The Cao Đài Deathscape: Reimagining Death, Funerals, and Salvation in Contemporary Vietnam

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Imagining Death as the Funerals of “Three Bodies” before the End of the World

3. Cao Đài Funeral Service in Action

3.1. The Procession and Preparation of the Coffin

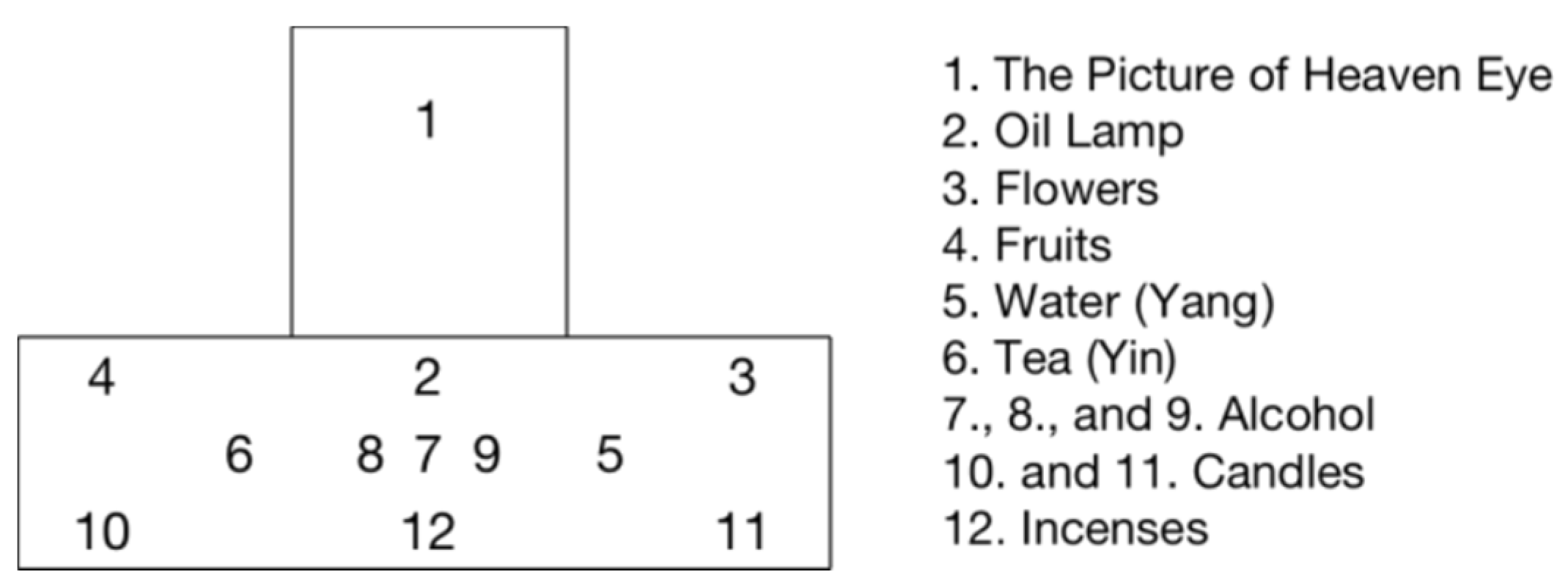

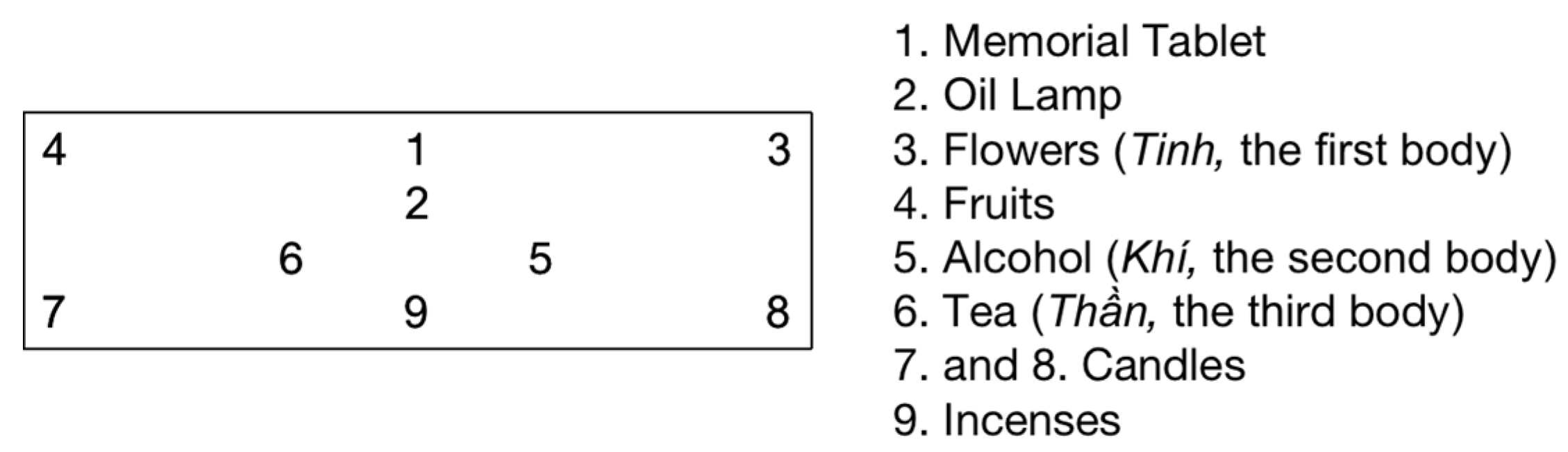

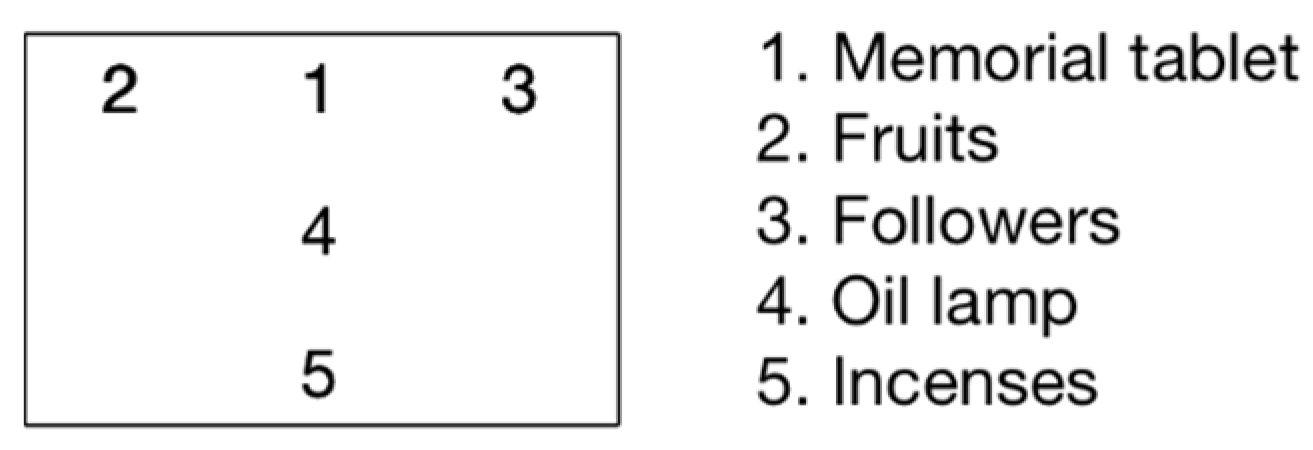

3.2. The Offerings

4. Talismanic Writing and a Bát Nhã Boat for a Universal Salvation

4.1. The Cao Đài “Sacraments”

4.2. A Bát Nhã Boat for Saving Cao Đài Dead Souls

4.3. A Cao Đài Mourning

5. Conclusions: Death as Return Passage to the Master

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ðức Nguyên (Nguyễn Văn Hồng). 2000. Cao Ðài Từ Điển, Quyển I, II, III. [Dictionary of Cao Đài, vols. 1–3]. Hochiminh City: Private Publication, Available online: www.ucs.soc.usyd.edu.au (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Dumoutier, Gustave. 1904. Le Rituel funéraire des Annamites: étude d’ethnographie religieuse. Hanoi: Impr. F.-H. Schneider. [Google Scholar]

- Gennep, Arnold Van. 1960. The Rites of Passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goossaert, Vincent, and David A. Palmer. 2011. The Religious Question in Modern China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hồ Sĩ Tân. 2009. Thọ Mai Gia Lễ 壽梅家禮 [Family Rituals of Thọ Mai]. Translated in Vietnamese by an Anonymous Translator. Hanoi: NXB Hanoi. [Google Scholar]

