Abstract

Al-Janna—Paradise—is the most important image of the afterworld in Islam. The Qur’an describes paradise as an oasis. Along with the spread of Islam, the image of paradise has gradually transformed into a garden with blooming flowers, where different Muslim groups chose their favorite flower based on their local knowledge and custom. Thus, the Persian, Turkish, and Hui peoples of China chose the rose, tulip, and peony as their respective flowers symbolizing paradise. We argue from these cases that as a world religion, Islam is locally practiced and understood, with many different variations.

1. Introduction

There is a stereotype in Islamic studies that Muslim scholars like to emphasize the unity and eternal character of Islam, while many western scholars influenced by “orientalism” regard Islam as a “primitive culture”. Here, the question is: How can we understand Islam as a unique culture system with many different variations? In recent years, the so-called Islamic Anthropology has tried to transcend these kinds of limitations, and considers Muslims living in particular places to have adapted Islamic tradition to their “local knowledge”, in order to practice Islam in their own context. Richard Tapper wrote a profound review of “Islamic Anthropology” in 1995, saying: “The best anthropological studies of Islam, by Muslims as well as non-Muslims, have resisted the tyranny of those (whether Orientalist outsiders, or center-based ulama) who propose a scripturalist (Great Tradition) approach to the culture and religion of the periphery they aim to understand how life (Islam) is lived and perceived by ordinary Muslims, and to appreciate local customs and cultures (systems of symbols and their meanings) as worthy of study and recognition in their social contexts, rather than as ‘pre-Islamic survivals’ or as error and deviation from a scriptural (Great Tradition) norm” Tapper (1995). Trying to interpret Islam through “how life is lived and perceived by ordinary Muslims”, is the very point we took when doing our fieldwork in Northwest China.

To carry out an anthropological study, we chose the perspective of the symbolic anthropology, which focuses on cultural symbols and their uses in a particular society. As Mary Douglas (1921–2007) wrote in her famous book published in 1960s, each culture “is a universe to itself” Douglas (1978). All anthropologists believe that one should start interpreting cultures by placing them in the full context of any given universe. Almost at the same time, Clifford Geertz (1926–2006) suggested we see culture as a web of symbols that can help people to understand what their behavior means, through a thick description of the context it occurs within Geertz (1973). In his further studies, Clifford Geertz put forward the concept of “local knowledge”, which focuses on “understanding understandings”; that is, to understand their own understandings of the local peoples Geertz (2008). Such an anthropological approach helps us to interpret the diverse practices and understandings of Islam throughout Persia, Turkey, and China.

1.1. The Image of Paradise in Islam

This paper considers the case of the image of paradise, which originated from the Qur’an, in order to discuss the diverse interpretations of the image in different Muslim societies. In the following, this paper provides a comparative perspective and cross-cultural analysis of the rose, tulip, and peony in three Muslim societies of Persia, Turkey, and China, being different symbols of the imaginary flowers of Paradise.

As is well-known, the Arabic word for paradise is ‘al-Janna’ (with plural form ‘al-Jannt’), which is mentioned 139 times in the Qur’an. Muslim scholars have interpreted eight different names referring to Paradise Latiff and Ismail (2016). All these names indicate that Paradise has different attributes and levels which in all names, comprise one Divine Garden. According to the Qur’an, the eight names of Paradise are as follows:

- (1)

- Jannt al-‘Adn [Qur’an, 9:72], which is equal to the Garden of Eden.

- (2)

- Jannt al-Na‘m derives from Na‘m, with the meaning of delight [Qur’an, 82:13, 83:22].

- (3)

- Jannt al-Firdaws, which is equal to paradise [Qur’an, 23:11]; or Fa-hum Frawdat [Qur’an, 30:15] or Frawdat al-Jannt [Qur’an, 42:22].

- (4)

- Jannat al-Khuld, the Garden of Immortality [Qur’an, 25:15].

- (5)

- Jannt wa ‘uyn, gardens with watersprings [Qur’an, 77:41, 51:15].

- (6)

- Al-Ghurfat, the high place [Qur’an, 25:75].

- (7)

- Jannat al-Ma’w, the Garden of Abode [Qur’an, 53:15].

- (8)

- Dr al-Salm, the Abode of Peace [Qur’an, 6:127], Dr al-Muqmat, the Mansion of Eternity [Qur’an, 35:35], and Dr al-Qarr, the Enduring Home [Qur’an, 40:39], all deriving from Dr (abode) (Nazia 2011; Sebastian and Lawson 2016).

In the Qur’an, the description of Paradise is accomplished through a language of imaginativeness and sensitization. The reason for this is, however metaphysical an idea is, it still needs to be understandable and imaginable through specific symbols. Toshihiko Izutsu (1914–1993) agreed that Arabic culture is a visual and auditory culture. When this culture describes a concept, it is often accompanied by a rich description of the environment. Thus, the Qur’an is full of visual images and stores unexpected fantastic sounds that suddenly appear when reading Toshihiko (1992). The Paradise imagery depicted in the Qur’an seems to have visual appearance, as well as the sensual eternal life there. According to verses from the Qur’an, shades and flow streams are key features of Paradise, which reflects the Bedouin Arabs’ desire for oases. Some exemplary quotes are as follows Pickthall (1996):

[13:35] A similitude of the Garden which is promised unto those who keep their duty (to Allah): Underneath it rivers flow; its food is everlasting, and its shade; this is the reward of those who keep their duty, while the reward of disbelievers is the Fire.

[47:15] A similitude of the Garden which those who keep their duty (to Allah) are promised: Therein are rivers of water unpolluted, and rivers of milk whereof the flavor changeth not, and rivers of wine delicious to the drinkers, and rivers of clear run honey; therein for them is every kind of fruit, with pardon from their Lord.

[43:71] Therein are brought round for them trays of gold and goblets, and therein is all that souls desire and eyes find sweet. And ye are immortal therein.

Such images from the Islamic scripture heavily influenced the culture of gardens in this mortal life. According to Zainab Abdul Latiff and Sumarni Ismail, Islamic garden culture belongs to three different roots: the Arab, the Persian, and the Turkish root. Latiff and Ismail (2016) Among these three cultures, the images of paradise were undoubtedly influenced by their own unique geographic landscapes.

Throughout history, every Muslim dynasty has built their palaces under their particular understanding of Paradise in the Qur’an. From the Umayyad (661–750 AD) to the Abbasids caliphate (750–1258 AD), the Arab caliphs built Mosques and palaces in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Maghrib, and Spain. Unfortunately, only a few ruins can be found now.

Built in the 14th century during the time of the Nasrid dynasty (1230–1492 AD), the Alhambra of Granada, Spain, is one of the most intact Arab royal palaces which has survived to present, which should be seen as a model of Arabic aesthetics. As a World Heritage site, as declared by UNESCO, the Alhambra of Granada seems to be a portrait of the heavenly realm as found in the Qur’an, which consists of a garden with tree shades, flowing water streams, and beautiful mansions. The snow water coming from the mountains flows through every yard of the palace, acting as the spirit and soul of this imaginary paradise. According to Dr Jesús Bermúdez López (1959–) of Granada, in the typical Nasrid architecture, “the building always arranged around an inner courtyard with a water source at its center”; the patio includes “water, gardens, lights, and heavenly vaults, and can be seen as a return to the nomad tent” Hattstein and Delius (2004).

Along with the spread of Islam, diverse geographical landscapes and ethnicities entered and came under the rule of the Caliphate. Thus, the mortal copy of Paradise was turned into different types. For example, in modern Iran, the ecological conditions are suitable for roses due to the abundant sunshine and large temperature difference between day and night. It is believed that the most famous Islamic garden originated from the “paradise” garden of ancient Persia. Actually, the English word ‘paradise’ derives from Greek word ‘paradeisos’, which originated from the ancient Persian word ‘paridaiza’, meaning garden enclosed by walls Khansari et al. (2004). Thus, the mortal copy of Paradise was transformed from an Arabic oasis into a Persian garden. The most typical Persian garden would be “Chahar-bagh”, or the Four-part Garden. According to the description of Paradise in the Qur’an, Chahar-bagh is divided into four geometric divisions by four water channels, symbolizing the heavenly rivers of water, milk, wine, and honey Farahani et al. (2016). For example, the Chahrbagh-e Abbas in Isfahan is one of the most famous Persian gardens, built in 1596 by Shah Abbas the Great (1571–1629) of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736). The Persian garden has had a wide influence throughout the Islamic world, from India to Spain. The Taj Mahal of Agra, as a monumental imperial mausoleum with an attached garden with four water channels, was heavily influenced by the Chahar-bagh structure. It is not only evident in the garden design, but also in Persian Sufi poetry, in which gardens with roses and nightingales were set as a kind of paradigm of Paradise and the Divine Love. This tradition of literature also had a strong influence among Muslims from China to Turkey.

