Knowledge and Learning of Interreligious and Intercultural Understanding in an Indonesian Islamic College Sample: An Epistemological Belief Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Epistemological Belief

2.2. Belief about Knowledge and Belief about Learning

2.3. Religious Fundamentalism

2.4. Islamic Study and Millennial Students

2.5. Knowledge and Learning with Religious Fundamentalism

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Variable Measurement

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Model Testing Criteria

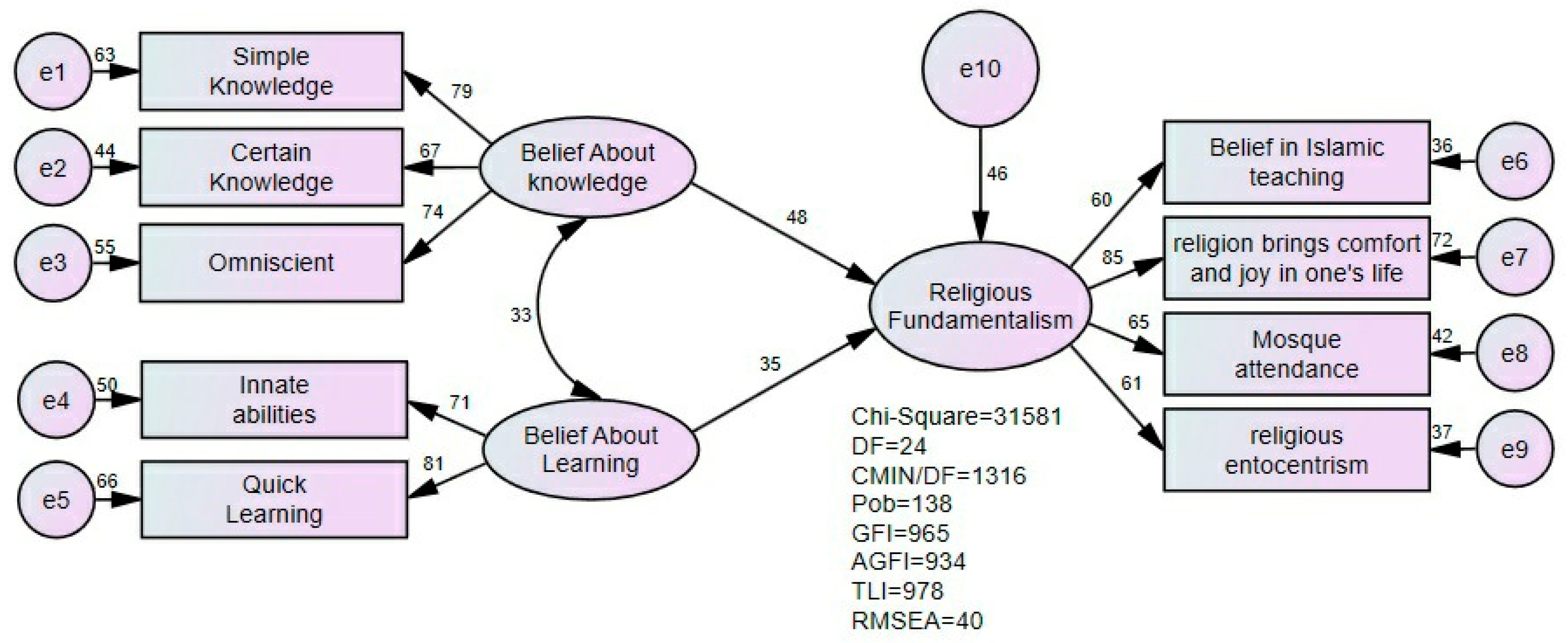

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5. Hypothesis Testing

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, Tahir, ed. 2013. Muslim Britain: Communities under Pressure. London: Zed Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, Gabriel A., R. Scott Appleby, and Emmanuel Sivan. 2003. Strong Religion: The Rise of Fundamentalisms around the World. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer, Bob, and Bruce Hunsberger. 1992. Authoritarianism, Religious Fundamentalism, Quest, and Prejudice. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, Bob, and Bruce Hunsberger. 2005. Fundamentalism and Authoritarianism. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 378–93. [Google Scholar]

- Arifianto, Alexander R. 2018. Islamic Campus Preaching Organizations in Indonesia: Promoters of Moderation or Radicalism? Asian Security 15: 323–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkun, Michael. 2012. Millennialism and Violence. Millennialism and Violence. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenky, Mary Field, Blythe McVicker Clinchy, Nancy Rule Goldberger, and Jill Mattuck Tarule. 1986. Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bendixen, Lisa D., and Deanna C. Rule. 2004. An Integrative Approach to Personal Epistemology: A Guiding Model. Educational Psychologist 39: 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, Michael. 1998. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Desimpelaere, Pascal, Filip Sulas, Bart Duriez, and Dirk Hutsebaut. 1999. Psycho-Epistemological Styles and Religious Beliefs. International Journal of Phytoremediation 21: 125–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Michael O., and David Hartman. 2006. The Rise of Religious Fundamentalism. Annual Review of Sociology 32: 127–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinand, Augusty. 2000. Structural Equation Modeling dalam Penelitian Manajemen. Semarang: Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro. [Google Scholar]

