Abstract

This article connects recent work in critical race studies, museum studies, and performance studies to larger conversations happening across the humanities and social sciences on the role of performance in white public spaces. Specifically, I examine the recent trend of museums such as the Natural History Museum of London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, to name but a few, offering meditation and wellness classes that purport to “mirror the aesthetics or philosophy of their collections.” Through critical ethnography and discursive analysis I examine and unpack this logic, exposing the role of cultural materialism and the residue of European imperialism in the affective economy of the museum. I not only analyze the use of sound and bodily practices packaged as “yoga” but also interrogate how “yoga” cultivates a sense of space and place for museum-goers. I argue that museum yoga programs exhibit a form of somatic orientalism, a sensory mechanism which traces its roots to U.S. American cultural-capitalist formations and other institutionalized forms of racism. By locating yoga in museums within broader and longer processes of racialization I offer a critical race and feminist lens to view these sorts of performances.

“Performance will be to the twentieth and twenty first centuries what discipline was to the eighteenth and nineteenth, that is, an onto-historical formation of power and knowledge.”Jon Mackenzie

1. Introduction

In November 2017, the New York Times published a report within their “Fit City” column titled “Namaste, Museumgoers.” The article described weekly yoga and meditation events that had recently become an official part of the museum’s community programming. According to the program director at the Rubin Museum in New York City, yoga programs utilize the space of the museum to “engage people personally and emotionally” by “mirroring the aesthetics or philosophy of their collections” (Strauss 2017). Catering to an upper-middle class, majority white female demographic which can and does participate in alternative health, spirituality, and wellness consumer culture, such programs advertise their appeal (see Figure 1) with rhetoric like “bringing exotic art to life” or “experience culture for yourself!”

Figure 1.

Seattle Art Museum “Where Art Meets Life” Yoga Program. Source: Seattle Art Museum.

In this article, I examine the growth of museum yoga programs in the United States and the United Kingdom, paying close attention to the kinds of Orientalist logics that tether ideas of museums, materiality, and health to each other. Extending from Waed Hallaq’s recent observation, that Orientalism is “a symptom, rather than the cause … of a psychoepistemic disorder plaguing modern forms of knowledge to the core,” I demonstrate how and why yoga programs in museums reveal a larger sensory infrastructure by which racist thought is made aspirational and everyday (Hallaq 2018, pp. vii–viii). Through critical discourse analysis and feminist ethnographic methods (hooks 1992), I uncover how the space of the museum is constructed not only as a “white public space” (Hill 2008), a practice of “white racial framing,” (Feagin 2013), or an example of “whitewalling,” (D’Souza 2018), but also as an extension of colonial knowledge projects and monuments to imperialism. This attitude towards the way space operates in museums and how individuals engage with that space extends to the broader imperatives of wellness cultures, which center on white racial framings of health. Such framings require an understanding of health as both a “moral imperative” (Ehrenreich 2019) and a neoliberal, spatially-situated consumer activity (Barendregt 2011) that can and does position formerly colonized areas and their cultural-religious practices as a fountain of youth.

In my previous work, I have theorized the racialized dynamic that yoga encourages and cultivates as a primary mechanism of a somatic, rather than literary orientalism (Putcha 2020). Somatic orientalism encourages certain kinds of emotional, psychological, and spatialized attachments to a range of sensory experiences (e.g., sight, sound, taste, smell, touch) that are broadly marketed as “rejuvenating” or “wellness” activities, especially to consumers in the United States (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Still images from yoga tourism campaign by Incredible !ndia (2017).

Here I explore how somatic orientalism shapes yoga programs in museums and more generally in white public spaces. I draw on over a decade of ethnography in the U.S. and the U.K, with a particular focus on Boston, Massachusetts and the Museum of Fine Arts alongside critical social media and hashtag ethnography (Pink 2012; Bonilla and Rosa 2015). First, I consider the relationship between wealth, race, place, and yoga commercialism in Boston and connect this relationship to a much longer and broader history of somatic orientalism, particularly the adoption of Sanskrit into white speech1 in the contemporary moment.2 Then, I situate these broader racial formations in the space of the museum. Specifically, I examine the role of social media in cultivating somatic orientalism and focus on the use of hashtags like #museumyoga and #yogainmuseums, which connect yoga practitioners to each other and to museum spaces. Ultimately, I argue that museum yoga programs participate in and build upon long-standing imperial emotions of domination, performance, and erotics-as-health.

