Riding the Wave: Daily Life and Religion among Brazilian Immigrants to Japan in the Age of COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction: How the Story Began

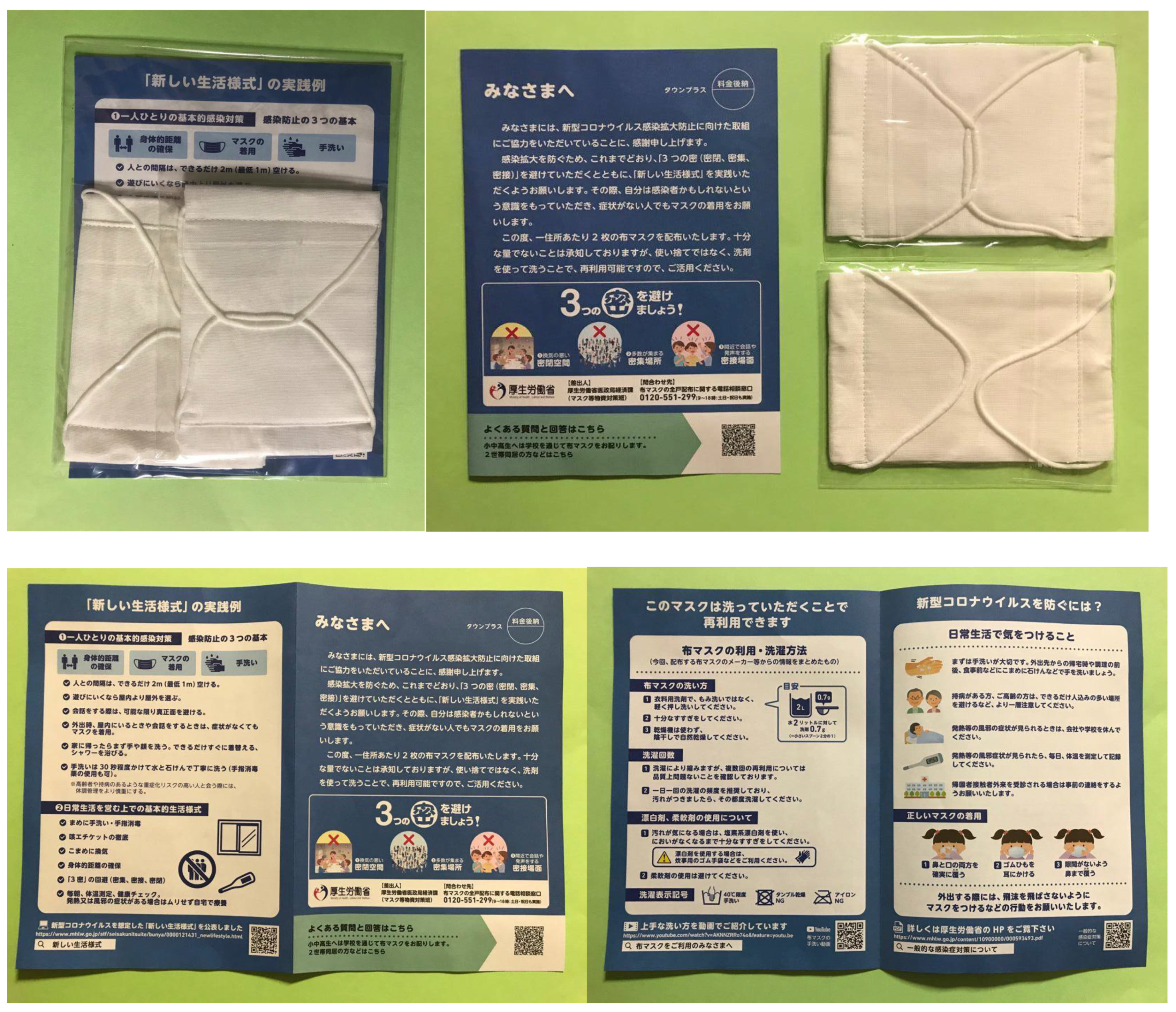

It took about two months for the government to deliver the masks, dubbed “Abenomasks”, a pun on the “Abenomics” economic policy mix promoted by the Abe administration, after the nationwide delivery contracted out to Japan Post began on April 17.

All persons entering or returning from Brazil will be inspected at the airport. Then, we will take them to facilities designated by the Quarantine Department and retest them on the third day after entry (note). Those who test negative will be allowed to leave the designated facility and complete the remainder of the 14-day quarantine (grade) at home. We emphasize that you will not be allowed to use public transport to leave the facilities designated for your residence.

In a time where social research has to go through a significant methodological change to conform to current limitations, which will have an impact on the future of the field itself, it is indeed not the right time to make bold statements. Many researchers are not yet equipped to deal with these ethical and technological novelties. It can be a daunting experience (…).

2. Tracing the Origin: Why Brazilians Immigrants in Japan?

3. Brazilians Immigrants and the Role of Religion Amid Their Lives

3.1. Migration and Religion

According to the 2019 Shukyo Nenkan, the annual religious report of the country’s Cultural Affairs Agency, there are 84,000 Shinto (46.9%), 77,000 Buddhist (42.6%), and 4700 Christian (2.6%) active organizations. There are also 14,000 organizations of other religions (7.9%) not identified by name. Nor are there any distinctions between Roman Catholic and Evangelical Christian churches.

