1. Introduction

For most societies, cemeteries, columbaria and similar spaces and structures are the most obvious places associated with death and memorialisation, and as such are heavily endowed with social and symbolic meaning (

Kong 1999;

Maddrell 2016). These gravestones and memorials are the focus of private grief, remembrance and resolution, and also public and community narratives of constructing and maintaining kinship relations and connections to place (

Balkan 2015, p. 123;

Howard 2003, pp. 50–51;

Mytum 1994, pp. 260–61). Such graveyard memorials offer multiple opportunities for communication and are a major category of material culture from the last three centuries offering considerable potential for archaeological analysis, yet they remain relatively under-researched (

Mytum 1994;

Tarlow 2005).

In this article, we extend beyond the graveyards themselves into the wider landscape using qualitative GIS mapping of nineteenth and twentieth century parish burial data from memorial stones. This period is chosen based on the survival of the memorial stones in the selected burial grounds. Using a case study of a single parish to test the methodology, we visually analyse and convey religious and community identities as created and practiced in island-based maritime communities. In the process of visualising the material remains of religious memorialisation, we explore the variations between ecclesiastical structures and local and individual expressions of identity and belonging within a chronological context reaching back to the medieval period. This leads on from our previous research visualising community memories of saintly veneration in the landscape, which employed an extensive chronology spanning the Neolithic to the twentieth century (

Gibbon and Moore 2019). In doing so, we find identities associated with different scales of place, from the island parochial system, smaller farming units, family units to very personal responses to place. From their burial location choices, we can see that nineteenth and early twentieth century parishioner identities are rooted in medieval parishes and estates, yet they can also reach beyond the geographical extents of the immediate settlements to reflect identities formed in extended kinship groups.

This approach sits within the cemetery studies sub-field of historical archaeology, focussing on above-ground archaeology and related historic sources (

Baugher and Veit 2020). It is widely applicable to societies where burial memorials are found and places of habitation and death are known. Whilst this is a small-scale test study, the findings show that this technique of visualisation could be extended to include multiple parishes, non-parochial burials and additional data sets to further explore and map the complexities of religious and community identities. By combining physical expressions of commemoration with historic documents and genealogical studies, we show the potential to visualise combinations of plural and micro identities and connections, thereby moving beyond place-based associations to include different co-existing self-perceptions of belonging linked to familial, cultural and religious identities through time and aligning with a reflexive process of social belonging (

Casella and Fowler 2005).

2. Background

As

Rainbird (

1999) has discussed in detail, islands have long been viewed as distinct and different in Western thought, isolated from contact with other cultural groups and ripe for utilisation by researchers as natural experiments or cultural laboratories (

Evans 1973,

1977). Such ideas have been rightly critiqued (e.g.,

Rainbird 1999,

2007) and reformulated (e.g.,

DiNapoli and Leppard 2018). Furthermore, as both authors are resident within the Orkney archipelago, and one of the authors has ancestors from Rousay and Egilsay, we reject the view of both the individual islands of Rousay and Egilsay and the larger group of Orkney islands as being culturally isolated. This is not to deny that there is the scope for a degree of insularity, but rather to recognise that the sea provides both a means of connection as well as a barrier to movement and communication (

Erlandson and Fitzpatrick 2006, p. 14). These themes of fragmentation and connectivity are well recognised in maritime environments elsewhere, e.g., the Mediterranean (

Horden and Purcell 2000, pp. 123–43;

Horden 2016, p. 212), as well as the wider Western seaways of Europe (

Rainbird 2007, pp. 142–44) in which Orkney sits. It is the sea then which determines inter-island connectedness and separation more than the edge of the land.

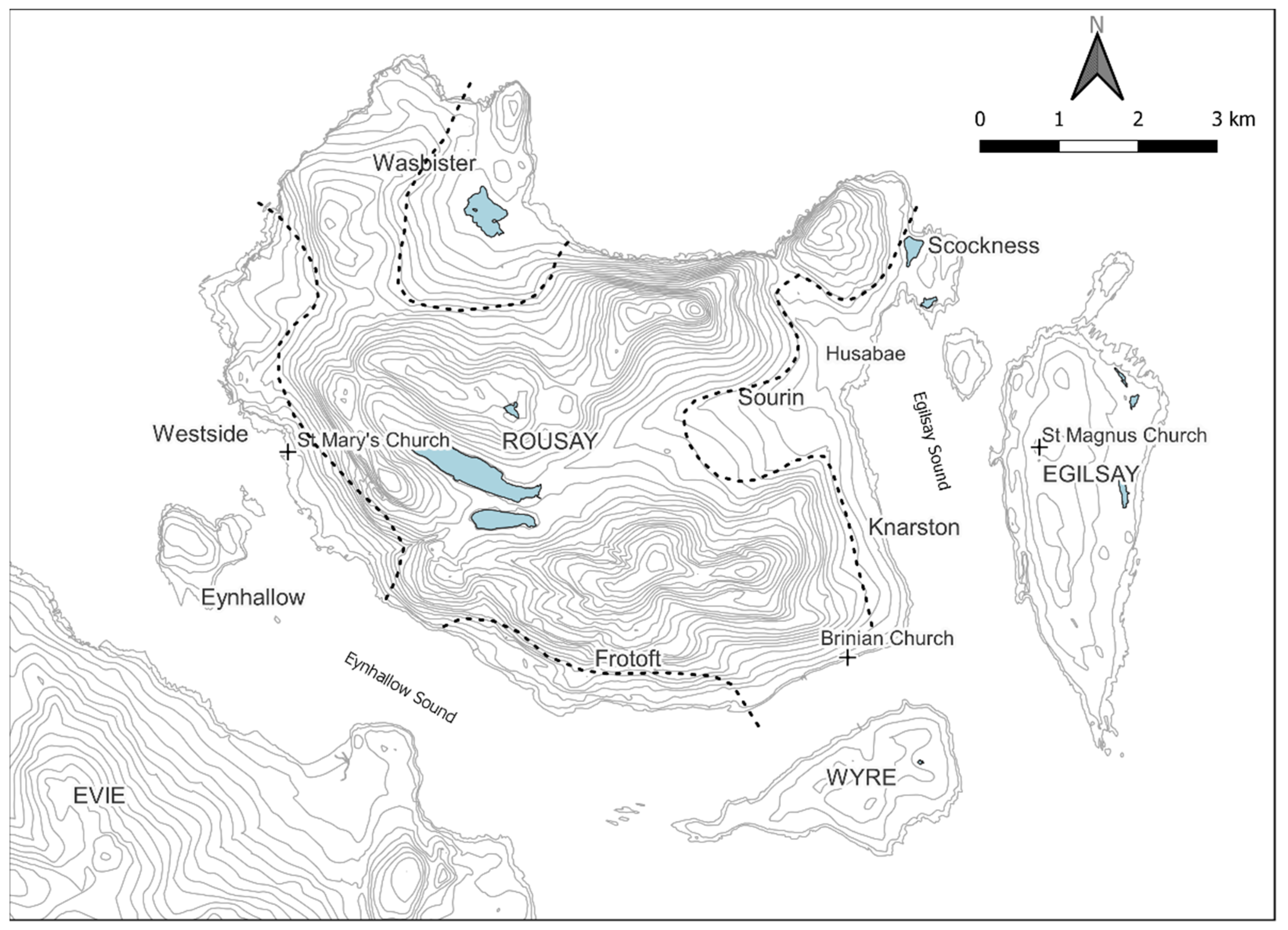

Rousay (

Figure 1) is famed for its Neolithic tombs, and the study of these well-preserved structures provides a useful microcosm of how archaeological attitudes towards islands and the sea have changed during the twentieth century. Both

