Abstract

The creation of Adam out of dust is a familiar tradition from the Book of Genesis. In abolitionist literature of the nineteenth century, this biblical narrative became the basis for a theory about the origins of race, arguing that because Adam was formed from red clay, neither he nor his descendants were white. This interpretation of Genesis underscored the value of non-white ancestors both in the biblical narrative and in human history and undermined popular theological arguments that upheld color-based racial hierarchies that privileged whiteness in the United States. This article examines the creation of Adam in Genesis 2 and its use in racial theory and abolitionist rhetoric, focusing on the children’s anti-slavery periodical The Slave’s Friend, published from 1836 to 1838.

Yahweh Elohim formed man with dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils, and he became a living being. (Genesis 2:7)

Question: Of what color was Adam?

Answer: The color of red clay, I presume.

Q: Were all Adam’s children of the same color?

A: There is every reason to suppose they were… (The Slave’s Friend, I [5], 4)

1. Introduction

In the Book of Genesis, Yahweh Elohim1 creates the first human out of dust (ʿāpār) from the ground (ʾădāmâ), shaping and breathing life into the figure known as Adam. The very name Adam emphasizes the raw material out of which this first human was made. While much has been written about the use of biblical narrative in nineteenth-century discourse about race, slavery, and abolition, particularly the so-called “Curse of Ham” in Genesis 9, the creation of Adam has received less attention.2 This essay examines the interpretation of the creation of Adam in abolitionist literature, focusing on a children’s periodical called The Slave’s Friend, which ran from 1836 to 1838. Drawing upon the material imagery in the biblical narrative, The Slave’s Friend constructs its own theory of the origins of race in order to undermine alternative views of biblically based racial hierarchy. According to this theory, Adam himself was made from red clay, making neither him nor his descendants white. This interpretative move, which recurs throughout the run of The Slave’s Friend, highlights a key issue both in the Hebrew Bible and antebellum discourse about race—that is, the couching of identity and subject formation in material terms. Furthermore, arguing that Adam himself was not white simultaneously upholds the theory of monogenesis, the single origin of all human beings, while undermining the reliance upon later texts in the biblical narrative, especially Genesis 9, for constructing racial hierarchies that privilege whiteness. In this way, the non-whiteness of Adam countered popular anti-Black etiologies of the period and offered a new biblical paradigm for the explanation and evaluation of racial difference.3

The idea that Adam was formed from red clay is widely attested in the nineteenth century, and the circulation of this trope in The Slave’s Friend develops it further, considering the implications of the “redness” of Adam on modern taxonomies of race. Proslavery apologists also seem to have inherited this interpretive tradition and sought to manage their anxiety about it by rewriting the creation of Adam, as in the work of Josiah Priest, which I will discuss further below. The “red clay” of Adam featured in earlier racial discourses as well, including the widespread association of Native Americans with “redness” in the eighteenth century. As Nancy Shoemaker demonstrates, the category of “redness” appears both as a marker of Native American self-identification in this period and one assigned by white Europeans (Shoemaker 1997, pp. 625–44). Some tribal traditions featured their own accounts of creation in which the first humans were molded from red clay, which some Christian missionaries then elided with the biblical creation of Adam.4 The European discovery of the Americas troubled preexisting human taxonomies and the biblical origin stories that supported them, and the creation of Adam was already a model for managing this new world and categorizing its people on the basis of color in the eighteenth century.

The deployment of the Genesis creation stories in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century racial discourse is a paradigmatic example of biblical mythmaking. As an etiology itself, the creation of Adam can be easily labeled as a “myth” in the classic sense—it is a story about divine beings set in a distant past.5 However, in the context of the abolitionist rhetoric in The Slave’s Friend, this story also behaves like a myth, in the sense that it is fundamentally “ideology in narrative form”(Lincoln 1992, p. 147). In the hands of abolitionist writers, the creation of Adam becomes a foundational text for the taxonomy of race among the first human beings, which is then used to reconfigure racial hierarchies of the nineteenth century and to support the emancipation of enslaved persons in the United States. Scholarship on myth theory emphasizes this socially constructive nature of myth. As Russell McCutcheon puts it, “Mythmaking is a species of ideology production, of ideal-making, where ‘ideal’ is conceived not as an abstract, absolute value but as a contingent, localized construct that comes to represent and simultaneously reproduce certain specific social values as if they were inevitable and universal”(McCutcheon 1999, p. 204). The interpretation that Adam was formed from red clay, a reading of the Hebrew term ʾădāmâ that was already well attested in antiquity, was thus fertile ground for abolitionist mythmaking. By emphasizing the “redness” of Adam in the Genesis 2 narrative, abolitionist writers are able to argue for a taxonomy of race that is not radically new but, in fact, is as old as Adam.

By nature, myth is concerned with a particular vision of the past, often one that provides a coherent account of a community and where it is headed. As Elizabeth Castelli notes, “Myth is the text of a utopian dream, a dream about a complete and seamless story that has the capacity to suture the present (and the future) to the past”(Castelli 2004, p. 30). However, the process of mythmaking takes place in a world of conflicting claims to that shared past. Competing uses of myth coincide with competing political projects. Nowhere is this more apparent than the deployment of biblically based arguments on opposing sides of abolition debates in the nineteenth century. As one might expect, it also appears in proslavery interpretations of the red clay in the creation of Adam, which provides a counter-narrative to the biblical taxonomy of race promoted by The Slave’s Friend. The existence of this proslavery counter-narrative further demonstrates the potency of the biblical myth and its relevance to nineteenth-century debates over what race is and where it originates.

This essay examines the interpretation of the creation of Adam in Genesis 2 and its use in nineteenth-century racial theory and abolitionist rhetoric, focusing on the children’s anti-slavery periodical The Slave’s Friend. It begins with an introduction to the publication, drawing particular attention to its biblical hermeneutics and pedagogical apparatus. As a periodical designed for a young audience, it frequently draws upon the Book of Proverbs and its paternalistic model for educating children and inculcating them with particular values. Though children’s literature in this period may sometimes be dismissed as superficial and overly sentimental, the ideological work of this literature is not mere child’s play. The interpretation of the creation of Adam throughout the run of The Slave’s Friend demonstrates this point. As I go on to argue, the focus on the red clay of Adam draws upon a more widespread discourse in the Hebrew Bible that closely associates materiality with identity and subject formation. For abolitionists, the red clay of Adam’s creation is a generative metaphor, one that helps construct a taxonomy of race that de-centers whiteness in the biblical narrative and supports the emancipation of enslaved persons in the United States.

