1. An Introduction to Gregorian Chant and the Asian Christian Context

Among devout Catholic Christians and the members of the Catholic hierarchy, Gregorian chant undoubtedly holds a special place in the liturgical tradition. In the medieval period, five types of Latin language liturgical music dominated church life (Ambrosian, Byzantine, Gallican, Gregorian, Mozarabic), but the uniqueness of Gregorian chant guaranteed the popularity of this type of chant in the Latin Rite (Roman Catholicism’s demographically most dominant part) of the Roman Catholic Church. This uniqueness comes from the fact that Gregorian chant exists as simple melodies with lyrics in Latin. The chant normally does not involve instruments because of the spiritually ideal notion of a humble and unadorned human voice giving praise to God. Lyrics in Gregorian chant primarily rest upon the literal and implied content of the Bible. The earliest surviving Gregorian chants date back to the ninth century. Although scholars openly wonder about the chants’ links with Pope Gregory the Great (r. 590–604), this origin story has persisted because of the strong power of traditional narratives in Catholicism.

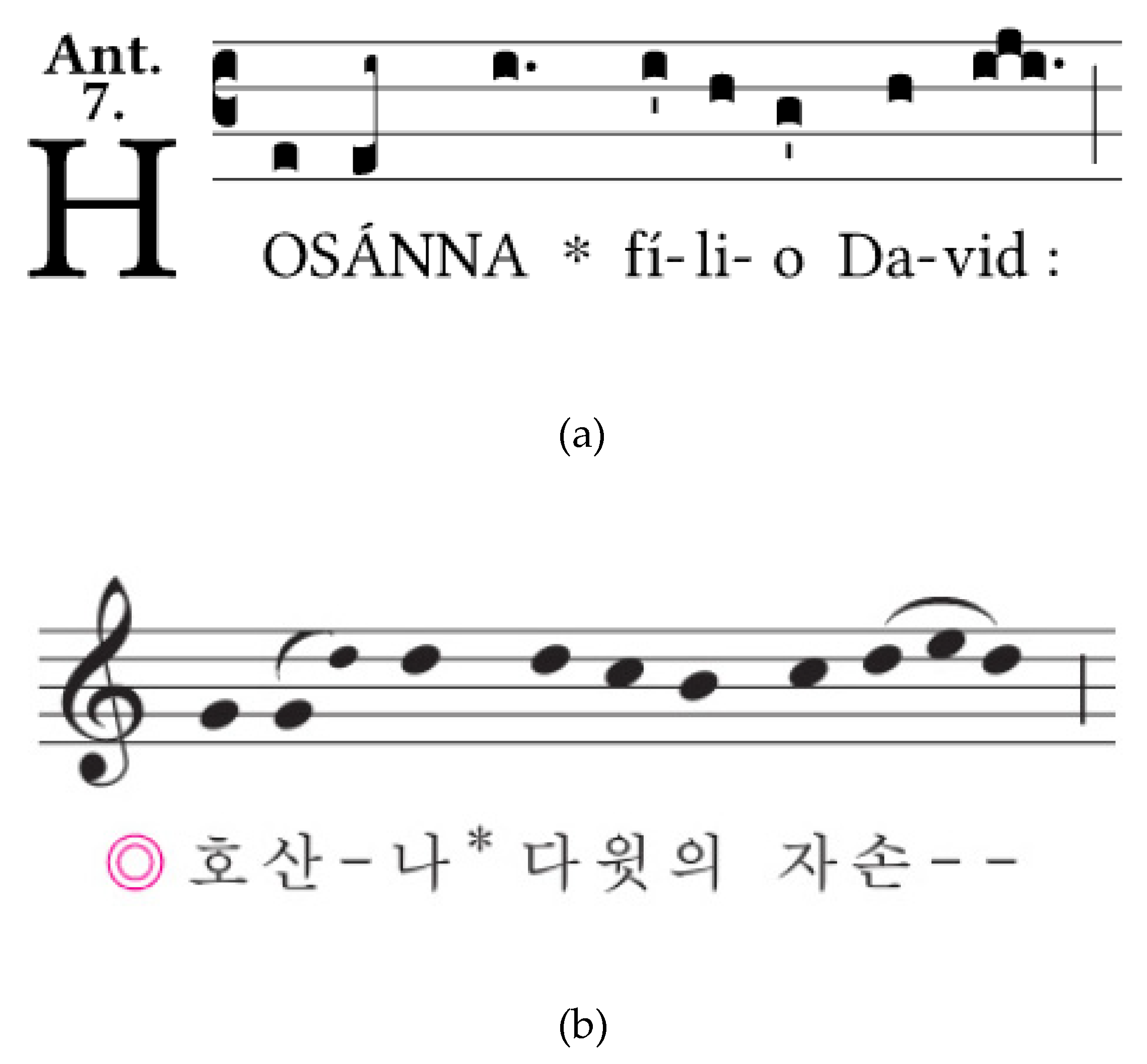

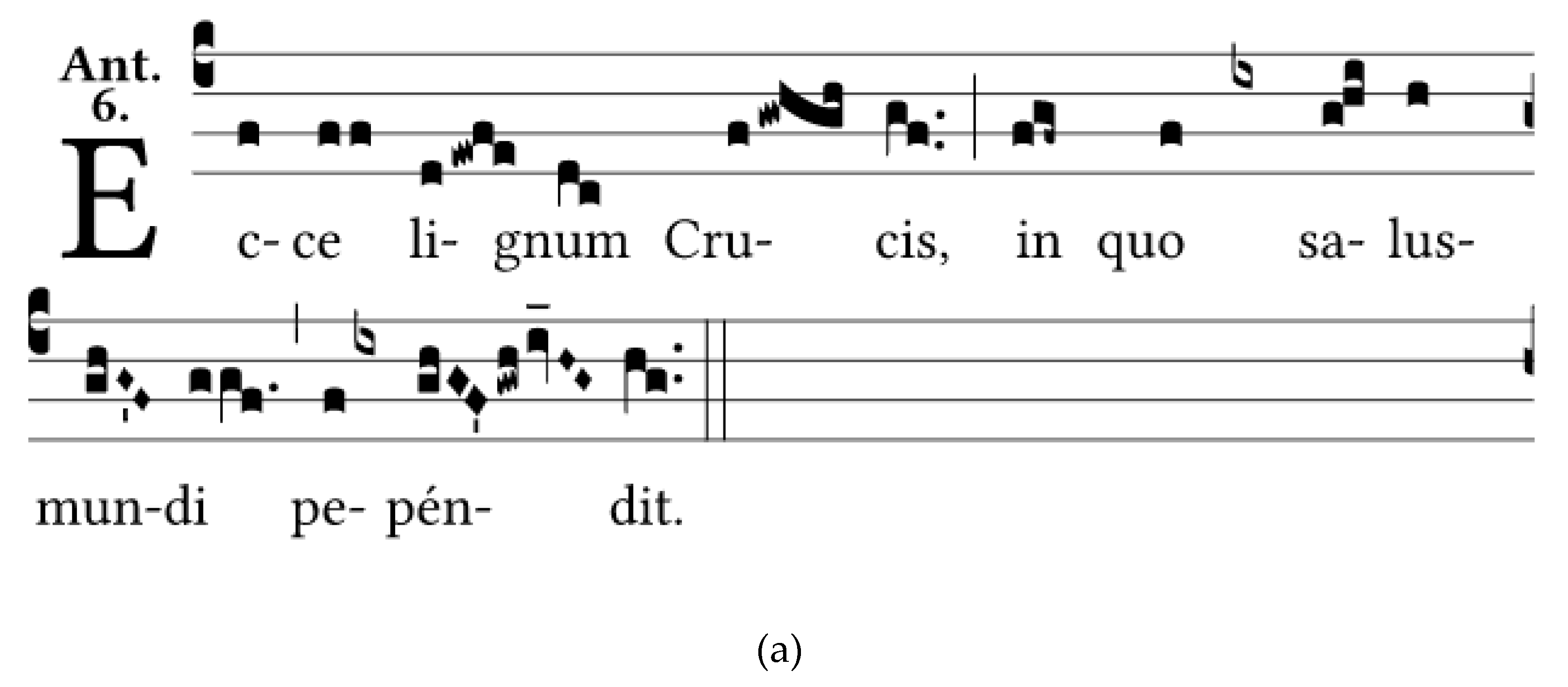

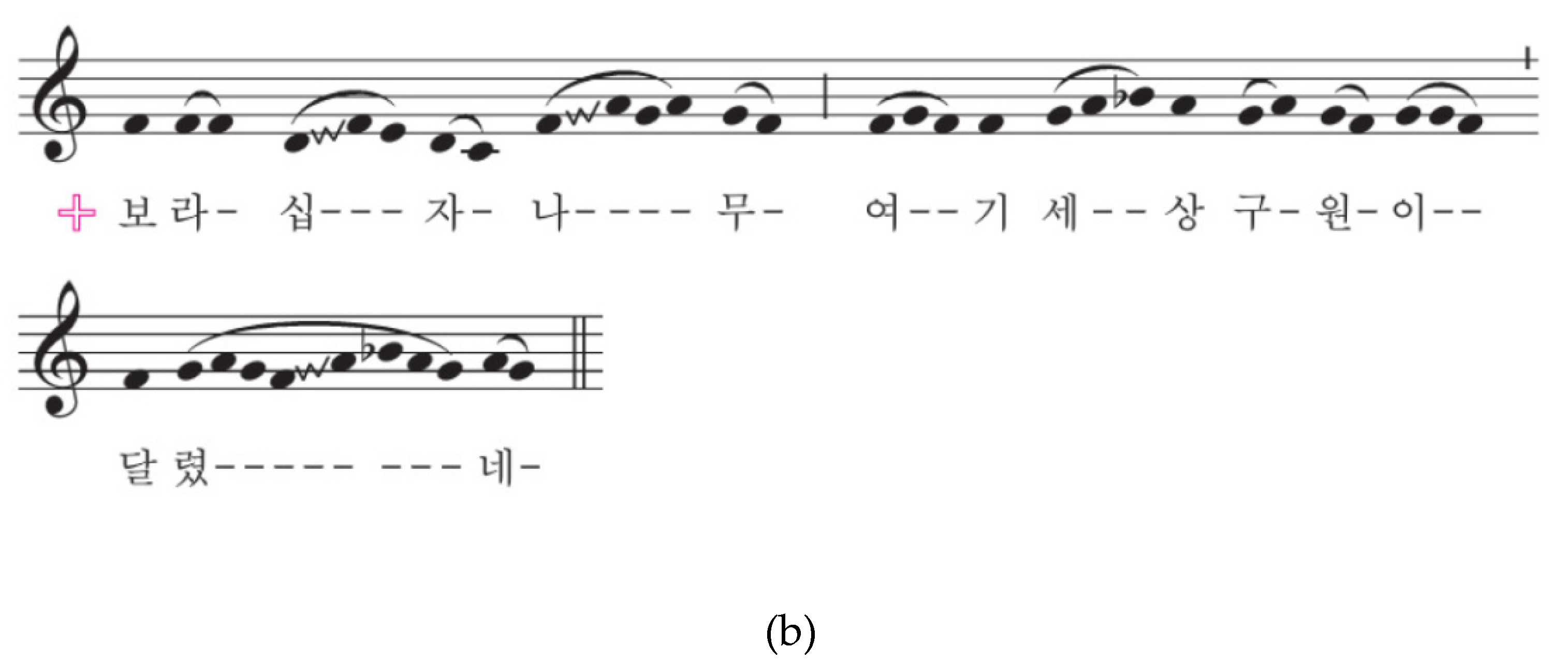

In this article, we intend to tackle certain issues that have arisen regarding the process of localizing Gregorian chant according to the Korean context. We recognize the prominence of scholarly literature that describes Gregorian chant translation processes as processes of indigenization (i.e., efforts in giving a local culture a vast degree of control in adapting Gregorian chant according to the specific circumstances of that culture). This recognition aside, we believe that efforts to translate Gregorian chant into Asian languages seem best characterized as efforts of localization because the Catholic Church has clear standards in protecting the integrity of