Abstract

This paper considers Marian iconography in which the Virgin is depicted sitting on the ground, known as the Virgin of Humility. The creation of this Marian type coincides with Saint Thomas’s systematization of the virtues, which resulted in a decline in the importance of the virtue of Humility. The combination of both cultural traditions has led to a correspondence between the virtue of Humility and the images of the Virgin of Humility. The genesis of this latter type is based on the textual sources and part of the visual representation of Humility, which was replaced during the 14th and 15th centuries.

1. Introduction

Research on the visual representation of Humility has framed by the context of virtues as an object of study. Most studies on images of the virtues—including Katzenellenbogen (1939), Houlet (1969), and Norman (1998)—begin with Psychomachia depictions (battle between virtues and vices)1. Additionally, there are a few studies about the tree of virtues, but they are less abundant studies.

Images of Humility are usually approached generally in studies about virtues and vices, e.g., Barbier (1898) and Mâle (1925, 1986). Mâle explains the visual representation of Humility briefly and descriptively, exemplifying it with French works, but without explaining the origin and meaning of its image. Van Marle’s (1971) contribution is similar, because he describes some attributes of Humility, but he does not explain their meaning nor the literary sources. In the mid 20th century, Louis Réau (1955–1959) proposed the first classification of the visual representation of the virtues, including Humility, but explained it briefly and generally, and Sebastián (1988, 1994) continued this trend. Likewise, Tucker (2015) focused on the visual representation of the virtues as a set, while Tuve (1963, 1977) focused on the 15th and 16th centuries, O’Reilly (1988) on the medieval, Bonardi (2010) on French baroque, Cosnet (2015) on Italian art of the 14th century and Montesinos Castañeda (2019) on the visual representation of the Cardinal Virtues.

Although we find numerous studies of this kind, images of Humility are usually approached descriptively or in circumscribed examples. In explaining the attributes’ meaning, authors usually turn to Iconologia by Cesare Ripa, but this not contribute to the origin or meaning of the depictions. Thus, we do not find specific studies about the visual representation of Humility, the origin of its image, or its continuity and variation over time.

This is not the case for the Virgin of Humility, which putatively has a close relationship with the virtue of Humility and its sources. In the last hundred years, several published studies have attempted to locate the geographic and temporal origin of the Virgin of Humility type (King 1935; Meiss 1936; Trens 1946; Van Os 1969; Kirschbaum 1971; García Mahíques 1995; Réau 1996; Polzer 2000) or have treated specific works, such the earliest-known image of the Virgin of Humility, made in Avignon by Simone Martini (Sallay 2012). Beth Williamson alone has carried out a more exhaustive study of the topic, determining the origin of the iconographic type more specifically than the other authors with her book of 2007 titled The Madonna of Humility. Development, Dissemination and Reception, c. 1340–1400, in addition to articles about images such as that of the Avignon work (Williamson 2007).

Nevertheless, none of her previous works has considered a particularity of this iconographic type: the Virgin Mary is seated on the covered grass ground in a considerable number of images (Mocholí Martínez 2019). Likewise, many above-cited authors have tried to explain the reasons for the title given to the Virgin of Humility, but only a few of them have focused on the relation of this virtue with the seated position of the Virgin Mary. Moreover, almost none of these authors has placed the sources and/or the visual representation of the virtue in relation to the Virgin of Humility.

Thus, the objective of the present study was to establish the origins, continuity and variation of the depiction of Humility, making connections between the written sources on the virtue on one hand, and the Virgin of Humility on the other, whose visualities intersect.

2. The Virtue of Humility

The importance of Humility among the virtues was shown in different ways. Humility was depicted as the “Queen of Virtues” in the battle for the soul and the “Root of Virtues” in the tree of virtues. These depictions of personifications, as female figures with attributes, are the visual translations of written sources.

Since late Antiquity, Humility has appeared alongside the virtues in the famous battle of the soul, the Psychomachia. In the 2nd century, when Tertullian (c. 160–c. 220) decried the shows of the Roman arena, he argued that the veritable Christian fights were between vices and virtues (O’Reilly 1988, p. 13): “Adspice impudicitiam dejectam a castitate, perfidiam caesam a fide, saevitiam a misericordia contusam, petulantiam a modestia obumbratam, et tales sunt apud nos agones, in quibus ipsi coronatur” (Tert. spect. 29)2. At the end of the 4th century, the Christian poet Aurelius Prudentius (348–410) developed Tertullilan’s idea in an epic poem entitled Psychomachia. This poem presents a personified battle between vices and virtues, in which Humility appears: “et ad omne patens sine tegmine uulnus/et prostrata in umum nec libera iudice sese/Mens Humilis” (Prvd. psych. 246–8; PL LX, 611)3. However, characterizations of Humility in that battle do not correspond with Prudentius’ description of this virtue. Humility is personified as a woman and armed, and she does not have any distinctive sign identifying her beyond an inscription such as one that appears in the Speculum Virginum by Conradus Hirshauensis (c. 1140, London, British Library, MS. Arundel 44, fo. 34v) and in the façade of Saint-Pierre d’Aulnay (12th century).

Besides her relationship with the ground, Prudentius proposed Humility as the “Queen of Virtues”. This idea was taken up by Hildegard of Bingen (1151) in her Ordo virtutum: “Ego, Humilitas, /regina Virtutum, dico: /uenite ad me, Virtutes, /et enutriam uos ad requirendam perditam dragmam/et ad coronandum in perseuerantia felicem”4 (vv. 116–20). The relevance of Humility in the Ordo virtutum is evident in her actions. She opens and closes the lengthy second scene and she organizes the devil’s defeat, being the only one who speaks directly to the soul (Santos Paz 1999, pp. 49–50). Augustine of Hippo’s rhetoric, based on stylistic humility (sermo humilis), explains the preeminence of Humility. Additionally, Benedict of Nursia praised this virtue in his monastic rule, where she is considered “Regina virtutum” (Santos Paz 1999, p. 48).

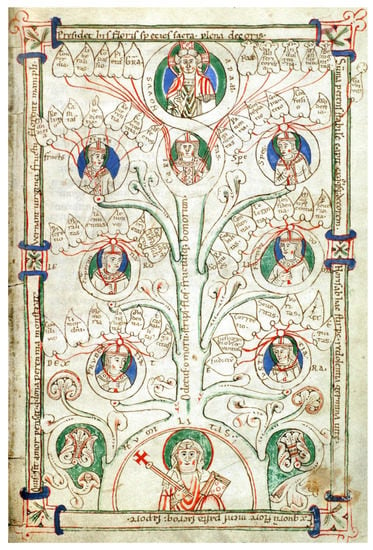

It is unsurprising that Humility was highlighted among the virtues given that Hugh of Saint Victor (c. 1096–1141) considered it the “radix virtutum” in De fructibus carnis et spiritus5 (Figure 1), where he presents two trees. The first one is the old tree of Adam, whose root and stem is Pride and whose seven branches are the vices, with each branch diversifying into related vices (Sebastián 1988, p. 290). The second is the new tree of Adam, whose trunk is Humility, and its seven main branches are the cardinal and theological virtues (Mâle 1986, p. 119). The organization of the virtues into a tree diagram was reproduced in different works, such as the Speculum theologiae (s. XV, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 3473, fo. 82) or the Psychomachia by Prudentius (s. IX–X, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 8318, fo. 62v). All of these works have in common that “humilitas est radix omnium virtutum”. Thus, just as each virtue is represented as a branch of the tree whose leaves are the parts that compose it, the branches, in turn, form the parts that compose Humility (Cames 1971, p. 56).

Figure 1.

Tree of Virtues, De fructibus carnis et spiritus, Hugh of Saint Victor, 12th century, Salzburg, Studienbibliothek, MS. Sign. V. I. H. 162, fo. 76.

