Abstract

The status of apostasy seems unclear in Islamic jurisprudence of the classical age; it is an act considered traditionally to be a legal vacuum, calling for no corporal punishment (mubah). When a sentence was applied in this case, it would seem that it was due to partisan political reasons, rather than on the basis of real spiritual proper needs. Yet today some conservative ulemas apply this status of excommunication, patterned on the modern Catholic model, to practices considered to be “abnormal,” such as homosexuality. What about the Islamic jurisprudence development, as it is conceived and applied today? What is the position of the so-called majority Islamic authorities in regard to apostasy or the perversion of some Muslim minorities? Moreover, what is the position of these ulemas vis-à-vis the so-called alternative progressive movement, which reject the majority Islamic dogma, in France, Morocco, Egypt and elsewhere in the so-called Arab-Muslim world?

Keywords:

Islam; sexuality; gender; politics; postcolonial; Arab; perversion; apostasy; representations 1. Introduction

Beyond proper spiritual contingencies, today some conservative ‘ulama’ apply the status of excommunication, patterned on the modern Catholic model, to practices considered to be ‘abnormal’, such as disbelief or even homosexuality. What about the Islamic jurisprudence development, as it is conceived and applied today in the so-called Arab-Muslim world but also in France, USA, Morocco and elsewhere? What is the position of the so-called majority Islamic authorities in regard to apostasy or the perversion of some Muslim minorities? Is apostasy an authentic Islamic tradition, or is it a post-modern identity uniformization?1

First, let us have a closer look to what some scholars consider as universal values implemented within this tradition per se, in the early years of the emerging Islamic axiology. Then, we shall clarify how apostasy, the exclusion from the universal of non-believers, started to become the new Islamic norm, nonetheless creating schisms and disputes within Muslim communities. We shall put forward the fact that apostasy was, then, defined primarily as the act of treason according to those tribal social and political dynamics. Secondly, we will illustrate how apostasy, in the early 20th century, was categorized as a post-modern ‘perversion’, the consequences of which were that epistemological shift in Arab-Muslim civil societies, especially in the Maghreb. Finally, we will describe how progressive movements, in the early 21st century, started their disidentification towards those uniformized identity dynamics, from within Islam.

In order to understand the context of the argument, and to take into account the methodological aspects relevant to our terrain, let us make clear that a theoretical approach alone shall not be enough. Thus, according to a participative anthropological paradigm (Guerreiro 2011), in the second part of this article we shall insist on the grassroot implementations of those representations. We will focus on the Moroccan and Tunisian contexts, since those two societies seem to be facing post-Arab spring revolutions in a more sustainable and structured way than other countries in the region; plus, those two countries entertain strong post-colonial ties with France, where the biggest European Muslim diaspora lives2.

2. Universalist Roots despite Identity Uniformization

2.1. Universal Faith, Innovation and Reification

This section of our article shall provide an account of how the notion of apostasy, which predominates contemporary Muslim worlds, has been used against minorities, and is politically driven rather than informed by historical genealogies and cultural dispositions. We will focus here on the textual, linguistic, and jurisprudence analysis on the term apostasy, in order to unpack these dynamics.

It is essential to specify that there are currently many diverse representations of what ‘authentic’ Islam is supposed to be. Because of that, it would be very hazardous to establish a unilateral definition of the statute of apostasy in Islam, generally speaking. In fact, beyond the reification of Islam, the tradition of its origins, almost fifteen centuries ago, was packed with many opinions, often divergent. They all claimed to embody the true Islamic ethical values, but all agreed on this fact: the concept of Oneness (Tawheed3) is the very basis of Islamic spiritual traditions.

Tawheed must be understood as the apex of a humanity able to transcend differences. According to the Qur’anic main axiology, the diversity of human cultures is the fertile ground in which our human consciousness is rooted. It is based on knowledge of the self and others. This human diversity makes humans more valorous than angels of light.

Let us quote Mohamed Iqbal, a twentieth century Pakistani progressive intellectual, who came to the conclusion that ‘the Qur’an often communicates through these stories the teaching of a value or philosophical content rather than providing a historical account. It does this by removing the names of characters and locations likely to set the story in a historical context, and also by removing specific details… This method is not unusual; it is more often used in nonreligious literature, for example, the story of Faust, to which the genius of Goethe gave an entirely new meaning’ (Iqbal 2000).

According to this Tawheed ethic, shirk—literally translated as ‘polytheism’, though it could be understood as a ‘profusion of humanities’—was considered to be the worst social evil. For example, one would be considered not fully human, or inferior to a certain elite because of the color of their skin, their religious beliefs, or their atheism, or because they belong to a religious, sexual or ethnical minority.

Therefore, the uniqueness of Tawheed symbolizes the universal union and the potentially divine identity in every part of our humanity. On this point, many thinkers and Sufi ascetics have postulated that the major religious axiologies are likely to converge, by different routes, towards a unified view of the diversity of the divine plan. To quote Mansur al-Hallaj, known as the Christ or the martyr of Islam: ‘at the end of my flight, which exceeded all limits, I wandered the plains of proximity, then looked in the mirror of water, and thus could not see beyond my face’ (Ruspoli 2005).

In other words, beyond the disputes for political leadership and religious authoritarianism, the spiritual perspective endeavored from within Islam since the early middle- ages was based on inclusivity and interfaith dialogue, rather than identity uniformity and general xenophobia towards ‘others’4.

It is a historical fact that despite the prejudices and contemporary violence, Islamic scholars’ deep analysis led a majority of Muslim generations, before modern era colonization and cultural successive alienations, to root their individual ethical values in freedom and well-being (Andrews and Kalpakli 2005) rather than ideological control and repression (Massad 2007).

In a book dedicated to the work of A. Wadud, the American essayist Michael Muhammad Knight describes how his generative ethics of Tawheed destroy performative hierarchies through the extraordinary humility of equal service to God (Ali et al. 2012). On the other hand, this paradigm conforms to what E. Muños calls the need for ‘disidentification’ from prejudices and stereotypes (Muños 1999).

This alternative identity grammar about religiosity and axiological freedom (Martuccelli 2017, pp. 219–38) always goes through a symbolic negotiation among peripheral actors5, and aims to be more pragmatic and adapted to our social reality. It is a long term process, interspersed with political tensions, on which weighs more than two hundred years of resistance from native Muslims to colonialism and the repression of identity diversity (Puar 2007) These alternative Muslims use religion to reach emancipation and freedom, whereas post-colonial Arab-Muslim nationalisms used it for political oppression and identity uniformization6.

Precisely, when their empires had fallen and western colonization had ended, a part of the modern Muslim leadership started worshiping Islamic so-called ‘sharia’7, forgetting about the universal values embodied for centuries by these traditions. Lately, progressive and inclusive Muslim scholars have endeavored an aggiornamento8, a proofreading of those traditions, keeping the ethical axiology and burying alive the uniformization strategies.

2.2. Apostasies, First and Second Degree

The challenge of these liberation theologies is to focus on the spiritual praxis and well-being of each individual rather than on dogmatic and elitist conservatism. They must continue to embody a holistic vision of the spiritual and axiological ethics in the world, without being the traditional clone of either political or ideological partisan paradigms (Bidar 2016).

In other words, they have to stick to the Islamic Qur’anic ethic, while constantly questioning its historical interpretations throughout Islamic eras. Therein lays the danger for the so-called ‘majority’ who holds the power: the aim of this progressive paradigm is the deconstruction of the elitist, bourgeois, non-egalitarian dogma. They reject the ‘infallibility’ of patriarchal religious institutions, greedy for identity control.

For instance, in other religious traditions, the first liberated Christians thought that Marxism—or, generally speaking, anti-capitalism and theories against the exploitation of the poorest—had been the best grammar to explain the roots of modern oppression, and to address the relevant universal axiology rooted within their faith traditions.

Today, in order to articulate in a coherent way the tradition of the origins with post-modern conceptions about freedom of consciousness, some intellectuals use etymology. They recall that apostate (murtad) stands for ‘voluntary abandonment of something for something else’—generally but not exclusively an abandonment from faith or religious vows, if not a doctrine, an ideology—but also turning your back on any given project.

