Abstract

Won Buddhism, established in 1916 by Founding Master Sot’aesan (少太山, 1891–1943), is one of the most active new religious movements in South Korea. When Korean society experienced a revolution in terms of values together with a swift transformation at the societal and national levels during the late 19th century, many novel religious movements emerged. Among these movements, Won Buddhism developed as one of Korea’s influential religions with an expanding role in society, both in performing the National funeral rites for deceased presidents and in the military religious affairs alongside Buddhism, Catholicism, and Protestantism. Unique interpretations of death underlie differences in rituals performed to pay homage to the dead. In this paper, I focus on the funerary rites of Won Buddhism. First, I will provide an introduction to Won Buddhism and subsequently give a brief overview of procedures involved in the death rituals of the religion. Finally, I will elaborate on the symbolism of the Won Buddhist funerary customs and discuss the deliverance service (K. ch’ŏndojae 薦度齋) as a practical demonstration of Won Buddhism’s teachings on birth and death.

1. Introduction: New Religious Movements on the Korean Peninsula

Over the course of contemporary Korea’s tumultuous period—with the crisis of the Chosŏn (K. 朝鮮 1392–1910) dynasty at the end of the 19th century and the imposition of Japanese colonial rule in the early 20th century—numerous alternative faiths emerged and faded. Some of these spiritual movements sought a third path through creeds based on neither established nor traditional beliefs. These “new Korean religions” materialized in a country undergoing rapid changes, from the end of conventional norms to Japanese occupation, and subsequently, liberation.

Korea’s modern narrative of itself is fraught with adversity. Threatened by European and other Asian powers in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Korea faced the national crisis of Japanese colonial rule (1910–1945). After liberation in 1945, Korea was placed under joint trusteeship by the United States and Soviet occupation forces, which led to the Korean War (1950–1953) and wreaked fratricidal havoc. Ever since the 1953 armistice, the Korean peninsula—divided into North and South Korea—has continually been under the threat of conflict. While having to keep up with rapidly changing global circumstances, the peninsula remains a highly volatile region.

When Korean society experienced a revolution in terms of values, together with a swift transformation at the societal and national levels during the late 19th century, many ‘novel’ or revivalist religious movements emerged. Kim et al. (1997) found more than 342 active groups and up to 700 in total including the groups in the past as well as present (Kim 2016). These new religious movements are Buddhism- (Pulgyogye 佛敎系) and Christianity-based. Further, many of them evolved from native traditions such as Tonghak- (Tonghakkye 東學系), Chŭngsan- (Chŭngsan’gye 甑山系), and Tan’gun-based (Tan’gun’gye 檀君系) religions (Pokorny 2018, pp. 235–36). The following is a list of a few major diverse faiths, including their variants:

- Eastern Learning (Tonghak: 東學), or Religion of the Heavenly Way (Ch’ŏndogyo: 天道敎), founded by Suun Ch’oe Cheu (水雲 崔濟愚, 1824–1864) in 1860 (Beirne 2009; Weems 1964);

- Righteous Change (Chŏngyŏk: 正易), launched by Ilpu Kim Hang (一夫 金恒, 1826–1898) (Yi 1990; Pak 1981);

- Chŭngsan’s Teachings (Chŭngsan’gyo: 甑山敎), founded by Chŭngsan Kang Ilsun (甑山 姜一淳, 1871–1909) in 1901 (Taesunjillihoe 1974; Yi 1977);

- Teachings of T’angun (Taejonggyo: 大倧敎), formed by Hongam Na Ch’ŏl (弘巖 羅喆, 1863–1916) in 1909 (Taejonggyo 2002; Sŏ 2001);

- Won Buddhism (K. Wonbulgyo 圓佛敎), founded by Sot’aesan Pak Chungbin (少太山 朴重彬, 1891–1943) in 1916 (DIAWBH 2016c; Park 1997).

What overarching principle of these rising Korean religious movements would shape the spirit of the times? At the heart of the emergence of new religions in Korea is the belief in the “Great Opening” (K. kaebyŏk 開闢). The “Great Opening” and the establishment of a more peaceful society in the future (Yun 2017; Park 2012) are ideas that flow through the vast majority of the new religious movements to this day (Pokorny 2018, p. 238).

The Kaebyŏk concept of new religions divides the past and the future world into Former Heaven (K. sŏnch’ŏn 先天) and Latter Heaven (K. huch’ŏn 後天), respectively, and primarily refers to the great opening era lasting for 50,000 years as the Latter Heaven in Korea. This era encapsulates the process of creation, change, extinction, and the regeneration of the universe. The thought of a “Great Opening of the Latter Heaven” (K. huch’ŏn kaebyŏk 後天開闢) is intimately connected to Buddhism’s future Buddha (K. Tangnaebul 當來佛; K. Miraebul 未來佛) or the faith in Maitreya as well as Mr. Chŏng’s (K. Chŏngdoryŏng 鄭道令) faith that appears in the popular apocalyptic narrative, the Record of Chŏng’s Mirror (K. Chŏnggamnok 鄭鑑錄) (Pokorny 2018, pp. 237–38; Jorgensen 2018). Buddhists believe that the Maitreya Buddha will appear after the death of the Shakyamuni Buddha in the Latter Heaven to save all living beings by opening the [Three] Assemblies (hoesang 會上) under the Dragon Flower Tree (Skt. nāgapuṣpa, yonghwa 龍華). It refers to the beginning of a period of millennial peace and prosperity in the new era. Additionally, the Dharma will be realized “here and now” in the civilized world of the Latter Heaven. These new faiths believe that the new heaven is the world that we are living in now.

Among these movements, Won Buddhism has developed into one of Korea’s influential religions with an increasingly important role in society, both in performing the national funeral rites when a president passes away and in the military religious affairs alongside Buddhism, Catholicism, and Protestantism. Unique interpretations of death underlie differences in death rituals among religions. In this paper, I scrutinize funerary rites, which are essentially a theatrical realization of one’s knowledge of death, specifically those of Won Buddhism. First, I will explain Won Buddhism and then briefly describe the procedures involved in the religion’s death rituals. Subsequently, I will elaborate on the symbolic value of the Won Buddhist funerary customs and discuss the deliverance service (K. ch’ŏndojae 薦度齋) as a practical demonstration of Won Buddhism’s teachings on birth and death.

