Abstract

What do god posters circulating online tell us about the practice of popular Hinduism in the age of digital mediatization? The article seeks to address the question by exploring images and god posters dedicated to the planetary deity Shani on Web 2.0. The article tracks Shani’s presence on a range of online platforms—from the religion and culture pages of newspapers to YouTube videos and social media platforms. Using Shani’s presence on the Web as a case study, the article argues that content drawn from popular Hinduism, dealing with astrology, ritual, religious vows and observances, form a significant and substantial aspect of online Hinduism. The article draws attention to the specific affordances of Web 2.0 to radically rethink what engaging with the sacred object in a virtual realm may entail. In doing so, it indicates what the future of Hindu religiosity may look like.

The power of digital media impinges on everyday life in contemporary times with ever-increasing scope and intensity. The unfolding COVID-19 pandemic has brought this fact into sharper relief than, perhaps, ever before. Needless to say, this enhanced digitality has also permeated the sphere of religion and religious rituals. How different religions reformulate ritual practices in the light of the pandemic and the theological and doctrinal implications of such reformulations is a topic for a different discussion. No doubt, such discussions are already happening and will take place increasingly in the days to come. What this extraordinary moment has allowed, however, is to retrain our attention on the mediated nature of religion. This understanding of technology as constitutive of religions and religious practices, what Jeremy Stolow calls “deus in machina”—God in and as the machine (Stolow 2013)—has come to stay with us for the foreseeable future.

Digital religion is a rapidly expanding academic field of enquiry. According to Heidi Campbell, at the most fundamental level, scholars of digital religion consider how “digital media is used by religious groups and users” for the propagation of religious doctrine and the abetment of religious practices. At the same time, scholars of digital religion also pay attention to the “reimagining of religion offered by unique affordances within these new media and spaces” (Campbell 2017, p. 16, emphasis added). When compared to Abrahamic religions, such as Christianity, Judaism and Islam, studies on Hinduism and new media technologies have been relatively sparse. Notable exceptions that exist focus on the use of new media by Hindu organizations, the performance of Hindu rituals online, particularly relating to online puja, broadcasting festivals, and the online congealment of different faith communities (Karapanagiotis 2010, 2013; Herman 2010; Scheifinger 2010). Within this body of scholarship, there is a broad consensus that online worship does not, and cannot, replace the ‘real’ thing for a range of reasons—spatial, embodied, as well as ontological. Digital religiosity, this body of scholarship contends, can operate only as a temporary and partial substitute for actual worship. However, as Stewart Hoover alerts us, we ought to remain wary of positions that either ‘essentialize’ or ‘particularize’ the relationship between digital technology and religion, where online religion serves either as a “poor substitute of actual and authentic role played by religion” or “stand[s] in for prior means of mediation” (Hoover 2012, p. 266).

Through its attention on Hindu religious imagery circulating online and over social media networks, this essay is a commentary on the operationalization of Web 2.0 in smartphone devices in India and the use of its interactive capacities in religious contexts. Within media and communication studies, Web 2.0 has three distinguishing features: “it is easy to use, it facilitates sociality, and it provides users with free publishing and production platforms that allow them to upload content in any form, be it pictures, videos, or text” (Lovink 2011, p. 5). In the early days of digital religion, scholarship on Hinduism online, for reasons that had to do more with digital infrastructure, was located primarily within diasporic Hindu communities and their use of the internet to access rituals, sacred spaces and specialized Hindu religious materials from their particular sect or region. Only very recently has scholarship on digital Hinduism being conducted from the vantage point of India (Zeiler 2020). Meanwhile, the rapid permeation in India of the cellular phone has massively widened the base of individual participation in processes of mass circulation of user-generated media in the last few years (Jeffrey and Doron 2013). In a scenario where market scale and competition render smartphone prices and data plan costs increasingly cheaper at the bottom end, it becomes imperative to track how digital affordances are transforming everyday religious practices in India, particularly since 2016.

Kathinka Froystad in her study of the rapidly transforming realm of information and communication technologies in the city of Kanpur in north India notes that “smartphones were often [the] very first introduction to the internet” for most young men, and women, from working-class contexts (Froystad 2019, pp. 125–26). Froystad notes that in 2017, India had 432 million internet users of which 300 million were smartphone owners (Froystad 2019, p. 124). This peculiar infrastructural aspect accounts for much of the vast difference between online manifestations of faith in the diasporic Hindu digital arena and the same in India. It indicates why similar concerns regarding purity, authenticity, and community around the use of digital devices for religious purposes that are so consequential within diasporic Hindu contexts are not key concerns with regard to Hindu online practices in India. Instead, cultures of virality, that form a significant component of online activity with respect to a smartphone device, emerges as a key practice. It is this aspect of interactive online religiosity that I explore further in this paper. The social structures and economic arrangements consequent of digitalization of information and communication technologies—what Manuel Castells calls ‘network society’ (Castells 2004)—make this moment a decidedly new one with regard to religion as well. Media convergence and intermediality, interactivity and hypermedia, virality and amplification of content that is as much curated as it is spontaneous, new cultures of work and leisure enabled by networked devices, etc., have significantly reconfigured the matrices and modalities of religious practice. These new forms of religious participatory and virality cultures are both products of and processes that characterize web interfaces that exploited and realized the full potential of Web 2.0—social media networks, such as Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, WhatsApp, TikTok, or ShareChat, the platform that I focus on in this paper.

