Abstract

A hospital admission presents various challenges for a patient which often result in high or intense spiritual needs. To provide the best possible care for older adults during hospitalization, it is essential to assess patients’ spiritual needs. However, little research has been done into the spiritual needs of geriatric patients. This article seeks insight into what is known in the literature on the spiritual needs of geriatric patients. This integrative review presents a summary of the articles on this topic. To select eligible studies, the PRISMA Flow Diagram was used. This resulted in ten articles that have been reviewed. Results show (1) a wide interest in researching spiritual needs, using different research designs. In addition, (2) four subcategories of spiritual needs can be distinguished: (a) the need to be connected with others or with God/the transcendent/the divine, (b) religious needs, (c) the need to find meaning in life, and (d) the need to maintain one’s identity. Moreover, results show that (3) assessing spiritual needs is required to provide the best possible spiritual care, and that (4) there are four reasons for unmet spiritual needs. Further research is needed on the definition of spiritual needs and to investigate older patients’ spiritual needs and the relation with their well-being, mental health and religious coping mechanisms, in order to provide the best spiritual care.

1. Introduction

In recent years, spirituality has become an indispensable part of both research on aging and the care of older adults (MacKinlay and Trevitt 2007; Peteet et al. 2019; Stanley et al. 2011). More and more research acknowledges the role of spirituality for older patients’ well-being and recognizes the prevalence of spiritual needs in aging (Koenig et al. 1995; Manning 2012; Moberg 2005; Wink and Dillon 2002; Weber and Pargament 2014). Unmet spiritual needs are reported and often related to health concerns, especially during hospital admissions (Hodge et al. 2012; Okon 2005; Ross 1997). This is in line with earlier prominent research that argues “that illness or hospitalization may prevent individuals from having their spiritual needs met and therefore prevent them from attaining their optimum health potential” (Ross 1995).

Moreover, addressing older patients’ spiritual needs is important if their spiritual experiences are to be acknowledged (Selman et al. 2018). Assessing spiritual needs provides insight into the meaningful spiritual experiences of people, into people’s spiritual resources and into what is important in people’s lives. In order to provide the best possible care and to recognize people’s spiritual experiences, it is essential to identify and assess their spiritual needs (Erichsen and Büssing 2013; Hodge et al. 2012; Mackinlay 2001; Monod et al. 2010b).

Despite the increasing recognition of the presence of spiritual needs in aging people, there is still no clear definition of the concept of spiritual needs and no unanimity on which constructs belong to spiritual needs (Polley et al. 2016; Sharma et al. 2012).

Frequently mentioned spiritual needs by researchers and older patients are the need to find meaning and purpose in life, the need for belonging, the need for connectedness, the need for inner peace and the need for love (Erichsen and Büssing 2013; Galek et al. 2005; Hermann 2007; Murray et al. 2004; Ross 1995). Also indicated and often mentioned as a spiritual need is the need to have a relationship with God or with the divine (Man-Ging et al. 2015; Troutman-Jordan and Staples 2014). Although a distinction has been made in literature between spirituality and religion, spiritual and religious needs intertwine. These concepts are intertwined and often used interchangeably by older patients themselves, especially in research with older adults or with their caregivers (Musick et al. 2000; Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Thauvoye et al. 2019). For example, in spiritual needs questionnaires, religious needs such as the need for connection with God or with the divine, are often categorized as a subcategory of spiritual needs (Büssing et al. 2010; Hermann 2006; Monod et al. 2010a; Taylor 2006).

Despite the overall consensus in literature on the role of spirituality in late life, insights into specific spiritual needs in late adulthood are lacking (Carver and Buchanan 2016; Davis 2005; Lavretsky 2010; MacKinlay and Burns 2017; Moberg 2008). Most research on spiritual needs is carried out with chronic disease patients, patients at the end of life and cancer patients (Büssing et al. 2010; Hermann 2006; Lazenby 2018; Murray et al. 2004; Yong et al. 2008). This stands in contrast to the small amount of research into the spiritual needs of older adults (e.g., Erichsen and Büssing 2013; Hodge et al. 2012). Discerning insight into the spiritual needs of hospitalized older adults is required if the best possible spiritual care is to be provided, especially given the growing population of older adults (Eurostat 2019).

Two noteworthy reviews have been conducted on the topic of older adults’ spiritual needs. The qualitative meta-synthesis of Hodge et al. (2012) discusses nine studies on older adults’ spiritual needs in healthcare settings. The review presents five interrelated categories of spiritual needs and provides the first meta-synthesis on this topic. Despite the clear overview and analysis in this work, five out of the nine articles included were published before 2000. Moreover, the review includes multiple healthcare or living settings of older adults such as outpatient hospices, hospitals, long-term care facilities and patients living at home, whereas our aim is to clarify the spiritual needs in geriatric wards. The second review concentrates on the spiritual needs of older adults in residential care facilities (Gautam et al. 2019). This integrative review incorporates seven recent studies with qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches. The article provides clear insights into the concept of spiritual needs and spiritual care from the perspective of residents and caregivers. These fruitful insights provide crucial information on the prevalence of spiritual needs in long-term care, but might differ from spiritual needs reported in a hospital setting, as discussed in this review.

Although these two reviews are indispensable, an up to date review on the spiritual needs of older adults in geriatric wards in hospitals is lacking. There is an increasing need to obtain more information on geriatric patients’ spiritual needs to include these needs in spiritual care. An overview of the current state of the research into geriatric patients’ spiritual needs is relevant.

This integrative review aims to outline what is known in literature about the spiritual needs of older adults in hospitals in the last two decades. Four subquestions will be addressed. Firstly, what kinds of studies have been done on geriatric patients’ spiritual needs? Secondly, what kinds of spiritual needs are reported by older patients or their caregivers? Thirdly, how are the stages of identifying spiritual needs and providing spiritual care described and related to each other? Fourthly, what are the reasons for the frequently reported unmet spiritual needs of geriatric patients? Finally, a critical evaluation is provided in the discussion.

2. Materials and Methods

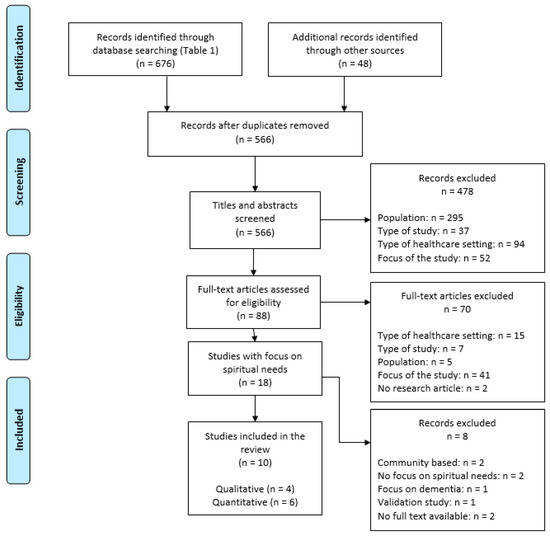

In this study, an integrative review was applied in order to include heterogeneous designs such as qualitative and quantitative research methods (Knafl et al. 2017; Whittemore and Knafl 2005). An integrative review offers a comprehensive overview of the current state of research, formulates recommendations for further research and defines the missing research paths in literature (Russell 2005). Based on the framework of Whittemore and Knafl (2005), four methodological stages were conducted. Firstly, we searched for relevant articles in electronic databases and reference lists with help from experts and researchers. In this stage, the search strategy was formulated and implemented in the different databases. In the second stage, the PRISMA Flow Diagram was used to identify, screen and select eligible articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Moher et al. 2009). After the selection of articles, the third stage of the process consisted of data evaluation to assess the quality of the articles obtained. Lastly, the articles were analyzed and presented. Mendeley reference management software was used to store, manage and organize the articles obtained. During these processes, Microsoft Excel was used to classify the information from the articles.