2. What Kind of Religion Is Won Buddhism?

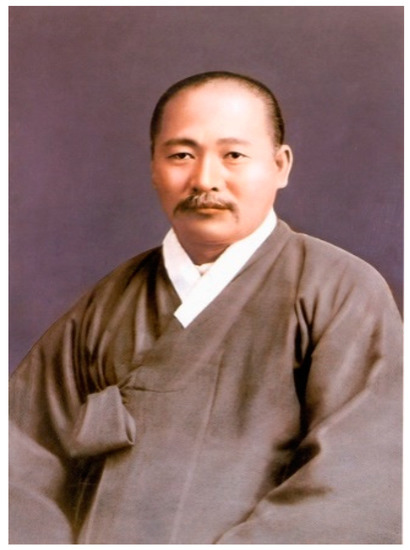

Won Buddhism, established in 1916 by the Founding Master Sot’aesan Pak Chungbin (少太山 朴重彬, 1891–1943, hereinafter referred to as Sot’aesan, see Figure 1), is one of the most dynamic new religious movements in Korea. After his successive religious activities, Master Sot’aesn publicly announced his religious organization as “Pulbŏp yon’guhoe” (K. 佛法硏究會 (The Research Society of Buddha Dharma)) in 1924 and renamed it Won Buddhism in 1947. The name “Won Buddhism” itself comes from the words 원/圓 wŏn (“circle”) and 불교/佛敎 bulgyo (“Buddhism”). “Won” refers to the Dharmakāya and, in metaphysical terms, is that realm where language, names, and signs are extinguished (The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, pp. 582–83). “Bulgyo” (Buddhism) means the teachings of awakening one’s mind to realize the essential truth of Won, the Dharmakāya.

Figure 1.

Founding Master Sot’aesan.

Sot’aesan was born as the son of a farmer in 1891 in a small farming village named Yŏngsan (lit. Spirit Mountain) in the Southwest Chŏlla province of Korea. The brief history of Sot’aesan’s life is introduced by Chung Bong-kil (Chung 1984, pp. 18–32) based on the History of Won Buddhism (K. 圓佛敎敎史) and Pulbŏp yon’guhoe chang’gŏnsa (K. 佛法硏究會創建史 [The History of the Research Society of Buddha Dharma = RSBH]) in the Hoebo (K. 會報), no. 37–49 (1937–1938), the monthly newsletter of the Research Society of Buddha Dharma.

Born at the end of the Chosŏn dynasty (1891), Sot’aesan is believed to have attained enlightenment at the age of 26 in 1916 after 19 years of seeking the universal truth. After his Great Enlightenment (K. taegak 大覺), Sot’aesan predicted the advent of the Latter Day’s Great Opening and declared the founding motto of Won Buddhism: “With this great opening of matter, let there be a great opening of spirit.” (K. Mulchir’i kaebyŏktoeni chŏngsin’ŭl kaebyŏkhaja 물질이 개벽되니 정신을 개벽하자).

Sot’aesan’s religious endeavors were directly shaped by religious, social, and political instability in Korea. His religious work is divided into three periods:

- The period of the early religious movements between 1916 and 1919: the “Embankment,” which is now called “Pangŏn kongsa” (K. 防堰公事), of the salty muddy land and the “Prayer at the Mountains,” which is now called as “Pŏbin kido” (K. 法認祈禱), meaning the Prayer of Authentication from the Dharma Realm.

- The period of retreat at the Pongnae Cloister (K. 蓬萊精舍) between 1920 and 1923.

- The period of the Pulbŏp Yon’guhoe (K. 佛法硏究會) or the Research Society of Buddha Dharma between 1924 and 1943.

Sot’aesan began his movement with a community-based farm project known as the “Embankment”. In 1918, he organized the community to portion off a large area of brackish tidal land near Korea’s southwestern coast and turned it into a farm to realize “a truly civilized world by advancing both study of the Way and the study of science” (The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, p. 109). After a year of work, the project was complete. This gave the new followers a sense of solidarity and would provide revenue for future initiatives.

Upon the Embankment, “The Prayer at the Mountains” was performed by nine chosen disciples for more than 200 days in 1919. The prayer was inspired by the March First Independence Movement of 1919 against Japanese colonialism. It was stated in the Chŏngsan chongsa pŏbŏ (K. 鼎山宗師法語, The Dharma Discourses of Cardinal Master Chŏngsan) as follows:

Because it [The Korean Independence movement in 1919] is the first outstanding sound (K. Sangdu sori) to pursue the ‘New Opening Era’ (K. Kaebyŏk 開闢), let’s hurry to pray after the Embankment (K. Pang’ŏn, 防堰 Reclaiming a beach into farm-land).(The Dharma Discourses of Cardinal Master Chŏngsan in the Scripture of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016b, p. 782).

However, the prayer speaks more directly in universal terms, vowing to save all sentient beings weakened by the power of the materialistic world from the sea of suffering. Sot’aesan ordered his followers to offer a sincere prayer, for soteriological purpose, to save all beings from the sea of sufferings. He asked his disciples “How can we, who have set our hearts on saving the world, think lightly of this situation?” (The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, pp. 94–95).

On prayer day, all of them gathered around 8 p.m. in the dharma room of the nine-room house, received instructions from Sot’aesan, and subsequently departed for their designated prayer sites in the mountains. Each member was given a watch so that they could synchronize the prayer time. The prayers comprised setting up incense, pure water, and erecting the flag with Eight Trigrams (K. p’alkwae 八卦; C. bagua) at respective locations. They began the ceremony with bowing and confessing, reading the prayer, and reciting a mantra (The History of Won-Buddism, DIAWBH 2006, p. 26). The Eight Trigrams are derived from the Book of Changes (C. I Ching; K. Yŏk’kyŏng 易經) (Park and Im 2019, pp. 148–49). Their use in the prayer symbolically demonstrates that the Won Buddhist Order seeks universal unity that corresponds to the heaven, earth, and the eight directions.

The nine disciples continued their prayer until October. The prayer is unique in style and represents the spirit of devotion with compassion. It aims to transform the nine disciples from egoistic beings into altruistic ones so that they could serve society (Chung 2003, pp. 45–46). The prayer to die for the greater good with no regret becomes the principle of spiritual devotion for the Won Buddhists, enabling them to save sentient beings from suffering.

Sot’aesan, after the successful accomplishments of the Embankment and the Prayer, moved to Pongnae Cloister located in Mt. Pongnae in October 1919 under increasing pressure from Japanese authorities. After a four-year retreat at the Pongnae mountain, Sot’aesan and his disciples held a general assembly on 29 April 1924 at the Pogwang temple and publicly established Pulbŏp Yon’guhoe (K. 佛法硏究會 The Research Society of the Buddha-Dharma) in Iksan city in 1924, which is now called Won Buddhism. Soon after the assembly, Sot’aesan and his disciples chose the present site for the headquarters and constructed two straw-thatched houses at Sinyong-dong, Iksan, north Chŏlla province in November 1924. Their clerical lives began with the construction of the headquarters of the Research Society of Buddha Dharma. Sot’aesan offered visions and hopes for a future society of popularized Buddhist practice, a truly civilized community where material and spiritual civilizations would harmoniously coexist. His religious organization was founded on his deep observation of the socio-political turmoil in Korea and the world. It presented a way to enlighten one’s mind and lead people from the sea of suffering to a “vast and limitless paradise.” Gradually, the number of temple branches increased steadily from 4 in 1928 to 23 in 1940 under the stern surveillance of the Japanese military government, which became sterner at the end of World War II. Despite the difficult social, political, and economic conditions, Sot’aesan was successful in his teaching, owing to an intensive training program in meditation, which was practiced by his followers faithfully.

