Abstract

This paper examines the characteristics and production background of major examples of single-sheet Buddhist woodblock illustrated prints. In the form a single sheet of paper, the original first prints were not easily handed down, and in most cases the date and place of production are not clearly known. These factors made systematic research difficult, but the release of various related materials has recently enabled comprehensive study of the subject. As materials substantiating Buddhism’s religious role in society and the propagation activities of temples, single-sheet Buddhist prints hold great value. Research showed that two major types of single-sheet Buddhist prints were made: dharani-type prints used as talismans and prints used for worship or spiritual practice. The former type was likely made for self-protection or Buddhist enshrinement in statues for their protection and to seek blessings for this meritorious deed or to protect the dharma. The latter type was used as a visual aid in worship and chanting. They can be divided into prints featuring universally loved icons and prints featuring icons reflecting the trends of certain periods. They were analyzed in relation to popular beliefs and methods of spiritual practice in the Buddhist circle as well as trends in faith among the ordinary people.

1. Introduction

Single-sheet Buddhist woodblock illustrated prints, the subject of this paper, were conceived and produced as independent, complete prints with all the content on a single sheet of paper. These single-sheet prints featuring Buddhist icons have not attracted great attention for research compared to prints of sutra illustrations, either on the frontispiece or inserted in the sutra. This can be primarily attributed to their form as a print on a single sheet of paper, which means the original imprints were not easily handed down, and the fact that in most cases the date and place of their publication is not clearly known. These factors have made it difficult to conduct systematic research on single-sheet Buddhist prints. However, as printing woodblocks and related materials preserved at Buddhist temples have gradually been made public in recent times, it was confirmed that diverse single-sheet Buddhist prints were produced during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties. As they were works made in the woodblock print form and hence intended for mass production, the content carved on a single woodblock gives insight into the forms of faith that were popular among the people at the time. In this sense, they hold great value as materials that can substantiate Buddhism’s religious role in society and the propagation activities of temples. Moreover, some of these single-sheet Buddhist prints can be examined in direct relation with Buddhist paintings of the same period, which makes them a worthwhile subject of study from the perspective of art history.

The iconography of single-sheet Buddhist prints can be divided into three types: dharani and pictures of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, which function as a kind of talisman; solo pictures of the Buddhist dharma protectors; and pictures of sermons featuring the Buddha and the holy ones. As with the publication of sutras, single-sheet prints were seemingly produced “to propagate the dharma and accumulate merit”. In this regard, if we look at records from China, where woodblock printing techniques originated, Fascicle 5 of Miscellaneous Records of the Cloud Immortals (Yun xian san lu)1 by the scholar Feng Zhi 馮贄 of the late Tang dynasty says “Every year Xuanzang 玄奘 printed enough images of Samantabhadra on huifengzhi 回鎽紙 [a kind of paper] to load on the backs of five horses and distributed them to monks, nuns and male and female lay believers and none were ever left over”, quoting Seng guo yi lu 僧國逸錄. In addition, in the Song dynasty Tripitaka preserved at Chion-in 知恩院 Temple in Kyoto, Japan, the end of Fascicle 6 of Daciensi sanzangfashi zhuan 大唐大慈恩寺三藏法師傳 (a biography of Xuanzang) says “Monk Rizhi 日智, after witnessing the Jingkang Incident and seeing people suffering the pain of war, out of his love for sentient beings held a Suryukjae rite [rite for deliverance of beings of water and land] to liberate them from suffering and printed 20,000 copies of pictures of Amitabha and Avalokitesvara [for the occasion]”.2 Such records from the Tang dynasty indicate that monks made copies of single-sheet prints for distribution to sentient beings and propagation of the dharma. As such, it appears that single-sheet Buddhist prints were largely used for two main purposes. First, the dharani type, produced under the belief that simply carrying them on the body meant protection by the dharma, served as a kind of talisman. Second, prints of a Buddha or bodhisattva or a sermon by the Buddha were used for worship purposes, in the same way as Buddhist paintings. Buddhist iconography carved onto woodblocks in the form of Buddhist paintings and in the form of dharani may be superficially different in type, but in that they both manifest trends in people’s faith at the time and directly and immediately reflect the wishes of the people in a single-sheet print they were both made with the same objectives. Of course, Buddhist books composed of many sheets of printed material functioned as a conduit for knowledge, object of worship and talisman. It is important to note, however, that the function of such books was limited to the literate class. Just as Buddhist iconography was developed to convey Buddhism’s complex philosophy to the masses in an easier and more intuitive way, single-sheet Buddhist prints expressed the content of Buddhist books, expounded in a written language that was difficult to understand, in a single-sheet picture or dharani comprised of icons representing that content. These prints were made to be distributed to the masses. The people who were the consumers of single-sheet Buddhist prints used these prints, based on the forms of Buddhist faith with which they were familiar rather than the complex contents of Buddhist books, as a device to realize their prayers and wishes. In this context, it can be said that single-sheet Buddhist prints serving as paintings or as dharani were made for the same purpose. Therefore, this paper divides single-sheet Buddhist prints into the dharani type, containing prayers for self-protection and protection of the dharma, and prints made for the purpose of spiritual practice and worship. Through the investigation of major examples of both types, this paper explores their characteristics and the background to their production.

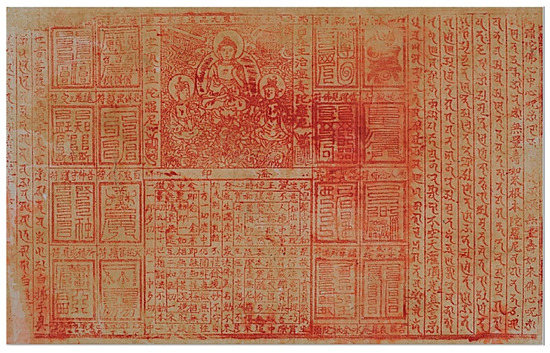

2. Dharani-Type Prints Functioning as Talismans

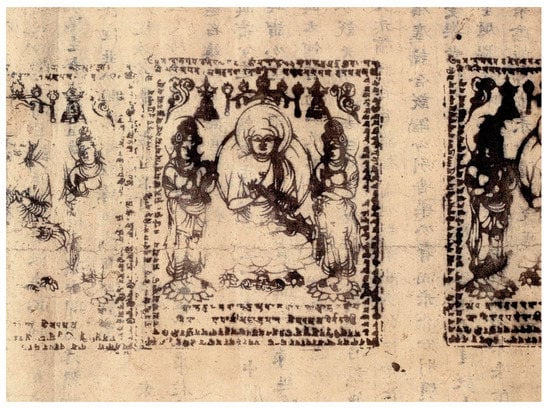

Printed copies of dharani were steadily produced from the time Buddhist prints began to appear. The word “dharani” generally means a Buddhist mantra which has been visualized and materialized by writing it down or printing it on paper or silk. The oldest extant single-sheet dharani print is a stamped picture of the Amitabha Triad3 on the back of a hand-written copy of Fascicle 10 of Misrakabhidharmahṛdaya sastra (Ch. Za a pitan xin lun 雜阿毗曇心論), which was discovered in the Mogao caves in Dunhuang and is now preserved at the National Library of China (Figure 1). This print shows the Amitabha triad in the center surrounded by a dharani written in Sanskrit and can be regarded as an early form of Sanskrit dharani. This kind of dharani in the form of a seal stamped on paper was later carved onto woodblocks for printing. The composition also changed as the icon was gradually reduced in size and the space for the Sanskrit dharani increased.

Figure 1.

Misrakabhidharmahṛdaya sastra (Ch. Za a pitan xin lun), Fascicle 10, “Amitabha Triad Seal”, Dunhuang Manuscripts, Southern and Northern Dynasties, National Library of China. Source: (Li 2008, Figure 1).