2.1. Search Strategy

The integrative review process demands an extensive and well-defined search strategy to avoid missing articles and incomplete datasets (Conn et al. 2003; Whittemore and Knafl 2005). Six electronic databases were consulted: PubMed, Web of Science, ATLA, Cinahl, Scopus and Embase. Those databases were chosen because of their relevant resources in medical sciences or their focus on spirituality or religion. The last search was completed on 27 April 2020 by the first author.

The first search category contains the subject of the review; namely spiritual needs or spiritual concerns, sometimes referred to as spiritual distress. As already mentioned, spiritual and religious needs intertwine and thus both terms were included in the search strategy. In order to obtain a broad overview of the subject, the terms in this category were truncated to include all relevant key terms (spiritual*, relig* or pastoral*1). The second search category narrows the population down to older adults, with the exclusion of older adults in residential care or in nursing homes. The third search category identifies the healthcare setting; namely hospitals. For each database, the search string was adapted to the modalities of the database, as shown in Table 1. Worth mentioning is that the number of search results in PubMed was high (n = 383), due to the use of the Mesh Term ‘aged’, which provided a broad range of results. In addition to research involving older patients, research with a mix of older patients and adolescents, emerging adults and middle adults showed up in the PubMed results.

Table 1.

Overview of the search strategy: database, results and search terms. The search terms were combined in each database. TI = Title, TS = Topic.

The broad search strategy ensured a representative overview of current research in this field. Additional records were identified through reference lists from the obtained publications, from the reviews of Hodge et al. (2012) and Gautam et al. (2019) or were provided by experts and researchers. Following the PRISMA flow diagram, illustrated in Figure 1, duplicates were removed before the titles, abstracts and full texts of the articles were screened. If full texts were missing or important information was lacking, the first author was contacted. For each search string, the results were limited to the last 20 years.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study selection process, PRISMA Flow Diagram (Moher et al. 2009).

The publications were screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Selected articles should include older adults (the participants in the research should be aged 65 years and over), should contain an empirical study (not a review, theoretical consideration or commentary), will be limited to research in geriatric wards in hospitals (exclusion of psychiatry, long term care, consultation centers, hospices, outpatient clinics, residential care, nursing homes or community-dwelling older adults), should focus on spiritual needs, should be written in English, French, German or Dutch and should have been published in the last twenty years (2000–2020).

2.2. Data Selection

Based on the criteria mentioned above, three stages of selecting and screening articles were performed, as illustrated in Figure 1. In the first stage of screening titles and abstracts, studies were included (n = 88) if the focus of the study was on spirituality, religion or pastoral care. In the second stage of screening, articles were included if the focus of the study was on spiritual needs (n = 18). This means that articles in the second stage were, among others, excluded if the focus of the study (n = 41) was on spiritual well-being (n = 9), religious or spiritual coping (n = 8), interventions (n = 4), religiosity (n = 12) or spirituality (n = 8). The distinction between those two stages was made to maintain a broad scope of views in the first screening and a narrower focus in the second screening. At the final stage, the undecided articles were read carefully and reevaluated. Eight records were excluded due to their focus on community-dwelling older adults (n = 2), due to their lack of focus on spiritual needs (n = 2), due to their focus on people with dementia (n = 1), due to their focus on the validation process (n = 1) or due to their lack of full text (n = 2). Following the PRISMA Flowchart, the selection process resulted in ten studies which are discussed in this review (Moher et al. 2009).

2.3. Data Evaluation

To evaluate the quality of the data, different quality appraisal tools are used in integrative reviews (Hopia et al. 2016). As Whittemore and Knafl (2005) argue, no gold standard is formulated to assess the quality of research. In line with the integrative review of Gautam et al. (2019), the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was applied to assess the quality of the articles, as shown in Table 2 (Hong et al. 2018). Three questions of the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) and three questions of the Risk of Bias Instrument for Cross-Sectional Surveys of Attitudes and Practices were added to assess the quality of the four qualitative and six quantitative articles respectively in more detail (Agarwal et al. 2011; CASP UK 2013).

Table 2.

Overview of the quality appraisal using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Hong et al. 2018). Probably Y = probably yes = some aspects of the questions are confirmed in the study-others not, Y = yes, C = can’t tell, N = no.

Based on the two general screening questions of the MMAT2, we can conclude that the articles describe clear research questions and that the collected data permit addressing the research questions. In line with this, the MMAT shows that all the qualitative approaches used in the qualitative studies are appropriate to answer the research question3.

Considering the qualitative studies, the quality appraisal tool CASP showed two important shortcomings in two studies. Firstly, the relationship between the researcher and participants was not mentioned in two qualitative studies (Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Shih et al. 2009). Secondly, both of these studies did not describe how many patients refused to participate and why they refused to participate in the recruitment strategy (Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Shih et al. 2009). Additionally, the case study of Mundle (2015) cannot provide general results, as it reports findings based on one person. By presenting a detailed report of the spiritual history, spiritual narratives, spiritual distress and spiritual needs of an older patient, this case study offers insights into possible characteristics of spirituality and spiritual needs as experienced by older persons.

Reflecting on the quantitative studies, the quality appraisal tool MMAT and the Risk of Bias Instrument for Cross-Sectional Surveys of Attitudes and Practices show that the reasons for not participating4, risk of nonresponse bias5, missing data6 and face validity of the survey instrument7 are often not discussed. In summary, the risk of bias in qualitative and quantitative studies is briefly mentioned or not mentioned at all in the articles. Most of the time, it is unknown to what extent the researchers have taken this into account. However, it is important to identify and avoid bias in research to interpret the results of the studies correctly.

While defining the results of the studies in this review, the possible risk of bias in the studies and the limitations of the survey instruments were considered. The evaluation of all ten studies—published between 2004 and 2019—is reported in Table 2.

2.4. Data Analysis

The main focus of this data analysis is to identify common patterns and themes and to provide an overview of current research and recommendations for further research. Each article was read several times and key information for each article was classified, analyzed and compared with data from the other studies. Thereafter recurring concepts, ideas or outcomes of data comparison were clustered and represented in this article (Whittemore and Knafl 2005).

Four topics will be discussed in this review to address the four subquestions, mentioned at the beginning of this review. Firstly, the characteristics of the studies are described. Secondly, the main subcategories of spiritual needs of geriatric patients are defined. Thirdly, the complementary processes of identifying spiritual needs and providing spiritual care are outlined. Finally, the reasons for unaddressed spiritual needs are illustrated.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies

For each study, the authors, the publication year, the geographical location, the sample and healthcare setting, the aim or objective of the study and the design of the study are reported in Table 3. The measurement tool for spiritual needs used in the study, the conclusions of the study related to patients’ spiritual needs and the general conclusion of the study are also summarized in this table. In this part, more information is provided on the characteristics of the studies. The religious and medical background of the patients, the exclusion criteria, the hospital setting, and the measurement tools for spiritual needs are described in more detail.

Table 3.

Overview of study characteristics of reviewed publications.

The articles represent seven distinct studies and three similar studies. These three studies were written by the same lead author using the same research design in different subpopulations of a single national sample (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015). Although these three studies were published in three different articles, they are part of the same data set. The results of the three studies, which are similar to each other, will be considered as one investigation in the review analysis (Dijkers 2018).

In line with the geographical heterogeneity as shown in Table 3, the religious background of the participants differs in the various articles. One study focused on Muslim patients (Sönmez and Nazik 2019), one study mentioned a majority of patients with a Judeo-Christian background (Monod et al. 2012), two studies included Christian patients (Mundle 2015; Ross and Austin 2015), one study included Muslim and Catholic older adults (Narayanasamy et al. 2004) and one study contained a mix of different religious backgrounds such as Buddhism, Protestantism and Catholicism (Shih et al. 2009). Surprisingly, four studies did not pay attention to people’s religious background (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015; Ramezani et al. 2019).

