Construction and Evaluation of an Educational Video: Nursing Assessment and Intervention of Patients’ Spiritual Needs

Abstract

1. Introduction

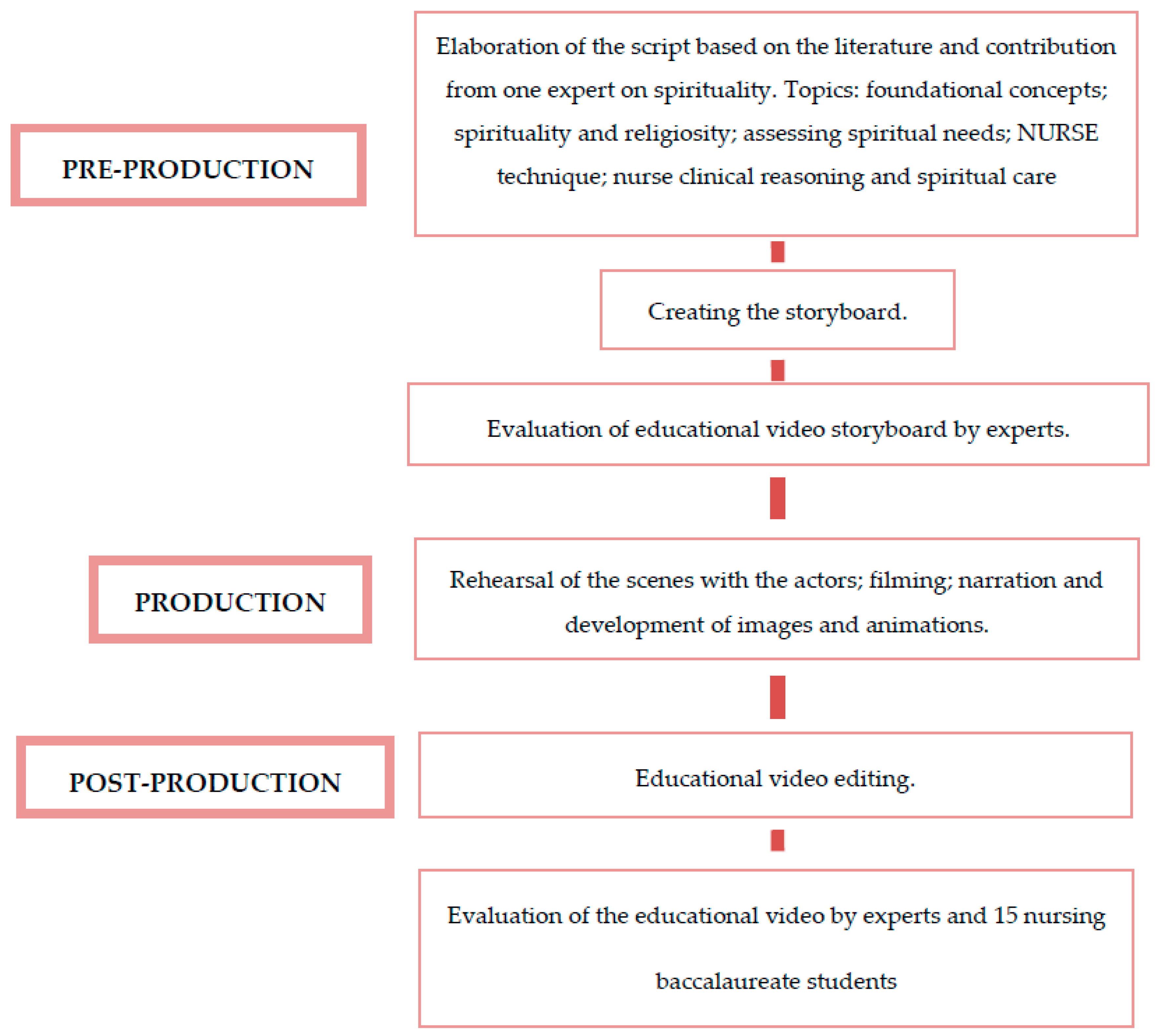

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pre-Production

2.2. Production

2.3. Post-Production

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Production

3.2. Production

3.3. Post-Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Back, Anthony L., Robert M. Arnold, Walter F. Baile, James A. Tulsky, and Kelly Fryer-Edwards. 2005. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 55: 164–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, Donia R. 2008a. Teaching on the spiritual dimension in care: The perceived impact on undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today 28: 501–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldacchino, Donia. 2008b. Teaching on the spiritual dimension in care to undergraduate nursing students: The content and teaching methods. Nurse Education Today 28: 550–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, Régia Moura, and Ana Karina Bezerra. 2011. Validation of an educational video for the promotion of attachment between seropositive HIV mother and her child. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 64: 328–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, Fernada Titareli Merizo Martins, Lívia Maria Garbin, Milene Thaís Marmol, Vivian Youssef Khouri, Cristiane Inocêncio Vasques, and Emília Campos de Carvalho. 2014. Oral hygiene in chemotherapy patients: Construction and validation of an educational video. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE On Line 8: 3331–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulechek, Gloria M., Howard K. Butcher, Joanne M. Dochterman, and Cheryl M. Wagner. 2016. Classificação das Intervenções de Enfermagem—NIC, 6th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier. ISBN 8535269878. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, Silvia, Amélia Simões Figueiredo, Ana Paula da Conceição, Célia Ermel, João Mendes, Erika Chaves, Emília Campos de Carvalho, and Margarida Vieira. 2016. Spirituality in the undergraduate curricula of nursing schools in Portugal and São Paulo-Brazil. Religions 7: 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Emília Campos. 1985. Comportamento verbal Enfermeiro Paciente: Função Educativa e Educação Continuada do Profissional. Ph.D. dissertation, Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; 225p. [Google Scholar]

- Corbally, Melissa Ann. 2005. Considering video production? Lessons learned from the production of a blood pressure measurement vídeo. Nurse Education in Practice 5: 375–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, Rocío de Diego, Bárbara Badanta Romero, Filomena Adelaide de Matos, Emília Costa, Daniele Corcioli Mendes Espinha, Claudia de Souza Tomasso, Alessandra Lamas Granero Lucchetti, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. 2018. Opinions and attitudes on the relationship between spirituality, religiosity and health: A comparison between nursing students from Brazil and Portugal. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27: 2804–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creative Commons Brasil. 2017. São Paulo: Creative Commons Brasil, c2001. Available online: https://br.creativecommons.org/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Espinha, Daniele Corcioli Mendes, Stéphanie Marques de Camargo, Sabrina Piccinelli Zanchettin Silva, Shirlene Pavelqueires, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. 2013. Nursing students’ opinions about health, spirituality and religiosity. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem 34: 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Susan E., Jerry Reynolds, and Barb Wallace. 2009. Lights … camera … action! a guide for creating a DVD/video. Nurse Educator 34: 118–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Neto, Nelson Miguel, Ana Carla Silva Alexandre, Lívia Moreira Barros, Guilherme de Moura Sá, Khelyane Mesquita de Carvalho, and Joselany Áfio Caetano. 