Seng Zhao’s The Immutability of Things and Responses to It in the Late Ming Dynasty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

I once talked about this with a friend. This friend firmly disagreed. On the contrary, he regarded Master Zhao as “non-Buddhist” (waidao) with a one-sided view. He widely cited Buddhist doctrines to refute him. Even venerable Buddhist monks, such as Yunqi, Zibo, and several eminent masters, all strove to debate with him, but unexpectedly failed to refute his hypothesis.

The friend in question was none other than Zhencheng himself.予嘗與友人言之。其友殊不許可。反以肇公為一見外道。廣引教義以駁之。即法門老宿。如雲棲紫柏諸大老。皆力爭之。竟未迴其說。5

2. Context and Content of The Immutability of Things

3. Zhencheng’s Criticism and Proposition

(The Immutability of Things) furthermore said, “As (what has occurred in) ancient times cannot occur (again) in our time, and (what occurs) to-day cannot have occurred in ancient times, (or else) as the nature of each thing abides in (its period), what, then, is able to move freely to and fro (among the historical periods)?” (Liebenthal 1968, p. 52) Analysis: since Master Zhao intended to regard “each nature of thing abides” as “immutability”, this is no different from the notion that “(the conditioned things) cannot move to anywhere else from here” in the Small Vehicle (Hīnayāna). Next, (The Immutability of Things) said, “Therefore, when he (the Sage) has in mind the final truth (paramārtha-satya), he says that (things) do not move; when he teaches conventional truth (saṃvṛti-satya), he says that everything flows” (Liebenthal 1968, p. 50). This is regarding the ultimate truth as “immutability”, while not showing the characteristic of the ultimate truth. If (Master Zhao) used “the nature of each thing abides” as the characteristic of the ultimate truth, why did (he) not (state that) there is nothing mutable because of “emptiness of nature”? It is only in the treatise of On Śūnyatā that the meaning of “emptiness of nature” appears. (By contrast, in The Immutability of Things, Master Zhao) restricts “immutability” to the realm of the conventional truth.

In this passage, although Chengguan initially associates Seng Zhao’s account of “the nature of each thing abides” with the unenlightened teachings of Hīnayāna, he then acknowledges that Seng Zhao’s dichotomic explanation of “immutability” and “mutability” accords with twofold-truth teaching.23 However, Zhencheng cites only the first part of this paragraph in his analysis of The Immutability of Things: “[T]his is to say that the nature of each thing abides in one time period, without the possibility to move freely to and fro (among the temporal periods). This is the real meaning of Master Zhao’s Immutability of Things.”24 Therefore, according to Zhencheng’s reinterpretation of Chengguan’s analysis, Seng Zhao’s proposition is “immutability” and his main proof of it is “nature abides” (xingzhu 性住), as is evident in his assertion that “the abiding nature is immutable 性住不遷”. This brief statement is the principal focus of Zhencheng’s critique of The Immutability of Things in A Logical Investigation. Thereafter, he presents his own “correct” proof of the “immutability” proposition by declaring that “the emptiness of nature is immutable”.25下文又云。若古不至今。今亦不至古。事各性住於一世。有何物而可去來。釋曰。觀肇公意既以物各性住而爲不遷。則濫小乘無容從此轉至餘方。下論云。故談眞有不遷之稱。導物有流動之説。此則以眞諦爲不遷。而不顯眞諦之相。若但用於物各性住爲眞諦相。寧非性空無可遷也。不眞空義方顯性空義。約俗諦爲不遷耳。22

- The proposition that past things do not pass to the present does not prove immutability or permanence but rather “impermanence”

Now he (Master Zhao) says that past things abide in the past, while present things abide in the present. If so, they are conditional dharmas, falling in (the realm of) moving to and fro. Since (such a “thing”) falls under the three time periods (i.e., past, present, and future), it is invalid for (Master Zhao) to call it “immutability”. Thus, the Nirvāṇa sūtra claimed that the dharma that permanently abides is not contained in the three times, and that the Buddha’s dharma-body is not contained in the three times. It is not contained in the three times, so it is called “permanent”. On the contrary, what is contained in the three times must be impermanent. Who can claim what is impermanent is immutable?

今其言曰。昔物住昔。今物住今。是有為法。墮去來。今既墮三世而曰不遷。未之有也。故涅槃云。常住之法。三世不攝。如來法身。非三世攝。故名為常。反顯三世攝者必無常也。誰謂無常而不遷乎。31

Question: How (do you) know that different things are all impermanent?

Answer: This rests on two assumptions. The first is the teaching of the sage. The holy practices in the Nirvāṇa sūtra extensively explain that different things are all impermanent. The second is logical inference. There are no differences among the (different things’) natures of emptiness, so (the emptiness) is named “permanence”. Every form or vessel/tool is different from every other, so they are all “impermanent”. To discuss this difference in terms of time, […] (things) sometimes exist but sometimes do not, so they are impermanent. To discuss it in terms of space, […] (things) exist somewhere but not elsewhere, so they are called impermanent.

問。何知異物皆無常耶。

As any concrete thing can occupy only one point in time and space, it will become another thing when the time and space change, which leads Zhencheng to the inevitable conclusion that things in the past and things in the present are definitely different. Moreover, this difference proves that the nature of any concrete thing cannot be permanent, in the sense of retaining an inherently consistent self. On the other hand, the nature of emptiness—the ultimate and universal truth in Mahāyāna Buddhism—never differs in any time or place, so it is the only “thing” that exists permanently. Therefore, Zhencheng criticizes Seng Zhao for terming conventional things—that is, things with concrete characteristics—"immutable” (a synonym for “permanent”, according to Zhencheng).答曰。據二量故。一聖言量。涅槃聖行廣說異物皆無常故。二理量。如空不異則名為常。形器異故諸皆無常。竪論異者。[…]時乎而有。時乎而無。故為無常。若橫論者。[…]有處而有。有處而無。故名無常。32

- b.

- The notion that past things existed previously and do not exist now is an extension of the illusion of existence and non-existence

Master Zhao’s “immutability”, generally speaking, displays four assumptions—namely “existence”, “non-existence”, “sameness”, and “difference”. “Looking for a past thing in the time point where it once was, the thing never fails to exist in the past.” This is the assumption of “existence”. “Looking for a past thing in the time point of the present, this thing has never existed in the present.” This is the assumption of “non-existence”. “The past thing was in the past, while the present thing is in the present.” This is the assumption of “difference”. Only the assumption of “sameness” is absent. All four of these assumptions can contaminate prajñā teaching. [If a theory] includes any one of them, it violates prajñā teaching. So how could there be any “immutability”?