Childe (

1942) and

Renfrew (

1973, pp. 120–46) considered Rousay as a discrete geographical unit of study, investigating both the distribution of the tombs themselves and the relationships between the Neolithic tombs and the modern farmsteads, and arable land. The flaw, of course, is this consideration of Rousay as an individual island rather than as part of the larger Orcadian archipelago (

Noble 2006, p. 102).

2.1. Parish Structure in Scotland

Identity in Orkney is shaped by the parochial system, which was created during the Western European ecclesiastical reforms of the Middle Ages (

Bartlett 1993;

Gibbon 2006, p. 61;

Fletcher 1997;

Imsen 2003;

Sawyer and Sawyer 2000, p. 115). Similarly to its neighbouring countries of Scotland and Norway, Orkney’s medieval parishes were formed and consolidated from the late eleventh to the early thirteenth century (

Gibbon 2006,

2007,

2012;

Cowan 1961,

1967;

NLS 2021;

Sawyer 1988). Often the network of parishes was created out of pre-existing smaller units (

French 2017;

NLS 2021), as was the case in Orkney, where the archipelago was divided into 35 parishes determined by topographic features, such as hill ridges, watercourses or high coastal cliffs, and influenced by the agricultural settlements and estates that had formed the mainstay of society since at least as early as the Iron Age, if not earlier (

Gibbon 2006, pp. 163–64).

The emphasis on incorporation of large estates in parish delineation indicates socio-political determinations by powerful landowners at the time of formation. This can most clearly be seen in the location of parish churches, of which 14 are found on estates belonging to the earl of Orkney, ten on bishopric estates, nine on privately owned estates and two where the landownership is unknown. There was, therefore, a desire for parish churches to be located on earldom and bishopric land and it is likely that together the earl and bishop were responsible for shaping the parishes, resulting in the prominence of their lands and churches at the core of parochial units (

Gibbon 2012). Although this follows a recognised pattern across much of Western Europe (

French 2017), the significance of the medieval estates that underpinned, in part, the parochial system in Orkney is underemphasised. To a certain extent this is because many of the estates are no longer extant or have been modified greatly and so are difficult to detect. However, there are instances where the medieval estates can be detected, such as the former Husbae Estate comprising Sourin, Sockness and Egilsay in the united parishes of Rousay and Egilsay (

Figure 2).

The parish system in Orkney, as in Scotland, changed little—excepting the uniting of parishes under a single priest—between its inception and the Reformation. However, whilst in Scotland, there were major changes after the Reformation (

NLS 2021), which was not the case in Orkney (

Gibbon 2006), where parishes were further conjoined but not redesigned, suppressed or newly created. Parish boundaries did not change, instead parishes merged; for instance, Evie and Rendall were combined to form a single parochial charge, although in practice they remained distinct places with their own identities and communities. These amalgamations then reflect administrative changes, which in some cases caused little shift in community identities. This lack of change has resulted in longstanding associations with place at a parish level.

It is important to know that Orkney’s parishes were not limited to single land masses, and almost all comprised multiple islands or parts of islands because sheltered waterways between islands linked communities. Until the early twentieth century, owning a small boat suitable for inland waters was common, although in recent years this has become much rarer. Although this change has not been quantified, it has much to do with changes in transportation norms. In Rousay, the first public road connecting the whole island was built in 1874, although the sea remained the main means of transportation for some time thereafter (

Farrall 1874, p. 97;

Pringle 1874, pp. 39–40). Throughout Orkney, communication methods changed in the first half of the twentieth century with the introduction of motorised transportation, the telephone exchange and increasingly regular inter-island ferry services, including a fleet of floating shops (

Hazell 2000, pp. 22–23, 27, 33, 43;

Shearer et al. 1966, pp. 34–35). Additionally, from the later nineteenth century, population decline and a changing economy resulted in the depopulation of smaller islands. These factors meant cross-island identities became rarer too.

2.2. The Parishes of Rousay and Egilsay

Figure 2 shows the parishes of Rousay and Egilsay comprising the islands of Rousay, Egilsay, Eynhallow and Wyre, as well as the Holm of Scockness. United before 1429 (

Cowan and Dunlop 1970, p. 55), the separate bounds of the two parishes are undocumented. Based on modern perceptions of identity in these islands, it might be supposed that Egilsay formed one parish and Rousay the other. However, historic and geographic evidence indicate this was not the case, and that instead Rousay Parish originally comprised the west part of Rousay and Eynhallow, while Egilsay Parish contained Egilsay and the east part of Rousay (

Gibbon 2006, p. 657;

Thomson 1993, p. 340). It is unclear which parish Wyre was in. These parishes were formed around two large pre-existing medieval estates. Rousay is centred on the earldom estate of Westness in Westside and Egilsay Parish is centred on an earldom estate gifted to the bishop comprising the island of Egilsay and the districts of Sourin and Scockness and centred on Husabae (

Figure 2). The ‘natural unity’ and symmetry of this bishopric estate depends on the ‘sound’ that connects the two equally valued parts (

Thomson 1993, p. 340). When these parishes were designated, the settlements geographically closest to each estate were added to it to create two parish units. As such, Westness Estate was combined with Wasbister, Frotoft and Eynhallow to form Rousay Parish and Egilsay Parish combined the bishopric estate with Knarston (and perhaps Wyre).

Ecclesiastically, these parish units were administered together from the fifteenth century, with a single priest serving both parish churches from 1429 (

Cowan and Dunlop 1970, p. 55;

Gibbon 2006). However, some parishioners adhered to their ‘parish’ long after the union. A notable example from the seventeenth century illustrates this point. In 1678, James Traill raised a complaint that the parishioners of Sourin refused to contribute to the repairs of the Rousay Parish church roof as they were “annexed to Egilsha without any law” (

Craven 1893, pp. 76–77). The owner of Egilsay and Sourin and a church enquiry concluded that the inhabitants of Sourin were subject to the session of Egilsay and had attended church in Egilsay “past memory of man” (

Craven 1893, pp. 76–77;

Smith 1907, p. 284). Here, we see parochial identity as separate from, and more dominant than, island identity. The maintenance of the separate parish church administration is evident from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries (

Clouston 1914, pp. 215, 277, 263, 294;

Marwick 1924;

Peterkin 1820). In the 1730s, elders were elected from the western part of Rousay for the Rousay church and from Egilsay and Scockness for the Egilsay church (

CH2/1096/1 n.d., pp. 48–50), so even though the parishes were united, the two parish church congregations were determined by where the parishioners resided.

