Abstract

Violence is a characteristic that has somewhat become definitional for the Hindu goddess Kālī. But looking at it through the lens of folk narrative and the popular, devotion-infused and highly personalised opinions of her devotees shows that not only the understanding, but also the acceptance of this violence and the connected anger and bloodthirst that are usually attached to it, as well as the feelings of fear and danger that arise from them on the devotees’ end, are subjects open to discussion. This article, at the juncture between anthropology, performance, and Hindu studies, analyses and compares discourses about her Malayali counterpart, Bhadrakāḷi, drawing simultaneously on various versions of her founding myth of Dārikavadham (‘The Slaying of Dārikan’), ritual routines of her temples in Central Kerala as well as ritual performing arts that are conducted in some of them. The concluding discussion of her alleged thirst for blood and identification of the ’real‘ addressee of blood offerings made to her particularly illustrates how far the negotiation of Bhadrakāḷi’s use of violence and her very definition as violent goddess reaches deep into the worshipper/deity relationship that lies at the heart of popular worship.

1. Introduction

- ‘She screamed with a dreadfully loud voice in the middle of battle preparations (…)

- With both hands she angrily shook the sickle shaped sword and bowed down

- The world trembled with the kick of her holy feet

- She came to cut the head of Dārikan (…)

- [In her hands a] bowl filled with blood and a sword with horrifying blade

- She fought the head of Dārikan with a trident (…)

- Swimming in blood and wearing a garland [of skulls]

- [She is] the terrifying mother who bathes on the cremation ground with her army (…)’2

Extract of Kōyiṃpaṭanāyar’s song performed during muṭiyēṯṯu’

Noor van Brussel and I have argued that ‘there is probably not a single god in the diverse Hindu pantheon that evokes so many divergent views and ambivalent stances from devotees and researchers as Kālī does’. (Van Brussel and Pasty-Abdul Wahid 2018, p. 1). The same applies to her little Malayali sister. As full-fledged counterpart of the pan-Indian Kālī, the Malayali goddess Bhadrakāḷi incarnates all dreadful tantric inspired features as testified by the song extract from the local ritual performing art muṭiyēṯṯu’ quoted above. She is an accomplished and successful warrior armed with weapons numbering up to sixty-four. Death is her enslaved associate, the cremation ground her dwelling where she rejoices with her soldiers selected among the ranks of the evilest lower spirits, ghouls, and trespassed souls. She adorns herself with skulls and severed limbs. The horror of her imposing physical features only equals the extent of her powers, with legs described as being as large as elephant feet, her navel as profound as a dark valley, her breast as impressive as two mountains, her hair as thick and foreshadowing as dark rain clouds, her round face as unfathomable as the moon, her ears as gigantic as to frame two elephant heads, her blood-coloured mouth with protruding tongue and fangs as a profound cave—and all these features form a figure described as ‘beautiful’. The different sources from which this list of characteristics is drawn, whether it be the songs performed to a powder drawing (kaḷam) representing Bhadrakāḷi, the meditation verses (dhyāna ślōka) used to visualise her prior to the drawing or prayers used as part of her worship in Central Kerala, are as much filled with descriptions of her horrible features and deeds as they are with praises of her grace and beauty. The admixture of violence and beauty in varying proportions is standard, not only in Bhadrakāḷi’s iconography, but also in the mental picture that worshippers have about her. How violence and its trigger, anger, and beauty fit together depends on the interpretation of anger and of the violence that derives from it. The popular narratives and songs that frame her worship as well as the ritual performing arts that stage her story in different forms in this part of India unmistakably depict her as an incarnation of raw anger and violence in all its horrid dimensions. Yet anger and violence are tinted with profoundly humane traits of justice, compassion, respect, filial and motherly love in particular bhakti dominated contexts. These traits fade out the horror component inherent to violence without erasing it and divert the danger to controllable and justified targets, thereby eliminating the fear ingredient that is often mentioned as admixed to devotion in the case of this particular goddess.

Another significant aspect of local considerations of Bhadrakāḷi is that she can be violent, but does not necessarily have to be. I have already argued elsewhere that classical portraits of Kālī as invariably violent and unpredictable diverge considerably, not only from how worshippers pictured her to me, but also from how she is worshipped in individual high caste temples. In Central Kerala, the incarnation of Bhadrakāḷi differs from one temple to the next in terms of nature or ‘behavioural disposition’3, her so-called bhāva. These differences can be understood as expressions of different development stages of the deity with links to episodes of her myth and the context-specific maturity of the deity and orientation of her idol (Pasty-Abdul Wahid 2016). The bhāva pertaining to local incarnations of the deity is diagnosed by the tantri, the temple’s highest authority in ritual terms, and it is to some extent used as guidance to determine her ritual routine and the artistic components of her yearly festival. Raudra (‘angry, violent’) incarnations of Bhadrakāḷi, which are most frequently found, are so to say ‘stuck’ in the part of the myth where she is chasing and fighting her enemy, the asura Dārikan (see the myth outline in Section 2). Ghōra/ugra (‘terrible, furious’) incarnations are those stuck in the ferocious mood that even made the gods shiver as she was returning to Mount Kailāsam, holding the asura’s head in her hand, destroying everything on her rampage. These goddesses, situated at two different points on the upper side of the violence scale, are considered to be properly served with offerings that meet their needs in their particular condition. The main regular offering for them is guruti, a thick deep red liquid composed of water, turmeric powder and lime mimicking blood. Guruti can be conducted with varying intensity based on the number of vessels filled with the liquid, the mode of stirring (with accessories/bare hand), the place or item on which the liquid is poured, and the exact location for performing the offering (inside/outside the deity’s sanctum). In terms of performative and predominantly votive offerings, raudra and ghōra/ugra Bhadrakāḷis receive different treatments. In the cities and villages of Central Kerala in which I conducted fieldwork, raudra Bhadrakāḷis were considered to be best served with performances linked with the myth of Dārikavadham (‘The Slaying of Dārikan’, enemy of the gods) such as muṭiyēṯṯu’, and more specifically with the episodes narrating the tracking of, confrontation with, and combat against the asura Dārikan. These ritual performing arts are in theory4 limited to the temples devoted to violent Bhadrakāḷis, as they combine the martial themes inherent to the goddess’ portrait as asura-killer with the display of a precise level of horror and violence and explicit sacrificial logics greatly appreciated by this type of incarnation. One such temple is the Kōlaṃkuḷaṅṅarakkāvu’ Bhagavati Kṣētram located in a tiny village from the south-eastern part of Ernakulam district, in the midst of paddy fields, coconut trees and rubber plantations. It houses a goddess so ‘terribly angry’ (bhayankara dēṣyapeṭṭa) said the manager of her temple, that a pond had to be constructed facing her shrine’s entrance to cool her in case she runs out of her abode, infuriated. Her festival celebrated end of April culminates in a performance of muṭiyēṯṯu’ gathering a large crowd of worshippers, some of which have travelled long distances to be back in their hometown to attend this event. As for ghōra/ugra Bhadrakāḷis, their interest is said to lie in performative offerings displaying an extreme ferocity indexed on their tremendously heated constitution and deriving violence-related interests. The goddess of the Arayankāvu’ located on the southern border between the Ernakulam and the Kottayam districts is one of them. In her shrine, preference is given to performances of garuḍan tūkkam conducted beginning of April that enact and reactualise the bloody sacrifices of the eagle Garuḍan through a theatralised act of ritual mortification. For other ghōra/ugra Bhadrakāḷis, such as the one installed in the Arikkūḻa Mūḻikkal Bhagavati Kṣētram at the eastern end of the Ernakulam district, the ritual mortification is centred on the character of Dārikan, the asura leader who fought the clan of gods in the major cosmic war that saw the birth of the goddess. In both forms of tūkkam, the performance ends with the ritual shedding of blood from the backs of the costumed performers who are usually ritual specialists, but can also come from the ranks of the standard devotees in the case of the garuḍan tūkkam.