Despite extensively reported information on the sample characteristics in the studies, little is reported about the medical background of the participants. Two studies questioned older patients at the rehabilitation unit (Monod et al. 2012; Mundle 2015), two studies explored the spiritual needs of older adults at the end of life (Ross and Austin 2015; Shih et al. 2009) and the majority of participants in the Turkish study had cancer or heart failure (Sönmez and Nazik 2019). In the five remaining studies, the medical background was not extensively explained (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015; Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Ramezani et al. 2019).

In general, the articles included patients aged 65 years and over8. Some studies defined more detailed exclusion criteria. In five studies participants with cognitive impairment, incomplete questionnaires, patients with severe dementia, people suffering from alcohol abuse or mental illness or unconscious patients, were excluded (Monod et al. 2012; Ramezani et al. 2019; Ross and Austin 2015; Shih et al. 2009; Sönmez and Nazik 2019). The exclusion criteria for the other studies are mentioned briefly; namely, the exclusion of people under 65 (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015; Mundle 2015; Narayanasamy et al. 2004). Eight articles investigated spiritual needs exclusively through questioning older patients. One study examined the spiritual needs of aged patients from the nurses’ perspective and one article questioned patients together with their informal caregivers (Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Ross and Austin 2015).

The ten publications cover research conducted in hospital settings, except for the study by Ross and Austin (2015) which included participants living at home. These participants had often been admitted to hospital during the research and had been identified through hospital databases. An exception has been made for this study due to its high relevance for older patients’ spiritual needs and frequent hospitalizations. In line with this, the studies by (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015) were conducted at the moment the patients were discharged from the hospital. However, the data in these studies focus on spiritual needs during their hospital stay and thus contain fruitful information.

Finally, spiritual needs have been researched using various kinds of measurements. Four studies asked participants one single question about the degree of addressed spiritual needs, the extent of spiritual needs or the intensity of spiritual needs, rated on a 5-point Likert Type scale (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015; Sönmez and Nazik 2019). Two other studies evaluated the unmet spiritual needs and determined the prevalence of spiritual distress with the Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool by Monod (Monod et al. 2012; Mundle 2015). The study carried out by Ramezani et al. (2019) assessed spiritual needs using the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire by Büssing et al. (2010). The study conducted with the nurses identified older patients’ spiritual needs by use of the critical incident technique (Flanagan 1954; Narayanasamy et al. 2004). Finally, the two remaining studies used multiple open-ended questions to measure spiritual needs (Ross and Austin 2015; Shih et al. 2009).

Despite the small number of studies, the variety of countries and religious backgrounds shows that there is a wide interest in identifying, assessing and addressing people’s spiritual needs. This section has concentrated mainly on the differences between the studies. However, there are also similarities across the studies, as shown in the following sections.

3.2. The Subcategories of Spiritual Needs

The majority of the articles provide an overview of various definitions or conceptualizations of spiritual needs or spirituality, based on previous research. Spiritual needs are perceived as inherent to human beings and as one of the deepest human needs (Ramezani et al. 2019). Authors agree that spirituality is a basic human need and that spiritual needs are expressions of people’s inner being (Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Shih et al. 2009). Moreover, spirituality is described as the essence of human beings and as giving a person humanity (Sönmez and Nazik 2019). Monod et al. (2012) emphasizes that spiritual needs provide information about the current spiritual state of people and represent patients’ intimate feelings at a certain moment in time, such as during hospital admission. Nevertheless, the articles do not provide a clear definition of spiritual needs.

Four subcategories of spiritual needs are frequently mentioned by the research participants in the studies; i.e., the need to be connected with others or with God/the transcendent/the divine, religious needs, the need to find meaning in life, and the need for maintaining identity.

One of the most frequently indicated dimensions of older patients’ spiritual needs is the need for connection. The need to feel connected with others such as family and significant others is prominent. In the study with Muslim patients, the need to see friends and family scores highest along with religious needs (Sönmez and Nazik 2019). In general, the need to receive support from family, the need to connect with others, the need to feel close to significant others and the need for belonging and meaningful relationships score highly (Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Mundle 2015; Ramezani et al. 2019; Ross and Austin 2015). The Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool deepens the need for connection as “the need for connection with his or her existential foundation” (Monod et al. 2012). Besides this, the connection with God, the transcendent or the divine is also frequently noted. For example, in the study by Ramezani et al. (2019) “requesting help from God” is reported as the most intense need. This need to communicate with God is also reported in the study with the nurses (Narayanasamy et al. 2004).

Of equal importance and overlapping with the need for connection with God/the transcendent/the divine, is the frequently mentioned subcategory of religious needs. The Muslim patients in Sönmez and Nazik’s study (2019) report a high amount of religious needs such as praying, reading religious texts and attending religious services. Also, three other studies report the need to pray, to take communion, the need for absolution, the need to transcend the worldly being or the need to practice religion (Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Ramezani et al. 2019; Ross and Austin 2015). These needs represent a wide spectrum of religious needs. This is not surprising, as the religious backgrounds of the respondents of these studies differ. As most of the existing studies focus on a rather homogeneous sample in terms of religious background or do not report the religious background of participants, these studies could not investigate the possible correlation between religious needs and specific religious backgrounds of patients. More research is needed on the relation between patients’ religious identity, religious salience and religious involvement and their religious needs.

Another subcategory among older patients is the issue of meaning in life which is described in different studies. Four studies report the need for meaning in life during hospitalization, such as making sense of their illness or searching for a sense of purpose in life (Monod et al. 2012; Mundle 2015; Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Ross and Austin 2015). This is in line with other research reporting that finding meaning in life can help people cope with life stressors (Park and Baumeister 2017). At the same time, the search for meaning in life can become problematic due to life challenges that come with aging such as experiences of loss, reduced physical health, shrinking social networks and the proximity of death experiences (Pinquart 2002; Turesky and Schultz 2010; Vachon et al. 2009; Yoon 2006).

Finally, in parallel with the search for meaning in life is the need for maintaining identity, reported in two studies using the SDAT (Monod et al. 2012; Mundle 2015). Monod et al. (2012) identify this category as the need “to be loved, to be heard, to be recognized, to be in touch, to have a positive image of oneself and to feel forgiven”. Previous research shows that maintaining identity is related to maintaining dignity in the process of aging, especially through respectful and attentive interactions (Lloyd et al. 2020).

In sum, spiritual needs are specified as a multidimensional concept made up of a vertical and horizontal dimension (Monod et al. 2012). This is in line with other research in other populations where a distinction between a vertical and horizontal dimension in spiritual needs can be distinguished (Offenbaecher et al. 2013; Riklikienė et al. 2020; Taylor 2006). The vertical dimension can be considered to be the connection with a higher being, transcendent, God or divinity. The horizontal dimension consists of aspects such as the search for meaning, feeling connected with others, achieving inner peace needs, being with family, belonging and maintaining identity (Monod et al. 2012; Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Ramezani et al. 2019; Sönmez and Nazik 2019). In line with the subcategories, these two dimensions of spiritual needs are distinguished, but at the same time are overlapping and complementary.

Despite the cultural differences in the studies, similar spiritual needs are found across different groups. For example, Ross and Austin (2015) investigated patients’ spiritual needs in South Wales and compared them with Murray’s research (2004) in Edinburgh, but no differences were found. Also the three studies by (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015) report the same conclusion, despite the different cultural background of the participants. Although the results in these studies show no cultural differences, (Hodge et al. 2013; Hodge and Wolosin 2015) report in the studies with Latino and African Americans the wide variety of spirituality between individual patients sharing the same cultural background and between groups of patients from various ethnicities. For example, (Hodge et al. 2013; Hodge and Wolosin 2015) declare that African Americans report higher spiritual needs compared to other groups and that Latino Americans’ spirituality is characterized by a belief in a “vibrant, non-material reality”.