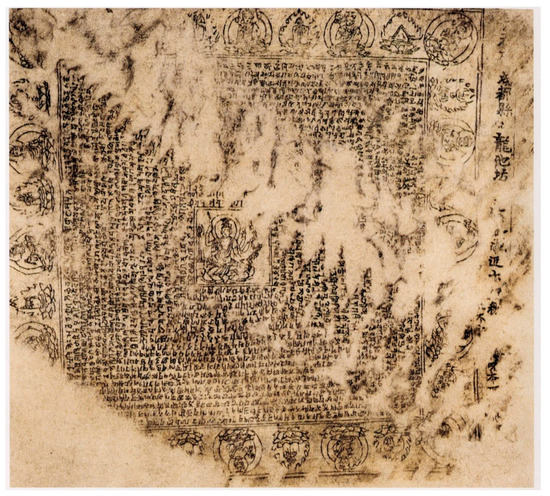

The Pratisara Dharani (Ch. Suiqui tuoluoni 隨求陀羅尼) preserved at the National Library of China (presumed eighth century) was discovered in a Tang dynasty brick tomb on the grounds of Sichuan University in Chengdu, Sichuan Province.4 This dharani print features the eight-armed bodhisattva Mahapratisara in the center surrounded by the dharani in Sanskrit, which is then surrounded by the 33 ritual objects of esoteric Buddhism, mudras, and bodhisattvas on lotus pedestals (Figure 2). It was found inside the silver bracelet on the right arm of the occupant of the tomb. That such dharani prints were used as burial items clearly indicates that they functioned as a kind of talisman from the Tang dynasty. The sutras on which the extant dharani is based are the Mahapratisara Dharani Sutra (Ch. Foshuo suiqiu jide dazizai tuoluoni shenzhou jing 佛說隨求卽得大自在陀羅尼神呪經; translated into Chinese by Manicinta, ?–721) from 639 and Mahapratisara Vidyarajni Sutra (Ch. Pubian guangming qingjing chisheng ruyi baoyinxin wunengshengdamingwang dasuiqiu tuoluoni jing普遍光明清淨熾盛如意寶印心無能勝大明王大隨求陀羅尼經; translated into Chinese by Amoghvajra, 705–74). The Chinese-character translations of both these sutras state that if this dharani is written down on paper and worn around the arms or neck, one can benefit from its miraculous power.5 Moreover, by carrying this dharana, one will have all sins extinguished, regardless of their gravity, attain infinite merit, and see one’s wishes come true; after death, one will have an easy passage to paradise and attain Buddhahood. This particular copy of the Pratisara Dharani, discovered near the body of the deceased, is thought to be closely connected to the legend of the bhikku of little faith 小信心比丘 (K. sosinsim bigu),6 which goes, “A bhikku who had sinned suffered a terrible disease but a Brahman upasaka wrote the Pratisara Dharani for him and cured him. Later, when the bhikku died he fell to Avici [the lowest hell], but since the dharani was placed on his body he was not punished, though he was in hell, and was reborn in Trayastriṃsa heaven [second heaven of the desire realm]”.7

Figure 2.

Pratisara Dharani (Ch. Suiqui tuoluoni), Tang (presumed around 8th century), 31.0 × 24.0 cm, National Library of China. Source: (Li 2008, Figure 4).

Considering the many examples of Pratisara Dharani being buried in tombs during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, the dharani evidently also functioned as a talisman for the dead in Korea. However, in Korea, the Pratisara Dharani was often found enshrined inside a Buddhist statue as a votive object, suggesting that other than praying for the soul of the deceased to be guided to the next world the dharani was used in a wider context.8 In two Goryeo prints of the Pratisara Dahrani found enshrined inside the Wooden Seated Amitabha (twelfth-thirteenth century) at Jaunsa 紫雲寺 Temple in Gwangju and the Wooden Seated Avalokitesvara at Bogwangsa 普光寺 Temple in Andong (eleventh-twelfth century), respectively, the principle icon in the center is depicted in the form of a bodhisattva with the right knee on the ground and holding an attribute in the left hand (Figure 3).9 The diversity of the principle icons appearing in Pratisara Dharani is thought to be rooted in the sutras which say different deities must be depicted according to the rank of the patrons.10 This aspect aside, in overall form, composition and iconography the Korean Pratisara Dharani prints are very closely related to their Tang dynasty counterparts, including the abovementioned dharani discovered in a Tang dynasty tomb in Sichuan. Moreover, the discovery of Pratisara Dharani prints with such iconography in Korea, where most examples consist only of Sanskrit writing, is a matter of great interest. Discovered in almost perfect condition they provide clear evidence that the tradition of Pratisara Dharani produced from the Tang dynasty of China was transmitted to Korea’s Goryeo dynasty. As the Pratisara Dharani was also found as a votive object enshrined in Goryeo Buddhist statues, its function was apparently expanded from the supernatural protection of the deceased to imbuing the Buddhist statue with sacredness and expressing the prayers and wishes of the patron.

Figure 3.

Pratisara Dharani (K. Sugu darani), Goryeo (12th century), woodblock print, 32.3 × 34.8 cm, enshrined in the statue Wooden Seated Avalokitesvara of Bogwangsa Temple. Source: (Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage 2009, p. 52).

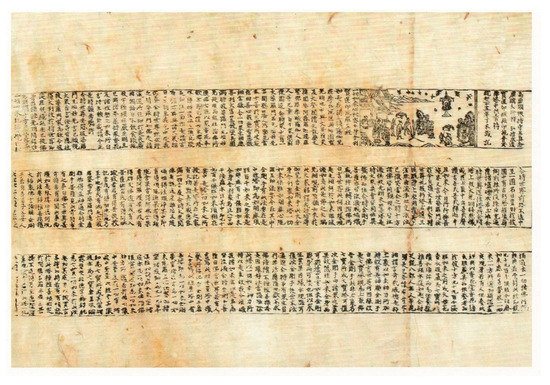

Another example of a dharani enshrined inside a Buddhist statue is the print of the Casket Seal Dharani (K. Bohyeopin darani 寶篋印陀羅尼) (Figure 4) discovered inside the Wooden Seated Avalokitesvara at Bogwangsa Temple in Andong. This dharani consists of the Sutra of the Whole-Body Relic Treasure Chest Seal Dharaṇi, The Heart Secret of All Tathagatas printed on a large single sheet of paper. The sutra was first published in pocket-book size (to be carried inside the sleeve) by Chongjinsa 摠持寺 Temple in 1007, the tenth year of the reign of King Yejong 睿宗 of Goryeo. The statue-enshrined print of the sutra, considering its condition and the publication date of the books discovered with it, was likely printed around the time the statue was made between the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The front part features a sutra frontispiece illustration that depicts the contents of the prologue of the sutra, so strictly speaking it is not the print of a dharani but a sutra illustration in print form. However, as this dharani is not in the form of a scroll but a print on a single large sheet of paper, containing the sutra text and illustration, presumably it was printed from the outset for enshrinement as a votive offering. Enshrining the Casket Seal Dharani in this way, based on the contents of the sutra saying “If this dharani is written down and enshrined in a Buddhist pagoda or statue, the pagoda or statue will be protected while the patrons who made the offering will have their wishes come true”,11 suggests that it was made as a kind of talisman.

Figure 4.

Casket Seal Dharani (K. Bohyeopin darani), Goryeo (1007), 32.3 × 45 cm, Enshrined in the statue Wooden Seated Avalokitesvara of Bogwangsa Temple. Source: (Central Buddhist Museum 2014, p. 99).