After a lifetime of diligently imparting teachings to disciples, Sot’aesan passed away on June 1 in 1943. A formal farewell ceremony was held on the morning of June 6, and the final memorial service ceremony was held on July 19. On June 7, after Sot’aesan’s funeral rites were performed, the Head Circle Council (K. Suwidanhoe 首位團會) elected Master Chŏngsan Song Kyu (鼎山 宋奎, 1900–1962), who had been a central member of the Council since the Order’s early days, as the succeeding Head Dharma Master. Won Buddhism aims to become a new universal faith that guides humanity and all sentient beings to live a life of immeasurable blessings in the era of Great Opening of the Latter Heaven. Therefore, it is considered as a millenarian Buddhism that seeks the end of the present world as it exists to rebuild a vast and immeasurable paradise by expanding spiritual power and conquering material power through faith using a religion based on truth and training in morality based on facts (The Scripture of Won Buddhism, 16).

According to Cozin, Won Buddhism has developed as one of Korea’s major denominations (Cozin 1987, pp. 171–84) alongside Buddhism, Catholicism, and Protestantism, with a growing role in society. The members of Won Buddhism undertake various activities to build a peaceful global village, actively engaging in thoughtful practice, study and training to cultivate the mind’s authentic nature. Won Buddhism successfully attracted the attention of Koreans, making its presence felt through social activities, education, charity, welfare, medicine, culture, and industry. It has established several educational institutions, such as Wonkwang University, Wonkwang Health Science University, Wonkwang Digital University, Wonkwang Middle and High School, Wonkwang Girl’s Middle and High School, and Haeryong Middle and High School. Further, there are alternative, civic, and technical schools, and kindergartens in various districts. Won Buddhist ordained ministers are educated in three Universities: Wonkwang University and Yongsan Sŏnhak College in Korea, and Won Institute of Graduate Studies in the USA.

The doctrine of Won Buddhism is represented as two pillars: the Fourfold Beneficence or Grace (K. saŭn 四恩) in the domain of “other-power” and the practice of Threefold Study (K. samhak 三) in the domain of “self-power,” which are centered around the “Truth of Irwŏnsang,” as the ultimate truth of the universe. Sot’aesan expressed the Fourfold Beneficence based on his awakening to the truth that “nothing can exist without being interrelated with others.” This relationship was explained by the principle of retribution and response. Sot’aesan believed that all things in the universe co-exist together dependently so that one cannot exist without others. Based on this view, Sot’aesan deduced the moral ethics of Beneficence (K. ŭn 恩). He emphasized that all beings maintain their lives and preserve their bodies owing to the virtues of Heaven and Earth, Parents, Fellow Beings, and Law. The beneficence is found in the co-dependent relationship. His thought of beneficence is similar to the Buddhist thought of pratityasamutpada, or “co-dependent arising.” According to Sot’aesan, Heaven and Earth, Parents, Fellow Beings, and Law are the individualized Nirmanakayas of Dharmakāya Irwŏn. Any one of these could not exist without the others. All things in the universe benefit each other mutually. For this reason, Irwon as the Four Beneficence becomes the fundamental source to benefit all existence in the universe.

In addition, Sot’aesan proposed the practice of a Threefold Study by cultivating (1) the spirit (K. chŏngsin suyang 精神修養); (2) wisdom (K. sari yŏn’gu 事理硏究); and (3) mindful conduct (K. chagŏp ch’wisa 作業取捨). Chŏngsin suyang refers to nurturing a calm, clear mind, free from the tendencies to discriminate and form attachments enticed by sensory distractions. Sari yŏn’gu means studying and mastering human affairs and universal principles: “Human affairs” (K. sa 事) points to a sense of right and wrong, benefit and harm, among human beings. Meanwhile, “universal principles” (K. li 理) indicates the great and the small, the being and non-being, of heavenly creation. Chagŏp ch’wisa signifies choosing what is right, forsaking what is wrong in using our body and mind.

Although he emphasized that Buddhism is the unsurpassed, greatest path, Sot’aesan also underscored the importance of Confucianism and Taoism. In comparing the three major East Asian religious teachings with medical specialties, he mentioned each one as having distinct advantages (The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, pp. 125–26). Sot’aesan did not believe that any one part of the Three Teachings—Confucianism, Buddhism, or Taoism—would be able to save humanity. He highlighted the significance of embracing and practicing their doctrines, specifically (1) the Buddhist concept of chŏnmi kaeo (K. 轉迷開悟), turning from ignorance to enlightenment by cessation of defilement, which is grounded in the notions of being free from arising and ceasing, and the principle of retribution and response (cause and effect); (2) the Confucian social participation/practice of cultivating the self, keeping family ties in order, governing the country, and bringing peace to all under heaven (K. suje ch’ip’yŏng 修齊治平); and (3) the Taoist principle of nourishing one’s inner nature (K. yangsŏng 養性) through clear, calm non-action (K. ch’ŏngjŏng muwi 淸靜無爲). When these three traditions’ beliefs and practices are embraced, the ideologies of the world’s religions, all laws under heaven, and the aforementioned teachings could be amalgamated into one, culminating in a path that is considered as accessible and applicable in all circumstances. When I Ch’unp’ung, one of his disciples who practiced Confucianism, denounced Buddhist philosophy as “nothingness and annihilation” (K. hŏmu chŏngmyŏl 虛無寂滅) and “desolating their parents and the lord” (K. mubu mugun 無父無君), Sot’aesan countered that the social role of Buddhism should be emphasized (The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, p. 187).

The structure and symbolism of Won Buddhism’s rituals are based on Koreans’ understanding of the world’s future, reflected in emerging religious movements such as the Great Opening and divine spirits (K. sinmyŏng 神明) (Park 2002, pp. 89–114). The funerary rites (K. sangjang ŭirye 喪葬儀禮) for death and burial in Won Buddhism are those performed at the final stage of life. Such ceremonies are understood in religious studies as practical expressions determined by creed in a broad sense, while in a narrow sense, they imply pious human actions related to worship (Wach 1958, p. 25). For instance, the deliverance service is a practical demonstration of Won Buddhism’s teachings on birth and death. Despite the existence of several studies on such observances, controversy continues to surround the scope of the customs under study (Yun 1988, pp. 1–22; Van Gennep 1960). Nevertheless, in general, rituals not only strengthen and confirm a religious order’s principles but also cause their followers to identify with the order’s goals (Durkheim 1965, p. 420).

