Abstract

The burial of unbaptized fetuses and infants, as seen through texts and archaeology, exposes friction between the institutional Church and medieval Italy’s laity. The Church’s theology of Original Sin, baptism, and salvation left the youngest children especially vulnerable to dying unbaptized and subsequently being denied a Christian burial in consecrated grounds. We here present textual and archaeological evidence from medieval Italy regarding the tensions between canon law and parental concern for the eternal salvation of their infants’ souls. We begin with an analysis of medieval texts from Italy. These reveal that, in addition to utilizing orthodox measures of appealing for divine help through the saints, laypeople of the Middle Ages turned to folk religion and midwifery practices such as “life testing” of unresponsive infants using water or other liquids. Although emergency baptism was promoted by the Church, the laity may have occasionally violated canon law by performing emergency baptism on stillborn infants. Textual documents also record medieval people struggling with where to bury their deceased infants, as per their ambiguous baptismal status within the Church community. We then present archaeological evidence from medieval sites in central and northern Italy, confirming that familial concern for the inclusion of infants in Christian cemeteries sometimes clashed with ecclesiastical burial regulations. As a result, the remains of unbaptized fetuses and infants have been discovered in consecrated ground. The textual and archaeological records of fetal and infant burial in medieval Italy serve as a material legacy of how laypeople interpreted and sometimes contravened the Church’s marginalizing theology and efforts to regulate the baptism and burial of the very young.

1. Introduction

| Quivi, secondo che per ascoltare, non avea pianto mai che di sospiri che l’aura etterna facevan tremare; ciò avvenia di duol sanza martìri, ch’avean le turbe, ch’eran molte e grandi, d’infanti e di femmine e di viri. Lo buon maestro a me: “Tu non dimandi che spiriti son questi che tu vedi? Or vo’ che sappi, innanzi che più andi, ch’ei non peccaro; e s’elli hanno mercedi, non basta, perché non ebber battesmo, ch’è porta de la fede che tu credi.” | There, as it seemed by listening, Was no wailing but only sighs that made the eternal air tremble; that arose from sorrow without torture, of these crowds that were many and great, consisting of infants and women and men. The good master said to me: “You do not ask what souls these are that you observe here? I want you to know before you go on, That they have not sinned; but their great merits are not enough, because they lack Baptism which is the gateway to the faith that you hold.” |

| Dante Alighieri, Inferno Canto IV l. 25–36 in Divina Commedia (c. AD 1308–1320; Alighieri 1966). | |

Dante’s description of unbaptized infants relegated to the teeming crowds of Limbo, the first circle of hell, epitomizes medieval anxieties concerning the spiritual state and afterlife of “unsaved” children. Throughout the Middle Ages, theologians and church leadership built on the Church Fathers’ doctrine of Original Sin, possessed by even the youngest of children, to determine the fate of unbaptized fetuses and infants. By the time that Dante penned his epic poem early in the fourteenth century, the long-established exclusion of babies who died before receiving the sacrament had been translated into ecclesiastical policies prohibiting such children from receiving Christian funeral rites and burial in consecrated grounds among the faithful.

Just as the souls of unbaptized infants were believed to reside on the periphery of hell, the corporeal remains of these individuals were consigned to burial outside of formal Christian graveyards. William Durand, Bishop of Mende, for instance, prescribed the exclusion of stillborn and unbaptized babies from Christian cemeteries in his Rationale Divinorum Officiorum (c. 1286, Book I, chp. 5; Thibodeau 2007). Consecrated ground was typically on or near church property and had been sanctified by a bishop (Binski 2001, p. 56). Even though too young to have committed any personal sin, unbaptized stillbirths and infants were nonetheless viewed as inheritors of Original Sin and therefore deserving of divine damnation. Their bodies were believed to pollute holy grounds with their unalleviated sin, so they could not be included in a consecrated cemetery. Recognizing the emotional nature of infant loss, the Church made efforts to counteract the dangers of babies dying unbaptized and receiving an ostracizing burial by, for instance, developing the concept of Limbo in the twelfth–thirteenth centuries and increasingly supporting the practice of emergency baptism (see discussion in Hausmair 2017, 2018; Le Goff [1981] 1984). Nonetheless, these protections did not extend to miscarried fetuses, stillbirths, or children who did not live long enough to be baptized. Those children were believed to spend eternity apart from God in Limbo, separated from their families in both burial and the hereafter.

Written records reveal that the unbaptized child’s liminal standing in the Christian community resulted in ambiguous baptismal and burial practices. We begin here with a discussion of domestic chronicles and miracle accounts from medieval Italy. These provide evidence for laypeople working within the bounds of Church doctrine, praying for and receiving miraculous aid from the saints or in other cases making differential decisions about where to bury their deceased infants dependent on their baptismal status. At the same time, some of these documents reveal evidence of laypeople acting outside of the figurative margins of Church doctrine by turning to folk practices and potentially performing illicit baptisms and/or burials of unbaptized or wrongly baptized infants in consecrated ground.

We then turn our attention to archaeological evidence for the burial of stillborn fetuses and perinatal individuals in medieval Italy. A growing body of archaeological evidence from throughout medieval Europe suggests that stillbirths, perinatal, and infant individuals often received funerary treatment distinct from full members of the Christian community (Craig-Atkins 2014; Craig-Atkins et al. 2018; Finlay 2000; Gardeła and Duma 2013; Hausmair 2017, 2018; Ulrich-Bochsler 1997, 2002; Wilkins and Lalonde 2008). We contribute to this field of inquiry by drawing in medieval examples from archaeological excavations conducted in central and northern Italy (Figure 1). In some cases, archaeology reveals that unbaptized fetuses were interred in hallowed ground because they were still in utero: the mothers had died before or during childbirth and yet were given Christian burial with the unbaptized infant still within (Imola, Villamagna, San Nicolao di Pietra Colice). Other examples reveal that some stillborn and presumably unbaptized infants received burial treatment that was metaphorically marginal. One example is inclusion within a formal cemetery but inside of a roof tile, observed at churches in Cittiglio and Cornaredo, and harkening back to older Roman practices observed at Acquafredda and Porto Recanati. In other cases, stillbirths or very young infants were buried in locations that were physically marginal: following the edges of a burial chamber (San Giuliano) or along the perimeters of decommissioned church baptistries (Mola di Monte Gelato, Santa Cornelia) or exteriors of church buildings (Santa Cornelia, Villamagna). These burials of fetal and infant remains serve as vivid reminders that laypeople—possibly with the tacit approval of local clergy—reinterpreted the Church’s eschatology of unbaptized babies and occasionally took actions countervailing the exclusionary boundaries of Christian mortuary spaces.

Figure 1.

Locations mentioned in the text.

2. Textual Evidence

When stillborns or children struggling to cling to life were delivered in medieval Italy, birth attendees turned to the divine for help. In this section, we explore different types of texts and what they can tell us about how medieval people conceptualized canon law regarding the exclusion of unbaptized infants from Christian burial, the solutions that they sought, and where they ultimately interred their dead. Miracle stories and domestic accounts document individuals utilizing prayer, pleas for miracles, and common midwifery procedures for revival and emergency baptisms. Childbirth charms that were spoken or sung, as well as domestic chronicles, reveal that laypeople also resorted to folk Christianity—by which we mean practices based in Christian teachings but outside of the canon practice and performed by laypeople—in hopes of rescuing babies from dying unbaptized and being buried in unhallowed ground. The texts also suggest that the families of deceased unbaptized infants who were not the recipients of miraculous intervention chose to dispose of their children’s bodies in a variety of ways. Possible resting places discussed below include beneath house floors, in dung heaps, in unmarked graves associated with churches, or remote locations far from settlements. These texts ultimately highlight parental concern and lay anxieties surrounding infant salvation and the Church’s struggle to fully regulate infant birth, baptism, and burial.