Besides the cultural variety in the studies, patients also have different religious backgrounds. To take into account the spiritual or religious affiliations of people, Mundle’s research (2015) gives attention to patients’ spiritual history and spiritual background in healthcare by use of narrative inquiry. Mundle’s case study (2015) shows that spiritual needs are related to the spiritual history of patients. For example, the spiritual experiences of the female patient during her childhood and her experiences in the church affect her current spiritual needs. The majority of the studies barely mention the link between patients’ religious affiliation and spiritual needs.

3.3. The Stages of Assessing Spiritual Needs and Providing Spiritual Care

In this section, insights into the two complementary stages in the process of taking care of patients’ spiritual needs, namely identifying and addressing spiritual needs, will be discussed. We start with an important distinction that needs to be made when identifying spiritual needs, followed by the role of the healthcare and chaplaincy team to address spiritual needs. All insights are based on the articles in this review, whether or not linked or compared to prior research.

3.3.1. Identifying Spiritual Needs

In the identifying process of investigating spiritual needs, studies make a distinction between the nature of spiritual needs and the degree of met or unmet spiritual needs.

On the one hand, if research wants to gain insight into which spiritual needs geriatric patients consider meaningful, the value of spiritual needs should be questioned. For example, “Do you have the following needs?” or “Are these practices spiritual requirements for you?”. These questions investigate the nature, the amount or the intensity of spiritual needs (Ramezani et al. 2019; Sönmez and Nazik 2019).

On the other hand, if we want to gain insight into the extent to which spiritual needs are recognized and met during hospitalization, an additional question is needed that explicitly assesses the degree of fulfillment. For example, in the three studies by (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015), the degree to which hospital staff addressed spiritual needs is questioned. These questions investigate the extent to which spiritual needs are met during hospitalization. The distinction between met and unmet spiritual needs is also included in the study by Mundle (2015) and Monod et al. (2012) by use of the Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool. The SDAT explores patients’ spiritual needs and identifies if these spiritual needs are met or unmet (ibid). A scoring system is provided to rate the degree of unmet spiritual needs on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no unmet need) to 3 (severe unmet need). The total score, ranging from 0 (no distress) to 15 (severe distress), is the sum of the different unmet spiritual needs scores. Spiritual distress is defined if the total score is ≥5 and thus high levels of unaddressed spiritual needs are reported (Monod et al. 2010a, 2012).

In other words, it must be pre-determined whether the assessed spiritual needs should be a representation of the nature, amount or intensity of spiritual needs generally or a representation of the degree of (un)addressed spiritual needs. Therefore, a clear differentiation between assessing spiritual needs as assessing patients’ spiritual framework on the one hand, and measuring the degree of assessed spiritual needs as assessing the extent to which needs may or may not be met during hospitalization on the other hand, is required.

3.3.2. Addressing Spiritual Needs

The integrated articles focus in the first place on identifying or assessing spiritual needs. However, gaining insight into patients’ spiritual needs is inextricably linked to addressing spiritual needs (Shih et al. 2009). In other words, taking care of spiritual needs is just as essential as gaining a deeper understanding of spiritual needs. Seven out of ten reviewed articles researched the spiritual needs of geriatric patients and formulated the adjusted spiritual care that is needed to meet these needs (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015; Mundle 2015; Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Ross and Austin 2015; Shih et al. 2009).

Based on the articles in this review, the most prominent issue, besides defining best practices of spiritual care, is who will take care of meeting these spiritual needs. In general, the seven articles discussing spiritual care ascribe spiritual interventions to the entire healthcare team of the hospital ward. These studies presume that spiritual care is the shared responsibility of each caregiver and is in line with insights from previous research (Kruizinga et al. 2018).

More specifically, (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015) describe the aim of addressing patients’ spiritual needs as a collaborative responsibility. This call for shared responsibility is based on four predictors of met spiritual needs, identified in general healthcare. These predictors are the quality of relations with nurses, the communication with physicians, the discharge process and the room quality. These four variables function as a predictor of satisfaction with how spiritual needs of geriatric patients during hospitalization are addressed (Hodge and Wolosin 2015; Hodge et al. 2013). In sum, (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015) report that spiritual care is the task of the whole healthcare team and that spiritual care should be integrated into the healthcare process. This is in line with the preferences of patients in the study of Ross and Austin, reporting that spiritual needs can be fulfilled by the whole healthcare team (Ross and Austin 2015). Moreover, two articles specifically describe the vital role of nurses in addressing spiritual needs (Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Shih et al. 2009).

In addition to the common focus on the healthcare team as best placed to address patients’ spiritual needs, the fundamental role of chaplains in spiritual care is mentioned. Patients and caregivers report that an encounter with the chaplain is indispensable in assessing and addressing patients’ spiritual needs (Mundle 2015; Ross and Austin 2015). Previous research focusing on chaplaincy care underlines, in line with the integrated studies, the complementarity of the healthcare team and the chaplain in identifying and meeting spiritual needs. Often, the healthcare team refers to the chaplain if they become aware of a deeper spiritual need or concern. Thereafter, chaplains undertake a more in-depth spiritual assessment and a more extensive spiritual intervention based on their professional background and training (Fitchett 2017; Handzo and Koenig 2004; Kestenbaum et al. 2017).

However, one must check whether patients need someone from the healthcare team to address and meet their spiritual needs, or whether they can cope or fulfill these needs by themselves, without help from the healthcare team. For example, in the study by Sönmez and Nazik (2019), Muslim patients report high spiritual needs, although these needs were mostly fulfilled by patients themselves. In other words, there is a discrepancy between being able and being unable to cope with spiritual needs, as noted in the SDAT before. This tool explicitly evaluates whether patients are able to cope with their own spiritual needs. Patients who are incapable of formulating coping mechanisms and are not able to manage their spiritual needs score higher levels of spiritual distress and need spiritual support (Monod et al. 2012).

3.4. Why Spiritual Needs Remain Unmet

The patients interviewed in the studies report a high number of unmet spiritual needs and a lack of spiritual care (Ramezani et al. 2019; Ross and Austin 2015). Four reasons for unmet spiritual needs are identified by the authors in this review.

Firstly, the authors argue that spiritual needs receive little attention in healthcare and research and that there is insufficient evidence of the nature of spiritual needs or spiritual interventions (Narayanasamy et al. 2004; Ross and Austin 2015). Monod et al. (2011, 2012) claim an imbalance between the high amount of research done into patients’ spiritual history and the small amount of research conducted into patients’ current spiritual status. They report that multiple instruments are developed to assess patients’ spirituality in terms of behaviors and attitudes in contrast to the limited number of tools to assess patients’ current spiritual needs. Moreover, incorporated studies acknowledge that spiritual assessment is not sufficiently integrated into research and into holistic care (Hodge and Wolosin 2015; Ross and Austin 2015).

Secondly, a lack of knowledge, competence and training to address spiritual needs is disclosed in the articles (Shih et al. 2009). The lack of educational programs causes uncertainty and reticence in healthcare staff to discuss spiritual needs with patients (Mundle 2015). More training, guidance and coaching is needed to activate spiritual care in healthcare (Hodge et al. 2013; Sönmez and Nazik 2019). This is in line with other research noting the absence of spiritual care in nursing education (Lewinson et al. 2015). Moreover, nurses report this shortcoming as the most frequent barrier to providing spiritual support (Balboni et al. 2014; Cone and Giske 2017; Rogiers et al. 2019).

The third reason for unmet spiritual needs is time restrictions and is briefly noted in one of the articles (Hodge et al. 2016). This is similar to other studies reporting that members of the healthcare staff are aware of patients’ spiritual needs, but have too little time to examine patients’ spiritual concerns (Daudt et al. 2019; Keall et al. 2014).

Last but not least, spiritual issues are often perceived as intimate and personal topics both for patients and caregivers (Mundle 2015). One of the barriers to address spiritual needs is the lack of familiarity with common spiritual needs (Hodge et al. 2016). Also reported is the discomfort with assessing spiritual needs, communicating about spirituality and assuming that patients prefer not to express their spiritual concerns (Mundle 2015). This is contrary to studies demonstrating older patients’ preference to include spirituality during their illness or treatment (Ross and Austin 2015; Stanley et al. 2011).