There are many contrasting interpretations of the “four assumptions” across several Buddhist sūtras, and both “existence and non-existence” and “sameness and difference” were familiar concepts in various Chinese Buddhist schools in the late Ming period, so it is impossible to determine which of countless potential sources inspired Zhencheng to couch his criticism in these terms. That said, he mentions that the “four assumptions” can contaminate prajñā teaching, so we may at least trace the concept back to a basic principle in one of prajñā Buddhism’s most important sūtras— the “eight negations of the Middle Way” (babu zhongdao 八不中道) in the MMK. These “eight negations” are presented as four pairs of concepts: non-ceasing and non-arising; non-annihilation and non-permanence; non-identity and non-difference; and non-appearance and non-disappearance.37 The opposites of three of these pairs—ceasing and arising 生滅, annihilation and permanence 斷常, and appearance and disappearance 去來—relate to existence (that is, “existence” and “non-existence”), while the opposite of the fourth—identity and difference 一異—relates to the relationship between two things. In essence, all eight negations emphasize the importance of avoiding extreme views when exploring things’ existence as well as their relationships with other things. Zhencheng clearly believed that he could criticize The Immutability of Things on the basis of the “four assumptions” as Seng Zhao had been viewed as an authority on prajñā.然肇公不遷。所以總之。不出四計。謂有無一異。‘求向物於向。於向未甞無。’是有計。‘責向物於今。於今未甞有。’是無計。‘昔物自在昔。今物自在今。’是異計。唯闕一計耳。四計乃般若之大病。有一於此則與般若之理背矣。尚何不遷哉。36

- c.

- If past causes never cease or disappear (lit. transform), it is impossible for all beings to attain Buddha-hood, and there will never be a point of time when through the cultivation of causes one achieves the results38

“Permanence” has two meanings. One is the “immutable continuity”, meaning that thusness (tathatā) is immutable. The Lengyan jing (Śūraṃgama-sūtra) says, in the real and eternal nature, (if people) look for enlightenment and illusion, birth and death, leaving and coming, (they) obtain nothing. The second is the “successive continuity”, meaning that the results of karma are never lost. The Huayan jing (Buddhâvataṃsaka-sūtra) says that the essence of the cause disintegrates in every instant but accumulates successively, and the result never loses the form (upon which it acts). The poetic verse says that it is clear that the cause disintegrates and the result then aggregates. Because of the permeating power of the similar and immediately antecedent conditions (samanantara-pratyaya) stored in the eight consciousnesses, when the preceding instant of thought ceases, it permeates the subsequent instant of thought. Even when the annihilation at the end of an age burns brightly, the results of karma are not lost. Therefore, it is called the “successive continuity”. Thus, although (Master Zhao said that “immutability”) is “clear”, it belongs to the conditional and changing dharmas. Master Zhao used it to prove that thusness is immutable. This goes against the teaching.

In this lengthy paragraph, Zhencheng not only distinguishes between two distinct kinds of “permanence”—the “immutable continuity” and the “successive continuity”—but also draws attention to “thusness” and to the conditional and changing world that is restricted by the law of cause and result. According to his analysis, Seng Zhao misunderstood the “permanence” of the law of cause and result (or “successive continuity”) on the grounds that this relates only to never-ending karma, not to unceasing past causes. In addition, he suggests that the law of cause and result cannot be used to demonstrate “immutability” because only ultimate thusness (or “immutable continuity”) is permanently immutable, while the law of cause and result applies only to dependently arisen things in the “three time periods” (that is, the phenomenal world).常有二義。一凝然常。真如不遷之義也。楞嚴云。性真常中。求於迷悟生死去來。了無所得。二相續常。業果不失之謂也。華嚴云。因自相剎那壞而次第集果不失相。偈云。因壞果集皆能了。以八識藏中等無間緣熏習力故。前念滅時熏起後念。雖劫火洞然而業果不失也。故謂之相續常。則雖曰湛然乃屬有為遷變之法。肇師以證真如不遷。於義左矣。39

The prajñā (sūtras) clarify the forms and manifest emptiness, therefore they state that “dharmas do not leave or come”, which means that if one seeks the characteristics of leaving and coming, one cannot grasp them. Thus, prajñā does not manifest permanence. The nirvāṇa (sūtras) directly reveal the real nature, so they claim that “permanent abiding is beyond cause and result” […] The essence of nirvāṇa that abides permanently, and is not empty, is the Buddha-nature and the true self in the womb of the Tathāgata, which is firm and immutable, thus not impermanent. It truly exists with an essence, so it is not empty. The prajñā sūtras do not mention this.

Zhencheng uses bore (般若, prajñā) when discussing the teachings of the Indian Madhyamaka 中觀派 tradition and the indigenous Chinese Sanlun school 三論宗, and niepan (涅槃, nirvāṇa) in reference to theories that largely conform to the doctrines of the Huayan school (i.e., all things originate from thusness). One of the main points of contention between these two traditions is that while niepan scriptures acknowledge the eternal existence of the Buddha-nature in all sentient beings, bore texts tend to negate any eternal essence, including that of the Buddha-nature.43 Therefore, it seems highly likely that Zhencheng knew that Seng Zhao never intended to equate “immutability” with any kind of essential nature of things, as “the sūtras of prajñā do not mention this”. Nevertheless, he criticizes The Immutability of Things on the basis of Huayan reasoning. This may be explained by the fact that Chinese Buddhist thought became preoccupied with niepan thinking after the Sanlun school started to decline at the end of the Tang dynasty (618–907). Indeed, even the Tiantai school 天台宗, which claimed to preserve Sanlun teachings, adopted the theory of intrinsic inclusiveness (xing ju 性具)—that is, the Buddha-nature includes both good and evil—as one of its central tenets.般若蕩相名空。故說法無去來。謂求去來相不可得。故非謂顯常也。涅槃直示實性。故說常住非因果[…]其涅槃常住不空之體是如來藏佛性真我。堅凝不變。則非無常。真實有體。則非空也。般若經中言未及此。42

4. Contemporary Responses to Zhencheng’s Criticism of Seng Zhao

4.1. Deqing

Suddenly, the wind blew the trees in the courtyard, and the fallen leaves flew in the air. But I did not see any leaf moving. Ah, there is faith in “the raging storm that uproots mountains in fact is calm”. Then (I) went to the toilet to relieve myself, but could not see any characteristic of “flowing”. (I) exclaimed, “It is true, indeed! The two rivers of China (i.e., the Yangzi and the Yellow River) rush along and yet do not flow.”