2. Yoga in the Museum

Museum yoga programs reveal the operationalizing of white supremacy in the global North (see Berger 2005; D’Souza 2018; Gandhi forthcoming). As the yoga-in-museums trend has grown in popularity, a parallel discourse has also emerged around the politics of museums, drawing renewed attention to the economic injustice and colonial theft which ultimately led to the establishment of the African, South, and East Asian collections at the British Museum, the Musée du quai Branly, and the Humbolt Forum, among others in European imperial centers. By examining how and why yoga programs have become fixtures in museum programming, it becomes clear that museums not only operate as monuments to imperial domination and violence, but also function as examples of “white institutionality” (Moore and Bell 2017) that reinscribe white supremacist thought and behavior. Indeed, the assemblages that connect imperial projects to museum spaces and then museum spaces to yoga cultures require careful disaggregation in order to see how and why museum yoga programs are now popular across the world and exist as acute examples of imperial affect and intimacy.

The space of the museum operates as a performative space—a sacred space—saturated with very specific meanings and relationalities between objects and their audience. Through the lens of somatic orientalism it becomes possible to understand why yoga and other racialized and nominally “religious” body practices, have become increasingly popular across the Anglophone world as sonic and bodily performances associated with the logic of health and wellness. By conceptualizing yoga programs and related practices in museums as a kind of performance, I am drawing on the work of scholars like Diana Taylor, who note that the “as if and what if qualities fundamental to performance have become central in current military training programs, political practice and protest, artistic performance, theme parks, museums and memorial sites and other areas that elicit experiential engagement from participants and visitors. The hypothetical conditional and speculative mode of the subjunctive is key in knowledge production and transmission” (Taylor 2016, p. 134). Yoga in museums is a prime example of experiential engagement and the speculative mode of the subjunctive. In this case, the experience and the subjunctive—the Orientalist supposition that yoga leads to good health—reflects the residue of colonialism, especially its epistemological contracts, which exclusively center and value extractive and materialist forms of engagement. Indeed, within museum spaces and aided by the materiality of “culture” that museums make explicit, audiences can travel without ever leaving home, so to speak, and can experience the altered mental state that travel is said to provide. Put another way, museums allow visitors to learn about other parts of the world, but in a manner that reinscribes and naturalizes the ideas of imperial domination, theft-as-anthropology, and Anglo-centrism.

In other words, museum spaces not only function as touristic spaces, which encourage certain kinds of performative engagement, but also must be understood as examples of imperial “contact zones” (Pratt 1992). In such zones, culture is distilled and atomized for specific kinds of consumption and according to particular taste habits. Museums require and reproduce imperial palates and thus center the desires and pleasures of those for whom the experience is intended. Yoga-as-wellness in museums thus reveals a new kind of imperial intimacy by encouraging those who participate in these events to identify with romanticized imperial attitudes towards material goods and languages. This romanticization of both the space of the museum and the material cultures they house encourages the utilization of sacred objects for personal and libidinal enjoyment. In other words, yoga in museums is not new per se; it is simply an extension of an established genealogy of touristic attitudes, which normalize using colonized and racialized cultural forms to lubricate imperial fantasies.

These are sensorial fantasies, bound up with affects, pleasures, and desires. Indeed, the examples I provide below echo the rhetoric found throughout imperial accounts of cultural contact, and “draw on a long tradition of male travel as an erotics of ravishment. For centuries, the uncertain continents” that feature most prominently in the museums which host yoga programs such as “Africa, the Americas, Asia were figured in European lore and libidinously eroticized … a fantastic magic lantern of the mind onto which Europe [and today the settler North Americas] projected its forbidden sexual desires and fears” (McClintock 1995, p. 22). Much like the racialized imperatives of tourism and travel which tie notions of health to “vacationing,” in the Anglophone world (Aron 1999), yoga programs held in museums encourage participants to experience the space of the museum as a space of leisure, imbued with exoticized and fetishized logics of voyeurism and travel. I now turn to the Boston yoga scene and how its racialized and classed logics manifest in and around the yoga program at the Museum of Fine Arts.