- Huỳnh Thế Nguyên, and Nguyễn Lệ Thủy. 2016. Cao Ðài Ðại Ðạo Tầm Nguyên Từ Ðiển [The Dictionary to the Sources of Cao Đài]. Available online: https://www.daotam.info/booksv/CDDDTN-TuDien(v2016)/CDDDTN-TuDien_KH.htm (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Jammes, Jérémy. 2014. Les Oracles du Cao Ðài. Étude d’un Mouvement Religieux Vietnamien et de ses Réseaux. Paris: Les Indes savantes. [Google Scholar]

- Jammes, Jérémy. 2016. Caodaism in Times of War: Spirits of Struggle and Struggle of Spirits. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 31: 247–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jammes, Jérémy. 2018. Đại Đạo Tam Kỳ Phổ Độ (Cao Đài). In Handbook of East Asian New Religious Movements. Edited by Lukas Pokorny and Franz Winter. Leiden: BRILL, pp. 565–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jammes, Jérémy, and David Palmer. 2018. Occulting the Dao: Daoist Inner Alchemy, French Spiritism and Vietnamese Colonial Modernity in Caodai Translingual Practice. Journal of Asian Studies 77: 405–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammes, Jérémy. Forthcoming. Theosophying the Vietnamese religious landscape: A Circulatory History of a Western Esoteric Movement in South Vietnam. In Theosophy across Boundaries. Edited by Hans Martin Krämer and Julian Strube. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Kiến Tâm. 1952. Chơn Lý Diệu Ngôn (Luật Tam Thể) [Quips of the Truth (the Three Laws)]. Available online: https://www.daotam.info/booksv/cldn-00.htm (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Lesserteur, Emile C. 1885. Rituel domestique des funérailles en Annam. Paris: Imprimerie Chaix. [Google Scholar]

- Maddrell, Avril, and James D. Sidaway, eds. 2010. Deathscapes: Spaces for Death, Dying, Mourning and Remembrance. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Naquin, Susan. 1976. Millenarian Rebellion in China: The Eight Trigrams Uprising of 1813. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyễn Văn Hồng. 2004. Bước Đầu Học Đạo [Start to Learn Cao Đài]. Holy See of Tây Ninh. Available online: https://www.caodaism.org/8004/bdhd.htm#bdhd-chuong04 (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Nguyễn Văn Hồng. 2014. Ba thể của con người theo quan niệm Cao Ðài giáo [The Three Bodies according to the Cao Ðài Conception]. Holy See of Tây Ninh. Available online: https://toathanhtayninh.wordpress.com/2014/11/06/ba-the-cua-con-nguoi-theo-quan-niem-cao-dai-giao-tiep-theo/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Overmyer, David L. 1976. Folk Buddhist Religion: Dissenting Sects in Late Traditional China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, Peter C. 1996. The Christ of Asia: An Essay on Jesus as the Eldest Son and Ancestor. Studia Missionalia 45: 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Phước Dương. 2017. Thực hành Phép xác - Cắt dây oan nghiệt [To bless the corpse-To cut the ropes of Karma]. Video. Posted on 14 July 2017. Available online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=dbQZnPntHU0 (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Pokorny, Lukas. Forthcoming. The Millenarian Myth Ethnocentrized: The Case of East Asian New Religious Movements. In Explanation and Interpretation: Theorizing About Religion and Myth. Edited by Nickolas P. Roubekas and Thomas Ryba. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 299–316.

- Quách Văn Hoà. n.d. Tang Lễ: Chức Việc và Đạo Hữu [The funeral: Clergy and believers]. Nghi Thức & Ý Nghĩa Tang Lễ Trong Đại Đạo Tam Kỳ Phổ Độ [Ritual and meaning of Funeral in the Great Way of the Third Period of Universal Salvation]. Available online: https://www.daotam.info/booksv/QuachVanHoa/NghiThucYNghiaTangLe/nghithuctangle-chucviecdaohuu.htm (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Shao Zhu Shuai. Forthcoming. Death as a Return: Cao Dai Myth and Ritual Paradigm in late-Socialist Vietnam. Ph.D. thesis, Cultural Anthropology, Université Paris Descartes, Centre d’Anthropologie Culturelle, Paris, France. (In preparation).