Customary religious practices, such as attending weekly services, lighting candles, burning incense in front of a family altar, and reciting prayers are examples of communal and family rituals, which were brought from the old country to the new. However, these activities often take on new meanings after migration. The normal feeling of loss experienced by immigrants means that familiar religious rituals learned in childhood, such as hearing prayers in one’s native tongue, provide an emotional connection, especially when shared with others. These feelings are accentuated from time to time with the death of a family member or some other tragedy. (…) [R]eligious beliefs and attachments have stronger roots after immigration than before (p. 1211).

3.2. Migration, Religion, and Gender

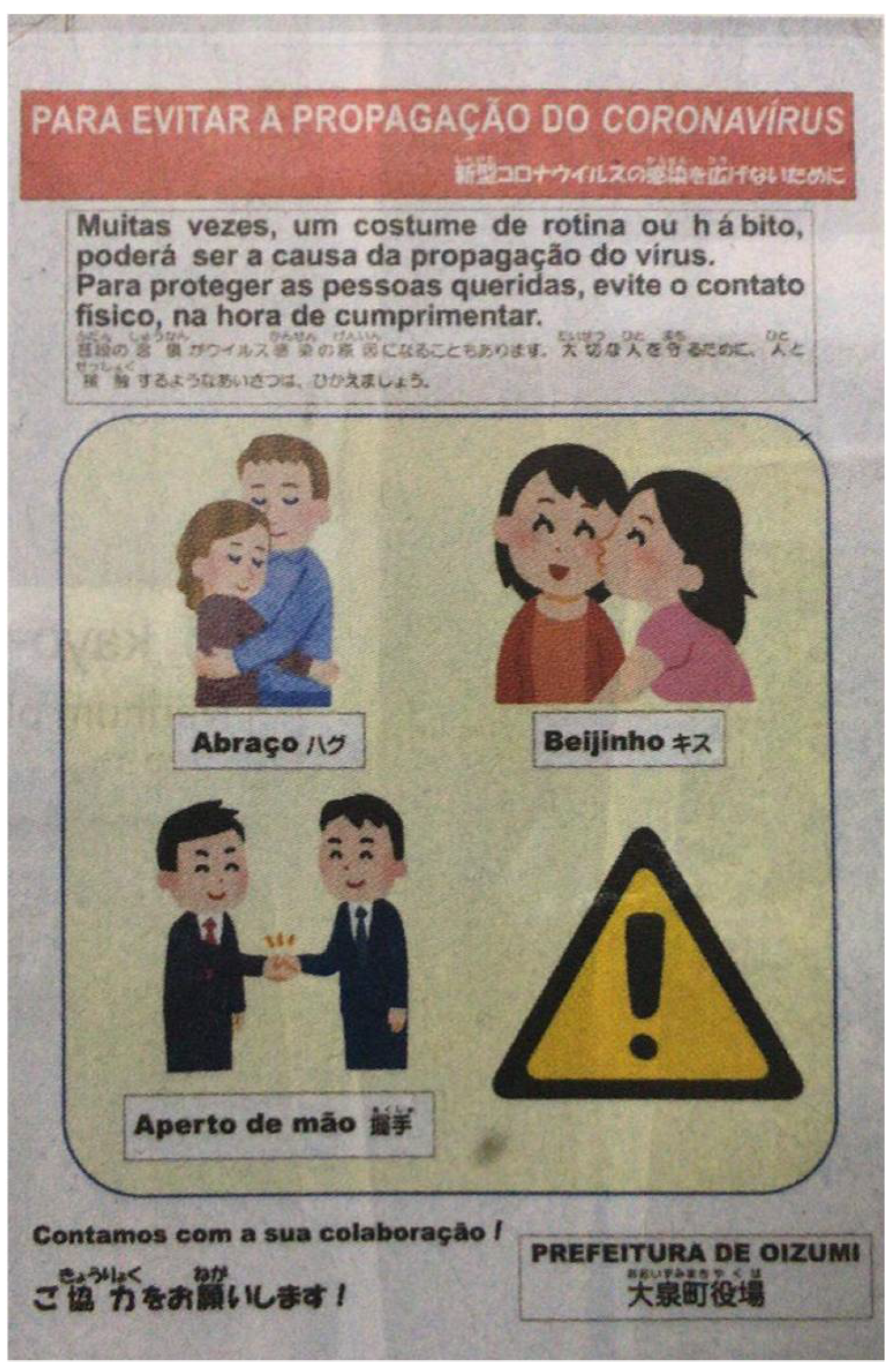

4. Multicultural Interactions in Times of COVID-19

“Despite that apology and retraction, it’s still mind boggling where the original wording came from. All of this could’ve been easily avoided if the health center had just advocated for people to not eat out together in general, and to just wear a mask in general, not specifically pointing out foreigners”.

“Discrimination”.

“Just tell everyone to wear a mask and not eat out. Doing otherwise is discrimination”.

“This just causes more discrimination against foreigners who lived in Japan before COVID, and Japanese people with foreign relatives”.

“I mean, by foreigners, they’re not including Westerners”.