In the context of expanding techno-medial frontiers and Hinduism, the bulk of the existing scholarship deals with the vocal and aggressive presence of Hindu right wing content on the web, with the so-called ‘internet Hindus’, with their hate-speech, misinformation, and the politics of offense (Gittinger 2015; Mohan 2015; Udupa 2018; Banaji 2018). One of the lesser explored aspects in this article is digital publics. A focus on digital publics will allow us to re-interrogate the purported ‘split publics’ of analog media (Rajagopal 2001) from a digital perspective and invite us to think how devotional content often operates infrastructurally for political content. While it is undoubtedly difficult to cleanly parse out piety from politics, devotion from power relations, and belief from identity at all times, it remains necessary to not reduce the plethora of online Hindu content to its most extreme, i.e., hate-speech of religious right wing groups, organizations, and bots. In other words, while recognizing the importance of this scholarship in mapping and critiquing how Hindu religious content online often dovetails with majoritarian extremism in the Indian context, I suggest that it is as important to look beyond an all-exhaustive hermeneutic of suspicion in interpreting such content.

1. Research Method and Ethics

This article analyses images of Hindu divinities that circulate over various digital social media networking platforms. It seeks to understand the source of their sensual charge and the formal elements they deploy to excite and affect the sensorium. The primary virtual ‘site’ of my research is ShareChat—a social media platform that operates in a variety of Indian regional languages. The platform is popular amongst tier 2 and 3 cities in India, and amongst India’s vast vernacular language publics. I limit myself to online content that is primarily user-generated and participatory. Content shared on the specific platform that I focus on often ‘goes viral,’ i.e., it is ‘seen,’ ‘liked,’ and ‘shared’ multiple times by users over more than one platform. The platform itself allows for content to be shared directly over WhatsApp. For the purposes of this article, I focus on god posters dedicated to Shani that circulate on this platform, and on other public online sites, such as YouTube.

Given the subject matter of my study, i.e., digital god posters or Hindu memes on a regional language social media platform, I had to make certain important decisions regarding two key issues related to social media research. One, the question of intellectual rights and two, the question of privacy and anonymity. In its technical aspects, a digital god poster is an image macro, i.e., an image superimposed with some kind of a text. Image macro is a technical term for what we currently in everyday conversation understand to be internet memes, “a piece of culture…which gains influence through online transmission” (Davison 2012, p. 122). In common-sensical understanding, as well as in scholarship, memes refer primarily to humorous content. However, image macros that seek to involve themselves in other kinds of affect than satire, humor, ridicule or disgust—those that speak of love, piety, or simply good wishes—are also ubiquitous on social media. Hindu god posters online can be understood to circulate as memes of the non-humorous kind. Davison argues that internet memes are defined by their lack of attribution—an aspect quite clearly discernible in the circulation of Shani images online that I have been examining. Authorship and copyright are almost impossible to track down, and the same set of images are often variously montaged together to produce new religious memes. Davison contends that non-attribution is a generative feature of the internet meme and affords it the replicability and virality that is necessary for its continuation. In their non-attribution, god posters online are similar to devotional poetry from the Bhakti period, where the question of authorship remained secondary to the act of transmission.

In late October/early November 2019, my research assistant, Neeta Subbiah, and I archived a total of 53 images of Hanuman and Shani, both individually as well as together, that were being regularly circulated on the Indian social media platform and file sharing app, ShareChat. Our choice of deity and the social media app were both informed by what we had set out to study—i.e., the prevalence of different aspects of popular Hinduism online and what that can tell us about the intersection between religion and new media technologies in contemporary India. Given this interest, we found the peculiar intersection of Shani, the malevolent deity, and ShareChat, a uniquely Indian social media app optimized for use on an android smartphone, to be particularly propitious for our purpose. Our choice to focus on this particular social media platform was informed by its decidedly user-driven content, easy shareability as an affordance built into the app, and its popularity amongst non-English speaking users in India.

Despite the rich archive of digital god posters dedicated to Hanuman and Shani that we produced, we soon realized that in the absence of tracing copyright, it would be impossible to use these images in either an academic or any other forum. These images, however, are stock images that circulate not merely on ShareChat and through it, but on WhatsApp. They also accompany online news reports, blogs, and articles on popular Hinduism, especially on the topic of vows and observances in honor of Shani. Similarly, the same images are often used in multiple YouTube videos on the legend of Shani and instructions on how to worship him. Given this dense intermedial exchange and media convergences of Shani’s images online, I decided for the purposes of this article, to use only those images that are available publicly on the internet. Each one of the images I use here, however, has been used to produce a god poster and an image macro and ‘shared’ on ShareChat.

The main theme of my article revolves around the question: how have various aspects of popular Hinduism adapted to the digital turn in religion? Given their highly localized circulation, the strong presence of priestly intermediaries, the often variegated myths and legends associated with these deities, and the absence of a prominent, representative institution or organization, how have these regional Hindu deities fared online? Even a cursory glance at vernacular Hindu content online, particularly on apps and other file sharing, social media sites, immediately reveals that a vast amount of this comprises locally prominent, secondary, and tertiary deities. That is, those deities which Philip Lutgendorf in his study of Hanuman calls mid-level, mediating divine beings. Deities who are seen to occupy the space between the human world and the world of the Great Gods. In order to exemplify this contention regarding quotidian Hindu religiosity on vernacular social media networks in India, I explore and analyze the online life of such a deity—the powerful but malevolent Shani. However, to properly appreciate the specificity of Shani’s digital dwelling, it is necessary to briefly situate him in his pre-digital context.

