Abstract

Much research considers group differences in religious belonging, behaving, and/or believing by gender, race, ethnicity, class, or sexuality. This study, however, considers all these factors at once, providing the first comprehensive snapshot of religious belonging, behaving, and believing across and within these axes of inequality in the United States. Leveraging unique data with an exceptionally large sample, I explore religion across 40 unique configurations of intersecting identities (e.g., one is non-Latina Black heterosexual college-educated women). Across all measures considered, Black women are at the top—however, depending on the measure, there are different subsets of Black women at the top. And whereas most sexual minorities are among the least religious Americans, Black sexual minorities—and especially those with a college degree—exhibit high levels of religious belonging, behaving, and believing. In fact, Black sexual minority women with a college degree meditate more frequently than any other group considered. Overall, whereas we see clear divides in how religious people are by factors like gender, education, and sexual orientation among most racial groups, race appears to overpower other factors for Black Americans who are consistently religious regardless of their other characteristics. By presenting levels of religious belonging, behaving, and believing across configurations of gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality in the contemporary United States, this study provides a more complex and complete picture of American religion and spirituality.

Keywords:

inequality; religion; gender; race; ethnicity; class; education; sexuality; sexual orientation Group differences in religious belonging, behaving, and/or believing by gender, race, ethnicity, class, or sexuality are among the most researched topics in the social scientific study of religion. The intersection of economic inequality and religion was a topic of particular interest for Marx and other early theorists, and the interrelationships between social inequalities (i.e., gender, race, ethnicity, and sexuality) and religion have become just as if not more frequently examined across the social sciences (Davis 1971; Edgell 2017; Schnabel 2020).

Large bodies of research explore these group differences individually. Gender differences in religiosity, for example, have been debated for decades (Edgell et al. 2017; Miller and Hoffmann 1995; Roth and Kroll 2007; Schnabel 2015, 2017, 2018a; Schnabel et al. 2016; de Vaus and McAllister 1987). Substantial bodies of research also explore group differences in religion by race (Chatters et al. 1996; Ellison and Sherkat 1995; Hunt and Hunt 2001; Roof and McKinney 1987), class (especially as measured by education) (Flere and Klanjšek 2009; McFarland et al. 2011; Schwadel 2011; Stark and Bainbridge 1985), and sexuality (Schnabel 2020; Sherkat 2002, 2016). Some recent theory and research, however, has begun applying intersectionality theory to religion, suggesting that we need to look not just across but also within social statuses (Avishai et al. 2015; Schnabel et al. 2018; Stewart et al. 2017; Wilde 2018; Wilde and Glassman 2016).

Qualitative research has more frequently applied an intersectional lens on the complexity of religion and inequality (Burke and McDowell 2020; Ellis 2018; Khurshid 2015; Legerski and Harker 2018; Prickett 2015; Read and Eagle 2014; Wilde 2019; Wilde and Danielsen 2015; Zainal 2018), but quantitative research has also started applying an intersectional lens on religion. Although some quantitative research has begun considering, for example, religion at the intersection of gender and race (Glass and Jacobs 2005; Read and Eagle 2011), race and class (Wilde et al. 2018), or gender and sexuality (Sherkat 2002, 2016), much less quantitative research considers the intersection of more than two characteristics at the same time (but see Schnabel 2016b; Sherkat 2017).

Research on group differences in religion demonstrates that structurally disadvantaged groups are often more religious than their more privileged counterparts—except for sexual minorities who have been frequently condemned, marginalized, and excluded by organized religion (Perry and Schnabel 2017; Powell et al. 2017; Schnabel 2016a; Sherkat 2002; Wedow et al. 2017). Various theories have been set forth for this phenomenon of religion disproportionately appealing to the disenfranchised, mostly centered on material and/or social deprivation and hardship and the spiritual, social, and psychological compensation religion provides (Du Bois 1903; Davis 1971; Glock 1964; Hoffmann and Bartkowski 2008; Schnabel 2020; Stark and Bainbridge 1987). Although we generally know that women, Black Americans, and those with less education are typically more religious—and sexual minorities are less religious—than their more privileged counterparts, we know less about whether and how these factors intersect with one another in shaping religious belonging, behaving, and believing.

It is possible that those who are disadvantaged on more statuses will be more religious, but—in light of intersectionality theory and the complexity of inequality—we cannot just expect simple additive patterns that would allow us to just add up the number of a person’s disadvantaged statuses to predict their level of religiosity or expected beliefs. In other words, we cannot just assume that Black–white gaps in religion will be exactly the same for women and men, or that the relationship between education and religion will be the same for sexual minorities and heterosexuals. Therefore, to get a better picture of the complexity of American religion on standard measures of religious belonging, behaving, and believing, we need to explore variation within status characteristics and examine how these characteristics intersect with one another.

Leveraging unique data with an exceptionally large sample, this study provides the first comprehensive snapshot of religious belonging, behaving, and believing across configurations of what are arguably the “core” axes of inequality: gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality (Schnabel 2018b). Exploring religion across 40 unique configurations of intersecting identities (e.g., one is non-Latina Black heterosexual college-educated women), I show (1) how structural disadvantage often but not always predicts greater religious belonging, behaving, and believing; (2) when and why certain statuses predict different levels and types of religion and spirituality; (3) how status characteristics intersect with one another to yield patterns that vary not only across but also within groups; and (4) how the patterns vary across different types of religion measures. Illustrating this variation, whereas Black women tend to be at the highest levels across measures, different subsets of Black women are at the top of different aspects of religion. For example, Black heterosexual women with less than a college degree report the most religious salience and affiliation, as well as the highest levels of belief in God and the inspiration of scripture. Black heterosexual women with a college degree, however, are the most involved in organized religion, and Black sexual minority women with a college degree meditate more frequently than any other group considered.