2. The Slave’s Friend (1836–1838)

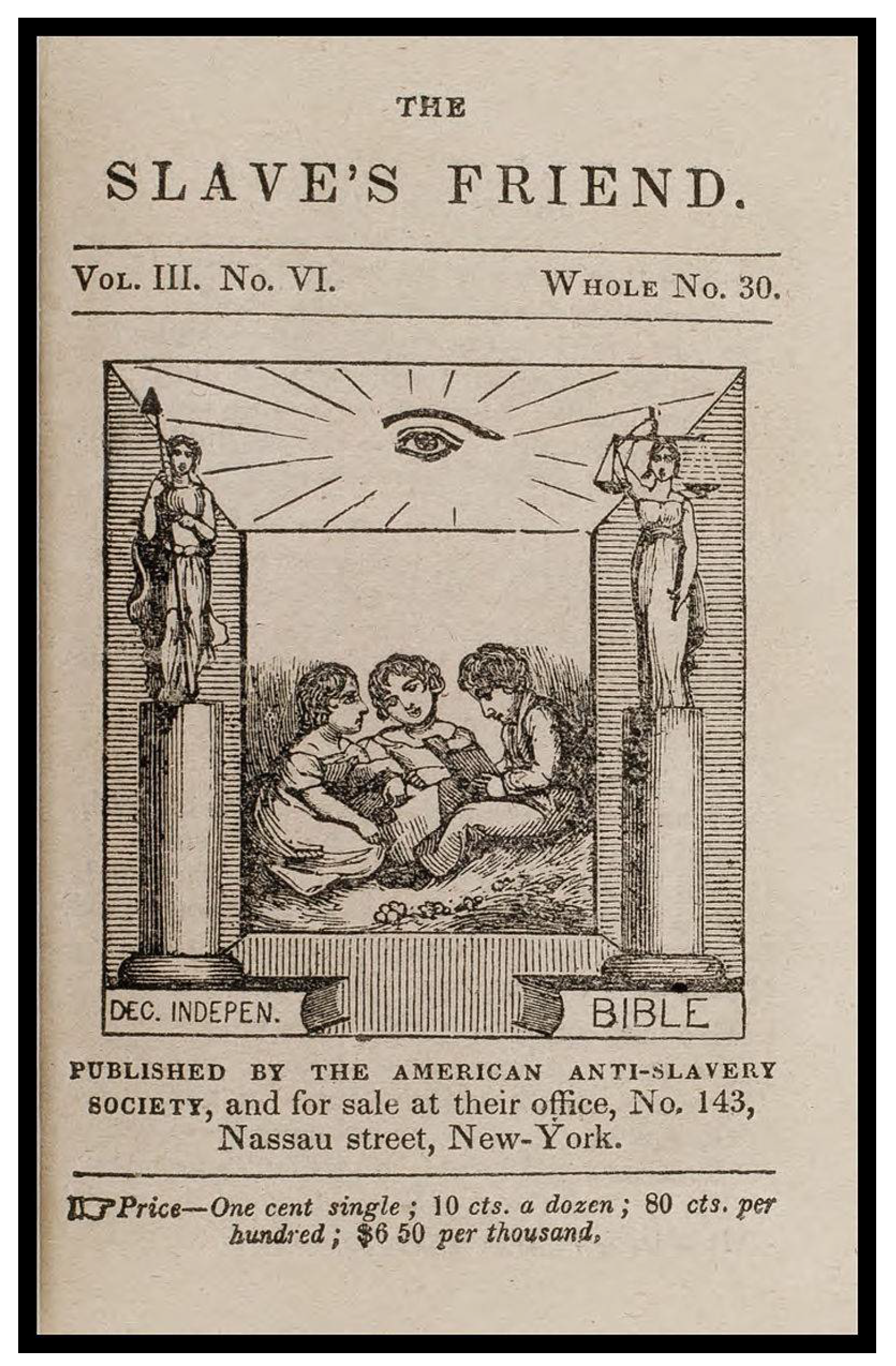

Published by the New York Anti-Slavery Society, The Slave’s Friend was a sixteen-page monthly periodical launched in 1836 that went on to print thirty-eight issues in four volumes until it was shut down in 1838. One of several publications produced by the society, including Human Rights, the Anti-Slavery Record, and the Emancipator, The Slave’s Friend was edited by New York abolitionist Lewis Tappan and printed by R.G. Williams (Wyatt-Brown 1969, pp. 126–45). The intended audience for the publication was made up of white children, ages six to twelve (Geist 1999, p. 28), and the diminutive size of the periodical, measuring 3 by 4.25 inches, visually reflects that young readership. Targeting such an audience, The Slave’s Friend featured a diverse assortment of items within its pages, including proceedings from the Juvenile Anti-Slavery Society, woodcut illustrations, literary vignettes about abolitionist children and enslaved persons, anti-slavery poetry, and brief pieces of theological reflection. Most of the items within an issue are anonymous, though sometimes they would include excerpts from the speeches and works of well-known figures such as Thomas Jefferson and members of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

As with much abolitionist material of this period, The Slave’s Friend often cited biblical texts as justification for the immediate abolition of slavery in the United States, the assumption being that, when read correctly, the Bible upheld the Enlightenment values of liberty, equality, and common humanity that were incompatible with chattel slavery. Another fundamental assumption in this interpretation of the Bible was the belief that scripture not only depicted the will of God in ancient times but also continued to function as a charter for American society in the nineteenth century (Noll 2006, p. 22). Cover art from The Slave’s Friend, as seen below, reflects this assumption about the compatibility of the Bible with the principles outlined in the founding documents of the United States.6

However, as previous studies have argued, a literal, plain-sense reading of certain biblical texts challenged these assumptions, leading abolitionist writers to adopt different reading strategies for the Bible (Harvey 2016, p. 77; Lowance 2018, pp. 88–90). These writers sometimes embraced more historical-critical readings of the biblical text, while others ignored more problematic passages entirely. J. Albert Harrill characterizes the emerging biblical hermeneutics of nineteenth-century writers as follows:

This reading strategy characterizes the biblical interpretation found in The Slave’s Friend, particularly the use of the Bible to confront the modern category of race.American literary studies, undergoing professionalization, was moving toward a critical hermeneutics (influential on biblical studies) that not only aimed at recovery of the author’s intended meaning as a norm for validating conflicting readings of a text but also aimed to complete and develop what the author had only sketched and suggested—a task that inevitably carried the critic beyond the author’s intention into a hermeneutics of moral intuition.(Harrill 2000, p. 150)

In many ways, The Slave’s Friend reflects the voice and values of abolitionist literature of the 1830s. It differs, however, in its appeal to a juvenile audience, attempting to inculcate abolitionist values in children by exposing them to the horrors of slavery and racial discrimination. For that reason, The Slave’s Friend takes on a more pronounced didactic tone than other abolitionist periodicals of the time. While the rhetoric and sentimentality of The Slave’s Friend may seem childish and superficial, scholars such as Caroline Levander make compelling arguments as to why children’s literature is crucial for understanding the abolitionist rhetoric of this period. For instance, in this period, the child is a “particularly rich discursive site” where national identity—and the role of race in that identity—is negotiated (Levander 2006, p. 31). Additionally, Holly Keller argues that abolitionist children’s literature, including classic texts such as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was more subversive than previous studies have acknowledged, since they encouraged children to challenge the moral authority of their elders with regard to slavery (Keller 1996, p. 87). The ideal child envisioned by this literature was “innocent, virtuous, and instinctively color-blind” and thus symbolized the hope in a new generation raised with different conceptions of racial equality that could institute radical reforms in the United States. Therefore, children’s periodicals such as The Slave’s Friend provide a window into abolitionist rhetoric, its vision for the future, and its use of the Bible to construct alternative theories about race and its origins.