We read in the famous Arabic Dictionary (Lisan Al ‘Arab): ‘To apostate is to turn away’ (Ibn Manr 1290). Once again, the signification is similar. It is close to what liberated Christian theologians in the early 1950s such as Gustavo Gutiérrez9 called the Metanoïa: ‘going back’ to one’s authentic inner core values (Estermann 2009). That is what we call in Arabic tawbah, translated by ‘repentance’ but which could also mean ‘getting back to your true inner-self’.

Apostasy is generally known as the act of one who, having converted to Islam, deserts it to embrace another belief. This is the case-law concept. It is close to the linguistic meaning which supposes introspection, retraction, and mutation. According to Farhat Othman10, the notion of deviation or perversion11—what deviates from the norm, like the deviation of conduct which can be considered as a ‘sin’ or a ‘corruption’—is also carried by the concepts of murtad and tawbah in Arabic.

However, according to F. Othman, those negative significations are the ones known by mainstream Muslims, and to which they have associated this moral judgment about apostasy, without taking account of the original ethical values beyond the so-called traditional ‘law’. The Qur’an does not present kufr12, and therefore apostasy, in its first sense of disbelieving, despite the exclusive uniformization and ideological sectarianism we witness nowadays (Othman 2014).

2.3. So-Called ‘Majority’ Jurisprudence Schools Nowadays

Nevertheless, as is often the case with jurisprudential issues, these conceptions of apostasy emerged decades or even centuries after the advent of Islam as a civilization, with proper institutions and a legal frame.

Thus, for example, the four schools of thought within the majority Sunni Islam (madhahib) agreed that unbelief is about producing in language, in action or in thought, doubts or any related manifestation of the inner heart13. According to this religious so-called ‘law’, apostasy would be therefore the passage from a neglected practice of Islam to open unbelief; this is done either by word or by deed, and sometimes also by conviction (Othman 2011).

Hence, according to some minority conservative interpretations, whoever freely speaks ungodly word loses faith, even if it happens without conviction, without deed, for example in a moment of uncontrollable anger. It is the same if one does an act of godlessness, even without intimate conviction and without expressing it; or even if one opens oneself up to impiety but does not speak of it or act accordingly.

Let us recall that even the very conservative Ibn Taymiyya, a jurist who embodies uniformized patriarchal identities, made a different remark on the subject: ‘The apostate is the one who, after his conversion to Islam, speaks or acts in radical contradiction with the dogma of Islam’ (Ibn Taymiyya 1263/1998). This is obviously less surprising in regard to Islam, because the legislation for earthly life, originally, was based only on proper evidence.

Therefore, it is theoretically impossible to establish a punishment (hadd), for any ‘perversion’ or ‘abnormal’ behavior, as long as it remains in the intimacy or is not manifested publicly either by words or by deeds (Hosain 2002). This is what Imam Abou Jaafar Al AzdiTahaoui affirmed: ‘We do not accuse them of infidelity or idolatry or hypocrisy, and this as long as they do not show anything; we remit their intimate thoughts to God the Great’. And the commentator of the book to specify: ‘because we have the obligation to judge on the evidence and to avoid conjecturing, pouring into lack of science’ (Al-Tahawi and Al-Hanafi 783–2015).

Indeed, it is established that the cardinal principle of judging people with certainty and on obvious facts falls under the foundations of Islam. The Prophet of Muslims would have affirmed: ‘I was not authorized to search people’s hearts nor to reveal their inner self’ (Al-Bukhari 2020; Al-hajjaj 2012).

At most, in the light of traditional jurisprudence, one could say that such an apostate would be classified in the Qur’anic category of ‘hypocrites’ (munafeeqeen), concealing his impiety. Imam Ibn Al-Qayyim corroborates this statement: ‘Such judgments were not envisaged for what could relate to the intimacy without the proof of an action or a word’14.

Yet, here is the kind of erroneous formulation in regards to apostasy that circulates these days: ‘the apostate is one who denies the Islamic religion because of unbelief; so is the one who denies the existence of God or denies the prophets, or denies a messenger, or makes lawful what is unlawful by consensus, such as adultery, homosexuality, alcohol consumption and injustice; or unlawful what is by consensus lawful, such as sale and marriage; or denies an obligation that creates consensus, such as contesting one of the genuflections of the five legal prayers’15.

Once again, as is often the case with jurisprudential issues, the jurisconsults have therefore spoken with more and more severity to judge the apostate. Much more than the Qur’an itself did with ‘hypocrites’, who betrayed the early Muslim community, collaborating with its numerous enemies at that time and jeopardizing its very survival. As shown in verse 217, from sura The Cow, the Qur’an does not foresee any punishment for betrayal:

‘They question thee (O Muhammad) with regard to warfare in the sacred month. Say: Warfare therein is a great (transgression), but to turn from the way of Allah, and to disbelieve in Him and in the Inviolable Place of Worship, and to expel his people thence, is a greater with Allah; for persecution is worse than killing. And they will not cease from fighting against you till they have made you renegades from your religion, if they can. And whoso becometh a renegade and dieth in his disbelief: such are they whose works have fallen both in the world and the Hereafter. Such are rightful owners of the Fire: they will abide there in’.

The Qur’anic verses exhort believers to not give in under the pressure and threats from the majority of polytheistic tribes who, at the time, were fiercely opposed to the emergence of a renewed religious tradition—just like a majority of conservative Muslims are today. Plus, those verses are very clearly centered on the description of a symbolic and metaphysical punishment, because of those non-Muslims’ persecutions against that vulnerable early Muslim community16.

Early Muslim communities, therefore, apprehended apostasy according to its various linguistic meanings. It was not only individual faith mutations, but also several variations which imply alteration, deviance by ruse and bad faith, or collaborative ‘hypocrisy’, and above all complicity with mortal enemies. At that time, it had little if nothing to do with this excessive and totalitarian control temptation we are witnessing nowadays from some extremely radicalized political and religious leaders amongst Muslims.

2.4. Apostasy Betrayal in War, Jeopardizing Tribal Survival

Traditional apostasy representation is thus not only the act of changing one’s faith or renouncing it on an individual level. It is above all an attempt to undermine others’ freedom of consciousness, whether by attacking its foundations, by creating inner doubts about it, or by pushing to disobedience and to rebellion against established political order.

Here, we unravel the axiological dysphoria in which contemporary jurisconsults have, through their flagrant contradiction, been entangled: on one hand, they affirm the freedom of belief in Islam; and on the other they incriminate ‘apostasy’ in the sense of abandoning one faith, whether it is for another or for no other religious faith at all. Therefore, it becomes difficult to freely have faith in a religion that you cannot quit.

Moreover, nowadays, conservative religious institutes issue legal opinions (fatwas) on the topic of apostasy. They stipulate an earthly punishment, asserting at the same time, despite all the above, that this would not be incompatible with religious freedom. However, let us recall that this already shaky conception of ‘apostasy’ is closer, nowadays, to what early Muslim communities considered to be takfirism17: a sect punishing by death penalty anyone disagreeing with their representation of Islamic dogma18.

Let us turn the problem around, for a more systemic and coherent causal effect. The link between jurisprudential apostasy, the state of war and the absence of peace, is needed because the Prophet would not have hesitated, with the treaty of Houdaybia19, to sign a clause stipulating that Muslims could not take back from the people of Mecca the Muslim ‘apostates’, in order to apply on them the death penalty. This clearly shows that the ‘apostasy’ hadd has not been established by early Muslim communities (Sourdel and Sourdel 2004).

Even in a tribal society like that of Islam’s first century, apostasy, per se, was therefore not a crime, nor a betrayal, certainly not in peacetime. Moreover, the epistemological origin of sharia ‘law’ was not, at the beginning of Islam, a desire for ideological hypernormativity. It was a form of pragmatic maslahah20, inherited from Bedouin desert culture, in which taking oppressive measures could lead to outright extinction of the entire tribe.

A fairly obvious parallel could be made with the condemnation of the ‘crime of the people of Lot’. This crime was not originally associated with homosexuality (or anal sex21), but rather with military or ritual rape practices, such as unwanted sexual intercourses on the battlefield by some Arab tribes up until the 19th century. They were doing that in order to punish, take revenge, and humiliate their female and male enemies, affirming their patriarchal superiority, literally on the back of their opponents. Until the 19th century, in fact, some Arab tribes boasted that they raped their enemies, men or women, during a ghazia (Zahed 2019; Dening 1996).