Funerary rites are, in essence, a theatrical realization of one’s perception of death. Examining those of Won Buddhism offers insight into the religion’s concept of existence and view of the afterlife. First, regarding Won Buddhism’s observances surrounding death, I will examine the issue of life and death from the perspective of Won Buddhist followers, their conceptions of the relationship between the body and the spirit, and their perceptions about the afterlife by investigating funerary ancestral customs as rites of passage.

3. Perceptions of Life and Death Reflected in the Funerary Rites of Won Buddhism

The procedures of funerary rites reflect the view of the afterlife. How does the relationship between the body and spirit change? Confucius lamented greatly when his favorite disciple, Yan Hui, died (Analects, Book XI Part 1). Conversely, Zhuangzi, an adherent of Taoism, sat with an inverted bowl on his knees, drummed upon it, and sang a song when his wife passed away. The funeral custom of Confucianism allows one to part with the deceased and express grief over one’s loss (Classic of Rites, Tangong I). Death, from Zhuangzi’s perspective, is a return to nature, and there is nothing to grieve for. Zhuangzi’s dance appears in itself as a dramatized ceremony to celebrate the return to nature.

Buddhism explains the body and spirit separately. Our physical bodies come into being as a gathering of the four elements: earth, water, fire, and air (Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra, T. no.374_12.0520c20–c29). Upon dying, these four elements dissolve into one another. However, our spirits repeat the cycle of rebirth according to our karma. The Āgama, a collection of early Buddhist scriptures, reveals a path to liberate oneself from the cycle of birth and death and never receive a physical body again (Dīrghāgama-sūtra, T. no. 1_01.0127a16–a26). Buddhists hold a deliverance service for 49 days for the deceased. Death appears as a farewell to life yet, simultaneously, the dead will re-emerge. Thus, rituals for both sending off and welcoming are performed concurrently.

In Won Buddhism, the body is no more than a house where the spirit stays for a moment; the body comes into being as a gathering of the four elements, which disperse after death. Sot’aesan said,

...The birth and death of a physical body are no different than changing an article of clothing. Even though our physical body, which is subject to such changes, might die one day, that unchanging, ever-bright, numinous consciousness lives......그 원리를 아는 사람은 이 육신이 한 번 나고 죽는 것은 옷 한 벌 갈아 입는 것에 조금도 다름이 없을 것이니, 변함에 따르는 육신은 이제 죽어진다 하여도 변함이 없는 소소(昭昭)한 영식(靈識)은 영원히 사라지지 아니하고, 또 다시 다른 육신을 받게 되므로...(The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, pp. 289–90).

The spirit is defined as eternal and immortal, repeating the cycle of life and death according to one’s karma. This is why liberation and deliverance are extremely important.

Regarding the meaning of life and death in Won Buddhism from a religious angle, Sot’aesan believed that the physical body’s birth and death comprises changes (not actual life and death). In 1916, he expressed this realization as follows:

All things are of a single body and nature; all dharmas are of a single root source. In this regard, the Way (K. To, 도 道) that is free from arising nor ceasing, and the principle of the retribution and response of cause and effect, being mutually grounded in each other, have formed a clear and rounded framework.만유가 한 체성이며 만법이 한 근원이로다. 이 가운데 생멸 없는 도(道)와 인과 보응되는 이치가 서로 바탕하여 한 두렷한 기틀을 지었도다.(The Scriptures of Won-Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, p. 87).

Sot’aesan described the tenet of universal existence as the “Way (K. To 道) that is free from arising nor ceasing” and “the principle of the retribution and response of cause and effect” as being mutually grounded in each other. The former implies the variability and invariability of life and death. The significance of ongoing change, neither arising nor ceasing, can be found in the following metaphor of his teachings:

A human being’s birth and death is like opening and closing your eyes, inhaling and exhaling (of the breath)[K. sumŭl tŭri swiŏtta naeswiŏtta 숨을 들이 쉬었다 내쉬었다], or falling asleep and waking up: there might be differences in how long these take but the principle is the same. Birth and death are originally nondual [K. saengsaga wŏllae turi aniyo 생사가 원래 둘이 아니요]; arising and ceasing originally do not exist. The enlightened [K. kkaech’in saram 깨친 사람] understand it as transformation [K. pyŏnhwa 변화/變化], but the unenlightened call it birth and death. People generally call the world we live in ‘this world’ and the world where the dead go the ‘other world’ and presume that ‘this world’ and the ‘other world’ are separate realms. However, it is only the body and its location that change; these are not separate worlds.(The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, p. 324).

Life and death are not separate but lie on a continuum of change. Further, Sot’aesan said that ordinary people only consider their lives in the present to be important, but perceptive people recognize that how to die is vital as well. He added the following:

This is simply because they know that only a person who dies well can have a good rebirth and a good life in the next [one], and only a person who has a good birth and life in the present can have a good death; [this is] also because they know the principle that life is the root of death and death is the root of life.(The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, p. 336).

Sot’aesan emphasized that one should practice the way of life and death and send on the spirit to its onward journey. Further, he affirmed that after the age of 40, one must start “packing one’s bags” for death, so as not to have to rush while dying, because rather than someone else sending on one’s spirit after death, it is more effective to send on one’s own spirit while still alive. Deliverance involves transforming evil people into good people and guiding them from a low to a high place: one can deliver oneself or be delivered, depending on the power of the Dharmakāya Buddha. During this process, referred to as purification, it is critical to repent and to dissolve attachments.

In “The Instruction on Repentance,” (K. ch’amhoemun 懺悔文) Sot’aesan said the following:

As a rule, ‘repentance’ [K. ch’amhoe 懺悔] is the first step in abandoning one’s old life and opening oneself to cultivating a new life, and the initial gateway for setting aside unwholesome paths and entering into wholesome paths.(The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, pp. 81–85).

Thus, for people who repent for their past mistakes and continue practicing wholesome paths daily, their past karma will gradually disappear, and no karma will be made anew; good paths will come closer with every passing day, while evil ones will recede of their own accord. The method of repentance comprises two types: (1) by action and (2) by principle. The former means sincerely repenting for past mistakes before the Three Jewels, and practicing, on a daily basis, all sorts of wholesome actions. The latter entails awakening to that realm in which the nature of transgressions is originally void, and one internally removes all defilements and idle thoughts. People who seek to free themselves of transgressions and evil forever must practice both in tandem. Externally, they must continue to practice all types of good karma while, internally, they must simultaneously remove their greed, hatred, and delusion.