By presenting levels of religious belonging, behaving, and believing across social status configurations in the contemporary United States, this study provides a more complex and complete picture of American religion and spirituality at the intersection of gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality. In response to the helpful comments of a reviewer who said they “fundamentally disagree” with using empirical quantitative survey methods to measure religious belonging, behaving, and believing, I would like to acknowledge that: (1) this is a quantitative research note that uses survey data, (2) empirical research cannot perfectly measure the world, and (3) surveys cannot capture all the aspects, particularities, and complexities of people’s lives. I would also like to highlight that Christianity is the predominant religion in the United States and that standard survey measures of religion are often better at measuring monotheistic and congregation-focused religiosity than other forms of religion.

Despite limitations, this study will be the first to use nationally representative data to describe religious belonging, behaving, and believing across configurations of the “core” axes of inequality. I find that religiosity varies not only between groups but also within groups in ways that point to the complexity of inequality and religion in the United States.

1. Data, Measures, and Methods

1.1. Data

This study uses data from the 2014 U.S. Religious Landscape Study (RLS). The RLS data—with a very large sample size (over thirty-five-thousand respondents) and the needed social status characteristics and religion measures—provide a unique opportunity to examine standard measures of religion across various configurations of social status characteristics. These data come from phone interviews commissioned by the Pew Research Center and provide a large population-based sample of the American public. The survey was conducted from 4 June to 20 September 2014 in English and Spanish (3.8% of all interviewers were conducted in Spanish). Data collection was divided among three research firms: Abt SRBI, Princeton Survey Research Associates International (PSRAI), and Social Science Research Solutions (SSRS). Abt SRBI was the lead research firm, coordinating sampling and data collection. The national survey employed a dual-frame (cellphone and landline) random-digit dialing (RDD) approach to yield a nationally representative sample, with approximately 60% of the interviews conducted on cellphones and 40% on landlines. Overall, the response rate (AAPOR3) was 10.2% for the cellphone sample and 11.1% for the landline sample.

The full sample included 35,071 respondents, and this study focuses on the 33,479 cases with complete information on all the social status characteristics (gender, race and ethnicity, education, and sexual orientation). The sample sizes for analyses of individual measures of religious belonging, behaving, and believing vary by the availability of the relevant outcome measure.

1.2. Measures

1.2.1. Social Status Characteristics

This study explores religion across the following social status characteristics: gender (women and men), race and ethnicity (non-Latinx white, non-Latinx Black, non-Latinx Asian, non-Latinx other race and multiracial, and Latinx), class (less than a BA and BA or more education), and sexual orientation (heterosexual and LGB). I recognize that there are other ways to conceptualize and measure these social status characteristics, and I use the measures available in the dataset. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the social status characteristics individually and in combination with one another. Please note the relatively small size of some combinations of status characteristics.

Table 1.

Frequency and percentage of status characteristics.

Class can be measured in various ways. The data include both an income measure and an education measure. I opted to use the education measure for theoretical and empirical reasons. Theoretically, a college degree provides a relatively clear social class divide, distinguishing the working from the middle and upper classes. Empirically, income had exponentially more missing data than education, and income was fielded in categories that make it more difficult to clearly separate the working class from middle and upper classes. Due to the relatively small size of the sexual minority groups, I combine lesbian/gay and bisexual respondents into a single LGB sexual minority category.

1.2.2. Religious Belonging, Behaving, and Believing

This study examines eight key measures of religious belonging, behaving, and believing (see Table 2). First is a measure of religious salience, which asked respondents whether they consider religion not at all important = 0, not too important = 1, somewhat important = 2, or very important = 3 in their lives. Next are measures of religious affiliation (any affiliation = 1) and membership in a local congregation (membership = 1).

Table 2.

Metrics and descriptive statistics for religion measures.

Following the binary measures of religious belonging are ordered measures of religious and spiritual practice, measuring how frequently respondents attend religious services aside from weddings and funerals (never = 0, seldom = 1, a few times a year = 2, once or twice a month = 3, once a week = 4, and more than once a week = 5), pray outside of religious services (never = 0, seldom = 1, a few times a month = 2, once a week = 3, a few times a week = 4, once a day = 5, and several times a day = 6), and meditate (never = 0, seldom = 1, several times a year = 2, once or twice a month = 3, and at least once a week = 4).

The last two items are belief questions about God (“Do you believe in God or a universal spirit?” Yes = 1) and scriptures ((Bible/Torah/Koran/Holy Scripture inserted based on respondents’ religious affiliation) is the word of God = 1 vs. is a book written by men and is not the word of God = 0).

1.2.3. Analytic Strategy

This study will first report results from regression models including all the social status characteristics predicting each of the eight religion measures. I use logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes and OLS for ordered outcomes (additional analyses with ordinal logistic regression yielded substantively equivalent results). I will then present proportions (for dichotomous outcomes) and means (for ordered outcomes) for each of the religion items across all configurations of the social status characteristics.

2. Results

Much research on group differences in religion focuses on one group difference at a time. This study focuses on gender, race, ethnicity, class (as measured by education), and sexual orientation differences alongside and in interaction with one another. Before examining religion across the range of possible configurations of status characteristics, let’s first look at main effects for group differences. Table 3 presents group differences in religious belonging, behaving, and believing in models that include each of the characteristics (but do not interact them with one another). We will consider each measure individually, but before we do I will highlight a couple of key patterns. Across all measures, women score higher than men, and non-Latinx Black Americans higher than non-Latinx white Americans. Sexual minorities report lower levels of religious belonging, behaving, and believing than heterosexuals across measures except for the one that is not necessarily tied to organized religion (and is perhaps more spiritual than religious): meditation.

