Fortes in Fide—The Role of Faith in the Heroic Struggle against Communism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

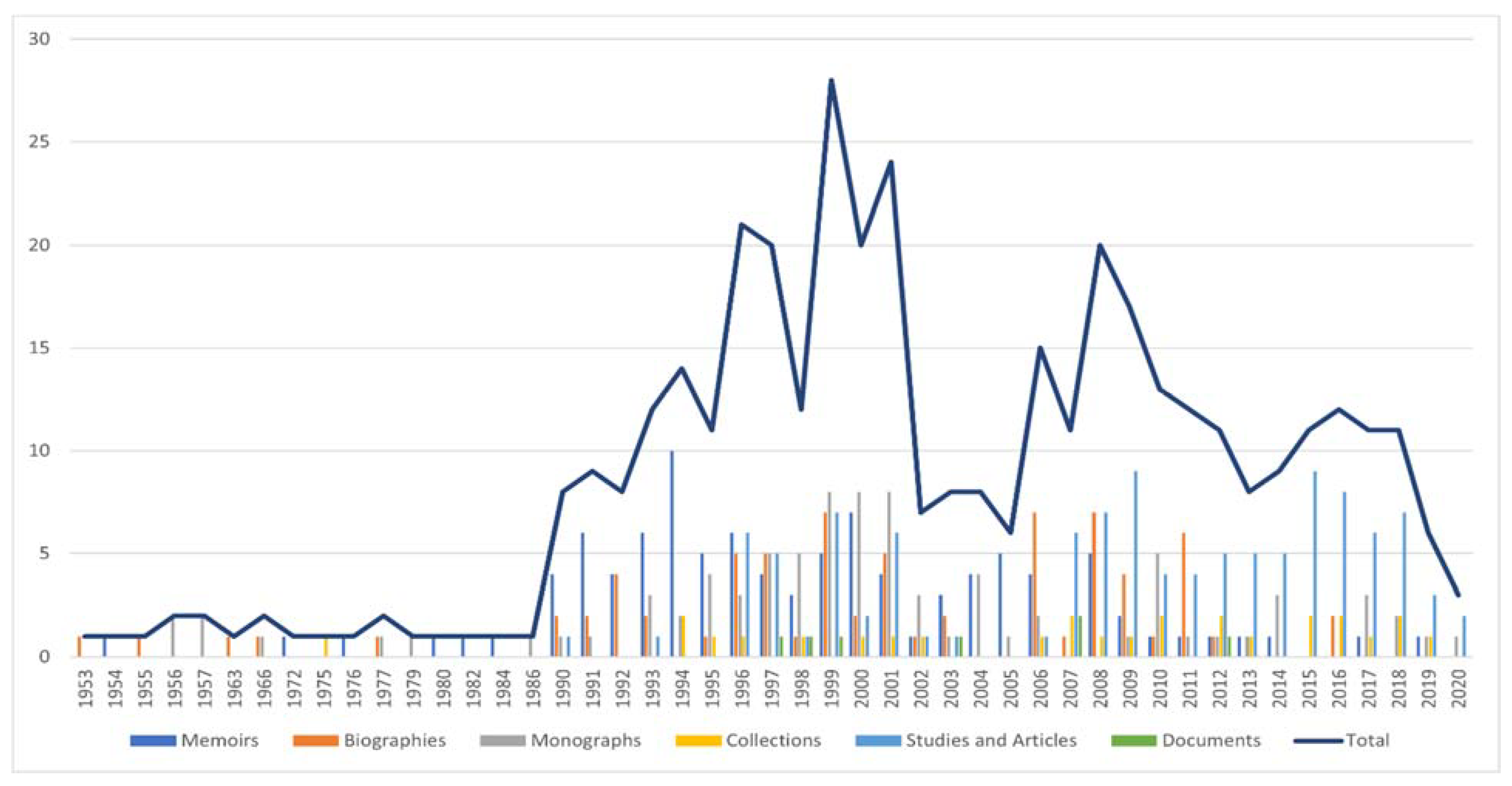

2. Methodology and State of the Art

3. Results

3.1. Witness, Martyrdom and Sacrifice

And so if I am about to be punished for what I did, i.e., for the good, the truth and Christ, then I do not want a lower penalty but rather a higher penalty and I would be the happiest person on earth if I could die for Christ—although I know I am not worthy of such a great grace. Therefore I do not wish to take advantage of any mitigating circumstances for myself just like I cannot apologize for doing what was good.

