Engraving and Religious Imagery in the Modern Age: Between Verisimilitude and the Suggestion of Non-Existent Realities. Analysis of Some Cases Elaborated in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Developing

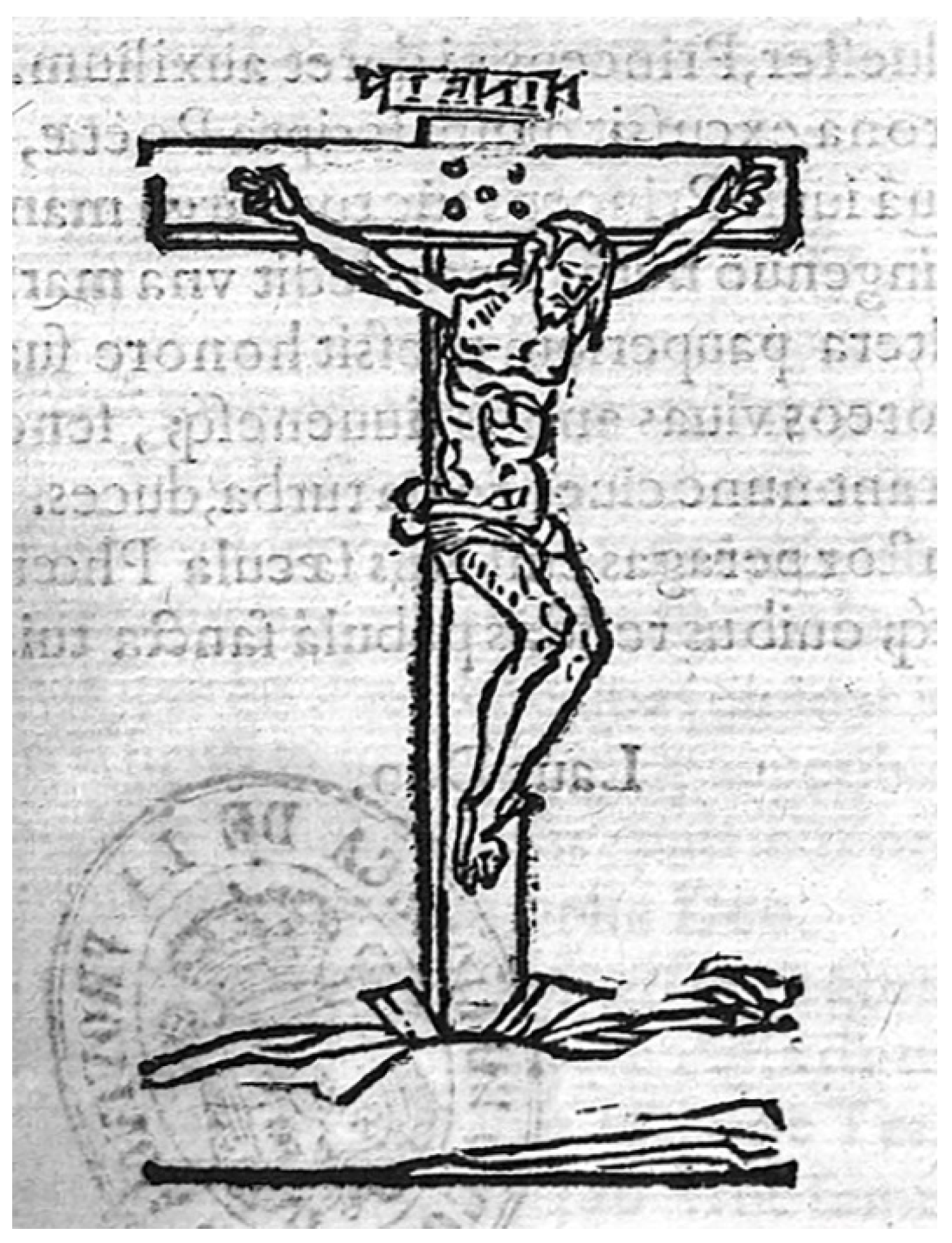

2.1. About the Image of Christ

2.2. About the Image of a Saint: St. John of God

2.3. About the Image of the Final Judgment

2.4. About the Image of the King and the Pope

2.5. About the Image of the Martyrs: Alonso Navarrete and Alonso Mena, Martyrs of Japan

2.6. About the Image of the Purgatory

3. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Quando iva a la visita del Alpujarra iva cargado de Rosarios, pilas de agua bendita y imágenes de papel para repartir entre los Moriscos. Enseñavales la reverencia con que se han de tener, y como en ellas no se adora la pintura, sino lo representado en ella”. (Bermúdez de Pedraza 1638, p. 187). * Translation of old Spanish: “When he went to visit the Alpujarra he was loaded with Rosaries, piles of holy water and paper images to distribute among the Moriscos. He taught them the respect they should have for them, and how the painting is not worshiped, but what is represented in them”. |