3. Shani and Popular Hinduism on Web 2.0

A bricolage of images, borrowing from older traditions of chromolithographs, photographs, as well as the cinematic image, make up for a majority of Hindu devotional content that circulates online. However, every Saturday, Shani lords over the Internet. His images proliferate on ShareChat as well, accompanying the day-specific greetings, under the hashtag shubh Shanivar (‘have an auspicious Saturday’) or jai Shani Maharaj (‘Hail Lord Shani’). These images can be broadly bunched under three categories: one, images of Shani alone; two, images of Shani alongside another Hindu deity, mostly Hanuman, and sometimes Shiva, and three, images of Shani’s shrine. The last ones overwhelmingly are of the aniconic black stone Shani image from the Shingnapur Shanidev temple in Ahmadnagar district, Maharashtra (Figure 2). The anthropomorphized images, however, are less concerned with established textual and iconographic fidelity and more indebted to popular perceptions of and legends associated with the deity.

Figure 2.

Aniconic Shani from Shingnapur Shanidev Temple. Source: Zee News.

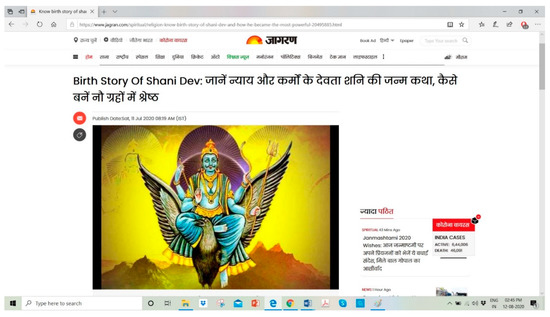

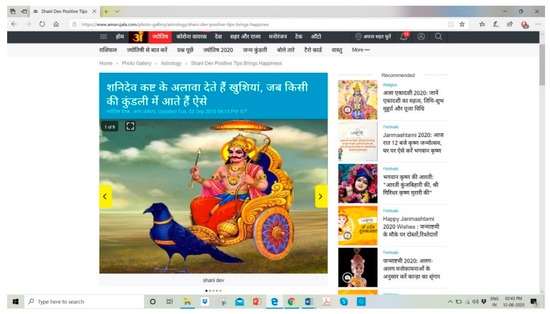

Apart from the aniconic stone image from Shingnapur, two kinds of Shani imagery is most popular (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The first one draws upon the horror sensorium to depict Shani in greyish blue tones, riding on an oversized, frightful crow, his eyes turned upwards (Figure 3). Shani’s legend shows him to be favorably disposed towards the color black. Hence, the use of darker shades is not unusual. However, this image also actively builds upon popular depictions of horror, in cinema and graphic novels, for the effect of fearsomeness it wishes to induce amongst its viewers. The second one depicts him in bright colors, often blue and red, sporting a golden crown—no different from other generic Puranic deities (Figure 4). It reminds us, Judy Pugh notes in the context of printed posters of the navagrahas, that ‘popular iconographic illustrations mute, even obscure the planets’ malevolent dispensations’ (Pugh 1986, p. 56).

Figure 3.

Shani riding the crow. Source: Jagaran.

Figure 4.

Shani riding a golden chariot. Source: AmarUjala.

These three figures form the bulk of Shani imagery that circulates online. They are then digitally modified, montaged, and turned into god posters and internet memes by users that circulate richly each Saturday (Figure 5). At times, Shani’s planetary aspect is closely integrated into the overall representation (Figure 6). This is done by drawing upon existing cosmic kitsch, easily available for use as a background in a montage. At other times, a more pastoral aesthetic is preferred (Figure 7). Media convergence and modularity that digitalization affords means that images from the print era down to the absolutely contemporary figural representations of Hindu deities in graphic novels—all can be found circulating on social media platforms. However, most content is basic in its production quality and can safely be characterized as digital kitsch, characterized by its ‘cheap…repetitive and imitative’ aspects (Jain 2007, p. 173).

Figure 5.

Shani montage and meme. Source Patrika.

Figure 6.

Shani with a pastoral background. Source: Times Now Digital.

Figure 7.

Shani with cosmic kitsch background. Source: ABP Digital.

Shani imagery in bazaar art, Pugh argues, rests upon a conscious ‘semeiotic heterogeneity’ whereby his malevolence and his power remain ambiguously intertwined with each other. This kind of heterogeneity can be seen most clearly in his vehicle—a black buffalo, otherwise reminiscent of Yama, the god of death, but which was often mistaken by devotees to be the bull associated with Shiva (Pugh 1986, p. 59). Digital images of Shani, which can be seen as transposition of the printed image on the digital medium, continue with this kind of semeiotic dissimulation and plurality. Anthropomorphized images often correspond closely to his mythical status as a navagraha with a fearful countenance and ability to do harm. The ‘ambiguous’ counterpart of such images are those that depict him as a solemn and just judge, handing out commensurate punishments for one’s sins. The harbinger of unbridled maleficence and misfortune, which is how Shani is understood in Hindu astrology, sits uneasily with cheery Saturday greetings that occasion the circulation of his image on ShareChat. Hence, his malefic, vindictive aspects are often mitigated by a gentler representation.

The presence of Shani on social media is especially aimed at ritualistic Hindu audiences. Although the images are not worshipped in the same fashion as one would conduct at a regular temple or domestic altar. These images indicate that the digital medium is a unique platform for the extension and continuation in new forms of various aspects of popular Hinduism. Central to this is the scope of ‘play’ that the technology affords. Digital images can be tagged with metadata, linked with hypertexts, superimposed with salutations and propitiations, and discussed in ‘below the line’ comments. They invite and produce virtual participatory cultures of religiosity amongst people who may otherwise never encounter each other. The engagements are of what social media theorists, following the lead of anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski, call ‘phatic’ communication (Radovanovic and Ragnedda 2012; Boyd 2012). This type of communication maintains social engagement without conveying meaning or substance. Most images, thus, are followed by repetitive comments such as ‘jai shani maharaj’ or ‘shani dev ki jai’ that seek to reinforce the primary message.