3. Boston and Yoga

Like most big cities in the United States today, Boston boasts an impressive commercial yoga scene. The most recent data suggests that Boston currently houses the most yoga studios per capita, with over twenty corporate chain studios within just a one-mile radius of the Commons, Boston’s Public Gardens, and some of the most expensive real estate in the country. As a resident of Boston from roughly 2006–2012, I observed new independent, white-owned yoga studios crop up with increasing frequency, in many cases, presaging the gentrification of historically black and/or immigrant neighborhoods like Jamaica Plain and Hyde Park (see Figure 3). Historically working-class white neighborhoods, like the one I lived in—Brighton—did not experience the yoga “fad” until about 2015, arguably because the neighborhood and others like it had other options, like well-funded, community, Christian-affiliated institutions such as the YMCA with various wellness programs available at half the cost of a standard yoga class.3

Figure 3.

Map of Boston area by income. Source: Wealth Divides (Storymaps by ESRI) Numbers in Jamaica Plain inset indicate number of yoga studios.

I began my ethnographic research on yoga cultures in the U.S. in Roslindale, MA and Jamaica Plain, MA in the spring of 2007.4 I observed with curiosity how the majority-minority areas bordering or adjacent to the most expensive and majority white neighborhoods (see Figure 3) were generally the first to house stand-alone yoga studios. In contrast, the wealthy and white neighborhoods housed corporate or chain studios which could offer what is colloquially known as “hot yoga” or “Bikram,” a method in which the room is heated to 105 degrees Fahrenheit and 40 percent humidity. The hot yoga method is usually offered at higher end studios, which are equipped to not only heat the room as required, but also are built to withstand high humidity without causing structural issues to the walls and floors. Indeed, the first hot yoga studio which was accessible to where I lived in the Boston area was located in the posh majority white neighborhood of Brookline, MA.

In Boston—a city which has for generations symbolized the social, cultural, and economic legacies of segregation and housing discrimination—yoga spaces bring the intersection of race and class into sharp focus. My ethnographic research on the Boston yoga scene from 2007–2012 and at studios like those located in Brookline, Jamaica Plain, and Roslindale—which are majority white areas (McArdle 2003)—established a simple truth: yoga was an elite cultural activity and, as an industry, was dominated by socially and economically mobile women. It was during this era of yoga’s popularity in Boston that the Museum of Fine Arts—like the Rubin and other notable museum programs in the U.S.—launched its first yoga program, titled “Family Yoga.” This program, which welcomed children and offered all levels of yoga, was phased out in 2015 in favor of a weekly event which was meant exclusively for adults.

Since 2015, like a number of museum programs in recent years, the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) offers adult-only yoga classes as part of its programming.5 Now rebranded as “Namaste Saturday,” the MFA advertises the event not only as a leisure, networking, and cultural activity, where participants are welcome to “explore the galleries, visit that exhibition you have been meaning to catch or grab a post-workout cup of coffee in the New American Café” but also, a social space where one can “build friendships and feel the energy of the art that surrounds you” (mfa.org; see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Advertisement for “Namaste Saturday” at the MFA. Source: mfa.org.

4. Somatic Orientalism and White Speech

The rhetoric on display in the promotional materials for the Namaste Saturday program offers a clear example of somatic orientalism and the imperial intimacies therein. The word namaste did not only appear on the printed materials. The instructors who led the Namaste Saturday events at the MFA also said and gestured namaste to their students as they ended class.

It is at this point but a truism across a number of industries and in particular across the North American cultural landscape that the use of namaste, as either gesture or word, is consistently linked to the popularity of yoga. Yoga is not simply a reference to a physical movement practice, but rather, a lifestyle, which can and does assume political affinities6, dietary habits, and what might broadly be understood as a set of cultural practices that are positioned as “progressive.”