1.2. The Awkward Position of Chinese Muslim and Its Future

Although China has a Muslim population of over 23 million (Table 1), they are still absent from the master opus on global Islamic history. For example, with respect to the study of Islamic architecture and Islamic philosophy, such as in the books of Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius (2004), Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Oliver Leaman (1996), (Hattstein and Delius 2004; Nasr and Leaman 1996) it is difficult to find a chapter dedicated to China. This is partly because Muslim is only an ethnic minority group in China, who are traditionally not a part of the Islamic world. Otherwise, Muslim is also absence from the master opus of history of China, especially in the history of thoughts and philosophy, due to the same reason as for ethnic minority groups. This awkward position of Chinese Muslims can only be changed through more academic studies revealing the hidden treasures of Chinese Muslim culture. As the inheritor of two great civilizations of the world, Chinese Muslims have the natural advantage of integrating Islam and Chinese heritage to produce something new.

Table 1.

Muslim Population of China, 2010 census.

The studies of Chinese Muslims in the West began during the late 18th century. The first important book was written by an English missionary (of the China Inland Mission) named Marshall Broomhall (1866–1937) Broomhall (1987). Since then, three kinds of research disciplines have grown. Profound historical studies have been made by Joseph Fletcher of Harvard and his disciple Jonathan Lipman (Fletcher and Manz 1995; Lipman 1997), Donald D. Leslie of Australia Leslie (1981), Raphael Israeli of Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Israeli 1979; 1994), Michael Dilon Dilon (1999), David G. Atwill Atwill (2005), and Zvi Ben-Dor Benite Benite (2005). With respect to anthropological studies, we mention Dru C. Gladney Gladney (1996), lisabeth Alles Alles (2000), Maris Gillette Gillette (2000), Maria Jaschok and Shui Jingjun Jaschok and Shui (2000), and Matthew S. Erie Erie (2016). As for philosophical studies, we mention the outstanding works of the couple Sachiko Murata and William C. Chittick, both in English and Chinese (Murata et al. 2009; Murata 2000).

This paper especially benefits from the study of Jonathan Lipman, Dru C. Gladney, Sachiko Murata, and William C. Chittick. According to Jonathan Lipman, “Familiar Strangers” (to China and to Muslim world both) provides the best understanding of the awkward position of Chinese Muslims. Dru C. Gladney argued that the ethnic identity of the Hui is a result of “making” and “negotiating” between the Muslim community and the state and has been differently expressed among different contexts. Otherwise, we may critique that the weakness of his fieldwork made Dru C. Gladney’s works show a few mistakes and shortcomings Ma and Zhou (2001). Sachiko Murata and William C. Chittick did a great job of explaining how Chinese Muslim scholars transmitted Islamic thoughts into Confucian terms and created amazing intellectual fruit. As Seyyed Hossein Nasr said, “this whole continent of philosophical, mystical, and religious thought where the Islamic and Chinese traditions have met and created works whose significance is now being ever more realized beyond the confines of Chinese world” Nasr (2009).

In China, modern academic research on the Hui or Chinese Muslim began in the 20th century. The most important historical studies were made by Bai Shouyi (1909–2000), one of the most outstanding historians of 20th century China with a Muslim background, initiated the new era of Muslim studies in China. After the 1990s, numerous articles and books have been published based on anthropological fieldwork and research, along with more and more frequent international collaborations. Thus, we may expect that in a few decades, the significance of Chinese Muslim culture and thoughts may have been explored intensively and gained its proper position, both in the history of world Islam and China.

1.3. Resources and FieldWork

This paper attempts to discuss the experience and practice of the Hui people or Chinese Muslim through cultural symbolism, based on their unique understanding of Islam, by taking the methods of anthropological fieldwork, as well as comparative literature research.

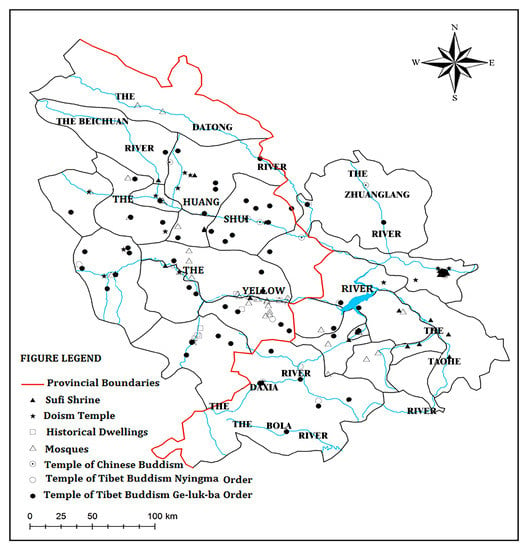

Throughout the history of China, Muslim was called “Huihui” from the 10th century. Zhou and Ma (2009) After 1949, the Communist Party and the new government identified “Hui” as one of the ten Muslim ethnic groups of China (Table 1). Their unique ethnic character has been summarized as that they are the same as common Chinese, except for their Muslim background; meanwhile, the other nine ethnic groups are believed to have certain characteristics, such as unique languages. According to Zhou Chuanbin and Ma Xuefeng, as for Chinese Muslims themselves, their Chinese name “Huihui”, which has the meaning “return”, shows their longing for the holy Mecca and their ultimate return to Paradise Zhou and Ma (2009). As for Dru C. Gladney, the Hui live isolated existences on the far periphery of the Muslim world and, so, have to constructed an Islamic culture system with local characteristics Gladney (1996). Our fieldwork focused on the He-Huang area of northwest China. While “He” refers to the Yellow River and “Huang” the branch of it named Huangshui, the He-Huang area, across the Gansu and Qinghai provinces, forms a multi-ethnic area of northwest China, consisting mainly of the majority Chinese, Muslims, and Tibetan Buddhists (Figure 1). For years, we have done field work among different ethnic groups here, which has allowed us to identify the interesting cultural phenomenon that people of different ethnic backgrounds do share some common feelings, knowledge, and practices, such as the use of the peony as a symbol or metaphor. In this paper, we draw our attention only to the case of the Hui people of this region.

Figure 1.

Rivers and Religious Sites of the He-Huang Area (Map by Guo Lanxi, 2018).

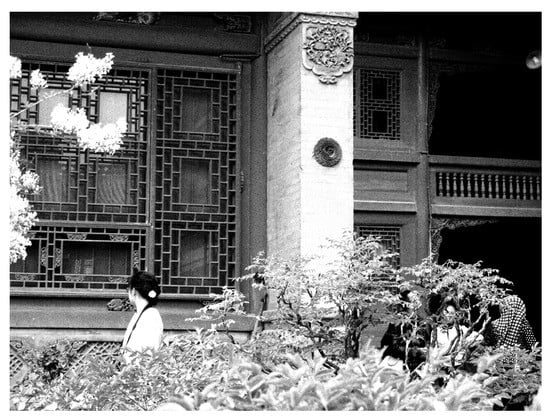

In the He-Huang area, most private courtyards, mosques, and Sufi shrines of the Hui follow the Chinese traditional quadrangle courtyard layout and favor the use of traditional Chinese brick and wood architectures. As Figure 2 shows, a traditional courtyard in Hezhou city built in 1940s, which belonged to a former Muslim warlord, appears to have a typical Chinese architecture with a peony garden in the center. We may find that the landscape arrangement of the Hui shows distinctive localized characteristics, in which flower beds are basically in the center of the yards, planted with various local flowers and supplemented by Chinese-style bonsais, fish tanks, brick carvings, and so on. This devotion and love of gardens and water are derived from Islam as well as Chinese tradition. The climatic conditions of He-Huang area allows for peonies to grow for decades and more than a meter high. There are many traditional famous kinds of peonies in the middle of the garden, such as Fotouqing, Pink Lion, and Purple lotus. The Fu Lu Shou (福禄寿), brick carving of the Suoma Qubbah of Gansu province, are composed of peony, longevity peach, and deer, while the Longevity Crane (松鹤延年) is composed of pine tree, peony, and crane. There are brick carvings in the Taitai Qubbah of Gansu province composed of peony, birds, and phoenix, called the Birds Paying Homeage to the Phoenix (百鸟朝凤). In particular, the use and interpretation of the peony as a symbol is an interesting case illustrating Islamic paradise imagery in China, which demonstrates that the Hui people of China have succeeded in combining Islam with their local geography and cultural background.

Figure 2.

A Traditional Chinese Muslim Courtyard of Hezhou City (Zhou Chuanbin, 2014).

Regarding the use of flower metaphors among different Muslim societies, we rely on the Sufi literature of Persia, Turkey, and China. We may mention Ahmad al-Ghazl (d. 1126), Fard al-Dn Attr (d. 1220), Nezami Ganjavi (d. 1209), Jall al-Dn Rm (d. 1273), Nusrati (d. 1673), Sa’di (d. 1291), and Hfiz (d. 1390) of Shiraz. There are two major pieces of Chinese Sufi literature which need to be mentioned: The first is the Qingzhen Genyuan (The Root of Pure and True), an interior mystical history of a Qadariyyah Sufi order of Hezhou city; and the second is the Tianfang Erhya (A Lexicographical Book of Arabic and Persian), written by a Hui Scholar Lanxu (1813–1876) in the 19th century. Furthermore, we have visited Shiraz, Isfahan, Istanbul, Agra, and Lahore in recent years.

