Abstract

To attain peace after state-on-state war, there must be a belligerent occupation to establish control and security of a defeated state—but that is not enough. There is the concept of jus post bellum concerning the vanquished, which is critically necessary in practice, yet insufficiently developed and understood. Providing the history and tentatively trying to determine the elements that are contained in this concept are the present article’s purpose. Tracing the concept from the earliest Christian writers to the more secular present-day authors will aid in the prospective application of jus post bellum. Scholars, military officers, statesmen, religious leaders, and humanitarians need to understand and accept the basic elements of the concept. A clear understanding of the largely religious history behind these elements should assist in their acceptance and future practical application, once these are agreed upon.

1. Introduction

In my view, attaining a just peace after state-on-state wars requires a belligerent occupation and the application of the concept of jus post bellum. Leaving aside the belligerent occupation to the military and political science arenas, the concept of jus post bellum presents an opportunity for a just peace. I firmly believe that there is a practical application for this concept once the elements are agreed and accepted. I will argue that, to achieve this goal of returning sovereignty to the vanquished, there should be a phase of jus post bellum to complete that transition from control and security established under the belligerent occupation to a just peace. The end of a war does not lead the next day to peace but rather one might see the hungry, thirsty, ill clothed, homeless, the injured, and the sick. There is a process to accomplish the transition in the post-conflict time, called belligerent occupation, which, when coupled with the jus post bellum concept, might provide the best opportunity for a just peace.

An effort to resuscitate the Just War Theory into a more relevant, secular system was begun by the eminent scholar Michael Walzer due to the US war in Vietnam (Walzer 1978). Thus, the Just War Theory and the current developments need to be considered. The Just War Theory emanates from Aristotle to Kant to the current theorists working on completing the idea of Just War by including the concept of jus post bellum. The writings of Christian authors have been overlooked or minimized, yet have already provided a great deal to these well-established rules of jus ad bellum and jus in bello incorporated into the Just War Theory. I offer that the historical review of these contributors can form the basis for the development of the final part of these laws that of jus post bellum or law after war. The current discussions regarding the development of the jus post bellum concept will be explored to ascertain the proper elements.

If the goal is a just peace with the return the sovereignty to the vanquished people after a period of rehabilitation, then that period must be examined. For most of human history the idea of conquest was prevalent, but the oldest non-conquest ideas about this transitional period have been in the just war tradition. The just war tradition provides some guidelines, so the past is examined for knowledge transferable to the future in seeking a just peace after a war and belligerent occupation. To reach the goal of a just peace with a return of sovereignty to the vanquished that end point contained in jus post bellum must be articulated, understood, and accepted. This is the purpose of the instant effort.

Previous works on the jus post bellum focus on a generalized historical context, as they advocate for the inclusion of this final concept into the Just War Theory. A more thorough review of the historical context surrounding this concept focusing on the major contributors should assist us in articulating and understanding the entirety of this concept rather than the typical short vignettes that are directed at one or two historical figures or situations. Ignoring the broader historical context of the jus post bellum concept is typical of theoretical works in several academic fields and may miss the developmental evolution that has brought humankind to our present location poised to fill the gap between the Laws of War and Peace. The current lack of historical context seems to permit the present a la carte the inclusion of ideas hindering the development of jus post bellum as the third leg of the Just War Theory.

2. The Post-Conflict Phase of War

Union General William T. Sherman stated that war “… is all hell!” (Lewis 1932). There is no such pithy idiomatic expression for a war’s post-conflict phase, best described as that time from the end of major fighting until the vanquished nation regains the ability to govern itself. Remarkably, war, which is the ultimate breakdown of human civilization, is to be fought by civilized rules. Such rules of war have been developed over several thousand years and they continue to evolve in spite of their already long history.

From classical antiquity to the end of the Second World War, the post-conflict phase of war was almost completely ignored by the victors. This post-conflict phase of a state-on-state war is when peace can and should be established. The ultimate question is how to go about creating that peace between former enemies after such a war. I will offer that a carefully planned belligerent occupation coupled with a jus post bellum “reconstruction” phase can be a successful model that is based on the lessons learned in the implementation after the Second World War. Belligerent occupation “… refers to a situation where the forces of one or more States exercise effective control over a territory of another State without the latter State’s volition” (Benvenisti 2012). In other words, the belligerent occupation establishes the control and security necessary for the “reconstruction” phase in the chaotic aftermath of a state defeat in war. The failure to effectively conduct a belligerent occupation phase risks winning the war but losing the peace. Succinctly, absent a belligerent occupation in state-on-state wars, the post-victory peace could be lost. Yet, to return the sovereignty to the vanquished and enable a just peace requires another step in conjunction with this belligerent occupation. In my view that further step for “reconstruction” comes under the concept of jus post bellum. Together, a belligerent occupation and an applied jus post bellum phase situated between the Laws of War and Peace, I argue, would work to return the sovereignty to the vanquished and enable a just peace.

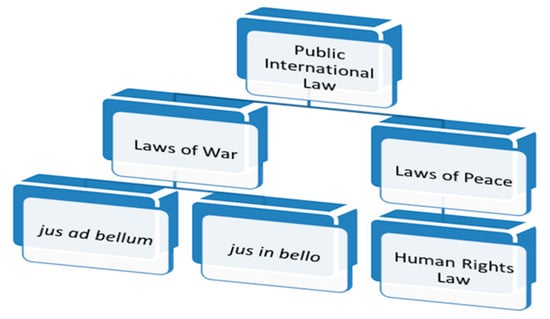

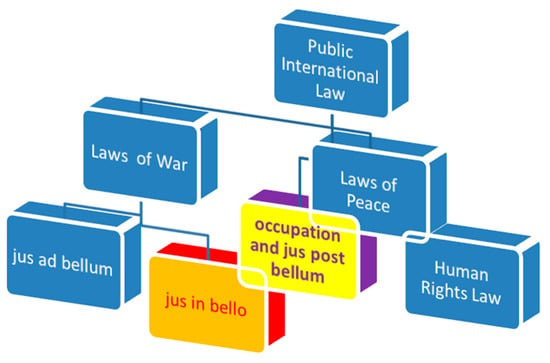

Yet, in the current conception of public international law, there is a gap between the Laws of War and the Laws of Peace. There is no bridge between these two different and distinct aspects of the human experience of war and peace. See Figure 1 for the traditional view of the Laws of War and Peace and Figure 2 for the belligerent occupation and jus post bellum between the Laws of War and Peace.

Figure 1.

Traditional View of the Laws of War and Peace.

Figure 2.

Belligerent Occupation and jus post bellum between the Laws of War and Peace.

I will address the Just War Theory and the evolving concept of jus post bellum, as this might be viewed as the second step following the belligerent occupation that connects the Laws of War to the Laws of Peace on the road to returning sovereignty to the vanquished. This connection is crucial for the practical applications of both belligerent occupation and the jus post bellum concept in a post-conflict situation. To make the latter practical, the elements of that concept must be articulated and agreed upon prior to any actual application.

The concept of “just war” (Schutz and Ramsey 1961) traces its lineage to the classical Greco-Roman and early Christian authors, primarily Aristotle, Cicero, and St. Augustine (Johnson 1981). As currently manifested, “just war” consists of two separate foundations (ICRC 2018). The first of these parts of the concept is entitled jus ad bellum, which means “right to wage war” (USALegal 2018). This phrase concerns whether a war is conducted justly or if entering into the war is justifiable. For example, an international agreement limiting the justifiable reasons for a country to declare war against another is concerned with jus ad bellum. The principles central to jus ad bellum are “right authority, right intention, reasonable hope, proportionality, and last resort” (ICRC 2018). I note that this first part, jus ad bellum, is addressed foremost to heads of states or heads of governments, hereinafter HOSHOGs.