Finally, the Dharani of the Buddha of Immeasurable Life (K. Muryangsu yeorae darani 無量壽如來陀羅尼), presumably produced in the seventeenth to eighteenth century, has a slightly different meaning to the talisman-type dharani mentioned above (Figure 5). A picture of Amitabha in the Pure Land and Diagram of the Avataṃsaka Single Vehicle Dharmadhatu (K. Hwaeom ilseung beopgaydo 華嚴一乘法界圖) are arranged in the center with various talismans and mantras on both sides. First, the Buddha triad sitting on a lotus pedestal arising from the lotus pond and the phrase “Picture of the nine-tiered lotus leaf platform in Sukhavati [Western Pure Land]” carved on top indicate that the iconography is the Amitabha Buddha triad in the lotus pond of the Western Pure Land. To the left and right of the triad are the names Jajaewang chiondok darani 自在王治溫毒陀羅尼 and Ilja jeongyunwang darani 一字頂輪王陀羅尼 (Dharani of the One-syllable Wheel-turning Ruler). At the bottom, along with the name “Haein 海印”, is the Diagram of the Avataṃsaka Single Vehicle Dharmadhatu. On either side of Amitabha in the Pure Land, along with the phrases “dandeukgyeon bulbu 當得見佛符” (meaning “if one carries this talisman and makes a sincere effort one will be able to meet the Buddha”) and “wonisamjaebu 遠離三災符” (meaning “talisman to keep the three disasters far away”), there are 16 talismans arranged in two columns in four rows. Beside the talismans on the right side are mantras related to Amitabha Buddha such as Amitabul simjung simju 阿彌陀佛心中心呪, Muryangsu yeoraebul simju 無量壽如來佛心呪, Muryangsu yeorae geunbon darani 無量壽如來根本陀羅尼(Root Dharani of Infinite Life Tathagata), and Bulgong daegwanjeonggwang jineon 不空大灌頂光眞言(Gwangmyeong jineon 光明眞言, or the Mantra of Light), and on the left side mantras related to Avalokitesvara such as Gwanseeum bosal simuoesu jineon 觀世音菩薩施無畏手眞言, Baekbulsu jineon 白拂手眞言, Baengnyeonhwasu jineon 白蓮華手眞言 and Cheongnyeonhwasu jineon 靑蓮花手眞言.12

Figure 5.

Dharani of the Buddha of Immeasurable Life (K. Muryangsu yeorae darani), Joseon (presumed 17th-18th century), 39.0 × 50.0 cm, Wongaksa Temple. Source: (Dongguk University Academy of Buddhist Studies 2017, p. 469).

This arrangement of Amitabha in the Pure Land and Diagram of the Avataṃsaka Single Vehicle Dharmadhatu along with various mantras related to Amitabha and Avalokitesvara in one single dharani print is highly interesting for it clearly reflects the spread of Three Gates Buddhist Practice (sammun sueop 三門修業-teachings of the Seon 禪 and Gyo 敎 [Doctrine] schools plus prayer).13 When considering the structure of the dharani in which the various talismans and mantras seem to be protecting the icons in the center from the outside, this print, rather than being an object of worship, is thought to be a dharani with a strong talismanic nature for the protection of the dharma, reflecting the personal religious tendencies of the monks who made it. That is, the Diagram of the Avataṃsaka Single Vehicle Dharmadhatu has been arranged in the center of the lower half of the print and above it Amitabha, one of the many incarnations of the Buddha, flanked by attendant bodhisattvas. The arrangement of varied Buddhism-related talismans and dharani related to Amitabha and Avalokitesvara on the left and right sides can be interpreted as a visual representation of the Buddhist world adorned and externally protected by countless Buddhas and bodhisattvas.

In this light, we can consider the possibility that it was made specifically for enshrinement as a votive offering for external protection of the dharma, that is, protection of a Buddhist statue or painting.

3. Single-Sheet Buddhist Prints as Objects of Worship

3.1. Prints with Popular Icons for Worship

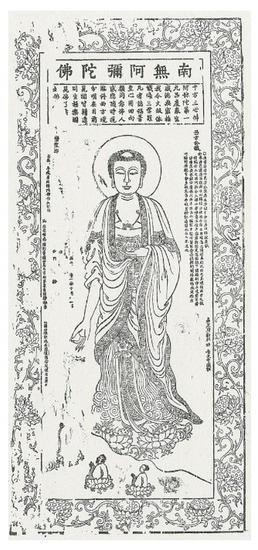

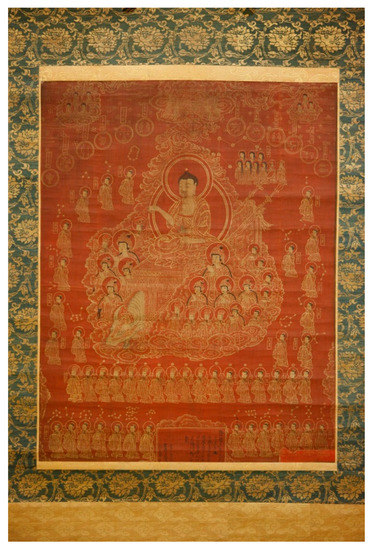

Across all regions where Mahayana Buddhism is followed, the favored icons of Buddhist art, regardless of time and region, are Sakyamuni Buddha, Amitabha Buddha and the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. Artworks featuring them greatly surpass others in both number and kind. That such works were also produced in the form of prints to be used as objects of worship can be easily confirmed through written records and extant examples. For example, Fascicle 5 of Pure Talks of the Jade Mug (Ch. Yu hu qing hua 玉壺淸話) compiled by Wenying 文瑩 is a Chinese record that states, “A print of Avalokitesvara was hanging in the sutra room of Beichan Temple 北禪寺 in Changsha during the Song dynasty”.14 An example of an extant woodblock used to produce prints for such purposes is the woodblock for the vertically long Descent of Amitabha (estimated to late Ming–early Qing), which is bordered on all four sides by a lotus blossom scroll design like a mounted Buddhist painting (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Descent of Amitabha (Ch. Amituo laiyingtu), late Ming–early Qing, 150.0 × 50.5 cm, The Museum of Ancient Asian Woodblock Prints. Source: (National Folk Museum of Korea 2016, p. 80).

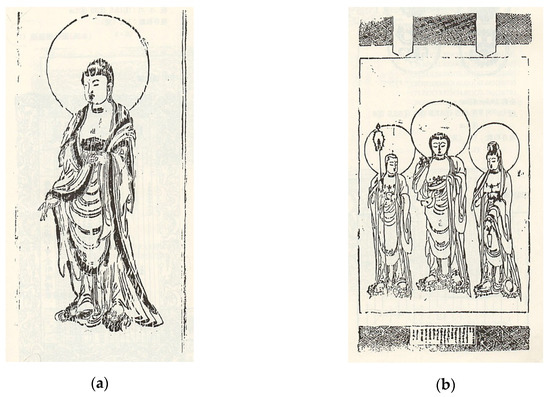

In Korea, in Janggyeongpanjeon 藏經版殿 (woodblock repository) at Haeinsa 海印寺 Temple, there is one woodblock that is carved with the Descent of Amitabha on the front and the Amitabha Triad on the back (Figure 7). The expression of the posture and attire of Amitabha, who stands slightly turned to the side with right hand held out to welcome the soul of a deceased individual, and the way Sthamaprapta, the bodhisattva who along with Avalokitesvara forms part of the Amitabha triad, is replaced in the woodblock with Ksitigarbha in response to trends in faith at the time are points that make the woodblock very similar to Descent of Amitabha and Amitabha Triad paintings from the Goryeo dynasty.15 Moreover, the repository at Haeinsa Temple where the woodblock is stored contains woodblocks only from the Goryeo and Joseon periods. However, there are no confirmed Joseon examples of the iconography of the pictures carved on the front and back. Hence, it is presumed that the woodblock was made during the Goryeo period or close to that time. The Amitabha Triad has a pattern band carved at the top and bottom. Decorative banners are also depicted hanging down at the top, and in the center of the bottom band is a space for the imprint, or the inscription giving the details of the woodblock (gangi 刊記), just like the space for the inscription on a painting (hwagi 畵記). These points suggest that the woodblock was made to produce prints with the same composition as a scroll painting. The fact that a large temple such as Haeinsa produced prints with the same visual form as Buddhist paintings gives us an idea of the efforts made to propagate Buddhism by mass-producing and distributing such prints to the ordinary people, for whom possession of a Buddhist painting was not realistically possible (due to the immense cost and time involved), thereby expanding the base of Buddhism and make it popular among the people.

