From Tamil Pāṇar to the Bāṇas: Sanskritization and Sovereignty in South India

Abstract

:1. Origin of the Bāṇas

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Bards in Early Tamil Society

During the day, may the bards crowd around the festive

sessions of your court and their dark heads and tangled hair

turn radiant with fragrant garlands of gold, beautifully

crafted of thin plaques fashioned in the shape of lotuses

tempered in the fire and threaded onto fine pounded wires!

the Pāṇaṉ who gets an elephant whenever Cēḻiyaṉ,

who has learnt faultlessly the art of war, and whose

army with shining swords kills in the battlefields

kai vār narampiṉ pāṇarkku ōkkiya

nirampā iyaviṉ karampaic cīṟūr

the villages on poor land with narrow paths,

which were granted to the bards who pluck the strings with their fingers

kuṟum poṟai nal nāṭu kōṭiyarkku īnta

kārik kutirai kāriyoṭu malainta

ōrik kutirai ōri…

The bards were so prominent and numerous members of early society and were so identified with panegyrics, that in subsequent development when poets compose panegyrics in praise of kings and chiefs they do so in a ‘bardic convention’, as if a bard were praising the hero of the poem.

While in the Indo-Aryan tradition the purohit (Brahmin priest) accompanies the king (rāja, nṛpa-, bhūpa-, bhūpāla goptṛ-, nātha-,) on his chariot to the battlefield, his Tamil colleague the porunar and/or pāṇar (two types of bards) fulfill a similar function in the king’s (kō, iṟai, iṟaivaṉ) following. Although the Brahmin (antaṇar) is known at the Tamil court, and respected, he does not play any role of significance to be compared with the bards.

The Tamil situation may be considered the reverse of the Indo-Aryan. The Indo-Aryan king is steeped in Vedic and post-Vedic symbolism and ritualism due to which the Brahmins are of primary importance and far more indispensable than the panegyrists, genealogists and eulogists (māgadhas, sūtas). In contrast to the mythological equation of worldly power and (Vedic) cosmic power, the Tamil king lived for the immortality of glory (pukaḻ) of his forefathers, his clan and his own person. In this milieu of glorious death on the battlefield, worship of hero-stones, gruesome celebrations of Victory on the battlefield and of the conception of the ‘world of heroes’, the Tamil king was far more dependent on his bards who had the power to ‘actualize’ glory and thus to confer immortality. Their mutual tie was one of kaṭaṉ ‘sacred duty’ which a king gladly fulfilled for his own sake as well as that of his forefathers and the entire clan. Cosmic equation by Vedic sacrifice was not on his mind; it was performed in course of time perhaps as a fashionable ‘showing off’ to his enemies.

vēṟu pulam muṉṉiya viraku aṟi poruna(Porunarāṟṟuppaṭai 3)

O Porunaṉ knowing the appropriate conduct, who has sought different lands!

pāṭal paṟṟiya payaṉ uṭai eḻāal

kōṭiyar talaiva(Porunarāṟṟuppaṭai 56–57)

O leader of the Kōṭiyar, who has the lute, which provides musical enjoyment associated with songs!

eḻumati vāḻi ēḻiṉ kiḻava(Porunarāṟṟuppaṭai 63)

O owner of seven notes! Get up. May you prosper.

peṭai mayil uruviṉ perum taku pāṭiṉi(Porunarāṟṟuppaṭai 47)

the Pāṭiṉi, who is of excellent qualities and looks beautiful like a peahen!

And even among the four classes with difference known, if a person from a lower class becomes learned, even a person from a higher class will submit to him to study.

What Neṭuñceḻiyaṉ refers to is the caturvarṇa (four classes) which was prevalent among the Indo-Aryan speakers of North India and was absent in the Tamil areas. In fact, according to Manu, the Sanskrit lawgiver, all the Tamils (Drāviḍa) were Kṣatriyas who did not perform the Vedic rituals and, as a result, sank to the rank of Śūdras. In this, they were similar to the Greeks, and Chinese in the eyes of the Brahmins. Neṭuñceḻiyaṉ may have based his statement on a story such as the Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad story of Dṛpta-bālāki of the Gārgya clan and Ajātaśatru, the king of Kāśi. In this story, Dṛpta-bālāki, a Brāhmin, realizes that he lacks the knowledge of Brahman and seeks to become the pupil of Ajātaśatru, a Kṣatriya. (As his name suggests, it is likely Neṭuñceḻiyaṉ has had encounters with the Aryan culture.)

1.3. Tamil Scholars’ Views on the Origin of the Bāṇas

There were also pāṇar who were involved in the field of fighting and excelled in wrestling and protecting the country without learning music and theater. Among them, one called Pāṇaṉ ruled the kingdom north of the river Pālār [Akanāṉūṟu 113, 155, and 325]; Caṅkam poets praise saying ‘in the north is the land of Pāṇaṉ of the strong spear7;’ in that country, stone inscriptions mention Perumpāṇappāṭi8 and Pāṇmalai situated on the northern bank of the Pālār river. His descendants lived as Vāṇar, Vāṇātirāyar, and Vāṇataraiyar. Their many inscriptions are in the Tiruvallam temple in the North Arcot taluk [South Indian Inscriptions, vol. 3, nos. 42, 43, 47 and 48]. In later times, they were spread all over the Tamil country; even those who were called Vāṇakōvaraiyar were also the descendants of the Pāṇaṉ. Another Pāṇaṉ excelled in wrestling and flourished in the Cōḷa court [Akanāṉūṟu 226]; an Akanāṉūṟu poem says that a person called Kaṭṭi from the region ruled by the Gaṅgas [in Southern Karnāṭaka] came to wrestle against Pāṇaṉ in the court of Veḷiyaṉ Tittaṉ and fled in fear as soon as he heard the sound of the kiṇai drum in the court preparing for battle [Akanāṉūṟu 226]; one Porunaṉ from the Āriya country to the north of Kuṭanāṭu, came with one Kaṇaiyaṉ of Kuṭṭanāṭu to wrestle against Paṇaṉ, but, being unable to withstand the strength of Pāṇaṉ, lost making Kaṇaiyaṉ shameful [Akanāṉūṟu 386].9

1.4. Bards and Warriors

The [Caṅkam] anthologies seem also to show a society divided into two different parts: on the one hand, there are the uyarntōr, or “high ones”, spoken of in the Tolkāppiyam, who are warriors and leaders of society and whose death is often commemorated by memorial stones; on the other hand, there are the iḻintōr, or “low ones”, represented by the kiṇai and tuṭi drummers, the Pāṇaṉ, the Vēlaṉ, washermen, leather workers, and others.

- Catti Ārūr of Kṣatriyasikhāmaṇit Terinta Valaṅkai Vēḷaikkāṟar

- Catti Poṉṉaṉ of the Śatrubhujaṃkat Terinta Valaṅkai Vēḷaikkāṟar

- Maṅkalavaṉ Maṇi of Mūrttavikramābharaṇat Terinta Valaṅkai Vēḷaikkāṟar

- Taṇṭaṉ Kampaṉ of Mūrttavikramābharaṇat Terinta Valaṅkai Vēḷaikkāṟar

- Ārūr Tēvaṉ of Mūrttavikramābharaṇat Terinta Valaṅkai Vēḷaikkāṟar

1.5. Bards as Chiefs

Viḻavu ayarntaṉṉa koḻum pal titti15

eḻāap pāṇaṉ nal nāṭṭu umpar

beyond the good land of the bard who does not rise

from many rich snacks as if engaged in a feast

beyond the good land of Pāṇaṉ, who does not make music,

with many rich meat foods as if engaged in a feast

…alarē

vil keḻu tāṉai vicciyar perumakaṉ

vēntaroṭu poruta ñāṉṟaip pāṇar

puli nōkku uṟaḻ nilai kaṇṭa

kali keḻu kuṟumpūr ārppiṉum peritē(Kuṟuntokai 328.4–8)

The gossip was louder than the roar of the noisy village in the arid tract, that saw the stance of the Pāṇar that resembled the look of the tiger, when the chief of Vicciyar of army abounding in archers fought against the kings.18

- The bard’s musical instruments;

- The bard’s performance/music/song;

- The bard’s poverty;

- The bard’s hunger;

- Gifts received by the bard such as food, clothes, elephants, gold flower, and land;

- The bard’s maṇtai, a vessel, in which they received food;

- The bard’s patron;

- The bard’s large entourage of relatives.

māri ampiṉ maḻait tōl cōḻar

vil īṇṭu kuṟumpiṉ vallattup puṟamiḷai

āriyar paṭaiyiṉ uṭaika…(Akanāṉūṟu 336.20–22)

‘Like the army of the Aryan kings at the external protective forest of Vallam strengthened by the bows of the army of the Cōḻas with rain-like arrows, clouds- like shields’

1.6. Is ‘Pāṇaṉ’ (The Name of the Chief) from ‘Pāṇaṉ’ or ‘Bāṇa’?

“The territorial division viz., Pāṇāḍu, is in all probability, the same as Bāṇāḍu i.e., the nāḍu of the Bāṇas. (emphasis mine) The Bāṇas were an ancient line of kings, who also ruled a portion of the Tamil country. This is the earliest so far known inscription, which mentions their territorial division as Pāṇāḍu. The names Vāṇagōppādi-nāḍu and Perumbāṇappādi, etc., are employed in the Tamil inscriptions of the latter period to indicate the territory of the Bāṇas. This territory probably formed the southern portions of the modern North Arcot District and probably also a portion adjacent to it in the South Arcot District. The village Mēlvaṇṇakkambāḍi, possibly the corrupt form of Mēlvāṇagōppāḍi, may have been the western boundary of Vāṇagōppāḍi, and the village Kīḻvaṇṇakkambāḍi near Dēvikāpuram may have been the eastern boundary of the same division. The provenance of our inscription viz., Paṟaiyanpaṭṭu was well within the Bāṇa territory.”

