Abstract

The southeast part of Shanxi Province in China is a region with the highest concentration of early timber structures in the country, among which a majority are located in rural and semi-rural religious spaces. Social changes regarding rural population, religious demography as well as the ‘heritagisation’ process of these places of worship have presented unprecedented challenges to their long-term survival. A national campaign, the Southern Project, which lasted from 2005–2015 has facilitated a series of restoration projects in this region, covering 105 national heritage sites with pre-Yuan Dynasty structures, yet their maintenance, management and sustainable functions remain uncertain despite their improved ‘physical’ health. It also raises the question of how these (former) places of worship can be integrated into contemporary society. By analysing the data collected through reviews of the relevant legislative and administrative system and policies, interviews with various stakeholder groups, as well as on-site observations in the case region, this paper aims to identify not only the observable challenges in the long-term sustainability of religious heritage sites, but also the underlying issues situated in China’s heritage management mechanisms and systems behind, in order to pave the way for further discussions of a sustainable way forward.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Context

The cultural heritage industry in China has experienced an unprecedented boom in the last three decades. As the country has become one with the second most World Heritage sites in the world, closely tailing Italy, it demonstrates not only its strong interest in getting international recognition in the field but also the increasing attention given to cultural heritage domestically (WHC 2018). The development of the cultural heritage industry is made possible not only through the resources brought by the economic development of the country since the ‘Opening Up’ (SACH 2008), but also partly due to the perceived ‘threat’ associated with the heritage sites lost (or potentially lost) to the process of the very same development. During the early stage of the economic reform in the 1980s, ‘use first’ was identified as the principle for heritage rather than its conservation (Yan 2018, pp. 37–38). This perceived ‘threat’ is one of the main characteristics of the ‘heritage’ concept in the context of post-Cultural-Revolution China (Lowenthal 1998, p. 24; Harrison 2013, p. 7). In response to this feeling, the first phrase of the overarching ‘16-character Strategic Policy’1, which dictates the priorities of legislative and administrative tasks of the governmental entities for cultural heritage, explicitly states that ‘rescuing’ is prioritised above all. The ‘16-character Policy’ is a crystallised form of the responses towards the various types of threats as well as a change of discourse regarding heritage. It has been added to the 2002 version of the Cultural Relics2 Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China3 and has remained the one overarching policy in subsequent versions (NPC of PRC 2002, 2007, 2013, 2015, 2017).

1.2. Heritage ‘Resuced’–The Southern Project

The ‘rescuing mission’ has been manifested through various conservation projects since the ‘16-character Policy’ was articulated. One of the recent campaigns concerns the south and southeast part of Shanxi Province. This area holds the highest concentration of pre-Yuan Dynasty4 timber historic buildings in China, which make up for about 50% of all the surviving ones in the country5. The national scheme Nanbu Gongcheng (Southern Project) lasted for a decade from 2005–2015, during which restoration projects of 105 national Protected Cultural Heritage Sites (PCHS)6 with pre-Yuan timber structures were carried out (China Relics News 2016). The primary purpose of the scheme was to rescue these early timber structures. Unlike most of the previous ‘rescuing’ projects, the ‘threat’ that prompted this project was not any dramatic disaster, but mainly negligence and lack of maintenance. Some of the structures had not gone through any major restoration in the past two centuries, resulting in their severely dilapidated state. It is also fair to say that the project’s initiative was a result of academic research which accumulated over the last few decades and which revealed the significance of these historic buildings as evidence of China’s architectural evolution (The Restoration Institute of Ancient Architecture 1958; Yang 1994; Chai 1999; Y. Xu 2003; X. Xu 2009; Chai 2013).

1.3. Outlining the Issue–Religious Spaces as Cultural Heritage

Among the 105 sites included in the Southern Project, 95% are, at least historically, religious spaces7. A majority of 74% are Buddhist or Taoist–the two mainstream religions in China. The rest of the temples are worshipping spaces for folk beliefs and other deities (Table 1). For many of the sites, the subjects of worship do not necessarily belong to only one particular religion/belief, or their religious status has changed over time. Nevertheless, the statistics show that among these early timber historic buildings, a dominant majority of them are, or at least once were, spaces for worship.

Table 1.

Percentage of religious functions among all religious sites included in the Southern Project.

The recent history of these sites deserves some attention as well. During the first three decades after the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) (1949AD) and especially during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976AD), many of these sites ceased to be temples and were turned into venues with secular functions, such as schools and grain storage spaces, as part of the ‘socialist transformation’ movement8. Many of them were also confiscated as public or collective properties at the same time. For some of the sites, the worshipping activities were discontinued while for a small number of them, according to the memories of the senior villagers in the case region, the worshipping activities still took place rather quietly even though the sites were not officially temples anymore. This situation was not exclusive to this area but was happening throughout the country (Smith 2015). After the Cultural Revolution, most of the ‘socialist organisations’ in these sites gradually moved out. A small number of them remained used for secular public functions, while many others faced an uncertain future. In the meantime, the ‘heritagisation’ process picked up speed after the Cultural Revolution, and many of these sites were designated as PCHS9. As a result of a national movement to utilise heritage as the testimony of the “richness of China’s indigenous culture”, some of them became temples again (ibid., p. 212). The sites included in the Southern Project have all been given the highest heritage status (national PCHS) in the country. The dual process of the transformation of these sites led by the post-Cultural-Revolution religious and heritage policies will be discussed more in detail in the following sections. The juxtaposition of their multi-fold status is highly relevant to the discussion and analysis of their current state and the future.

It is worth mentioning that a majority of these sites are located in semi-rural or rural areas, where social changes and urbanisation have brought dramatic transformation to the communities and the way of living around them.10 With the dwindling and aging rural population and a more and more secular society, the current state and future of the sites in their post-restoration era are entangled in these changes too. Since the completion of the restoration projects, questions started to surface regarding how these places of worship, which may or may not be religious spaces anymore, would fit into contemporary society.

1.4. Existing Gaps and the Structure of the Article

While the issue of sustainable use/reuse of cultural heritage sites has prompted a considerable amount of literature in China, much of its early focus was on industrial heritage, which extended to recent heritage and vernacular heritage in the last few years (Wang 2006; He 2010; Ye 2016; Hangzhou International Urbanism Research Institute and Research Institute of Urban Management of Zhejiang Province 2014; Liu 2010; Sun 2015; Lu 2001). The State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH)’s considerations of project documentation and archiving, as well as capacity building of traditional craftsmen and heritage professionals during the Southern Project have indeed been a starting point of addressing the issue of managerial sustainability. They are, however, only a few limited aspects regarding sustainability, which also concerns the fundamental understanding of what roles these (former) religious heritage sites play in the local communities and the day-to-day management, sustainable functions and stakeholder participation. Despite the obvious concern and consensus of these aspects from various stakeholder groups revealed in this research, the existing literature regarding early timber architectural heritage remains focused on technical issues of restorations, documentations and conservation planning (Yang 1994, C. Li 2011, Shi and Li 2011, Zhang 2010, T. Xu 2014). It is also concerned almost solely with the conservation of their tangible materials with few exceptions (T. Xu 2014). Moreover, the complexities of these religious spaces as cultural heritage are generally avoided and little literature has been contributed to this topic, even though it has prompted some contentious public debates in recent years (Tam 2018a). It is thus the objective of this article to investigate not only the challenges that are observed, but also the deeper underlying issues within current heritage management mechanisms. I therefore hope to provoke broader discussions regarding the sustainable future of religious spaces as cultural heritage in China.

The rest of the article is structured as following: the methodology section explains the epistemology chosen for this research based on its objective, and outlines the specific methods used in data collection and analysis. Section 3 presents the data obtained during the research and the results of the analysis, focusing on the current situation of the religious cultural heritage sites in the case region of Shanxi, the perceptions, opinions and power of the various stakeholder groups regarding the religious and heritage status of these sites. It also provides a closer look into a specific site to illustrate how the various forces are transforming and sustaining the sites, as well as the latest policy development in the region. The discussion section then summarises the main issues presented in the previous section and finally, the conclusion outlines the article’s contribution to knowledge as well as a suggestion for further research.