3.2. The Danger of Comfort

3.3. The Essence of Being Human

Once a political program turns into a philosophy or religion, when it tries to embrace human beings in their entirety, get hold of their soul and conscience while at the same time breach their fundamental freedoms, destroy spiritual values, trample on religion, dismiss God and coerce people to accept all of that, then it is the duty of the Church to defend the rights of both human and God’s laws.

3.4. Truth

3.5. Communion with God

I had the honour to meet him in Bratislava several times. Just like with Mother Theresa or Dorothy Day you know that you are walking in the presence of someone in whom God is present, someone who is able to do unusual things. Silvester Krčméry was surrounded by God’s presence, it was like some sort of radiation without the aura; you could sense it rather than see it.

3.6. Primacy of Faith

I believe it is determination in faith. The primacy of faith in one’s entire life and every action, courageous faith free of fear, hard-bitten faith through trials, faith brave enough to follow any God’s challenge—fortes in fide.

3.7. God’s Will and the Cross

While in prison we noticed that people of weak faith considered their years spent in prison as lost. But we as priests came to understand that we live in fullness exactly when we accept the path set for us by our Lord.

3.8. Faith as a Source of Support and Meaning

To put it simply, faith was the biggest support for me in my life. If I didn’t have it, I wouldn’t be here, that’s for sure. So let me be clear: without my faith in God, I would have to give up. The biggest help for me when I was in jail. It gave me certainty that everything has a meaning. If I didn’t have this hope, if I lost my faith, I would probably go for a rope around my neck.

3.9. Personal Maturity

All of them were spiritually balanced people with deep faith, they were highly educated and enjoyed natural authority. They were literally the best sons and daughters of our nation.

There was a fundamental difference between them [believers and non-believers] because (I think) the approach to life of these two groups was different even before. Believers were able to cope with their fate although, admittedly, they also may have suffered from temporary phases of depression and despair, but sooner or later they were able to overcome those and find their balance and act as a balancing factor for the community. As for non-believers, for them it was definitely more difficult to cope with all those things.

3.10. Humility

When he fell ill he told me he felt he was a weak Christian and a sinful man and asked me to pray for him so that Lord forgives him his sins. His confession was a real blow to me, even to the extent that I found the strength not to commit sins for a few days.

Over the five years following his release [Silvester Krčméry] managed to train three new professors—because he himself was only allowed to keep his doctoral title; but he did not become bitter about that—on the contrary, he continued sharing his knowledge with others. So three of his teammates became professors, another two doctors, and he sort of was left aside basically to clean the lab.

3.11. Internal Freedom

At times I was able to push through my ‘cause’ of being allowed to pray openly. For instance, I prayed while standing at the window with my arms outstretched, just for the matter of self-discipline, and also not to sort of ‘fall asleep’ or lose my focus, and also to train myself in courage... In those moments I had at least a bit of a feeling that I do not give in to those people; that I am really able to fight for a piece of freedom even here in prison, I was proud that I could offer [to God] something more than my loneliness or spiritual crises.

3.12. Indivisibility of Faith and Life

3.13. Driving Force of the Society

In Slovakia there exists no real alternative to Christianity; there is no ideological group that could compete with all those members of an array of vibrant religious circles, perhaps with the exception of that entropic mass of their consumerist peers who just hang and do nothing. Indeed, no ideological stream other than Christianity has a relevant base of engaged proponents—and least of all the communists.