Yet, the raudra and ghōra/ugra Bhadrakāḷis who illustrate the usual violent to extremely ferocious portrait of the goddess only represent one side of the coin. Some temples of Central Kerala house two further types of Bhadrakāḷis that are officially diagnosed as non-violent. The first ones are said to be in śāntam (‘peaceful, calm’) bhāva, incarnating the goddess after her mission was accomplished and her anger calmed. The second ones, depicted by the words mōkṣam (‘liberation’) and vijaya śrī lalita (‘charming victorious goddess’), specifically refer to Bhadrakāḷi at the end of the myth, after her father sent her to earth to receive blessings in exchange for her accomplished mission. In these shrines, the goddess is considered unfit to receive the offerings categorised as ‘violent’, i.e., guruti in all its forms and performing arts staging and reactualising the violence inherent to her myth. In the Panakkal temple (south-west district of Ernakulam) for instance, a ‘very pleasing and silent’5 Bhadrakāḷi said to bestow blessings on everyone approaching her is worshipped with different types of milk puddings (pāyasam), pastries and sweets. These calm goddesses are a perfect illustration of the juxtaposition of gentle/beautiful and horrifying features referred to earlier. Visiting the temple of Tirumāndāmkunnu (Mallapuram district) housing a śāntam Bhadrakāḷi that plays a major role in the goddess landscape of Kerala, Sarah Caldwell wrote ‘[w]e were struck, however, by the not-so-gentle looking images of the goddess which decorated the temple’ (1999, p. 126), referring to the fangs, multiple weapons and blood smeared asura head with which she is portrayed regardless of her peaceful constitution. Now, the temples housing such unusually placid Bhadrakāḷis represent a minority in the devotional landscape of Kerala. Nevertheless, their very existence suffices to deconstruct the all-pervasive and unilateral portrait of this goddess picturing her as fundamentally violent, angry, and according to some sources, ambivalent, if not malevolent. My purpose here is not to show that this portrait is irrelevant. It is to demonstrate that the issue is far more complex and nuanced once popular practices in localised areas are given as much importance as official and orthodox narratives and ritual routines, and once worshippers are given the floor to express their own personal opinions.

With her varying and multiple moods, Bhadrakāḷi might seem to resemble those goddesses such as her Tamil neighbour Māriyamman (see Beck 1969) or the Singhalese Pattiṇi (see Obeyesekere 1984) who have been pictured as ‘ambivalent’, ‘multipolar’, ‘dualistically split’ and even ‘schizophrenic’ due to the apparently contradicting tendencies they display. I however agree with the scholars (e.g., Assayag 1992b; Erndl 1993; Sax 1992, 1994) who criticised this polarising analysis for its lack of representativeness with regards to the conceptualization of the goddess by those who serve and worship her. As already argued in another article (Pasty-Abdul Wahid 2016), seeing the simultaneity of anger and serenity within a same entity as contradictory translates an exogenous mindset that ignores the fact that variety, malleability and multiplicity are intrinsic features of ‘the Hindu goddess theology—simultaneously one and several, undivided and divided’ (Bouillier and Toffin 1992, p. 18). Furthermore, the contradiction vanishes once the goddess is seen from an expanded view displaying the individual incarnations in a distinct manner: each incarnation of Bhadrakāḷi in a given temple has a specific and permanent bhāva6 that can be different from the incarnation next door; the gathering and ordering principle is her narrative, the myth of Dārikavadham, that draws all strings together by linking every individual bhāva with an episode of her founding story that triggered a particular reaction of hers. Bhadrakāḷi is therefore an eloquent example of the simultaneity of unity and multiplicity of the Hindu goddess—there are many Bhadrakāḷis, but they are all Bhadrakāḷi.

My ethnology oriented research has been focusing on the ritual performing art muṭiyēṯṯu’ for close to two decades. Its performances are conducted in the outer compound of some Bhadrakāḷi temples of the districts of Trichur, Ernakulam and Kottayam in Central Kerala, usually at the time of festivals. It is the monopoly of four families from the intermediary castes of temple servants (mārār and kuṟuppu’) in charge of the musical and pictorial service in Brahmin temples. The performance, a single storied dramatic event usually sponsored and presented as votive offering to the goddess, unfolds with the musical accompaniment of a drum orchestra and involves dancing, singing and acting out of parts of the myth of Dārikavadham. It includes seven characters dressed in colourful costumes with wooden headgears and complex makeup: goddess Bhadrakāḷi (the only character involving possession, see Figure 1), her asura opponent Dārikan and his twin brother Dānavēndran, the god Śiva who fathers Bhadrakāḷi and sends her to war, sage Nāradan who acts as intermediary between the humans and Śiva, Kōyiṃpaṭanāyar, the soldier leading Bhadrakāḷi’s army, and the comical bhūtan Kūḷi representing the multitude of evil spirits fighting alongside the goddess7. Researching the broader context of this ritual art had me gather first-hand information about the goddess using ethnographic tools from the people in charge of performing muṭiyēṯṯu’ and those gravitating around them, i.e., predominantly male, middle to high caste temple officiants and administrators as well as regular worshippers (mainly educated men, women and youngsters from middle castes) of the temples where muṭiyēṯṯu’ is performed once every year. This data show that the gap between the conventional, ritual and textual descriptions of Bhadrakāḷi’s physical features and deeds in literate and popular spheres, and her bhakti inspired descriptions and, most importantly, the interpretation of these features and deeds by those who pray to her, is sometimes quite deep. Violence appears in a different light when it passes through devotional filters. Religious canons and neat black and white classifications can easily be blown away by individual devotion and personal views. As such, Bhadrakāḷi’s depictions by her worshippers translate the extreme variability that is inherent to popular Hindu worship as it is practiced in the innumerable tiny goddess shrines of South India. This article is therefore about Hinduism as it is practiced in the hearts of individual men and women, with all the variety, discrepancies and fuzziness pertaining to the human experience and psyche. The conclusions are therefore entirely limited to this peculiar framework and to the context of those few high-caste Bhadrakāḷi temples of Central Kerala that treat their goddess with a yearly performance of muṭiyēṯṯu’. My purpose here is also not to theorise about popular goddess worship, but to present some circumscribed and contextualised expressions of it and show how it is translated in the reasoning and words of those who practice it.

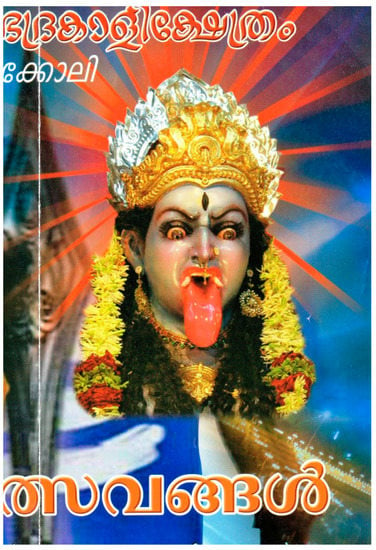

Figure 1.

Bhadrakāḷi in muṭiyēṯṯu’ (Photo by Punnackal Girijan Narayanan Marar).

In order to underline the different layers and heterogeneity of discourse pertaining to the description of Bhadrakāḷi with focus on her use of violence, her anger, the terror she creates and inspires, and the blood she is supposed to crave and consume in large amounts, I will point out the specificities of this description in different sources that are interlinked in Bhadrakāḷi’s daily worship in my given area and context of study: several versions of the myth of Dārikavadham, the popular narrative that prevails in her liturgy and frames her cult in Kerala; songs and ritual performing arts conducted during this cult; and personal opinions expressed by informants, most of them being worshippers and officiants from those temples as well as performers of muṭiyēṯṯu’. But before I dig into the matter of my subject drawing from these sources, I would like to provide some background information about them and outline the specificities of my approach.

2. Which Referential?

A picture of the goddess that her standard devotees would be able to confirm and identify with is a picture that is based on and includes the various frames of reference that fill their visual, sonic and emotional field: devotional posters, comics, movies and TV shows drawing on Hindu narratives, devotional books, prayers used at home or at the attended temple, paintings on temple walls, icons prayed at when the sanctum doors open, local mythologies from specific temples, stories of personal deity/devotee ‘encounters’ told around houses and temples, and art forms (songs, dances, theatrical plays), usually ritual in nature, that are centred on a selection of episodes of the goddess’ myth and staged during temple festivals. As detailed elsewhere, the way the devotees encountered during fieldwork represent Bhadrakāḷi is a combination of (1) a commonly shared picture largely influenced by local popular and institutional iconography (posters, paintings, idols, etc.) and mythology; (2) a more particularised picture attached to a specific divine incarnation in a given temple with the iconography, religious routine and stories peculiar to her, and (3) a very personalised picture infused with private experiences and inclinations. For the people who conduct, attend or sponsor performances of muṭiyēṯṯu’, representations of the goddess, and by extension their interpretation of her use of violence and gory deeds, particularly converge with the second and third level.