2. Methodology

To achieve the objective of the article, it is necessary to unwrap the complexities of these sites without asserting a presumptuous thematic framework beforehand, as it is revealed during this research that such complexities can only shine through by presenting the detailed empirical data with a non-reductionist narration. The research methodology is chosen to understand the conservation processes and the current situation of the research subjects as a complex system. The case region is thus studied on two levels–a broad coverage of the current situation in the region which provides the scope of generalisation and a bird’s eye view of the system, and a more detailed examination into a specific case within the region to understand the entities, variables and their interrelationships. The data analysis is carried out to understand how a system structured by the legislative and administrative frameworks is manifested as a generative mechanism in play, namely the conservation practices. The analysis of the structure is placed vis-à-vis the empirical observations of the current situation to understand the underlying mechanism, and perhaps more importantly, the abnormalities and unexpectedness which influence the outcome (Easton 2010) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The strata of realities in the case study.

The data collection for the site was conducted through desk-based research, semi-structural interviews and on-site observations. The semi-structural interviews and on-site observations are essential to provide a multi-angled lens through which to understand the complex system. While interviews provide first-hand insights of the opinions and preferences of the various stakeholders and their relationships with each other, on-site observations reveal the realities presented by people’s behaviours and experiences. Two fieldwork studies were carried out in the case region (Changzhi, Jincheng and Yuncheng Municipalities), Taiyuan, the capital city of Shanxi Province and Beijing, the capital of PRC. A total of 71 interviews were conducted, and 58 sites were visited, among which 48 were included in the Southern Project, but all of them have been restored in recent years.

The desk-based research collected information on the relevant legislations, regulations, and administrative frameworks. Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with stakeholders under six categories, including:

- (a)

- National officials in SACH;

- (b)

- Local level officials in related heritage management departments (provincial, municipal, and district/county level);

- (c)

- On-site managers of the heritage sites;

- (d)

- Community members;

- (e)

- Heritage professionals;

- (f)

- And craftsmen and artisans.

A specific set of 7–8 questions was designed for each category, to understand their position and responsibilities regarding these sites, their relationships with other stakeholder groups, their opinions towards the conservation and functions of these sites, as well as their challenges regarding their positions and their visions for the future of these sites. Each interview lasted for approximately 60 min. Interviews with on-site managers or caretakers were mostly conducted as walking interviews within the heritage sites, while the rest of the interviews were conducted as sit-down interviews. Besides interviews, on-site observation was documented with field notes, photographs, videos and mapping, related to information around the heritage sites, their settings, people’s behaviours in and interactions with space and the activities related to the sites, such as temple fairs, religious activities, and the intangible cultural heritage practices happening on and around the sites.

3. Results

3.1. The Current State of the Sites

Based on the status of accessibility and functions, several categories can be summarised to help illustrate the current situation of these historic religious places as heritage sites. Among the ones visited during the fieldwork, about 35% of them are accessible to the public, either for no cost or with a small charge. The rest of the sites are hard to define because many of them are mostly closed except for several occasions during the year when they are open for villagers or worshippers to use, or for sporadic amateur enthusiasts for historic buildings to visit. For the convenience of analysis, I define the ones that are still being used occasionally for religious practices as ‘partially accessible’, while the ones that no longer host any religious activities as ‘non-accessible’ (Table 3).11 The examples given under the category descriptions are no doubt only vignettes of a few specific sites; nevertheless, they illustrate a vivid representation of the overall situations among the sites that were visited. Even though the phenomena on each site may vary, it is possible to find the shared mechanisms that contribute to these phenomena, which will be discussed in Section 3.2.

Table 3.

Current status of accessibility of visited sites during fieldwork12.

3.1.1. Category A–Accessible

Most of the sites that are regularly accessible to the public have management units set up within them, with 5–20 staff employed under the administrative system of cultural heritage, depending on the size and location of the sites. They are mostly not registered as official religious sites. Thus, no resident monk may stay on site13. However, most of the sites are considered religious spaces by visitors, even if the purpose of their visits could be sightseeing, visiting historic places, or worship. There are usually images of the subjects of worship installed in these temples, which could be either historic or contemporary. For most visitors, the presence of statues is the primary indication that these sites are active spaces of worship.

A proportion of these sites are also tourist attractions, run as non-profit organisations. For these sites, the income from tourism is required to be handed over to the government. Their maintenance expenses are then distributed through the centralised financial system (Tam 2018b). Private tour companies manage a minority of them. These companies are responsible for funding the daily maintenance and minor restorations of the sites, and in return, they are given the right of use of the sites (Tam 2018c).

Either way, it is not an easy task to sustain the financial balance of these sites. One of the temples visited during the fieldwork, run by a private tour company, is located in a relatively convenient location right next to a major highway. The temple complex is extensive, and there are residential Buddhist monks on site. Thus, the temple is also known as an active religious site. The company that manages it has invested in some development projects to provide necessary tourist infrastructure. Compared to most of the other sites, this one is expected to be relatively advantageous in the accessibility and capacity to attract visitors. However, according to the on-site managers, the company is now struggling to maintain a financial balance because domestic tourism expenditure has reduced in recent years. During the latest visit, the tourist area, namely where the restaurants and shops are located, is nearly empty and few visitors can be spotted there on a warm spring weekend day.

3.1.2. Category B–Partially Accessible

This category covers a variety of situations. The sites in this category are not open during most of the year. But worshippers, mostly from the village or the nearby villages, can access the temples during certain times of the year for religious activities. Many of these temples also host annual temple fairs, which happen at various times throughout the year, depending on the local traditions and the deities that are worshipped in the temples. Similar to the ones in Category A, they are not managed primarily as religious sites–meaning they are not officially registered as religious venues–but as cultural heritage sites.

According to the interviews, for the on-site managers and cultural heritage administrations, keeping the physical health and safety of the historic places is their utmost priority. The religious activities are somehow implicitly tolerated given that this priority is guaranteed. The extent to which they are tolerated, however, varies depending on the attitudes of the local authorities of cultural heritage. Such tolerance levels may also change over time.

Two situations encountered during the fieldwork may shed some light on this complex and changing situation. According to the interview with one of the local level officials, there was once a plan to invite a monk to reside in a very remote temple to keep it ‘alive’ as a Buddhist temple. However, the invited monk eventually decided to leave because the location of the temple was too secluded, and the number of worshippers was dwindling. The interviewed official also added that this was only possible a few years ago as the ‘religious policy’ at the time was rather relaxed, but it would not be possible now since the implementation of ‘religious policy’ has become stricter (Tam 2018d).14 A similar situation happened in another temple dedicated to a folk deity, where, as seen during a visit a few years ago, there were some statues of deities, commissioned by the villagers upon the completion of its restoration project in 2013, installed in the temple but with their faces masked by red clothes, meaning that they had not been inaugurated. By the time of the fieldwork in 2018, according to the onsite manager of the temple, those statues are still not inaugurated because “it is not allowed” now (Tam 2018e).

3.1.3. Category C–Non-Accessible

The sites in this category are usually the ones where only a single historic building remains in the temple complex (Figure 1), or those who do not host any religious activity anymore. The reasons for that can vary, too. According to the interviews with the caretakers of these sites, it is either because the locals no longer consider this place a space of worship, the sites are simply too remote, or that it is considered to be “too dangerous to open them” as national PCHS (Tam 2018f, 2018g, 2018h). However, as national PCHS, these sites are not entirely inaccessible. The caretakers usually open the doors on demand to visitors who travel there to visit these historic buildings.

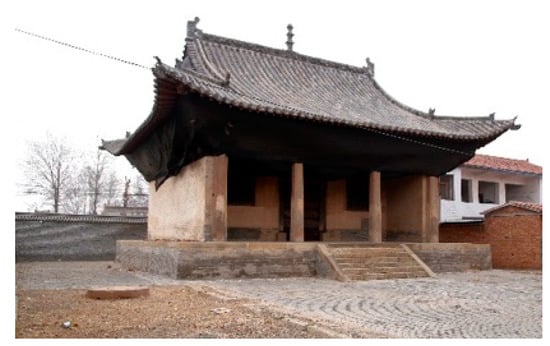

Figure 1.