“This is the country that’s going to be hosting the Olympics soon?”

“In an age where ridiculous misinformation about foreigners can spread easily, and taking back that misinformation and replacing it with the truth can be incredibly difficult, it’s at least good to see a somewhat happy ending here. Let’s hope that unfortunate notices likes these won’t need to be retracted in the future, since they just won’t happen in the first place”.

4.1. Lost in (the Lack of) Translation? Health Care and Vaccination Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.2. Quarantine Controversies and the Daily Life of Japanese Brazilian Immigrants

Civil libertarians may argue that an order to evacuate your home—or to stay inside—is an extreme limitation on constitutionally guaranteed rights such as freedom of movement, public assembly, and others. They would be correct. However, constitutional scholars such as professor Hajime Yamamoto of Keio University explain that those rights must be balanced against other constitutional provisions, especially Article 13, which stipulates that the “public welfare” is the highest consideration of all law and government action. There is no doubt that reasonable restrictions calculated to limit the spread of the coronavirus pass constitutional muster.

We hear several possible explanations. One is that the Japanese people are so responsive to official requests they don’t need such orders. Jishuku (self-regulation) really works. Another is that such orders are unnecessary because of Japan’s extremely high standards of hygiene.

5. Religious Discourses and Attitudes towards Self-Care

The Tokyo Olympic games which starts on 23 July and the Tokyo Paralympic games which starts on 24th August will be held in various places but mainly in the Tokyo Metropolitan area. With the declaration of a state of emergency, it is expected that the events will be held without spectators at venues especially in the Tokyo Metropolitan area. But at the same time, the gathering of the athletes and their support staff coming from all over the world raises concerns about causing further increase in number of coronavirus cases. For the past years, the Tokyo Archdiocese had originally been considering preparations so that each parish may be able to address the spiritual needs of the many people who would come to Japan for this international event. However, we have decided to cancel all plans and thus, will not take any special involvement in the Olympics and Paralympics. In addition, all those who will be coming to the Tokyo Metropolitan area during this period will be provided with information concerning the precautionary measures implemented against COVID-19 infection in the parishes and will be requested to refrain from visiting churches.

6. The Struggles of Immigrants: Hearing Their Concerns in Times of COVID-19

6.1. Concerns Related to Daily Life

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on me as a researcher and a professor. First of all, it became impossible to make any research field trips, which was essential for most of my research. Not being able to travel also affected my stress since leaving Japan three times a year was a way for me to cope with the stress that living and working in Japan creates.

Besides that, I had to adapt to new ways of teaching, and it was very frustrating when having to give classes at the same time online and in the classroom. However, since the university allowed me to do it, I decided to give most of my classes in a hybrid form, in the classroom with some of the students while the remaining students attended the courses through Zoom. It was challenging, but it was the best way to cope with the pandemic, and my opinion of being against teaching only online. I didn’t regret my decision because I confirmed that teaching in person, even using the new technologies, is much more effective than online. My biggest hope continues to be hoping for a time when I will go back to making my research field trips.

It has been sixteen months since the Novel Coronavirus started to affect children’s lives in Japan directly. On 2 March 2021, Prime Minister Abe requested all schools to suspend classes, and it has resumed only three months later, on June 2. They were back to school but to a new normal. Children have to wear a mask all the time, even during physical activities, and keep social distance. Typical yearly activities such as sports, music, and art festivals, graduation ceremonies, and graduation trips are not happening or are very restricted.

School club activities [bukatsu] and Sports Lessons [naraigoto] are barely happening. The expression Corona butori3 is a trend in all conversation among parents, especially since children are experiencing weight gain due to the lack of exercise since the beginning of the pandemic. Children’s social life out of school is essentially online. Playdates in the park were replaced by online games, decreasing physical activities even more. Their mental health is a concern as well. I believe that children need a routine, it grounds their life in a way that makes them feel safe, and all the insecurities and uncertainties caused by the pandemic bring a lot of anxiety. They cannot plan. As an example, my eldest son’s graduation trip has already been postponed three times. They have no idea if they will have it soon or if they will have a proper graduation ceremony at all.

Working directly with the Brazilian community in Japan, I followed the high volume of requests for financial aid, food, and essential hygiene items. That, combined with the vast fear surrounding our community during the COVID-19 pandemic, made me very worried because it became clear that most Brazilians are not in Japan to acquire a solid economic base. They live daily, spending the high monthly salaries earned after eighty or one hundred extra working hours. They do so at the expense of their mental and physical health while buying material goods that do not provide the possibility of gaining stable jobs or the facility to find a new job if necessary. To keep my position, I needed to seek remote solutions to maintain service and support for Brazilians. It was undoubtedly a time of growth and online discoveries that will influence future actions. They provide savings in resources, greater comfort for the organization and participants, and the chance to take information and assistance to people who are distant or unable to move. But it is necessary to admit that the “hiper-digitalization” of the services, events, and information disadvantages the elderly and those who use the internet as a simple entertainment tool.