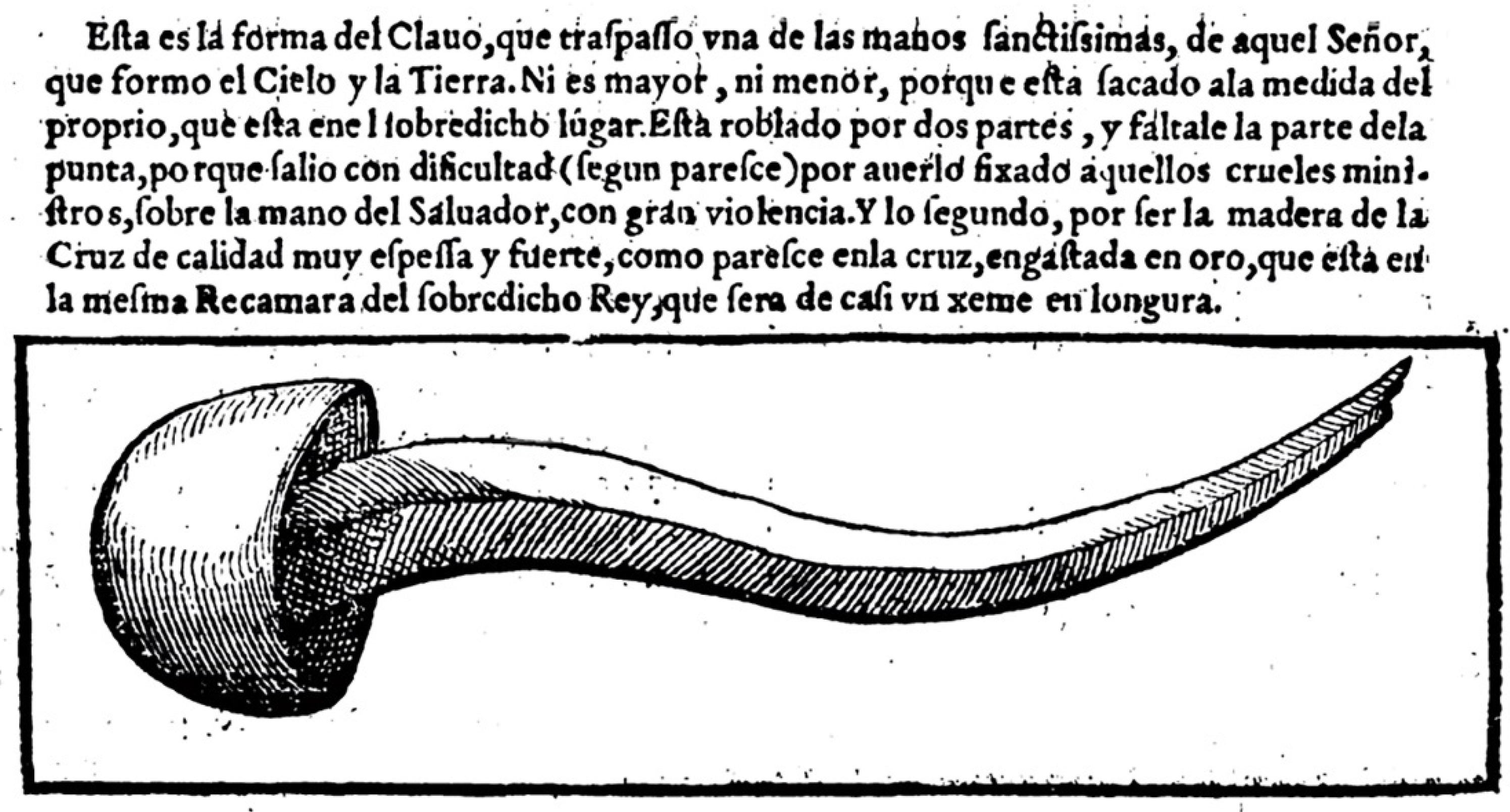

| 2 | Recall the famous engraving he includes in his Christian Rhetoric (Perugia, 1579) in which the priest, from the pulpit, preaches while pointing at a series of images of the Passion of Christ, spread out within reach and visible to all, mostly indigenous people. He is referred to in the quotation. |

| 3 | * Translation of old Spanish: “If … I had …. Twenty or thirty thousand holy cards, all of them will be used, because each one will take a holy card to his own room.” |

| 4 | This is the text referred to: Libro de la Primera parte, de la excelencia del Sancto Evangelio, en que se contiene un breve Compendio, de los Mysterios de la venida de IESUCHRISTO nuestro Señor al mundo. Con las calidades y condiciones que pertenecen a este tan alto Sacramento de la Encarnación, y de la reparación de la culpa general. Contiene se principalmente en este libro, todo el discurso hystorial, de cada uno de los misterios, de la ultima y soberana Cena, que CHRISTO celebro: y los de su muy sancta Muerte y Passion. Con las circunstancias y claridad, de cada una destas obras, en que la Magestad del muy alto Señor (tan señaladamente) puso la mano. Dispuesto y dividido en quatro libros, para mayor claridad de esta historia. Con un breve y compendioso tractado, de los Mysterios que succedieron, desde que CHRISTO espiro en la Cruz, hasta que en cuerpo glorioso, y familiarmente, apareció à la gloriosa Virgen su madre, y a todos los otros Apóstoles y Discípulos (que por dispensación Divina) fueron elegidos, para ser testigos idóneos, destos tan altos Mysterios, después que rescibieron la investidura de la predicación del sancto Evangelio. Ahora nuevamente collegido, de los Originales de las scripturas Sanctas de ambos Testamentos. Y de los libros de los mas antiguos y escogidos Doctores de yrrefragable autoridad, que desta materia tractan. Dirigido à la Serenissima, muy Alta y muy Poderosa señora doña IVANA, Princesa de Portugal, primera deste nombre. Por el muy Reverendo Padre Fray PHILIPPE DE SOSA, Predicador (de la orden de los Frayles Menores, de Observancia, del glorioso padre sant Francisco) de la Provincia del Andaluzia. En Sevilla. En casa de Juan Gutierrez impressor de libros. 1569. Con Privilegio Real de Castilla. |

| 5 | For these types of aspects and the representation of the visage of Christ in the different periods, see Labarga (2016, pp. 265–316). |

| 6 | It is the canon defended by Vitruvius, 1st cent. BC, in his work Los diez libros de arquitectura (Ten books on architecture), (Vitruvio 1991, p. 68). In Spain, the author of the first theoretical text on this classical language, Diego de Sagredo (Medidas del Romano, Toledo, 1526), reflects this canon in a drawing of a proportional head dating from 1541. See: Sagredo ([1526] 1986, plate 10). |

| 7 | It should be remembered that since the beginning of Christianity there have been advocates of beauty (St. John Chrysostom, St. Jerome, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, St. John of Damascus, Theodoret of Cyrus, Epiphanius of Salamis…) who confront those who defend the ugliness of Christ (St. Justin, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Tertullian…). The concept of the beautiful visage will triumph: “The choice of the physical beauty of Christ is best suited to theological reflection, which has a strong philosophical background, according to which the transcendentals are interchangeable; therefore, if we know that Christ is the supreme perfection, the supreme truth and the supreme good, then the supreme beauty also logically corresponds to him”. This aspect was accentuated in the Renaissance with the appreciation of the classical aesthetic canon, which based beauty on proportion and was translated into the body of Christ. For these aspects, see Labarga (2016, pp. 274–75, 296). |

| 8 | It should be remembered that these character peculiarities are assigned on the basis of the resemblance of the characteristics indicated to those of a certain animal, bearing in mind that, in this animal, specific behavioral characteristics are also pointed out; this is the starting point of physiognomy. |

| 9 | Essentially Pseudo Aristotle and Adamantius. (Defradas and Klein 1989, pp. 136–88). |

| 10 | “Physiognomy is a form of observation by which we can get to know the qualities of souls from their bodily features… this rule is reversible… we can… imagine the appearance of the dead by taking their well-known moral characteristics as a guide” (Gaurico [1504] 1989, p. 158). |

| 11 | * Translation of old Spanish: “And as his divine heart began to be occupied by sadness to an excessive degree, he said to the three aforementioned disciples: Sad is my soul until death… He suffered truly and not feignedly in this place, so that in the centuries to come there would be a memory of that due sentiment, of his sacred passion… Truly he became tired, truly he was hungry… truly he shed copious tears and was saddened, as it seems in this place of the garden of Gethsemane.” |

| 12 | * Translation of old Spanish: “In the human nature of this fair man, there is not only union with the divine nature, but all that the grown understanding can see in a state of perfection… And as for the external and visible form, this man exceeds God… and is preferred to all men”. |