- Thánh Ngôn Hiệp Tuyển (TNHT) [Official Selection of Spirit Messages]. 1972. Tây Ninh: Holy See of Tây Ninh.

- Thượng Sáng Thanh. 1972. Cao Đài Hành pháp [Cao Đài sacraments]. Holy See of Tây Ninh, unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Trần Duy Nghĩa. 2000. Lời giải thích về Chèo Thuyền Bát Nhã của Ngài Khai Pháp Trần Duy Nghĩa, tại Khách Đình, ngày 13-10-Ất Hợi [Explanation of the Bát Nhã Boat by Khai Pháp Trần Duy Nghĩa, at Khách Đình, 8 November 1935]. In Cao Ðài Từ Điển [Dictionary of Cao Đài]. Edited by Ðức Nguyên. Hochiminh City: Private Publication, vol. 3, pp. 525–35. Available online: www.ucs.soc.usyd.edu.au (accessed on 15 January 2020). First published 1935.

- Trần Văn Rạng. 1972. Cao Thượng Phẩm - Luật Tam Thể - Nữ Đ.S. Hương Hiếu [Cao Thượng Phẩm - The Law of Three Bodies - Female Cardinal Hương Hiếu]. Available online: www.daotam.info/booksv/tvrctp.htm (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Williams, Paul, and Patrice Ladwig, eds. 2012. Buddhist Funeral Cultures of Southeast Asia and China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Multiplicity has always characterized Caodaism, especially because of its division into branches after a series of schisms, mostly due to a collection of localized clientelism (patron–client ties and nepotistic relationships), political interests, and strategies of power (Jammes 2014, pp. 143–47). Subsequently, Caodaism as a religion did not have a single impact on the process of decolonization but included people on many contrasted political sides and practices. Regarding the various factions during wartime situation, for instance, see Jammes (2016). |

| 2 | For the sake of clarity in the chronological reading of the Cao Đài funerals, comparative research hypotheses between pre-Cao Đài funerals (according to Buddhist and Confucian traditions, especially) and Cao Đài funerals are kept in footnotes. |

| 3 | For a broad description of the funeral ritual process, see Ðức Nguyên (2000, vol. 3, pp. 170–72), based on the document published by the Holy See of Tây Ninh in 1970: “Hạnh Đường Huấn luyện Chức việc Bàn Trị Sự nam nữ”. |

| 4 | This belief is intensified among the “esoteric” branches, who place an emphasis on personal, spiritual cultivation through Daoist inner alchemy and meditation, with the aim of refining the hồn (魂 hún) and phách (魄 pò) souls on the path to immortality (tiên 仙 xiān). The Chiếu Minh or Chiếu Minh Tam Thanh Vô Vi (照明三清無為 Zhàomíng sānqīng wúwéi; literally, Radiant Light of Noninterference of the Three Purities), is the leading “esoteric” branch of Caodaism, as the complement of the “exoteric missionazing” run by the Holy See of Tây Ninh (Jammes and Palmer 2018). Dying with the left eye open––which is mostly claimed by Chiếu Minh members––can be interpreted as a visual proof to consolidate the spiritual authority of the small, esoteric Chiếu Minh branch over the dominant Holy See of Tây Ninh. |

| 5 | The reaction of the body after death was also in Buddhism subject to many omens, indicating the quality of the transmigration of the soul of the deceased (“if the heat shall persist in the middle of the back, the soul will transmigrate in the body of a beggar”, for example, as noticed by Dumoutier (1904, p. 17), who gives several omens of this type). Similarly, “when the eyes remain open after death, it is a favorable sign: the soul of the deceased will transmigrate in human form, but this second [transmigration] will be crossed by countless misfortunes. If the eyes, first opened, then come to close, the bad omen will disappear, and one will be able to predict a second existence perfectly calm” (ibid). |

| 6 | Cao Đài comprises professional missionaries (giáo sĩ) and an ecclesiastical hierarchy of dignitaries: deacons (Lễ Sanh), priests (Giáo Hữu), bishops (Giáo Sư), archbishops (Phối Sư), cardinals (Đầu Sư), censor cardinals (Chưởng pháp), a pope (Giáo Tông), and subdignitaries (Ban Trị Sư). |