At the beginning of the pandemic in Japan, the workload decreased a lot at the company where my husband works, and we had to save a lot until he was able to do extra work as a delivery boy for Uber Eats. This additional job was our salvation and how we managed to keep going without the decrease of our economies between June 2020 and April 2021. Insecurity about the future, the lack of perspective of returning to normal workload, and the fear of becoming ill impacted our lives permanently. Although feelings affected the hearts of virtually all of humanity during the pandemic, we knew that our situation was even more delicate. At least in Japan, foreigners are always the first to be dismissed when the companies lay off employees in times of economic crisis.

Facing a pandemic like this in a country where we don’t speak the language and where we don’t have extended family is very difficult. My family is my wife and my friends, but we don’t even see friends anymore because of this pandemic. Everyone was terrified and avoided leaving the house. I think we all get into the home-work-home routine, other than that we go shopping or for some more significant need. It’s sad to have to be isolated, and more tragic is to think that whoever takes COVID can’t count on anyone’s help because they have to be completely isolated. If it is severe, the person goes to a hospital. If it is a mild symptom, the person who lives is only home alone. If they live with their family, they go to a hotel indicated by the health agency not to contaminate other people in the house. But without knowing how to speak, read and write Japanese, everything is much more complex, so I avoid getting infected.

But without working, we cannot stay, and we end up at risk. The work environment has also changed a lot because people no longer have the same relationship with their colleagues. People are more distant. There is no longer that chat at lunchtime or during breaks. Now everyone is in their corner, for example, I don’t stay in the cafeteria, I always have lunch alone in my car. In addition to all this, there is a concern for family and friends in Brazil, it is an unfortunate situation, and I miss them enormously. With the pandemic, it is difficult to travel to Brazil because of the risks and the quarantine rules to enter Japan, which is increasingly strict for foreigners, even if you are a permanent resident like me.

6.2. Concerns Related to Faith and Religion

I was born in a Roman Catholic family, but I left the Christin church after coming to Japan, but not from religion. Here I live in the inaka [inlands], and there is no Roman Catholic church; at least, I never saw one, so I spent months and even years without going to a church. But with this pandemic, I approached the church again through social networks. Before, I even prayed once in a while, but only in times of stress. That is, in those situations that only God could help. But during this pandemic period, I started to listen to celebrations and reflections on biblical passages without realizing it. I cannot explain precisely how this happened, but I realized that the pandemic made me pay attention to religion in a different way, not just praying or mechanically listening to mass. I finally found faith again.

Some friends started sending me links, and out of curiosity, I started to dedicate some time to listen to reflections, prayers, and even celebrations, but everything was very relaxed. Before, I had to go to a church to participate in these activities, which demanded long travel distances to the nearby parish, and spend money and time doing that. Now there are many options on Facebook, Youtube, and WhatsApp directly transmitted from Brazil. I can listen while cleaning the house or doing something else while even feeling at home in Brazil. Before, I had to go to church, but now it seems that the church comes to where I am, even if priests do not make the programs and events. That is very good because we don’t have time for anything else with this busy kaisha [company] life.

From what I know about Brazilian immigrants’ spiritual life in Japan, the pandemic affected their participation, the churches, and the masses. In the first place, the church canceled the masses for a long time. I have witnessed that the situation in Brazil also turned out to be very serious and that many immigrants lost family members due to COVID-19. They had a challenging and worrying time when they didn’t have news of their relatives or missed them because of their death. Most of them could not even attend the funeral because it was impossible to travel at the beginning of the pandemic. On the other hand, since the pandemic, Masses in Japan have been held irregularly. At times, they were allowed, to then prohibited, and later they were allowed with a limited number of participants. Even when it was possible to hold in-person Masses, we noticed far fewer people attending than regular times. I think this is because people are afraid of catching COVID-19 and being out of work. That means not going to work and not being seen at work because of being sick at home or in the hospital. In addition to this, treatment is not cheap, and many people find themselves struggling financially. I believe that these two aspects—the issue of contagion and the economic environment on one side, and the spiritual issue, on the other—were circumstances that made life difficult for the Brazilian people in Japan.

The way Brazilian immigrants found to maintain and nourish their faith during this pandemic was through the internet. That was not only to attend Mass virtually but also to organize among themselves to pray the rosary at some point during the week, set aside times of prayer together, and share daily life situations. At the same time, they have also been able to access a multiplicity of conferences, workshops, and sermons on YouTube. They even access the recorded messages that I also send to the communities as a missionary. All these situations have created resources that maintained their faith and nourished their hope amidst this crisis. However, from October [2021] onwards, it seems that the Masses are going to be in person again, so I am hopeful that people will return to the parishes and begin to have less fear and more courage to return to the Church to find the strength they need to overcome such a difficult situation for everyone as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Here in Japan, I have been actively participating in Seicho-no-Ie for more than ten years. I have always loved it, but with the pandemic, everything has changed. In the past, we had meetings, events, and everything was very lively. We went to people’s houses to pray, but now people don’t do that anymore. With the pandemic, everything went online. For me, what changed is that now I attend the meetings in Brazil through Facebook. I like it very much because the meetings there are very well prepared. Besides, the speakers in Brazil are very different. I feel that they show affection; they speak from their hearts. Here in Japan, we also have virtual meetings, but it is very different. I think that people here are already very “Japanese”; they don’t express their feelings. I am feeling a massive difference between the virtual meetings in Brazil and the ones here. That is very strange because I have known people here for so long, but I feel more at ease with the people from Brazil. I feel freer to talk and ask, and feel more welcome. Because of the pandemic, the staff is not doing many study sessions as it has canceled the face-to-face meetings. They have done many debates, and it gets a very rare atmosphere. I am terrified, and I feel a little embarrassed to speak in front of them. But the worst thing is that here in Japan everybody is very busy, so when we need advice or call to ask something or talk, we realize that some of the preachers or coordinators don’t always have time to pay attention to us, which is very bad.

