Online Temptations: Divorce and Extramarital Affairs in Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Islam and Family Dynamics in Contemporary Kazakhstan

1.2. ICTs and Extramarital Affairs in Muslim Central Asia

2. Methodology

2.1. Regressions

2.2. Focus Groups

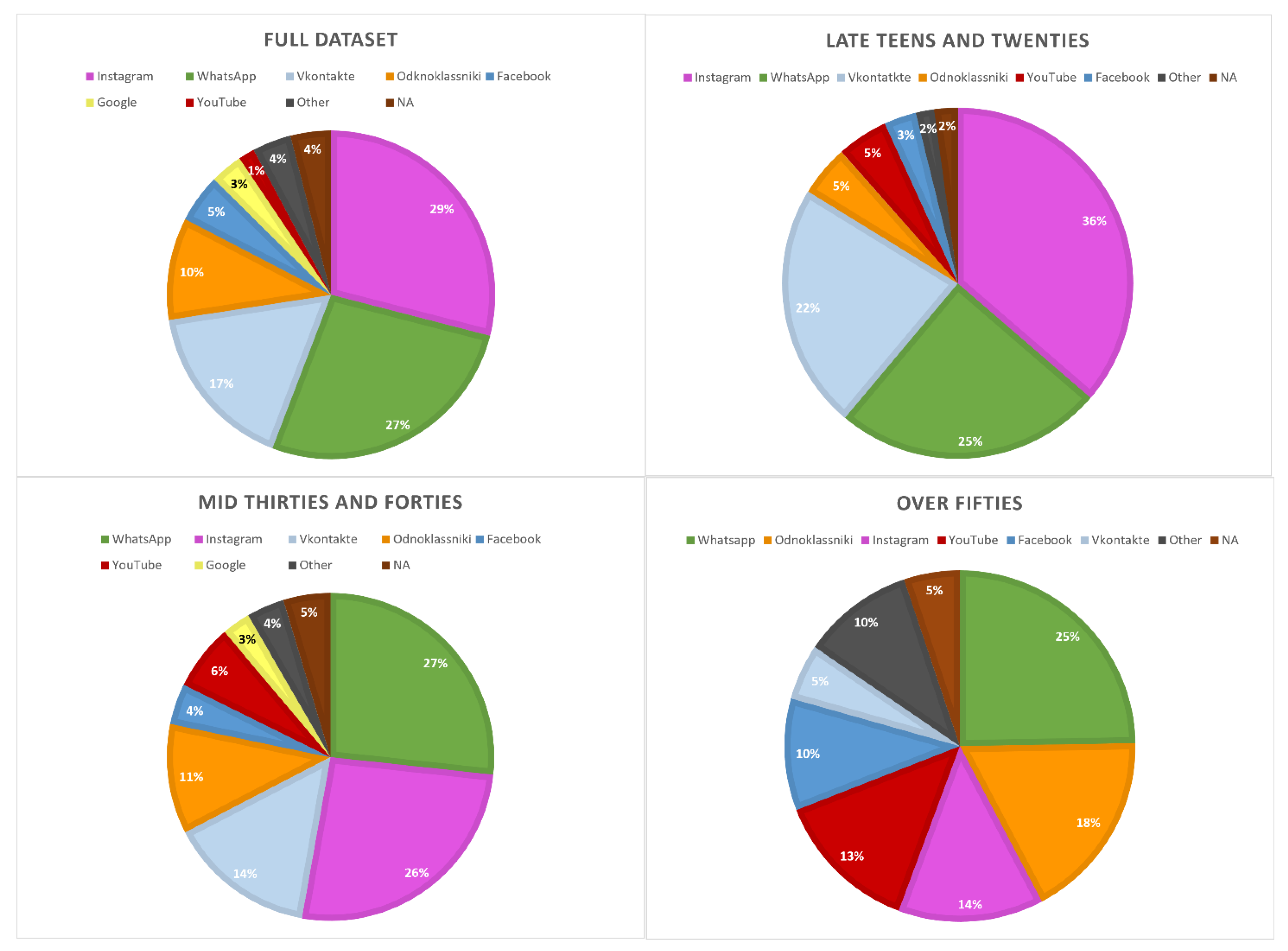

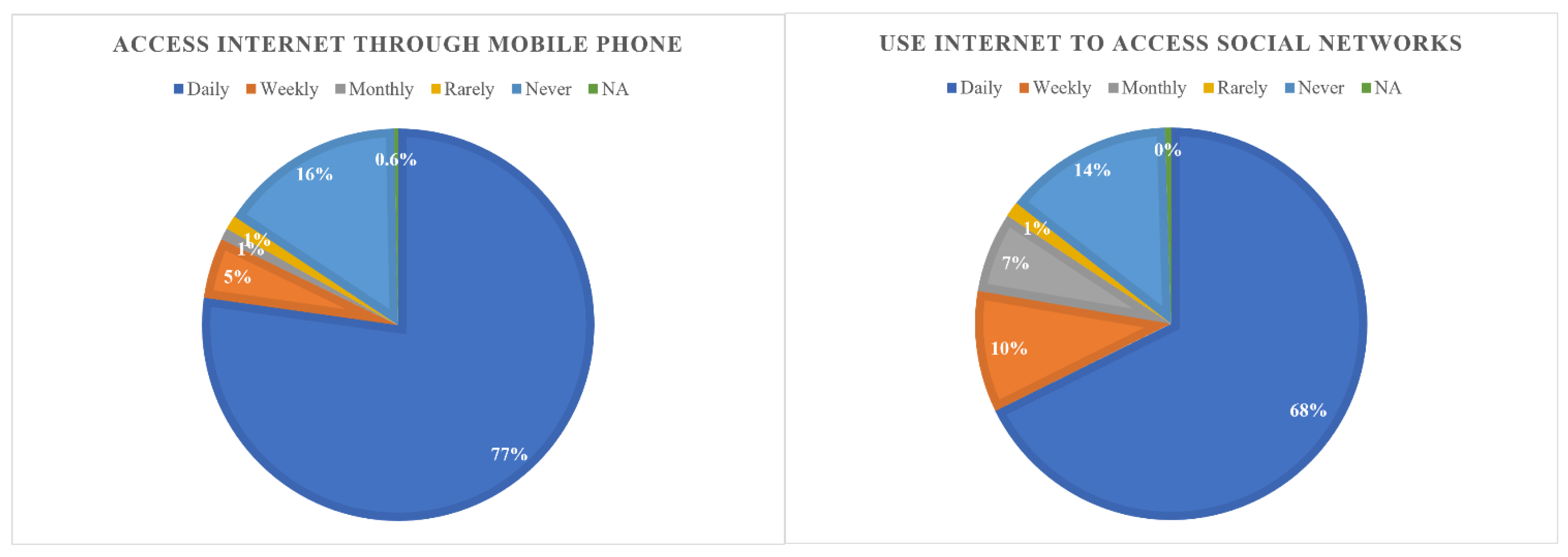

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Focus Groups Analysis

Gaisha: “I think it is good that our cultural habits are changing through the contact with foreigners on social media sites. Thanks to this, we have many international couples today in Kazakhstan. Most couples remain together. However, in particular women fear that relatives oppose their decision to get married to a non-Kazakhstani. My personal opinion is that we live in a free country and that we have the right to fall in love with whomever we want to. (…) I believe that these mixed racial marriages will increase because people learn about other peoples’ lifestyles on Instagram and Facebook. Moreover, peoples’ approval of interethnic marriages differs across the different regions in Kazakhstan. Some families are more open towards such things and others are not ready to accept them”.

Zarina: “These people are fossils [refers to people who reject interethnic marriages]! Cultured (civilized) people will embrace them”.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | Kazakhstan is a multiethnic country and in this article, Kazakhstanis refer to all citizens of Kazakhstan, regardless of their ethnic identity and Kazakhs to those who self-identify as “ethnic Kazakhs”. As a result of Soviet colonization, ethnic identities were crystallized in official documents and remained a strong identity marker. The people interviewed for this article all self-identified as Kazakhs and Muslims. |

| 2 | Homosexuality was even criminalized during long periods of time in the USSR (Kon 1995). |

| 3 | http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 14 July 2021). |

| 4 | In both the Russian as well as the Kazakh WVS 7, survey respondents were asked to what extent they believe that divorce [Razvod (Russian), Azhyrasu (Kazakh)] or casual sex [Sluchaĭnye seksualnye svyazi (Russian), Kezdeĭsok seksualdy baĭlanystar (Kazakh)] are justified [V Kakoĭ stepeni eto deĭstvie, na Vash vzglyiad, mozhet byt’ opravdano? (Russian). Sonymen, kanshalykty oryndy dep oĭlaĭsyz? (Kazakh).] |