Table 3.

Status characteristics and religious belonging, behaving, and believing.

Having noted some of the broad overarching patterns across outcomes, let’s consider them one at a time. First looking at religious salience, a general measure of religiousness, we see that most disadvantaged groups are more religious than their more privileged counterparts. However, sexual minorities report less religious salience than heterosexuals, and Asian Americans less religious salience than non-Latinx whites. These patterns are as might be expected: sexual minorities report that something that frequently marginalizes them is not particularly important in their lives, and Asian Americans, who are less frequently tied to the dominant religious institution (i.e., Christianity) than other racial groups, also report religion being less important in their lives.

Shifting to two binary measures of religious belonging—affiliation and congregational membership—we see patterns that in some ways parallel those for salience but with some differences. Whereas people in the other/multiracial and Latinx categories reported more religious salience, they do not differ significantly from whites on the likelihood of identifying with a religion and are significantly less likely to be members of a local congregation. And while people with less than a bachelor’s degree are more likely to identify with a religion, it is those with a bachelor’s degree who are more likely to actually be members of a local congregation. This pattern of different styles of religion by education will show up again: those with more education—who are more civically engaged generally—are more actively engaged in congregational life at the same time that those with less education score higher on most other religion measures.

Turning now to our measures of religious practice, we see patterns consistent with what we have seen so far. Women and Black Americans continue to consistently score higher than their counterparts on these measures. Women and Black Americans are joined by Latinx Americans in this pattern of consistently more frequent religious and spiritual practice. The patterns for other racial groups are more varied, however. Asian Americans continue to score lower on religion measures, except that they do not meditate any less frequently than whites. People in the other/multiracial category do not attend services any more frequently than whites but do pray and meditate more frequently. Those with more education attend services and meditate more frequently than those with less education. Those with less education, however, pray more frequently. Whereas sexual minorities are less religious than heterosexuals on most measures, they do not meditate any less frequently than heterosexuals.

Finally, we come to two belief measures: belief in God and in scriptural inspiration. Here we see some of the strongest patterns by education and sexual orientation: those with less education and heterosexuals hold substantially more traditional views on these beliefs than those with a college degree and sexual minorities. Women, Black Americans, and Latinx Americans are also more traditional in their beliefs than their more structurally-advantaged counterparts. Asian Americans are less likely to believe in God or scriptural inspiration than whites. Those in the other/multiracial category are more likely to believe in God, but their views on scriptural inspiration do not significantly differ from those of whites.

Overall, disadvantaged groups besides sexual minorities and Asian Americans do tend to score higher on these religion measures, but there’s variation for specific aspects of religion. For example, whereas those with less education report more religious salience, are more likely to affiliate with a religion, pray more frequently, and hold more traditional beliefs, those with a college degree are more actively engaged in religious congregations and also meditate more frequently. And whereas Latinx Americans are more religious than non-Latinx whites on most measures, they are no more likely to be affiliated with a religion and are less likely to be members of a local congregation.

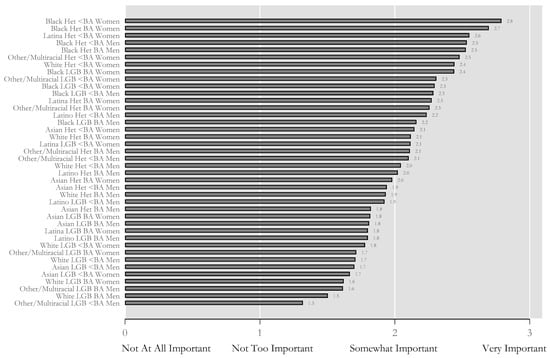

Having seen the main effects for the social status characteristics across measures of religious belonging, behaving, and believing, we now turn to how these characteristics intersect with one another to create different status configurations with potentially varying implications for religion. Figure 1 presents religious salience across the 40 possible configurations of the status characteristics. Here, we see a pattern that will repeat again and again: Black women are at the top in terms of religious belonging, behaving, and believing. Black heterosexual women without a BA report the highest level of religious salience, followed by Black heterosexual women with a BA.

Figure 1.

Religious salience across configurations of status characteristics, Religious Landscape Study (RLS) (N = 33,259).

Looking from the top to the bottom of Figure 1, we see a general pattern where most of the groups at the top of the chart are heterosexuals whereas most of the groups at the bottom are sexual minorities. We get to the eighth group from the top before we see the first sexual minority group (Black sexual minority women with a bachelor’s degree) and the 14th group from the bottom before we see the first heterosexual group (Asian heterosexual men with a bachelor’s degree). In fact, it is almost entirely Black sexual minorities who are the sexual minority groups in the upper half of the figure. Therefore, while for most groups being a sexual minority is linked to particularly low levels of religious salience, that is not so much the case for Black Americans (among whom sexual minorities continue to report relatively high levels of religious salience). Likewise, it is almost all women toward the very top of the figure, but there are also groups of Black men toward the top as well. It appears, therefore, that being Black can to some extent overcome what would typically be characteristics (being a sexual minority and being a man) that would be linked to being on the lower half of the figure. Likewise, being a woman is typically linked to being in the upper half of the figure, but being a sexual minority—who is not Black—will overcome the tendency for women to be on the upper end of religious salience. Among whites, it appears other factors become particularly important dividing lines for how religious people say they are: white heterosexual women without a college degree are quite religious but white sexual minority men with a college degree are quite secular.