The second part of the current concept of just war is labeled jus in bello or “law in war”. According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, jus in bello contains “provisions [that] apply to the warring parties irrespective of the reasons for the conflict and whether or not the cause upheld by either party is just” (ICRC 2018). Again, I am compelled to note that this part of the just war concept is addressed to the warfighters, those military commanders, officers, and troops that formulate and execute the war for a state. However, this does not excuse inhumane behavior committed or ordered by the HOSHOGs during the fighting or afterwards.

The putative concept of jus post bellum or law after war relates to the conclusion of war and it has had a traditional, albeit underdeveloped, place in the just war concept (Stahn 2008). When the end of combat is coming or has arrived, the military begins to think in terms of occupation and the law of occupation. The concept of jus post bellum “presupposes a concluded or concluding armed conflict with international actors …” (Pensky 2013). This putative third concept of the Just War Theory “… as discussed in international law is aimed at providing the legal means by which … the war-torn society will be taken through the post-conflict state of transition and brought into a state of just and stable peace” (Osterdahl 2012). Such a broad statement, as the above ventures well beyond the actions needed in an occupation by the victorious states under the Fourth Geneva Convention and current international law, yet it may provide some basis for further development of the ideal occupation notion. During and after a belligerent occupation, the concept of jus post bellum, as first described by Grotius, might provide that aforementioned absent step in the transition to a just and stable peace with the government and sovereignty of that vanquished state returned to the people. In any event, there must be a phase after the belligerent occupation to complete the transition to a just peace. Just peace will vary by specific circumstance, yet the end result is a durable situation or agreement that is acceptable for returning the county to the people.

What does this third part of the Just War Theory mean for the future? If jus post bellum becomes widely accepted, then the significance could have deep ramifications not only for the conduct of war, but especially for post-war occupation and “reconstruction” on the road to a just peace. I view this post-conflict state of transition as a two part effort consisting of belligerent occupation and then building a just peace, so that by “[s]etting clear guidelines for post-conflict occupation [this] will help to reinforce credibility and legitimacy in establishing a rule of law and achieving the key jus post bellum goal of building a lasting peace” (Benson 2012).

3. Development of the jus post bellum concept: The Christian Writers

Jus post bellum has a long, if relatively unnoticed, history. It will be traced from those ancient origins in order to assist in understanding the importance of that development and the potential relevance for the future. Because of the relatively unnoticed antecedents, that historical context will be examined to comprehend the pattern of behavior that led us to today with a view towards using it in the future to bridge the gap between the Laws of War and Peace.

Despite this unnoticed history, the post-conflict dilemma has not gone unaddressed. St. Augustine wrote in The City of God that “[w]hat, then, men want in war is that it should end in peace. Even while waging a war every man wants peace, whereas no one wants war while he is making peace” (Augustine 1972). The Spanish friars and theologians of the late middle ages, Francisco Vitoria and Francisco Suarez, concluded that a just cause in a just war must lead to a just post-war settlement (Solimeo 2003). Grotius articulated a precursor of jus post bellum by writing that “… the end and aim of war [is] the preservation of life and limb …” (Grotius 2012). The concept continues to be developed to this day due to a revival that began in the 1990s.

Saint Augustine developed the basis for just war and it is often mentioned as the progenitor of the jus post bellum concept as he holds combatants responsible for the ways in which a war is concluded and the conduct of the peace that follows (Augustine). He wrote “[t]he purpose even of war is peace” and his goal was that peace (Augustine). In his discourse on peace, Augustine was not sure that it could be obtained, but saw this as something to strive for but realized only in the city of God, the title of his book (Augustine). He applied this peace concept to everyone arguing that “[a]t any rate, even when wicked men go to war they want peace for their own society” (Augustine). Continuing, he observed “… the only means such a conqueror knows is to have all men so fear or love him that they will accept the peace he imposes on them” (Augustine). St. Augustine recognized the imposition of peace upon the vanquished by force, if necessary, or benevolence, as he penned “[t]he fact is that the power to reach domination in war is not the same as the power to remain in perpetual control” (Augustine). This passage indicates a clash between being the victor in a war and ruling during the peace that follows the conclusion of the war. An indication of the return of sovereignty is found in this passage showing the refinement of the jus post bellum concept. In The City of God, “Saint Augustine also defines just war as a means to re-establish and vindicate violated justice, and thus obtain peace. Therefore, one can wage war to punish a nation for the violation of just order” (Solimeo 2003). Despite warring against an unjust aggressor, peace must be the end result, so the virtuous victor must conduct their war and post-conflict operations with a view toward peace. Today, the basis for occupation law was planted and the re-establishment of peace as an end of jus post bellum was confirmed due to this original author of the Just War Theory.

“From Augustine’s time until the twelfth century there were few developments in the doctrine of the just war” (Tooke 1965). Gratian was an important contributor but mostly as an updated compendium of his own and others writings on the topic wherein “… he quoted the traditional answers, mostly from Augustine, and usually added brief conclusions of his own” (Tooke 1965). His combinations of Roman Law with Canon Law created a more vibrant and comprehensive view of law, along with how that law functioned in society. Just war for Gratian was to redress some actual injury and be authorized by a legitimate public authority (Gratian 1993).

So nearly a millennium passed until the next development of the Just War Theory occurred in the writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas, who posited the three tests to determine if a war is just. In Summa Theologica, he stated “[i]n order for a war to be just, three things are necessary. First, the authority of the sovereign … Secondly, a just cause … Thirdly, a rightful intention” (Aquinas 1981). St. Thomas Aquinas did not explain how this third thing might be tested but suffice it that “… a ‘just war’ in the 14th century was virtually a legal necessity as the basis for requisitioning feudal aids in men and money” (Tuchman 2002). Despite such writings, the right of spoil, more properly pillage, was preserved, especially in a just war. “It rested on the theory that the enemy, being unjust, had no right to property, and the booty was the due for risk of life in a just cause” (Tuchman 2002). Just war was often used to begin a conflict but the post-conflict phase retained the ancient practice of the right of conquest. Furthermore, St. Thomas Aquinas “… defends not only the necessity but the justice of that practice [post-conflict slavery], which he presents as beneficial to both conqueror and conquered, since it spares the life of the latter and secures for the former the services of a subject population” (Strauss and Cropsey 2006). While not specifically addressed to the post-conflict governance, but to governance in general, he argues that “[t]yrannical government is not just …” and might be overcome (Aquinas 1981). The requirement for good governance for all under the authority of the government is to be respected even in post-conflict servitude. Aquinas saw that war and peace were not tied to each other; that is, there was a gap that was to be filled (Aquinas 1981). Clearly, Just War Theory has evolved slowly with the development of the test for the beginnings of a just war. As with many developmental concepts, the remnants of the historical context, in this case, conquest, still prevails after the war. Yet, we begin to see the idea that the vanquished are to be spared, a principle that remains to this day in the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions, even if those saved were subject to work for the victor.