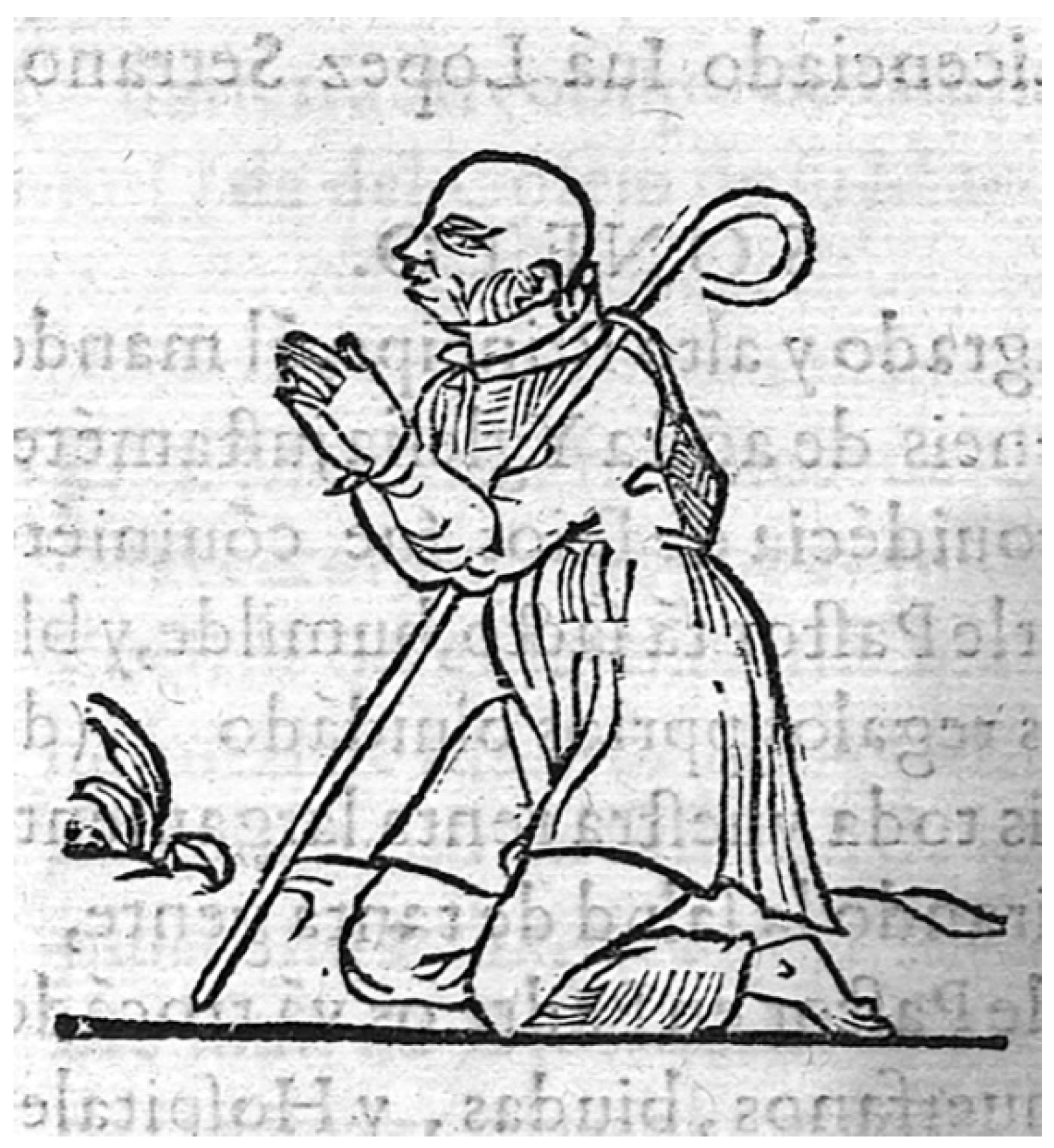

| 13 | * Translation of old Spanish: “beautiful in appearance and bodily form”. |

| 14 | * Translation of old Spanish: “the pain that went through the souls of these holy men [when He was taken down from the cross], remembering the beauty with which they saw that divine visage and that grace and authority… distributing… gifts… of all health and consolation”. |

| 15 | * Translation of old Spanish: “So that the devotion of the pious reader may be incited; and kindled with greater fervor… we place here the actual form and figure of one of those nails with which the holy and sovereign lord was affixed to the cross”. |

| 16 | The image of the nail is accompanied by this clarification: “Esta es la forma del Clavo, que traspasso una de las manos sanctissimas, de aquel Señor, que formo el Cielo y la Tierra. Ni es mayor, ni menor, porque esta sacado a la medida del propio, que esta en el sobredicho lugar. Esta roblado por dos partes, y faltale la parte de la punta, porque salió con dificultad (según paresce) por averlo fixado aquellos crueles ministros, sobre la mano del Salvador, con gran violencia. Y lo segundo, por ser la madera de la Cruz de calidad muy espessa y fuerte, como paresce en la cruz, engastada en oro, que esta en la mesma Recamara del sobredicho Rey, que sera de casi un xeme en longura” (un xeme o jeme equivale a la medida de un palmo).Y en el texto se dice: “Este clavo, y admirable reliquia, tiene el Rey don Philippe, segundo deste nombre, Rey de las Españas, entre otras reliquias de grande estimación. Esta al pie de una flor de Lis de oro, debaxo de un viril, con que esta cubierto, la qual en oro, y piedras es de gran valor”. “Este clavo esta roblado por dos partes contrarias y paresce en una esquina del, la señal que hizo el instrumento común de hierro con que lo sacaron… la cabeça del clavo… es ancha, profunda y redonda… la madera de la cruz paresce ser condensa… Por esta causa salieron los clavos como paresce … con trabajo, y alla dentro del madero se quedo parte de la punta deste” (Sosa 1569, pp. 121 y 167). Translation of old Spanish: “This is the form of the Nail, which pierced one of the holy hands of the Lord, who formed Heaven and Earth. It is neither larger nor smaller, because it is taken to the measure of its original, which is in the aforementioned place. It is riveted in two parts, and lacks the part of the tip, because it came out with difficulty (as it seems) for having been fixed by those cruel ministers, on the hand of the Savior, with great violence. And secondly, because the wood of the Cross is of a very thick and strong quality, as it appears in the cross, set in gold, which is in the same Chamber of the aforementioned King, which will be almost a palm in length”. In the text, it is said: “This nail, and admirable relic, is owned by King Philippe, the second of this name, King of Spain, among other relics of great value”. “It is at the foot of a golden fleur de lis, under a glass that covers it, with gold and stones of great value”. “This nail is riveted on two opposite sides and it appears in one corner of it, the mark made by the common iron instrument with which it was removed… the nail’s head… is wide, deep and round… the wood of the cross appears to be thick… For this reason the nails came out as it seems… with labour, and part of the tip of the nail remained inside the wood”. |

| 17 | TV ES CRISTVS FILIVS DEI VIVI QVI IN HVNC MVUNDVM VENISTI: “You are Christ the Son of the living God who came into this world”. IHS XPS SALVATOR MVNDI: “Jesus Christ, Savior of the world”. |

| 18 | * Translation of old Spanish: “But in the resurrection… remaining in the same substance of human nature, [this substance] was surrounded with gifts and great gifts of glory, of impassibility, of subtlety, of lightness and clarity… the clarity which consists in the beauty of perfect color, and in a radiance brighter than sunlight.” |

| 19 | Formula whose roots go back to Classical Antiquity, profuse in the Roman representation and extended by the influence of this in the Renaissance, for portraits of illustrious personages. |

| 20 | For a complete study of books of this type of texts and images, see Zafra (2014, pp. 129–43). |

| 21 | Its author, Medina, quotes and collects Sosa’s arguments throughout his book, even reproducing his engraving of the nail of the crucified hand of Christ, a relic of Philip II of Spain (Primer Libro, p. 370). The book in question is Victoria gloriosa, /y excelencias de la/esclarecida Cruz de Iesu Chri/sto nuestro Señor./por el M. F. Pedro de Medina de la Or/den de N. S. de la Merced Redempcion de Captivos./Dispuestas en tres Libros./Dirigidos a N. Reverendo P. F. Alonso de/Monrroy, dignissimo Maestro General de toda la misma Orden. Año 1604. Con privilegio. En Granada, por Fernando Diaz de Montoya. Esta Tassado a tres maravedís y medio el pliego. It is the canon defended by Vitruvius in the 1st century BC (Vitruvio 1991, p. 68), highlighted by Renaissance classicism, to which Pedro de Medina refers (de Medina 1604, Libro Primero, p. 365). |

