Abstract

Although religious belief represents the main reason people belong or do not belong to a specific church or religious society, it is not always the only reason, and increasingly there are other factors that affect this belonging. These factors include the attitude toward institutionalized religion, and a preference for the value of belongingness plays an important role as well. Both of these factors are also influenced by the wider context of personal attitudes to morality and solidarity. In our research, we assumed that the value of belongingness is a cornerstone that, in specific ways, binds all the other mentioned factors, and is likewise related to religious belief. To confirm this assumption, we conducted research using a widespread cross-sectional survey. In total, we received data from 5175 respondents (2204 men, 2957 women, and 16 of another gender). The data were collected in the Czech Republic, which can be considered a country with a wide spectrum of different religious beliefs. All hypothetical assumptions were confirmed as statistically significant, and the analysis of the inner structure of these relationships showed their complexity. Because of the high complexity of the examined phenomena, only the main findings are discussed in this paper. Our conclusions confirm the increasing number of people for whom belonging is more important or takes precedence over religious belief. These conclusions led us to several recommendations for religious institutions or societies.

1. Introduction

Social connections and membership in social groups have always played an important role among humans. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when most people are socially isolated, social connections seem to be more important than ever before. Specific sets of individual skills considered as the drivers for belonging before and during the pandemic have changed (Eatough 2021), and the situation has proven to be similar with religion as well. According to the Pew Research Center (2021), the faith of some people in 14 surveyed countries has even strengthened due to this pandemic. The Czech Republic is traditionally considered an atheistic country. In 2017, a survey among 15 European countries demonstrated that the Czech Republic has the highest percentage of religiously unaffiliated people of all the surveyed countries (Evans 2017). However, we believe that the results may in fact be different when based on those who identified themselves as “religiously unaffiliated”, and the sensitivity of the distinction of “religious belief”. For example, there is a major difference between atheists, agnostics and “ietsists” (those who believe in “something above us”). The fact that one does not believe in God does not mean that one cannot be spiritual. On the other hand, attitudes toward institutionalized religion even affect believers, and it is not rare that some of them decide to leave institutionalized religion for various reasons.

We assume that the reason to belong to a church or religious society does not rely only on the present time or religious belief, but that there are multiple factors influencing people to join or remain in a religious community. Among these factors, we emphasize the individual’s value system, source of moral judgements, and prosocial attitudes. As we learned in our previous research (Pospíšil et al. 2016), faith, religion, ethical attitudes and sense of solidarity are significantly influenced by social factors. Nevertheless, we recognize that the inner relationships among them are complex and should be researched in greater detail. The aim of our article is to focus on the value of belongingness and examine the connections between a preference for the value of belonging and religious belief, institutionalized religion, sources of moral judgements and solidarity, as these relationships have not been explored before. We expect that our research will fill a research gap and bring new knowledge into this little-explored research area.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Values, Attitudes and Needs

The concept of “value” has been discussed in philosophy, theology, psychology, and other social sciences for over one hundred and fifty years. We consider the thesis, formulated for the first time by philosopher Hermann Lotze (1856), that values in a human’s life are the key to solving ethical decisions, as well as to the building and understanding of culture, which is still valid. Values are an important part of an individual’s personality and play a key role in the way of thinking and behaving (Schwartz and Bilsky 1987, 1990; Inglehart 1997). They are a normative and formative factor in the creation of moral judgments (Rokeach 1973), and they also significantly influence attitudes towards religious beliefs (Krok 2015; Chan et al. 2020), institutionalized religions and society. We can imagine values as enduring inner beliefs about ways of acting or a target state of being (Rokeach 1968); they are not constant, but are formed throughout our lives and change with varying intensity at different times. The formation and transformation of values is therefore a continuous and lifelong process. The value system of each individual is unique and depends on family upbringing, social environment, culture, and religious belief. Only values whose eventual change is a long-term process can become part of the value orientation of the personality. The value system also serves as a tool for general recognition, conflict resolution and decision-making (Rokeach 1973, 1968).

Attitude can be described as an evaluative relationship of individuals, which involves the disposition to behave or react in a certain relatively stable way. Values and attitudes are not the same, because value refers to an object, and attitude—how one reacts to that object. While value is expressed by attitude, attitudes are a broader concept than values (Rokeach 1968). Attitudes are mainly developed through personal experiences. Our past experiences influence our future behavior and final decisions through values, which, as core ideas about the importance and worth of things or objects, have an impact on whether our attitude will be positive or negative in the end.

Needs and values are connected and play an important role in our lives. As we prioritize values, we prioritize our needs. These are both meaningful to us. Need can be perceived as a lack of something. For understanding the difference between need and value, we can cite Grác (1979), who states that everything that is needed for an individual is usually also valuable. Need is therefore a narrower concept than value, because not everything that is valued is also needed.

2.2. The Value of Belongingness and Its Importance among Humans

From an evolutionary perspective, being part of a tribe brought many advantages to our ancestors. It increased the probability of obtaining food, engaging in reproduction, and being protected from predators. Those who did not join the group or were excluded were always at a greater risk of not surviving for very long. This behavior was also observed in animals. Like for children, one of the greatest dangers wild animals face is being orphaned or abandoned at a young age. Without anyone to look after them, their chances of survival are very low. Moreover, the lack of interaction between mother and infant has long-term negative effects on future life (Over 2016). Although living conditions and the environment are different today from in the times of our ancestors, the need for connection remains.

People are social creatures; they want to feel loved, accepted, and worthy. According to Brene Brown (2012), those who feel loved and who experience belonging also believe they are worthy of love and belonging. That is why humans connect and identify with other people and organizations, and some of them are also active on social media. They want to build and maintain long-lasting bonds with others.

To be an accepted and valued member of a group is a basic human need. Therefore, we should not forget to mention Abraham Maslow and his hierarchy of needs, which is displayed as a pyramid and is widely applied in educational institutions and business spheres. The pyramid consists of five needs, and is based on the rule that it is first necessary to satisfy lower needs in order to satisfy those of a higher order. In this concept, the need to belong, also known as belongingness, lies at the center of the pyramid as part of the social needs. Despite criticism of Maslow’s hierarchical order, his concept is still very popular, cited and reproduced in many textbooks, even though Abraham Maslow never actually created this pyramid. We do not find it in his original article (Maslow 1943) or in his book (Maslow 1954). Bridgman et al. (2019) investigated and explained the whole story relating to the origin of this pyramid, including the people who created it. Nevertheless, Maslow (1954, p. 43) admits that, “we have very little scientific information about belongingness, although it is a common theme in novels, autobiographies, poems, plays and even in more recent sociological literature.” Another interesting finding is that although Maslow was an atheist, the highest need in his hierarchy was not self-actualization but self-transcendence. He realized that spiritual needs play an important role in an individual’s life. Koltko-Rivera (2006) deals with this topic in more detail.

In addition, belongingness relates to social support, and a person fitting into a group. Social support has a direct or indirect effects on human behavior and quality of life (Antle et al. 2009). There exists a strong tie between social support and measures of well-being (Walen and Lachman 2000). Social support has beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system, the endocrine system, the immune system, and even on gene expression (Cacioppo and Patrick 2008; Uchino 2006). However, the level of social support is not the same in all social groups, or even in religious communities and societies. Zhang et al. (2019) determined that the more homogenous religious groups are, the higher the level of support and comfort they can provide, whereas more diverse religious groups can provide higher levels of challenge. Participants in ideologically diverse conditions reported lower levels of belonging and meaning than participants in ideologically homogeneous conditions.

