After the collapse of the ideology of state atheism, the advent of religious liberties in Russia provided the Orthodox Church with a wide range of opportunities to assert and manifest itself in the humanitarian field. However, during the demilitarization in perestroika and post-perestroika years, society has not expected the Church to do with war, earthly battles, and military service, to discuss the consecration of nuclear weapons or to build monuments to the army’s glorious weapons. However, the recent Church’s activities greatly belied these expectations in quite a systemic way.

Well-known religious scholar Karen Armstrong uses the term “military piety” to denote the aggressive religiousness of fundamentalist movements in the second half of the 20th century and their hostile rejection of modernity. She writes that “the emergence within every major religious tradition of a militant piety popularly known as ‘fundamentalism’ has been one of the most startling developments of the late 20th century” (

Armstrong 2001, p. 7). However, such a view suggests that militant piety is a modern anomaly and belongs only to fundamentalism, while “regular” religions are inherently peaceful and constructive (see also

Armstrong 2014). We want to dispute this claim and suggest that positive attitudes towards war and militancy, practices and artifacts related to them exist beyond radical movements, in the core of established and refined religious tradition. Besides, our precedent of militant piety embraces modernity instead of rejecting it, which is evident in the cases of blessing firearms, missiles, and military vehicles, as well as in promoting nuclear weapons. Some other researchers, who apply this term, do not attribute it exclusively to the 20th century, but detect ideological and practical links between religion and war in Judaism, Christianity, Islam and other religions throughout history (see

McLeod 1984, pp. 3–11;

Esposito 2002, p. 41;

Sizgorich 2009). Concerning the Russian Orthodox conservatives, this point is confirmed by Stella Rock, who notes their overall militancy (

Rock 2002). Thus, we consider legitimate to apply this term (1) to the present and (2) to all the communities within the religious tradition, not only its “radical” segment.

By the term “militancy,” we mean two interrelated phenomena. First of all, that is a dualistic worldview that depicts the world as a field of the battle between good and evil, which is inherent to religious imagination; Mark Juergensmeyer calls it “cosmic war” (

Juergensmeyer 1992,

2017). According to R. Scott Appleby, this attitude is present to all religions, but its agents decide, whether they want to fight the “dark forces” with violent or non-violent means (

Appleby 2000, pp. 29–30). Second, this general militancy can manifest in positive attitudes towards real war and soldiering, and in elaborating specific theological arguments in their support. In a moment and depending on particular social, political, and economic context, a religious community can enhance its militancy by elaborating on the resources of its tradition or highlighting other aspects of spiritual being.

We refer to militancy in post-Soviet Russian Orthodoxy (and, partly, American Orthodoxy) as a general trend of developing both types of militancy. It seems to embrace discourse and practices of both “low” and “high” ranks of the Church, i.e., radical actors, who criticize the official hierarchy, and this hierarchy itself. Although that is the second one who works with the state and put military priests in the army, create portable temples and bless firearms, the first ones are often more explicit in theological arguments. Thus, to describe this trend we will use all the disposable evidence: Official documents published on the website of the Moscow Patriarchate, publications in the internet, books, and articles by the Orthodox actors, interviews, and commentaries in the media, reports about the modes of participation of the Russian Orthodox Church in the army, etc. Such a patchy set of sources is necessary to create, however partial, but a broad picture of the reality we describe: Little-known conservative authors are as crucial for us as official documents, though their impact is less evident.

This article aims to scrutinize this phenomenon, to assess its scope and to answer the question to what extent it is having place coincidentally and conditioned by the socio-political situation, and to what extent it roots in the Orthodox Christian tradition. We want to put forward two theses: First, the perception of the world as the arena of a global battle appears to become an integral component of the Church’s worldview, discourse, and practice, and as such, it is leading to promoting tight connections with the Russian military forces. Second, this “militant piety,” this mobilization mindset seems to be not merely situational. These qualities are inherent in Orthodoxy as a whole, yet given particular local Orthodox traditions, and they actualize differently.

Next, the argument will proceed as follows. We will begin with discursive rehabilitation of war, which we find in many Russian Orthodox authors. The second paragraph observes the formal process of collaboration with the state in terms of introducing the military priests’ institution, creating a special uniform for them, designing field temples, and building a cathedral of Russian Armed Forces. The third section compares the Russian case with American material, which demonstrates a similar intellectual trend. Finally, we will try to make a historical point and to show that these phenomena are not modern, since they were presented in the Christianity from its very births and elaborated in the Russian Orthodoxy of the Synodal period (1700–1917).

1. Rehabilitation of War in Post-Soviet Orthodoxy

Attempts to justify and reconsider the way the Orthodox believers perceive war are reflected in official documents and public declarations adopted with the Russian Orthodox Church participating. Back in 1995, the World Russian People’s Council, chaired by the current patriarch, then Metropolitan Kirill (Gundyaev), adopted a document with the eloquent title

O svyatosti ratnogo sluzheniya [On the Sanctity of Military Service], which not only justifies military service for Orthodox believers but also sacralizes it. The text holds that “[t]he Russian Church is characterized by a special type of sanctity—the holy righteous princes, defenders of the Motherland and the Church” (

O svyatosti 1995). Thus, the document indicates that the Russian Church tradition has developed a special kind of piety towards military service that is absent in other Orthodox traditions. Some Orthodox authors advocate the idea of differentiating a particular category of saints: Military priests who became martyrs in the 20th century. Quite characteristically, an Orthodox author Andrey Kostryukov stresses the fact that many military priests were executed after the 1917 revolution along with ordinary priests and ranked as new martyrs, which raises them to the level of special heavenly intercessors: “A host of these pastors intercede now to God for the army, for the clergy, for our people” (

Kostryukov 2011). In other words, the military forces are seen, in this sense, as a particular unit of saints in heaven.