The identity shared between Sourin, Scockness and Egilsay was also reinforced by estate ownership. The medieval bishopric estate remained intact, administered as part of larger estates, until 1853 when Sourin was purchased by the owner of the Westness Estate, who by this time owned most of the island of Rousay (

Marwick 1924;

Thomson 1981, pp. 26–27, 29;

2008, p. 59). This purchase ended no less than 600 years of land ownership uniting Egilsay and Sourin. The impact of this upon community identities in Sourin and Egilsay is not documented and is one of the reasons for undertaking this study.

The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 mandated that parishioners be buried in parish churchyards (

French 2017). This was adhered to in Orkney, where most burial grounds associated with non-parochial churches went out of use and burials were restricted solely to the parish churchyard. Rare exceptions to this, as in many other places, were chapels of ease with burial rights when communities were distant (often due to the tides and poor overland travel) from the parish church (

Gibbon 2006). Following this pattern, one would expect to find in Rousay and Egilsay two parish churchyards and perhaps a chapel and burial ground of ease in Wyre. But Rousay and Egilsay Parish is quite unique in the number of its historic burial grounds. There is, as expected, the Rousay Parish church (used until c. 1815) and burial ground (last interment 1919) in Westside, the Egilsay Parish church (used until c. 1805 and then replaced with a new church) and burial ground (still in use) in Egilsay and a small church (ruinous by 1845) and burial ground (still in use) in Wyre. However, in addition there are burial grounds located in the largest settled areas; Wasbister (still in use), Knarston (last interment 1943) and Scockness (last interment 1958). Furthermore, there is place name evidence for a fourth burial ground on the island of Eynhallow, although when and by whom it was used is uncertain (

Butler 2004, pp. 35–36;

Jakobsen 1911). In Rousay in 1919, a new parish burial ground was located at The Brinian (

Gibson 1996). This choice of location was practical given the Rousay Old Parish Church replacement was built there in ca. 1815, indicating a shift in parochial focus from west to east. The extensive burial provision on Rousay, from the location and number of sites, indicates a deviation from common practice and church edict, perhaps reflecting the dispersed nature of settlement and a stronger sense of identity within the units that made up the parishes. Moreover, it links these two parishes with a burial practice that is not found elsewhere in Orkney to the same extent, meaning they stand out as different in terms of their burial choices.

In this paper we look at two of the burial grounds, Egilsay Parish churchyard and Scockness burial ground (the burial place for Scockness and Sourin), specifically because they are in the medieval parish of Egilsay and the medieval bishopric estate. By doing so, we can map the homes and burial places of the parishioners and explore the extent to which parish, estate and district level identities can be discerned or were prevalent.

3. Materials and Methods

As with our previous study (

Gibbon and Moore 2019), there are challenges in applying a geographical information system (GIS) to incomplete data that contain an inherent element of ambiguity. There are inconsistencies in the ways in which the places in which people lived and died are recorded, which are discussed in more detail below, as well as missing and illegible records and inscriptions. For our purposes, a qualitative GIS approach is a means of managing and visualising the data and exploring the patterns and outliers in the commemorative texts inscribed into the landscape (

Hanna and Hodder 2015). QGIS 3.20 was utilised to geo-locate all the sites using the British Ordnance Survey grid coordinate system, with base-mapping, terrain data and historical maps all sourced from EDINA Digimap. Most of the houses and farmsteads under discussion are still present within the landscape. For those that have now disappeared, the 1st edition OS maps were consulted; surveyed in 1879, these maps are broadly contemporary with the inscriptions, and only one house (Newhouse, Egilsay) could not be precisely located. Thus, our qualitative data consist of the text, names and dates of the individual memorials attributed not to their locations within the graveyards themselves, but instead discrete locations reflecting the homes and places of death of each individual. Within the data there is scope to analyse patterns of inscription and memorialisation by individual families, which would represent a valuable future project.

Distribution maps are commonly seen as a means of plotting and defining the spread of a particular item of material culture. The process involves moving from collecting instances of a phenomenon, through plotting them on a map and then assessing the formation of clusters, with a view to drawing some conclusions about general patterns (

Wickstead 2019, pp. 52–53). Inherent in such an approach is that there is an edge to the distribution, occasionally with isolated examples that can be labelled as outliers, and thus discussed as abnormal or atypical. Instead, we intend to utilise distribution maps here as a means of exploring the connections between places, each with an integral central place—the graveyard—that links them together.

In general, during this period most people died at or near home—whilst the Balfour Hospital opened around 1845 (

Richardson 2020), this was in Kirkwall approximately 20 km away by sea, and most of the death certificates viewed record the place of death in an individual house. It was customary for older relatives when infirm to either move in with their younger, more able family, particularly after their partner had died, or for their children to move in with them; for instance, one of the memorial stones in the Scockness cemetery commemorates a Betsy Craigie who died at Falldown. After Betsy’s husband died her daughter and husband moved to Falldown and Betsy remained (

Sinclair 1886,

1887). As such, where a person died may not be the same as where a person lived. Whilst this example shows it is possible in some instances to trace habitation movements, even exhaustive historical research could not reveal where each individual resided at all stages of life, as this level of detailed record does not exist for everyone.

The methodology outlined here ensures consistency in the approach to material remains and historical records. The basis of this research is the work of the ‘Orkney Family History Society’ (OFHS), who have recorded and transcribed the inscriptions from monuments and gravestones from the majority of burial grounds across Orkney. Also invaluable was the work of Robert C. Marwick, most notably his book ‘Rousay Roots: Family Histories in Rousay, Egilsay and Wyre’, which has been digitised and is available online (

Marwick 2005), as well as the work of Max Fletcher, whose ‘Rousay Remembered’ website contains a wealth of information on past people and places of Rousay, much of which stems from the knowledge and research of Tommy Gibson, augmented by Fletcher’s own work (

Fletcher 2021).