The opposite of belongingness is loneliness and social isolation. It can be experienced in all age groups, including in the earlier developmental periods (Perlman and Landolt 1999). Adolescents who suffer from chronic loneliness are more likely to report psychopathology, depression, suicidality (Lasgaard et al. 2011) and social skill deficits (Jones et al. 1982; Lodder et al. 2016). Researchers also tested relationships between general belonging, workplace belonging, and symptoms of depression in adults. Although both types of belonging longitudinally did not predict symptoms of depression, they suggested that belongingness cognitions are the proximal antecedent of a depressive response (Cockshaw et al. 2014). Sense of belonging is closely related to bullying (Espelage and Horne 2008; Juvonen 2006), cyberbullying (Underwood and Ehrenreich 2014) and other risky behaviors (Rokach 2002; Rokach and Orzeck 2003; Åkerlind and Hörnquist 1992; Martha Peaslee Levine 2012). Last but not least, social media has a great impact on loneliness (Yang 2016). Children and adolescents who self-reported being lonely communicate online significantly more frequently (Bonetti et al. 2010).

2.3. Religious Beliefs

For many people, religion has become an inseparable part of their identity. Although a relationship exists between religion and identity, Oppong (2013) points out that there is also a need to consider other factors, such as the intensity of religious commitment and parental influence, as children of religious parents are most often religious, too (Assmann 2007).

Oostveen (2019) sees the connection between belongingness and identity in an even deeper sense. In the case of hermeneutics, belonging and identity do not differ. If, for example, someone belongs to Christianity, they are a Christian. However, there could exist another type of belonging—rhizomatic, which expresses the hybrid nature of the cultural codes that fill the lives of individuals with meaning and can be applied to every religion. In this context, the belief can be imagined as multireligious or eclectic.

There are also differences in how people with different religious beliefs experience their level of belonging to religious groups or institutions. For some individuals, religion is a central part of their lives. They cannot imagine life without faith and their religious community. Others can be more interested in a religion’s community and culture than in its beliefs and rituals, and some people can reject religion and religious communities entirely. The key question is: What is religious belief? In a theological or philosophical sense, the term religious belief is usually understood as a kind of faith one believes in or one experiences spiritually (Newman 2004; James 2002).

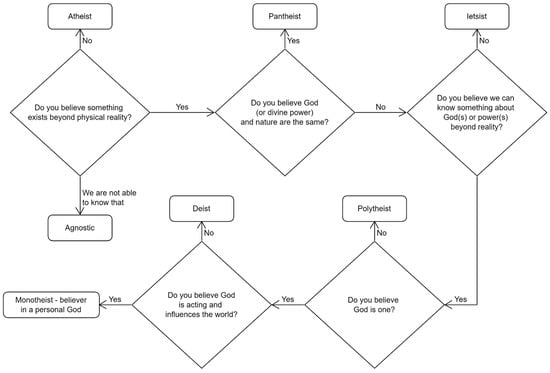

In contrast, we prefer to understand religious belief as fundamental religious attitudes toward the transcendency of the natural world. This leads us to the recognition of seven main religious beliefs:

- Monotheist—belief in a personal God who looks after creation. (Wainwright 2020; Assmann 2007);

- Polytheist—belief in more divine powers. The word “poly” means many. According to (Assmann 2007), polytheism is not just an accumulation of deities, but a structured whole, a pantheon;

- “Ietsist”—belief in a higher power (in “something above us”). Ietsism is originally a Dutch term (“ietsisme”), sometimes translated into English as “somethingism”. The founder of this term is Ronald Plasterk, who used this term in 1997 (Holstein 2020). In 2005, the word “ietsism” was included in the fourteenth edition of the Dutch dictionary (Boon et al. 2005). “Ietsists” do not believe in God, but in something above us. They are spiritual, but not stricto sensu religious);

- Agnostic—belief that perhaps there is something above us, but we are not able to know it. According to Le Poidevin (2010), agnosticism is neither theism nor atheism, but lies somewhere in between. He divides agnostics into two categories—weak agnostics who do not know whether God exists, and strong agnostics who say we cannot know whether God exists or not;

- Atheist—no belief in the existence of anything above us. From a philosophical point of view, atheism is based on the proposition that God does not exist, and there are also no gods. This view was supported by the philosopher Antony Flew (1972);

- Deist—belief in a God who does not interfere in the world in any way. Deism is the belief in an immanent God who does not actively intervene in the affairs of men (Manuel and Pailin 2020);

- Pantheist—belief in the unity of God and nature (God and nature are the same). They share the opinion that God is identical to the cosmos (Mander 2020). Worship is not an acceptable religious practice for pantheists. Pantheists usually deny the existence of a personal God (Michael P. Levine 1994). In our research, we include panentheism (Culp 2020) under the pantheist position, as it is similar, and we suppose the pantheist and panentheist value systems and moral judgement sources are very similar.

These seven fundamental types of religious beliefs are used in our research model, and they are used as items in the nominal scale for measurement of religious belief.

2.4. Attitudes to Institutionalized Religion

While believing in God is traditionally associated with belonging to a church, nowadays, not all believers want to be connected to any religious institution. In the 1990s, British sociologist Grace Davie (1994) described a new phenomenon—“believing without belonging”. She pointed out the fact that many British people are spiritual, but not religious; they do not formally belong to the institutionalized church. A similar situation was observed in Hindu devotees of Jesus Christ in North India. In his book, Vinod (2020) explains that they call themselves Krist Bhakta (Devotees of Christ), even though they were never baptized and never belonged to an institutional church. These Christ devotees do not call themselves Christians, but rather insist on their Hindu identity.

DeYoung and Kluck (2009) describe four main reasons for disillusionment with the church. The first reason is missiological. The church is criticized for losing sight of its mission and having no impact on the world. It is viewed as a failing institution because it ignores the problems of society. The second reason is personal, related the negative image of the church in connection with hypocritical, antiwoman, antigay, judgmental, and close-minded acolytes. The third reason is historical, whereby the church is seen as corrupt. The last one is theological. The church is only plural for Christians, and if all one needs to properly worship Christ are two or three people with an intent to be with the Lord, wherever they decide to meet, they do not to consider it important to participate in an institutionalized church service (see Holy Bible: New Living Translation, Catholic 2001).

Another phenomenon we should consider is “belonging before believing”, which stands in contrast to the traditional “believing before belonging” concept (Weyers and Saayman 2013). To be a member of a particular social group is very important, especially for new believers. Some people join religious groups because they are curious and find a group’s beliefs attractive, or because something bad happened to them and they have undergone an intense emotional experience. Because of this, they have started to be spiritual or religious. However, the reason they start to see religion as attractive could also be because they believe they will get answers to their problems. New modern seekers need to belong first before they are ready to fully believe. According to Saayman (2010), the church only seems interested in numbers of “converts”, rather than in the quality of life in a believing community. But new believers need to be accepted by the religious community. Murray (2004) defines four set models of churches: the open set model, the fuzzy set model, the bounded set model, and the centered set model. The last one corresponds to the concept of belonging before believing. In contrast to the bounded set model, which requires beliefs and behavior first, centered set churches do not have clear boundaries, only those who are closer to the center than others. In a centered set approach, a person might be quite a distance from the center, but as long as they are facing the center and moving toward it, they belong. It is believed that although centered set churches are not the normal way of practicing religion today, they could become the predominant model of the future.

With reference to all the above models, we tried to define four possible attitudes to religious institutions, from the full rejection of all religious institutions to being an active member in a religious church/institution.

2.5. Source of Moral Judgements

There is no doubt religious beliefs influence attitudes towards many aspects of life. We assume that the most important among them is the morality of an individual and the related philosophical and theological background of moral judgement. This assumption is based on the transitive relationship between religious belief as the source of moral motivation and moral motivation as a factor influencing moral judging. To justify this assumption, we need to more closely explain the term moral judgement and the transitive relationship mentioned before.