Metaphorically speaking, it is similar to someone who tries to cool down the water boiling in a cauldron by pouring a lot of cold water on top, while also putting out the fire burning underneath. Unless the deceased have their transgressive karma purified, they cannot attain freedom of mind or go beyond their karma to free themselves from the cycle of life and death. Conversely, when karma is purified and unconstrained by either its transgression or merit, one can break through natural karma, entering Nirvana, and be sent on to deliverance. Master Chŏngsan defined the goal of deliverance to guide “the departed spirit to leave behind suffering and to attain happiness (K. igo tŭngnak 離苦得樂), to stop doing what is unwholesome and cultivate what is wholesome (K. chiak susŏn 止惡修善), and to turn from delusion to awakening (K. chŏnmi kaeo 轉迷開悟)” (The Dharma Discourses of Cardinal Master Chŏngsan, DIAWBH 2016b, pp. 848–49).

4. The Composition and Characteristics of the Funerary Rites of Won Buddhism

4.1. The Overall Composition of Won Buddhism: Religious Rituals

In 1926, Sot’aesan created new ceremonial conventions for believers to follow on four commemorative occasions (K. Saginyŏm yebŏp 四紀念禮法): (1) coming of age; (2) weddings; (3) funerals; and (4) ancestral rites (Park 2001, pp. 277–312). The ritual services and customs of Won Buddhism are prescribed in the Canon of Propriety (K. Yejŏn 禮典), in which common propriety (K. T’ongnyep’yŏn 通禮編) is first elucidated, followed by formalities concerning family rites (K. Karyep’yŏn 家禮編), as well as rites of the Order of Won Buddhism (K. Kyoryep’yŏn 敎禮編). Regarding general propriety, Master Chŏngsan, the second Head Dharma Master of Won Buddhism, views the fundamentals of propriety (K. ye 禮) as showing “respect” and “humility,” and “never comparing nor reckoning up.” He affirmed as follows:

According to the principle, however, the way for one to train oneself in propriety as a whole is to first seek the mind, and subsequently have the mind rest in the place devoid of distinction, and finally apply the ways of distinction in dealing with the matters of external nature.(Canon of Propriety, DIAWBH 2016a, p. 7).

Chŏngsan further said,

When a family forms, children are born. Following that, there are ceremonies for a person entering adulthood, weddings, 60th birthdays, funerals, deliverance services for the dead and ancestral rites. All such ceremonies come under the heading of ‘family rites’ [K. Karye 가례/家禮].(Canon of Propriety, DIAWBH 2016a, p. 50).

Chŏngsan organized rites of passage around the four commemorative occasions of Confucianism in rites of the Order of Won Buddhism. On pages 96 to 147 of the Canon of Propriety, he refers to various ceremonies related to the Order that are conducted in temples and which relate to faith, practice, and celebration. Celebratory rites include the following: regularly observed celebrations; Won Buddhist funerary rites (K. wŏnbulgyo-chang 圓佛敎葬) to honor an ordained devotee who contributed to Won Buddhism. A lay devotee is responsible for conducting the procession and burial as well as the deliverance service (K. chae 齋) and the Great Memorial Service (K. taechae 大齋), a joint memorial service offered on June 1 and December 1 every year honoring the memory of the Founding Master and all successive forefathers of the Order (See Figure 2).

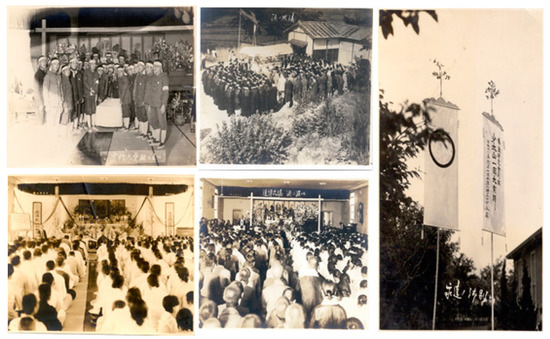

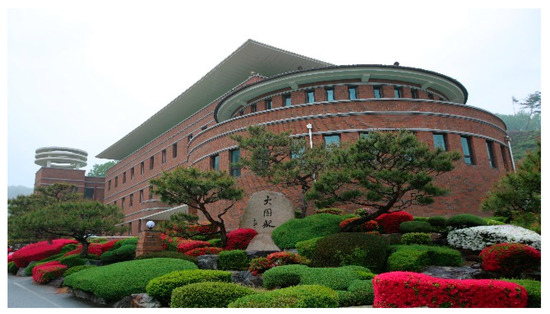

Figure 2.

Great Memorial Service on June 1 and December 1.

4.2. Funerary Rites—The Rite of Passage of “Death”

While marriages and birthday feasts are celebratory, funerary rituals are sorrowful occasions, sending off a deceased person. Funerary rites comprise the most solemn procedures, expressing the relationship between the living and the dead. The understanding of death varies depending on the particular faith, and the funerary rites clearly manifest their conception of the spirit. Won Buddhism distinctly simplifies the complicated Confucian funeral customs followed during the Chosŏn era, which scheduled the following successive rituals (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The first stage of Confucian funeral customs in Korea.

Subsequently, the following processes are conducted for the next three years (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The ritual service after the funeral service in Korean Confucianism.

According to the teachings of Won Buddhism, the role of funerary rites for the deceased would allow them to discard the present body and receive a new one. Therefore, the spirit must be properly sent on to deliverance. Thus, this ceremony has two vital purposes: “One is for the relatives and friends to share their feelings and affections, and perform formal farewell procedure. The second is for the deceased to achieve true nirvana and liberation” (Canon of Propriety, DIAWBH 2016a, p. 61). “Nirvana” has largely two meanings: either liberation (S. mokṣa; K. haet’al 解脫)—liberation from the cycle of birth and death, freedom from pain and suffering—or death. The deliverance service is conducted to pray for the spirit of the deceased and help them set aside unwholesome paths and enter a wholesome path in order to attain freedom of mind as well as to interfuse with the Dharmakāya.

Won Buddhism calls death “nirvana” and teaches practitioners to prepare for the Nirvana ceremony with sincerity following the prescribed procedures. When a person is close to dying, the person or their close associates should conduct the “Way to Nirvana.” (K. yŏlbanŭi do 涅槃道). It is advised that old customs—building a fire to stay up all night in the garden at the house of the bereaved, and the bereaved family members letting down their hair, slinging clothes over their shoulders/across their chests, or removing their shoes and socks—should be discarded. Moreover, those present at the Nirvana Ceremony are warned not to cry aloud before finishing it. Sot’aesan worried that family members’ attachment to the deceased would hinder them from being liberated from the cycle of birth and death (The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, p. 34) and encouraged families to help the deceased to move on.