For each individual recorded on the memorials in the burial grounds, we attempted to identify a location that the person would have been associated with. In some cases a location is recorded directly in the inscription, for the remaining individuals a combination of census data and death certificates were employed to identify the home, and where different the location of the person’s death. It is at this point we should note that in focusing on the memorial inscriptions themselves rather than death records, we are dealing with a partial dataset. There are clearly more people who died than there are memorials—in many cases relatives could not afford or chose not to erect a memorial. We know that several of the burial grounds had earlier phases of burials (

Gibson 1996) and there are a number of memorials that lack any details of the individuals buried, sometimes as a product of decades of erosion and weathering, and in some cases because very minimal detail was inscribed on the memorial (

Tarlow 1998). The focus of this paper is the act of memorialisation and the expressions of identity undertaken through erecting physical memorials in discrete places. In visualising these final resting places, which on occasion do not actually contain physical remains of the individual inscribed, we are able to link the central places of the burial grounds, the people who dwelled in the landscape and the scattered houses and farmsteads in which they lived.

Egilsay and Scockness: Testing a Methodology

The data gathered and presented below represent only part of the physical memorialisation of the inhabitants of the parishes of Rousay and Egilsay. As a means of testing this methodological approach, we identified two burial grounds on either side of Egilsay Sound for this pilot study. These have multiple historical connections (see above) and the physical landforms also facilitate easier movement and communication across the water than via land routes to other parts of Rousay (

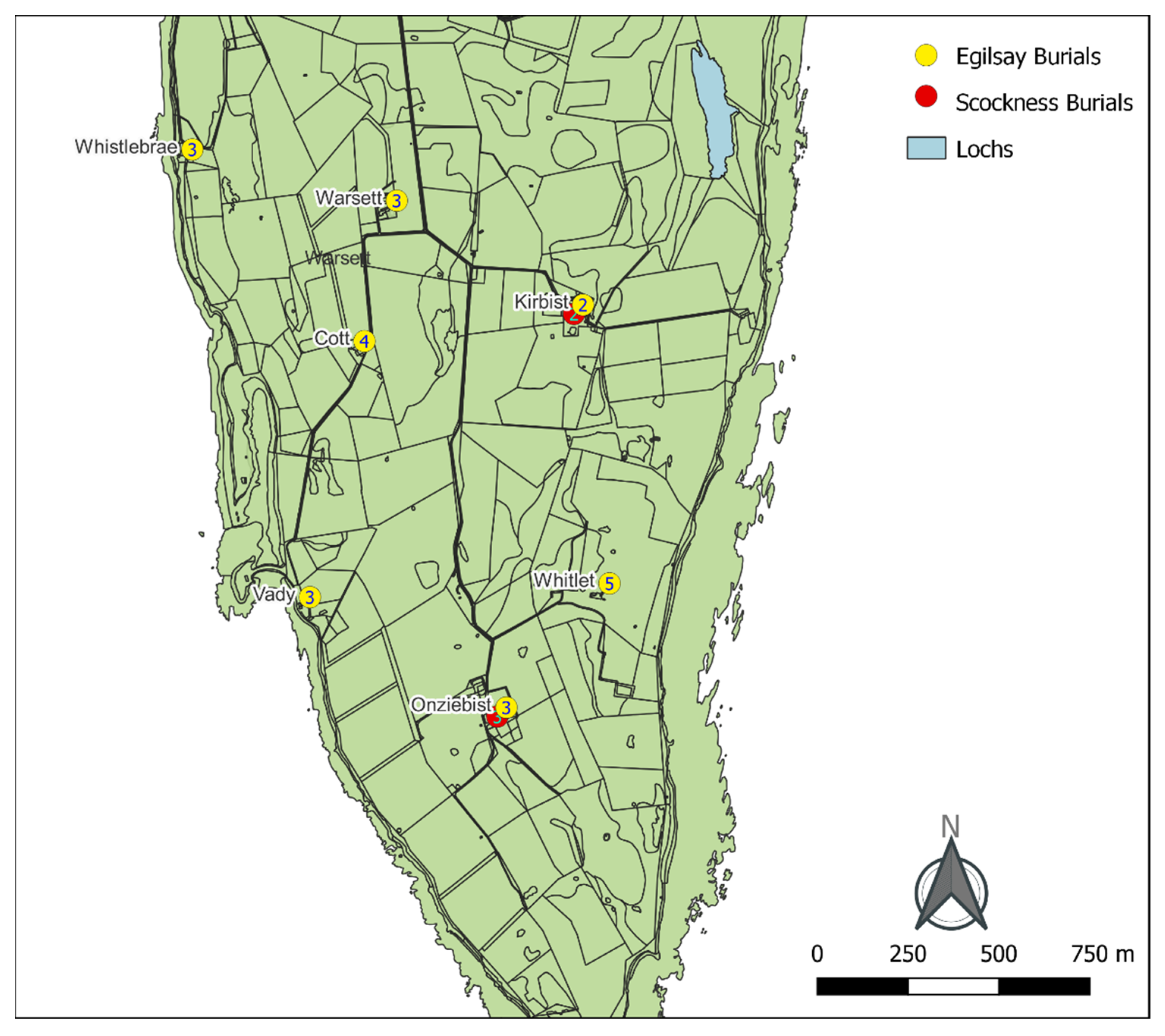

Figure 2). The inscription data from both burial grounds were incorporated into a database—in both of the case study burial grounds, approximately 13% of inscriptions recorded the location of the death, burial or home of the individual (see

Table 1).

The inscriptions themselves provide a relatively low proportion of locational information; however, the census data collected each decade provide considerably more detail, albeit not without some additional considerations. In each instance of an inscription not recording a location, the census data immediately preceding and post-dating the recorded date of death were consulted. In the majority of instances, the place of residence for the family continued to be the same after the death of the individual, and as such it can be reasonably assumed that the deceased had occupied the house up to their death. Only three inscriptions from Egilsay and two from Scockness pre-date the first available census data from 1841, whilst a further 33 from Scockness and 55 from Egilsay post-date the most recent publicly available census data from 1911. Whilst we would certainly consider the inscriptions covered by the census data to be the most accurate, additional details were available through local and family history work conducted by

Marwick (

2005),

Fletcher (

2021) and OFHS, which was included where appropriate.

It should be noted that the census data recorded who was at each house on the day the enumerator visited. Whilst visitors were usually described as such, a man working away might not have been recorded or a servant might be recorded at their place of work rather than where they lived, for example Ann Inkster, whose family lived at Swartifield but who was recorded at Saviskaill in the 1871 census three years prior to her death. Where possible we have attempted to account for such discrepancies, but in some instances the lack of information resulted in an individual record having to be excluded from further analysis. Some inscriptions simply lacked sufficient data with which to be able to identify the individual, and many of the more recent memorials lacked the available data (census and death certificates) with which to investigate further. In total, it was possible to determine a location for a little under three-quarters of the individuals (

Table 2) memorialised in the Egilsay and Scockness burial grounds, and it is these that will form the basis of the results presented in the next section.