That online images buttress offline ritualized activity, rather than replace it in any fashion, is evidenced by the kind of information that sometimes accompanies the image. Thus, one can find posters containing dense narratives and legends, instructions to worship, as well as contact numbers of pandits, astrologers, and other ritual specialists who could potentially help users with a puja or some other religious task. One such poster circulating on ShareChat urges viewers to worship Shani to get rid of their problems under the hashtag #we_solve_all_your_problems. The ‘problems’ too are clearly mentioned and consist of challenges in love and marriage as well as professional rivalries and set-backs. Sometimes, such posters even mention names of the specific pujas that can be conducted, and their purpose and efficacy. A single digital poster is, thus, able to carry out multiple functions—sacred as well as secular.

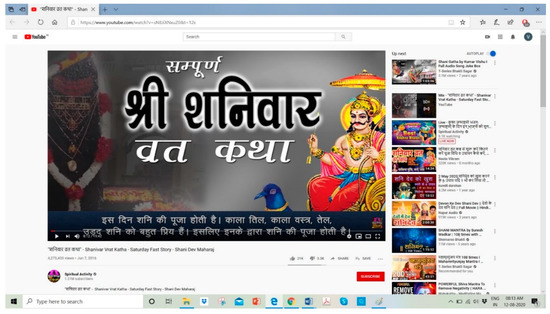

Digital religious content often facilitates intermedial conversations that lead to important kinds of media convergences. These convergences fundamentally define contemporary religious publics in India that simultaneously circulate over multiple digital platforms while having access to other mediated forms of the same content. What existed in an older media form (i.e., print and analog) passes into new (digital) media, now armed with new affordances. For instance, a popular YouTube channel, Spiritual Activity, dealing with Hindu rites and rituals with 1.2 million subscribers carries a video narrating Shani’s vrat katha (Figure 8).5 Similarly, the religion, culture, and lifestyle supplements of regional language and English newspapers also carry articles on Shani’s legends on certain days associated with this deity. Such content may be in addition to chapbooks and ritual manuals, calendar art images, and other such ephemera that Shani-afflicted Hindus may have in their homes. To wit, on 1 August 2020, Navbharat Times, Patrika, and Jagaran—some of the most popular Hindi dailies in India—all carried Shani’s vrat katha.6 This date was particularly significant for Shani worshippers. It marked the thirteenth day of the month of shravan in the lunar calendar when observances and austerities are customarily undertaken in the honor of Shiva to mitigate accumulated sins (pradosh vrat). However, on this occasion, the date happened to fall on a Saturday—the day of Shani. The day, thus, turned into Shani trayodashi, when, according to legend, Shiva himself fasted to propitiate Shani. In recognition of this compounded ritual significance, the day’s newspapers urged readers to additionally read Shani’s vrat katha if they were keeping the pradosh vrat.

Figure 8.

Screenshot of YouTube video ‘Sampoorna Shanivar ki vrat katha’ by the YouTube channel Spiritual Activity, with 1.2 million subscribers.

The Shani vrat katha, like other similar kathas that depict a cycle of misfortune followed by a happy ending, are not new in the Hindu context. We find many such vrat kathas, often addressed to a ‘regional’ deity, such as Shitala, Manasa, Shashthi, Santoshi Ma, or Satyanarayan, to name a few from the north and eastern Indian Hindu religious context (Wadley 2005). The pattern of storytelling in these kathas invariably follows the (mis)fortunes of a wealthy, upright, god-fearing, and moral human being who is punished for failing to pay attention to a particular deity or for her/his arrogance stemming from their successful status. Often, the misfortune is a result of facing the ire of a non-primary Hindu deity. Social media platforms like ShareChat are typically ill-suited to host long narrations of such legends in entirety—the latter circulate extensively on audio–visual content sharing platforms, such as YouTube. However, the images that circulate on all these different platforms provide pictorial or mnemonic prompts to Shani posters that also circulate on these and other platforms (Figure 6). Repetition is key, both oral–aural repetition as well as pictorial and mnemonic one. The poster, thus, serves as a metonym for the legend, which also interpolates users undergoing some or the other kind of personal misfortune.

This indexicality is mutually legible across different apps and social media platforms. For example, the images that accompany the narration of a Shani legend on YouTube are either the same or similar to the ones that circulate on ShareChat on Saturdays. Conversely, the latter is a clue to a specific Shani legend, whose audio narration one can search for and identify on YouTube.

The online presence of Shani, thus, is a powerful reminder that popular Hinduism in the form of local deities, special vows, vrat kathas, and astrology finds new pathways to remain relevant in the present times. It alerts us to dimensions of online sacrality that have remained understudied thus far. We see that digital affordances of Web 2.0, especially as a result of convenient access to the smartphone, inexpensive data plans, apps, and social media platforms that target a regional language user base, make it possible for deities, such as Shani, and the entire edifice of popular Hinduism that comes with it easily accessible on the digital medium. As noted by Arvind Rajagopal in the context of cinema and television, here too the mediated public is a strongly religiously informed one (Rajagopal 2001).