3.14. Forgiveness and Reconciliation

The key to the solution of the ‘communist problem’ lies in forgiveness. Forgiveness does not suppress the pursuit of justice: through forgiveness, the moral essence of an act does not change. Evil remains evil. What is resolved though is some of the consequences of the evil act but more importantly, the relationship between the perpetrator and the victim changes fundamentally.

Love is the key, it has to be pure so that we faithfully endure, work together, suffer, and die for no less than our Lord. Let us love Him but let us not hate ‘them’. We can afford a victory without hatred.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The communist coup and takeover of power in Czechoslovakia took place as late as February 1948, but the communist crackdown on the church started to take effect immediately after the end of the war. |

| 2 | Common project of Catholic universities in Central and East Europe (Slovakia, Poland, Ukraine, Croatia, Georgia, Hungary) that is led by the Nanovic Institute at Notre Dame University, Indiana, USA. |

| 3 | T. Kolakovič was a priest from Croatia, but during his visit to Slovakia and the Czech Republic in the 1940s, he gradually gained reputation and influence and had a remarkable impact on the community of key figures within the circles of the anticommunist resistance, especially thanks to his role as a founder of the “Rodina” movement (The Family). |

| 4 | M. Gavenda is the youngest person on the list (b. 1963). Although he had adventurously fled the country in the late 1980s for Rome to become a priest, his main contribution consisted in his later extensive monograph, which was a scientific analysis of the Slovak church during communism, in which he discusses the secret formation of priests in the monastic orders and church communities (Gavenda 2014). The title of his monograph also inspired the title of this article. |

| 5 | Foucault regarded truth as something originating solely within “this world”. His rejection of the idea of “universal truth” in contrast to the Christian view is discussed in more detail in P. Polievková (Polievková 2013, p. 42). |

| 6 | Originally published in Náboženstvo a súčasnosť [Religion In Our Time], 3/1985, pp. 17–19. |

| 7 | As part of the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH) established by Ján Čarnogurský in 1990; the party remains a relevant political force in Slovakia to this day. |

| 8 | In 1987, A. Navrátil organized the famous 31-bullet petition for religious freedoms in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, which was also supported by Cardinal František Tomášek and signed by 600,000 people, half of them Slovaks. Previously, he was imprisoned inter alia for the distribution of an open letter about the insidious murder of the secret priest Přemysl Coufal by the state police. |

| 9 | Published as samizdat in Náboženstvo a súčasnosť [Religion in Our Time], vol. 1/1989, pp. 35–37. |

References

- Braxátor, František. 1992. Slovenský Exil 1968 [Slovak Exile 1968]. Bratislava: LÚČ. [Google Scholar]

- Čarnogurský, Ján. 1990. Väznili ich za Vieru [They Imprisoned Them for Their Faith]. Bratislava: Pramene. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, Jefferson R. 2019. The “on and off” of faith in hypermodernity: Religion and the new interfaces of the sacred in the media era. Espaço e Cultura 44: 9–30. Available online: https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/espacoecultura/article/viewFile/47351/31467 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Demko, Matúš, and Róbert Letz. 2014. Uniká nám oběť všedního života [We miss the victim of everyday life]. Katolický Týdeník 14. Available online: https://www.katyd.cz/clanky/unika-nam-obet-vsedniho-zivota.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Desrosiers, Kyle. 2020. Spiritual Reports from Long-term HIV Survivors: Reclaiming Meaning while Confronting Mortality. Religions 11: 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drda, Adam. 2020. Křesťan “kverulant” [Christian “querulist”]. Paměť Národa 12: 2. Available online: https://www.pametnaroda.cz/cs/magazin/pribehy/krestan-kverulant (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Gašpar, Tido J. 1998. Pamäti I [Memoirs I]. Bratislava: Vydavateľstvo Spolku Slovenských Spisovateľov. [Google Scholar]

- Gavenda, Marián. 2014. Fortes in Fide. Skúsenosť a Odkaz Tajnej Kňazskej Formácie na Slovensku v Rokoch 1969–1989 [Fortes in Fide. Experience and Legacy of a Secret Priestly Formation in Slovakia in the Years 1969–1989]. Trnava: Dobrá kniha. [Google Scholar]