It is worth noting, however, that the use of namaste as a symptom of somatic orientalism is not new nor is it unique in the Anglo-American setting. In the two decades or so since it entered popular culture vernacular, the word namaste has been described within yoga spaces as a Sanskrit “Hindu greeting” and translated into English to mean everything from “the light in me honors the light in you” to “I bow to the divine in you” to simply “hello.” Overzealous translations notwithstanding, in the years that I have been tracking its usage and meaning in Anglophone spaces, namaste, along with a handful of other words like om and chakra have entered the lexicon to signal a complicated and, at times, contradictory set of cultural signposts. This formation in the case of namaste points to how language participates in establishing white public spaces. For example, in her work on how translation practices installed white knowledge, Virginia Jackson notes that the kinds of translation which emerged from imperial contact zones were often constructed so that English speakers could believe that they were the exclusive and evolutionary descendants of the “vanishing natives” (Jackson 1998, p. 477). The adoption of words from indigenous languages into settler English in the U.S. context and the transliteration as well as translation of such words established white speech as both natural and omniscient.

Words like namaste, om, and chakra operate as forms of white speech and are also generally intended as a pun or some sort of humorous device or branding technique to signal a specific kind of cultural appeal to a consumer base. Namaste especially has emerged in the contemporary moment as a gesture or cue to South Asia and/or the Middle East, while remaining in the hands of white producers and consumers of yoga or “alternative” wellness culture. For example, the website namaste.com, which was purchased by a Canadian cannabis company in the early 2000s, offers a clear example of how somatic orientalism operates by collapsing yoga, alternate medicine, spirituality, and capitalism into one neat package (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Homepage for Namaste.com.

Today, it is not uncommon to see namaste as well as om and chakra, featured prominently in commercial yoga spaces in the United States, particularly in the form of rhymes or puns like the one in the MFA’s promotional materials. However, the easy slippage between yoga, namaste, and museums spaces suggests the role of humor—what Jane Hill has described in her work as “mockery”—is foundational to both the way white speech operates as a form of social power as well as how white public spaces appeal to their target populations.7

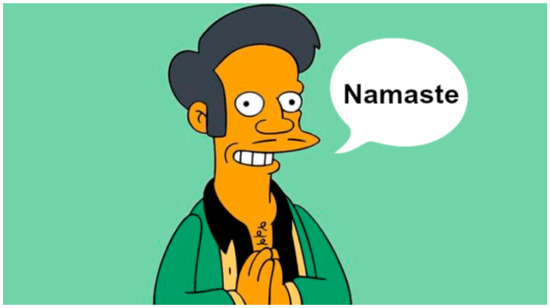

To provide an example of how white speech as humor reveals power dynamics, in 2017, CNN anchor Alisyn Camerota, who began her career with Fox News, interviewed the 2017 Spelling Bee winner, 11-year-old Ananya Vinay. During the interview Camerota and her co-host asked Vinay to spell a word and joked, “we’re not sure if that word is actually in Sanskrit, which is probably what you’re used to using.” The fact that Camerota had previously spoken about her yoga and meditation regimen suggests the logic at play here and how she assumed that an Indian-American child, born and raised in Fresno, California knew Sanskrit. Beyond the collapsing of Sanskrit as a language with Indians as racial group, the sarcasm and mocking tone in Camerota’s commentary is but an instance of the white speech we can also observe in the MFA’s promotional materials. This brand of white speech is inextricably linked to the kinds of humor made famous by the Simpsons character Apu (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The Simpsons Dr. Apu Nahasapeemapetilon. Photo source: Fox.

The ubiquity of mocking puns as well as accents—through a cultural institution as prominent as the MFA—even in the face of growing awareness that such language is profoundly racist and harmful, signals just how normalized somatic orientalism is in white society.8 In the United States context, one could easily argue that while we recognize a few very well-known words as symptoms of white supremacist speech, we lack a particularly adept understanding of how sound, including words, accents, musical themes, and associated body languages are normalized as white performances of power. Within the longer history of white speech, extending from the context of imperialism, enslavement, and settler colonialism, it is indisputable that logos, images, and styles of dress accompany associated words or sounds. To be sure, sounds, images, and bodily gestures, especially those performed in/as a group, all accrue stereotyping force and work together to uphold racist thought.9

In this regard, much of what we understand as popular culture, including commercial forms of yoga, arguably extends from the legacy of minstrelsy in the United States. Though the practice of minstrelsy emerges from nineteenth-century entertainment cultures, it endures through the tendency to caricature people of color and their cultural practices through derogatory and reductive stereotypes. This tendency, which often shapes rhetoric around multiculturalism by managing and tokenizing cultural difference, in turn, reproduces the white racial frame in destructive and toxic ways. To this point, Karl Hagstrom Miller echoes Virginia Jackson’s arguments, noting that minstrelsy installed white supremacy as American culture. According to Miller, “whites claimed an almost ethnographic authority in their portrayals,” which, advanced the notion that “genuine [non-white] culture emerged from white bodies” and their representative practices (Miller 2010, p. 5). Put another way, culture is only legible as culture when it is performed through white bodies.