In the same sense, Augustine of Hippo conceived Humility as the foundation of any building in Sermones de verbis Domini et apostoli6. Later, Thomas Aquinas, inspired by Augustine of Hippo’s characterization of this virtue, explained: “humility is said to be the foundation of the spiritual edifice”(Aquinas 1225)7. Consequently, the idea of Humility as the queen and the root of all virtues was translated visually as the root of the tree of virtues. For example, Humility appears as the origin of the virtues in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris (Katzenellenbogen 1939, p. 75). This thought persisted throughout the Middle Ages, and appears for example in Chapter XXXIV of the Flor de virtudes (1488–1491):

“E de la humildad descienden e proceden estas virtudes: la primera es fazer honra a todo hombre; la segunda es reverencia, conviene saber, catar honra al mayor de sí; la tercera es obediencia, conviene saber, obedecer a quien tiene poder de mandar; la quarta es agradecimiento, conviene saber, reconoscer e agradecer el servicio o placer que se recibe e fazerles d’ello agradecimiento”.(Mateo Palacios 2013, pp. 117–8)

2.1. The Allegory of the Virtue of Humility

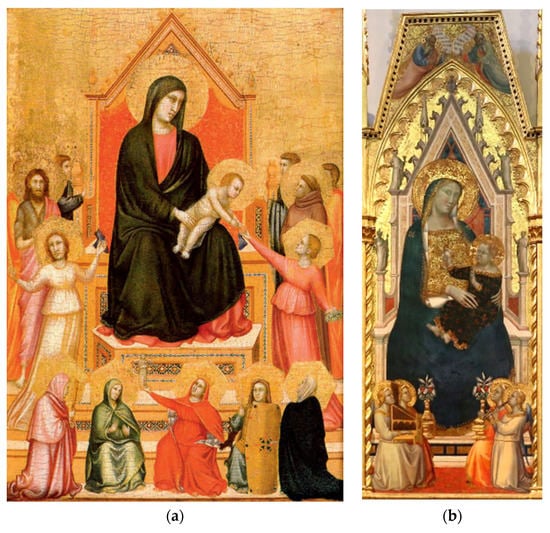

Even though written sources describe Humility as the queen, root, and foundations of the virtues, its first depictions did not visually translate these ideas. In Paris Cathedral (c. 1210–1215), Amiens (1220–1235) (Figure 2) and Chartres (c. 1230–1240), Humility carries a shield with a dove as a motto, such as in an Apocalypse manuscript of the 13th century (the tree of virtues, c. 1290–1299, Herefordshire, Wormsley Library, lot 32b no. 5, fo. 6r). It was in the 14th century that Humility began to be depicted in connection with the ground. We find Humility in a kneeling position in a panel attributed to Giotto depicting the Virgin and Child surrounded by saints and virtues (c. 1315–1320) (Figure 3a), while in Santa Felicità polyptych painted by Taddeo Gaddi (c. 1355) (Figure 3b) Humility carries a flower and a lamb8. However, Humility personified is not associated with the ground in Somme le roi (1295, Frère Laurent, Paris, Bibliothèque Mazarine, MS. 870–1, fo. 89v) where she wears a crown, highlighting her role as Regina virtutum. This idea remained until the 15th century, as seen in the Speculum humanae salvationis (c. 1440–1466, Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cgm 3974, fo. 78r). In this work, Humility also carries flowers, whose explanation is Flor de Virtudes (1488–1491): “Sant Isidoro dize: ‘Assí como la sobervia es rahíz e simiente de todos los vicios, assí la homildad es reina de todas las virtudes’” (Mateo Palacios 2013, p. 122).

Figure 2.

Humility, 1220–1235, Amiens Cathedral.

Figure 3.

(a) Virgin with the Child surrounded by saints and virtues, c. 1315–1320, attributed to Giotto, private collection; (b) Santa Felicità polyptych, c. 1355, Taddeo Gaddi, Florence, Santa Felicità.

Despite the fact that the Scriptures highlight the importance of Humility9, it was not considered one of the seven cardinal—prudence, justice, fortitude and temperance—and theological virtues—faith, hope and charity—. Although its presence was essential in the first classifications of virtues as tree diagrams, Thomas Aquinas’ systematization considered it one of Temperance’s virtues10, losing its preeminence among the other virtues. In the 14th century, Thomas Aquinas’ moral treatises had many repercussions on the representation of the virtues. The cardinal and theological virtues as a group of seven (sometimes including Humility), were conventionalized (North 1979, p. 214). Thereby, Humility went from being the root and the Queen of the Virtues to becoming the eighth virtue that completed the group (McGuire 1990, p. 191). Sometimes, Humility even disappeared from depictions of the virtues, as in the Giotto’s series in Scrovegni Chapel (1305–1306, Padua) or The Allegory of Good Government by Ambroggio Lorenzetti (1338–1339, Siena, Palazzo Publico, Sala della Pace), where only Aquinas’ virtues are depicted.

Curiously, while the depiction of Humility as a virtue was in decay, the Virgin of Humility’s iconographic type had begun to develop. This relationship was not accidental, since Saint Thomas had already considered Humility to be one of Temperance’s virtues, next to Virginity and Chastity (S.Th. IIª-IIae, q. 151–2). Moreover, this author directly related Humility to Chastity: “[…] Isidorus dicit, in libro de summo bono, quod sicut per superbiam mentis itur in prostitutionem libidinis, ita per humilitatem mentis salva fit castitas carnis”11 (S.Th. (45114) IIª-Iiae q. 153 a. 4 arg. 2). Robert Grosseteste in Chateau d’amour (c. 1230–1240) presents a similar idea, placing the Virgin Mary in relation to Humility: “C’est le cuer la duce Marie, /ki onkes en mal ne mollist, /Me a Deu servir se prist, /E sa seinte virginité/Gardat en humilité” (Grosseteste 1918, p. 107; vv. 672–6)12. This author explains that the Chateau d’amour is built on a rock (vv. 588–9) which means the Virgin’s heart (Snow 2012, p. 36), the faith of which is the foundation of the other virtues (Snow 2012, p. 37; vv. 681–90). Thus, the Virgin of Humility is crowned as the Queen of the Virtues, being the foundation or the root upon which they rise.

Therefore, written sources related Humility with the ground, but the earliest depictions of Humility did not show that. When the depiction of Humility was in decline, the Virgin of Humility’s iconographic type began to develop.

2.2. Origin of the Virgin of Humility

We will see the main characteristics of the iconographic type of the Virgin of Humility when it emerges: the Virgin’s relationship with the Annunciation and the breastfeeding of Christ. In the next sections, we will interrogate their connection with the virtue of Humility.

This type emerged in a fairly well-defined period of time. Although we do not know which images were first, the oldest surviving ones date to the 1340s. The place of their creation is also uncertain, as the first known image is the work of an Italian painter, Simone Martini, although it was made for the cathedral of Notre-Dame-des-Doms in Avignon (Figure 4). In fact, the manuscripts of the Apocalypse, which would have been at the origin of this type, were made in France (Williamson 2009, pp. 29–51) as some attributes of the Woman of the Apocalypse (the sun, the moon and/or the stars) highlight, especially, in the earliest images. In a miniature of the Queen Isabella’s Apocalypse (1313, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS. Fr. 13096, fo. 35), the Mulier amicta sole is seated on the ground with the Child in her arms, while in the previous Apocalypses, Mary sits alone after having fled into the desert with wings (Apoc 12,6). In any case, the Virgin of Humility had great popularity in much of Europe (especially in Italy and in the Crown of Aragon, but also in France, Germany, and Bohemia) between the late 14th and early 15th centuries. Like its formation, its disappearance was equally rapid, since it had practically ceased to be represented at the beginning of the 16th century, although there are some examples in the Modern Era.