As part of my fieldwork, I tried to identify the so-called ‘stories’ that constitute the religious referential of the people gravitating around Bhadrakāḷi temples, either as worshippers or as members of the temple staff (regular high caste officiants, middle caste temple servants and intermittent middle caste ritual experts). What I mean by ‘stories’ are those narratives ranging from official and often regionally shared myths to local stories linked with specific temples. These stories deeply imprint the minds of men, women and children and frame how they understand and interpret anything pertaining to the goddess. To my generic question ‘Which religious stories do you know?’ (without specifically mentioning the goddess), informants generally mentioned: the Adḍyātma Rāmāyaṇa8, a version of the myth of Dārikavadham (Bhadrakāḷi’s Gest or, more contemporary to us, her ‘biography’) often with particularised details pertaining to a specific temple, and ‘small stories’ and legends linked with specific temples. None of my informants, even muṭiyēṯṯukars (performers of muṭiyēṯṯu’) who traditionally work as temple servants in Brahmin temples, has spoken about the great pan-Indian texts, whether it be the Devī Māhātmyam or the Liṅga Purāṇa that are by default mentioned in Indian studies as constituting the main reference for the goddess, or even the Bhadrakālīmāhātmya, a Malayali purāṇa9. I was a bit puzzled by this fact, so I rephrased my question (in Malayalam) to ‘Do you know any purāṇa?’. Here is one typical answer I received from a muṭiyēṯṯukar:

Purāṇa? There are so many here, you have the Yakṣipurāṇam [myth of the female evil spirit Yakṣi], the purāṇam of Kīḻkāvu’ Bhadrakāḷi [goddess of the lower temple in Chottanikkara](…). You have to note them all down, they are all important for our Dēvi.10

Such answers not only show that the classical orthodox texts are absent from the religious frame of reference of worshippers in my field of study (compare with Foulston 2003), but also that the word purāṇa, a beloved keyword for scholars of Hindu literature and religion, echoes to nothing more than the vague meaning of ‘legend’ or ‘old story’ in Malayalam. The myth of Dārikavadham in all its variety, particularizations and dynamics intertwined in the devotional routine of temples and worshippers, is the basic framework inside which individual imagination depicts the personality of the goddess in peculiar ways. For those literate men, women and children who gravitate around the Bhadrakāḷi temples, and among whom most do not speak Sanskrit and are no ritual specialists, this is the main ‘story’, the referential narrative to imagine the goddess and interpret her deeds. Scholars of Indian studies tend to apprehend the Sanskrit purāṇas as main source for the goddess mythology, and to see local mythologies as versions, adaptations and popularizations of these purāṇas11. The myth of Dārikavadham is not different: scholars have highlighted its interconnection, even for some of its kinship link with different purāṇas, primarily the Devī Māhātmyam12, from the point of view of content (e.g., Freeman 1991; Caldwell 1999, p. 19; Aubert 2004, p. 71; Van Brussel 2016) and religious ‘power’ of the text (e.g., Tarabout 1986, p. 122). Yet, differences between the myth and its alleged orthodox models are significant, such as the fact that Kāḷi is Śiva’s daughter and not his consort as in the purāṇas, which has important implications for interpreting her actions and interaction with other members of the pantheon. I therefore find it more pertinent and fruitful to look at the myth of Dārikavadham as an independent corpus fundamentally Malayali in its form, content and powers; as a dynamic and fluid tradition with both, textual and non-textual dimensions. I believe that this stance, which has also been chosen by inspirational scholars such as Alf Hiltebeitel (1988); Blackburn and Flueckiger (1989); A. K. Ramanujan (1991); Paula Richman (2001) and William Sax (2002) for the study of Hindu narratives in other parts of India, helps demonstrate the entire magnitude of the myth and its ramifications within local society, culture and religion with much more clarity.

This is the version of the myth that is known to muṭiyēṯṯu’ performers:

During the war opposing the asuras (enemies of gods) to the dēvas (gods), the asuras were nearly exterminated. Only two women escaped: Dārumati and Dānapati. The women undertook extreme penance in order to force Brahma to grant them sons. Soon, Dārikan, son of Dārumati, and Dānavēndran, son of Dānapati, were born. The day Dārikan heard from his mother about the terrible defeat suffered by his clan at the hands of the dēvas, he also chose to undergo severe penance to attract Brahma’s attention. When the god showed himself to him, Dārikan requested Brahma to grant him superhuman powers, and so he received a strength equal to ten thousand elephants as well as the power to create ten thousand warriors from each drop of his blood falling on the ground. He was also entrusted with two mantras with which his wife, Manōdari, would be able to bring him back to life. Brahma however warned him that his powers would decrease if a third person came to know the mantras. Finally, the god gave Dārikan a boon to protect him from the attacks of women, but the bold asura rejected the boon, saying he did not fear women. Brahma was so stunned by the asura’s arrogance that he cursed Dārikan to be defeated by a woman of divine descent. Trusting his new powers, the unwavering asura went to war against all living beings, equally tormenting the gods, sages and humans. His victims sought assistance from sage Nāradan and asked him to inform Śiva, sitting on Mount Kailāsam, about their suffering and beg him for help. Śiva was moved to anger upon hearing Dārikan’s misdeeds listed by Nāradan. His third eye opened revealing a blazing fire from which a mighty being emerged: his daughter, Bhadrakāḷi. Śiva entrusted her with the mission of killing the asura. Supported by a horde of bhūtas, prētas and piśācas (ghosts and malevolent spirits), the goddess immediately left the divine abode, heading towards Dārikan’s fortress. On the way, she met Vētāḷam, a female vampire, who accepted to serve as her mount in exchange for the promise to receive enough blood to quench her thirst. Soon both armies met on the battlefield. The goddess and her army were rapidly overpowered as the asura kept multiplying himself each time his blood was shed. Kārtyāyanidēvi (a form of Śiva’s consort) then took the form of a poor Brahmin girl and paid a visit to Manōdari, Dārikan’s wife, whom she tricked and convinced to reveal the secret mantras. At this precise moment, Dārikan’s powers suffered a significant blow. Bhadrakāḷi seized this sudden weakness to behead him, while Vētāḷam stretched out her immense tongue over the battlefield to intercept the drops of blood before they could reach the ground. Brandishing Dārikan’s head, the goddess then headed back to Mount Kailāsam to place the trophy in front of her father. But even after completing her mission, Bhadrakāḷi’s anger could not subside. Her infuriated condition was terrifying the gods, including Śiva, who requested his sons, Subrahmaṇyam13 and Gaṇapati to take the form of infants and lie down in the path of the goddess. As Bhadrakāḷi saw them, lying helplessly on the floor, she became overwhelmed by motherly love. She took the children in her arms and breastfed them. Her anger then vanished. She finally reached Śiva’s abode and presented him with Dārikan’s head. However, thinking that Bhadrakāḷi would upstage him if she stayed at his side in Mount Kailāsam, Śiva ordered his daughter to leave for earth with the promise that humans would worship her in remembrance of her mighty deeds.

This myth is meditated, narrated, recited, chanted, sung, drawn and enacted in each and every temple of Bhadrakāḷi from this area. It is found in printed forms (booklets are sold around temples during festivals), but its transmission between generations of temple workers and propagation among devotees primarily follows the oral line. The myth exists in many forms and variations from one end of Kerala to the other. Its general outline remains the same, but important variations exist at the level of identity, description and actions of the characters, selection of episodes, language and narrative style, and type of usage of the myth (standing alone or associated with other narratives). It is heard, seen and known at all levels of the Malayali society, but in different ‘folk’ and ‘sanskritised’ versions14, the former being linked with specific communities and delimited social and geographical contexts. This broad variety reveals the local preponderance of the myth, ‘for only a story of extraordinary cultural importance would be performed in so many ways’ (Blackburn and Flueckiger 1989, p. 9). The myth of Dārikavadham is primarily connected with the cult of the goddess, however because of the homogeneous distribution of her sanctuaries and their numerical predominance throughout the state, the myth is a genuine Malayali canonical text15. Moreover, the fact that the myth is also central to numerous ritual performing arts staged in Bhadrakāḷi temples in front of audiences composed of Hindus and non-Hindus, also contributes to the omnipresence of the story of the goddess in and around her temples, as well as in the collective imagination of Malayalis.

3. Approaching the Goddess via Ritual Theatre

I have found that studying popular Hinduism through the prism of ritual theatre, in particular muṭiyēṯṯu’, is a fascinating method to address the unmediated deity/worshipper relationship that is at the heart of popular religion; and here, the pivotal elements are the votive offerings which, in the temples where I conducted fieldwork, quite frequently consist of performances of ritual theatres. Closer to my point in this article, such an approach also opens new ways for analysing the active and ongoing formulation and negotiation of the goddess’ personality by those who pray to her. Here is why.

