Roots, Routes, and Routers: Social and Digital Dynamics in the Jain Diaspora

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Connecting Roots, Routes, and Routers

1.2. Jainism and (Im)Mobility

1.3. Migration and Religion

2. Jainism on the Internet

2.1. An Introduction to Jainism Online

2.2. Bias in Search Engine Results

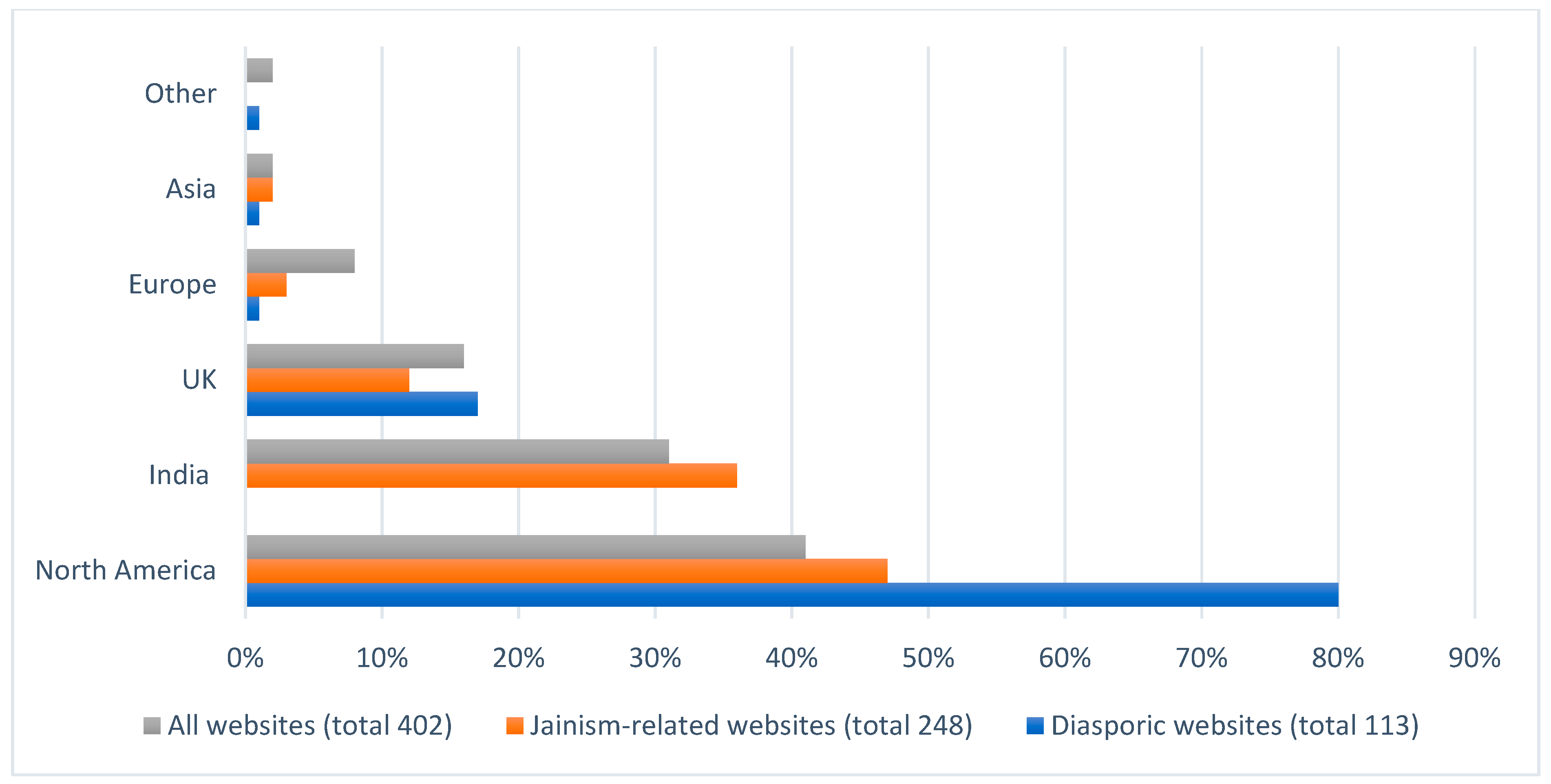

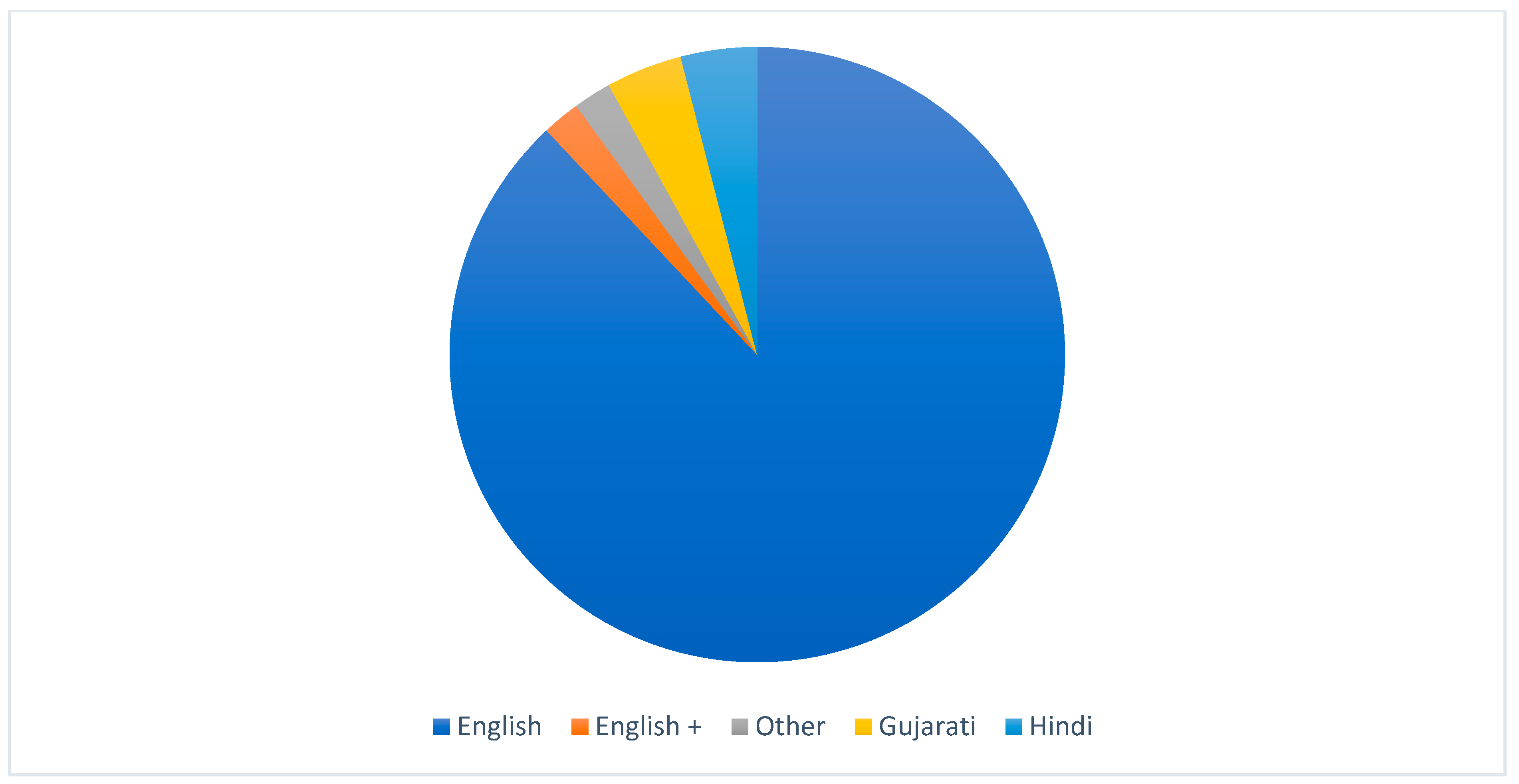

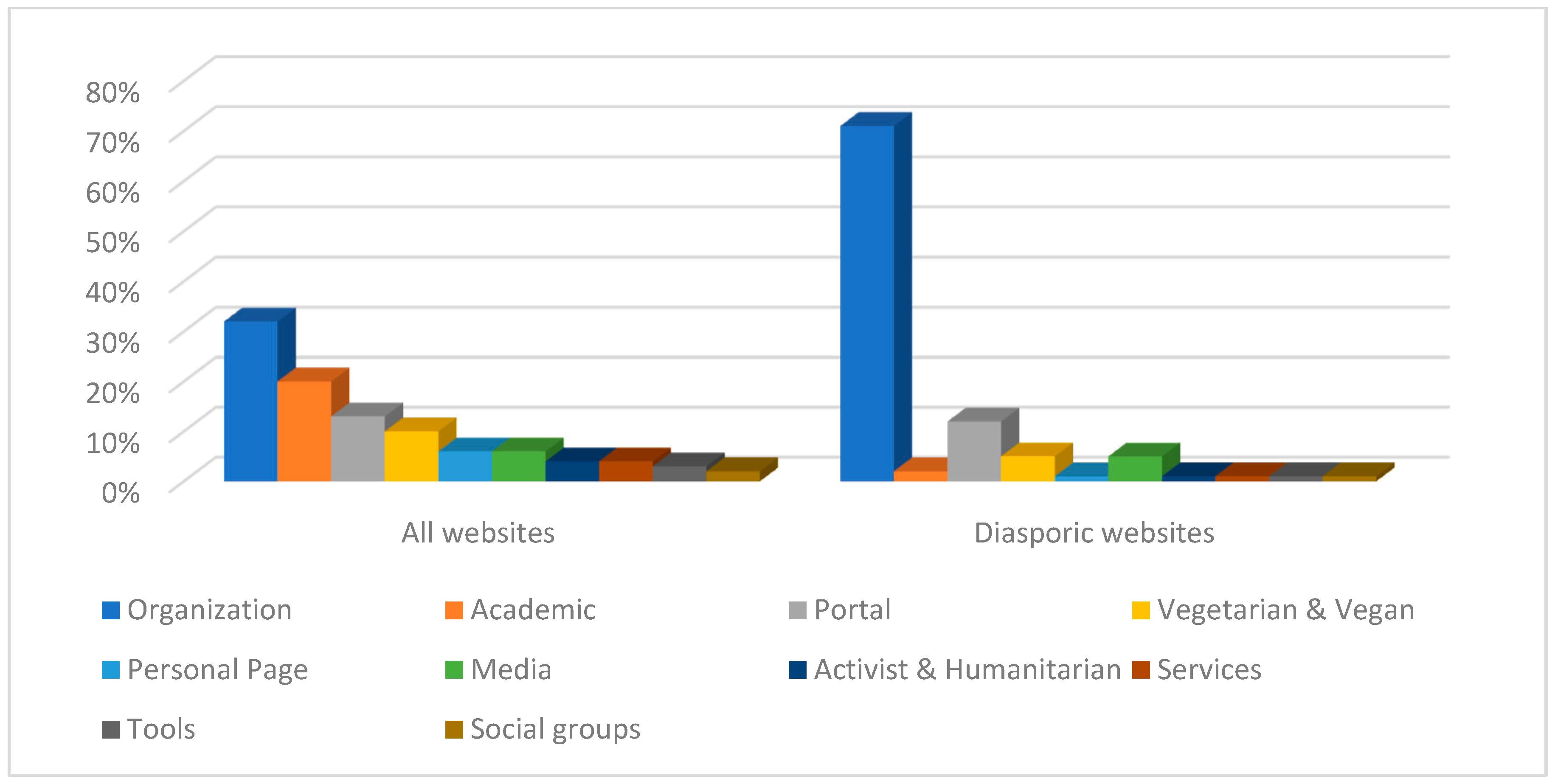

Such a ‘U.S. dominance of search’ is linked to the prevalence of English in our corpus. Eighty-eight percent of all websites use English as their main language, with another 2% using English and another language (usually Hindi or Gujarati) in equal measure. When only taking into account websites containing Jainism-related content, the exclusive use of English is slightly less all-pervasive at 84%, with another 3% of websites combining English with Gujarati or Hindi. When looking exclusively at diasporic websites, the proportion of websites using English exclusively is as high as 98%.In the language of PageRank9, US sites simply have more authority: more links leading to them. They note that sites have existed longer in the US, where much of the early growth of the internet occurred, and that this may give US sites an advantage. Add to this that early winners have a continuing advantage in attracting new links and traffic, and US dominance of search seems a foregone conclusion.