Gregorian chant, regardless of where the adaptation processes occur. This process of localization not only involves the translation of the words of Gregorian chant into Korean but also entails attempts to reconcile the musical structures of Gregorian chant and the structures of Korean music. The Gregorian chant interpretations of our study will come from the Masses of Holy Week. While research on this topic remains somewhat limited, the conclusions that we have tentatively uncovered nonetheless offer some commentary on the current state and future trends of Gregorian chant translation in South Korea. Protestants outnumber Catholics in South Korea, but as we shall soon see, quite a few Protestants have acknowledged the uniquely Catholic emphasis on things sacred and divine. In a sense, a review of issues relating to the Korean Catholic Church’s use of translated Gregorian chant offers a wider glimpse into the ways through which Asians have attempted to integrate the Latin liturgy into daily spiritual life. The Catholic Church’s issues in accommodating Gregorian chant for Korean audiences resemble similar challenges among other Asian cultures. With these challenges in mind, we will also briefly review the efforts of Catholic missionaries in promoting Latin language translation and the use of translated chants in places such as Japan, China, and other Asian states.

In 1884, Protestant missionary Robert Samuel Maclay (1824–1907) visited Seoul and encouraged the growth of the Methodist episcopate there. While in Korea, he received the monarch’s permission for erecting a hospital and a school (

Gospel in All Lands 1896). With this assurance, the Protestant church in Korea could more easily thrive. These missionary successes also allowed for the spread of translated hymns that included ”Rock of Ages, Cleft for Me (만세반석 열리니)”, as shown in

Figure 1 below. Although Augustus Toplady wrote verse 1 of the hymn in 1776, the Korean translator remains unknown.