2.1. Saints and Stillbirths

Religion played a central role during medieval Italian births, and prayers and petitions to saints are frequent in narrative accounts. Miracle stories attest to the revival of stillborn infants as a result of saintly intervention. In the early fourteenth century, for example, a woman named Venturella gave birth to yet another stillborn son (Amadori Tani 2004, p. 76; Johnson 2015, p. 292). Venturella and her sister, Bellanvia, began appealing to Saint Raineri dal Borgo, already renowned for restoring another stillborn, in hopes of the infant being revived for long enough that he could be baptized. They sent also for Guilelmo, the baby’s father. Guilelmo initially told the women to stop crying, as the only thing that was left to do was to consign their son to burial, presumably in unhallowed ground. Venturella and Bellanvia, however, informed him that they had sent for him so that he could join them in petitioning Saint Ranieri. After they all prayed to the saint, Ranieri revived the stillborn child (Amadori Tani 2004, p. 76; Johnson 2015, p. 292). Another fourteenth-century miracle, this time performed by Saint Thomas Aquinas, follows midwives who, after believing an infant dead, refused to perform an emergency baptism. According to the text, Aquinas resurrected the child, “who had been believed dead for two hours or more” (qui per duas horas et amplius putabatur mortuus) (Gui 1929, p. 735; as cited in Johnson 2015, p. 277). As these accounts reveal, prayer was perceived to be a powerful tool for rescuing endangered children.

Bernard Gui’s hagiography of Thomas Aquinas also describes how the saint amended the accidental baptism of a stillborn. Gui recounts that the life of Maria, the wife of a nephew of Pope John XXII, was saved by appealing to Aquinas, as the infant was lodged in the birthing canal. When Maria finally delivered the infant, Gui writes that Maria’s mother accidentally baptized her stillborn grandchild, “believing that the mother had birthed a living child” (credens autem mater puerperæ partum viuum existere) (Gui 1929, p. 251; as cited in Johnson 2015, p. 303). Maria again appealed to the saint and the stillborn “seemed to return to life” (apparuit regeneratus); the infant girl was properly baptized before eventually (re)succumbing to death (Gui 1929, p. 251). It is unknown whether Maria’s mother was genuinely mistaken when she baptized the baby, or if she was reluctant to admit to intentionally performing the rite for a stillborn when being questioned by clerics. Either way, these miracle accounts highlight how laypeople’s desire to rescue endangered infants led them to rely on saintly intervention when baptisms within Church doctrine were no longer a possibility. Even in the case of a family directly connected to the Papacy, they relied on an appeal to St. Thomas Aquinas, the scholarly originator of Limbo, to rescue the child from that very space. Here, as in the other narrative accounts, appealing to saints was a desperate but orthodox solution to the theological marginalization and exclusion of stillborn or unbaptized infants from the Church community.

2.2. Emergency Baptism, Illicit Baptism

In medieval Italy, numerous women attended births and special attention was paid to the safety and baptism of the newborn. Expectant Italian mothers invited midwives and their friends to attend the birth and associated ceremonies (Guardiola 2002, p. 289). Especially for what was feared to be a challenging or unusual birth, several midwives would be invited to attend upon the expectant mother (Finucane 1997, p. 30). Medieval iconography—most often depicting births of high-status women—implies that between two and four midwives typically gathered to aid the woman giving birth (Finucane 1997, p. 30). A guardadonnci (“woman watcher”) was also selected to emotionally support the mother in the birthing chamber and to later care for the mother and child (Guardiola 2002, p. 290). When the mother went into labor, the invited women remained in attendance until the birth’s conclusion.

When children were born alive, the women in attendance followed a standard routine. Infants were often given a bath in warm water, possibly rubbed down with oil or other unguents, and swaddled from head to toe (Finucane 1997, p. 38). The standard midwifery practice of bathing newborns lent itself to the testing of life in newborns, but also may have been related to the practice of emergency baptisms. Baptism was regulated by the Church but took precedence when an infant struggled to survive; as such, emergency baptism could be performed by the laity, as evidenced in the fourth-century writings of St. Jerome, decreed by the fifth-century Pope Leo I, and later incorporated into the compilation of canon law by Gratian in the twelfth century (Decretum Gratiani, ca. AD 1140). The laypeople who performed emergency baptisms took up the risk of improperly performing the rite for a stillborn, as baptizing the dead was prohibited by the Church. Aquinas likened the spiritual process of infant baptism to that of a child receiving nourishment from the mother’s body (Aquinas 1981, p. 2399). Thus, just as a woman cannot supply nourishment to a miscarried or stillborn child, neither could the Church grant spiritual salvation to an already-dead child. Depending on the administrator’s knowledge of Church regulations, some laypeople might have believed that such baptisms were valid, while more informed baptizers—perhaps even local clergy—might willingly have chosen to breach ecclesiastical regulations.

In narrative accounts, the laity sometimes performed illicit baptism and thus violated ecclesiastical burial regulations, even as other family members sought to follow canon law. One such instance is found in the domestic chronicles of Luca da Panzano, a respected businessman of Florence, who documents the baptisms and burials of the numerous children birthed by his wife, Lucrezia. His Libro di Ricordanze (1425–1446) documents how one medieval Italian family attempted to comply with the Church’s burial regulations.

In one example, Luca recorded the death of his infant daughter, writing: “A feminine child whom I named Catelana, born on 19 May 1431, she lived 46 days, she was buried in Santa Croce in our large tomb, on 23 June 1431” (Una fanciulla femina, posile nome Chatelana, naque a dì 19 di Maggio 1431, vivette dì 46, è sopelita in Santa Croce ne la nostra sepoltura grande a dì 23 di giugno 1431) (Molho and Sznura 2010, p. 53; English translation of portions of Luca’s Libro also in Jansen et al. 2011, pp. 452–55). While Catelana lived long enough to be baptized and was thus buried in the family tomb in Santa Croce, a stillborn son born fourteen years later was not buried in the family crypt. Luca recalled that “…the said wife bore me a male child, according to the person who delivered him; he was baptized at home and I named him Giovanni; the person who delivered him said that he was stillborn; he was buried at San Simone in an unmarked grave…” (mi naque de la detta dona un fanciullo maschio il quale, disse chi levò il fanciullo, lo batezzò in casa e posegli nome Giovanni, disse ch’era nato morto, detta che levò il fanciullo detto; sotterossi in San Simone, non è segnato…) (Molho and Sznura 2010, p. 225). Baptizing the deceased was strictly forbidden by the Church. Based on Giovanni’s burial outside of the family tomb—and especially when compared to the ideal Christian burial of Catelana—the legitimacy of Giovanni’s baptism seems to have been in question.

Furthermore, Luca later tells a contradictory version of Giovanni’s baptism and burial when discussing the death of his wife: “She died during childbirth, and gave birth to a boy who it was said had died in her body, and yet, because it was said he breathed, he was baptized at home, and was given the name Giovanni, and was buried in San Simone, he is not in sacred ground” (Morì sopra parto e fè j° fanciullo si disse eser morto in chorpo, e pure perchè si disse avea alito fu batezato in casa e posto nome Giovanni e soterossi in Santo Simone, non è in sagrato) (Molho and Sznura 2010, p. 242). One interpretation of this retelling is that it was an attempt to obscure a potentially illicit baptism, even as the family had adhered to Church doctrine by burying the stillborn son outside the sanctified family tomb. In both accounts, however, the infant Giovanni is buried in a marginal grave—unmarked and outside of hallowed ground—beside the San Simone church, which was much less prominent than the large church of Santa Croce. It is difficult to say where such an unmarked burial outside of sacred ground would have been, but outside of the church building or perhaps outside of the churchyard walls would be likely places. In this case, it would seem probable that the local clergy at San Simone were participants in, or at least minimally aware of, this burial.

Despite what was implied in Luca’s account, medieval Italian birthing practices made it unlikely that the women present at birth would misidentify a living child for a stillborn. Medieval women, often tasked with attending births and caring for the ill and dying, were familiar with the characteristics of death and would presumably have been capable of deciphering if a newborn was truly living (Johnson 2015, p. 233). During the canonization proceedings of Saint Nicola da Tolentino (AD 1246–1305) in the summer of 1325, a midwife named Margarita de Salinguerre testified that she witnessed an infant’s death during an emergency baptism. She recalled that when she lifted the boy from the water, she “in him recognized all the signs of death in the eyes, hands, and mouth and the whole body” (in eo cognovit omnia signa mortis in oculis, manibus et ore et corpore toto) (Occhioni 1984, p. 558; Johnson 2015, p. 233). Margarita then testified that the child was miraculously resurrected through the intervention of the saint, averting a potential violation of regulations against the baptism of deceased infants.