4. Virtuality, Virality, and Digital Corpothetics: Online Images of Hindu Deities

The divine image has a unique provenance within the sensorium of Hindu religiosity. No discussion of media, religion, and modernity in India has remained impervious to the presence and power of the image across a historical range of media—from sculpture and iconography to print, film, television, and the internet (Davis 1997; Pinney 2004; Rajagopal 2001; Jain 2007). In this section, I interrogate the circulation of Hindu images on the digital medium within the related frameworks of performance, embodiment, and (im)permanence to understand where, if at all, the sacred charge of these images lie. Ritually consecrated Hindu images are ‘animate beings’ (Davis 1997, p. 7). Can this vitality be translated onto the digital medium? What kinds of performative acts would be needed for digital images to be rendered ‘animate?’ What role does media sensorium play in the process of animating an image—virtually, as well as ontologically? Moreover, how long does its animated charge last on the digital medium? These questions become particularly significant to ask in the present context, because the digital image in its virtuality marks a definitive transformation from older forms of Hindu images.

Hindu images are evidence of ‘concrete theism’ (Waghorne 1985, p. 2). The ritual of puja is ‘the basic formal means by which Hindus establish relationships with their deity’ (Courtright 1985, p. 33). Hindu idols, variously called murti, pratima, or vigraha¸ go through the process of formal consecration whereby a priest ritually ‘establishes’ the image after which the idol is no longer merely a representation of the deity; it now is the deity. Scholars have argued that the act of worship or puja remains central to the production and circulation of Hindu images over a variety of mediascapes—from stone and metal images that can be consecrated to god posters that often hang in homes, offices, and vehicles. In his analysis of posters of Hindu gods, Daniel Smith notes that the primary purpose of these images was to be displayed in ‘places of honor, often wreathed with flower garlands’ (Smith 1995, p. 24). The puja ritual engenders a particular kind of relationship between the deity and the devotee that is repetitively reproduced—often on a daily, weekly, monthly, or annual basis. The act of worship is a performative and embodied act involving a vast sensorium including visual, oral-aural, tactile, and olfactory dimensions. Darshan or exchange of the gaze is one of the most important aspects of puja, fostering that special connection between deity and devotee (Eck 1998). Darshan privileges the visual component of Hindu devotional sensorium and is also the most easily translatable across various kinds of visual media. Philip Lutgendorf had, thus, argued that the act of darshan lay at the heart of the popularity of the television Ramayana. The Ramayan ‘was a feast of darsan … conveyed especially through close-ups’ (Lutgendorf 1995, p. 230).

However, is it possible to imagine lives of Hindu images outside of their ritual purpose? The easy and cheap availability of lithographs and chromolithographs since the late nineteenth century have ensured that not all divine images have been considered sacred. Some, as a result of their ‘mechanical reproduction’ as commodity objects are rendered into ephemera and excess before they can attain a sacred charge. Media anthropologists like Kajri Jain remind us of precisely such a dimension when considering the mass production of Hindu images used in and as commercial posters, greeting cards, advertisements, and bazaar and calendar art. Jain argues that in the context of such mass produced images, the god image circulates more as a commodity than a sacred object (Jain 2007). Jain, however, draws a distinction between god posters as commodity object, such as advertisements and calendars, and in bazaar prints, where they are more likely to be used for worship. Hence, in her analysis of god images circulating in the largely vernacular marketplace, the performative act of worship or puja retains its centrality. Puja differentiates between god posters circulating as a sacred image and a commodity object. The ontological (theological) is, thus, mediated by the performative and the embodied (ritual).

Digital god posters are in many ways no different from printed god posters. Some are downloaded and kept on one’s devices; others are made into screensavers, while a large number of them simply disappear into a virtual cloud after the most perfunctory and phatic engagement. At times, these online posters may be used for ritual worship, although arguably that is not their primary usage. What, then, explains the dense circulation of these images and posters in the digital public sphere in India? If these posters do not operate as sacred objects, what is their purpose? In looking for answers to these questions, I propose we turn to performative acts vis a vis specific kinds of images. Thus, for instance, an image situated at a domestic altar or at a temple’s sanctum requires pranapratishtha (consecration) as its primary performative act, followed by the ritual of daily puja. A chromolithograph on a calendar, or an offset print in the form of a greeting card, on the other hand, is meant to be distributed and circulated. Only in certain specific contexts does it assume a sacred charge, if the user or receiver of the image chooses to attribute divinity to it—again through performative acts. The type of performative acts that define engagement with digital posters is fundamentally different from printed images and posters. Digital acts assume a radically different type of embodiment—an embodiment that primarily depends upon the use of fingertips on a digital device and a heightened audio-visual sensorium.

It is possible to argue that the mediated forms of divinity in the Hindu context have progressed from permanence to impermanence over the long arc of history. With the appearance of ‘new’ forms of media, and the shift from stone and metal to print, cinema, and more recently the digital, we are able to discern a move from long-lasting materials to make the sacred image to less durable and impermanent materials. Nonetheless, it is also important to remember that idols were, and continue to be, constructed out of material that could easily decay and decompose. This practice can be seen today in the context of annual, recurring public festivals, such as Durga Puja in West Bengal and Ganesh Puja in Maharashtra. Idols are especially made for these kinds of festivals, consecrated for worship, and ritually immersed in water bodies at the end of the period of worship. Similarly, in the context of the printed image, there is no dearth of sacred ephemera—often seen in the form of abandoned prints and photos underneath tress, or floating pitifully in lakes and other water bodies. Such close association with a cyclical and recurrent process of ritually re-establishing the divine image leads James Preston to conclude that impermanence is fundamental to the Hindu relationship to divinity and its material forms (Preston 1985, p. 12). Is it possible, then, to think of about virtuality as yet another dimension of impermanence? According to Geert Lovink, impermanence is characteristic of Web 2.0 since ‘the object of study is in a permanent state of flux and will disappear shortly—the death of everything cannot be denied’ (Lovink 2011, p. 7). Unlike the comparably longer life of the printed image, the digital image is marked by its transience, especially in relation to the user–subject. For while it is true that nothing really ever decays or dies on the internet, virtual objects do disappear. This disappearance can be due to a host of reasons. The sheer profusion of online content and the speed of its creation and circulation is one of them. Another reason, one that has to do with digital infrastructure, is that hyperlinks that enable content retrieval may either ‘break’ or be ‘scrubbed’. Whatever the case, online content is forever in danger of being ‘lost’ to retrieval.