- Rock of Ages, cleft for me,

- 만세반석 열리니

- Let me hide my-self in Thee

- 내가 들어갑니다

- Let the water and the blood,

- 창에 허리 상하여

- From Thy wounded side which flowed,

- 물과 피를 흘린 것

- Be of sin the double cure,

- 내게 효험 되어서

- Cleanse me from its guilt and power.

- 정결하게 하소서

For theological reflection, nineteenth-century Korean Protestants may have found inspiration from the lyrics of this hymn, a hymn that might seem like a layperson’s version of the “Ave Verum Corpus” composed by W. A. Mozart (1756–1791) or William Byrd (1543–1623). The hymn also resembles a non-lyric eventide chime melody of “Abide with Me (때 저물어 날 이미 어두니)”, which can serve as the melody for a church bell (

Ingalls et al. 2018). In the narrative of Korea’s encounter with Protestantism, a Protestant feeling of spiritual attraction for hymns essentially Catholic and Latin in origin has resulted in a spectrum of attitudes ranging from sentiments of cross-denominational fraternity (ecumenism, in other words) to desires to convert to Roman Catholicism. Although the early Protestant Christian missionaries in Korea included the famously anti-Catholic Henry G. Appenzeller (1858–1902), other missionaries felt more receptive to the contributions of Roman Catholics. Scholar Richard Rutt has characterized many of Korea’s earliest rank-and-file white Protestant missionaries as deeply impressed with the sacrifices of the Catholic martyrs. These missionaries also deemphasized the distinctions between the various branches of Christianity, perhaps because Korea’s first white Christian missionaries understood the situation of Korea’s tiny numbers of Christian converts relative to the far greater numbers of passionate Confucians or Buddhists who might have wanted to discourage Christianity’s spread (

Rutt 1983). In the fragility of their early years in Korea, Christians of all denominations did not wish to tear themselves apart through pointless theological squabbles. In the modern age, Gregorian chant and the ancient hymns of the Catholic Church have deeply resonated with some Protestants, for whom respect for the Catholic Church can blossom into a decision to become Catholic. Korean academics such as professor Kim Jongseo (김종서, Seoul National University department of religion) have called attention to high reputation of the Korean Catholic Church as a vessel for charity, social justice, and dialogue between atheists and people of faith (

Kim 2010). Anecdotal evidence appears to support the notion of Protestants drawn to the Korean Catholic Church’s nearly irreproachable reputation and reverence for the world of divinely sacred matters. In 2021, the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (Société des Missions étrangères de Paris, or MEP for short) highlighted the story of Korean pianist Cathy Cheongmi Park, who felt distinctly attracted to the solemnity of Gregorian chant and the Catholic mass (

Société des Missions étrangères de Paris 2021).

In contrast to Protestant Christianity that initially came to Korea through monarchical approval, Catholic Christianity came to Korea through a rather different route (

Ruiz-de-Medina 1991). As early as the 1590s, through Jesuit missionary outreach efforts, there existed communities of Korean Catholic Christians exiled in Japan as a result of Hideyoshi’s invasion of Korea (1592–1598). Contemporary Jesuit chronicles describe a Korean-born martyr forced to take the Japanese name of Takeya Sôzaburô Cosme (d. 1619). Shortly before his execution at the hands of the persecuting Japanese authorities, Cosme apparently sang the Latin devotional “Laudate Dominum omnes gentes (Praise the Lord, All Ye Gentiles)” in what a Jesuit observer characterized as the blissful anticipation of a heavenly reward (

Ruiz-de-Medina 1991;

The Golden Manual 1850). Several decades later, Korean envoys dispatched to China purchased a book entitled

Cheonjusilui (天主實義;

The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven) written in 1603 at Beijing by the Italian Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci (

Meynard et al. 2016). The book, which claimed the possibility of reconciling Confucianism and Christianity, became a popular book alongside other Confucian and Buddhist scriptures for eighteenth-century Korean scholars.

At the dawn of Catholicism’s formal entrance into Korea, Korean scholars typically viewed the religion as a Western and therefore foreign belief system called Seohak (西學). Despite this perception, the Korean government led by King Jeongjo (r. 1776–1800) did not explicitly persecute followers of Christianity. The monarch confidently expected his countrymen to reject a Christian faith that supposedly contravened the rational sensibility expected of religions in Korea (

Jeongjo of Joseon 1978). In the spirit of the king’s attitudes, the authorities did not initially adopt draconian persecution measures even after the baptized Korean scholar Lee Seunghoon became the first recorded convert to successfully return to Korea in 1784. In 1785, for example, some policemen incorrectly suspected some Korean Christian scholars of gambling, but the authorities only gave a minor punishment (

Yi 1971).

In the meantime, without ordained clergy in Korea, the earliest Catholics in Korea began to baptize themselves until the Catholic hierarchy had to intervene by saying that such baptisms could not validly occur without the presence of a priest. Tensions between Confucianism and Christianity unfortunately escalated in 1790, when Alexander de Gouvea, a prominent ecclesiastic based in China, disallowed the Confucian ancestor commemoration ceremony among Asian Christians (

Dallet 1874). This event precipitated a major government initiative (the Sinhae persecution) against Korean Catholics in 1791. King Jeongjo’s successor Sunjo (r. 1800–1834) strictly prohibited Catholic Christianity on the grounds of the religion’s supposed opposition to traditional ethics. This prohibition served as the basis for the Sinyu persecution of 1801, and this persecution led to many martyrdoms, including the martyrdom of a Chinese priest, Zhou Wenmo (1752–1801) (

Choi 2006).

Pope Leo XII (r. 1823–1829) later assigned Korean missionary work to the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (MEP). In 1831, Pope Gregory XVI (r. 1831–1846) appointed Barthélemy Bruguière as the first apostolic vicar of the Korean archdiocese (

The Society for the Propagation of the Faith 1832). Unfortunately for the newly appointed ecclesiastic, he died in 1835 and never reached Korea. Fortunately for the Korean mission, three MEP priests found themselves dispatched to Korea shortly after Father Bruguière’s untimely passing. These priests had the names of Jacques Honoré Chastan (1803–1839), Laurent Joseph Marie Imbert (1797–1839), and Pierre Philibert Maubant (1803–1839). Among other intentions, these priests came to Korea with the hope of recruiting Korean seminarians who could study in Macao. Although the missionary trio successfully entered the Korean peninsula, the Gihae persecution of 1839 ended both the hopes and lives of these fathers (

The Research Foundation of Korean Church History 2017). In 1843, as a poignant dedication to his colleagues who died in Korea, Charles-François Gounod (1818–1893), a famous French musician and MEP chapel master, composed “À la Reine des apôtres (To the Queen of the Apostles)”, a piece later retitled as “Chant pour le départ des Missionnaires du Séminaire des Missions étrangères (Song for the departure of the Missionaries from the Seminary of Foreign Missions)” (

Bibliothèque nationale de France 2021). On 17 August 1845, Andrew Kim Taegon (1821–1846), an alumnus of the Macao seminary, became the first ordained Korean priest active in Korea, but his ministry tragically ended in his death sentence at the hands of the authorities (

Kim 1984). In 1886, the situation of Catholics finally began to improve with a “Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation” between the Joseon Dynasty (the old name of Korea) and France. This treaty allowed for the dynasty’s official (if only implicit) recognition of Catholic Christianity (

Korean Mission to the Conference on Limitation of Armament 1922). About a decade later, in 1895, the Joseon state also expressed sentiments of regret regarding the anti-Catholic Byeongin persecution of 1866.