Muṭiyēṯṯu’ is a ritual art conducted only once a year, but for generations, in a range of temples with which families of performers have hereditary agreements. Worshippers in these temples are not only accustomed to seeing performances of muṭiyēṯṯu’ since their childhood, but they also explain that they have an emotional bond to them and anticipate the next performance with much excitement. Muṭiyēṯṯu’ stages and re-enacts the most violent portions of the myth of Dārikavadham, i.e., the sections corresponding to the fight and beheading of the asura. It involves an active participation by the male public (children, teenagers and adults), who run, jump and scream around the performers embodying the mythical characters, in particular Bhadrakāḷi and the asura Dārikan. The goddess is here physically incarnated through the body of a possessed performer wearing a complex costume, elaborate makeup and heavy wooden headgear said to be the main vector for possession. Here, Bhadrakāḷi is considered to be present in the flesh in order to re-actualise her mighty deed in front of her worshippers who actively accompany her, boosting her with their screams and actions. At the end of the performance, Bhadrakāḷi distributes her blessing to each individual present in the temple precincts, especially young children. Worshippers travel from distant places to be back in their native place to attend this particular sequence. In those often tiny temples, such as the one of Kōlaṃkuḷaṅṅarakkāvu’ already mentioned above, muṭiyēṯṯu’ is the most valued offering to Bhadrakāḷi. It is considered to be the most efficient to receive her help and the most powerful to respond to her endless desire to see herself re-actualise the fight against the mighty asura that made her into what she is worshipped for. Muṭiyēṯṯu’ is yearly sponsored by local families or individuals who select it as vaḻipāṭu’ (‘votive offering’). I have explained (Pasty 2010, chp. 6, Pasty-Abdul Wahid 2017b) that the relationship established between the devotee and the deity in the context of a vaḻipāṭu’ muṭiyēṯṯu’ (a muṭiyēṯṯu’ offered as vaḻipāṭu’) allows both parties to meet and fulfil each other’s needs and desires: the goddess sees a performance of muṭiyēṯṯu’ and receives adequate worship, and the devotee has worldly wishes fulfilled, most typically finding a good husband for a daughter, ensuring a good job for a son, a pregnancy, etc. The vaḻipāṭu’ muṭiyēṯṯu’ is therefore inscribed in a ‘relationship of mutual exchange’16 and is consistent with the special relationship of mutual care, affection, respect and trust between the devotee and the deity that informants told me about. The yearly performance of muṭiyēṯṯu’ in a given temple is said to be the religious event a worshipper should not miss. Bhadrakāḷi’s power is at its peak on that day and she is present in the flesh to bestow blessings from her own hands. Muṭiyēṯṯu’, so to say, seals the bond between goddess and worshipper and lets it culminate in a power infused personal encounter that reconfirms and exacerbates the key components of this bidirectional devotee/goddess relationship: mutual benefits, child/mother love, respect and trust. Muṭiyēṯṯu’, in particular when viewed through the lens of votive offering and from the angle of the interpersonal goddess/worshipper relationship it entails, is therefore at the juncture between the abstract narrative and mythological realm, the regulated and codified ritual worship at the temple, and the day to day lives of worshippers with their down-to-earth preoccupations. It grounds the myth and liturgy of the goddess in the reality and practicality of life and serves as point of entry and exchange between the human and the divine spheres.

Talking over the years with performers and worshippers regularly attending performances of muṭiyēṯṯu’ made me understand that the mental representation and understanding of Bhadrakāḷi by those two groups is to a great extent shaped by the aesthetics, content and modalities of performances of muṭiyēṯṯu’. These performances seem to delimit a space and time in which special rules and realities apply that are specifically relevant to these active participants, but also seem to go beyond this frame. Evidence of this is notably the social status of muṭiyēṯṯukars: they are temple servants with a secondary and instrumental role in the goddess worship as per their official ‘professional description’, but they also directly ‘manipulate’ the goddess by invoking, presenting and embodying her in the context of muṭiyēṯṯu’ (Pasty 2010, chp. 2). In the same vein, I have heard on many occasions informants using items pertaining to muṭiyēṯṯu’ to explain things external to the performance as discussed below.

4. Violence in a Nearly Fully Controlled Frame: The Mythological and Narrative Background of Bhadrakāḷi Worship and Its Theological Implications

In her study about the Tamil goddess Aṇkālaparamēcuvari, Evelyne Meyer wrote that the devotee’s perception of a deity ‘is a complex whole, made up of fluid images superimposed on a nameless divine power. These images may be sharply delineated and marked by his knowledge about the goddess’ myths’ (Meyer 1986, p. iv). The myth of Dārikavadham, and by extension its many usages in devotional artistic forms, personalise Bhadrakāḷi by giving her particular character traits and by placing her within a network of relationship (with other human and divine characters) that specify her position in relation to the social and religious universe of the devotee. ‘What the history of the goddess then shows us is how the devotee thinks, what his concepts of time and space are, how he perceives the goddess in general and in relation to himself in particular’ (ibid: 1). The following is a depiction of Bhadrakāḷi drawing on the information provided in several either purely narrative or performative versions of the myth of Dārikavadham. Every version of the myth has its own individuality in both narrative and human terms. Yet they all share an underlying unity revealed through a coherent portrait of the goddess that is to some extent consistent with the bhakti imprinted descriptions of Bhadrakāḷi collected among her devotees and with specificities of her cult.

To start with, the many versions of the myth of Dārikavadham describe Bhadrakāḷi as daughter of Śiva, born from the fire of his third eye. She is also the daughter of the god’s consort, Kārtyāyanidēvi or Pārvati. Depending on the variant, she is the product of Śiva’s śakti (active power) and caitanyam (consciousness) or the product of the mix of the Trimūrtti’s (Brahma-Viṣṇu-Mahēśvaran/Śiva) śakti, each god giving her one or two of his weapons. The birth of the goddess is always the consequence of the wrath triggered by the misdeeds of the asura Dārikan. The pan-Indian paradigm of Kāḷi’s identity is therefore only partially relevant here: she is the personification of a deity’s anger, here Śiva’s17, but she is the god’s daughter instead of being his wife. This fact is significant, as it annuls the typically tantric sexually connoted Śiva/Bhadrakāḷi relationship that is so eagerly underscored in Hindu studies. The fact that Hindu worship in Kerala is largely based on right-hand Tantrism (dakṣīṇamārga) largely partakes in this specificity18.

The goddess of the myth of Dārikavadham is more precisely described as her father’s beloved daughter.

[Śiva talking to his daughter:] ‘Six women have been created, but you, the seventh, you are the beauty causing my happiness, my darling daughter (…)’.

This affection is exacerbated in the brāhmaṇi pāṭṭu’21, a corpus of songs performed by a group of Brahmin women on various occasions, such as births and weddings, as well as for the daily worship in some goddess temples. In these songs, Śiva is said to be concerned about the way Bhadrakāḷi, here described as loving and obedient daughter, dresses (Caldwell 2001, p. 108). Many versions of the myth underline the fact that Bhadrakāḷi is a daughter respecting paternal authority with a mix of filial love and subservience to her father cum master. She accepts the mission commanded by her father and pledges to appear before him only once her mission is accomplished. In various versions, she is said to bow down in front of him and to request his blessing before leaving for combat. Once the asura is dead, she returns to her father’s abode to offer him the enemy’s head in exchange for Śiva’s renewed blessing. Her deeds are therefore always placed within the frame of Śiva’s divine authority whose blessing not only sanctions and legitimises, but also sanctifies every act of violence she will be engaging in.

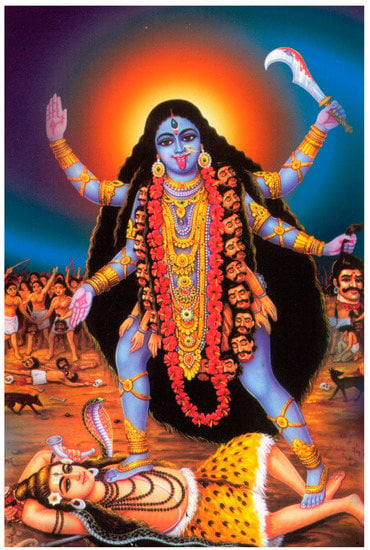

The goddess’ respect for her father is also highlighted by the shame she experiences in certain instances, such as when she sees her father naked (as in the narrative serving as basis for performances of bhadrakāḷi tiyyāṭṭu’22), when she is aware that he has seen her naked, or when she unwillingly touches him in a disrespectful way. This last situation was the explanation I received by informants when I asked them why Bhadrakāḷi is lolling her tongue in iconography (see Figure 2). While she was returning to Mount Kailāsam after killing her enemy, at the peak of her fury, Śiva had the idea of lying down on the ground with the hope that she would be appeased by seeing him so defenceless. Yet she did not notice him and accidentally hit him with the tip of her foot. Filled with shame, she stuck out her tongue in abashment and guilt—in Kerala, touching a person with one’s foot is an offense for both Hindus and non-Hindus. Here again, the interpretation of this almost definitional item of Bhadrakāḷi’s iconography, her lolling tongue, stands against left-handed tantric readings equating the lolling tongue with power, delight of the forbidden and sexual ecstasy. Scholars (e.g., Menon and Schweder 2001; Foulston 2003) have underscored the link between adherence to a specific religious strand with its connected vision of the goddess and interpretations of the goddess’ lolling tongue: while for defenders and practitioners of the tantric strand (primarily temple priests and officiants) the tongue signals the absolute power and domination of the goddess over her husband as well as sexual pleasure, the bhakti infused explanations from devotees declare that the goddess stretches out her tongue to express shame23. Interestingly, in my case, both ritual specialists and worshippers were standing on the same side, univocally reacting with outrage when I mentioned the sexual interpretations, as if they were defending a family member against dishonourable allegations. This reaction indicates that the goddess is inscribed within a human scheme in which a form of justice as well as family and social values circumscribe the divine power. Here, the goddess’ extreme anger, seen as manifestation of her maximal power, is primarily oriented towards the enemies of the gods. This anger is then said to be overpassed by the shameful feeling of a daughter having been disrespectful towards her father (which is explicit in some versions of the myth). In the context of muṭiyēṯṯu’, the lolling tongue, which is a characteristic theatrical action for both the goddess and her asura enemy, is primarily interpreted as manifestation of anger, but I have not heard any informant using this interpretation for the general iconography of the goddess.

