but also new educational ideas and school-running styles to graduate student training.

In terms of enrollment for graduate students, those who took the graduate entrance examination had to be graduates of national universities, provincial universities, private universities registered by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China, or independent colleges, and their graduation scores had to be above average. The graduate entrance examination was divided into written and oral parts. The subjects of the written examination included Chinese, foreign languages, and professional knowledge. For example, the entrance examination subjects of the History Department of the Research Institute of the Humanities were Chinese, Chinese History, Western History, and English. In addition to the written test, applicants were also required to take an oral test in order to further assess their abilities and qualities.

The method of cultivation of graduate students reflected the distinctive feature of combining teaching and academic research. Taking the History Department as an example, the courses were divided into two parts, coursework study and research work, with 20 credits for each part. If a graduate student wanted to obtain a master’s degree, the research time must not be less than two academic years, with 40 credits obtained in total and one thesis completed. Specifically, the curricula for graduate students were divided into two types: foundational courses and specialized courses. Foundational courses were compulsory for graduate students of the department and principally about collection and identification of historical knowledge, historical methods, and historical materials. Specialized courses were divided into five following categories: Chinese history, history of Chinese ideas and culture, archaeology and Oriental antiquities research, Oriental history, and Western history. Graduate students needed to choose one of the five categories as their major field (

Nanjing University Press 2002, p. 232). In terms of historical research, graduate students needed to propose a research plan within the first semester after enrollment. After the approval of the Ministerial Committee, they needed to do their research under the supervision and guidance of the director of the department or the designated professor. The research procedures were divided into the following two stages: to assist the professor’s research work through method training with a total of 40 credits, and to do relatively independent research yet still under the supervision and guidance of the professor, with a total of 16 credits. The research achievements should be compiled into a written report at the end of each semester to facilitate the review of their grades. Research independently completed by graduate students should be presented in a research paper. Meanwhile, the academic performance of graduate students for each course must be above average, otherwise no credit would be obtained.

When the Department of History was established, researchers from the Institute of Chinese Culture served as tutors and offered courses, such as “Shang Dynasty Cultural History” and “Chinese Archaeology” led by Shang Chengzuo, “General History of China” led by Chen Dengyuan, and “Chinese Grammar” and “Introduction to Linguistics” led by Lu Shuxiang. When the China–Japan War broke out and moved westward, the Department of History began to officially recruit graduate students. The School of Liberal Arts entrusted the Institute of Chinese Culture to assist in matters related to the Department of History of the Institute of Liberal Arts. In addition to the meticulous guidance given by the on-campus researchers, in order to expand the horizons of graduate students and improve the level of research, Jinling University invited Chen Yinke, Meng Wentong, Qian Binsi, Xu Zhongshu, Ding Shan and other well-known scholars to act as tutors for graduate students.

In terms of degree awarding, in addition to achieving the required credits, strict procedures, including completing master’s degree thesis, obtaining approval from external experts, and passing degree examinations also had to be performed before a degree could be awarded (

Zhang 2005, p. 155).

Again, taking the Department of History as an example, a total of four graduate students were trained, namely Tang Dingyu, Zhang Jiping, Liu Jun, and Cheng Tianfu (see

Table 1 for details). Among them, Cheng Tianfu was a female graduate student, which was very rare in China at that time. Although the History Department of the Liberal Arts Institute moved westward with the school soon after its establishment, and was in the midst of war, it still insisted on recruiting graduate students and cultivating historians in such a difficult and turbulent period. After graduation, some of these graduates taught in the history departments of domestic universities, and some went abroad to continue their studies, making contributions to the study of Chinese history and culture and realizing the original intention of the University of Nanking (

Figure 5) to open up graduate students in Chinese history and culture.