| 22 | * Translation of old Spanish: “Christ, which was at least six to seven feet long, being the most common state of a perfect man.” |

| 23 | * Translation of old Spanish: “That the holy body of Christ at the moment of his conception was organized and perfectly adapted for the holy and blessed anima which God infused in him… just as the Holy Spirit created a human body in that ineffable [Virgin], the most perfect of all that can be thought of, according to the perfection of the holy soul that had to inform everything to the hypostatic union of the Word with the same humanity, and also because the Word, human and passive, was to be placed, nailed and died on a Cross, it was agreed and it was so, that the Holy Spirit himself, with particular providence, drew it and ordered it to be of the matter and form that it was, in order and for the manifestation of the goodness of God”. |

| 24 | * Translation of old Spanish: “On the cross of the Lord there were four pieces of lumber, which are the right mast, the transverse lumber, the trunk placed at the foot [to fix the cross firmly to the ground] and the title above… In addition to this, there was also a wooden block nailed to the Cross under the feet of the Redeemer, where he had them nailed”. |

| 25 | * Translation of old Spanish: “The form and shape of this serpent… was in accordance with the form and shape of the living ones… in imitation of those that kill men… it had the color of the living serpents. It was crucified on the pole… Moses, by the command of God, made a form of a bronze cross and raised it upright near the tabernacle… For greater interrelationship between the figure, that was the serpent, with the figurative, that is Christ, it should be considered… that that serpent… had its two wings as the living ones had them… it had the wings stretched out and in the shape of a Cross… that pole raised by divine order was a Cross… … And all who… looked upon it, were saved in life and healed in wounds… We wanted the story to be understood, that the spirit of the figure is related to that of the Cross of the Savior of the world”. |

| 26 | M. Gómez-Moreno: “Wood engraving, already printed in 1579, at the foot of the Spanish translation of the bull of Pius V”, Primicias Históricas de San Juan de Dios, Provincias Españolas de la Orden Hospitalaria, Madrid (Gómez-Moreno 1950, p. 6). |

| 27 | We do not know the printing house from which this translated text of the bull came out. |

| 28 | As for his poor clothing, only “by virtue of the ordinations of 1571 and 1585 the Brothers Hospitallers wore … [full-length habit]”. (Gómez-Moreno 1950, p. 327). |

| 29 | This is recorded by his first biographer, Francisco de Castro, who knew him and who echoes those who remember his physical appearance, always emphasizing the poverty of his clothing and his shaven appearance. See: (de Castro [1585] 1588, p. 59 for this quote and pp. 18 vo., 29, and 59 for the description of all his humble clothing). * Translation of old Spanish: “razor shaved, beard and head”. |

| 30 | To this day, they are kept in urns in the house-museum where he died. |

| 31 | The book referred to is Francisco de Castro: Historia de la vida y sanctas obras de Iuan de Dios, y de la institución de su orden, y principio de su hospital… En Granada, en casa de Antonio de Librixa. Año de M.D.LXXXV. |

| 32 | Since Castro includes the Spanish translation of the Bull Licet ex debito, he also includes the engraving, on a double page and unnumbered, between two laudatory poems and the dedication of the book. |

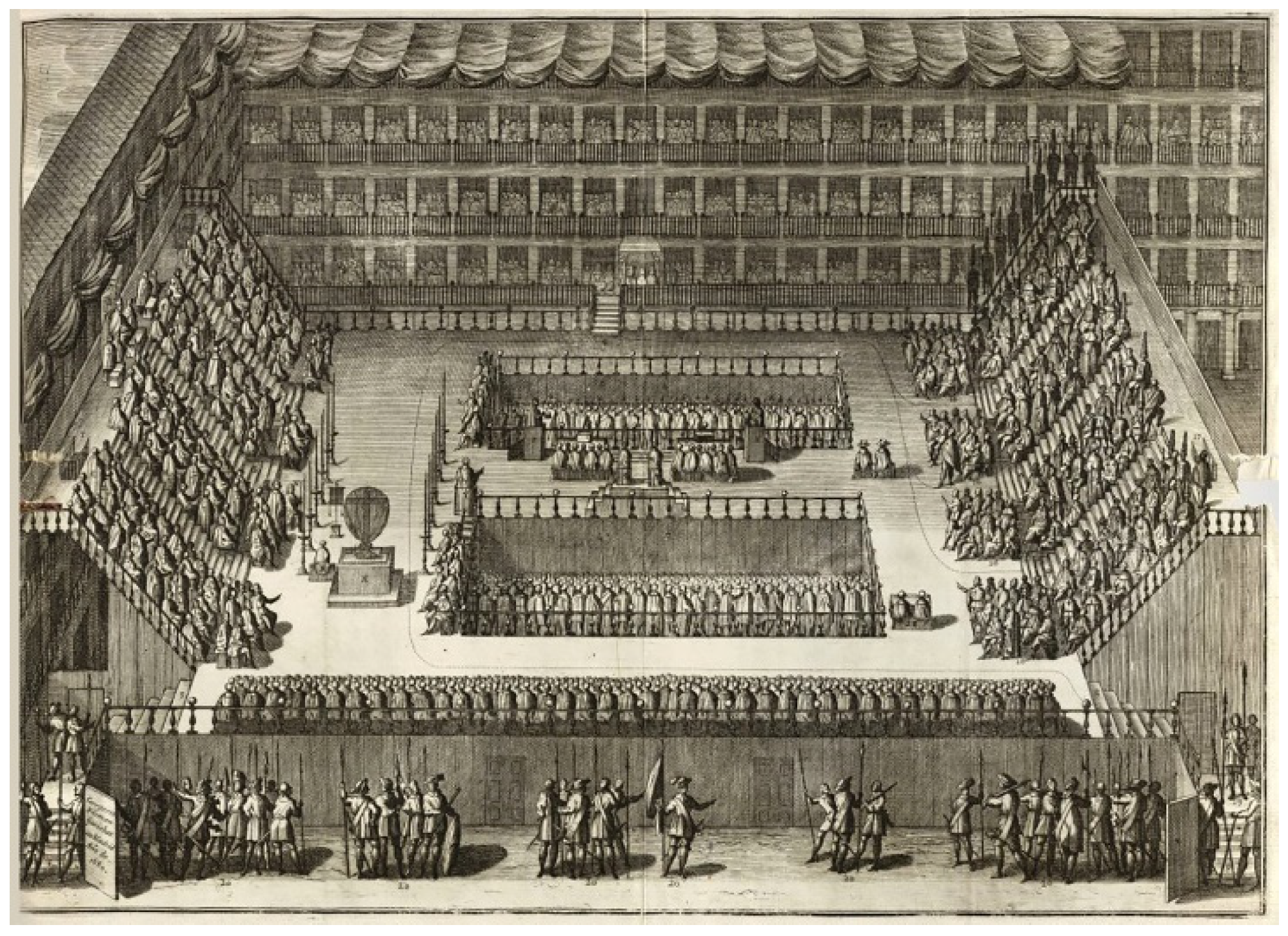

| 33 | The book referred to is Historia de la vida y sanctas obras de Juan de Dios, y de la institución de su orden, y principio de su hospital. Composed by Master Francisco de Castro, Priest Rector of the same Hospital of Juan de Dios in Granada. Con privilegio. En Granada en casa de Rene Rabut. (de Castro [1585] 1588). |