Theologians after Saint Thomas Aquinas, particularly Francisco de Vitoria (1485–1546) and Francisco Suarez (1548–1617), completed the scholastic theory of just war with the principle of proportionality, and that all peaceful means must be exhausted before having recourse to war. Vitoria “… allowed that a militarily necessary storming of a city could be undertaken even though this would inevitably result in violations of the rights of noncombatants in the city such historical evidence suggests a moral acceptance of the possibility of preserving a value by wrong means” (Johnson 1981). However, such a thought, while being permissible, is tempered by the limitations that are placed on this type of attack by the general laws of war, which today we would call proportionality; explained as “… foreseen but unintended harms must be proportionate to the military advantage achieved” (Lazar 2013). These theologians point out that the need for justification only applies to offensive, not defensive war, since the principle of legitimate defense in the face of an attack is evident (Solimeo 2003). Vitoria goes farther in taking a critical view of the arguments for Spanish colonization of the western hemisphere by establishing the Amerindians were to be respected, as well as the recognition of their property rights and political institutions, as these could not be revoked without just cause or deprived due to their not being Christians or being sinners (Vitoria et al. 1991). In the end, “Vitoria understood war as a quasi-judicial activity properly resorted to only in cases where there was no judiciary to adjudicate disputes” (Bellamy 2018). Hence, Vitoria wrote of war “... it must not be waged to ruin the people against whom it is directed” (Vitoria and Nys 1917). One foundation of jus post bellum is being laid. Looking to the post-conflict times, Vitoria argues that the “… Princes have authority over foreigners so far as to prevent them from committing wrongs and this by the laws of nations” (Vitoria and Nys 1917). Here is a recognition that a period of belligerent occupation and, I argue, an encompassing period of jus post bellum is needed to prevent further war and find a return to a just peace.

Friar Suarez was a student of both St. Thomas Aquinas and Vitoria. In furthering their ideas and occasionally departing from these concepts, he was “… perhaps the first author to specifically talk about the three phases [of Just War Theory] widely recognized today, jus ad bellum, jus in bello, and jus post bellum” (Brunstetter and O’Driscoll 2018). More exactly, he wrote “[t]hirdly, the method of [war’s] conduct must be proper, and due proportion must be observed at its beginning, during the prosecution, and after victory” (Suarez 2015). Despite their advances, the Friars were caught in the thinking of medieval times, as the world was changing due to the expanding empires being amassed during the European explorations. Regardless of the remaining medieval problems, such as the right of spoil, today, we can see these medieval scholars’ influence in the Laws of War regarding state action in exhausting other remedies before going to war, which is the basis for war being a proper cause sometimes via modern institutions, such as the United Nations Security Council, the idea of proportionality, and the inherent right of self-defense.

Writing on the combination of these explorations and, especially, the incessant wars, Hugo Grotius, a seventeenth century Dutch legal scholar, would have a major influence on the Just War Theory as he did on international law. Grotius wrote “God wills that we should protect ourselves, retain our hold on the necessities of life, obtain that which is our due, punish transgressors, and at the same time defend the state … Therefore, some wars are just” (Grotius 1950). Although being viewed as a secular scholar, Grotius made many references to God, religion, and morals throughout his books, so as to be considered a Christian author, but from a Protestant, Calvinistic perspective (Brown 2008).

Grotius did not countenance fighting to the bitter end as this extends the war and the death toll, as it poisons the post-war administration. The preservation of all lives is the point of the caution against fighting when there is no opportunity to achieve any further good. Encapsulated here is the military necessity principle that useless fighting should be avoided based upon a responsibility to mankind, as Grotius holds rulers, specifically, and advisors, indirectly, responsible for any violations of this principle. Certainly, these admonitions apply during a conflict and we see the extension of those restrictions in the post-war period. The concept of moderation, for which Grotius is famous, is extolled, as it was not always practiced in those times or in more recent conflicts. This is a new path laid out by Grotius for his and successive generations (Nussbaum 1961). The theme of moderation was an attempt to ameliorate the impact of war and the post-conflict phase in an effort to establish a lasting peace. Grotius did not want vengeance to result in the deaths of more people, causing further anger to make another war more probable. Such moderation will carry over into the ideal occupation, as a decisive military defeat is called for, yet this does not mean destroying a society and this was not done in any of the successful belligerent occupations after the Second World War. This “… strategically decisive [military] victory should be one that decides who wins the war militarily…Politically understood, a decisive victory should be one that enables achievement of a favorable postwar settlement” (Gray 2002).

Grotius wrote several cautions regarding moderation in devastating enemy lands, albeit he does argue that some lying of waste may be lawful (Grotius 2012). Since the book of Deuteronomy, international law requires refraining from devastation during war (Deuteronomy 20: 19–20). Yet, Grotius insists that this restraint is “[s]till more binding … after a complete victory” (Grotius 2012). Grotius foresaw the “occupation” after the war and did not want any devastation to provide an opportunity for a future war based on these grievances. He calls for moderation in dealing with sacred buildings and sacred things, “… reverence for divine things urges that such buildings and their furnishings be preserved …” (Grotius 2012). Grotius goes on “… such moderation gives the appearance of great assurance of victory and that clemency is of itself suited to weaken and conciliate the spirit” (Grotius 2012). His overarching desire is to lessen the impacts of war, both during the war and in the post-conflict phase by advocating for moderation. According to Grotius, while, there should be restraint during the war according to jus in bello that restraint applies in a more binding manner once there is a victory.

Grotius suggests that such moderation in warfare is not only an act of humanity, but is often an act of prudence. In another recommendation, he advised the victors “… to leave them [the vanquished] their own laws, customs, and officials” (Grotius 2012). Expanding on his advisements, he asserts that the conqueror as “[a] part of this indulgence is not to deprive the conquered of the exercise of their inherited religion [and allow for] … taking steps to prevent the oppression of the true faith” (Grotius 2012). He ends this short but important chapter with his final caution that “… the conquered should be treated with clemency, and in such a way that their advantage should be combined with that of the conqueror” (Grotius 2012). In the post-conflict phase, Grotius continues to advocate for moderation to assist in the restoration of an enduring and just peace. Specifically, he indicated that the ruler and other functionaries be left in place to allow for a return to what is normal, as this was not always the case in his days. Similarly, maintaining the laws and customs would contribute to that sought after peace by retaining some sense of the normal. Such magnanimity in maintaining familiar people along with the familiar laws and customs is another contribution to the peace process. These principles have been acknowledged, as these are contained in The Hague and Geneva Conventions.

In the Twentieth Chapter with the lengthy title, “On the good faith of states, by which war is ended; also on the working of peace treaties … on arbitration, surrender, hostages, and pledges”, Grotius advises on how to end war and essentially rebuild the vanquished society (Grotius 2012). His concern for the post-conflict phase is evident in the above title, as it informs us of the good faith that is required between the warring factions to end a war as well as how to interpret peace treaties. In the “General rules for the interpretation of peace covenants” section, he showcases this generosity and moderation in interpretation. Advocating that “… the more favourable a condition is, the more broadly it is to be construed, while the further a condition is removed from a favourable point of view, the more narrow is the construction to be placed on it” (Grotius 2012). Here, he is seeking some equality between the parties. Simply stated, Grotius wants treaty interpreters to construe the peace agreement’s favorable clauses with as much latitude as possible, but the restrictive sections as narrow as practicable given the circumstance. Further along in that same section, he reasons “[s]ince, however, it is not customary for the parties to arrive at peace by a confession of wrongs, in treaties that interpretation should be assumed which puts the parties as far as possible on an equality with regard to the justice of the war” (Grotius 2012). These words are trying to establish a lasting peace via the treaty that was signed by the parties, so that the interpretation in the post-conflict phase should flow toward that peace. Equality in justice between the former belligerents will lessen the cry of victor’s justice, thus reducing revengeful thoughts and actions thereby reducing the likelihood of the resumption of war or the instigation a new one based upon the injustice of the past conflagration or its peace.