2. Flowers as a Symbol of Divine Love

Persian and Turkish cultures have been deeply influenced by Sufi poetry, both of their literature regarding the garden as a spatial construction for divine love. The reason for this lies in the fact that the use of love poetry to describe the inner journey of Sufis developed in medieval Persia. Rmī is a Persian migrant who settled in Konya of Anatolia and who was perhaps the most important influence on Sufi literature in Turkey. Even in China, from the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) onward, Persian was used as the major international language, not to speak of Mughal India (1526–1857) (Liu 2008; Wild 1945). From the historical influences upon Turkey, India, China, and Central Asia, we can see how the metaphor of divine flowers spread along with the Persian Sufi literature tradition.

Love has been an integral component of Sufism from Rbia al-Adawiyya (d. 801–802) to present. Previous Sufis have expressed presenting the path of spiritual wayfaring as degrees of love, such as Shaykh Ahmad al-Ghazlī (d. 1126) and Abl-Hasan al-Daylamī (d. late 10th century), while Ab Tlib al-Makkī (d. 966) saw love as the highest of all stations and pure love as the completion of tawhīd. The most important Sufi master who developed the tradition of love in Sufism would be Ibn ‘Arabi (d. 1240). He recognized that God’s love plays an essential role both in the origin and structure of this world, which will finally lead to an ultimate union. ‘Ishq (passionate love) came to be a central theme for most Persian Sufi figures, such as Farīd al-Din Attr (d. 1220) and Jall al-Dīn Rmī (d. 1273) Lumbard (2007).

The later writings of the Persian Sufi tradition interpreted the subtle metaphysics of love. According to the poems of Jall al-Dīn Rmī (d. 1273), Allah is the source of love, and love is the spiritual path of being reunited with Allah. In his opinion, all love is, in fact, love for God, as whatever exists is His reflection or shadow Chittick (1983). He compared his Masnavi to “the paradise of hearts” (Rumi 2004a, p. 3). As the carrier of mystic experience, Sufi literature has always used the symbolism of gardens and flowers to express their love for God. In Persian Sufi poetry, Paradise is described as a garden and the rose is the secular manifestation of the Divine Beauty. Love, as a path, leads the lover to seek for the Paradise where the Beloved has been hidden in.

When seeds are hidden in the earth,

Their inward secret becomes the verdure of the garden.Rumi (2004b)

In Nusrati (d. 1673)’s narrative, the eight gardens indicate different levels, with the garden of Love as the summit (Hafiz 2006, p. 160). Moreover, they read the arrangement of gardens as a metaphor for paradise, such that the imaginary garden for lovers was decorated with ponds and flowers (Uludas and Adiloglu 2011, p. 89). The garden exists for the Beloved (the ultimate one is the Beloved). Flowers are the expression of love. Therefore, the garden needs to be decorated with countless flowers.

The Haft Paykar, also known as The Seven Beauties, is a romantic epic by Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi (1141–1209). As Nezami narrates, Bahram V married seven princesses of seven districts for whom he built, in his garden, seven domes in different colors. Flowers, seven domes, and seven beauties, as symbols, express the seven virtues one must cultivate in the romantic epic. The seven tales of the interlude symbolize the seven steps of a spiritual journey Kive (2012).

A myriad flowers blossomed there,

its water sleeping, grass aware.

Each flower was of a different shade;

The scent of which for miles did spread…

Streams flowed like rose-water.Ganjavi (2015)

Although flowers being the symbol of love seems to be a universal practice for all humanity, Islam is especially adept at expressing its religious concepts with non-concrete symbols. Flower patterns of paradise imagery are exemplary of Islamic spatial descriptions (Uludas and Adiloglu 2011, p. 89). Flowers are an indispensable symbol in Islamic art, architecture, and horticulture and, as a result, flowers gradually became the metaphor of the imagery of Paradise. In addition, the blooming and dying of a flower appears as the process of a human being in this life, and is also a metaphor for the resurrection in hereafter.

However, the different terrains, water sources, climates, and other environmental factors all over the world have resulted in diverse flowers growing everywhere, where each place grows a unique representative of the flowers. Different ethnic groups in the Islamic world have made diverse choices on their local ecological environment, which manifested Islam’s unity in diversity. Which flower would be crowned and chosen to express the divine love? Persians fell in love with roses, while Turkish regard tulips as the prize of any garden. The Chinese Muslim—the Hui people—have chosen the peony as their favorite flower.

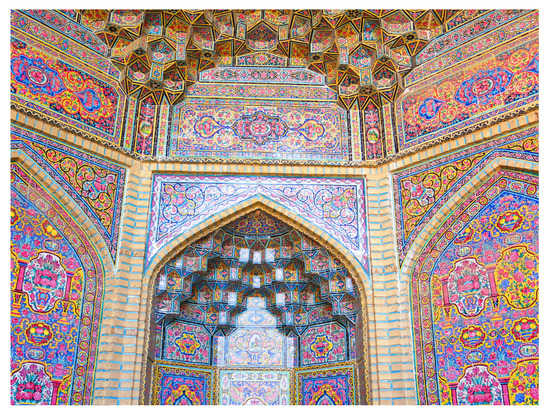

2.1. The Rose in Persian Culture

There is one flower which would eclipse all other flowers, admired for its aesthetic beauty in Persian culture: the rose, which is seen as the distillation of “the sweat of the Prophet’s grace” Meisami (1985) (Figure 3). Rzbihn Baqī (1128–1209) was an early Persian mystic who had a subtle interpretation of the mystical states and love theories. He highlighted the prophetic tradition that Muhammad declared the red rose to be “the manifestation of God’s glory” (Schimmel 1975, p. 299)—in particular, the marvelous red rose—as the divine presence that reveals divine beauty. Persian poets have called the Prophet “the nightingale of the Eternal Garden” (Schimmel 1975, p. 222), in order to explain his love for roses. In Persian literature, the finest of gardens is the rose garden, a synonym for Paradise Baldock (2005).

Figure 3.

Nasīr al-Mulk Mosque of Shiraz, Iran (Photo by Zhou Chuanbin, 2017). The Mosque was built in the 19th century under the rule of the Qajar dynasty (1789–1925), which is famous for its rose ceramic tiles and colored glass, which makes people feel like they are in a colorful garden.

In Ferdowsi’s (940–1020) poems, the author of Shahnameh, which is also known as the “Book of Kings” and is considered the most influential epic poem of the Persian literature, The Prophet Muhammad is always surrounded by roses in the garden of Paradise:

Where rose all their beauties spread;…

Amidst thy garden’s sweetest bowers,

Place him with summer’s fairest flowers;

Let hyacinths and roses glow,

And round his haunts their garlands throw.Costello (1845)

The theme of Persian Sufi poetry is seeking for the divine beauty of the Beloved. Gulistan (The Rose Garden) is the best-known work of Sa‘di of Shiraz (1210–1291). In Persian, gol means rose, which is also the general name for all flowers in Persian and Turkish Abdo (2015). According to Gulistan, one day Sa’di was accompanied with a friend walking in a garden. Both were attracted by the beautiful scenery, as if the garden were earthly paradise, where birds filled the garden with songs and the flowers were colorful and sweet-smelling. When his friend gathered up the fallen flowers to take away, Sa’di said he could write an eternal rose garden beyond the physical world with his pen. Additionally, the Gulistan of Sa‘di is one of the textual books in traditional Chinese Mosques which is looked to as a guide to seek the heavenly garden.

What use to thee that flower-vase of thine?

Thou would’st have rose-leaves; take then, rather, mine.

Those roses but five days or six will bloom;

This garden ne’er will yield to winter’s gloom.Sadi Shira (2002)

It is similar for Hfiz (1315–1390), who saw Paradise as a place with roses blooming and nightingales surrounding.

Now that the rose holds a cup of clear wine in hand,

nightingale sings the rose’s praise in a thousand tongues.(Hafiz 2006, p. 208)

The nightingale and the rose in Persian literature are metaphors for the lover and the Beloved. Love made the nightingale willingly become a servant of the rose, such that all kinds of pains would not let him give up his love, even if the jealous wind shook stems of the rose, which would make the nightingale twinge, and the soft breeze was, indeed, touched by songs of the passionate bird. Hfiz poetically interpreted love as not only the glue that holds the Divine Unity together, revealing that the path can be a painful process, but also as the mysterious knowledge condensed into the Everlasting Rose. The beauty of the rose is what the nightingale can only feel in love, as well as the mystical state of “Fan”, the Sufi term for “annihilation” (Schimmel 1975, p. 55) which describes the passing away of awareness of the separate self in contemplation of the Godhead Wilcox (2011). In other poems, the nightingale reunited with the rose in the garden after undergoing separation, ending with the death of the nightingale. It symbolizes the mystical state of “Baq”, or “permanent life in God” (Schimmel 1975, p. 55), which is the overwhelming in-flowing and subsistence of the attributes of God Wilcox (2011). Beyond that, both Fan and Baq are the highest stations on the spiritual path, in which Fan logically precedes Baq.