Figure 7.

(a) Descent of Amitabha (K. Amitaba dokjon naeyeongdo) and (b) Amitabha Triad (K. Amitaba samjondo), presumed late Joseon—early Joseon, 50.0 × 33.0 cm, Haeinsa Temple. Source: (Park 1987, p. 365).

Consequently, it can also be surmised that, by late Goryeo to early Joseon at the latest, single-sheet Buddhist prints were being made and hung as objects of worship in place of paintings.16

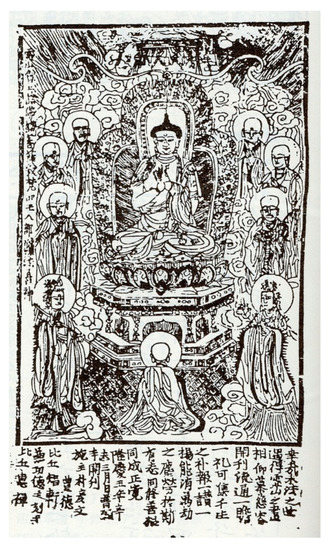

Another woodblock carved with the Assembly at Vulture Peak (1571) and currently preserved at Gaesimsa 開心寺 Temple in Seosan shows that the tradition of producing single-sheet Buddhist prints as objects of worship continued into the Joseon dynasty (Figure 8). Though a small print measuring 25.5 × 18.0 cm, it consists of the picture of the sermon and the imprint at the bottom, as commonly seen in altar paintings hung behind the icons in temple halls. The iconography is that of Sakyamuni giving a sermon on Vulture Peak. According to the inscription at the bottom, the print was produced for the purpose of “worshiping while looking at the picture to receive good fortune for one thousand lives, giving praise and having one’s sufferings extinguished for ten thousand eons, and doing pious deeds together so that all can attain enlightenment”. The inscription also says that, under the lead of Hyeseon 惠禪, the patron and carver of the woodblock, Park Eonmun 朴彦文, Pungdeok 豐德, and Jiheon 智軒also gave alms, and the first printing was carried out in the third month of the fifth Yunggeong 隆慶 year (1571) at Bowonsa 普願寺 Temple. Hyeseon, the person in charge of this project, is also mentioned as the carver and patron in the inscription of other works published at Bowonsa Temple, including the ritual texts Tiantai Perfect Meditation in the Shuilu Fahui Dharma Ritual (1565), Compendium of Ritual Texts (K. Jebanmun 諸般文) (1571)17 and Master Gaofeng’s Essentials of Chan (1571, Ch. Gaofeng hesang chanyo 高峰和尙禪要). Based on this evidence, it is believed that Hyeseon held a considerably high position at Bowonsa Temple at the time and led the publication of many Buddhist texts. From the stated objective of the Assembly at Vulture Peak print—“to engage in spiritual practice and attain enlightenment together”—it is evident that the work was not printed simply as an object of worship but to encourage spiritual practice. Moreover, on the left side of the print is an inscription (象王山普願寺佛殿造成供養勸○後世同成正覺) that tells us the picture was printed in large numbers in an effort to raise funds for construction of a temple hall at Bowonsa Temple, located on Mt. Sangwangsan.18 To sum up, this print of Assembly on Vulture Peak was produced by Hyeseon at Bowonsa Temple to raise funds for the construction of a new temple hall. It is therefore a valuable item whose inscription shows that the people of the time made Buddhist prints to be used for worship and for spiritual practice.

Figure 8.

Assembly at Vulture Peak (K. Yeongsan selbeopdo), Woodblock carved at Bowonsa Temple, Joseon (1571), 26.0 × 17.5 cm, Gaesimsa Temple, Seosan. Source: (Park 1987, p. 190).

3.2. Prints for Worship Reflecting Trends in Faith

Prints handed down from the Joseon dynasty show greater diversity in their iconography, and among them are some with distinctive iconography that not only serve as Buddhist prints as objects of worship but were produced in response to the trends and demands of Joseon Buddhism. In fact, the aforementioned Dharani of the Buddha of Immeasurable Life can also be placed in this category as it clearly reflects trends in spiritual practice during the latter half of the Joseon dynasty. However, as discussed above, it was made for the purpose of “external protection of the dharma” and is thus judged to be a dharani with the nature of a talisman. On the other hand, the works to be dealt with in this section are prints that reflect trends in faith at the time and were used for worship or spiritual practice and as such they have the same function as the prints for worship mentioned above in Section 3.1. However, they differ in that prints were made with new iconography or iconography that had been changed to reflect trends in faith, making them distinct from the prints of the preceding period featuring universal iconography. These prints, therefore, not only help us to understand aspects of Joseon Buddhist faith, through comparative study of Buddhist paintings from the periods before and after they also enable examination of the process of iconographic change in Joseon Buddhist paintings. They are hence important visual materials requiring in-depth research.

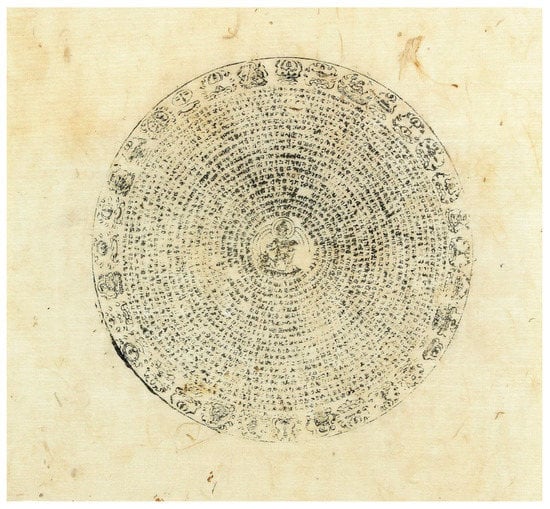

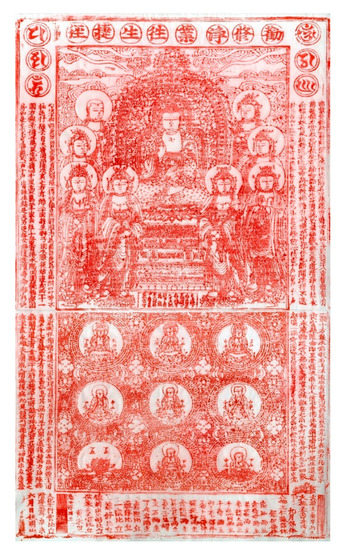

First, Shortcut to Rebirth through Buddha Mindfulness (K. Gwonsu jeongeop wangsaeng cheopgyeongdo 勸修淨業往生捷徑圖), which was repeatedly printed at many temples during the Joseon period, is a woodblock print produced to recommend, as the title says, a shortcut to rebirth in the Western Pure Land through right conduct (K. jeongeop 淨業), that is, practice through chanting the Buddha’s name (Amitabha). The oldest extant example is the print made at Ssanggyesa 雙溪寺 Temple on Mt. Bulmyeongsan 佛明山 (1571), preserved at Dongguk University Museum. Others include the print from Sinansa 身安寺 Temple, Geumsan 錦山 (1576); the print from Yeongwonsa 靈源寺 Temple, Mt. Jirisan 智異山 (1640), which is preserved at Ssanggyesa 雙溪寺 Temple in Hadong; the print from Unheungsa 雲興寺 Temple, Mt. Wonjeoksan 圓寂山 (1678), now preserved at Tongdosa 通度寺 Temple; and the print from Yeongwonam 靈源庵 Hermitage (1781) now preserved at Songgwangsa 松廣寺 Temple. All of these woodblock prints have been handed down intact.