Figure 4.

Virgin of Humility, Simone Martini, 1341, from Notre-Dame-des-Doms, papal palace of Avignon.

We can recognize the type of the Virgin of Humility because Mary always appears seated on the ground. In fact, this is the only constant feature in these images, as others are not consistent, such as the apocalyptic elements. The Virgin tends to bow her head and, sometimes, to lower her gaze, and she almost always carries the Child, although there are examples in which she is still pregnant (Madonna del Parto, Antonio Veneziano, second half of the 14th century, Parrocchia San Lorenzo a Montefiesole, Pontassieve, Florence). Two of these particularities deserve to be highlighted, to further our understanding of this type and its relationship with Humility, which we will discuss below.

In many images, mainly belonging to the first decades of the existence of this type, there are visual or written references to the Annunciation, or rather the Incarnation of Christ. Although the latter event happens immediately after the former, the iconic representation of both episodes tend to show them as simultaneous: the archangel Gabriel greets Mary at the same time as the Holy Spirit enters towards her. There are two kinds of visual references to this other type. On the one hand, we find the complete scene of the Annunciation/Incarnation, where Gabriel and the Virgin Mary (usually located in the upper corners of the work) are considerably smaller than the Virgin of Humility (Figure 5a). Alternatively, some attributes of the Annunciation may appear next to the Virgin of Humility: the lily, the book that Mary would have been reading before being interrupted by the archangel or even the Holy Spirit that would have enabled the Incarnation of the Son of God (Figure 5b)13.

Figure 5.

(a) Madonna of Humility with saint Dominic and a donor, Maestro delle Tempere francescane, 1350–1355, Naples, Museo di Capodimonte; (b) Madonna of Humility with the Eternal Father, the Holy Spirit and the Twelve Apostles, Francesco di Cenni, 1375–1380, Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, Barcelona, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 212805-000.

Lastly, in most of the images where the Child appears, his mother is breastfeeding him or she presents an attitude that refers to the Virgo Lactans, which is often confused with the Virgin of Humility type (Mocholí Martínez 2017). In any case, whether the Child is suckling or is simply being held by his mother, as long as Mary is directly seated on the ground, it is invariably an image of the Virgin of Humility.

Thus, in Mary’s connection with the ground lies the key to her relationship with the virtue of Humility. And, far from being anecdotal, the rest of its features contribute to it.

3. The Humility of the Virgin

One of the hypotheses that attempts to explain the formation of this type considers that this would have been preceded by a progressive descent of the Virgin to the ground in images depicting various episodes of her life (Polzer 2000, p. 2; Sallay 2012, pp. 104–5; Williamson 2009, p. 121). However, none of them satisfactorily explains the presence of all the elements mentioned above, especially the apocalyptic ones. These would come, as we have advanced, from the adaptation of images of the Mulier amicta sole sitting on the ground, as in Queen Isabella’s Apocalypse (1313, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS. Fr. 13096, fo. 35). Following the devotional use of the Apocalypse, such imagery was developed in France (in or around Metz) in the first half of the 14th century; the breastfeeding was subsequently added to it. Williamson considers that the new type refers to the Incarnation of Christ, so that it would end up replacing, or assimilating, images of the Annunciation in certain manuscripts (Williamson 2009, pp. 55–57).

However, it is not only a matter of assimilation of one type by another; we also consider that the Annunciation/Incarnation of Christ plays a more important role in the genesis of the Virgin of Humility. In the next sections, we will discuss the importance that the references to the Incarnation acquire in the characterization of the iconographic type of the Virgin of Humility and its relation with representations of Humility, specifically, the tree of virtues. From there, we will discuss how the association between humility and chastity is visually manifested. In this sense, the representation of Mary as Virgo Lactans and her location in a wild environment plays an important role. Lastly, the visual representation of this Marian type, especially in the 15th century, tries to palliate the humility of the Virgin with the addition of a crown and other luxury items.

3.1. Humility and Incarnation of Christ

One of the first images of the Virgin of Humility was painted by Roberto d’Oderisio (c. 1345, Naples, Museo di Capodimonte) and shows a vase with lilies. This also appears in the image of Avignon (Figure 4), but in addition the Neapolitan one also presents a written reference to the Annunciation in the halo of Mary: ave maria, gratia plena. On both sides, one can also read mat[er] omnium, which alludes to the mercy of the Virgin, rather than to her humility. The same duplicity exists in the allusions to the Incarnation in an image of Silvestro dei Gherarducci (Madonna of Humility, after 1350, Florence, Accademia). The attributes are the closed book on the ground, next to Mary and a Christomorph Father at the top who sends the Holy Spirit. However, in addition, at the bottom edge of the work, a phrase from the Magnificat relates the Incarnation of Christ to the humility of the Virgin, by accepting her to be the Mother of God: respexit humilitatem ancille sue ecce e[nim] ex hoc b[ea]ta[m] me [dicent] (For he has had pity on his servant, though she is poor and lowly placed: and from this house will all generations give witness to the blessing which has come to me; Lk. 1,48).

A few years earlier, Bartolomeo Perellano, or da Camogli had made a Virgin of Humility (1346, Palermo, Galleria Regionale della Sicilia) in which the two figures of the Annunciation are present, as explained above. In addition, on each side of the Virgin, the first known inscription that identifies Mary as n[ost]ra d[on]na de humilitate appears14. More than two decades later, Paolo da Modena’s image of the same subject (1370, Modena, Galleria Estense) includes an inscription with the title la nostra donna dumilita […]. Likewise, a painting by Caterino Veneziano (late 1370s, Cleveland Museum of Art) includes a similar inscription: S[AN]TA MARIA DE UM[I]LITATE15.

At this point, the union between type and title is already consolidated. This occurs almost three decades after the work of Avignon. The delay may be due to the fact that, at the beginning, the title Virgin of Humility would not be associated with the iconographic type, nor was Mater Omnium, but only an epithet in memory of one of the qualities of Mary (Mocholí Martínez 2019, pp. 117–9). However, the relation of the ground with the virtue of Humility, prior to the appearance of the Marian type, suggests another possibility: both the sources and the earlier representations of the allegory of Humility would have allowed the association to be established from the beginning, although it was not always reflected in the inscriptions.

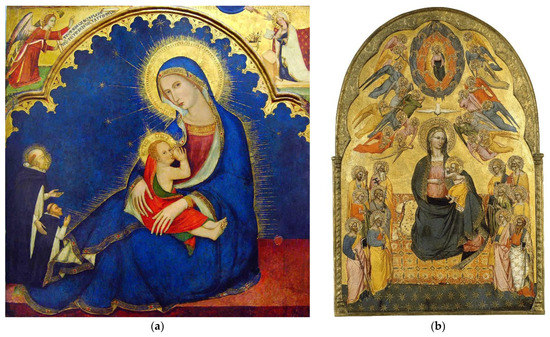

Based on these works, the acceptance of Mary after the Annunciation, present in one way or another in many of these images, would end up associating this type with the humility of the Virgin. However, we argue that opposite could have occurred: Humility, as a virtue, could have been the cause of the association of the Annunciation with the iconographic type. One reason for this is that Saint Thomas recovered the etymological relationship that had been established by Saint Isidore between humus and humilitas16, whose first meaning is proximity to the ground: “[…] sicut Isidorus dicit, in libro etymol., humilis dicitur quasi humi acclinis, idest, imis inhaerens”17 (S.Th. (45461) IIª-IIae, q. 161 a. 1 ad 1). The Virgin of Humility, consequently, not only sits on the floor where the virtue of Humility was also located, but in relatively early images of the type, she also sits directly on the ground covered with grass and wildflowers, like the Madonna of Vyšehrad (Figure 6a), the Virgin of Humility by Giovanni da Bologna (Figure 6b), or the final one by Lippo di Damasio (Figure 6c). The relation of these works to the type of the tree of virtues that we have already mentioned is evident, in which the virtue of Humility is the root from which the tree grows, whose branches are the rest of the Virtues.