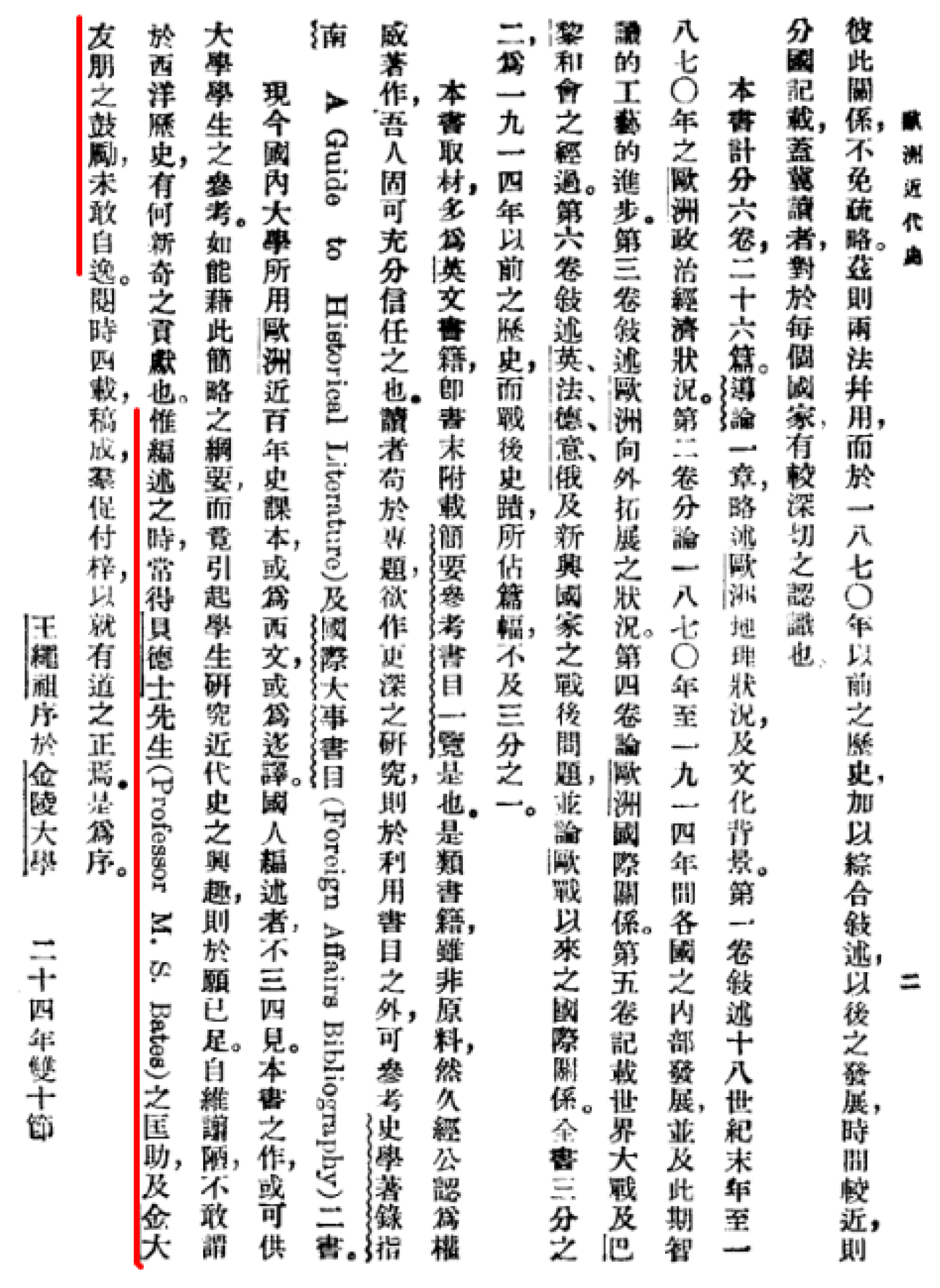

It can be seen from these regulations that the University of Nanking was strict with graduate student training. Wang Shengzu, a historian of international relationships, and Chen Gonglu, the modern historian who graduated from Nanking, had a significant influence on Chinese academic circles. On the front pages of the books that they edited, i.e.,

Modern History of Europe and

Modern History of China, published by the Commercial Press as the “University Series”, the line “Dedicated to Professor Bates” is written to thank him for his cultivation (

Figure 6). It can be seen that Bates has a great influence not only on the Department of History, but also on the postgraduate training of the entire university. “Although he was only the head of the history department and also served as the deputy dean for a period of time, owing to his prestige, he has made great contributions to the entire university” (

Guo 1982, p. 50).