With respect to the evolution of Catholic music in Korea, Choe Yang-Eop (1821–1861), the second ordained Korean priest, wanted to accommodate the illiteracy of Korean Catholics who often lacked access to catechisms, bibles, and hymnals. Around 1850, he began to write religious lyrics named “Cheonjugasa (天主歌辭)”. Since Cheonjugasa listeners usually came from the poorest and most illiterate people, the lyrics had to remain simple so that villagers could easily pass on these lyrics to later generations (

Han 2017). The simplicity of the Cheonjugasa proved attractive to lowborn Korean Catholic converts who sometimes inserted their own simple melodies into the lyrics. Although the musical scores of these lyrics have not often survived, the syncretism (mixing) of Korean religions exists as a fact widely acknowledged by anthropologists, so Buddhist folk songs played a role in the creation of these lyrics. (In this particular case and analogous cases, one can argue that Korea’s religious syncretism indirectly foreshadowed the Second Vatican Council’s initiatives in attempting to reconcile traditional ancient church practices with the practices of local cultures.) As they arranged the Cheonjugasa, Korean converts likely borrowed musical conventions found in preexisting Buddhist melodies. For Korean Catholics, the Cheonjugasa composition processes therefore had some origins in the beompae (범패), or sung lyrics meant to accompany Buddhist dances. Short and simple solo pieces known as hutsori (훗소리) also inspired the Cheonjugasa arrangements (

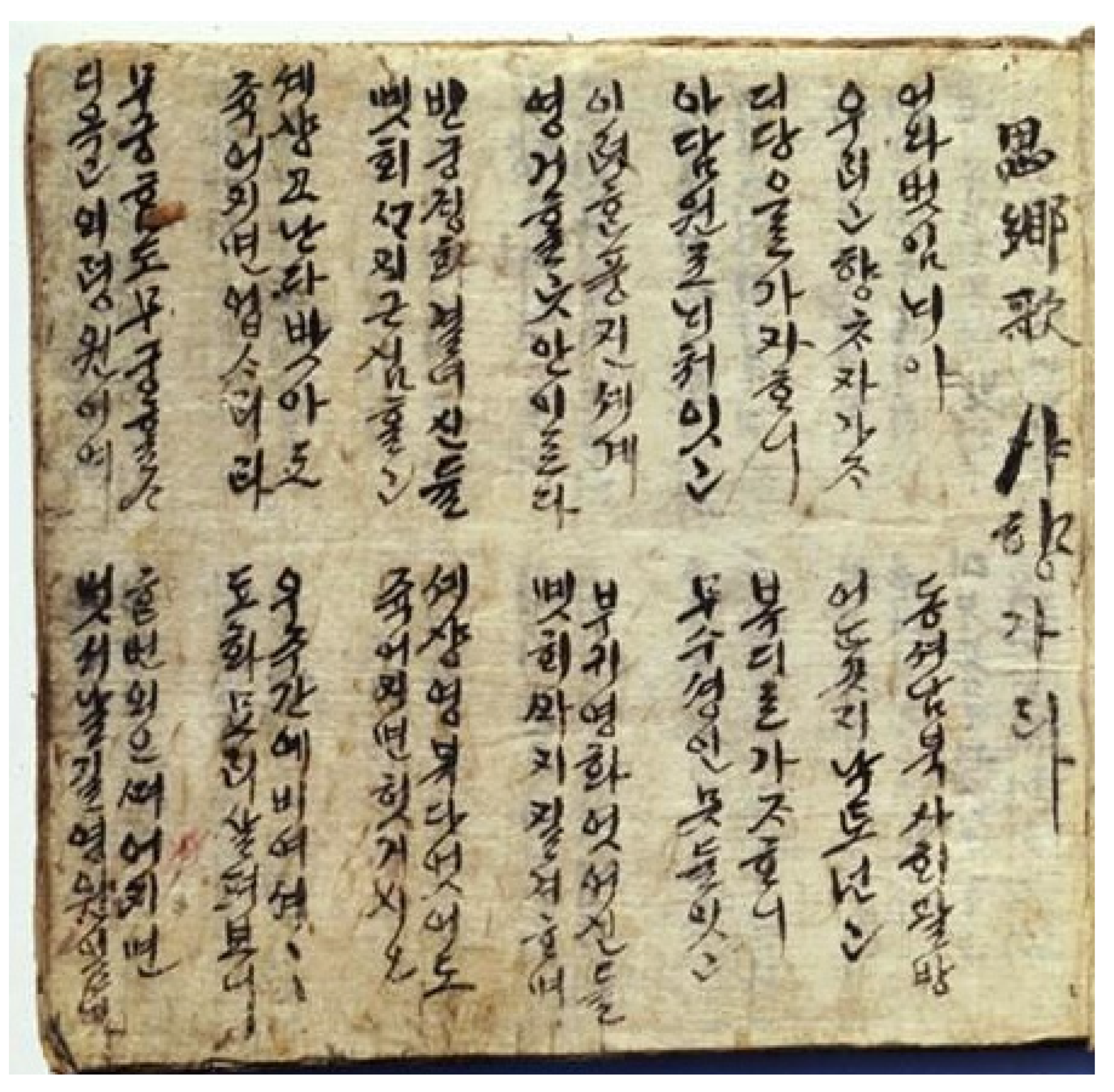

Kwak 2000). In one thematic example known as the “Sahyangga (사향가)” of

Figure 2, the lyrics describe a heavenly home that would greet persecution victims martyred by the authorities.

After the treaty of amity between Korea and France in 1886, the Korean Peninsula’s slow but clear movement towards religious freedom fueled the publication of various Cheonjugasa pieces. According to one Catholic newspaper, themes of sacred lyrics, patriotism, the encouragement of learning, lamentation, and even drinking prohibitions existed within the 41 Cheonjugasa pieces in circulation through the year 1910.

In 1887, the MEP established a seminary in Yongsan, Seoul. At the seminary, priest professors taught liturgy and Gregorian chant (

Kim 1993). In 1892, signs of an even more vibrant Korean musical culture would emerge with the building of Korea’s first Western-style church in the Yakhyeon area. The church’s architecture reflected both Romanesque and Gothic influences. A contemporary document describes a scene of individuals singing the Nicene Creed during the consecration of the church.