The Jin Dynasty main hall of this temple was restored in 2012 but has remained unused and locked up since then. It is experiencing leaking and animal infestation by the time of the fieldwork in 2018. (© Lui Tam).

Even though the historic buildings are closed, sometimes the villagers still host religious or ceremonial activities around them because the sites of the temples are considered symbolic places for public gatherings and ceremonies. There was a funeral taking place in the public square right next to the only historic building left of a temple upon the visit during the fieldwork. Even though the building was not open, villagers were sitting around it to watch the performance and the procession of the funeral (Figure 2). According to them, this place had always been a space for gathering. They also thought it would be beneficial to welcome tourists to their village to see the historic building. Although when asked what the tourists should see when they come to visit this empty old building, the villagers laughed and said, “That is for you experts to figure out. You know better than us!” (Tam 2018i).

Figure 2.

The villagers are gathering around the only remaining historic building of this temple to watch the funeral performance and procession taking place in the public square. (© Lui Tam).

3.1.4. Several Sides of One Coin

It is evident that there is one challenge which all the sites face—as historic religious spaces designated as heritage sites with the highest protection status, they do not seem to sit comfortably in the rapidly changing contemporary society of China, where the dwindling religious and rural population is accompanied by the unpredictable implementation of ‘religious policies’ and the priority to protect the tangible remains of the sites as heritage. The authorised value assessment of these sites published by SACH often downplays the intangible associations which constitute part of their meaning, and instead highlights their significance as precious tangible evidence of Chinese architectural history. Such preference is enhanced by the separation of administrative responsibilities and disciplinary divide among heritage professionals, which will be elaborated in the following sections.

Moreover, as vividly demonstrated by the villagers’ opinions quoted in Section 3.1.3, the ‘heritagisation’ process also takes away the ‘ownership’ feeling of the villagers towards these sites. Many of them believe that ‘experts’ who study the architectural significance of these sites have more authority to identify their value. While their behaviours in using these sites indicate that they do not necessarily ignore the values of the space which bear meanings to them personally, they just do not seem to consider such values beyond the realm of their personal and community life.

3.2. The Structure behind and the Parties Involved

3.2.1. The Religious and Heritage Legislation and Policies

It is essential to look at the policy formation process in the post-Cultural-Revolution era regarding both religious and heritage policies to understand the systems behind, especially because state policies have an infiltrating influence in China, whose administrative system is a primarily top-down one. Regarding the case study, heritage policies have the most dominating effect on the sites, whereas these historic temples, some of which still host religious activities, are also drawn under the scope of religious policies.

Besides the 16-character Policy mentioned in the introduction, the shifting focus of SACH’s policies in the last two decades has shaped the landscape of heritage management in the country. The first decade of the 2000s saw an increasing interest in, and emphasis on, conservation plans of the PCHS. This was partly influenced by the advocacy of the director of SACH then who has a professional background in urban planning (Editorial Department of Archicreation 2006). The Southern Project was also initiated during the tenure of this director. In years subsequent to 2012, SACH started to promote several other emphases such as ‘protection and utilisation’, and ‘revitalising the heritage’ (Y. Li 2013) (Central Office of the Communist Party of China, and Office of the State Council 2018). These focuses are strongly influenced by the specific values that are held by the directors of SACH but are also a result of the increasing consideration for the sustainability of PCHS which surfaces during the last decade.

Regarding religious activities, there is no specific mention in all the relevant legislation and regulations of cultural heritage, including the legislation of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH), whose scope includes some ceremonies, festivals and traditional folk customs which have religious connotations or are rooted in various folk beliefs (NPC of PRC 2017, 2011). Some of the religious activities happening around the PCHS are considered as ICH expressions. According to the legislation, it is encouraged to provide physical venues for the inheriting of these traditions (NPC of PRC 2011).

In 1982, the same year when the first Cultural Relics Protection Law was implemented, the state announced a policy to return the property ownership of some of the religious places to religious organisations (Xi 1985). During this process, some of the properties were handed back to religious associations other than temple committees. One of the reasons for this is that the traditional organisational structure in temples has changed since 1949 and was disrupted during the Cultural Revolution, during which most monks/priests were evacuated from the temples as their functions were transformed. For that same reason, some of the properties remain collective or public properties, managed by the village committees or the local authorities during the implementation of the religious policies after 1982. In 2004, the state published the Regulation on Religious Affairs (revised in 2017). According to this regulation, the ‘religious venues’ (Zongjiao huodong changsuo) are required to be registered with the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA) as either a permanent religious space or a temporary one (SARA 2017). Although not mentioning PCHS, it is stated in the regulation that activities in the religious venues should follow cultural heritage legislation and regulations, implying the acknowledgement of certain religious venues being PCHS.

It is evident that in all these areas, the legitimacy of practising religious activities in PCHS is expressed implicitly. As shown in the last section, this ambiguity contributes to the varying ways of implementing policies regarding religious practices in PCHS. According to one of the local officials, the religious departments tend not to register historic temples as religious venues. However, newly built temples do not have the same unspoken restriction. This void of clear policy articulation is amplified in the administrative system, which will be elaborated in the next sub-section.

3.2.2. The Administrative Systems and the Public Sectors

There are several administrative systems involved in the management of these sites working in parallel. On the state level, both the management of PCHS and ICH is placed under the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China (MCT).15 The PCHSs are the responsibility of SACH, an independent bureau under the jurisdiction of the MCT whereas ICH is managed directly by the ministry.16 Religious affairs are managed by SARA, which is placed directly under the United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (UFWD). At local levels, the management of PCHS and ICH is the responsibility of the corresponding cultural departments, and, mirroring the state level, usually belongs to two separate offices. Similarly, religious affairs are managed by the religious departments in the local government.

There is a vertical and a horizontal structural dimension of control in the participation of the public sector in the decision-making concerning these sites. The vertical one stays within the line of cultural heritage administrations. The power structure for decision-making and supervision is a straightforward and primarily top-down pyramid organisation. While the provincial and national level administrations’ priories are clearly focused on heritage conservation, such an objective becomes less determining when it is operated on a local level because it is more restrained by the overall strategic policies of the local level government. It is revealed during the interviews that although most of the officials in the cultural heritage administrations are aware of the religious functions of the sites, they are extremely cautious in discussing this aspect even if they do not consider religious activities to be negative. Most of the interviewees do not consider the religious function to be a single sustainable solution for the sites in the case region, while all of the interviewees in the public sector praise adaptive reuse as a possible solution, and “cultural related function” is often considered a politically correct and quick answer. However, when they are asked how these “cultural functions” might be sustainable financially and managerially, their reluctance is obvious when it comes to the implementation, especially among local level officials.

The horizontal dimension of control concerns the relationship between the administrations of cultural heritage and other relevant governmental bodies, including the ones mentioned above in this section as well as others such as planning, construction and tourism. This is where the complex status of these religious cultural heritage sites can potentially be addressed on an administrative level. Although in theory, each administration enjoys the autonomy of decision-making within their responsibilities, the power held by these administrative bodies is far from homogeneous (Smith 2015). In line with the ambiguity shown in the legislation and policies concerning cultural heritage and religious practices, there seems to be a tendency not to cross over the borders between administrations to avoid overstepping each other’s authority, nor is there sufficient communication between them. As most of the sites are not registered as religious venues, SARA and other religious administrations remain distanced from the direct management of the sites, while the cultural heritage sector tolerates the religious practices on site with a cautious approach and shows little desire to elevate the religious connotations of these sites as part of their ‘heritage values’. The void in the legislative framework is mirrored and amplified in between the administrative systems.