2.3. Internet as the Ultimate Diasporic Space?

3. The Impact of Digital JAINISM on Lived JAINISM

3.1. Interpersonal Connections

The above statements, taken from the transcript of a focus group conducted with students of the Jain Student Association at the University of Michigan, illustrate how CMC can be used for religious purposes. Interviews indicate that such religious uses of CMC, as well as the availability of new digitally mediated ways of engaging with the Jain tradition such as watching videos, studying texts, performing a ritual, or even playing a game can foster an increased feeling of belonging to the Jain community, even in those who do not actively engage in a local Jain organization. Respondents reported feeling a strong connection to the global Jain community while watching a livestream of an initiation ceremony in India:And when my family members in India call via Skype—we don’t speak so very often—but they will definitely get messages through such as “don’t cook with green veg today”.My family set up the laptop in the [home] temple, so I could join them in doing ārtī on special occasions. Using Skype, I can hear the music, they can hear me reciting, and we can talk afterwards.

This feeling of ‘being a part of it’ can best be explained when we consider these online activities as a form of shared practice. Activities may not always be performed together, at the same place, or at the same time, but even without face-to-face contact or direct interaction, users are conscious of the fact that they share their experience with others, and common narratives, places, and practices are reinforced in the process. This can suffice to trigger feelings of belonging and connection to Jainism and the Jain community.R: There was a live feed this summer of a big dīkśā ceremony, I think in AhmedabadA: Yeah, I watched that too.R: It was this huge event and I had never seen a dīkśā, I don’t know what goes on. I think it was …A: On ParasTV14.R: Yes, so my mom and me were kind of watching that livestream. To feel like … like being a part of it.

3.2. Doctrinal Connections: Digital Media and the Diasporic Knowledge Economy

Whereas the importance of digital media in maintaining interpersonal connections between Jains in different places was not very apparent in the website and mobile application corpora, their role as sources of information was. In addition to the practical information the bulk of organizational websites provide, many websites in the corpus described above also offer a wide range of doctrinal information and religious resources. This can consist of primary materials, such as pdf versions of sutra texts (e.g., the website Jain eLibrary (Jain e-library 2019) and the mobile application Jain Pathshala (Arihant Solutions 2015; Vishal Shah 2015)) or video clips of sermons (e.g., Jain Muni Pravachans (Vishapp 2015), see Section 3.3 below), as well as secondary materials, such as summaries of Jain doctrine and practice (e.g., Jainworld 2018).We encourage the kids and also the adults in the pāṭhśālā to ask questions. When no answer can be found here, we ask a scholar or call a sādhū in India. Although we prefer to contact a pandit. They are more exposed. For basic things, we ask the kids to Google it.(S. Atlanta)

Not all respondents were this pragmatic regarding different, potentially contradictory, narratives online. In Antwerp, D. related how he does not trust online doctrinal information.You have to do your own critical reading. It is interesting because only the Internet allows you to do that. You can look at different suggestions and compare and build, until you will get an explanation that you trust. This is not possible when you are going to one guru or even read in the regular library.(R., London)