2019. Creation and validation of an educational video for deaf people about cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 27: e3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Iván Darío Claros, and Ruth Cobos Pérez. 2013. Del vídeo educativo a objetos de aprendizaje multimedia interactivos: Un entorno de aprendizaje colaborativo basado en redes sociales. Tendencias Pedagógicas 22: 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanshahi, Maryam, and Maryam Amidi Mazaheri. 2016. The Effects of Education on Spirituality through Virtual Social Media on the Spiritual WellBeing of the Public Health Students of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in 2015. International Journal Community Based Nursing Midwifery 4: 168–75. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4876785/?report=classic (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Herdman, T. Heather, and Shigemi Kamitsuru, eds. 2015. NANDA Internacional Inc. Diagnósticos de Enfermagem: Definições e Classificações, 2015–2017, 10th ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed. ISBN 9781118914939. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Parra, Maria Rosa, Silvia García-Mayor, Shakira Kaknani-Uttumchandani, Álvaro Léon-Campos, Alfonso García-Guerrero, and José Miguel Morales-Asencio. 2016. Nursing students’ and tutors’ satisfaction with a new clinical competency system based on the nursing interventions classification. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge 27: 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harld G. 2012. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krau, Stephen D. 2015. Technology in nursing: The mandate for new implementation and adoption approaches. Nursing Clinics of North America 50: xi–xii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeros Lopez, Martha, and Emília Campos de Carvalho. 2006. La comunicación terapéutica durante instalación de venoclisis: Uso de la simulación filmada. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 14: 658–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- van Leeuwen, René, Lucas J. Tiesinga, Berrie Middel, Doeke Post, and Henk Jochemsen. 2008. The effectiveness of an education programme for nursing students on developing competence in the provision of spiritual care. Journal of Clinical Nursing 17: 2768–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Miriam, Ana Cláudi Silva, Angélica Maria Ferreira, and Aline Aparecida Costa Faria Lino. 2015. Narrative review on the assistance of humanization nursing team in the area oncologic. Revista Eletrônica Gestão & Saúde 6: 2373–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, Diego Marinho, Poliana Sales Alves, João Batista Bottentuit Junior, and Reinaldo Portal Domingo. 2014. Vídeos educativos no ensino superior: O uso de vídeo aulas na plataforma moodle. Revista Paidéi@—Revista Científica de Educação a Distância 5: 1–18. Available online: https://periodicos.unimesvirtual.com.br/index.php/paideia/article/view/268/353 (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Mckenny, Kassie. 2011. Using an online video to teach nursing skills. Teaching and Learning in Nursing 6: 172–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, Paulino Antonio Silva. 2016. Vídeo as empowerment for a critical digital art education. Revista Digital do Laboratório de Artes Visuais 8: 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Murakami, Rose, and Claudinei José Gomes Campos. 2012. Religion and mental health: The challenge of integrating religiosity to patient care. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 65: 361–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, Denise F., and Cheryl Tatano Beck. 2013. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, ISBN-10 1451176791. ISBN-13 978-1451176797. [Google Scholar]