With the pandemic, everything got worse because the older people have difficulty using Facebook or Zoom, and the coordinators don’t always correctly explain how we should access the meetings. I think the whole shift was not very good because many people have difficulty using the apps. It seems that only those who have more knowledge participate, and some of us are a little unable to participate. I try to help people who call me asking how to do it, but sometimes even I can’t log in. I don’t know what happens because the lecturer in my city in Brazil, always sends me the link and I can enter correctly, but the one here often left me with a problem. With this pandemic, many people ask me for prayers; everybody requires prayers, but I think this online thing is not working very well because many people need special attention and don’t have it. So, in my case, what changed the most is that I started to participate in the online activities of Seicho-no-Ie in Brasil because I think that the people there show the feelings from the bottom of their hearts. However, I heart for the older adults who have no one to help them and become strange to their communities due to technology issues.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Alternativa magazine was launched on 24 May 2001, and has completed twenty years of services to the Brazilian community in Japan. In addition to the printed version—of free distribution, readers can find it on the internet as Alternativa Online (https://www.alternativa.co.jp/) (accessed on 31 July 2021). |

| 2 | Pseudonyms replaced real names in this secton to protect the anonymity and privacy of our interviewees. |

| 3 | The expression Corona butori [コロナ太り] conveys the idea of people gaining weight due to staying at home all day in light of the Coronavirus pandemic. |

References

- Agência France Presse. 2020. Três japoneses retirados de Wuhan estão infectados com novo coronavírus. Correio Braziliense. January 30. Available online: https://www.correiobraziliense.com.br/app/noticia/mundo/2020/01/30/interna_mundo,824405/tres-japoneses-retirados-de-wuhan-estao-infectados-novo-coronavirus.shtml (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Akiyama, Shinichi. 2020. Japan Finishes Distributing ‘Abenomasks’ to all Households after 2 Months. The Mainichi Shimbum. June 26. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20200626/p2a/00m/0na/002000c (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- BBC. 2020a. Coronavirus: Japan Declares Nationwide State of Emergency. BBC News. April 16. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52313807 (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- BBC. 2020b. Yoshihide Suga Elected Japan’s New Prime Minister Succeeding Shinzo Abe. BBC News. September 16. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-54172461 (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Busetto, Arielle. 2020. Japan’s $1000 Coronavirus Cash Handout to Citizens: What You Need to Know. Japan Forward. April 17. Available online: https://japan-forward.com/japans-1000-coronavirus-cash-handout-to-citizens-what-you-need-to-know/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Cabinet Secretariat. 2020. [COVID-19] Press Conference by the Prime Minister Regarding the Declaration of a State of Emergency. April 7. Available online: https://japan.kantei.go.jp/98_abe/statement/202004/_00001.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Carpenter, Robert T., and Wade Clark Roof. 1995. The Transplanting of Seicho-no-Ie From Japan to Brazil: Moving Beyond the Ethnic Enclave. Journal of Contemporary Religion 10: 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Peter B. 1999. Japanese New Religious Movements in Brazil: From Ethnic to ‘Universal’ Religions. In New Religious Movements: Challenge and Response. Edited by Bryan Wilson and Jamie Cresswell. London: Routledge, pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Consulado Geral do Japão em São Paulo. 2021. Comunicado Sobre as Medidas do Governo do Japão e Solicitações de Visto Relacionadas à Infecção pelo novo Coronavírus. March 22. Available online: https://www.sp.br.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_pt/not_21_03_coronavirus99.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Córdova Quero, Hugo, and Michael S. Campos. 2020. Transgressing Quarantine: Queering, Theologizing, and Traversing Virtual and Real Bodies. Santiago de Chile and Bogotá: GEMRIP Ediciones/IADLA Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova Quero, Hugo, and Rafael Shoji. 2014. Introduction: On Transnational Faiths and Their Faithfuls. In Transnational Faiths: Latin-American Immigrants and Their Religions in Japan. Edited by Hugo Córdova Quero and Rafael Shoji. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova Quero, Hugo, Melanie Perroud, Alberto Fonseca Sakai, and Jane H. Yamashiro. 2008. Deconstructing Nikkei: Politics of Representation among People of Japanese Ancestry Migrating from the Americas to Japan. Migrations and Identities 1: 115–31. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova Quero, Hugo. 2007. Worshiping in (Un)Familiar Land: Brazilian Migrants and Religion in Japan. Encontros Lusofonos 9: 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova Quero, Hugo. 2008. Encounter Between Worlds: Faith and Gender among Brazilian Migrants in Japan. The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies 26: 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova Quero, Hugo. 2009. Promised Land(s)? Ethnicity, Cultural Identity, and Transnational Migration among Japanese Brazilian Workers in Japan. Iberoamericana 31: 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova Quero, Hugo. 2010. Faithing Japan: Japanese Brazilian Migrants and the Roman Catholic Church. In Gender, Religion and Migration: Pathways of Integration. Edited by Glenda Tibe Bonifacio and Vivienne S. M. Angeles. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova Quero, Hugo. 2013. Del discurso a la praxis pastoral. Dilema de la Iglesia Católica Romana en Japón frente a los inmigrantes japoneses brasileños. Anatéllei 15: 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova Quero, Hugo. 2014. Made in Brazil? Sexuality, Intimacy, and Identity Formation among Japanese Brazilian Queer Immigrants in Japan. In Queering Migrations Towards, From, and Beyond Asia. Edited by Hugo Córdova Quero, Joseph N. Goh and Michael Sepidoza Campos. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova Quero, Hugo. 2016. Embodied (Dis)Placements: The Intersections of Gender, Sexuality, and Religion in Migration Studies. In Intersections of Religion and Migration: Issues at the Global Crossroads. Edited by Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Jennifer B. Saunders and Susanna Snyder. Religion and Global Migrations series #1. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 151–71. [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho, Daniela. 2003. Migrants and Identity in Japan and Brazil: The Nikkeijin. London: Routledge Curzon. [Google Scholar]