Finally, Grotius provided his “[c]onclusion with admonitions on behalf of good faith and peace” (Grotius 2012) to guide his readers:

[y]et before I dismiss the reader I shall add a few admonitions which may be of value in war, and after war, for the preservation of good faith and of peace … And good faith should be preserved, not only for other reasons but also in order that the hope of peace may not be done away with. For not only is every state sustained by good faith… but also that greater society of states…Justice, it is true, in its other aspects often contains elements of obscurity; but the bond of good faith is in itself plain to see …(Grotius 2012)

He establishes that, to maintain the peace after war, there must a modicum of good faith on both sides. This is a two tiered analysis, in that each state individually and the international community collectively are served by this good faith. The post-conflict administration of a vanquished foe presents many problems that absent some degree of cooperation based upon good faith, the peace will not last and the entities could return to open or guerilla warfare or insurgency. Thus, he warned that this “humanity” should begin during hostilities by fighting “cleanly”, not excessively and, when there is no reason for continued fighting, combat should cease. Grotius admonished the fighters that during the prosecution of war, peace should always be kept in view (Grotius 2012). Continuing on, he noted that safety in the post-conflict peace is kept by “… condonation of offenses, damages, and expenses” (Grotius 2012). Further, he counseled the conqueror to exercise moderation since “… peace is bounteous and credible to those who grant it while their affairs are prosperous” (Grotius 2012), then he reminded both sides that war is ever present. In his final effort to establish the hold of lasting peace, he directly addressed the effort of good faith that each of the former combatants will need to put forward

[m]oreover peace, whatever the terms on which it was made, ought to be preserved absolutely, on account of the sacredness of good faith … and not only should treachery be anxiously avoided, but everything else that may arouse anger … Not only should all friendships be safeguarded with the greatest of devotion and good faith, but especially those which have been restored to goodwill after enmity.(Grotius 2012)

Former enemies will have to work to preserve the peace arranged in the treaty, so the delicate peace will grow rather than lead to another war or operations less than war.

After the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, the concept of just war was pushed aside for more salient issues. Some effort to revive this concept came from Immanuel Kant. In a further articulation of the Just War Theory, Kant made clear there is a tripdichon of the right to war, right in war, and the right after war (Kant 1991). At least one scholar asserts that Kant “… essentially invents new just war category, jus post bellum, to consider in detail the justice of the move from war back to peace” (Orend 2007). Kant argues that the victors cannot punish the vanquished or seek compensation from the defeated, but the victors must respect the sovereignty of those now defeated in war. His view of the aggressor but now defeated people is they “… can be made to accept a new constitution of a nature that is unlikely to encourage their warlike inclinations” (Kant 2003). It is unmistaken; Kant was concerned about the “… fairness of peace settlements, respect for the sovereignty of the vanquished state, and limits on the punishment of people (i.e., reparations)” (Kant 2003). He did mention peace treaties in his book, Perpetual Peace as a preliminary article, which are those actions to be taken immediately to establish peace, emphasizing that such agreements must not contain any secret clauses likely to result in a future war (Kant 1991). Kant’s contributions to the development of jus post bellum were considerable, but largely unrealized until the 1990s.

During the conceptualization and memorialization of the Laws of War in the 19th and 20th centuries, “[s]urprisingly, this ‘third leg’ [jus post bellum] in the theory of warfare disappeared …” (Stahn 2008) As the development of the Laws of War were being hammered out, the jus ad bellum and jus in bello parts of the just war concept absorbed all of the attention with the Hague Conventions and later Geneva Conventions taking enormous efforts. Jus post bellum laid mainly dormant until being revived and given the current name in 1994.

Continuing to develop this concept, we might ask if no legal basis exists, why take the effort to develop this third part of the Just War concept? Perhaps “[t]he global wars of the twentieth century illustrate the criticality of war-termination policy and operational planning for the post bellum stage of war” (Iasiello 2004). With what some scholars indicate is little international law to guide us, the current inclination is to look to the moral concept of just war.

4. Development of the jus post bellum Concept: The Concept Resurrected

The concept of jus post bellum remains under the process of development. My own experience in confronting the issues of post-war devastation resulting from the capacity of modern war led me to explore the concept of jus post bellum, a developing area of the Just War Theory. Those scholars exploring the Just War Theory indicate although it “… has long included jus post bellum concerns, Michael Schuck (1994) was the first to propose specifically adding the jus post bellum framework to Just War Theory” (Clifford 2012). However, jus post bellum in “[t]he contemporary period is characterized by intense scholarly, legal, and socio-political debates about the conceptual framework…” (Rozpedowski 2015). So this intensity has also spawned a lack of clarity, even to the point of what to label the concept. Specifically, is it jus post bellum, jus ex bellum, or jus ante bellum? (Allman and Winwright 2012). The definitional breakdown proceeds further, as it appears that every scholar proposes their own specificity on the concept that I have called jus post bellum in this work. We need to adopt a suitable set of elements to further develop this concept.

Our focus regards this boom in interest and scholarly writing, together with the accompanying disarray. Elements related to the concept of jus post bellum must be ascertained in order to determine the direction of the conceptual development. Using a set of selected and recognized elements of the concept; we will determine where the scholars of this phenomenon agree in order to further facilitate a coherent starting point for continuing discussion. The identification of the elements of the jus post bellum concept that scholars agree on will permit some guidelines for the international community, as it seeks a just peace after the war and belligerent occupation.

In 2013, the American Society of International Law (ASIL) brought a multitude of scholars together under the editorial direction of Larry May and Elizabeth Edenberg to look at jus post bellum and transitional justice (May and Edenberg 2013). The former seeks to secure the peace while the latter seeks democratization (May and Edenberg 2013). The editors of this volume identified six elements of the jus post bellum concept. I will accept the concept of jus post bellum that was advanced by these editors as made up of six elements: retribution, reconciliation, rebuilding, restitution, reparations, and proportionality (May and Edenberg 2013). We will use these elements in the search for the jus post bellum concept in the writings of these selected scholars to ascertain whether there is any agreement on the elements perhaps just differently labelled. I will determine where the scholars of this phenomenon agree in order to further facilitate a coherent starting point for continuing discussion using this set of selected and recognized elements of the concept.

Before beginning the search for any putative commonality, a clarification of the six elements is in order, so that we are working from a common beginning to possibly clarify the jus post bellum concept. As used in the ASIL project, our first element is retribution defined as “… bringing those to account who committed wrongs either by initiating an unjust war or by waging war unjustly” (May and Edenberg 2013). The possibility of war crimes trials or domestic criminal trials could include trials of popular leadership in the vanquished state. War crimes trials were conducted after the Second World War in Nuremberg and Tokyo, although there were many other trial locations in the Pacific theater of war (Wilson et al. 2017). The recent conflicts in the Balkans and Rwanda resulted in the establishment of Courts and trials, so international legal precedent does exist for conducting these post-conflict tribunals. Grotius wanted to hold people responsible writing “[t]heir accountability [for] all those things … which ordinarily follow in the train [course] of war …” (Grotius 2012). Retribution existed for many thousands of years, but this jus post bellum element is any trial based accountability.

Certainly, such prosecutions may have an impact on the next element, reconciliation—the coming together of the former adversaries to establish, as Grotius suggested “… a lasting peace where mutual respect for rights is the hallmark” (May and Edenberg 2013). St. Augustine noted such reconciliation when writing “[t]herefore, even engaging in war, cherish the spirit of a peacemaker, that, by conquering those whom you attack, you may lead them back to the advantages of peace …” (Augustine 1972). Expanding on this theme, Augustine continued “[a]s violence is used towards him who rebels and resists, so mercy is due to the vanquished or the captive, especially in the case in which future troubling of the peace is not to be feared” (Augustine 1972). Such a peace was also written about by Grotius, concluding, “… the conquered should be treated with clemency, and in such a way that their advantage should be combined with that of the conqueror” (Nussbaum 1961). As to this specific element, “… Grotius opened a new path by setting forth what he called the temperamenta of warfare … going into extensive detail, he urged moderation for reasons of humanity, religion, and farsighted policy …” (May and Edenberg 2013). The idea of reconciliation by moderation permeates this book and it is prominent in many chapter titles, as Grotius sought to establish that farsighted policy in the post-conflict phase.