3.2.3. Heritage Professionals and the Role of ‘Experts’

Heritage professionals play a significant role in decision-making as well as implementation processes. Their relationship with the other mechanisms is complex, dynamic, and sometimes overlaps. These characteristics are demonstrated in the communication and interaction during the conservation processes. According to the interviews for this research, heritage professionals are considered to be the ones who hold the capacity and knowledge to understand the significance of the heritage sites from the perspectives of their disciplines. As mentioned in the introduction, the increased national attention to the case region was primarily the result of the advocacy of academics and the subsequent ‘heritagisation’ process. Traditionally, heritage professionals mostly come from the ‘mainstream’ disciplinary backgrounds (namely architecture, archaeology, history, urban planning and so on). This is still very much the case in China. The conservation strategies suggested for the PCHS in the case region have a strong tendency to prioritise their tangible remains, even if the religious practices or other intangible traditions are present. Compared to the academic research dedicated to the tangible remains of these historic buildings, the body of literature regarding their religious functions is also significantly smaller.

Despite the technical nature of heritage professionals’ involvement, their preferences are also influenced by the administrative system outlined in the last sub-session. There is indeed an increasing awareness of the social and cultural values of heritage among heritage professionals since the revision of the Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China (China Principles) in 2015,17 which would potentially include their religious functions, yet the constraints from the system have minimised its impact in implementation. The objectives, scale and administrative set-up of the Southern Project all contribute to the fact that the ‘rescuing mission’ of the tangible remains often overrides other proposed interventions. For example, a conservation plan which was supposed to provide guidelines regarding the interventions during the restoration projects, based on considerations of the site’s tangible health, social-cultural associations with the communities, as well as the future use, might not have been approved by the time the restoration project had already been completed. The ‘experts’, who are usually heritage professionals but take on the role of decision-makers at the approval panels organised by the cultural heritage administrations, tend to take a more conservative position that also leans towards the preservation of the tangible remains and settings of the sites. This preference is a result of both their disciplinary backgrounds as well as their responsibilities which are bestowed by the administrations. Such a preference is especially obvious when it comes to national ‘experts’ who sit in the consultation panels and act as the ultimate decision-makers on behalf of SACH.

As a result of the above-mentioned factors, the involvement of professional consultants in the decision-making process for these sites bears a strong tendency to regard these sites as historic buildings other than religious spaces. Other professionals who work with the religious and intangible aspects of the sites are rarely consulted. Furthermore, the advocacy of heritage professionals can seldom escape the constraints of the administrative system. The disciplinary gaps in knowledge among heritage professionals correspond with the voids between the legislative and administrative frameworks.

3.2.4. The Local Community

The local community is often referred to as a single group of stakeholders. It is, however, a broad umbrella that covers many different representatives of knowledge and preferences, although the level of power they hold is relatively similar. Specifically, in the case region, the local community is referred to as ‘the residents’ of the surrounding villages or towns. They can either play the role of caretakers, part of the collective ownership of the sites, worshippers or temporary volunteers. Each individual of the community does not hold much power in the decision-making process regarding the national PCHS, but collectively they are part of the forces that are transforming the sites, manifested mainly in two aspects in the case region.

The first aspect is represented by the caretakers. They are the first responders for the security and hazard prevention of the sites, as well as basic housekeeping. The technical maintenance of the historic buildings is not considered their responsibility but requires interventions from the local authority. Their involvement in the decision-making process depends on the level of activeness of the individuals and how receptive the local authorities are. The caretaker mechanism is a ‘grass-roots’ management tool put in place for the national PCHSs in the case region, which is part of the top-down administrative system laid out in Section 3.2.2. They are appointed by the local authorities, but many of them volunteer to be in this scheme. Most of the caretakers are residents who share a strong sense of responsibility and belonging towards the sites.

As the ‘key holders’, they are responsible for letting the worshippers use the temples for religious practices, given that the local authority allows it. Based on the interviews, they would have to respond according to the shifting positions of the authority in implementing the ‘religious policy’, as demonstrated in Section 3.1. They nevertheless have their own various opinions on whether there should be religious practices in these historic buildings. Many consider it beneficial to continue the religious functions of these heritage sites, because “they cannot be called old temples anymore if there are not even images of the deities here” and most of them think it is acceptable to allow worshippers from around the villages to conduct religious activities in or around the temples as long as they are safe. Some admit to the fact that the worshipping population is shrinking and consider it suitable to introduce cultural or tourism functions.

The second aspect is demonstrated by the organisation of community committees. Most of the villages or towns have community committees who also play a role in the daily management, use and safeguarding of the heritage sites in their communities. In the case region, many of the sites host temple fairs once or twice a year, and the community committees are usually the ones who organise these activities, including funding, recruiting volunteers, hiring, purchasing, managing and safeguarding the sites during the temple fairs. Exceptionally active involvement can be observed in the case of Longwang Temple where the community committee not only manages and organises the temple fair but also installs exhibitions and other functions in the temple. A similar situation can also be observed in the cases of Dongyue Temple in Yuquan Village, Zhongzhuang Village in Yangcheng County, and Baiyu Temple in Jiaodi Village. As a committee, the community members have more power to collect resources from various channels and to create synergies with nearby villages. The case of Longwang Temple in Dongyi Village, which will be elaborated in the next section, suggests that the more active and involved the community committees are, the more enthusiastic and prouder of the sites the community members are.

It should be observed that despite the two aspects noted above, the general involvement of the local communities in the decision-making process remains low. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, for some of the sites, the fact that they are designated as national PCHS weakens the sense of ownership among the community. It is revealed in several interviews that the local community thinks the responsibility of taking care of these buildings now belongs to the state only (Tam 2018f, 2018j, 2018k). In some cases, as described in Section 3.1, the lack of ownership feeling is aggravated by the shrinking religious and rural populations. Secondly, the local community’s involvement is not always encouraged. Regulations, the local authorities’ priority to ensure the safety of these sites and the concern of the unpredictable implementation of religious policies sometimes prevent the local community from engaging with the daily use and management of the sites. This is not to draw the broad conclusion that heritage designation necessarily weakens the connection between the heritage sites and the local community, but rather, to point out a compelling revelation that this connection is one of the most challenging tasks in up-keeping the sustainability of these religious heritage sites.

3.3. A Closer Look–the Case of Longwang Temple

3.3.1. Overview

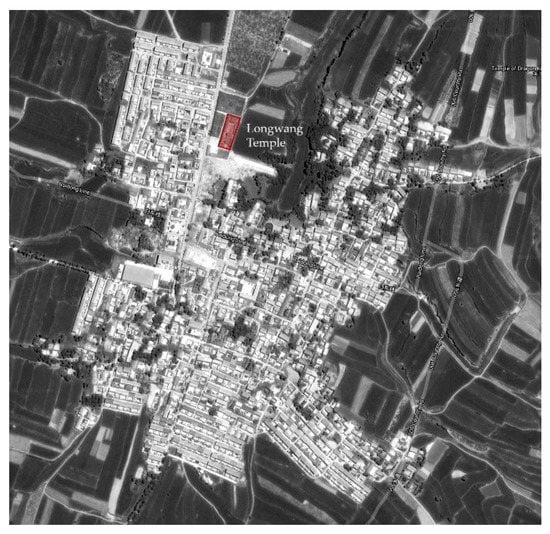

This sub-section introduces and analyses the case of Longwang Temple, one of the 105 sites included in the Southern Project, where local effort can be seen to contribute to keeping the historic temple alive and, in that sense, also improve the socio-cultural sustainability of the area. Longwang Temple is located in Dongyi Village, Changzhi Municipality. The temple is situated in the northeast corner of the village, slightly distanced from the historic residential area (Figure 3). Based on building archaeology studies of the timber buildings in the region, the main hall can be dated back to the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234AD) (SACH 2015a).18 The temple complex was used as a village primary school during the 1950s–1960s. It became a middle school in 1977 and was designated a provincial PCHS in 1986 when the county cultural heritage department became the responsible government body for the site. However, it was not until 2004 when the middle school moved out, and the site went into the custody of the village committee, and subsequently, the Chenjiachuan community management unit (Chengjiachuan Banshichu) (collective ownership). Some of the buildings were briefly used as residences from 2004 until 2006 when the site was designated a national PCHS. In 1992 and 2004, there were two minor restorations by the village and the local authority (Institute of Shanxi Ancient Architecture Conservation 2007). The restoration of Longwang Temple under the Southern Project was carried out in 2013. Traces of the school were wiped out during this restoration but could still be seen from old photos (ibid.). There are currently two courtyards in the compound. The first courtyard is formed by the main gate, the stage and two side halls. The second courtyard is formed by the stage, the main hall with two ‘ear halls’, and two side halls (Figure 4). During the restoration of the historic buildings, a small public garden was also created to the west of the temple, and the surrounding environment was renovated.

