2. Locating the Local

In the introduction of the book

Making Congregational Music Local in Christian Communities Worldwide, Monique Ingalls and her musical scholar co-authors propose “musical localization” as a helpful category because of the way Christian communities take a variety of musical practices and “make them locally meaningful in the composition of Christian beliefs, theology, practice, and identity” (

Ingalls et al. 2018).

Scholarship on India’s local music has covered the wide breadth of Indic music concepts. The father of the significant “theorizing the local” in the Indian subcontinent was

Singer (

1958), who focuses on the urbanized Madras, South India’s “cultural performances” through the “ladder of abstractions” (

Singer 1958, p. 351). Following his footsteps, many scholars sharpened their skills by theorizing the local music of India, arguing for various local perspectives. For instance, in addition to musical phrases, atmosphere, musical space, events, and instruments, “local refers to a concrete locale where musicians make and think about music, such as a venue for performance or instruction” (

Wolf 2009).

Additionally, Indic local music is the hybridity of the Hindu-Muslim religious and cultural system (

Gracin 2011;

Qureshi 1987). Between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries, India experienced Islamic invasions. The twelfth century saw the start of the tremendous outpouring of religious poetry in the erotic Sanskrit

Gita Govinda. During the fifteenth century, a blending of Sufism and

bhakti (devotion) epitomizes the work of Kabir, Surdas, Ramdas, Mirabai, Guru Nanak, and myriads of local poet musicians across the Indian subcontinent (

Ruckert 2004;

Wolf 2009;

Fletcher 2001). Local sound became wedded with central Asian and Persian music. Amir Khusrou introduced

Sufi singing styles and established the

ghazal as a North Indian genre, while

Dhrupad and

Khayal singing developed in Turkish Sultan courts (

Fletcher 2001, p. 234;

Guenther 2018;

Qureshi 1986). By the fifteenth century, the royal court in Gwalior had become a leading centre of musical activity. The famous Mian Tan Sen musicianship mesmerized the Mughal emperor Akbar (

Fletcher 2001). It can be inferred that the Indian subcontinent is where raga-based classical music was heard only in courts and temples (

Ruckert 2004, p. 5). While the social aspect of music entertained elites, sacred music engaged ordinary people in the Indian subcontinent’s spirituality (

Qureshi 2000,

2006;

Ewing 1980;

Wolf 2014). The bird’s eye view of the historical continuity of localized Indic music leads us to navigate the aesthetic theory of Indic music.

4. Indic Music System of Raga راگ

Ragas are generally known as the melodic basis of the classical music of India. The raga resembles a scale in a Western musical system but is also a “meaning system”. A raga is composed of surs (notes or keys on a piano) in a particular scale. Ragas are similar to clay (raw material) from the subcontinent’s soil to be made into a pot on the potter’s wheel of the composer’s imagination. Joep Bor defines raga this way:

Broadly speaking a raga can be regarded as a tonal framework for composition and improvisation; a dynamical musical entity with a unique form, embodying a unique musical idea. As well as the fixed scale, there are features particular to each raga such as the order and hierarchy of its tones, their manner of intonation and ornamentation, their relative strength and duration, and specific approach. Where ragas have identical scales, they are differentiated by virtue of these musical characteristics (

Bor [1999] 2002).

A raga should be no fewer than five notes. There are the following three kinds of ragas: pentatonic (

arruv), hexatonic (

kharruv), and heptatonic (

sampooran). A raga could be described by its characteristics of

arohi and

amrohi—an ascending and descending pattern of sargam, a set of seven notes: Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha, Ni (similar to the Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Ti of Western scales). Five of these seven notes further divide into

surtis (small microtonal units) for a total of twenty-two surtis in the octave.

8 Each raga contains four structural characteristics of surti, sur, vadi, and samvadi. The moveable Sa (

kharaj) is equal to the tonic of the major scale that can be adjusted or in tune according to the preferred pitch of singers or congregation. The raga is a set of notes that express human emotions. The first written treatise on the Indian classical music of ragas and rhythms was compiled by the Indian musicologist Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860–1936).

9 Ragas are classified by different criteria. The following are a few categories: number of notes, time of day, the personification of the principal raga (6 ragas—male, 36 raginis—female), the

thaat system (framework for arranging the seven notes of the scale; Bhatkhande’s system has 10 thaats), and rasa (emotions).