The destruction and devastation of war necessitate our next element: rebuilding. This element is described as calling on “… all those who participated in the devastation during the war to rebuild as a means to achieve a just peace” (May and Edenberg 2013). Again, Grotius posited “… and all the soldiers that have participated in some common act, as the burning of a city, are responsible for the total damages” (Grotius 2012). Simply stated, this element requires some rebuilding, perhaps by those that created the damage being held responsible for the reconstruction, but certainly allowing for the reconstruction by the greater international community as a contribution to that end result of a just peace.

Next, we consider the restitution element of the jus post bellum concept. This means “… returning goods or their equivalent that have been taken” (May and Edenberg 2013). Historically, this element was written so that in an unjust war, the elites who directly caused the war such as a ruler or the advisors must make restitution (Grotius 2012). Under this view, restitution applies to all of the consequences of war if the ruler or the advisors provided orders or advice (Grotius 2012). Grotius informed us “… those persons are bound to make restitution who have brought about the war, either by the exercise of their power, or through their advice.” (Grotius 2012). Not content to seek physical restitution, Grotius noted “[a]nother form of moderation in victory is to leave to the conquered kings or people the sovereignty power which they had held” (Grotius 2012). Returning other intangibles included the idea that “… the conquered should be treated with clemency, and in such a way that their advantage should be combined with that of the conqueror” (Grotius 2012). Thus, restitution as an element is broader than the mere returning of goods, but also a restitution of the entire previous existence to those impacted by war or perhaps more appropriately a return to normalcy in light of the experience of war.

Our penultimate element is reparations explained as “… repair or remedy for goods that have been damaged or for injuries received” (May and Edenberg 2013). Again, we see the influence of Grotius in providing first for the sparing of many things including sacred buildings and their furnishings but more significantly “[t]here are certain duties that must be performed toward those from whom you have received an injury” (Grotius 2012) Clearly, this has been viewed as a prohibition of cruelty but likewise a duty to make whole on both sides of the war, so the just might need to provided reparations to the vanquished. “Reparations are often crucial for reestablishing trust among the parties at war’s end” (May and Edenberg 2013). Such trust between the former belligerents is essential for the development of a just peace.

Lastly, we consider the element of proportionality. “One way to understand post bellum proportionality is to see it as applying to each of the other five [elements].” (May and Edenberg 2013). Thus, there must be an established balance in the post-conflict agreement and its interpretation, as well as the implementation of the peace. Again, Grotius provided some guidance “[s]ince, however, it is not customary for the parties to arrive at peace by a confession of wrongs, in treaties that interpretation should be assumed which puts the parties as far as possible on an equality with regard to the justice of the war” (Grotius 2012). We might conclude from this passage, there is equality between “… the belligerents themselves [as they] are now placed on the same footing” (Nussbaum 1961). Among the many Grotian advisories regarding proportionality is “… [n]ot only should all friendships be safeguarded with the greatest of devotion and good faith, but especially those which have been restored to goodwill after enmity” (Grotius 2012). Here, we have a clear indication that Grotius saw this as a post-conflict advisement, as he refers to the idea of good will after the late unpleasantness of war. We have examined the elements with some historical reference to the earlier writers to place the concept of jus post bellum into a framework for further exploration.

5. Establishing the Elements of the jus post bellum Concept

After explaining the ASIL elements, we look to the writing of scholars on this topic. Acknowledging that there was not an agreed definition of jus post bellum, “[w]e need to develop jus post bellum criteria similar to those generally accepted for the other two categories [jus ad bellum and jus in bello]” (McCready 2009). Using the aforementioned six elements and keeping the end state of a just peace in mind, as Grotius recommended, I will attempt to establish the actual elements of the concept of jus post bellum. Methodologically, I have selected a wide diversity of scholars’ writings to help ascertain whether there is some common ground in terms of those six elements. Simply put, we need to adopt a suitable set of elements to further develop this concept.

Undertaking a brief introduction before performing a cross scholar comparison of these elements should show that this is a diverse group of jus post bellum writers. Gary Bass opined “[i]t is important to better theorize post war justice—jus post bellum for the sake of a more complete theory of just war” (Bass 2004). Professor Bass argues for the completed Just War Theory that includes the concept of jus post bellum. Alex Bellamy differentiated minimalist and maximalist moral positions, whereby “[m]inimalists envisage jus post bellum as a series of restraints on what it is permissible for the victors to do once the war is over … maximalists argue that victor acquire certain additional responsibilities that must be fulfilled for the war as a whole to be considered just” (Bellamy 2008). Professor Bellamy considered the moral aspects in his concept as the third leg of the Just War Theory.

Antonia Chayes posited that it is hard to situate a post-conflict obligation in international legal requirements although there are rules that govern occupation that date back to the 19th Century. (Chayes 2013). As a lawyer from the so-called “New Haven School of International Law”, Chayes takes a treaty based approach to our topic. Cindy Holder has argued that to realize a just peace

[a]t a minimum … requires preventing a new outbreak of conflict and foreclosing the occurrence or recurrence of humanitarian violation or human rights abuses … In some context, then, duties to establish sustainable peace include duties to investigate gross violations of human rights, disseminate the findings of investigation, and ensure that victims have access to remedies and repairs.(Holder 2013)

Her view reflects the transitional justice perspective that will be discussed in a few pages. The next two scholars look at the military ethics of the jus post bellum concept. Chaplain and Rear Admiral, Louis V. Iasiello, the twenty–third Chief of [US] Navy Chaplains, concluded that the post bellum phase is such a challenge to the victor, due “… in part, [to] a failure to update and revise the just war theory, a theory that has survived for millennia because it is ‘an historically conditioned theory’, one in a state of perpetual transition” (Iasiello 2004). Dr. Davida Kellogg, a Professor of Military Science, has postulated

[t]he international law of war has barely begun to deal with the questions of where to try cases in which the aggressor is a diffuse political or religious entity rather than a nation … whatever is decided to be properly convened, constituted, and conducted court for such cases, the high moral purpose of jus post bellum—to do justice in the wake of war—must be well and truly served by them, and must be seen to be so.(Kellogg 2002)

Shunzo Majima, a professor at the Center for Applied Ethics and Philosophy at Hokkaido University, reviewed the US occupation of Japan after World War II. He asked “[w]hat elements might constitute jus post bellum—does it include restoration, reparation, retribution, repatriation, reconstruction, rehabilitation, recognition, and/or reconciliation, for example?” (Majima 2013). Similar to the instant work, Majima is trying to determine the right blend of elements in the jus post bellum concept to achieve the goals of a just peace. His list reflects those that were proposed by the ASIL study.

Brian Orend, a Just War theorist with a human rights focus, argues there should be a third category of the Just War Theory called jus post bellum that can no longer be ignored. He argues further “… there should be another Geneva Convention, this one focusing exclusively on jus post bellum” (Orend 2007). Orend seeks “… both moral and legal completion and comprehensiveness in connection with the ethics of war and peace” (Orend 2007).

Inger Osterdahl from Uppsala University in Sweden offers “[i]t is presumed, moreover, that, although there undeniably exists law that is currently being applied by all working with the different aspects of post—conflict management, both the law and the societies (re)constructed would gain more from systematic thinking about jus post bellum” (Osterdahl 2012). Osterdahl believes that the concept of jus post bellum can contribute a great deal to the formulation of a just peace.

