Masculinity in the Sikh Community in Italy and Spain: Expectations and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Masculinity as a Social Construct

3. Data Source and Methodology

4. Sikh Masculinity in Italy and Spain

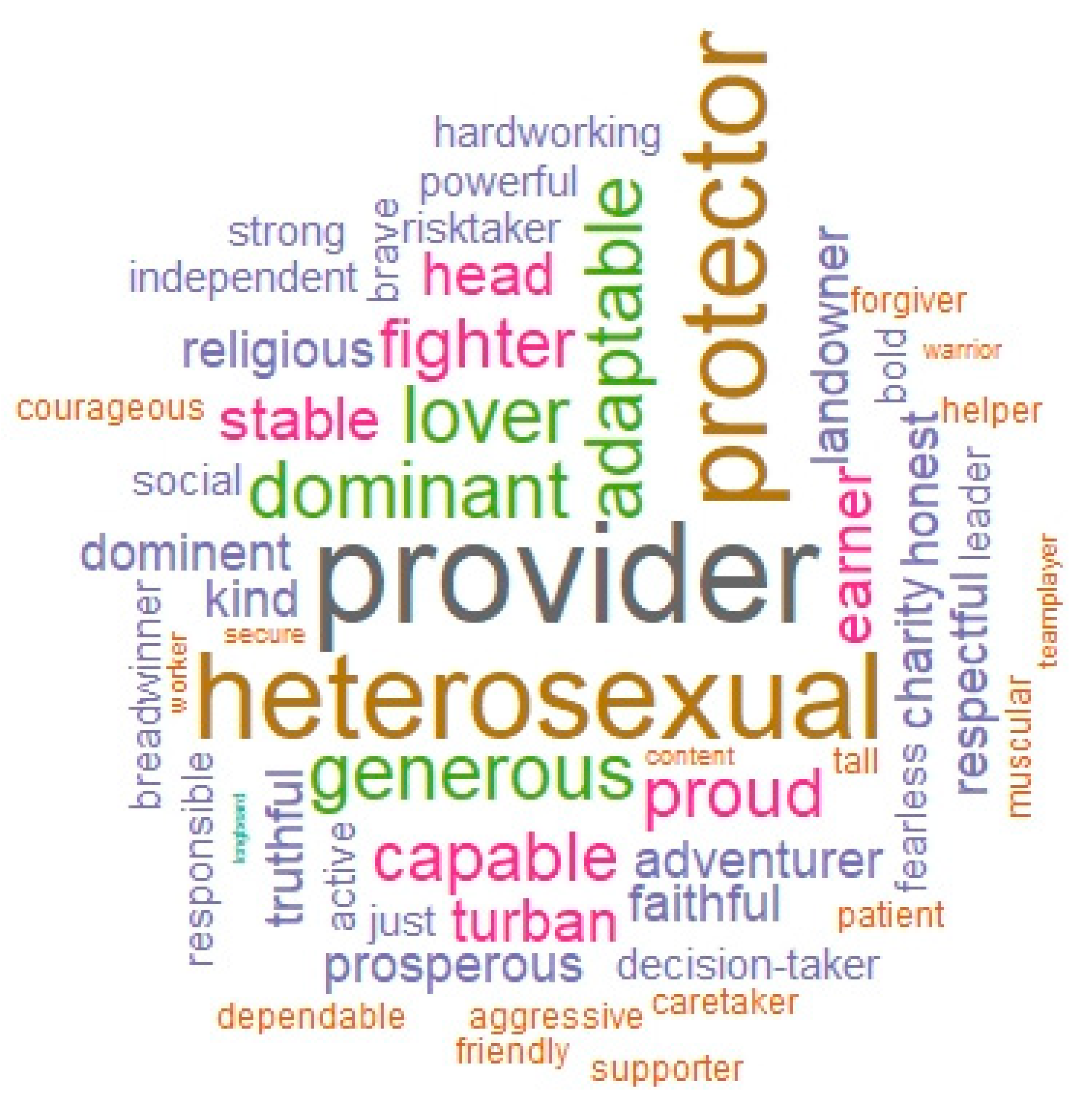

Expectations of Masculinity in the Sikh Community in Italy and Spain

5. Major Challenges Facing Sikh Men in Italy and Spain

“I was born in a Sikh family. My grandfather was a farmer in a small village on the banks of the Beas river in the Kapurthala district of Indian Punjab. He had the largest share of land in the village. He was very proud of his ability to plough the land and feed the family of 16 members, including his own 9 children. He was the supreme authority in the family and due to his strong personality, intelligence, hardworking and generous nature, he had earned a lot of respect (Izzat) in society. People used to call him Sardar Ji and for many he was a perfect model of ‘what a man ought to be’. My grandmother was a housewife. She was fully dedicated to the service of her husband and the care of children… My father, at the age of 20, was recruited in the Indian army to serve the nation in the 1971 battle with Pakistan. With his strong physique, good command over military weapons and acts of bravery in war, he earned respect as a brave soldier in the army and in society at large. In addition, with the salary received as a government employee, he managed to assume the role of breadwinner of the family. My mother is a housewife. She spent her entire life serving her husband, in-laws family and then taking care of her 4 children… I, as the first grandson of a proud farmer and the eldest son of a brave soldier, grew up in the shadow of two very dominant men, who were very proud of their achievements in life. In my early childhood, I was taught to be bold, courageous, protective and provider. When I turned 20, the mechanization of agriculture had reduced employment opportunities in the village, and due to the Khalistani movement in Punjab in 1984, the recruitment of Sikhs into the Indian army was at its lowest level. I had few opportunities to prove my worth in the family, therefore, in 2004, I emigrated to Spain to earn a living and a space in society as a ‘man’”.

5.1. Losing Control over Women

5.1.1. Challenges for Partners

5.1.2. Challenges for Parents

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bedi, Harchand Singh. 2011. The Legendary 9th Army-Italy. Sikh Net. Available online: http://www.sikhnet.com/news/legendary-8th-army-italy (accessed on 22 April 2019).