10 Figure 1 illustrates the complex circle of raga classification, which will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

4.1. Classification of Raga and Thaat

During the ninth century, there was a bewildering musical classification system. Music gurus (teachers) introduced the concept of raga and ragini (male and female) from the fourteenth through to the nineteenth centuries. This system consisted of six male patriarchal ragas, each with five or six raginis (wives) as well as sons (putra) and daughters-in-law. This classification also represented the relational and communal culture of Southwest Asia. Ragas were described in terms of the personification of family and community. A third classification was introduced again on the basis of scales, and this classification was adopted by Bhatkhande. His work was known as the most influential and pragmatic raga classification and was based on ten heptatonic scale types called

thaat (framework). According to Bhatkhande, “the thaat is a scale using all seven notes including Sa (first note) and Pa (fifth note). In his system all ragas are grouped under ten scale types, each of which is named after a prominent raga that uses the note verities in question” (

Bor [1999] 2002). The oral traditional music of India is related to the universe’s harmony, in contrast to the structured tonal music of Western tradition (

Begbie 2007). Systems of thaat (ten families of music) for ragas are classified according to categories such as season, feeling, and mood of human nature. They are also classified according to the time of day: For instance, bhairav thaat (early morning raga) is more contemplative and devotional than the friendly and cheerful ragini bhairavi (daytime ragini) or the joyful mood of the evening bilawal thaat in a major scale.

4.2. Taal (Rhythm Patterns)

The sound of Indian drums and rhythm patterns are known for their cheerful and heart-rending emotional effects. The raga music is a mark, identity, and bond for ethnic communities to connect “by virtue of life experience, of certain emotional feelings or meaning associated with that raga” (

Miller and Shahriari 2009). A famous musical proverb says, “A person without melodic understanding or sur (musical note) can sing, but without rhythmic understanding can’t sing”.

Taal refers to tali (clap). The circle of taal starts and ends at the first tali. The completion of the circle is called

sam (a foot of a horse). Usually, taal is accompanied by the tabla, small two-piece hand drums covered with the stretched skin of a cow or goat, and dholak (a cylinder-style drum instrument). The Indian rhythm is complex, and a player uses an additive rhythm in regular, double, triple, and quadruple times. The Indian rhythm and metric cycle classify into 120 taals.

11 4.3. Ragas and the Religious Repertoires

In the context of Hindu spiritual expression, music is one of the vehicles that transports devotees from a state of being that interacts with the natural world to one of engaging the supernatural (

Viladesau 2000;

Gort et al. 1989). In contrast to Western music, which aims to “conquer nature”, Indian music “aspires to the harmony of nature and man” (

Loh 2011, p. 20). The classical raga-based devotional Indic music spectrum “convey[s] meaning” (

Ruckert 2004). Furthermore, ragas are classified into the following two

Prakriti (nature) categories:

ghambir (severe) and

chanchel (light) (

Ruckert 2004;

Wade [1983] 1999). The ghambir nature of raga is related to

bhakti rass, as mentioned earlier. The bhakti (worship) movement in the fifteenth through to the sixteenth centuries produced myriads of

bhajan,

kirtan, and

Sufi songs (

Qureshi 2000,

2006;

Ewing 1980;

Wolf 2014;

Guenther 2018). The emotive expression, “tangible manifestation of the affect” or mood of the raga attracts the audience and authenticates the artist (

Ruckert 2004). A musician composes a melody according to the emotional requirement of the text or occasion. A devoted disciple of the local music spends years engaging and experiencing the expression of the raag.

For Christian congregational music, the Methodist mission produced a repertoire on “the styles of rhyme peculiar to [Urdu]” and North American Presbyterians in Punjab published

Git ki Kitab and

Punjabi Zabur: Desi Ragan Vich. However, the hymn book contained “only the lyrics of the hymns,

bhajans,

ghazals, and Sunday School songs in the Christian tradition of India” (

Guenther 2018). The delineation of these categories expresses that localized Christian congregational music converges with their religious counterparts. For instance, the Shi’as

marsiya/soz share the congregational element, the Sunnis share the content of praise, and the Sufis share the use of musical instruments. One aspect that binds all the religious traditions in the Indian subcontinent is the shared heritage of music. With this background of the local music and religious repertoire in mind, we can specifically explore the convergence of Psalm 24:7–10 in its expression of messianic hope and missional engagement. Departing from the aesthetic theory of rass, ragas, and religious repertoire, the Punjabi Psalter’s story helps us explore and analyze Punjabi Psalm 24:7–10.

5. The Punjabi Psalter

Scholars have distinct perspectives about the localized religious repertoire. For instance, hymn books seem to be a tool “completing the circle of dialogue and conversation” (

Guenther 2018), while the use of Punjabi psalms is a “process that is dialectical, synthetic, and hybrid rather than one limited to appropriation and indigenization” (

Cox 2013,

2015). The first Punjabi psalm was introduced to the Western world by D. T. Niles. He used the melody of Punjabi Psalm 145, “Maharban, Maharban, Maharban”, which means “gracious, gracious, gracious” (from verse 8, NIV).