Clearly, Deqing believed that personally experiencing immutability amid conditional things that, at first glance, seem to be changing rapidly is a far more persuasive demonstration of the concept than any amount of rational reasoning based on the study of scriptures. Although he never belittled doctrinal study, he always insisted it was supplementary to meditation. For example, his treatises on the subject of Yogācāra philosophy include such caveats as:忽風吹庭樹。落葉飛空。則見葉葉不動。信乎。旋嵐偃嶽而常靜也。及登廁去溺。則不見流相。歎曰。誠哉。江河競注而不流也。51

(Those who read this) should just enlighten their minds with the help of this treatise, instead of specifically differentiating the names and characteristics.

正要因此悟心。不是専爲分别名相也。52

Those who practice meditation do not need to read Buddhist doctrines widely. With this treatise, they can verify (their state of) mind in order to prove the depth of their enlightenment.

Deqing succeeded in assimilating Yogācāra analysis of consciousness with the Chan theory of the one mind. This not only simplified the highly complicated Yogācāra teachings, but also provided much-needed guidance for Chan practitioners as they attempted to enlighten their minds in everyday life.而参禅之士不假广涉教義。即此可以印心。以証悟入之浅深。53

4.2. Haiyin

(Master Zhao uses) “immutability” to denote conventional things, and he takes the unreal for the real. Therefore, it is the thing that is immutable, rather than the truth. As things are changing (according to regular perception), (Master Zhao) now demonstrates that immutability is the most profound. If (he regards) the truth as immutable, it does not deserve mention […] Moreover, Master Zhao clearly points out that “immutability” refers to things, but you (i.e., Zhencheng) falsify him by referring to the truth.

Haiyin repeatedly emphasizes that Seng Zhao views conventional things, not the truth, as immutable. Zhencheng then confirms this interpretation in his response to Haiyin’s letter: “Great Master Haiyin wisely wrote thousands of words in the letter, but his main point is that Master Zhao proposed immutability based on conventional things, rather than proved the immutability of thusness.”55 Haiyin comes close to identifying the crux of Seng Zhao and Zhencheng’s disagreement on the basis of the twofold-truth theory: that is, is it acceptable to use “immutability” in reference to conventional/phenomenal things (i.e., the opposite of “mutability”) or is it only ever applicable to the ultimate truth of emptiness (or thusness, Buddha-nature or one mind)? However, his analysis is constrained by the strict structural separation of the conventional and ultimate truths in Huayan philosophy, which prevents a Madhyamaka-inspired exploration of the relationship between these two truths. Zhencheng seizes on this limitation to rebut Haiyin’s critique.且以不遷當俗。不真為真。由是觀之。是物不遷。非真不遷也。以其物有遷變。故今示之以不遷為妙。若真不遷。又何足云[…]且肇公明指不遷在物。而足下以真冤之。54

4.3. Huanyou

- Challenge the application of the twofold-truth theory and Zhencheng’s interpretation of “immutability”

Although (Chengguan) improperly used the “ultimate truth” and “conventional truth” to prove (Seng Zhao’s) intention in The Immutability of Things, he did not incorrectly interpret the word “mutability” as “disappear” (mie 滅) or “transform” (hua 化). Now, Kongyin (i.e., Zhencheng) is different. He definitively regards “mutability” as “disappearing” and “transforming” […] (Zhencheng) misrepresents the statement “existing in the past while not existing in the present” as the dharma of impermanence and hence a demonstration of immutability. But this demonstration is invalid, because it is redundant. This is because the “immutability of things” refers only to “not leaving or coming”, and the coexistence of movement and stillness, not to impermanent arising and ceasing.

Here, Huanyou’s argument rests on careful consideration of three seemingly identical—but actually subtly different—terms. As he points out, qian 遷, the core concept in The Immutability of Things, relates to the actions of phenomenal things, whereas mie 滅 and hua化, in the Buddhist discourse, are always linked with the impermanence of conventional things. By distinguishing “mutability” from the notions of “disappearing” and “transforming”, Huanyou narrows The Immutability of Things’ scope to “movement and stillness”, which leads to the accusation that Zhencheng is guilty of overinterpretation by equating “immutability” with “permanence”. While Seng Zhao uses the concept of “nature abides” to explain the stillness of phenomenal things—which was later negated as they acquired self-nature—Zhencheng attempts to demonstrate that phenomenal things are impermanent and lack self-nature. These two propositions relate to different topics in different realms, so they are not actually contradictory, but Zhencheng’s criticism is invalid and unjustified, because he misunderstands The Immutability of Things’ core concept.雖以真諦俗諦而誤證物不遷歸旨不合。未謬解遷字為滅化義也。今空印則不然。務以論題遷字斷斷乎為滅也。化也[…]曲引向有今無為無常法證不遷者。此證不成。乃贅且剩也。葢物不遷唯指無去來,即動靜。非以無常生滅為論也。60

- b.

- Challenge Zhencheng’s interpretation of “past causes never disappear”

- c.

- Prove that Seng Zhao’s assertion that “each nature of the thing abides in one time period” conforms to the “eight negations of the Middle Way”

“Time period” means “at the time of (a thing)”. Thus, a time period cannot exist without the thing, and a thing cannot be separated from the time period. As such, (we) know that the time exists only if the thing exists, and if the time vanishes, the thing would also be extinguished. So why should (we) not say that “nature abides in one time period”?