This was the case for the first ‘sodomite’ ever in Islamic history archives, named fuja’a, who was a rebel leader opposed to the central power of Madinah. He turned back to the violent and patriarchal practices of his ancestors, shortly after the death of the Prophet of Islam. The conviction of the latter, ordered to Khalid Ibn Walid on the advice of the caliph Abu Bakr, following a shura (consultation of his close advisers), was thus motivated by geostrategic considerations, and not by the hypothetical need for a ‘biopower’, exerted on Muslims’ corporalities or sexualities, against so-called ‘perverts’ or ‘abnormals’ (Foucault 1999).

Those so-called ‘others’, referred to as outsiders in regard to the fantasized Islamic umma22, are to be considered as scapegoats as in any other uniformized socio-political dynamic. As an illustration of the apex of those identity dysphoric mechanisms, built on the back of minorities and marginalized outcasts, let us recall that the so-called Islamic sharia was centered, at the beginning, on the maintenance of order and public well-being—like in any other emerging civilization (Habermas 1997)—and not on the control of beliefs, corporalities and individual identities (Zahed 2017a).

Besides the eminent value of group life at the time, we must remember that the simple act of leaving the city after settling there, in order to return to the countryside nomadic life, was frowned upon and even rejected outright:

‘Islam has abolished all signs of the fingerprints of anti-Islam and all marks of those which pertain to the very essence of the life of the pre-Islamic people. It encompassed Arab proverbs and Bedouin life; thus it considered to be apostasy the state of nomadism after Islam, and it forbids leaving the city for the countryside. The Bedouin, when he embraced Islam, had to remain a city dweller and he was charged with the duty of making war for the propagation of Islam. The reason was that nomadic and Bedouin life took away the group’s estrangement and abandonment of civic duties such as protecting Islam and to work for the social promotion of common interest. This is why Aba Dhar Al Ghifari, Companion of the Prophet, was accused of having chosen to isolate himself in Rabadha, outside the city, abandoning the group’.(Jawad 2001)

Indeed, the pre-Islamic representation of ‘apostasy’, or tribal betrayal, was clearly not in accordance with our social and political dynamics nowadays. And throughout the Islamic historiography, scholars were divided about which conception of ‘apostasy’ had to be maintained, in regard to the never ending social, political, and civilizational mutations.

2.5. Politico-Religious Schisms and Epistemological Variations

Generally speaking, tradition teaches from Islamic history that apostasy is the refusal of the Arab tribes to pay legal alms after the death of the prophet, which would have reinforced the anger of his successor Abu Bakr. We read in the famous Arabic encyclopedia the following definition of ‘apostasy’: ‘the withdrawal of the Arab tribes-with the exception of Qoraych and Thakif-from Islam after the death of the Prophet. Some who asked to alleviate prayer or not to pay legal alms. Abu Bakr fought them until their return to Islam’23.

Omar saw apostasy of the Arabs from a purely religious perspective, which led him to fight them violently and to be killed afterwards. Unlike him, as clearly demonstrated by O. Farhat (Othman 2011), Abu Bakr might have had a more judicious political position. His ambition was not only to preserve the perenniality of faith in hearts; otherwise, he would have reacted like Omar. Above all, he might have wanted to maintain the perenniality of that renewed social order that those Islamic ethical values allowed to institute, and the State which had emerged from it. The first caliph therefore did not fight the abandonment of religion and the turn back to pre-Islamic patriarchal traditions. He waged war on those who opposed the mainstream social order and engaged violently to destroy it by sowing disorder and encouraging disobedience to the rulers of that young state.

Moreover, we find out that during these wars, particularly with Khalid Ibn Al Walid, the conflict also targeted certain people whose maintenance in Islam could not be doubted; this was the case with Malek Ibn Nuayra and his tribe. The reason they were targeted was that their disobedience to the established order was enough to arouse suspicion concerning the purity of their intentions and the sincerity of their allegiance to the still fragile Islamic central power (Glubb 1963).

What were wrongly called ‘apostasy wars’, were really just a tribal revolt against the authority of Medina and the social order instituted through religious and tribal duties. That ‘apostasy’—social disorder because of political betrayal—had nothing to do, thus, with any religious or sexual denomination per se. Apostasy at that time indicated a cruel political discord, an armed dissension, since we must especially not forget that the dispute was on a tribal level, and that each tribe only recognized the strength logic to defend and impose its unilateral interests.

But one might say that the punishment for apostasy as a betrayal of one’s community—which is both religious but above all tribal—would have been cited in the tradition of the Prophet. For instance: ‘Those who vary in their religion are to be killed’ (Al-Bukhari 2020; Al-hajjaj 2012). Some scholars have contested the veracity of this hadith, because of the presence of Ikrima, a slave of ibn Abbes (cousin of the Prophet), in the chain of transmitters. Ikrima’s reputation is strongly contested, with some accusing him of being a liar, others of being a kharidji (the equivalent of a ‘jihadist’ today). It is not a coincidence that he is one of the only two companions also reporting a so-called ‘hadith’ demanding death penalty for homosexuals (Zahed 2019).

There is another controversial tradition here saying:

‘Any Muslim man who bears witness that there is no god except God and that I am the Messenger of God, his blood is unlawful to shed except under one of three circumstances: a married man who commits adultery; a man who kills an innocent person unjustly; and he who abandons his religion and thus separates himself from the community’.(Al-Tirmidhi 884)

Anyway, without even going into the analysis of the veracity of those traditions, in view of what we have developed before, ‘apostasy’ in the sunnah would thus be synonymous with high treason, to which the first leaders of Islam would have responded with death penalty. Therefore, the sentence is death for the traitor, just as it is until today for those who betray their country, including in democratic states, unless the death penalty has been abolished there24. Whereas no sanctions have been envisaged for these ‘hypocritical’ apostates, at least for those not fighting early Muslim renewed social order.

The latter are often cited in the Qur’an and morally condemned without any doubt by the Prophet, without the latter ever having attacked one of them ad hominem, and even less physically; with the exception of those who would have gone from hypocrites to plotters, especially at the time of the great battle against their enemies’ coalition. These tribes gathered at the gates of Medina in order, according to the tradition, to instantly exterminate the whole of that nascent Muslim community which, by the way, was not one hundred per cent made up of Muslim members.

In conclusion to this first part of our analysis about the condemnation of those called today ‘perverts’ and ‘apostates’, we must distinguish the two senses from one another: hypocrisy or so-called ‘abnormality’ is not a betrayal of the Muslim umma. Thus, any hadd against atheists, religious or sexual minorities, has to be seen as apocryphal and not conforming to the ethical values embodied by the early Muslim community.

3. Contemporary Tribal Apostasy and Perversions in Islam

Let us now have a closer look at the Arab-Muslim societies’ fight against uniformized variations of ‘apostasy’. In this second part of our article, we shall link up the consequences of this historical evolution of the axiological value given to ‘apostasy’, from within Islam and for several years, in particular with the rise of so-called Islamist uniformization, with the engagement of young citizens in Maghreb societies, in the field of individual liberties and so called ‘universal’ human rights.

Our aim here is to provide an empirical basis for how dominant constructs of apostasy are negatively affecting the lives of sexual minorities in Morocco, describing how different NGOs navigate oppressive political structures, providing clearer evidence about how they engage with efforts to deconstruct or disrupt mainstream, conservative understandings of ‘perversions’. But we have to keep in mind that a direct critic of state laws concerning apostasy are forbidden by law, often turning their civil engagement to a borderline hide and seek game with their respective national authorities25.