12 This melody was adapted by Niles and translated into Tamil with the words of Psalm 61 in Western music notation. I-to Loh also introduced melodies from the Punjabi Zabur (22:22–31, 32:8–11, 72:17–19, 84, and 100) into the Christian Conference of Asia (CCA) hymnal. Loh states, “Psalm singing has been very strong in the history of Pakistani churches, and most of these texts were set to traditional or folk melodies. This points to the possibility of a huge repertoire of contextualized psalmody in Pakistan that awaits further investigation” (

Loh 2011, p. 335). Emily Brink reflected on psalm-singing after she visited Pakistan in 2009 and stated, “North America is a literate culture, and we use musical notation in hymnals. But most Pakistani Christians are illiterate and sing by rote” (

Brink 2015, p. 16).

The Punjabi Psalter has been a successful endeavor to break the mold of Western Christianity, shaping Christian worship to be more relevant in the localized music context of Pakistan (

Loh 2011, p. xv). The Punjabi Zabur (Psalms) as a book is called the “Bible of the Illiterate” in Pakistan. The first edition of the Punjabi Psalter was published in Banaras, India, in 1908 with Western musical notation and Roman Punjabi dialect. The purpose of this publication was theological rather than musical. The focus of the Punjabi Psalter was the accuracy of the text and the fervency of spirit. Thus, in translating the Psalms into lyrical Punjabi, similar to translating from Hebrew into metrical English, “the primary aim was a literal rendition of the meaning, while poetical form was of minor concern” (

Jamison 1958, p. 121).

Translating and composing Psalms in the native language was developed to sustain the religious life of both the missionaries and the converts. Until 1883, the worship community in the Punjab region was dependent upon chants or a few metrical versions published in the book of

Zabur aur Geet (Psalms and Hymns) by other missions (

Stewart 1896). However, there were only a few pieces, and they did not correspond very closely to the original. Therefore, the Presbyterian mission decided to produce a separate worship resource. Before 1882, however, little progress was made, “partly because those interested in the work oscillated between the adoption of Eastern and Western meters” (

Stewart 1896, p. 303;

Guenther 2018). In 1882, the Psalm Committee was commissioned by the Presbytery to prepare a first version in Western meter. By October 1891, all 150 psalms had been published in Persian character, and subsequently, they also appeared in Roman script (

Stewart 1896, p. 303). Imam ul Din Shahbaz (1845–1921), a gifted poet and a convert from Islam who worked in an Anglican church, was appointed to translate the book of Psalms into poetic form based on Urdu, Persian, and English. The chairman of the Psalm Committee and others rendered assistance to confirm the exact meaning of the original Hebrew. Shahbaz worked so hard that he lost his sight in the middle of the project. However, his passion was so great that he continued with the help of a young companion, Babu Sadiq. When his translation work was eventually compared with the Hebrew, it was found to be so excellent that it seemed God had given the psalms in the Punjabi language. Stewart noted, “These Psalms have given us great aid and satisfaction in the ordinance of praise” (

Stewart 1896, p. 303).

The next phase of the project was the musical composition in native meters and melodies of these lyrical psalms. It was found necessary to prepare versions of the bhajan form, and that too in Punjabi. Meanwhile, in 1890, the mission appointed a new committee composed of all American missionaries, with the Rev. D. S. Lytle as chairman. Soon the committee realized that without native help they would be unable to finish the task.

Stock (

1968) states that long hours were spent in the marketplaces and cafes listening to current Indian tunes. Shahbaz than paraphrased these psalms into Punjabi verse to fit the meter of these indigenous tunes. It was an indigenous approach with familiar tone and rhythm patterns. This monumental effort was begun in the 1890s and completed in 1910. As already stated, all 150 psalms were translated and lyrically composed by Imam Din Shahbaz, a Muslim convert, born in Zafarwaal, a UP mission station in Punjab in Pakistan. A Hindu musician named Radha Kishan composed the raga-based musical setting of this Punjabi Psalter. An attempt was made to translate it into the Urdu language first, but it did not succeed because the majority of converted people belonged to the Punjabi ethnicity. The committee of the Punjabi Psalter decided to translate the Psalter into Punjabi lyrical poetry to provide a worship resource for these former Hindus. Most of the tunes were not treated as a musical interpretation of the text but were only composed for the sake of keeping the text.