- Gavenda, Marián. 2016. Spiritual challenges of the visual culture. In Expanding Media Frontiers in the 21st Century: The Impact of Digitalization upon Media Environment. Moscow: MediaMir, pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gavenda, Marián. 2017. Odkaz Tajnej Cirkvi [The Legacy of the Secret Church]. Bratislava: Don Bosco. [Google Scholar]

- Gazda, Imrich. 2012. Witnesses of Faith as a Key Element in Media Coverage of Religious Message. Studia Theologica 3: 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, John Elvis, Jr. 2021. Investigating Pre-competition Related Discrete Emotions and Unaccustomed Religious Coping among Elite Student-athletes: Implications for Reflexive Practice. Religions 3: 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmerová, Kristýna. 2020. S jeptiškami si komunisté nevěděli rady. Perzekuci přijímali jako dar a zkoušku víry [The communists could not cope with the nuns. They accepted persecution as a gift and a test of faith]. Paměť Národa 26: 7. Available online: https://www.pametnaroda.cz/cs/magazin/stalo-se/s-jeptiskami-si-komuniste-nevedeli-rady-perzekuci-prijimaly-jako-dar-zkousku-viry (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Hornig Priest, Susanna. 1996. Doing Media Research. An Introduction. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chňoupek, Bohuš. 1998. Memoáre in Claris [Memoirs in Claris]. Bratislava: Belimex. [Google Scholar]

- Kolakovič-Poglajen, Tomislav. 1993. Syntetický prehľad našej práce [Synthetic overview of our work]. In Profesor Kolakovič. Written by Václav Vaško. Bratislava: Charis, pp. 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Korec, Ján. 1987. Cirkev Uprostred Problémov. Niekoľko Pohľadov (Písané v Montérkach) [The Church in the Midst of Problems. Some Views (Written in Overalls)]. Samizdat: Slovenská Duchovná Služba. [Google Scholar]

- Korec, Ján. 1991. Od Barbarskej Noci II. Listy z Väzenia [The Night of the Barbarians II. Letters from Prison]. Bratislava: Lúč. [Google Scholar]

- Korec, Ján. 1993. Od Barbarskej Noci III. Na Slobode [The Night of the Barbarians II. At Liberty]. Bratislava: Lúč. [Google Scholar]

- Kováč, Dušan, Ladislav Bánesz, Juraj Bárta, Mojmír Benža, Martin Bána, Blanka Brezováková, Jozef Bujna, Viliam Čičaj, Juraj Činčura, Vojtech Dangl, and et al. 1999. Kronika Slovenska. 2. Slovensko v Dvadsiatom Storočí [Chronicle of Slovakia. 2. Slovakia in the Twentieth Century]. Praha: Fortuna Print & Adult. [Google Scholar]

- Krčméry, Silvester. 1995. To nás zachránilo. [This Is What Saved Us]. Bratislava: Lúč. [Google Scholar]

- Krčméry, Silvester. 2014. Pravdou Proti Moci. Príbeh Muža, Ktorého Nezlomili [Truth against Power. The Story of a Man They Didn’t Break]. Bratislava: Artis Omnis. [Google Scholar]

- Krčméry, Silvester. 2015. Vy máte moc, my máme pravdu [You hold the power, we hold the truth]. Postoj 10: 9. Available online: https://www.postoj.sk/5707/vy-mate-moc-my-mame-pravdu (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Krčméry, Vladimír. 2001. Vďaka za svedectvo i za zachránené deti [Thanks for the testimony and for the saved children]. In Liečiť zlo Láskou [Healing Evil through Love]. Written by Anton Neuwirth and Rudolf Lesňák. Bratislava: Kalligram, pp. 239–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kubíček, Ladislav. 2006. Božia vôľa–Zbožná Fráza? [God’s Will—A Pious Phrase?]. Bratislava: Karmelitánske Nakladateľstvo. [Google Scholar]