Garret Cullity (2011, Article summary) states: “The activity of moral judgement is that of thinking about whether something has a moral attribute. The thing assessed might be an action, person, institution or state of affairs, and the attribute might either be general (such as right or badness) or specific (such as loyalty or injustice).” In the most common way, the moral attribute means that something is considered right or wrong from the point of view of the person who makes this judgement. For our research, the results of these judgements are not as important as if and how these judgements are influenced. A widely accepted thesis exists concerning the internal connection between moral judgement and moral motivation (Copp 2007a). Stephen Darwall (1983) called this connection “judgement internalism”, and it has a wide impact on metaethics. However, for our argumentation, the most important impact is the motivation that has a significant influence on oughtness and the degree of specific moral judgement. The last step in our theoretical assumption is the relationship between motivation and religious belief. This relationship has been researched and discussed by many authors before, but for our argumentation the most interesting point is the connection between meaning and motivation put forward by Crystal Park, Donald Edmondson and Amy Hale-Smith (Park et al. 2013). According to these authors, religion meets the need for the meaning system and provides it in daily life. “Religion is not only a prototypic source of coherence, certainty, identity and existential answers but also frequently prescribes individuals ultimate life goals (e.g., living ethically, reaching heaven or paradise, gaining enlightenment) for which individuals strive.” (Park et al. 2013). In the context of the statement by Park et al., religion influences not only the person’s motivation, but it is also internally connected with another key part of personality—the value system. Hence, we can deduce that the motivation connects all substantial phenomena, and we assume that they are mutually influenced: the personal value system, including the value of belongingness; moral judgements, and religious belief. This is why we pose the research question as to whether an influence comes from religious belief and the importance of the value of belongingness in one’s life for practical moral thinking and judging, and what precisely is the nature of this influence.

As we had to categorize and theoretically distinguish the religious beliefs in the text above, we now need to do the same theoretical distinction in the case of moral judgements. The problem with the distinction of moral judgements is much more complicated because of the large number of ethical schools, and the deep inner diversity in ethical thinking (Copp 2007b).

Furthermore, as regards the sources of moral judgements, we should mention the distinction between the “morality of care” and “morality of justice” approach in our theorizing, because we assume this distinction helps us better understand the background of personal moral attitudes from the developmental and psychological points of view. Morality of care, which is attributed to Carol Gilligan (1982), focuses especially on attentiveness, responsibility, competence, responsiveness and plurality (Tronto 2005, 2013), whereas morality of justice emphasizes individual interests, rules and rights. Morality of care is oriented more towards social interaction, while “a morality of justice, in contrast, places a premium on individual autonomous choice and equality” (French and Weis 2000, p. 125). We believe both moralities are involved in making ethical judgements, and together they form the source of moral judgements. This is because personal moral judgements have their roots in beliefs and values (including religious belief), and they are undoubtedly influenced by the personality and life experiences of the one making the judgement.

In our research, we tried to include both the complexity of ethical thinking and the psychology of moral judgements. Despite the huge plurality of ethical theories, we tried to postulate four fundamental and significantly different sources of moral judgements, which can be well distinguished by people in the population and involve a well-graded personality and emotional influence. These four ethical attitudes can also be recognized among ethical theories. In the case of the source of moral judgements, we distinguish:

- Strictly normative attitude—“There is a fixed order of values and moral laws that must be sought and respected in life. This order does not change over time and is still valid. What is good is in accordance with these rules.” This approach is close to moral realism, and also to several normative ethical schools such as deontology, virtue ethics, and value theory (Copp 2007a, pp. 19–31);

- Strictly situational ethics—“Circumstances always determine whether human behavior is good. The same behavior can sometimes be good and sometimes bad.” Based on Dewey’s situational ethics in pragmatism (Dewey 1994), Fletcher’s situation ethics (Fletcher 1997) and some theological approaches (Migliore 2010; Fuchs 1983);

- Strictly consequential utilitarian/pragmatic ethics—“It is always good to act in a way that has a good goal, even if inappropriate means are used to achieve it.” Based on Bentham’s (1970), Mill’s (2001) and James’ (2000) ethics;

- Strictly emotional ethics—“When deciding whether action is good or bad, we should always be guided by emotion. We can sense what is really good.” Based on Scheler’s material value ethics and personalism (Scheler 2004).

2.6. Solidarity

In our research on the role of the value of belongingness in the context of religious belief and the source of moral judgements, there is one other factor influencing the entire researched area. This factor encompasses the whole framework of the value of belongingness, religious beliefs, attitudes to religious institution, and sources of moral judgements in the social dimension, expressed in practical actions as solidarity. The understanding of solidarity could vary. In our case, we will follow the understanding offered by David Miller (2017), who takes solidarity to be a feature of the relationship between people. When we say a group of people displays high, low or no degree of solidarity, we are saying something about the way the group of people regard and interact with one another. Schweigert (2002) explains that in the context of solidarity, shared membership is characterized by mutual care and respect, while subsidiarity, a complementary principle of community development, is understood as a guide for social action, directing decision-making on the social level that is most effective, with particular respect for the power of local and communal levels of society. In addition, we agree with Onora O’Neill (1996), who distinguished two types of solidarity: solidarity with a group of people and solidarity among a group of people. “Solidarity with” is described as a unilateral relationship without any expectation of reciprocation. “Solidarity among” is perceived more broadly. First, it is shared via a group; second, there exists not only reciprocation, but also the support and protection of members; third, the group is collectively responsible for the actions of members; and fourth, no member should get more unless other members have the same benefit. As we see, solidarity brings many benefits for group members, but it is also connected to moral obligations.

Solidarity is mostly connected with emotional ties and altruistic behavior. Bar-Tal (1986) provides a definition of altruism based on five characteristics of this human behavior. Altruistic behavior must: 1. be a benefit to other people; 2. be performed voluntarily; 3. be performed intentionally; 4. the benefit must be the goal in itself; and 5. it must be performed without expecting any external reward. Although altruism relates to sacrifice, Nagel (1979) claims that altruism should be understood not as self-sacrifice, but merely as a willingness to act in consideration of the interests of other people, without ulterior motives.

Laitinen and Pessi (2014) separate solidarity from justice and duties. Meulen (2017) explains that while solidarity refers to a relationship with others, justice sees man as an isolated being focused on his own interests. So, in the case of justice, there is a lack of moral responsibility towards the well-being of other members.

With respect to all of the mentioned theoretical concepts and discussions concerning solidarity and subsidiarity, we believe the attitude toward required/requested solidarity in society could be expressed using three categories. These categories of “solidarity level” in the social policy of states and at all lower levels of state or local government must begin with strong support for subsidiarity, with specific exceptions (disabled, ill or old people). The next attitude could represent those who believe that solidarity and subsidiarity must be balanced as much as is achievable. Finally, the end of the scale represents attitude calls for the maximum employment of subsidiarity at all levels of state and local governments. We believe these three attitudes represent the theoretical background of solidarity presented in this section. In the section on research methods, we transform these attitudes into measurable categories comprehensible by the respondents.