During the AD 1240 canonization proceedings of Ambrosio of Massa held in Orvieto, two women, Dachia and Oglente, testified that they had used water to test for life in a seemingly stillborn child. They recalled attending the birth of a stillborn boy and calling for water: “Let us have some water and immerse the boy in it: if he lives at all, we will see soon” (Habeamus de aqua et mittamus puerum ibidem: si vivit aliquomodo videbatur statim) (Massa 1925, p. 581; Johnson 2015, p. 257). When the women were unable to revive the child, they claimed to have taken him out of the water before praying for his resurrection so that he could be subsequently baptized. This statement implies that Dachia and Oglente clearly distinguish between testing for life using water, on the one hand, and the rite of baptism on the other. The canonization proceedings of Ambrosio Sansedoni of Siena, beginning in AD 1287, include a similar case that involves the birth of another apparent stillborn. After Nesa, a woman who lived near Orvieto, delivered a seemingly deceased infant, the women in attendance flung both water and wine in the child’s face, as they wanted “to discern whether he was dead” (scire utrum esset mortuus) (Johnson 2015, pp. 258–59). This may have been an effort to trigger breathing in the unresponsive newborn; alternatively, or perhaps at the same time, what appeared to be an attempt to revive a child may have been aimed at baptizing the stillborn infant by sprinkling liquids upon him. The revival of stillborn infants, and by implication their rescue from an eternity of Limbo, was a key miracle cited in canonization processes, and reveals the social importance of infant baptism and proper Christian burial in medieval Italy. Furthermore, it suggests that birth attendants may have been willing to violate canon law in order to ensure salvation and its subsequent burial rights for unresponsive newborns.

2.3. Folk Practices

Alongside prayers for the intercession of the saints, emergency baptism, and midwifery practices involving water or wine, laypeople also relied on folk practices during births. Female attendees of a birth might use sung or spoken charms. These were an accessible form of Christianized folk practice that provided the women giving birth with spiritual encouragement, a magical command to bring forth children, strategic breathing methods, and instructions for labor (see Gilchrist 2012, pp. 135–38; for discussion of religious amulets, shrine souvenirs, and relics worn by pregnant women in the medieval period). Such charms, belonging to both literary and oral traditions, could be used by illiterate and semi-literate women. Perhaps the most widely used medieval charm was the Latin peperit:

Anna gave birth to Samuel, Elisabeth to John, Anna gave birth to Mary, Mary gave birth to Christ. Infant, whether male or female, whether dead or living, come out; the Savior calls you into the light.

Anna peperit Samuelem; Elisabeth Iohannem, Anna peperit Mariam, Maria peperit Christum. Infans siue masculus siue femina, siue mortuus siue uiuus, exi foras, te uocat saluator ad lucem.(Franz 1909, p. 199)

While more than sixty variations of this medieval charm are known, the core structure and content remain consistent (Elsakkers 2004, p. 181). These charms typically point to miraculous Biblical births, such as those of Elisabeth and the Virgin Mary in the variation above (Franz 1909, p. 199). The charm then directly addresses the infant and tells them to be born. In addition to encouraging women in labor by recalling seemingly impossible conceptions and births found in Christian scriptures, the structure of the charm may have lent itself to serving as a work-song when repeated verbally. The charm’s rhythm was likely adjusted to the woman’s breathing and contractions, so it served as a type of “medieval Lamaze” (Elsakkers 2004, pp. 203–5). Furthermore, the majority of the peperit’s variations include a small set of instructions to help guide women through childbirth and provide a safe delivery for the child (Elsakkers 2004, p. 194). Nonetheless, it is notable that the phrasing “whether dead or living” recognizes the very real possibility of a stillbirth, without concurrent admission that such unbaptized infants would never see the Savior’s light—at least, not according to Church doctrine.

2.4. Textual Evidence for Unbaptized Infant Burial

Narrative accounts reveal that, for infants who were not miraculously revived, the burden fell on families to decide what to do with the remains. As a result, stillborns could receive vastly different burial treatment, or even exclusion from formal burial.

Canon law repeatedly legislated that stillborns, viewed as deceased but ensouled humans, be buried in a “decent and honest place” (Séguy and Signoli 2008, p. 506; as cited by Johnson 2015, p. 250). One option for grieving parents of an unbaptized infant was a sub-floor burial within the home. This practice was recorded by Berardo Appillaterre during his testimony in Saint Nicola’s canonization proceedings in 1325. Appillaterre recalled that more than two decades earlier, his son had died before those present could baptize him (Finucane 1997, p. 45). Realizing that he could not bury his son in the churchyard, he dug a small hole in the floor of the house in which to place the infant’s body. Home burials allowed the deceased to receive a respectful burial in close proximity to the family, albeit outside of sanctified ground (see, e.g., Gaio (2004) for discussion of house-floor burials in northern Italy, dating to the Late Antique and Early Medieval periods). Such burial, however, did not soothe parental anxiety regarding the infant’s salvation, as manifest in a vision had by Appillaterre’s wife, Margarita. One night after the birth and death of her son, Margarita envisioned St. Nicola da Tolentino carrying her living son in his arms. The devil then attempted to snatch the boy away, but the infant shrank away and escaped the devil’s threatening grasp. The following day, goes the testimony, Margarita received a direct communication from Nicola himself, telling her to send her son “to the church to be buried” (ad ecclesiam ad sepeliendum) (Occhioni 1984, p. 121; Johnson 2015, p. 252). Although the text does not specify whether the remains of the infant were ultimately given a Christian burial in hallowed ground, this story testifies to parental distress over where unbaptized babies would be interred, as well as the extreme measures—miraculous intervention by a saint—needed to justify circumvention of the Church’s grim eschatology of unbaptized children.

Other texts reveal that some stillborns, rather than remaining close to their families through home burials, were—at least initially—denied burial altogether. Another witness from Saint Nicola’s canonization proceedings, Tomasso Bartolucchi, testified that he had ordered his deceased son’s body to be placed on the dung heap in the stable, revealing his suspicions regarding the effectiveness of his son’s baptism (Occhioni 1984, p. 556; as cited in Johnson 2015, p. 275). After Thomas’ son was miraculously revived, he was then brought to a church and baptized again before dying two days later (Occhioni 1984, p. 556; as cited in Johnson 2015, p. 300). Selection of such a burial location—atop a dung heap—may be why canon law repeatedly regulated that stillborns be buried in a “decent and honest place”.

Unbaptized infants were also spiritually dangerous, given the theologically marginalized position they occupied in Church doctrine. The bodies of unbaptized children were believed to pollute the entire churchyard; their presence within hallowed ground thus compromised the salvation of all interred there. This is also why conciliar statutes of the Catholic church dictated that unborn and unbaptized infants had to be cut out of a woman’s womb before she could be buried, if she died while pregnant or giving birth (Bednarski and Courtemanche 2011). It was believed that the presence of the unbaptized infant within her would constitute a threat to the sanctity of the cemetery. Sectio in mortua (“a cutting into the dead woman”), or the “Caesarian section” as it was later labeled, first emerged in early medieval ecclesiastical correspondence and was increasingly mandated by Church councils in the twelfth century and onward (Bednarski and Courtemanche 2011, pp. 42–43). Aquinas argued that “eternal death is a greater evil than the death of the body… If, therefore, the child in the mother’s womb cannot be baptized, it would be better for the mother to be opened, and the child to be taken out by force and baptized” (Aquinas 1981, p. 2401). As there was virtually no possibility of surviving such a procedure in an era before sterile surgery, the practice was applied only to pregnant women already deceased. The midwife would cut open the womb, extract the child, and quickly perform an emergency baptism. In the minority of cases where a midwife failed to administer the sacrament before the child’s death, the removal of an unbaptized, deceased infant from the womb allowed the body of the mother to be buried in sacred ground (Stensvold 2015, p. 50). Despite canon law’s promotion of the procedure, sectio in mortua was only slowly introduced into medical texts during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and only a dozen cases prior to 1550 have been documented (Bednarski and Courtemanche 2011, p. 63).

At the same time that they constituted an ecclesiastical threat, unbaptized infants were also the subject of folk beliefs associating them with the dark side of the supernatural. They were seen as frightening objects with the potential to haunt the living (Gilchrist 2012, p. 209). Throughout European history, children who died unbaptized were perceived as restless and unable to find peace, while having the potential to return to haunt their families as revenants (Caciola 1996; Craig-Atkins 2014, p. 7; Gordon 2018). Burchard of Worms, author of a collection of twenty books on canon law known as the Decretum (ca. 1012–1021), included a penitential known as the Corrector (Book XIX) that discussed contemporary folk beliefs about the body of an unbaptized infant. Because they belonged to neither the world of the living nor were they recipients of God’s salvation, unbaptized infants were a point of access by which the devil might deceive the grieving mothers, convincing them that the baby might rise up again and cause harm (Maraschi 2019, p. 45). This erroneous belief would then lead the grief-stricken women to take the body to a remote spot and impale it with a stake to prevent it from rising again (Caciola 1996, p. 29; Maraschi 2019, p. 45). Burchard imposed two years of penance on the appointed fast days as punishment for such acts.