Cf. LT palvayiṉ payanirai cernta pāṇāṭṭu āṅkaṇ. ‘there in Pāṇāṭu where at many places milch cows gather’ (Aka. 155:6–7). pāṇāṭṭu is taken to be the sandhi of pāṇ + naṭṭu and also interpreted as ‘in the country of the pāṇaṉ, by R. Raghavaiyangar (1933)21 and by N. M. Venkataswamy Nattar and R. Venkatachalam Pillai (1949) in their editions of Akanāṉūṟu, even though some old manuscripts give the variant reading pāḻ nāṭṭu (> pāṇāttu) ‘the ruined country’ which does not suit the context. (I am grateful to Dr. S. Palaniappan, Dallas, USA, for the references. I consulted the unpublished notes of U. Ve. Swaminathaiyar at the Swaminathaiyar Library. While noting the reading pāḻ nāṭṭu in Aka. 155, he has given cross-references to verses 113 and 325 referring to pāṇaṉ nal nāttu ‘in the good country of the pāṇaṉ’.) The present early inscriptional reference to pāṇāṭṭu is a valuable confirmation of the correct reading and interpretation of the expression.22

…the manuscript of a Digambara Jain work in Sanskrit, named Lōkavibhāga, has been discovered by the Mysore Archaeological Department (see the reports for 1909 and 1910), treating of Jaina cosmography. The contents, it says, were first delivered by the Arhat Vardhamāna, and handed down through Sudharma and a succession of other teachers. The Rishi Siṃha-sūri (or Siṃha-sūra) produced the work in a translation (? From Prākrit into Sanskrit). And the Muni Sarvanandin formerly (purā) made a copy of it in the village named Pāṭalika in the Pāṇa-rāshṭra. The interesting point is that the precise date is given when this task was completed, namely the 22nd year of Siṃhavarman, the Lord of Kāñchī, and is 80 beyond 300 of the Śaka years…Pāṭalika, the village in which Sarvanandin made his copy, may be Pāṭalīpura, in the South Arcot District. The Periya-purāṇam makes it the seat of a large Jaina monastery in the 7th century. Pāṇarāṣhṭra is no doubt the territory of the Bāṇa kings.

1.7. Perumpāṇ versus Bṛhadbāṇa

References to the Bāṇas are made in inscriptions dating from very early times. The earliest mention is in the Talaguṇḍa inscription of the Kadamba king Kakusthavarman (430–450 A.D.) in which it is said that Mayūraśarman, the first Kadamba king (345–370 A.D.) was helped by an ally of his called “Bṛhad Bāṇa” in his fight with the Pallavas in the forests of Sri Parvata and that he levied tribute from this “Bṛhad Bāṇa” as well as from other kings25. It would appear that the territory of this “Bṛhad Bāṇa” was very near Śrī Parvata, i.e., the present Śrīsailam in the Kurnool District…

The term “Bṛhad Bāṇa” in the Talaguṇḍa inscription corresponds to the Tamil term Peruṃ-Bāṇa of the territorial term Peruṃ-bāṇappāḍi. It was by the latter term that the Bāṇa dominions were denoted…

According to tradition the Bāṇa capital was known as Paṟivipuri, whose other forms were Prapurī, Paṟvipura, Paṟivai, Paṟvai, Paṟvi, Paṟivaipura, Paṟivipurī and Parigipura. Indeed, the last term, Parigipura, has led the late Rai Bahadur Venkayya to identify it with Parigi in the Hindupur Taluk of the Anantapur District. The claim of Tiruvallam in the North Arcot District for the Bāṇa capital, inasmuch as it was also known by the appellation Vāṇapuram, is easily explained by him as merely meaning that Tiruvallam was one of the important towns, if not the capital, of the Bāṇa territory. Long after the Bāṇas had ceased to rule, their scion, wherever they were, claimed to be lords of Paṟivipura and of Nandagiri, another equally important place. Nandagiri is the present Nandi-drug in the Chikballapur Taluk, Kolar District, Mysore. The fact that most of the inscriptions of the Bāṇas have been found in the Arcot, Kolar, Anantapur, and Kurnool districts makes one believe that the term Perumbāṇappāḍi which denoted the Bāṇa territory was applied to the large tract of territory with Śrīsailam in the north, Kolar and Puṅganūr in the west, Kālahasti in the east and the river Pālār in the south. In the north they appear to have been the governors of the Pallava territory till the latter were driven down by the western Cāḷukyas in the latter part of the 6th century A. D…

…The rise of the western Cāḷukya power in the 7th century acted as a check not only to the Pallava power in the Telugu country but also to that of the local Bāṇas who appear to have guarded the Pallava territories there. Consequently, the Bāṇas, as Venkayya supposes, were forced into the northern portion of the North Arcot district …

1.8. Dates of Tamil Texts with the Occurrence of Chief ‘Pāṇaṉ’ or Perumpāṇ

tamiḻ keḻu mūvar kākkum

moḻi peyar tēetta paṉ malai iṟantē

crossing the many mountains of the land, where the language changes, which the three kings with Tamil nature (Cēra, Cōḻa, and Pāṇṭiya) protect27

potumai cuṭṭiya mūvar ulakamum

potumai iṉṟi āṇṭiciṉōrkkum(Puṟanāṉūṟu 357.2–3)

even for those who ruled without sharing

the land to be shared in common by the three (kings)

…vaḻuti

taṇ tamiḻ potu eṉap poṟāaṉ…(Puṟanāṉūṟu 51.4–5)

…The Pāṇtiyan king Vaḻuti

will not tolerate the statement that the cool Tamil land is common (to Cēra, Cōḻa, and Pāṇṭiya kings)

1.9. Pāṇar Dynastic Movement

After an invocation to Śiva, the record introduces us to a king Nandivarman of the Kāśyapa-gōtra. He was born in the family of Karikāla who was “the (celestial) tree mandāra on the mountain Mandara—the race of the Sun, the doer of many eminent deeds such as stopping the overflow over its banks of the (waters of the) daughter of Kavēra (i.e., the river Kāvēri), who made his own the dignity of the three kings (of the South)…”32

It would be of interest to trace here the activities of the Bāṇas during the period prior to their subjugation by the Telugu Chōḻa Vijayāditya of the present record. Several inscriptions of Chāḷukya Vijayāditya found in the locality around the place where the present record has been discovered, mention a number of Bāṇa chiefs ruling over this region…The Perbāṇa family to which some of these Bāṇas of the Ceded Districts are stated to belong, may have, as their family name indicates, belonged to the Bṛihad-Bāṇa line, the foes of Kadamba Mayūraśarman, mentioned in the Talaguṇḍa inscription of Kākusthavarman.

1.10. Linguistic Variation from Pāṇar to Bāṇa

A new service was started in the temple of Thiruvidaimarudūr creating an enactment for singing the Thirup-padiayams [sic] and also arranging for the dancing girls of the temple to sing in the 9th year of Vikramachola, the son of Kulottunga II. The service was called “Bānap-peru” (Bānap-pani). This was a royal appointment issued by Vikkramachola [sic] and a certain Irumudi Cholan alias Acancala Peraraiayan [sic] was appointed to do the service...The record states that he was to sing in the presence of God of the Thiruvidaimarudūr temple and direct other Bānas for arranging the Dancing girls to sing (Thiruvidai marudur—udaiyārukku—pādavum, ikkoyil Taliyilārai pāduvikkavum ikkoyil Devaradiyārai pāduvikkavum Bānapperāka). The Bānas were great singers from the Sangam age and we find the Bānas, Yālpāna was a close friend of Jnāna-sambandar and again we find the Bānas were appointed in the Great temple of Thanjavaur [sic]. According to this inscription the service should be added to the temple service and the Bāna should be paid one kalam of paddy per day to the Perariayan [sic] for singing. He should be allotted one residence as Bānak-kudiyiruppu as before…It is interesting to note that the singing service is called Bānapperu.

teṉpula maruṅkiṉ viṇṭu niṟaiya

vāṇaṉ vaitta viḻuniti peṟiṉum(Maturaik Kāñci 202–03)

even if (you) obtain the excellent wealth, which Bāṇa, the Asura, stored so that it filled the mountains in the southern region

vāṇaṉ pērūr maṟukiṭai naṭantu

nīḷ nilam aḷantōṉ āṭiya kuṭamum(Cilappatikāram 6.54–55)

the pot dance performed by the one who measured the vast world

having walked along the street of the city of Bāṇa

vāṇaṉ pērūr maṟukiṭait tōṉṟi

nīḷ nilam aḷantōṉ makaṉ muṉ āṭiya

pēṭik kōlattup pēṭu…(Maṇimēkalai 3.123–25)

the transgender dance, which the son of the one who measured the vast world

having appeared on the street of the city of Bāṇa as a transgender person and danced

ulaikku uriya paṇṭam uvantu irakkac ceṉṟāl

kolaikku uriya vēḻam koṭuttāṉ—kalaikku uriya

vāṇar kōṉ āṟai makatēcaṉukku intap

pāṇaṉōṭu eṉṉa pakai

When I went to solicit provisions meant for cooking

he gave a male elephant meant for killing.

For Makatēcaṉ of Āṟakaḻūr, the chief of the Bāṇas, renowned for art,

what is the enmity towards this Pāṇaṉ, the bard?

1.11. Summary of the Arguments for the Origin of the Bāṇas from the Tamil Pāṇar

1.11.1. The Bards Were Also Warriors

1.11.2. A Section of Pāṇar Being Rulers

1.11.3. Bāṇas Originating from Tamil Pāṇar

2. Sanskritization and Sovereignty of the Pāṇar/Bāṇas

2.1. Tamil Idea of Kingship

Rice is not the life of the world nor is water the life!