Except in special cases, the funeral procession takes place on the third day after the passing of the deceased. The venue must either be the temple or the deceased’s place of residence. The ceremony is conducted in a particular order, using a photo or memorial tablet (Ceremonial Text 78) of the deceased: opening → wearing the articles of mourning and expressing the Statement of Purpose (Ceremonial Text 25) → addressing the deceased through a representative of the bereaved family (Ceremonial Texts 26–28) → mental affirmation (Ceremonial Text 24) and bowing together → reciting the Sacred Mantra once → Dharma instruction for sending on the spirit (Ceremonial Text 4–5) → Reciting scripture (The Irwŏnsang Vow) and the supplication text (Ceremonial Text 29) → closing. It is suggested that no bier carriers chant or wail while the bier is transported.

The burial ceremony begins after the casket arrives at the burial site. Cremation starts after ignition, while burial begins after ground leveling. Won Buddhism prefers cremation rather than burial. Further, several traditional Korean funerary customs such as placing the tablet, holding post-funeral rites, conducting ancestral rites on the first and fifteenth of every month, offering food to the deceased’s tablet in the morning and evening, celebrating the first and second anniversaries of the deceased’s passing, as well as other potentially cumbersome ceremonies are abolished by Won Buddhists.

After the funeral, the photo or memorial tablet (Ceremonial Text 78) of the deceased is enshrined in a clean room. During this time, the bereaved family and relatives pray for the deceased’s deliverance to Nirvana by frequently reciting scriptures and the Buddha’s name. The deliverance service (K. chae 齋) for the deceased should be repeatedly performed by the clergy of Won Buddhism at the temple or the place where the departed tablet is enshrined seven days after the passing of the deceased in participation of family. The deliverance service to send the spirit onward toward transition, is especially noteworthy in Won Buddhism; a 49-day service is held every seven days, starting from the First Deliverance (K. ch’ojae 初齋) to the Final Deliverance (K. chongjae 終齋). The traditional Buddhism in Korea also provides the deliverance service for 49 days, and it is more complicated. For example, Yŏngsanjae(K. 靈山齋), literally meaning “Rites of the Mount Grdhrakuta(Vulture Peak)”, is a Korean Buddhist ritual service performed since the Koryŏ Dynasty (918–1392) on the 49th day after a person’s death. It consists of reading the Buddhist Scriptures, reciting mantras, providing foods and fruits, music and dance, Dharma talk on the Buddha’s teaching in order to guide the dead to be liberated from any suffering in this world (samsara).

In Won Buddhism, the deceased’s spirit is believed to remain in a transitional state between passing and rebirth for approximately 49 days before it is reincarnated according to its karmic condition. During this time, the service is meant to guide the deceased in maintaining a pure, clear mind while dissolving any remaining attachments, in order to help deepen his/her affinity for rebirth with a salutary destiny (e.g., reaching Nirvana), through activities such as frequently reciting scriptures and offering supplications. Simultaneously, the donations offered during this service help to increase the deceased’s merit in the next world. In addition, these actions allow participants to observe the proprieties of commemoration and mourning during the period.

The first to sixth deliverance services are performed at the temple or the place where the departed one’s tablet is enshrined, seven days after the passing of the deceased. The service is repeated every seven days in the order demonstrated in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

The first to sixth deliverance services.

Table 4.

The Final Deliverance Service.

The Irwŏnsang Vow is written by the Master Sot’aesan for the people to make a vow to enlighten the truth of Irwŏnsang until they are endowed with “the great power of Irwŏnsang and unified with the noumenal nature of Irwŏnsang by following after [the truth of] Irwŏnsang Dharmakāya” in one’s daily life. (The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, pp. 22–23).

At the request of the bereaved host, a special Hundredth Day Deliverance Service may be conducted on the 100th day after the passing of the deceased to bid farewell to the spirit. It may be performed at other times at the special request of the bereaved host as a separate or joint service for all those who have previously passed away. A Special Deliverance Service, a memorial service to comfort the spirits of the dead, or a service to deliver the wandering spirits on land and sea may also be conducted either separately or jointly. The procedures and ceremonial texts of the Hundredth Day Deliverance Service are primarily based on those of the Final Deliverance Service. A Special Deliverance Service is primarily grounded in the texts for ancestral rites, but the recitation of scriptures is performed according to those of the Final Deliverance Service.

When Master Sot’aesan passed away on 1 June 1943, the 28th year of Won Buddhism, a solemn farewell ceremony was held in the great enlightenment hall at the headquarters of Won Buddhism in Iksan at 10 a.m. on June 6. Thousands of mourners had gathered from various parts of the country including monks belonging to the seven denominations of the Buddhist Alliance in Iksan. After the cremation ceremony at the Iksan Crematorium, his sacred remains after cremation were placed in a cemetery at the outskirts of Iksan (Kŭmgang-ni). In the midst of grieving guests, Kim Taehŭp (金泰洽 1899–1989), who was a Korean Buddhist monk, officiated the funeral rites from beginning to end. Subsequently, Ueno Shun’ei (上野舜潁 1869–1947), the celebrated Japanese Buddhist monk, who was revered by the high officials of the colonial Japanese government, attended the final memorial service ceremony on July 19 (The History of Won-Buddism, DIAWBH 2006, pp. 72–73). His sacred remains were preserved in the Pagoda of Master Sot’aesan to allow people to pay their respects to him (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Funerary Rites of Founding Master Sot’aesan.

Figure 4.

Memorial Pagoda of Founding Master Sot’aesan.

4.3. Ancestral Rites

Unlike the rituals for coming of age, weddings, and funerals, ancestral rites are not a necessary custom for death but a regular observance where the deceased’s descendants can make contact with the spirits of the deceased’s ancestors. This ceremony is performed in dedication to the memory of the deceased and has two purposes: (1) to declare one’s aspirations with a pure mind to the Buddha in order to extinguish the karmic obstacles of the previous lives of the deceased, strengthen affinity with the Buddhist path, increase the departed spirit’s future bliss, and contribute to social progress through monetary offerings (which are used for public service projects); (2) to commemorate the life achievements and virtues of the deceased, encouraging future generations to seek out their origins, and foster posterity through the requital of grace.

In Won Buddhism, ancestral rites manifest through the Memorial Service on the Deceased’s Day of Passing. The deceased’s descendants or students celebrate and pray for the eternal bliss of their spirit on days when parents, teachers, or elders passed away. Notably, while the service for parents, teachers, and elders is held on the day that the deceased passed away, for grandparents and other ancestors, an appropriate date is set, and the service is performed jointly once a year. The venue for the service is the temple or place of residence of the bereaved family. The service occurs in the order demonstrated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Memorial Service on the Deceased’s Day.

In the case of Sot’aesan, the Great Memorial Service is observed to forever honor his memory (and that of all successive forefathers of the Order) by regularly offering a joint memorial service on June 1, the day when he is said to have entered Nirvana. Further, each year at the Thanksgiving Great Memorial Service, observed on December 1, for Sot’aesan, all successive forefathers, parents, ancestors, and all living beings are collectively memorialized.