3. Aim of the Research

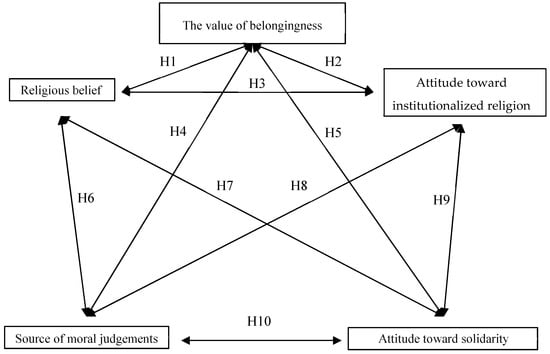

The main purpose of our research is to determine whether significant relationships exist among the value of belongingness and attitudes to religious belief, institutionalized religion, moral categories, and solidarity. We assume that the value of belongingness precedes the need to belong and determines attitudes towards moral judgments (H4), religious beliefs (H1) and institutional religion (H2), and has an impact on the formation of the attitude toward solidarity and social responsibility (H5). Additionally, we test the relationship between attitudes toward religious beliefs and religious institutions (H3). Next, we expect to find that two key variables significantly related to the value of belongingness (1—attitudes toward religious beliefs, and 2—attitudes toward religious institutions) are significant factors influencing the source of moral judgements (H6, H8) and the attitude toward solidarity (H7, H9). For a complete image of the relationships between all variables, the relationship between the source of moral judgements and the attitude toward solidarity is assumed and was tested (H10). The complexity of all ten hypotheses is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model and hypotheses.

4. Research Methods

4.1. Definition and Measurement of Variables

As we mentioned above, the value of belongingness is an important part of an individual’s value system, and influences important decisions and social behaviors.

The value of belongingness (VB) was measured as the preference of value on a continuous scale internally demarcated by one and ten. Preference of value is perceived as a tendency to consider something desirable or undesirable (Zajonc 1980). The measurement has been provided using a line on which only extremes are described. Respondents were asked to mark a position on this line without specifying the numeric value of the response. The only clues for them were margins (“this is definitely not my value, I do not desire it at all” on the left-hand side and “this is definitely my value, it fully expresses my position” on the right). Respondents who did not use the online survey marked their position on the limited line; their answer was analyzed using a ruler and transferred to the scale of one to ten. Because we needed to use this variable as a category, we had to transfer it to a scale containing four categories. The categorization was calculated using the mean of measured preferences (μ) and standard deviation (σ), where:

- VB-1—is the category of preferences < μ – σ;

- VB-2—is the category of preferences ≥ μ – σ and < μ;

- VB-3—is the category of preferences ≥ μ and < μ + σ;

- VB-4—is the category of preferences ≥ μ + σ.

We assumed a relationship exists between the value of belongingness and three significant spheres of life.

The first sphere consists of two independent kinds of attitudes: (1) the religious belief and (2) the attitude toward institutionalized religions.

- Although the religious belief can be expressed in different ways, and in some special cases the person is not able to precisely formulate their own relationship with God, divine powers, spirits or other forces that are believed in, we assume that most people know what they believe and are able to answer several fundamental questions concerning their belief. The classification of religious belief used in our research is based on several distinctions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distinction of religious beliefs.We measured the variable “religious belief” using a categorized scale containing these seven categories:

Figure 2. Distinction of religious beliefs.We measured the variable “religious belief” using a categorized scale containing these seven categories:- Monotheist—believes in a personal God who looks after creation;

- Polytheist—believes in more divine powers;

- Ietsist—believes in a higher power (in “something above us”);

- Agnostic—believes there is perhaps something above us, but we are not able to know;

- Atheist—does not believe in the existence of anything above us;

- Deist—believes in a God who does not interfere in the world in any way;

- Pantheist (including panentheists)—believes in the unity of God and nature (God and nature are the same).

- The second constituent of the first sphere is the attitude toward institutionalized religion as an inseparable part of society and culture. As we mentioned in the theoretical part of this article, religious belief is not always necessarily connected to religious institutions (e.g., church, community, sect, religious movement), nor is it institutionalized in any way. We therefore defined these four attitudes toward institutionalized religions (ATIR) and the desire to belong via the level of religiosity/spirituality of a person:

- ATIR-1

- I completely reject institutionalized religion as such and consider it unnecessary or even harmful;

- ATIR-2

- I am willing to admit that institutionalized religion can play an important role in some people’s lives, but this is not my case;

- ATIR-3

- I consider myself a religiously active person and I need to express (perhaps not often) my religious beliefs (e.g., by praying), but I do not belong and do not want to belong to any organized church or other type of religious institution;

- ATIR-4

- I consider myself a religiously active person and I belong to a specific church or religious institution.

The second sphere concerns the morality of man and the way sources of moral judgements are made. The source of moral judgements (SMJ) was measured using a categorized scale with the following categories (discussed above in the section concerning moral judgements):

- SMJ-1

- There is a fixed order of values and moral laws that must be sought and respected in life. This order does not change over time and is still valid. What is good is in accordance with these rules;

- SMJ-2

- Circumstances always determine whether human behavior is good. The same behavior can sometimes be good and sometimes bad;

- SMJ-3

- It is always good to act in a way that has a good goal, even if inappropriate means are used to achieve it;

- SMJ-4

- When deciding whether behavior is good or bad, we should always be guided by emotion. We can sense what is truly good.

The third sphere refers to the attitude toward solidarity and the level of solidarity/subsidiarity of the respondents (SOL). The respondents’ balance between solidarity and subsidiarity was measured on a categorized scale containing three distinguished opinions, from extreme subsidiarity (SOL-1) through appropriate solidarity (SOL-2) to extreme solidarity (SOL-3):

- SOL-1

- Everyone should take care of themselves and take full responsibility for their future. The state, regions or municipalities should only take care of people who, for serious reasons, cannot in any way take care of themselves (seriously ill, disabled, etc.);

- SOL-2

- The state, regions and municipalities should—adequately, within their economic capabilities—be responsible and take care of all socially disadvantaged and handicapped individuals, even if the disadvantage or handicap is small;

- SOL-3

- The state, regions and municipalities should adopt a significantly greater share of responsibility for citizens, and provide them with access to care, housing, work and fair earnings.

4.2. Data Collection and Statistical Procedures

To achieve the research aim, we planned and conducted a nationwide survey. The research was designed as cross-sectional ex-post-facto. This approach is often used to measure and analyze the impacts of the social factors on specific phenomena (Bryman 2016; Black 1999). The survey was carried out across the Czech Republic. The examined relationships were part of a wider research focusing, besides religious belief, on attitudes toward morals, social policy, religious institutions, and the value orientation of the respondents, called Research of Values, Key Worldview Questions, Leisure, Social Threats, and ICT Skills 2018. We used the Social Survey Project (2018) for questionnaire distribution and data collection. This software is designed not only to publish and distribute the surveys, but also to perform the statistical analysis of collected data. All the calculations were performed using this instrument.

The survey examined data collected using a structured questionnaire (Black 1999), which was completed and returned by 5175 responders. Of these, 2204 (42.59%) were men, 2957 (57.14%) were women and 16 (0.17%) were of another gender. The respondents were aged between 15 and 90, with an average age of 46.8. The data were collected from September 2018 to June 2019. The questionnaire contains 75 questions and more than 200 sub-questions dependent on previous answers. It is divided into six sections (ICT Skills, Leisure, Values, Worldview, Economic Situation, and Socio-demography). The structure of the key questions in this paper is described in the sections above (religious belief, attitude toward religious institutions, sources of moral judgements, attitude toward solidarity and, among 40 other values, the value of belongingness). The survey was delivered both electronically and in paper form. There were volunteers involved in questionnaire distribution and respondent addressing, and thanks to their reflection we calculated the rejection rate at about 40%. In the case of respondents who were not able to fill out the questionnaire online, in-person interviews or assisted completion of the questionnaire were utilized. The respondents were selected across the country using a stratified selection with the stratification criteria of gender, age, and size of the municipality. Inside the stratified groups, the questionnaire was widely and randomly spread across the population, thanks to the more than 200 volunteers who helped by delivering the survey. The collected data can be considered representative of the gender and age of respondents and the size of the municipality—in most of the stratification criteria, the difference between populations and samples in terms of stratification criteria was less than 10%.