| 7 | We define “occultism” as an institutionalized movement that appeared in the nineteenth century in the West that reinterpreted and recast old religious and esoteric practices and doctrines (e.g., supernatural phenomena, traditional spirit-mediumship activities) through the filters of modern scientific methods and instruments (Jammes and Palmer 2018; Jammes forthcoming). |

| 8 | The “Law of Three Bodies” (Luật Tam Thể) was transmitted postmortem by Cao Quỳnh Cư (1888–1929), a pioneer of Caodaism, during spirit-writing séances run between 1950 and 1952 (Trần Văn Rạng 1972; Nguyễn Văn Hồng 2014). |

| 9 | Cao Đài doctrine states that the Golden Mother of Jade Pond, also known as the “Mother Goddess” (Diêu Trì Kim Mẫu or Phật Mẫu), created this second body and granted it to all the living creatures on Earth. |

| 10 | The word thần (神 shén) is a particularly polysemic, ambiguous term in Vietnamese. Although it most often refers to a specific local spirit, a genie, a god or a deity, it can also be used in its combined form of theo- (thần học, “theology”, literally the “study of deities”), or in reference to many things “mysterious”, “mystical”, “spiritual”, according to different contexts. Though not perfect, our translation of chơn thần by “true mind”—which can be traced from the combined word tinh thần (精神 jīngshén, “mind”, mentally, spiritual)––has the advantage of guaranteeing a clear distinction between thần and linh hồn (灵魂línghún), the “soul”. |

| 11 | “Popular Vietnamese religion believes that humans have three superior or rational souls (hồn) and inferior or sensitive souls, seven for men and nine for women (phách or vía) [Thất phách]. The latter, deriving from the Yin principle, enter the body at conception and do not survive death; the former, deriving from the Yang principle, enter the body at birth and survive death” (Phan 1996, p. 38). |

| 12 | According to Vietnamese Buddhism, the souls of the most virtuous ones, once arrived in hell, return to transmigration, but into a superior condition, or they can even be freed from transmigrations according to their degree of purity (Dumoutier 1904, pp. 155–58). |

| 13 | A spirit can be placed in five worlds of different levels, namely, the “way of humans” (nhơn đạo), “way of spirits” (thần đạo), “way of saints” (thánh đạo), “way of immortals” (tiên Đạo), and “way of Buddha” (phật đạo). Each spirit, saint, or immortal could be divided into three vertical levels: heaven, earth, and human (cửu phần thần tiên) (Kiến Tâm 1952). |

| 14 | Also named by Caodaists as Cõi Hư linh (the “Etheric world”), Cực Lạc Niết bàn (“the Nirvana”), Cõi thăng (“the Paradise”), in opposition to Cõi đọa (“the Hell”). In his comparative study, Lukas Pokorny (forthcoming) theorizes that Cao Đài espouses the “vision of a dual millennium”, before and after death, “namely that of ab ovo salvational perfection on the one hand, and post hoc salvational perfection (or salvational gradualism) on the other”. |

| 15 | Although few divergences may appear between the various Cao Đài branches, our article refers to the funeral orthopraxy we observed in the two main (demographically speaking) “Holy Sees” of Tây Ninh and Bến Tre. |

| 16 | This section is based on some training documents for Cao Đài apprentice priests or deacons (Lễ Sanh) printed by Tây Ninh Holy See in 2011, but also on participant-observation during our fieldworks. The authors have attended about 20 funerals (with 2 cases of “bad dead”, such as painful skin cancer and the murder of a woman by the use of acid thrown at her face). In contrast to Buddhist funerals, the case of “bad death” does not impact the Cao Đài funeral ritual process, which might know slight variations according to the identity of the dead (high dignitary, ordinary believer, or not-Caodaist). |

| 17 | It consists in rituals held to expel demons. |

| 18 | In the course of this simplification, many spirit-medium messages and their exegesis encourage Cao Đài devotees to eliminate what might be considered as superstitious (mê tín dị đoan) or that which would cause too much expense for the faithful. The New Canonical Codes ban meat offerings and the use of votive papers (nộm hình), a religious habit still strongly present in Vietnamese Buddhism and Mother Goddess worship, for instance. Simplification and normalization at the same time of rituals and talismans both call for homogeneity among Cao Đài branches. |

| 19 | Interview with Chi Hoa, at Huỳnh Đúc temple, District 3, Hochiminh City on 18 April 2018. |