The funerary rites of Korea’s new faiths succeeded the tradition of ancestor commemoration in addition to the Confucian custom of paying tribute to one’s distant ancestors and respecting one’s roots (K. ch’uwŏn pobon 追遠報本). The complex procedures of Confucian and Buddhist funerary rituals were simplified or omitted.

Sot’aesan established the new system of rites and rituals in 1926 to simplify the overly complicated and troublesome ceremonial conventions of the time that placed many restrictions on people’s lives, caused needless waste of money, and therefore hindered social development (The History of Won-Buddism, DIAWBH 2006, pp. 48–50). For example, regarding funeral rites, a simple ribbon should be worn as a sign of mourning for 49 days at the longest, rather than following the traditional Confucian custom of geomancy. Another Confucian tradition, ancestor commemoration, expected to be served for each ancestor through three generations (i.e., parents, grandparents, and great grandparents), was deemed a waste of money and a hindrance to social activities. Further, the traditional Buddhist rituals were regarded as overly complicated. Hence, Sot’aesan simplified the ancestor commemoration to be served together on the same days on June 1 and December 1, twice in a year. In the ritual service of Won Buddhism, food is not served for the spirit. Rather, it is served to the participants. There is no sacrificial ritual to comfort the spirit. Meanwhile, mystical factors are criticized and bluntly discouraged. Then, the money saved should be used for public service work.

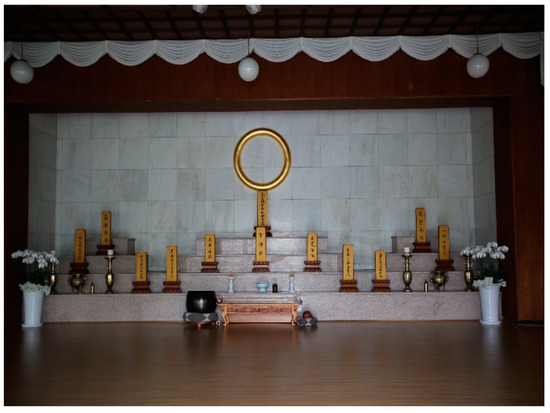

In Won Buddhism, the Hall of Eternal Commemoration (K. Yŏngmojŏn 永慕殿) was built in 1971 as the shrine to revere the Founding Master Sot’aesan and all the successive forefathers, and to cherish and repay the fundamental beneficence. With the exception of the Founding Master, the forefathers are collectively represented in memorial tablets. This is to simplify the previous practice of individual representation-based tablet arrangement which was found to be complicated. The memorial tablets in the hall are positioned according to certain specifications: the tablet commemorating the Founding Master and those memorializing all the successive forefathers, both lay and ordained, are placed at the main seats. The tablet dedicated to the Bestowers and that dedicated to the Parents and Ancestors are positioned at the left special seats, and the tablet for the Past Sages and that for the Sentient Beings are placed at the right special seats (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Hall of Eternal Commemoration #1.

Figure 6.

Hall of Eternal Commemoration #2.

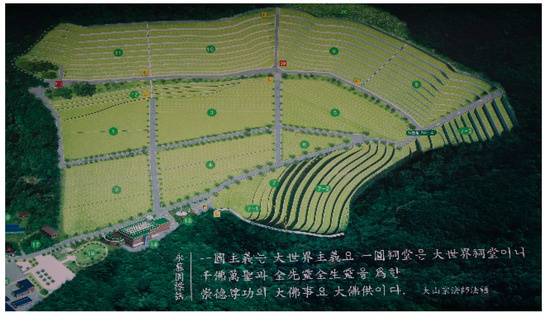

Furthermore, the Park of Eternal Commemoration (K. Yŏngmomyowŏn 永慕墓園), as it was recommended in the Canon of Propriety, was developed in the vicinity of Iksan city with a commanding landscape in honor of the all the clergy and lay believers of Won Buddhism. Moreover, the sacred stupa dedicated to the Founding Master, memorial pagodas for all the successive Head Dharma Masters, were built at the headquarters of Won Buddhism. Won Buddhist ceremonies provided rules of propriety appropriate to the times; they are simple but maintain essential beliefs, and are meant for the public to practice on various life occasions (see Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 7.

Park of Eternal Commemoration #1.

Figure 8.

Park of Eternal Commemoration #2.

Figure 9.

Park of Eternal Commemoration #3.

Figure 10.

Park of Eternal Commemoration #4.

5. Conclusions

Sot’aesan embraced and reformed the funerary rites of Confucianism and Buddhism in order to modernize them for daily life. The primary purpose of Sot’aesan’s reformation of Buddhism was to make Buddhist thought and systems accessible for the majority of people so that they could be applied in the contemporary secular world.

In Won Buddhism, the deliverance service is described in concrete detail for “someone who is close to the dying person [in terms of] how to send on the spirit [while that] person enters Nirvana, as well as how the person whose spirit is about to depart should prepare for death” (The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, p. 336). Birth and death are considered the cycle of life based on the principle of rebirth after death, just as the sun and moon change in the course of day turning to night (The Scriptures of Won Buddhism, DIAWBH 2016c, p. 343). As for the perception of life and death, the way of life and death is interdependent and lays the foundation. Furthermore, our bodies go through the changes of life and death, but our spirits are eternal, repeating the cycle of rebirth according to our own karma.

In Won Buddhism, practitioners recite the Irwŏnsang Vow and the “Instruction on Repentance” in the Scripture of Won Buddhism as a critical part of the purifying ritual of the funerary service. This process underscores the importance of repentance in breaking through natural karma and attaining complete deliverance from the cycle of birth and death. One can free oneself from the power of these corresponding life-giving and harmful karmic actions, and command at will merits and transgressions if one maintains pure, clear one-pointedness, and has awakened to what is original in one’s self-nature, thereby reaching freedom of mind. In theory, the venue for the service is the temple, which carries a spatial meaning as the sacred place for enshrining the Irwŏnsang (One-circle figure), the Dharmakāya Buddha. The “sacred hour” (K. sŏngsi 聖時) of the procedure (the 49-day service carried out every seven days) is a period of sacred purification through which the deceased receives a new body after death. The funeral service and the deliverance service for the dead is the procedure to recover the original nature of human beings, which is essentially pure, perfect, and complete: the same as the Buddha.