4. Discussion

Central to this study is the synthesis and analysis of initial findings on older patients’ spiritual needs, outlined in the studies included. This overview seeks to gain insight into what is known in literature about this topic, what kind of research has been done and how spiritual needs are defined across the different studies. Ten studies were obtained on the basis of a systematic approach. The results of the integrative review provide insights into the main characteristics of the various studies, into the spiritual needs most frequently reported by geriatric patients, into the complementary processes of assessing and addressing spiritual needs, and into the issue of unmet spiritual needs. Additionally, the subcategories of spiritual needs discussed in this review will be compared with the results of two reviews on older adults’ in different hospital settings and with the results of studies with other populations such as cancer patients, palliative patients and patients with dementia.

This review is about spiritual needs subcategories as reported by geriatric patients. Although patients’ spiritual needs are often split up and categorized, spiritual needs remain dynamic and unique, based on the cultural, ethnical, spiritual and geographical background of patients. The spiritual needs’ subcategories disclosed in this review are partially consistent with previous findings. The review on spirituality in older adults living in residential care facilities already noted the need for interconnectedness and the need to find meaning in life as two main spiritual needs (Gautam et al. 2019). In line with this, the outlined spiritual needs in this study overlap with the synthesis by Hodge et al. (2012) which also points out the prevalence of the need for interpersonal connection, the need for relationship with God and the need for meaning and purpose. Also, in other populations such as cancer patients, palliative patients and people with dementia, some studies show that the need to feel connected with self, others and God and the need to find meaning in life are prominent (Grant et al. 2004; Lazenby 2018; Odbehr et al. 2017). Different from these studies with cancer patients and palliative patients is the high prevalence of the need for maintaining identity and religious needs reported by some studies with older adults (Gautam et al. 2019; Grant et al. 2004; Lazenby 2018; Man-Ging et al. 2015; Odbehr et al. 2017). Büssing et al. (2018) study reveals that the prevalence of religious needs also differs between age groups. People aged 70 years and over scored higher on religious needs compared to younger people in this study. However, not all studies with older adults report high levels of religious needs. The research of Erichsen and Büssing (2013) with older adults in nursing homes reports low prevalence of religious needs. Finally, little attention is given in the studies of this review to the need for (inner) peace compared to other studies. For example, in the study of Grant et al. (2004) with palliative patients, the need for peace of mind is linked with the perspective and fear of death, which is also pointed out in the reviewed study of Shih et al. (2009). In two other studies in this review, the need for peace is mentioned as a positive outcome of spiritual care or positively related to spiritual distress (Monod et al. 2012; Narayanasamy et al. 2004). Finally, the study of Ramezani et al. (2019) shows that the need for inner peace is reported by 85 out of 100 patients. However, the need for inner peace was not mentioned extensively in the reviewed studies. Given the small amount of research on geriatric patients’ spiritual needs, more research is needed to estimate to what extent the geriatric patients’ spiritual needs are similar or different from other groups of people.

Secondly, this review shows the link between assessing and addressing patients’ spiritual needs and outlines the distinction between met and unmet spiritual needs. Also, the role of the healthcare team and the chaplain in assessing and addressing spiritual needs is discussed. In line with the model of Handzo and Koenig (2004), spiritual care is a shared responsibility of the whole healthcare team in which the chaplain is the professional spiritual caregiver, while other caregivers assess spiritual needs and refer to the chaplain if spiritual needs crop up. However, spiritual needs can also be assessed by the chaplain. For example, assessing patients’ spiritual needs by the SDAT-tool by Monod et al. (2010a) is embedded in the relationship between the patient and the chaplain. At the same time, spiritual needs can also be addressed by other health professionals, supported by and in collaboration with the chaplain (Koenig 2014). In sum, the complementarity between chaplains and other caregivers is essential to assess and address patients’ spiritual needs.

In contrast to the focus on assessing and addressing spiritual needs, the outcomes of spiritual care are lacking in these studies, compared to the increasing focus on outcome-oriented research in spiritual care. Outcome-oriented chaplaincy is especially gaining more attention and seeks to investigate the added value of spiritual care on patients’ well-being, quality of life or mental health (Jankowski et al. 2011; Kruizinga et al. 2016; Snowden and Telfer 2017). Addressing patients’ spiritual needs, on the one hand, is related to higher well-being (Park and Sacco 2017). Unmet spiritual needs, on the other hand, are associated with poorer well-being, lower care satisfaction, and less quality of life (Astrow et al. 2018; Pearce et al. 2012). Although outcome-oriented research is increasing, the reviewed studies did not include this outcome-paradigm in their research. However, some authors are aware of the effects of spiritual care on patients’ well-being. For example, Mundle (2015) argues that the use of narrative frameworks as a focus of spiritual care has therapeutic effects on older patients’ spiritual health. Moreover, Ross and Austin (2015) presume an increase in quality of life, spiritual well-being and a decline in loneliness and hospital admissions if spiritual care is offered to homebound geriatric patients. In line with this, Ramezani et al. (2019) advise addressing spiritual needs, as this is linked to fewer depressive symptoms and lower disease duration. Also, Sönmez and Nazik (2019) briefly describe the positive effect of fulfilled spiritual needs on life expectation. Finally, Hodge et al. (2016) prove that addressing spiritual needs is associated with higher overall satisfaction with service provision. Yet, only one study in this review explores briefly the outcomes of spiritual care. The study conducted with nurses reports two outcomes of nurses’ interventions to address spiritual needs. On the one hand, nurses report the positive effects on patients and their families such as achieving inner peace and experiencing gratitude and, on the other hand, nurses describe the positive effects on themselves such as feeling happier (Narayanasamy et al. 2004). In summary, research is needed on the whole process of spirituality, starting with identifying the spiritual needs of geriatric patients when they enter the hospital, followed by providing spiritual care during hospitalization, and concluding with investigating the outcomes of spiritual care provided by the healthcare or chaplaincy team.

Thirdly, this review discovered that spiritual needs remain often unmet and that there is an urgent need for exhaustive empirical research in different cultural contexts in order to obtain a complete overview of older patients’ spiritual needs. Four reasons for spiritual needs unaddressed during hospitalization were given in the articles and mentioned in this review. One of the factors is that there is fundamental research missing on this subject. This is in line with the small number of articles obtained from a database search during this review. Complementary, educational programs should include training courses on spiritual care and spiritual assessment in the light of the holistic care paradigm. In particular, the complex relationship between experiencing spiritual needs, reporting spiritual needs, and asking for spiritual care must be included in educational programs. Surprisingly, research shows that patients reporting high spiritual needs are not more likely to apply for spiritual care (Fitchett et al. 2000). In other words, spiritual concerns are not often articulated spontaneously, unless the healthcare team explicitly asks for this (Nelson-Becker et al. 2007). This means that in order to gain insight into the spiritual needs of patients, active inquiry-based working is required and should be taught to healthcare staff.

In sum, this study responds to the broader interest in gaining more insight into the spiritual needs of geriatric patients. For example, addressing patients’ spiritual needs in healthcare is encouraged by the World Health Organization (2017) which demands “health systems and services to address the multidimensional needs of older adults in an integrated way to grant effective care”. In addition, the “forgotten factor of spirituality” is mentioned more and more in addition to the classical framework of successful aging (Baltes and Baltes 1990; Crowther et al. 2002; Swinton 2001; Rowe and Kahn 1997). A remarkable shift took place in this framework from a binominal, idealistic discourse of successful aging towards a holistic and person-centered approach to aging, based on the bio-psycho-social-spiritual model (Atchley 2011; MacKinlay 2006; Malone and Dadswell 2018; Puchalski et al. 2009; Sulmasy 2002). Although the importance of spirituality is mentioned in the contemporary interpretation of successful aging, the framework of successful aging is still mainly based on maximizing health, cognitive capacity and participation in social activities on the one hand, and minimizing dependency, losses and disabilities on the other hand (Baltes and Baltes 1990; Depp and Jeste 2006; Flatt et al. 2013; Mowat 2004; Rowe and Kahn 1997).