The method of obtaining and adopting local tunes (public or folk raga-based songs) was opposed because of the original lyrics associated with those tunes. It was feared that people might remember the former “filthy words”, which would prove detrimental to both worship and witness (

Stewart 1896). Surprisingly, the former lyrics soon faded away from their memory and the worship community accepted the rich heritage of indigenous tunes set to the “mighty themes of the Psalms” (

Stewart 1896). In 1893, the first edition of Psalms published fifty-five selections of psalms with music. Lytle was responsible for the notation of most of the music, “the airs [melodies] being such as he found already established in the songs of the people” (

Stewart 1896, p. 304). These Indian raga-based, bhajan-style psalms became the power tool for both religious instruction in village congregations and evangelistic campaigns at melas, or in bazar work (

Stewart 1896;

Stock 1968). Stewart expressed his views about these bhajan-style psalms in the psalter:

Yet, some of its tunes are most delightful. Their very weirdness, wildness, plaintiveness and curious repetitions chain the attention and entrance the heart even of a foreigner, and to a native are as irresistible as the songs of paradise. Of some hill airs [ragas] introduced into a new edition of a Hindustani tune book, containing bhajans and gazals, the preface says, “…” Indeed, were it not for the popular songs which it has produced, Hinduism would be shorn of half its power.

Fred Stock wrote:

It is difficult to estimate the spiritual impact of such a treasure of Scripture set to music and words readily understood and appreciated by the masses. Not only did it provide a medium for more meaningful worship, expressing praise, adoration, thanksgiving, confession, and consecration, but it was easily memorized Scripture with power to guard the heart from temptation and sin.