The Decretum also prohibited women from keeping vigils at cemeteries at night, for fear that they might be committing evil deeds, perhaps associated with the illicit burial of unbaptized infants (Maraschi 2019, p. 46). A similar accusation was in fact leveled in the records from Italy’s oldest witch trial, dating to 1429, wherein a woman named Matteuccia Francisci was accused of enabling the unbaptized dead to return to the world of the living as ghosts:

Instigated by the diabolical spirit, she told many people possessed by ghosts and spirits who had come to her for remedies that they should get a pagan bone, that is a bone from a grave of an unbaptized person and bring it to a place where roads cross. Then placing the bone there and recounting nine Our Fathers with nine Ave Marias, she said these words: “pagan bone, take the [demon] from this person and take it on yourself.” Having done this, she waited nine days before returning to that road, but if returning before that day then the spirit would return [to repossess the previously afflicted person].

…diabolico spiritu instigate fantasmatichos seu spiritos habentes ad ipsam pro remedijs accedentes quam plurimos docuit ut haberent ossum paganum, hoc est sepoltorum sine bactismo et portarent ad quoddam triuium et ibi ponendo illud os dicendo novem pater noster cum nouem ave marijis at etiam dicendo ista verba, videlicet: “osso pagano ad questo el tolli et tu larecoglj.” Quo facto sic peragens, stet per novem dies ante quam redeat per uiam illam et quod si ibi infra illos dies redirect fantasma illa ad ipsam rediret.(Peruzzi 1955, pp. 8–9; note: within the Latin text, Matteucia’s incantation is given in an Umbrian medieval Italian dialect)

Even when parents like many of those in our texts appear to have cared for their children, they could have simultaneously feared supernatural repercussions after their burial. Anxiety regarding the burial of the unbaptized likely added to the perceived danger of burying “unsaved” children in consecrated grounds, adding a weight of fear to the Church’s prohibitions.

3. Archaeology of Marginality in Medieval Infant Burials

Archaeology offers the potential to evaluate the degree to which the burial practices of medieval Italians followed or deviated from the strictures of the Catholic Church regarding the exclusion of unbaptized stillbirths or infants from hallowed ground. Investigation, however, is complicated by the fact that fetal and infant remains are small, fragile, and may be lost falling through the screen when sifting excavated soil (Buckberry 2000; Squires 2014). Many miscarriages occur during the first trimester and the fetus’ low level of bone mineralization means that they will not preserve well in burials, at least under certain geological conditions such as acidic or water-logged soils (Guy et al. 1997; Manifold 2013). The immature bones of fetuses or perinatal individuals can be misidentified as animal bones by inexperienced excavators (Han et al. 2017, p. 47). Even when the remains of fetuses or newborns are discovered and properly identified, it can be difficult to conclusively determine whether these individuals were baptized before their deaths (Hausmair 2017). Only fetuses whose bones preserved well enough to determine that they died before reaching the threshold of viability can be identified as illicit burials (see Table 1 in Hausmair 2017; also Ulrich-Bochsler 1997). In sum, interpreting fetal and infant remains when found in hallowed ground is problematic and challenging.

Nonetheless, we marshal below several lines of evidence to demonstrate that religion and concern for the salvation of the soul played a central role in the burial of fetuses and infants, even when those burials contradicted the Catholic Church’s eschatology of unbaptized children. Firstly, one line of evidence is the interment of pregnant women in hallowed ground, despite the presence of an unbaptized infant still within their wombs. Secondly, fetuses are sometimes interred in official church cemeteries, but following long-standing folk burial traditions outside of the Christian canon. One example is the persistence of the Roman practice of interring fetuses and infants within roof tiles. Thirdly, echoing their marginal position within Christian theology, fetuses and infants are sometimes found along the margins of sacred spaces. This includes burials found in decommissioned baptistries and along the edges of mortuary structures, cemeteries, or church buildings.

3.1. Burial of Pregnant Women

Medieval Italian cemeteries occasionally yield burials of women found with fetal bones, whether still within the pelvic girdle or outside the mother’s body, in what have been termed post-mortem fetal extrusions or “coffin-births” (even if the woman was not interred in a coffin). These post-mortem births result from the build-up of gas in the abdominal cavity, which ultimately forces the partial or complete expulsion of the fetus (Han et al. 2017, p. 92). Burial of a deceased pregnant mother with an unborn, and therefore unbaptized, baby still within her was against strict canon law, which required that the baby be cut from the mother’s body before the mother could be buried—without her baby—in hallowed ground (Aquinas 1981, p. 2401; Bednarski and Courtemanche 2011). At the same time, opinion among the clergy was clearly not uniform, even as canon law was being set down: William Durand, at the same time that he indicated that unbaptized babies removed from their mother’s bodies must be buried outside of the cemetery, suggests that “there are some who say that the stillborn child ought to be buried with its mother within the cemetery, since it may be counted among the mother’s entrails” (Thibodeau 2007, p. 58). Depending on the age of the fetus, it is likely that those who buried in consecrated ground a pregnant woman or one who died while laboring were aware that the individual was carrying an unbaptized fetus and that their actions violated the letter of canon law.

An early example of a woman interred while still pregnant dates to the seventh–eighth century and was found in excavations at Imola (located in the Bologna district) that included additional burials of an unspecified number (Pasini et al. 2018). Within the block-lined tomb were found the well-preserved bones of an adult woman (Pasini et al. 2018, p. 78). Between the woman’s inominates and femora were the skeletal remains of an approximately 38-week-old fetus (Figure 2). The woman had undergone cranial trephination, a surgery in which a hole is cut into the skull. Evidence of bone remodeling (see, e.g., Barbian and Sledzik 2008) suggests that she survived approximately one week before succumbing to death; the fetus was expelled after the burial (Pasini et al. 2018, p. 80). The authors speculate that the trephination may have been aimed at treating a hypertensive pregnancy disorder, such as preeclampsia, symptoms of which include high fever, convulsions, high intracranial pressure, and cerebral hemorrhages (Pasini et al. 2018). The tomb was included among the cemetery lining the Roman road out of Imola and within a formalized tomb, suggestive of proper burial. Although Church doctrine regarding the removal of unbaptized pre-term infants prior to interring a woman in hallowed ground may not have been fully developed or disseminated yet, this burial is nonetheless an early example of the inclusion of an unbaptized fetus in a Christian burial context.

Figure 2.

The seventh–eighth-century fetus discovered at Imola between the mother’s pelvis and the lower limbs (reproduced with the kind permission of Pasini and colleagues 2018, p. 79).

By the time that a pregnant woman was interred at the site of Villamagna, in the High to Late Middle Ages, Church doctrine regarding the need for removal of the fetus and burial outside of holy ground would have been much more widely known. Villamagna during the medieval period included a monastery/cloister, church, village, and, in the late medieval period, a castrum (Fentress et al. 2016). A total of 491 individuals found in 384 graves were excavated at the site, found primarily in a churchyard cemetery to the west of the façade of the San Pietro church (AD 800–1400; Fenwick 2016). By contrast, fifteen individuals were buried within the church itself, in the northwestern corner of the nave, with radiocarbon dating indicating that these interments took place in the late medieval period (calibrated 95% probability AD 1280–1400). The individuals interred in the church were taller on average than those buried outside of the church and 35% had been buried with finger-rings and other adornments, when only 11% of individuals in the cemetery had evidence of such wealth (Fenwick 2016, pp. 374–75). These factors corroborate burial location in defining these as high-status members of the medieval community of Villamagna.

One of the adult individuals interred inside the San Pietro church was a woman aged 20–30 years, found with the bones of a 38–40 week gestational age fetus still within her pelvis (Fenwick 2016, p. 363). Her status and membership in a comparatively wealthy family may account for why this woman was not only buried in hallowed ground, but within the nave of the church itself, despite the unbaptized baby still within her.