- Ghozali, Imam. 2008. Model Persamaan Struktural: Konsep dan Aplikasi dengan Program Amos. Semarang: Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro. [Google Scholar]

- Ghufron, M. Nur. 2020. Epistemological Beliefs and Mediating Role of Learning Approaches on Social Attitudes of SHS Students. Universal Journal of Educational Research 8: 202–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, Farid. 2014. Shifting Borders: Islamophobia as Common Ground for Building Pan-European Right-Wing Unity. Patterns of Prejudice 48: 479–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathcoat, John D. 2004. ‘Religious Fundamentalists’ Epistemic Beliefs and Relationship to Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Bachelor’s thesis, Faculty of the Graduate College, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma. [Google Scholar]

- Herring, Susan C. 2008. Questioning the Generational Divide: Technological Exoticism and Adult Constructions of Online Youth Identity. In Youth, Identity, and Digital Media. Edited by David Buckingham. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, Barbara K. 2001. Personal Epistemology Research: Implications for Learning and Teaching. Educational Psychology Review 13: 353–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, Barbara K., and Paul R. Pintrich. 1997. The Development of Epistemological Theories: Beliefs about Knowledge and Knowing and Their Relation to Learning. Review of Educational Research 67: 88–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, Ralph W., Peter C. Hill, and William Paul Williamson. 2005. The Psychology of Religious Fundamentalism. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Neil, and Strauss Willam. 2000. Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Iannaccone, Laurence R. 1997. Toward an Economic Theory of ‘Fundamentalism’. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) 153: 116. [Google Scholar]

- Ignazi, Piero. 1992. The Silent Counter-revolution: Hypotheses on the Emergence of Extreme Right-wing Parties in Europe. European Journal of Political Research 22: 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israeli, Raphael. 2017. Muslim Anti-Semitism in Christian Europe: Elemental and Residual Anti-Semitism. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehng, Jihn Chang J., Scott D. Johnson, and Richard C. Anderson. 1993. Schooling and Students′ Epistemological Beliefs about Learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology 18: 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juergensmeyer, Mark. 2003. The Religious Roots of Contemporary Terrorism. In The New Global Terrorism: Characteristics, Causes, Controls. Edited by David C. Rapoport and Charles W. Kegley. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, pp. 185–93. [Google Scholar]

- Juergensmeyer, Mark. 2017. Terror in the Mind of God, Fourth Edition. Terror in the Mind of God, Fourth Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldor, Mary. 2012. New and Old Wars: Organised Violence in a Global Era, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, Patricia M., and Karen Strohm Kitchener. 1994. Developing Reflective Judgment: Understanding and Promoting Intellectual Growth and Critical Thinking in Adolescents and Adults. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- King, Patricia M., and Marcia B. Baxter Magolda. 1996. A Developmental Perspective on Learning. Journal of Collage Student Development 37: 163–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A., Ralph W. Hood, and Gary Hartz. 1991. Fundamentalist Religion Conceptualized in Terms of Rokeach’s Theory of the Open and Closed Mind: New Perspectives on Some Old Ideas. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion 3: 157–79. [Google Scholar]