In the case of U.S. yoga cultures, however, the co-option and commodification of words like namaste belong within a different, though related history of white supremacy and paternalism, stemming from British imperialism and colonialism in South Asia. The circulation of namaste, for example, emerges from the colonial encounter and the way certain words came to symbolize what the British considered as representative of Indian culture. In written records, namaste is used by the British to note a “Brahmin Hindu gesture.” In ethnological, anthropometric records and census documents such as those from the 1800s, British travelers and colonial authorities alike describe namaste as a “bowing posture,” accompanied with “hands pressed together” (Watson and Kaye 1868). Under the British Raj, namaste and its associated gesture emerge as a symbol of that which made Indians culturally different. More importantly, in colonial accounts, namaste appears as a symptom of the “authentic Hindu,” a religious and reductive distinction the Oxford English Dictionary uses to trace the etymology of the word.10

5. #MuseumYoga

While it might appear relatively innocuous across the commercial yoga landscape, the use of namaste by the MFA, appearing as it generally does as a pun or a rhyme (see Figure 4), is consistent with a number of somatic orientalist practices. Such practices become hypervisible and yet more normalized when they occur in a cultural space like a museum. The use of the near-rhyme, Namaste Saturday, in this case, belongs to a broader practice of using humor within white speech to operationalize the white racial frame by making cultural difference more approachable. In the case of yoga, the infiltration of certain words through a form of rhetorical humor not only indexes the process by which yoga has become uniquely American, but also reveals how and why the use of tongue-in-cheek humor operates in an educational space like a museum to reproduce certain ways of engaging with the world. In museum spaces which are meant to convey a sense of historicity among other versions of knowledge, the use of a rhyme is meant to make yoga “fun,” and “accessible,” an attitude which is consistent across commercial yoga spaces and has been a constant in the years of fieldwork I have conducted. In each instance, this attitude reveals a complex interplay of orientalism, racism, and cultural tourism-as-leisure.

Since at least 2015, when the Namaste Saturday event was launched as an official program at the MFA, the marketing and advertising for the event has relied on specific language meant to convey that the space of the museum would make the wellness impact of a yoga class more memorable, more restful, and more of an experience. Held on Saturdays at 9 a.m., the classes are advertised at $25 for non-members of the museum, but free for those who are members (see Figure 7). Importantly, in the years since the program was first launched, it has slowly crept into the realm of influencer culture, dovetailing with broader trends in the yoga world wherein the yoga instructors with the largest social media followings garner the most attention. In turn, these instructors draw their own crowd to the event each Saturday and these attendees then post about the event on social media thus creating a marketing feedback loop. In the past few years, the featured guest instructors at the MFA have been consistently positioned and marketed in this manner. Additionally, in the years since I have been following the programming at the MFA, the featured instructors have almost exclusively been white women, a statistic that is consistent across yoga spaces in the North American context (Birdee et al. 2008; Park et al. 2015).

Figure 7.

Namaste Saturday at the MFA. Photo Source: mfa.org.

In this regard, social media research reveals how these new imperial intimacies in the museum and through yoga as an activity circulate and accrue affective power in the twenty-first century. In the last five years, hashtags like #yogaeverywhere, #museumyoga, or #yogainmuseums have gained traction and suggest that those who participate in museum yoga are not simply in search of an enjoyable experience, but also seek to capture the moment in a way that produces some sort of social capital in the process.