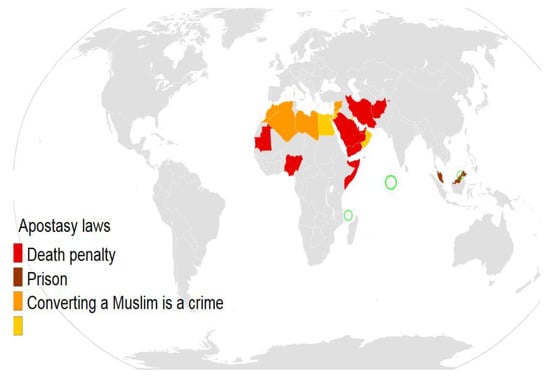

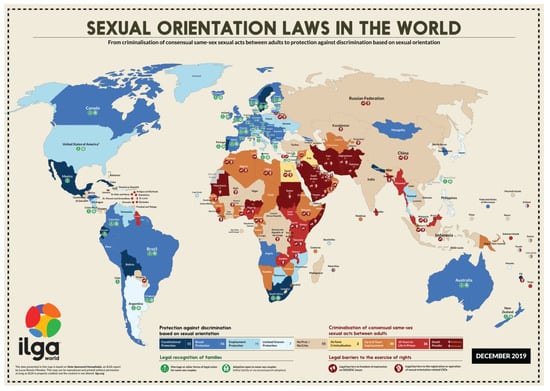

3.1. Freedom of Consciousness in Maghreb: Morocco Minorities Case Study

Since the Arab Spring in 2011, and already before that on an underlying level (Todd 2011), the so-called Arab-Muslim societies have been crossed by axiological and then political upheavals, between radical rejection of any form of religiosity and attempts to reappropriate Islamic ethics within a more universalist framework. Nonetheless, up to this day, deviances such as betrayal ‘apostasy’, or perversions such as ‘sodomy’, are still forbidden in the Maghreb by law, ‘especially in 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic arose’26. From a global perspective, sexual ‘perversions’ are punished more severely and widely than ‘apostasy’, yet considered to be a cultural and political betrayal (see Figure A1 and Figure A2 in Appendix A).

In Morocco for instance, up until recently, ‘apostasy’ was theoretically punished with the death penalty. In 2017, only six members of the Supreme Council of Moroccan ‘ulemas wanted to reform a previous fatwa, stating that: ‘death penalty should be exclusively applied for those betraying their country’ (Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada’s Report 2018). Those Moroccan ‘ulemas went back, indeed, to a more traditional interpretation of the historical ‘apostasy’ crime, despite the general opinion of their jurisconsult brothers within that same national council27.

Moreover, in Morocco as in other Maghrebee countries, non-heteronormative sexual orientations (especially male homosexuality) are still prohibited. It is punished with imprisonment, ranging from six months up to three years. In Algeria, it could go up to ten years, if one ‘promotes’ homosexuality publicly (Ostmane and Zahed 2016). And in Tunisia, since the democratic revolution in 2011, things are not getting better, if not worse (Zahed 2017b).

This allows us to see how political order is maintained in Maghreb, up to today, on the back of so-called deviants (namely ‘apostates’ and ‘sodomites’), perceived as a direct threat for, they say, the entire civil society. This criminalization of so-called ‘deviant’ minorities shows here the acculturation and historical amnesia of an Arab Muslim so-called umma, because originally those two terms referred to the same crime, namely patriarchal abusive relationship to others (including indeed tribal sedition and piracy, ritual rape, etcetera), as explained earlier.

As a result, associations which officially advocate for the recognition of religious and sexual minorities’ rights are, officially, prohibited. From there, we can distinguish two types of organizations that positioned themselves against the criminalization of those so-called ‘deviances’.

On the one hand, there are a few associations recognized as being of public utility by the Moroccan State: human rights associations, for the defense of freedoms, justice, the fight against AIDS, to quote only a few. Their field of action and commitment is either broad or specific, but always focused on another theme. As a consequence, only some of these associations have spoken out publicly, on several occasions, against the criminalization of minority identities, and against the stigmatization of apostates or LGBT+ people in particular28.

We will endeavor here to analyze the interviews29 realized with two associations’ leaders, emblematic of these epistemologically positive tensions. First, the Moroccan association for the fight against HIV/AIDS (ALCS), which campaign for healthcare access for all, and therefore for the decriminalization of minority gender identities and sexual orientations; then, the Alternative Movement for Individual Liberties in Morocco (MALI), which fight for all individual freedoms, including freedom of consciousness and sexual freedom.

First of all, the two organizations are distinguished by their status. The ALCS is recognized by the Moroccan state as ‘a public utility association’, where MALI is ‘not an association’ and claims to be a collective, a ‘civil disobedience movement’, coming from social networks in Morocco. From those two different statuses follow two very different strategies.

According to its national coordinator at that time, Moulay Ahmed Douraidi, the ALCS collaborates and carries out projects in partnership with the Moroccan state, through the Ministry of Health in particular:

‘It is true that the State structures cannot work with these populations because they are stigmatized in the health centers and so on, but it is the State which gives us the money within the framework of the Global Fund, so that we can carry out activities […] with these populations […]. So it is the state that buys condoms and gels that we distribute to homosexuals who come to us; it is from the budget that is given by the Global Fund through the Ministry of Health. We also campaign in partnership with institutions, that is to say we have a collaborative tactic. And we also have a grievance tactic. This protest tactic is the one we spoke about: is it not a problem to ask for the repeal of article 489, [but in collaboration] with other major human-rights organizations’.

This dual approach, collaborator and protestor, led by the ALCS, therefore allows the association to enjoy a certain credibility with the civil society and the Moroccan state on one hand, but on the other hand it does not leave a broad margin for subversion.

Conversely, according to its co-founder Ibtissam Lachgar—an openly atheist activist living between Paris and Morocco for more than 15 years now—the MALI movement asserts that:

‘You really have to bang your fist. Yes we can do that, we also do conferences. But besides that, we have to create a buzz […]. When you make the buzz, everyone knows! You saw there was this! You go to the hammam, in the taxi, at work, with your family: did you hear? Someone is there, they had a picnic, they had a kiss-in. We go out in the public space. So we go out with the LGBT+ flag, with our signs, we take a picture of ourselves in front of the Ministry of Justice, in front of the Parliament… It’s symbolic, that’s still a strong symbolism’.

In fact, those two organizations were initially built through different approaches and operating logics. The basis and the raison d’être of the two structures derive from two divergent ways to think community building, but also to understand society in general and the social issues it faces, in particular minority human rights.

The Association for the Fight against AIDS has been presented to us as:

‘A generalist association, […] not an identity association; we are a community association. The concept of our work is about doing it with people, with community agents, that is to say people who belong to these groups. Because we believe in a simple idea that says deal with it and not do with it. So we work with these people and not for these people; therefore, whether it is men who have sex with men, whether it is sex workers, whether it is injecting drug users, whether it is people living with HIV… And according to our constitution as an association, we advocated for a community approach, and these communities exist within our network as sister associations, as group leaders, and sometimes even as employees of our organization. By working on this community approach, accompanied by all the people who fight against AIDS, we have noticed that there is something that is correlated with the fight against AIDS, it is the fight for individual rights’.

Indeed, vulnerability is not only about health issues, it actually starts with political exclusion from social dynamics:

‘The fight for democracy and human rights and the fight against AIDS, these are therefore two things that are interrelated […]. And so like that, we started to put into the discussions that, in order to succeed in our prevention approach and to also succeed in the fight against AIDS, we must respect the dignity of these people, especially since the whole concept of risk reduction is based on the philosophy of self-esteem […]. And to work with these people on self-esteem, you have to break down the barriers of fear, stigma, and discrimination. Hence our fight against the stigmatization and discrimination of these populations is therefore also part of our demands, since the criminalization of sex work or the criminalization of homosexuality blocks our prevention strategies’.

According to this perspective, the ALCS therefore calls for a universalist approach to human rights, without being as radically opposed to stigmatization than MALI is for instance. Those two different approaches have direct consequences on each branch of the human rights movement in Maghreb.

3.2. Between Radical Universalism and Cooperative Relativism

As a matter of fact, the MALI collective criticizes the majority of Moroccan associative structures for, they say, their lack of universalist perspective, as the collective’s representatives understand it:

‘[MALI is] a movement, that’s important to point out, which is universalist, feminist and secular. So it’s very important, especially the notion of universality, because often in Morocco people who are engaged [for human rights], whether they are independent people or collective associations, have to do a lot with cultural relativism. We reject cultural relativism, we believe that rights and freedoms have no borders, have no skin color, have no religion. So a woman or a man must be free in Japan, must be free in the United States, in France, in Morocco, and we are not going to say: ‘ah but no, but wait, as we are in Morocco, we are not all the same, cultural specificity… that is not for us’. And in fact we often find ourselves isolated on this issue of universality of rights’.