- Kusý, Miroslav. 1990. Na vlnách Slobodnej Európy [On the Waves of Radio Free Europe]. Bratislava: Smena. [Google Scholar]

- Lettrich, Jozef. 1993. Dejiny Novodobého Slovenska [History of Modern Slovakia]. Bratislava: Archa. [Google Scholar]

- Letz, Ján. 1996. Život v Hľadaní Pravdy. Vývin Osobnosti a Myslenia [Life in the Search for Truth. Development of Personality and Thinking]. Bratislava: Charis. [Google Scholar]

- Letz, Róbert. 2007. Osobnosť verzus moc [Personality versus power]. Pamäť Národa 2: 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lipták, Ľubomír. 1998. Slovensko v 20. Storočí [Slovakia in the 20th Century], 2nd ed. Bratislava: Kalligram. [Google Scholar]

- Mádr, Oto. 1992. Slovo o této Době [A Word about This Time]. Prague: Sofia. [Google Scholar]

- Mikloško, František. 2013. Znamenia Čias [Signs of the Times]. Bratislava: Hlbiny. [Google Scholar]

- Mittelman-Dedinský, Móric. 2001. Na Chrbte Tigra [On the Back of a Tiger]. Bratislava: A. Marenčin–PT. [Google Scholar]

- Neupauer, František. 2014. Pravda, ktorá má silu a odvahu [A truth that has strength and courage]. In Pravdou Proti Moci. Príbeh Muža, Ktorého Nezlomili [Truth against Power. The Story of a Man They Didn’t Break]. Written by Silvester Krčméry. Bratislava: Artis omnis, pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Neuwirth, Anton, and Rudolf Lesňák. 2001. Liečiť zlo Láskou [Healing Evil through Love]. Bratislava: Kalligram. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, Michael. 2014. Orly letia vysoko [The Eagles Fly High]. In Pravdou Proti Moci. Príbeh muža, Ktorého Nezlomili [Truth against Power. The Story of a Man They Didn’t Break]. Written by Silvester Krčméry. Bratislava: Artis omnis, pp. 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Ottmar, Vojtech. 1996. Podvratník [The Subversive]. Trnava: B-print. [Google Scholar]

- Palaščák, Jozef. 2006. Spravodlivosť a Pravda v Živote a Práci Otca Biskupa Jána Chryzostom Korca v Rokoch 1945–1989 [Justice and Truth in the Life and Work of Father Bishop Ján Chryzost Korec in the Years 1945–1989]. Prešov: Petra. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, John, II. 1993. Veritatis Splendor. Encyclical. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_06081993_veritatis-splendor.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Paul, John, II. 1994. Tertio Millennio Adveniente. Apostolic Letter. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_letters/1994/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_19941110_tertio-millennio-adveniente.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Paul, John, II. 2004. Vstaňte, poďme! [Rise, Let Us Be on Our Way]. Trnava: Spolok sv. Vojtecha. [Google Scholar]

- Polievková, Petra. 2013. Stereotypnosť ako podstata mediálneho politického diskurzu [Stereotyping as the essence of media political discourse]. Media i Społeczeństwo 3: 41–52. Available online: http://www.mediaispoleczenstwo.ath.bielsko.pl/art/03_Polievkowa.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Ratzinger, Jozef. 2005. Homily in the Basilica of St. Peter in Mass Pro Eligendo Pontifice (18. 4. 2005). Available online: http://papabenedettoxvitesti.blogspot.com/2009/06/santa-messa-pro-eligendo-romano_25.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Rončáková, Terézia. 2018. Východisko viery vo verejnom diskurze [Faithe as a Starting Point in the Public Discourse]. Studia Theologica 4: 113–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rončáková, Terézia. 2021. Faith and Freedom During Communism in Slovakia. An Analysis of the Literature Review and Two Notable Stories. Paper Presented at the Name of the Conference Trauma of Communism, Nanovic Institute, University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana, Online, June 29–July 1. To be published in the conference proceedings. [Google Scholar]