Digital images are transient in a fundamentally disembodied fashion. Older Hindu images could be stolen, destroyed, disfigured, decayed, bought and sold, and even labelled and placed in museums as artifact (Davis 1997, p. 7). However, in all of these desacralizing acts, the feature of a strong, embodied relationship to the object remained central, tying it, in a paradoxical and ironical fashion, to the embodiment inherent within the act of worship itself. However, the virtuality that marks the digital image ensures that all it takes for the image to disappear is a click or a scroll. Hence, the virtuality of online Hindu images that I speak of is not merely characterized by its impermanence; it is also marked by its disembodiment. In their study of online pujas, both Heinz Scheifinger and Nicole Karapanagiotis raise the problem of embodiment vis a vis online worship. Karapanagiotis finds that most ISKCON devotees, for example, imagine the virtual god image to be ontologically akin to an utsava murti—an image especially created for use outside the confines of a temple (Karapanagiotis 2013). Scheifinger notes that digital sensorium abets a simulation of the embodied aspects of an actual puja ritual by allowing the user to light a lamp, offer flowers, or ring a bell at the click of a button (Scheifinger 2010, p. 209). He concludes that while disembodiment is built into digital pujas, the ‘act of seeing’ or darshan maintains the basic postulate of embodiment even in virtual spaces. In her analysis of darshan, Diana Eck too maintained that the act of seeing was fundamentally an embodied act, where ‘seeing’ is a form of ‘touching’ as well as ‘knowing’ (Eck 1998, p. 9).

Shani’s digital presence, however, challenges the well-worn theory of the centrality of the gaze vis a vis Hindu deities. Customarily, devotees are not meant to exchange gaze with a Shani image, and installing a Shani image at home altars is traditionally prohibited. According to legends, Shani’s gaze is able to cause eclipses and blow off the heads of newborn children—as had happened to Surya and Ganesha, respectively. Hence, many (though not all) printed as well as digital images depict his eyes as upturned or askance, rather than looking straight at the viewer. On the digital medium, dramatic special effects are often deployed to underplay the ‘evil eye’ of Shani, such as giving him red, opaque eyes. Shani’s online presence allows us to think of embodiment vis a vis digital images of Hindu gods outside of the predominant framework of darshan and through the analytics of media sensorium.

Here, I find Christopher Pinney’s use of ‘corpothetics’ to be illuminating with regard to the religious sensorium produced in online god posters and memes. Speaking of Hindu god posters in the print era and mythological cinema from later on, Pinney contends that the ‘sensory, corporeal aesthetics’ of these films abolish the space for contemplation and replace it with an aural–visual sensory overload (Pinney 2002, pp. 355–69). This sensory overload is produced with a thick use of special effects whenever divinity is being depicted on screen. Even a cursory glance at digital god posters shows a remarkable density of Hindu popular corpothetics. They consist of photomontages, graphic art and design, and the use of animations on image macros and digitally produced videos, all available for downloading, sharing, commenting, and liking. The images that circulate apply a wide range of technical special effects—such as Photoshop, graphic art and design, animations, background music—to grab the user’s attention in an increasingly phatic social media world. Digital technology allows images of deities to sport animate, glittering halos around the head, rich ornaments on the body, pulsating lotuses, throbbing prasadam, and smoky incense at the feet. Glitters adorn the screen and sometimes fall from the sky, and lamps light up. Quick edits and cuts in videos shared online ensure that the viewer is never looking at the same image for more than a few seconds during the video. The animated image may be accompanied with background music playing a lively bhajan, whose aural sensorium is more reminiscent of Bollywood dance mixes rather than a satsang gathering. Digital images such as these, while undoubtedly transacting in the aural–visual sensory realm, produces a sensorium that extends beyond these limitations. They are replete on vernacular digital platforms, such as ShareChat, from where they permeate deep into circulation through linked platforms, such as WhatsApp. Cursory evidence suggests that the denser the sensorium, the more viral the image/video goes.

This brings us to the key affordance that the digital medium allows for—that of virality. Virality is not just a characteristic of new media and Web 2.0—it is its very life breath. Social media theorists contend that the critical break between older forms of (print and analog) media and new (digital) media lies along the axis of user participation. Passive audiences have given way to active producers of content. In addition, as producers, users do not merely upload original content, they also participate in its circulation using the liking and sharing options, placing hashtags, writing comments, and adding text. Virality, user-generated content, participatory cultures, and ‘the people formally known as the audience’ are some of the ways in which social media theorists have conceptualized the user–producer interface of digital cultures and digital publics (Mandiberg 2012, pp. 1–12; Rosen 2012, pp. 13–16). In analyzing Hindu digital content online, especially with regard to new kinds of mediatization of religion, these aspects of digital sociality are key to examine.

Cultures of virality come with minutiae forms of embodiment, and operate implicitly as performative acts vis a vis Hindu digital imagery. Every ‘like,’ ‘share,’ and ‘comment,’ howsoever phatic, produces multiple channels of devotional communication across platforms, constantly reproducing a digital devotional public in its wake. This movement of images across platforms and devices through performative acts such as ‘liking’ and ‘sharing’ generates the vitality that animates the virtual god image. This combination of embodiment and participation that constitute cultures of virality serves to animate Hindu images that circulate online whereby the divine image attains liveness and vitality. These performative acts transform the virtual image into a vital one—one that is able to move and transfer its energies and blessings from one user–producer to another in a series of ‘likes’ and ‘shares’. Sharing is implicitly built into the digital practice of religiosity and explicitly urged on some image macros that I have come across. Virality of these images, then, serves to reinforce vitality and thereby mitigate their virtuality.