The

War and Peace section in the

Basis of the Social Concept of the Russian Orthodox Church is even more crucial for understanding the Church’s attitude towards war. The document offers criteria of distinguishing between an aggressive war, which is unacceptable, and a justified war, attributing the highest moral and sacred value of military acts of bravery to a true believer who participates in a “justified” war (

The Basis 2000, VIII). The text reproduces the argument used in the Byzantine Empire by those who claimed the Church could justify military actions (

Stoyanov 2009, pp. 166–219). In particular, the militaristic interpretation provides a reference to a quotation from the Gospel of John: “Greater love hath no man but this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13). This quotation is used in the

Basis of the Social Concept to consider a military act of bravery connected with a possible death not only as a justified action but also as the highest Christian virtue. The

Basis also quotes from classical patristic apologies of war from the Church’s perspective, for instance, passages of St. Cyril-Constantine the Philosopher and St. Metropolitan of Moscow Filaret (Drozdov) on the importance of participation in the military defense of the Motherland. Additionally, the document considers the just war criteria as developed in Western Christianity eligible for Russian Orthodoxy, so the “justified war” idea in Western theology is applicable to the Russian Orthodox Church too. At the same time, in the post-Soviet period, some well-known priests and missionary theologians began to persuade the flock to disassociate themselves from the disrespectful, critical and sometimes even derogatory attitude towards the army which was then widespread in Russian society and which was actively supported by the media in the late 1980s and 1990s (

Kormina 2005, p. 5).

Many reputable priests-confessors and renowned Church public figures seek to counter the opinion that Christianity disapproves of military service: Among less well-known pastors, these are Alexander Ilyashenko, Dimitriy Smirnov

1, Maxim Kozlov

2, Alexander Grigoriev (

Grigoriev 2008), and deacon Andrey Kuraev

3. The message of their sermons and statements came down to convincing society that military service is God-willed, protecting it from mass media attacks, “increasing the prestige of this service, aspiring the revival of glorious military traditions and prosperity our Homeland.” (

Iliyashenko 2008) After some 25 years of religious liberties, the apology of soldiering and different forms of war became even more systematic. Some brochures on the topic appeared, such as priest Georgiy Maksimov’s

The Orthodox Attitude to War and Military Service (

Maksimov 2015), and M. Frolov and V. Vasilik’s

Battles and Victories. The Great Patriotic War (

Frolov and Vasilik 2015). Although the general views of these authors are different, they elaborate on the subject similarly.

Alexey Osipov, an Orthodox missionary, professor at the Moscow Theological Academy, and a member of the Moscow Patriarchate team who authored the

Basis of the Social Concept laments the demilitarization in today’s Russia. He attributes it to the action of non-Christian forces and ideological influence of the enemies of patriotism and “sacrifice for the nation’s sake,” which are the fundamental values. He equates such concepts as “patriotism,” “base of the traditional religion,” and “love to the Motherland and the Church” with the “idea of a just, holy war,” “the idea of sacrifice for the sake of the nation.” At the same time, according to Osipov, demilitarization is caused by the desire of world elites to build a single global state that will surpass in injustice all the previous ones: “The destruction of the idea of a just and holy war paves the way for the creation of a single faith, a single religion, a single culture, a single global state with a faceless mass of slaves and ‘godlike’ lords with unlimited power” (

Osipov 1998).

The Orthodox believers who sympathize with the military sometimes propound the idea that it was the most receptive audience for the teaching of Jesus Christ brought to earth (

Iliyashenko 2008). In this regard they often refer to the moral guidance given to soldiers by John the Baptist (Luke 3:14) that did not contain any rejection of the military profession as such; instead, it is interpreted as evidence that military service is legitimized from the perspective of New Testament ethics and that the soldiers, along with the shepherds and the magi, were a kind of leading category in the dissemination of the Gospel.

Methods of fighting (

The Basis 2000, VIII: 3), as well as the soldiers’ spiritual condition, serve as criteria developed to distinguish a “righteous” and “justified” (“just” in the Orthodox sense) war from an “unjust” one. According to Osipov, the right spirit involves the ability to “carry on a war with righteous anger, not with a thirst for revenge,” so that necessary killings are not “an expression of the extreme degree of personal hostility and bitterness” (

Osipov 2012). Osipov suggests that this condition can be quite possible, since “when killing each other in a war people frequently do not know each other and lack personal hostility towards each other,” which means they can kill for restoring truth and justice rather than for personal benefit, being guided by “righteous anger.” As he says in an earlier piece, wars carried on with such feelings are not evil (

Osipov 1998). He believes that “the righteous anger may be called the ‘anger of love,’ similar to the sense of justified anger experienced by parents punishing the child” (

Osipov 2012).

Another exciting topic is remarkable inversion occurred in the Russian Orthodox Church’s attitude toward nuclear weapons. At the beginning of the post-Soviet period, the Church milieu regarded it generally negative, as indicated, in particular, by the negative assessment of the fact that the Soviet authorities turned Sarov, the city of famous Russian St. Seraphim, to a nuclear center. Some pastors even considered such transformation a result of “diabolical action” (

Kuraev 2017). After a decade, this assessment not only changed to the opposite: St. Seraphim of Sarov himself became a symbol and a protector of Russia’s “nuclear shield.” Such an interpretation appeared even at the liturgical level, so the exclamation from the acathist to the saint, written in 1904, “Rejoice, shield and protection of our Fatherland,” started to be considered in a nuclear defense meaning. The very essence of the name “Seraphim” (which means “blazing” in Hebrew) became associated with extreme heat and radiance of atomic energy (

Kholmogorov 2008; see also

Adamsky 2019, pp. 76–78).