| 5 | Zheng et al. (2017), in their study on online sexual activity in China, found that married people were more likely to engage in online sexual activities and therefore had more experience in online sexual activities than single people. |

| 6 | Ninety One is a popular boys band, inspired by Korean pop music (known as Q-pop in Kazakhstan). Their androgynous looks and colorful outfits made them very unpopular among conservative circles in Kazakhstan, who accused them of insulting national culture (Tan 2021). |

| 7 | FG 18, male participant aged 58, Shymkent/FG 19, female participant aged 43, Shymkent. |

| 8 | FG 4, female participant aged 59, Aktau. |

| 9 | FG 16, female participants aged between 22 and 45, Kyzylorda. |

| 10 | FG 11, unmarried male participant aged 24, Nur-Sultan. |

| 11 | FG 18, male participant aged 58, Shymkent. |

| 12 | FG 3, male Kazakhs aged 32 and 33, Aktau/FG 2, male Kazakh aged 24, Aktau. |

| 13 | FG 8, female participant aged 42, Almaty. |

| 14 | FG 4, female participants aged 29, 37 and 59, Aktau/FG 19, female participants aged 28 and 43, Shymkent. |

| 15 | FG 5, female students aged 22, 23 and 23, Almaty/FG 20, female students aged 23, 29, Shymkent/FG 1, female students aged 19 and 20, Aktau. |

| 16 | FG 2, female participants aged 26 and 26, Aktau |

| 17 | FG 17, male participants aged between 22 and 42, Kyzylorda. |

| 18 | FG 3, male participants aged 32 and 33, Aktau. |

| 19 | FG 17, male participant aged 41, Kyzylorda. |

| 20 | FG 9, male participant aged 60, Nur-Sultan. |

| 21 | FG 5, female students aged 22, 23 and 23, Almaty. |

| 22 | FG 20, female students aged 23, 29, Shymkent. |

| 23 | FG 1, female students aged 19 and 20, Aktau. |

References

- Are, Carolina. 2020. How Instagram’s Algorithm is Censoring Women and Vulnerable Users but Helping Online Abusers. Feminist Media Studies 20: 741–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arystanbek, Aizada. 2020. Trapped between East and West: A Study of Hegemonic Femininity in Kazakhstan’s Online and State Discourses. Master’s Thesis, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Judith, and Peter Finke. 2019. Practices of Traditionalization in Central Asia. Central Asian Survey 38: 310–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigozhin, Ulan. 2019. We Love Our Country in Our Own Way: Youth, Gender & Nationalism. In The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan. Edited by Marlene Laruelle. New York: Lexington Books, pp. 115–32. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, Douglas. 2016. The Social Process of Globalization. Return Migration and Cultural Change in Kazakhstan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, Douglas. 2019. Return Migration from the United States: Exploring the Dynamics of Cultural Change. In The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan. Edited by Marlene Laruelle. New York: Lexington Books, pp. 213–25. [Google Scholar]