The researchers note that the burial assemblage from the wider Villamagna cemetery contains “the remains of a few late-term foetuses” (Cox and Candilio 2016, p. 392), but do not provide further details. It is not possible to know whether these individuals lived long enough for emergency baptism, which would have made them legitimate members of the Christian burial community, or if their inclusion in the cemetery associated with the church of San Pietro violated Church doctrine.

A final example of a woman buried while still pregnant dates to the late fourteenth century and comes from a graveyard surrounding the church of San Nicolao di Pietra Colice and a medieval hospital southeast of Genova. While each of the other graves—approximately 30 in all (Mennella 2006)—contained a single individual, this multiple grave contained two sub-adults aged approximately three and twelve years old, in addition to the pregnant woman aged between 30 and 39 with her full-term fetus (38–40 weeks) still partially within the birth canal (Cesana et al. 2017). Archaeologists determined that these individuals were buried together at the same time (Cesana et al. 2017, p. 15). Genetic testing detected the F1 antigen of Yersinia pestis, the microorganism responsible for the bubonic plague, in the pregnant mother, fetus, and the elder child; thus, they were all probable plague victims (Cesana et al. 2017, p. 21). Although it is possible that this exceptional burial may have been necessitated by fear of contamination during the early days of what would become the deadliest outbreak of the Black Death in human history, interment of this pregnant mother in the church cemetery nevertheless represents a deviation from canon law. Although we cannot be sure of the biological relationship between the pregnant woman and the other two children, the pathos of the death of the pregnant woman and a desire to keep the family unit—at least of the woman and her unborn infant—together in the hereafter may have induced burial without first conducting a sectio in mortua to remove the fetus (see Craig-Atkins (2014) for medieval burials where infants and possible mothers were found in association; see Millett and Gowland (2015) for parallel practices during the Roman period).

3.2. Tile Burials

In some cases, medieval Italians appear to have drawn upon long-standing pre-Christian traditions to inter stillborn infants and deceased newborns. More specifically, they continued a wide-spread Roman tradition of burying fetuses and infants in upside-down roof tiles or paired tiles placed edge to edge to form a tube. Roman examples of this practice have been found in the necropolis of Acquafredda (Brescia), where fifteen infants were found buried in tiles (Licata et al. 2018, p. 1528), and at the Roman site of Porto Recanati (Marche), where babies younger than twelve months of age were interred under roof tiles or in amphorae (Harlow and Larsson Loven 2011, p. 43; see also Gaio 2004).

High and late medieval examples of tile burials come from the church of San Biagio in Cittiglio, located to the northwest of Milan. The first phase of the cemetery dated to the period AD 1000–1200 and consisted exclusively of individual graves—a total of 22 tombs of both juveniles and adults—with the exception of one grave that contained a 6–8-year-old child and a fetus laid to rest in a roof tile (Licata et al. 2019, pp. 170–71). This walled and possibly roofed “funerary atrium” was located just outside of the church and thought to have been the resting place of the elite families that owned the church and its surroundings: the De Cittiglio, De Morsiolo, and lastly the Besozzi families (Licata et al. 2019, p. 165). Depending on the age of the fetus and whether stillborn or viable for emergency baptism, inclusion in the family tomb may represent a skirting of canon law prohibiting the interment of the unbaptized, possibly carried out with the knowledge and assistance of a sympathetic priest.

While elevated social status and familial connections may account for the inclusion of the fetus in the family crypt, additional fetal tile burials were found in the open-air cemetery at the front of the church, which dates to the period AD 1300–1600. This cemetery, representing an expansion in the funerary accessibility of the chapel to the broader medieval village community (see Tronti 2008 for a similar phenomenon at Monte di Croce and Montefiesole, near Florence), yielded an additional 17 graves containing 39 individuals. Four of these were fetuses who had been interred in roof tiles (Licata et al. 2019, pp. 180–81). Osteological analysis has been published for only one of these graves, which contained a fetus of 21–24 weeks gestational age who had been laid out in an upside-down roof tile, next to the body of an infant of 6 months to 1 year of age (Licata et al. 2018, p. 1528; Licata et al. 2019, p. 171;Figure 3). Given the very young gestational age of the fetus, survival outside the womb would have been impossible, even long enough to conduct an emergency baptism. These tile burials suggest that even non-elite members of the medieval Cittiglio community declined to follow the letter of canon law regarding interment of the unbaptized in the church cemetery.

Figure 3.

Photograph and plan drawing of the 0.5–1-year-old infant (grave 26) and the 21–24 weeks gestational age fetal tile burial (grave 27), from the church cemetery associated with San Biagio (photo and drawing used with the kind permission of Licata and colleagues 2019, p. 179).

Although the “ritual of the tile” continued throughout the Italian Middle Ages, it became less commonplace over time (Licata et al. 2018, p. 1528). This is likely due to the Church’s increasing efforts to regulate how medieval Christians ought to bury the dead. Some of the latest published examples are found in the church of San Paolo di Pietro all’Olmo (Cornaredo, near Milan). Within the church, at least 15 fetal or perinatal individuals—one as young as 18 weeks but most between 36 and 40 weeks gestational age—were found interred between two roof tiles (Zopfi et al. 2010). Coins included within these tile burials provide a terminus ante quem of the early to mid-sixteenth century (Zopfi et al. 2010). At a minimum, it is very unlikely that the fetus of 18 weeks gestational age was viable at delivery, precluding emergency baptism. While some of the other perinatal individuals may have survived long enough to receive emergency baptism and thus do not represent illicit burials, it is nonetheless significant that space within the church building itself was reserved for the youngest members of the religious community. At the same time, the burial container and inclusion of a coin harken back to long-standing, albeit pagan, burial practices (see, e.g., Carroll 2011).

Although almost certainly used for the unbaptized, tile burials during the medieval period may have offered the weight of tradition to grieving parents as they decided how to bury their infant. Perhaps this form of burial was considered socially acceptable and all the more appropriate because it had been used by pre-Christian Romans. The continuation of this ancient tradition into the Middle Ages—as well as the inclusion of one or more coins accompanying the fetal/infant tile burial at San Paolo di Pietro all’Olmo (Zopfi et al. 2010)—serve as additional examples of reliance on a folk practice in the course of carrying out an act that was marginalized by mainstream canon law.

3.3. On the Margins of Sacred Spaces

Infants, and sometimes fetuses, were also buried along the physical margins of religious spaces. In this section, we discuss the burial of individuals marginalized by Church doctrine in marginal physical spaces that include decommissioned baptistries, along the walls of burial chambers, and aligned with the outside walls of churches and other religious buildings.

With an increasing emphasis on infant baptism, small standing fonts came to be preferred over sunken baptismal pools, previously used in immersion baptisms of adults (Christie and Daniels 1991, p. 180). Associations between baptismal fonts and infant burials have been observed elsewhere, including medieval England (Gilchrist 2012, p. 206) and Central Europe (Austria and Switzerland; Hausmair 2017, pp. 222–23). Excavations have revealed concentrations of child, infant, and sometimes fetal burials in the northwestern corner of medieval churches, presumably where a standing baptismal font would have been located. As noted by Gilchrist (2012, p. 206), “[b]urial of the very young in this locale may have been considered to extend the sacramental efficacy of baptism,” or, as Hausmair notes (2017, p. 223), “to bestow the holy rite’s transformative powers on unbaptized children.”

At several churches in central Italy, decommissioned baptistries proved to be a favored location for the interment of fetal, infant, and child remains. One such example is the church at the Mola di Monte Gelato, located just north of Rome. During the period AD 800–1100, infants were placed around a semi-immersion baptistery that had been decommissioned and gone out of use (Gilkes and Potter 1997, p. 90). While infant remains were uncovered in each excavated section of the site, the decommissioned baptistery, ante-room to the north of the baptistery, and along the baptistery’s outside wall were reserved almost solely for infant burials (Potter and King 1997, p. 108). This phenomenon is most clearly seen inside the baptistery itself, where almost 80% of the remains belonged to individuals who died before reaching the age of six (Conheeney 1997, p. 166).

The practice of including children almost certainly old enough to have been baptized may speak to a more generalized local practice regarding an appropriate burial location for individuals not necessarily considered full members of the Church community. These may have included, for example, those who had not received communion or confirmation (Tanner and Watson 2006), or perhaps following Isodore of Seville in considering those below the age of seven still in infantia (ca. AD 615-early 630’s; Barney et al. 2010). Nonetheless, Janice Conhenney, the osteologist for the Mola di Monte Gelato project, specifically notes that the preference for burying infants in and around the baptistry “may be related to the recent christening of the infants, or perhaps their unbaptized status” (Conheeney 1997, p. 129). The memory and symbolic importance of the previously active baptistery motivated medieval Christians to place stillborns and other deceased unbaptized children in this specific location, as well as immature individuals who may have been baptized.