Figure 2.

Detail from a festival leaflet (Bhadrakāḷi temple of Idakkoli, Kottayam district).

The importance given to social values in Bhadrakāḷi’s characterization through her myth is also emphasised by the anxiety that overwhelms her at the moment of killing the asura. This capacity to show humanity and compassion for an enemy gives her an honourable face, since she recognises Dārikan as a valorous warrior and a devotee to be respected as such.

[Bhadrakāḷi to Nandimahākāḷan (Śiva’s vehicle):] ‘It would not be right to kill this asura! One cannot kill those who are already defeated. One cannot kill those who have knowledge. One cannot kill those who have undergone penance for devotional purposes. I cannot kill those who have been wounded in battle’. Nandimahākāḷan replied: ‘You should not hesitate to act with such great an enemy, you must kill him with all your wrath!’(Extract from a Pāna tōṯṯam, (Achyuta Menon 1943, II: 38))

‘He is as a guru and so I cannot kill him. We should not kill those who have knowledge’.(Extract from a Dārikavadham, (Achyuta Menon 1943, II: 115))

The power and the divine mission of Bhadrakāḷi are here again subordinated to values: mercy for those who are weak and who beg, sense of honour forcing her to recognise the valour and refuse to kill her defeated opponent, and respect for knowledgeable people and the religious hierarchy dominated by ascetics (for Dārikan gained his powers through penance).

Then, some versions of the myth of Dārikavadham describe Bhadrakāḷi as a mother, not in the sense of procreation, but in the sense of motherly affection and protection with regards to her devotees. Her description as mother is also paramount in her devotees’ discourses, which is probably also why sexual interpretations seem to be entirely absent from her cult, as this would ‘violate the incest taboo’ (Erndl 1993, p. 159). The word ‘mother’ (amma) is recurring in many of the consulted sources and is used by different characters of the myth, especially in praises. Here for instance from Kōyiṃpaṭanāyar (general of her army) in muṭiyēṯṯu’:

‘My mother (amma), bless us for a long time (…). Sitting in the shrine (kāvu’), you tremble to kill well. Oh mother who resides in the temple, bowl and sword with the horrifying blade [are in your hands]. (…) When darkness comes may you give boons (varam), Oh! Mother kurumpataṃpurāṭṭi. (…) May she be praised, the one [who] cut [the head], the mother who rules over the shrine of Kodungallur.’(Extract of Kōyiṃpaṭanāyar‘s dialogue, Kunnayckal family, translation from (Choondal 1981, p. 142))

The importance of the maternal feeling is also highlighted in certain versions of the end of the myth. As Bhadrakāḷi returns from the battlefield, holding the asura’s head, her anger is said to blur her reason. She destroys everything on her way and is about to meet with Śiva, who is terrified at the prospect of facing her in this condition. Understanding that filial affection will not be enough to control his daughter’s anger, the god calls on her maternal feelings by sending her two young children she immediately takes in her arms and nurses. Here, the divine nature and unleashed raw power of the goddess, that have temporarily altered her portrait as loving and respectful daughter, are being contained by the force of maternal love. For most of the devotees I was able to speak to in the field, it is this maternal love that dominates Bhadrakāḷi’s actions towards them as well as their feeling of trust towards her.

A further key element of characterization of the goddess in the myth of Dārikavadham is her warrior nature. The very raison d’être of Bhadrakāḷi is martial: she was created in the context of a cosmic war, in which she was the only one who could lead the gods’ clan to victory. As a response to Dārikan’s arrogance, Brahma cast a curse on him that would bring death from the only source he was not watching out for: women. The seven women (Saptamātṛkkaḷ) initially sent to war against him failed. Bhadrakāḷi was thus the last possible resource concentrating all hopes and gifted with the necessary powers to compete with and finally defeat Dārikan. In some versions of the myth, she is created from the śakti of three gods and granted their respective martial strength via their weapons: Śiva gave her his trident (śūla) and Viṣṇu his discus (cakra) and conch (śaṃkhu’). This makes her a concentrate of divine power dedicated to a unique mission: destroy the asura and put an end to the suffering of gods and men.

[Right after her creation, Kāḷi asks Śiva:] ‘Father, why don’t you take all this wind and sunrise into you? Why don’t you swallow everything that is visible, and why don’t you drink up the oceans?’. Śiva replied ‘I didn’t create you for any of these things. I created you for a purpose: Dāruka and his asura forces are terrifying the world and you have to get ready to fight against him’.(Extract from a Dārukan tōṯṯam, (Achyuta Menon 1943, II: 61))

Bhadrakāḷi called her father ‘Oh supreme, give me some work! You are capable of everything! (…) Entrust me with the task I was born for! I only have one wish in my life which is to kill him when I get to meet him, then only I will return’(Extract from a Dārikavadham, (Achyuta Menon 1943, II: 97–99)).

Some versions describe in much detail how Bhadrakāḷi prepares for and accomplishes her mission as chief of her army.

Getting ready for combat, Bhadrakāḷi asked ‘Does he [Dāruka] have weapons and soldiers?’. Śiva replied: ‘Yes!’. ‘Then first give me soldiers!’ she said, and hundreds of thousands of divine soldiers were created. ‘Give me weapons!’ she then requested, and kuntam (spear), kiḻakkiṭa (?), īṯṯavāl (sord), diṇḍi (music instruments), bhiṇḍi (blowpipe), irunpulakka (metal weapon), paḷḷivāḷ (sword), triśūlam (trident), etc., in total sixteen weapons were given to her. She then requested a vehicle and Vētāḷam was given to her. (…) ‘How many yōjana (distance unit) are there between here and the fort of Dāruka?’ she asked, and ‘700 yōjana’ was the reply. ‘Then it is necessary to post as many soldiers as needed to stand on the way from here to Dāruka’s fort’. So Śiva slapped his left thigh and out of it emerged as many piśāca soldiers as would flies during a new rain.(Extract from a Dārikavadham, (Achyuta Menon 1943, II: 98))

Bhadrakāḷi commanded ‘Attack! Destroy!’, and elephants fought with elephants, chariots with chariots, swords with swords (…).(Extract from a Pāna tōṯṯam, (Achyuta Menon 1943, II: 33))

The texts also describe how she swore to see her father only after completing her mission:

Bhadrakāḷi said ‘When my eyes will see Dāruka, I will kill him and will only return to Mount kailāsam with his head’. Śiva asked her ‘Why don’t you go circumambulate Kailāsam to receive blessing?’. Bhadrakāḷi shouted so loud that the leaves fell from the trees, and she replied ‘I will not circumambulate Kailāsam, I will only do it with Dāruka’s head’.(Extract from a Pāna tōṯṯam, (Achyuta Menon 1943, II: 99)).

Furthermore she refuses to give up combat, even when the fight seems vain:

Kārtyāyanidēvi appeared on the battlefield to see her daughter’s combat. She asked her to retreat ‘Come my daughter! How can you kill such a cruel asura?’. But she replied ‘I will not give up the fight’. Kārtyāyanidēvi then said ‘Listen to me, my daughter! Bhadrakāḷi! His lady knows two brahmōpadēśa (mantra). And with those we would know the secret way of killing him! You should get hold of these brahmōpadēśa!’. She added ‘If you want, I can go to her house and get this information for you!’. Hearing this, Bhadrakāḷi burst into anger: ‘I will continue fighting Dāruka and I will kill him that way. I will therefore not go to his abode’.(Extract from a Pāna tōṯṯam, (Achyuta Menon 1943, II: 29))

The closing song of muṭiyēṯṯu’ finally describes how, once the mission accomplished, the goddess is congratulated by her father, the one whose order she diligently obeyed by causing violence and shedding blood.