Funding

This research was supported by Wonkwang University in 2018.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Taishō shinshū dai zōkyō 大正新修大藏經 [Taishō edition of the Buddhist canon]. 100 vols. Tokyo: Taishō Issaikyō Kankōkai.Chang ahan jing 長阿含經 (Dīrghāgama-sūtra), 22 rolls. Translated by Buddhayaśas (Fotuoyeshe 佛陀耶舍) and Zhu Fonian 竺佛念 (ca. 365–385) in 413. T no. 1, vol. 1, pp. 1a–149c.Daban niepan jing 大般涅槃經 (Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra). 40 rolls. Translation by Dharmakṣema (Tanwuchen曇無讖, 385–433) between 414 and 421. T no. 374, vol. 20, pp. 365a–604a.Secondary Sources

- Beirne, Paul. 2009. Su-Un and His World of Symbol. Farnham: Ashgate Pub Co. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Bongkil. 1984. “What is Won Buddhism?” The Academy of Korean Studies. Korea Journal 24: 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Bongkil. 2003. The Scriptures of Won Buddhism. Honolulu: Univ. of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cozin, Mark. 1987. Won Buddhism: The Origin and Growth of a New Korean Religion. In Religion and Ritual in Korean Society. Edited by Laurel Kendall and Griffin Dix. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, Uni. of California, Berkeley Center for Korean Studies, pp. 171–84. [Google Scholar]

- Department of International Affairs of Won Buddhist Headquarters (DIAWBH). 2006. Wonulgyo Kyosa 원불교 교사 The History of Won-Buddism. Iksan: Wonkwang Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Department of International Affairs of Won Buddhist Headquarters (DIAWBH). 2016a. Canon of Propriety (Yejŏn). Iksan: Wonkwang Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Department of International Affairs of Won Buddhist Headquarters (DIAWBH). 2016b. The Dharma Discourses of Cardinal Master Chŏngsan in the Scriptures of Won Buddhism. Iksan: Wonkwang Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Department of International Affairs of Won Buddhist Headquarters (DIAWBH). 2016c. The Scriptures of Won Buddhism. Iksan: Wonkwang Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1965. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Translated by Joseph W. Swain. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, John. 2018. Korean Classics Library: Philosophy and Religion. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hong-ch’ŏl 김홍철. 2016. Han’guk sinjonggyo taesajŏn 한국신종교대사전 [Encyclopedia of Korean New Religions]. Seoul: Tosŏ ch’ulp’an mosi’nŭn saram’dŭl. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hong-ch’ŏl 김홍철, Yu Pyŏng-dŏk 유병덕, and Yang Ŭn-yong 양은용. 1997. Han’guksinjonggyo silt’aejosa pogosŏ 한국 신종교 실태조사 보고서 [A Survey Report on Korean New Religions]. Iksan: Research Center of Religions at Wonkwang University. [Google Scholar]

- Pak, Sanghwa 박상화. 1981. Chŏngyŏkkwa Han’guk 정역과 한국 [Righteous Change and Korea]. Seoul: Kwanghwasa Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Kwangsoo. 1997. The Won Buddhism (Wonbulgyo) of Sotaesan: A Twentieth-Century Religious Movement in Korea. San Francisco, London and Bethesda: International Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Kwangsoo 박광수. 2001. Tosan Yi Tongan-ŭi saengaewa sasang 도산 이동안의 생애와 사상 [Life and Thought of Tosan Yi Tongan]. 원불교 인물과 사상 2 [Life and Thought of Won Buddhist] 2: 277–312. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Kwangsoo 박광수. 2002. Han’guk Shinjong’gyo’e (Ch’ŏndogyo, Chŭngsan’gyo, Wŏnblgyo) natanan sinhwa sangjing ūiryeūch’egye’ŭi sanggwansŏng’e kwanhan pigyo yŏn’gu 한국 신종교 (천도교ㆍ증산교ㆍ원불교) 에 나타난 신화ㆍ상징ㆍ의례 체계의 상관성에 관한 비교연구 [A Comparative Study of the Structural Relationship among the Myths, the Symbols, and the Rituals in the Korean New Religions: Chŏndogyo, Chŭngsangyo, and Wonbulgyo (Won-Buddhism)]. 종교연구 [Studies in Religion] 26: 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Kwangsoo 박광수. 2012. Han’guk sinjong’gyo’ŭi sasang’gwa chonggyo munhwa 한국신종교의 사상과 종교문화 [Thought and Culture of Korean New Religions]. Seoul: Jipmundang. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Kwangsoo 박광수, and PyŏnghakIm Im 임병학. 2019. Wonbulgyo Pŏbin’gido-ūi Chech’ŏnūirye Sŏnggyŏk-kwa P’algwaegi-ūi Yŏk’ak-chŏk Ihae 원불교 ‘법인 (法認) 기도’의 제천 (祭天) 의례 성격과 ‘팔괘기(八卦旗)’ 의 역학적 이해 [A Study about the Characteristics of the ‘Prayers for the Dharma Authentication’ of Won-Buddhism as the Ritual Service to the Heaven and Comprehension of the ‘Flag of the Eight Trigrams’ from the Perspective of Book of Changes]. Sinjonggyo yŏn’gu 신종교연구 [Journal of the Korean Academy of New Religions] 41: 137–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny, Lukas. 2018. Korean New Religious Movements: An Introduction. In Handbook of East Asian New Religious Movements. Edited by Lukas Pokorny and Franz Winter. Leiden: Brill, pp. 231–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sŏ, Yŏngdae 서영대. 2001. Hanmar’ŭi Tan’gun undong’gwa Taejonggyo 한말의 단군운동과 대종교 [Movements of Tan’gun at the end of Chosŏn Dynasty and Taejonggyo]. Seoul: Research Association for the History of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Taejonggyo, chong’gyŏng P’yŏnsu-wiwonhoe 대종교종경 편수위원회. 2002. Taejonggyogyŏngjŏn대종교경전 [Scripture of Taejonggyo]. Seoul: Taejonggyo Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Taesunjillihoe, Kyomubu (대순진리회/大巡眞理會) 교무부. 1974. Chŏn’gyŏng 전경/典經 [Scripture of Taesunjillihoe]. Seoul: Taesunjillihoe Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gennep, Arnold. 1960. The Rites of Passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wach, Joachim. 1958. Sociology of Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weems, Benjamin B. 1964. Reform, Rebellion, and the Heavenly Way. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Chŏngnip 이정립. 1977. History of Chŭngsan’gyo 증산교사 (甑山敎史). Chŏnbuk: Headquarters of Chŭngsan’gyo 증산교본부. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Chŏngho 이정호. 1990. Chŏngyŏk 정역 正易 [Righteous Change]. Sŏngnam: Aseamunhwasa Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Ihūm 윤이흠. 1988. Chonggyo’wa ŭirye—munhwa’ŭi hyŏngsŏng’gwa chŏnsu 종교와 의례—문화의 형성과 전수 [Religion and Culture—Formation and Transformation of Culture]. 종교연구 [Studies in Religion] 16: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Sŭngyong 윤승용. 2017. Han’guk sinjonggyo’wa Kaebyŏk sasang 한국신종교와 개벽사상 [New Korean Religions and Kaebyŏk Thought]. Seoul: Mosinŭn Salramdŭl Pub. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).