- De Paiva, Geraldo José. 2005. Novas religiões japonesas e sua inserção no Brasil: Discussões a partir da psicologia. Revista USP 67: 208–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Nilta. 2015. Dekasseguês: Um português diferente? Variações linguísticas e interculturalidade nas migrações contemporâneas dentro do sistema-mundo moderno. Horizontes Decoloniales 1: 62–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, Nilta. 2017. Crianças e jovens brasileiros no Japão: Educação, cultura e inquietudes. Quaestio: Revista de Estudos em Educação 19: 607–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dias, Nilta. 2018. «Não há lugar para mim na casa de Deus?»: Identidade e espiritualidade de lésbicas brasileiras na região de Kanto, Japão. Conexión Queer: Revista Latinoamericana y Caribeña de Teologías Queer 1: 15–48. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, Naoto, and Kiyoto Tanno. 2003. What’s Driving Brazil-Japan Migration? The Making and Remaking of the Brazilian Niche in Japan. International Journal of Japanese Sociology 12: 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, Charles. 2004. The Role of Religion in the Origins and Adaptations of Immigrant Groups. The International Migration Review 38: 1206–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, Fatima. 2020. Como a resposta ao coronavírus está derrubando a popularidade do primeiro-ministro do Japão. BBC News Brasil. April 17. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/internacional-52304842 (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Kawaguchi, Kaoru. 2007. Toward a Multi-Cultural Church Community. The Japan Mission Journal 61: 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kiko, Hachima. 2021. Ibaraki Health Center Warns People not to Eat with Foreigners to Prevent Spreading COVID. Japan Today. May 23. Available online: https://japantoday.com/category/national/Ibaraki-health-center-warns-people-not-to-eat-with-foreigners-to-prevent-spreading-COVID (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Kikuchi, Tarcisio Isao. 2021. Olympics, Churches Closed to Athletes to Stop Covid Contagion. AsiaNews.it. July 12. Available online: http://www.asianews.it/news-en/Olympics,-churches-closed-to-athletes-to-stop-Covid-contagion-53622.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Kyodo News. 2017. Babysitters in Great Demand Amid Daycare Shortage in Japan. November 20. Available online: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2017/11/e30d7048e1f7-babysitters-in-great-demand-amid-daycare-shortage-in-japan.html?phrase=north%20korea&words= (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Kyodo News. 2020. Gov’t Sued over Disclosure of ‘Abenomask’ Unit Price, order Numbers. September 28. Available online: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2020/09/2f22e10b0943-govt-sued-over-disclosure-of-abenomask-unit-price-order-numbers.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Kyodo News. 2021. Tokyo Hotel Rapped for ‘Japanese only’ Notice for Elevator Use. July 11. Available online: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2021/07/aa2015e76a9e-tokyo-hotel-rapped-for-japanese-only-notice-for-elevator-use.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Kyodo Staff Reporter. 2020. Japan Confirms First Case of Coronavirus that has Infected Dozens in China. The Japan Times. January 16. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/01/16/national/science-health/japan-first-coronavirus-case/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Leussink, Daniel. 2020. PM Abe Asks all of Japan Schools to Close over Coronavirus. Reuters. February 27. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-japan-idUSKCN20L0BI (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Linger, Daniel Touro. 2001. No One Home: Brazilian Selves Remade in Japan. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, Masamichi. 2021a. Gunma relata 60 casos de coronavírus em igreja da Assembleia de Deus. Alternativa. January 14, p. 519. Available online: https://www.alternativa.co.jp/Noticia/View/88603/Gunma-relata-60-casos-de-coronavirus-em-igreja-da-Assembleia-de-Deus (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Maeda, Masamichi. 2021b. Aichi quer proibir uso de igreja em Toyota após 36 casos de Covid no local. Alternativa. April 14, p. 523. Available online: https://www.alternativa.co.jp/Noticia/View/89470/Aichi-quer-proibir-uso-de-igreja-em-Toyota-apos-36-casos-de-Covid-no-local (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Matsue, Regina. 2003. Overseas Japanese New Religion: The Expansion of Sekai Kyuseikyo in Brazil and Australia. Yakara: Studies in Ethnology 33: 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Matsue, Regina. 2006. Religious Activities Among the Japanese-Brazilians ‘Dual Diaspora’ in Japan. In Religious Pluralism in the Diaspora. Edited by P. Pratap Kumar. International Studies in Religion and Society #4. Leiden: Brill, pp. 121–46. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, Hideaki. 2004. Burajirujin to Nihon Shyukyo Sekai Kyuseikyo no Fukyo to Jyuyo [Brazilians and a Japanese New Religion]. Tokyo: Kobundo. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, Hideaki. 2007. Japanese Prayer Below the Equator: How Brazilians Believe in the Church of World Messianity. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- McCurry, Justin. 2020. Japan Lifts State of Emergency after Fall in Coronavirus Cases. The Guardian. May 25. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/25/japan-lifts-state-of-emergency-after-fall-in-coronavirus-cases (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- McLaughlin, Levi. 2020. Japanese Religious Responses to COVID-19: A Preliminary Report. Japan Focus: The Asia-Pacific Journal 18: 1–22. Available online: https://apjjf.org/2020/9/McLaughlin.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science, and Technology of Japan (MEXT). 2020a. Information on MEXT’s Measures against COVID-19. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/en/mext_00006.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science, and Technology of Japan (MEXT). 2020b. Os Esforços Feitos Para Garantir o Aprendizado nas Escolas Japonesas Devido ao Novo Coronavírus. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/coronavirus/1411020_00004.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 2021. Border Enforcement Measures to Prevent the Spread of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). August 2. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/ca/fna/page4e_001053.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Ministry of Justice of Japan. 2007. Zairyuu Gaikokujin Toukei (Statistics of Foreign Residents). Tokyo: Japan Immigration Association. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice of Japan. 2015. Zairyuu Gaikokujin Toukei (Statistics of Foreign Residents). Tokyo: Japan Immigration Association. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice of Japan. 2020. Zairyuu Gaikokujin Toukei (Statistics of Foreign Residents). Tokyo: Japan Immigration Association. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism of Japan. 2020. Summary of The White Paper on Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in Japan, 2020. Tokyo: Policy Bureau, MLITTJ. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, Mark. 2006. Between Inculturation and Globalization: The Situation of Roman Catholicism in Contemporary Japan. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Academy of Religion, Washington, DC, USA, November 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 1997. Constructing Love, Desire, and Care. In Sex, Preference, and Family: Essays on Law and Nature. Edited by David M. Estlund and Martha C. Nussbaum. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 17–43. [Google Scholar]