The king is the life of this world with its wide expanses!

And so it is incumbent upon a king who maintains an army

wielding many spears to know of himself: “I am this world’s life!”

2.2. Sanskritization

2.3. Bali Mythology in Bāna Inscriptions

The expression sakala-jagat-tray-ābhivandita-sur-āsur-ādhīśa-Parameśvara-pratihārī-kṛta-Mahābali-kulodbhava is translated by Mr. [Lewis] Rice, on the strength of some Kanarese tradition, “born of the family of Mahābali, who had made Paramēśvara, lord of gods and demons worshipped in all the three worlds, (his) door-keeper;” Ep. Car. Vol. X. p. ii, Note 5.

(Verse 1.) May that Śiva promote your well-being, whose true nature even the Vēda cannot fully reveal, from whom the creation, the preservation, and the destruction of all the worlds proceed, on whom the devotees meditate, (and) whose two feet are tinged with the collections of red rays of the rows of jewels in the diadems of the crowds of the chiefs of the gods who in person bow down before him!

(V. 2) May that Nārāyaṇa, whose body ever rests on the lord of serpents, (and) whose two feet are worshipped by crowds of gods, guard you! He, whom the gods and Asuras, desirous of churning the matchless sea of milk, discarding the Mandara laid hold of, as it were, to obtain a second time the nectar of immortality, (and) who then shone, even more than ordinarily, as if he were the Añjana mountain!

(V. 3.) There was the regent of the Asuras, named Bali, whose sole delight it was to engage in acts of violence towards the gods, while his one vow was, to worship the two feet of Śiva. He, after having presented as an excellent sacrifice a respectful offering to the primeval god, the enemy of the Daityas, with great joy (also) gave to him who bore the form of a dwarf the earth with its islands and with all things movable and immovable.

(V. 4.) From him sprang a mighty son, a treasure-house of good qualities, towards whom was ever increasing the great pure favour of Śambhu on whose head are the lines of the lustre of a portion of the moon, –Bāṇa, the foe of the gods, who with his sword struck down the forces of his enemies.

(V. 5.) As the cool-rayed moon rose from the sea of milk, so was born in his lineage Bāṇādhirāja, who, possessed of never-failing might, with his sharp sword cut up his enemies in battle.

(V. 6.) When Bāṇādhirāja and many other Bāṇa princes had passed away, there was born in this (lineage), not the least (of its members), Jayanandivarman, the fortune of victory incarnate, and an abode of fortune.

(V.7.) This unique hero of great might ruled the land to the west of the Andhra country, like a bride sprung from a noble family unshared by others, having his feet tinged by the crest-jewels of princes.

…

(V.15.) To him was born a son Vijayabāhu, named Vikramāditya a unique light of the Bāna family, who has followed the path of prudent conduct, before whom the assemblage of opponents has bowed down, (and) who has Kṛishṇarāja for his friend. Eminently prosperous (he is, and) free from evil and distress.

(Line 45.) This (prince), the dust of whose feet is tinged with the lustre of the jewels on the edges of the diadems of all princes without exception, and whose two arms are filled with ample fame, gained in victories over the multitude of arms of the adherents of many different hostile princes, after pouring out a stream of water from the beautiful golden jar, held by the palms of his hands the bracelets on which are thickly covered with various bright jewels,—(has given) to the excellent twice-born, dwelling at Udayēndumaṅgala, who delight in, what is their proper duty, the knowledge of the truth of all the Vēdas and Vēḍāṅgas and philosophy, (and) are eager to impart the knowledge of things which is stored up in their minds, …

The great Asura Bali, the powerful son of Virocana, will arise and cause Indra to fall from his kingdom. When the triple world has been stolen by him despite the opposition of the husband of Śacī, I will take birth as the twelfth son of Aditi and Kaśyapa. Then I shall restore the kingdom to Indra, of infinite glory. I shall return the Devas to their positions, O Nārada, and Bali I shall cause to dwell in the region of Pātāla.

We can see Bali bearing different kinds of relationships to Indian attempts to conceptualize what is significant, valuable and real. In the earlier phases of the Epic-Purānic [sic] texts, Bali represents forces inimical to a central idealized reality of the universe., that of dharma (virtue, righteousness, and order). Thus Viṣṇu, often seen as upholding dharma, is portrayed in his Dwarf avaṭāra as overcoming this disorderly and disturbing force.

But gradually, the focus shifts, and in the period of the middle and later Purāṇas the total corpus of Bali presents something of a debate or tension between different foci of significance—dharma, bhakti, and prosperity. In Bali there is an exploration of the relation between these features, of which the total effect is to suggest that although Bali may be good, and a great devotee, that does not necessarily mean that his kingly role is legitimate. The fact that his kingdom is eminently prosperous may even be seen as problematic. But from another viewpoint within the same arena of debate, Bali can be shown as the true devotee who has learned not to be attached to anything. Bali lost his kingdom but found his Lord.

2.4. Why Choose Bali as the Progenitor of the Dynasty?

Koṭukoṭṭi—dance of Śiva clapping his hands at the time he burnt down the triple cities

Pāṇṭaraṅkam—dance by (Śiva in the form of) Bhāratī who applied ash all over the body at the time he destroyed the triple cities

Alliyam—dance by Krṣṇa when he broke the tusk and killed the elephant sent by Kaṃsa to kill Kṛṣṇa

Mal—dance by Viṣṇu when he defeated the demon (Bāṇāsura) in wrestling51

Tuṭi—dance by Murukaṉ with the tuṭi drum when he killed the demon standing as a Mango tree in the sea

Kuṭai—dance by Murukaṉ with an umbrella/parasol when he defeated the demons

Kuṭam—dance by Kṛṣṇa with pots on the streets of the city of Bāṇa (Bāṇāsura) when Bāṇa had imprisoned Aniruddha, the grandson of Kṛṣṇa

Pēṭu—dance by Kāma, who took the form of a transgender person (in Bāṇāsura’s city)

Marakkāl—dance by Durgā when she wore wooden legs to defeat the demons

Pāvai—dance by Lakṣmī in the form of beautiful Kollippāvai at the time she defeated the demons

Kaṭaiyam—dance by Indrāṇi at the northern gate in the city (of Bāṇāsura)

It is generally accepted that the Cilappatikāram existed long before it was put down in writing. Scholars are of the opinion that the epic, with the rest of early Tamil literature, must have had a long oral existence before it acquired its present form. For generations, bards (pāṇaṉs) have recited or sung the story of Kōvalaṉ throughout the Tamil country, embellishing it with myths. It was this story from the oral tradition that was at some point transcribed by a learned poet (pulavaṉ). Thereafter, both the oral and written versions freely circulated, each drawing upon the other. One such written version that has come down to us from the distant past is attributed by tradition to Iḷaṅkō Aṭikaḷ, a prince of the Cēral royal family and Jaina monk.

2.5. Pāṇ Kaṭaṉ of the Bardic Culture

maram toṟum piṇitta kaḷiṟṟiṉir āyiṉum

pulam toṟum piṇitta tēriṉir āyiṉum

tāḷil koḷḷalir vāḷil tāralaṉ

yāṉ aṟikuvaṉ atu koḷḷum āṟē

cukir puri narampiṉ cīṟiyāḻ paṇṇi

viraiyoli kūntal num viṟaliyar piṉ vara

āṭiṉir pāṭinir celiṉē

nāṭum kuṉṟum oruṅku īyummē(Puṟanāṉūṟu 109.11–18)

Though you have tied your elephants to every tree there,

though your chariots are spread all over the fields,

you will not defeat him through your efforts!

He will not give in to your swords.

But I do know how you can obtain his possessions!

If you, [as Pāṇar,] would only play on a small lute with its polished twisted strings

while your [queens follow you as] Viṟalis with their rich fragrant hair,

and you come dancing and singing,

he will give as gift his country as well as his hill.

… the word kaṭaṉ is used in the particular sense of duty or responsibility. It is in this sense that a responsibility for the bards is prescribed for the kings. It may not have been as rigid as legal enactments. But the conduct of the heroic society was itself bound by a code of honour and the obligation to adhere to it was almost absolute…

3. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | From the Mahābhārata to the Bhāgavatapurāṇa, the story of Bali varies in its details. Bali, an Asura, had defeated the Devas and Indra and ruled the triple world as a king. When the Devas pleaded with Viṣṇu to intervene, Viṣṇu incarnated as Vāmana, a dwarf Brahmin. He went to Bali who was performing a sacrifice. At the sacrifice when Bali asked Vāmana what gift he wanted, Vamana requested that he be given land that could be measured in three steps. Bali agreed to the request. Immediately Vāmana grew into the giant cosmic form of Trivikrama and covered the triple world in two steps. There was no place for him to place his foot for the third step. Then, Bali asked Viṣṇu-Vāmana to put his foot on Bali’s own head. Viṣṇu-Vāmana put his third step on Bali’s head and sent him to Pātāla, the netherworld. Viṣṇu-Vāmana restored Indra as the king of the Devas. For more details of the Bali story, see Hospital (1984). |

| 2 | Poruna, Kōṭiyar Talaiva, and Ēḻiṉ Kiḻava are the vocative forms of Porunaṉ, Kōṭiyar Talaivaṉ, and Ēḻiṉ Kiḻavaṉ, respectively. |

| 3 | In a Tanjavur temple inscription (South Indian Inscriptions, vol. 2, vol. 2, no. 66, p. 274), Maṟaikkāṭṭuk Kaṇavatiyāṉa Tiruveḷḷaṟaiccākkai was given a grant to sing for dance programs. His name can be translated as ‘Maṟaikkāṭṭu Ganapati, who is the Cākkai Theater performer from the village of Tiruveḷḷaṟai.’ Evidently, he was a performer of Cākkaikkūttu, a dramatic art as well as a singer. The same inscription has two Pāṇar grantees with the title Cākkai. |