Max Pensky, a philosophy Professor at Binghamton University (New York) writes [c]urrent efforts to develop a robust and practical conception of jus post bellum have rightly focused on the requirement for a determinate set of principles specifying just what a satisfactory account of jus post bellum should consist of … jus post bellum principles must be complete, consistent, and implementable.(Pensky 2013)

Professor Pensky indicates that the concept must also be able to be utilized in the chaos following a war. Carsten Stahn, an Associate Legal Advisor at the International Court of Justice, relies on history to argue “… that some of the dilemmas of contemporary interventions may be attenuated by a fresh look at the past, namely a (re)turn to a tripartite conception of armed force based upon three categories: jus ad bellum, jus in bello, and jus post bellum” (Stahn 2006).

After this brief review, there is great variety in the concept of jus post bellum, as well as many elements that make up these varying views. From the foregoing, we can glean that the jus post bellum concept is currently all things to all people, rendering its definition subject to each individual author and subject to challenge in each scholar’s writings. This approach will not permit much forward progress, as these scholars target each other’s proposals instead of trying to define the concept in generally acceptable terms.

6. Seeking the Elements of jus post bellum

Elements of jus post bellum were suggested in the 2013 ASIL study, but are these accepted by scholars? To answer this query, I will review each scholar’s writings regarding the agreed upon six elements of jus post bellum determining if there exists any concurrence. Please see Table 1, below.

Table 1.

Scholars and elements of the jus post bellum concept.

A quick look at this table shows that the element of retribution has a nearly universal subscription by these scholars. However, a fundamental disagreement over the element of retribution and transitional justice exists. Further, there is a nascent but strong effort to develop a “right to the truth” that includes a “right to a judicial remedy” (Klinker and Smith 2014). This topic is noted, but well beyond our current effort. Returning to these two schools of thought, one favoring leniency and the other more stern measures is summarized as “… [v]ictors should be magnanimous to extinguish any desire for revenge by the vanquished … [or] Victors should be harsh to ensure that the enemy’s defeat is irreversible” (Raymond 2010). At what point do these competing ideas of retribution coalesce, if at all? Can the so-called “peace versus justice” debate be resolved? (Teitel 2013). The consensus regarding retribution does not really help us, due to the differences, even when the scholars are in agreement. Although some form of justice does seem to be acceptable to these scholars, it might be required to ensure a just peace on a case specific basis.

Previously, the definition of retribution was provided as bringing those to justice who stand accused of initiating or conducting an unjust war. Historically, Grotius advocated for an equality of justice between the former enemies, as he recommended moderation. Michael Walzer argued “[t]rials like those that took place at Nuremberg after World War II seem to me to be both defensible and necessary; the law must provide some recourse when our deepest moral values are savagely attacked” (Walzer 1978). Walzer calls for retribution, but stops short of tangentially specifying how that might be done. Cautioning, Walzer states that such a trial might also harden the animosity between the former enemies rather than treating the defeated “… morally and strategically, as future partners in some sort of international order” (Walzer 1978). Orend believes that war crimes trials are one of two parts of the post-war punitive settlements that does work (Orend 2007). While he does not spend much ink on the topic, he concludes that war crimes trials are necessary, as he argues that there must be a “[p]urge [of] much of the old regime, and [to] prosecute its war criminals” (Orend 2007). As to who should be prosecuted, he offers “… clearly, anyone materially connected to aggression, tyranny, or atrocity cannot be permitted a substantial role in the new order” (Orend 2007). Concurring, Kellogg strongly advocates for war crimes trials for the purpose of holding those guilty of war aggression and other crimes accountable. We are again reminded “[s]uch trials, however, are the means to an end, not an end in themselves” (Kellogg 2002). Hence, we seem left with the examples from the post-World War II era as the models, albeit those tribunals were not perfect and would be prospectively in need of some updating prior to being utilized in any effort to establish a just peace.

There exists another dichotomy in the retribution element of the jus post bellum concept being between law and morality. Grotius recognized this, as was later related “… the laws of war … might as a matter of fact allow many things that in the last analysis cannot be justified morally” (Holmes 1999). Simply stated, “… peace often means accepting a host of injustice” (Burke and Mitchell 2009). Other scholars contend that this is not a dichotomy, but much more, as found in the “… intense scholarly, legal, and socio-political debates …” adding yet more levels of analysis and further obfuscating the development of the overall jus post bellum concept (Rozpedowski 2015). Even within the legal side of the equation,

a central component of the transitional justice principle of the rule of law is the fair application of laws. People are not all in the same position (some may be wrongdoers and some not) and so the mechanical application of the laws may cause injustice if those special circumstances are not taken into account” These writings posit a multi-disciplinary approach to the continuing development of the jus post bellum concept.(May and Edenberg 2013)

If, indeed, “… the most consequential reordering moments in international relations have occurred after major wars …” then there must be found a way to deal with post-conflict justice (Ikenberry 2000). In the Majima article dealing with the American occupation of Japan after World War II, he found “… that the victors did not exploit or excessively punish the vanquished …” (Majima 2013). So Majima addressed the issue of the non-prosecution of the Japanese Emperor that was called for in the perfectionist model of jus post bellum. The perfectionist model “… requires that all principles [of a just belligerent occupation prior to application of jus post bellum elements] be satisfied and would consider the occupation to be unjust if any one or more of the principles was not met in a strict manner” (Majima 2013). However, he considered the holistic model that “… does not necessarily require that all principles be met exactly but focuses more on the positive extent of overall achievement” (Majima 2013). Professor Majima concluded, “… the principle of retribution is considered to be met to some extent, despite the fact that the emperor escaped indictment, because justice was served by punishing other perpetrators” (Majima 2013).

This case study of Japan might hold some ideas for the development of the jus post bellum concept in the more traditional venue of state-on-state wars. This success in Japan might be due to the learning that took place in the German occupation where the Allies began with lustration. The term “lustration” means “… the purification of state institutions from within or without” (Clifford 2012). What this means in practice is that some “… screening of candidates for public office; second, the barring of candidates from public office; and third, the removal of holders of public office” usually to sort out those former regime members that cannot be rehabilitated (Clifford 2012). Suffice it to say that the lustration did not work well in Germany or more recently in Iraq, as these party members knew how to run various utilities, perform services, and conduct other governmental functions. Yet, “Allied policy at the end of World War Two reminds us that regime change can be justified in the aftermath of a just war” (Walzer 2006). In Japan, the functioning government at the time of surrender remained essentially in place, except at the very top and continued to work as the government under occupation. In Iraq, the screening of potential candidates for public office whether for inclusion or exclusion or removal from office did not work well, due in large part to the vetting process that was conducted under Ahmed Chalabi but the change in the former regime was undertaken to separate them from the new Iraqi Government (Rumsfeld 2011). In these matters of vetting candidates in Iraq “[t]here was a balance between purging the older order and depriving the new Iraqis of the human capital they needed to run the country” (Trainor and Gordon 2013). Brian Orend, a Just War theorist, believes that war crimes trials are one of two parts of the post-war punitive settlements that does work (Orend 2007). While he does not spend much ink on the topic, he concludes that war crimes trials are necessary, as he argues that there must be a “[p]urge [of] much of the old regime, and [to] prosecute its war criminals” (Orend 2007). As to who should be prosecuted, he offers “… clearly, anyone materially connected to aggression, tyranny, or atrocity cannot be permitted a substantial role in the new order” (Orend 2007). A just peace seems to require some form of justice.

Another issue that warrants mention is the application of retribution to what have been called diplomatically, non-state actors, or, more colloquially, terrorist. This issue is one of the delays in the current negotiations to end the Columbia-FARC war; specifically, should FARC rebels who committed atrocities go to jail (Muñoz and Vyas 2016). Dealing with non-state actors after a war might be more involved than bringing justice to a vanquished state or quasi-state and it would require another study beyond the present effort.