Figure 3.

Map of Dongyi Village and Longwang Temple (base map: © Google Maps).

Figure 4.

The second courtyard of Longwang Temple (© Lui Tam).

The name of the temple suggests that it is a Taoist temple. It is not a registered religious space now (SARA 2018). However, religious activities are happening in the temple around the main hall during most time of the year, where villagers or visitors pay tribute to the Dragon Kings, the Yan Emperor and some other deities. The two side halls of the second courtyard are now installed with exhibitions. The one on the east side has a brief and somewhat dated exhibition about a registered intangible heritage from Dongyi Village–Kangzhuang. The one on the west side is a relatively new exhibition about agriculture and the everyday life of this village and the region. It is one of the very few places seen in the case region where the local community tries to use the space actively.

3.3.2. Heritage Space as a Community Museum

According to the interviews, the exhibition was initiated by Chengjiachuan community unit, as well as a few representatives of the village. The themes of the exhibition’s two installed sections are the Four Seasons (agriculture) and the Everyday Life (clothing, cuisine, abode, and transportation). A third one about Life and Death is scheduled to be set up in 2018. The exhibition is small, and the planning is phased out over a few years because of the limited funding and resources. Nevertheless, it is a valuable example of how local effort can still pull together different resources from various sectors to make things happen. The exhibition also involves the community by encouraging villagers to donate their old tools or household objects to it (Figure 5). The small museum is by no means the main attraction for visitors who come to visit the temple–according to the caretaker, most visitors are still attracted by the Jin Dynasty main hall and its national PCHS status. It is, however, a remarkable achievement to use the heritage site to tell the story of the local community and to give more meaning to the ancient temple in its contemporary setting.

Figure 5.

The community museum in Longwang Temple (© Lui Tam).

3.3.3. Heritage Space for Religious Activities

The village holds one of the biggest annual temple fairs in the region, a major Taoist festival called Dragon Raising-head (Longtaitou). While this festival is also celebrated in other temples in the region as well as throughout the country, the celebration in Dongyi Village has become well-known in recent years. According to the villagers, the celebration has never paused even during the Cultural Revolution. Indeed, since the restoration of the Longwang temple in 2013 that the local community decided to ‘revitalise’ the festival even more. The effort has increased the festival’s popularity among the local community, hence there is a higher degree of motivation from the village to keep this festival going, which increases the possibility of keeping this temple and the traditions alive.

The festival is also a significant occasion to showcase the intangible heritage of the village and the region. Two such items were observed during the three-day festival in 2018: Kangzhuang (lit. ‘carrying costumes’) and Yuehu (lit. ‘music house’). These two examples of intangible heritage are demonstrations of how living traditions can be passed to the next generation but in different ways. Both of these traditions are part of the Saishe culture which is practised across the Shangdang region in Shanxi Province (Xiang 1996; Shen 2008a). Yuehu is a somewhat exclusive tradition which is only practised by one community (Shen 2008a, 2008b).19 They are responsible for the music during the rituals as one of the three essential elements of the Saishe culture. According to the interviews in the research, the inheritors take pride in the fact that Yuehu has been registered as a provincial intangible heritage expression and have been passing it on for more than six generations. Kangzhuang, on the other hand, is intrinsically inter-generational. The tradition involves the participation of an older and a younger generation–young children of the village, dressed in costumes, are tied to the tops of long poles which are carried by adults during the parade (Figure 6). Because the purpose of doing Kangzhuang is to pray for the good health of the children, families in the village participate spontaneously every year.

Figure 6.

The Kangzhuang parade during the Longtaitou Festival in Dongyi Village, March 2018 (© Lui Tam).

Traditions such as these which are practiced throughout the region undoubtedly have their origins in religious practices based on Taoist and local folk beliefs. They are allowed and, to a certain extent, encouraged by the authority as ICH. During the interviews, it has been revealed both explicitly and implicitly that these traditions are “fine as long as they are described as folk traditions instead of religious practices” (Tam 2018l).

3.3.4. A Space to Gather

Besides being the physical space for the religious festival to take place, the Longwang Temple also acts as a social space during the festival. Villagers who live in other towns or cities come back to the village to join the festival. Visitors from the region also flock to Dongyi. Volunteers of the village come to the temple to help out with fire-watching and other logistics. All kinds of social interactions can be observed in the temple. According to the interviews with these community members, many of them remember the temple as their school where they spent a few years of their childhood and that memory, even though not so physically present on site after the recent restoration, is very much alive and vivid among that generation. The historic temple also becomes a social space where schoolmates and teachers come together during the festival.

This situation is not exclusive to Longwang Temple, but a typical case in many sites that were visited during the fieldwork. This layer of the history is indeed not one to be forgotten and is very prominent among the generation which still has a close relationship with the temples. It was mentioned multiple times during the interviews that if these buildings were not used as schools (or sometimes storage spaces for grains), they would not have survived the Cultural Revolution. However, this layer of the history is often considered to be subordinate to the ‘original history’ of the heritage site during which it was used as a functioning religious space. It is also true that this chapter of history is considered less important because it is more ‘recent’. Among the sites visited during the fieldwork, only in one of them, the grain storage buildings built during the ‘Socialist Transformation’ movement, were deliberately preserved as part of the historical environment of the temple. It is worth entertaining the argument that this layer of the history might be crucial to restoring the connection between the people and the heritage and deserves more attention.

3.4. A Way Forward

There are emerging changes at both the state level and the local level policies, in the public and private sectors. In 2013, the State Council announced the cancellation of the approval process “to change the functions of, to hypothecate or to transfer the non-state-owned national PCHS which are restored with government funding”. This approval process was previously implemented by the local level heritage administrations (State Council of PRC 2013). It suggests that the state intends to loosen the restrictions for the adaptive reuse of the non-state-owned national PCHS.20

Since 2017, the Shanxi Provincial government has launched a provincial campaign called ‘Safeguarding Civilisation’ (Wenming Shouwang Gongcheng), with the primary aim to ‘revitalise cultural heritage’ (‘rang wenwu huo qilai’). One of the focuses of the campaign is to encourage the private sector to participate in the utilisation of cultural heritage and to ‘adopt’ some of the heritage sites.21 The campaign organised a few public events to promote the ‘adoption’ scheme and has published a booklet including the introductions of the first sites that are open for adoption (Bureau of Cultural Heritage of Shanxi Province, and Shanxi Association of Industry and Commerce 2018). Although the campaign does not limit the ‘adoption’ to non-national PCHS, according to the provincial and local level officials, the national and provincial PCHS will only be open to the scheme if it works on the lower level PCHS. However, as of the time of the fieldwork for this research, according to the local level officials, the scheme has yet to inspire the enthusiasm of the broader private sector, the reasons for which include a lack of detailed regulations, directives on practicalities and successful precedents to provide confidence.

4. Discussion

The challenges and the desire to prolong the sustainability of the historic temples in the case region are clear. During the interviews with local level officials, they unanimously mentioned that the utilisation of these buildings is the most prominent challenge after the Southern Project. Based on the analysis of the collected data, we can summarise that some of the contributing factors to this challenge are intrinsic to the sites–their small scale, their secluded locations, as well as their relative physical fragility as historic timber buildings. The others are manifestations of deeper issues within the operative mechanisms and the systems in the background.