Hence, MALI considers that:

‘What people don’t understand: in human rights there is no priority. People confuse human rights with needs. Needs yes, you can prioritize needs: I must eat, I must… But human rights are interdependent and indivisible. So the right to education is just as important as the right to health, the right to privacy, the right to sexual freedom and so on; that’s it. So unfortunately people often put out this rotten story, that there are priorities. No! Never in human rights, never, never. Does that mean you prioritize the victims? Or discriminations?!’.

Here, in particular, the ALCS strategy diverges since they consider that:

‘Sometimes [international human rights organizations] put causes that are not a priority, sometimes. These are real causes but they are not a priority. They put things that are not a priority for the Moroccan human rights movement’.

Consequently, these different conceptions of minority rights defense, one being total and universalist, the other being more nuanced and relativistic, imply different relationships with the international community for the defense of human rights, in particular vis-à-vis apostasy laws and sexual minorities’ dignity.

The ALCS believes that militant activity must necessarily be endogenous:

‘They are kidding, the international community, when they say that they are the ones who did things […]. The international community comes after. There is always needs for intrinsic actions. They take over, but they didn’t make things happen […]. It is the Morocco who have made progress’.

However, MALI recognizes a certain evolution on these questions of individual freedoms, if only by the emergence of these topics in the public sphere, in Morocco as in other so-called Arab-Muslim societies:

‘That opened the debate, within the Moroccan population, but also within other associations. Here they take part to these debates, and so much the better, because that is what we want: students, even high school students, it’s awesome! Who would have thought that in public high schools students would contact me to tell me we are going to give our presentation in history or in philosophy or in Islamic education, on MALI in general, or about freedom of consciousness, sexual freedom, LGBT+ rights!’

Moreover, MALI activists are well aware that:

‘It will not change tomorrow, neither mentalities, nor laws’.

From then on, she recounts her time in a Moroccan higher education establishment where she had gone at the request of two students:

‘Half the class was against individual freedoms. By cultural relativism: there is freedom… but we are in Morocco, there is cultural pressure. There were women—yes young women, students—who spoke from a misogynist perspective’.

On the contrary, the representative of the ALCS considers that the problem of Maghrebee societies is not on a mentality level but that:

‘It is a problem of political Islam. There is a societal evolution. I can say, even on an anthropological level, that Moroccan have no problem with homosexuality and sex work […]. I say that the problem of criminalization rose to the top with the rise of political Islam […]. He [Hassan II] used the Islamists to attack the leftists […]. So these are mistakes which left after-effects’.

In this sense, he deplores the return of political Islam, which has come to restrict the individual freedoms that Moroccans had in the past:

‘Relations outside marriage have existed in Morocco in a natural way all the time. In my era, when I was in college, there was no boy who didn’t have his friend and vice versa. It was normal with us. With the Islamists, that have become criminalized and people are now hiding’30.

For her part, the co-founder of MALI also considers this renewal of the weight of religion in Moroccan society, but according to her it comes hand in hand with a deeply conservative society:

‘But no, the mentalities are backward here obviously, obviously. It’s a very conservative society, and that is going from bad to worse, there is really a rise of religion, which is terrible, which is impressive, among young people, a lot! And then the education system uh… that’s when you see what’s in the textbooks… It’s still very misogynistic, hateful, homophobic’.

In this regard, she shares with us several anecdotes that have arisen in school environments, which testify of the slowness, or even the non-existence, of any evolution in Moroccan society in favor of the recognition and acceptance of minorities, particularly sexual minorities or non-Muslims:

‘A student who contacted me, he is in first grade, and then their teacher of Islamic education—it’s a private high school—clearly tells them in class that atheists must be killed, we have to kill homosexuals; clearly, like that. Students from Marrakech medical faculty contacted us—there is the psychiatry course in the fifth year of medicine—and the psychiatry teacher (…) told them that homosexuality was a disease, a perversion, it was considered to be as bad as pedophilia’.

The representative of MALI is therefore well aware that:

‘It will not be enough to repeal a law. Look at the law of underage marriages. In the Mudawana of 200431, it is 18 years; well that does not prevent [forced child marriages]. But, it is important that the law has been repealed anyway […]. That can be a first step in any case, avoiding [those minorities] to go to jail’.

Thus, she concludes:

‘We are for the repeal of these laws, but it is parallel. We cannot just repeal a law, we must at the same time work on changing mentalities’.

Indeed, after decades of political Islamic rhetoric, on the back of women and minorities, social hysteresis32 has made it even harder now to distinguish traditions from political strategies, not to mention ethical values centered on individual needs and towards global well-being. Nonetheless, both universalist and relativist anti-uniformized counter-strategies could be seen as complementary, from a strictly sociological point of view.

3.3. Adapting to State Dysphoria, between Human Rights and Cultural Needs

Regarding homosexuality in particular, despite the recent publicity of a few cases, the subject remains generally a taboo in Morocco, as the representative of the ALCS explains:

‘[AIDS] is a topic that is not very taboo like homosexuality or sex workers. Because you will find religious men who are drug users, they can say they are drug users, but they cannot say they are gay, even though there are some among them who might be MSM33’.

This organization, whose approach once again is based on a broad human rights framework, specifies that:

‘The 489 is unconstitutional. So normally it should be repealed, because one cannot be schizophrenic’.

There is indeed an article of the Moroccan Constitution which prohibits discrimination, but sexual orientation is not among the 8 cases listed in the law; this is the actual state dysphoria of the Moroccan civil code34.

As for MALI, it vigorously defends the rights of LGBT+ individuals in Morocco, without any ambiguity:

‘It was MALI that launched the International Day against Homophobia and Transphobia (IDAHO), which did not exist in Morocco before; we launched it, I believe, in 2012’.

According to its representative, it is difficult to measure the number of individuals arrested and who suffered state homophobia or transphobia, only because of their sexual orientation or gender identity:

‘We must not forget that people, whether for article 222, or 489 and 490, are not going to affirm [their sexual identity]. This is also why […] we do not know all the people who were arrested for these reasons. Considering the number of people who lie… After that being said, you can ask the court, they will never give you the precise number’.

In addition, according to the co-founder of MALI, it is social and family pressure that remains stronger than judicial discrimination, as an obstacle to the affirmation of LGBT+ and queer identities in Morocco. In fact, according to her, there are two major pitfalls in Moroccan society that prevent the recognition and emancipation of individuals, and in particular within minorities.

Firstly:

‘Patriarchy is the big deal. The fight against patriarchy is essential because it is patriarchy that ensures women and sexual minorities rights35; it is because we are in a kind of patriarchal, heteronomous, heterocentric society and homosexual people, transsexuals36, etc., are victims of patriarchy’.

On the other hand:

‘The weight of religion is terrible. There really is a socio-religious inquisition in this country. And then I think that, since the King is Commander of the Faithful and Islam is the state religion, this is a big problem; it is really a big problem […]. As long as we do not separate the religious from the political, it will be problematic; it will be really problematic. Secularism is the solution (laughs)’.

Finally, about the issue of minority rights in Morocco, the perspectives adopted by the two organizations presented here differ, in particular, because of their divergent conceptions of the underlying mechanisms of the problem, and their different general long term aims.

Organizations such as the ALCS are more in line with a primarily health perspective: they prioritize access to the health system for those considered as ‘key populations’, including MSM or sex workers. According to that aim, the association’s claims are limited to the decriminalization of homosexuality (as well as relationships outside marriage and adultery), and the non-discrimination of these people.

This approach, which can be qualified as conventional because it is closely subject to the social conventions in place, is explained by the purpose of the organization: the fight against the HIV epidemic. But this strategy could also be explained with the status of that kind of organizations vis-à-vis the Kingdom’s political regime, as well as by its conceptions. These conceptions can be considered relativist: they need to take into account the Moroccan social context, in certain conditions, about human rights.

On the contrary, organizations such as MALI takes the opposite perspective and rebel against the culturalist or relativist approach of a majority of other organizations that campaign against ‘perversions’, including apostasy, and for human rights in Morocco. For this collective, individual freedoms are at the heart of human rights, they are inalienable and humans are all equal. This approach therefore considers freedom along the lines of the slogan: ‘Freedom: either it’s total freedom or it’s not’.

In this sense, the movement defends LGBT+ individuals, sex workers or Moroccan non-Muslims, in order to get their existence and their identities recognized and protected by the state. MALI also campaigns for the visibility of these communities, as well as for their individual emancipation.