- How good what you have done today

- The death of the wrestler asura is good

- The present [the asura’s head] given is good

- Success (venni), strength (balam) and fame (kīrtti)

- Be for you my daughter Kāḷi

(Extract from the closing song of muṭiyēṯṯu’, Pazhoor family)

The different versions of the myth of Dārikavadham depict Bhadrakāḷi as a warrior goddess whose only occupation is to put her strength and god given gifts to the service of the endangered human and divine worlds, and to become their champion. They depict her as a protective goddess whose efficiency and commitment to her task are testified by her relentless combat against Dārikan; as an almighty power-infused goddess whose strength and the very manifestation of her power, anger, are up to a certain level channelled by her mission and specifically oriented towards her enemy. But the different versions also show that her anger can potentially overwhelm the goddess and make her lose control, a situation in which she does turn against her own kin, indiscriminately destroying good and bad. The mythical corpus therefore does suggest that there is an ambivalent side to Bhadrakāḷi’s divine portrait. The myth however mitigates this negative trait by arguing that her potentially threatening anger is quickly controlled by the feelings emanating from the social position and relationships to which the myth ascribes her—the shame arising from her daughter role or the affection and protective feeling arising from her mother role—thereby adding an additional ‘security lock’ to Bhadrakāḷi’s violence.

There is thus a pivotal moment in the mythical corpus that calls into question the idea that Bhadrakāḷi’s ability to cause harm is exclusively and trustfully guided by her dedication to a positive cause beyond herself or governed by her unbending sense of justice and protection. This breach in the ethics of the goddess’ violence is also transcribed in the performative field, for instance in muṭiyēṯṯu’. It is a common feature for the performer incarnating Bhadrakāḷi in muṭiyēṯṯu’ to have the wooden headgear (acting as vector of possession) taken off his head at the peak of the re-enactment of the fight with Dārikan. The reason invoked is that possession by the goddess becomes too strong at this moment and might slide towards loss of control resulting in potential harm to living human beings. Parts of the small stories that are told around temples in which muṭiyēṯṯu’ has been conducted for generations indeed tell of dramatic events in which the person incarnating Bhadrakāḷi killed the performer playing the role of her mythical enemy after losing control. However, my informants had various explanations for these puzzling events, some of which insisted on blaming the human instead of the deity. Popular attitudes towards the goddess I could gather among worshippers and people regularly or sporadically working at her temples were most often devoid of any allusion to the fact that the deity’s inherent tendency to violence could potentially ‘backfire’.

5. ‘A raudra Costume But Loving Mind’: Violence Minus Fear

Sarah Caldwell wrote in her book Oh, terrifying mother. Sexuality, Violence and Worship of the Goddess Kāli (1999) that devotion to the goddess of most Malayalis is motivated by fear.

Nobody worships Kali out of love or devotion but either out of (1) fear and respect and to deflect her wrath; or (2) to obtain evil powers to harm others. (…) [S]he is more feared by most people than she is loved.(Caldwell 1999, p. 267)

Applying this idea to performances of muṭiyēṯṯu’, she described the goddess as something resembling an unruly bull:

People won’t wear a red-coloured costume or shirt [to attend a performance of muṭiyēṯṯu’] because they are afraid that Kāḷi will be attracted by that colour and she will rush towards them. (…) No one knows what Dēvī will do. [She] may attack, so they are afraid. Nobody likes to attract the special attention of Dēvī.(Caldwell 1999, p. 72)

Considering Bhadrakāḷi’s ferocious features and use of violence, and informed by Sarah Caldwell’s work, I asked a variety of informants connected with muṭiyēṯṯu’ whether they were afraid of Bhadrakāḷi in general and more specifically during performances. The answers I received underscored a different mindset.

Me: Are people afraid of Bhadrakāḷi during muṭiyēṯṯu’?A muṭiyēṯṯukar: No! They are not at all afraid! They run with Kāḷi! Only little kids are a little afraid because she looks frightening.24The wife of this muṭiyēṯṯukar:Dēvi [generic word for goddess] fights against asuras and bad people, she protects us from them. She is amma (mother). Her anger (kōpam) is not for us but for these bad people. She is watching for our well-being (sukham), she gives us blessing (anugraham) and kills all asuras to protect us. So why should we have fear in front of her?25Me: Are people afraid of Bhadrakāḷi?A young devotee: What? No one fears Bhadrakāḷi. Fear only arises from some type of wrong that someone has done. We have so much faith in this Bhadrakāḷi, so how can we be afraid of her? She has a lot of anger, but we believe in that anger and we respect it. If Bhadrakāḷi punishes us we will never think she does it out of badness, but we will think that the punishment is the result of our own deeds.26

The idea that recurs throughout these responses is that Bhadrakāḷi is an awe inspiring, power-infused goddess exclusively resorting to violence for identified and justified reasons. She is entirely trusted, adored and seen as caring for her worshippers. Here, violence is not equated with danger, but with protection or more specifically with her ‘protective potency’. For Linda Iltis (quoted in Erndl 1993, p. 154), this potency is the very source of the fierce nature of certain deities, Bhadrakāḷi being a good illustration. One quite eloquent example, that again draws on the context of muṭiyēṯṯu’, is this memory recalled by a young worshipper. During one performance, a small child was sleeping on the floor in the temple precinct where the final battle scene was unfolding. As it is customary, the mythical opponents vigorously chased each other around the temple, clashing their weapons in power filled fight sequences, forcing the public to rush aside. One of the performers incarnating an asura was just about to trample the sleeping child when Bhadrakāḷi overtook him and placed herself in a protective stance over the child lying in between her mighty legs. This peculiar moment summarises what she is for them in a broader context: an all-powerful being entirely driven by justice, righteousness and a strong sense of protection.

An important aspect of her characterization that predominates all levels of interpretation and sources is that, unlike other violent goddesses whose dreadful features have been downplayed or even wiped out and replaced by mild and beautified features (smiling face, blue instead of black complexion, proportionate eyes, etc.) in processes of brahmanisation and sanskritisation27 (see e.g., Foulston 2003 for Orissa and Tamil Nadu) (see Figure 3), Bhadrakāḷi did not lose any of those gory attributes that characterise her physical appearance, even in popular contexts that only see her in an all-positive light. Here are some interview extracts that show how beauty and violence (devoid of the fear component) are both integral parts of her physical portrait when devotees mentally visualise her.

Figure 3.

Postcard showing a ‘beautified’ Kāḷi.

Me: How do you physically represent yourself Bhadrakāḷi?An elderly Brahmin: I see her with all these raudra costumes [the costume she wears in muṭiyēṯṯu’] but with a loving mind. She is frightening with her fangs (daṃṣṭram) and all, but I feel that she has a kind mind. Her eyes are also kind towards me. This raudra costume does not make me afraid.28A muṭiyēṯṯukar: She is a huge sized (anantamaya) woman, with anger (kōpam) and with a big headgear (valiya muṭi) [part of her costume in muṭiyēṯṯu’]. She is quiet and her face is beautiful/charming (saundarya) and raudra at the same time. She is an angered woman. (…) Her hair is very black, her face shows a lot of power (tējasu’). She doesn’t smile, she has her tongue outside and a lot of anger (kōpam).29A middle-aged temple officiant: In my mind she is Mother Bhadrakāḷi (‘bhadrakāḷiyamma’). When I pray she looks like a grandmother (ammacci). In my mind I like to see her that way. I imagine myself as a little boy and Kāḷi as my grandmother, but a raudra grandmother. Her hair is very black, she wears a red sari and has fangs (daṃṣṭram). She has 4 hands like kīḻkāvu’ amma (Bhadrakāḷi of the temple Chottanikkara), she has a gentle/mild (śāntam) face.30

So violence and the horror in the face of violence are here not negated in any way. But they are dissociated from their negative effects in the form of danger and fear.

What the data derived from interviews with informants as well as the different narrative sources also have in common is that, as already mentioned above, Bhadrakāḷi is inherently and primarily a warrior31. She was born to fight and to kill. War is therefore omnipresent in the myth of Dārikavadham and even more in muṭiyēṯṯu’ which clusters around the myth’s battle scenes. Here, the conspicuous idea is that the martial mission of Bhadrakāḷi is the sole justification of her creation. A muṭiyēṯṯukar explained: ‘Bhadrakāḷi is only born to kill Dārikan. When the Saptamātṛkkaḷ failed to kill him, Śiva was very angry and he opened his third eye. Śiva opens his third eye only when he is very angry. And the creature coming out is made for fighting, nothing else32’. Chelnat Achyuta Menon calls her pōrkkaḷattilamma, the ‘mother of the battlefield’ (Achyuta Menon 1943, I: 74). This is the aspect underlined in her representations via posters, idols or metal plates used as permanent or temporary icons, as well as powder floor drawings (kaḷam) made for her regular worship in Kerala temples (see Figure 4). It is the foundation of her identity. Her numerous weapons—meditation verses and versions of the myth list up to sixteen33—epitomised by the sickle shaped sword (vāḷ) held in hand by her personifications (muṭiyēṯṯukar, institutional oracle, etc.), simultaneously act as symbols of her power and mastery of fight disciplines and as receptacles of her śakti and caitanyam, materialising her martial essence34 in ritual practices devoted to her.