In August 1924, the Seoul Diocese published the Joseoneoseongga (조선어성가), the first official hymnal for Korean Catholics. The hymnal provided a five-line staff. Of the compilation’s 68 pieces, 20 songs (from Cantiques de la Jeunesse) had French origins because of the MEP’s then-dominant influences in the Seoul and Daegu dioceses. By 1938, the St. Benedictine Abbey of Wonsan diocese (located in present-day North Korea) would produce another hymnal, the Catholic Seonggajip (가톨릭 성가집). Given the prominence of the monastic order’s German roots, most songs in this book came from Germany. The hymnal also contains Korean translations of German masses composed by Franz Joseph Haydn’s younger brother Johann Michael Haydn (1737–1806) and Franz Schubert (1797–1828). In the composition of their Mass works, Haydn and Schubert had used German texts. The Korean versions of these Mass works therefore drew from German texts instead of Latin ones.

A significant change in Korea’s Catholic musical culture came with the help of Pope Paul VI, who promulgated

Sacrosanctum Concilium (

The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy) on 4 December 1963 (

Documents of Vatican II 1966). The architects of this document intended to reform traditional liturgical texts and rituals in ways more reflective of local cultures. Although Section 36 of the document focused on the need to retain use of the Latin language in the sacred liturgy, there also existed a recognition of the practicality of presenting that sacred liturgy in the vernacular (viz., the common language utilized by the people in local environments). According to the authors of

Sacrosanctum Concilium, that presentation would slowly spread from the readings to prayers and chants. This critical provision acknowledged a long-standing practice done before

Sacrosanctum Concilium, namely, the usage of vernacular translations (and not the original Latin versions) as the foundations of translated chants. Section 118 also encouraged the need for people to participate in liturgical songs (

cantus popularis religiosus), thereby formalizing the sacred liturgy’s transition from a ceremony dominated by the priest to a ceremony that encouraged more participation among the laity. The promulgation of

Sacrosanctum Concilium coincided with the proliferation of popular religious chants in the Korean liturgy, even though some controversy existed over the ambiguity of the Latin term

popularis as having a congregational or secular interpretation.

While Sacrosanctum Concilium reflected a universal church growing increasingly receptive to moving away from the traditionalism of Latin Masses, Section 116 of the document specifically noted the church’s recognition of the intimate relationship between Gregorian chant and the Roman liturgy. Devout Catholics who attend Mass generally acknowledge Gregorian chant’s preeminence and historical roots, roots that arguably date back to the medieval period.

In the Korean church, the language barrier naturally required Korean translations of chants. Historical records appear to credit Father Maubant (the same MEP missionary sent to Korea after the death of the Korean diocese’s first apostolic vicar) with the introduction of Gregorian chant into Korea (

Kim 2013). Awkward tunes and Latin texts of Gregorian chant (to say nothing of ongoing anti-Catholic persecutions) initially hindered the appeal of Gregorian chant among local Korean Catholics. Over time, Korean monasteries ultimately became the centers of Gregorian chant use, even though pastoral liturgies (viz., the most common types of Masses in which laypersons have many spoken responses) did not frequently use liturgical chanting. In the following section, we will introduce some issues related to Gregorian chant translation in the Korean Catholic liturgy, with a special focus on the Paschal Triduum (Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday in Holy Week).

2. Official Instructions on the Church’s Liturgical Music

Because the church acknowledges Gregorian chant as especially appropriate for the Roman liturgy, we would like to first review the church’s official instruction on music in the liturgy. On 5 March 1967, the Second Vatican Council published

Musicam sacram (MS), a document of instruction on sacred music for Roman Catholic liturgy (

Musicam sacram 1967). This proclamation deals with various genres of sacred music, including Gregorian chant (No. 4).

MS specifically provides guidelines for individuals who have roles in the sung liturgy and the times in which those vocalists ought to begin training for these roles. In the sung versions of a liturgical service, individuals with demonstrable talent in singing should enjoy priority in the singing roles. This situation proves especially relevant in liturgies that require professional settings and/or difficult performances (No. 8). Performers should ideally begin their training as early as possible in grammar school (No. 18). MS also mentions the roles of the cantor and musical instruments. Situations without choirs ought to necessitate trained vocalists, and trained individual singers should still have a role to play even in the presence of church choirs (No. 21). In liturgies, instrumental music can serve to help trained vocalists, but this accompaniment should not distract from one’s ability to internalize the meanings of these words (No. 64).

MS also discusses the singing of the ancient daily church prayers known as the Divine Office. Other names for the Divine Office include the Canonical Hours, Liturgical Hours, or Liturgy of the Hours. In addressing the needs of ordained individuals or individuals attending institutions specifically for the purposes of ordination, the architects of MS urge these individuals to sing the Liturgy of the Hours. In such a way, these individuals may more completely invest themselves in the public prayers of the Holy Mother Church (No. 40). While ordained individuals ought to sing the Liturgy of the Hours in Latin, the church allows for other languages among not-yet-ordained individuals who sing this set of prayers (No. 41).

In terms of general instructions, the church acknowledges the various kinds of singing that can happen in liturgical settings. There clearly exists a hierarchical order of priorities in liturgical settings. In a liturgy, the most important singing part involves either the priest singing (with everyone else replying) or the priest and his congregation singing together. Singing parts reserved for the congregation alone or for the choir alone have a clear but secondary priority (No. 7). MS introduces exhortations for everyone to actively sing in a liturgical setting. Sung words ought to include acclamations, responses to priests, responses to prayers, psalms, hymns, and refrains, among other things. While the choir may very well have more dedicated singing talent than the congregation as a whole, the church discourages situations in which the choir alone sings (No. 16). Sundays and days dedicated to feasts and saints should ideally have Eucharistic liturgies with extensive singing parts (No. 27). In another hierarchy of sung parts of the Mass, the church prioritizes words such as the priest’s greeting, the congregation’s reply, Gospel proclamations, prayers relating to the Lord’s supper, and the Lord’s prayer, among other prayers (No. 29).

In terms of sung liturgical settings, MS frequently refers to other church documents to clarify the need to preserve the Latin language in Latin liturgical celebrations. This preservation effort notwithstanding, local church-governing institutions can use the vernacular in situations for which the use of common languages can produce abundant spiritual fruit (more converts to Catholic Christianity, for instance) (No. 47). The church freely acknowledges the potential for Latin music texts as features of both Latin Masses and common language Masses (No. 51). In the meantime, the ideal arrangement for the Lord’s Prayer involves the congregation singing the prayer with the celebrant. Sung Latin versions of the Lord’s Prayer should draw from established and time-honored melodies. By way of contrast, in vernacular renditions of the Lord’s prayer, the church allows local church-governing institutions to make independent determinations on melodies (No. 35).

As composers arrange melodies for common language translations, these individuals should reconcile the needs of musical consonance (spiritually understood as the need for music to sound both edifying and pleasing) and faithfulness to the spirit of the original Latin (No. 54). Local church governing institutions may freely determine the appropriateness of common language translations, even if those translations may not entirely reflect the spirit of texts deeply respected by the church as a whole (No. 55). More recent attempts at melodies for common language texts may provisionally enter liturgical celebrations, but people should prayerfully continue to refine these melodies (No. 60). In specific lands that have particularly unique musical cultures (Africa, for instance), the task for translating sacred music into liturgically appropriate songs should only fall upon specific kinds of individuals. These individuals should possess deep skills in both the Holy Mother Church’s profoundly rich musical traditions as well as the common traditions of those specific lands (No. 61).