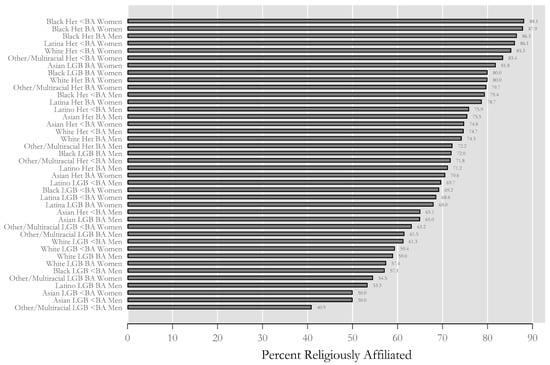

Turning now to religious affiliation in Figure 2, we primarily see groups of women at the top. However, Black heterosexual men with a bachelor’s degree and, to a lesser extent, Black heterosexual men without a bachelor’s degree are also among the groups most likely to have a religious affiliation. Overall, groups of gay and bisexual men and, to a lesser extent, lesbian and bisexual women are those least likely to report a religious affiliation. Similar to the patterns for religious salience, it is not until we get to the 14th group from the bottom of the figure before we see our first heterosexual group (again, it is Asian heterosexual men). Overall, we see that being Black seems to overshadow other identities in terms of religiousness, while we see more variation on other characteristics among other racial and ethnic groups, including Asians, Latinxs, whites, and those in the multi/other race category.

Figure 2.

Religious affiliation across configurations of status characteristics, RLS (N = 33,288).

Shifting from affiliation to congregational membership, we see similar overall patterns, but while those without a college degree trended toward the top on the affiliation figure, it is those with a college degree that trend upward here. Illustratively, it is Black heterosexual women with a college degree who are most likely to be members of a local congregation as shown in Figure 3. Perhaps surprisingly, Black sexual minority women with a BA are more likely than every group except for heterosexual Black women to be members of a local congregation. Black sexual minority men with a BA are also toward the top of congregational membership—whereas being a sexual minority predicts a very low likelihood of membership for most Americans, sexual minority Black Americans with a college degree still exhibit very high levels of membership. In fact, Black sexual minority men with a BA are just as likely to be members as are Black heterosexual men without a BA. For no other racial or ethnic group are sexual minorities nearly so likely to be members of a congregation.

Figure 3.

Membership in local congregations across configurations of status characteristics, RLS (N = 33,397).

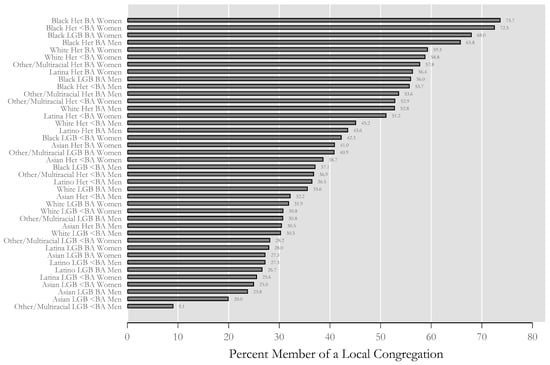

Figure 4 presents the patterns for our first measure of religious behavior: religious service attendance. We see that, once again, Black women are at the top: Black heterosexual women with and without a bachelor’s degree attend more frequently than any other group. Of the eight groups who attend most frequently, all are Black and Latina. Two of these groups are sexual minorities: both women and men Black sexual minorities with college degrees. Whereas Black sexual minorities with college degrees were among some of the most frequently attending groups, all 16 of the groups who attend least frequently are sexual minorities. There is a clearly intersectional phenomenon occurring at the intersection of sexual orientation, race, and education so that while most sexual minorities rarely attend services, sexual minority Black Americans with college degrees, both women and men, still frequently attend religious services. This pattern does not extend to Black sexual minorities with less education, however: Black sexual minority men with a BA are among those who attend most frequently, but Black sexual minority men without a BA are among those who attend least frequently.

Figure 4.

Religious service attendance frequency across configurations of status characteristics, RLS (N = 33,334).

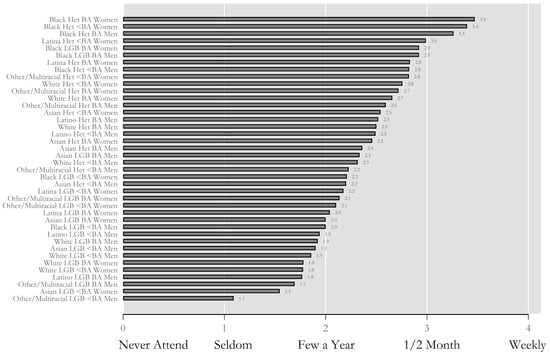

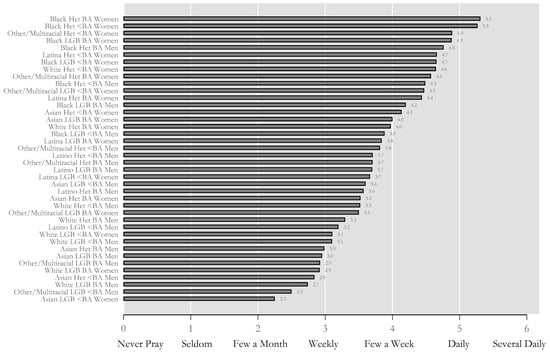

Figure 5 presents patterns for prayer frequency, and Black women are again at the top. However, prayer frequency differs from attendance frequency in a few ways. First, the patterns for sexual orientation differ, with groups of sexual minorities and heterosexuals more interspersed in terms of prayer frequency. In fact, Black sexual minority women with a college degree pray more frequently than everyone but Black heterosexual women and other/multiracial women with less than a college degree. Therefore, it appears that while sexual minorities—except for Black sexual minorities with a college degree—are less likely to be involved in organized religion, they still pray fairly frequently and are not consistently non-religious and non-spiritual. Gender is a key divide for prayer frequency, with women making up 10 of the 12 groups who pray most frequently but only two of the 12 groups who pray least frequently. Whereas groups with a BA were more toward the top on attendance frequency, that is not the case for prayer frequency.