| 4 | See (Arunachalam 1977, pp. 27, 49; Hart and Heifetz 1999, p. 322). However, Zvelebil (1992, p. 29) considered the bards to be part of the elite strata of the Tamil society. |

| 5 | Using data from Tamil philology, epigraphy, Jainism, and Dravidian linguistics, Palaniappan (2008) showed there was no notion of untouchability during the Classical Tamil period. Using Tamil philology as well as epigraphy, Palaniappan (2016) showed that notwithstanding their portrayal as a low caste in hagiographic works, in real life, the Tamil Pāṇar enjoyed high status, performed in Sanskrit theater, sang in front of the deities in Brahmanic temples, and trained temple women to sing until the advent of the Vijayanagar rule in the Tamil country. Even during and after the Vijayanagara rule, the Tamil Pāṇar never became untouchables. Palaniappan (2016, p. 307) also noted, “Ludden (1996, p. 123) has presented demographic data from 1823 from the Tirunelvēli area that showed that the Pāṇar were one of several castes that formed the large non-untouchable Śūdra category. Additionally, Thurston (1909, p. 29) has presented ethnographic information, according to which the Pāṇar employed Brahmins and Veḷḷālas as priests and could enter temples”. |

| 6 | Unless otherwise stated, translations in this essay are mine. |

| 7 | Akanāṉūṟu Maṇimiṭai Pavaḷam 226. |

| 8 | Perumpāṇappāṭi is mentioned in South Indian Inscriptions, vol. 3, no. 52, p. 112 as ‘jayaṅkoṇṭacoḻamaṇṭalattu tiyākāparaṇavaḷanāṭṭu perumpāṇappāṭi karaivaḻi brāhmadeyam tiruvallattu tiruvallamuṭaiyārkoyil’ This can be translated as ‘the temple of Tiruvallamuṭaiyār in the Brāhmadeyam of Tiruvallam along the riverbank in Perumpāṇappāṭi of Tiyākāparaṇavaḷanāṭu of Jayaṅkoṇṭacōḻamaṇṭalam’. |

| 9 | For consulting Akanāṉūṟu 113, 226, 155, 325, and 386, see the 1933 edition by Rākavaiyaṅkār and Irājakōpālāryaṉ as well as the edition by Nāṭṭar and Pīḷḷai. However, two corrections need to be made. In Akanāṉūṟu 113, my interpretation of eḻāap pāṇaṉ is ‘non-music making Pāṇaṉ’ instead of ‘Pāṇaṉ…who never shows his back in battle.’ In Akanāṉūṟu 226, as Turaicāmip Piḷḷai states Kaṭṭi came to fight against Pāṇaṉ, who was in the Cōḻa court. Pāṇaṉ did not accompany Kaṭṭi. |

| 10 | This occurs in the inscription as “pakkavādyar aḻakiyacōḻatterintavalaṅkaivēḷaikkāṟaril aiyāṟaṉ antari … I have differentiated between long ē/ō from short e/o while the inscription does not do so. The square brackets indicating indistinct letters as shown in the South Indian Inscriptions, vol. 2, no. 66 are not shown here for the sake of readability. |

| 11 | DEDR 77 aṭu means ‘kill, destroy, conquer’. In fact, there is a specific grammatical term called Veḷippaṭai to refer to such usages where the intended meaning is made explicit. |

| 12 | Cōmacuntaraṉār, the modern editor, following the fourteenth-century commentator Nacciṉārkkiṉiyar, explains it as ‘Porunar bards with taṭāri drums who have arms like concert drums and who have the nature of opposition/disagreement due to education.’ Cāminātaiyar in his Pattuppāṭṭu edition explains, “Having arms like concert drums’ refers to their ability to oppose with physical strength rather than education.” My translation above is based on possible meanings related to physical strength. In fact, according to the Tamil Lexicon, the possible meanings of muraṇ are 1. Variance, opposition; perversity; 2. Spite, hatred; 3. Fight, battle; 4. A mode of versification in which there is antithesis of words or ideas; 5. Strength; 6. Greatness; 7. Roughness; stubbornness; 8. Fierceness; 9. A flaw in rubies. It should be noted that tōḷ is often interpreted as ‘shoulder’ (Hart 2015, p. 387). It really means ‘arm’ as is clear from Kalittokai 109.13–15. The gift of flowers made of gold is a certain indication that the recipients were bards as in Puṟanāṉūṟu 29.1–5 we saw earlier. |

| 13 | Many scholars interpret Pāṇaṉ as an ally of Kaṭṭi who fled without fighting in the court of the Cōḻa king. That is not accurate. It was Pāṇaṉ, who was in the court of the Cōḻa king, the intended adversary of Kaṭṭi. Modern scholars like Nāṭṭār and Piḷḷai unnecessarily add a word ‘kūṭi’ meaning ‘having joined’ to “Pāṇaṉoṭu’ to come up with the misinterpreted meaning. The nature of the verb ‘poru’ ‘to fight’ is that it is preceded by the adversary being fought/intended to be fought by the subject of the verb marked with the case marker ‘oṭu’. Perhaps Nāṭṭār and Piḷḷai were influenced by Rā. Rākavaiyaṅkār and Irājakōpālāryaṉ, who interpreted Pāṇaṉ as an ally of Kaṭṭi in their edition. Hart (2015, p. 232) has followed Nāttār’s interpretation. |

| 14 | See the Cōmacuntaraṉār edition of the Akanāṉūṟu. |

| 15 | Wilden has chosen the reading titti ‘snack’. I prefer the reading tiṟṟi ‘meat’ as do earlier editions of the Akanāṉūṟu. Moreover, titti is used nowhere else in the Caṅkam literature in the sense of food and tiṟṟi is related to tiṉ ‘eat’ in Dravidian Etymological Dictionary Second Edition (DEDR hereafter) entry 3263 and titti is not. |

| 16 | vayiriya mākkaḷ paṇ amaittu eḻīi ‘the Vayiriyar bards having set the melody and making music’. |

| 17 | Wilden has not compared the present text pāṇaṉ nal nāṭṭu with the text nal vēl pāṇaṉ nal nāṭṭu in Akanāṉūṟu 325.27 which means ‘in the good land of Pāṇaṉ with the good spear’ where Pāṇaṉ is clearly a warrior and chief as he has a spear and possesses the good land. |

| 18 | In the Caṅkam tradition, the term vēṇtar in the poem could only refer to the kings of the Cēra, Cōḻa, and Pāṇṭiya dynasties. |

| 19 | The proper way to interpret such occurrence is given in the commentary for Aka. 113 in the Akanāṉūṟu Kaḷiṟṟiyāṉai Nirai edited by Vē. Civacuppiramaṇiyaṉ. (In addition to earlier manuscripts, this edition also used a paper manuscript with commentaries for 170 poems discovered in the Tākṭar U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar Nūl Nilaiyam during the publication process for this 1990 publication.) Here is the relevant excerpt from the commentary for Akanāṉūṟu 113.17, which mentions Pāṇaṉ, the chief.

|

| 20 | Akanāṉūṟu 113, and 325 refer to a chief by the name ‘Pāṇaṉ’. Akanāṉūṟu 155 refers to ‘Pāṇāṭu’ the land of Pāṇ, which the commentator of the 1933 edition of Akanāṉūṟu equates to Pāṇāṉ. Each of Akanāṉūṟu 226 and 386 refers to a warrior or wrestler referred to as Pāṇaṉ. |

| 21 | In the transliteration system followed in this essay, the name is Rākavaiyaṅkār. What Mahadevan refers to as Raghavaiyangar (1933) is the same as the 1933 edition of Akanāṉūṟu by Rākavaiyaṅkār and Irājakōpālāryaṉ. |

| 22 | ‘Aka.’ is abbreviation for the Akanāṉūṟu. |

| 23 | This is similar to the land of the Cōḻas mentioned in Akanāṉūṟu 201.12–13 as cōḻar veṇṇel vaippiṉ nal nāṭu ‘the good land of the Cōḻas with areas growing white paddy’ |

| 24 | The Periyapurāṇam (PP) mentions two places, Pāṭaliputtiram, and Tiruppāṭirippuliyūr but never identifies one with the other (1303.1 and 1396.4). In fact, PP does not clearly state where Pāṭaliputtiram is located, either in South Arcot district or elsewhere. Modern scholars like Rā. Pi. Cētuppiḷḷai (aka R. P. Sethu Pillai) have identified Pāṭaliputtiram with Tiruppāṭirippuliyūr near Cuddalore on the Bay of Bengal (Cētuppiḷḷai [1948] 2007, p. 228). This identification is based on the fact that Tamil name ‘Pātiri’ and Sanskrit ‘Pāṭali” refer to the same tree with the botanical name Bignonia suaveolens or Sterospermum chelonoides (the tree bearing the trumpet-flower). Additionally, the god in the temple at Tiruppātirippuliyūr is called Pāṭalīśvarar with the temple tree being Pātiri. However, the Pātiri tree is not confined to one location in Tamil Nadu and there are many villages with the name Pātiri in Tamil Nadu. There is a hilly village called Pātiri (Pin Code 635703) in Tiruvannamalai district approximately 50 km by road to the west of Pōḷūr in Javvadu Hills. We have one Pātiri approximately two km from Vandavasi sharing the same Pin Code 604408. We also have a Mel Pātiri (west Pātiri) in the same Pin Code. We have a village called Pātiri (Pin code 603201) approximately 23 km southeast of Vandavasi. Additionally, there is a village near Acharapakkam in Chengalpattu district called Pātiri too. Like the place names associated with the above locations, a place name Pātiri would offer better possibilities for direct translation into Sanskrit as Pāṭalika (with the addition of suffix ka) than Tiruppātirippuliyūr. Given all these possibilities, we do not have to accept the location near Cuddalore as the ancient location of Pāṭalikā. Consequently, Pāṭalikā could have been located in the region known later as Perumpāṇappāṭi or Vāṇakōppāṭi. One does not have to worry about the Pāṇar dynasty controlling an area as far south as Tiruppātirippuliyūr. |