Moreover, the excavators of Mola di Monte Gelato note that the baptistry interments include a number of the most elaborate tombs at the site, including one burial that contained a silver denarius coin of Pope Hadrian III (AD 884–885). This suggests that “child burials within the baptistry may reflect higher social ranking within the community” (Potter and King 1997, p. 108). As seen with the burial of the pregnant woman inside the church at Villamagna, the social status and wealth of the family may have been a factor mediating adherence (or lack thereof) to Church laws prohibiting infant and fetal interment in hallowed ground.

The practice of burying infants, as well as fetal remains, within a decommissioned baptistery has been observed at another central Italian church, that of Santa Cornelia. The decommissioning of the baptistery approximately in the period AD 900–1000 was followed by the emplacement of numerous child, infant, neonate, and possibly even fetal burials in the former baptistry (Christie and Daniels 1991, p. 181). As noted by Christie and Daniels (1991, p. 181), this practice was “perhaps relating to unbaptized, still-born infants; whether this is merely a coincidence of location or a memory of the role of the demolished baptistery cannot be ascertained.” It is likely that grieving parents of unbaptized infants may have sought “retrospective baptism” and salvation for their children’s immortal souls through burial in and around the decommissioned baptistries.

A desire for posthumous baptism may account for another practice observed in medieval Italy, which is the burial of infants and fetuses along the exterior walls of churches. Similar burials have been termed “eaves-drip burials,” with the most widely accepted interpretation being that rain, sanctified by touching a consecrated structure, would run over the building’s eaves and drop onto the child burials, thereby serving as an unsanctioned substitute for those who had not received official baptism (Craig-Atkins 2014, p. 6; Hadley 2010, p. 109). It should be noted, however, that ethnographic documentation of this conceptualization dates to nineteenth-century Protestant contexts, while R. Schmitz-Esser (2014) has demonstrated that there are no known medieval texts that refer to this belief. Instead, as argued by Hausmair (2020), this interpretation in medieval contexts has evolved through uncritical quoting practices among archaeologists, who have perhaps erroneously attributed this belief to earlier periods.

Whether buried in the belief that the unbaptized infants may benefit baptismally from water falling from church roofs, or whether burial location might simply reflect the marginal status of the interred, there is no question that some medieval Italian cemeteries show clustering of infants and small children along exterior church walls. This is seen in a series of small graves aligned with and immediately adjacent to the exterior of the northern wall of the Santa Cornelia church (Christie and Daniels 1991, p. 71). At Villamagna, the burials of infants (up to two years of age) were clustered at the periphery of the cemetery, but on either side of the church entrance (Fenwick 2016, p. 372). These burials are often parallel to the church façade, rather than the east-west burial alignment typical of Christian burial, which may relate to the fact that rainwater could then wash from the church’s façade wall over the whole infant body within the graves.

Archaeological evidence discussed thus far demonstrates that there are some commonalities shared by individuals whose burials did not adhere to canon law: they were wealthy and of high status (such as the pregnant woman buried within San Pietro church at Villamagna, or the infants buried with grave goods in the decommissioned baptistry of the church at Mola di Monta Gelato), and/or part of a family burial (such as the family funerary atrium at San Biagio of Cittiglio, or the burial of the pregnant woman with family members within the church at Villamagna). These factors may have been at work in the burial of several fetuses excavated by the authors at the medieval site of San Giuliano (near Viterbo, Lazio).

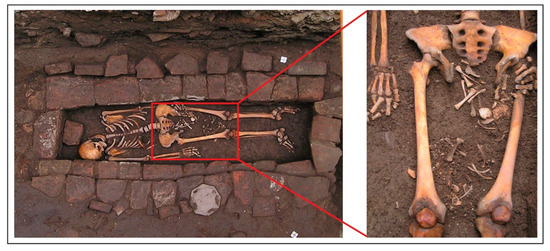

The Rocca portion of the San Giuliano plateau comprises a medieval fortified castle, including walls, gates, a collapsed tower, a feasting hall, and a mortuary enclosure with tombs cut down into the bedrock, quite possibly associated with a chapel entered through a door in the western wall of the structure (Figure 4). Radiocarbon dates obtained from excavation of the medieval hall date the occupation to the period AD 1100–1300. The mortuary structure was partially excavated in the early 1990s by community archaeologists, who discovered that the central and largest tomb in the structure contained an adult female and a fetus or perinatal infant (Guerrini 2001, personal communication 2019; grave cut B in Figure 4). The structure was not subsequently excavated in its entirety.

Figure 4.

The mortuary structure at San Giuliano. The letters indicate tombs cut into the bedrock. An adult female interred with a fetus or perinatal infant was found in Tomb B. The twin fetuses were found in Tomb F (photo by E. Varley, overlay by C. Zori).

In the summer of 2019, cleaning of the half-excavated burial structure at San Giuliano exposed the interment of two 27-week-old fetuses in a single grave cut (Tomb F in Figure 4; osteological analysis by Lori Baker; Baker 2019). This grave cut paralleled the east-west orientation of the other primary tombs in the structure, but was located along the margins of the building, partially within the architectural foundation trench of the ossuary’s northern wall (Figure 4). Although ancient DNA analysis of the remains is ongoing, the fetuses’ shared gestational age and joint burial suggests that they were likely twins. As these individuals were too young to survive outside of the womb for baptism, their burials in the ossuary were in violation of Church law. Nonetheless, they were carefully interred within the mortuary structure, following burial traditions applied to adult members of the social group. The small size of the mortuary enclosure, in addition to its probable association with an adjacent family chapel, suggests that this space was used for burial of the elite kin group that once controlled the castle. Beyond determining whether the two fetuses were indeed twins, DNA analysis is underway to establish the familial relationships between those interred in the mortuary enclosure, which will provide additional support to the designation of the structure as a family tomb for San Giuliano’s elite. As has been determined through the archaeological examples detailed above, wealth, status, and family ties may have been determining factors in the inclusion of these stillborn fetal twins within the family crypt of San Giuliano’s ruling elite, albeit along the physical margins of the mortuary space.

4. Conclusions

Rather than abandoning their faith when the traditional, accepted methods of appealing to the divine for help failed to save children from dying unbaptized, the laity turned to illicit or folk burial practices on the margins of Church doctrine. Texts reveal that parents and birth attendees first turned to prayer, opportuning saints for miraculous recoveries of stillborn infants so that they could be officially baptized. Parental concern for infant salvation can be seen in the use of birthing charms and in efforts such as testing for life in struggling infants. The choice of where to then inter infants who died before being baptized presented a challenge. Berardo and Margarita Appillaterre initially elected to bury their “unsaved” child within their home in hopes of keeping them close. Even when Tomasso Batholucius placed his deceased, unbaptized son to be buried on a dung pile, he continued to plead with a saint to save the life of his son. Saints themselves at times bent or broke Church regulations: for example, Saint Nicola deemed Margarita de Salinguerre’s vision of her son’s baptism as reason enough for giving the child Christian funeral rites.

The archaeological literature illustrates the reality of how medieval Italy’s laity responded to the Church’s marginalizing theology and regulations of burial practice. Because families were generally left with the task of disposing of the bodies of deceased unbaptized children outside the purview of clerical scrutiny, the spatial relationship between the burials of unbaptized children and the rest of the population serves as a material legacy for how lay Christians interpreted and responded to the Church’s theology and regulations. Burials in physically marginal spaces—in decommissioned baptistries, along the exterior walls of churches, or the internal wall of a family crypt—testify to efforts of grieving parents to follow Church doctrine while still attempting to glean some possibility of salvation for their unbaptized and theologically marginalized offspring. In at least some cases, the clergy must have been aware of, and perhaps even sanctioned, the burial of unbaptized infants. This is particularly likely in the case of women who died while pregnant or in childbirth and who were interred with the fetus still inside. It is unlikely that burials within decommissioned baptistries at Mola di Monte Gelato and Santa Cornelia and the tile burials of infants and fetuses beneath the floor of San Paolo di Pietro all’Olmo could have occurred without the knowledge or approbation of religious authorities.