The earliest of these prints, from Ssanggyesa Temple on Mt. Bulmyeongsan (1571) (Figure 9), has an imprint in perfect condition at the bottom that includes a list of patrons and states that the print was produced in the fifth Yunggyeong year (1571) with alms donated by many people. This picture of Shortcut to Rebirth through Buddha Mindfulness was carved on two woodblocks and the iconography on the print is composed of upper and lower tiers. The upper tier features a picture of Amitabha preaching, with Amitabha Buddha sitting on a high pedestal surrounded by a large aureole and flanked by eight bodhisattvas, four on each side. The lower tier features nine circles bordered with a bead design, set against a lotus pond background. This is an expression of the nine stages of rebirth in the Pure Land. The circles are arranged in three tiers, the upper tier, central tier and lower tier, each illustrating the middle grade, upper grade and lower grade of rebirth, respectively. Inside the circles, the icons in each of the nine grades are distinguished from each other. Those in the upper tier are expressed as bodhisattvas sitting on lotus pedestals, those in the upper and lower grade in the middle tier and the upper grade in the lower tier as monks sitting on lotus pedestals, while that in the middle grade of the lower tier is a torso on a lotus pedestal, and that in the lower grade of the lower tier is only a lotus pedestal. At the top of the print is the title of the work in Chinese characters, each character inside a circle. On the left and right sides of the title are three circles, each containing a separate character for the six-character Om mani pedme hum mantra. The record regarding carving of the woodblock is inscribed on the left and right sides of the illustrations. It details the conditions and methods of spiritual practice to achieve rebirth in the Pure Land through chanting, as well as the results of right conduct. To summarize, it says that, at the wishes of the monk Fazang 法藏, who later became the buddha Amitabha, anyone who chants the name of Amitabha can be reborn in the Western Paradise, and anyone who chants the name of Amitabha with true piety can be reborn in the pool of seven treasures in the Pure Land. As to the method, if one chants the name of Amitabha and makes offerings before this picture of the nine grades of rebirth at dawn every day for one year, facing the west, one will be reborn and be able to save bewildered sentient beings and lead them to nirvana.

Figure 9.

Shortcut to Rebirth through Buddha Mindfulness (K. Gwonsu jeongeop wangsaeng cheopgyeongdo), Woodblock carved at Ssanggyesa Temple, Eunjin, Joseon (1571), 39.0 × 56.4 cm, Dongguk University Museum. Photo by the author.

This concept of right conduct (or pure karma), a method of spiritual practice that involves focusing the mind and chanting the name of the Buddha to achieve rebirth and enlightenment at the same time, underlies the tradition of the dual practice of Seon 禪 (Ch. Chan, J. Zen) and Pure Land Buddhism.19 During the first half of the Joseon dynasty when different schools of Buddhism were merged under the Seon school, the widespread practice of chanting was combined with spiritual practice and developed as so-called “chanting Seon 念佛禪” (K. yeombulseon).20 If the meaning of this print is interpreted in light of the methods of spiritual practice at the time and the content of the written prayer that goes with it, this print of Shortcut to Rebirth through Buddha Mindfulness was produced for chanting practice and mediation to achieve rebirth in the Pure Land. Judging by its size and the content of the inscription, it was likely hung up on the western wall, the direction of Amitabha’s Pure Land, while engaged in chanting practice. Therefore, it is presumed that Shortcut to Rebirth through Buddha Mindfulness, which reflects trends in faith at the time, was printed in large numbers and distributed to many people to encourage them to engage in chanting and meditation for spiritual practice. Moreover, the popularity of chanting Seon can be confirmed from the fact that, as previously mentioned, prints of Shortcut to Rebirth through Buddha Mindfulness with the same iconography as the abovementioned Ssanggyesa Temple print (the earliest example) continued to be made thereafter. The various prints of the same subject made afterwards at several other temples show slight differences in arrangement of the icons and the finer details but have the same basic composition featuring Amitabha preaching and the nine grades of rebirth.

Next to be discussed are prints of the Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores, featuring the heaven store bodhisattva (Divyagarbhah, K. Cheonjang bosal 天藏菩薩), the earth store bodhisattva (Kṣitigarbha, K. Jiji bosal 持地菩薩), and the earth holder bodhisattva (also Kṣitigarbha, K. Jijang bosal 地藏菩薩) with their respective followers. It appears that paintings as objects of worship showing the three bodhisattvas as an independent icon first appeared during the Joseon dynasty. In regard to their origin, pictures of the Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores (K. Samjang bosal 三藏菩薩) were initially thought to have emerged as a reflection of the trikaya ideology (theory of the Buddha’s threefold bodies) and its expansion to belief in the three bodhisattvas who ruled the three realms. However, according to recent research, the origin of the Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores can be found in Suryukjae 水陸齋 ritual texts such as Suryuk mucha pyeongdeung jaeui chwaryo 水陸無遮平等齋儀撮要 from 1469 and Cheonji myeongyang suryukjaeui chanyo 天地冥陽水陸齋儀纂要 from 1470, where they are depicted on the middle altar of the rite.21 However, the argument has been raised that even prints and paintings of Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores thus produced show changes in iconography to reflect trends in faith.22

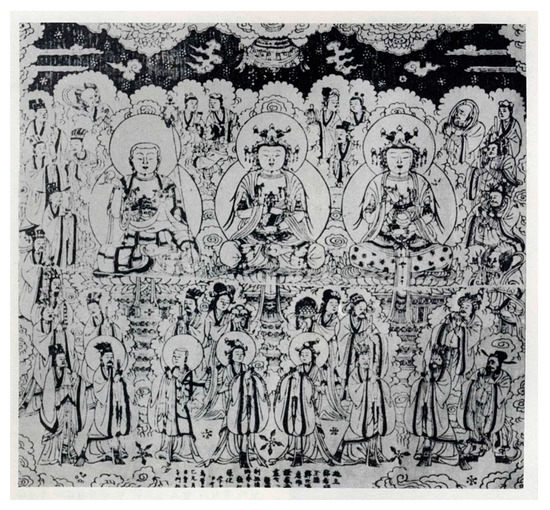

It is not known exactly when pictures of the three bodhisattvas were first produced. However, as the Joseon painting Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores dating to 1541 (preserved at Tamonji 多聞寺Temple, Japan) has been handed down to the present, it seems they were produced at least by the first half of the sixteenth century. Moreover, “Record of Dosoram 兜率庵 Hermitage on Mt. Geumgangsan” (“Geumgangsan dosoramgi 金剛山兜率庵記”) from 1548 states that “When Hyujeong 休靜 visited Dosoram on Mt. Geumgangsan he saw that an altar painting featuring the bodhisattvas Jiji-bosal [Kṣitigarbha, earth-store], Cheonjang-bosal [Divyagarbhah, heaven store] and Jijang [also Kṣitigarbha, earth holder] and twenty-four attendant devas and immortals hung on the Western wall”. This record confirms that in the mid-sixteenth century paintings of the three bodhisattvas of the three stores were enshrined in temple halls or hermitages.23 That the same iconography was also produced in prints around this time is evidenced by the print handed down at Hoeansa 會安寺 Temple in 1581 (Figure 10). This print shows Cheonjang-bosal sitting in the center flanked by Jiji-bosal and Jijang-bosal on the left and right, respectively, all of them sitting on high pedestals. Standing around them are countless followers. The iconography in this print reflects the transition from early paintings of the Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores, where their followers were not clearly identified, to the establishment of Jijang-bosal as ruler of hell beings, Cheonjang-bosal as ruler of devas and immortals, and Jiji-bosal as ruler of divinities. The Hoeansa print is, therefore, an important work that sheds light on the changing iconography of the Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores. The fact that pictures of the Three Bodhisattvas were carved onto woodblocks to be printed in mass quantities shows that belief in the Three Bodhisattvas had become widespread in the latter half of Joseon, influenced by the Suryukjae rites, which were frequently held on a private basis as a rite to guide souls of the dead to the next world. The popularity of the Three Bodhisattvas cult accompanying the popularity of Suryukjae is also confirmed by the concentrated production of pictures of the Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when temples were actively rebuilt and Buddhist paintings made in the aftermath of the Japanese invasion of Korea in 1592 and the Second Manchu invasion of Korea in 1636.