- Boyatzis, Richard E. 1998. Thematic Analysis and Code Development: Transforming Qualitative Information. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Broughton, Chad. 2008. Migration as engendered practice: Mexican men, masculinity, and northward migration. Gender & Society 22: 568–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, Geetanjali Singh, and Staci Ford. 2010. Sikh Masculinity Religion and Diaspora in Shauna Singh Baldwin’s English Lessons and Other Stories. Men and Masculinities 12: 462–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, Radhika. 2004. Encountering masculinity: An ethnographer´s dilemma. In South Asian Masculinities: Content of Change Sites of Continuity. Edited by Radhika Chopra, Caroline Osella and Filippo Osella. New Delhi: Women Unlimited/Kali for Women, pp. 36–59. [Google Scholar]

- Clatterbaugh, Kenneth. 1990. Contemporary Perspective on Masculinity: Men, Women and Politics in Modern Society. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Raewyn W. 1987. Gender and Power: Society the Person and Sexual Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Raewyn W. 2005a. Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Raewyn W. 2005b. Globalization, Imperialism and Masculinities. In Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities. Edited by Michael S. Kimmel, Jeff Hearn and Raewyn W. Connell. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Raewyn W., and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender and Society 19: 829–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, Andrea, Frank. G. Karioris, and Nancy Lindisfarne, eds. 2016. Masculinities under Neoliberalism. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Coward, Rosalind. 1999. Sacred Cows. London: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou, Demetrakis Z. 2001. Connell’s Concept of Hegemonic Masculinity: A Critique. Theory and Society 30: 337–61. [Google Scholar]

- Deol, Satnam Singh. 2014. Honour Killings in India: A Study of the Punjab State. International Research Journal of Social Sciences 3: 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Lisa, and Molly Butterworth. 2008. Questioning Gender and Sexual Identity: Dynamic Links over Time. Sex Roles 59: 365–76. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, Swarup. 2012. Green Revolution Revisited: The Contemporary Agrarian Situation in Punjab, India. Social Change 42: 229–47. [Google Scholar]

- Edley, Nigel, and Margaret Wetherell. 1995. Men in Perspective: Practice Power and Identity. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf. [Google Scholar]