Because all the variables were measured as categorical or were categorized (the value of belongingness), the statistical assessment related to the hypotheses was based on χ2 statistics for R × C contingency tables, and all fundamental decisions were complemented with the calculation of standardized (adjusted) residuals for each cell (Sheskin 2011; Agresti 2019; Azen and Walker 2021).

5. Research Results

Hypothesis H1, concerning the relationship between the preference for the value of belongingness (VB) and the religious belief, has been confirmed (χ2(df = 18) = 107.9194, p < 0.001, n = 5172). Detailed results are displayed in Table 1. The value of belongingness is significantly important for believers in a personal God (p < 0.05) and, more interestingly, for those who believe in “something above us” (p < 0.001). On the contrary, atheists are in strong and significant opposition to it (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Relationship between the preference for the value of belongingness (VB) and religious belief.

Hypothesis H2, concerning the relationship between the preference for the value of belongingness (VB) and the attitude toward institutionalized religion (ATIR), has been confirmed (χ2(df = 9) = 75.8763, p < 0.001, n = 5173). Detailed results are displayed in Table 2. The desire to belong to institutionalized religion is significantly important for religiously active people, who belong to a specific church or religious society (p < 0.05), while an extremely low desire to belong to an institutionalized religion was confirmed in people who reject institutionalized religion (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Relationship between the preference for the value of belongingness (VB) and the attitude toward institutionalized religion (ATIR).

Hypothesis H3, concerning the relationship between the attitude toward institutionalized religion (ATIR) and religious belief, has been confirmed (χ2(df = 18) =3810.64, p < 0.001, n = 5171).

Detailed results are displayed in Table 3. The highest desire to belong to an institutionalized religion was confirmed in monotheists (p < 0.001), and surprisingly also deists (p < 0.01). Religiously active people who do not want to belong to any organized church were significantly present among deists (p < 0.001), pantheists (p < 0.001), “ietsists” (p < 0.001), and polytheists (p < 0.001), but also monotheists (p < 0.001). Religion can play an important role in people’s lives, but not in the case of ietsists (p < 0.001), agnostics (p < 0.001) and atheists (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Relationship between the attitude toward institutionalized religion (ATIR) and religious belief.

Hypothesis H4, concerning the relationship between the preference for the value of belongingness and source of moral judgements (SMJ), has been confirmed (χ2(df = 9) = 65.7728, p < 0.001, n = 5174). Detailed results are displayed in Table 4. The preferences for the value of belongingness were significantly highest in people who prefer a fixed order of values and moral laws (p < 0.001), which is in contrast to those who are goal-oriented in their actions (p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Relationship between the preference for the value of belongingness and source of moral judgements (SMJ).

Hypothesis H5, concerning the relationship between the preference for the value of belongingness and solidarity (SOL), has been confirmed (χ2(df = 9) = 17.3863, p < 0.01, n = 5172). Detailed results are displayed in Table 5. The lowest statistics related to value of belongingness were discovered in individuals whose opinion is that everyone should look after themselves (p < 0.001), which is in contrast to those whose opinion is that the state, regions and municipalities should take care of all socially disadvantaged and handicapped people (p < 0.01). The highest preferences for the value of belongingness were not statistically significantly connected with solidarity.

Table 5.

Relationship between the preferences for the value of belongingness and solidarity (SOL).

Hypothesis H6, concerning the relationship between the religious belief and source of moral judgements (SMJ), has been confirmed (χ2(df = 18) = 437.8589, p < 0.001, n = 5171). Detailed results are displayed in Table 6. A fixed order of values and moral laws was preferred by monotheists (p < 0.001), while “ietsists” (p < 0.001) and agnostics (p < 0.001) held opposite opinions. According to them, human behavior is determined by circumstances (p < 0.001). Polytheists (p < 0.01) and atheists (p < 0.001) act according to goals, while “ietsists” (p < 0.001) do not share this opinion. Emotions play an important role in the case of “ietsists” (p < 0.001), agnostics (p < 0.001) and pantheists (p < 0.001), while monotheists (p < 0.001) and atheists (p < 0.001) do not share this opinion.

Table 6.

Relationship between the religious belief and source of moral judgements (SMJ).

Hypothesis H7, concerning the relationship between the religious belief and solidarity (SOL), has been confirmed (χ2(df = 12) = 35.5142, p < 0.001, n = 5169). Detailed results are displayed in Table 7. Atheists share an opinion that everyone should take care of themselves (p < 0.001), which monotheists (p < 0.05) and agnostics (p < 0.05) do not share. The state, regions and municipalities should take care of all socially disadvantaged and handicapped in the opinion of monotheists (p < 0.01), while opposite opinions are held by atheists (p < 0.01).

Table 7.

Relationship between the religious belief and solidarity (SOL).

Hypothesis H8, concerning the relationship between the attitude toward institutionalized religion (ATIR) and source of moral judgements (SMJ), has been confirmed (χ2(df = 9) = 331.5529, p < 0.001, n = 5172). Detailed results are displayed in Table 8. Those who completely reject institutionalized religion are those whose behavior is determined by goals (p < 0.001), and not by circumstances (p < 0.05) or emotions (p < 0.05). Those who admit that institutionalized religion can play an important role in some people’s lives are those whose behavior is determined by circumstances (p < 0.001) and emotions (p < 0.05), and not by a fixed order of values and moral law (p < 0.001) or goals (p < 0.001). Those who consider themselves a religiously active person, yet do not belong to any organized church, are those who need a fixed order of values and moral law (p < 0.001) in their life, and their behavior is not determined by circumstances (p < 0.001). Those who consider themselves a religiously active person and belong to a specific church or religious society are those who need a fixed order of values and moral law in their life (p < 0.001).

Table 8.

Relationship between the attitude toward institutionalized religion (ATIR) and source of moral judgements (SMJ).

Hypothesis H9, concerning the relationship between the attitude toward institutionalized religion (ATIR) and solidarity (SOL), has been confirmed (χ2(df = 6) = 32.2211, p < 0.001, n = 5170). Detailed results are displayed in Table 9. Those who completely reject institutionalized religion share the opinion that everyone should look after themselves (p < 0.001), and not the state, regions, and municipalities (p < 0.001). Those who admit that institutionalized religion can play an important role in some people’s lives also share the opinion that everyone should look after themselves (p < 0.05), but are against the opinion that the state, regions, and municipalities should take care of citizens (p < 0.05). Those who consider themselves a religiously active person, yet do not belong to any organized church, share the opinion that the state, regions, and municipalities should take care of citizens (p < 0.05). Those who consider themselves a religiously active person and belong to a specific church or religious society have an opinion opposite to those who reject religion. For them, it is the state, regions and municipalities who should take care of people (p < 0.001).

Table 9.

Relationship between the attitude toward institutionalized religion (ATIR) and solidarity (SOL).

Hypothesis H10, concerning the relationship between solidarity (SOL) and source of moral judgements (SMJ), has been confirmed (χ2(df = 6) = 107.3740, p < 0.001, n = 5171). Detailed results are displayed in Table 10. Those who shared the opinion that everyone should look after themselves need a fixed order of values and moral law in their life (p < 0.001), which is in contrast to those whose behavior is determined by circumstances (p < 0.001) and goals (p < 0.05). That the state, regions and municipalities should take care of all in them is an opinion held by those whose behavior is determined by circumstances (p < 0.001), which is in contrast to those who need a fixed order of values and moral law in their life (p < 0.001) and those who are ruled by emotions (p < 0.001). The opinion that the state, regions, and municipalities should take care of citizens is strongest in those ruled by emotions (p < 0.001) and goals (p < 0.05), and lowest in those who need a fixed order of values and moral law in their life (p < 0.001) and whose behavior is determined by circumstances (p < 0.001).