A few respondents would also contact authority figures in India, if a satisfying answer could not be obtained in another way. This seems to be much more prevalent in Antwerp than in the United Kingdom or the United States, perhaps because of the Antwerp community’s more frequent trips to India.I rarely use websites to get any information. I don’t rely on those things. I find them full of errors. I rather turn to books or some knowledgeable person in India. I’m being very hard about these websites but it is not for me.(D., Antwerp)

3.3. Devotional Connections?

In India, Jain ascetics have a multifaceted function within the Jain community. They are venerated by the lay community as examples of renunciation and the path to liberation. However, in addition to this, they are often very learned, considered a valuable source of information on all aspects of Jain doctrine, and turned to for advice in personal matters too.These days, a lot of people […] will tape things: lectures, speeches by sādhūs and pandits and share it via WhatsApp and such. The main thing we miss here in the US is the teachings of the sādhūs and sādhvīs. And its only through recent technologies that we can access these more easily here.(A., Detroit)

Although not all Jain ascetics are open to having their pravacans recorded, many apps (e.g., Vishapp 2015) and websites (e.g., Pragyasagar 2019) provide access to Jain ascetics’ preachings, usually in the form of embedded YouTube videos. Such materials are rather popular—the majority of my respondents in all three field sites at least occasionally watched such videos. They provide the viewer with doctrinal information, but, as interaction with the monastic community is seen by many Jains as a central element of Jain religious practice, they also provoke feelings of devotion. Naturally, the ways individual Jains use these materials differ. Whereas some integrated viewing pravacans into their regular spiritual practice, others said they would play pravacans in the background while cooking dinner or studying. However, such worldly uses of the materials were invariably (partly) motivated by emotions, with respondents stating it “calmed their nerves”, had “a comforting effect”, or made them “feel less alone”.Because we go to India for a short time, so you don’t have that much interaction, you don’t get to go to a lot of discourses. So I think those monks and nuns that are using electronic media … you know, traditionally they might be against it but obviously they’ve adopted it. […] For us from our perspective, in the West. It is a really good thing.(S. London)

The degree to which ascetics avoid any electrical appliances (microphones, lights, and fans) and digital devices (computers, smartphones) now varies from ascetic order to ascetic order. Those orders that do make use of digital devices and have developed a digital presence usually circumvent the injunction against personal property by having a lay follower be the official owner of the device or putting such a lay follower in charge of making, updating, and running websites and social media accounts. As Jain ascetics, with few exceptions, do not travel by mechanical means, Jains living outside India tend to have limited access to the ascetic community. For them, this negotiated digital presence can be especially impactful.if I need a bit of motivation, I do go online and put on any random video of the Acharya and just listen.(A., New York)

3.4. Building and Maintaining a Community

Digital media do not just affect how and to what degree Jains living in the diaspora can (re)connect with their South Asian roots or find information. They also impact the routes individual Jain migrants take, providing new ways for individual Jains to find each other, and organize and build communities in new countries of residence. Wherever more than one family of Jains settles, chances are that they will try to find each other, get together, and at least share their experience of migration, if not organize some form of collective religious gatherings or events. The process of building new communities based on a current place of residence usually follows the same trajectory. The first contacts and get-togethers tend to be very informal. Often, when the number of Jains is large enough, these get-togethers move to the level of a formal organization. This tends to be followed by the procuring of land for the building of a Jain center and/or temple. In North America, we even see the development of an umbrella organization, JAINA. Digital media have different social functions in the different stages of such organizational development. First, they provide a billboard and a platform to find each other. Once the core network is established, they become a very important tool for organization and discussion.When I came here as a student in the 80s, there was no central point for Jains to find each other and get together. Now, you can Google to find each other and arrange meetings and activities online.(D., Atlanta)

3.4.1. A Website as a Business Card

3.4.2. Organizing and Affirming Diasporic Communities

Diasporic organizations often seek to instill such a feeling of ‘being a part’ of a larger Jain community in their members and those visiting their websites. Different discourses of belonging and community are disseminated online.Parents feel involved more, they know what goes on, what their children do here. […] That is what it is about: feeling you are a part of what goes on at the Jain center, even when you cannot be physically present.(S., Atlanta)

Jain Diaspora is the JAINA initiative to connect all the Jain communities living in 36 countries outside of India and thereby drive greater unity and cohesiveness in the global Jain community.