Reconciliation is our next element of the jus post bellum concept. From our chart, we see the element of reconciliation is not as highly regarded for post-conflict peace as might otherwise be thought. St. Augustine saw the need for peace after war “… it is an established fact that peace is the desired end of war. For every man is in quest of peace, even in waging war, whereas no one is in quest of war when making peace” (Augustine 1972). Chaplain Iasiello, not surprisingly, is a proponent of reconciliation under what he termed “a healing mind-set” that formed one of his seven criteria for jus post bellum (Iasiello 2004). By this phrase, he means that the trauma of war across many levels of existence needs to be addressed after the conclusion of any war. Simply stated, everyone, including the victors, needs to heal, eventually. Continuing, Iasiello recommends

[i]t would be constructive if both the victors and the defeated entered this post-conflict phase in a spirit of regret, conciliation, humility, and possibly contrition. Such a mind-set may further the healing of a nation’s trauma and thus enhance the efforts to seal a just peace.(Iasiello 2004)

Evident here is the concern for this reconciliation to establish the peace and try to return to some sort of normal life, even if the complete ante bellum life cannot be attained.

Walzer, in his seminal book, Just and Unjust Wars, compared reconciliation after an international war to an inter-family feud. In his example, he explained that there might be the occasional killing of men folk from time to time but if a woman or child were to be killed even by accident or mistake, all hell would break out. Such an occurrence could end in a family being wiped out or driven away. Yet, he states “[s]o long as nothing more happens [than the occasional male depopulation] the possibility of reconciliation remains open” (Walzer 2006). This hoped for reconciliation would be instrumental in re-establishing relations between the vanquished state and its people as well as between the defeated state and the victors.

Pensky looks at reconciliation from the angle of transitional justice. This view of reconciliation takes up the “peace versus justice” debate and how instead of either peace or justice there might be an ameliorating effect by the use of amnesty instead of prosecution. He argues that such an approach might help to resolve the hard issues “… in cases where reconciliation and criminal justice have come into conflict …” (Pensky 2013). Stahn encapsulates the element of reconciliation when he offers sketches of post-conflict law, including

a trend towards accommodating post-conflict responsibility with the needs of peace in the area of criminal responsibility … Today, it is at the heart of contemporary efforts of peace-making. Modern international practice, particularly in the context of United Nations peace-building appear to move towards a model of targeted accountability in peace processes, which allow amnesties for less serious crimes and combines criminal justice with the establishment of truth and reconciliation mechanisms.(Stahn 2006)

Reconciliation for many of these scholars is wrapped into the criminal justice aspects of the post-conflict phase of war. Other scholars take a wide aperture approach, viewing the element of reconciliation broadly as to the entirety of society. Yet again, we observe the difference that one term has for the scholarly community writing on jus post bellum. Despite all of these well-intentioned efforts to seek the element of reconciliation, only five of our selected authors mentioned the element either directly or indirectly. However, this element ranks third of six among our scholars for inclusion as an element of jus post bellum.

Changing directions, we now consider rebuilding as the next element. Recall that the definition of rebuilding was quite broad, and this is reflected in the writings about this element. Bass wrote about rebuilding in both political and cultural terms. In the political sense, the victors “… have no right to reconstruct a conquered polity simply out of self-interest ... or reconstruct a polity for the victor’s economic, military, or political gain” (Bass 2004). Later, Bass makes an exception to the preceding statement when he encounters the genocidal state. Regarding the political reconstruction of the genocidal state, Bass argues “… jus post bellum must permit foreigners to interfere in the defeated country’s affairs in ways that can reasonably be expected to prevent a new outbreak of an unjust war” (Bass 2004). Walzer likewise joined in the conclusion that for a temporary period, the victor could provide political education for the followers of a nightmare regime (Walzer 2015). Bass insists, “… the victors have no rights of cultural reconstruction” (Bass 2004). Bellamy reports “[o]ne of the few elements of the UN’s 2005 reform negotiations to win almost universal consensus was the idea of creating a peacebuilding commission to oversee and coordinate the UN’s role in post-war reconstruction” (Bellamy 2008). Bellamy continues that the creation of this Peacebuilding Commission promotes the idea that the international community has “… a collective responsibility for rebuilding states and societies after war” (Bellamy 2008). This new development answers some of the questions regarding the role of the international community as well as who pays for the rebuilding. Chayes states that post-conflict lessons can be learned such that the international community must

… invest more in the training and mentoring civil servants of the host country, and to work with them for as long as it takes to help build a government that performs for the people. Such investments are cheaper maintaining an occupation for years beyond local tolerance. Donor priority must give way to local needs.(Chayes 2013)

Thus, Chayes sees rebuilding as a local organized, but internationally funded, cooperative venture that would hold the locals accountable for the resources that are provided by the international community and progress should also be reciprocally reported to the donor community. Holder, a supporter of post-conflict war trials, begins her article with the conclusory statement that “[i]t has come to be widely accepted that jus post bellum includes responsibilities to rebuild” (Holder 2013). With this sensational and, perhaps, overbroad statement, she insists the peace must prevent any new outbreaks of war or other humanitarian issues under retribution or truth commissions. Iasiello issued a call for just restoration and separately respect for the environment with a separate rebuilding component. Just restoration is the transformation to “… a functioning, stable state …” as he places the additional calls on the victors to repair or rebuild infrastructure (Iasiello 2004). In his criteria of respect for the environment, he writes “[a]ll sides in a conflict should assume responsibility for the protection of the environment in war…and the subsequent restoration of the environment after the fighting has ended” (Iasiello 2004). Chaplain Iasiello has expanded the element of rebuilding to include the environmental impacts of war (Iasiello 2004). No other scholars have gone so far as to include an environmental component into the element of rebuilding.

Lazar is a jus post bellum sceptic who announced “… just interveners, who have already taken on such a heavy burden, are entitled to expect the international community to contribute to reconstruction after they have made the first and vital steps” (Lazar 2013). Lazar adopts a principal and agent approach, that is, the interveners are the agent of the international community, the principal, and, as such “[a]ny duties they acquire through their justified intervention fall on the principal, not the agent” (Lazar 2013). Proceeding on, Lazar argues “… but even if the principal/agent logic is rejected, the duty to help the stricken society should still be universal” (Lazar 2013). Concluding, “… if one state undergoes the struggle and risk involved in just intervention, they can demand that other states that avoided the costs contribute to reconstruction” (Lazar 2013). Majima employs the term “reconstruction” as one of his putative elements by that he means rebuilding and actually uses the term “rebuilding” later in his article. He casts rebuilding to include the traditional brick and mortar, but expands into both the political and the economic arenas. Majima states that in the political arena, the American occupation provided “… encouragement of desire for individual liberties and democratic processes including freedom of religious worship …” (Majima 2013). On the economic side, the occupation documents included “… a wide distribution of income and the ownership of the means of production and trade …” (Majima 2013). With Osterdahl listing economic reconstruction as one of his principles of jus post bellum, he makes a push for “… incorporating international and national laws relating to the financial and economic sector since economic reconstruction is a very important part of the post-conflict phase” (Osterdahl 2012). Similar to Majima, the clear implication of including economic reconstruction is that such an effort should produce a more lasting peace, although empirical evidence is currently lacking other than the cases of post-World War II Germany and Japan. Osterdahl opines that the “responsibility to protect” trend “… contains elements that strongly resemble what has been discussed under the heading of jus post bellum. The responsibility to rebuild …” (Osterdahl 2012). When discussing “state rebuilding” as opposed to the brick and mortar type rebuilding, Osterdahl concludes “… the operationalization of the jus post bellum in precise legal terms is lacking for the time being” (Osterdahl 2012). The element of rebuilding is the second most often mentioned of the six jus post bellum elements, as we have observed; so the scholars clearly and convincingly indicate the importance of rebuilding as an element.