| 25 | Although Ramachandran cites Epigraphia Indica, vol. 8, p. 30 as his source for the information, the correct page number should have been 35. Here Mayūraśarman is said to have levied taxes on the Great Bāṇa, but there is no mention of the Bāṇa being an ally of Mayūraśarman. |

| 26 | This article follows the University of Madras Tamil Lexicon system of transliteration. However, often epigraphists and historians transcribe Tamil words and do not transliterate according to the University of Madras Tamil Lexicon system. In quoting their work, the text in the source document is not changed. Here, Perumbanar mentioned by Chopra, Ravindran, and Subrahmanian is the same as Perumpāṇar according to our system of transliteration. Additionally, Sanskrit vocalic ṛ in Bṛhadbāṇa has been rendered as ri here. In excerpts quoted from Epigraphia India articles it is rendered as ṛi as given in the publications. Elsewhere, it is rendered as ṛ. |

| 27 | My translation is based on Po. Vē. Cōmacuntaraṉār, a modern commentator, who explains those lines as:

|

| 28 | It should be noted that long after the Tamil confederacy ceased to exist, the Tamil land was denoted by the term trairājya in Sanskrit inscriptions like the Kēndūr Plates of Kīrttivarman II (Epigraphia Indica, vol. 9, pp. 202–5). Pathak (Epigraphia Indica, vol. 9, p. 205) has translated trairājya in South Indian Sanskrit inscriptions and literary texts as “the confederacy of three kings”. Pathak quotes a commentary of the Ādipurāṇa (XXX, 35) which explains trairājya as meaning “Choḷa, Kerala and Pāṇḍya”. The Pārttivacēkarapuram śālā grant of 866 CE specifies that the students of the śālā should be learned in trairājya vyavahāra., i.e., administrative matters of the Cēra, Cōḻa, and Pāṇṭiya kingdoms (The Tamil Varalatru Kazhagam 1967, A-5 and A-15). There were administration officials under the Cōḻas with the title Trairājyaghaṭikā Madhyasthaṉ (South Indian Inscriptions, vol. 30, no. 117, pp. 98–99) in 961 CE. The fact that the royal officials of the Pāṇṭiya, and Cōḻa kingdoms were continued to be given the title mūvēntavēḷāṉ as late as the twelfth century CE (where the prefix mūvēnta- refers to the adjectival form of mūvēntar meaning ‘three Tamil kings’) as in South Indian Inscriptions, vol. 14, no. 233, p. 137, i.e., more than a millennium after the three kingdoms ceased to have any semblance of a confederacy, indicates the vestiges of a tradition that must have been developed during the days of the confederacy. The Vakkaleri Plates of Kīrtivarman II also mention trairājya (Epigraphia Indica, vol. 5, p. 203). The Jejuri grant also mentions trairājya (Epigraphia Indica, vol. 19, p. 64). A discussion of the significance of the term trairājya is presented by Tieken (2001, p. 134). |

| 29 | Jayaswal and Banerji prefer the interpretation of terasa-vasa-satikam as 113 years while some other scholars interpret it as 1300 years. See Epigraphia Indica, vol. 20, p. 88, n. 5. |

| 30 | Sastri (1987, p. 144) says, ‘A long historical night ensues after the close of the Śangam age. We know little of the period of more than three centuries that followed. When the curtain rises again towards the close of the sixth century A.D., we find that a mysterious and ubiquitous enemy of civilization, the evil rulers called Kalabhras (Kaḻappāḷar), have come and upset the established political order which was restored only by their defeat at the hands of the Pāndya and Pallavas as well as the Chālukyas of Bādāmi. Of the Kalabhras, we have as yet no definite knowledge; from some Buddhist books we hear of a certain Accutavikkanta of the Kalabhrakula during whose reign Buddhist monasteries and authors enjoyed much patronage in the Chola country… The Cholas disappeared from the Tamil land almost completely in this debacle, though a branch of them can be traced towards the close of the period in Rayalaseema-the Telugu-Chodas…’ The latest work on Kalabhras is by Gillet (2014), who summarizes the work of many scholars after Sastri, who have tried to trace the origin of the Kalabhras. She is skeptical about the Kalabhras occupying the Pāṇṭiya kingdom. However, she has left out an important work by Kācinātaṉ (1981), who discusses a ca. ninth-century inscription at Poṉṉivāṭi that mentions a ruler of the Koṅku region, kali niruva(pa) kaḷvaṉ āiṉa kōkkaṇṭaṉ iravi ‘King Kaṇṭaṉ Ravi alias Kali king Kaḷvaṉ’. Based on this inscription, he equates the Kalabhras with the lineage of Kaḷvar mentioned in Akanāṉūṟu 61.11 (Kācinātaṉ 1981, p. 14). For more details regarding this inscription, see Epigraphia Indica, vol. 38, pp. 37–39. Additionally, Gillet has not considered Kallāṭam 57.12-13 of the tenth century CE, and Periyapurāṇam 991.2 of the twelfth century, which mention a king from Karnataka ruling over Madurai. These are discussed by Kācinātaṉ (1981, pp. 20–22). |

| 31 | The updated date of seventh century for Mālēpāḍu plates follows Sastri (Epigraphia Indica, vol. 27, p. 251). |

| 32 | The important expression in the plates in this connection is ‘trairājya-sthitim₌ātmasāt-kṛtavataḥ. Even though it comes several centuries after Khāravela, what Mālēpāḍu plates suggest is the possible historical fact of Karikālā becoming the sole overlord of the whole Tamil region at a cost to the confederacy of the three Tamil kingdoms mentioned earlier. Indeed, these plates may offer an independent corroboration of the existence of the confederacy and the possible reason for its defeat by Khāravela. The ‘three kings’ in the quote above is the translation of Sanskrit ‘trairājya’ in the inscription attesting to the earlier state of Tamil confederacy. It should be noted that the Telugu Cōḻa claims descent from the Tamil king Karikāla. As seen earlier, Māmūlaṉār also has mentioned the joint defense of the northern border of the Tamil region by the three Tamil kings in Akanāṉūṟu 31. We know that Karikāla is praised by Māmūlaṉār in Akanāṉūṟu 55 as having won a fierce battle against the Cēra king. Thus, Māmūlaṉār must have witnessed in his lifetime the Tamil confederacy in operation as well as its possible weakening or collapse under Karikāla. This suggests that Khāravela either defeated a weakened Tamil confederacy or the confederacy’s defeat led to an internecine struggle that ultimately led to Karikāla becoming the sole overlord of the Tamil country. |

| 33 | The corrected date of fifth century is noted in the errata. |

| 34 | Kiruṣṇakiri Māvaṭṭak Kalveṭṭukaḷ, p. 29. The name Perumpāṇaviḷavaraicar < perum+pāṇa+v+iḷa+v+araicar, where -v- is due to sandhi and iḷavaraicar indicates a prince. Here, pāṇa functions as an adjective. The name Perumpāṇaraicar < perum+pāṇ+araicar. Here, pāṇ functions as an adjective. |

| 35 | The letters ‘car’ are missing in the inscription but can be inferred. |

| 36 | Epigraphia Indica, vol. 8, p. 28. |

| 37 | Periyapurāṇam 3773.3. Pāṇaṉār is the honorific form of the masculine singular form, Pāṇaṉ. |

| 38 | Periyapurāṇam 2159.3. According to legends associated with the founding of Jaffna or Yāḻppāṇam in northern Srī Lanka, a Yāḻppāṇaṉ meaning ‘a Pāṇaṉ playing a lute’ came from India and performed before the local king, who presented him with some uninhabited land in northern Sri Lanka. After receiving the land, the bard returned to India and encouraged some other bards to go to Sri Lanka and settle in the land the bard had received. Over time, that settlement grew to be known as Yāḻppāṇam. The Tamil Saint Aruṇakirinātar of the fifteenth century CE conflated this bard with Saint Tirunīlakaṇṭa Yāḻppāṇa Nāyaṉār and called Yāḻppaṇam as Yāḻppāṇāyaṉ (Yāḷppāṇ+Nāyaṉ) Pattiṉam (Rasanayagam 1984, pp. 245–49). This legend also supports the tradition of the bards receiving land as gift. |

| 39 | However, it should be noted that Palkuriki Sōmanātha in his Basavapurāṇam mentions a Bāṇa, who is depicted more along the lines of Bāṇāsura than Bāṇabhadra (Rao and Roghair 1990, p. 160). However, Sōmanātha’s work came at least a century later. So, we cannot equate his ideas with whatever the author of the inscription had in 1101 CE. |

| 40 | Handwritten notebook of A. Subramanian, Lecturer in Veena, Banaras Hindu University, containing Harikesanallur L. Muthiah Bhagavatar’s compositions available at Music Research Library, Chennai. 1946. It can be downloaded from http://musicresearchlibrary.net/omeka/items/show/1822 (accessed on 14 November 2021). |

| 41 | Vikramachola was not the king who issued the grant. See South Indian Inscriptions, vol. 5, no. 705. |