Not only in literature, but in real life, rose is also the eternal protagonist in the Persian garden. The famous Damask rose originated from the foothills of central Asia; its use can be dated back to at least 1500 years ago. The palace built in Tehran by the Qajar dynasty (1789–1925) was named “Golestan Palace” (the Palace of Roses). In Persian and Mughal gardens, roses, water, greenery, and chambers, as constituent elements, are seen as reflecting the principle of Paradise. However, the roses of the garden in this world do not remain blooming. Their blooming and fading foreshadows, as a mirror of this world.

2.2. The Tulip in Turkish Culture

In the 11th century, when the Seljuks came west and seized Anatolia from the Byzantines, tulips appeared in their art for the first time and became the most important ornamental plant. In Masnavi, tulips are always present when Rmī portrays a garden in spring:

I’d love to stay in vernal realms instead,

Inside this mystic plain and tulip bed.(Rumi 2004a, p. 129)

In summer, all admire the countryside

With farms and tulip fields on every side.Rumi (2013)

Rose, as a symbol, penetrated into Turkic culture through Persian Sufi literature, in which the tulip is another kind of flower often juxtaposed with it. Roses and tulips manifest the earthly reflection of the Divine beauty in Rmī’s poems. The possible reason for this is that both rose and tulip look like a heart or lantern shape when their flowers are in bud. The Beloved bestowed on Rmī a boundless garden of the heart, where tulips were enlivened with a fire of Love. When one man’s soul is grateful for God’s mercy, his heart would be filled with beautiful tulips and roses that glisten mysterious lights as the divine wisdom, which is pursued by the Sufi practice.

The glow of the rose and the tulip means a lamp inside.Rumi (1997)

After the Turks had arrived in Anatolia, an enthusiasm for tulips was raised throughout the Ottoman Empire. In Süleyman I’s time (1494–1566), gardeners became devoted to cultivating tulips and to breed new varieties, making tulips the quintessential Turkish flower. For example, Seyhulislam Ebusuud Efendi (1570–1625), the minister of Islamic issues of the Ottoman Empire, was said to possess a unique tulip known as Nur-i-Adin, “The Light of Paradise” (Dash 2000, p. 20). Actually, Tulips have always been popular in the Central Asia, which is believed to be the homeland of all Turks. In Bbur-nma, the autobiography of the founder of Mughal Empire of India, Babur (1483–1530) described how he used to go to Brn, Chsh-tpa, and Gul-i-bahr of Afghanistan in 1506–1507, where he saw more beautiful tulips than in any other part of the land:

Many sorts of tulip was bloom there; when I had them counted once, it came out at 34 different kinds as [has been said]. This couplet has been written in praise of these places:

Kbul in Spring in an Eden of verdure and blossom;

Matchless in Kbul the Spring of Gul-i-bahr and Brn.Beveridge (2020)

In the middle of the 16th century, tulips were imported from Turkey to Europe. From 1633 to 1637, a tulip mania arose in the Netherlands, where the price of tulips was higher than that of gold. Thus, we can say that the tulip is a gift given to the whole world by the Ottoman Turks. Later, a three-decade long tulip mania erupted again in Istanbul during the reign of sultan Ahmad III (1673–1736) in the early 18th century. At present, the tulip is the national flower of Turkey, Netherlands, and Kazakhstan. So, why do the Turks like tulips so much?

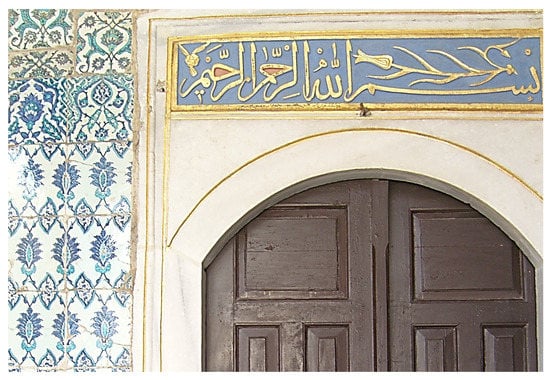

First, the tulip is an important symbol for the Turks, to remember their eastern homeland. The first tulip sprang from the scrubby slopes of the Pamirs and flourished among the foothills and valleys of the Tien Shan Mountains (Dash 2000, p. 4). The diffuse spread of tulips coincided with the Turk’s westward migration in the history. In an Ottoman garden, only narcissus, rose, hyacinth, and carnation were worthy to be planted alongside tulips, which were considered to be the first level of flowers, while all others were considered to be just wildflowers. It is said that Sheikh Hasan, the grandson of the Prophet, explained the Hadith, which said gardeners will definitely go to heaven to continue their work, as all flowers belong to heaven (Dash 2000, p. 10). This initiated the custom that gardeners cultivated tulips to bless themselves to ascend into Heaven, and women of the Ottoman Empire sewed tulips as “religious tokens” and “offered them up with prayers for a husband’s safe return from war” (Dash 2000, p. 19). Secondly, the tulip is the best metaphor of the love for God (Figure 4). Due to linguistic reason, “lâle” and “hilâl”, the Turkish words for “Tulip” and “crescent moon”, are both formed from the same letters as the word Allh (one alif, two lm, and one h), the divine name (Schimmel 1975, p. 422). As a result, the numerical value of “lâle” is 66, which is seen as one of the secrets of tulips. Furthermore, “lâle” is the same as “Leila” in Arabic, the heroine of one of the most famous love stories in the whole Islamic world. In the love story of Leila and Majnun, Leila is a metaphor of the Beloved God, while Majnun represents a Sufi who seeks the Beloved with multifarious sufferings. Importantly, tulips usually open a sole flower, which symbolizes the love of the Unique God.

Figure 4.

The Topkapı Palace of Istanbul (Zhou Chuanbin, 2013). The calligraphy above the door says “In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful” with a tulip in it. Also, in the pattern of wall ceramic tile, we may find many variants of tulips.

The tulip is also used to represent the virtue of modesty before the Beloved, due to its bowing head when in full bloom (Dash 2000, p. 10). It is believed that the person who grew tulips on hoed soil and watered by the very water that he carried for the purpose to praise God would have a glance of the beauty of Divine Love through the very flower (Uludas and Adiloglu 2011, p. 63). Though the Ottoman Empire met its end, the love for tulips was sustained. A contemporary Sufi master of Istanbul, Osman Nuri Topbas (1942–), calls the knowledge of Rmī as “a bouquet of tulip” Topbas (2010) which is animated with a fire of love in Tears of the Heart. He also declared that the bouquet of tulips and jug of water can lead us to ultimately find the flush of Zamzam water in the gardens of our hearts.

The preceding part of the paper presented Iran (Persia) and Turkey as two cases to explain how different Muslim societies have employed different symbols, such as flowers, from their local context, in order to understand and express the universal and abstract ideas of Paradise and Divine Love. Thus, scriptural Islam can be turned into a practicable life. In what follows in this paper, we focus on the understanding and practices of Chinese Muslim.

3. The Symbol of Peony of the Hui People or Chinese Muslim

As mentioned before, the Hui is distinguished from the other nine Muslim ethnic groups of China by not having a unique language of their own (Gladney 1996, p. 32). They mostly speak the dialects of the language of the Han Chinese and, as a result, they have been labeled as “Chinese-speaking Muslims”. They have called themselves the “Huihui”(回回) since the end of Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), which is a translation of “Muslim”. According to the mainstream opinion of Chinese academics, the Chinese word “Huihui” referred to some particular ethnic group of northwest China, which was first appeared in an 11th century book written by Shen Kuo (1031–1095) entitled Meng Xi Bi Tan (Dream Pool Essays). Since the 13th century, the word “Huihui” has mostly referred to Muslims. After the late 14th century, the word technically referred to all Muslims, whether in China or foreign. However, after 1949, the government identified 56 ethnic groups, of which the Hui was only one of ten Muslim ethnic groups of China. Wang Daiyu (1584–1670), a famous Chinese Muslim scholar of the late Ming dynasty (1368–1644), defined the word “Huihui” in accordance with the Sufi philosophy: “So great Huihui is, a mirror of God, a part of the cosmos, as Hui means return from the earth to God, like a mirror returning light” Wang (1988). The Chinese word “Hui” is formed by two circles which, as determined through discussions of Chinese Muslim theologians, the inner one represents the earth and the outer the sky Zhou and Ma (2009). In the view of this, the name Huihui implies their foreign origin and their religious destiny, which manifests them yearning for the ultimate return to Paradise. As a minority in an overwhelming non-Islamic environment, the Hui has faced many pressures and challenges, which caused them to express their religious identity by using elements borrowed from traditional Chinese culture.