After the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China government promulgated the “Interim Organizational Regulations for University Research Institutes”, the University of Nanking used it as a basis to develop graduate education in medicine and agronomy to meet the needs for talents in social and economic development at the time. It cultivated a batch of high-level specialists for China in the first half of the 20th century. As of 1952, the number of graduates from the University of Nanking totaled 4475, including 26 postgraduates (

Zhang 2002, p. 586). Although these numbers were not large, these students achieved excellent results after their graduate education.

7. Conclusions

From the discussion above, we can see that the University of Nanking was not only the first Christian university registered by the Republic of China but also the first Christian university to initiate graduate education in southeastern China. Numerous missionaries, including Miner Searle Bates, who taught at the University of Nanking contributed to the dissemination of Western scientific knowledge and the promotion of cultural exchange between China and the West, and they also cultivated a multitude of outstanding talents for modern China.

As a university founded by American churches, the University of Nanking consciously or unconsciously applied some basic concepts, educational systems, and teaching methods of modern Western education in its own school-running practice, which led to various aspects of its construction and development reflecting the characteristics of Western education. It should be noted that there must be conflicts and integration as well as rejection and acceptance in the exchange of heterogeneous cultures. On the basis of their own religious characteristics, Christian universities also had a tendency to gradually strengthen their understanding and absorption of Chinese culture, and they ultimately promoted the integration of Chinese and Western cultures and highlighted their function of cultivating high-level specialized talents. As said by Dr. William P. Fenn:

The important contribution of Christian Universities in China is to enhance mutual understanding and friendship between countries. Through the language, knowledge, value and foreign faculty provided by the university, it has brought in the best from the West. At the same time, through these, Chinese knowledge was translated, demonstrated and introduced to the West.

Therefore, Christian universities made a certain contribution to the research of traditional Chinese culture and the cultivation of high-level talents. For many reasons, Christian schools were willing to strengthen their research power in Chinese studies and even to become first-class institutions in this area. They kept exploring how to improve the research and teaching methods of Chinese education in ways unique to Western education. For instance, although the University of Nanking “was founded by some churches and church members with their original plans of religious education, religious activities and religious courses; however, these church members who established the University of Nanking were mostly ‘enlightened’. Although they did carry out religious propaganda to students, they did not take compulsory measures but rather paid more attention to the establishment of modern education. From the very beginning, the University of Nanking underscored the ‘integration of Chinese and Western cultures’ as its principle. While focusing on Western education, it also paid attention to Chinese education and implemented an ‘enlightened’ school-running mode” (

Zhang 2002, p. 2).

On the basis of strengthening the study of Chinese culture, the graduate education offered by Christian universities became an integral part of the development of higher education in modern China, providing useful experience for the development of graduate education in the country. The procedures of enrollment, courses, research, and degree awarding for graduate students at the University of Nanking not just followed the cultivation rule of “combining teaching and scientific research” but were also guaranteed by rigid system design. Therefore, its postgraduate training enjoyed a high reputation, both domestic and abroad. According to the U.S. standard ABC classification of universities established by foreigners in modern China, the University of Nanking was the only Class A university. In this evaluation offered by the University of California in 1928, Yenching University was only in Class B, and Soochow University and St. John’s University were in Class C. According to this standard, graduates with a university degree in Class A universities were eligible to directly enter the graduate school of an American university, and graduates with university degrees in Classes B and C could only enter undergraduate degree programs in the United States. Some of them could enter the third or fourth year, but others could only enter the second year of an undergraduate degree program, and 30 undergraduate credits were required to enter a graduate school (

Li 2016b, p. 42).

In short, on the one hand, the Christian university symbolizes the cultural invasion of China by imperialism; on the other hand, it promotes the development of modern Chinese education to a certain extent. Although the wheel of history has since turned, the role played by Christian universities at the beginning of graduate education in modern China is remarkable and deserves further research and discussion.