Figure 4.

kaḷam drawn prior to a muṭiyēṯṯu’ performance representing Bhadrakāḷi with eight hands holding weapons and riding on Vētāḷam (Photo by Thirumarayur Vijayan Marar).

Besides being depicted as an accomplished warrior, Bhadrakāḷi is also described as ‘pre-eminent war deity’ (Freeman 1991, p. 368), whose worship was linked with the practice of war. As such, she was and continues to be worshiped among the deities of the kaḷari (military/training center)35, standing at the top of the altar installed in the corner of the gymnasiums for the practice of the martial art kaḷaripayaṯṯu’. A number of nāyar families continue to have Bhadrakāḷi as their tutelary deity (Gough 1958, p. 449; Moore 1983, p. 242), which is probably a reminiscence of the traditional martial specialization of this caste. Bhadrakāḷi furthermore ‘played a central role in realising the aspirations to kingship of each of the local rulers of medieval Kerala’ (Zarilli 1998), in particular as she was (and still is) the tutelary deity of some royal families (Achyuta Menon 1936). For Richard Freeman, this link stems from the connection between the concept of śakti and royal and sacralised martial power (Freeman 1991, pp. 335–36). For Gilles Tarabout, the goddess’ warrior nature is connected with her duty to practice sacrificial violence by herself or by delegating it to inferior beings (Tarabout 1986, p. 575). Here, war is also seen in direct relation with the purely ‘deity-like’ activity she takes on after completing her mission. It is because she was successful in her lethal duty against the asura and because she perpetrated an act of extreme violence and bloodshed that she gains her right to receive worship. So war is instrumental for her very installation as deity and for the protective goddess picture that my informants unanimously endorse. The final sequence of muṭiyēṯṯu’ is a direct illustration of the interconnection between violence and protection, where the latter derives from the former: after the symbolic beheading of the asuras (both Dārikan and his twin brother Dānavēndran are beheaded here, an act symbolised by the removal of their head gears), members of the audience gather around the goddess to receive her blessing, and even small children are placed on her lap and in her arms.

Then, anger, the emotional pendant to violence, is also a key component in the characterization of Bhadrakāḷi. My informants used an extremely rich lexical field to specify and nuance this feeling when pertaining to her36. In muṭiyēṯṯu’, the anger of the goddess is manifested through gestures, as well as by the stretched out tongue, especially in the last phase of battle during which her anger is said to culminate. I already mentioned that the lolling tongue is a standard feature of the goddess’ representations subject to differing interpretations. In muṭiyēṯṯu’, it is said to be the expression of her raw anger, a feature inherent to her personae from her very birth onwards. She is ‘born from Agni in Śiva’s third eye, where there is always raudram’ said a muṭiyēṯṯukar37. An emanation of this fire is inevitably a manifestation of it, a concentrate of raudram with the associated illimitable anger and violence. Anger is more specifically the permanent attribute of her father, Śiva, inherited by his mighty daughter. He is conceived as personification of anger in both his terrible forms (ex: Bhairava) and benign forms. He thereby never completely rids himself of his ‘rudraic traits’38, unlike Bhadrakāḷi whose peaceful forms are said to be entirely devoid of anger. My informants also explain that she is ‘angry with’ the asura for disrupting the cosmic order. She was thus born from the fire and anger, created for perpetrating violence, and is filled with her own anger. Bhadrakāḷi is therefore primarily the personification of her own anger, while other violent Hindu goddesses are often conceived as personifications of other goddess’ anger (see e.g., Meyer 1986; Erndl 1993). While Bhadrakāḷi’s anger and violence are viewed as attached to her very birth, nature and mission, they are also conceived as her acting force translating through violent gestures, a superhuman strength and martial superiority that are hers alone. Jackie Assayag speaks of the goddess’ anger as the ‘active ingredient’ and ‘dynamic factor’ of her myth (Assayag 1992a, p. 105). In the context of muṭiyēṯṯu’ as well as more broadly in the cult of the goddess in Kerala, the goddess’ anger is equated with her śakti39; it is the impulse that drives her actions for the benefit of her devotees through protective or punitive actions. Here, the myth of Dārikavadham, muṭiyēṯṯu’ and other linked sources converge in stating that chaos subsides through Bhadrakāḷi’s intervention. Anger is the faculty given to her to guarantee a maximum of efficiency in this mission, it is her ‘active potency’. Consequently, it is not a negative feature of a capricious goddess or the result of a frustration, but an essential faculty assigned at her birth and without which chaos would not be reordered or dharma restored. Her innate anger as well as the anger stirred up by the asura form ‘the impulse that leads her to perform the acts by which her divinity is manifested’ (idem).

For her devotees, what matters most is the positive connotation and justified orientation of Bhadrakāḷi’s anger. Their trust and fearlessness rely on their unbending faith in this orientation and framing of Bhadrakāḷi’s wrath. In the temple of Kodungallur (Trichur district), epicentre of her cult housing the ‘elder sister’ of all Malayali Bhadrakāḷis, this characterization of her anger is highlighted in opposition to the anger of another deity said to be ‘fused’ with her. There, she is at the same time Bhadrakāḷi and Śṛī Kuṟumpa, the latter being associated with Kaṇṇaki (Achyuta Menon 1943; Chandera 1973; Choondal 1980). Kaṇṇaki, also called Śṛī Kuṟumpa or Cīrmma (by contraction) in Kerala, is the heroine of the Tamil epic Cilappatikāram. Her cult was popularised in Kerala under the patronage of the Chera kings and is deeply rooted in the folklore and devotional narratives and ritual routines of Malayali goddess temples, in which she was partly integrated into the cult of Bhadrakāḷi (Choondal 1980)40. Today, her malayalicised and re-appropriated myth is often combined and sometimes merged with some versions of the myth of Dārikavadham, especially in devotional songs and recitations performed during temple festivals (see Tarabout 1986, pp. 131–33). Now, both goddesses of Kodungallur, Bhadrakāḷi and Śṛī Kuṟumpa, are described as violent and having an extremely high potential for anger, but their anger is differentiated on the basis of their respective trigger. Cīrmma and Kuṟumpa, the part of the goddess associated with Kaṇṇaki, are called pratikāram (‘vengeance, vendetta’) dēvata (Chandera 1973, p. 16), for their anger is sparked by injustice and by the associated desire for revenge after the framing and unjust execution of Kaṇṇaki’s husband (Adigal 1961, p. 138). Her anger is therefore viewed as especially erratic, wayward and therefore dangerous because not channelled. By contrast, Bhadrakāḷi’s anger is not a potentially out-of-control-getting feeling triggered by a particular event. It is an inherent and so to say ordered characteristic of her nature meant to serve a particular prefixed target. Stability and controllability are hereby ensured.

A Brahmin explained the following about Bhadrakāḷi:

‘It is true that she is violent, but it’s not the same violence [as asuras]. Suppose a knife is being used on someone else’s body. In a criminal case, that is an asura svabhāva [i.e., a demonic/negative behaviour]. If a doctor uses that same knife to heal someone, that is a dēva svabhāva [i.e., divine/positive behaviour]. A simple act may differ in its aim’.41

So, as stated at the outset, violence can have diverse definitions based on the angle from which it is viewed.