As Zoe Knox and Anastasia Mitrofanova point out, “the establishment of a connection between Orthodoxy and nuclear weapons is not surprising. Together they are understood… as guarantees of Russia’s two-fold independence: Spiritual and geopolitical” (

Knox and Mitrofanova 2014, p. 49). Thus, the scholars suggest this connection to be entirely dependent on the political context and new state ideological trends of the 2000s. On the contrary, Dmitry Adamsky writes that this phenomenon has more profound and intimate premises inside the Church tradition: According to him, religion is an essential factor of the theocratization of the Russian strategic community and the nuclear complex, in particular (

Adamsky 2019). Reassessment of nuclear weapons started long before the 2000s. Some Orthodox priests, theologians, and even members of the Church hierarchy began to justify it as a deterrent means able to facilitate justice on earth and uphold Orthodoxy by ensuring the protection of Holy Russia as a stronghold of faith. The consecration of Strategic Missile Forces complexes and sometimes even nuclear vehicles by priests underlines this approval of atomic arms. We have to note that this practice contradicted the Church’s opinion expressed in the 1986 Epistle of the Holy Synod titled

On War and Peace in the Nuclear Age, which stated that a nuclear war goes beyond what was hypothetically acceptable. It also recognizes that “the concept of justice cannot be applied” to a nuclear war; in other words, such a war exceeds the scope of legitimate “just wars” (

Poslanie 1986).

The Russian-Ukrainian conflict showed that the extrapolation of the idea of spiritual battle and vivid discussions on the spiritual meaning of military actions can reflect in real-life politics when individual volunteers and private military companies who went to fight in the Donbas began to consider their activities as “a war for Holy Russia” and even called themselves a “Russian Orthodox Army” (

Knorre 2016, pp. 26–32). Besides, that is far from being a coincidence that the constitution of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic proclaimed Orthodoxy its “state religion.” This point is of particular interest, because in the first edition of the document dated May 14, 2014, articles 9.2-3 assert that “In the Donetsk People’s Republic, primary and dominant is the Orthodox faith (the Christian Orthodox Catholic Faith of Eastern Confession), professed by the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate.) The historical experience and the role of Orthodoxy and the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) are recognized and respected as the fundamental pillars of the Russian World.” (

Soldatov 2014;

Solodovnik 2014). In 2014, dozens of Russian media reported on these lines, but in the text of the Constitution published on the DPR’s website, they are now absent, which can be explained by the suggestion that it was retroactively edited (see

DPR Constitution 2018).

Thus, from the late 1990s, we see various phenomena that show the convergence of the Church and the army and that support the arguments in favor of justifying the participation of (post-Soviet) Orthodox believers in military service. The practice of consecrating weapons has become so widespread and customary that in 2017, the Church considered it necessary to legitimize this practice theologically and canonically, and by mid-2019, the Inter-Council Presence drafted a document titled On the Practice of Consecrating Weapons in the Russian Orthodox Church. This document, however, condemned the consecration of weapons of massive destruction, including nuclear weapons.

The apology of military affairs by the leading Church pastors and missionaries was not occasional: On the contrary, it was rather ordinary. We can say that the Church in post-Soviet Russia acts as an institution that helps to overcome the consequences of the devaluation of military service that occurred in the late Soviet-early post-Soviet period (

Eichler 2012). Its leaders and priests sometimes talk publicly about an exclusive partnership between the Church and the army when it comes to the protection of the state. They claim that the Church, along with the Armed Forces, is the main backbone of Russia, which will never betray it. Adding to the phrase of Emperor Alexander III that “Russia has just two allies, the armed forces, and the navy”, the priest Alexander Ilyashenko suggests Russia has the third ally along with these two—that is the Church (

Iliyashenko 2008), which somehow equates it to the military forces.

2. From “Theology and War” to “Military Orthodoxy”: Structural and Institutional Convergence and the Liturgical Reception of War

Until now, we have approached the “militarization” of Orthodoxy from the perspective of its approval in state-aligned discourse and theology. This format implies a mechanical connection between Orthodoxy and the military sphere; hence, it may well be broken if its agents should change their views or rhetoric. However, in 2000s–2010s some institutes, artifacts, and places emerged that suggest a real “interbreeding” of these two components and the introduction of hybrid phenomena: These include restoring of military clergy institute, the development of uniform for them that combines military and religious symbols, creating field temples, and building a magnificent cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces. In other words, the theological rethinking of military service in favor of its sacralization in Orthodoxy led to the emergence of hybrid forms of church-military interactions on structural, institutional, or aesthetic levels, as well as, as we will show, on the liturgical level. We can observe this process on publications in media, which were reflecting the public discussions on the subject and depicting the new inventions throughout this period.

In 2006, the Main Military Prosecutor’s Office brought to the State Duma a law on the introduction (in a sense, restoration) of the “military priests” institution, finally signed in 2009. Such priests existed in the Russian Empire before 1917 and were treated in the army like officers, though they did not possess military ranks. On the other hand, mullahs, rabbis, and the clergy of other religions also belonged to the chaplains back then (

Pchelintsev 2012, pp. 16–23). Nowadays, the term refers mostly to Orthodox priests, although by 2011 in the army, there was a mullah (

Smirnov 2011). At the same time, Russian Muslim and Buddhist communities and even the Old Believers discussed the introduction of their clergy in the army (

Moshkin 2007), but now these discussions stopped.