| 34 | It is a small bust in which the face appears from the front, bearded, with hair extending over the shoulders and nape of the neck, and with the denotative powers of sanctity radiating in triangular form, on the sides and top of the head. |

| 35 | “Estando Ioan de Dios comiendo un día con un Obispo de Tui (que en aquel tiempo se hallo en Granada) le pregunto que como se llama? El le dixo que Ioan, y el Obispo le respondió que se llamasse Ioan de Dios, el respondió, Si Dios quissiere” (de Castro [1585] 1588, p. 60 vo.). * Translation of old Spanish: “When John of God was eating one day with a Bishop of Tui (who at that time was in Granada), he asked him: what his name is? He told him that his name was John, and the Bishop replied that his name was John of God, and he answered, “If God willed it”.” |

| 36 | According to Friar Hierónimo Román (in his Republicas del Mundo, Medina del Campo (Román 1575), Libro VI, cap. XXVII, fol. 318). This quotation being collected by Gómez-Moreno (1950, p. 168). * Translation of old Spanish: “These who are called Johns of God, who walk with sacks and barefoot and on their backs with sacks and baskets, demanding alms to support hospitals and orphan children… In 1378… in Cremona… In our time it began in Granada by a saintly man called John of God, from which all were later called… Johns of God… |

| 37 | Bulas apostólicas concedidas por la santidad de Pio V y de Gregorio XIII y Sixto V a los Hermanos de la orden y Hospitalidad de Juan de Dios, las quales valen en España, y en las Indias, y en todas las demás partes donde estuvieren los Hermanos de la dicha Hospitalidad. Impressas en Madrid, con licencia del real Consejo de las Indias y del Comissario general de la santa Cruzada, en casa de P. Madrigal. (Popes et al. 1596). |

| 38 | IN MANUS TUAS DOMINE: “In your hands, Lord”. |

| 39 | “Pues sintiendo en si que se llegava su partida, se levanto de la cama, y se puso en el suelo de rodillas, abraçandose con un Crucifixo, donde estuvo un poco callando, y de ay a un poco dixo Iesus, Iesus, en tus manos me encomiendo, y diziendo esto con voz rezia y bien inteligible dio el alma a su Criador” (de Castro [1585] 1588, pp. 77 r. y 77 vo.). * Translation of old Spanish: “Then, feeling that his departure was approaching, he got up from his bed, and knelt on the floor, embracing a Crucifixion, where he remained silent for a while, and from there he said Jesus, Jesus, into your hands I commend myself, and saying this with a prayerful and well intelligible voice, he gave his soul to his Creator”. |

| 40 | S. IVº. DE DIOS: St. John (Ivan) of God. |

| 41 | For these dates and the chronological development of the process, see (Martínez-Rojas 2009, pp. 557–65, here: p. 559). |

| 42 | On the iconography of St. John of God in 17th century religious cards, see: (Moreno 1979, pp. 473–78). |

| 43 | M. Gómez-Moreno quotes as follows: “Holy card printed in Rome with privilege of Sixtus V in 1599. Title: B. Ioannes Dei lusitanus fundator Religionis fratrum curantium infirmos… Below: Romae Jacobus Laurus sculptor. Cum privilegio summi Pontificis ad decenium. Finally, the coat of arms of Sixtus V”. (Gómez-Moreno 1950, p. 170). This author includes such holy card in his book, in an unpaginated plate, between pp. 176 and 177. Note the authorship of the engraver. |

| 44 | Quote from a witness compiled by García-Melero (2017, p. 299). * Translation of old Spanish: “medals in which the blessed father John of God is placed and depicted as he was when he died”. |

| 45 | Autor and work are Práctica de los Ejercicios espirituales de Nuestro Padre San Ignacio por el Padre Sebastián Izquierdo de la Compañía de Jesús. En Roma por el Varese. 1675. Con licencia de los Superiores. |

| 46 | * Translation of old Spanish: “It is thought … that Christo our Lord on the last day of the world will come down from Heaven to earth, to judge the living and the dead with a universal Judgment… The circumstances of that last Judgment must be such… that it is of great importance to all of us to consider them with frequent and attentive consideration, to which this Exercise is ordered.” |

| 47 | * Translation of old Spanish: “The composition of place [will be] to imagine a very large Theater, in which a general Act of Inquisition is held.” |

| 48 | * Translation of old Spanish: “the Sun and the Moon will be darkened. The stars will fall from Heaven… In the Air there will be terrible storms… The sea will roar… going out of its limits… The earth will suffer… earthquakes… God will send that fire… with which will be covered… this globe of the World.” |

| 49 | * Translation of Old Spanish: “The heavens will open and the Son of God will come down with great power and might, accompanied by all his Angels… vibrating the sword of his Justice with the arm of his Omnipotence… as a rigorous Judge”. |

| 50 | * Translation of old Spanish: “he comes close to the earth and placed at a due distance, he will sit his Tribunal on a white cloud… placing at his right hand his Holy Mother, the Virgin Mary, and at his left hand the Apostles and other Apostolic men… so that they may be his Assessors, helping him to judge the others… Then those Books will be opened… in which will be seen written all the works of men, good and bad… which by Divine virtue will be made evident there, and all will clearly see all the good and bad works… their own and those of the others. What a strange affront, dishonor and confusion the wicked will suffer when they see there all their hidden sins made manifest to everyone.” |

| 51 | “Relaxar” means the act of handing over a death penalty condemned person from the ecclesiastical judge to the secular one. * Translation of old Spanish: “As here the Inquisition hands over the condemned person to the secular arm, the wretched will be handed over to the demons… [and thrown] into the dungeon of Hell”. |

| 52 | The engraving is inserted between pp. 62 and 63. (Izquierdo 1675). |

| 53 | Gregorio Fosman y Medina, chalcography engraver and painter from Madrid who lived between 1635 and 1713. He was well known, and his work was extensive and varied. On him, see Aterido (1997, pp. 87–99) and Carrete Parrondo (n.d.). Diccionario de grabadores y litógrafos que trabajaron en España. Siglos XV a XIX. Apéndice. Arte Procomún. (accessed on 23 May 2021) |

| 54 | Engraving included between pp. 138 and 139 of (Olmo 1680) Relación Histórica del Auto General de le Fe que se celebro en Madrid, este año de 1680 con asistencia del Rey N. S. Carlos II y de las Magestades de la Reina N. S. y de la Augustissima Reina Madre… Por Joseph del Olmo… Impresso por Roque Rico de Miranda, Año 1680. |

| 55 | I described this type of ephemeral architectures and their functions, precisely referring to the auto-da-fé reflected in Fosman’s engraving, which took place in Madrid in 1680, in my article “Las estrategias de la imagen y el grabado como crónica de la realidad” (Cuesta García de Leonardo, forthcoming). |

| 56 | Alardo de Popma, engraver of pieces of chalcography, was born in Flanders and settled in Spain before 1617, where he died in 1641. He had a very large production of pieces of chalcography and of very good quality, especially in book covers. See information about this author and his work in: (Blas et al. 2011, pp. 293–334). |