- Osaki, Tomohiro. 2020. Abenomask? Prime Minister’s ‘two Masks per Household’ Policy Spawns Memes on Social Media. The Japan Times. April 2. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/04/02/national/abe-two-masks-social-media/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Osumi, Magdalena. 2020. Naha goes on high alert, days after visit by virus-hit cruise ship. The Japan Times. February 5. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/02/05/national/science-health/naha-alert-coronavirus-last-week-quarantine-cruise-ship/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Pasteur de Faria, Louise Scoz. 2020. Doing Research in a Pandemic: Shared Experiences from the Fieldwork. Halo Ethnographic Bureau. May 6. Available online: https://medium.com/halobureau/doing-research-in-a-pandemic-shared-experiences-from-the-fieldwork-fa1a00fc86fc (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Pye, Michael. 2011. Distância cultural na transplantação de religiões japonesas em países distantes. REVER 11: 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford Ruether, Rosemary. 1993. Sexism and God-Talk: Toward a Feminist Theology. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Repeta, Lawrence. 2020. The coronavirus and Japan’s Constitution. The Japan Times. April 14. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2020/04/14/commentary/japan-commentary/coronavirus-japans-constitution/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Reuters. 2020. Health Minister Apologizes after 23 Passengers Let off Diamond Princess without Additional Coronavirus Tests. The Japan Times. February 22. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/02/22/national/coronavirus-chiba-kumamoto/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Roth, Joshua Hotaka. 2002. Brokered Homeland: Japanese Brazilian Migrants in Japan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Miko, Ichiro Itoda, Hirokazu Kimura, Naoki Onizuka, Seiichi Ichikawa, Hiroshi Hasegawa, Masahiro Matsuo, Yosuke Terao, and Ken Hasimoto. 2001. “Tokyochiiki ni Okeru HIV/STD Kansen Yobou no Suishin ni Kansuru Kenkyu” [Research on the Promotions for Prevention of HIV/STD Infection in Tokyo]. In HIV Kansensho no Doukou to Yoboukainyu ni Kansuru Shakai-Ekigaku-Teki Kenkyu [Annual Report of the Study Group on Socioepidemiological Studies on Monitoring and Prevention of HIV/AIDS]. Edited by Kihara Masahiro. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, pp. 122–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sayuri, Juliana. 2020. Missionários dekasseguis: Como imigrantes brasileiros espalham o Evangelho no Japão. UOL Brasil. September 23. Available online: https://noticias.uol.com.br/ultimas-noticias/bbc/2020/09/23/missionarios-dekasseguis-como-os-imigrantes-brasileiros-espalham-o-evangelho-no-japao.htm (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Sayuri, Juliana. 2021. Consulado no Japão recebe cartas contra brasileiros em cidade foco de covid. UOL Brasil. July 15. Available online: https://www.uol.com.br/esporte/olimpiadas/ultimas-noticias/2021/07/15/japoneses-protestam-contra-brasileiros-em-cidade-com-foco-de-covid-19.htm?cmpid=copiaecola (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Schüssler Fiorenza, Elizabeth. 1994. In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins. New York: Crossroads. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, Gaku. 2020. A Legacy Slipping Away: Why Shinzo Abe Stepped Down. Nikkei Asia. August 30. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Inside-Japanese-politics/A-legacy-slipping-away-Why-Shinzo-Abe-stepped-down (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Sugiyama, Satoshi. 2020. Japan to Lift Coronavirus State of Emergency in 39 Prefectures: The Nation’s Capital and Seven Prefectures will Maintain Emergency Measures for Now. The Japan Times. May 14. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/05/14/national/japan-coronavirus-emergency-39-prefectures/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Sumimoto, Tokihisa. 2000. Religious Freedom Problems in Japan: Background and Current Prospects. The International Journal of Peace Studies. 5. Available online: https://www.gmu.edu/programs/icar/ijps/vol5_2/sumimoto.htm (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Suppasri, Anawat, Miwako Kitamura, Haruka Tsukuda, Sebastien P. Boret, Gianluca Pescaroli, Yasuaki Onoda, Fumihiko Imamura, David Alexander, Natt Leelawat, and Syamsidike. 2020. Perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan with respect to cultural, information, disaster and social issues. Progress in Disaster Science 10: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Kazuto. 