As demonstrated by the case study, we can identify several ‘gaps’ between the legislative and administrative structures operating in the realms of tangible and intangible heritage as well as religions. For religious spaces as cultural heritage, while all three systems are intrinsically relevant to their management, they do not have an effective overlap that covers the complex status of these sites. The mechanisms generated by these systems, especially the programme of PCHS, are designed to provide the authority of identification and protection. However, the case study illustrates that the mechanisms do not necessarily generate intended sustainable outcomes. The entities within these mechanisms, such as the various groups of stakeholders, through their interactions during the decision-making and implementation processes, exercise their power and influence to some extent, but none of them has the ultimate power to determine the outcomes. The PCHS mechanism, with the most direct influence over these sites, nested under the current field of tangible heritage, does not effectively integrate the intangible, religious and the community aspects of these sites, which, as demonstrated in the case of Longwang Temple, could act as catalysts for a more sustainable future for the sites as well as the surrounding communities. It explains why the case of Longwang Temple, although shining a positive light, is only a sporadic and rare occurrence at present.

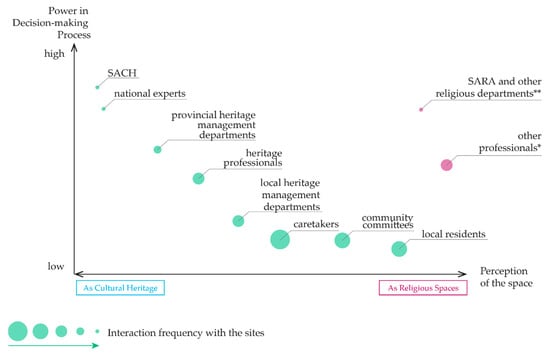

The following graph (Figure 7) summarises the power-preference relationship among the various groups of stakeholders demonstrated in the case study. It is clear that those who hold higher power in the decision-making process tend to consider these sites primarily as cultural heritage rather than religious spaces, while those who consider the sites as both and also actively participate in the religious activities on site enjoy much weaker advocacy in this process. On the other hand, their frequency of interactions with the sites is much higher. These interactions are also part of the forces that are transforming these sites, albeit at a much slower pace. As seen in the case study, neither maintaining their original religious functions nor seeking for a reuse seems to suffice as a single solution to the sustainability of these sites. A balanced representation of the multi-layered status of these sites as both religious and heritage spaces, such as the case of Longwang Temple, may foster a more diverse, inclusive and resilient future.

Figure 7.

Power-preference relationship of stakeholders. * Other professionals include those who specialise in religious studies, ICH, or other relevant studies revolving the sites. They are seldom consulted in the decision-making process. ** Although SARA and other religious departments might hold higher power on the administrative level compared to some of the other stakeholders, they are not usually included in the decision-making process because these sites are considered primarily as PCHS.

5. Conclusions

Through a case study of the current situation and challenges regarding the sustainable future of timber historic temples in Shanxi Province, the article is intended to contribute to the presently insufficient discussion of religious spaces as cultural heritage sites in China. The complex status of historic religious space as heritage and its implications highlight not only challenges regarding this specific type of heritage, but also more fundamental issues lying in the heritage management mechanisms behind the observable phenomena. The research, beginning with an analysis of the case region and then digging deeper into the structure behind, has sought to untangle the complex web of ever-changing realities and an influential centralised system that governs heritage management in China. The approach that narrowly prioritises these sites as the tangible testimony of architectural history seems to be staggering behind the development of the overall heritage industry and receives little excitement from the current talking points in China. The limitation of this approach is also a result of the less-than-diverse disciplinary expertise involved. Fundamental changes within the system may only happen when the accumulated effect within these mechanisms achieves enough momentum. The current shift in the paradigm of heritage studies among professionals, the increasing awareness from the local community to engage and participate, as well as the evolving priorities of the administrations motivated from within and from their interactions with other sectors, may in time precipitate such changes. The article, by discussing the forces that have been transforming these sites as both religious and heritage spaces, thus also calls for further research to reconsider the conventional approach to such typical timber architectural heritage in China.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bureau of Cultural Heritage of Shanxi Province, and Shanxi Association of Industry and Commerce. 2018. Shan Xi Sheng She Hui Li Liang Can Yu Wen Wu Bao Hu Li Yong Wen Wu Jian Zhu Ren Yang Xiang Mu Tui Jie Shou Ce [Promotional Pamphlet of the Heritage Building Adoption Project for the Society to Participate in Cultural Heritage Conservation in Shanxi Province]; Taiyuan: Bureau of Cultural Heritage of Shanxi Province.

- Central Office of the Communist Party of China, and Office of the State Council. 2018. Guan Yu Jia Qiang Wen Wu Bao Hu Li Yong Gai Ge De Ruo Gan Yi Jian [Directives Regarding the Reform of the Protection and Utilisation of Cultural Relics]; Edited by Office of the State Council. Beijing: Xinhua News Agency.

- Chai, Zejun. 1999. Collected Works of Chai Zejun on Ancient Architecture. Beijing: Wenwu. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Zejun. 2013. Shan Xi Gu Jian Zhu Wen Hua Zong Lun [Comprehensive Research on the Architectural Culture of Shanxi]. Beijing: Wenwu. [Google Scholar]

- China Relics News. 2016. Shan Xi Sheng Nan Bu Zao Qi Jian Zhu Bao Hu Gong Cheng [Conservation Project of the Early Architectural Heritage in South Shanxi]. Zhong Guo Wen Wu Bao [China Relics News] 2: 6. [Google Scholar]

- County Government of Changzhi. 2018. Chang Zhi Xian Dong Yuan She Hui Li Liang Can Yu Wen Wu Bao Hu Li Yong “Wen Ming Shou Wang Gong Cheng” Shi Shi Fang An [The Implementation Protocol for the ‘Safeguarding Civilisation Project’ to Motivate the Society to Participate in Cultural Heritage Conservation in Changzhi County]; Changzhi: County Government of Changzhi.

- Easton, Geoff. 2010. Critical realism in case study research. Industrial Marketing Management 39: 118–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial Department of Archicreation. 2006. Bringing the cultural heritage protection into reality: Special interview with Mr. Shan Jixiang, director of State Bureau of Cultural Relics. Archicreation 4: 130–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hangzhou International Urbanism Research Institute, and Research Institute of Urban Management of Zhejiang Province. 2014. Wen Hua Yi Chan Bao Hu He Li Yong Yan Jiu: Di Si Jie “Qian Xue Sen Cheng Shi Xue Jin Jiang” Zheng Ji Ping Xuan Huo Dong Huo Jiang Zuo Pin Hui Bian [The Research on Conservation and Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage: Proceedings of the awarded articles of the fourth ‘Qian Xuesen Golden Award of Urbanism’]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang People’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Rodney. 2013. Heritage: Critical Approaches. Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- He, Chenjia. 2010. Bei Jing Chuan Tong Si He Yuan Jian Zhu De Bao Hu Yu Zai Li Yong Yan Jiu [The Conservation and Adaptive-reuse of Beijing Traditional Courtyard Buildings]. Master’s thesis, Department of Design and Arts, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Shanxi Ancient Architecture Conservation. 2007. The Restoration Project Design Proposal of Dongyi Longwang Temple in Lucheng, Shanxi Province; Taiyuan: Shanxi Provincial Cultural Heritage Bureau.