4. Results

As noted previously, the research presented here is primarily a means of testing the value and applicability of applying a qualitative GIS approach to the practice of memorialisation. As such, the regarding we can draw concerning the ways in which religious and personal identities were expressed and remade through the erection of gravestones and other inscriptions are by necessity incomplete; however, we are able to draw out some key themes. The first of these considers the way in which inscriptions were explicitly used to link a person to a place. We then go on to explore the ways in which people, or at least the relatives responsible for memorialising them, on occasion subverted the practices that might have been expected by religious authority to instead express a degree of personal or community identity.

4.1. Place Memorialised through Inscription

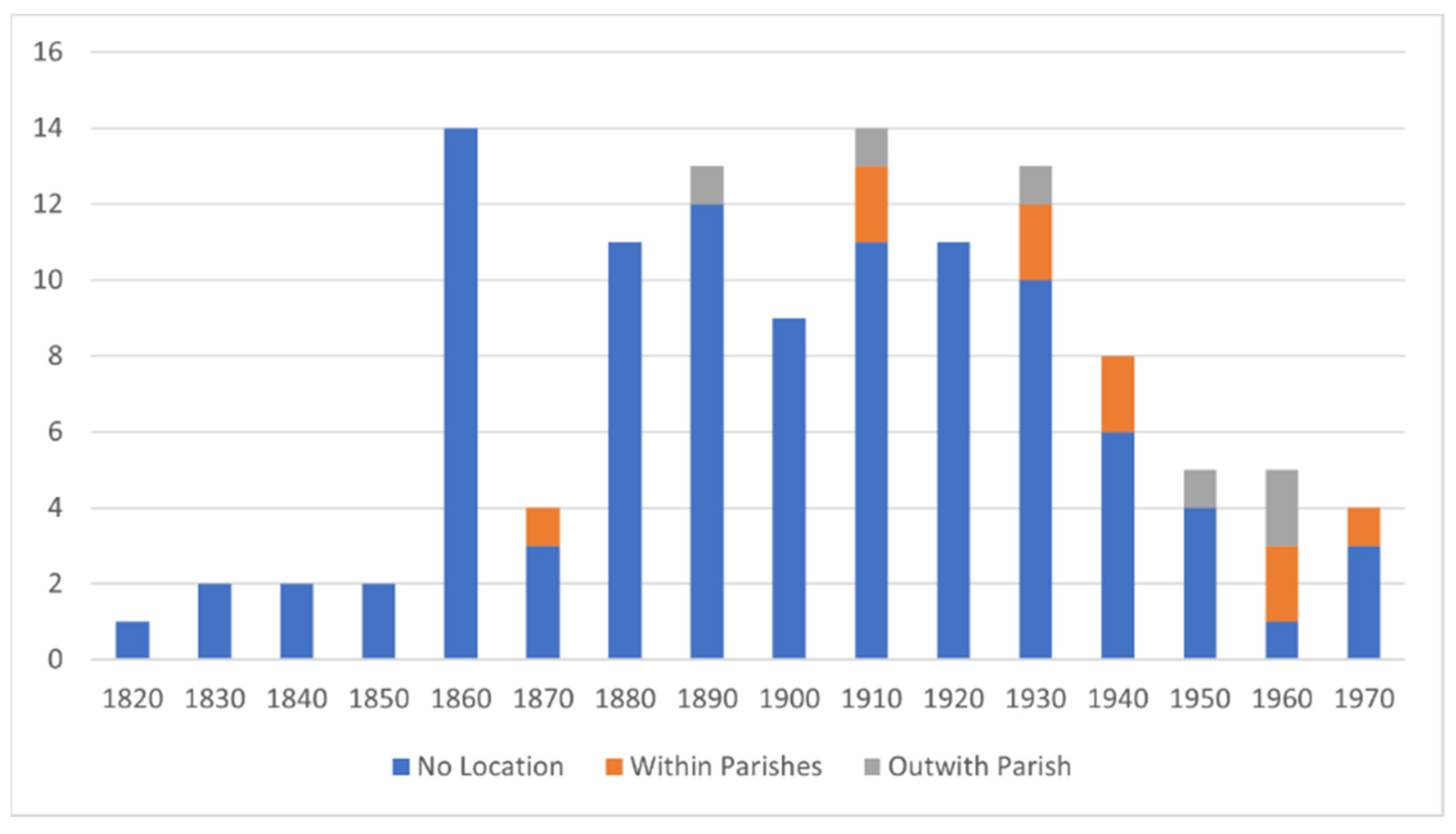

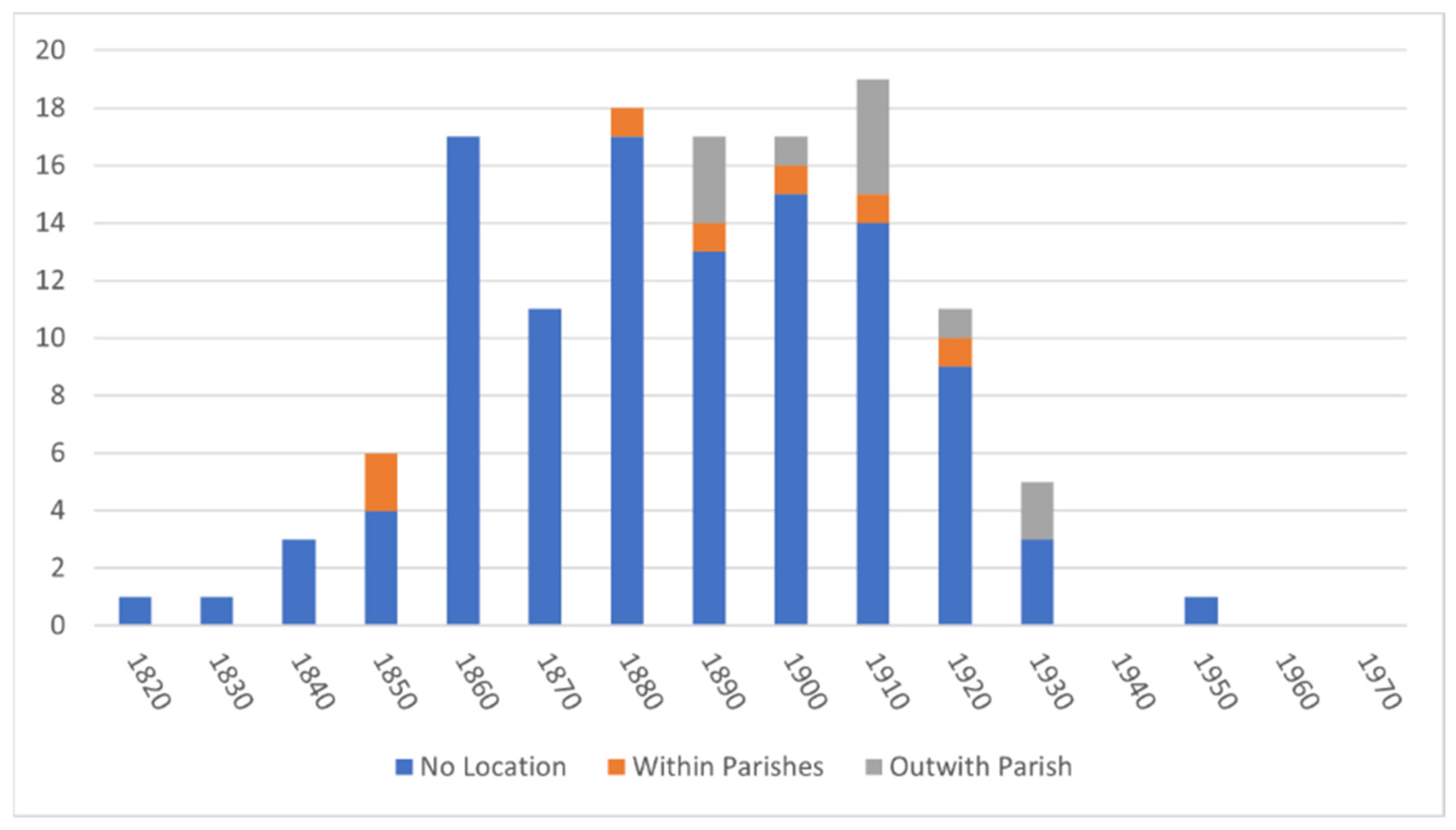

As noted in the methodological discussion above, around 13% of these individuals are directly related to a particular location, either within Orkney or further afield. As a trend, the memorialisation of a place on an inscription seems to have developed in popularity from the very end of the nineteenth century (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), although with the exception of Egilsay during the 1960s this remained a relatively uncommon practice.

We would speculate that the increase in places outwith the parishes of Rousay and Egilsay listed in inscriptions from the 1890s onwards reflects the growing movement of people both into and out of the area. Of course, the impact of the First World War is also reflected in the memorials, with four servicemen being recorded (three in Scockness and one in Egilsay). It is interesting to note that whilst the three Rousay men were related to their place of death, Private James Bews from Egilsay was instead connected to his family home of Meanness. In only one of these instances was the body returned home for burial, with the other three men being buried or commemorated at one of the Commonwealth War Graves in France.