- Borisova, Elena. 2021. ‘Our Traditions Will Kill Us!’: Negotiating Marriage Celebrations in the Face of Legal Regulation of Tradition in Tajikistan. Oriente Moderno 100: 147–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Zackery. 2016. Married and Previously Married Men and Women’s Perception of Communication on Facebook with the Opposite Sex: How Communicating through Facebook Can Be Damaging to Marriages. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 57: 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Asia Barometer Data, Kazakhstan, Wave 4. 2018. Available online: http://www.ca-barometer.org (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Chakraborty, Kabita. 2012. Virtual Mate-seeking in the Urban Slums of Kolkata, India. South Asian Popular Culture 10: 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleuziou, Juliette, and Julie McBrien. 2021. Marriage Quandaries in Central Asia. Oriente Moderno 100: 121–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleuziou, Juliette, and Lucia Direnberger. 2016. Gender and Nation in Post-Soviet Central Asia. From National Narratives to Women’s Practices. Nationalities Papers 44: 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleuziou, Juliette. 2021. “What Does Marriage Stand for?” Getting Married and Divorced in Contemporary Tajikistan. Oriente Moderno 100: 248–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Agnola, Jasmin. 2020. Queer Culture and Tolerance in Kazakhstan. In PC on Earth. The Beginnings of the Totalitarian Mindset. Edited by Jasmin Dall’Agnola and Jabbar Moradi. Stuttgart and New York: ibidem, Columbia University Press, pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Agnola, Jasmin. 2021. The Impact of Globalization on National Identities in Post-Soviet Societies. Ph.D. dissertation, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- de Lenne, Orpha, Laurens Wittevronghel, Laura Vandenbosch, and Steven Eggermont. 2019. Romantic Relationship Commitment and the Threat of Alternatives on Social Media. Personal Relationships 26: 680–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizza, Iqbal, and Jami Humaira. 2019. Effect of Facebook Use Intensity Upon Marital Satisfaction Among Pakistani Married Facebook Users: A Model Testing. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research; Islamabad 34: 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes. 2020. 73% kazakhstantsev Schitayut Sem’yu Smyslom Zhizni—Sotsissledovaniye (73% of Kazakhstanis Consider Family to be the Meaning of Life—Social Research). Forbes. May 16. Available online: https://forbes.kz/news/2020/05/16/newsid_225465 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Friedrich Ebert Foundation Report. 2019, In Tsennosti Kazakhstanskovo obshchestva v sotsiologicheskom izmerenii. Almaty: Deluxe Printery.

- Haerpfer, Christian, Ronald Inglehart, Alejandro Moreno, Christian Welzel, Kseniya Kizilova, Jaime Diez-Medrano, Marta Lagos, Pippa Norris, Eduard Ponarin, Bi Puranen, and et al., eds. 2020. World Values Survey: Round Seven—Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid and Vienna: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, Rico. 2019. The Kazakhstan Now! Hybridity and Hipsters in Almaty. Negotiating Global and Local Lives. In The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan. Edited by Marlène Laruelle. New York: Lexington Books, pp. 227–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kabatova, Karlygash. 2019a. Overcoming a Taboo. Normalizing Sexuality Education. In The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan. Edited by Marlène Laruelle. New York: Lexington Books, pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kabatova, Karlygash. 2019b. V Poiskakh Zdravogo Smysla Kakaya Sistema Polovogo Prosveshcheniya Nuzhna Kazakhstanu? Almaty: Soros Foundation Kazakhstan. [Google Scholar]