| 42 | Although we come across persons with titles beginning with Bāṇa- and Vāṇa- even up to the sixteenth century CE, their real affiliation to the early Bāṇas is suspect. There is a thirteenth-century CE Pāṇṭiya Māṟavarmaṉ Kulacēkara Tēvar inscription in Tiruttuṟaippūṇṭi that mentions a Kaikkōḷar by the name Tiruvāṇṭārāṉa Cīṅkaṇamarāyarāṉa Vāṇarāyar (a Kaikkōḷar named Tiruvāṇṭār alias Ciṅkaṇamārāyar alias Vāṇarāyar) (Tiruttuṟaippūṇṭik Kalveṭṭukaḷ, p. 108). Cīṅkaṇa was the name of a general of the Hoysaḷa king Somēśvara killed before Māṟavarmaṉ Kulacēkara began his reign in 1268 CE (Sastri 1987, pp. 215–16). Kaikkōḷars were part of elite Cōḻa military units. In post-Cōḻa times, they gradually shed their association with military units and emerged as an occupational status group according to Ali (2007, p. 509). Clearly, this Kaikkōlar was not affiliated with the Bāṇa chiefs by descent. He had been given or assumed the title Vāṇarāyar. Because of problems like these, Orr (2018, p. 347) says, “Indeed, we cannot be sure of the actual filiation among the rulers who took up the titles and claims to fame of the Bāṇas in successive times and various places, although a good deal of scholarship has in the past been devoted to aspects of the political history of the Bāṇas and the clan’s relationships with the kings belonging to South India’s major dynasties”. |

| 43 | For details about this story, see (Cane 2019, p. 35). |

| 44 | Ali (2000, pp. 185–89) sees an influence of Rāṣṭrakūṭas from the eighth century in the claims of the Cōḻas of Tanjavur and the Pāṇṭiyas of Madurai to belong to Solar and Lunar descents, respectively, with an objective of claiming paramount overlordship of the world. However, as noted earlier, Puṇyakumāra, a Telugu Cōḻa of the seventh century, claimed to belong to the race of the Sun. |

| 45 | South Indian Inscriptions, vol. 2, parts 3& 4, p. 386. The Mahābhārata’s Śibi belonged to the Lunar lineage. However, the Cōḻas claiming to belong to the Sōlar lineage included Śibi in the Sōlar race, since he was already mentioned in Puṟanāṉūṟu 37, 39, 43, and 46. |

| 46 | |

| 47 | kulotbhava is corrected as kulodbhava in other inscriptions. |

| 48 | While Kielhorn (Epigraphia Indica, vol. 3, pp. 74–79) has called him Vikramāditya II, Ramachandran (1931, p. 309) has corrected it to Vikramāditya III based on updated information up to 1931. |

| 49 | Pāṭāla is netherworld. |

| 50 | Based on Cilappatikāram 6.39–63 and its commentary by Aṭiyārkkunallār. Explanations within parenthesis are based on Aṭiyārkkunallār’s commentary. |

| 51 | That Kṛṣṇa performed this dance after killing Bāṇāsura is Aṭiyārkkunallār’s explanation. The Arumpatavurai, the earlier commentary, does not say anything about this dance. In fact, Iḷaṅkō Aṭikaḷ’s own text allows for the interpretation that Kṛṣṇa performed two dances in the capital of Kaṃsa–one after killing the elephant sent by Kaṃsa and the other after killing a demon. In the Harivaṃśa some seers are supposed to say to Kṛṣṇa that Cānura, the wrestler, was a Dānava or Asura. Moreover, according to the Harivaṃśa, Bāṇāsura is not killed by Kṛṣṇa. Kṛṣṇa only cuts all his arms except two and spares his life due to Śiva’s request. However, it should be noted that none of the dances performed by Kṛṣṇa in Kaṃsa’s and Bāṇa’s cities are mentioned in the Sanskrit texts. So, Aṭiyārkkunallār might have been mistaken about the locale of the Mal dance or he could be drawing on a different narrative tradition. |

| 52 | Piḷḷai and Poṉipās (1966, pp. 16–18). Although not explicitly stated in the Puṟanāṉūṟu, according to Tamil tradition, the three Tamil kings did not defeat Pāri in battle. They killed him by treachery. In his commentary on Puṟanāṉūṟu 108, Auvai Turaicāmi Piḷḷai says that the Tamil kings realized that waging war against Pāri and defeating him was difficult. So, they disguised themselves as suppliants and solicited Pāri as a gift. Following the righteous conduct of alleviating the poverty of solicitors, Pāri went with them and was killed by them. Additionally, in his commentary on Puṟanāṉūṟu 110, Auvai Turaicāmip Piḷḷai says, “Kapilar kūṟiyatu pōlavō, atu pōlvatoru cūḻcciyiṉaiyō avarkaḷ ceytu Pāriyaik koṉṟaṉar eṉpa” meaning ‘They say that they [the three kings] did either as Kapilar said or engaged in a similar treachery and killed Pāri.’ Piḷḷai and Ponipas say that the three kings disguised themselves as bards and performed before Pāri. At the end of the performance Pāri asked what the bards wanted as gifts, and they asked for his kingdom and his life. Pāri offered his own kingdom and life to the three disguised kings overruling the objections from his warriors and people. Then, the three kings killed him. In a literary poetic work called the Pāri Kātai by Rā. Rākavaiyaṅkār, the famous Tamil scholar, who was an editor of the Akanāṉūṟu, says that the three kings sent a soldier disguised as a bard to sing before Pāri. After the performance, when Pāri asked the disguised soldier what gifts he wanted, he asked for Pāri himself. Pāri gave himself to the disguised soldier and followed him. The soldier took Pāri to the center of the gathered armies of the three kings. There the three kings killed him (Pāri Kātai 412–28). The important thing to note here is that there was treachery involving disguise to defeat a philanthropist. This is what I find important in the story of Pāri because in the story of Bali and Vāmana too, we have Viṣṇu, in effect, disguised as a Brahmin dwarf and deceptively asking for land that is measured in three strides. However, when Bali granted that request, the dwarf Vāṃana grew into his giant cosmic form and took away Bali’s sovereignty and exiled him to the netherworld. Pāri lost his sovereignty due to his enemies using treachery to exploit his sense of duty towards the bards. Bali lost his sovereignty due to his enemy, Viṣṇu, using treachery to exploit his sense of duty towards philanthropy towards the Brahmins. In both cases, the kings honored their personal code of philanthropy even when it meant a great loss to themselves personally. |