According to

The Regulations on the Military Clergy of the ROC in the Russian Federation, the document of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church, the main goals of military priests are to conduct various sacred services, take part in spiritual nourishment of Orthodox military personnel and to maintain the morality of the troops (

Polozhenie 2013). However, the discussions concerning the project also show its “added value” for consecrating the activities of the Armed Forces as a whole. The Chairman of the Synodal Department for Interaction with the Armed Forces, Bishop of Klin (then archpriest) Sergiy Privalov noted in an interview that a military priest “is ready to be with those defending the Motherland, our authentic traditions, our spiritual life. In such a case, not only the clergyman is falling in line with the defenders, but he is also bringing spiritual meaning to this defense” (

Privalov 2016). Despite his saying that “our main weapon is prayer,” the transition between the symbolic weapon and the real one is clear, as well as the transition between the two forms of enemies—the supernatural and the earthly ones. Mark Juergensmeyer suggests that this particular transition is crucial for the relationship between religion and violence (

Juergensmeyer 2017, p. 162). Generally, we can regard these developments as restoration of pre-revolutionary Russian tradition, where chaplains were an essential part of military culture. Some insights on the topic are found in memoirs of Georgy Shavelsky, the last Protopresbyter of the Russian Army and Navy, who even uses the term

dukhovno-voennoe delanie [spiritual-military activity] concerning his immediate sphere of responsibility (

Shavelsky 2019). However, if Shavelsky’s attitude towards the war was tragic—it “tries human souls,” but remains “merciless and destructive, meaninglessly and fruitlessly devouring everything men have built”—today’s Russian Orthodox Church tends to romanticize it.

It is noteworthy that the Armed Forces often include priests in the military personnel and give them a salary, accounting it from the military budget. Some actions are meant to bring them closer to the army’s life—for instance, through training, so they are taught weapon skills and parachute jumping. Along with these, there are other forms of church-military interaction, such as patriotic Orthodox clubs with military bias, the number of which is about 70 (

Krotov 2014).

Regarding the issue of hybrid church and military symbols, the issue of a special uniform for military priests arose: Whether they should wear vestments, battle dress uniform or civilian clothes. In this respect, an ordinary priest’s cassock would (and for a long time did) mean that priests are “outside” persons, “guests” to the Armed Forces. On the other hand, since the priests did not have a military rank, they could not wear a battle dress uniform, while civilian clothes would not demonstrate their special status. The issue was finally tackled in 2016 when a special uniform for the chaplains was designed (

Figure 1). It was a camouflage priest’s cassock, combining the features of vestments and military uniforms. The head of the Department for work with believers of the headquarters of the Central Military District Igor Agafonov commented: “This is a regular uniform of a soldier, the only things that differ are stripes and emblems: There is an Orthodox cross instead of the tabs with the military branch, and there is an additional church rank to the name of a soldier” (

Central 2016). Moreover, the priests are required to wear a cross over their uniforms. Thus, military priests turned from a “supplement” to the army into a separate “military branch,” which wages a spiritual struggle and supports soldiers in real wars.

In 2013, there were tests of a portable temple based on the KamAZ truck. It was designed to guide the paratroopers during military field exercises and armed conflicts and took into account the option of airdropping.

We can observe the Church-army convergence in the representation of military symbolics inside the temple and the emergence of new hybrid forms of sacred military ceremonies. A vivid example is the ceremonial reception of the Patriarch in Plyos in 2015 with the specific guard of honor, where the priests are standing to the Patriarch’s right and military officers are lining up in front of them, thereby forming two symmetrical phalanges (

Figure 2). One can assume that such a way of hosting the Patriarch iconographically symbolizes the heavenly host serving the Almighty: Since monkhood in Orthodox theology is an “angelic rank,” the military on a par with the monks altogether represent the heavenly host in its entirety.