These questions, which seem secondary and non-priority to the majority of Moroccan civil society, are of capital importance for these passionate activists:

‘I am a fervent libertarian and I find that […] freedom is really the whole thing. If we don’t have freedom, I find that we have nothing, really, really […]. If they give me food and everything, but taking away all my freedom, I’m not going to eat […]. Too bad, I prefer to die […]. Besides, I am even ready to die for my ideas, that’s why I take all these risks. For me, the risks that I take and the consequences that I have to leave with, are really minimal compared to […] the causes that I defend, for the dignity of human beings, and respect of their human rights’.

In this context, universalist essentialism in Maghreb, which can be observed in MALI’s speech, often goes hand in hand with a total rejection of any representation of Islam (traditional or progressive), seen, by nature, as a totalitarian and coercive system:

‘There are no interpretations, Islam is Islam. It’s written in black on white. No, no there is no possible interpretation, that is not possible. Don’t talk to me about moderate Islam and all that, eh! No, Islam is Islam. There is no moderate Islam (laughs)’.

Here, we may notice that this representation of human rights within such particular movements, considered to be universalist, pushes those organizations’ leaders to fall into a form of essentialism towards Muslims as a monolithic whole, which is to be rejected outright. Hence the question, should and can the emancipation of minorities within Muslim societies be exercised through condemnation and total rejection of this Islamic cultural component, which remains fundamental in these societies?

We stated in the beginning of this second part of the article that those NGOs could not directly criticize state laws forbidding apostasy, nor openly take part in religious deconstructions or aggiornamento for obvious political reasons, but is such representation of the freedom of consciousness, of sexual freedom, really incompatible with any representation of the Islamic faith?

3.4. Progressive Muslims Radical Reformist Movement

That being said, an epistemological and political change is indeed emerging. It can be seen with the commitment of young citizens of the so-called Arab-Muslim world in the field of individual freedoms, and with the academic work of institutions such as those of progressive Muslims in the USA and Europe, where freedom of expression on such matters is possible.

As a matter of fact, in recent years, we have seen the emergence of activists from the so-called Arab-Muslim societies, who have found refuge in European diasporas generally. They are fiercely opposed to all forms of uniformized political expressions under the guise of Islamic religiosity. The famous Palestinian writer Walid Al Husseini, for example, is the author of an autobiography called ‘Blasphemers! The prisons of Allah’ (Al-Husseini 2015).

On the other hand, unlike the Council of Former Muslims in France37, some engaged Muslims are building their counter uniformized rhetoric on the basis of a radical liberation theology, based on alternative interpretations of the original sources of Islamic jurisprudence. For instance, the French Progressive Muslims (MPF)38, chapter of the international Muslims for Progressive Values alliance (MPV)39, have denounced and condemned for several years the institutionalization of anti-apostasy, anti-blasphemy and anti-heresy laws, and the policies endorsed and authorized by state actors who, according to them, directly target participation in the democratic dynamics of religious, political, sexual and ethnic minorities.

These extreme laws and policies would maintain cultural environments of discrimination, social exclusion, and civil disorder, and provide a legal justification for inciting violence and hatred. The condemnation of apostasy, in the broad sense, would formerly have made it possible to maintain public order; it is now transformed into a real tool for the propagation of, what Amin Maalouf calls, ‘murderous identities’ (Maalouf 1998). Here lies the height of this so-called ‘Islamist’ movement’s axiological dysphoria which, after having operated through the amalgam between freedom of consciousness and betrayal vis-à-vis the so-called ‘Arab Nation’, makes the medication against public disorder a poison reinforcing it.

In addition, these committed progressive Muslims denounce, just like the former Muslims of France and elsewhere, the fact that this demonization is intentionally propagated and exacerbated by fundamentalist and extremist religious sects, who defend it by invoking cultural sovereignty. They would use it as a theo-political mechanism, aimed at promoting the objectives of the so-called ‘Islamic’ states and their henchmen, within supposedly non-governmental organizations. These progressive Muslims point out that the spread and justifications for discrimination, fanaticism, incitement to violence and hate speech are absolutely incompatible with existing international conventions about human rights; rights which, while as long as they would also be in contradiction with the radical and original Islamic values, these progressives would like to revive from within Islam.

Moreover, in accordance with the most recent academic research in that matter, the signatories of the statement above confirm that the classical Islamic jurisprudence regarding apostasy is incorrect. In fact, from their point of view, the dogma in matters of first and second apostasy is, as we stated early in this article, in direct conflict with Qur’anic injunctions such as: ‘no constraint in religion’, or ‘for you is your religion, and for me is my religion’40.

Indeed, this last verse clearly recalls the fact that Muslims, a minority in Arabia at the beginning of Islam, sought above all to establish peaceful relationships with the powerful tribes, in particular the one holding the centralized worship place of the time in Mecca. First Muslims certainly did not intend, and were clearly not in a political position, to exterminate all non-Muslims in the name of that freedom of belief evidently quoted in the Qur’an; a freedom of belief they defended from the start, as an emerging community, and without which Islam would probably not exist today in that region.

Finally, progressive Muslims defend the principle that every individual has the right to develop a given faith and convictions, according to the precepts of their heart and vision of the world. Blasphemy being, according to them, a matter of personal responsibility and individual consciousness. It is reinforced by numerous statements in the Qur’an stating that no soul is responsible for another, and that no individual, Muslim or otherwise, has the power to punish those who elaborate their personal axiology and ipseity differently, according to other spiritual traditions for instance41.

Getting back to the radicalism of those human spiritual traditions, these progressive Muslim organizations embody the fact that religious institutions and actors, in partnership with progressive faith-based organizations, could be responsible for promoting egalitarianism and freedom of consciousness, opinion and conviction, through a critical analysis of the Qur’anic scriptures and Islamic ethical values.

That progressive and universally inclusive Muslim aggiornamento is an ongoing process. Only history will tell us if they can succeed in building their counter uniformized rhetoric, on the basis of a radical liberation theology, rooted at the heart of the original axiology of Islamic jurisprudence. But so far, a majority of mainstream Muslims seems to be convinced, directly or indirectly, that ‘apostasy’ just like homosexuality is a betrayal of one’s family and community identity (IFOP 1989–2009). It is also a fact that the young generation, in France and elsewhere, would statistically be less inclined to condemn these minority identities.

4. Discussion

In order to recap, our analysis of apostasies and perversions in Islam made us reconsider the meaning of ‘apostasy’. After considering the roots of the universal values implemented within the Islamic original tradition in the first section of this article, we saw that the meaning apostasy has nowadays for the majority of Muslims is very different from the meaning it had at the dawn of Islam.

Indeed, the pre-Islamic representation of ‘apostasy’ was clearly not in accordance with our social and political dynamics nowadays. And throughout the Islamic historiography, scholars have been divided about which conception of ‘apostasy’ had to be maintained, in regard to the never-ending social and political civilizational mutations. It led us to show that the actual uniformized radicalization of Islamic identities has nothing to do with the original axiological message delivered in the Qur’an. Muslim scholars, for centuries, established a faith exclusive of the slightest interference between God and His or Her creatures.

It allows Muslims to root their individual ethical values in freedom of consciousness and well-being, rather than ideological control and political repression. But after the end of western colonization, modern Muslim generations started worshiping Islamic so-called ‘sharia’. Doing that, they forgot about the universal values embodied for centuries by original traditions. Several Muslim intellectuals, since the mid-twentieth century, already denounced ‘sharia’ and the wahabi political forcing of identity uniformization and overwhelming control upon bodies and minds this led to. They insisted that the spiritual perspective of Islam was originally based on inclusivity and interfaith dialogue, rather than identity uniformity and general xenophobia.

Lately, progressive and inclusive Muslim scholars endeavored an aggiornamento, a proofreading of those traditions, keeping the ethical axiology. They dug up the authentic meaning of ‘apostasy’ law, in the traditional Islamic fiqh. They were able, over the last ten years or so, to address publicly the so-called ‘apostasy sharia’ for what it is: a totalitarian hubris¸ the taste for an absolute control of some extremely radicalized leaders amongst Muslims who want to reinforce, like never before, their stranglehold. In the second part of our article, we linked up the consequences of the historical evolution of the axiological value given to ‘apostasy’ with the engagement of young citizens in the field of individual liberties, especially in the Maghreb societies. We talked about two different types of community building with different approaches and operating logic. Those two branches of civil rights movements within Arab-Muslim societies derive from divergent ways to apprehend society and the place of minorities in it. Some, mainly amongst universalist leaders, think that it will not be enough to repeal a law, or to reform again the Moroccan Mudawana for instance. They believe that they ought, at the same time, to work on changing mentalities.