| 20 | Interview with Trung Minh, at Cơ Quan Phổ Thông Giáo Lý on 20 April 2018. |

| 21 | In the branch of Ban Chính Đạo (the first Cao Đài community today, demographically speaking), the two prestigious temples are the Holy See of Bến Tre and the Bình Hòa temple in Bình Thạnh district (northern Hochiminh City). |

| 22 | In Vietnamese Buddhist funerals, the phướn traditionally carry a protective mantra (dhāraṇī) in Chinese characters in the center: “they are finished in the lower part by pendants of three colors, four in number for purely votive phướn, and only three in mortuary circumstances. The four pendants are in memory of the four Spirits who guard the world” (Dumoutier 1904, p. 44). In Caodaism, the words Đại Đạo Tam Kỳ Phổ Độ seem to play a similar demon-expelling power. |

| 23 | From the deacon’s rank upwards, the hierarchy of the men is divided into three branches, symbolically called “branch of Confucianism” (phái Ngọc, costume in red), “Buddhism” (phái Thái in yellow), and “Daoism” (phái Thượng in blue). |

| 24 | Although sharing a similar name with Buddhist ritual, the Cao Đài Praying for Redemption has its own characteristics. It especially not only aims to help the spirit of the dead to move gently into higher states of improvement, but the ritual also requires relatives, community members, and professional mourners to ask for a "Great Mercy, which could ensure an end of the cycle of rebirth”. Purposely following Confucian family ritual tradition, the Scripture of Worldly Way (Kinh Thể Đạo) is a collection of kinship-driven mourning prayers, to be recited, namely, by a son who worships his parents (con tế cha / mẹ), by younger siblings who worship elder brothers or sisters (anh em tế anh), by a wife who worships her husband, or by a husband who worships his wife (vợ tế chồng or chồng tế vợ). |

| 25 | The “great soul” (đại hồn, 大魂 dàhún) of the Jade Emperor residing on the High Tower (cao đài, 高台 gāotái) would be the essence, the vitality, and the guardian of this light. |

| 26 | According to Dumoutier (1904, p. 78), when the coffin is about to touch the ground, the tablet held by the eldest son must be completed by the most literate son of the family: “The last character of this inscription, which was written in advance, and which is the character chủ 主 [Zhǔ] (master), was intentionally left incomplete, since it lacks a kind of comma at the top; as such, [the character] 王 [Ch. wáng, Vn. vương], means “lord” or “king”. The literate parent, with a brush stroke, completes the character, and it is at this precise moment that the soul of the deceased comes to animate the tablet”. |

| 27 | Water, fire, wood, earth, and metal (Thủy, Hỏa, Mộc, Thổ, and Kim). |

| 28 | The Classic of Filial Piety (also known by its Chinese name as the Xiào jīng (孝经), by Zēng zǐ (曾子, 505-436 B.C.E). |

| 29 | Following the slow rhythm of the Đảo Ngũ Cung repertoire (Ðức Nguyên 2000, vol. 3, p. 33), they first squat with one leg, then raise the leg to the knee position. After that, they lay down the leg as if drawing a semi-circle. |

| 30 | In the context of the Amnesty (Ðại Ân Xá) or universal salute granted by Master Cao Đài, the Holy See of Tây Ninh organizes three times a year (the 16th day of three lunar months, after the full moon, e.g., in January, July, and October) a so-called “Requiem Ceremony” (Cầu siêu hội), aiming to pray for the salvation of all spirits (vong linh), whether they have a religion or not and whether they have economic means or not to offer decent funerals. |

| 31 | Công phu 功夫, Công quả 功果, and Công trình 功程. |

| 32 | In Caodaism, the practice of a sacrament is granted to dignitaries only, and especially to those who take the oath to keep secret about their esoteric knowledge (Phép Bí tích), who follow a total vegetarian diet, and who have a pure mind and unshakable faith in Master Cao Ðài and Mother Buddha. |

| 33 | On this ritual, our analysis is based on ethnographic surveys, interviews with Ðức Nguyên (Holy See of Tây Ninh) and some religious leaders (Holy See of Bến Tre, Cơ Quan Phổ Thông Giáo Lý) between 2000 and 2011, Cao Đài writings (Bishop Thượng Sáng Thanh 1972; Ðức Nguyên 2000, vol. 3, pp. 192–96), as well as a video posted on YouTube (Phước Dương 2017). |