Figure 10.

Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores (K. Samjang bosaldo), Woodblock carved at Hoeansa Temple, Joseon (1581), 46.0 × 50.0 cm, Private collection. Source: (Gonggansa 1979, p. 42).

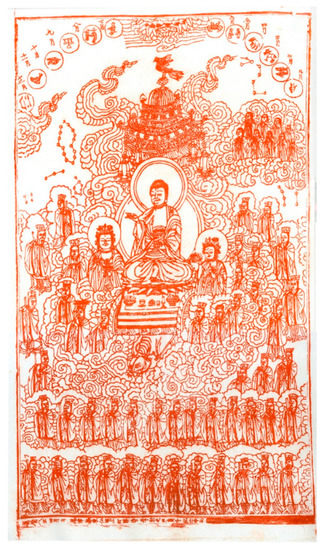

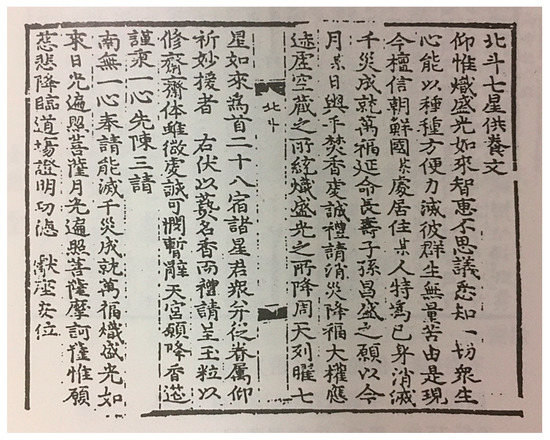

Lastly, the Descent of Tejaprabha Buddha print made at Ssanggyesa 雙溪寺 Temple in Eunjin in 1580 (Figure 11) is another example that reflects the forms of Buddhist faith that were popular among the ordinary people. The imprint at the bottom says that the printing woodblock was carved at Ssanggyesa Temple on Mt. Bulmyeongsan in Eunjin in the eighth Mallyeok 萬曆year (1580). Tejaprabha Buddha (Buddha of blazing light, K. Chiseonggwang yeorae 熾盛光如來) pictures emerged as Buddhism was syncretized with native folk beliefs. That they were also made in the form of single-sheet Buddhist prints indicates the widespread belief in Chilseong 七星, deification of the Seven Stars (Big Dipper), with Tejaprabha at the center. As a realistic measure to maintain the religious body during the Joseon dynasty, when the ruling ideology shifted to Confucianism, the Buddhist circle conducted varied rites to pray for good fortune in this life in response to the demands of the people.24 In relation to belief in the stars, rites were held frequently to Tejaprabha, the Big Dipper and other stars, and the oldest extant related ritual text is Bukduchilseong gongyangmun 北斗七星供養文 (ritual text for veneration of the Big Dipper) published at Gwangheungsa 廣興寺 Temple in Andong. Moreover, the woodblock of a ritual text of the same title preserved at Gapsa 甲寺 Temple (Figure 12) confirms that a copy from the same woodblocks was published at Ssanggyesa Temple in Eunjin in 1580.25 That is, the abovementioned print Descent of Tejaprabha Buddha and the ritual text Bukduchilseong gongyangmun were both published at the same temple in the same year. Consequently, it can be presumed that rites to the constellations were held so often that the woodblocks for the ritual text were carved again and that prints of the Descent of Tejaprabha Buddha would have been made for the distribution to the many people taking part in the rites.

Figure 11.

Descent of Tejaprabha Buddha (K. Chiseonggwang yeorae gangnimdo), Published at Ssanggyesa Temple, Eunjin, Joseon (1580), 83.0 × 39.5 cm, Private collection. Photo by the author.

Figure 12.

Ritual text for veneration of the Big Dipper (K. Bukduchilseong gongyangmun), Published at Ssanggyesa Temple, Eunjin, Joseon (1580), 19.2 × 11.5 cm, Gapsa Temple. Source: (Park 1987, p. 179).

The Ssanggyesa Temple print of the Descent of Tejaprabha Buddha depicts the Buddha in the center descending on the clouds sitting in an ox-drawn cart, flanked by saints and attendant bodhisattvas. The twelve palaces (constellations) and the Big Dipper have been arranged in the upper part of the picture and the twenty-eight mansions in three tiers in the lower part. When the Descent of Tejaprabha Buddha from Ssanggyesa Temple is compared with two earlier paintings of the same subject, one from the Goryeo dynasty in the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and a Joseon print made in 1569 and preserved at Korai 高麗 Museum in Kyoto, Japan (Figure 13), its overall structure is similar to the Joseon painting but the composition of the icons surrounding the Buddha and the order of the twelve palaces shows a connection with the Goryeo painting. In both of the earlier paintings, the twenty-eight mansions are arranged with seven each on the left and right sides of the Buddha and on the left and right sides of the bottom tier. The Ssanggyesa print, however, has them all arranged in three rows at the bottom, while Samtaeyukseong 三台六星 (six stars at the feet of the Big Bear constellation) and Namduyukseong 南斗六星 (six stars of the Southern Dipper), which are in the bottom tier of the other paintings, have been moved to the left and right. In the process of such change, some of the varied constellations were omitted and the number arrangement mixed up in the Ssanggyesa print. Of course, these changes can be regarded as iconographic stylization or simplification but they can also be interpreted in the context of the popularity of belief in Chilseong. That is, the changes are thought to be related to the shift in direction in Tejaprabha worship during the first half of the Joseon period from protection against natural disasters to prayers for longevity and health, thus resulting in a similar shift in object of worship to Chilseong, who controls life span and disease.26 Due to these trends in faith, the role of constellation deities in the Tejaprabha cult, aside from Tejaprabha, Chilseong, and the twenty-eight mansions, gradually weakened during the first half of Joseon. In the process, the artist monk who made the base drawing for the printing woodblocks may not have properly recognized stars such as Samtaeyukseong and Namduyukseong.

Figure 13.

Descent of Tejaprabha Buddha (K. Chiseonggwang yeorae gangnimdo), Joseon (1569), Ink and colors on hemp cloth, 84.8 × 66.1 cm, Korai Museum in Kyoto, Japan. Photo by Utaek Jeong in 2003.

4. Conclusions

In the history of Buddhist printmaking, single-sheet prints were produced before prints inserted as sutra illustrations. Therefore, early single-sheet Buddhist prints that have been handed down are very important materials not only in the history of printing but in terms of Buddhist iconography. Moreover, that the iconography of certain dharani or Buddhist paintings was carved onto woodblocks for mass printing reflected increased demand for such prints according to the popularity of cults related to certain icons. Hence, research on single-sheet Buddhist prints must be carried out not only in the field of Buddhist art history but also the history of Buddhism. However, despite the importance of the subject, the time and place of production and patron for single-sheet prints is in many cases unknown and related materials are scattered and not easily accessible. Consequently, for a long time no systematic research on single-sheet Buddhist prints was carried out. The turning point came when China began to publish compilations of Buddhist prints. In Korea, surveys were conducted on the number of printing woodblocks kept at temples and prints in private collections were made public. Based on these materials, this paper analyzed some of the major single-sheet Buddhist prints in terms of type and usage, and their content and significance.