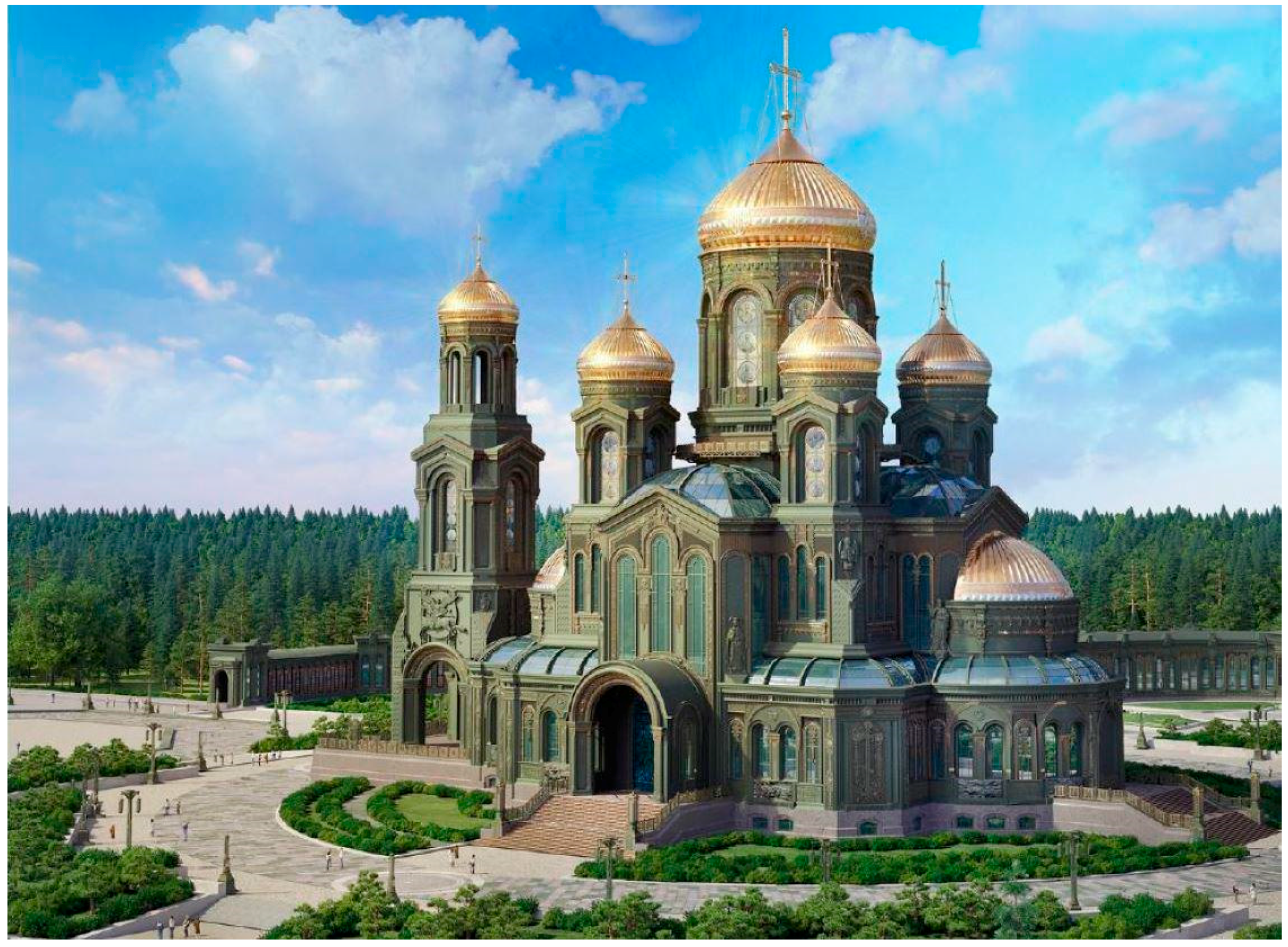

However, the ultimate embodiment of “military Orthodoxy” is the ongoing project of an “official” temple of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, which is to be built by 2020 in the “Patriot” military-patriotic park in the Moscow region.

Another title of the project is “Temple of Victory” (

Figure 3): Its main chapel is consecrated in honor of the Resurrection of Christ interpreted as a victory over the “dark forces” and is symbolically projected onto the army, the Church and the entire nation that devote themselves to daily heroic feats. The temple also symbolizes the Russian statehood as a whole and “consecrates” its military activity at all times, disallowing the very question of whether it was righteous or not. As Bishop Klinsky Stefan notes, “this temple is a symbol of our Victory. Not only the Victory in the Great Patriotic War, but also in all the wars and battles Russia conducted over the entire time of its statehood” (

Privalov 2019). As Anna Briskina rightly writes, “victory” and “power” (which means the state’s power on the international scene) became the key categories in the new Russian search for identity. “‘Victory’ and all notions related to it—such as enemy, betrayal, battle, revenge, power—flowed into the old and now reborn system of ideas based on the concept of the Russian messianity” (

Briskina-Müller 2015).

It is essential that this consecration also applies to the Crimea events of 2014: The temple reproduces the shape of the Sevastopol cathedral. During the accompanying discussions, there were constant appeals to confront those who “distort great Russian history.” Even its location, the “Patriot” park, appeared in 2014, the same year as the Crimea events, on the wave of militaristic inspiration and the triumph of Russian power that overtook a significant part of the nation.

Apart from the central chapel in honor of the Resurrection of Christ, four other altar corners of the temple will be devoted to four saints—the patrons of various branches of the armed forces: Alexander Nevsky (army field forces), the Prophet Elijah (air forces), Andrew the First-called (fleet) and Varvara the Great Martyr (missile forces, since her memorial day, November 19, coincides with the day of the rocket man). Its dome is said to resemble the helmet of Alexander Nevsky so that the body of the temple will mirror the image in the icon of the faithful saint prince (

Novaya 2019). The interior of the temple will represent the scenes of the battles in which the Russian army fought. In the end, the Temple of Victory combines all the elements of “military Orthodoxy” we discussed so far: The cult of the Great Victory, the symbolic projections of “spiritual warfare” on real armed conflicts, the close Church-army cooperation, and the veneration of the militant saints.

Such a development of hybrid forms of military-church symbolics bears a direct relation to the most sacred and innermost of the Church—the holy worship, which makes it possible to recognize not only the Church-army convergence but also the “liturgical reception,” even “liturgization” of war in modern Russian Orthodoxy. However, comparing these phenomena with some artifacts from the Russian Empire before 1917, we quickly find analogs of today’s Church-military hybrid forms. In her book on the Russo-Japanese War, discussing the Church’s imperial traditions and cooperation with military forces in the 19th-early 20th century, Betsy Perabo mentions some forms of this “interbreeding” close to what we observe today. She speaks about how Russian Orthodox leaders drew on a centuries-old Russian Orthodox tradition “that held up the soldier-martyrs of the ancient world, canonized princes who went to war, and honored warriors in religious services—even, in one case, dedicating an entire liturgy to a military victory” (

Perabo 2019).

Although there is nothing new in the very fact of the liturgical reception of military symbolics in Russian Orthodoxy, today it proceeds in a specific manner. When prayers and chants mention military force or victory, or a sainthood-list feature a soldier-martyr, military does not serve here as a core of religious conscience, but acts as something external that needs the Church’s blessing: The Church tradition embraces and sacralizes the given material, be it memorial war events, national armed forces, prominent warriors or specific weapons. However, in the case of the Temple of Victory (called the main Cathedral of Armed Forces), we see something new: Here, the militaristic element is not as something “external” that needs the Church’s blessing, but an autonomous object that sacralizes the world and human existence just like the Church does. Instead of being a passive object of sacralization, the militaristic element becomes an active agent.