- Ramezani, M., F. Ahmadi, E. Mohammadi, and A. Kazemnejad. 2014. A Spiritual care in nursing: A concept analysis. Internacional Nursing Review 61: 211–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reginato, Valdir, Maria Auxiliadora Craice de Benedetto, and Dante Marcello Claramonte Gallian. 2016. Spirituality and health: An experience in undergraduate schools of medicine and nursing. Trabalho, Educação e Saúde 14: 237–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Linda, Rene van Leeuwen, Donia Baldacchino, Tove Giske, Wilfred McSherry, Aru Narayanasamy, Carmel Downes, Paul Jarvis, and Annemiek Schep-Akkerman. 2014. A student nurses perceptions of spirituality and competence in delivering spiritual care: A European pilot study. Nurse Education Today 34: 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, Marcelo, Danilo Masiero, and Linamara Rizzo Battistella. 2001. Espiritualidade baseada em evidências. Acta Fisiátrica 8: 107–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, Benjamin E., Junaid Fukuta, and Fabiana Gordon. 2010. Live lecture versus video podcast in medical education: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Medical Education 109: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shores, Cynthia I. 2010. Spiritual perspectives of nursing students. Nurse Education Perspective 31: 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Natiele Favarão da, Natália Chantal Magalhâes da Silva, Vanessa dos Santos Ribeiro, Denise Hollanda Iunes, and Emília Campos de Carvalho. 2017. Construction and validation of an educational viedo on foot reflexology. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem 19: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroka, Jacek T., Lori A. Collins, Gary Creech, Gregory R. Kutcher, Katherine R. Menne, and Brianna L. Petzel. 2019. Spiritual Care at the End of Life: Does Educational Intervention Focused on a Broad Definition of Spirituality Increase Utilization of Chaplain Spiritual Support in Hospice? Journal of Palliative Medicine 22: 939–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmins, Fiona, and Silvia Caldeira. 2017. Understanding spirituality and spiritual care in nursing. Nursing Standard 31: 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaters, Elizabeth, Geraldine McCarthy, and Alice Coffey. 2016. Concept Analysis of Spirituality: An Evolutionary Approach. Nursing Forum 51: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, Nicola, and David Charnock. 2018. Challenging Oppressive Practice in Mental Health: The Development and Evaluation of a Video Based Resource for Student Nurses. Nurse Education in Practice 33: 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, J.C.; Miranda, T.P.S.; Fulquini, F.L.; Guilherme, C.; Caldeira, S.; Campos de Carvalho, E. Construction and Evaluation of an Educational Video: Nursing Assessment and Intervention of Patients’ Spiritual Needs. Religions 2020, 11, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090460

Rodrigues JC, Miranda TPS, Fulquini FL, Guilherme C, Caldeira S, Campos de Carvalho E. Construction and Evaluation of an Educational Video: Nursing Assessment and Intervention of Patients’ Spiritual Needs. Religions. 2020; 11(9):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090460

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Juliane Cristina, Talita Prado Simão Miranda, Francine Lima Fulquini, Caroline Guilherme, Sílvia Caldeira, and Emilia Campos de Carvalho. 2020. "Construction and Evaluation of an Educational Video: Nursing Assessment and Intervention of Patients’ Spiritual Needs" Religions 11, no. 9: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090460

APA StyleRodrigues, J. C., Miranda, T. P. S., Fulquini, F. L., Guilherme, C., Caldeira, S., & Campos de Carvalho, E. (2020). Construction and Evaluation of an Educational Video: Nursing Assessment and Intervention of Patients’ Spiritual Needs. Religions, 11(9), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090460