The results show that two major types of single-sheet Buddhist prints were made: dharani-type prints that served as talismans and prints that were used for worship or spiritual practice. It is thought that the former types were made for the purpose of self-protection through acceptance and maintenance of faith, or for enshrinement in a Buddhist statue for the protection of that statue and to seek good fortune or protection through the merit of doing so, or to express one’s will to protect the dharma. Extant prints of Pratisara Dharani (an incantation for wish fulfillment), made only for the deceased in China, confirm that the same beliefs and iconography were transmitted to the Goryeo dynasty. However, considering that the same dharani was frequently enshrined in Buddhist statues as a votive offering, we can guess that it took on expanded meaning in Korea. In addition, Dharani of the Buddha of Immeasurable Life has a picture of Amitabha in the Pure Land and Diagram of the Avataṃsaka Single Vehicle Dharmadhatu arranged in the center with various talismans and mantras arranged on both sides, and it is interesting to see how clearly this reflects the popularity of Three Gates Buddhist practice during the latter half of Joseon. The various talismans and mantras on either side of the pictures in the center, when considering the structure of the dharani which seems to be protecting the icons from the outside, suggest that the print was made for enshrinement “to protect the dharma, that is, a sacred object”.

Buddhist prints made for worship and spiritual practice were generally used as visual aids in worship and chanting. They can be divided into those featuring icons universally loved throughout the ages such as Sakyamuni, Amitabha and Avalokitesvara, and those featuring icons reflecting the trends of certain periods. In the latter case, the prints were analyzed not only in relation to the favored Buddhist beliefs and methods of Buddhist spiritual practice but also the trends in faith among the ordinary people. For example, prints of Shortcut to Rebirth through Buddha Mindfulness gives us a glimpse at chanting Seon as a method of spiritual practice to achieve rebirth in the Pure Land. I also examined prints of the Three Bodhisattvas of the Three Stores, whose production was stimulated by the popularity of Suryukjae rites in the latter half of the Joseon period, and Descent of Tejaprabha Buddha, which reflect flourishing belief in the constellations, represented by the cult of Chilseong. From these works, it was possible to confirm that changes occurred in iconography according to trends in faith at different times.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Datang daci ensi sanzang fashi zhuan 大唐大慈恩寺三藏法師傳 Fascicle 6, Preserved at Chion-in Temple, Kyoto, Japan.Foshuo suiqiu jide dazizai tuoluoni shenzhou jing佛說隨求卽得大自在陀羅尼神呪經 Taishō 20, no.1153.Geumgangsan dosoramgi 金剛山兜率庵記, Cheongheojip 淸虛集.Pubian guangming qing jing chisheng ruyi bao yin xin wu neng sheng da ming wang da sui qiu tuoluoni jing 普遍光明清淨熾盛如意寶印心無能勝大明王大隨求陀羅尼經 Taishō 20, no.1154.Yuhu qinghua 玉壺淸話, Fascicle 5.Yunxian sanlu 雲仙散錄, Fascicle 5.Secondary Sources

- Central Buddhist Museum (佛敎中央博物館). 2014. Nirvana, the Ultimate Happiness. Yeolban, gungeukjeokui haengbok (涅槃, 궁극의 행복). Seoul: Central Buddhist Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Copp, Paul. 2014. The Body Incantatory: Spells and the Ritual Imagination in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dongguk University Academy of Buddhist Studies (동국대 불교학술원). 2017. Archives of Buddhist Culture Catalog of Old Buddhist Documents 1: Buddhist Documents of Wongaksa Temple (불교기록문화유산 아카이브사업단 고문헌 도록 1-원각사의 불교문헌). Seoul: Dongguk University Academy of Buddhist Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Dongguk University Press (동국대학교출판부). 1979. Complete Works of Korean Buddhism. (韓國佛敎全書). Seoul: Dongguk University Press, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Hanji (馮漢驥). 1957. Jitangyinben Tuoluoni Jingzhoude Fajian (記唐印本陀羅尼經呪的發見). Wenwu Cankao Ziliao (文物參考資料). Beijing: Zhonghua Renmin Gonghe Guo Wenhuabu Wenywuju Ziliaoshi (中華人民共和國文化部文物局資料室). [Google Scholar]

- Gonggansa (空間社). 1979. Space (空間) 139. Seoul: Gonggansa. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Myeonghee (정명희). 2013. Study on Rites at the Three-level Altar and Buddhist Paintings in Buddhist Rituals of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon sidae bulgyo uisikui samdanuirye wa bulhwa yeongu 朝鮮時代 佛敎儀式의 三壇儀禮와 佛畵 硏究). Ph.D. dissertation, Hongik University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Jinhui (정진희). 2017. Study on Belief in and Iconography of Chiseonggwang Buddha in the Joseon Dynasty (Hanguk chiseonggwan yeorae sinanggwa dosang yeongu 韓國 熾盛光如來 信仰과 圖像 硏究). Ph.D. dissertation, Dongguk University, Seoul, South Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kikutake, Junichi, and Jeong Utaek. 1997. (菊竹淳一·정우택). Goryeo Dynasty Buddhist Paintings (Goryeo sidaeui bulhwa 高麗時代의 佛畵). Seoul: Sigongsa. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Bomin (김보민). 2018a. Study on Goryeo Dynasty Pratisara Dharani: Focusing on Items Excavated from Buddhist Statues and Tombs (Goryeo sidae sugu tarani yeongu: Bulbokjang mit bunmyo chultopumeul jungsimeuro고려시대 隨求陀羅尼 연구: 불복장 및 분묘 출토품을 중심으로). Master’s dissertation, Myongji University, Seoul, South Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim Jahyun). 2018b. “Sixteenth Century Single-leaf Woodblock Prints from the Ssanggyesa Temple in Eunjin” (Eunjin ssanggyesaui 16 segi danpok byeonsang panhwa yeongu 恩津 雙溪寺의 16세기 單幅變相版畵 硏究). Misul sahak yeongu (미술사학연구) 300. Seoul: Hanguk misul sahakhoe (한국미술사학회), pp. 137–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim, Jahyun 김자현). 2017. Study on Early Joseon Buddhist Sutra Illustration Prints (Joseon jeongi bulgyo byeonsang panhwa yeongu朝鮮前期 佛敎變相版畫 硏究). Ph.D. dissertation, Dongguk University, Seoul, South Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jongsu (이종수). 2010. Study of Later Joseon Spiritual Practice: Focusing on Three Gates Practice (Joseon hugi bulgyoui suhaeng chegye yeongu-sammun suhakeul jungsimeuro조선후기 불교의 수행체계 연구- 三門修學을 중심으로). Ph.D. dissertation, Dongguk University, Seoul, South Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jongsu (이종수). 2015. “Background and Popularity of Later Joseon Avatamsaka Studies” (Joseon hugi hwaeomhakui yuhaenggwa geu baegyeong조선후기 화엄학의 유행과 그 배경). Korea Journal of Buddhist Studies (불교학연구) 16: 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Seung-hye (이승혜). 2018. “Visual Culture of Chinese Dharani Buried in Tombs: Focusing on Tang and Liao Dynasty Examples” (Jungguk myojang taraniui sigakmunhwa: Danggwa ryoui saryereul jungsimeuro중국 墓葬 陀羅尼의 시각문화: 唐과 遼의 사례를 중심으로). Korea Journal of Buddhist Studies (불교학연구) 19: 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yongyun (이용윤). 2005. “Later Joseon Paintings of the Three Buddhas of the Three Stores and Suryukjae Ritual Texts”. (Joseon hugi samjang bosaldowa suryukjae uisikjip 조선후기 삼장보살도와 수륙재의식집). Misul jaryo (미술자료) 72·73. Seoul: National Museum of Korea, pp. 91–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yongyun (이용윤). 2014. Study of Later Joseon Buddhist Paintings and Monk Fraternities of the Yeongnam Region (Joseon hugi yeongnamui bulhwawa seungnyeomunjung yeongu조선후기 영남의 불화와 승려문중 연구). Ph.D. dissertation, Hongik University, Seoul, South Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhitan (李之檀 主編), ed. 2008. Complete Works of Chinese Prints (Zhongguo banhua quanji 中國版畵全集) 1. Beijing: Zijincheng Chubanshe (紫禁城出版社). [Google Scholar]