- Kandiyoti, Deniz. 2007. The Politics of Gender and the Soviet Paradox: Neither Colonized, Nor Modern? Central Asian Survey 26: 601–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakhstan Today. 2018. Every Second Marriage Breaks Down in North of Kazakhstan, and Every Fifth—in South. Kazakhstan Today. October 19. Available online: https://www.kt.kz/eng/society/every_second_marriage_breaks_down_in_north_of_kazakhstan_and_every_fifth_in_south_1153664437.html (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Keller, Soshana. 2001. To Moscow Not Mecca: The Soviet Campaign against Islam in Central Asia, 1917–1941. Westport: Praeger Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Simon. 2021. Digital 2021: Kazakhstan. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-kazakhstan (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Khabar. 2021. Gde v Kazakhstane chashche vsego razvodyatsya i zhenyatsya (Where in Kazakhstan People get Divorced and Married Most Often). Khabar. June 1. Available online: https://24.kz/ru/news/social/item/464747-gde-v-kazakhstane-chashche-vsego-razvodyatsya-i-zhenyatsya (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Khegai, Marina. 2020. Pervyy ‘ұyat’ v istorii: Kak nachali stydit’ 100 let nazad. Caravan. June 25. Available online: https://www.caravan.kz/gazeta/pervyjj-uyat-v-istorii-kak-nachali-stydit-100-let-nazad-649436/ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Kikuta, Haruka. 2019. Mobile Phones and Self-Determination among Muslim youth in Uzbekistan. Central Asian Survey 38: 181–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KISD. 2020. “Kazakhstan Families”, Kazakhstan Institute of Public Development «Rukhani zhangyru». Available online: https://kipd.kz/ru/2020-kazahstanskie-semi-nacionalnyy-doklad (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Kon, Igor. 1995. The Sexual Revolution in Russia: From the Age of the Czars to Today. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, Richard, and Mary Casey. 2015. Focus Groups. A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Kudaibergenova, Diana. 2018. Project ‘Kelin’: Marriage, Women and Re-Traditionalization in Post- Soviet Kazakhstan. In Women of Asia: Globalization, Development, and Social Change. Edited by Mehrangiz Najafizadeh and Linda Lindsay. London: Routledge, pp. 379–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kudaibergenova, Diana. 2019. The Body Global and the Body Traditional: A Digital Ethnography of Instagram and Nationalism in Kazakhstan and Russia. Central Asian Survey 38: 363–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laruelle, Marlene. 2019. Introduction: The Nazarbayev Generation: A Sociological Portrait. In The Nazarbayev Generation. Youth in Kazakhstan. Edited by Marlene Laruelle. New York: Lexington Books, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Mbaye, and Taimoor Aziz. 2009. Muslim Marriage Goes Online: The Use of Internet Matchmaking by American Muslims. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Aline. 2020. Love at First Click: Understanding Success in Marriage through the Experience of Online Dating. Ph.D. thesis, Alliant International University, San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Northrop, Douglas. 2004. Veiled Empire: Gender and Power in Stalinist Central Asia. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nurbai, Rabiga. 2020. Razvody v Kazachstane: Prichiny, tendentsii i vyplata alimentov. strategy2050.kz. July 22. Available online: https://strategy2050.kz/ru/news/razvody-v-kazakhstane-prichiny-tendentsii-i-vyplata-alimentov-/ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Pourmehdi, Mansour. 2015. Globalization, the Internet and Guilty Pleasures in Morocco. Sociology and Anthropology 3: 456–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sagadiyeva, Aruzhan. 2021. Social Taboos and Political Legitimation: Debating Polygyny in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan. Master dissertation, Nazarbayev University, Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan. Available online: http://nur.nu.edu.kz/handle/123456789/5390 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Sakhova, Gulzat. 2020. Kak vzyskat’ alimenty s dolzhnikov obsudili predstaviteli KNPK v Almatinskoy oblasti. Inform. October 12. Available online: https://www.inform.kz/ru/kak-vzyskat-alimenty-s-dolzhnikov-obsudili-predstaviteli-knpk-v-almatinskoy-oblasti_a3705159 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Sharifinia, Azadeh, Maryam Nejati, Mohammad Hossein Bayazi, and Hassan Motamedi. 2019. Investigating the Relationship between Addiction to Mobile Social Networking with Marital Commitment and Extramarital Affairs in Married Students at Quchan Azad University. Contemporary Family Therapy 41: 401–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smayyl, Meyirim. 2020. 40 protsentov brakov zakanchivayetsya razvodami v Kazakhstane—issledovaniye. Tengri News. February 18. Available online: https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/40-protsentov-brakov-zakanchivaetsya-razvodami-kazahstane-391959/ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Sotoudeh, Ramina, Roger Friedland, and Janet Afary. 2017. Digital Romance: The Sources of Online Love in the Muslim world. Media, Culture & Society 39: 429–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaĭmonn, Irshod. 2020. V Tadzhikistane za razvod pa telefony lishat’ svobody na budut. Asia-Plus. December 15. Available online: https://asiaplustj.info/ru/news/tajikistan/society/20201215/v-tadzhikistane-za-razvod-po-telefonu-lishat-svobodi-ne-budut (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Sweet-McFarling, Kristen. 2014. Polygamy on the Web: An Online Community for an Unconventional Practice. Master’s Thesis, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Yvette. 2021. The K-Pop Inspired Band That Challenged Gender Norms in Kazakhstan. BBC. January 4. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55359772 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Thibault, Hélène. 2021. The Many Faces of Polygyny in Kazakhstan. Central Asia Program 255. Available online: https://www.centralasiaprogram.org/archives/20019#_ftn22 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Thibault, Hélène. forthcoming. Online Male Sex Work in Kazakhstan: A Distinct Market? Central Asian Affairs. manuscript accepted.