This variation in the way in which people were linked to place also existed in the civilian population during the later activity in both burial grounds. Three individuals living on Egilsay are explicitly recorded as having died at Eastbank Hospital, an infectious diseases hospital and tuberculosis sanatorium opened in 1937 in Kirkwall (

Hamilton 2005;

Richardson 2020). In contrast, a number of individuals who died outside of the parishes are memorialised within the local burial grounds and are linked to the parish itself, for example William Mainland, whose address is recorded as being in the parish of Rendall on Mainland Orkney is related back to Egilsay with the inscription, “In sacred and loving memory of our dear brother William Mainland of Midskaill called home 1 October 1941”. The language used in this inscription also provides a clear reminder that these memorials are produced by the living, surviving relatives.

4.2. Connections in the Landscape

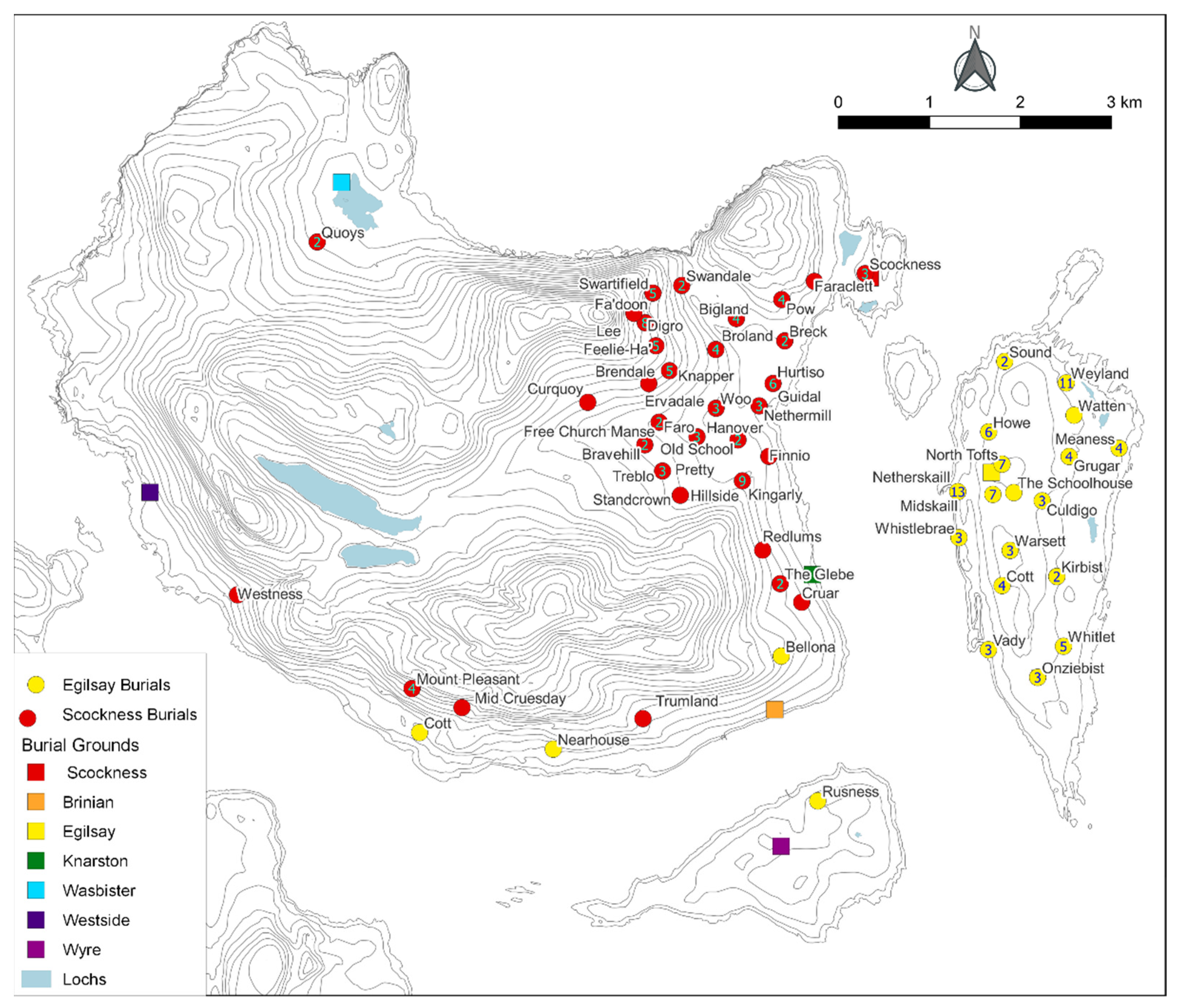

In a typical parish, where funerary rites adhere to standard ecclesiastical practice, all parishioners should be buried in the parish churchyard. In this instance, the parish church is on Egilsay, and as such all the individuals from Egilsay, Scockness, Sourin and Knarston should be transported to Egilsay for burial. Instead, we see a clear spatial patterning (

Figure 5), in which the majority of inhabitants of Sourin and Scockness were buried in the Scockness burial ground and the majority of those who lived in the island of Egilsay were buried in the burial ground there. Undoubtedly there were practical considerations in this distribution; however, as noted above, it was entirely typical in this period for people during life to move back and forth across Egilsay Sound, and indeed all the other sheltered stretches of water within the archipelago. The mapping demonstrates that the parish churchyard of Egilsay is primarily operating not at a parish level, but for the local island community. There is a clear spatial divide suggesting that in death people are reflecting the communities in which they dwelled in life.