A fundamental part of the dynamics of the pedagogical apparatus at work in The Slave’s Friend is its use of the Book of Proverbs. Due to its focus on educating children, it perhaps comes as no surprise that The Slave’s Friend often refers to the Book of Proverbs explicitly and adopts its framework of paternalistic pedagogy. Both the form and content of The Slave’s Friend reflect the influence of the Book of Proverbs on its approach to instructing children about slavery and abolition, and one of the most frequently cited biblical passages throughout the series is Proverbs 31:8–9: “Open thy mouth for the dumb, In the cause of all such as are appointed to destruction. Open thy mouth, judge righteously, and plead the cause of the poor and needy.”7 In addition to explicit quotations of Proverbs, a common type of text featured in The Slave’s Friend is a dialogue between parent and child, reminiscent of a parent’s instruction in biblical wisdom literature.8 In Proverbs, this instruction is intended to encourage the development of wisdom and righteousness in the child: “Hear, my child (lit. ‘my son’), your father’s instruction, and do not reject your mother’s teaching, for they are a fair garland for your head and pendants for your neck” (Prov 1:8–9). While passages such as this one refer to the teaching of both the mother and father, the translation used by The Slave’s Friend obscures the predominant dynamic of this biblical discourse—the methodical formation of the son in relation to his father and others.9 The refrain of such discourse is “the fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge,” and the parent is responsible for fostering both fear and wisdom in the child.

The parental dialogue format appears several times throughout The Slave’s Friend and often engages in biblical interpretation concerning a central issue related to race and slavery. In a dialogue between a young son and his father, the two discuss the ethical dilemma of aiding fugitives from slavery.10 The father cites Hebrews 13:2a in support of helping the fugitive, thus defying the law: “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers.” This paternalistic pedagogy prevails throughout The Slave’s Friend, including the notes from the editor. At the end of the first volume, the tract concludes with the following note: “I have tried to please and instruct you, and hope I have done so. Be kind to people of color, pray for the poor slaves, repent of your sins, love God, and obey your parents. Then you will be lambs of Jesus’ flock.”11 In this concluding statement, the editor assumes the role of “father” to the young readers of the periodical, instructing them in abolitionist thinking and feeling. This theme becomes further pronounced in his admonishment to his readers to “obey your parents.” At the end of another issue, the text reads:

“Receive instruction and not silver; and knowledge rather than choice gold.”

Here, the text juxtaposes a quotation from Proverbs 8:10 with a line from a popular hymn at the time.13“Oh, happy is the child that hears Instruction’s faithful voice; And who celestial wisdom makes His early, only choice.”12

The didactic framework of Proverbs is a natural fit for the pedagogical apparatus of The Slave’s Friend. Additionally, the literal paternalism of dialogues between a parent and child serves as a model for the figurative paternalism of the abolitionist movement in its goal to educate both children and enslaved persons.

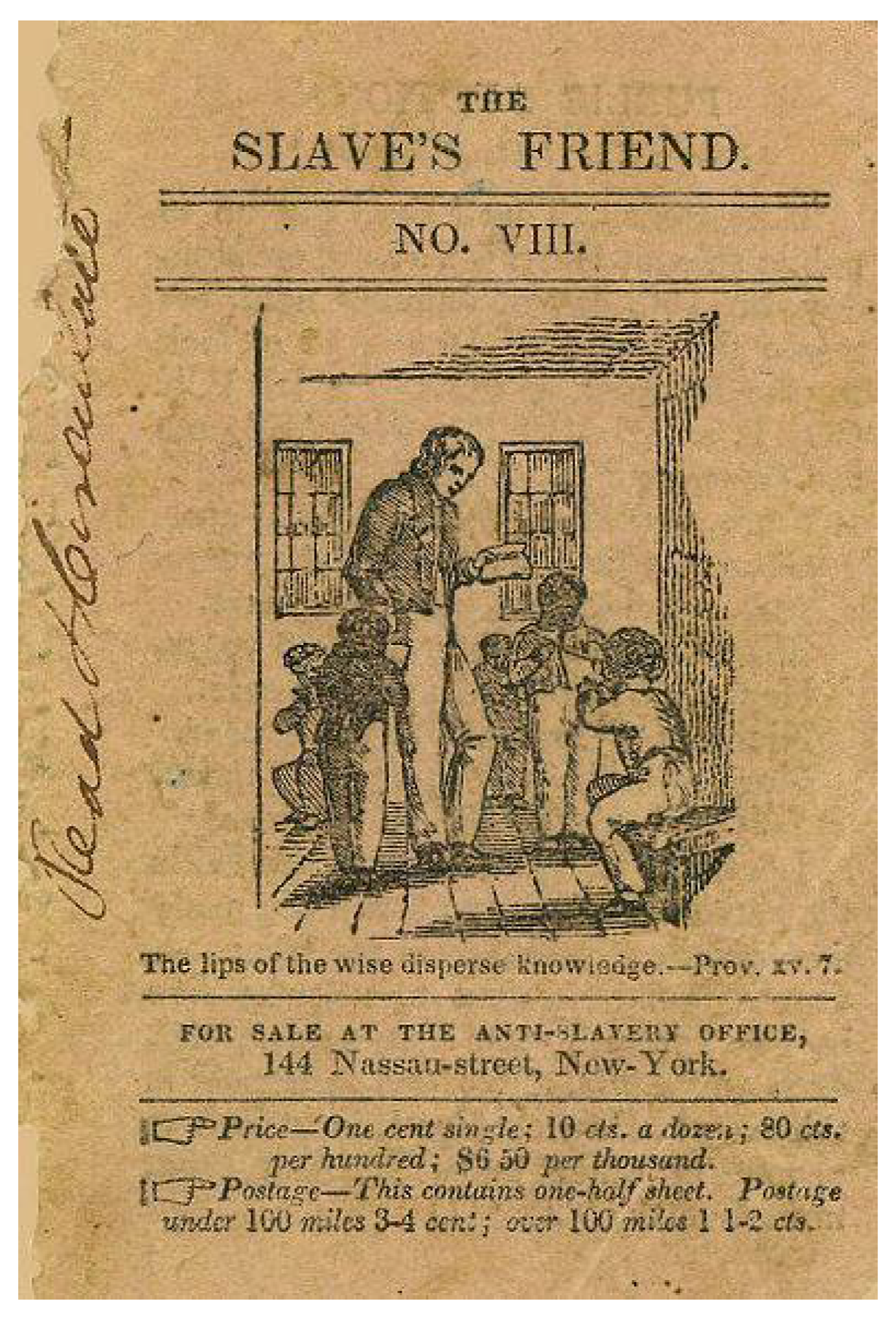

The woodcut illustration above appears on the cover of nearly all issues of The Slave’s Friend in 1836, and it clearly depicts this paternalistic dynamic—a scene in which a white man teaches Black children is juxtaposed with a quotation from Proverbs 15:7. The selection of this image for the cover art of early issues underscores its thematic importance for the pedagogical ethos of the publication overall. More recently, scholars have noted the ways in which this white abolitionist paternalism is problematic, upholding its own racial and class hierarchies. For instance, Spencer Keralis observes that The Slave’s Friend uses the imagery of pet ownership and animal cruelty as a metaphor for teaching white children about Black people and slavery (Keralis 2012, p. 122). Thus, while abolitionist literature argued for the emancipation of enslaved persons, periodicals such as The Slave’s Friend maintained and affirmed fundamental racial and class distinctions in their depictions of white and Black characters. Along similar lines, Susan M. Ryan notes the framing of abolitionist work as contributing to the ethical formation of white children, thus exploiting enslaved persons for the moral benefit of their emancipation (Ryan 2000, p. 705). In other words, the work of emancipation was a means by which white children could become better Christians and citizens. Ultimately, the way that The Slave’s Friend talks to its audience of white children belies a more pervasive paternalistic attitude toward enslaved persons, one that does not eradicate racial hierarchies but manages them instead, and the periodical’s modeling of paternalistic pedagogy on Proverbs lent it moral authority and cultural value.