As discussed earlier, Chapter 2 of the MMK divides the concept of “movement” into three distinct elements: the mover, the moving time, and the act of moving. Huanyou mirrors this technique by dividing “nature abides in one time period” into the thing, the abiding time, and the act of abiding. Then, in another nod to Nāgārjuna, he explains that the thing and the abiding time depend on each other. Furthermore, he confirms that the “nature abides in one time period” concept accords with the “eight negations” by addressing each of the latter in turn: first, nothing comes from outside of a time period, so the concept conforms to “non-appearance” (bu lai 不來); second, nothing is able to free itself from the restriction of a time period, so it also conforms to “non-disappearance” (bu qu 不去); third, as the time and the thing are interdependent, they are different yet linked, so their relationship accords with both “non-identity” (bu yi 不一) and “non-difference” (bu yi 不異); fourth, as the time and the thing are inextricably bound to each other, neither can arise independently or last permanently by itself, and neither can be destroyed or cease if the other continues to exist, so their existence conforms to “non-arising” (bu sheng 不生), “non-ceasing” (bu mie 不滅), “non-annihilation” (bu duan 不斷), and “non-permanence” (bu chang 不常). According to Huanyou, the essence of these eight negations is inherently coherent as they are rooted in the “one reality of the uncreated” (wusheng yishi 無生一實).64夫世者當時之謂。由是知世不能外物。物又安能離世。所以知物在時亦在。時亡則物亦亡。安得不可謂性住一世耶。63

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary Sources and Collections

Anchō (安澄). Chūron soki (中論疏記). Available online: 21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/ddb-sat2.php?mode=detail&useid=2255_ (accessed on 1 December 2019).CBETA (Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association). Available online: https://www.cbeta.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2019).Chengguan (澄觀). Da fang guang fo huayan jing suishu yanyi chao (大方廣佛華嚴經隨疏演義鈔). Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1736 (accessed on 1 December 2019).Deqing (德清). Bashi guiju tongshuo (八識規矩通說). Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/X0893 (accessed on 15 September 2020).Deqing (德清). Zhaolun lüezhu (肇論略註). Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/X0873 (accessed on 1 December 2019).Huanyou (幻有). Longchi Huanyou chanshi yulu (龍池幻有禪師語錄). Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/L1637 (accessed on 1 December 2019).Hui Jiao (慧皎). Gaoseng zhuan (高僧傳). Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/T2059 (accessed on 15 September 2020).Nāgārjuna. Madhyamaka-kārikā. Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1564 (accessed on 1 December 2019).SAT (SAT Daizōkyō Text Database). Available online: https://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/index_en.html (accessed on 1 December 2019).Seng Zhao (僧肇). Zhao lun (肇論). Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1858 (accessed on 1 December 2019).Vasubandhu. Abhidharmakośa-bhāṣya. Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1558 (accessed on 15 September 2020).Yuan Kang (元康). Zhaolun shu (肇論疏). Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1859 (accessed on 15 September 2020).Zhencheng (鎮澄). Wu bu qian zheng liang lun (物不遷正量論). Available online: cbetaonline.cn/zh/X0879 (accessed on 1 December 2019).Zhuangzi (莊子). Available online: ctext.org/Zhuangzi (accessed on 1 December 2019).Secondary Sources

- Jiang, Canteng. 2006. Wan-Ming Fojiao Gaige Shi 晚明佛教改革史 [History of the Buddhist Reformation in the Late Ming]. Guilin: Guangxi Shifan Daxue Chuban She. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Wu. 2008. Enlightenment in Dispute: The Reinvention of Chan Buddhism in Seventeenth-Century China. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kalupahana, David J. 1986. Nāgārjuna: The Philosophy of the Middle Way. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Man, and Bart Dessein. 2015. Aurelius Augustinus and Seng Zhao on “Time”: An Interpretation of the Confessions and the Zhao Lun. Philosophy East and West 65: 157–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenthal, Walter. 1968. Chao Lun: The Treatises of Seng-Chao. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Richard H. 1958–1959. Mysticism and Logic in Seng-chao’s Thought. Philosophy East and West 8: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Yan. 2006. Ming-Mo Fojiao Yanjiu 明末佛教研究 [Research on Late Ming Buddhism]. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Yongtong. 1955. Han Wei Liang Jin Nanbeichao Fojiaoshi 漢魏两晋南北朝佛教史 [History of Buddhism in the Han, Wei, Eastern and Western Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Zenryū, ed. 1955. Jōron Kenkyū 肇論研究 [Studies of the Zhao Lun]. Kyōto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Rudolf G. 2000. The Craft of a Chinese Commentator: Wang Bi on the Laozi. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wayman, Alex. 1999. A Millennium of Buddhist Logic. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 1972. The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China. Leiden: E. J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | According to Robinson (1958–1959, pp. 99–120), “Tsukamoto Zenryū […] establishes these dates as more probable than the traditional ones (384–414).” |

| 2 | Tsukamoto’s (1955) and Walter Liebenthal’s (1968) Japanese and English translations of the Zhao lun prompted discussions on some fundamental aspects of Seng Zhao’s treatises, primarily their Neo-Daoist elements (Tsukamoto 1955, pp. 113–65) and mystical tendencies (Liebenthal 1968, pp. 26–27). Neither author cast any doubt on the widely accepted view that the Zhao lun played a pivotal role in the history of Chinese Buddhism. |

| 3 | Here, “late Ming dynasty” roughly equates to the reign of Emperor Wanli 萬曆帝 (1572–1620). Sheng’s (2006, p. 3) definition of “late Ming” is slightly more specific: 1573–1619. |

| 4 | Yixue 義學 (“doctrinal study”) generally refers to the systematic, scholarly study of a particular doctrine of Buddhism, such as Huayan 華嚴宗, Yogācāra, and Tiantai 天台宗, in contrast to the meditation practices of Chan 禪 Buddhism. |

| 5 | CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 873, p. 336c22–24; R96, p. 590b7–9; Z 2:1, p. 295d7–9. The meaning of the phrase yijian waidao 一見外道 is unclear, not least because it does not appear in A Logical Investigation itself. Deqing most likely used it to summarize Zhencheng’s opinion that The Immutability of Things is biased and therefore violates the core teachings of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Jian 見 equates to dŗṣţi—a one-sided, partial, prejudiced, limited idea, opinion, or point of view. |