The second observation that can be made is that the vast majority of individuals memorialised had resided in the historical parish of Egilsay, with only a small number of people from elsewhere being buried in the Egilsay or Scockness burial grounds. This suggests that there was a persistence in community and geography that can be traced back through the establishment of the parish to the original medieval estate. This further extends to those outliers that demonstrate that the mandate for burial in the parish where they died was not always adhered to. The burial of individuals residing outwith the Egilsay Parish, in Frotoft, Westside and Wasbister, should have been served by the Rousay Parish churchyard in Westside (and after 1919 at Brinian). In all these instances, there is a clear kinship link, normally a child who moved away from the family home or an elderly relative who had moved to live with a son or daughter, presumably when they were no longer able to maintain their own household. In their burial and memorialisation these people ‘returned home’ to Scockness or Egilsay. It is this process that we also see with those individuals who lived and died outside of the parish whether that was on Mainland Orkney in Kirkwall, another island or further afield in Scotland or the wider world.

4.3. Usage of Different Burial Grounds

That the choice of burial ground was related to personal identity, kinship and choice is further demonstrated in instances of houses from which individuals are interred in both burial grounds. The two examples from the island of Egilsay (

Figure 6) presented below illustrate this practice, as well as highlighting the variance in the reasons where discernible for such diversion from accepted practice.

4.3.1. Onziebist

There are five memorial stones linked to the farm of Onziebist on Egilsay—three are in Scockness and two in Egilsay. The two in Egilsay adhere to the general pattern of people being buried in the district where they resided at the time of death. The King family, Edward and Helen, their son John and married daughter Helen with her husband George Seatter, moved from Westray to Onziebist in Egilsay between 1881 and 1885. One memorial stone was raised by Helen to commemorate her husband Edward who died in 1885, to which Helen is added on her death in 1910. The second stone commemorates George Seatter and his wife Helen King (daughter of Edward and Helen). The people commemorated here were not born in Egilsay but moved there as adults to tenant the farm of Onziebist. By the time of Helen’s death, she had lived in Egilsay for at least fifty years. The family’s burial in Egilsay is what one would expect to find.

The three Scockness burial ground memorial stones linked to Onziebist represent a different manifestation of identity, where the family are buried not where they died but where they and their forebears came from. The three memorial stones commemorate Isabella and Thomas Gibson and their son John. They died in 1864 within 7 weeks of each other, with John and Isabella both dying of fever (OFHS). Thomas was from Scockness and the family lived there in 1841. They moved to Onziebist some time before 1851 and were there until they died. Whoever was responsible for their burial chose to take the family ‘home’ to Scockness rather than bury them in the burial ground of the place they died. The significance of this is made greater as they were not buried in the parish churchyard but instead taken to the district burial ground of Thomas’s family. At the same farm we can find examples of different burial practices—one where the deceased are buried in the district burial ground of where they died and the other where the deceased are taken from where they died, across water, for burial in the place where the head of the family originated.

4.3.2. Kirbist

Another example of a farm memorialised in both Scockness and Egilsay is Kirbist. One of the Egilsay memorials, for James and Annie Alexander, states where both died—James “passed away at Kirbist, Egilsay”, and Annie “who died at Eastbank Hospital”—and exemplifies the importance of memorialising the place of death to those who raised the memorial (

Marwick 2005). The other Egilsay memorial is for an infant who died at Kirbist, although this is not inscribed on the stone. Records show her parents living with her paternal grandparents at Kirbist at the time of her death, and it is her grandparents who are commemorated on the Kirbist-inscribed stone in Scockness burial ground. Whilst Margaret’s stone, as with the Alexanders’, memorialises people who died in the island or only left for hospitalisation, the Scockness stone, in contrast, provides an example of the complexities of burial place choice.

The stone commemorates Robert Stevenson, “tenant of Kirbust Egilshay 1855–1904, who died 17 April 1922” (

Marwick 2005), along with his wife Margaret and daughter Rebecca. It is not clear from the inscription why the family are buried in Scockness but it is apparently important to those who raised the stone that the association with Kirbist is remembered. Records reveal that Robert and Margaret passed away in Kirkwall, whilst Rebecca died in Stromness (a town on Mainland), meaning this family, who lived for over fifty years in Egilsay, are not buried there or in the places where they died, but instead are buried in Scockness burial ground, the burial ground for Scockness farm where Robert was raised and the farm of Woo where Margaret was born and raised. The inscription records the tenancy of Robert but not the length of time he lived at Kirbist, as the census records show he was still there as a ‘retired farmer’ in 1911. Therefore, the inscription, although detailed, only gives selected information, and the choice of burial place reflects the childhood homes of Robert and Margaret rather than their marital home place.

5. Discussion

The data reflect a practice of remembrance during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries within one small area of the Orcadian archipelago. A little less than 74% of the people commemorated lived within the bounds of the original parish of Egilsay. Had they all been buried in the parish churchyard, the distribution of parishioners would have demonstrated a recognition of the parish, with the parish church and churchyard as its spiritual centre, as an active ecclesiastical unit some five hundred years after it was united with Rousay. However, the distinct concentration of burials in the district burial grounds in which the deceased resided shows that identity of place was localised within the parish framework to the extent that there are examples of those who spent all but the end of their lives in the district being commemorated in their local ‘home’ burial ground.

In other parish churchyards, ‘local’ community identity was also important to the parishioners, as demonstrated in funerary and burial traditions (

Gibbon 2006). In the parish of Harray, funeral attendance was restricted to those residing in the local district of the deceased and men from within that district were responsible for carrying the coffin to the churchyard. Orphir Parish had burial districts within the parish, with the inhabitants from each being responsible for the upkeep of a particular section of the churchyard wall (

Clouston 1918;

Gibbon 2006, pp. 122, 594). Therefore, throughout Orkney parochially internal, localised identity was realised and perpetuated by funerary practice and administrative allocations in various forms, focussing on the parish churchyard. Rousay and Egilsay are particular in that their localised burial practices are decentralised and expressed in the local districts rather than the parish churchyards, perhaps being symbiotically responsive to the greater degree of geographic separation between districts instilling a stronger community reliance and identity.