In liturgical celebrations sung in Latin, Gregorian chant should have a preeminent role, with other roles dependent on the circumstances (No. 50). The church also promotes the preservation of time-honored sacred music by placing this music at the center of musical instruction in seminaries and other Catholic institutions of learning. Sacred music instruction firmly depends on the study and application of Gregorian chant. In these provisions, the church emphasizes the intimate connections between Gregorian chant and the notions of sacred music (No. 52).

3. A Survey History of Translations of Gregorian Chant into Other Asian Languages

The landmark decisions of the Second Vatican Council had formalized the church’s desire to allow common languages (and not just Latin) to have a greater role in liturgical celebrations. That formalization aside, localization efforts (attempts at presenting the faith in ways more relatable to the backgrounds of local communities) had happened for centuries before that council. Informal localization efforts arguably had roots in the scriptures, since Paul believed in accommodating another person’s background for the sake of evangelization (cf. 1 Corinthians 9:22). In lieu of an exhaustive treatment that would go well beyond the limits of this study, we will turn to a selection of these accommodation and localization efforts in Asia.

Western Catholic missionaries in Asia had long tried to promote the use of the Latin language, since Gregorian chants and the Mass originally came in the Latin language. In 1582, some of the most well-educated Japanese students from Japanese seminaries traveled to Europe and confidently played pieces of Western music there (

Minagawa 2013). In 1619, the above-mentioned Korean martyr Takeya Sôzaburô Cosme decided to sing a Latin devotional before his martyrdom in Japan. Among the Chinese, Luo Wenzao (c. 1615–1691) not only had some proficiency in Latin, but also entered the episcopate as a bishop (

Román 2001).

On the other hand, the Jesuits and other Catholics in Asia did not have overwhelming success in turning East Asian converts into fluent Latin speakers who could confidently sing Gregorian chant. Vast differences exist between Latin and the East Asian languages of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. These differences would have made Latin singing difficult for most (if not all) Catholic Christians living in these nations and other areas of Asia. Although the Portuguese set up a seminary for Indonesian boys to sing Gregorian chant in Indonesia in 1536, and although the Japanese translation (1553) of the Catechism had several Japanese vocabulary words for musical ideas, it seems fair to say that a significant number of converts in sixteenth-century Asia unreflectively memorized Gregorian chants in Latin (

Bramantyo 2018). In more recent centuries, this reality has remained true. As scholar Lalitha Thomas contends, elderly Indian Catholics of the modern era fondly recall singing Latin chants in the Mass, even though the ancestors of these individuals likely had almost no idea about the deeper themes of those songs (

Thomas 2002). From the 1540s to their suppression in 1773, Jesuits wrote about disappointing levels of Latin proficiency observed among East Asian converts (

Boxer 1967;

Brockey 2007). These situations more or less convinced the Jesuits to present religious instruction manuals in local Asian languages that new converts could more easily understand.

In the presentation of Gregorian chant in Asian contexts, the French-born and later naturalized Chinese priest Frédéric-Vincent Lebbe (1877–1940) surely ranks as one of the more famous supporters of that initiative. Like the Korean language, the Chinese language also tends to have fewer characters that represent longer strings of words in European languages, particularly Latin. Father Lebbe could have theoretically preserved the original musical notation of the Gregorian chant, but then the Chinese translation would have not communicated the sense of the original Latin text. He ultimately tried to reconcile the original Gregorian melodies with Chinese interpretations of liturgical music. This reconciliation primarily entailed the deletion of musical notes that he regarded as less critical to understanding the sense of the original Latin pieces. In this manner, the more laconic Chinese translations could essentially fit inside the more abbreviated musical notation. From the liturgical standpoint, the justification of these editorial decisions rests in the fact that Lebbe wanted Chinese Catholics to understand the spiritual importance of the Gregorian chant’s words. Even if the Chinese translation sacrificed (if only slightly) the musical integrity of the Latin original, that sacrifice seemed less important in the hierarchy of Lebbe’s priorities (

Ng 2007).

In other parts of Asia, the Second Vatican Council accelerated already existing trends in the localization of Gregorian chant. For Indians of Tamil Catholic Christian backgrounds, Gregorian melodies sung in the Tamil language had begun to supersede Tamil transliterations of Latin songs sometime around the 1950s. In the council’s immediate aftermath, liturgical songs reflected a middle ground between a totally Gregorian culture and a totally Indian culture, but that state of affairs did not last for long. By the 1970s, the demands of the laity ultimately led to a total retreat from Gregorian melodies in favor of indigenous classical Indian melodies, specifically Carnatic music (

Thomas 2002). In more recent times, however, the Catholic Church has renewed its fascination with Latin as a sacred language critical to the reconciliation of Christian and Greco-Roman ideas. Pope Benedict XVI reminded audiences of Latin’s significance in his establishment of the Pontifical Academy for Latin in 2012 (

Latina Langua 2012). In some areas of the world, this renewed fascination has arguably mitigated a full retreat from Latin in the use of Gregorian chant. The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Japan’s mission statement deeply emphasizes not only the cultural traditions of Japan but also the spirit of the original Latin liturgical texts that include Gregorian chant (

Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Japan 2021).