| 6 | CBETA 2020.Q1, T50, no. 2059, p. 365a9–22. |

| 7 | CBETA 2019.Q3, T45, no. 1858, p. 157a20–21. |

| 8 | Seng Zhao intensively summarized and evaluated these three schools in the treatise On Śūnyatā (Bu zhen kong lun 不真空論). Unfortunately, very few of the schools’ own texts survive, although Tang (1955) and Liebenthal (1968) were able to provide some valuable insights into their thinking after careful study of this scant source material. Zürcher (1972) then built on Tang and Liebenthal’s efforts, compared the ideas of the Buddhist schools with those of the Neo-Daoists, and pointed out the Buddhists’ limitations in terms of their understanding of the concept of “emptiness” as found in the Mahāyāna sūtras. First, he suggested that proponents of xinwu yi 心無義 recognized “matter” (rūpa, se 色) as a real entity endowed with objective existence, whereas the term “emptiness” refers to the mind of the sage that is “non-existence” (wu 無) in so far as it is free from all conscious thought, desire, and attachment. This theory seems to be related to a Neo-Daoist trend known as “the exaltation of existence” (chong you 崇有), which concerns the inner “emptiness” and “mental immunity” of the sage in his contact with the world of “existence” (you 有) (pp. 101–2). Second, Zürcher argued that advocates of jise yi 即色義 held that “matter” exists ‘as such (i.e., it lacks any permanent substrate, any sustaining or creative principle that “causes matter to be matter”). This comprised a Buddhist elaboration of Xiang Xiu 向秀 and Guo Xiang 郭象’s theory that all things spontaneously exist by themselves, and that there is no creative power or a permanent substance behind things. Seng Zhao severely criticized this notion on the basis that it dealt only with the conditional and causal nature of all phenomena and failed to appreciate the ultimate truth that conditionality and causality themselves are mere names without any underlying reality (pp. 123–24). Third, Zürcher pointed out that members of the benwu yi 本無義 school considered benwu as the true nature of all phenomena—an absolute that underlies the worldly truth. This notion comes nearest to the true meaning of the Prajñāpāramitā doctrine as revealed by Kumārajīva, but it seems to conflate the Daoist idealized tohu-va-bohu and the Mahāyāna concept of the “nature of all dharmas” (pp. 191–92). |

| 9 | 吾解不謝子。辭當相挹。 CBETA 2019.Q3, T50, no. 2059, p. 365a25–26. |

| 10 | 而言物不遷論者。元康師云。莊子云。凡有貌像色聲者。皆物也。公孫龍子名實論云。天與地。其所産焉物也。 http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/T2255_.65.0112b18:0112b20.cit. |

| 11 | Laozi 21.2: “The Way as a thing is vague, ah, diffuse, ah” (道之爲物, 惟恍惟惚). Laozi 25.1: “There is a thing that completes out of the diffuse. It is born before Heaven and Earth […] I do not know its name. Therefore, forced, I give it the style ‘dao’” (有物混成, 先天地生 […] 吾不知其名, 字之曰道). Translations by Wagner (2000, pp. 297, 283). |

| 12 | 審乎無假, 而不與物遷。 https://ctext.org/zhuangzi/seal-of-virtue-complete#n2748. |

| 13 | For a comparative study of Buddhist and Christian philosophies relating to the concept of “time”, see Li and Dessein (2015). |

| 14 | 既知往物而不來, 而謂今物而可往. We modified Liebenthal’s (1968, p. 47) translation by deleting his supplementary bracketed information and rendering the original Chinese more literally. Liebenthal added the dimension of space in his understanding of the relationship between things in the past and present; however, we believe it is unnecessary to include this additional information. |

| 15 | 往物既不來, 今物何所往? Liebenthal (1968, p. 47). |

| 16 | 不動, 故各性住於一世. Liebenthal (1968, p. 51). Xing 性 (“nature”) is an abbreviation of wuxing物性 (“nature of a thing”), mentioned above, or shixing 事性 (“nature of an event”), mentioned below, and therefore should be understood as the thing or event itself, rather than any essential or substantial “nature” of it. |

| 17 | 事各性住於一世. Liebenthal (1968, p. 52). Once again, we have modified Liebenthal’s translation for the reason given in note 14. |

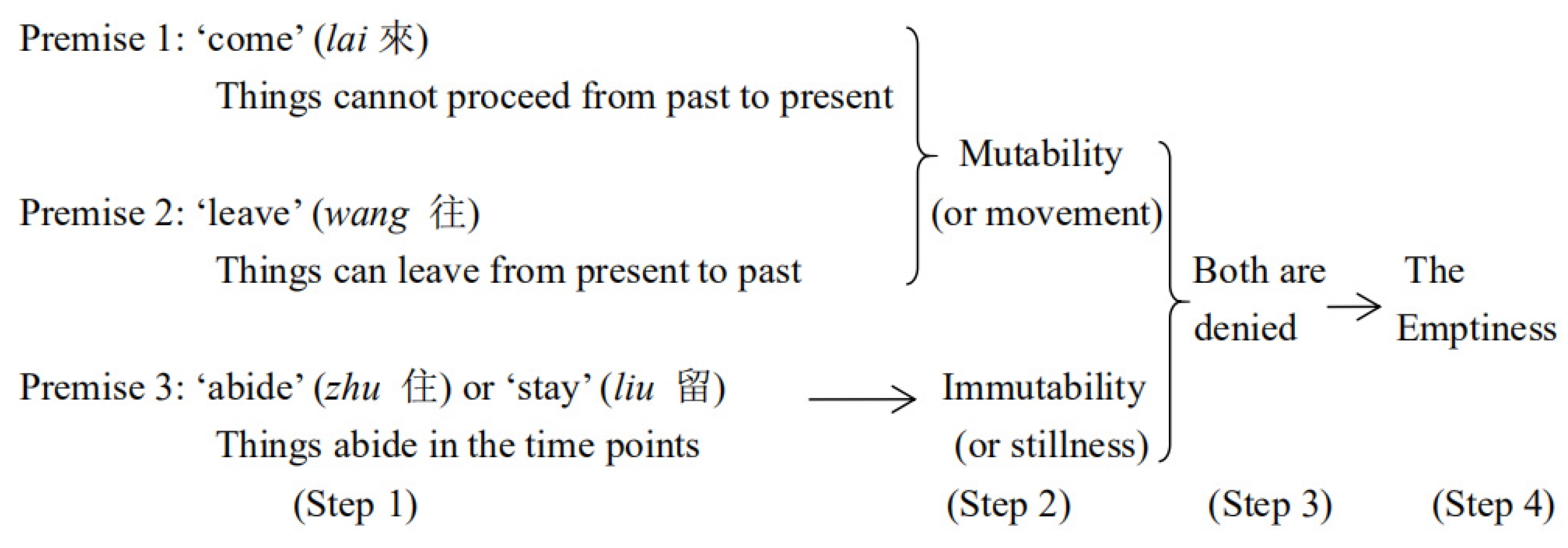

| 18 | 不遷, 故雖往而常靜; 不住, 故雖靜而常往。 雖靜而常往, 故往而弗遷; 雖往而常靜, 故靜而弗留矣. Liebenthal (1968, p. 49) came close to rewriting this section, so we have used our own, more literal translation. In The Immutability of Things, qian 遷 (“mutability”) is synonymous with dong 動 (“movement”), lai 來 (“come”), and wang 往 (“leave”); its antonym, buqian 不遷 (“immutability”), is synonymous with jing 静 (“stillness”), zhu 住 (“abide”), and liu 留 (“stay”). |