Peony is a native Chinese flower breed which has three cultivar groups in China, distributed in the central plains, northwest, and south of China (Figure 5). In a history of more than two thousand years of peony cultivation, not only colorful peonies have been cultivated, but also the characters and grades of the peony have been constructed in the literature. Chinese scholars have a tradition of appreciating flowers and writing genealogies for all flowers. There are more than 80 genealogies of peonies that have been documented from the 8th to 19th century, including 46 genealogies just about the peony. Hua Jiuxi (Rites of the Flower), was written by Luo Qiu (d. late 9th century) of the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD), which describes nine rites regarding peonies. Jiuxi is a traditional rite, which Chinese emperors award their leading officials with nine kinds of sacrificial utensils. Luo Qiu took the peony as the object of etiquette, according to the Jiuxi rite, which expounds the nine rituals as follows:

Figure 5.

A Courtyard with Peony, Hezhou City (Photo by Zhou Chuanbin, 2014). A common peasant courtyard almost occupied by a flower bed through which one can see the love of peony in northwest China.

Before cutting peonies, people must cover the wind for them.

When people cut peony, they should use the scissors with exquisite carving.

People must use sweet spring, jade jar, and exquisite table to place peony.

When people appreciate the peony, they need to chant poetry, draw, sing, and taste tea.Luo (1934)

Zhang Yi (d. late 10th century), the author of Hua Jing (Scripture of Flowers), divided 71 flowers into nine hierarchies, in which peony was set in the highest hierarchy. In Ping Hua Pu (Genealogy of Vase Flowers), one of the most important handbooks of flowers written by Zhang Qiande (1577–1643) in the Ming dynasty, the structure of the flower hierarchy was emphasized again, where the peony was still in the highest hierarchy. The peony was directly crowned as “Hua” (Flower) in Chinese, while the other flowers can only be called by their typical names. “Throughout the whole world, only peony can be called as the real flower” Ouyang (2011), as Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) said in his famous poem entitled The Peonies of Luoyang. During the same period, Qiu Xuan (d. 11th century), the author of Mudan Rongru Ji (Glory and Disgrace of the Peony), personified Yao-Huang (A yellow peony cultivated by Mr Yao) as the king of flowers, while Wei-Zi (a light red peony cultivated by Mr Wei) was the queen; meanwhile, he stipulated that the other flowers should serve the peony, in order to highlight the honorable status of the peony.

As the Hui people live in and interact with a hegemonic Chinese civilization, Chinese Muslim elites have interpreted Islam through Chinese symbols, in order to express their ethnic-religious identity in a dominantly non-Islamic environment. Although born in the land of China, they have inherited the favor of gardens and flowers from Islamic tradition, which they have combined with Chinese traditions of architecture and symbolism of flowers. The acceptance and application of the peony as a significant symbol by Chinese Muslim is an outstanding case that we can analyze from three aspects: horticulture, literature, and brick carving arts of the Hui people in He-Huang area.

As mentioned before, the so-called He-Huang area refers to a special area which crosses Qinghai and Gansu provinces and is marked by the Yellow River and its branch Huangshui. The He-Huang area is a Muslim-concentrated area and a multi-ethnic area of China. At least four Muslim ethnic groups identified by the government live here: the Hui, the Dongxiang (or Sarta), the Salar, and the Bao’an people. This area is also the geographic and cultural border between Chinese and Tibetans.

3.1. Peony in the Horticulture of the Hui People

The peony is the most precious flower in Hui gardens. The He-Huang area, in the upper reaches of the Yellow River, which is in northwest China, is one of the origins of the peony. Among all blooms in local gardens, the peony is no doubt the noblest one, and different local ethnicities have a common passion for this flower. The city of Hezhou, the capital city of the Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture, is the main planting land of the northwest peony cultivar group with the scientific name as Paeonia Rockii. There is an old poem (“lovely peonies can be found in anywhere, while only in Hezhou can we get the flawless one”) which described the spectacular scenery of local peonies. In the Hui courtyard I visited, two gardens were the most impressive. Seven local peonies were planted in the center of the garden of a courtyard, and two Luoyang peonies were planted beside them. The garden area of another courtyard was small, but it had 40 peonies and more than 10 Chinese herbaceous peonies planted, which showed the householder’s devoted love of the peony. At present, various peonies are planted in all kinds of public spaces, such as parks, courtyards, and even roadsides. In this region, most mosques and Sufi shrines are arranged in accordance with the architectural layout of traditional Chinese courtyards, combined with the unique aesthetics of Chinese gardens (Figure 6). Since 2016, Hezhou has held a peony festival every year, holding more than 40 cultural activities related to peonies. When peonies are in full bloom, every corner of the city is crowded with people. People take delight in inviting their relatives and friends to their private garden to enjoy colorful peonies. In addition to appreciating the peony, people in Hezhou also sing popular folk songs called “Hua-er” (flowers).

Figure 6.

The Taizi Qubbah of Qadriyyah Sufi Order, Hezhou City (Photo by Zhou Chuanbin, 2014). Chinese Muslims call Sufi shrines (tombs of Sufi masters) Qubbah, which means “dome” in Arabic. In the picture, we can see that the Islamic dome is totally transformed into Chinese architecture. We can see blooming peonies in the courtyard.

3.2. Peony in the Literature of the Hui People

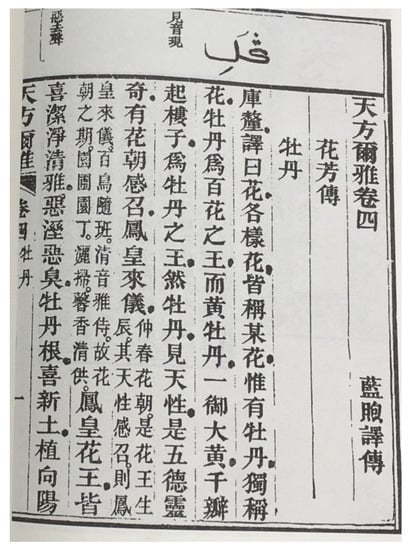

Instead of the rose or tulip, the peony appears as the king of flowers in the Hui people’s universe described through their literature and documents. As mentioned above, the peony is always the most important flower in Chinese tradition. In the middle of the 19th century, a Hui scholar named Lanxu (1813–1976) wrote a book in Chinese entitled Tianfang Erhya (A Lexicographical Book of Arabic and Persian, 天方爾雅), which is a reference book explaining Arabic and Persian words with a philosophy influenced by Confucianism. Lanxu put the peony in the first and highest hierarchy of flowers, he wrote (Figure 7):

Figure 7.

One Page of Tianfang Erhya of Lanxu. Lanxu wrote the Persian word “gol” and its Chinese interpretation as peony on this page. The first letter “g” was not written in a proper style, as in modern Persian.

(gol): Ku-li translates as flower. Only the peony qualified to be called Flower, the other flowers are just some kind of flower.(Wu and Zhang 2010, p. 306)

Just as only rose can be called “Flower” in Persian culture, the peony replaced the symbolic meaning of the rose in Hui culture. Relatively speaking, Lanxu explains just a few words of the rose as “a plant with green stems, thorns, and flowers of five colors” (Wu and Zhang 2010, p. 319), not even annotating it with Persian or Arabic names. The peony occupies the first place among all flowers, which clearly indicates the influence of Chinese tradition. Lanxu recorded the main points of peony planting and described, in detail, 45 peony varieties, including five colors according to Chinese philosophy which we will discuss later. In the book, he vividly described the legendary story of the meeting between the phoenix emperor and the peony:

The peony is the king of all flowers, while the Yellow peony is the king of all peonies. As a crystal of the five virtues of Confucianism, Peony has a unique spirit that make the Phoenix special come to visit in the flower festival. Both the Phoenix and the peony like cleanliness and elegance. The flower festival is the birthday of the peony in second month of spring. Many birds follow the Phoenix to worship the peony. They sing softly while serving the peony. So, gardeners need to take care of the peonies during the flower festival.(Wu and Zhang 2010, p. 306)

Lanxu not only emphasized the peony as the king of flowers, but also followed the Chinese tradition of divide peonies into three categories of color symbolism: yellow, red, and white. From the Song dynasty (960–1279) to the Qing dynasty (1636–1912), over 700 years, Chinese elites ranked different peonies by ordering the colors, in which the yellow one is the noblest as it was the symbolic color of the emperor. This preference for yellow is reflected in the hierarchy of peonies, in that a peony named “Yu Da Huang” (the Royal Yellow) was chosen as the king of peonies. Lanxu put forward that “we can glance the essence of God from the beauty of the peony which is a miracle of five virtues” (Wu and Zhang 2010, p. 306). Benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and sincerity are called the “Five Virtues” of Confucianism, which are the most holy virtues in Chinese civilization (Wu and Zhang 2010, p. 350). The Hui practiced the Five Pillars (Shahadah, Salat, Ramadan, Zakat, and Hajj) of Islam, which correspond to the Five Confucian Virtues. As we know, according to Islamic philosophy inherited from ancient Greek philosophy, the Human world is the lower bound, under the Moon, in the whole Ptolemic Universe, which is formed of four primary elements: earth, fire, water, and air. Generally speaking, Islam has Four Pillars without the Shahadah. It is Chinese Muslims who changed the contents of the philosophy to adapt to the Five-element Theory, which is very basic in all kinds of Chinese learnings, whether Confucianism or Daoism. The Five-elements Theory is based on the five material elements—metal, wood, water, fire, and earth—which correspond to the five directions, the five virtues of Confucianism, the five colors, the five sense organs, and so on (Table 2). Thus, we can see the localization of Islam in China. By using the concepts, symbols, and theories of traditional China, Chinese Muslim scholars had successfully constructed a new system of interpretations of Islam until the 17th to 18th century.