5. Limitations

Although this study provides a good synopsis of current research on aging patients’ spiritual needs, this review has four limitations.

Firstly, due to the limited studies and their wide variety, any conclusions must be drawn with caution. It is not appropriate to compare the content of the studies without considering their various backgrounds. As already mentioned, the studies are conducted in a wide variety of countries and with patients from different cultural and religious backgrounds. Moreover, the studies serve distinctive purposes and the spiritual needs are measured in different ways. Apart from Monod’s Spiritual Distress Assessment Tosol (Monod et al. 2010a, 2012), most assessment scales are rarely adapted to the specific context and needs of older patients. The variety of measurements in the studies, combined with a small number of participants, limits the possibility of generalizing results in this review. Moreover, the majority of the articles maintains a cross-sectional design that prevents results being obtained from causal conclusions. In other words, the reviewed articles provide initial findings that must be further investigated.

Secondly, five out of ten studies do not fully meet the inclusion criteria set in this review. Although inclusion criteria were limited to older adults in hospitals9, four studies include older adults who were discharged from hospital (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015) or community-dwelling patients (Ross and Austin 2015). Besides this, Narayanasamy et al. (2004) include nurses instead of patients and the patients in the study by Ross and Austin (2015) were at home. Also, some important information is missing from the articles. For example, there is little information provided on the relationship between the religious or spiritual background of the participants and their spiritual needs. Moreover, information on the relationship between researcher and patients10, risk of nonresponse bias, missing data, and reliability and validity of the survey instrument is missing.

Thirdly, three out of ten studies are by (Hodge et al. 2013, 2016; Hodge and Wolosin 2015). As already mentioned, the research designs and samples are similar across the three studies, but split up into several subsamples and subsequent publications. We took this into account during the analysis, yet this can cause a distorted overview of the research results. Also, the results of Mundle’s research (2015) should be interpreted with caution. The case study is a representation of one patient’s specific context and needs. This research is included, as the importance of case studies in spiritual care is increasing and case studies provide initial findings for further research (Fitchett 2020; Fitchett and Nolan 2015).

Finally, grey literature i.e., reports, newsletters, and presentations are not included in the research. Moreover, publication bias must be considered. Studies including averaging null effects are mostly not published and might have an influence on the findings in this review (Rosenthal 1979).

6. Future Research

Future research needs to incorporate three important components in order to address current knowledge gaps concerning spiritual needs in geriatric care.

In the first place, the relationship between spiritual needs and aspects of older patients’ well-being and mental health needs to be examined. For example, research with heart failure patients shows that unmet spiritual needs are associated with a decrease in well-being (Park and Sacco 2017). Also, in the study of Pearce et al. (2012) with cancer patients, results show that unmet spiritual needs are associated with an increase of depressive symptoms. In this review, only one out of ten articles included investigates the relationship between spiritual needs and depressive symptoms (Ramezani et al. 2019). The results of this study are in line with previous research showing a correlation between spiritual needs and depressive symptoms (Erichsen and Büssing 2013; Pearce et al. 2012; Offenbaecher et al. 2013). In the other studies in this review, research is missing on the relationship between spiritual needs and aspects of well-being and mental health in order to enhance holistic care.

Secondly, it would be good to identify the religious coping mechanisms of geriatric patients in addition to the assessment of spiritual needs11. It is important to assess the religious coping framework of patients to get insight into how and to what extent people use religion to cope with challenging aspects in life and how these ways of religious coping can help us to understand their evaluation of spiritual needs (Ellis et al. 2013). Moreover, religious coping might be included, because higher levels of religious coping are reported in geriatric patients, compared to other groups (Bosworth et al. 2003; Pargament et al. 2004, 2011). For example, Pargament et al. (2004) researched the role of positive and negative religious coping in geriatric patients. Positive religious coping was a predictor of increased health, while negative religious coping was a predictor of declining health. Distinguishing between positive and negative religious coping is not always that evident. Pargament et al. (2011) explain that, although positive religious coping is often helpful, this does not mean that this is true for every individual in every single situation. Although negative religious coping is often related to health problems, it can also function as a possibility of growth, transformation or religious development. Moreover, positive and negative religious coping can be used simultaneously (Fitchett et al. 2004; O’Brien et al. 2019).

Thirdly, more unanimity on which aspects belong to spirituality and on which categories belong to the term ‘spiritual needs’, would be helpful for further research. In general, two conceptualizations of spirituality have been defined in the broader research field, affecting the concept of spiritual needs. On the one hand, spirituality is described with a main focus on “the search for the sacred or connection to the transcendent” (Hill et al. 2000; Koenig 2008; Pargament and Mahoney 2005). This means that spirituality from this point of view is mostly defined by its link with the sacred or transcendent and its exocentric focus (Appleby et al. 2018). Aspects such as “optimism, forgiveness, gratitude, meaning and purpose in life, peacefulness, harmony and general well-being” are considered as intrapersonal variables mainly studied within the field of psychology and mental health (Koenig 2008). On the other hand, spirituality is often used as an umbrella concept, describing spirituality as “a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred” and as “expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices” (Puchalski et al. 2014). This focus on spirituality from a more anthropocentric point of view (Appleby et al. 2018), is in line with the framework of spiritual care studies (Mesquita et al. 2017; Ross and Miles 2020).

Descriptions of spiritual needs in the articles included in this review are in line with this broad definition of spirituality, i.e., the definition of Christina Puchalski et al. (2014). Spiritual needs are categorized in this review as the need to be connected with others or with God/the transcendent/the divine, religious needs, the need to find meaning in life and the need for maintaining identity. In general, the use of the terms ‘spirituality’ and ‘spiritual needs’ remains quite confusing. In this review, various definitions of spirituality have been used by the authors based on existing frameworks. On the one hand, in the study of Narayanasamy et al. (2004), spirituality is defined as “a relationship with a transcendent God/an ultimate reality, or whatever an individual values as supreme”. Also, Sönmez and Nazik (2019) mention that in Turkey “spirituality is related to religion and the creator”. On the other hand, Ross and Austin (2015) define spirituality in terms of seeking “hope and strength, trust, meaning and purpose, forgiveness, love and relationships, belief and faith, values, morality, creativity and self expression”. In future research, it might be useful to compare articles from different points of views on spirituality and spiritual needs in order to gain more insights into the specificity of the definition of these terms.

7. Conclusions

The small amount of research on geriatric patients’ spiritual needs contrasts with the growing interest in the role of spirituality in healthcare. Current research conducted in this research field differs in regard to geographical context, religious and cultural background of participants, research designs and measurement methods. Moreover, there is no clear definition of spiritual needs.

Despite the diversity of studies, some results are identical across the articles. Firstly, spiritual needs are formulated as a multidimensional concept and characterized by four main subcategories, i.e., the need to be connected with others or with God/the transcendent/the divine, religious needs, the need to find meaning in life and the need for maintaining identity. Secondly, the studies underscore the reciprocal relationship between spiritual needs and spiritual care. In addition, the shared responsibility of the healthcare team in addressing spiritual needs is formulated. Finally, the problem of unaddressed spiritual needs during hospitalization is recognized.

We can conclude that further research is needed to investigate older patients’ spiritual needs and the relation with health outcomes if the best spiritual care is to be provided. Although testimonials of hospital chaplains speak about spiritual needs of geriatric patients, more robust empirical research is needed, in order to be able to base these experiences and practices of chaplains—assessing and addressing spiritual needs—on empirical data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D., J.D., A.V. and A.D.; Methodology, L.D., J.D., A.V. and A.D.; Validation, A.D.; Formal Analysis, L.D.; Investigation, L.D.; Resources, L.D., J.D., A.V. and A.D.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, L.D.; Writing-Review & Editing, L.D., J.D., A.V. and A.D.; Visualization, L.D.; Supervision, A.D.; Project Administration, L.D.; Funding Acquisition, J.D., A.V. and A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Foundation - Flanders (FWO) grant number [G070919N].