| 19 | 凡有起於虛, 動起於靜, 故萬物雖並動作, 卒復歸於虛靜, 是物之極復也. This is Wang Bi’s reinterpretation of Laozi 16.3: 致虛極, 守靜篤, 萬物並作, 吾以觀復. According to Wagner (2000, p. 277), Wang Bi made a small alteration that had a substantial impact on the overall meaning: (1) it becomes clear that the “simultaneous action” of the ten thousand kinds of entities stands in contrast to emptiness (xu 虚) and stillness (jing 静); and (2) the entities’ emptiness and stillness are not immediately apparent in their presence, but rather perceived by the philosophical eye as their ultimate aim. Wagner’s analysis supports our proposal that Neo-Daoist metaphysical scholars used “movement and stillness” to denote “roots and branches” (ben mo本末) and “essence and function” (ti yong 體用), and to emphasize the veracity of sagely cognition. |

| 20 | Li and Dessein (2015, p. 171) liken this to a movie: “every frame of a movie stays in its position without leaving, but when cast on a screen, the spectator has the impression of continuity”. |

| 21 | Buddhist logic (hetu-vidyā, yinming 因明) was one of the five branches of science (pañca-vidyā, wu ming 五明) in ancient India. Although generally regarded as a philosophical method rather than a distinct Buddhist school, it has been widely used in the Yogācāra tradition. |

| 22 | CBETA 2019.Q3, T36, no. 1736, p. 239b23–c1. Chengguan mentions the teaching of the Small Vehicle, which can be found in Chapter 4 of the Abhidharmakośa-bhāṣya during a discussion of the concept of karman (ye 業). The exposition of the verse states, “(The conditioned phenomena) are produced here and are destroyed right here (i.e., they just exist for an instant). They cannot move to anywhere else from here” 若此處生即此處滅。無容從此轉至余方; CBETA 2020.Q1, T29, no. 1558, p. 67c14). It affirms the non-continuity of the body (shen 身) on the timeline, thus denying the body’s motion. On the surface, this is similar to Seng Zhao’s explanation of “nature abides” (xingzhu 性住), but the Abhidharmakośa-bhāṣya espouses the substantiality of things and the true existence of past, present, and future, whereas Seng Zhao’s explanation stands on the basis of emptiness in the nature of things. |