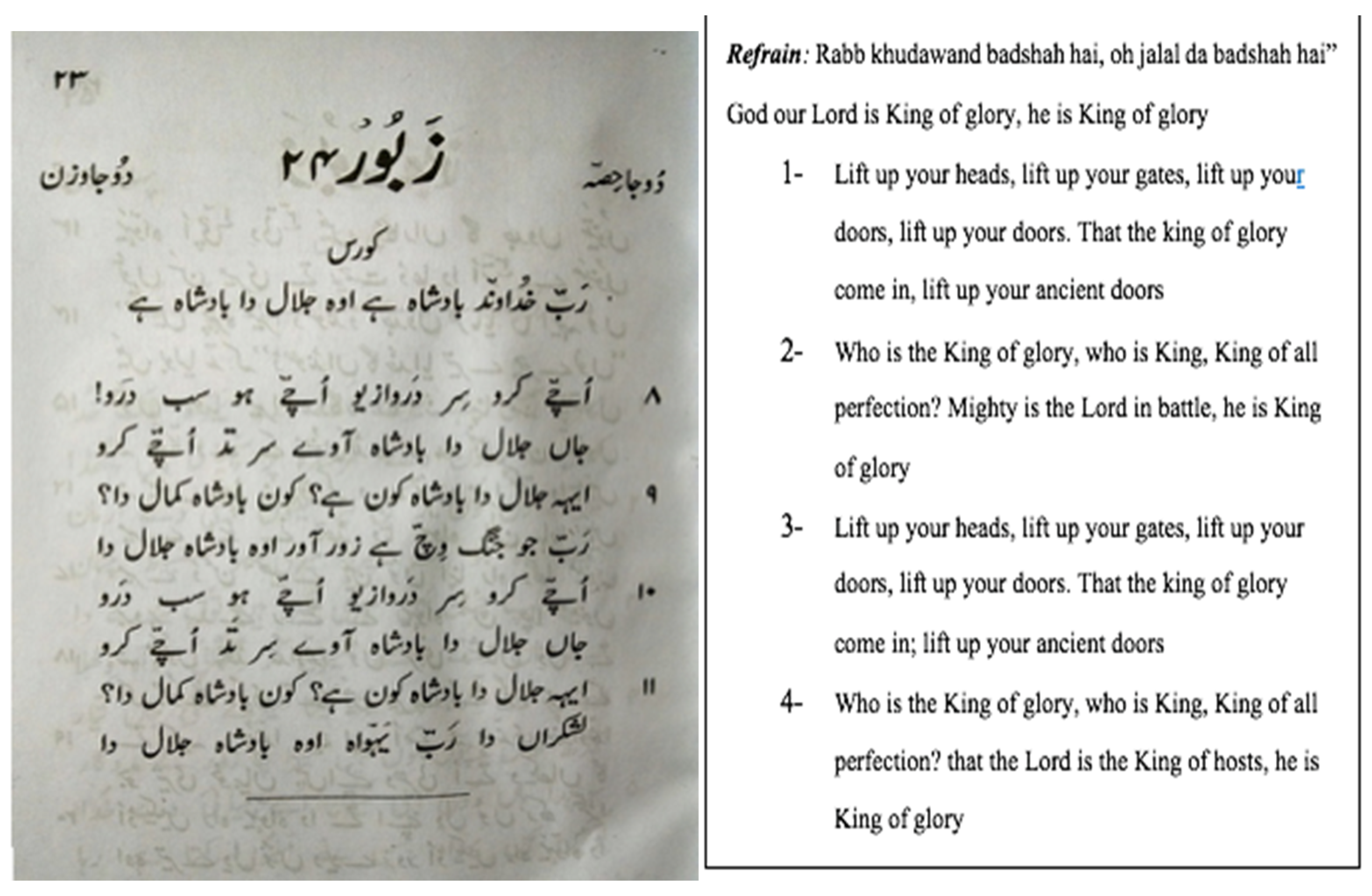

Even after a century, no one has found any poetical or theological problems in these translations. The Punjabi translations of Psalms (Zabur) were formed into 405 parts, all using the same meter, and composed in indigenous ragas: Musical scales were the bulwark against Western hymnology and gave voice to local people to sing in their heart language and lyrics in the simple cadence of rote memory. I. D. Shahbaz, the Punjabi Psalter translator, beautifully paints the textual picture from Psalm 24:7–10 to evoke a sense of God’s kingship.

13 The versified text is crafted as couplet stanzas and refrains in the genre called

Geet and

Ghazal. Almost all the modern published hymnals in Pakistan contain the Zabur 24: 7–10.

The analysis of Psalm 24:7–10 reveals that Pakistan’s sacred soundscape is multivalent. Nevertheless, devotional and emotive aspects are dominant in the Indic music (

Neuman 1990;

Ruckert 2004;

Wolf 2014). Moreover, it uses double discourse: The inclusion of this mixed-Indic sound and Psalm text (as sacred scripture) creates

sur-sangam: combined art (poetical and musical) to open doors for identity, messianic kingdom, and missional engagement. Above given (

Figure 2) is the title cover and a staff notation of the traditional Punjabi zabor 24. Given below (

Figure 3) is the lyrical poetry and English translation of the Punjabi Zabur 24. Amidst the loss of more than 300 local musical settings, the traditional tune and the text of Psalm 24:7–10 were kept alive in the rubble of history.

During the past two decades, three versions of Psalm 24:7–10 emerged: a new composition by Subhash Gill,

14 a traditional tune by Hammad Baily,

15 and a contemporary choral piece by Lew the Twins.