Indeed, after decades of political Islamic rhetoric on the back of women and minorities, social hysteresis has made it even harder now to distinguish traditions from political strategies and ethical values centered on individual needs towards global well-being. Nonetheless, those two divergent branches of the civil rights movement could be seen as complementary, regarding homosexuality in particular, which is still taboo in Maghreb. We also showed that universalist essentialism often goes with a total rejection of any representation of Islam (traditional or progressive), seen, by nature, as a totalitarian and coercive system. Those organizations’ leaders fall into a form of essentialism towards Muslims as a monolithic whole, which is to be rejected outright. But we can ask ourselves if the emancipation of minorities within Muslim societies can and should be exercised through condemnation and total rejection of a component which remains fundamental in these societies… That being said, an epistemological and political change might be reinforced in the near future thanks to the commitment of young citizens of the Arab-Muslim world in the field of individual freedoms, and to the academic work of progressive Muslims in the USA and in Europe.

Some engaged Muslims are building their counter-uniformized rhetoric on the basis of a radical liberation theology, based on what they consider to be the original sources of Islamic jurisprudence. That progressive and universally inclusive Muslim aggiornamento is an ongoing process, putting behind fear of the other and post-colonial trauma. Only history shall tell us if they will succeed. But so far, a majority of mainstream Muslims seems to be convinced, directly or indirectly, that ‘apostasy’ and ‘sodomy’ are acts of betrayal of one’s family and community identity. Young generations, in France and elsewhere, seems statistically less inclined to condemn these minority identities, which might mean that education and integration could be a strong, if not the main factor to be used in order to deconstruct, over the long run, overwhelming xenophobic authoritarian control upon bodies and minds within Arab-Muslim social groups.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all scholars who have helped through their research to finalize this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Laws criminalizing apostasy (Wayback Machine Library of Congress 2014).

Figure A2.

World map on sexual orientation laws (ILGA World 2020).

Notes

| 1 | Edited by Danaé Grimbert, assistant publisher of CALEM Publishing, Marseille. |

| 2 | Mediapart, Available online: https://blogs.mediapart.fr/sycophante/blog/291217/la-croissance-de-la-population-musulmane-en-europe-dici-2050 (accessed on 15 March 2021). |

| 3 | Unicity. |

| 4 | Literally, ‘the irrepressible fear of the Other’. |

| 5 | Non-religious or political institutions. |

| 6 | One fascia, a unique identity considered to be ‘normal’. |

| 7 | In Arabic, shari’ in a path, it refers to an individual journey, not to a dogmatic jail; on the other hand fiqh, indeed, which literally means understanding, is referring to the ‘Islamic law’, to that jurisprudence established over centuries, and most of the time made or rebuilt lately by patriarchal scholars with oriented political agendas. |

| 8 | Adaptation of the Christian dogma to the contemporary reality, mainly through the Protestant historical movement which started early XVIth century. |

| 9 | Born on the 8th of June 1928 in Lima (Peru), he was a priest, philosopher and theologian. Considered to be the father of liberation theology, he became a Dominican monk in 1998. |

| 10 | Writer, independent researcher and former diplomat (Consul-Deputy at the Consulate in Strasbourg: 1983–1984, Consul at the Consulate General in Paris: 1984–1992, Social Counselor at the Embassy in Paris: 1992–1996). He was removed from the diplomatic framework in 1996 by the administration of the old regime. |

| 11 | Not in a psychopathological perspective (harming, reducing well-being), as defined early twentieth century in Europe, but in a preconceived moral way. See Freud (2011). |

| 12 | Generally translated by ‘non believer’, while Toshihiko Izutsu, a Japanese linguist, specifies that this term comes from ‘hiding’, not from ‘betraying’; see Izutsu (2002). |

| 13 | Contribution of Abdennur Prado (President of the Spanish Conference on Islamic Feminism, Barcelona, former president of the Junta Islamica) in Ali et al. (2012). A jihad for justice: honoring the work and life of Amina Wadud (dir.); 48hrsbooks.com, United States. Available online: https://www.bu.edu/religion/files/2010/03/A-Jihad-for-Justice-for-Amina-Wadud-2012-1.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021). |

| 14 | ‘I’laam al-Mouwaqi’in ‘an Rabb il-’Alamin’. Almadina. |

| 15 | Wahiyya Al Zahili. Al fiqh al islami oua adilatuh (Islamic jurisprudence and its evidences). Dar al fikr, Damascus. |

| 16 | For instance, Qur’an: 1.217; 5.54; 47.25; 16.106; 3.86-87; 4.115 & 137, etc. |

| 17 | Could be translated, roughly, into excommunication. |

| 18 | Herein, even some very conservative Muslim scholars were, at some point, overwhelmed by their most violent students. See for instance Al-Albany (2013). |

| 19 | Signed in 628, between the Prophet and non Muslim tribe leaders. |

| 20 | Political consensus towards community well-being. |

| 21 | Mezziane (2008, vol. 55, pp. 276–306). See also Amir-Moezzi (2007): according to M. Benkheira, it is clear that a very important debate on ‘sodomy’, between spouses, took place during the 8th century; ‘sodomy’ shall be understood, only since then, as anal intercourse generally speaking and not only abusive ritual or military rape practices. M. Mezziane specifies, in the same way, that the argumentation on the reasons for the prohibition of homosexual sodomy—no longer as an act of apostasy (irtidat as for the people of Lot) or of insubordination to the prescriptions of God (fisq), but as an ‘unnatural act’—was worked out for the needs of the cause quite late, long after the death of the Prophet of Muslims. That confusion between same sex intercourses, anal sex, and ritual or military rape practices, has been reinforced over the centuries through, first, the misunderstanding by non-Arab-Muslim scholars of terms such as dubur(giving your back, your anus, but also turning your back on something), and second, by mixing different prophetic traditions rejecting different condemnable practices, not all related to sexual acts, into one unique ‘abomination’: homosexuality. |

| 22 | Muslim community. |

| 23 | P. 765. Dar hiyad al turab al ‘arabi, Beirut. |

| 24 | According to the Death Penalty Information Center, since 1976, more than 75 nations have abolished the death penalty for all crimes, while others have abolished it for ordinary crimes. Available online: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/policy-issues/international/countries-that-have-abolished-the-death-penalty-since-1976 (accessed on 15 March 2021). |

| 25 | Those non-structured, open interviews had been conducted between 2013 and 2016, during my various work in Maghreb, mainly in Morocco and Tunisia; Algeria is sadly missing from this picture, since I could not go back there (‘promoting homosexuality’, as they describe my work there, is punishable by ten years of prison). |

| 26 | See the Nassawiyat 2020 collective grassroot report. Available online: https://nassawiyat.org/en/2021/02/22/loubya-in-time-of-corona-report-2020/ (accessed on 15 March 2021). |

| 27 | This hadd is not in the Moroccan civil code and was, they say, never applied. Plus, it is in direct contradiction with Article 220 stating that: ‘Anyone who, through violence or threat, restrains or prevents one or several persons from worshiping or attending worship, is punishable by imprisonment for six months to three years and by a fine of 200 to 500 dirham [about $C28 to $C70]’. |

| 28 | Lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender individuals. |

| 29 | In 2016 by Zahed, L. in Casablanca, during our work for the publication of Zahed, Ludovic-Mohamed. 2017a. Islams en devenirs. Marseille: CALEM. |

| 30 | Laws criminalizing apostasy or homosexuality, and others so-called ’deviances’, are not always applied strictly, according to the political dynamic in this or that Maghrebee society at a given moment. |

| 31 | The personal status code, also known as the family code, in Moroccan law. It concerns issues related to the family, including the regulation of marriage, polygamy, divorce, inheritance, and child custody. Originally based on the Maliki school of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence, it was codified after the country gained independence from France in 1956. Its most recent revision, passed by the Moroccan parliament in 2004, has been praised by human rights activists for its measures to address women’s rights and gender equality within an Islamic legal framework. |