Figure 6.

(a) Madonna of Vyšehrad, Bohemian painter, c. 1360, Praga, National Gallery; (b) Madonna dell’Umiltà, santi e confratelli della Scuola di san Giovanni Evangelista, Giovanni da Bologna, c. 1370, Venice, Accademia di Belle Arti, 17; (c) Madonna of Humility, Lippo di Dalmasio, c. 1390, London, National Gallery, NG752.

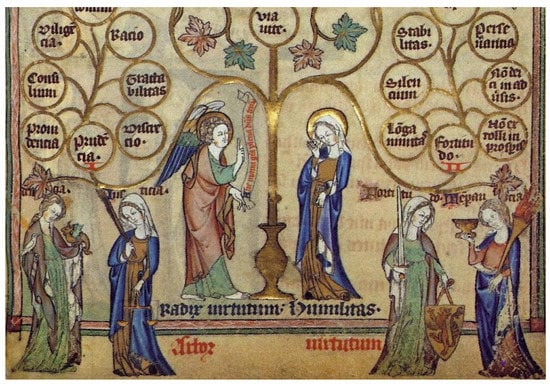

From the 13th century, the relationship between humility and the land became closer, especially in the Franciscan context. According to Saint Bonaventure, terra was a symbol of the humility of Mary, which “prius tamen germinando herbam sanctarum cogitationum, affectionum, locutionum et operationum”18. Furthermore, she is identified with “terra fertilissima fecunditate”19 (De Annuntiatione B. Virginis Mariae. Sermo III), which was opened to let the Saviour sprout (Is. 45,8). These sources concur that the virtue of Humility was closely associated with Mary. At the same time, the popularity of the tree of virtues grew throughout Europe, some of whose images have a significant particularity: the allegory of the virtue of Humility was replaced by an image of the Annunciation.

An example appears in an illuminated manuscript of the Speculum theologiae (Figure 7) from the 13th century. Gabriel kneels before Mary and raises one hand while holding a phylactery bearing the traditional salutation. Through another phylactery, the future Mother of God answers: ecce ancilla d[omi]ni f[iat] m[ihi] (I am the servant of the Lord; may it be to me as you say; Lk. 1,38). The inscription that flanks both figures affirms, as had been made clear in previous trees of virtues, that humilitas est radix omnium virtutum (Humility is the root of all virtues). Behind the Virgin, the trunk of the tree emerges, but what is striking is that two of the branches are born from her breasts, on which she lays her hands, in anticipation of breastfeeding, a consequence of the Divine Incarnation of her Son.

Figure 7.

Tree of Virtues, Speculum theologiae, 13th century, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS. fr. 9220, fo. 5v (detail).

It should be emphasized that most of the images of the Virgin of Humility are, in addition, lactating Virgins, which would have mainly stressed the divine motherhood of Mary. This would be linked, as we have seen, to her humility, in relation to the Incarnation which, especially in the first representations of the type, has been repeatedly manifested, both visually and textually. Thus, the episode of the Annunciation in which Mary humbly accepts to be the mother of the Son of God would have had a greater relevance in this type that would have been granted at first.

The De Lisle Psalter (Figure 8), dated between 1308 and 1340, immediately before the first known images of the Virgin of Humility, also has at its base an image of the Annunciation, under which an inscription reads radix virtutum humilitas (Humility is the root of virtues). The four cardinal virtues are represented, by their respective allegories, on both sides of Humility/Annunciation. The archangel greets Mary in the same way as in the previous image, although unlike that one, he does not kneel. She does not answer either, but raises a hand in surprise. Between them is a vase where there should be a lily staff, but instead, it holds the tree of virtues, whose leaves resemble wine branches.

Figure 8.

Tree of Virtues, De Lisle Psalter, London, British Museum, Arundel MS. 83 II, fo. 129r (detail).

The place from which the tree grows is also significant in this case. If it did emanate from the breast of Mary in the image of the Speculum theologiae, here it rises from the pot. In other words, the stem replaces the attribute that should allude to the perpetual virginity of the Mother of God, the lily, despite her motherhood and subsequent lactation. In this sense, it is worth mentioning that virginity and humility are closely linked, so the virtue of Humility also refers to the virtue of Chastity. As we have seen, this relationship was previously established by Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225; S.Th. (45114) IIª-IIae q. 153 a. 4 arg. 2).

3.2. Humility and Chastity

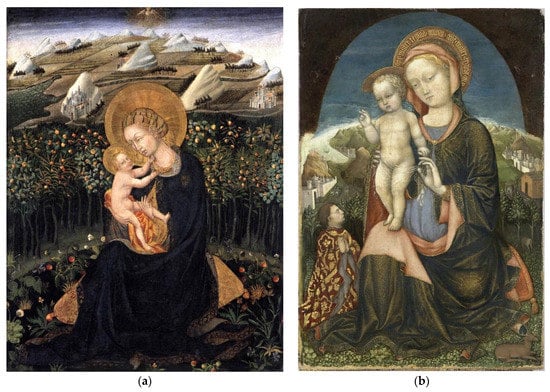

We can also appreciate this relationship between humility and chastity in the images of the type that concerns us, and not only by the presence of the vase of lilies. As we have already analyzed, the etymological root of the word humilitas refers to the location of the virtue of Humility in the root from which the rest of the virtues emanate, as well as with the location of the Virgin of Humility on the ground (Figure 9a). The ground is strewn with grass, small flowers, and wild plants. It should be remembered that the references to Mary’s virginity, when compared with wild vegetation, go back several centuries before the creation of this type. Saint Bernard, in his commentary on the prophecy of Isaiah, says of Christ, paraphrasing the Song of Songs, that

Likewise, Saint Bonaventure defines Mary as “terra ista, in qua homo non est operatus” (Saint Bonaventure, De Annuntiatione B. Virginis Mariae. Sermo III)21.[…] flos campi est (Cant II, 1), et non horti. Campus enim sine omni humano floret adminiculo, non seminatus ab aliquo, non defossus sarculo, non impinguatus fimo. Sic omnino, sic Virginis alvus floruit, sic inviolata, integra et casta Mariae viscera, tanquam pascua aeterni viroris florem protulere; cujus pulchritudo non videat corruptionem, cujus gloria in perpetuum non marcescat (Saint Bernard, Sermones de Tempore. In Adventu Domini. Sermo II, 4. PL 183, 42)20.

Figure 9.

(a) Madonna of Humility, Giovanni di Paolo, c. 1442, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 30.772; (b) La Vierge d’Humilité adorée par un prince de la maison d’Este, attrib. Jacopo di Niccolo Bellini, second quarter of the 15th century, Paris, Musée du Louvre, RF 41.

Although this dates from 1442, a small image of the Virgin of Humility (Figure 9b) could be interpreted in this sense, more clearly than in other works due to the disposition of Mary in a circle formed by fruit trees. In the center, the Mother of God sits on a cushion placed on a fertile meadow full of wild plants with flowers and fruits. On this occasion, the Child does not breastfeed, but caresses his mother’s chin, as in the Virgin of Tenderness, and turns his gaze to the spectator. At a certain distance from both figures, judging by their small size, a belt of fruit trees of different species is arranged in a semicircle. Beyond the trees, a vast expanse of farmland dotted with mountains and some walled cities can be seen. The anthropized environment that serves as a backdrop to Mary is a variation, with respect to the images above, on the Virgin of Humility type. Its presence emphasizes the uncultivated character of the place where the Mother of God sits.