16 The following is an analysis of the traditional tune by Baily and the new musical setting by Gill.

6. Traditional Tune of the Punjabi Zabur 24:7–10

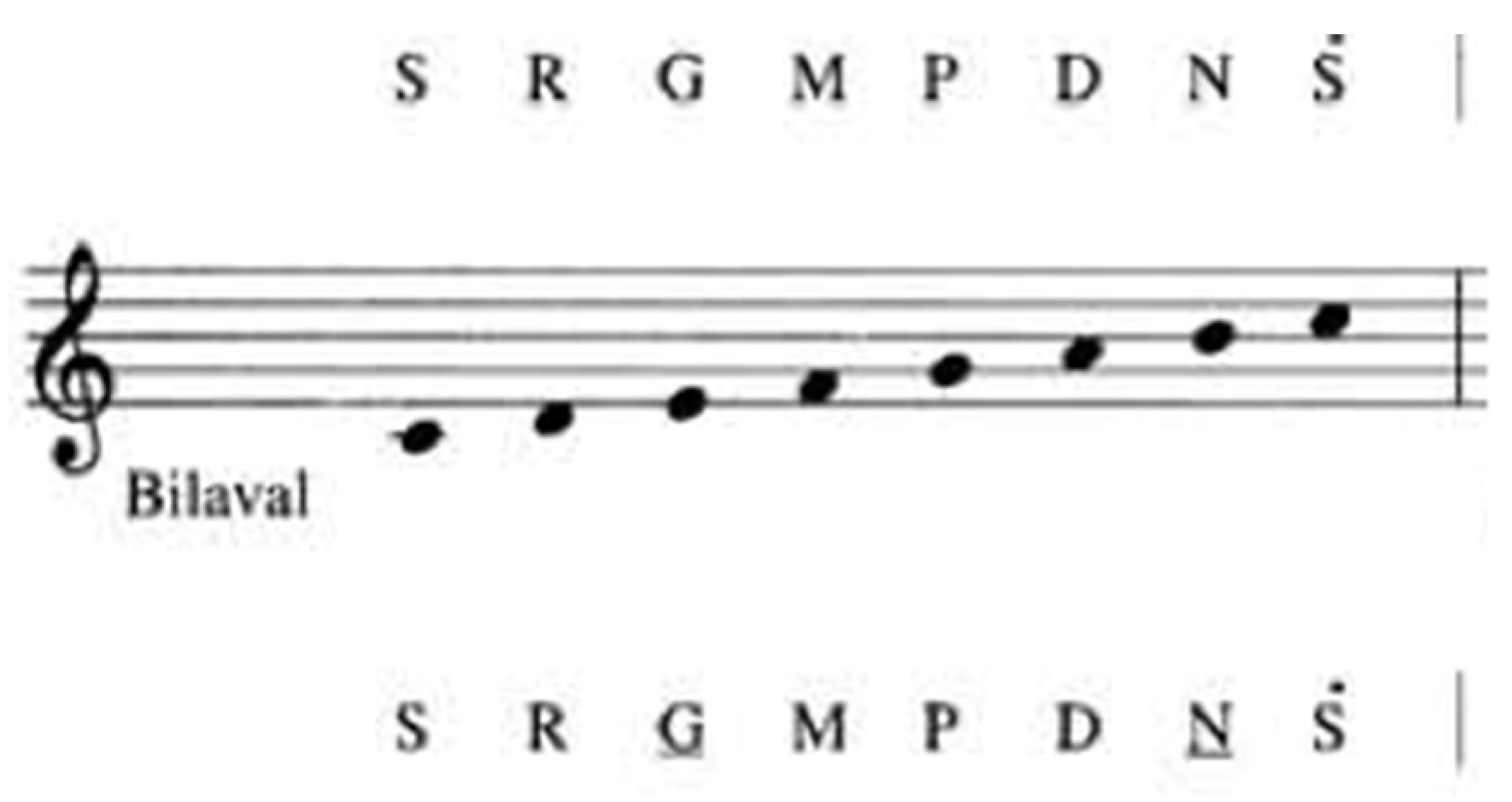

The traditional tune of 24:7–10 is composed in raga

Bilawal. Bilawal is the sweetest, most compassionate, and best-loved raga in Indian music (

Bor [1999] 2002). This

shudh sampoorn raga (major scale of seven notes) corresponds to the Western natural scale in an ascending and descending pattern. This raga is used to express devotion and deep love.

17 The Bilawal family is still used to sing Sufi and folk songs, and it is also famous for light film songs. The music notation (sargam) of raga

Bilawal (tabl) is given below (

Figure 4). Traditionally, the time of this raga is the evening. Nevertheless, it is an accepted norm and is allowed to be sung from dawn to dusk for any purpose.

18Pakistani singer Hammad Baily renders this tune’s recent modification with a brass band, which enhances the majestic, glorified, and massive nature. Due to the flexibility of rules in performance, the singer used the F# (first black key in a set of three) in this melody but beautifully used the rest of the six notes in this tune. The refrain of this tune is simple, sung in a unison chant, keeping singers at the second half of the scale on high notes. The emotional mood of this tune raises the devotional and compassionate feeling of the congregation. It has a distinctive mood, and its characteristic melodic phrases allow singers to move quickly on notes, and all the voices can sing together. The singer’s joyful chant invites other voices to join in harmony. The first stanza starts from an E-flat note, right in the middle of the scale that leads to the third part of the tune at B-flat, which is higher than the first two parts. The third part infuses the energy and joy in singing to return to the home key on the refrain on a lower note. Following the demand of the text, this tune weighs on the second part of the scale, which helps singers lift their voices on the high notes. The climax of the tune descends to B-flat and jumps toward the highest point. After responding to the first part, the tune glides down speedily to the refrain as if the singers were rushing to the King’s throne. The joyful intensity of this melodic structure motivates the congregation to express their devotion with exuberant reverence and hope.

Tune Variations: The traditional tune is divided into five parts and sung in unison.

A—Opening chant with the singer accompanied by the brass band: “Who is the king of glory?” Congregational harmony: “Who is the king of perfection?”

All together: “Mighty is the Lord in battle, he is King of glory.”

B—Refrain by trumpet: “God our Lord is King of glory, he is King of glory.”

C—Refrain with rhythm and full band:

D—Verse 1/refrain

Verse 2/refrain

Verse 3/refrain

Verse 4/refrain

E—Psalm ends with repeated refrain

The congregation sings verse one in unison and repeats it twice. The third part of this tune is sung—or played—on high notes, which infuses spiritual energy into the congregation. The tune is circular and a response to the phrase “God our Lord is King of Glory”, which evokes unimaginable strength and power. The practice of unison singing gives singing space to everyone. By the time the text proclaims and answers the questions about the King of glory, the climax becomes the loudest. Since the second part of each verse comes full circle to the strength of the reign of God, the percussive beat embellishes the melody and uses the same descending beat for an extension to the ending, allowing the music and the voices to wind down slowly. The third part of each stanza is sung on upper notes that find their flow in rhythm and brings the feel of connectivity with the whole piece. The rhythmic beat rolls the tune, and a little syncopation in the melody accompanied by underlying forte enhances joy. The expectation and hope help to illuminate another facet of God’s reign, also serving as a contrast in mood, texture, and dynamic to the first and third variations of the melody.