| 34 | Dumoutier (1904, p. 16) describes the making of such a water called Buddha water Đại Bi (Dàbēi大悲, “Great Compassion”, adhimātra-kāruṇika), referring to a female Brahma and an avatar of Quan Âm in Vietnam. To obtain this water, the monk had to macerate five different perfumes (cinnamon, star anise, incense, eagle wood, sandalwood), and to invoke the Genie of the Big Dipper constellation. This holy water aims to wash away the impurities of souls and to prepare them to enjoy the happiness of the other world. |

| 35 | We can make the hypothesis that since this term means “population”, it might represent the worship of the descendants to the deceased. |

| 36 | It consists of pointing the two fingers of the right hand (index and ring fingers) towards the divine eye while the middle finger is folded at the base of the thumb. With a sudden gesture, the middle finger stands up and clicks the thumb above the cup. |

| 37 | The Thiên character is part of one of the five most important amulets for funeral rites, with the amulets of the sun, moon, stars, light, water, wood, metal, and air (Dumoutier 1904, p. 27). |

| 38 | Only dignitaries who are promoted to the rank of saint (Thánh), that is to say, priests to the archbishops (Giáo Hữu to Chánh Phối Sư), are authorized to practise this rite at the Holy See of Tây Ninh. Dignitaries of Genie rank (Thần vị), like deacons, can only exercise the rite of blessing the corpse and cutting the karmic thread. |

| 39 | At the end of the second day following death, after the prayer for redemption, a so-called drama of the Bát Nhã boat may occur for a deceased who held the rank of Deacon (lễ sanh) or higher. It can also be played for bringing fortune to a newly-built house (only for the members of Tây Ninh branch). |

| 40 | It is said in Buddhism “Bát nhã ba la mật” (般若 波羅蜜 Prajñāpāramitā, which means “Bát nhã is wisdom”. |

| 41 | |

| 42 | Cao Ðài has also borrowed from the Buddhist terminology the term, Tiếp Dẫn Đạo Nhơn (接引道人 Jiē yǐn dào rén, “The One who leads to the Way of Man”), which serves in Buddhism to name the Bát Nhã boatman; it designates now the hierarchical position of “instructor” in Cao Ðài (endorsed in the 1930s by Gabriel Gobron, a French spiritist). |

| 43 | At the Holy See of Tây Ninh, only 24 dignitaries had the privilege of such a building: the (interim) Pope Lê Văn Trung, the top-three leaders of spirit-medium activity (Phạm Hộ Pháp, Cao Thượng Phẩm, and Cao Thượng Sanh), the 12 spirit-mediums, the three male Cardinals (Đầu Sư), the two female Cardinals (Nữ Đầu Sư Hương Hiếu and Hương Lự), the three male Archbishops (Chưởng Pháp) (Ðức Nguyên 2000, vol. 3, pp. 134–35). However, in the esoteric Chiếu Minh branch, highly selective in initiation and in training, based on meditation and ascetism, all its dead are disposed in stupa at the cemetery (nghĩa địa) in downtown Cần Thơ. |

| 44 | That is 200 days after 9 weeks of having mourned every 9 days, following the expression “week of nine nine” (Tuần Cửu Cửu). The reference number of mourning days in Buddhism is “7”. |

| 45 | Meaning 300 days after Tiểu tường, or 581 days after death. According to Confucianism, Tiểu tường is the first anniversary of the death, happening one year later. The Đại tường is the second anniversary of death, exactly two years after death. |

| 46 | The 12 times of periodic mourning rituals (executed after burial) symbolically refer to but also depart from a traditional Vietnamese view of afterlife, as it was depicted in detail by Dumoutier (1904, pp. 155–203), of an underground prison run by the 10 Kings of Hell (Thập Điện Diêm Vương). The Cao Đài ritual performs the successive 12 passages from the corpse to Heaven (dominated by the Maitreya Bodhisattva); nine female immortals or fairies––subordinated to the Golden Mother of the Jasper Pool––assist the dead’s chơn hồn along their journey, and their mercy challenges the Confucian hierarchy lead by a King of Hell (Shao Zhu Shuai forthcoming). This journey is known in Cao Đài theology as the “Celestial mechanism of transformation” (Thiên cơ chuyển hóa). |