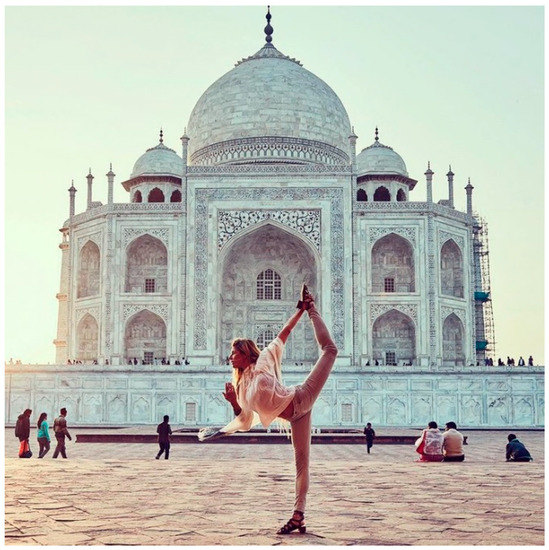

The logic here, which is also present in other performances of yoga in spaces where one would not expect yoga, is that of virtue-signaling—the notion that yoga, even physically challenging forms, can be done anywhere and by anyone. Simultaneously, there is usually a hint of verisimilitude as well as irony which accompanies such posts. In many cases, the yoga programs—like the one at the MFA—refer to the artwork for its affective potential. Furthermore, these programs explicitly acknowledge the expectation for silence in museums as a key element of what makes museums an ideal space to practice yoga, mindfulness, or meditation. For example, in Figure 8, the yoga “pose” is inspired by the artwork. The poser is attempting to emulate and therefore “embody” the art—a universalist and narcissistic logic which underscores fixed and extractive theories of embodiment in white publics. This kind of affective attachment—which is drawing yoga consumers to the space of the museum—and the gravitas it offers, mirrors what one encounters in touristic engagements with monuments (see Figure 9). 11

Figure 8.

#museumyoga, on left, a white woman performs “eagle pose” with an eagle carving in the background. Photo Source: Instagram.

Figure 9.

Tourism Advertisement for Yoga Classes at the Taj Mahal. Photo Source: https://rove.me/to/taj-mahal/yoga-classes-facing-taj-mahal.

Yoga tourism campaigns that market to the wealthy and white demographic—the same demographic with membership access to premium museum programming—rely on very specific logics of cultural performance and rhetorical, if not romantical, ideas of space. Wael Hallaq suggests that the epistemic imperatives visible in such moments require us to disaggregate orientalism from orientalists—to recognize that individual and performative acts are but an instance of the systemic (Hallaq 2018). In this regard, #museumyoga offers a timely reminder that ever-more flexible regimes of accumulation and citizenship traverse and exploit space, demolishing spatial barriers. Thus, while research on tourism offers perspective on how and why people engage with spaces that are firmly established in the orientalist racial imagination (like the Taj Mahal), museums and their yoga programs offer a related affective attachment—an affordable way to travel to exotic places without having to leave home. This kind of touristic engagement becomes ever clearer beyond and perhaps even after the participant has left the space of the yoga class or museum, and instead comes into focus through the performance social media spaces make possible.

Following this recognition, it is also important to understand that the idea of travel remains tightly connected to notions of class mobility. Museums like the MFA, after all, have for generations served the public at a relatively low cost (general admission tickets $10–25) and are positioned as philanthropic organizations intended to serve the “community”—a collective which remains undefined but implied. A yoga program held in such a space is also intended to be affordable and accessible to the broader public. However, in the case of the MFA, the ways this space is used contradicts egalitarian claims of access and community.

The space where the yoga programming is held at the MFA, like most museum yoga programs (see e.g., the Brooklyn Museum), is large and meant to convey a sense of grandeur (see Figure 7 and Figure 9). Designed by Norman Foster, the founding member of the London-based firm Foster + Partners, the glass and steel enclosure is meant to “enrich the way visitors encounter the MFA’s great works of art” (see mfa.org). This stated intention is puzzling, however, since the courtyard is not a space that houses installations, but rather operates primarily as a social space, where black-tie and other glamourous events for Boston’s wealthy elite are held with regularity. In other words, the Shapiro courtyard is not an art space but rather a space for gathering, and during my time at the museum I was able to observe the transformation of the space for a gala event (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Ruth and Carl J. Shapiro Courtyard. Photo Source: Author.