3. The Creation of Adam and the Biblical Origins of Race

As we can see, the use of biblical literature in abolitionist pedagogy relies upon reading these texts as affirming, undermining, and otherwise negotiating extant social hierarchies. In this context, clay offers a rich metaphor for thinking about identity and human formation, both in the Hebrew Bible and in later interpretative discourse.14 Abolitionist writers in the nineteenth century adopt this metaphor of clay, particularly the creation of Adam from red clay, and use it to construct their own theories of race and human origins. This reading of the text was quite prevalent, despite the fact that the common Hebrew word for clay (ḥōmer) does not actually appear in the story of the creation of Adam, a point to which I will return below. In biblical literature, clay is the raw material of creation, while dust signifies the reversion of creation into some uncivilized or unformed state. In Genesis 2:7, for instance, Yahweh Elohim fashions the first human with dust from the earth and breathes into its nostrils to vivify it. Later in the narrative, following the disobedience of Adam and Eve, the text famously states that they are, in fact, dust and will return to dust in death (3:19). Deprived of divine life-giving breath, humans revert back into dry, inert dust. James Kelso argues that texts such as Job 10:9 draw a similar distinction between dust (ʿāpār) and clay (ḥōmer), the former being “dry native clay that has not yet been worked up into potter’s clay” (Kelso 1948, p. 5). Unlike dust, clay has been mixed with water and worked so that it is pliable enough to be molded by the potter. It is the addition of moisture to dust that makes it a viable material for creation. In the Hebrew Bible, the binary of dry/moist often signifies the difference between the realm of the dead and the living, respectively. In fact, biblical passages emphasizing the life-giving power of Yahweh often use water imagery to do so (e.g., Isa 26:19).

Biblical writers use clay to talk about the formation of humans in a variety of contexts. In Jeremiah 18:4–6, Yahweh tells the prophet to go to a potter’s workshop and watch him at his wheel. After Jeremiah sees the potter at work, Yahweh likens himself to a potter who may remake a damaged pot:

In this passage, the prophet uses the imagery of ceramic production to emphasize Yahweh’s creation of and, thus, sovereignty over human beings. The prophet Isaiah deploys a similar rhetoric when he states, “But now, Yahweh, you are our father. We are the clay. As for you, you are our potter (yōṣrēnû). All of us are the work of your hand” (Isa 64:7). Isaiah’s articulation of this metaphor creates a powerful image in which the molding of clay signifies the creation of a loyal Yahwistic subject. Further, it brings together the overlapping paradigms of product/producer and father/child. As father, Yahweh molds and shapes Israel and individual Israelites into his own creation.When the pot that he made with clay was damaged in the hand of the potter, he made another vessel again, as it seemed fit in the eyes of the potter to make. The word of Yahweh came to me saying, “House of Israel, can I not do to you as this potter does?—oracle of Yahweh. Like clay in the hand of the potter, so you are in my hand, house of Israel.”

This clay imagery also appears in poetic descriptions of birth and death. For instance, Job refers quite explicitly to himself as one who was formed out of clay by God (Job 33:6), and Job 4:17–21 develops this metaphor further when he describes the frailty of the human body:

Can a mortal be righteous before God?

Can a man be pure before his maker?

He (God) does not even trust in his servants,

and he charges his angels with error.

How much more those who live in houses of clay (bāttê ḥōmer),

whose foundation is in the dust (ʿāpār),

who are crushed before twilight.15

Between morning and evening they are destroyed;

when it is not even nightfall16 they perish forever.

Are their tent pegs17 not pulled up within them?

The emphasis on the mortality of human beings in this passage suggests that these “houses of clay” refer not only to the mud-brick structures in which humans dwell but also human bodies themselves. This understanding of clay becomes more apparent with the use of the term ʿāpār, “dust,” in v. 19, which evokes both the creation of Adam and his return to dust in death.They die without wisdom.

As these examples demonstrate, biblical writers use the natural properties of clay to talk about the physical and ideological formation of human beings.18 However, among biblical scholars, it is debated whether or not clay appears in the creation of Adam at all. While the Hebrew term ʾădāmâ does refer to the “ground” or “earth,” it is not the typical term used for clay (ḥōmer) elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, nor does it seem to denote a particular color of earth or clay. Previous commentators such as Claus Westermann critically examined the material terminology of Adam’s creation and what it implies about the nature of creation itself. For instance, Westermann argues that the ʿēd, often translated “mist,” at the beginning of v. 6 does not moisten the “dust” (ʿāpār) from the ground in v. 7, making it pliable like clay.19 Instead, he argues, the divine formation of the first human from dry dust is intended to be nonsensical and inaccessible to human understanding. Nevertheless, the verb used for the formation of Adam in v. 7, yāṣar, is closely associated with the manipulation of clay elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, making Westermann’s argument somewhat less convincing. Further, the use of the verb šāqâ in the Hiphil, meaning “to water, give drink,” contributes to the overall image of a dry land that has been irrigated and, thus, imbued with the potential for life.

Regardless of the protestations of scholars such as Westermann who argue that clay plays no role in the creation of Adam, it is quite clear that both ancient and modern interpreters did read the materiality of Adam in this way. In fact, the idea that Adam was made out of clay—specifically, red clay—is quite ancient, appearing in the writings of Flavius Josephus, who states in his work Jewish Antiquities, “Now this man was called Adam, which in Hebrew signifies ‘red,’ because he was made from the red earth kneaded together; for such is the colour of the true virgin soil” (Josephus, Ant. 1.1.2 [Thackeray]). It is possible that this interpretation of the term ʾădāmâ conflates it with a similar-sounding Hebrew word, ʾādom, “red” or “reddish-brown,”20 used to describe Esau, the brother of Jacob and eponymous ancestor of the Edomites. For instance, at Esau’s birth in Gen 25:25, the narrator emphasizes his ruddy (ʾadmônî), hairy appearance.

More importantly, for exegetes such as Irenaeus of Lyons, the materiality of Adam’s creation was a potent metaphor for subject formation and one’s obedience to God. In his treatise Against Heresies, Irenaeus refers to the “moist clay” (lutum) used to form Adam,21 and Stephen Presley notes that the malleability of clay is construed positively here, associated as it is with receptivity to God and bearing the visible marks of his workmanship. As Presley states, “The creature can become hardened and obstinate toward the Creator and in turn deny the formative presence of the Spirit or remain open and submissive to the Creator allowing themselves to be fashioned by God continually.”22 Much like the divine potter imagery of Jeremiah and Isaiah, Irenaeus depicts subject formation materially, going so far as to gesture back to the creation of Adam and the original formation of the first human from clay.23

Additionally, in his monumental biblical commentary Biblia Americana, Cotton Mather examines the biblical narrative of Adam, emphasizing the red clay of his creation. Spanning from the late seventeenth to the early eighteenth century, Mather’s commentary gathers together anecdotes and interpretations of such biblical narratives and comprises the earliest comprehensive commentary on the Bible written in North America (Mather 2010, p. 3). Mather builds the argument that Adam’s name reflects his ruddy complexion, equating Adam with Edom. Further, he argues that similar terms in other biblical texts, such as Adamdameth in Leviticus 13:19 and Admoni in 1 Samuel 16:12, are part of the same concept cluster, signifying one’s shining, beautiful, and ruddy appearance.24 In fact, he distinguishes the Adamah from which Adam was formed from the more mundane material of animals: “Yea, out of the Dust of this Ground, the finest, purest, & most agile Part of it. Behold, the true, Terra Sigillata, Earth with the Image of God enstamped on it.”25