- Li, Chao. 2011. Shan Xi Nan Bu Quan Guo Zhong Dian Wen Wu Gu Jian Zhu Bao Hu Gui Hua Zhong Bao Hu Fang Fa Yan Jiu [A Study of the Methodologies of Conservation in Conservation Planning of the Nationally Protected Heritage Buildings in Southern Shanxi]. Master’s thesis, School of Architecture, Taiyuan University of Technology, Taiyuan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Tiansheng, and Lijun Yang. 2002. Xi She Cun Wang Xing Yue Hu Kao [Study of the Yuehu family Wang in Xishe village]. Journal of Jindongnan Teachers College 6: 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yun. 2013. Li Xiao Jie: Zai Li Yong Rang Jian Zhu Yi Chan Hui Ji Min Sheng [Li Xiaojie: ‘Revitalisation’ of Architectural Heritage to Benefit People’s Livelihood]. Guangming Daily. Available online: http://www.wenming.cn/ft_pd/wh/201307/t20130724_1364827.shtml (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Liang, Jing, and Cunrui Liu. 2018. Ling Yang Wen Wu, Lai Shan Xi Ba! [Adopting cultural heritage, come to Shanxi!]. Economic Daily. Available online: http://paper.ce.cn/jjrb/html/2018-04/14/node_6.htm (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Liu, Qing. 2010. Research on Protection and Utilization of Material Cultural Heritage in Qingdao Area. Ph.D. thesis, Shandong University, Shandong, China. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yadong. 2007. Chong Ji Yu Ji Yu Bing Cun—Guo Jia Wen Wu Ju Ju Zhang Shan Ji Xiang Tan Wen Hua Yi Chan De Bao Hu Xian Zhuang Yu Zhan Wang [Coexistence of Impact and Opportunity—An interview with the director of SACH SHAN Jixiang about the current conservation situation and vision of cultural heritage]. Art Market 3: 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, David. 1998. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Di. 2001. Li Shi Xing Jian Zhu Zai Li Yong Zai 20 Shi Ji De Fa Zhan Zu Ji [The development of adaptive reuse of historic buildings in the 20th century]. Time + Architecture 4: 80–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipal Government of Changzhi. 2017. Chang Zhi Shi Dong Yuan She Hui Li Liang Can Yu Wen Wu Bao Hu Li Yong “Wen Ming Shou Wang Gong Cheng” Shi Shi Fang An [The Implementation Protocol for the ‘Safeguarding Civilisation Project’ to Motivate the Society to Participate in Cultural Heritage Conservation in Changzhi Municipality]; Changzhi: Municipal Government of Changzhi.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2017. Yearly Statistics of Population Census. Available online: http://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- NPC of PRC. 2002. Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (2002 Revision); Beijing: Standing Committee of NPC.

- NPC of PRC. 2007. Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (2007 Amendment); Beijing: Standing Committee of NPC.

- NPC of PRC. 2011. Intangible Cultural Heritage Law of the People’s Republic of China. In Order of the President of the People’s Republic of China No. 42; Edited by the 19th Session of the Standing Committee of the 11th National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: Standing Committee of NPC. [Google Scholar]

- NPC of PRC. 2013. Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (2013 Amendment); Beijing: Standing Committee of NPC.

- NPC of PRC. 2015. Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (2015 Amendment); Beijing: Standing Committee of NPC.

- NPC of PRC. 2017. Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (2017 Amendment); Beijing: The NPC Standing Committee.

- NPC of PRC. 2018. Guo Wu Yuan Ji Gou Gai Ge Fang An [The Institutional Reform Plan of the State Council]. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2018-03/17/content_5275116.htm (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- Peng, Minghao. 2011. A Study on the Selection of Wood in the Construction of Ancient Buildings in the Southern Area of Shanxi Province. Master’s thesis, Peking University, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Provincial Government of Shanxi. 2017. Shan Xi Sheng Dong Yuan She Hui Li Liang Can Yu Wen Wu Bao Hu Li Yong “Wen Ming Shou Wang Gong Cheng” Shi Shi Fang An [The Implementation Protocol for the ‘Safeguarding Civilisation Project’ to Motivate the Society to Participate in Cultural Heritage Conservation in Shanxi Province]; Taiyuan: Provincial Government of Shanxi.

- SACH. 2008. Zhong Guo Wen Wu Shi Ye Gai Ge Kai Fang San Shi Nian [China’s Cultural Heritage Entreprise in the 30 years of ‘Reform and Opening Up’]. In Zhong Guo Wen Wu Shi Ye Gai Ge Kai Fang San Shi Nian [China’s Cultural Heritage Entreprise in the 30 years of ‘Reform and Opening Up’]. Edited by SACH. Beijing: Wenwu. [Google Scholar]

- SACH. 2015a. Dong Yi Long Wang Miao [Dongyi Longwang Temple]. Information Database of National PCHS. Available online: http://www.1271.com.cn/NationalHeritageDetail.aspx?KeyWord=6-0378-3-081 (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- SACH. 2015b. Information Database of National PCHS. Available online: http://www.1271.com.cn/AnalyzeSummary.aspx (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- SARA. 2017. Regulation on Religious Affairs (2017 Revision); Beijing: State Council.

- SARA. 2018. Registered Religious Venues in Lucheng. In Information Database of the Registered Religious Venues; Beijing: State Council. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Danli. 2008a. Lu Cheng Shi Dong Yi Cun Long Wang Miao Ji Ying Shen Sai She Kao [Investigation of the Yingshen Saishe Rituals and the Longwang Temple of Dongyi Village in Lucheng County]. World of Antiquity 2: 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Danli. 2008b. Lu Cheng Yue Hu Xian Zhuang Diao Cha [Investigation of the current situation of the Yuehu community in Lucheng]. Drama (The Journal of The Central Academy of Drama) 4: 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Qianfei, and Chao Li. 2011. A Study of the Defining Protected Domains in the Preservation Planning of Historical Building—A case study on national key heritage ancient architectures protection planning in Southern Shanxi. Journal of Xi’an University of Architecture & Technology (Social Science Edition) 1: 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. A. 2015. Contentious Heritage: The Preservation of Churches and Temples in Communist and Post-Communist Russia and China. Past & Present 226: 178–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council of PRC. 2005. Guo Wu Yuan Guan Yu Jia Qiang Wen Hua Yi Chan Bao Hu De Tong Zhi [Notice from the State Council Regarding Strengthening the Conservation of Cultural Heritage]; Beijing: State Council of PRC.

- State Council of PRC. 2013. Guo Wu Yuan Guan Yu Qu Xiao He Xia Fang Yi Pi Xing Zheng Shen Pi Xiang Mu De Jue Ding [State Council’ Decision on the Cancellation and Decentralisation of Several Administrative Approval Processes]; Edited by State Council. Beijing: State Council of PRC.

- State Council of PRC. 2018. Wen Hua He Lu You Bu Zhi Neng Pei Zhi Nei She Ji Gou He Ren Yuan Bian Zhi Gui Ding [The Responsibilities, Internal Institutions and Staffing Requirements of the MCT]; Beijing: State Council of PRC.

- Sun, Hua. 2015. Chuan Tong Cun Luo Bao Hu De Xue Ke Yu Fang Fa—Zhong Guo Xiang Cun Wen Hua Jing Guan Bao Hu Yu Liyong Zou Yi Zhi Er [The discipline and methodology of the conservation of traditional villages—The second discussion of the conservation and utilisation of China’s rural cultural landscape]. China Cultural Heritage 5: 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018a. “The Revitalization of Zhizhu Temple—Policies, Actors, Debates”. In Chinese Heritage in the Making—Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations. Edited by Christina Maags and Marina Svensson. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 245–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018b. Interview by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Zhangzi County. March 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018c. Interview by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Yangcheng County. March 24. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018d. Interview by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Pingshun County. March 7. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018e. Interview by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Lingchuan County. March 13. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018f. Interview by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Wuxiang County. March 9. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018g. Interview by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Gaoping City. March 10. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018h. Interview by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Gaoping City. March 15. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018i. Interview 2 by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Pingshun County. March 7. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018j. Interview by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Lingchuan County. March 11. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018k. Interview 2 by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Lingchuan County. March 13. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Lui. 2018l. Interview by Lui Tam, semi-structural interview, Dongyi Village. March 18. [Google Scholar]