One rainy day while I was conducting ethnography at the MFA, I stood along the perimeter observing the catering team set up the courtyard with a bar and cocktail tables. A cheerful museum employee wandered over to chat with me and asked if I needed any help. He was eager to tell me about the courtyard and recited a short, prepared lecture on the history of the space. For example, he shared with me that the courtyard, named after the family trust and philanthropic organization, the Ruth and Carl J. Shapiro Foundation, functioned as an important social and cultural space in Boston. I mentioned to him that I was studying the use of the courtyard for yoga classes and he replied, “yeah, those are really popular.” I asked if he had ever attended and he shook his head and commented, “no I don’t think they would let us, but the employees have our own yoga program in one of the office rooms. No windows or views in there like in here, but they do offer that to us.”

This brief exchange remains a flashpoint in my ethnographic research on yoga and suggests that the relationality between orientalism and health is shifting and at times, requires a specific kind of power dynamic between participant and the space in which they seek health. What might it mean that, for those who work in the space of the museum and for whom the space is not othered, the escapism that the Namaste Saturday event is intended to inspire remains unavailable? The acknowledgement that employees are actually not welcome at these events reveals a service model, to be sure, where those serving are not allowed to socialize with those being served. Put another way, this moment captured a clear example of how the museum and its programming ultimately expose the fault lines of class and whiteness while reaffirming imperialist attitudes.

6. Conclusions

In the past twenty years museums have been moving towards more interactive models, to close the gap between what Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett describes as the distinction between “informing and performing” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998). Performing in this binary relies on the premise that a museum is not simply a collection of objects that are observable, but rather offers a site for social and public practices—practices which can and do rely on somatic meanings. In other words, there is an exchange process available in a museum, based on the entrenched idea that the art and its resonance can somehow transform the viewer in a material sense (see also Miller and Yudice 2002). It is this logic that leads museums like the MFA to host Namaste Saturday or the Rubin Museum of Art in New York to advertise their yoga programs in their South Asian art collection with phrases, like “it’s not every day you can do a warrior pose beside a work of art depicting a deity doing the same pose” even as warrior pose is not a pose that one commonly sees depicted in South Asian art, performance or otherwise. Advertising language like this, steeped as it is in the mechanisms of white speech, suggests that material cultures can provide a rare link between the material world and the spiritual one. In offering orientalist yoga programming, the museum simultaneously emerges as a tourist zone and a pseudo-spiritual health club. The narrative technology of the art housed within the space of the museum provides a tether between tourism and health. In other words, the museum and the kind of proximity to whiteness which it provides are fundamental to its success, commercial or otherwise.

Ultimately, yoga programs in museums, like yoga commercialism more generally, demonstrate entrenched imperial forms of engagement between the material and the affective, and between notions of health and travel. Indeed, in the nearly forty years since Benedict Anderson first commented on the role of museums within the larger imperial project as evidence of an overactive racial imagination, white public spaces have become ever more visible, “illuminating the…style of thinking about…domain. The ‘warp’ of this thinking [is] a totalizing classificatory grid, which [can] be applied with endless flexibility to anything under the state’s real or contemplated control: peoples, regions, religions, languages, products, monuments, and so forth. The effect of the grid was always to be able to say of anything that it was this, not that; it belonged here, not there. It was bounded, determinate, and therefore—in principle—countable. The ‘weft’ was what one could call serialization: the assumption that the world was made up of replicable plurals” (Anderson 1983, p. 184). In the end, the epistemology of replicability—a version of Taylor’s “subjunctive”—reminds us that museum yoga is but one example of how white publics structure and maintain relationships with the material world through performance.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, Cindy Sondik. 1999. Working at Play: A History of Vacations in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barendregt, Bart A. 2011. Tropical spa cultures, eco-chic, and the complexities of new Asianism. Cleanliness and Culture 272: 159–92. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Martin A. 2005. Sight Unseen. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birdee, Gurjeet S., Anna T. Legedza, Robert B. Saper, Suzanne M. Bertisch, David M. Eisenberg, and Russell S. Phillips. 2008. Characteristics of Yoga Users: Results of a National Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23: 208–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla, Yarimar, and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. #Ferguson: Digital Protest, Hashtag Ethnography, and the Racial Politics of Social Media in the United States. American Ethnologist 42: 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, Aruna. 2018. Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts. New York: Badlands Unlimited. [Google Scholar]

- Edensor, Tim. 1998. Tourists at the Taj: Performance and Meaning at a Symbolic Site. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich, Barbara. 2019. Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainity of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer. New York: Twelve. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin, Joe R. 2013. The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Racial Framing and Counter-Framing. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, Shreena. N. Forthcoming. Yoga: Whiteness and Appropriation in the United States.