5. Conclusions

This article is an initial exploration of god posters online. In the process, it provides insights into a vast and rapidly transforming world of digitally mediated religious practices in India since the smartphone revolution of 2016. It seeks to explore popular practices of contemporary Hinduism in India from the perspective of mediatization of religion to understand ‘social and cultural processes through which a field or institution to some extent becomes dependent on the logic of the media’ (Hjarvard 2011, p. 120). Digital Hinduism, the article argues, is only the proverbial newest kid on the block of a longer history of the mediatization of religion. The process of mediatization of Hinduism arguably began with the arrival of print technology in the nineteenth century. By examining a long history of Shani imagery—in iconography, sculpture, pen and ink sketches, devotional poetry, print, and online—the article traces how technological aspects of mediatization necessarily produce a rupture from older experiences and practices. It invites readers to reflect upon how various forms of mediatization offer different affordances that influence the manner in which sacred images and devotees interact with each other.

Transformations in the religious realm that this article takes as its point of departure cannot be seen outside of the kind that impact digital technology exerts on secular dimensions of life: from entertainment to news, sports to gaming, consumer behavior to sociality. In this article, I outline four key infrastructural aspects and affordances of digitalization that have fundamentally impacted Hindu religious practices in the contemporary times. One, the proliferation of the smartphone as a commodity and the availability of inexpensive data plans have allowed for the specific kinds of online practices that have developed in India—such as religiously themed greetings and messages that circulate densely over WhatsApp. Two, cross-platform sharing and intermedial dialogue that, I argue, lies at the heart of media transformations of religious practices. A Shani devotee can now, using digital technologies available to her, find ritual experts, follow vows and observances, conduct a puja remotely, listen to the vrat katha, and send a Shani-themed greeting—all at the click of a button. She, as the user–participant in digital religion, need not think about how her acts are simultaneously producing content, consuming it, and distributing it. Third, media convergence remains key in this process of digital transformations. Older media forms and images, such as posters from the print era and special effects from cinema, continue to circulate in new media platforms in a modified fashion. Thus, god posters are often image macros that bring together older posters and photographs using Photoshop, graphic art and design, and a superimposed text. Finally, I argue that virality lies at the heart of digital religiosity in contemporary Hinduism. Virality brings together embodiment and performance in a single, phatic gesture of a ‘like’ or a ‘share.’ In doing so, virality fundamentally contributes to the vitality and lifeness of the sacred object within digital Hinduism.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to the following for their help with writing this article: Neeta Subbaiah, my research assistant; Sharada Natarajan, Bindu Menon, and Sharmadip Basu for their critical comments at various stages of its preparation. Research for this article was made possible by an internal grant awarded by Azim Premji University.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

References

- Apte, Vaman S. 1957–1959. Revised and Enlarged Edition of Prin. V. S. Apte’s the practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Poona: Prasad Prakashan.

- Banaji, Shakuntala. 2018. Vigilante Publics: Orientalism, Modernity, and Hindutva Fascism in India. Javnost—The Public: Journal of the European Institute of Communication and Culture 25: 333–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, Danah. 2012. Participating in the Always-On Lifestyle. In The Social Media Reader. Edited by Michael Mandiberg. New York: NYU Press, pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2017. Surveying Theoretical Approaches within Digital Religion Studies. New Media and Society 19: 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2004. The Network Society. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Courtright, Paul B. 1985. On This Holy Day in My Humble Way: Aspects of Puja. In Gods of Flesh, Gods of Stone. Edited by Joanne P. Waghorne and Norman Cutler. Pennsylvania: Anima Publications, pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Richard H. 1997. Lives of Indian Images. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, Patrick. 2012. The Language of Internet Memes. In The Social Media Reader. Edited by Michael Mandiberg. New York: NYU Press, pp. 120–36. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, Diana. 1998. Darsan: Seeing the Divine Image in India. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Froystad, Kathinka. 2019. Affective Digital Images: Shiva in the Kaaba and the Smartphone Revolution. In Outrage: The Rise of Religious Offence in Contemporary South Asia. Edited by Paul Rollier, Kathinka Froystad and Arild Engelsen Ruud. London: UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gittinger, Juli. 2015. Modi-Era Nationalism and Rise of Cyber Activism. Exemplar 3: 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Phyllis K. 2010. Seeing the Divine through Windows: Online Puja and Virtual Religious Experience. Online: Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 4: 151–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2011. The Mediatisation of Religion: Theorising Religion, Media, and Social Change. Culture and Religion 12: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, Stewart M. 2012. Concluding Thoughts: Imagining the Religious in and through the Digital. In Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. Edited by Heidi A. Campbell. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Kajri. 2007. Gods in the Bazaar: The Economies of Indian Calendar Art. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, Robin, and Assa Doron. 2013. Cell Phone Nation: How Mobile Phones have Revolutionized Business, Politics, and Ordinary Lives in Indi. Gurgaon: Hachette India. [Google Scholar]

- Karapanagiotis, Nicole. 2010. Vaishnava Cyber-Puja: Problems of Purity and Novel Ritual Solutions. Online: Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 4: 179–95. [Google Scholar]