5. Conclusions

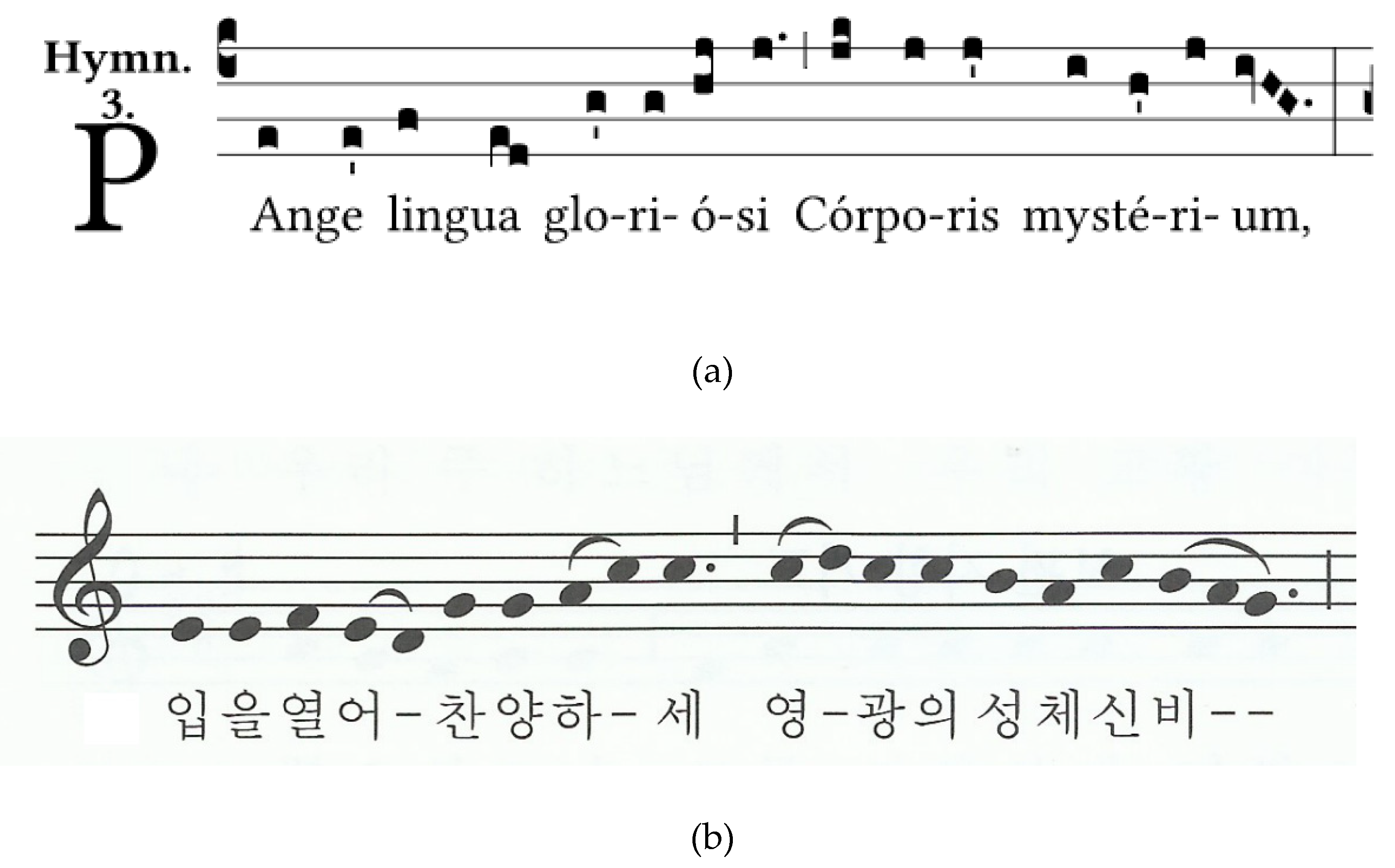

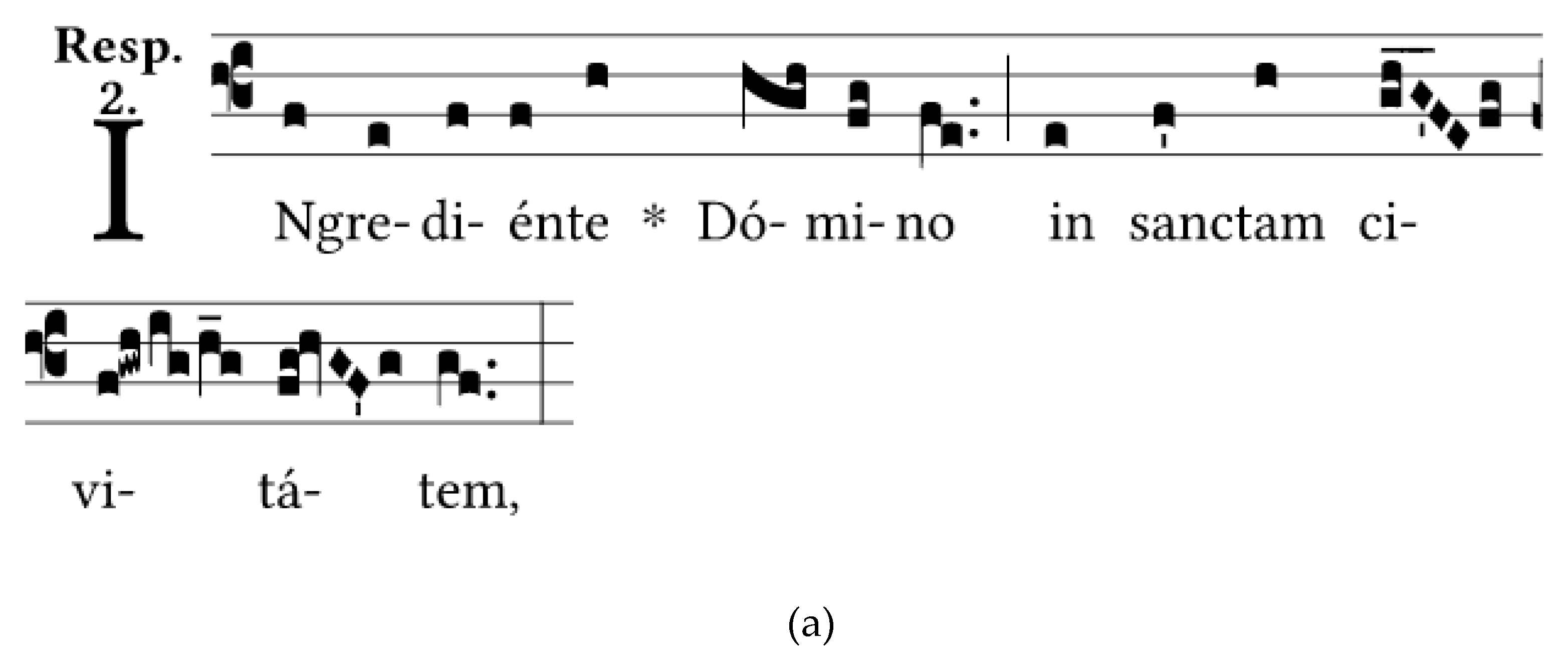

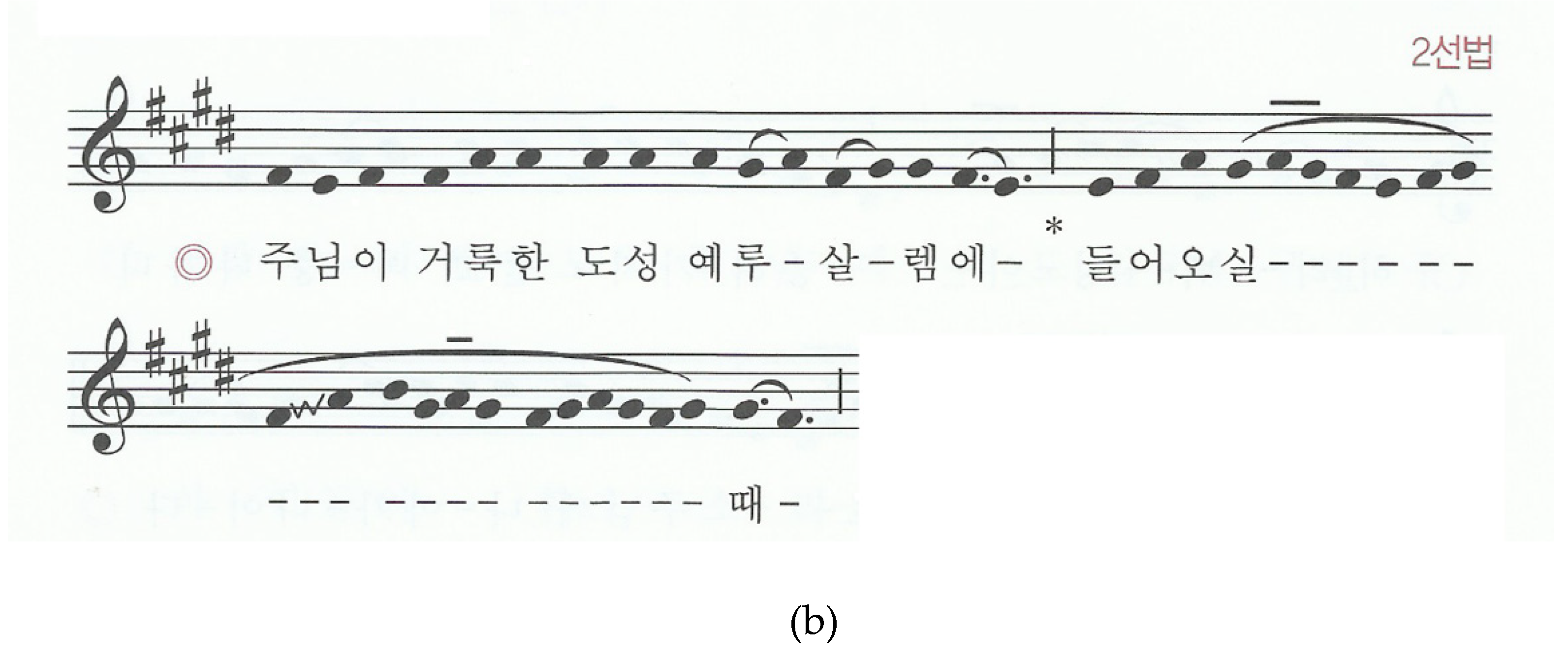

This essay briefly showed the history of the Korean Catholic Church and musical aspects of that history. Our bibliography clearly shows an acknowledgement of helpful insights found in certain sources on indigenization (defined in this context as an attempt to transform an idea into something firmly defined by a local or native people). While authors of these sources clearly saw the translation of Gregorian chant into the vernacular as a process of indigenization, we feel more inclined to characterize this translation process as one of localization. The adaptation of Gregorian chant into common languages does not quite entail a local culture’s unfettered control over how to arrange translations, particularly because the Catholic Church seeks to preserve the integrity of the chant. This article also described some issues that occurred in translating Latin-text Gregorian chants into Asian versions, with a dominant emphasis on the process of translating the texts into Korean. For the Korean translation process, some of these issues included discrepancies in the number of syllables, shifts in melismatic emphasis, difficult diction in vocalization, briefer singing parts because of space limitations, challenging melodic lines, and translation losses from neumes to modern notes.

The understudied nature of research regarding Gregorian chant’s localization in Asia hinders our efforts to paint a truly comprehensive portrait of this topic. This reality seems especially true when we try to explore related issues in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Given the Eastern Orthodox Christian Church’s relatively small physical presence in Korea relative to the presence of the Korean Catholic Christian Church, we expected to find a dearth of scholarship on the monodic Byzantine chant’s musical interpretations in Korea. Even so, we feel that certain similarities between Byzantine chant and Gregorian chant can highlight a degree of helpful cross-pollination between researchers in the Korean localization of both types of chant. Both types of chant probably had a common ancestry in the Church of Jerusalem (

Wellesz 1954;

Jeffery 1992). Both types of chant draw from scriptural narratives profoundly esteemed as sacred wellsprings of truth and edification, and both types of chants firmly exist as unaccompanied music. Both types of chant attempt to liturgically and musically represent the reality of how the Holy Spirit can pray with a profundity that transcends the banality of plainly spoken words (cf. Romans 8:26). These similarities notwithstanding, no scholar should ever try to study the localization of Byzantine chant in Korea as a process indistinguishable from the localization of Gregorian chant in Korea. The peculiarity of Byzantine chant’s musical notation system, a system fundamentally divergent from the modern Western notation system, has served, for instance, to create a unique debate in the world of Byzantine chant; musicologists have argued with each other over the extent to which one should try to fit Byzantine chant within the constraints of Western musical notation (

Barrett 2010).