Hence, we could differentiate two types of how militancy embodies in the Church’s culture: That is (1) passive sacralization that produces nothing new and (2) active incorporation and hybridization, the products of which begin to operate as self-standing agents. Although Betsy Perabo does not differentiate these two types and pays more attention to the phenomena of the first type, she gives some examples of the second type in the chapter dedicated to the concept of “Christ-loving military” in the Russian Orthodox tradition (

Perabo 2019). For instance, she refers to the dialogue between diplomat Evfimiy Putyatin and his father, who served in the fleet and thus interpreted a warship as a monastery—an argument to convince his son to choose a fleet carrier as analogous to monkhood. In this regard, the scholar notes that the centuries-old Russian Orthodox tradition treats soldiering “as a Christian calling—perhaps the most Christian of callings—at all levels, from soldier to commander to tsar” (

Perabo 2019), the description that most probably fits the views of many today’s Russian Orthodox.

3. Is It Only a Russian Case? Debates on War in American Orthodoxy

One may object that the militarization of Orthodoxy in post-Soviet Russia is something exceptional that goes too far beyond or even contradicts this religion’s “essence.” This development is undoubtedly specific, but it is not unique even in the broader context of world Orthodoxy since the attempts to justify war and legitimize the military sphere are apparent in American Orthodoxy too.

In the American and Western European contexts, 9/11 and the ensuing US invasion in Iraq triggered some discussions on the justification of war. On the one hand, the offense in Iraq in March 2003 led to a widespread protest among American Orthodox Churches: In particular, the Orthodox Peace Fellowship in North America (OPF) wrote a letter to President George W. Bush signed by some 150 Orthodox theologians and religious leaders, including bishops and priests from various Orthodox Churches. Among other things, the letter states that “the Orthodox Church has never considered any war to be just or good” (

OPF’s Appeal 2004). On the other hand, these events formed the basis of an entirely opposite opinion, expressed by a number of Orthodox leaders headed by Alexander Webster, archpriest of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR), who previously served in American Armed Forces as chaplain, and later, as a dean of the Holy Trinity Orthodox Seminary in Jordanville. In his deliberations on 9/11 and the Iraqi invasion, he tried to bring new consistent arguments in favor of justifying war. In the article “War as a Lesser Good,” published in the special issue of

St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly (2003, vol. 47, no. 1), Webster suggested changing the perception of war from a “lesser evil” to a “lesser good.” Along with his article, the special issue contains other items dedicated to the justification of war in Orthodoxy and critical receptions of Alexander Webster’s ideas. Therefore, the journal actualized a broader public debate on the position of the Orthodox churches towards war and military service.

Responding to criticism, a year after this special issue, Webster and Darell Cole wrote the book “The Virtue of War: Reclaiming the Classic Christian Traditions. East and West” (

Webster and Cole 2004), in which they elaborate on their arguments on the justification of war. They assume that by speaking about war as a “lesser good” not only do they not bring anything new to Orthodox tradition, but also restore the classical Christian traditions of East and West. They aim to define the conditions of a “justified war” from the standpoint of the 21st century Orthodoxy. In their book, they put forward the idea that the “just war” theory formulated in Western Christianity applies to Eastern Christianity on many points, and some conditions of a “just war” may find their equivalent in Orthodox Christianity. In order to justify the war in particular cases, the authors analyze the Byzantine tradition and try to show that even if there are some grounds missing for a “just war” theory, the missing provisions may be formulated today for Orthodoxy by consistently drawing the legitimate theological conclusions from works of the Church Fathers, liturgical and pictorial Byzantine traditions in respect to war.

The arguments of Webster and Cole are very similar to those used by the Russian ideologists of “military Orthodoxy” and stated in the

Basis of The Social Concept. Interpreting Jesus Christ’s words on the “greater love” (John 15:13) as a reference to self-sacrifice at war and John the Baptist’s address to the soldiers (Luke 3:14), they praise the highest meaning of the military feat. Similar to protodeacon Vladimir Vasilik, the American authors quote from Byzantine hymnography and suggest that a militant attitude to the worldly existence inheres Church tradition. One might think that the Orthodox “war party” in Russia would use Webster’s works to support its position, but there is an obstacle: Webster stands for the apology of war from a pro-American perspective and regards the United States as the guarantor of peace on Earth—a Katechon, even the Third Rome potentially if its people appreciate the importance of ancient Orthodox tradition, to which part of the local religious community belongs (

Webster and Cole 2004). Needless to say, Russian apologists for “military Orthodoxy” reserve the role of Katechon for Russia, and not for its Transatlantic foe. Nevertheless, at the theological level, the arguments in favor of justifying war put forward by Orthodox militarists in Russia and the United States are strikingly similar.

Alexander Webster was by no means the only theologian who supported the Iraq campaign and put forward the arguments to justify military actions. Two weeks after the Iraqi campaign began, Frank Schaeffer, a member of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, published a critical article in

The Washington Post, accusing the OPF of “simplifying and distorting the teaching of [its] Church in its Iraq Appeal,” and also in “dragging not only the Church but Jesus into their stand against the US government and the war in Iraq” (cited in

Walsh 2016, pp. 51–52). Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon, a priest of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese, supported Schaeffer and suggested in

Touchstone magazine (November 2003) a difference between the Eastern and Western Christian approaches towards the moral assessment of the war. David Bently Hart, who supported the American invasion in Iraq, reproduced Webster’s opinion, suggesting that the Orthodox should reconsider the view that Eastern Christianity is less belligerent than Western Christianity (

Hart 2004). Another supporter of the American priest was a group of writers who converted to Orthodoxy shortly before 9/11 and shared conservative political and social positions. After the Twin Towers fell, they started expressing grave concerns about how to more convincingly justify the American right to self-defense and belligerent US international policy (for details, see ibid., pp. 51–55).