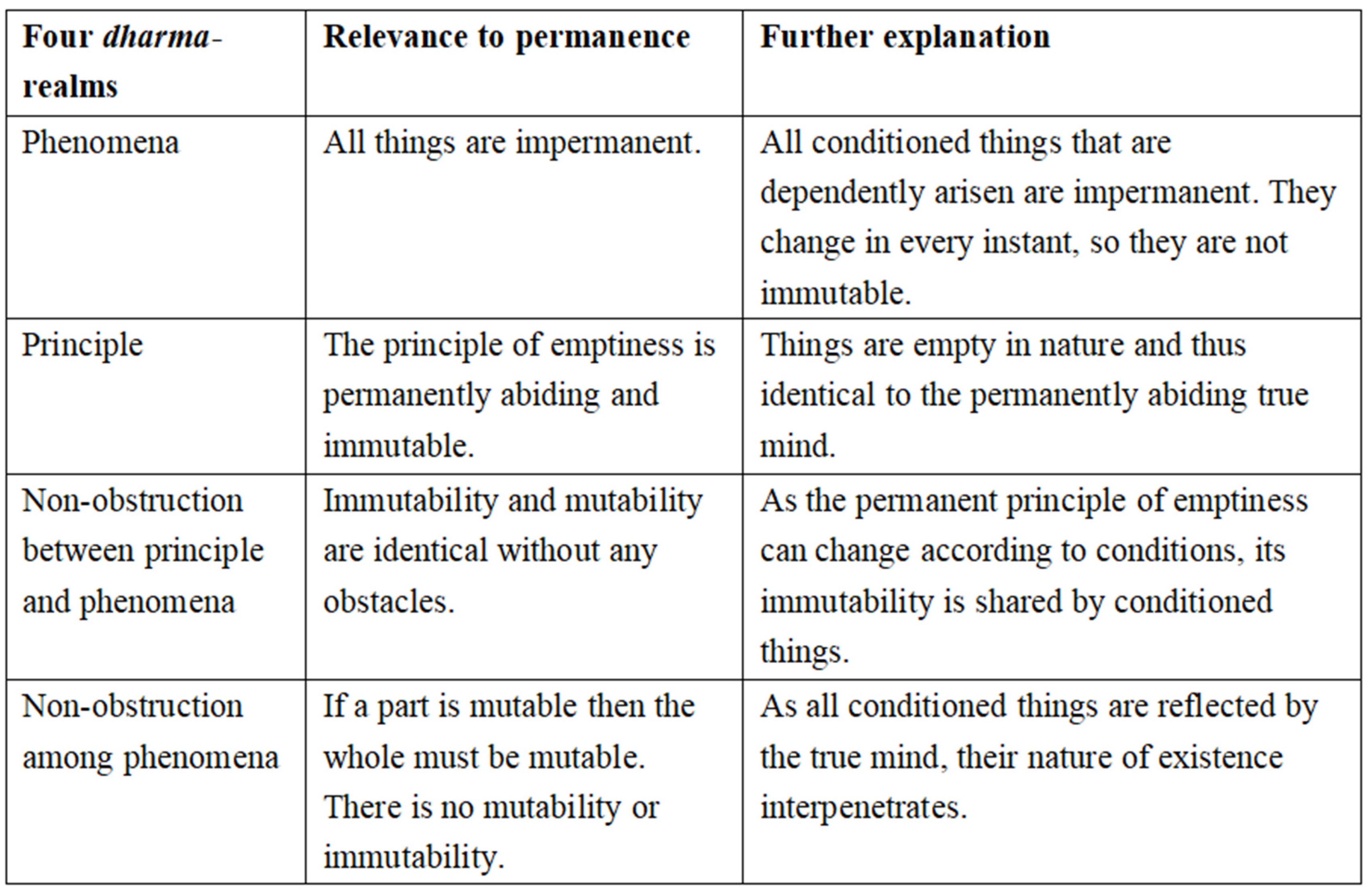

| 23 | Basically, in Buddhism, the twofold-truth (satya-dvaya) encompasses the ultimate truth (paramârtha-satya, zhendi 真諦) and the conventional truth (saṃvṛti-satya, sudi 俗諦), although there are very different interpretations of these two truths in the sūtras and śāstras of the Mahāyāna and Hīnayāna schools. For example, in the Madhyamaka philosophy of the Mahāyāna tradition, the twofold-truth denotes emptiness in the self-nature of things and phenomenal illusions on the basis of the theory of dependent arising; however, the Yogācāra school links the twofold-truth with the theory of “three natures” and regards the perfectly accomplished nature, which is perceived in a non-discriminating mode of cognition, as the ultimate truth. Meanwhile, in China, the Huayan school regards “principle” (li 理) and “phenomena” (shi 事), based on the division of the “four dharma-realms”, as the ultimate and conventional truths, respectively; by contrast, in the Chan school, the ultimate truth is always related to the functioning of the mind (xin 心). |

| 24 | 是謂物各性住於一世不相往來。此肇公不遷之本旨也。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 913c20v21; R97, p. 731b8–9; Z 2:2, p. 366b8–9. |

| 25 | 性空不遷。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, pp. 913a09–19b22; R97, pp. 730a03–43a04; Z 2:2, pp. 365c03–72a04; CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, pp. 919c04–26a22; R97, pp. 743a06–56a11; Z 2:2, pp. 372a06–78c11. |

| 26 | The three-part syllogism and other Buddhist logic techniques entered the mainstream and were exported to China no later than the lifetime of the Yogācāra philosopher Dignāga (Chen Na 陳那). The “thesis” may be either one’s own notion or that of an opponent; the “reason” is used to prove the thesis; and the “example” is usually well known as well as relevant to the reason. See Wayman (1999, pp. 10–11). |

| 27 | 言宗似者。即所謂不釋動以求靜。必求靜於諸動; 言因非者。修多羅以諸法性空為不遷。肇公以物各性住為不遷。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 913a15–21; R97, p. 730a9–15; Z 2:2, p. 365c9–15. |

| 28 | 肇公以昔物不滅。性住於昔。而說不遷。則於大乘性空之義背矣。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 914c3–4; R97, p. 733a9–10; Z 2:2, p. 367a9–10. |

| 29 | Generally, there are three means of valid cognition in Buddhist logic: “direct perception” (pratyakṣa, xianliang 現量)—what is not out of sight, not already inferred and not to be inferred, and non-delusory; “inference” (anumāna, biliang 比量)—what is addressed with the inferable or what has already been inferred, and the sense object that is inferable; and “argument of authority” (āpta-āgama, shengjiao liang 聖教量)—what was expressed by the Omniscient One, or heard from him, or is therewith a consistent doctrine. For more detailed information, see Wayman (1999, pp. 12–26). |

| 30 | 今以異物異世以釋不遷。教理俱違。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 914a24–b1; R97, p. 732a18–1: Z 2:2, p. 366c18–1. |

| 31 | CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 914b2–6; R97, p. 732b2–6; Z 2:2, p. 366d2–6. |

| 32 | CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 918c13–21; R97, p. 741b1–9; Z 2:2, p. 371b1–9. |

| 33 | 求向物於向。於向未甞無。責向物於今。於今未甞有。 Liebenthal (1968, pp. 47–48). |

| 34 | 執有為有。是為常有。不知緣性之本空。計無為無。是為斷無。不識無性之緣起。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 914a12–13; R97, p. 732a6–7; Z 2:2, p. 366c6–7. |

| 35 | 性空性住如明與暗。敵體相違矣。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 914a19–20; R97, p. 732a13–14; Z 2:2, p. 366c13–14. |

| 36 | CBETA 2020.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 916a22-b2; R97, p. 736a16-2; Z 2:2, p. 368c16-2. |

| 37 | 不生不滅。不断不常。不一不異。不去不來。 For a detailed explanation, see Kalupahana (1986, p. 101). |

| 38 | 若昔因不滅不化者。則眾生永無成佛之理。修因永無得果之期。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 914c10–12; R97, p. 733a16–18; Z 2:2, p. 367a16–18. |

| 39 | CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 915a10–16; R97, p. 734a4–10; Z 2:2, p. 367c4–10. |

| 40 | In about 416–418 CE, Buddhabhadra 佛陀跋陀羅 and Faxian 法顯 translated part of this sūtra under the title Dabannihuan jing 大般泥洹經. Some years later, in Liangzhou 凉州, Dharmakṣema 曇無讖 translated more of the text in the Dabanniepan jing 大般涅槃經 or ‘Northern edition of the Mahāparinirvāṇa sūtra’ 北本涅槃經. See cbetaonline.cn/zh/T0007 and cbetaonline.cn/zh/T0374. |

| 41 | 一切眾生悉有佛性。如來常住無有變易。 CBETA 2020.Q1, T12, no. 374, p. 522c24. |

| 42 | CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 915b21–22; R97, p. 735a3–4; Z 2:2, p. 368a3–4. |

| 43 | See also the DDB entries on 空宗 and 涅槃宗: http://www.buddhism-dict.net/cgi-bin/xpr-ddb.pl?q=%E7%A9%BA%E5%AE%97; http://www.buddhism-dict.net/cgi-bin/xpr-ddb.pl?q=%E6%B6%85%E6%A7%83%E5%AE%97. |

| 44 | CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 916b24–c14; R97, p. 737a6–2; Z 2:2, p. 369a6–2. |

| 45 | The chart is based on CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, pp. 916c14–17a21; R97, pp. 737b02–38a15; Z 2:2, p. 369b2–15. |

| 46 | 澄師駁論以来, 海内尊宿大老, 駁其駁者, 亡虑数十家。 CBETA 2020.Q1, X54, no. 878, p. 910b8–9; R97, p. 725a2–3; Z 2:2, p. 363a2–3. |

| 47 | 推其所見妙契佛義也. CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 873, p. 336c21–22; R96, p. 590b6–7; Z 2:1, p. 295d6–7. |