Table 2.

Peony Metaphors and the Chinese-Islamic Philosophy.

From philosophy to folk literature, Hua-er (花儿) is a style of folk song popular among all ethnic groups in northwest China, in which “peony” is always used as a metaphor of “lover” in its librettos. According to statistics, The Collection of Northwest Hua-er has 640 librettos, of which 174 librettos are associated with flowers. Of all librettos in connection with flowers, the peony appears 74 times, accounting for 42% of the total Wu (2008). The Songmingyan Hua-er Festival in Hezheng county of Gansu province is held from 26 to 28 April of the lunar calendar. During the days of the festival, men and women from all over the region gather at the foot of the mountain to start a campaign of singing folk songs. We took part in the festival on 24 May 2014. You can see people of different ethnic backgrounds sitting together, including many Muslims, mostly middle-aged and elderly people. Only sporadic women participated in the festival. According to our observation, after the singer’s voice was raised, people would automatically surround him/she, holding mobile phones or small radios to record. Traditionally, it is an improvised sing-and-response between men and women to express love. The lyrics are all in the Hezhou Chinese dialect and, thus, formed an oral tradition of that region. Love is the eternal theme of Hua-er, where the beloved is often compared to a peony:

In the garden, no other flower is more beautiful than the peony.

In the crowd, no one is more handsome than my boy.

The boy took a fancy to the red peony, while the red peony fell in love with the boy.Wang (2007)

Ma Zaiyuan, a Chinese Sufi writer, has compared the social situations of Hua-er with Sufi poems, in that both of them, on the surface, are texts describing love stories between the lover and the Beloved, which are both rejected by the Muslim orthodox ullamas Ma (2016). In addition, he came up with another similarity: that Hua-er was considered to be indecent songs, while Sufi poems praising the Divine Beloved were rejected by scholars of Sharia and Fiqh. Therefore, the folk song Hua-er and Sufi orders of the He-Huang area have an emotional resonance to yearn for the Divine Beloved. As it is written in the librettos:

The peacock loves the peony, and the honey loves the white flower.(Li and Yang 2012, p. 207)

The lover is a peacock in the sky, and the Beloved is a blooming peony.(Li and Yang 2012, p. 434)

Although Hua-er are colloquial librettos, the peacock as a seeker in the pursuit of the peony would naturally let us remember the love story between the nightingale and the rose in Hfiz’s poems:

I’m a nightingale, falling silent during the time of roses.(Hafiz 2006, p. 160)

3.3. Peony in the Arts of Brick Carving of the Hui

It is said that the Chinese brick carving art originated between the 8th BC to 3rd centuries BC. In the 11th century, Li Jie (1035–1110) divided the symbols of brick carvings into 11 kinds in his book Ying Zao Fa Shi (Methods of Building):

There are 11 kinds of symbols. The first symbol is a pomegranate flower. The second is a design of composite flowers. The third is a peony. The fourth is a species of orchid. The fifth is a cloudy symbol. The sixth is a water ripple. The seventh is a mountain. The eighth is a symbol of steps. The ninth is the lotus flower covering the ground. The tenth is the lotus flower with drooping petals. The eleventh is the Lotus flower in a porcelain bottle.Li (2006)

From the 14th to 19th century, the themes of brick carvings became more and more abundant, mainly focusing on praying for blessings, warding off evil spirits, and ethical education. At the same time, the development of Chinese folk art brought many auspicious symbols into brick carvings, such the Yin and Yang (the life of the cosmos), bat (homophonic with happiness), peach (longevity), many kinds of flowers (different virtues) and so on. In this Chinese tradition, peony is the symbol of riches and honor (富贵花).

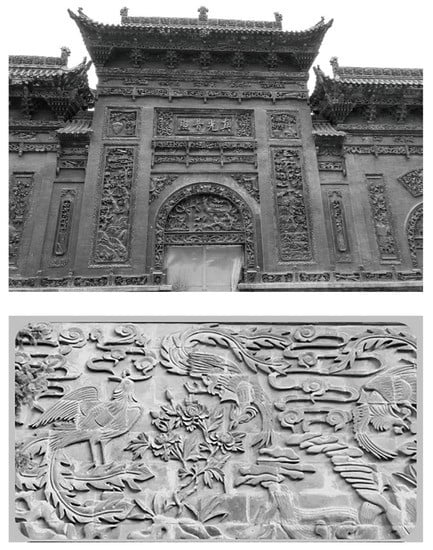

The peony is also one of the main themes in the architectural brick carving arts of the Hui Muslim in the He-Huang area. If it seems far-fetched to be comparing the love of folk songs to the love of Sufi poems, we may be able to resolve this doubt when we see various peonies among the brick carvings. The Hui literature, Tianfang Erhya (天方爾雅) and the folk song Hua-er (花儿) have constructed the symbolic significance of the peony, which has been interpreted and visually expressed by the brick carving arts. The peony, the king of flowers and the object of love, symbolizes not only Paradise and the hidden world of eternal reality, but also a visual expression of the Divine Beloved in Sufi mysticism. Among the brick carvings of mosques and Sufi shrines in the He-Huang area, the peony can be seen in different patterns at different positions of the architectures. It may be in the center of the whole brick wall, in pairs with the lotus or Phoenix, as well as in the border line of rectangular brick wall or its four corners. When the peony becomes the center of the whole wall space, as in most cases, the phoenix will be its partner. For example, in Lingmingtang Qubbah of Gansu province, a Qadriyyah Sufi shrine dedicated to the former Sufi master Ma Lingming (1853–1925), a scene entitled “Phoenix Playing with Peony” is a main theme on the brick carving screen wall of the Shrine, in which two phoenixes are flying beside a peony. In Machangyuan Qubbah of Qinghai province, a Qadriyyah Sufi shrine dedicated to Aunt Cai, a famous female Sufi master of the 18th century, there is a main brick carving screen wall called “One Hundred Phoenixes”, with a blooming peony in the center surrounded by seven phoenixes. The keeper of the shrine told us: “Love is the sole reason that can make phoenixes always on peony’s side” Guo (2019) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Brick Carving of Two Sufi Shrines in Qinghai province (Photo by Zhou Chuanbin, 2017). Upper: the brick carving gate of Shanghezhong Qubbah dedicated to a Qadriyyah Sufi master Yang Baoyuan (1780–1873), on which one can see trees, flowers, and phoenixes. Under: This is part of the screen wall titled “One Hundred Phoenixes”, with a peony in the center, in Machangyuan Qubbah. Perhaps it is because the Shrine is dedicated to a female Sufi master that made the designer to put so many phoenixes around one peony (both phoenix and peony can be a female symbol in China).

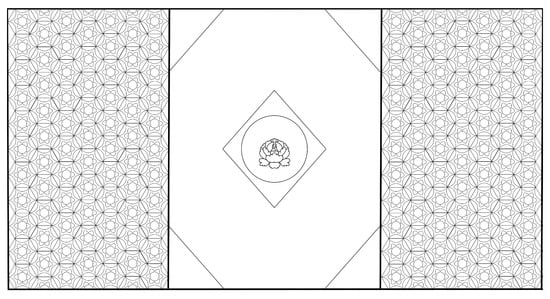

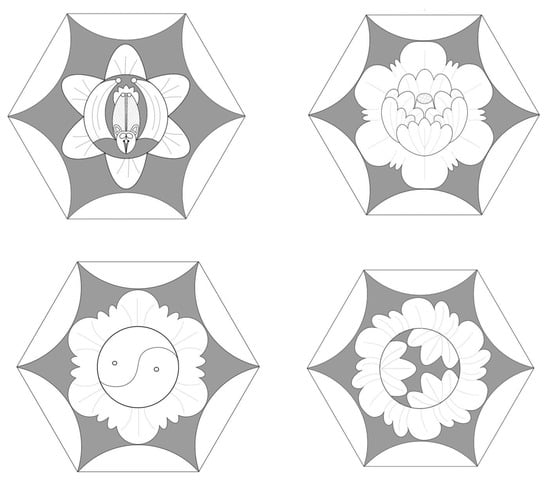

In other cases, only the peony plays the leading role of the brick carving. In Houzihe Qubbah of Qinghai province, a shrine also dedicated to Yang Baoyuan (1780–1873), peonies became the core of the entire brick carving wall, surrounded by dozens of flowers (Figure 9). The screen wall of Hongshuiquan Mosque in Qinghai Province is another model of this kind of artistic style, with similar heavy and complicated figures as those in Persia and Andalusia. The screen wall entitled “One Hundred Flowers” contains 255 consecutive but different peony symbols. The hearts of these peony symbols are not only carved with a variety of budding flowers, but also Chinese traditional auspicious symbols such as the Yin and Yang, bat, and peach, and even food, such as noodles (Figure 10). This style of brick carving composition is characterized by using consecutive peony symbols to form a regular geometric figure as a whole, as well as irregular figures in detail. These peony show abstract and artistic designs, with petals in various shapes and the flower cores composed of different symbols. It is very interesting that the style is extremely popular across ethnicities and religions, from mosques and Sufi shrines to Buddhist and Daoist temples.