| 53 | Akanāṉūṟu 196.1-5 (Cōmacuntaraṉār Edition). |

| 54 | Aiṅkuṟunūṟu 49 (Cāminātaiyar Edition). |

References

Primary Sources

Aiṅkuṟūnūṟu Mūlamum Paḻaiyavraiyum. 1980. ed. U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar. Cēṉṉai: Tākṭar U. Vē. Cā Nūl Nilaiyam.Aiṅkuṟunūṟu Mūlamum Viḷakkavuraiyum. Part III. Mullai. 1958. ed. Auvai Cu. Turaicāmip Piḷḷai. Madurai: Annamalai University Tamil Series.Akanāṉūṟu Kaḷiṟṟiyāṉai Nirai. 1943. ed. Na. Mu. Vēṅkaṭacāmi Nāṭṭār and R. Vēṅkaṭācalam Piḷḷai. Ceṉṉai: Tirunelvēli Teṉṉintiya Caiva Cittāṇta Nūṟpatippuk KaḻakamAkanāṉūṟu Kaḷiṟṟiyāṉai Nirai. 1970. ed. Po Vē Cōmacuntaraṉār Eḻutiya Patavurai Viḷakkavuraikaḷuṭaṉ. Madras: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society.Akanāṉūṟu Kaḷiṟṟiyāṉai Nirai. 1990. ed. Vē. Civacuppiramaṇiyaṉ. Ceṉṉai: Ṭākṭar U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar Nūl Nilaiyam.Akanāṉūṟu Kaḷiṟṟiyāṉai Nirai: A Critical Edition and an Annotated Translation (3 volumes). 2018. ed. Eva Wilden. Pondicherry: École française d’Extrême-Orient and Tamilmann PatippakamAkanāṉūṟu Maṇimiṭai Pavaḷam, Nittilakkōvai. 1977. ed. Po Vē Cōmacuntaraṉār Eḻutiya Patavurai Viḷakkavuraikaḷuṭaṉ. Ceṉṉai: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society.Akanāṉūṟu Maṇimiṭai Pavaḷam. 1946. ed. Na. Mu. Vēṅkaṭacāmi Nāṭṭār and R. Vēṅkaṭācalam Piḷḷai. Ceṉṉai: Tirunelvēli Teṉṉintiya Caiva Cittāṇta Nūṟpatippuk Kaḻakam.Akanāṉūṟu Maṇimiṭai Pavaḷam. 1990. ed. Vē. Civacuppiramaṇiyaṉ. Ceṉṉai: Ṭākṭar U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar Nūl Nilaiyam.Akanāṉūṟu Mūlamum Paḻaiya Uraiyum. 1933. ed. Rā. Rākavaiyaṅkār and Irājakōpālāryaṉ. Mayilāppūr: Kampar Pustakālayam.Akanāṉūṟu Nittilakkōvai. 1944. ed. Na. Mu. Vēṅkaṭacāmi Nāṭṭār and R. Vēṅkaṭācalam Piḷḷai. Ceṉṉai: Tirunelvēli Teṉṉintiya Caiva Cittāṇta Nūṟpatippuk KaḻakamAkanāṉūṟu Nittilakkōvai. 1990. ed. Vē. Civacuppiramaṇiyaṉ. Ceṉṉai: Ṭākṭar U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar Nūl Nilaiyam.Annual Report for the Mysore Archaeological Department for the Year 1941. 1942. Mysore: University of Mysore.Annual Reports on Indian Epigraphy. 1906–1910. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1986.Annual Reports on Indian Epigraphy. 1940–1941. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1986Ceṅkam Naṭukaṟkaḷ. 1972. ed. Irā. Nākacāmi. Ceṉṉai: Tamiḻnāṭu Aracu Tolporuḷ Āyvuttuṟai.Cilappatikāra Mūlamum Arumpatavuraiyum Aṭiyārkkunallāruraiyum. 1985. ed. U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar. Tañcāvūr: Tamiḻppalkalaikkaḻakam.Ciṟupāṇāṟṟuppaṭai. 2000. ed. Po Vē Cōmacuntaraṉār. Ceṉṉai: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works, Publishing Society.Dravidian Etymological Dictionary. Second Edition. 1984. Thomas Burrows and Murray B. Emeneau. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Epigraphia Indica. 1892–1978. 42 volumes. Calcutta/New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.Harivamsha (Krishna’s Lineage: The Harivamsha of Vyāsa’s Mahābhārata.) 2019. Translated by Simon Broadbeck. New York: Oxford University Press.Kalittokai: Nacciṉārkkiṉiyarurai. 1969. ed. Po Vē Cōmacuntaraṉār. Madras: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society.Kallāṭam with Commentary by M. Nārāyaṇavēlup Piḷḷai. 1994. Ceṉṉai: Mullai Nilaiyam.Kiruṣṇakiri Māvaṭṭak Kalveṭṭukaḷ. 2007. ed. Irācakōpāl and Ca. Kiruṣṇamūrtti. Chennai: Tamiḻnāṭu Aracu Tolliyaltuṟai.Kōyamputtūr Māvaṭṭak Kalveṭṭukaḷ. 2006. ed. Ti. Pa. Śrītar. Ceṉṉai: Tamiḻnāṭu Aracu Tolliyaltuṟai.Kuṟuntokai. 3d ed. 1955. ed. U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar. Ceṉṉai: Kapīr Accukkūṭam.Kuṟuntokai: A Critical Edition and an Annotated Translation (3 volumes). 2010. Eva Wilden Eva. Pondicherry: École française d’Extrême-Orient and Tamilmann Patippakam.Mahābhārata. Volume 2. 1981. Translated and edited by J. A. B. van Buitenen. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.Maṇimēkalai. 1965. ed. U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar. Ceṉṉai: Kapīr Accukkūṭam.Maturaik Kāñci. 1977. ed. Po Vē Cōmacuntaraṉār. Madras: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society.Mysore Archeological Report.Naṟṟiṇai Mūlamum Viḷakkavuraiyum. 1966. ed. Auvai Cu. Turaicāmip Piḷḷai. Ceṉṉai: Aruṇā Papḷikēṣaṉs.Naṟṟiṇai Mūlamum Viḷakkavuraiyum: 201 Mutal 400 Varai. 1968. ed. Auvai Cu. Turaicāmip Piḷḷai. Ceṉṉai: Aruṇā Papḷikēṣaṉs.Pāri Kātai. 2d ed. 1978. Rā. Rākavaiyaṅkār. Aṇṇāmalainakar: Aṇṇāmalaip Palkalaikkaḻakam.Patiṟṟuppattu: Arāycciyurai. Pakuti I & II. Paḻaiyavurai Oppumaippakuti Palavakai Arāyccik Kuṟippukkaḷ Mutaliyavaṟṟuṭaṉ Paṇṭitar Cu. Aruḷampalavaṉār Iyaṟṟiyatu. 1965. Yāḻppāṇam: A. Civāṉantanātaṉ.Pattuppāṭṭu Mūlamum Maturaiyāciriyar Pārattuvāci Nacciṉārkkiṉiyaruraiyum. 1931. ed. U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar. Ceṉṉai: Kēcari Accukkūṭam.Periyapurāṇam Eṉṉum Tiruttoṇṭar Purāṇam. 1964–1975. ed. C. K. Cuppiramaṇiya Mutaliyār. Koyamputtūr: Kōvait Tamiḻc Caṅkam.Peruntokai. 1935–1936. Mu. Irākavaiyaṅkār. Madurai: Madura Tamil SangamPorunarāṟṟuppaṭai. 2001. ed. Po Vē Cōmacuntaraṉār. Ceṉṉai: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works, Publishing Society.Puṟanāṉūṟu: 1-200 Pāṭṭukkaḷ. 1996. ed. by Auvai Cu. Turaicāmip Piḷḷai. Ceṉṉai: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society.Puṟanāṉūṟu: 201-400 Pāṭṭukkaḷ. 1991. ed. by Auvai Cu. Turaicāmip Piḷḷai. Ceṉṉai: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society.Puṟapporuḷ Veṇpāmālai. 10th ed. 1994. ed. Po Vē Cōmacuntaraṉār. Ceṉṉai: The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works, Publishing Society.South Indian Inscriptions. 1890–2011. 30 volumes. Archaeological Survey of India.Tamil Lexicon. Six Volumes and Supplement. 1924-39. ed. S. Vaiyapuri Pillai. Madras: University of Madras.Tarumapuri Kalveṭṭukaḷ (Mutal Tokuti). 1975. ed. Irā. Nākacāmi. Ceṉṉai: Tamiḻnāṭu Aracu Tolporuḷ Āyvuttuṟai.Tirukkuṟaḷ: Parimēlaḻakar Urai. 1996. Ceṉṉai: Kaṅkai Puttaka Nilaiyam, 1996.Tiruttuṟaippūṇṭik Kalveṭṭukaḷ. 1978. ed. Irā. Nākacāmi. Ceṉṉai: Tamiḻnāṭu Aracu Tolporuḷ Āyvuttuṟai.Tiruvālavāyuṭaiyār Tiruviḷaiyāṭaṟpurāṇam. 1972. ed. U. Vē. Cāminātaiyar. Ceṉṉai: Śrī Tiyākarāca Vilāca Veḷiyīṭu.Tolkāppiyam. 1993. With the Commentary by Puliyūrk Kēcikaṉ. Ceṉṉai: Pārinilaiyam.Secondary Sources

- Ali, Daud. 2000. Royal eulogy as World History: Rethinking copper-plate inscriptions in Cola India. In Querying the Medieval: Texts and the History of Practices in South Asia. Edited by Ronald Inden, Jonathan Walters and Daud Ali. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 165–229. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Daud. 2007. The Service Retinues of the Chola Court: A Study of the Term Veḷam in Tamil Inscriptions. In Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. London: University of London, vol. 70, pp. 487–509. [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam, M. 1977. Harijan Saints of Tamilnadu. Tiruchitrambalam: Gandhi Vidyalayam. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbeck, Simon. 2019. Krishna’s Lineage: The Harivamsha of Vyāsa’s Mahābhārata. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cane, Nicolas. 2019. Temples, Inscriptions and Historical (Re)construction: The ‘Epigraphical Persona’ of the Cōḻa Queen Cempiyaṉ Mahādevī (Tenth Century). Bulletin de L’Ecole Française D’Extrême-Orient 105: 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cētuppiḷḷai, Rā. Pi. 2007. Tamiḻ Iṉpam, 15th ed. Ceṉṉai: Paḻaṉiyappā Piratars. First published in 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, P. N., T. K. Ravindran, and N. Subrahmanian. 1979. History of South India: Vol. I: Ancient Period. New Delhi: S. Chand & Company Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Elaine M. 2017. Hindu Pluralism: Religion and the Public Sphere in Early Modern South India. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gillet, Valerie. 2014. The Dark Period: Myth or reality? The Indian Economic and Social History Review 51: 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalachari, K. 1941. Early History of the Andhra Country. Madras: University of Madras. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, George L. 1975. Ancient Tamil Literature: Its Scholarly Past and Future. In Essays on South India. Edited by Burton Stein. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, George L. 2015. The Four Hundred Songs of Love. Pondicherry: Institut Français De Pondichéry. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, George L., and Hank Heifetz. 1999. The Four Hundred Songs of War and Wisdom. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hospital, Clifford. 1984. The Righteous Demon: A Study of Bali. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iḷaṅkumaraṉ, Irā. 1987. Pāṇar. Citamparam: Maṇivācakar Patippakam. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Sagarmal. 2007. Jain Litertature. 14th Biennial Jaina Convention Souvenir. New Jersey: Edison, pp. 129–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kācinātaṉ, Naṭaṉa. 1981. Kaḷappirar. Ceṉṉai: Tamiḻnāṭu Aracu Tolporuḷ Āyvuttuṟai. [Google Scholar]

- Kailasapathy, K. 1968. Tamil Heroic Poetry. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kersenboom-Story, Saskia. 1981. Viṟali (Possible sources of the devadāsi tradition in the Tamil Bardic period). Journal of Tamil Studies, International Institute of Tamil Studies 19: 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju. 2003. The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ludden, David E. 1996. Caste Society and Units of Production in Early-Modern South India. In Institutions and Economic Change in South Asia. Edited by Burton Stein and Sanjay Subrahmanyam. Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 105–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan, Iravatham. 2003. Early Tamil Epigraphy: From the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. Chennai: Cre-A and Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaswamy, R. 2012. Mirror of Tamil and Sanskrit. Chennai: Tamil Arts Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, Leslie. 2018. The Bhakti of the Bāṇas. In Clio and Her Descendants: Essays for Kesavan Veluthat. Edited by M. V. Devadevan. New Delhi: Primus Publications, pp. 347–86. [Google Scholar]

- Palaniappan, Sudalaimuthu. 2008. On the Unintended Influence of Jainism on the Development of Caste in Post-Classical Tamil Society. International Journal of Jaina Studies 4: 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Palaniappan, Sudalaimuthu. 2016. Hagiography versus History: The Tamil Pāṇar in Bhakti-Oriented Hagiographic Texts and Inscriptions. In Archaeology of Bhakti: Royal Bhakti, Local Bhakti. Edited by Emmanuel Francis and Charlotte Schmid. Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry and École française d’Extrême-Orient, pp. 303–46. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, R. 1993. The Cilappatikāram of Iḷaṅkō Aṭikaḷ: An Epic of South India. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piḷḷai, Es. Vaiyāpuri, ed. 1967. Caṅka Ilakkiyam. Ceṉṉai: Pāri Nilaiyam. [Google Scholar]