- The Restoration Institute of Ancient Architecture. 1958. Jin Dong Nan Lu An Ping Shun Gao Ping He Jin Cheng Si Xian De Gu Jian Zhu [Ancient architecture in the four counties of Lu’an, Pingshun, Gaoping and Jincheng in Southeast Shanxi]. Wenwu Cankao Ziliao [Cultural Relic References] 3: 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- The Project Department of the Restoration of Dongyi Longwang Temple. 2012. Lu Cheng Shi Dong Yi Long Wang Miao Zheng Dian Xiu Shan Gong Cheng Shi Shi Gong Xu Ji Lu [The Implementation Records of the Restoration of the Main Hall of Dongyi Longwang Temple in Lucheng]. Changzhi: SACH. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lin. 2006. The Study of Reuse of the Old Building on Concept and Method. Master’s thesis, Department of Architecture, Southeast University, Nanjing, China. [Google Scholar]

- WHC. 2018. World Heritage List Statistics. World Heritage Centre. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/stat/ (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- Xi, Zhongxun. 1985. “Yi Ding Yao Zhua Jin Luo Shi Dang De Zong Jiao Zheng Ce [It is necessary to urgently implement the religious policy of the Party]”. In Xin Shi Qi Tong Yi Zhan Xian Wen Xian Xuan Bian [A Selected Collection of Literature of the Unified Front in the New Era]. Beijing: Central Party School Press, Available online: http://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/64184/64186/66702/4495440.html (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- Xiang, Yang. 1996. “Shan Xi Yue Hu Kao Shu [Study of Yuehu in Shanxi]”. Music Study 1: 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Yan. 2011. “Quan Guo Xian Cun Song Qian Gu Jian Shan Xi Zhan 3/4 [Shanxi holds 3/4 of all the pre-Song Dynasty Architecture in the Country]”. Available online: http://www.sxrb.com/sxwb/aban_0/03_0/2488917.shtml (accessed on 19 January 2019).

- Xu, Tong. 2014. Shan Xi Nan Bu Wen Wu Jian Zhu De “She Qu” Huo Hua Li Yong Yu Gui Hua Ce Lue [Promotion of Community Utilization for Historic Architectures in Southern Shanxi Province through Conservation Planning Strategies]. Zhuang Shi 257: 119–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Xingyun. 2009. A Study on the Temple Architecture of the Song Dynasty, the Jin Dynasty and the Yuan Dynasty in Linfen and Yuncheng Districts. Master’s thesis, School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yitao. 2003. The Temples of the Five Dynasties, the Song Dynasty and the Jin Dynasty in Changzhi and Jincheng District. Ph.D. thesis, School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Haiming. 2018. World Heritage Craze in China—Universal Discourse, National Culture, and Local Memory. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Zirong. 1994. “Lun Shan Xi Yuan Dai Yi Qian Mu Gou Jian Zhu De Bao Hu [Discussion on the Conservation of Pre-Yuan Dynasty Timber Architecture in Shanxi]”. Cultural Relic Quarterly 1: 58, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Danxiao. 2016. The Research of Monument Protection and Reuse in the Yuexiu District of Guangzhou. Master’s thesis, Department of Urban Planning, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Zhenhai, and Xuetao Wang. 2018. Shui Zai Shan Xi “Ren Yang” Gu Jian Zhu Wen Wu? You Wen Wu Mi Du Zi 30 Nian Zhao Gu Gu Miao [Who is ‘adopting’ heritage buildings in Shanxi? There is a Heritage Enthusiast who Invests to Take Care of an Old Temple for 30 Years by Himself]. The Paper. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1983546 (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Zhang, Peng. 2010. Jin Nan Quan Guo Zhong Dian Wen Wu Gu Jian Zhu Jia Zhi Ping Gu Fang Fa Yan Jiu [The Research on the Value Assessment Methods of the National Heritage Sites in Southern Shanxi]. Master’s thesis, School of Architecture, Taiyuan University of Technology, Taiyuan, China. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Referred to as ‘16-character Policy’ from hereafter. The policy includes four short phrases which means ‘conservation as the main purpose; rescuing as the priority; reasonable utilisation; and enhancing management.’ |

| 2 | The term ‘cultural relics (Wenwu)’ is still widely used in the legislative contexts regarding cultural heritage in China, even though the term ‘cultural heritage (Wenhua yichan)’ is considered to be more comprehensive in technical and academic documents and is now widely used in the official documents, including notices, circulars and speeches, as well as some of the regulations. In 2005, the State Council used ‘cultural heritage’ instead of ‘cultural relics’ in the title of the official announcement, indicating a shift of the official term, as well as a shift of understanding towards cultural heritage (Liu 2007, State Council of PRC 2005). For more in-depth discussion of the implications and evolution of the use of these terms, see Yan (2018, pp. 30–67). |

| 3 | Referred to as ‘Cultural Relics Protection Law’ from hereafter. |

| 4 | Yuan Dynasty: 1260–1368AD. |

| 5 | There is no consensus of the exact number of surviving pre-Yuan Dynasty timber structures in China, as the dating of many of them is still contested. According to the research of the well-respected architectural historian Zejun Chai, there are about 440 pre-Yuan timber structures in China and 350 of them are in Shanxi Province, which makes up to 80% of the nation-wide total, and the Southeast part of Shanxi holds half of the pre-Jin Dynasty (1115–1234AD) timber structures of the entire country (80 out of 160) (Xie 2011). But there is also statistics from the Third National Cultural Relics Survey which estimates the four municipalities of the South and Southeast Shanxi (Changzhi, Jincheng, Yuncheng, Linfen) alone hold about 350 of the pre-Yuan timber structures (Peng 2011). Nevertheless, it is a consensus that Shanxi holds at least more than 75% of the pre-Yuan timber structures while the four municipalities of South and Southeast Shanxi hold about 50% of them (China Relics News 2016). |

| 6 | The term ‘Wenwu baohu danwei’ has been translated in various ways in academic publications and official documents. Literally it means ‘protected cultural relic unit’. In this article, ‘Protected Cultural Heritage Site’ is used as a more straightforward translation. |

| 7 | The statistics are based on the historic purpose of the sites upon their construction but not necessarily the representation of their current functions. The evolution and current states of their functions will be further discussed in the following sections. |

| 8 | The evolution of use of temples went through several different periods from 1949 to the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1978. It was not a linear development. Nevertheless, many of them had at least lost their religious status at some point, if not permanently. For more analysis on this period see Smith (2015). |

| 9 | Among the 105 sites, only two of them were designated as national PCHS before 1982, Yonglegong Taoist Temple in Ruicheng County, Yuncheng Municipality and Guangsheng Temple in Hongtong County, Linfen Municipality (SACH 2015b). |

| 10 | According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the rate of urbanisation grew from 38% to 56% from 2001 to 2015. Rural population dropped from 54.1% to 41.5% from 2007–2017 (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2017). |

| 11 | It should be noted that the status of these sites is not static. They could change between categories for any specific reason at any time. The calculation is based on the data collected through the fieldwork for this research. |

| 12 | Although Buddhist temples seem to have a slightly higher percentage to be accessible and those with other beliefs seem to have a higher percentage to be non-accessible, there is not enough evidence other than this statistic that indicates the correlation that temples with a more ‘mainstream’ religious function are more likely to be accessible. |

| 13 | Among the 58 sites visited during fieldworks, only two have residence monks/nuns, one of which is run as a tourist attraction as well as a temple. The tourism company that runs the site provides free accommodation for the monks and the monks receive alms from worshippers for their daily expenses. |

| 14 | ‘Religious policy’ is used with apostrophe here because what the local official referred to is not exactly the written policy of the state regarding religious practices and religious venues, which has not changed significantly, but more about how such policy is implemented on a local level, which changes over time and is very often unpredictable. |

| 15 | The Ministry of Cultural and Tourism was founded in March 2018, which merges and replaces the previous Ministry of Culture and China National Tourism Administration (NPC of PRC 2018). This merge will inevitably bring yet more changes to the management of PCHS. It is however beyond the scope of this article to discuss these changes in detail. |

| 16 | The management of ICH is under the jurisdiction of an internal department of the MCT, called the Secretary Department of ICH (State Council of PRC 2018). |