Figure 9.

Composition of Brick Carving in Houzihe Qubbah of Qinghai province (by Guo Lanxi, 2018).

Figure 10.

Different Peony Sculptures in the Brick Carving of Hongshuiquan Mosque of Qinghai province (by Gou Lanxi, 2018). The screen wall of this mosque has 255 different peony sculptures. In these four examples, we can see different flower hearts as bat, the Taiji Diagram, blooming, and half-blooming peonies.

We mention also the architecture of Guandi temple (Daoism) of Guide county of Qinghai province, Qutan Temple (Tibetan Buddhism) of Ledu county of Qinghai province, Miaoyin Temple (Tibetan Buddhism) of Yongdeng county of Gansu province, Houzihe Qubbah of Datong county of Qinghai province, and Hongshuiquan Mosque of Ping’an county of Qinghai province, and so on. It is obvious that there is a kind of common aesthetic throughout different ethnic groups of different religions in the area. The Muslims, Tibetans, and Chinese Buddhists or Taoists all share the same feeling of aesthetics of architecture and prefer the same symbolic system of flowers. Otherwise, the Chinese Muslims have drawn a new interpretation, both to the Chinese symbols and Islamic learnings. They have successfully linked the Islamic doctrine to the local Chinese symbols. As in the case of the peony, Chinese Muslims have successfully employed this Chinese flower (traditionally a symbol of riches and honor in China) to express their understanding of Islamic Paradise, by using it as the Divine flower; comparative with the rose of Persia and the tulip of Turkey. This is a story about acculturation and innovation, both in one process of the practice of the Hui people in China. A new cultural pattern came into being, belonging as much to the Islamic tradition as to the Chinese tradition.

4. Conclusions

The anthropological approach is very necessary for traditional Islamic studies, due to its methods and theories. Islamic studies never lack scholars in their armchairs. As William C. Chittick argued, the theologians (mutakallimun) based their explications of God’s Oneness on the evidence provided by the Qur’an and the Hadith; the philosophers (mushsha’iyyun) tried to prove God’s Unity by appealing to human intellect; while the Sufis sought for direct visions from God Chittick and Wilson (2001). The scholars of each school have all tried to guide believers to the right road they had found so much that real life was forgotten. Anthropologists, whether Muslim or not, are trying another way to explain human beings in their everyday lives. Every culture is a universe; the saying rather means that every culture has a unique understanding of the only universe we have.

In such a background, Islamic anthropology or Islamic studies of anthropology argue that one may see “Islam” as the macrocosm which has been concretely converted into various “Islams” as a microcosm in each localized scene M.el-Zein (1974). In the process of Islam spreading beyond the Arabian Peninsula, more and more nations and ethnicities have brought their local knowledge into the cultural interpretations of Paradise, such that each interpretation corresponds to a particular type of localization of Islam. Neither the stereotype of Islam that pervades the world’s media, nor the homogeneous imagination of Islamic fundamentalists, is the real picture of Islam in our world.

The multiple interpretations and local practices of Islam are the most accurate understanding of al-tawhī d, which is the core concept of Islam. Just as the Islamic cosmology expresses, the phenomenal world is plentiful and varied, such that each entity is a specific mode of a specific possibility (mumkin) Chittick (2012), as each represents a mode through which a light of God can be limited, determined, specified, and defined. The Oneness of Allah and the Multiplicity of the world are just a pair of the symbiotic relationship in the Islamic cosmology, which is based on the emphasis upon Allah as the Unique Origin of all entities; in Seyyed Hossein Nasr’s words, “the hierarchy of existence which relies upon the One and is order by His command” Nasr (1987). Furthermore, Rmī compared this world to a mirror, in which the beauty of love is displayed in order to epitomize the idea of God’s creative love, where love brings about separation, distinction, and multiplicity Chittick (1993). Therefore, the localization of Islam will not cause Islam to lose its essential attributes but, instead, to adapt to changes in external styles of the specific conditions of the areas where Muslims live, describing the production of Islamic traditions within particular social contexts and through particular cultural understandings Bowen (2012). Due to transformations of these local styles by local knowledge, a realistic, diverse, and living Islam is displayed.

The Hui people, or Chinese Muslims, give us a unique case to explore the amazing encounter between the Islamic civilization and Chinese civilization. One of the fresh fruit from this encounter is a series of books written in Chinese by the Hui scholar given the name Han Kitab. A classical Chinese-Islamic tradition thus has come into being since the 17th century, with the main authors being Wang Daiyu (d. 1670), Ma Zhu (d. 1711), Wu Zixian (d. 1678), and Liu Zhi (d. ca. 1764). As we mentioned above, Sachiko Murata, William C. Chittick, Tu Weiming, and Seyyed Hossein Nasr have paid more attention to this issue, to the extent that profound achievements have been made. It is clear that these authors wrote their works based on several Persian and Arabic resources, which mainly belong to a certain Persia Ibn Arabi school of theoretical Sufism (Wang 2012; Zhou 2020). The authors of Han Kitab tried to express Islamic thoughts in Confucian terms, which showed the in-depth intercourse between the two civilizations. However, there remain questions: Besides the intellectual level, how much were these Han Kitab accepted by the Muslim crowd? Is there any cultural exchange and integration at the grass-roots level between Muslims and Han Chinese? Our fieldwork and studies are expected to answer these questions.

Based on fieldwork in northwest China and comparative cross-cultural research from China to Iran and Turkey, by focusing on the cultural detail of the image of Paradise and flowers as a symbol of Divine Love, this paper discusses how roses, tulips, and peonies were chosen by certain Muslim societies and ethnic groups, to act as the symbol and metaphor of the only Beloved they seek forever.

Flowers, as the symbol of the Divine Love, have become an important local practice of Islam by Sufi literature. The heart will forget the fear for God when it is filled with love; then the relationship between human and God is no longer a fear, but a relationship between the lover and the beloved. Therefore, the process of religious practices has been aestheticized, such that compulsory religious works have already been changed into the pursuit of the Divine Beloved. Love can heal our sense of separation and guide our soul to reunite with the Divine Unity. To quote Rmī’s poem,

Love is the astrolabe of all we seek.

Whether you feel divine or earthly love,

Ultimately we’re destined for above.(Rumi 2004a, p. 11)

Except for the localization of Islam and its practice in everyday life, as in horticulture, folk song, literature, brick carving arts, and architecture, this paper attempts to move forward the discussion regarding the sharing of common symbols in a multi-ethnic area. As a core symbol of Chinese tradition, the peony and its artistic form has been successfully accepted cross-culturally by Chinese, Muslims, Tibetans, and other ethnic groups living in northwest China. However, different people give a distinct interpretation of the same symbol. As in the case of peony, Chinese people love it because it is a symbol of the riches and honor they want in this life; Muslims gave new meaning from Islamic tradition to this flower, seeing the peony as the metaphor of the eternal life in Paradise; and the Tibetans interpret peonies as a kind of lotus growing on dry land, which obviously reflects their Buddhist background. Geographical and ecological conditions thus demonstrate an impact on culture: Human beings adapt to their environment and use cultural systems as a means and tool to understand, interpret, and renew their natural and social circumstances at the same time. Not only to make peace with Nature, but also to make peace with people outside of our group and culture, the practices of Chinese Muslims have offered a story of success. So long as this history continues, this cultural process will be maintained.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and L.G.; methodology, C.Z.; formal analysis, C.Z.; investigation, C.Z. and L.G.; resources, C.Z.; data curation, L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.Z. and L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Foundation: Annotation and Research of the Ashi’at al-Lama’, grant number 19VJX138.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdo, Zainakhan. 2015. 审美视野下维吾尔语“gül”的隐喻义及其翻译 [The Symbolic Significance and Translation of Uygur Word “gül" in the Aesthetic Perspective]. Journal of Kashgar Teachers College 26: 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Alles, E´lisabeth. 2000. Musulmans de Chine: Une Anthropologie des Hui du Henan. Paris: EHESS. [Google Scholar]