The data presented also illustrates some of the complexity and ‘messiness’ of human life and the ways in which individual choice and identity forego broader community and parochial ties, in favour of expressing an individual relationship to a single place within the wider landscape. This is particularly well reflected by the example of Baikie of Tankerness, who is commemorated in Egilsay.

The memorial reads “In memory of Robert Baikie MD, HEICS of Tankerness who died 5 Aug 1890 and of Helen Elizabeth Davidson his wife who died 5 Jan 1886 aged 72” (

Marwick 2005). The Baikie family were major landowners in Orkney, with Egilsay forming part of their estate. Robert was the ninth Baikie of Tankerness, and although born in Orkney spent most of his adult life first in India and then Edinburgh, making short visits to Orkney each summer. He and his wife died in Edinburgh and their burial in Egilsay is rather unexpected. Most of Baikie’s predecessors, including his brother (d. 1869), were buried in the family tomb in St Andrew’s Parish churchyard, where the Hall of Tankerness was located, whilst other gentry of his class were buried in St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall. The personal nature of his burial in Egilsay is inferred by a relative of Baikie’s, who curiously states, “he may have had several special reasons for wishing to be buried there which will not be gone into” (

Traill 1902, p. 34). Traill continues with a romantic explanation for Baikie’s choice of burial place, and it is quoted here in full to exemplify the romance, backstories and speculation that are not found on the burial memorials or official records. This quote is also a reminder that memorialisation is selective, since Baikie’s ‘devoted’ sister-in-law has no memorial in Egilsay.

Robert Baikie was:

Buried in his own Island, where he had spent many happy days with his father and mother’s family, during the summer months, when a boy, among the beautiful wild flowers that grew near the old house of Howan, under the influence of a bright sun. It has been said that Egilshay got more sun than some of the other Islands, which may account for the flowers and grass growing so well there. His very worthy wife and also her sister are buried there, the sister well-deserving a resting place beside the two she had, for so many years, been a cheerful companion and devoted sister to. All three are doubtless sheltered by the old Church Tower. May their ashes rest in peace, and may they ultimately rise amid the glories of a sun, brighter than it formerly shone or does now shine on, what has been said to be one of the prettiest green Islands in Orkney.

During the nineteenth century, there was a dramatic increase in the numbers of gravestones being erected in Orkney, a pattern also noted elsewhere in Britain and Europe (

Tarlow 1998, pp. 35–37). Prior to this boom in the erection of gravestones, the implication is that the location of the physical remains was not important, and indeed in many cases earlier burials were cleared to make room for further inhumations; thus, erecting a gravestone became a way of staking a claim to land which belonged to you and your heirs and ensuring that the remains of the dead should not be disturbed (

Tarlow 1998, p. 41). A letter from Hugh Sinclair in Sourin to his half-sister in Australia written in 1884 gives a glimpse into the costs and choices involved in raising a memorial stone:

Your mother is keeping middling and has thought rather lonely since father died, but still she is wonderful, mulling putting a headstone to the remains some time soon. The ones in the churchyard are of free stone and cost about £3, but I would have an inclination of having one of granite stone. They are made either in Aberdeen or Peterhead. Aberdeen’s is of a reddish colour and Peterhead’s of a grayish colour.

One of the surviving memorials in the Scockness burial ground was raised by Hugh Sinclair in memory of his father and mother, so it seems he made use of his research to commemorate his parents. Such careful consideration and substantial monetary investment underlines the value for people in the later nineteenth century of creating a material connection between person and place. This creation of a ‘material landscape of belonging’ (

Fontein 2011, p. 714) can be set against the social, economic and physical upheaval of the agricultural revolution, the Napier Commission, and subsequent Crofters’ Act of 1886, which gave crofters security from eviction and allowed them to bequeath their tenancy to a successor (

Thomson 2008, pp. 277–80).

Such linkages between houses, people and burial locations as part of a strategy for justifying and legitimising claims to land, expressing belonging and providing the ability to trace lineages find resonances in many geographical and chronological contexts, from migrant Muslim populations in Germany (

Balkan 2015) to contested clan landscapes in Zimbabwe (

Fontein 2011). In Orkney, these linkages of people to and with place through landscape markers have a historic legacy that is traceable across millennia (

Hingley 1996;

Jones 2005). Of particular note here are medieval practices and perceptions of over-water movement and commemoration. The ‘returning’ of Robert Baikie to Egilsay (see above) echoes the 12th century movement and stone-marked commemoration of Earl Magnus’ body from his place of death in Egilsay to his mother’s choice of burial place for him in Birsay and his post-elevation move to Kirkwall (

Gibbon and Moore 2019). Differing practices exemplified by earls being buried where they died (Sigurd Eysteinsson and Harald the Younger) and others being transported from place of death to burial location (Erlend Haraldsson and Rognvald Kali Kolsson) are motivated by political, religious and personal familial choices (

Pálsson and Edwards 1981) and reflect the findings presented here. Furthermore, the recording of their places of death and their places of burial in medieval literature provide textual comparisons indicating a diachronic ‘remembering’ with the stone-inscribed memorials of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The significance of remembering and connecting with ancestors brings us back to the start of this paper and the work of Renfrew (and others), who emphasises the connections between farming communities, belonging and legitimacy (e.g.,

Renfrew 1973;

Richards 2005). Whilst this is often associated with prehistoric communities, so too do choices of burial ground in medieval Orkney imply relationships with earlier occupiers of the landscape, with many burial grounds and small churches, including Scockness, being built on or near prehistoric settlement mounds. The connection between (perceived) burial mounds, burial grounds, ancestors and notions of belonging rooted in the Norse culture of the islands persist in the place and familial identities expressed in the burial choices and memorialisations analysed above.

6. Conclusions

Through the mapping and visualisation of burial memorials, we have we have seen that communities in the inner northern isles of Orkney maintain strong ties to their home district, over and above adherence to parochial norms. We have also demonstrated that these ties to district sit within the earlier parish structure, in turn founded upon medieval estates and smaller units, meaning the district communities pre-date the parish system. Such expressions of community and personal identity pass back and forth between maritime and terrestrial environments, demonstrating the role the sea plays as occasional obstacle and more frequently as a medium for communication and movement, as well as touching upon the complexity of inter- and intra-island relations.

Graveyard surveys and the recording of genealogical data are important aspects of cemetery studies and the broader field of historical archaeology, and here we have demonstrated how the utilisation of a simple qualitative GIS might be applied to explore the patterning and wider linkages between graveyards and the wider landscape. Such an approach has applicability in other contexts where the material culture of memorialisation and historic documentation are available, as a means of investigating the global phenomena of making and remaking of religious, cultural, familial and personal identities through time.