Only two scholars, Lazar and Majima, listed restitution for damages or injuries. Lazar advocates, “… that compensation should be subordinate to reconstruction …” (Lazar 2013). Judging that any of the money to be paid to individuals as restitution is not going to pay to fix the damage, rebuild the physical structures, or assist those in most want or need. Majima cites the US Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan regarding restitution, as “… it must be full and prompt …” to be effective (Majima 2013). Both of the authors look to the lasting peace in their words about restitution. Yet, having seen the need for rebuilding, it is understandable that restitution is at the bottom of our selective elements list. This might be due to the other elements being wider in scope vis-à-vis the population, whereas restitution is personal. Based on these readings, there seems to be many idiosyncratic definitions such that restitution might be lumped in with reparation element. If this is true, we might have more support for the jus post bellum element of restitution than we observe from the chart. Having seen that the scholars possibly combined the element of restitution and reparation let us turn to the latter.

In the element of reparation, the repair or other remedy for goods damaged or injuries suffered, we have an attempt to make the victim whole again; a concept borrowed from tort law (Beatty et al. 2014). Bass supports the element of reparation quite beyond the idea of state responsibility. Bass holds “… reparations offer another way of punishing those who, while perhaps not criminally guilty, bear some responsibility …” (Bass 2004) Despite this view, he cautions against harsh or exploitive reparations writing “[r]eparations should be compensatory, not vindictive” (Bass 2004). So “[i]n the same spirit, reparations are a way of showing to would–be aggressors that war literally does not pay” (Bass 2004) Bass ends by stating that there is a return to the idea of reparations “… economic reparations are an increasingly accepted means for making amends to the victimized groups” (Bass 2004). For Majima, the lens of the Potsdam Declaration provides the background for his view of reparations. In that Declaration, the economic portion stated unequivocally reparations were to be made “… through the transfer of Japanese property located outside the territories to be retained by Japan” and from “such goods or existing capital equipment and facilities as are not necessary for a peaceful Japanese economy or the supply of the occupying forces” (Majima 2013). He agreed these reparations formed part “… of the successful reconstruction …” (Majima 2013). Presenting a mainstream position, Orend argues against compensation whether that be in the form of restitution or reparation, although based in the context he appears to mean reparations. Instead, he strongly favors “… investing in and rebuilding the economy” rather than “… extracting resources from the target country …” (Orend 2007). Continuing on “[t]his need for funds is a strong argument for including international partners in reconstruction” (Orend 2007). Clearly, Orend wants several types of rebuilding to be considered as constituents of this jus post bellum element including economic rebuilding, reconstruction, and constitution rebuilding as he rejects reparations. Osterdahl lists several “elements” for his development of the jus post bellum concept; one of these is “… extracting post-conflict reparations …” (Osterdahl 2012). This fits into his view of the post-conflict rehabilitation since jus post bellum in general is “… much more comprehensive since it aims at the entire society …” (Osterdahl 2012). Transitions to peace, for him, must be a societal responsibility of both the vanquished and the victors. Stahn, while supporting the general idea of an element called reparation, is quick to cite a trend that in “[c]ontemporary developments in international law point to the emergence of a rule that prohibits the indiscriminate punishment of a people through the excessive reparations claims …” (Stahn 2006). Accordingly, victor should not be tyrannical but rather “… that reparation and compensation claims must be assessed in light of the economic potential of the wrongdoing state and its implications for the population of the targeted state” (Stahn 2006). According to Walzer “[r]eparations are surely due the victims of aggressive war” (Walzer 2015). These are to be collected via the tax system from “… among all citizens, often over a period of time extending to generations that had nothing to do with the war at all” (Walzer 2015). To him this is a price of citizenship. Acceptance of paying reparations “… says nothing about their individual responsibility.” (Walzer 2015). Simply stated, Walzer supports reparation but not the idea of a guilt being attached to the ordinary citizen.

Again, we see there is a consensus on the element of reparations with the second highest subscription rate of all of the jus post bellum elements. Yet, the definitional and practical implementation divergence exposed above shows the difficulty of operationalizing the elements of the concept. The good news is a high degree of “buy-in” from our selected scholars, but the devil will remain in agreement on the definition and extent of these reparations as these become operationalized. We have been cautioned against making reparation demands overly burdensome or even punitive while understanding that wars have reparation consequences.

Proportionality is our final element under examination. On one level of analysis, this element is a part of every author’s writings in that it is necessary for that lasting, just peace all agree upon. Applying our methodology requires more than this visceral humanitarian sentiment; so, we seek textual confirmation. “Proportionality in the fighting might be seen as applying to jus post bellum” (Bass 2004). The seeds of the post-conflict element of proportionality may indeed be sown during the waging of the war. He places proportionality into a positon to advocate against total war indicating “[t]he duty of peace must outweigh the duty of justice …” (Bass 2004). Majima clarifies this element “[u]nder this principle, any ill effect caused must be proportionate to the resulting good effects and vice versa …” and applies it to the non-prosecution case of the Emperor after World War II (Majima 2013). Majima concludes that “… using the principle of proportionality to evaluate the emperor’s exemption from indictment, the principle of retribution could be considered to be satisfied, at least in part” (Majima 2013). The element of proportionality permeates every other jus post bellum element, rendering it critical to the development and refinement of the concept. Proportionality in the jus post bellum phase is as meaningful and universal as it is in the jus in bello phase, establishing this concept as indispensable for the Just War Theory.

7. Conclusions

In the end, a few general statements can be made about the consensus regarding the elements of jus post bellum. The nearly universal subscription to retribution is a clear finding and it should become an element of jus post bellum. The current consideration of the forms retribution might take in the post conflict phase, whether trials or commissions or amnesty, would all benefit from the degree of moderation called for by Grotius and, more recently. Chaplain Iasiello. With further exploration by those reading this journal perhaps a more defined basis for and application of retribution could be modeled and eventually applied. Retribution is too important to be left only to the legal and political experts; so input from those interested in ethics and morality should be incorporated into any jus post bellum element of retribution. Similarly, the rebuilding element garnered significant support, but not as nearly universal as retribution. Likewise, those interested in the applied religion will have a large role to play in the physical and spiritual rebuilding of a defeated state. Their efforts can be seen around the world right now. Knowledge that is gained by these applied religionists and humanitarians will be useful in developing the element of rebuilding. Their practical ideas could readily be incorporated into the actual rebuilding labors of the post-conflict phase. Reconciliation for many of these scholars is wrapped into the criminal justice aspects of the post-conflict phase of war. Other scholars take a wide aperture approach, viewing the element of reconciliation broadly regarding the entirety of society. Yet again, we observe the difference that one term has for the community writing about jus post bellum. Despite all of these well-intentioned efforts to seek the element of reconciliation, only five of our scholars mentioned the element either directly or indirectly. However, this element ranks third of six among our scholars for inclusion as an element of jus post bellum. Those reading this journal can certainly contribute great ideas regarding this putative element of reconciliation, since this is part of the theologies of most religions and there is worldwide applicability for their skills. Further development of the reconciliation element will be greatly enhanced by contributions from religious scholars and practitioners.

The other elements had some range of support, but not clear or convincing evidence of support. The combination of restitution and reparations might be a solid development, but only begs the question of whether or not five elements is a good basis to proceed to develop a concept. This seems adequate, but the hard work of defining the extent of these elements could call for an additional elements being considered for a more complete concept development. Again, my view is that any comment by the readers of this journal could contribute mightily to the development, refinement, or deletion of some elements or the raising of other elements that are not currently under consideration.