- Atwill, David G. 2005. The Chinese Sultanate: Islam, Ethnicity, and the Panthay Rebellion in Southwest China, 1856–1873. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baldock, John. 2005. The Essence of RUMI. New York: Chartwell Books, p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Benite, Zvi Ben-Dor. 2005. The Dao of Muhammad: A Cultural History of Muslims in Late Imperial China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge, Annette Susannah. 2020. The Bābur-nāmā in English. Frankfurt am Main: Outlook Verlag GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, John R. 2012. A New Anthropology of Islam. New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Broomhall, Marshall. 1987. Islam in China: A Neglected Problem. London: Darf Publishers Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William C., and Peter Lamborn Wilson. 2001. Divine Flashes (Lama’āt). Lahore: Suhail Academy, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William C. 1983. The Sufi Path of Love: The Spiritual Teachings of Rumi. Albany: State University of New York Press, p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William C. 1993. The Spiritual Path of Love in Ibn al-’Arabi and Rumi. Mystics Quarterly 19: 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William C. 2012. Ibn ’Arabi: Heir to the Prophets. London: Oneworld Publications, p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, Louisa Stuart. 1845. The Rose Garden of Persia. London: Longmans. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, Mike. 2000. Tulipomania: The Story of the World’s Most Coveted Flower and the Extraordinary Passions It Arouse. New York: Three Rivers Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dilon, Michael. 1999. China’s Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. London: Curzon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary. 1978. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Erie, Matthew S. 2016. China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Farahani, Leila Mahmoudi, Bahareh Motamed, and Elmira Jamei. 2016. Persian Gardens: Meanings, Symbolism and Design. Landscape Online 46: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Joseph F., and Beatrice Forbes Manz, eds. 1995. Studies on Chinese and Islamic Inner Asia. Aldershot: Variorum. [Google Scholar]

- Ganjavi, Nezami. 2015. The Haft Paykar: A Medieval Persian Romance. Translated by Meisami Julie Scott. Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Culture: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 2008. Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gillette, Maris B. 2000. Between Mecca and Beijing: Modernization and Consumption among Urban Chinese Muslims. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gladney, Dru C. 1996. Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Lanxi. 2019. 从富贵花到两世花: 回族文化中的牡丹 [From Symbol of Wealth to Symbol of Two World’s Blessing: Peony in the Hui culture, Based on Survey of Bafang Hui Community, Linxia, Gansu Province]. Chinese Muslim 2: 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hafiz. 2006. The Poems of Hāfiz. Translated by Shahriar Zangeneh. Rockville: Bethesda, Ibex Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hattstein, Markus, and Peter Delius. 2004. Islam Art and Architecture. Potsdam: Tandem Verlag GmbH, p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Israeli, Raphael. 1979. Muslims in China: A Study in Cultural Confrontation. London: Curzon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Israeli, Raphael. 1994. Islam in China:A Critical Bibliography. London: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschok, Maria, and Jingjun Shui. 2000. The History of Women’s Mosques in Chinese Islam: A Mosque of Their Own. London: Curzon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khansari, Mehdi, M. Reza Moghtader, and Minouch Yavari. 2004. The Persian Garden: Echoes of Paradise. Washington, DC: Mage Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kive, Solmaz Mohammadzadeh. 2012. The Other Space of Persian Garden. Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences 2: 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Latiff, Zainab Abdul, and Sumarni Ismail. 2016. The Islamic Gardens: Its Origin and Significance. Research Journal of Fisheries and Hydrobiology 11: 82. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, Donald Daniel. 1981. Islamic Literature in Chinese Late Ming and Early Qing: Books, Authors and Associates. Canberra: Canberra College of Advanced Education. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xue, and Ke Yang. 2012. 西北花儿精选 [An Omnibus of Northwest Hua’er]. Xining: Qinghai People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jie. 2006. 营造法式 [Methods of Building]. Beijing: People’s Publishing House, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Lipman, Jonathan N. 1997. Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslim in Northwest China. Seattlte and London: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yingsheng. 2008. ⟪回回馆杂字⟫与⟪回回馆译语⟫研究 [<Huihui Guan Zazi> and <Huihui Guan Yiyu> Researches]. Beijing: China Renmin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lumbard, Joseph. 2007. From Ḥubb to ‘Ishq: The Development of Love in Early Sufism. Journal of Islamic Studies 18: 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Qiu. 1934. 花九锡 [Rites of the Flower]. Great Collection of Ancient and Modern Books (No. 531). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- M.el-Zein, Abdul Hamid. 1974. A Sacred Meadows: A Structural Analysis of Religions Symbolism in an East African Town. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Haiyun, and Chuanbin Zhou. 2001. 伊斯兰教在西北苏非社区复兴说质疑 [Querying on the Islamic Revival in a Sufi Community of Northwest: A Recognition of Najiahu Village of Ningxia]. Minzu Yanjiu 5: 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Zaiyuan. 2016. 白牡丹令 [Song of the White Peony]. Minzu Wenxu 5: 102–20. [Google Scholar]

- Meisami, Julie Scott. 1985. Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez. International Journal of Middle East Studies 17: 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, Sachiko, William C. Chittick, and Weiming Tu. 2009. The Sage Learning of Liu Zhi: Islamic Thought in Confucian Terms. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murata, Sachiko. 2000. Chinese Gleams of Sufi Light. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, and Oliver Leaman. 1996. History of Islam Philosophy. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. 1987. Islamic Art and Spirituality. Albany: State University of New York Press, p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. 2009. Foreword. In The Sage Learning of Liu Zhi: Islamic Thought in Confucian Terms. Edited by Sachiko Murata, William C. Chittick and Weiming Tu. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nazia, Ansari. The Islamic Garden. Ahmedabad: CEPT Universit, p. 11.

- Ouyang, Xiu. 2011. 牡丹谱 [The Genealogy of Peony]. Edited by Yang Linkun. Beijing: Zhong Hua Book Company, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Pickthall, Marmaduke. 1996. The Meaning of the Glorious Qur’an: Explanatory Translation. Beltsville: Amana Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rumi, Jalal al-Din. 1997. The Essential Rumi. Translated by Coleman Barks, and John Moyne. Secaucus: Castle Books, p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Rumi, Jalal al-Din. 2004a. The Masnavi Book One. Translated by Jawid Mojaddedi. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rumi, Jalaluddin. 2004b. The Mathnawi of Jalaluddin Rumi. Translated by Reynold A. Nicholson. Istanbul: YAZIEVİİLETİSİM HİZMETLERİ, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Rumi, Jalal al-Din. 2013. The Masnavi Book Three. Translated by Jawid Mojaddedi. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Sadi Shira, Shekh Muslihu’D-Din. 2002. The Gulistan: Or Rose-Garden of Shekh Muslihu’D-Din Sadi Shira. Translated by Edward B. Eastwick. Oxford: Routledge, p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel, Annemarie. 1975. Mystical Dimensions of Islam. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian, Günther, and Todd Lawson. 2016. Roads to Paradise: Eschatology and Concepts of the Hereafter in Islam. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, pp. 137–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tapper, Richard. 1995. “Islamic Anthropology" and the “Anthropology of Islam”. Anthropology Quarterly 68: 185–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topbas, Osman Nuri. 2010. Tears of the Heart: From the Garden of the Mathnawi: Rumi Selections. Translated by Sencer Ecer, and Abdullah Penman. Istanbul: Erkam Publications, p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Toshihiko, Izutsu. 1992. 伊斯兰教思想历程: 凯拉姆·神秘主义·哲学 [Development of Islamic Thoughts: Kalām, Tasawwuf, Falsafah]. Translated by Hui-Bin Qin. Beijing: China Today Press, pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Uludas, Burcu Alarslan, and Fatos Adiloglu. 2011. Islamic Gardens with a Special Emphasis on the Ottoman Paradise Gardens: The Sense of Place between Imagery and Reality. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies 1: 44. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Daiyu. 1988. 正教真诠 · 清真大学 · 希真正答 [The Real Commentary to the Ture Teaching; Great Learning; The True Answers]. Collated by Zhengui Yu. Yinchuan: Ningxia People’s Publishing House, p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Pei. 2007. 中国花儿曲令全集 [The Complete Collection of Chinese Hua’er]. Lanzhou: Gansu People’s Publishing House, p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xi. 2012. 理论苏非学的体系架构和思想内涵 [The System Structure and Ideological Contents of the Theoretical Sufism]. World Religion Studies 4: 160–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, Andrew. 2011. The Dual Mystical Concepts of Fanā’ and Baqā’ in Early Sūfism. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 38: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, Norman. 1945. “Material for the Study of the Ssŭ I Kuan 四夷(譯)館" (Bureau of Translators). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 11: 617–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Jianwei, and Jinhai Zhang. 2010. 回族典藏全书 [The Complete Collection of Hui Classics]. Yinchuan: Ningxia People’s Publishing House, vol. 222. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Yulin. 2008. 中国花儿通论 [A Survey of Chinese Hua’er]. Yinchuan: Ningxia People’s Publishing House, p. 429. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Chuanbin, and Xuefeng Ma. 2009. Development and Decline of Beijing’s Hui Muslim Community. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Chuanbin. 2020. 《昭元秘诀》的成书与流传 [The Completion and Spread of Ashi’at al- Lama’āt. Chinese Muslim 2: 16–25. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).