- Karapanagiotis, Nicole. 2013. Cyber Forms, ‘Worshippable Forms’: Hindu Devotional Viewpoints on the Ontology of Cyber-Gods and -Goddesses. International Journal of Hindu Studies 17: 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochtefeld, James G. 2001. “Saturday” and “Saturn”. In The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Edited by James G. Lochtefeld. New York: Rosen Publishing, pp. 608–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lovink, Geert. 2011. Networks without a Cause: A Critique of Social Media. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf, Philip. 1995. All in the (Raghu) Family: A Video Epic in Cultural Context. In Media and the Transformation of Religion in South Asia. Edited by Lawrence A. Babb and Susan S. Wadley. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 217–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf, Philip. 2007. Hanuman’s Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mandiberg, Michael. 2012. The Social Media Reader. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, Sriram. 2015. Locating the ‘Internet Hindu’: Political Speech and Performance in Indian Cyberspace. Television and New Media 2015: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinney, Christopher. 2002. The Indian Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: Or, what happens when Peasants ‘Get Hold’ of Images. In Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain. Edited by Faye Ginsburg, Lila Abu-Lughod and Brian Larkin. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 355–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pinney, Christopher. 2004. Photos of the Gods: The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India. London: Reaktion Press. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, James J. 1985. Creation of the Sacred Image: Apotheosis and Destruction in Hinduism. In Gods of Flesh, Gods of Stone. Edited by Joanne P. Waghorne and Norman Cutler. Pennsylvania: Anima Publications, pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, Judy. 1986. Celestial Destiny: Popular Art and Personal Crisis. India International Centre Quarterly 13: 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Radovanovic, Danica, and Massimo Ragnedda. 2012. Small Talk in the Digital Age: Making sense of Phatic Posts. MSM2012 Workshop Proceedings, CEUR 838: 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal, Arvind. 2001. Politics after Television: Religious Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Indian Public. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Gopinath TA. 1971. Elements of Hindu Iconography. Delhi: Indian Book House. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Jay. 2012. The People Formally Known as the Audience. In The Social Media Reader. Edited by Michael Mandiberg. New York: NYU Press, pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Scheifinger, Heinz. 2010. Hindu Embodiment and the Internet. Online: Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 4: 196–219. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, Shilpa. 2020a. Shani Pradosh Vrat Katha. Jagaran. Available online: https://www.jagran.com/spiritual/puja-path-shani-pradosh-vrat-katha-importance-and-significance-read-this-story-20579360.html (accessed on 3 August 2020).

- Shrivastava, Divyangana. 2020b. Shani Vrat Katha. Navbharat Times. Available online: https://navbharattimes.indiatimes.com/astro/dharam-karam/moral-stories/know-shanivarvrat-story-or-katha-72886/ (accessed on 3 August 2020).

- Smith, H. Daniel. 1995. Impact of ‘God Posters’ on Hindus and their Devotional Traditions. In Media and the Transformation of Religion in South Asia. Edited by Lawrence A. Babb and Susan S. Wadley. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 24–50. [Google Scholar]

- Stolow, Jeremy. 2013. Deus in Machina: Religion, Technology and the Things in between. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tanvi. 2020. Shanidev ke prakopon se mukti paane ke liye har shanivar karen vrat aur padhen yeh katha. Patrika. Available online: https://www.patrika.com/religion-news/shanivaar-vrat-katha-and-shani-puja-mahatva-in-hindi-5696809/ (accessed on 3 August 2020).

- Udupa, Sahana. 2018. Enterprise Hindutva and Social Media in Urban India. Contemporary South Asia 26: 453–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadley, Susan S. 2005. Vrats: Transformers of Destiny. In Essays on North Indian Folk Traditions. New Delhi: Chronicle Books, pp. 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Waghorne, Joanne P. 1985. Introduction. In Gods of Flesh, Gods of Stone: The Embodiment of Divinity in India. Edited by Joanne P. Waghorne and Norman Cutler. Pennsylvania: Anima Publications, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler, Xenia, ed. 2020. Digital Hinduism. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Shani Shingnapur Temple lifts ban on women’s entry. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/shani-shingnapur-temple-lifts-ban-on-womens-entry/article8451406.ece. The Hindu, 8 April 2016. (accessed on 12 August 2020). And Alok Prasanna Kumar. Women and Shani Shingnapur Temple: A Brief History of Entry Laws and how Times are Changing. Firstpost, 12 April 2016. Available online: https://www.firstpost.com/india/women-in-shani-shingnapur-brief-history-of-temple-entry-laws-and-how-times-are-changing-2723582.html (accessed 12 August 2020). |

| 2 | https://www.shanidev.com/about-us.html (accessed on 3 August 2020). |

| 3 | I am grateful to Sarada Natarajan for the key insights, citations, and references around classical iconography of Shani discussed in this and subsequent paragraphs. Private conversation with Sharada Natarajan, 3 August 2020. |

| 4 | Personal communication from Sarada Natarajan dated 3 August 2020. |

| 5 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sNBJiXNxuZ0&t=12s (accessed on 12 August 2020). |

| 6 | Shilpa Shrivastava (2020a), “Shani Pradosh Vrat Katha. https://www.jagran.com/spiritual/puja-path-shani-pradosh-vrat-katha-importance-and-significance-read-this-story-20579360.html (accessed on 3 August 2020). Tanvi (2020). Shanidev ke prakopon se mukti paane ke liye har shanivar karen vrat aur padhen yeh katha. Available online: https://www.patrika.com/religion-news/shanivaar-vrat-katha-and-shani-puja-mahatva-in-hindi-5696809/ (accessed on 3 August 2020). Divyangana Shrivastava (2020b). Shani Vrat Katha. Available online: https://navbharattimes.indiatimes.com/astro/dharam-karam/moral-stories/know-shanivarvrat-story-or-katha-72886/ (accessed on 3 August 2020). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).