- Seewald, Peter. 2010. Svetlo Sveta. Pápež, Cirkev a Znamenia čias [Light of the World: The Pope, the Church, and the Signs of the Times]. Bratislava: Don Bosco. [Google Scholar]

- Svatošová, Mária. 2006. Čitateľ má právo dozvedieť sa [Čitateľ má právo dozvedieť sa]. In Božia vôľa–Zbožná Fráza? [God’s Will—A Pious Phrase?]. Written by Ladislav Kubíček. Bratislava: Karmelitánske Nakladateľstvo, pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Šimečka, Milan. 1990. Obnovenie Poriadku [The Restoration of Order]. Bratislava: Archa. [Google Scholar]

- Šimko, Ivan ml. 1994. Čas pravých činov [Time of True Deeds]. Bratislava: Charis. [Google Scholar]

- Šmid, Marek. 2012. Nauč nás pravej veľkodušnosti [Teach us true generosity]. In Silvo Krčméry. Edited by František Neupauer. Bratislava: Nenápadní Hrdinovia, pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tajovský, Bohumil Vít. 2009. Člověk Musí Hořeti. V Rozhovoru s Alešem Palánem a Janem Paulasem [One Must Burn. In an Interview with Aleš Palán and Jan Paulas]. Kostelní Vydří: Karmelitánské Nakladatelství. [Google Scholar]

- Tížik, Miroslav, and Milan Zeman. 2017. Religiozita obyvateľov Slovenska a Postoje Občanov k Náboženstvu. Demokratickosť a Občania na Slovensku II. [Religiosity of the Population of Slovakia and Attitudes of Citizens Towards Religion. Democracy and Citizens in Slovakia II]. Bratislava: Sociologický ústav SAV. [Google Scholar]

- Tkáčová, Hedviga. 2014. Postmodern challenge to the call to love “in truth and action”. In Whom, Why, and How One Ought to Love: Biblical and Theological Perspectives on Loving One’s Neighbor. Edited by Bohdan Hroboň. Mahtomedi: Vision Slovakia, pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Valčo, Michal, and Armand J. Boehme. 2017. Christian faith and science. Can science enhance theology? European Journal of Science and Theology 3: 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zemko, Milan. 2002. Slovensko–Krajina v Medzičase [Slovakia—A Country in the Meantime]. Bratislava: Kalligram. [Google Scholar]

| Genre | Total | Slovak Publications |

|---|---|---|

| Memoirs | 116 | 101 |

| Biographies | 73 | 73 |

| Monographs | 99 | 86 |

| Edited collections | 27 | 27 |

| Studies and articles | 128 | 112 |

| Documents | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 450 | 406 |

| Overarching Dimension | Category | Occurrences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Witness, martyrdom and sacrifice | 4 | |

| 2. | Philosophical | The danger of comfort | 4 |

| 3. | The essence of being human | 5 | |

| 4. | Truth | 2 | |

| 5. | Intimate | Communion with God | 6 |

| 6. | Primacy of faith | 7 | |

| 7. | God’s will and the Cross | 3 | |

| 8. | Faith as a source of support and meaning | 3 | |

| 9. | Personal | Human maturity | 3 |

| 10. | Humility | 4 | |

| 11. | Internal freedom | 3 | |

| 12. | Social and political | Indivisibility of faith and life | 2 |

| 13. | Driving force of the society | 4 | |

| 14. | Reconciliation and forgiveness | 4 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rončáková, T. Fortes in Fide—The Role of Faith in the Heroic Struggle against Communism. Religions 2021, 12, 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100837

Rončáková T. Fortes in Fide—The Role of Faith in the Heroic Struggle against Communism. Religions. 2021; 12(10):837. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100837

Chicago/Turabian StyleRončáková, Terézia. 2021. "Fortes in Fide—The Role of Faith in the Heroic Struggle against Communism" Religions 12, no. 10: 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100837

APA StyleRončáková, T. (2021). Fortes in Fide—The Role of Faith in the Heroic Struggle against Communism. Religions, 12(10), 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100837