- Gamburd, Michele R. 2002. Breadwinner no more. In Global Women: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy. Edited by Arlie R. Hochschild and Barbara Enrenreich. New York: Metropolitan Books, pp. 190–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Katy. 1995. Global Migrants, Local Lives: Travel and Transformation in Rural Bangladesh. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garha, Nachatter Singh. 2019. Indians in Italy: Concentration Internal mobility and Economic crisis. South Asian Diaspora. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garha, Nachatter Singh, and Andreu Domingo. 2017. Sikh Diaspora and Spain: Migration space and hypermobility. Diaspora Studies 10: 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Garha, Nachatter Singh, and Andreu Domingo. 2019. Migration, Religion and Identity: A Generational Perspective on Sikh Immigration to Spain. South Asian Diaspora 11: 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Garha, Nachatter Singh, and Angela Paparusso. 2018. Fragmented integration and transnational networks: A case study of Indian immigration to Italy and Spain. Genus Journal of Population Sciences 74: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghuman, Ranjit Singh. 2012. The Sikh community in Indian Punjab: Some socio-economic challenges. International Journal of Punjab Studies 19: 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Harjant Singh. 2012. Masculinity mobility and transformation in Punjabi cinema: From Putt Jattan De (Sons of Jat Farmers) to Munde UK De (Boys of UK). South Asian Popular Culture 10: 109–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Santokh Singh. 2014. ‘So people know I’m a Sikh’: Narratives of Sikh masculinities in contemporary Britain. Culture and Religion 15: 334–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, Matthew C. 2003. Introduction: Discarding manly dichotomies in Latin America. In Changing Men and Masculinities in Latin America. Edited by Matthew C. Gutmann. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbins, Raymond, and Bob Pease. 2009. Men and Masculinities on the Move. In Migrant Men: Critical Studies of Masculinities and the Migration Experience. Edited by Mike Donaldson, Raymond Hibbins, Richard Howson and Bob Pease. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo, Graeme. 2000. Migration and Women’s Empowerment. In Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Processes. Edited by Harriet Presser and Gita Sen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 287–317. [Google Scholar]

- Itulua-Abumere, Flourish. 2013. Understanding Men and Masculinity in Modern Society. Open Journal of Social Science Research 1: 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Stevi, and Sue Scott. 2010. Theorizing Sexuality. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsh, Doris R. 2006. Sikhism Interfaith Dialogue and Women: Transformation and Identity. Journal of Contemporary Religion 21: 183–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsh, Doris R. 2014. Gender in Sikh traditions. In The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Edited by Pashaura Singh and Luis E. Fenech. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 594–605. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsh, Doris R. 2017. Gender. In Brill’s Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Edited by Knut A. Jacobsen, Gurinder Singh Mann, Kristina Myrvold and Eleanor Nesbitt. Leiden/Boston: Brill, vol. 31/1, pp. 243–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsh, Doris R., and Margaret Walton-Roberts. 2016. A century of miri piri: Securing Sikh belonging in Canada. South Asian Diaspora 8: 167–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, Rachel, Robert Morrell, Jeff Hearn, Emma Lundqvist, David Blackbeard, Graham Lindegger, Michael Quayle, Yandisa Sikweyiya, and Lucas Gottzén. 2015. Hegemonic masculinity: Combining theory and practice in gender interventions. Culture, Health & Sexuality 17: 96–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra, Virinder Singh. 2005. Locating the Sikh Pagh. Sikh Formations 1: 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Gurwinder. 2010. The Status of Woman in Sri Guru Granth Sahib. The Sikh Review 58: 681. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur Singh, Nikky Guninder. 2000. Why did I not Light the Fire? The Re-feminization of Ritual in Sikhism. Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 16: 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur Singh, Nikky Guninder. 2005. The Birth of the Khalsa: A Feminist Re Memory of Sikh Identity. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur Singh, Nikky Guninder. 2005a. Gender and Religion: Gender and Sikhism. Encyclopedia of Religion. Encyclopedia.com. Available online: https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/gender-and-religion-gender-and-sikhism (accessed on 9 March 2019).