Table 10.

Relationship between solidarity (SOL) and source of moral judgements (SMJ).

6. Discussion

The results of our research revealed some interesting findings that need to be addressed in this discussion section. They also confirm the previous findings of several authors (Krok 2015; Chan et al. 2020) that values and religion strongly influence each other.

6.1. The Value of Belongingness Is Strongly Connected to Attitudes toward Religious Belief and Institutionalized Religion

Research has shown that the value of belongingness is important not only in the case of monotheists, but also “ietsists”. Although in the case of monotheists this finding could be expected, it seems that “ietsists” need to belong to a community and be accepted as a member as well. This finding is consistent with the concept of “belong before believe” and centered set churches, which we described in the theoretical part. For these “spiritual seekers”, it is important to belong to a community regardless of belief. Yet for most conservative churches, it can be an inadmissible idea to invite non-Christians into their community. But more openness to non-Christians could provide some benefits to the church itself, especially from a missionary point of view. Weyers and Saayman (2013) stated that during Christian missionary work around the 16th and17th centuries, missions were rather exploratory, with no need to put new seekers through the process of catechism. That was also why Christian missionaries, during a very short time, baptized several hundred people. Weyers and Saayman (2013) also emphasized the importance of the teachings of Jesus, which were not a dogmatic system. Jesus had no problem carrying out his ministry amongst those who did not yet believe in him as the Messiah. The concept of “belong before believe” is in fact not new.

The highest desire to belong to institutionalized religion was confirmed in religiously active people, who belong to a specific church or religious society. These people were not only monotheists, but surprisingly, also deists. From a historical perspective, we can name famous deists such as Isaac Newton, Blaise Pascal, David Hume and Voltaire, but also the Freemason organization (Bernardo 2020). So, we can say that deists want to be a member of an institutionalized organization/religion, but in contrast to monotheists, they believe that God does not interfere in the world in any way.

Those who consider themselves active religious people, but who do not want to belong to any organized church, were deists, pantheists, “ietsists” and polytheists, but also monotheists. This finding is related to the concept of “believing without belonging”, which we mentioned in the theoretical part. These people are spiritual but have some reason for not wanting to belong to any organized church. Interestingly, this finding shows that even some monotheists do not want to belong to any organized church. These committed Christians who lost trust in the church are sometimes called “dones” (those who are “done with church”). These “dones” can have several reasons for their disillusionment toward the church. In the theoretical part, we mentioned the authors DeYoung and Kluck (2009), who named four main reasons, though these are not exhaustive. We should not forget the impact of modern technology and social sites, which can also play an important role in the lives of “dones”.

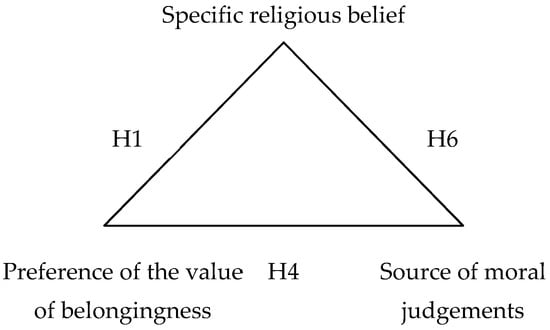

6.2. The Value of Belongingness Is Strongly Connected to the Source of Moral Judgements and Also Depends on Religious Belief

Each religious belief we recognized before has a specific relationship to the value of belongingness (H1). These relationships could be positive (“ietsist”, monotheists), neutral (agnostics, polytheists, deists, and pantheists) or negative (atheists). It seems clear that a neutral relationship between specific beliefs and the value of belongingness has a minimal influence on the transited relation to moral judgements, but there is a strong impact on moral judgements when it is positive or negative. In these cases, we assume a certain kind of tension within the triangle of specific religious belief, preferences of the value of belongingness and the religious/philosophical source of the moral judgement (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relationships to sources of moral judgements.

In the case of positive relationships between the preferences for the value of belongingness and religious belief, two beliefs should be discussed—“ietsists” and monotheists. Despite the similarity in the relationship with the value of belongingness, there are strong differences in the sources of moral judgements between monotheists and “ietsists”. The difference between the two of them in terms of the sources of moral judgements probably causes the most significant differences between these groups. While “ietsists” are inclined toward judgements based on emotion or influenced by circumstances, monotheists are strongly against these, and are oriented toward strictly normative ethics. We assume this attitude comes from the strong connection of monotheists to religious institutions, which are often well known for their rigid moral rules and are often inclined toward certain kinds of moral puritanism. The “ietsists” are missing these moral bonds, and are more liberal in their judgements. The relationship of “ietsists” to the value of belongingness is much stronger (p < 0.001) than in the case of the monotheists (p < 0.05). Therefore, we assume their attitude toward belonging is quite different because of different motivations for belonging. “Ietsists” are those who understand belonging as the fulfilment of a social need, and their understanding of morality is close to the morality of care. In this sense, the “iestsists” aim for the subjectivation of moral norms and principles. On the other hand, the belonging of monotheists corresponds more to the concept of the morality of judgement. Their needs are more related to loyalty and trust in moral law. Monotheists in this sense aim for the objectivization of moral norms and principles.

In the case of negative relationships between the preference for the value of belongingness and religious beliefs, only one belief should be discussed—atheists. This very specific group of non-believers is strongly oriented toward goals and utilitarianism. Belongingness is not a value to them, so we can assume their motivation regarding morality also has no strong social dimension. Generally, atheists are more pragmatic people than others, who do not feel limited by social and/or moral norms.

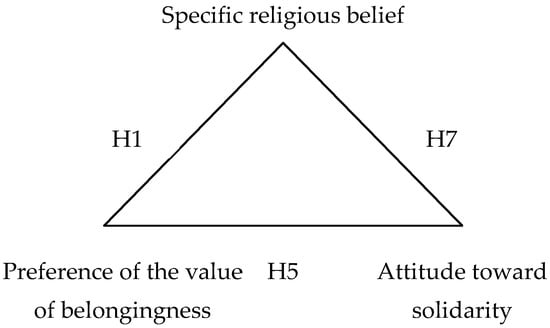

6.3. The Value of Belongingness Is Strongly Connected to the Attitude toward Solidarity and Depends on Religious Belief

In this case of the value of belongingness, attitude toward solidarity and religious belief relationship (Figure 4), positive, neutral, and negative relationships exist, similar to the described “triangle” above (Figure 3). Therefore, we will focus only on the positive and negative relationships that influence solidarity attitudes.

Figure 4.

Relationships of solidarity attitudes.

Monotheists and “ietsists” with positive attitudes towards preferences for the value of belongingness and religious belief hold different attitudes toward solidarity. While ietsists are not significantly connected to a specific attitude toward solidarity, monotheists are against strong subsidiarity, and share the opinion that the state, regions, and municipalities should take care of all socially disadvantaged and handicapped people. It seems the “ietsists” are highly prosocially oriented, although there are many of them (657) who prefer stronger subsidiarity as a principle on which social policy is built. On the other hand, in this group of people there are also 234 “ietsists” who agree with the idea of broad social support from society for all its members (SOL-3 extreme solidarity). “Ietsists” also share this attitude of the independence of solidarity with pantheists, polytheists, and deists, who, on the contrary, do not hold a positive attitude towards the value of belongingness. Monotheists are probably more influenced by church doctrine (they are also those who belong to church communities) and they expect more community responsibility. This is why they significantly support solidarity in helping disadvantaged and handicapped people. This solidarity is not inappropriate and corresponds to the economical capabilities of society. We expected that this attitude, in the group of religious people, would be influenced by the moral principles of monotheist religions, which are very similar in many of them. On the contrary, agnostics, those who principally doubt religious matters, significantly support appropriate solidarity, although the significance is lower (p < 0.05).