2020. Pandemic shows Japan needs to figure out how to learn and prepare. The Japan Times. July 20. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2021/07/20/commentary/japan-commentary/japan-last-minute-vaccines/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Takahashi, Ryusei. 2021. COVID-19 spreads quietly in the shadow of the Olympics. The Japan Times. July 26. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/07/26/national/olympic-virus-cases-july-26/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Takenaka, Kiyoshi. 2020. Two Japanese evacuated from Wuhan have pneumonia symptoms, second flight being dispatched. Reuters. January 28. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-china-health-japan/two-japanese-evacuated-from-wuhan-have-pneumonia-symptoms-second-flight-being-dispatched-idUKKBN1ZS02T (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Talmadge, Eric. 1996. Japan Faces AIDS Scandal. Available online: http://www.aegis.com/news/ap/1996/AP961211.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Todaro, Michael P. 1969. A Model of Labor Migration and Urban Un-employment in Less Developed Countries. American Economic Review 59: 138–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda, Takeyuki. 2000. Migration and Alienation: Japanese-Brazilian Return Migrants and the Search for Homeland Abroad. The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies Working Papers no. 24. San Diego: The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies/University of California at San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda, Takeyuki. 2003. Strangers in the Ethnic Homeland: Japanese Brazilians Return Migration in Transnational Perspective. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- US Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 2018. International Religious Freedom Report for 2018; Washington, DC: United States Department of State. Available online: https://www.state.gov›uploads›2019/05›JAPAN-2018-INTERNATIONAL-RELIGIOUS-FREEDOM-REPORT.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Vatican News. 2020. Arcebispo de Tóquio: Oportunidade para redescobrir poder da oração e aprofundar vida espiritual. Vatican News. March 26. Available online: https://www.vaticannews.va/pt/igreja/news/2020-03/arcebispo-toquio-coronavirus-redescobrir-poder-oracao.html (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Yamanaka, Keiko. 2003. Feminization of Japanese Brazilian Labor Migration to Japan. In Searching for Home Abroad: Japanese Brazilians and Transnationalism. Edited by Jeffrey Lesser. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 163–200. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro, Jane H. 2008. Nikkeijin. In Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society. Edited by Richard T. Schaefer. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 983–85. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro, Jane H., and Hugo Córdova Quero. 2012. Negotiating Unequal Transpacific Capital Transfers: Japanese Brazilians and Japanese Americans in Japan. In Transnational Crossroads: Remapping the Americas and the Pacific. Edited by Camilla Fojas and Rudy Guevarra. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 403–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yamawaki, Keizo. 2007. The Challenges of the Japanese Social Integration Policy. Paper presented at the DIJ Forum of the German Institute for Japanese Studies, Yotsuya, Tokyo, Japan, April 12. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Córdova Quero, H.; Dias, N. Riding the Wave: Daily Life and Religion among Brazilian Immigrants to Japan in the Age of COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions 2021, 12, 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110943

Córdova Quero H, Dias N. Riding the Wave: Daily Life and Religion among Brazilian Immigrants to Japan in the Age of COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions. 2021; 12(11):943. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110943

Chicago/Turabian StyleCórdova Quero, Hugo, and Nilta Dias. 2021. "Riding the Wave: Daily Life and Religion among Brazilian Immigrants to Japan in the Age of COVID-19 Pandemic" Religions 12, no. 11: 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110943

APA StyleCórdova Quero, H., & Dias, N. (2021). Riding the Wave: Daily Life and Religion among Brazilian Immigrants to Japan in the Age of COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions, 12(11), 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110943