- Nam, Heesook (남희숙). 2004. “Buddhist Ritual Proceedings During the Late Joseon Dynasty” (16-18 segi bulgyo uisikjipui ganhaenggwa bulgyo daejunghwa 16-18세기 佛敎儀式集의 간행과 佛敎大衆化). Hanguk munhwa(한국문화) 24. Seoul: Kyuganggak hanguk munhwa yeonguso (규장각한국문화연구소), pp. 97–165. [Google Scholar]

- National Folk Museum of Korea (국립민속박물관). 2016. Flower of the Printing Culture: Ancient Woodblock Prints (Insoe munhwaui kkot, gopanhwa인쇄문화의 꽃, 고판화). Seoul: National Folk Museum of Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Eungyeong (박은경). 2008. Study on Buddhist Painting of the First Half of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon jeongi bulhwa yeongu 조선전기 불화연구). Seoul: Sigong Art. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Sangguk (박상국), ed. 1987. Catalog of Woodblock Prints in Korean Temples (Jeonguk sachal sojang mokpanjip 全國寺刹所藏木板集). Seoul: Bureau of Cultural Properties (문화재관리국). [Google Scholar]

- Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage (불교문화재연구소). 2009. Wooden Seated Avalokitesvara of Bogwangsa Temple in Andong (Andong bogwangsa mokjo gwaneumbosal jwasang안동 보광사 목조관음보살좌상). Seoul: Cultural Heritage Administration and Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage (문화재청·(재)불교문화재연구소). [Google Scholar]

- Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage (불교문화재연구소). 2015. Buddhist Cultural Heritage of Korean Temples: 2014 Survey of Korean Temple Printing Woodblocks 2 (Hangukui sachal munhwajae-2014 jeonguk sachal mokpan iljejosa한국의 사찰 문화재-2014 전국 사찰목판 일제조사). Seoul: Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Ilgi (송일기). 2004. “Study on Books Enshrined in the Wooden Seated Amitabha of Jaunsa Temple in Gwangju” (Gwangju jaunsa amitabul jwasangui bokjang jeonjeokgo光州 紫雲寺 木造阿彌陀佛坐像의 腹藏典籍考). Seoji hakbo (서지학보) 28. Seoul: Hanguk seoji hakhoe (한국서지학회), pp. 79–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sudeoksa Museum (수덕사 근역성보관). 2004. Turning to the Buddha with a True Heart - Special Exhibition of Buddhist Enshrined Votive Offerings (Jisim gwimyeongrye-hanguk bulbokjang teukbyeoljeon至心歸命禮- 韓國佛腹藏 特別展). Sacheon-ri: Sudeoksa Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Uiduk University Press (위덕대학교 출판부). 2004. Korean Traditional Dharani (Hangukui jeontong tarani 韓國의 傳統陀羅尼). Gyeongju: Uiduk University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Lianxi, and Li Hongbo, eds. 2014. (翁連溪,李洪波 主編). Complete Works of Chinese Buddhist Prints (Zhongguo fojiao banhua quanji 中國佛敎版畵全集[全83冊]). Beijing: Zhongguo shudian (中國書店). [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Feng Zhi, Yun xian san lu 雲仙散錄, Fascicle 5 (Weng and Hongbo 2014, p. 19). |

| 2 | Daciensi sanzang fashi zhuan 大唐大慈恩寺三藏法師傳, Fascicle 6, preserved at Chion-in Temple, Kyoto, Japan. The “Jinkang incident” mentioned here refers to the siege and sacking of the Northern Song capital Kaifeng by Jin dynasty forces during the Jinkang era (1126–1127). This provides evidence that it was during the Song dynasty that the Monk Rizhi made prints of Amitabha and Avalokitesvara. |

| 3 | The date is estimated based on the seal reading “seal of Yongxing prefecture” 永興郡印 stamped on the back of this dharani, but the opinions of scholars differ, ranging from Northern Qi, Eastern Jin, and Northern Zhou depending on material used for evidence. However, generally, it is agreed that it was made during the Southern and Northern Dynasties. For more detail, see (Weng and Hongbo 2014, pp. 19–20; Li 2008, Figure 1 explanation). |

| 4 | Based on the imprint on this dharani mentioning the place name Chengdufu 成都府, which was established in 757, this dharani is thought to have been printed in the eighth century. (Lee 2018, p. 293). For more information regarding the publication period, see (Feng 1957). |

| 5 | Taishō 20, no.1153_001:617b04, Taishō 20, no.1154:637b19. In regard to the carrying of dharani on the body and accepting and maintaining faith shou chi 受持 in the dharani based on the sutras, see (Copp 2014, pp. 79–87). |

| 6 | Taishō 20, no.1153_001:0620c09, 0621b06, Taishō 20, no.1154:640b29. |

| 7 | (Lee 2018, pp. 291–92). |

| 8 | (Uiduk University Press 2004, p. 8). |

| 9 | For information on the Pratisara Dhrani enshrined in the Buddhist statue at Jaunsa Temple, see (Song 2004, pp. 85–87; Sudeoksa Museum 2004, Figure 57). |

| 10 | Taishō 20, no.1153:624a12-b08; Taishō 20, no.1154:641c29-642a08. (Kim 2018a, pp. 13–14). |

| 11 | Taishō 19, no, 1022B_001:713a02, 714a19. |

| 12 | (Dongguk University Academy of Buddhist Studies 2017, p. 469). |

| 13 | (Lee 2010, pp. 187–91; Lee 2015, pp. 67–72). |

| 14 | Wenying, Yu hu qing hua 玉壺淸話, Fascicle 5. |

| 15 | For information regarding Descent of Amitabha and Amitabha Triad paintings from the Goryeo dynasty, see (Kikutake and Jeong 1997, pp. 66–99). |

| 16 | (Kim 2017, pp. 232–39). |

| 17 | Jebanmun is a compendium of ritual texts from temples around the Korea that was put together for easy reference. |

| 18 | (Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage 2015, pp. 482–83). |

| 19 | Chan jing shuang xiu 禪淨雙修 emerged after the Tang dynasty in China when Chan temples introduced chanting into their spiritual practice and hence refers to combined meditation and chanting, which is the practice method of Pure Land Buddhism. |

| 20 | (Lee 2014, p. 197). |

| 21 | In Chinese ritual texts, the Suryukjae altar is divided into upper and lower altars, but, in Korean ritual texts, it is divided into upper, middle and lower altars. |

| 22 | For information regarding changes in iconography according to Suryukjae ritual texts, see (Park 2008, pp. 370–84); for information regarding changes in pictures of Samjang bosal according to Suryukjae ritual texts, see (Lee 2005, pp. 91–122); for information regarding changes in iconography reflecting trends in faith, see (Jeong 2013, pp. 140–44). |

| 23 | “Geumgangsan dosoramgi” 金剛山兜率庵記, Cheongheojip 淸虛集, Fascicle 3, Record 11 (Dongguk University Press 1979, p. 707). |

| 24 | (Nam 2004, pp. 136–39). |

| 25 | (Kim 2018b, pp. 161–62). |

| 26 | (Jeong 2017, pp. 118–20). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).