The realities of our somewhat limited findings aside, we can broadly say that the modern era has witnessed a Catholic Church whose believers increasingly favor the vernacular language and local musical forms over fidelity to the original Latin and original melodies of Gregorian chant. This situation currently persists, even if the highest members of the official hierarchy seem to proclaim the need to reconcile both the sanctity of Gregorian chant and the preciousness of local cultural backgrounds. The search for a possibly more satisfying reconciliation of these two imperatives may have some fruit in careful discernment on fulfilling the spirit of

Musicam sacram (1967), which we introduced in

Section 2 of this essay. The document essentially outlines a vision for localization that entails, among other things, a vigorous reinforcement of Latin as the language of ordained choirs singing the Divine Office, even if the church allows for vernacular Divine Office singing among non-clerics (No. 41). We should emphasize the fact that this process of reconciliation does not exist as some haphazard combination of Gregorian Chant and the Korean language. The architects of

Muscam sacram made careful pains in showing respect for both the timelessness of Gregorian chant and the resonance of vernacular languages and local musical cultures. Even if a musical piece proposed for inclusion in the liturgy seems unsuitable for use in the solemnity of a liturgical setting, the Church remains open to the possibility of that musical piece’s use in popular devotion (No. 53). Given the popularity of creative and private devotions among the Catholic faithful, a Korean musical piece’s use in popular devotion hardly seems to denigrate that kind of music, although opinions on this point arguably vary among rank-and-file Catholics.

Issues in translating Latin-text Gregorian chants into Korean versions may seem greatly significant to the most conservative defenders of the beauty and sacredness of Gregorian chant. On the other hand, these issues may very well escape the attention of most Catholic believers who do not relate to the controlling assumptions of Gregorian chant. These controlling assumptions include the appeal of a universal Latin language revered by the Catholic Church and the appeal of an unaccompanied melody that symbolizes man’s humility and emptiness before the Lord. The anecdotal presence of Korean Catholic Christians weakly instructed in the essentials of the faith may also partly explain why many believers fail to see the appeal of Gregorian chant. In the meantime, we feel that the future of Gregorian chant translation efforts in Korea will continue to depend on conversations between the chant’s most devout apologists and the people who simply favor the usage of contemporary or local musical traditions in Catholic worship. Regardless of the results of these conversations, the ecclesiastical hierarchy will continue to cherish the singular precedence of Gregorian chant in the Catholic liturgy. Many contemporary hymns sung in Catholic chapels reflect the personal beliefs of composers and the musical traditions of particular nations, or so the advocates of Gregorian chant would have us believe. By way of contrast, the Gregorian chant firmly depends on the liturgy’s essence. This essence gives priority to the sanctification of the faithful and the expression of praise and glory to God.