- Titova, Aksiniya. 2020. Kazakhstanskii Rynok Seksual’nykh Uslug Rasshiyaraets (The Kazakhstani Sex Services’ Market Is Widening). Moskovskii Komsololets KZ. October 7. Available online: https://mk-kz.kz/social/2020/10/07/kazakhstanskiy-rynok-seksualnykh-uslug-rasshiryaetsya.html (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Torno, Svetlana. 2017. Tajik in Content—Soviet in Form? Reading Tajik Political Discourse on and for Women. In The Family in Central Asia: New Perspectives. Edited by Sophie Roche. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, pp. 141–61. [Google Scholar]

- UN Demographic Yearbook. 2019. Demographic Yearbook 70th Issue. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/products/dyb/dyb_2019/ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Valenzuela, Sebastián, Daniel Halpern, and James Katz. 2014. Social Network Sites, Marriage Well-Being and Divorce: Survey and State-Level Evidence from the United States. Computers in Human Behavior 36: 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- We Are Social. 2021. Digital 2021. Global Overview Report. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/digital-2021 (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- World Bank. 2019. Individuals Using the Internet (% of Population)—Kazakhstan. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=KZ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Zhang, Jiaping, Mingwang Cheng, Xinyu Wei, and Xiaomei Gong. 2018. Does Mobile Phone Penetration Affect Divorce Rate? Evidence from China. Sustainability 10: 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanko, Tatyana, and Klara Basayeva. 1990. Semeynyy byt narodov SSSR. Moscow: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Lijun, Xuan Zhang, and Yingshi Feng. 2017. The New Avenue of Online Sexual Activity in China: The smartphone. Computers in Human Behavior 67: 190–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Shilin, Yuwei Duanb, and Michael Ward. 2019. The effect of Broadband Internet on Divorce in China. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 139: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhulmukhametova, Zharda. 2018. Issledovanie: 2% devushek do 19 let v Kazakhstane delali aborty v domashnikh usloviyakh. Informburo. December 4. Available online: https://informburo.kz/novosti/issledovanie-2-kazahstanskih-devushek-do-19-let-delali-aborty-v-domashnih-usloviyah.html (accessed on 14 June 2021).

| Place | Date | Focus Group | Gender | Generation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aktau | 19 July 2019 | FG1 | 2 females | 19 and 20 years old |

| 20 July 2019 | FG2 | 4 females, 1 male | 24–28 years old | |

| 20 July 2019 | FG3 | 2 males | 30 and 33 years old | |

| 20 July 2019 | FG4 | 3 females | 30–49 years old | |

| Almaty | 17 June 2019 | FG5 | 3 females | 18–29 years old |

| 27 October 2019 | FG6 | 4 females, 4 males | 30–49 years old | |

| 27 October 2019 | FG7 | 6 females, 1 male | 30–50 years old | |

| 28 October 2019 | FG8 | 5 females | 30–49 years old | |

| Nur-Sultan | 19 October 2019 | FG9 | 3 males, 3 females | 22–60 years old |

| 19 October 2019 | FG10 | 6 females | 22–47 years old | |

| 20 October 2019 | FG11 | 6 males | 22–44 years old | |

| 28 January 2020 | FG12 | 6 females | 18–21 years old | |

| 28 January 2020 | FG13 | 5 males | 18–21 years old | |

| 29 January 2020 | FG14 | 3 males, 3 females | 18–21 years old | |

| Kyzylorda | 2 November 2019 | FG15 | 3 males, 3 females | 21–47 years old |

| 2 November 2019 | FG16 | 6 females | 22–45 years old | |

| 3 November 2019 | FG17 | 6 males | 22–42 years old | |

| Shymkent | 13 July 2019 | FG18 | 1 male, 3 females | 40–58 years old |

| 13 July 2019 | FG19 | 2 females | 28 and 43 years old | |

| 14 July 2019 | FG20 | 2 females | 23 and 29 years old |

| Internet | Social Media | Mobile Phone | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | 41.1% | 33.2% | 47.5% |

| Weekly | 16.7% | 11.1% | 12.6% |

| Monthly | 7.7% | 7.5% | 7.2% |

| Less than monthly | 8.4% | 9.1% | 10.7% |

| Never | 25.8% | 39.1% | 21.9% |

| Women * | 57.8% | 44.6% | 62.2% |

| Men * | 58.4% | 43.8% | 58.0% |

| 18–29 years old * | 68.0% | 59.2% | 72.8% |

| 30–49 years old * | 58.2% | 45.8% | 60.2% |

| 50+ years old * | 49.3% | 28.1% | 49.3% |

| Married * | 57.4% | 42.9% | 60.4% |

| Divorced * | 69.4% | 53.1% | 63.3% |

| Single * | 55.9% | 44.9% | 58.3% |

| Parent * | 54.6% | 39.4% | 56.3% |

| Childless * | 71.1% | 62.0% | 74.4% |

| Urban * | 71.7% | 60.3% | 78.8% |

| Rural * | 43.2% | 26.7% | 39.9% |

| Internet | Mobile Phone | Social Media | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.786 *** | 2.616 *** | 3.019 *** |