Figure 5.

Prayer frequency across configurations of status characteristics, RLS (N = 33,183).

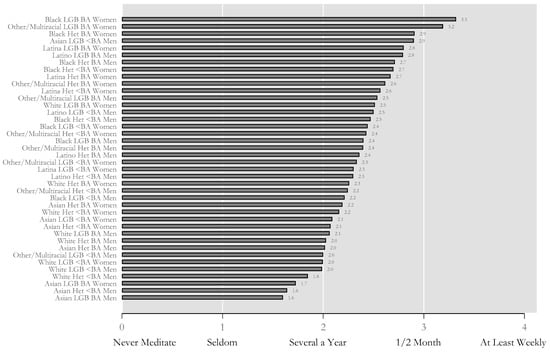

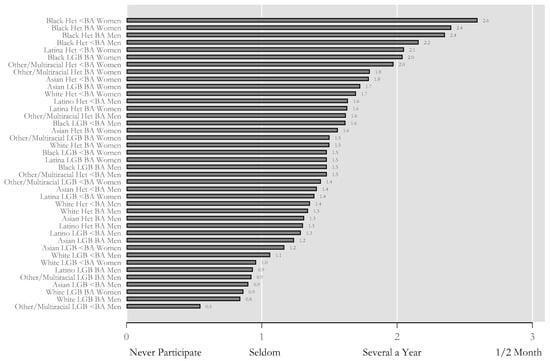

For meditation, a measure more of lived religion and spirituality distinct from organized religion in the U.S., there are several sexual minority groups at the top: notably, it is again Black women, here, sexual minority Black women with a BA, at the top. In fact, Figure 6 shows that five of the six groups who meditate most frequently are sexual minorities. This pattern for meditation indicates that sexual minorities, like other structurally-disadvantaged groups, are also looking for meaning and psychological wellbeing in their daily lives. However, organized religion, by further marginalizing rather than welcoming sexual minorities, has failed to provide community and meaning-making opportunities to a group who might otherwise find them particularly meaningful. Similar to the patterns for prayer, meditation frequency is clearly gendered, with many (but not all) groups on the higher end of meditation frequency being women (and especially women with college degrees).

Figure 6.

Meditation frequency across configurations of status characteristics, RLS (N = 32,978).

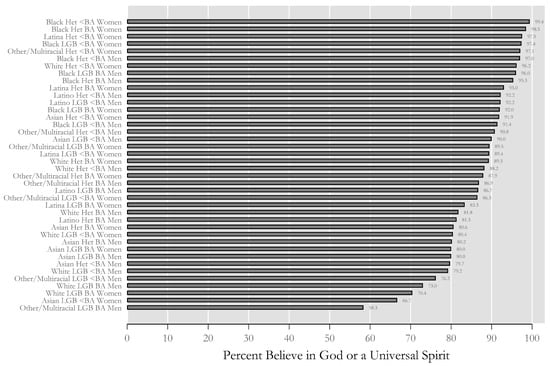

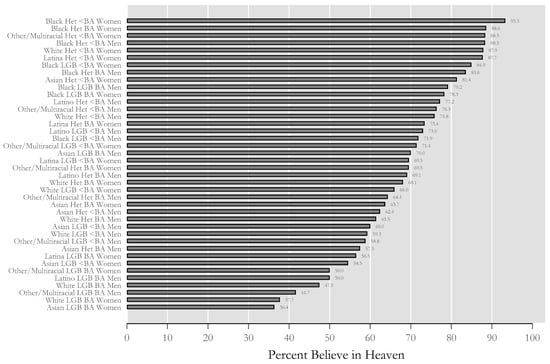

Next, we turn to two belief measures: belief in God and scriptural inspiration. Figure 7 shows that Black women without and with a BA are the two groups most likely to believe in God, with almost universal belief in God. And Black sexual minority women without a college degree are more likely to believe in God than everyone but heterosexual Black women and heterosexual Latina women without a college degree. Whereas many groups demonstrate almost universal belief in God (or a universal spirit), this particularly high level of belief is largely restricted to racial and ethnic minorities. Among whites, women without a college degree are the only group with over 90% belief in God. Notably, most of the groups least likely to believe in God are sexual minorities. Of the ten groups least likely to believe in God, the only two heterosexual groups are Asian men with and without a college degree. As Table 1 illustrated, there is an overall trend of those with a bachelor’s degree being less likely to believe in God, and we do see that seven of the ten groups most likely to believe in God have less than a college degree; nevertheless, Black Americans exhibit very high levels of belief in God even if they have a college degree—and even if they are sexual minorities.

Figure 7.

Belief in God or universal spirit across configurations of status characteristics, RLS (N = 32,681).