In at least some cases, it appears that family ties, as well as wealth and status, were important factors in determining how laypeople buried unbaptized children. The burial of a pregnant woman within the San Pietro church at Villamagna, in a grouping that likely represents her family, attests to the fact that wealthy members of a church could obtain preferential treatment and were not obliged to remove the body of an unborn child before interment directly within the church nave. Family ties may also have influenced the interment of a pregnant woman, her fetus, and two deceased children, all victims of the Black Plague, in a church cemetery in Genova. Wealth may have been a factor in the burial of unbaptized infants in the decommissioned baptistry of the church at Mola di Monte Gelato. Finally, membership in a wealthy and powerful family may have been used to justify the interment of stillborn, and thus unbaptized, twins in the family crypt at San Giuliano and in the tile burial in the funerary atrium of the San Biagio church.

Written accounts and archaeological examples of burials that were religiously symbolic, albeit illicit, reveal how ordinary laypeople, disconnected from the lofty theological writings of high-ranking clerics and theologians, offered up their own eschatology of unbaptized infants. These atypical burial placements illustrate that laypeople viewed these children as distinct from the rest of the Christian community and, to some extent, accepted the Church’s stance that these children were still guilty of possessing Original Sin. Nevertheless, the families of such fetuses and newborns occasionally went against the Church’s orders to grant their children Christian funeral rites, revealing a complex relationship between medieval Italy’s laity and the institutional Church. While it is unclear whether these burial placements represented a complete or conscious rejection of the Church’s position on unbaptized children or merely a hope for the eventual rescue of these individuals on Judgement Day, these grieving parents nonetheless made burial decisions that symbolically challenged the Church’s marginalization of unbaptized children.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of this research and development of the methodology was shared by M.C., C.Z. and D.Z. Background research on textual sources and archaeological evidence was conducted by M.C., who also wrote the first draft of this manuscript. D.Z. translated Latin and medieval Italian passages. C.Z. directed the excavation of the mortuary structure at San Giuliano and the recovery of the fetal remains, and oversaw their subsequent analysis by project osteologist, Lori Baker. D.Z. is the director of the San Giuliano Archaeological Research Program and together with C.Z., reviewed and edited the manuscript and augmented the use of both textual and archaeological evidence. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding through Baylor University.

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude to the people of Barbarano Romano, who have supported our work at San Giuliano, including Mayor Rinaldo Marchesi, Angela Cassota, and Angelo Fiaschetti. Our Italian partners, Virgil Academy and Gianni Profita, have provided invaluable logistical assistance. We also thank Paola Guerrini and Lori Baker, who provided important data about the mortuary structure and the osteology of the people buried there. We thank all the SGARP field school students for their hard work in the field. Rebecca Johnson’s excellent dissertation drew our attention to a series of the hagiographical sources used in this article. We thank Mary Watt for discussions on the Libro of Luca di Panzano and the church of San Simone in fourteenth-century Florence. We thank the editors of this special edition of Religions for the invitation to contribute our work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alighieri, Dante. 1966. Divina Commedia. Edited by Giorgio Petrocchi. Milano: Mondadori. [Google Scholar]

- Amadori Tani, Leonilde, ed. 2004. Il Libro dei Miracoli del Beato Ranieri dal Borgo. Montepulciano: Le Balze. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1981. Summa Theologica. Translated by Fathers of the English Province. Westminster: Christian Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Lori. 2019. Human Osteology Report for San Giuliano Archaeological Research Project. In San Giuliano Archaeological Research Project: Report for the 2019 Season. Edited by Davide Zori. Unpublished Report Submitted to the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per l’Area Metropolitana di Roma, la Provincia di Viterbo e l’Etruria Meridionale. [Google Scholar]

- Barbian, Lenore T., and Paul S. Sledzik. 2008. Healing following cranial trauma. Journal of Forensic Sciences 53: 263–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, Stephen A., Wendy J. Lewis, Jennifer A. Beach, and Oliver Berghof, trans. 2010. The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarski, Steven, and Andrée Courtemanche. 2011. ‘Sadly and with a Bitter Heart’: What the Caesarean Section Meant in the Middle Ages. Florilegium 29: 33–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binski, Paul. 2001. Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation. London: The British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Buckberry, Jo. 2000. Missing, Presumed Buried? Bone Diagenesis and the Under-Representation of Anglo-Saxon Children. Assemblage 5. Available online: http://www.assemblage.group.sher.ac.uk/5/buckberr.html (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Caciola, Nancy. 1996. Wraiths, Revenants and Ritual in Medieval Culture. Past and Present 152: 3–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Maureen. 2011. Infant death and burial in Roman Italy. Journal of Roman Archaeology 24: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesana, Deneb, Ole J. Benedictow, and Raffaella Bianucci. 2017. The Origin and Early Spread of the Black Death in Italy: First Evidence of Plague Victims from 14th-Century Liguria (Northern Italy). Anthropological Science 125: 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, Neil, and Charles Daniels. 1991. Santa Cornelia: The Excavation of and Early Medieval Papal Estate and a Medieval Monastery. In Three South Etrurian Churches: Santa Cornelia, Santa Rufina and San Liberato. Edited by Neil Christie. Archaeological Monographs of the British School at Rome, No. 4. London: British School at Rome, pp. 1–209. [Google Scholar]

- Conheeney, Janice. 1997. The Cemetery: The Human Remains. In Excavations at the Mola di Monte Gelato. Edited by Timothy W. Potter and Anthoy C. King. Archaeological Monographs of the British School at Rome 11. London: The British Museum, pp. 118–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Samantha, and Francesca Candilio. 2016. Infants and Children. In Villa Magna: An Imperial Estate and Its Legacies, Excavations 2005–2010. Edited by Caroline Goodson, Elizabeth Fentress and Marco Maiuro. London: British School at Rome, pp. 391–93. [Google Scholar]

- Craig-Atkins, Elizabeth, Towers Jacqueline, and Julia Beaumont. 2018. The role of infant life histories in the construction of identities in death: An incremental isotope study of dietary and physiological status among children afforded differential burial. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 167: 644–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig-Atkins, Elizabeth. 2014. Eavesdropping on Short Lives: Eaves-Drip Burial and the Differential Treatment of Children One Year of Age and Under in Early Christian Cemeteries. In Medieval Childhood: Archaeological Approaches. Edited by Katie A. Hemer and Dawn M. Hadley. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Elsakkers, Marie-Anne. 2004. In Pain You Shall Bear Children (Gen 3:16): Medieval Prayers for a Safe Delivery. In Women and Miracle Stories: A Multidisciplinary Exploration. Edited by Anne-Marie Korte. Leiden: Brill, pp. 179–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mennella, Giovanni. 2006. San Nicolao di Pietra Colice. FastiOnline Database. Available online: http://www.fastionline.org/excavation/micro_view.php?fst_cd=AIAC_276&curcol=sea_cd-AIAC_811 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Fentress, Elizabeth, Goodson Caroline, and Marco Maiuro, eds. 2016. Villa Magna: An Imperial Estate and Its Legacies. Excavations 2006–2010. Archaeological Monographs of the British School at Rome, 23. London: British School at Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick, Corisande. 2016. The Medieval Cemetery: The Cemetery and Burial Practices. In Villa Magna: An Imperial Estate and Its Legacies, Excavations 2005–2010. Edited by Caroline Goodson, Elizabeth Fentress and Marco Maiuro. London: British School at Rome, pp. 351–76. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, Nyree. 2000. Outside of life: Traditions of infant burial in Ireland from cillín to cist. World Archaeology 31: 407–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, Ronald C. 1997. The Rescue of the Innocents: Endangered Children in Medieval Miracles. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, Adolf. 1909. Die kirchlicken Benediktionen im Mittelalter. Freiburg: Herdersche Verlagshandlung, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gaio, Simone. 2004. “Quid Sint Suggrundaria” La Sepoltura Infantile a Enchytrismos di Loppio-S.Andrea (TN). Annali dei Musei Civici di Rovereto 20: 53–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gardeła, Leszek, and Paweł Duma. 2013. Untimely death: Atypical burials of children in early and late medieval Poland. World Archaeology 45: 314–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, Roberta. 2012. Medieval Life: Archaeology and the Life Course. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilkes, O., and Timothy W. Potter. 1997. The Baptistries. In Excavations at the Mola di Monte Gelato. Edited by Timothy W. Potter and Anthoy C. King. Archaeological Monographs of the British School at Rome 11. London: The British Museum, pp. 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Stephen. 2018. Dealing with the Undead in the Later Middle Ages. In Dealing with the Dead: Mortality and Community in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Thea Tomaini. Explorations in Medieval Culture, Volume 5. Leiden: Brill, pp. 97–128. [Google Scholar]