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Jane Elizabeth McBride for her help in writing this article.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Agarwal, Arnav, Gordon H. Guyatt, and Jason W. Busse. 2011. Risk of Bias Instrument for Cross-Sectional Surveys of Attitudes and Practices. Available online: https://www.evidencepartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Risk-of-Bias-Instrument-for-Cross-Sectional-Surveys-of-Attitudes-and-Practices.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Appleby, Alistair, Philip Wilson, and John Swinton. 2018. Spiritual Care in General Practice: Rushing in or Fearing to Tread? An Integrative Review of Qualitative Literature. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 1108–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astrow, Alan B., Gary Kwok, Rashmi K. Sharma, Nelli Fromer, and Daniel P. Sulmasy. 2018. Spiritual Needs and Perception of Quality of Care and Satisfaction with Care in Hematology/Medical Oncology Patients: A Multicultural Assessment. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 55: 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atchley, Robert C. 2011. How Spiritual Experience and Development Interact with Aging. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 43: 156–65. [Google Scholar]

- Balboni, Michael J., Adam Sullivan, Andrea C. Enzinger, Zachary D. Epstein-Peterson, Yolanda D. Tseng, Christine Mitchell, Joshua Niska, Angelika Zollfrank, Tyler J. Vanderweele, and Tracy A. Balboni. 2014. Nurse and Physician Barriers to Spiritual Care Provision at the End of Life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 48: 400–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, Paul B., and Margret M. Baltes. 1990. Psychological Perspectives on Successful Aging: The Model of Selective Optimization with Compensation. In Successful Aging. Edited by Paul B. Baltes and Margret M. Baltes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, Paul S., Daniel Beckman, James Trippi, Richard Gunderman, and Colin Terry. 2008. The Effect of Pastoral Care Services on Anxiety, Depression, Hope, Religious Coping, and Religious Problem Solving Styles: A Randomized Controlled Study. Journal of Religion and Health 47: 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, Hayden B., Kwang-Soo Park, Douglas R. McQuoid, Judith C. Hays, and David C. Steffens. 2003. The Impact of Religious Practice and Religious Coping on Geriatric Depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 18: 905–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Hans-Joachim Balzat, and Peter Heusser. 2010. Spiritual Needs of Patients with Chronic Pain Diseases and Cancer-Validation of the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire. European Journal of Medical Research 15: 266–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Daniela Recchia, Harold Koenig, Klaus Baumann, and Eckhard Frick. 2018. Factor Structure of the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire (SpNQ) in Persons with Chronic Diseases, Elderly and Healthy Individuals. Religions 9: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, Lisa F., and Diane Buchanan. 2016. Successful Aging: Considering Non-Biomedical Constructs. Clinical Interventions in Aging 11: 1623–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASP UK. 2013. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). 10 Questions to Help You Make Sense of Qualitative Research. Available online: http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Cone, Pamela H., and Tove Giske. 2017. Nurses’ Comfort Level with Spiritual Assessment: A Study among Nurses Working in Diverse Healthcare Settings. Journal of Clinical Nursing 26: 3125–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, Vicki S., Sang-Arun Isaramalai, Sabyasachi Rath, Peeranuch Jantarakupt, Rohini Wadhawan, and Yashodhara Dash. 2003. Beyond MEDLINE for Literature Searches. Journal of Nursing Scholarship Second Quarter 35: 177–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, Martha R., Michael W. Parker, W. A. Achenbaum, Walter L. Larimore, and Harold G. Koenig. 2002. Rowe and Kahn’s Model of Successful Aging Revisited: Positive Spirituality-The Forgotten Factor. The Gerontologist 42: 613–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daudt, Helena, Margo D’Archangelo, and Dominique Duquette. 2019. Spiritual Care Training in Healthcare: Does It Really Have an Impact? Palliative and Supportive Care 17: 129–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, Bonnie. 2005. Mediators of the Relationship between Hope and Well-Being in Older Adults. Clinical Nursing Research 14: 253–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depp, Colin A., and Dilip V. Jeste. 2006. Definitions and Predictors of Successful Aging: A Comprehensive Review of Larger Quantitative Studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 14: 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkers, Marcel. 2018. Duplicate Publications and Systematic Reviews: Problems and Proposals. KT Update 6: 1–12. Available online: https://ktdrr.org/products/update/v6n2/dijkers_ktupdate_v6n2-508.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Ellis, Mark R., Paul Thomlinson, Clay Gemmill, and William Harris. 2013. The Spiritual Needs and Resources of Hospitalized Primary Care Patients. Journal of Religion and Health 52: 1306–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erichsen, Nora-Beata, and Arndt Büssing. 2013. Spiritual Needs of Elderly Living in Residential/Nursing Homes. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. 2019. Ageing Europe–Looking at the Lives of Older People in the EU. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/10166544/KS-02-19%E2%80%91681-EN-N.pdf/c701972f-6b4e-b432-57d2-91898ca94893 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Fitchett, George. 2017. Recent Progress in Chaplaincy-Related Research. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling 71: 163–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitchett, George. 2020. The State of Art in Chaplaincy Research. Needs, Resources and Hopes. In Learning from Case Studies in Chaplaincy. Towards Practice Based Evidence and Professionalism. Edited by Renkse Kruizinga, Jacques Körver, Niels den Toom, Martin Walton and Martijn Stoutjesdijk. Utrecht: Eburon. [Google Scholar]