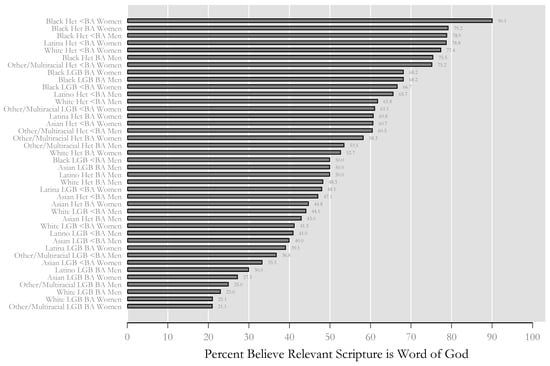

Finally, we see in Figure 8 that Black women are again at the top of belief in scriptural inspiration, with nine in ten Black heterosexual women without a college degree, and four in five of those with a college degree, believing scripture is the word of God. Black Americans make up seven of the 10 groups who are most likely to believe scripture is the word of God. Notably, all 12 of the groups least likely to believe scripture is the word of God are sexual minorities, who have frequently been condemned via particular literalist interpretations of scripture. Moreover, all six of the groups least likely to believe in literalism are sexual minorities with college degrees. Likewise, most of the groups who are most likely to believe scripture is the word of God have less than a college education, except for Black Americans, including Black sexual minorities, who are likely to believe scripture is the word of God even if they have a college degree.

Figure 8.

Belief in scripture as word of God across configurations of status characteristics, RLS (N = 31,089).

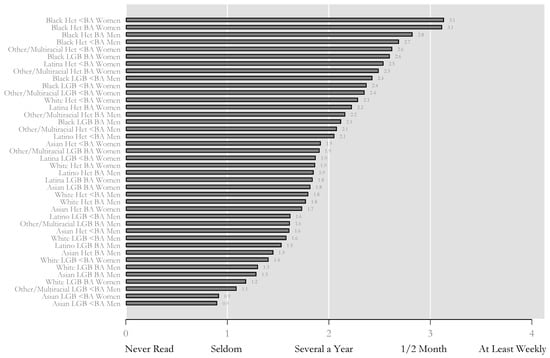

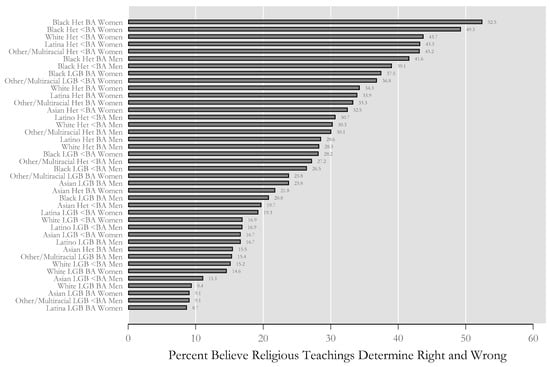

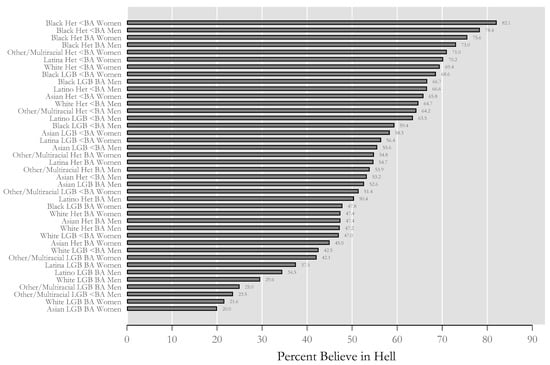

Analyses of five additional religion measures (see Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4 and Figure A5 in Appendix A) confirm the patterns for the eight primary measures: Black women are at the top of participating in religious small groups, scripture reading frequency, believing religious teachings are more important than everything else in determining right and wrong, believing in heaven, and believing in hell. Consistent with the patterns presented earlier, while most sexual minorities tend to be on the lower end of these additional religion measures, Black sexual minorities tend to be toward the top.

3. Discussion

Much research considers group differences in religious belonging, behaving, and/or believing by gender, race, ethnicity, class, or sexuality. This study considered all these factors in tandem, providing a novel overview of inequality and religion in the United States across 40 unique configurations of social status characteristics. Across all measures of religious belonging, behaving, and believing considered, Black women are at the top—but, depending on the measure, it is different subsets of Black women at the top. Although structurally-disadvantaged groups often score higher on religious belonging, behaving, and believing, sexual minorities typically score lower, especially on measures related to organized religion and traditional beliefs. They do not meditate less frequently than heterosexuals, however, and there seems to be something unique to the intersection of race, class, and sexuality that makes it so that sexual minority Black Americans, and especially those with a college degree, are among the most religious Americans. In fact, it is sexual minority Black women who meditate most frequently in the United States. In short, race appears to overpower other factors among Black Americans, who tend to be highly religious regardless of their other characteristics. Other racial and ethnic groups, however, tend to vary more within themselves depending on other characteristics like gender, class, and sexuality.

The goal of this study was to describe levels of religiosity across standard measures of belonging, behaving, and believing across social status characteristics, considering whether these characteristics intersect to produce multiplicative rather than just additive patterns in religiosity. For example, do gender differences in religiosity vary across racial and ethnic groups? The results demonstrated intersecting rather than just additive group differences in religiosity, with perhaps the clearest example being sexual orientation differences in religiosity. Whereas white sexual minorities are much less religious than white heterosexuals, Black sexual minorities are still comparatively religious. This pattern may be surprising given that Black Americans tend to be especially likely to oppose same-sex relationships.1