- Guardiola, Ginger Lee. 2002. Within and Without: The Social and Medical Worlds of the Medieval Midwife, 1000–1500. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of History, The University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini, Paola. 2001. Primi risultati dalla ricognizione nel territorio di Barbarano Romano: Gli esempi del Quarto, San Giuliano e la Macchia. In Dalla Tuscia Romana al Territorio Valvense: Problemi di Topografia Medievale Alla Luce Delle Recenti Ricerche Archeologiche. Edited by Letizia Ermini Pani. Rome: La Società alla Biblioteca Vallicelliana, pp. 57–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, Bernard. 1929. Fontes Vitae S. Thomae Aquinatis. Edited by Dominucus Prümmer. Saint-Maximin: Bureau de la Revue Thomiste, vol. III. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, Herv, Masset Claude, and Charles-Albert Baud. 1997. Infant Taphonomy. International Journal Osteoarchaeology 7: 221–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, Dawn M. 2010. Burying the socially and physically distinctive in and beyond the Anglo-Saxon churchyard. In Burial in Later Anglo-Saxon England, c. 650–1100 A.D. Edited by Jo Buckberry and Annia Cherryson. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 101–13. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Sallie, Tracy K. Betsinger, and Amy B. Scott, eds. 2017. The Anthropology of the Fetus: Biology, Culture, and Society. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, Mary, and Lena Larsson Loven. 2011. Families in the Roman and Late Antique World. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmair, Barbara. 2017. Topographies of the afterlife: Reconsidering infant burials in medieval mortuary space. Journal of Social Archaeology 17: 210–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmair, Barbara. 2018. Break a Rule but Save a Soul: Unbaptized Children and Medieval Burial Regulation. In Archaeologies of Rules and Regulation: Between Text and Practice. Edited by Barbara Hausmair, Ben Jervis, Ruth Nugent and Eleanor Williams. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmair, Barbara. 2020. Traufkinder’ im Mittelalter? Überlegungen zu Kleinkindbestattungen, Taufstatus und einem populären Deutungsansatz. In Leben mit dem Tod. Der Umgang mit Sterblichkeit in Mittelalter und Neuzeit. Beiträge der internationalen Tagung in St. Pölten 11. Bis 15. September 2018. Edited by Thomas Kühtreiber, Ronald Risy, Gabriele Scharrer-Liška and Claudia Theune. Wein: ÖGM, pp. 150–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Katherine L., Joanna Drell, and Frances Andrews, eds. 2011. Medieval Italy: Texts in Translation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Rebecca Wynne. 2015. Praying for Deliverance: Childbirth and the Cult of the Saints in the Late Medieval Mediterranean. Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff, Jacques. 1984. The Birth of Purgatory. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Licata, Marta, Chiara Rossetti, Adelaide Tosi, and Paola Badino. 2018. A Foetal Tile from an Archaeological Site: Anthropological Investigation of Human Remains Recovered in a Medieval Cemetery in Northern Italy. Journal Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Medicine 31: 1527–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licata, Marta, Silvia Iorio, Chiara Rossetti, and Paola Badino. 2019. The Medieval Church of San Biagio in Cittiglio (Varese, Northern Italy). Archaeological and Anthropological Investigations of the Cemeterial Area. Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica 25: 163–83. [Google Scholar]

- Manifold, Bernadette. 2013. Differential preservation of children’s bones and teeth recovered from early medieval cemeteries: Possible influences for the forensic recovery of non-adult skeletal remains. Anthropological Review 76: 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maraschi, Andrea. 2019. There is More than Meets the Eye. Undead Ghosts and Spirits in the Decretum of Buchard of Worms. Thanatos 8: 29–61. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, Ambrosio of. 1925. Processus Canonizationis. Bruxelles: Acta Sanctorum, pp. 571–608. [Google Scholar]

- Millett, Martin, and Rebecca Gowland. 2015. Infant and child burial rites in Roman Britain: A study from East Yorkshire. Britannia 46: 171–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molho, Anthony, and Franek Sznura, eds. 2010. “Brighe, affanni, volgimenti di stato”: Le ricordanze quattrocentesche di Luca di Matteo di messer Luca dei Firidolfi da Panzano. Florence: SISMEL and Edizioni del Galluzzo. [Google Scholar]

- Occhioni, Nicola, ed. 1984. Il Processo per la Canonizazione di S. Nicola da Tolentino. Rome: École française de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Pasini, Alba, Vanessa Samantha Manzon, Xabier Gonzalez-Muro, and Emanuela Gualdi-Russo. 2018. Neurosurgery on a Pregnant Woman with Postmortem Fetal Extrusion: An Unusual Case from Medieval Italy. World Neurosurgery 113: 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzi, Candida. 1955. Un processo di stregoneria a Todi nel ‘400.’. Lares 21: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, Timothy W., and Anthony C. King. 1997. Excavations at the Mola Di Monte Gelato: A Roman and Medieval Settlement in South Etruria. Archaeological Monographs of the British School at Rome 11. London: British School at Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz-Esser, Romedio. 2014. Der Leichnam im Mittelalter: Einbalsamierung, Verbrennung und die kulturelle Konstruktion des toten Körpers. Eschbach: Jan Thorbecke Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Séguy, Isabelle, and Michel Signoli. 2008. Quand La Naissance Côtoie La Mort: Pratiques Funéraires et Religion Populaire En France Au Moyen Age et à l’époque Moderne. Città di Castello: Servei d’Investigacions Arqueològiques i Prehistòriques, pp. 497–512. [Google Scholar]

- Squires, Kristy E. 2014. Through the Flames of the Pyre: The continuing search for Anglo-Saxon infants and children. In Medieval Childhood: Archaeological Approaches. Edited by Katie A. Hemer and Dawn M. Hadley. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 114–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stensvold, Anne. 2015. A History of Pregnancy in Christianity: From Original Sin to Contemporary Abortion Debates. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, Norman, and Sethina Watson. 2006. Least of the laity: Minimum requirements for a medieval Christian. Journal Medieval History 32: 395–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, Timothy M., trans. 2007. The Rationale Divinorum Officiorum of William Durand of Mende: A New Translation of the Prologue and Book One. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tronti, Carlo. 2008. Famiglie signorili, cappelle private e insediamenti fortificati in Val di Sieve tra X e XII secolo: I casi di Monte di Croce e Montefiesole (Pontassieve, Firenze). In Chiese e insediamenti nei secoli di formazione dei paesaggi medievali della Toscana (V-X secolo), Atti del Seminario (San Giovanni d’Asso-Montisi, 2006). Edited by Stefano Campana, Cristina Felici, Riccardo Francovich and Fabio Gabbrielli. Quaderni del Dipartimento di Archeologia e Storia della Arti. Siena: Sezione Archeologia, Universitá di Siena, pp. 199–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Bochsler, Susi. 1997. Anthropologische Befunde zur Stellung von Frau und Kind in Mittelalter und Neuzeit. Soziobiologische und soziokulturelle Aspekte im Lichte der Archäologie, Geschichte, Volkskunde und Medizingeschichte. Bern: Berner Lehrmittel- und Medienverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Bochsler, Susi. 2002. Zur Stellung der Kinder zwischen Frühmittelalter und Neuzeit—Ein exemplarischer Exkurs. In Kinderwelten. Anthropologie—Geschichte—Kulturvergleich. Edited by Kurt W. Alt and Ariane Kemkes-Grottenthaler. Weimar: Böhlau, pp. 188–207. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, Brendon, and Susan Lalonde. 2008. An Early Medieval Settlement/Cemetery at Carrowkeel, Co. Galway. Journal Irish Archaeology 17: 57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zopfi, Laura Simone, Pariani Roberto Mella, Sguazza Emanuela, Porta Davide, and Cristina Cattaneo. 2010. Chiesa Vecchia di San Pietro all’Olmo (Cornaredo—MI)-Livelli del XVI Secolo. Un Singolare rito Funerario con Neonate Entro Coppi E Analisi Antropologica e Paleopatologica dei Resti Scheletrici. FastiOnline Documents and Research. Available online: http://www.fastionline.org/docs/FOLDER-it-2011–219.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).