On the contrary, although they may seem similar to this one, the images of Mary in a landscape, closed or not, belong to another type, because the human intervention, which characterizes the orchard or the garden, is opposed to the ultimate meaning of the Virgin of Humility. We would be facing the formation of the type known as Virgin of the Rose Garden, which originates in Paris, at the beginning of the 15th century, and then spreads through Germany and even northern Italy (Mocholí Martínez 2019, p. 134). A variation of this type presents Mary inside a hortus conclusus, alluding to her virginity. This virtue, as explained, could also be implicit in the images of the Virgin of Humility, in contact with the earth. A study that we intend to undertake is to check to what extent there is an equivalence between the plants and flowers of both types, beyond the lilies and, in some cases, the roses. Thus, the presence of violets is frequent in the oldest type since this flower is associated with humility in general and the Virgin in particular (Levi d’Ancona 1977, pp. 398–9).

3.3. Humility and Exaltation

From the end of the 14th century, the Virgin of Humility presents a series of variants that agree with some sources on the virtue of Humility, more so than the few allegorical images of it of that century. Saint Thomas Aquinas said: “Et eodem modo humilitati promittitur spiritualis exaltatio, non quia ipsa sola eam mereatur, sed quia eius est proprium contemnere sublimitatem terrenam. Unde Augustinus dicit, in libro de poenitentia, ne putes eum qui se humiliat, semper iacere, cum dictum sit, exaltabitur” (In the same way spiritual uplifting is promised to humility, not that humility alone merits it, but because it is proper to it to despise earthly uplifting. Wherefore Augustine says (De Poenit. (Serm. cccli)): “Think not that he who humbles himself remains for ever abased, for it is written: ‘He shall be exalted’); (Aquinas 1225; S.Th. (45500) IIª-IIae, q. 161 a. 5 ad 3), as “He has put down kings from their seats, lifting up on high the men of low degree” (Lk. 1,52). Juan de Mena in the first half of the 15th century repeated the same idea through a metaphor that alludes to the connection of Humility with the earth and recalls its root condition: “el humilde que se enclina/es planta que se traspone, /quanto mas fondo se pone/tanto cresce mas ayna” (Mena 1912, p. 126).

These statements find a correlation in the 15th century images of the type. The humility of Mary is still significant, with her seated position on the ground, but her sublimity is also alluded to because, as Mother of God, she deserves the title of Regina Coeli and, as such, she is exalted. Thus, the humility of the Virgin, for which, precisely, she deserves to be exalted, is alleviated with several means. In some cases, the Virgin sits in front of the back of a throne with arms, but without a seat; in others, what stands behind Mary is a rich brocade cloth. Finally, especially among the images of the Crown of Aragon, it is common for the Virgin of Humility to wear a crown (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Madonna of Humility and musician angels, Jaume Cabrera, last quarter of the 14th century and first quarter of the 15th century, Museu episcopal de Vic, MEV 1948.

The Virgin shares this last attribute with the allegory of Humility at the end of the Middle Ages. When the Marian type practically disappears, the allegory of Humility again gains an important presence and even becomes diversified in its representations.

Far from distorting the type by the introduction of these luxury items, the crowned representation of the Virgin is in keeping with part of the allegorical representation of the virtue of Humility.

4. Continuity and Variation of Humility’s Iconographic Type

Beyond theoretical considerations, Humility has been depicted through different iconographic types since the 14th century. Medieval sources explained that Humility is the “Queen of Virtues” and the “root of Virtues”. In Early Modern Era, medieval theoretical considerations were translated visually in different iconographic types.

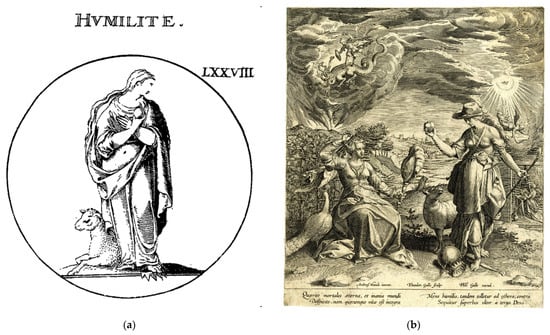

In Le chemin de Vaillance de Jean de Courcy (c. 1483, London, British Library, Royal 14 E II, fo. 123), Humility personified with the left hand on her chest and raising the right hand. According to Ripa (2007, p. 499), “la mano al petto, mostra, ch’il core pe la vera stanza d’humiltà”22, while “la destra aperta è segno che l’humiltà, debe essere reale, & patiente” (Ripa 1603, p. 214)23. However, although Ripa explains these features, he also explains further attributes for this iconographic type that are not usually depicted24. Ripa’s next characterizations are more common; Humility is dressed in white25, carries a lamb26, and tilts her gaze, as in the frontispiece of A Fourme of Prayer with Thankesgiving (c. 1600–1603, London, British Museum). Such depictions, in which the virtue gazes downward, originate in Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas’ texts. However, the Virgin of Humility has only tilted her gaze in images since the 14th century.

In the third statement, Ripa explains that Humility is dressed in a sack27, carries a bread basket28 and a pouch29, and steps on luxurious clothes30. Nonetheless, we don’t find Marian works that depict these attributes. However, his last statement is more often found: Humility is described as a “Donna vestita di colore bertino, con le braccia in croce al petto, teniendo con l’una delle mani una palla, una cinta al collo, la testa china, & sotto il piè destro haverà una corona d’oro” (Ripa 1603, pp. 214–5)31 (Figure 11a). Similarly, in the Allegory of Pride and Humility (c. 1612–1633) (Figure 11b) there is a crown at Humility’s feet as a sign of contempt for richness32. Moreover, behind Humility, the Annunciation is depicted, showing the continuity of the representation of this episode concerning this virtue. Additionally, above Pride, the apocalyptic episode of Saint Michael battling the dragon is depicted, which connects to the apocalyptic origin of the Virgin of Humility. Thus, the crown constitutes an attribute with an ambiguous meaning within representations of Humility. This is because sometimes this virtue is crowned according to the medieval idea of Regina virtutum, as appears in an engraving of the British Museum (c. 1535–1590) (Figure 12a).

Figure 11.

(a) Humility, Iconologia, 1643, Cesare Ripa, Paris; (b) Allegory of Pride and Humility, c. 1612–1633, London, British Museum, 1875,0710.2768.

Figure 12.

(a) Virtue against Vice and Humility, c. 1535–1590, London, British Museum; (b) Allegory of Humility, Marcantonio Franceschini, 1715, Heiligenkreuz, Stift Heiligenkreuz.

The Allegory of Humility by Marcantonio Franceschini (1715, Heiligenkreuz, Stift Heiligenkreuz) (Figure 12b) shows the crown’s ambiguity as an attribute of this virtue. Apart from tilting her gaze, carrying a sphere, and being accompanied by a lamb, at Humility’s feet, there is a crown, while a putto is crowning her at the same time. In addition, Humility is kneeling on the ground, as in the frontispiece of Devout contemplations (1629, Cristóbal de Fonseca, Pitts Theology Library), in an engraving by Rubens (c. 1632, London, British Museum) or in the Allegory of Humility by Jacopo Amigoni (1728, Ottobeuren, Benediktinerabtei). Therefore, medieval thinkers’ considerations about Humility concerning the ground, mainly since its conception as radix virtutum, were translated into the visual representation of this virtue during the Early Modern Era. An example of this is a French manuscript of the 16th century (c. 1516, Gabrielle de Bourbon, Paris, Bibl. Mazarine, MS. 0978, fo. 31v) where Humility is barefoot on a grassy ground. Thus, the Virgin of Humility visually showed her relation to the ground long before the virtue, which gives name to her advocacy. Although in the 14th century, there are some examples of Humility in contact with the ground, it was not until the Early Modern Era that this aspect began to be more frequent in its depictions. This aspect shows continuity until the 18th century, as can be seen in Sebastian Troger’s work (c. 1765–1769, Birkenstein, Saint Mariae Verkündigung)

In the Early Modern Era, images of Humility personified depict medieval features. Her contact with the ground and coronation were aspects depicted in many works. However, such medieval features also resulted in ambiguous attributes, namely the crown.