However, the attempts to establish a new perception of war as a “lesser good” or even somehow reconsider the attitude of the Orthodox Church in favor of the acceptability and justification of war caused strong objections in American society and a massive backlash from the Orthodox who oppose the religious arguments in favor of violence. It reflected in the collection of documents, conventions, and public statements titled

For the Peace from Above: An Orthodox Resource Book on War, Peace, and Nationalism, compiled by priest Hildo Bos and OPF leader Jim Forest (

Bos and Forest 2011). A collection of articles, in which leading Orthodox theologians and scholars expressed their views on the Orthodox attitude to war appeared in 2016 under the title

Orthodox Christian Perspectives on War. (

Hamalis and Karras 2016). Some authors explicitly argued against Alexander Webster’s points (see

Papanikolaou 2016;

Walsh 2016;

Bouteneff 2016). For the most part, the editors of this collection offer grounds for the view that war is an unacceptable evil and make a stand against any attempts to justify it.

To sum up, similar attempts to propose theological arguments in the “defense” of war and to convince the Orthodox public to get involved appeared not only in Russia but in the United States. However, this kind of view has not turned mainstream, being vigorously criticized by a large number of theologians and clergymen. The reason for this difference in reception was, as we would assume, the lack of Church-state cooperation and infrastructure related to it. In America, Orthodox militancy stays on the level of ideas and is not reflected in practices, such as consecrating firearms, artifacts (e.g., uniforms for military priests or field temples), and monuments to the glorious state power. The US invasion in Iraq of 2003 did not provoke such mass excitement as Crimea events of 2014 did, and the public request for religious justification of war and military service was much lesser.

4. War as a Worldview: Spiritual and Socio-Political Dimensions of Militant Piety

The very fact that particular “theologies of war” appeared in 21st century Orthodoxy in such different contexts as Russian and American makes it necessary to pose the question of their roots and embeddedness in the tradition itself. Are these phenomena random, separate, coincidental anomalies that appeared only due to the belligerence of some priests and their temporal political environments? Or, maybe, there is something in the Orthodox Christianity that favor such developments and, so to say, “wait to appear” in particular circumstances?

Taking an unbiased look into the history of the Byzantine Eastern Church’s interaction with what is now called

siloviki (security forces), we have to admit that its modern forms are all but new. That is, the status of militarism that we observe in post-Soviet Orthodoxy is deeply rooted in the historical tradition of the relationship between the church and the army in the Byzantine Empire, which is the standard reference of both Russian and American belligerent Orthodox thinkers, such as Frolov, Vasilik, or Webster. When it comes to describing the Church-world relationship, the Christian discourse and rhetoric feature particular “military connotation.” The Church’s worldview bases on the idea of an ongoing spiritual struggle between the forces of good and evil, as well as on the fact that the earthly Church has to “fight” passions, sin, and other works of the devil. In general, every Christian appears to be a warrior of Christ. Beginning with Pope Clement V (14th century), who called the “Church militant” all living Christians in his letter to King Philip IV in 1311 (

Ecclesia 2010), prominent theologians started to apply the characteristic “militant” to the earthly part of the Church (

“Ttserkov zemnaya” [the Church on earth]), in addition to the more ancient characteristic “

stranstvuushchaya” [wandering, Latin

peregrina]

4. More specifically, in Russian Orthodoxy, the term

“Tserkov’ voinstvuyushaya” [the Church militant] was first used by St. Dimitry of Rostov (

Tvoreniya 1910, p. 991). Later, this notion became commonplace in Russian works on Orthodox theology. It is used to refer to the “Church militant” in the Orthodox dogmatic theology of Makarius Bulgakov, the most authoritative handbook on dogmatics at the end of the Synodal period (

Bulgakov 1999), as well as in Michael Pomazansky’s dogmatic theology (

Pomazansky 2015), in the catechism written by Metropolitan Anthony Khrapovitsky’s (

Khrapovitsky 2010), and in the unique appendix to the catechism by St. Filaret Drozdov, titled

An Orthodox Warrior’s Catechism. For example, this latter text asserts that “God loves blissful peace, and He blesses righteous fight. While there are unpeaceful people in the world, we cannot sow peace without military force” (

Drozdov 1916). It features many examples from the Old Testament, so the author even concludes that for people of Israel, “the tabernacle was a battlefield temple, settled according to the testaments of God and Christ” (ibid.)—the point that strikingly resembles today’s field temples that we have discussed above.

Referring to the term, most theological handbooks on Orthodox dogmatics make a reservation that they mean warfare of spiritual, not physical nature, and the fight is waged primarily against the inner evil—the person’s sinful inclinations, and against the external enemies—the satanic forces inclining a person to fall away from Lord God. The dictum of St. Paul that “our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms” (Eph 6:12) is of direct relevance to this matter. However, despite these theoretical points, in the minds of Orthodox believers, the concepts of war in the sense of the “Church militant” and the notion of “warrior of Christ” often refer to both spiritual and earthly struggles, where the latter is the “projection” of the former on particular social and political realities of a time. Even

The Basis of the Social Concept notes that “generated by pride and resistance to the will of God, earthly wars reflect the heavenly battle” (

The Basis 2000), which indicates the connection between real wars and wars in the invisible spiritual world. This statement corresponds to Mark Juergensmeyer’s understanding that in religious consciousness, universal “cosmic war” is composed of both kinds and dimensions of war (

Juergensmeyer 2017; for more detailed application of this concept to Russian Orthodoxy, see

Zygmont 2014).