| (0.434) | (0.433) | (0.426) | |

| Gender | 0.656 * | 0.642 * | 0.679 ** |

| (0.257) | (0.257) | (0.256) | |

| Age: 30–49 | 0.724 * | 0.741 * | 0.675 * |

| (0.352) | (0.352) | (0.351) | |

| Age: 50–91 | 0.395 | 0.401 | 0.297 |

| (0.411) | (0.410) | (0.410) | |

| Education | 0.051 | 0.047 | 0.057 |

| (0.283) | (0.282) | (0.281) | |

| Lower Middle Class | 0.307 | 0.318 | 0.281 |

| (0.303) | (0.302) | (0.301) | |

| Working Class | 0.441 | 0.455 | 0.420 |

| (0.325) | (0.324) | (0.323) | |

| Divorced | 0.593 | 0.559 | 0.665 * |

| (0.444) | (0.442) | (0.440) | |

| Single | −0.159 | −0.088 | −0.258 |

| (0.407) | (0.407) | (0.405) | |

| Childless | 0.324 | 0.234 | 0.474 |

| (0.434) | (0.434) | (0.432) | |

| Urban | 0.541 * | 0.400 | 0.710 * |

| (0.275) | (0.286) | (0.275) | |

| Frequent Internet User | −0.013 | ||

| (0.269) | |||

| Frequent Smartphone User | 0.385 | ||

| (0.282) | |||

| Frequent Social Media User | −0.668 * | ||

| (0.268) | |||

| R2 | 0.039 | 0.042 | 0.049 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.020 | 0.023 | 0.031 |

| Num. obs. | 578 | 578 | 578 |

| Internet | Mobile Phone | Social Media | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.002 *** | 2.072 *** | 2.312 *** |

| (0.335) | (0.335) | (0.431) | |

| Gender | −0.019 | −0.037 | −0.023 |

| (0.199) | (0.199) | (0.200) | |

| Age: 30–49 | 0.546 * | 0.537 * | 0.494 |

| (0.271) | (0.271) | (0.272) | |

| Age: 50–91 | 0.624 * | 0.612 | 0.573 |

| (0.316) | (0.316) | (0.319) | |

| Education | 0.179 | 0.205 | 0.215 |

| (0.217) | (0.217) | (0.218) | |

| Lower Middle Class | 0.068 | 0.045 | 0.020 |

| (0.237) | (0.237) | (0.238) | |

| Working Class | 0.293 | 0.294 | 0.278 |

| (0.249) | (0.250) | (0.250) | |

| Divorced | −0.617 | −0.566 | −0.511 |

| (0.344) | (0.343) | (0.344) | |

| Single | −0.048 | −0.052 | −0.150 |

| (0.312) | (0.314) | (0.313) | |

| Childless | −0.083 | −0.075 | 0.058 |

| (0.334) | (0.336) | (0.337) | |

| Urban | −0.079 | −0.079 | 0.101 |

| (0.213) | (0.219) | (0.214) | |

| Frequent Internet User | 0.470 * | ||

| (0.211) | |||

| Frequent Smartphone User | 0.351 | ||

| (0.217) | |||

| Frequent Social Media User | −0.216 | ||

| (0.212) | |||

| R2 | 0.027 | 0.023 | 0.020 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| Num. obs. | 569 | 569 | 569 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dall’Agnola, J.; Thibault, H. Online Temptations: Divorce and Extramarital Affairs in Kazakhstan. Religions 2021, 12, 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080654

Dall’Agnola J, Thibault H. Online Temptations: Divorce and Extramarital Affairs in Kazakhstan. Religions. 2021; 12(8):654. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080654

Chicago/Turabian StyleDall’Agnola, Jasmin, and Hélène Thibault. 2021. "Online Temptations: Divorce and Extramarital Affairs in Kazakhstan" Religions 12, no. 8: 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080654

APA StyleDall’Agnola, J., & Thibault, H. (2021). Online Temptations: Divorce and Extramarital Affairs in Kazakhstan. Religions, 12(8), 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080654