This study’s purpose was to describe broad patterns across many groups and measures, but I will provide some theoretically informed speculation for the pattern of comparatively high religiosity among Black sexual minorities. One possibility is the semi-involuntary nature of the church in the Black community and the potential that sexual minorities would risk further marginalization from their communities for being both sexual minorities and not involved in the church (Ellison and Sherkat 1995). A complementary possibility, one that is more about seeking positives than avoiding negatives, is that there are certain aspects of the Black Church that could be particularly appealing to sexual minorities. For example, sexual minorities tend to be especially common and prominent in gospel music and Black church choirs (Heilbut 2012; Jones 2016). In fact, Black churches have been criticized for “hypocrisy in opposing same-sex marriage while relying on gay people for much of the sacred music of the Black church” (Freedman 2012, p. 14). Additionally, Black churches tend to have especially strong, connected, and pro-social communities, and when sexual minorities are religious, they tend to emphasize interconnectedness and pro-social community (Halkitis et al. 2009). Moreover, sexual minorities appear to be drawn to and benefit from psychological compensation from religion and spirituality, and Black churches may be particularly effective at promoting social and psychological benefits for those facing structural disadvantages and hardships in their daily lives (Jeffries et al. 2008; Pitt 2010; Schnabel 2020). Finally, whereas Black churches often remain theologically conservative on issues like same-sex relationships, they still tend to promote the progressive politics and Democratic voting favored by sexual minorities (Schnabel 2018b).

By presenting levels of religious belonging, behaving, and believing across configurations of gender, race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality in the contemporary United States, this study provided a more complex and complete picture of American religion.2 Yes, disadvantaged groups besides sexual minorities tend to be more religious and more likely to hold traditional religious beliefs, but the complexity of inequality and religion in the United States produces variation across configurations of social status characteristics and measures of religious belonging, behaving, and believing. Specifically, how religious people are depends on complex interactions of all their status characteristics so that, for example, sexual orientation differences in religiosity are comparatively smaller among Black Americans than among other groups. The results also demonstrated variation across different aspects of religion, with groups who are typically less religious (e.g., sexual minorities and those with more education) demonstrating comparatively higher levels of some aspects of religion and spirituality (e.g., meditation).

This study highlights the importance of intersectional approaches in the study of religion, demonstrating the need to look within, rather than just across, social status characteristics to understand American religion and spirituality.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Religious small group participation (prayer groups, scripture study groups, etc.), RLS (N = 33,298).

Figure A2.

Scripture reading frequency, RLS (N = 33,258).

Figure A3.

Religious teachings and beliefs more important than philosophy and reason, practical experience and common sense, and scientific information in determining right and wrong, RLS (N = 32,578).

Figure A4.

Belief in Heaven, RLS (N = 30,930).

Figure A5.

Belief in Hell, RLS (N = 30,672).

References

- Adamczyk, Amy, Katharine Boyd, and Brittany Hayes. 2016. Place Matters: Contextualizing the Roles of Religion and Race for Understanding Americans’ Attitudes about Homosexuality. Social Science Research 57: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avishai, Orit, Afshan Jafar, and Rachel Rinaldo. 2015. A Gender Lens on Religion. Gender & Society 29: 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Kelsy, and Amy McDowell. 2020. White Women Who Lead: God, Girlfriends, and Diversity Projects in a National Evangelical Ministry. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatters, Linda M., Robert Joseph Taylor, and Karen D. Lincoln. 1996. African American Religious Participation: A Multi-Sample Comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 35: 403–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Angela. 1971. Lectures on Liberation. Los Angeles: Committee to Free Angela Davis. [Google Scholar]

- de Vaus, David, and Ian McAllister. 1987. Gender Differences in Religion. American Sociological Review 52: 472–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 1903. The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago: A.C. McClurg&Co. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell, Penny. 2017. An Agenda for Research on American Religion in Light of the 2016 Election. Sociology of Religion 78: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgell, Penny, Jacqui Frost, and Evan Stewart. 2017. From Existential to Social Understandings of Risk. Social Currents 4: 556–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rachel. 2018. ‘It’s Not Equality’: How Race, Class, and Gender Construct the Normative Religious Self among Female Prisoners. Social Inclusion 6: 181–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher, and Darren Sherkat. 1995. The ‘Semi-Involuntary Institution’ Revisited. Social Forces 73: 1415–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flere, Sergej, and Rudi Klanjšek. 2009. Social Status and Religiosity in Christian Europe. European Societies 11: 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, Samuel. 2012. Using Gospel Music’s Secrets to Confront Black Homophobia. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/02/us/gospel-music-book-challenges-black-homophobia.html (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Glass, Jennifer, and Jerry Jacobs. 2005. Childhood Religious Conservatism and Adult Attainment among Black and White Women. Social Forces 84: 555–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, Charles. 1964. The Role of Deprivation in the Origin and Evolution of Religious Groups. In Religion and Social Conflict. Edited by Robert Lee and Martin Marty. New York: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis, Perry, Jacqueline Mattis, Joel Sahadath, Dana Massie, Lina Ladyzhenskaya, Kimberly Pitrelli, Meredith Bonacci, and Sheri Ann Cowie. 2009. The Meanings and Manifestations of Religion and Spirituality among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adults. Journal of Adult Development 16: 250–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbut, Anthony. 2012. The Fan Who Knew Too Much: Aretha Franklin, the Rise of the Soap Opera, Children of the Gospel Church, and Other Meditations. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, John, and John Bartkowski. 2008. Gender, Religious Tradition, and Biblical Literalism. Social Forces 86: 1245–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Larry, and Matthew Hunt. 2001. Race, Region, and Religious Involvement: A Comparative Study of Whites and African Americans. Social Forces 80: 605–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, William, Brian Dodge, and Theo Sandfort. 2008. Religion and Spirituality among Bisexual Black Men in the USA. Culture, Health and Sexuality 10: 463–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, Alisha. 2016. Are All the Choir Directors Gay? Black Men’s Sexuality and Identity in Gospel Performance. In Issues in African American Music. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Khurshid, Ayesha. 2015. Islamic Traditions of Modernity: Gender, Class, and Islam in a Transnational Women’s Education Project. Gender & Society 29: 98–121. [Google Scholar]