| 57 | The book referred to is Primera parte de las noticias historiales de las Conquistas de tierra firme en las Indias Occidentales. Compuesto por el padre Fray Pedro Simon Provincial de la Seráfica Orden de San Francisco, del Nuevo Reyno de Granada en las Indias, Lector Jubilado en Sacra Theologia, y qualificador del Santo Officio, hijo de la Provincia de Carthagena en Castilla, Natural de la Parrilla Obispado de Cuenca. Dirigido a nuestro invictissimo y maior monarca del Antiguo y nuevo Mundo Philippo quarto en su Real y supremo Consejo de las Indias. Con previlegio Real En Cuenca en casa de Domingo de la Yglesia, [1627]. |

| 58 | Friar Pedro Simon “was sent as a missionary to America and left… towards the New Kingdom of Granada… in 1604, together with… other eleven Franciscans”. From 1605 he practiced “el lectorado de Artes y Teología de la Orden (lectureship of Arts and Theology of the Order) in the capital of New Granada”; “he was named superior of the religious of a province (Provincial) of his Order. From then on, he dedicated himself to writing his historical work, Noticias historiales de las conquistas de tierra firme en las Indias Occidentales. At the end of the triennium of his ministry as superior of province, he was assigned to the San Diego Convent in Ubaté, where he was probably surprised by death”. He traveled and “got to know… the Andean regions of Tolima and Huila and the cruelties of the war that were made against these natives to reduce them”; he also traveled “between 1612 and 1613 and his objective was to gather historical data for his work, something that his superiors asked him to do… to write the history of the inhabitants of the territories that had been called Tierra firme in the 16th century, that is, Venezuela and Colombia… consulting all the existing bibliography… searching for other sources as well. He read and re-read the memorials of the conquistadors, collected oral accounts of many of those who were still alive and finally did a research work in the archives”. (according to Manuel Lucena Salmoral (n.d.), on the Real Academia de la Historia page http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/18074/pedro-simon, accessed on 17 April 2021). |

| 59 | * Translation of old Spanish: “The Tiara of the Supreme Pontiff has three Crowns, which implies that the Roman Catholic Church is the absolute mistress of the three parts of the world. Also, a fourth Crown should be added, for Spain, which has been added to its jurisdiction, and command, as are these West Indies, or the New World, by the industry of the Castilians, by virtue of the great power of their Kings…; a fourth Crown can be added to that of the Supreme Pontiff, on the part of our Spain… having conquered it by force of arms, and that the world may know the increases that Spain has made in the expansion of the Faith”. |

| 60 | QUARTUM OFFERO PRO INDIS: “I offer the fourth for the Indians”. |

| 61 | See the similarity of the portrait of Philip IV in this engraving with the portrait in oil of the same king, painted by Velázquez in 1624 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), or with the bust portrait that Velázquez also painted of him between 1626 and 1628, dressed in armor (Museo del Prado, Madrid). It could be said that, considering the numerous portraits that Velázquez painted of the king during this period, one of these may have served as a model for the engraving in question. |

| 62 | See the portrait in oil of Urban VIII, painted by Pietro da Cortona in 1624 (Capitoline Museums, Rome). |

| 63 | See the comment on this engraving, its author, Alardo de Popma, and the rest of his work, in (Blas et al. 2011, pp. 293–384; for the above quote: p. 320). |

| 64 | See references to this engraving in (Blas et al. 2011, p. 321) and in (Gómez Urdáñez 1999, p. 128). |

| 65 | The book referred to is Conservación de Monarquías y Discursos Políticos sobre la gran Consulta que el Consejo hizo al Señor Rey don Filipe Tercero, Al Presidente y Consejo Superior de Castilla, por el Licenciado Pedro Fernández Navarrete (1626) Canonigo de la Iglesia Apostólica de Señor Santiago Capellan y S. de sus Magestades y Altezas Consultor del Sto. Oficio de la Inquisición. Con Privilegio. En Madrid en la Imprenta Real Año M.DC. XXVI. |

| 66 | F. Agus. Leonardo Inven. Alardo de Popma Sculp. (as added on the cover). Agustin Leonardo was a Mercedarian friar and painter of the first half of the XVII century. |

| 67 | Among his various positions, he was: “solicitor of the mesa capitular (chapter table), secretary, mayor of the Cabildo (Chapter), vicar of the dean, archivist, reliquary and visitor of the Chapter Treasury. All this administrative work allowed Navarrete to know firsthand the main complaints of the peasants who cultivated the lands of his possessions and to confirm the importance of agriculture for the State. He combined these tasks in the Chapter with academic work at the University of Santiago de Compostela, first as ordinary visitor (1595) and later as vice rector … At the end of 1599 Navarrete left the city of Santiago de Compostela to offer his services to the Crown. His career in the Court was at the service of the Cardinal Infante Fernando, younger brother of Philip IV of Spain, to whom he was chaplain and personal secretary. During that period, he made a trip to Rome as ambassador of Philip III to manage matters related to the Royal Chapel”. In his work, he intends to comment on remedies to confront the problems the kingdom was facing: “Depopulation and poverty, laziness and idleness, were different components of a central social problem: the abandonment of ancestral and traditional virtues. His solution consisted in a change of attitudes: “temperance and frugality, which is the mildest, best known and most experienced medicine in other provinces that suffered the same accidents”…”. Nieves San Emeterio Martín (n.d.), text taken from the page of the Real Academia de la Historia. http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/21417/pedro-fernandez-de-navarrete, accessed on 17 April 2021. |

| 68 | * Translation of old Spanish: “depopulation of Castile… taxes… financial problems… the ‘expenses of conservation and defense of the monarchy’…”. |

| 69 | On the dado of the left acropodium, the one holding the brother, it says: “Venerable Father Friar Alonso Navarrete protomartyr of the religion of St. Dominic, brother of the author, suffered in Japan in the year 1617”). On the right: “Venerable Father Alonso Mena Navarrete religious of St. Dominic cousin brother of the Author suffered in Japan year 1624”. |

| 70 | PRO LEGE ET REGE: “For the law and the king”; PRO REGE ET LEGE: “For the king and the law”. |

| 71 | STEMATE RELIGIONE ET CHARITATE CONIUNTI: “United by the crown, religion and charity”. |

| 72 | Wisdom is a young woman holding a lighted lamp filled with oil and a book, and Prudence is represented by a woman who “must be looking at herself in a mirror, seeing a snake wrapped around her arm”. According to C. Ripa, in his Iconologia, Rome, 1593 (Ripa [1593] 1987, vol. II, pp. 279 and 233 respectively). |

| 73 | EGO IN CONSILIO HABITO: “I inhabit in reason”-ERUDITIS INTERSUM COGITATIONIBUS: “I am in the wise reflections”. |

| 74 | See, for example, Diego Saavedra Fajardo (Munich, 1640) in his Empresa 28: “Prudence is the rule and measure of the virtues; without it, they become vices…. This virtue is what gives governments the three forms of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy, and constitutes their parts proportionate to the natural nature of the subjects, always attentive to their conservation and the main goal of political happiness. Anchor is the prudence of the States, the ship’s compass of the prince. If this virtue is lacking in him, the soul of government is lacking” Saavedra ([1640] 1976, vol. I, p. 286). * Translators note. |