5. Conclusions

In short, we have revealed the relationship between the sources and the visual representation of Humility personified as a woman and the Virgin of Humility type. The Marian type appears shortly after the virtue loses its relevance that it had had during the Early and High Middle Ages; this was largely due to the systematization carried out by Saint Thomas Aquinas. Due to the loss of importance of this virtue and its reduced artistic visualization (in comparison with other periods of art history), during the centuries in which the Virgin of Humility was predominant, it is possible to affirm that the latter replaced the allegory of Humility, which was subsequently personified by the figure of Mary. The connection between the ground, Humility, and the Virgin is clearly manifested in images of the tree of virtues, contributing to this substitution.

The growing devotion to the Mother of God, since the 12th and 13th centuries could contribute to this. The theologians highlighted the humility of the Virgin when she accepted the divine will, that was manifested in her womb and her breasts. Hence the references to the Annunciation in the type of the Virgin of Humility and her main representation as Virgo Lactans. However, there are still many aspects to study that would shed light on this question, such as the function of those images, in relation to the wide use of the visual representation of virtues.

Author Contributions

Investigation, M.E.M.M. and M.M.C.; Methodology, M.E.M.M. and M.M.C.; Writing—original draft, M.E.M.M. and M.M.C. All authors contributed equally to the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Generalitat Valenciana: Atracció del talent INV17-01-13-01; Conselleria de Innovación, Universidades, Ciencia y Sociedad Digital (Generalitat Valenciana): research project “Los tipos iconográficos conceptuales de María” GV/2021/123.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kathryn Rudy for her help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Other authors who have dedicated extensive studies to the representations of Psychomachia are: Woodruff (1930), Hinks (1939), Martin (1954), Cames (1971), McGuire (1990), Hourihane (2000), Willeke (2003), Parker (2009), Marchese (2013), Aavistland (2014). In addition, there are numerous articles on specific works that depict this type. |

| 2 | “Look at impurity knocked down by chastity, perfidy killed by good faith, cruelty defeated by mercy, pride defeated by humility: such are the contests in which we, Christians, receive crowns” (translated by the authors). |

| 3 | “and Humility prostrate on the ground and not fee herself to judge”. (Prudentius 1939, p. 19). Regarding the connection with the earth, the etymological relationship between humilitas (humility) and humus (earth), established later by Isidore in his Etymologies (c. 634), should be highlighted: “Humilis, quasi humo acclinis” (isid. orig. 10, 116; PL 82, 379). |

| 4 | “I, Humility, queen of the Virtues, say: come to me, you Virtues, and I’ll give you the skill to seek and find the drachma that is lost and to crown her who perseveres blissfully”. Translation: https://www.healthyhildegard.com/ordo-virtutum-text-translation (accessed on 14 June 2021). |

| 5 | “Humilitas est ex intuitu propriae conditionis vel conditoris, voluntaria mentis inclinatio. Ejus autem hi sunt comitatus principales: Prudentia, justitia, fortitudo, temperantia, fides, spes et charitas”. (Humility is the view of ones own qualification or its founder, by willing predisposition. And these are accompanied by: Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, Temperance, Faith, Hope and Charity) (Hugh of Saint Victor, De fructibus carnis et spiritus, cap. XI; PL 176, 1001) (translated by the authors). |

| 6 | “Tollite jugum meum super vos, et discite a me: non mundum fabricare, non cuncta visibilia et invisibilia creare, non in ipso mundo miracula facere, et mortuos suscitare; sed quoniam mitis sum et humilis corde. Magnus esse vis, a minimo incipe. Cogitas magnam fabricam construere celsitudinis, de fundamento prius cogita humilitatis. Et quantam quisque vult et disponit superimponere molem aedificii, quanto erit majus aedificium, tanto altius fodit fundamentum. Et fabrica quidem cum construitur, in superna consurgit: qui autem fodit fundamentum, ad ima deprimitur. Ergo et fabrica ante celsitudinem humiliatur, et fastigium post humiliationem erigitur” (Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, not to build the world, not to create the visible and invisible, not to do miracles in the world nor to raise the dead; rather, learn that I am gentle and humble at heart. Do you want to be great? Start with the smallest. Do you pretend to build a big and high building? First think about the foundation of humility. And the desired size of the building determines what someone wants to impose on the building; the higher it is, the deeper the foundations must be dug. When the building is built, it rises higher and higher; but the foundations must be dug deeper and deeper. Then, the building also humiliates itself before rising and after the humiliation, it rises.) (Avg. Serm. Ad Popul. Serm. 69, 2; PL 38,441) (translated by the authors). |

| 7 | “Ad secundum dicendum quod, sicut ordinate virtutum congregation per quondam similitudinem aedificio comparator, ita etiam illud quod est primum in acquisitione virtutum, fundamento comparator, quod primum in aedificio iacitur. Virtutes autem verae infunduntur a Deo. Unde primum in acquisitione virtutum potest accipi dupliciter. Uno modo, per modum removentis prohibens. Et sic humilitas primum locum tenet, inquantum scilicet expellit superviam, cui Deus resistit, et praebet hominem subditum et sempre patulum ad suscipiendum influxum divinae gratiae, inquantum evacuat inflationem superbiae; ut dicitur Iac. IV, quod Deus superbis resistit, humilibus autem dat gratiam. Et secundum hoc, humilitas dicitur spiritualis aedificii fundamentum” (Just as the orderly assembly of virtues is, by reason of a certain likeness, compared to a building, so again that which is the first step in the acquisition of virtue is likened to the foundation, which is first laid before he rest of the building. Now the virtues are in truth infused by God. Wherefore the first step in the acquisition of virtue may be understood in two ways. First by way of removing obstacles: and thus humility holds the first place, inasmuch as it expels pride, which “God resisteth”, and makes man submissive and ever open to receive the influx of Divine grace Hence it is written (James 4:6): “God resisteth the proud, and giveth grade to the humble”. In this sense humility is said to be the foundation of the spiritual edifice) (Aquinas 1225; S.Th. (45499) IIª-IIae, q. 161 a. 5 ad 2.). Translation: https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/04z/z_1225-1274__Thomas_Aquinas__Summa_Theologiae-Secunda_Secundae__EN.pdf.html (accessed on 15 June 2021). |

| 8 | “Puédese comparar la virtud de la humildad al cordero, que es el más humilde animal que sea en el mundo e sufre qualquiere cosa que le acaece sometiéndose a cada uno. E por esso es comparado en la Sagrada Scriptura al fijo de Dios, diciendo: ‘Agnus Dei qui tollis’”. (Jn. 1, 29). (The virtue of Humility is compared to a lamb, which is the humblest animal in the world, and it suffers anything that happens to it, submitting itself to each one. For these reasons, it is compared in the Holy Scripture to the son of God, as in the saying: ‘Agnus Dei qui tollis’) (Mateo Palacios 2013, p. 118) (translated by the authors). |

| 9 | “Omnes autem invicem humilitatem induite, quia Deus superbis resistit, humilibus autem dat gratiam” (All wrap yourselves in humility to be servants of each other, because God refuses the proud and will always favor the humble) (1 P 5,5). |