One last important aspect of her portrait based on narrative and personalised sources, also a key ingredient for her success in battle, is her feminine nature. The asura makes it very clear, both in verbal form and through gestures in the myth and performances of muṭiyēṯṯu’, that Bhadrakāḷi is nothing for him for she is a woman and he is convinced that the strength of a woman, even a divine one, cannot match a man’s. David Shulman (1976, 1980) writes that the South Indian goddess is able to destroy her masculine opponent because of her dual nature—’physically feminine[,] but masculine in instinct and action’ David Shulman (1980, p. 211). The myth of Dārikavadham however shows that it is precisely her feminine identity that enables Bhadrakāḷi to defeat Dārikan: since he refused the boon that would have made him immune to attacks from a woman and since he accumulated curses from Brahma and Kārtyāyanidēvi who both foreshadowed his death at the hands of a woman, the asura became intrinsically vulnerable to this gender. His fate was thereby cosmically sealed. But let us dig a little more into the meaning of feminity in the case of the goddess. The myth and narrative data surrounding Bhadrakāḷi place much emphasis on the feminine gender of the goddess. Ritual powder drawings (kaḷam) and other iconographical productions representing her clearly underline her feminine physique including large breasts (in the kaḷam, her breasts are filled with paddy creating a three dimensional effect as well as a clear analogy with fertility, which is a marked feature in some of her temples, see below), feminine curves, long hair and typically female ornaments and dress (see Figure 4). Discussions with her worshippers and servants however stressed that Bhadrakāḷi’s biological femininity and the associated themes such as her sexual status, fertility and potential maternity are at best no topic at all for them, and at worst an unserious or even outrageous question to ask. It is a fact that Bhadrakāḷi is never represented nor described as spouse or said to give birth to any child. But the denial of the physical, sensual and sexual pendants to her feminity goes further than that. A young couple of worshippers to whom I mentioned the maternal nature of Bhadrakāḷi in terms of procreation spontaneously reacted with laughs and sarcastically said: ‘Ah! piḷḷa uṇṭō? Etra kuṭṭikaḷ uṇṭō?’ (‘Does she have kids? How many kids does she have?’). In their eyes, her feminity is exclusively synonymous with motherhood in a non-biological sense. Yet, on the scholarly end, Christofer Fuller (1992), and more specifically Sarah Caldwell (1999) who used data from Kerala and from the context of muṭiyēṯṯu’, argue that the anger and violence of independent goddesses (Bhadrakāḷi in the case of Caldwell) are the materialization of their inner fire resulting from contained and explicitly female sexual energy. Caldwell claims that this anger and the violence she displays are the manifestations of Bhadrakāḷi’s sexual frustration deriving from her celibacy and virginity. In his book about Tamil temple myths, David Shulman (1980) explained that the war theme is more often linked with the themes of marriage and/or sexual attraction between the goddess and her asura enemy. This connection builds on an ancient Dravidian symbolism illustrated by the Tamil Samgam poetry in which a form of sacred power (aṇaṅku, among other things attached to female sexuality) is linked with the martial sphere (battle, death, royalty) (Hart 1975). My discussions with informants rather point to the disconnection and even incompatibility between war/violence/anger and sexuality/lust/femininity in this particular context. In some temples of Kerala such as the Trceṅṅannur Mahādēvar Kṣētram in Chengannur (Allapuzha district), the goddess (here Bhagavati) is said to have her menses three to four times a year (Vaidyanathan 1988, pp. 45–48) with obvious symbolic implications linked with fertility and prosperity. The Bhadrakāḷi of the temple of Kattikkunnu (Ernakulam district) goes through the same process immediately after the completion of the performance of muṭiyēṯṯu’ at the end of her festival, beginning of March. However, according to the Brahmin owner and manager of her temple, the menstruation of the Kattikkunnu goddess has no connection with the ‘fertility’ that scholars associate with her in other contexts (see Caldwell 1999, chp. 3), but rather with the violence and derived impurity inherent to the cosmic war waged by Bhadrakāḷi and so by extension with the violence and impurity emanating from the re-actualization of this war in muṭiyēṯṯu’. The blood emanating from the very core of her female body is hereby equated with her bloodshed on the battlefield. Her feminity therefore leads us back to the nucleus of her being and raison d’être of her creation: violence at the service of a righteous divine cause.

6. Conclusions: Bloodthirsty or Not?

Now, what about the act of blood consumption in which the horror that surrounds the goddess’ portrait as per her canonical descriptions culminates? This question epitomises the whole negotiation around Bhadrakāḷi’s fearful or not fearful portrait and illustrates the broad variety of statements to be found at the narrative, ritual and personal/devotional levels as well as the sometimes overlapping of these levels.

Blood consumption is a classic and explicit feature of the local goddesses of the violent type. It is viewed as both source and manifestation of her ambivalent and threatening nature. This specifically concerns Kāḷi, and by extension her local counterpart Bhadrakāḷi, who is portrayed as having ‘a mouth that is both drinking and dripping blood’ in both her puranic and tantric portrayals (Mc Dermott 2011, p. 164). The information I gathered specifically hints at the fact that violent incarnations of Bhadrakāḷi, i.e., Bhadrakāḷis of the raudra and ghōra/ugra type (see introduction), crave blood, especially the ghōra/ugra type. A major part of their worship therefore theoretically consists in feeding them with blood in direct forms (sacrifices) and indirect forms (substitutes of sacrifices, e.g., guruti or cut vegetables/fruits). The temple complex of Chottanikkara situated on a busy commercial road fifteen kilometres eastwards from Ernakulam, has grown into a major pilgrimage site in the last twenty years. Its two goddesses, a placid Bhagavati seconded by a powerful Bhadrakāḷi, said to be the former’s ‘acting force’, are famous for healing mental and physical afflictions brought about by possession through evil spirits42. An exceptional feature of this temple’s ritual routine is the daily offering of large brass vessels (between one and twelve) of guruti conducted by Brahmin officiants in the lower part of the temple (kīḻkāvu’) dedicated to Bhadrakāḷi. Temple employees from Chottanikkara explain that the Bhadrakāḷi installed there gained her exaggerated taste for extensive blood offerings — she would only accept a minimum of three vessels per offering — from the massacre of a yakṣi (female vampire) told in a local myth43. A regular worshipper of this deity, who is also an established medical practitioner in this city, nevertheless explained to me that she only really requires a single guruti per month; and the data collected about past ritual routines in Chottanikkara confirms that there was only one guruti offered here in a month. Yet the gradual democratisation, popularisation and diversification of sponsorship of worship44 eventually gave devotees the possibility to sponsor a guruti on their own (previously it was paid by the Cochin Devasvam Board, the governmental body managing this temple) to ask for Bhadrakāḷi’s help or thank her for an already fulfilled wish. Notwithstanding the prohibitively high price of the larger gurutis (valiya ‘big’ guruti) (the cost ranges from eleven thousand rupees for three vessels to twenty-five thousand rupees for twelve vessels), the result is a tremendous multiplication of this offering proportional to the gradual increase in popularity of this temple. In the 1990s, a guruti was performed every Tuesday and Friday in Chottanikkara (Caldwell 1999, p. 129), so eight times per month. The current rhythm of guruti is one per day (one every month is still paid for by the Cochin Devasvam Board), with a majority of valiya gurutis, and the waiting list extends to five years. This shows that the exceptional frequency and volumes of guruti that are currently customary in this temple are not the result of the goddess’ alleged extraordinary and continuously growing taste for blood, but the consequence of the exponentially rising number of her worshippers and the steep increase in their need for help. The numerous blood vessels she is thus said to consume every day therefore respond to a human need, not a divine one.

For my informants pertaining to the sphere of muṭiyēṯṯu’, the issue is at the same time simple and puzzling. In recent WhatsApp interviews conducted with a man and a woman, both cousins in their thirties from a muṭiyēṯṯukar family, I received a very straight forward ‘No’ to the question ‘Does Bhadrakāḷi drink blood?’. But the answers became fuzzier when I mentioned the guruti in the temples; both of them responded that they want to check with their more knowledgeable fathers/uncles/husbands before getting back to me. In general, people connected with muṭiyēṯṯu’ completely distance the goddess from her supposed craving for blood by claiming, quoting her myth for support, that the gurutis offered to her are not addressed to her, but to the horde of evil spirits that compose her army.

Me: Is Bhadrakāḷi drinking blood at any time?Niece of a major muṭiyēṯṯukar: No, Kāḷi is not drinking blood. Dārika got one boon from Brahma that when anybody hurts his body and even just one single drop comes from his body and falls to the earth, a thousand of Dārikas will come from that blood. [In order to avoid that], her companion Vētāḷam drinks every drop of his blood to stop the enemies coming out of this blood.45

And indeed, every performance of muṭiyēṯṯu’ ends with the spilling of the red liquid on a torch staked into the ground. The ritual is conducted either by the performer incarnating the goddess, who stirs the liquid with his bare hands before pouring a few splashes onto the ground and spilling the rest by turning the vessel upside down; or by the pūjāri of the temple. The fact that the goddess herself performs this ritual act allows for no further guessing about the nature of the recipient of this blood. But what about the other moments during muṭiyēṯṯu’ where theatrical actions by the performer incarnating the goddess do suggest a blood or bloody flesh consumption by the goddess? In the performance of one family for instance46, the goddess impersonator races through the temple compound biting a garland of red coir balls. In an interview, he explained that the garland is the last remaining item of a battle sequence performed until two or three generations ago: after beheading the asura, Bhadrakāḷi tore Dārikan’s stomach open and pulled out his intestines symbolised by the red coir garland with her teeth. Nevertheless, according to the muṭiyēṯṯukar whom I had seen performing this when possessed by the goddess, this act is part of the deity’s martial mission and not linked with any likeness of hers:

The muṭiyēṯṯukar [replying to my question ‘Does Bhadrakāḷi drink blood?’]: There was a single time when Bhadrakāḷi drank blood. During the fight, Dārikan ran and hid in the lower world (pātāḷā). When he came out, he faced Kāḷi’s sword (vāḷ) and he begged that he would be good and worship her. At that time, the saints and dēvas came to see whether Dārikan was dead. Kāḷi felt pity for him and released him. But the saints and dēvas were upset by this act and started saying that she is a bad girl. Hearing this blaming, Bhadrakāḷi was ashamed. She then understands that Dārikan fooled her and her anger was increased. She finally killed him, crushed his chest open, removed his intestines and put some around her neck as an ornament. That’s the only moment when she had blood in her mouth. But this is out of anger and not because she likes it.47