| 75 | Curiously, it is in Discurso XLIII, where he defends “that they could not practice under twenty years of age, nor be received under sixteen years of age”, in relation to the excessive and very early entry of young people into religious orders, one of the reasons for the depopulation of rural areas, he speaks of the maturity required for this vital option, which will bear excellent benefits, such as that of his brother and cousin: “Notable men, to propagate and spread the Catholic Faith, planting it with much work in remote provinces and watering it with their own blood, as did my glorious brother Friar Alonso Navarrete Provincial Vicar of the Dominican Order, in the Philippines, who after having made a pilgrimage of more than eleven thousand leagues in search of martyrdom, obtained it in the Island of Tacaxima, one of the islands of Japan, in the year of 1617, being the protomartyr of his Religion in those Provinces, in whose imitation Friar Alonso de Mena Navarrete, my cousin brother, son of the same religion of Saint Dominic, was burned alive on a slow burn in the city of Vomura, with many other martyrs, in the year 1622” (Fernández Navarrete 1626, p. 290). |

| 76 | It is the theme that integrates the delivery of the scapular by the Virgin to Simon Stock (XIII century) and the so-called Sabbatine Privilege for those who wore it, according to the vision of Pope John XXII, both episodes with a wide Carmelite iconic representation. See: (Pinilla 2016, pp. 483–98). |

| 77 | The original late 17th century textbook referred to is Cinco palabras del apóstol San Pablo, Comentadas Por el Angelico Doctor Santo Thomas de Aquino y declaradas por el menor Carmelita Descalço Fray Francisco de la Cruz. Con Doctrina de su Madre Serafica Santa Teresa de Jesus y exemplos de su Orden que dispiertan para vivir y morir bien. Tomo segundo. Contiene dos palabras, credenda, speranda. Impresso en Napoles por Marco Antonio Ferro año 1680. Y reimpresso en Valencia por Antonio Balle año 1724. This book is a continuation of the first volume of the same title, only different in: “Tomo primero. Contiene tres palabras, agenda, timenda, vitanda” and in: “Y reimpresso en Valencia por Antonio Balle año 1723”. |

| 78 | Recall, for example, the book by Jerónimo Nadal (1595), Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangelia quae in sacrosancto missae sacrificio toto anno leguntur: cum Evangeliorum concordantia historiae integritati sufficienti: accessit & index historiam ipsam evangelicam… excudebat Martinus Nutius, Amberes. With engravings by Hieronymus Wierix. |

| 79 | The similarity with the structure of contemporary comic is clear, of which, undoubtedly, this type of engraving is a precedent. |

| 80 | He signs as Quart fet. Valª (which would indicate that he did his work in Valencia); as F. Quart fet. o just Quart fet. In the second part of the book, with images that allude to the afterlife, another engraver intervenes in at least 2 engravings, very similar in everything to those of Quart, and with an illegible name (perhaps Phaer F.). Curiously, the times it appears, it is crossed out, as if the name had been erased deliberately on the chalcography plate. Opinions differ on F. Quart: according to the (Biblioteca Nacional n.d.) http://datos.bne.es/persona/XX1524892.html (accessed on 24 April 2021), he is an 18th century engraver; however, according Carrete Parrondo et al. (1981, pp. 76–77), in the catalogue Estampas. Cinco siglos de Imagen impresa, Ministerio de Cultura, Madrid, he is a Valencian engraver from the 17th century. |

| 81 | * Translation of old Spanish: “the revelations of Venerable Mother Francisca of the Blessed Sacrament”. |

| 82 | * Translation of old Spanish: “dignity… if it is well served, they will have supreme crowns [those who exercise it]; if badly served, terrible torments.” |

| 83 | * Translation of old Spanish: “to have interpreted an obedience”. |

| 84 | * Translation of old Spanish: “in this way, the souls that keep the rule with perfection are rewarded”. |

| 85 | * Translation of old Spanish: “Those of us who are alive are unaware of the terrible nature of those pains, and they are so terrible and so many that all those who have come from the other world to ask to get out of those pains, have said that one day in Purgatory is more than a thousand years in this world…”. |

| 86 | “Wooden box with flat lid”. |

| 87 | * Translation of old Spanish: “Many people had the hand copied to have it in their homes, in memory of the event and in testimony of the strength that… prayers… have to liberate the Animas from Purgatory”. |

References

- Aristóteles, Horacio. 1988. Artes Poéticas. Madrid: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Aterido, Angel. 1997. El grabador madrileño Gregorio Fosman y Medina. Anales del Instituto de Estudios Madrileños 37: 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez de Pedraza, Francisco. 1638. Historia Eclesiástica. Principios y progressos de la ciudad, y religión católica de Granada Corona de su poderoso reyno y excelencias de su corona. Granada: Andrés de Santiago en la Imprenta Real. [Google Scholar]

- Biblioteca Nacional. n.d. Available online: http://datos.bne.es/persona/XX1524892.html (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Blas, Javier, María Cruz De Carlos Varona, and José Manuel Matilla. 2011. Grabadores extranjeros en la Corte española del Barroco. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España, Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica. [Google Scholar]

- Carrete Parrondo, Juan, Javier Fernández Delgado, and Jesusa Vega. 1981. Estampas. In Cinco siglos de Imagen impresa. Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Carrete Parrondo, Juan. n.d. Diccionario de grabadores y litógrafos que trabajaron en España. Siglos XV a XIX. Apéndice. Arte Procomún. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/arteprocomun/ (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Cuesta García de Leonardo, María José. Forthcoming. “Las estrategias de la imagen y el grabado como crónica de la realidad”. In Humanitatis Alma. Estudios en Homenaje al Profesor Pedro Miguel Ibáñez Martínez. La Mancha: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Castilla.

- de Castro, Francisco. 1588. Historia de la vida y sanctas obras de Iuan de Dios, y de la institución de su orden, y principio de su Hospital. Granada: Imprenta de Rene Rabut, Original published in 1585 by Granada: Imprenta de Antonio de Librixa. [Google Scholar]

- de Medina, Pedro. 1604. Victoria gloriosa, y excelencias de la esclarecida Cruz de Iesu Christo nuestro Señor. Granada: Fernando Diaz de Montoya. [Google Scholar]

- Defradas, Liliane, and Robert Klein. 1989. Pomponio Gaurico. In Sobre la escultura. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Navarrete, Pedro. 1626. Conservación de Monarquías y Discursos Políticos sobre la gran Consulta que el Consejo hizo al Señor Rey don Filipe Tercero, Al Presidente y Consejo Superior de Castilla. Madrid: Imprenta Real. [Google Scholar]

- Francisco de la Cruz. 1724. Cinco Palabras del Apóstol San Pablo, Comentadas Por el Angelico Doctor Santo Thomas de Aquino y declaradas por el Menor Carmelita Descalço Fray Francisco de la Cruz. Con Doctrina de su Madre Serafica Santa Teresa de Jesus y exemplos de su Orden que dispiertan para vivir y morir bien. Tomo Segundo. Contiene dos Palabras, Credenda, Speranda. Impresso en Napoles por Marco Antonio Ferro año 1680. Y reimpresso en Valencia por Antonio Balle año 1724. Valencia: Antonio Batlle. [Google Scholar]

- García-Melero, Lourdes. 2017. Medallas de la Orden Hospitalaria de San Juan de Dios en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional. Boletín del Museo Arqueológico Nacional 36: 293–318. [Google Scholar]