| 10 | “Ita etiam humilitas reprimit motum spei, qui est motus spiritus in magna tendentis. Et ideo, sicut mansuetudo ponitur pars temperantiae, ita etiam humilitas” (so does humility suppress the movement of hope, which is the movement of a spirit aiming at great things. Wherefore, like meekness, humility is accounted a part of temperance) (Aquinas 1225; S.Th. (45488) IIª-IIae, q. 161 a. 4 co.). Translation: https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/04z/z_1225-1274__Thomas_Aquinas__Summa_Theologiae-Secunda_Secundae__EN.pdf.html (accessed on 15 June 2021). |

| 11 | “Isidore says (De Summo Bono ii, 39) that ‘as pride of mind leads to the depravity of lust, so does humility of mind safeguard the chastity of the flesh’”. (Aquinas 1225) Translation: https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/04z/z_1225-1274__Thomas_Aquinas__Summa_Theologiae-Secunda_Secundae__EN.pdf.html (accessed on 21 June 2021). |

| 12 | “Mary’s heart never submitted itself to evil, but put itself in the service of God and kept humbly its saintly virginity” (translated by the authors). |

| 13 | Although the presence of the twelve apostles at both sides refers to Pentecost. |

| 14 | Under it there is an image of a confraternity with disciplinanti on both sides of the arma Christi, as in the work of Giovanni da Bologna, venerated by the confratelli of the Scuola di San Giovanni Evangelista of Venezia (Figure 6b). The first one comes from a Franciscan church, San Francesco d’Assisi in Palermo, like others works with the Virgin of Humility. However, there are perhaps more images coming from the Dominican sphere, such as that by the Maestro delle Tempere francescane (Figure 5a) or that by Roberto d’Oderisio, both from the Neapolitan church of San Domenico Maggiore. The latter was originally associated with a tomb. Also the fresco of Avignon (Figure 4) had a funerary character, because the cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi, recently deceased, has been depicted next to Mary. We can assume that this type was mostly associated with a funerary context and the mendicant orders, but this question requires a further investigation. However, if we consider the Virgin of Humility as an allegory of this virtue, it would be logical for this type to have a wide variety of uses, like the visual representation of the rest of the virtues. |

| 15 | It has been mistranslated on the museum website as “Holy Mary, the milk of God”. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1963.500 (accessed on 22 September 2021). |

| 16 | See note 3. |

| 17 | “As Isidore observes (Etym. x), ‘a humble man is so called because he is, as it were, humo acclinis’, i.e., inclined to the lowest place” (Aquinas 1225) Translation: https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/04z/z_1225-1274__Thomas_Aquinas__Summa_Theologiae-Secunda_Secundae__EN.pdf.html (accessed on 21 June 2021). |

| 18 | “having produced in advance the herb of holy thoughts, affections, words and actions” (translated by the authors). |

| 19 | “land of fertile fecundity” (translated by the authors). |

| 20 | “is a flower of the field, not of the garden (Ct 2,1). The field blooms without human intervention. No one sows it, no one digs it, no one fertilizes it. In the same way the Virgin’s womb flourished. The womb of Mary, without blemish, whole and pure, like meadows of eternal greenness, illuminated that flower, whose beauty does not feel corruption, nor does its glory ever fades” (translated by the authors). |

| 21 | “land not worked by man” (translated by the authors). |

| 22 | “the hand on the breast shows that the heart is the place where true humility resides” (translated by the authors). |

| 23 | “the opened right hand is a sign that humility should be true and patient” (translated by the authors). |

| 24 | “Donna con la sinistra mano al petto, e con la destra distesa, & aperta; sarà la faccia volta verso il Cielo, & con un piede calchi una vipera mesa morta, avuitichiata intorno à un specchio tutto rotto, e spezzato, & con una testa di leone ferito pur sotto à piedi” (Woman with her left hand on her breast and with her right hand opened. She turns her face to the sky, while one of her feet steps on a snake, almost dead and coiled around a broken mirror. At her feet will be the head of an injured lion) (Ripa 1603, p. 214) (translated by the authors). |

| 25 | “Si dipinge donna vestita di bianco, perche si conozca che la candidezza, & purità della mente partorisce nell’huomo ben disposto, & ordinato allá ragione, quella humiltà che è bastevole à rendere l’attioni sue pipacevoli à Dio, che da la sua à gl’humili, & fa resistenza allá voluntà de’superbi” (A woman wearing white is painted, which means candor and purity of mind. It makes man good and orderly according to reason, the kind of humility which is enough to make actions most deserving and pleasing to God because it gives grace to the humble and it resists to proud’s will.) (Ripa 1603, p. 214) (translated by the authors). |

| 26 | “L’agnello è il vero ritratto dell’huomo mansueto, & humile, per questa cagione Christo Signor nostro è detto agnello in molti luoghi, e dello Evangelio, & de Profeti” (The lamb is the symbol and true portrait of the gentle and humble man. For this reason, Christ was named the Lamb in many places, both in the Gospels and in the Books of the Prophets.) (Ripa 1603, p. 214) (translated by the authors). |

| 27 | “Ciò si mostra con la presente figura, che potendosi vestiré ricamente s’elegge il sacco” (This presents a figure that can wear rich clothes, but chooses a sack.) (Ripa 1603, p. 214) (translated by the authors). |

| 28 | “il pane è indicio che si procura míseramente il vitto, senza esquisitezza di molte delicature, per riputarsi indegna de i commodi di questa vita” (Bread is an indication that their food is poorly procured, without falling into delicacies, because they consider themselves unworthy of the luxuries and comforts that this life provides.) (Ripa 1603, p. 214) (translated by the authors). |

| 29 | “Il sacchetto che aggrava è la memoria de’peccati, ch’abbassa lo spirto de gl’humili” (The sack that manifestly weighs on her indicates the memory of her own sins, which oppress the spirit of humble persons.) (Ripa 1603, p. 214) (translated by the authors). |

| 30 | “L’humiltà debe esser una volontaria bassezza di pensieri di se stesso per amor di Dio, dispregiando l’utili, e l’honori” (Humility consists of the willingness to lower one’s self-esteem for the love of God and despising Fortune’s honors and goods.) (Ripa 1603, p. 214) (translated by the authors). |

| 31 | “Woman wearing brown with her arms crossed on her breast, holding a ball in one hand and a headband on her neck, looking under her right foot a golden crown.” (translated by the authors). |

| 32 | “Il tener la corona d’oro sotto il piede, dimostra, che l’humiltà non pregia le grandezze, e richezze, anzi è dispregio d’esse” (The crown underfoot shows that true humility places no value on the greatness of this world or on its exterior signs.) (Ripa 1603, pp. 215–6). |

References

- Aavistland, Kristin B. 2014. Noen refleksjoner omkring dyder og laster, kvinnelig og mannlig i middelalderens ikonografi (Some reflections on virtues and vices, female and male in medieval iconography). ICO: Iconographisk Post: nordisk tidskrift förbildtolkning 3: 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Saint Thomas. 1225. Summa Theologiae (Summary of Theology). Available online: https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/04z/z_1225-1274__Thomas_Aquinas__Summa_Theologiae-Secunda_Secundae__EN.pdf.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Barbier, Xavier. 1898. Traité d’iconographie chrétienne. (Treatise on Christian Iconography). Paris: Societé de libraire ecclésiastique et religeuse. [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi, Marie-Odile. 2010. Les Vertus dans la France baroque: représentations iconographiques et littéraires. (Virtues in baroque France: Iconographic and Literary Representations). Paris: Honoré Champion. [Google Scholar]

- Cames, Gérard. 1971. Allégories et symboles dans l’hortus deliciarum. (Allegories and symbols in the hortus deliciarum). Leiden: E. J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Cosnet, Bertrand. 2015. Sous le regard des vertus Italie, XIVe siècle. (Under the Gaze of the Virtues Italy, 14th Century). Tours: Presses universitaires François-Rabelais. [Google Scholar]