- Fitchett, George, and Steve Nolan, eds. 2015. Spiritual Care in Practice: Case Studies in Healthcare Chaplaincy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fitchett, George, Peter M. Meyer, and Laurel Arthur Burton. 2000. Spiritual Care in the Hospital: Who Requests It? Who Needs It? Journal of Pastoral Care 54: 173–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitchett, George, Patricia E. Murphy, Jo Kim, James L. Gibbons, Jacqueline R. Cameron, and Judy A. Davis. 2004. Religious Struggle: Prevalence, Correlates and Mental Health Risks in Diabetic, Congestive Heart Failure, and Oncology Patients. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 34: 179–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, John C. 1954. The Critical Incident Technique. Psychological Bulletin 51: 327–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flannelly, Kevin J., George F. Handzo, and Andrew J. Weaver. 2004. Factors Affecting Healthcare Chaplaincy and the Provision of Pastoral Care in the United States. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling 58: 127–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatt, Michael A., Richard A. Settersten, Jr., Roselle Ponsaran, and Jennifer R. Fishman. 2013. Are “Anti-Aging Medicine” and “Successful Aging” Two Sides of the Same Coin? Views of Anti-Aging Practitioners. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 68: 944–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galek, Kathleen, Kevin J. Flannelly, Adam Vane, and Rose M. Galek. 2005. Assessing a Patient’s Spiritual Needs a Comprehensive Instrument. Holistic Nursing Practice 19: 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, Sital, Stephen Neville, and Jed Montayre. 2019. What Is Known about the Spirituality in Older Adults Living in Residential Care Facilities? An Integrative Review. International Journal of Older People Nursing 14: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Elizabeth, Scott A. Murray, Marilyn Kendall, Kirsty Boyd, Stephen Tilley, and Desmond Ryan. 2004. Spiritual Issues and Needs: Perspectives from Patients with Advanced Cancer and Nonmalignant Disease. A Qualitative Study. Palliative & Supportive Care 2: 371–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handzo, George, and Harold G. Koenig. 2004. Spiritual Care: Whose Job Is It Anyway? Southern Medical Journal 97: 1242–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, Carla P. 2006. Development and Testing of the Spiritual Needs Inventory for Patients near the End of Life. Oncology Nursing Forum 33: 737–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, Carla P. 2007. The Degree to Which Spiritual Needs of Patients near the End of Life Are Met. Oncology Nursing Forum 34: 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, Peter C., Kenneth I. Pargament, Ralph W. Hood, Michael E. Mccullough, James P. Swyers, David B. Larson, and Brian J. Zinnbauer. 2000. Conceptualizing Religion and Spirituality: Points of Commonality, Points of Departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 30: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, David R., and Robert J. Wolosin. 2015. Failure to Address African Americans’ Spiritual Needs during Hospitalization: Identifying Predictors of Dissatisfaction across the Arc of Service Provision. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 58: 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, David R., Violet E. Horvath, Heather Larkin, and Angela L. Curl. 2012. Older Adults’ Spiritual Needs in Health Care Settings: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Research on Aging 34: 131–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, David R., Robert J. Wolosin, and Robin P. Bonifas. 2013. Addressing Older Latinos’ Spiritual Needs in Hospital Settings: Identifying Predictors of Satisfaction. Advances in Social Work 14: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, David R., Christopher P. Salas-Wright, and Robert J. Wolosin. 2016. Addressing Spiritual Needs and Overall Satisfaction with Service Provision among Older Hospitalized Inpatients. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society 35: 374–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Quan Nha, Pierre Pluye, Sergi Fàbregues, Gillian Bartlett, Felicity Boardman, Margaret Cargo, Pierre Dagenais, Marie-Pierre Gagnon, Frances Griffiths, Belinda Nicolau, and et al. 2018. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) User Guide. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/ (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Hopia, Hanna, Eila Latvala, and Leena Liimatainen. 2016. Reviewing the Methodology of an Integrative Review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 30: 662–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, Katherine R. B., George F. Handzo, and Kevin J. Flannelly. 2011. Testing the Efficacy of Chaplaincy Care. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 17: 100–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keall, Robyn, Josephine M. Clayton, and Phyllis Butow. 2014. How Do Australian Palliative Care Nurses Address Existential and Spiritual Concerns? Facilitators, Barriers and Strategies. Journal of Clinical Nursing 23: 3197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kestenbaum, Allison, Michele Shields, Jennifer James, Will Hocker, Stefana Morgan, Shweta Karve, Michael W. Rabow, and Laura B Dunn. 2017. What Impact Do Chaplains Have? A Pilot Study of Spiritual AIM for Advanced Cancer Patients in Outpatient Palliative Care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 54: 707–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafl, Kathleen, Robin Whittemore, and Frances Hill Fox. 2017. Top 10 Tips for Undertaking Synthesis Research. Research in Nursing & Health 40: 189–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2008. Concerns about Measuring “Spirituality” in Research. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196: 349–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2014. The Spiritual Care Team: Enabling the Practice of Whole Person Medicine. Religions 5: 1161–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G., Harvey J. Cohen, Dan G. Blazer, Harold S. Kudler, K. Ranga Rama Krishnan, and Thomas E. Sibert. 1995. Religious Coping and Cognitive Symptoms of Depression in Elderly Medical Patients. Psychosomatics 36: 369–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruizinga, Renske, Iris D. Hartog, Marc Jacobs, Joost G. Daams, Michael Scherer-Rath, Johannes B. A. M. Schilderman, Mirjam A. G. Sprangers, and Hanneke W. M. Van Laarhoven. 2016. The Effect of Spiritual Interventions Addressing Existential Themes Using a Narrative Approach on Quality of Life of Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psycho-Oncology 25: 253–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruizinga, Renske, Michael Scherer-Rath, Hans J. B. A. M. Schilderman, Christina M. Puchalski, and Hanneke H. W. M. van Laarhoven. 2018. Toward a Fully Fledged Integration of Spiritual Care and Medical Care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 55: 1035–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavretsky, Helen. 2010. Spirituality and Aging. Aging Health 6: 749–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazenby, Mark. 2018. Understanding and Addressing the Religious and Spiritual Needs of Advanced Cancer Patients. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 34: 274–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinson, Lesline P., Wilfred Mcsherry, and Peter Kevern. 2015. Spirituality in Pre-Registration Nurse Education and Practice: A Review of the Literature. Nurse Education Today 35: 806–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, Liz, Michael Calnan, Ailsa Cameron, Jane Seymour, and Randall Smith. 2020. Identity in the Fourth Age: Perseverance, Adaptation and Maintaining Dignity. Ageing & Society 34: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinlay, Elizabeth B. 2001. The Spiritual Dimension of Ageing. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinlay, Elizabeth B. 2006. Spiritual Care Recognizing Spiritual Needs of Older Adults. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging 18: 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinlay, Elizabeth B., and Richard Burns. 2017. Spirituality Promotes Better Health Outcomes and Lowers Anxiety about Aging: The Importance of Spiritual Dimensions for Baby Boomers as They Enter Older Adulthood. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging 29: 248–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinlay, Elizabeth B., and Corinne Trevitt. 2007. Spiritual Care and Ageing in a Secular Society. The Medical Journal of Australia 186: 74–76. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17516891 (accessed on 13 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Malone, Joanna, and Anna Dadswell. 2018. The Role of Religion, Spirituality and/or Belief in Positive Ageing for Older Adults. Geriatrics 3: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man-Ging, Carlos Ignacio, Jülyet Öven Uslucan, Martin Fegg, Eckhard Frick, and Arndt Büssing. 2015. Reporting Spiritual Needs of Older Adults Living in Bavarian Residential and Nursing Homes. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 18: 809–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Lydia K. 2012. Spirituality as a Lived Experience: Exploring the Essence of Spirituality for Women in Late Life. International Journal of Aging & Human Development 75: 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, Ana Cláudia, Érika De Cássia Lopes Chaves, and Guilherme Antônio Moreira De Barros. 2017. Spiritual Needs of Patients with Cancer in Palliative Care: An Integrative Review. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care 11: 334–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, David O. 2005. Research in Spirituality, Religion, and Aging. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 45: 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, David O. 2008. Spirituality and Aging: Research and Implications. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging 20: 95–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas G. Altman. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. British Medical Journal 339: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, Stéfanie M., Etienne Rochat, Christophe J. Büla, Guy Jobin, Estelle Martin, and Brenda Spencer. 2010a. The Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool: An Instrument to Assess Spiritual Distress in Hospitalised Elderly Persons. BMC Geriatrics 10: 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, Stéfanie M., Etienne Rochat, Christophe Büla, and Brenda Spencer. 2010b. The Spiritual Needs Model: Spirituality Assessment in the Geriatric Hospital Setting. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging 22: 271–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, Stéfanie M., Mark Brennan, Etienne Rochat, Estelle Martin, Stéphane Rochat, and Christophe J. Büla. 2011. Instruments Measuring Spirituality in Clinical Research: A Systematic Review. Journal of General Internal Medicine 26: 1345–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monod, Stéfanie M., Estelle Martin, Brenda Spencer, Etienne Rochat, and Christophe Bula. 2012. Validation of the Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool in Older Hospitalized Patients. BMC Geriatrics 12: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowat, Harriet. 2004. Succesful Ageing and the Spiritual Journey. In Ageing, Spirituality, and Well-Being. Edited by Albert Jewell. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mundle, Robert. 2015. A Narrative Analysis of Spiritual Distress in Geriatric Physical Rehabilitation. Journal of Health Psychology 20: 273–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Scott A., Marilyn Kendall, Kirsty Boyd, Allison Worth, and T. Fred Benton. 2004. Exploring the Spiritual Needs of People Dying of Lung Cancer or Heart Failure: A Prospective Qualitative Interview Study of Patients and Their Carers. Palliative Medicine 18: 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musick, Marc A., John W. Traphagan, Harold G. Koenig, and David B. Larson. 2000. Spirituality in Physical Health and Aging. Journal of Adult Development 7: 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]