This idea that Adam was formed from red clay continues into the nineteenth century, appearing in different literary genres including hymns (Ingelow 1878, p. 65), treatises,26 and personal histories.27 In fact, Hebrew lexicographers in the nineteenth century, including Wilhelm Gesenius, also make the etymological connection between ʾădāmâ and redness.28 The Slave’s Friend picks up this discourse about red clay and subject formation but develops it in a different direction, focusing on the divine creation of human difference. Anti-slavery writers such as those featured in the periodical used a particular reading of the creation of Adam, focusing on the redness of this clay, to create a biblical origin story for race. One illustrative example of such biblical mythmaking in The Slave’s Friend uses the format of the dialogue, discussed above. This so-called “Anti-Slavery Catechism” begins by asking “Of what color was Adam?”

Question: Of what color was Adam?

Answer: The color of red clay, I presume.

Q: Were all Adam’s children of the same color?

A: There is every reason to suppose they were.

Q: Of what color was Noah?

A: I suppose the same color as Adam.

Q: Were all Noah’s sons of the same color?

A: There is no doubt of it.

Q: Did not all men now living come from one or the other of Noah’s sons?

A: Yes; nobody denies that.

Q: How came people then to be of different colors now?

A: It is chiefly owing to the climate, that is, the places where they live. Africans live right under the sun, and they are black. Spaniards live further north, and they are lighter. Englishmen and Americans live still further north, and we are called white.

Q: The blood of all is alike, is it not?

A: Yes; the Bible says that; “And hath made of one blood all nations of men, for to dwell on the face of the earth.”29

The argument is simple, accessible even to children. All inhabitants of the earth descend from Adam, who was formed from (what the author presumes to be) red clay. Using the imagery of clay, this reading of biblical origins envisions race as raw material that must be conditioned. In fact, this idea that physical difference is the result of climate was already a well-attested theory in abolitionist thought regarding racial difference (see, e.g., Hopkins [1776] 1785, p. 26). However, the emphasis on the commonality of blood appears in this text and others that profess similar arguments about the biblical origins of race from an abolitionist perspective. In short, the outward differences of human beings belie the essential sameness of their blood, citing Acts 17:26.

This discourse about Adam, clay, and skin color is a running theme throughout The Slave’s Friend. In another issue, the inside cover features a short text called “Difference of Color,” again using the imagery of clay to talk about racial difference:

This particular depiction of different races is featured multiple times in The Slave’s Friend, appearing again in the next year’s volume:God gave to Afric’s sons a brow of sable dye—and spread the country of their birth beneath a burning sky—and with a cheek of olive, made the little Hindoo child, and darkly stained the forest tribes that roam our Western wild. To me he gave a form of fairer, whiter clay—But am I, therefore, in his sight, respected more than they?30

God is no respecter of persons. He hath made of one blood all nations of men, for to dwell on all the face of the earth.

As with the “one blood of all nations” argument above, this text goes on to say that, despite these differences in skin color, God focuses on the “complexion of the heart.” A similar sentiment appears later in this same tract when it quotes the remarks of Rev. Thaddeus Osgood, who had recently traveled in Canada: “There are red children there. But God does not mind color. He loves red children, and black children, and white children, if they are only good.”To Afric’s sons He has given a brow of sable dye…To us He has given a form of fairer, whiter clay.31

This issue also reproduces the remarks of Rev. Mr. J. H. Martyn, chairman of the Juvenile Anti-Slavery Society, from its first meeting in Chatham Street Chapel in New York City. His remarks reflect the biblical hermeneutics outlined above and reiterate many of the same themes regarding the creation of Adam and race:

As with the “Anti-Slavery Catechism” above, this excerpt from the remarks of Martyn states that Adam was red like the clay from which Yahweh Elohim formed him. Similar to other exegetes before him, Martyn anchors this interpretation in the Hebrew language itself when he asserts that, “Adam means red clay.”You must not think, my dear children, that God loves you any more than he does other children because you are white. He did not make Adam white. He was red, some of the color of the Indians. Adam means red clay, and God formed him of red clay. Jesus was not white, but colored as the Asiatics are at the present day. If God had thought that white was handsomer or better than red or black, he would have made Adam white. But he does not think so. God regards conduct, not complexion. You should then treat colored children the same as you do white children. You should not avoid them, nor treat them ill. But love them, be kind to them, try to do them good. You should never be unwilling to read with them. Do them all the good you can, and remember that God is their father as well as yours.32

In another item, a dialogue between a father and a daughter, the imagery of dry, inert dust appears in contradistinction to creation in Genesis, and it is used to evoke the desecration of that creation by slavery: “God made man in his own image, and slavery tramples it into the dust. Slavery tries to undo what God has done, and what he called good. We see then that it is awful guilt.”33 Here, again, we see abolitionist rhetoric drawing upon the material discourse of the Hebrew Bible. Dust is set in stark contrast to the clay of creation and helps the writer make the point that slavery seeks to undo the creativity and workmanship of God himself. In the biblical account, God forms Adam from the moistened dust of the ground, working the raw earthen material into shape before breathing life into it. Slavery reverses this process and “tramples it into the dust,” effectively turning a human back into dry, inert raw material.

At the core of the interpretation of ʾădāmâ as red clay in The Slave’s Friend is an implicit argument about origins and value. As the first human created by God, Adam clearly reflects divine evaluation of race. As Martyn states, “If God had though that white was handsomer or better than red or black, he would have made Adam white.” This biblical account of racial origins does not treat whiteness as prima facie but as a later, post-biblical development.34 This is a significant interpretative move due to the common understanding of the distant past as a reliable—even divinely inspired—template for contemporary society, both in nineteenth-century theology and the Hebrew Bible itself.35 In other words, biblical origin stories are often taken as blueprints for divinely sanctioned social order. Thus, the stories of creation in Genesis enjoy a privileged status due to their early placement in biblical primeval history and, as we can see, are rich discursive sites for interpreters looking to root their arguments about race in the bedrock of biblical origins.

Biblical mythmaking in the nineteenth century, especially where it concerned slavery and racial hierarchy, was a hotly contested discourse, and the creation of Adam was no exception. Its use in both abolitionist and proslavery literature demonstrates both the potency and malleability of this myth in articulating a biblical taxonomy of race. When the “Anti-Slavery Catechism” quoted above refers specifically to Noah’s sons and their skin color, it implicitly undermines the proslavery argument about racial hierarchy that depended on the Curse of Ham. This is not the only occasion when the two biblical texts—the creation of Adam and the Curse of Ham—are pitted against each other. Proslavery writers also inherited a reading of Genesis 2 as the creation of Adam from red clay, and their treatments of the narrative had to adopt strategies that subordinated it to Genesis 9 and the racial hierarchy it was thought to uphold. In 1843, Josiah Priest published his book Slavery, As It Relates to the Negro, Or African Race, in which he offers a retelling of the biblical narrative that acknowledges the non-whiteness of Adam but undermines its use in abolitionist rhetoric:

Citing the work of Josephus, Priest grounds his interpretation of the creation of Adam in dubious Hebrew etymology, claiming that biblical word choice points toward a particular understanding of human origins and race. Here, he concedes the point that Adam was not white but red in color.First, ADAM, as above, signifies earthy man, red; second, ADAMAH, signifies red earth, or blood; third, ADAMI, signifies my man red, earthy, human; fourth, ADMAH, signifies earthy red, or bloody, all of which words are of the same class, and spring from the same root, which was Adam, signifying red, or copper color…Thus this Jewish historian, as well as the genius of the Hebrew language, furnishes us with a clue, like the golden thread in the labyrinth of the subterranean palace of ancient Thebes, leading to the right conclusion on this subject, namely, that Adam, with all the antediluvian race, were red or a copper colored people (Priest 1843, p. 16).