Culturally, congregations sing this tune without any interlude. It is sung as a whole piece of music that creates space for the congregation to dwell on the words they have just sung. Psalm 24:7–10 gives the sense of a royal wedding, as posed by Hammad Baily in his video. It invites everyone to the banquet and welcomes those who accept that invitation. By using the image of a traditional Indian wedding, Baily produced a music video of this traditional tune in his small village of Pakistan with a brass band to express the wedding of the Lamb (Revelation 19:7–10) in a broader Pakistani context.

7. New Contemporary Tune by Subhash Gill

The early 1990s brought two new names of Christian gospel singers who impacted the gospel singing ministry in the Indian subcontinent: Ernest Mall from Pakistan and Subhash Gill from India. Gill is a composer and singer, currently residing in the U.K. Despite how most Punjabi congregations still love to sing the traditional melody of Psalm 24:7–10, Gill’s 2003 contemporary version has gained the same fame among the congregations. This tune was recorded on his sixth album, “

Sana Gao” (Sing Praises). Gill chose raga

Bheempalasi, one of the ten significant families of Indian ragas. “Raga

Bheempalasi is for the very late afternoon, when the sky is red, and all the animals are basking in the last sunshine” (

Ruckert 2004). The melodic structure of Bheempalasi contains a penta-hexa-tonic style, five notes ascending and seven notes descending in this melody. Most often, this raga is used for singing folk and Sufi poetry. The raga mood is sad and represents the expectations of a reunion after the absence of a beloved one. This expression raises hope and expectancy to console desire and longing during the length of separation, pain, and loneliness. The music notation

(sargam) of the raga Bheempalasi (

Figure 5) is given below.

An essential component of Hindustani music involves a direct relationship between the verbiage of the melody and the underlying structural rhythms (

Gracin 2011). Depending on several factors, such as the genre, the raga, and the composer’s musical mastery, the degree of the relationship between word boundaries and syllables and the resulting rhythm can vary considerably. Gill explains that he chose this text for the following two reasons: first, theological themes of kingdom and glory, and second, the availability of the text in the native language. The melodic pattern moves the congregation to celebrate and shout for joy in the presence of the King. Congregations in Pakistan love to sing psalms and songs with an upbeat rhythm to engage people with clapping and dancing. The tune and text have a sense of prestige and prominence. It starts with the repetition of the word

Badshah, which means King. The introduction starts with an upbeat rhythm pattern of ostinato. The cycle of the anthem chants runs four times. Using the C-minor scale, the word

Badshah starts from a set of three notes (E-flat, F, and G), then a second set (F, G, and A), and a third set (G, A, C–B-flat), and the fourth set glides with A, F, and G notes. The theme is divided into three stand-alone variations, each reflecting on the text of the verse.

Variations:

Introduction—Tabla/dholak, djembe or electronic drum with claps: Ostinato four-beat rhythm.

A—Leader recites Badshah (He is King) four times.

B—Leader: Rabb Khudawand Badshah (Lord our God is King); congregation repeats.

C—Leader sings first stanza; congregation repeats (all four stanzas in the same pattern).

A—Psalm ends with the repetition of Badshah.

The confluence of text and tune (Psalm 24:7–10) accompanied by an upbeat rhythm pattern transforms the sad mood into joy and hope. This peaceful and tranquil mood holds the victorious textual concept of the heavenly King and court. The fluidity of the concluding part allows us to use other titles of Christ, such as “Messiah is King, Christ is King, Healer is my King”. High notes and upbeat rhythm patterns both support each other, adding joy and happiness to singing. This text and tune bring hope to believers’ hearts, and they sing with the anticipation of the coming King. The repetitive refrain “God our Lord is King of glory” reminds of God’s victory again and again.

10. Psalm 24 and Messianic Hope

Psalm 24 is well suited for a festal procession, particularly for a “liturgical and ritual purpose” (

Mowinckle 1967; Witvliet 2015). The text of Psalm 24:7–10 evokes a perspective of Jesus’ victory over death and the anticipation of his coming kingdom, while an imaginative picture of this text is majestic, royal, and strong (

Goldingay 2006;

Lamb 1962). The dynamic cohesion between form and content gives additional space for the composer to design a more musical expression. The anticipation of the coming kingdom invites the community to participate in the hope-filled dialogues through the text. The present continuous tense of “God our Lord is King of glory, He is King of glory” affirms the reality that God hears the cries of his suffering and persecuted children, and he is coming to redeem all that is wrong in creation, while for Christians, it is vastly important to recognize Christ as the glorious, perfect King and the Lord of hosts in the Zabu, the imperial nature of the text supports the form of praise. One of the reasons Psalm 24:7–10 has influenced such a broad array of congregants is the universal subject of the kingdom of heaven and eschatological hope. It emphatically inspired the theme of the “already but not yet” reign of God. During Skype interviews with both Pakistani gospel singers, Gill and Baily affirm the “majestic, massive and glorified” sense. The poetical rhyming paves a path to the raga-based melodic and rhythmic analysis of Psalm 24:7–10.