Negative relationships between the value of belongingness and religious belief are represented by atheists, who are strongly oriented toward subsidiarity rather than solidarity. According to their attitude that everyone should look after themselves, they are strongly against collective responsibility. This is also confirmed secondarily by their negative attitude toward the value of belongingness.

In the area of solidarity attitudes, another interesting fact was discerned: there was no group of people across all religious beliefs (H7) that had a significantly distinctive attitude toward extreme solidarity (SOL-3). This means that in any religious group, there exists an expected number of people (c. 18%) who are strongly solidarized, which is probably beyond the economic capabilities of society.

This finding is in line with Abela’s (2004) statement that institutionalized religion is still important for social solidarity, though less important for the development of global solidarities. According to our findings, the highest level of solidarity was discovered (H9) among those who do not, and do not want to, belong to any church or religious society. This group of people very often includes “dones”, who were in the past members of a church or religious society, but for some reason decided to leave. Compared to monotheists, these people tend toward extreme solidarity, which to some extent could reach global solidarity.

In conclusion, we believe that for improving global solidarity in churches or religious societies, more prosocial religious leaders and activists are needed. Their actions and activities in relation to citizens can attract not only the religiously unaffiliated, but also diverse religious and ethnic groups. This approach without boundaries can be a new means of building a diverse community, and demonstrating that caring for citizens matters. Pope Francis (2021) in his Easter speech reminded people that Christ’s love was not selective; he embraced everyone, which made him a Good Shepherd. Religious leaders should follow His example.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

The results of our research brought to light new facts, which we addressed in the discussion section. In conclusion, we have decided to formulate several recommendations, which we perceive based on our research findings as essential for the future development of every church or religious society:

- With growing secularization, churches (or religious societies) face new challenges, and their future will in many ways depend on whether they will be able to deal with these changes or not. The assumption that believers will remain believers forever seems to be wrong, as many more people could decide to experience their spirituality out of institutionalized religions. Unless the approach of any church or religious society changes, they could and probably will lose their believers and members. With growing numbers of “dones” (those who have given up on institutionalized religion for some reason; they are spiritual but not religious) and “nones” (those who have no religious affiliation nor any particular set of religious beliefs), churches or religious societies should change the idea that it is necessary to believe first before a person can (or will want to) belong. We must emphasize that those we consider “nones” are not only atheists. Even those who were believers in the past and for some reason lost trust in institutionalized religion and religious beliefs could be counted as “nones”. A church that reflects this change needs to realize that people who plan to leave it, or those who are new “seekers” and not yet believers, need to feel welcome and that they are respected members (or associates) of the community. It is important for them to feel accepted, cared for and, especially, not judged. Many of these people find relationships more important than religious belief and doctrine. Often, they are not primarily interested in the content of what the church believes in, but they almost always need open dialogue. None of them want to only be passive listeners;

- For the future of religions, it is important to realize that each group and subgroup of religious believers has a different approach to morality. For example, the group of “ietsists” faces a great obstacle in accepting strict moral norms or deeply rooted traditional attitudes to several moral problems. They are more independent and open-minded in moral judgements. In the case of morality, they are ruled more by emotions and circumstances than by a strict order of values and/or moral norms, as the monotheists are. In the case of Christian churches, the morality of care, which is a greater concern of “ietsists” than of many monotheists incorporated in traditional churches, could be theologically substantiated, as in the gospels Jesus often shows that love is more important than the law (see, e.g., Holy Bible: New Living Translation, Catholic 2001, Matt 12: 6–13). In the everyday life of church communities, the morality of judgement often prevails. The importance of the morality of care was also emphasized by Pope Francis (2013)—“This I ask you: be shepherds, with the ‘odour of the sheep’, make it real, as shepherds among your flock, fishers of men.”

8. Limitation of Study

Although we considered the value of belongingness as a relatively universal and worldwide value, attitudes towards religious belief, moral judgement and solidarity may to some extent vary from country to country, so our findings are generalizable only to the Czech population. Comparative research would be very beneficial to a higher level of understanding and clarification of the researched problem. Another limitation was that the research data were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic, and it would therefore be interesting to conduct a comparative study between the pre- and post-pandemic periods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P. and P.M.; methodology, J.P.; software, J.P.; validation, J.P.; formal analysis, J.P. and P.M.; investigation, J.P. and P.M.; resources, P.M.; data curation, J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P. and P.M.; writing—review and editing, J.P. and P.M.; visualization, J.P.; supervision, P.M.; project administration, P.M.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Internal grant agency of Palacký University, grant number IGA_CMTF_2021_007 Values context of social functioning I.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to informed consent obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abela, Anthony M. 2004. Solidarity and Religion in the European Union: A Comparative Sociological Perspective. In The Value(s) of a Constitution for Europe. Edited by Peter Xuereb. Malta: European Documentation and Research Centre, University of Malta, pp. 71–101. Available online: http://staff.um.edu.mt/aabe2/EDRC%20Abela.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Agresti, Alan. 2019. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd ed. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerlind, Ingemar, and Jan O. Hörnquist. 1992. Loneliness and Alcohol Abuse: A Review of Evidences of an Interplay. Social Science & Medicine 34: 405–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antle, Beverley J., Gert Montgomery, and Christine Stapleford. 2009. The Many Layers of Social Support: Capturing the Voices of Young People with Spina Bifida and Their Parents. Health & Social Work 34: 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, Jan. 2007. Monotheism and Polytheism. Ancient Religions. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.4159/9780674039186-006/html (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Azen, Razia, and Cindy M. Walker. 2021. Categorical Data Analysis for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2nd ed. New York and London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal, Daniel. 1986. Altruistic Motivation to Help: Definition, Utility and Operationalization. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 13: 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bentham, Jeremy. 1970. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Edited by J. H. Burns and H. L. A. Hart. The Collected Works. London: Athlone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, Giuliano Di. 2020. Freemasonry: A Philosophical Investigation. Pittsburg: Dorrance Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Thomas R. 1999. Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistics. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti, Luigi, Marilyn Anne Campbell, and Linda Gilmore. 2010. The Relationship of Loneliness and Social Anxiety with Children’s and Adolescents’ Online Communication. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 13: 279–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boon, Toon den, Dirk Geeraerts, Nicoline van der Sijs, and Nicoline van der Sijs. 2005. Van Dale groot woordenboek van de Nederlandse taal. Utrecht: Van Dale. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgman, Todd, Stephen Cummings, and John Ballard. 2019. Who Built Maslow’s Pyramid? A History of the Creation of Management Studies’ Most Famous Symbol and Its Implications for Management Education. Academy of Management Learning & Education 18: 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Brene. 2012. Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead, Unabridged edition. Ashland: Blackstone Audio, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, Alan. 2016. Social Research Methods, 5th ed. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, John T., and William Patrick. 2008. Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection, Reprint ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Stephanie W. Y., Wilfred W. F. Lau, C. Harry Hui, Esther Y. Y. Lau, and Shu-fai Cheung. 2020. Causal Relationship between Religiosity and Value Priorities: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Investigations. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cockshaw, Wendell D., Ian M. Shochet, and Patricia L. Obst. 2014. Depression and Belongingness in General and Workplace Contexts: A Cross-Lagged Longitudinal Investigation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 33: 448–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Copp, David. 2007a. Introduction: Metaethics and Normative Ethics. In The Oxford Handbook of Ethical Theory. Edited by David Copp. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Copp, David, ed. 2007b. The Oxford Handbook of Ethical Theory. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cullity, Garrett. 2011. Moral Judgement. In Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Milton Park: Taylor and Francis, Available online: https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/moral-judgement/v-2 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Culp, John. 2020. Panentheism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, fall ed. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/panentheism/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Darwall, Stephen L. 1983. Impartial Reason. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 1994. Religion in Britain Since 1945, 1st ed. Oxford and Cambridge: John Wiley &Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, John. 1994. The Moral Writings of John Dewey, Edited by James Gouinlock. , rev. ed. Great Books in Philosophy. Amherst: Prometheus Books. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung, Kevin, and Ted Kluck. 2009. Why We Love the Church: In Praise of Institutions and Organized Religion, new ed. Chicago: Moody Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Eatough, Erin. 2021. How Has Belonging Changed since COVID-19? BetterUp (blog). March 12. Available online: https://www.betterup.com/blog/belonging-after-covid-19 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Espelage, Dorothy L., and Arthur M. Horne. 2008. School Violence and Bullying Prevention: From Research-Based Explanations to Empirically Based Solutions. In Handbook of Counseling Psychology, 4th ed. Edited by Steven D. Brown and Robert W. Lent. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 588–98. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Jonathan. 2017. Unlike Their Central and Eastern European Neighbors, Most Czechs Don’t Believe in God. June. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/06/19/unlike-their-central-and-eastern-european-neighbors-most-czechs-dont-believe-in-god/ (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Fletcher, Joseph F. 1997. Situation Ethics: The New Morality. Library of Theological Ethics. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flew, Antony. 1972. The Presumption of Atheism. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 2: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, Warren, and Alexander Weis. 2000. An Ethics of Care or an Ethics of Justice. Journal of Business Ethics 27: 125–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Josef. 1983. Personal Responsibility and Christian Morality. Washington, DC and Dublin: Georgetown University Press; Gill and Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, Carol. 1982. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grác, Ján. 1979. Pohľady do psychológie hodnotovej orientácie mládeže, 1st ed. Bratislava: Slovenské pedagogické nakladateľstvo. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, E. J. N. 2020. Een zinvol leven: een filosofisch perspectief. Barendrecht: Reflectera. [Google Scholar]