- Piḷḷai, R. L. Ārōkkiyam, and G. Poṉipās. 1966. Uyirkkoṭai Vaḷḷalkaḷ. Tūttukkuṭi: Tamiḻ Ilakkiyak Kaḻakam. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, N. 1992. Another Garland: Biographical Dictionary of Carnatic Composers & Musicians (Book II). Madras: Carnatic Classicals. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, T. N. 1931. The Bāṇas. The Journal of Oriental Research Madras 5: 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Velcheru Nararayana, and Gene H. Roghair. 1990. Śiva’s Warriors: The Basava Purāṇa of Palkuriki Sōmanātha. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rasanayagam, Mudaliyar C. 1984. Ancient Jaffna. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. [Google Scholar]

- Richman, Paula. 1988. Women, Branch Stories, and Religious Rhetoric in a Tamil Buddhist Text. Syracuse: Syracuse University. [Google Scholar]

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta. 1987. A History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar, 4th ed. Madras: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, A. 1946. Handwritten Notebook Containing Harikesanallur L. Muthiah Bhagavatar’s Compositions. Chennai: Music Research Library. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, McComas. 2021. The Viṣṇu Purāṇa: Ancient Annals of the God with Lotus Eyes. Acton: Australian National University. [Google Scholar]

- Thani Nayagam, Xavier S. 1995. Collected Papers of Thani Nayagam Adigalar. Madras: International Institute of Tamil Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Thapar, Romila. 2002. Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Tamil Varalatru Kazhagam. 1966. Thirty Pallava Copper-Plates. Madras: The Tamil Varalatru Kazhagam. [Google Scholar]

- The Tamil Varalatru Kazhagam. 1967. Ten Pandya Copper-Plates. Madras: The Tamil Varalatru Kazhagam. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, Edgar. 1909. Castes and Tribes in Southern India. Madras: Government Press, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tieken, Herman. 2001. Kāvya in South India: Old Tamil Caṅkam Poetry. Groningen: Egbert Forsten. [Google Scholar]

- Varatarācaṉ, Ve. 1973. Tamiḻppāṇar Vāḻvum Varalāṟum. Ceṉṉai: Paṇṇaṉ Patippakam. [Google Scholar]

- Vētācalam, Ve. 1987. Pāṇṭiya Nāṭṭil Vāṇātirāyarkaḷ. Madurai: Tolporuḷ Toḻilnuṭpap Paṇiyāḷar Paṇpāṭṭukkaḻakam. [Google Scholar]

- Zvelebil, K. V. 1975. Tamil Literature. Leiden/Koln: E. J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Zvelebil, Kamil V. 1992. Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature. Leiden: E. J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

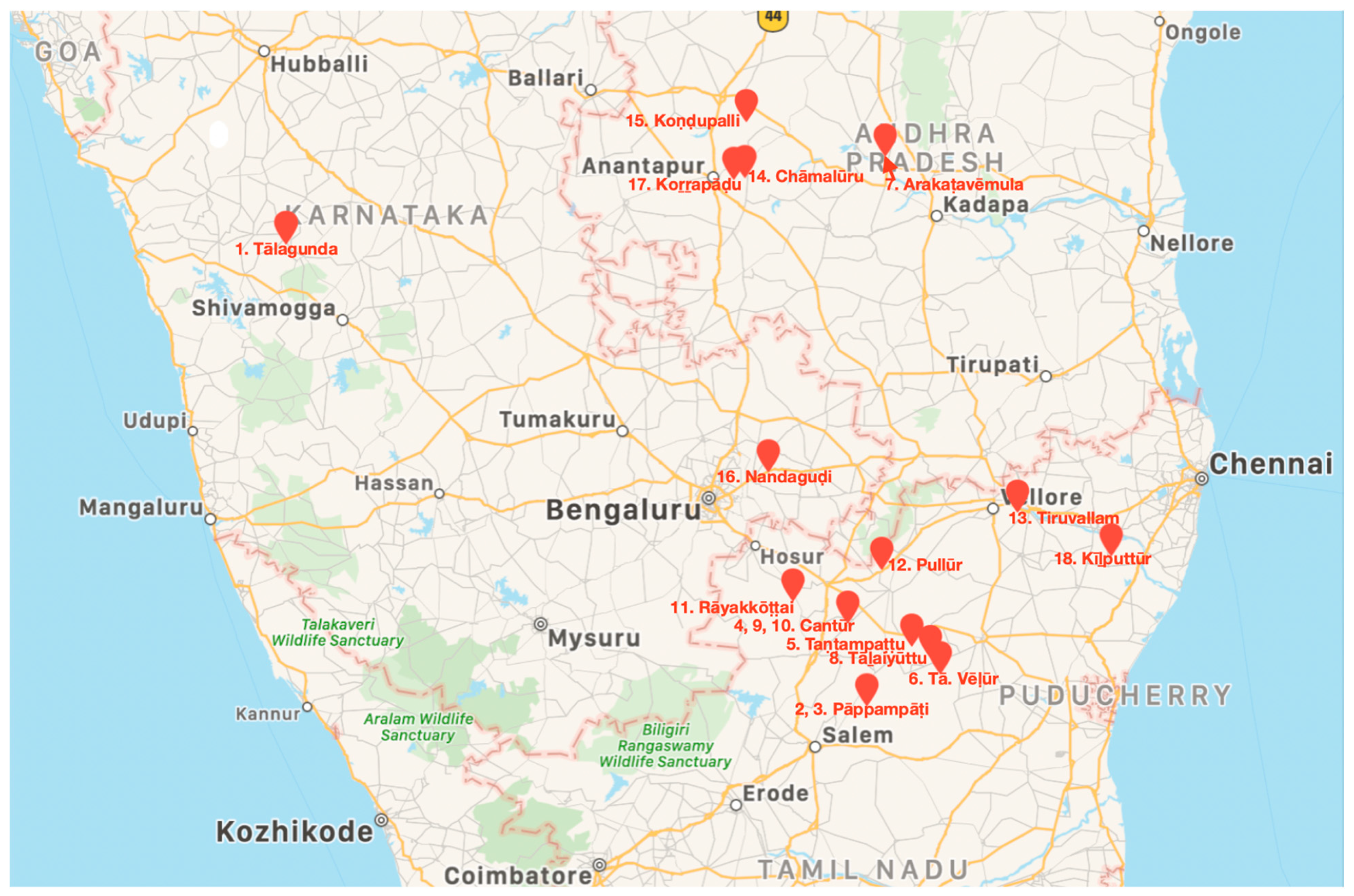

| Number | Date | Local Language | Place | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | fifth century | Kannada | Tāḷagunda, Shimoga district36 | Bṛhadbāṇa |

| 2 | fifth century | Tamil | Pāppampāṭi, Dharmapuri District | Vāṇaperumaraicaru |

| 3 | fifth or sixth century | Tamil | Pāppampāṭi, Dharmapuri District | Vāṇaparuma araicaru |

| 4 | sixth century | Tamil | Cantūr, Krishnagiri District | Perumpāṇaviḷavaraicar |

| 5 | seventh century | Tamil | Taṇṭampaṭṭu, Ceṅkam area | Perumpāṇaraicar |

| 6 | seventh century | Tamil | Tā. Vēḷūr, Ceṅkam area | Vāṇakōo Atiraicar |

| 7 | seventh century | Telugu | Arakaṭavēmula, Cuddapah District | Perbāṇa vaṃśa |

| 8 | eighth century | Tamil | Tāḻaiyūttu, Ceṅkam area | Perumpāṇatiyaraicar |

| 9 | eighth century | Tamil | Cantūr, Krishnagiri District | Perumpāṇilavaraicar |

| 10 | eighth century | Tamil | Cantūr, Krishnagiri District | Pāṇiḷavarai[*car] |

| 11 | eighth century | Tamil | Rāyakkōṭṭai, Krishnagiri District | Mahāvalivāṇarājar |

| 12 | eighth century | Tamil | Pullūr, North Arcot District | Bāṇādhipa |

| 13 | eighth century | Tamil | Tiruvallam (Vāṇapuram), North Arcot District | Mahāvalikulotbhava Śrīmāvalivāṇarāyar, Mahāvalivāṇarāyar |

| 14 | eighth century | Telugu | Chāmalūru, Cuddapah District | Vāṇarāja |

| 15 | eighth century | Telugu | Koṇḍupaḷḷi, Anantapur District | Bāṇarāja |

| 16 | eighth century | Kannada | Nandaguḍi, Bangalore District | Perbbāṇa Muttarasa |

| 17 | eighth century | Telugu | Koṟṟapāḍu, Cuddapah District | Perbāṇādhirāja (Perbāṇa-adhirāja) |

| 18 | ninth century | Tamil | Kīḻputtūr, Chingleput District | Perumpāṇaṉ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palaniappan, S. From Tamil Pāṇar to the Bāṇas: Sanskritization and Sovereignty in South India. Religions 2021, 12, 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111031

Palaniappan S. From Tamil Pāṇar to the Bāṇas: Sanskritization and Sovereignty in South India. Religions. 2021; 12(11):1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111031

Chicago/Turabian StylePalaniappan, Sudalaimuthu. 2021. "From Tamil Pāṇar to the Bāṇas: Sanskritization and Sovereignty in South India" Religions 12, no. 11: 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111031

APA StylePalaniappan, S. (2021). From Tamil Pāṇar to the Bāṇas: Sanskritization and Sovereignty in South India. Religions, 12(11), 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111031