- García Mahíques, Rafael. 1995. Perfiles iconográficos de la Mujer del Apocalipsis como símbolo mariano (I). Sicut mulier amicta sole et luna sub pedibus eius (Iconographic profiles of the Woman of the Apocalypse as a Marian symbol (I). Sicut mulier amicta sole et luna sub pedibus eius). Ars longa 6: 187–97. [Google Scholar]

- Grosseteste, Robert. 1918. Chateau d’amour. (The Castle of Love). Paris: Libraire Champion. [Google Scholar]

- Hildegard of Bingen. 1151. Ordo Virtutum. (Order of the Virtues). Turnhout: Brepols, Available online: https://www.healthyhildegard.com/ordo-virtutum-text-translation (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Hinks, Roger. 1939. Myth and Allegory in Ancient Art. London: The Warburg Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Houlet, Jacques. 1969. Les combats des vertus et des vices: Les psychomachies dans l’art. (The Battles of Virtues and Vices: Psychomachia in Art). Paris: Nouvelles Éditions Latines. [Google Scholar]

- Hourihane, Colum. 2000. Virtue & Vice: The Personifications in the Index of Christian Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katzenellenbogen, Adolf. 1939. Allegories of the Virtues and Vices in Mediaeval Art: From Early Christian Times to the Thirteenth Century. Nedeln, Lichtenstein: Kraus Reprint. [Google Scholar]

- King, Georgiana Goddard. 1935. The Virgin of Humility. The Art Bulletin 17: 474–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, Engelbert. 1971. Lexikon der Christlichen Ikonographie. (Dictionary of Christian Iconography). Roma, Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Levi d’Ancona, Mirella. 1977. The Garden of the Renaissance. Botanical Symbolism in Italian Painting. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Mâle, Émile. 1925. L’Art religieux de la fin du moyen age en France: étude sur l’iconographie du moyen age et sur ses sources d’inspiration. (Religious art in France: The late Middle Ages: A study of medieval iconography and its sources). Paris: Armand Colin. [Google Scholar]

- Mâle, Émile. 1986. El gótico: la iconografía de la Edad Media y sus fuentes. (Religious art in France: The thirteenth century: A study of medieval iconography and its sources). Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- Marchese, Francis. 2013. Virtues and Vices: Examples of Medieval Knowledge Visualization. In 17th International Conference on Information Visualisation. Edited by IEEE Computer Society. Los Alamitos: IEEE Computer Society, pp. 359–65. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, John R. 1954. The Illustration of the Heavenly Ladder of John Climacus. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo Palacios, Ana, ed. 2013. Flor de Virtudes. (Flower of Virtues). Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Thèrese B. 1990. Psychomachia: A Battle of the Virtues and Vices in Herrad of Landsberg’s Miniatures. Fifteenth-Century Studies 16: 189–97. [Google Scholar]

- Meiss, Millard. 1936. The Madonna of Humility. Art Bulletin 18: 435–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, Juan de. 1912. Coplas que fizo el famoso Juan de Mena contra los pecados mortales (Coplas made by the famous Juan de Mena against mortal sins). In Cancionero castellano del siglo XV. (Castilian Songbook of the fifteenth century). Edited by Raymond Foulché-Delbosc. Madrid: Bailly-Bailliére. [Google Scholar]

- Mocholí Martínez, María Elvira. 2017. Las imágenes conceptuales de María en la escultura valenciana medieval (The conceptual images of Mary in medieval Valencian sculpture). Ph.D Thesis, Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain. Available online: https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/mostrarRef.do?ref=1347579 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Mocholí Martínez, María Elvira. 2019. In altum mittis radices humilitatis. Un estudio de las imágenes de María en contacto con la naturaleza (In altum mittis radices humilitatis. A study of the images of Mary in contact with nature). De Medio Aevo 13: 119–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos Castañeda, María. 2019. La visualidad de las Virtudes Cardinales. (The Visual Representation of the Cardinal Virtues). Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain. Available online: https://roderic.uv.es/handle/10550/75437 (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Norman, Joanne S. 1998. Metamorphoses of an Allegory: The Iconography of the Psychomachia in Medieval Art. New York: Lang. [Google Scholar]

- North, Helen F. 1979. From Myth to Icon: Reflections of Greek Ethical Doctrine in Literature and Art. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, Jennifer. 1988. Studies in the Iconography of the Virtues and Vices in the Middle Ages. New York: Garland Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Sarah. 2009. Female Agency and the Disputatio Tradition in the Hortus Deliciarum. Master’s Thesis, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Polzer, Joseph. 2000. Concerning the Origin of the Madonna of Humility. RACAR. Revue d’art Canadienne/Canadian Art Review 27: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudentius, Aurelius. 1939. The Psychomachia of Prudentius. Raleigh: Meredith College. [Google Scholar]

- Réau, Louis. 1996. Iconografía del Arte Cristiano. Nuevo Testamento. (Iconography of the Christian Art. New Testament). Barcelona: Serbal, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ripa, Cesare. 1603. Iconologia. (Iconology). Roma: Lepido Faeij. [Google Scholar]

- Ripa, Cesare. 2007. Iconología. (Iconology). Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Sallay, Dóra. 2012. The Avignon Type of the Virgin of Humility. Examples in Siena. In Geest en gratie. Essays Presented to Ildikó Ember on Her Seventieth Birthday. Edited by O. Radványi. Budapest: Szépművészeti Múzeum, pp. 104–11. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Paz, José C., ed. 1999. O desfile das virtudes. Ordo Virtutum de Hildegarde de Bingen. (The Parade of the Virtues. Order of the Virtues of Hildegard of Bingen). A Coruña: Universidade da Coruña. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián, Santiago. 1988. Iconografia medieval. (Medieval Iconography). Donostia: Etor. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián, Santiago. 1994. Mensaje simbólico del arte medieval: arquitectura, liturgia e iconografía. (Symbolic Message of Medieval Art: Architecture, Liturgy and Iconography). Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, Clare Marie. 2012. Maria Mediatrix: Mediating the Divine in the Devotional Literature of Late Medieval England. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Trens, Manuel. 1946. Maria. Iconografía de la Virgen en el arte español. (Maria. Iconography of the Virgin in Spanish Art). Madrid: Plus Ultra. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, Shawn R. 2015. The Virtues and Vices in the Arts. Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuve, Rosemund. 1963. Notes on the Virtues and Vices 1: Two Fifteenth-century Lines of Dependence on Thirteenth and Twelfth Centuries. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 26: 264–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuve, Rosemund. 1977. Allegorical Imagery: Some Mediaeval Books and Their Posterity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Marle, Raimond. 1971. Iconographie de l’art profane au Moyen-Age et à la Renaissance et la décoration des demeures. (Iconography of Secular Art in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and the Decoration of Mansions). New York: Hacker Art Books. [Google Scholar]

- Van Os, Henk. 1969. Marias Demut und Verherrlichung in der sienesischen Malerei, 1300–1450. (Mary’s Humility and Glorification in Sienese Painting). Den Haag: Staatsuitgeverij. [Google Scholar]

- Willeke, Heike. 2003. Ordo und Ethos im Hortus Deliciarum. Das Bild-Text-Programm des Hohenburger Codex zwischen kontemplativ-spekulativer Weltschau und konkret-pragmatischer Handlungsorientierung. (Ordo and Ethos at Hortus Deliciarum. The Image-Text-Program of the Hohenburger Codex between contemplative-speculative World Vision and concrete-pragmatic Action Orientation). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Beth. 2007. Site, Seeing and Salvation in Fourteenth-Century Avignon. Art History 30: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Beth. 2009. The Madonna of Humility. Development, Dissemination and Reception, c. 1340–1400. Woodbridge: The Boydel Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff, Helen. 1930. The Illustrated Manuscripts of Prudentius. Art Studies 7: 33–79. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).