Priest goes on to say that the entrance of sin into the bodies of Adam and Eve changed not only their natures but also their complexion, turning it from red to the “dark hue of common copper.” He acknowledges and dismisses the antiquated claims that climate, geography, and certain habits are responsible for racial diversity among modern human beings. Instead, Priest argues, God himself interceded in the womb of Noah’s wife and changed the complexions of two of her sons, thus circumventing the laws of nature:

According to Priest, it was divine intervention that made Japheth white and Ham Black. Much like the discourse about Adam’s name and his supposed redness, Priest argues that the name Ham refers to his dark complexion: “The word Ham, in the language of Noah, which was the pure and most ancient Hebrew, signified any thing that had become black; it was the word for black, whatever the cause of the color might have been.”37 Priest attributes great authority to the word choice of Noah in naming his sons, at times referring to such language as the “true Antediluvian Adamic or Hebrew language” and “Noachian language,” the latter of which he claims is identical to ancient Egyptian in the time of Abraham (Priest 1843, p. 31). After all, he argues, biblical names reflect the nature of the persons or things they signify, distinguishing Hebrew from all other languages.God, who made all things, and endowed all animated nature with the strange and unexplained power of propagation, superintended the formation of two of the sons of Noah, in the womb of their mother, in an extraordinary and supernatural manner, giving to these two children such forms of bodies, constitutions of natures, and complexions of skin, as suited his will. Those two sons were Japheth and Ham. Japheth He caused to be born white, differing from the color of his parents, while He caused Ham to be born black, a color still farther removed from the red hue of his parents than was white, events and products wholly contrary to nature, in the particular of animal generation, as relates to the human race.36

The fact that Priest retells the creation of Adam in this way, shifting the focus from the red clay of creation to the Curse of Ham, is quite telling. It suggests an anxiety about the received interpretation of this story and its use in abolitionist theories about the biblical origins of race. While Priest must concede the point that Adam and his descendants were a “copper colored people,” based on the material imagery of Genesis 2, the novel scene he introduces into Genesis 9 effectively restores the balance of racial hierarchy in favor of his proslavery stance. Whiteness and Blackness, he asserts, are the direct results of divine intervention in this episode, rendering the racial politics of earlier passages moot. The malleability and mutability of clay make it a potent metaphor, allowing readers to play with different conceptions of human, racial, and subject formation. Writers engaged in the racial discourse of the nineteenth century tried to locate race in the Bible, and they sometimes found it in these myths of early human formation. As we can see from the exegesis quoted above, they adopt and adapt these myths in different ways, culminating in diametrically opposed taxonomies of race.

4. Conclusions

“Social formation by means of mythmaking is nothing other than the reasonable response to the inevitable social disruptions, contradictions and incongruities that characterize the ordinary human condition” (McCutcheon 1999, p. 206). The social dynamic of mythmaking McCutcheon describes helps make sense of the interpretation of the creation of Adam in nineteenth-century racial discourse in the United States. Amidst the growing tensions between abolitionist and proslavery forces, writers on both sides appealed to foundational myths—both biblical and national—to support their own taxonomies of race. This dogmatic appeal to origins is a hallmark of mythmaking. Implicit in this rhetorical strategy is the argument that these taxonomies are not new but rather date to the earliest periods of biblical (and human) history and, thus, serve as authoritative paradigms for modern racial hierarchies.

For those who sought to root their arguments in the moral authority of the Bible, it meant locating race in the biblical text itself. A common thread running through this discourse is the adjudication of what race actually is and where it originates. As I have argued throughout this essay, material imagery is often bound up with that discourse. Proslavery interpreters often resorted to the Curse of Ham in Genesis 9, arguing that the geographic dispersal of Noah’s descendants supported the racial distinctions of human populations around the world. In the case of the creation of Adam, the focus shifted to the color assigned to early biblical characters. In the hands of abolitionist writers, such as those featured in The Slave’s Friend, the red clay of Adam’s creation legitimates a reconfiguration of racial hierarchy that de-centers whiteness in the biblical narrative because Adam himself was red, not white. However, in the hands of proslavery writers such as Josiah Priest, the non-whiteness of Adam, while acknowledged, is subordinated to the Curse of Ham and the system of white supremacy associated with it. Yet, Priest’s retelling of biblical narrative suggests an anxiety about the prevalence and potency of the red clay myth and its resonance among those who preferred a literal, plain-sense reading of biblical scripture.

The non-whiteness of Adam in abolitionist literature such as The Slave’s Friend countered popular anti-Black etiologies in the antebellum United States and offered a new biblical paradigm for racial hierarchy, expressed in material terms. This essay has examined the dynamics of this hermeneutic, in which creation, race, and materiality are inextricably linked. By reading race materially, The Slave’s Friend turns an abstract category into something tangible and relatively familiar, especially in regions of the southeastern United States known for their abundance of red clay. As in the Hebrew Bible itself, the natural properties of clay lend themselves to discussions of identity and subject formation, which often rely on material metaphors for malleability. Thus, reading with material imagery helps us better understand the uses of the Bible in abolitionist race theory. The Slave’s Friend turns red clay into the stuff of biblical myth, one that depicts God’s formation of the first human being and lays the foundation for a taxonomy of race in the nineteenth century that de-centers whiteness and supports the emancipation of enslaved persons in the United States.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge those colleagues and students who offered invaluable feedback as I developed this essay. I am particularly grateful for the contributions of Rebecca Stephens Falcasantos, Ryan Harper, Sonia Hazard, Daniel Picus, Andrew Tobolowsky, and the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript. I owe special thanks to my students, especially Abigail Carson and Abigail Recko, and to Erin Rhodes and Erica Suttles in Special Collections & Archives at Colby College.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This particular name for the god of Israel, Yahweh Elohim, is uncommon in the Hebrew Bible. While it appears several times in the creation of Adam and the Garden of Eden narratives (e.g., Gen 2:4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22; 3:1, 8, 9, 13, 14, 21, 22, 23), it only appears once outside of these texts (Exod 9:30). As this formulation of the divine name is grammatically difficult, I have left it untranslated above and elsewhere in this essay. For a survey of scholarship on the epithet, see (L’Hour 1974, pp. 524–56). |

| 2 | For further discussion of the Curse of Ham and its history of interpretation, see (Haynes 2002; Goldenberg 2003; Johnson 2004; Davis 2008; Whitford 2009; Alpert 2013, pp. 29–41; Reed 2020; Schipper 2020, pp. 386–401). |