- Gaurico, Pomponio. 1989. Sobre la escultura. Madrid: Akal. First published 1504. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Urdáñez, José Luis. 1999. Conservación de Monarquías y Discursos Políticos sobre la gran Consulta que el Consejo hizo al Señor Rey don Filipe Tercero… (1626). In Arte y Saber. La cultura en tiempos de Felipe III y Felipe IV. Valladolid: Museo Nacional de Escultura, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Ayuntamiento de Valladolid, p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Moreno, Manuel. 1950. Primicias Históricas de San Juan de Dios. Madrid: Provincias Españolas de la Orden Hospitalaria. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1985. Las vías de la creación en la iconografía cristiana. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, Sebastián. 1675. Práctica de los Ejercicios espirituales de Nuestro Padre San Ignacio. Roma: El Varese. [Google Scholar]

- Labarga, Fermín. 2016. El rostro de Cristo en el arte. Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia 25: 265–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larios, Juan Miguel. 2006. San Juan de Dios. La imagen del santo de Granada. Granada: Comares. [Google Scholar]

- Maravall, José Antonio. 1975. La cultura del Barroco. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Rojas, Francisco Juan. 2009. Los procesos de beatificación de San Juan de Dios y San Juan de Ávila. Archivo Hospitalario 7: 557–65. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, Antonio. 1979. Algunas consideraciones en torno a la hagiografía en el grabado granadino del siglo XVII: Dos xilografías de San Juan de Dios. In Estudios sobre literatura y arte: Dedicados al profesor Emilio Orozco Díaz. Granada: Universidad de Granada, vol. 2, pp. 473–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal, Jerónimo. 1595. Adnotationes et meditationes in Evangelia quae in sacrosancto missae sacrificio toto anno leguntur: Cum Evangeliorum concordantia historiae integritati sufficienti: Accessit & index historiam ipsam evangelicam. Amberes: Excudebat Martinus Nutius. [Google Scholar]

- Olmo, Joseph del. 1680. Relacion historica del auto general de fe que se celebro en Madrid este año de 1680. Con assistencia del Rey N. S.Carlos II y de las Magestades de la Reina N. S. y la Augustissima Reina Madre. Siendo Inquisidor General el Excelentmo. Sr. D. Diego Sarmiento de Valladares. Dedicada a la S. C. M. del Rey N. S. Refierense con curiosa puntualidad todas las circunstancias de tan Glorioso Triunfo de la Fe con el Catalogo de los Señores que se hizieron Familiares y el Sumario de las Sentencias de los Reos. Va inserta la Estampa de toda la Perspectiva del Teatro, Plaça y Valcones. Madrid: Impreso por Roque Rico de Miranda. [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla, María José. 2016. La Entrega del Escapulario a San Simón Stock y el Privilegio Sabatino, dos temas marianos carmelitanos ilustrados por un precursor de Arnold van Westerhout. In Regina Mater Misericordiae. Estudios Históricos, Artísticos y antropológicos de advocciones marianas. Córdoba: Ediciones Litopress, pp. 483–98. [Google Scholar]

- Popes, Pius V, Gregory XIII Popes, and Sixtus V Popes. 1596. Bulas Apostólicas Concedidas por la Santidad de Pio V y de Gregorio XIII y Sixto V a los Hermanos de la orden y Hospitalidad de Juan de Dios, las Quales valen en España, y en las Indias, y en Todas las Demás partes donde Estuvieren los Hermanos de la dicha Hospitalidad. Madrid: P. Madrigal Impresor. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, Juan Antonio. 1988. Medios de masas e Historia del Arte. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Ripa, Cesare. 1987. Iconología. Tomos I y II. Madrid: Akal. First published 1593. [Google Scholar]

- Román, Fray Hierónimo. 1575. Republicas del Mundo. Medina del Campo: Francisco del Canto, Impresor. [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra, Diego. 1976. Empresas políticas [Idea de un Príncipe Político Christiano representada en cien Empresas]. Madrid: Editora Nacional, Vols. I and II. First published 1640. [Google Scholar]

- Sagredo, Diego de. 1986. Medidas del Romano. Madrid: Dirección General de BB. AA. y Archivos, Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos. First published 1526. [Google Scholar]

- Salmoral, Manuel Lucena. n.d. Real Academia de la Historia. Available online: http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/18074/pedro-simon (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- San Emeterio Martín, Nieves. n.d. Real Academia de la Historia. Available online: http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/21417/pedro-fernandez-de-navarrete (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Simón, Fray Pedro. 1627. Primera parte de las noticias historiales de las Conquistas de tierra firme en las Indias Occidentales. Cuenca: Domingo de la Yglesia, Impresor. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa, Philippe de. 1569. Libro de la Primera parte, de la excelencia del Sancto Evangelio, en que se contiene un breve Compendio, de los Mysterios de la venida de Jesuchristo nuestro Señor al mundo. Con las calidades y condiciones que pertenecen a este tan alto Sacramento de la Encarnación, y de la reparación de la culpa general. Contiene se principalmente en este libro, todo el discurso hystorial, de cada uno de los misterios, de la ultima y soberana Cena, que Christo celebro: Y los de su muy sancta Muerte y Passion. Con las circunstancias y claridad, de cada una destas obras, en que la Magestad del muy alto Señor (tan señaladamente) puso la mano. Dispuesto y dividido en quatro libros, para mayor claridad de esta historia. Con un breve y compendioso tractado, de los Mysterios que succedieron, desde que Christo espiro en la Cruz, hasta que en cuerpo glorioso, y familiarmente, apareció à la gloriosa Virgen su madre, y a todos los otros Apóstoles y Discípulos (que por dispensación Divina) fueron elegidos, para ser testigos idóneos, destos tan altos Mysterios, después que rescibieron la investidura de la predicación del sancto Evangelio. Ahora nuevamente collegido, de los Originales de las scripturas Sanctas de ambos Testamentos. Y de los libros de los mas antiguos y escogidos Doctores de yrrefragable autoridad, que desta materia tractan. Sevilla: Juan Gutierrez impresor. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, Laura Liliana. 2009. Aspectos generales de la estampa en el Nuevo Reino de Granada (siglo XVI-principios del siglo XIX). Fronteras de la Historia. Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia 14: 256–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vitruvio. 1991. Los diez libros de arquitectura. Barcelona: Iberia. [Google Scholar]

- Zafra, Rafael. 2014. Los icones de varones ilustres: ¿un sub-género emblemático? Imago, Revista de Emblemática y Cultura Visual 6: 129–43. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuesta García de Leonardo, M.J. Engraving and Religious Imagery in the Modern Age: Between Verisimilitude and the Suggestion of Non-Existent Realities. Analysis of Some Cases Elaborated in Spain. Religions 2021, 12, 1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121096

Cuesta García de Leonardo MJ. Engraving and Religious Imagery in the Modern Age: Between Verisimilitude and the Suggestion of Non-Existent Realities. Analysis of Some Cases Elaborated in Spain. Religions. 2021; 12(12):1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121096

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuesta García de Leonardo, María José. 2021. "Engraving and Religious Imagery in the Modern Age: Between Verisimilitude and the Suggestion of Non-Existent Realities. Analysis of Some Cases Elaborated in Spain" Religions 12, no. 12: 1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121096

APA StyleCuesta García de Leonardo, M. J. (2021). Engraving and Religious Imagery in the Modern Age: Between Verisimilitude and the Suggestion of Non-Existent Realities. Analysis of Some Cases Elaborated in Spain. Religions, 12(12), 1096. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121096