- Holy Bible: New Living Translation, Catholic. 2001. Wheaton: Tyndale House.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 2000. Pragmatism and Other Writings. Edited by Giles B. Gunn. Penguin Classics. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 2002. The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature: Being the Gifford Lectures on Natural Religion Delivered at Edinburgh in 1901–1902. Mineola: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Warren, Steven Hobbs, and Don Hockenbury. 1982. Loneliness and Social Skill Deficits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 42: 682–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juvonen, Janna. 2006. Sense of Belonging, Social Bonds, and School Functioning. In Handbook of Educational Psychology. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 655–74. [Google Scholar]

- Koltko-Rivera, Mark E. 2006. Rediscovering the Later Version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Self-Transcendence and Opportunities for Theory, Research, and Unification. Review of General Psychology 10: 302–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2015. Value Systems and Religiosity as Predictors of Non-Religious and Religious Coping with Stress in Early Adulthood. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 17: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitinen, Arto, and Anne Birgitta Pessi. 2014. Solidarity: Theory and Practice. London: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lasgaard, Mathias, Luc Goossens, and Ask Elklit. 2011. Loneliness, Depressive Symptomatology, and Suicide Ideation in Adolescence: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analyses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 39: 137–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Poidevin, Robin. 2010. Agnosticism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Martha Peaslee. 2012. Loneliness and Eating Disorders. The Journal of Psychology 146: 243–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, Michael P. 1994. Pantheism: A Non-Theistic Concept of Deity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lodder, Gerine M. A., Luc Goossens, Ron H. J. Scholte, Rutger C. M. E. Engels, and Maaike Verhagen. 2016. Adolescent Loneliness and Social Skills: Agreement and Discrepancies Between Self-, Meta-, and Peer-Evaluations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 45: 2406–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lotze, Hermann. 1856. Mikrokosmos. Leipzig: Hirzel. [Google Scholar]

- Mander, William. 2020. Pantheism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, spring ed. Edited by Edward N. Zalta Lab. Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/pantheism/ (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Manuel, Frank Edeard, and David A. Pailin. 2020. Deism|Definition, History, Beliefs, Significance, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. March 13. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Deism (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Maslow, Abraham Harold. 1943. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review 50: 370–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maslow, Abraham Harold. 1954. Motivation and Personality. Edited by G. Murphy. New York: Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Meulen, Ruud ter. 2017. Solidarity and Justice in Health and Social Care. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, Daniel L., ed. 2010. Commanding Grace: Studies in Karl Barth’s Ethics. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, John Stuart. 2001. Utilitarianism, 2nd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, David. 2017. Solidarity and Its Sources. In The Strains of Commitment: The Political Sources of Solidarity in Diverse Societies, 1st ed. Edited by Keith G. Banting and Will Kymlicka. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Stuart. 2004. Church After Christendom. Milton Keynes: Paternoster. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, Thomas. 1979. The Possibility of Altruism, rev. ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Leanne Lewis. 2004. Faith, Spirituality, and Religion: A Model for Understanding the Differences. College Student Affairs Journal 23: 102–10. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, Onora. 1996. Towards Justice and Virtue: A Constructive Account of Practical Reasoning. Transferred to digital print. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oostveen, Daan. 2019. Religious Belonging in the East Asian Context: An Exploration of Rhizomatic Belonging. Religions 10: 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oppong, Steward Harrison. 2013. Religion and Identity. American International Journal of Contemporary Research 3: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Over, Harriet. 2016. The Origins of Belonging: Social Motivation in Infants and Young Children. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371: 20150072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Park, Crystal L., Donald Edmondson, and Amy Hale-Smith. 2013. Why Religion? Meaning as Motivation. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline and James W. Jones. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 157–71. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, Daniel, and Monica A. Landolt. 1999. Examination of Loneliness in Children–Adolescents and in Adults: Two Solitudes or Unified Enterprise? In Loneliness in Childhood and Adolescence. Edited by Ken J. Rotenberg and Shelley Hymel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 325–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2021. More Americans Than People in Other Advanced Economies Say COVID-19 Has Strengthened Religious Faith. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. January 27. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2021/01/27/more-americans-than-people-in-other-advanced-economies-say-covid-19-has-strengthened-religious-faith/ (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Pope Francis. 2013. Chrism Mass Homily of Pope Francis. March 27. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/homilies/2013/documents/papa-francesco_20130328_messa-crismale.html (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Pope Francis. 2021. Regina Caeli. April 25. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/angelus/2021/documents/papa-francesco_regina-caeli_20210425.html (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Pospíšil, Jiří, Helena Pospíšilová, and Naděžda Špatenková. 2016. General Attitudes to the Faith, Religion, Ethics and Solidarity among the Czech Adults. Paper presented at 3rd International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM 2016, Albena, Bulgaria, August 24–30; Albena: SGEM, pp. 549–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rokach, Ami. 2002. Loneliness and Drug Use in Young Adults. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 10: 237–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, Ami, and Tricia Orzeck. 2003. Coping with Loneliness and Drug Use in Young Adults. Social Indicators Research 61: 259–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]