| 3 | The work of Nyasha Junior is instructive in analyzing the role of biblical interpretation in the subversion of anti-Black etiologies. See, e.g., Junior’s examination of the “mark of Cain” in Genesis 4 and its history of interpretation (Junior 2020, pp. 661–73). |

| 4 | Shoemaker (1997), “How Indians Got to be Red”, pp. 634–42. While the history of such discourse is beyond the scope of this essay, recent scholarship further explores the identification of Native Americans as Israelites and the political and religious implications of this association. See, e.g., (Fenton 2020; Dougherty 2021). |

| 5 | For a discussion of the category “myth” in the history of biblical scholarship, see (Oden 1987, pp. 40–91; Ballentine 2015, pp. 8–13). |

| 6 | This particular image serves as cover art for the vast majority of issues of The Slave’s Friend, appearing throughout Vol. 2 (1837) and most of Vol. 3 (1838), which the exception of No. 4. |

| 7 | Slave’s Friend II (12), 12; III (7), 9/10; II (2), 8. |

| 8 | For further analysis of the dynamics of gender and parental instruction in biblical wisdom literature, see (Crenshaw 1988, pp. 9–22; Crenshaw 1998, pp. 115–38; Newsom 1999, pp. 85–98; Vayntrub 2018, pp. 500–26; Petrany 2020, pp. 154–60). |

| 9 | In some cases, however, the dialogues in The Slave’s Friend subvert this convention and depict a precocious child who helps instruct their parent in the understanding of abolitionist principles. For instance, a dialogue titled “Little Daniel” features a young boy who asks permission from his father to go watch an abolitionist speak in public. When his father objects, the son points out the flaws in his father’s logic but, nevertheless, does not defy his father’s wishes (Slave’s Friend II [3], 10). |

| 10 | Slave’s Friend III (4), pp. 13–15. |

| 11 | Ibid., I (12). |

| 12 | Ibid., I (10). |

| 13 | Some versions of the hymn begin “Oh, happy is the man…” but the reproduction of the lyrics in The Slave’s Friend substitute “man” for “child,” as one might expect in a periodical meant for children (Hymn 1841). |

| 14 | I further examine this discourse of materiality and human formation in the Hebrew Bible elsewhere (“Thinking with Clay: Procreation and the Ceramic Paradigm in Israelite Religion,” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions, forthcoming). |

| 15 | Here, I follow Edward L. Greenstein’s interpretation of the Hebrew lipnê ʿāš (Greenstein 2019, p. 18, n. 31). |

| 16 | Greenstein suggests emending mēśîm, which he calls a “ghost-word in pre-Mishnaic Hebrew,” to mashayim, which is related to Arabic masāʾ (“evening”) and Late Hebrew ʾemeš (“last evening”) (Greenstein, Job, 18, n. 32). I have followed that suggestion here. |

| 17 | Like many translators, I am emending the MT here from yitrām to yitdām (“their tent pegs”), which seems to better fit the imagery of the surrounding passage. |

| 18 | Rabbinic commentary on Genesis also emphasizes Adam’s materiality by sourcing the dust of his creation from different parts of the world: his head (the land of Israel), his torso (Babylonia), his limbs (the rest of the world), and his buttocks (the outskirts of Babylonia) (b Sanhedrin 38b). In this case, the valuation of the dust and, by extension, its land of origin is then reflected in how that material is used to form Adam’s body. Much like the anthropomorphic statue in Daniel 2 with different parts made of different materials, the perceived value of those materials descends from the head downward. |

| 19 | Westermann (1984, p. 205). For an alternative reading, see Gerhard Von Rad’s comments on the role of water in this narrative: “Evidently the ʿēd rises up out of the earth. The meaning is that only ground water arose. Verse 6 is thus a sort of intermediary sentence which follows the negative details and precedes the positive ones…Water is here the assisting element of creation” (Von Rad 1972, p. 76). |

| 20 | HALOT vol. 1, 15, sub אָדֹם. |

| 21 | Haer 4.39.2. |

| 22 | Presley (2015, p. 165). For a discussion of similar tropes in the Dead Sea Scrolls, see (Frayer-Griggs 2013, pp. 659–70). |

| 23 | Later Christian writers continue to use material imagery to conceptualize early childhood development. For instance, Rebecca Stephens Falcasantos examines the “mimetic nature of education” and the malleability of the soul in John Chrysostom’s On Vainglory. In this treatise, John Chrysostom likens a child’s pliable soul to a wax writing tablet: “Should good instruction be impressed upon the soul while it is still soft, no one will be able to destroy these things when they have set firm, even as does a waxen seal” (Falcasantos 2020, p. 104). |

| 24 | Mather, 425. I have reproduced Mather’s own transliterations of the Hebrew terms above to reflect the emphasis on etymology in his commentary on Genesis. |

| 25 | Mather, 425. |

| 26 | “…the Eve of unborn generations, (and who singularly was so called from a Hebrew word, denoting the existence of all through her, while Adam merely took his name from the red clay, of which he was formed)…” (Anonymous 1838). |

| 27 | “You thought, at other times, of the first Adam, the stately man of red clay rising from the hand of the Almighty potter…” (Anonymous 1854). |

| 28 | Gesenius (1828, p. 14). My thanks to the anonymous reviewer who brought this reference to my attention. |

| 29 | Slave’s Friend I (5), p. 4. |

| 30 | Slave’s Friend I (7). |

| 31 | Ibid., II (5), pp. 13–14. |

| 32 | Ibid., II (5), inside cover. |

| 33 | Ibid., II (8), p. 8. |

| 34 | This understanding of whiteness is not consistent among abolitionist writers, however. For instance, in a sermon delivered in 1802, Alexander McLeod differs from the biblical interpretation of The Slave’s Friend in his assumption of the primacy of whiteness: “Ten times the number of years which have passed over the heads of the successive generations on the coast of Guinea, may be necessary before the negroes can retrace the steps by which they have proceeded from a fair countenance to their present shining black” (McLeod 1860, p. 28). Other scholars have also noted that rhetoric about Blackness and whiteness is inconsistent in The Slave’s Friend itself. Karen Sánchez-Eppler notes, for example, the “absurdly paradoxical rhetoric” in which blackness—where it refers to things besides skin color—is still associated with evil and set in opposition to whiteness, which signifies the good (Sánchez-Eppler 1988, pp. 28–59, 56–57, n. 40). Sánchez-Eppler points to a story titled “Apple and the Chestnut” in Volume 1, in which the narrator likens the moral development of children to the core of an apple: “Now little boys and girls can’t be abolitionists until they get rid of all these black grains in their hearts” (Slave’s Friend, I [2], p. 3). |

| 35 | David M. Carr makes a similar point concerning ideologies of the past in the Hebrew Bible: “[The distant] past is never ‘past’ in the way we might conceive it but stands in the ancient world as a potentially realizable ‘present’ to which each generation seeks to return” (Carr 2005, p. 11). |

| 36 | Priest, 27. |

| 37 | Ibid., 28. This etymological argument about Ham’s name and the origins of Blackness also appears in Mather’s commentary: “Cham’s name [implies] not only to become Hot, but also to become Black” (Mather, 438). |