- Klaczynski, Paul A., and Billi Robinson. 2000. Personal Theories, Intellectual Ability, and Epistemological Beliefs: Adult Age Differences in Everyday Reasoning Biases. Psychology and Aging 15: 400–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knutsen, Terje. 2016. A Re-Emergence of Nationalism as a Political Force in Europe? In Democratic Transformations in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities. Edited by Yvette Peters and Michaël Tatham. London: Routledge, pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, Deanna. 1999. A Developmental Model of Critical Thinking. Educational Researcher 28: 16–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, Jamaludin Hadi, and Sulistiyono Susilo. 2020. Intercultural and Religious Sensitivity among Young Indonesian Interfaith Groups. Religions 11: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laythe, Brian, Deborah Finkel, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2001. Predicting Prejudice from Religious Fundamentalism and Right-Wing Authoritarianism: A Multiple-Regression Approach. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liht, Josέ, Lucian Gideon Conway, Sara Savage, Weston White, and Katherine A. O’Neill. 2011. Religious Fundamentalism: An Empirically Derived Construct and Measurement Scale. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 33: 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marranci, Gabriele. 2009. Understanding Muslim Identity: Rethinking Fundamentalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkman, Ruth. 2017. A New Political Generation: Millennials and the Post-2008 Wave of Protest. American Sociological Review 82: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, Derek E., Erika Sandberg, and Alissa Zimmerman. 2005. Folk Epistemology in Religious and Natural Domains of Knowledge. Journal of Psychology & Christianity 24: 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, William G. 1970. Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Growth in the College Years: A Scheme. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Zhongtang. 2006. A Cross-Cultural Study of Epistemological Beliefs and Moral Reasoning between American and Chinese College Students. Ph.D. thesis, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ricco, Robert B. 2007. Individual Differences in the Analysis of Informal Reasoning Fallacies. Contemporary Educational Psychology 32: 459–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesebrodt, Martin, and Pious Passion. 1993. The Emergence of Modern Fundamentalism in the United States and Iran. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Michael P. 1984. Monitoring Text Comprehension: Individual Differences in Epistemological Standards. Journal of Educational Psychology 76: 248–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sageman, Marc. 2008. A Strategy for Fighting International Islamist Terrorists. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 618: 223–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Alex. 2011. The Routledge Handbook of Terrorism Research. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schommer, Marlene. 1990. Effects of Beliefs about the Nature of Knowledge on Comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology 82: 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer, Marlene. 1994. An Emerging Conceptualization of Epistemological Beliefs and Their Role in Learning. In Beliefs about Text and Instruction with Text. Edited by Ruth Garner and Patricia A. Alexander. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schommer, Marlene. 2004. Explaining the Epistemological Belief System: Introducing the Embedded Systemic Model and Coordinated Research Approach. Educational Psychologist 39: 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, Gregory. 2001. Current Themes and Future Directions in Epistemological Research: A Commentary. Educational Psychology Review 13: 451–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilka, Bernard, Ralph W. Hood, Bruce Hunsberger, and Richard Gorsuch. 2003. The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach, 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Daniel P. 2007. Tinder, Spark, Oxygen, and Fuel: The Mysterious Rise of the Taliban. Journal of Peace Research 44: 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, Iris, and Michael Weinstock. 2008. A Sociocultural Exploration of Epistemological Beliefs. In Knowing, Knowledge and Beliefs: Epistemological Studies across Diverse Cultures. Edited by Myint Swe Khine. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandafyllidou, Anna, and Hara Kouki. 2013. Muslim Immigrants and the Greek Nation: The Emergence of Nationalist Intolerance. Ethnicities 13: 709–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, Abdurrahman. 2009. Ilusi Negara Islam-Ekspansi Gerakan Islam Transnasional di Indonesia. Jakarta: The Wahid Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuni, Fitri. 2019. Causes of Radicalism Based on Terrorism in Aspect of Criminal Law Policy in Indonesia. Jurnal Hukum Dan Peradilan 8: 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarkasyi, Hamid Fahmy. 2018. Knowledge and Knowing in Islam: A Comparative Study between Nursi and Al-Attas. Global Journal Al-Thaqafah 8: 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zerin, Edward. 1995. Methods of Human Knowing. Transactional Analysis Journal 25: 150–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belief about Knowledge | 195 | 14.33 | 6.056 |

| Belief about Learning | 195 | 12.78 | 6.202 |

| Religious Fundamentalism | 195 | 26.14 | 6.357 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 195 |

| Index | Cut-Off-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square | 31.581 | |

| CMIN/DF | 76.527/60 | 1.316 |

| Significance | >0.05 | 0.138 |

| RMSEA | <0.05 | 0.040 |

| GFI | 0.90 | 0.965 |

| AGFI | 0.90 | 0.934 |

| TLI or IFI | 0.95 | 0.978 |

| Hypothesis | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belief about Knowledge on Religious Fundamentalism | 0.343 | 0.075 | 4.585 | 0.000 |

| Belief about Learning on Religious Fundamentalism | 0.229 | 0.072 | 3.202 | 0.001 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghufron, M.N.; Suminta, R.R.; Kusuma, J.H. Knowledge and Learning of Interreligious and Intercultural Understanding in an Indonesian Islamic College Sample: An Epistemological Belief Approach. Religions 2020, 11, 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11080411

Ghufron MN, Suminta RR, Kusuma JH. Knowledge and Learning of Interreligious and Intercultural Understanding in an Indonesian Islamic College Sample: An Epistemological Belief Approach. Religions. 2020; 11(8):411. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11080411

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhufron, M. Nur, Rini Risnawita Suminta, and Jamaludin Hadi Kusuma. 2020. "Knowledge and Learning of Interreligious and Intercultural Understanding in an Indonesian Islamic College Sample: An Epistemological Belief Approach" Religions 11, no. 8: 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11080411

APA StyleGhufron, M. N., Suminta, R. R., & Kusuma, J. H. (2020). Knowledge and Learning of Interreligious and Intercultural Understanding in an Indonesian Islamic College Sample: An Epistemological Belief Approach. Religions, 11(8), 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11080411