| 47 | According to the records in the Family Rites (Thọ Mai Gia lễ), the mourning period applicable to mourners wearing Trảm thôi is 29 months (Hồ Sĩ Tân 2009). In modern Vietnam, the Five-Garment system has been simplified. |

| 48 | The “beaked basket” instrument, used by Cao Đài spirit-mediums to communicate with deities and the dead for receiving their teachings, takes the form of the Big Dipper. |

| Sequences | Ritual Process | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency hospice care (or “extreme unction”) | Cầu hồn khi hấp hối | To pray for the soul at someone’s last gasp |

| The first day after death | Cầu hồn khi đã chết rồi | To pray for the soul when someone is died |

| Thượng sớ Tân cố | To inform respectfully Master Cao Đài of the death | |

| Tẫn liệm (Nhập mạch) | To put into the coffin (by funeral company) | |

| Tấm phủ quan/Đốt đèn trên và dưới quan tài. | To cover the coffin with fabric/Light lamps above and on both sides of the coffin (by funeral company) | |

| Thiết lập bàn vong, khay vong, linh vị | To set up offering table to handhold altar and spirit tablet | |

| Cáo Từ Tổ/Thành phục | To inform ancestors of the death/ To invite relatives to wear funeral costumes | |

| Cúng vong triêu tịch | To serve food to the dead spirit in the morning and at night | |

| The second day night after death | Tế điện: Chánh tế và Phụ tế | To sacrifice to the dead by family members and Cao Đài community members |

| Lễ cầu siêu | The ritual of praying for redemption | |

| Lễ chèo hầu tại Khách đình (phẩm Lễ Sanh) | The ritual of the Bát Nhã boat drama (when the dead is ranked as deacon (lễ sanh) or higher level) | |

| The third day (morning) after death | Hành pháp độ hồn: phép xác, đoạn căn, độ thăng | To write a talisman to transport the dead soul: body purification, secular root cutting, redemption acquiring |

| Lễ động quan/Khiển điện | The ritual of moving the coffin/Leaving the shrine | |

| Đưa linh cữu đến Nghĩa địa | To move the coffin to the cemetery (with the Bát Nhã boat) | |

| Điếu văn/Cảm tạ/Hạ huyệt | To make a memorial speech/To kneel down for gratitude/Burial | |

| Periodic rituals after burial (mourning rituals) | Tuần cửu Tiểu tường Đại tường | The ritual held every 9 days for 9 times The ritual held 281 days after death The ritual held 381 days after death |

| Realms | The First Body | The Second Body | The Third Body |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creation | Parents | Golden Mother of the Jasper Pool | Supreme Master Cao Đài |

| Life | Flesh (Phạm Thân 凡身) | True mind (Chơn Thần 真神) | True spirit (Chơn Linh 真靈) |

| Death | Corpse | True soul (Chơn Hồn 真魂) | True spirit (Chơn Linh 真靈) |

| Altar’s offerings | Flower | Fruit | Tea |

| Hierarchy/Architecture of temples | Cửu Trùng Đài (“palace of the nine degrees of the episcopal hierarchy”) | Hiệp Thiên Đài (“palace of the heavenly alliance”) | Bát Quái Ðài (“palace of the eight trigrams”) |

| Buddhist (Three Jewels) | Sangha (Tăng 僧) | Dharma (Pháp 法) | Buddha (Phật 佛) |

| Daoist (Inner alchemy) | Essence (Tinh 精) | Energy Flow (Khí 氣) | Spirit (Thần 神) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jammes, J.; Shuai, S.Z. The Cao Đài Deathscape: Reimagining Death, Funerals, and Salvation in Contemporary Vietnam. Religions 2020, 11, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060280

Jammes J, Shuai SZ. The Cao Đài Deathscape: Reimagining Death, Funerals, and Salvation in Contemporary Vietnam. Religions. 2020; 11(6):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060280

Chicago/Turabian StyleJammes, Jérémy, and Shao Zhu Shuai. 2020. "The Cao Đài Deathscape: Reimagining Death, Funerals, and Salvation in Contemporary Vietnam" Religions 11, no. 6: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060280

APA StyleJammes, J., & Shuai, S. Z. (2020). The Cao Đài Deathscape: Reimagining Death, Funerals, and Salvation in Contemporary Vietnam. Religions, 11(6), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060280