References

- Alpert, Rebecca. 2013. Translating Rabbinic Texts on the Curse of Ham: What We Learn from Charles Copher and His Critics. In Re-Presenting Texts: Jewish and Black Biblical Interpretation. Judaism in Context 16. Edited by W. David Nelson and Rivka Ulmer. Piscataway: Gorgias, pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1838. Hints on a Cheap Mode of Purchasing the Liberty of a Slave Population. New York: G. A. Neumann. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1854. The Last of the Blennerhassetts. National Anti-Slavery Standard, February 25. [Google Scholar]

- Ballentine, Debra Scoggins. 2015. The Conflict Myth & the Biblical Tradition. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, David. 2005. Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castelli, Elizabeth A. 2004. Martyrdom and Memory: Early Christian Culture Making. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, James L. 1988. A Mother’s Instruction to Her Son (Prov. 31:1–9). In Perspectives on the Hebrew Bible. Edited by James L. Crenshaw. Macon: Mercer University Press, pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, James L. 1998. The Acquisition of Knowledge. In Education in Ancient Israel: Across the Deadening Silence. Anchor Bible Reference Library. New York: Doubleday, pp. 115–38. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Stacy. 2008. This Strange Story: Jewish and Christian Interpretation of the Curse of Canaan from Antiquity to 1865. Lanham: University of America. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, Matthew W. 2021. Lost Tribes Found: Israelite Indians and Religious Nationalism in Early America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Falcasantos, Rebecca Stephens. 2020. A School for the Soul: John Chrysostom on Mimēsis and the Force of Ritual Habit. In The Garb of Being: Embodiment and the Pursuit of Holiness in Late Ancient Christianity. Edited by Georgia Frank, Susan R. Holman and Andrew S. Jacobs. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 101–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, Elizabeth. 2020. Old Canaan in a New World: Native Americans and the Lost Tribes of Israel. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frayer-Griggs, Daniel. 2013. Spittle, Clay, and Creation in John 9:6 and Some Dead Sea Scrolls. JBL 132: 659–70. [Google Scholar]

- Geist, Christopher D. 1999. The ‘Slave’s Friend’: An Abolitionist Magazine for Children. American Periodicals 9: 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gesenius, Wilhelm. 1828. Hebräisches und chaldäisches Handwörterbuch über das Alte Testament, 3rd Improved and Expanded ed. Leipzig: Friedrich Christian Wilhelm Vogel, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, David M. 2003. The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein, Edward L. 2019. Job: A New Translation. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrill, J. Albert. 2000. The Use of the New Testament in the American Slave Controversy: A Case History in the Hermeneutical Tension between Biblical Criticism and Christian Moral Debate. Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 10: 149–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Paul. 2016. Christianity and Race in the American South: A History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, Stephen R. 2002. Noah’s Curse: The Biblical Justification of American Slavery. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, Samuel. 1785. A Dialogue concerning the Slavery of the Africans; Shewing It to Be the Duty and Interest of the American States to Emancipate All Their African Slaves. New York: Robert Hodge. First published 1776. [Google Scholar]

- Hymn, Anonymous. 1841. Heavenly Wisdom. In A Selection of Hymns and Psalms for Social and Private Devotion, 13th ed. Edited by J. P. Danbey. Boston: Munroe and Francis, p. 366. [Google Scholar]

- Ingelow, Jean. 1878. Thy Son, Adam, Was Red Clay. In One Hundred Holy Songs, Carols, and Sacred Ballads. Original, and Suitable for Music. London: Longmans, Green & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Sylvester A. 2004. The Myth of Ham in Nineteenth-Century American Christianity: Race, Heathens, and the People of God. Black Religion, Womanist Thought, Social Justice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Junior, Nyasha. 2020. The Mark of Cain and White Violence. JBL 139: 661–73. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Holly. 1996. Juvenile Antislavery Narrative and Notions of Childhood. In Children’s Literature, 24th ed. Edited by Francelia Butler, R. H. W. Dillard and Elizabeth Lennox Keyser. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 86–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kelso, James L. 1948. The Ceramic Vocabulary of the Old Testament. BASOR Supplementary Studies 5: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keralis, Spencer D. C. 2012. Feeling Animal: Pet-Making in the ‘Slave’s Friend’. American Periodicals 22: 121–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- L’Hour, Jean. 1974. Yahweh Elohim. Revue Biblique 81: 524–56. [Google Scholar]

- Levander, Caroline F. 2006. The Child and the Racial Politics of Nation Making in the Slavery Era. In Cradle of Liberty: Race, the Child, and National Belonging from Thomas Jefferson to W. E. B. Du Bois. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Bruce. 1992. Theorizing Myth: Narrative, Ideology, and Scholarship. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lowance, Mason. 2018. A House Divided: The Antebellum Slavery Debates in America, 1776–1865. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mather, Cotton. 2010. Biblia Americana: America’s First Bible Commentary. Genesis. Edited by Reiner Smolinski. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon, Russell T. 1999. Myth. In Guide to the Study of Religion. Edited by Willi Braun and Russell T. McCutcheon. New York: Cassell, pp. 190–208. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, Alexander. 1860. Negro Slavery Unjustifiable: A Discourse by the Late Alexander McLeod, D.D., 10th ed. New York: Alexander McLeod. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom, Carol A. 1999. Woman and the Discourse of Patriarchal Wisdom: A Study of Proverbs 1–9. In Women in the Hebrew Bible: A Reader. Edited by Alice Bach. New York: Routledge, pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Noll, Mark A. 2006. The Civil War as a Theological Crisis. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oden, Robert A. 1987. Interpreting Biblical Myths. In The Bible Without Theology: The Theological Tradition and Alternatives to It. San Francisco: Harper & Row, pp. 40–91. [Google Scholar]

- Petrany, Catherine. 2020. Fathers, Mothers, Sons, and Silence: Rhetorical Reconfigurations in Proverbs. Biblical Theology Bulletin 50: 154–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presley, Stephen O. 2015. The Intertextual Reception of Genesis 1–3 in Irenaeus of Lyons. The Bible in Ancient Christianity 8. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Priest, Josiah. 1843. Slavery, as it Relates to the Negro, or African Race: Examined in the Light of Circumstances, History and the Holy Scriptures: With an Account of the Origin of the Black Man’s Color, Causes of His State of Servitude and Traces of His Character as well in Ancient as in Modern Times: With Strictures on Abolitionism. Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500–1926. Albany: C. Van Benthuysen and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, Justin Michael. 2020. The Injustice of Noah’s Curse and the Presumption of Canaanite Guilt: A New Reading of Genesis 9: 18–29. Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton Theological Seminary, Princeton, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Susan M. 2000. Misgivings: Melville, Race, and the Ambiguities of Benevolence. American Literary History 12: 685–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Eppler, Karen. 1988. Bodily Bonds: The Intersecting Rhetorics of Feminism and Abolition. Representations 24: 28–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, Jeremy. 2020. Religion, Race, and the Wife of Ham. JR 100: 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, Nancy. 1997. How Indians Got to be Red. The American Historical Review 102: 625–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayntrub, Jacqueline. 2018. Like Father, Like Son: Theorizing Transmission in Biblical Literature. HeBAI 7: 500–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Rad, Gerhard. 1972. Genesis: A Commentary. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, Claus. 1984. Genesis 1–11: A Commentary. Translated by John J. Scullion, and S. J.. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Whitford, David M. 2009. The Curse of Ham in the Early Modern Era: The Bible and the Justifications for Slavery. Burlington: Ashgate Pub. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. 1969. Lewis Tappan and the Evangelical War against Christianity. Cleveland: Press of Case Western Reserve University. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).