- Kaur Singh, Nikky Guninder. 2008. Female Feticide in the Punjab and Fetus Imagery in Sikhism. In Imagining the Fetus: The Unborn in Myth Religion and Culture. Edited by Jane Marie Law and Vanessa R. Sasson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 121–36. [Google Scholar]

- Khalidi, Omar. 2001. Ethnic Group Recruitment in the Indian Army: The Contrasting Cases of Sikhs, Muslims, Gurkhas and Others. Pacific Affairs 74: 529–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, Michael S. 1994. Masculinity as Homophobia: Fear Shame and Silence in the Construction of Gender Identity. In Theorizing Masculinities. Edited by H. Brod and M. Kaufman. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 119–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, Akriti. 2016. Militarization of Sikh Masculinity. Graduate Journal of Social Science 12: 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Ravi. 2008. Against Neoliberal Assault on Education in India: A Counternarrative of Resistance. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies 6: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Shailender. 2016. Health in the Era of Neoliberalism: Journey from State Provisioning to Financialisation. Working Paper 196, Institute for Studies in Industrial Development, New Delhi, India. Available online: http://isid.org.in/pdf/WP196.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2019).

- López-Sala, Anna Maria. 2013. From Traders to Workers: Indian Immigration in Spain. CARIM-India RR 2013/02. Fiesole: Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), European University Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Lum, Kathryn Dominique. 2016. Casted masculinities in the Punjabi Diaspora in Spain. South Asian Diaspora 8: 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maclnnes, John. 1998. The End of Masculinity. Buckingham: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Cynthia, and Stacy Brady. 2000. Guru’s Gift: An Ethnography Exploring Gender Equality with North American Sikh Women. Mayfield: Mayfield. [Google Scholar]

- Mandair, Navdeep. 2005. (EN)Gendered Sikhism: The iconolatry of manliness in the making of Sikh identity. Sikh Formations: Religion Culture Theory 1: 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerschmidt, James W. 2012. Engendering gendered knowledge: Assessing the academic appropriation of hegemonic masculinity. Men and Masculinities 15: 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, Nicola. 2006. Aspiration, reunification and gender transformation in Jat Sikh marriages from India to Canada. Global Networks 6: 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osella, Filippo, and Caroline Osella. 2000. Migration, Money and Masculinity in Kerala. Royal Anthropological Institute 6: 117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreñas, Rhacel Salazar. 2001. Servants of Globalization: Women, Migration, and Domestic Work. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parreñas, Rhacel Salazar. 2005. Children of Global Migration: Transnational Families and Gendered Woes. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Purewal, Navnet Kaur. 2010. Son Preference: Sex-Selection Gender and Culture in South Asia. London: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Sahai, Paramjit, and Kathryn Dominique Lum. 2013. Migration from Punjab to Italy in the Dairy Sector: The Quiet Indian Revolution. CARIM-India RR2013/10. Fiesole: Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, San Domenico di Fiesole (FI), European University Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Fraile, Sandra. 2013. Sikhs in Barcelona: Negotiation and Interstices in the Establishment of Community. In Sites and Politics of Religious Diversity in Southern Europe: The Best of All Gods. Edited by José Mapril and Ruy Llera Blanes. Boston: Koninklijke Brill NV, pp. 251–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sculos, Bryant W. 2017. Who’s Afraid of ‘Toxic Masculinity’? Class, Race and Corporate Power 5: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Mrinalini. 1995. Colonial Masculinity: The “Manly Englishman” and the “Effeminate Bengali” in the Late Nineteenth Century. New York: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Virdi, Preet Kaur. 2012. Barriers to Canadian justice: Immigrant Sikh women and izzat. South Asian Diaspora 5: 107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. Doing Gender. Gender & Society 1: 125–51. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Stephen M., and Frank J. Barrett. 2001. The Masculinities Reader. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Junjia. 2014. Migrant Masculinities. Gender, Place & Culture 21: 1012–28. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | According to 2011 census data, in the age group of 7 to 35 years, the number of women with university education is higher than men (97 thousand more women than men). |

| 2 | In addition to the better economic condition and the English language, this interest is also driven by the fact that it creates the possibilities of migration of other family members, such as siblings and spouse’s parents (see Mooney 2006). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garha, N.S. Masculinity in the Sikh Community in Italy and Spain: Expectations and Challenges. Religions 2020, 11, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11020076

Garha NS. Masculinity in the Sikh Community in Italy and Spain: Expectations and Challenges. Religions. 2020; 11(2):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11020076

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarha, Nachatter Singh. 2020. "Masculinity in the Sikh Community in Italy and Spain: Expectations and Challenges" Religions 11, no. 2: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11020076

APA StyleGarha, N. S. (2020). Masculinity in the Sikh Community in Italy and Spain: Expectations and Challenges. Religions, 11(2), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11020076