- Legerski, Elizabeth, and Anita Harker. 2018. The Intersection of Gender, Sexuality, and Religion in Mormon Mixed-Sexuality Marriages. Sex Roles 78: 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, Michael J., Bradley R. E. Wright, and David L. Weakliem. 2011. Educational Attainment and Religiosity: Exploring Variations by Religious Tradition. Sociology of Religion 72: 166–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Alan, and John Hoffmann. 1995. Risk and Religion: An Explanation of Gender Differences in Religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Samuel, and Landon Schnabel. 2017. Seeing Is Believing: Religious Media Consumption and Public Opinion toward Same-Sex Relationships. Social Currents 4: 462–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, Richard. 2010. ‘Still Looking for My Jonathan’: Gay Black Men’s Management of Religious and Sexual Identity Conflicts. Journal of Homosexuality 57: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, Brian, Landon Schnabel, and Lauren Apgar. 2017. Denial of Service to Same-Sex and Interracial Couples: Evidence from a National Survey Experiment. Science Advances 3: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prickett, Pamela. 2015. Negotiating Gendered Religious Space: Particularities of Patriarchy in an African American Mosque. Gender & Society 29: 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Read, Jen’nan, and David Eagle. 2011. Intersecting Identities as a Source of Religious Incongruence. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 116–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, Jen’nan Ghazal, and David Eagle. 2014. Intersectionality and Identity: An Exploration of Arab American Women. In Religion and Inequality in America: Research and Theory on Religion’s Role in Stratification. Edited by L. Keister and D. Sherkat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Roof, Wade Clark, and William McKinney. 1987. American Mainline Religion: Its Changing Shape and Future. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Louise Marie, and Jeffrey Kroll. 2007. Risky Business: Assessing Risk Preference Explanations for Gender Differences in Religiosity. American Sociological Review 72: 205–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2015. How Religious Are American Women and Men? Gender Differences and Similarities. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54: 616–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2016a. Gender and Homosexuality Attitudes across Religious Groups from the 1970s to 2014: Similarity, Distinction, and Adaptation. Social Science Research 55: 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2016b. The Gender Pray Gap: Wage Labor and the Religiosity of High-Earning Women and Men. Gender & Society 30: 643–69. [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2017. Gendered Religiosity. Review of Religious Research 59: 547–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2018a. More Religious, Less Dogmatic: Toward a General Framework for Gender Differences in Religion. Social Science Research 75: 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2018b. Sexual Orientation and Social Attitudes. Socius 4: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2020. Opiate of the Masses? Inequality, Religion, and Political Ideology in the United States. Social Forces. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon, Matthew Facciani, Ariel Sincoff-Yedid, and Lori Fazzino. 2016. Gender and Atheism: Paradoxes, Contradictions, and an Agenda for Future Research. Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion 7: 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel, Landon, Conrad Hackett, and David Mcclendon. 2018. Where Men Appear More Religious than Women: Turning a Gender Lens on Religion in Israel. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwadel, Philip. 2011. The Effects of Education on Americans’ Religious Practices, Beliefs, and Affiliations. Review of Religious Research 53: 161–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren. 2002. Sexuality and Religious Commitment in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 313–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren. 2016. Sexuality and Religious Commitment Revisited. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 756–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren. 2017. Intersecting Identities and Support for Same-Sex Marriage in the United States. Social Currents 4: 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren, Kylan DeVries, and Stacia Creek. 2010. Race, Religion, and Opposition to Same-Sex Marriage. Social Science Quarterly 91: 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, and William Sims Bainbridge. 1985. The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival, and Cult Formation. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Rodney, and William Bainbridge. 1987. A Theory of Religion. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Evan, Jacqui Frost, and Penny Edgell. 2017. Intersectionality and Power. Secularism & Nonreligion 6: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Wedow, Robbee, Landon Schnabel, Lindsey Wedow, and Mary Ellen Konieczny. 2017. ‘I’m Gay and I’m Catholic’: Negotiating Two Complex Identities at a Catholic University. Sociology of Religion 78: 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa J. 2018. Complex Religion: Intersections of Religion and Inequality. Social Inclusion 6: 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa. 2019. Birth Control Battles. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilde, Melissa, and Sabrina Danielsen. 2015. Fewer and Better Children: Race, Class, Religion, and Birth Control Reform in America. American Journal of Sociology 119: 1710–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa, and Lindsay Glassman. 2016. How Complex Religion Can Improve Our Understanding of American Politics. Annual Review of Sociology 42: 407–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, Melissa J., Patricia Tevington, and Wensong Shen. 2018. Religious Inequality in America. Social Inclusion 6: 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, Humairah. 2018. Intersectional Identities: Influences of Religion, Race, and Gender on the Intimate Relationships of Single Singaporean Malay-Muslim Women. Marriage and Family Review 54: 351–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Religion helps explain why Black Americans have comparatively negative attitudes toward same-sex relationships: it is because they tend to be particularly religious (Schnabel 2018b; Sherkat et al. 2010) and live in particularly religious areas (Adamczyk et al. 2016). |

| 2 | At least insofar as American religion can be measured with surveys without substantial oversamples of religious minorities. Because most religious Americans are Christian, on average patterns presented for American religion are largely Christian patterns. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).