| 32 | The property of a system whose evolution does not follow the same path depending on whether an external cause increases or decreases. A consequence of that effect is that inputs if violence within a given society make it, over the long term, part of that society’s culture. |

| 33 | Men having sex with men. |

| 34 | Article 19 of the Moroccan constitution. Available online: https://ma.boell.org/fr/2014/07/15/article-19-de-la-constitution-marocaine (accessed on 15 March 2021). |

| 35 | See for instance Lamrabet (2011). Hematologist doctor at the Children’s Hospital in Rabat, Morocco, A. Lamrabet is a Muslim intellectual engaged in rethinking the issue of women’s right in Islam. |

| 36 | Nowadays the correct word would be ‘transgender’. |

| 37 | An international NGO founded in 2007, first in Germany, now with chapters in several European and Arab or Muslim majority countries. Available online: http://exmuslime.com/ (accessed on 15 March 2021). Our organization, CALEM, was part of an online public dialogue between progressive Muslims and ex Muslims in summer 2020. |

| 38 | Founders of the first European inclusive mosque in Paris (2012). Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2012/11/30/une-mosquee-ouverte-aux-homosexuels-pres-de-paris_1798351_3224.html (accessed on 14 August 2021). |

| 39 | https://www.mpvusa.org/alliance-of-inclusive-muslims (accessed on 15 March 2021). |

| 40 | Qur’an: 109.6. |

| 41 | See for example Qur’an: 2.87, ‘We assuredly granted Moses the Book, and after him sent succeeding Messengers (in the footsteps of Moses to judge according to the Book, and thus We have never left them without guides and the light of guidance). And (in the same succession) We granted Jesus son of Mary the clear proofs of the truth (and of his Messengership), and confirmed him with the Spirit of Holiness. Is it (ever so) that whenever a Messenger comes to you with what (as a message and commandments) does not suit your selves, you grow arrogant, denying some of them (the Messengers) and killing others?’ |

References

- Al-Albany, Nasreddine. 2013. Fitnatou al Takfir (Troubles of Excommunication). Commented by Ibn Baz & Al-‘Uthaymin. Dar Ibn Khuzayma (French translation of Dar Al Muslim). French translation. Available online: https://www.salafidemontreal.com/doc/La_Fitnah_du_Takfir.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Al-Bukhari, Abu Abdullah. 2020. Sahih al-Bukhari (1 to 9 Volumes in One Book). London: Mohee Uddin. [Google Scholar]

- Al-hajjaj, Ibn Muslim. 2012. ‘Sahih Muslim’. Paris: Al Hadith éditions. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Husseini, Waleed. 2015. ’Blasphémateur ! Les prisons d’Allah’. Paris: Grasset. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Kecia, Juliane Hammer, and Laury Silvers. 2012. A Jihad for Justice: Honoring the Work and Life of Amina Wadud. 48hrsbooks.com, Akron, Ohio, USA. p. 33. Available online: http://www.bu.edu/religion/files/2010/03/A-Jihad-for-Justice-for-Amina-Wadud-2012-1.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Al-Tahawi, Abu Ja’far, and Ibn Abil-Izz Al-Hanafi. 783–2015. Sharh al ‘Aqidah al Tahawiyya. Paris: Maison d’Ennour. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tirmidhi, Abu ‘Isa Muhammad. 884. Sunan Al-Tirmidhi. Available online: https://sunnah.com/tirmidhi (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Amir-Moezzi, Mohammad Ali. 2007. Homosexualité. In Dictionnaire du Coran. Paris: Robert Laffont, pp. 400–2. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Walter, and Mehmet Kalpakli. 2005. The Age of Beloveds: Love and The Beloved in Early-Modern Ottoman and European Culture and Society. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bidar, Abdenour. 2016. Self Islam. Paris: Points. [Google Scholar]

- Dening, Sarah. 1996. The Mythology of Sex. Chapter 3. Macmillan General Reference. New York: Sexual Minorities Becoming, throughout Middle Ages, in Europe and Then in Middle East, the Scapegoat Responsible for all ‘Abnormal’ Human ‘Perversions’. [Google Scholar]

- Estermann, Joseph. 2009. Teologia Andina: El Tejido Diverso de la fe Indígena. Tomo I’. Bolivia: Instituto Superior Ecuménico Andino de Teologia. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1999. Les Anormaux. Cours au Collège de France. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 2011. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. Eastford: Martino Fine Books. [Google Scholar]

- Glubb, John Bagot. 1963. The Great Arab Conquests. London: Hodder and Stoughton, p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, Antonio. 2011. Enquête de Terrain à l’heure de la Mondialisation: Repères Méthodologiques de Malinowski à L’anthropologie Participative. Paris: L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1997. Droit et Démocratie: Entre Faits et Normes, Chap. IV. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Hosain, Samuel. 2002. The Development of Apostasy and Punishment Law in Islam. Ph.D. thesis, Glasgow University, Glasgow, Scotland. Available online: http://theses.gla.ac.uk/991/1/2002lamartiphd.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Ibn Manr, Muhammad Ibn Mukarram. 1290. ‘Lisan Al’arab’. Available online: https://arabeclassique.forumactif.com/t2524-lisan-al-arab-pdf-ibn-manr-muammad-ibn-mukarram (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Ibn Taymiyya, Taqi Al-deen Ahmad. 1263/1998. As-Saarimul Maslul ‘Ala Shatim Ar-Rasul (The Drawn Sword against Those Who Insult the Messenger). Beirut: Dar al kutub. [Google Scholar]

- IFOP. 1989–2009. Enquête sur l’implantation et l’évolution de l’Islam de France. Mannheim: ANALYSE, Available online: http://www.ifop.com/?option=com_publication&type=publication&id=48 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- ILGA World. 2020. The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. ‘ILGA World map on sexual orientation laws’. Available online: https://ilga.org/ILGA-World-map-sexual-orientation-laws-20-languages (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada’s Report. 2018. ‘Morocco: The Situation of People Who Abjure Islam’. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/publisher,IRBC,,MAR,,,0.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Iqbal, Muhammad. 2000. The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam. New Delhi: Kitab Bhavan. [Google Scholar]

- Izutsu, Toshihiko. 2002. Ethico-Religious Concepts in the Quran. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jawad, Ali. 2001. Al mufassal fi tarikh al ‘arab kaba al Islam (Explanation of Arabs history before Islam). Beirut: Dar al saqi. [Google Scholar]

- Lamrabet, Asma. 2011. Islam-Femmes-Occident. Paris: Séguier. [Google Scholar]

- Library of Congress. 2014. ‘Laws Criminalizing Apostasy’. Archived at the Wayback Machine. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apostasy_laws_world_map.svg (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Maalouf, Amin. 1998. ‘Les identités meurtrières’. Paris: Grasset. [Google Scholar]

- Martuccelli, Danilo. 2017. La Grammaire Axiologique et la Sociologie des Valeurs. Questions de Communication 32: 219–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massad, Joseph. 2007. Desiring Arabs. Chicago: University of Chicago press. [Google Scholar]

- Mezziane, Mohamed. 2008. Sodomie et Masculinité chez les Juristes Musulmans du IXe au XIe Siècle. Arabica 55: 276–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muños, Esteban. 1999. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and The Performance of Politics (Cultural Studies of the Americas)’. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ostmane, Zack, and Ludovic-Mohamed Zahed. 2016. Genre Interdit. Marseille: CALEM. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, Farhat. 2011. L’apostasie est Licite en Islam, en Voici la Preuve. Available online: https://www.huffpostmaghreb.com/#!/farhat-othman/lapostasie-est-licite-en-_b_5629553.html?utm_hp_ref=maghreb (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Othman, Farhat. 2014. Apostasie en Islam. Casablanca: Afrique Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Puar, Jasbir. 2007. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruspoli, Stéphane. 2005. Le Message de Hallâj l’Expatrié. Paris: Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Sourdel, Dominique, and Janine Sourdel. 2004. Dictionnaire Historique de l’islam. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, Emmanuel. 2011. Allah n’y est Pour Rien. Paris: Le Publieur. [Google Scholar]

- Zahed, Ludovic-Mohamed. 2017a. Islams en Devenirs: L’émergence D’éthiques Islamiques Libératrices par la Conscience Accrue des Genres & des Corporalités Minoritaires. Marseille: CALEM. [Google Scholar]