| 48 | CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 873, p. 330c9–11; R96, p. 578a12–14; Z 2:1, p. 289c12–14. The Awakening of Faith is one of the most influential texts on the subject of Buddha-nature theory. It defines the “one mind” as the origin of the world, and explains that it has two aspects—a thusness aspect (zhenru men 真如門) and an arising and ceasing aspect (shengmie men 生滅門)—with the former manifested by the latter. In this sense, the relationship between the two aspects is similar to that between the two truths. |

| 49 | 物者。指所觀之萬法。不遷。指諸法當體之實相; 法法當體本自不遷。非相遷而性不遷也。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 873, p. 332b6–11; R96, p. 581b3–8; Z 2:1, p. 291b3–8. |

| 50 | 守教義文字之師。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 873, pp. 336c24–37a12; R96, pp. 590b9–91a3; Z 2:1, pp. 295d9–96a3. |

| 51 | CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 873, p. 335b4–9; R96, p. 587b1–6; Z 2:1, p. 294b1–6. |

| 52 | CBETA 2020.Q3, X55, no. 893, p. 424c2; R98, p. 591b2; Z 2:3, p. 296b2. |

| 53 | CBETA 2020.Q3, X55, no. 893, p. 420b21–23; R98, p. 583a15–17; Z 2:3, p. 292a15–17. |

| 54 | CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 924a21–b5; R97, p. 752a10–18; Z 2:2, p. 376c10–18. |

| 55 | 海印大士慧書千言。其要則言肇公約俗物立不遷。非真如不遷也。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 924b6–7; R97, p. 752b1–2; Z 2:2, p. 376d1–2. |

| 56 | 今更詰之曰。肇公俗物不遷。為此俗物即真故不遷耶。為不即真而不遷耶。若俗物即真故不遷者。則真不遷矣。而論固違真。若俗物不即真而言不遷者。然不出二義。一謂有為之法剎那滅。故不從此方遷至餘方。此小乘正解也。二謂物各性住。昔物不化。性住於昔故不遷。此外道常見也。CBETA 2020.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 924b8-13; R97, p. 752b3-8; Z 2:2, p. 376d3-8. |

| 57 | 夫言者心之跡。心者言之本。所謂心尚無。多觸言以賓無。故得其言必得其心。因跡以見其本也。 CBETA 2019.Q3, X54, no. 879, p. 924c6–7; R97, p. 753a7–8; Z 2:2, p. 377a7–8. Zhencheng cites “心尚無。多觸言以賓無” from another Zhao lun treatise, On Śūnyatā. The original sentence is “本無者, 情尚於無, 多觸言以賓無”, which Seng Zhao uses to explain the benwu zong 本無宗 proposal (CBETA 2020.Q1, T45, no. 1858, p. 152a19–20). As for the word bin 賓, Yuan Kang 元康, a Tang dynasty monk who annotated the Zhao lun, explains: “Bin means guest, and the guest faces towards the direction of the host 賓者, 客也, 客皆向主”. In addition, he cites the book of Erya 爾雅 when suggesting that the same term may be used as a verb: “Bin means ‘obey’ 賓, 服也” (CBETA 2020.Q1, T45, no. 1859, p. 171c26–29). |

| 58 | 若果如是。即九十六種之言與夫百家世諦之談。苟能忘之。皆第一義。又奚止肇公之言哉。 CBETA 2020.Q1, X54, no. 879, p. 924c3–5; R97, p. 753a4–6; Z 2:2, p. 377a4–6. |

| 59 | Primarily Refutation (Boyu 駁語), An Analysis of “Nature Abides” (Xingzhu shi 性住釋) and The Main Ideas of the Immutability of Things (Wu buqian lun tizhi 物不遷論題旨) in the Longchi Huanyou chanshi yulu 龍池幻有禪師語錄. See cbetaonline.cn/zh/L1637. |

| 60 | CBETA 2019.Q3, L153, no. 1637, pp. 646b15–47a12. |

| 61 | 論中分明謂。果不俱因。因因而果。因因而果。因不昔滅。果不俱因。因不來今。不滅不來。則不遷之致明矣。何嘗謂。因復來今而不滅耶。因既未嘗來今。何眾生永無成佛之理。何修因永無得果之期。 CBETA 2020.Q1, L153, no. 1637, p. 649b2–6. |

| 62 | For more information on the ‘eight negations’, see note 37 and the main text that precedes it. |

| 63 | CBETA 2019.Q3, L153, no. 1637, p. 665a7–10. |

| 64 | Wusheng 無生 (lit. “uncreated/unborn”) equates to “emptiness” in the sense that the original quality of all things is emptiness, and there is no such thing as arising, changing or ceasing. |

| 65 | 况肇公分明云。以性空言去不必去。以性住言住不必住。既言去住之不必者。知皆因對待言也。以對待言。故是知即去住而非去住也。 CBETA 2019.Q3, L153, no. 1637, p. 672b5–9. |

| 66 | For example, in one passage he asserts, ‘Once you see the broad essence of mind, you will recognize that “one thing abides in a period of time”, as stated by Master Zhao, is not beyond the mind. Nor does it differ from “the dharma abides and is established” in Fahua jing 倘爾見得廣大心體了。便識得肇公性住一世。亦不出心外。既知得性住一世不出吾心。即與法華法住法位有何揀別’ (CBETA 2019.Q3, L153, no. 1637, p. 664b11–13). |

| 67 | 可以神會, 難以事求。可以神會者, 是吾儕禪寂中妙觀也。 CBETA 2019.Q3, L153, no. 1637, p. 649a7–8. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Anderl, C.; Dessein, B. Seng Zhao’s The Immutability of Things and Responses to It in the Late Ming Dynasty. Religions 2020, 11, 679. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120679

Liu Y, Anderl C, Dessein B. Seng Zhao’s The Immutability of Things and Responses to It in the Late Ming Dynasty. Religions. 2020; 11(12):679. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120679

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yu, Christoph Anderl, and Bart Dessein. 2020. "Seng Zhao’s The Immutability of Things and Responses to It in the Late Ming Dynasty" Religions 11, no. 12: 679. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120679

APA StyleLiu, Y., Anderl, C., & Dessein, B. (2020). Seng Zhao’s The Immutability of Things and Responses to It in the Late Ming Dynasty. Religions, 11(12), 679. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120679