- Hallaq, Wael B. 2018. Restating Orientalism: A Critique of Modern Knowledge. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jane H. 2008. The Everyday Language of White Racism. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 1992. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Virginia. 1998. Longfellow’s Tradition; or, Picture-Writing a Nation. Modern Language Quarterly 59: 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 1998. Folklore’s Crisis. The Journal of American Folklore 111: 281–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, Nancy. 2003. Beyond Poverty: Race and Concentrated-Poverty Neighborhoods in Metro Boston. The Civil Rights Project. Shenzhen: UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, Anne. 1995. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Karl Hagstrom. 2010. Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Toby, and George Yudice. 2002. Cultural Policy. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Wendy Leo, and Joyce M. Bell. 2017. The Right to Be Racist in College: Racist Speech, White Institutional Space, and the First Amendment. Law & Policy 39: 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L., Tosca Braun, and Tamar Siegel. 2015. Who Practices Yoga? A Systematic Review of Demographic, Health-Related, and Psychosocial Factors Associated with Yoga Practice. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 38: 460–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pink, Sarah. 2012. Digital Ethnography. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Putcha, Rumya Sree. 2020. After Eat, Pray, Love: Tourism, Orientalism and Cartographies of Salvation. Tourist Studies 20: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, Alix. 2017. Namaste, Museum Guests, It’s Time to Get Mindful. New York: The New York Times. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Diana. 2016. Performance. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, John Forbes, and John William Kaye, eds. 1868. The People of India: Series of Photographic Illustrations, with Descriptive Letterpress, of the Races and Tribes of Hindustan. London: W.H. Allen and Co. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In her work, Jane Hill introduces the idea of “white speech” as that which appropriates and incorporates words from other languages in order to mock and establish dominance over the other. See Hill (2008, p. 169). |

| 2 | Somatic orientalism in museums allows for a continual production of racial difference couched in a psychoepistemology of space as bounded. |

| 3 | The national average for a yoga studio membership is $100/mo. or $20/drop-in class. The YMCA, in contrast, charges approximately $46/mo. |

| 4 | The first studio where I conducted ethnography (Blissful Monkey Yoga Studio) was located in Jamaica Plain, MA, next door to a popular brunch restaurant. |

| 5 | A number of major metropolitan museums offer yoga classes: the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Fischer Museum (Los Angeles), the Natural History Museum (London), the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts (Houston), the Asian Art Museum (San Francisco). This list is not comprehensive in the least. |

| 6 | See for example the so-called “yoga vote” and the brief presidential campaign of Marianne Williamson in the United States. |

| 7 | Linguistic anthropologists like Jane Hill, and her theory of mock Spanish and white public space offers some avenues for understanding how white homogeneity and hegemony breeds supremacist ideology, which extends past speech to behavior, sonic identifiers, and imagery. |

| 8 | In the case of yoga cultures, Lululemon, the eponymous “athleisure” brand in North America arguably championed this trend with Sanskrit in the early 2000s and now offers an impressive array of merchandise that relies on puns, like their Namastay Put Thong II or their Namastay Focused Pant. |

| 9 | A prime example in the case of Native American representation here is the Tomahawk “chop” theme, along with its associated “chopping” hand gesture, which fans reenact at Atlanta Braves baseball games. |

| 10 | It is worth noting that the OED emphasizes the prominence of the word namaste in how the British understood and studied Hindu social behaviors (in contradistinction to Muslim, for example). |

| 11 | In his research on how tourists perform their relation to space at the Taj Mahal, Tim Edensor extends David Harvey’s idea of postmodern “space-time compression” whereby distances in space and time become diminished through technologies of communication, information, and travel (see Edensor 1998). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).