Regarding the messianic kingdom, there is an unresolved tension between the present and the future, manifest in the continuous tension between the “already” and the “not yet” in Jesus’ ministry (

Bosh 2014;

Slotki 1932;

Smart 1933). The liturgical purpose of Psalm 24 extrapolates to Christ’s kingdom. Psalm 24:7–10 expresses the cultural and historical impact of emperors and kingdoms in India (

Wolf 2009,

2014). The most critical aspect is imagining the messianic kingdom, in which longing and hope of faith have prominence. In the psalm (touching home keys in singing), each stanza returns to the refrain and speaks of a final point of arrival in the kingdom of God. The combination of emotions, pitch, dynamics, and rhythm pattern expands the vision of the kingdom. The psalm’s imaginative spectrum is full of court, gates, King, doors, army, and guard imagery of the kingdom and is associated with majestic and royal occasions. The musical setting gives hope that there is a distinctly local, profoundly contextual vision of a kingdom in which God’s reign is articulated in the local musical language. Singing Psalm 24:7–10 expands the messianic hope for the successful worship transition from one generation to the next. Both tunes connect the two ages of past and present that draw people deeper into union and communion with God in the expectation of the imminent

parousia of Jesus Christ. The hope of the messianic kingdom strengthens the faith of the marginalized.

Additionally, the classical double art form of poetry and music in Psalm 24:7–10 invites us to inhabit and celebrate at the intersection of God’s world and our world. N. T. Wright assured that “the words and music themselves are simultaneously acts of worship and expressions of worship itself” (

Wright 2013). Psalm 24:7–10 has a messianic meaning that points to the coming of the perfect King, Jesus Christ. Amidst threatening attacks and fears from within, celebration and sorrows stand together in God’s throne room. The local form of the ancient song is wedded to ancient raga for a new meaning and a new creation. The joyful music of Psalm 24:7–10 transforms the grievances, anger, and resentment into a victorious celebration to face the fury of persecution and injustice.

11. Psalm 24 and Missional Engagement

During the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, inculturation and critical contextualization gained attention as missional tools for cross-cultural mission practitioners (

Kraft 2005;

Hiebert 1987). Lamin Saneh’s book

Translating the Message includes the indigenous expressions of music to translate in local culture (

Saneh 1989). However, Christian anthropologists propose an approach going “Beyond Contextualization” (

Shaw 2010), while communication consultants aim to translate the

cultural text, defined as “music, arts, story-telling and dance” by

King (

2019), for communicating the gospel. The Psalms provide a missional mandate and model to rethink and reorganize the pattern of Christian spirituality for South and Central Asia (

Sarwar 2021). Translating Psalms into cultural texts fosters faithful friendship among Muslims (

King 2019;

Hiebert 1987;

Sarwar 2021). Randall Bradley asserts, “Christ came to redeem the world, and Christ can redeem any music” (

Bradley 2012, p. 109). Even John Calvin used the local melodies from ordinary everyday life (

Huh 2012, p. 16). The Psalms redeem cultural texts and tunes and extend worship from prayer and praise to global proclamation through music (

King 2019). The twenty-first century has witnessed the global rise of cultural music with the text of psalms. Concerning the raga-based musical settings for singing Psalm 24:7–10, during the 1970s most of the psalms and hymns were sung and played by professional Muslim singers. This participation is an inclusive approach to the present messianic kingdom. Singing Punjabi Psalms keeps the gates and doors of the kingdom open, with the hope that all the world comes to Christ the King.

12. Conclusions

The book of Psalms/Zabur is a common heritage of divine song that can be used as a bridge for witness between Muslims and Christians. Since the late 1800s, with the development of the Punjabi Psalter, contextualized psalmody has been an important part of the Pakistani worship experience. Ragas, as the melodic basis of the classical music of the Indian subcontinent, connect to the emotions and hearts of those who participate in the music. The sur-sangam of text and tune (the confluence of poetical and musical art) conveys deep meaning to the local populace, becoming a means of spiritual expression.

This paper explores Psalm 24:7–10, both its historic and contemporary musical variations, especially in connection to Christian identity, the messianic hope, and transformed missional engagement in the local context of Pakistan. The vernacular and victorious vocabulary, local raga-based emotive and melodic structure, and upbeat, jubilant rhythmic pattern make the Punjabi Psalm 24:7–10 the most widespread of the liturgical psalms. It is a prophetic path, extends beyond the church walls, and is indispensable to the missio Dei. While singing Psalm 24:7–10, we may bring seekers of truth to a point where they may be surprised by the Truth, the Way, and the Life.