One can see the scholar’s understanding exemplified in the narratives of war and the concept of the “Church militant” in the speeches of the Church leaders. For the most part, they try to emphasize the spiritual attribution of the idea and say that the battle directs against the invisible “dark forces.” Nevertheless, sometimes, the Russian Orthodox Church uses this idea to legitimize actions against the so-called “enemies of the Church,” which are societal and pretty visible. For example, after the scandal following the Pussy Riot performance in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in February 2012, the Synodal Department for the Church’s Relations with Society issued a

Declaration of the Council of Orthodox Public Associations regarding the Sacrilegious actions in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, which referred to the “Church militant” as a semantic symbol to argue for the right of the Orthodox believers to protect shrines and punish offenders through state security, defense, and law enforcement agencies—that is, to qualify the actions of Pussy Riot as a crime which should “be punished with the full force of the law” (

Zayavlenie 2012). In the end, three members of Pussy Riot were imprisoned and sent to labor camps.

Sometimes the concept of the “Church militant” is used purely in a socio-political meaning. For example, when the Metropolitan Longin of Saratov asserts that “the loss of vast territories which once were blooming Christian states is a defeat of the ‘Church militant’” he thereby recognizes that the “Church militant” exists in a material socio-political dimension (

Besedy 2013). Ordinary priests sometimes talk about the membership of Orthodox Christians in the “Church militant” to justify the rightfulness and necessity of their involvement in socio-political conflicts. Deacon Vladimir Vasilik openly states that the “Church militant” is fighting not only against invisible enemies but also against the visible ones—for instance, against the enemies of the Orthodox empire, which, is according to him, reflected in 7th-century Byzantine hymnography regarding Persian and Arab wars (

Vasilik 2016). The same transfer of the concept’s meaning occurs when clergy apply it to the participation of Orthodox believers in the Great Patriotic War (

Ryygas 2015).

Similarly, the concept of “heavenly host” or “host of the King of Heaven” is transferred from the spiritual to the socio-political dimension. An eloquent testimony is the well-known icon

Blessed Be the Host of the King of Heaven (renamed as “The Church Militant”) since in the Church’s view it serves as an iconographic legitimation of the possibility of drawing a parallel between the Heavenly Host and a particular earthly army—the military unit of Ivan the Terrible marching to conquer Kazan. An Orthodox “expert” Roman Bagdasarov observes that “icon gained its popularity in the second half of the 1990s and later, in fact, earned a cult following among the Orthodox national patriots, who perceived it as the highest archetype of Russian Orthodoxy: People mobilized for war and organized by their monarch” (

Tserkov’ 2014). That is, again, an exteriorization of the spiritual to the social, the transfer of idea of the “spiritual war” to the outside world, where the hostile “invisible forces” are personalized by identifying them as real embodiments on earth.

Therefore, the military consciousness, the tendency to see the worldly life as a kind of war and struggle with both spiritual and earthly enemies, serves as a general attitude in post-Soviet Church culture. Besides, specific Orthodox militancy may base on a defensive stance peculiar to Church culture outlined in

Journals by archpriest Alexander Schmemann, who notes that the Church holds itself as a kind of a fortress which aims “to keep, to guard, to protect the Church not only from evil, but from the world as such, from the contemporary world” (

Schmemann 2000, p. 144;

Knorre 2018).

Of course, this defensiveness is not destined to transform into militancy or war apology; it depends mostly on the cultural level and political situation of a specific society. R. Scott Appleby draws attention to the fact that even the general belligerence of religious consciousness and the perception of the world as the arena of a global battle, does not necessarily lead to violence since believers can take part in this battle using spiritual practice or non-violent resistance (

Appleby 2000). He refers to this variability as “ambivalence of the sacred,” which he sees at work far beyond the frame of modernity. However, in our case, Russian (and, partly, American) Orthodoxy chose the way of direct militancy on both theological and liturgical levels, cooperation with the military forces, and aggressive patriotic stance instead of fighting passions and sins.

5. Conclusions

In the article, we tried to conceptualize some developments in post-Soviet Russian Orthodoxy as the emergence of the relatively new “militant piety,” which takes place in both theory and practice. On the one hand, Russian Orthodox Church officials and radical conservatives are equally eager to develop the theological arguments in defense of war and military service and even sacralize them, interpreting Gospel’s words about self-sacrifice as feats at the battlefield. On the other hand, these developments do not remain merely theoretical, being reflected in the Church-army cooperation: The introduction of the institute of military priests, designing their uniform and field temples, building the cathedral that combines all these inventions and adds the cult of military saints. As we saw, these phenomena are not entirely dependent on Russian socio-political or economic situation, since we can observe similar processes in American Orthodoxy as well. The case we outlined underscores the point of Mark Juergensmeyer that the religious imagination is very much inclined towards (1) imagining the world as an arena of a “cosmic war” between forces of good and evil, or sacred and profane and (2) projecting the spiritual dimension of this war on the earthly realities, as we see on the examples of Crimea events of 2014, Donbas militants, and Pussy Riot case.

Following this line of reasoning, we cannot consider the issue of “militant piety” in Orthodoxy as something alien to this particular tradition, to Christianity, monotheism, or religion in general. It was tapped into the culture from the very beginning—both as a problem and as a set of resources. Emphasizing that, given the “ambivalence” of the sacred, the Orthodox Church could abstain from violence and work towards peace or turn towards justification of war and militant piety, we tried to demonstrate that the latter of these two options gained more attraction than the former throughout the 20th and the 21st centuries, which reflected, particularly, on reclaiming and rethinking the concept of the “Church militant” discussed above. The other option—non-violence and spiritual deeds—is most certainly present in post-Soviet Russian Orthodoxy as well, but, unfortunately, it is often seen distorting the tradition and inventing an image of the “pink Christianity,” as contemporary authors put it, quoting the Slavophile philosopher Konstantin Leontiev (see

Maltsev 2010). The coexistence of these two options within the same tradition and their relationship are to be studied, but we hope that this article can contribute to describing and conceptualizing at least one of them.