Dear JSOC Family, I hope you all have recovered from our Mahavir Jayanti celebrations! Let us carry forward this momentum with us and bring it to our regular bhavanas as well.(Newsletter of the Jain Samaj of Colorado (JSOC 2019)

The excerpts above illustrate how three U.S.-based Jain organizations emphasize different levels of Jain community in their online communication. Again, the internet user is exposed to different competing narratives on Jainism—while the JAINA website tends to refer to the global Jain community, IDJO (International Digamber Jain Organization) seeks to fortify the digambar community, and the Jain Samaj of Colorado chooses a discourse indicating local unity and cohesion.Our mission is to create and bring together the community of Digamber Jains in USA and ultimately from the whole world.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alpers, Edward A. 2013. The Indian Ocean in World History. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota press. [Google Scholar]

- Arihant Solutions. 2015. Jain Pathshala. Google Play, vers. 4.5. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.jaindarshan.jainpathshala (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Balaji, Murali, ed. 2018. Digital Hinduism: Dharma and Discourse in the Age of New Media. London: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, Marcus. 1992. Organizing Jainism in India and England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, Marcus. 1994. Why Move? Regional and Long Distance Migrations of Gujarati Jains. In Migration: The Asian Experience. Edited by Judith M. Brown and Rosemary Foot. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 131–48. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, Martin. 1998. Sustaining ‘Little Indias’, Hindu diasporas in Europe. In Strangers and Sojourners: Religious Communities in the Diaspora. Edited by Gerrie ter Haar. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 95–132. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Peter. 2007. Can the Tail Wag the Dog? Diaspora reconstructions of religions in a globalized society. Nordic Journal of Religion and Society 19: 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cheruvallil-Contractor, Sariya, and Suha Shakkour, eds. 2016. Digital Methodologies in the Sociology of Religion. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, James. 1997. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Robin. 1992. The diaspora of a diaspora: The case of the Caribbean. Social Science Information 31: 159–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cort, John E. 2001. Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dhirajlal, Mehta. 2018. Facebook page of Dhirajlal Mehta Panditji. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/dhirajlal.mehta.5 (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Diminescu, Dana. 2008. The connected migrant: An epistemological manifesto. Social Science Information 47: 565–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diminescu, Dana. 2012. Introduction: Digital methods for the exploration, analysis and mapping of e-diasporas. Social Science Information 51: 451–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundas, Paul. 2002. The Jains, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, Myria. 2006. Diaspora, Identity and the Media: Diasporic Transnationalism and Mediated Spacialities. Cresskill: Hampton press. [Google Scholar]

- Halavais, Alexander. 2009. Search Engine Society. Cambridge: Polity press. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, Christopher. 2007. Diaspora on the Electronic Frontier: Developing Virtual Connections with Sacred Homelands. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 956–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, Gabriele Rosalie. 2009. Jaina in Antwerp: Eine Religionsgeschichtliche Studie. München: AVM. [Google Scholar]

- Henn, Sebastian. 2010. Transnational Communities and Regional Cluster Dynamics. The Case of the Palanpuris in the Antwerp Diamond District. Die Erde 141: 127–47. [Google Scholar]

- Henn, Sebastian, and Eric Laureys. 2010. Bridging Ruptures: The Re-emergence of the Antwerp Diamond District After World War II and the Role of Strategic Action. In Emerging Clusters: Theoretical, Empirical and Political Perspectives on the Initial Stage of Cluster Evolution. Edited by Dirk Fornahl, Sebastian Henn and Max-Peter Menzel. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, Harry H., and Tara M. Franz. 2004. New ties, old ties and lost ties: The use of Internet in diaspora. New Media Society 6: 731–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDJO (N.N.). 2018. International Digamber Jain Organization. Available online: www.idjo.org (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- Jain, Sulekh C. 1998. Evolution of Jainism in North America. In Jainism in a Global Perspective. Edited by Sagarmal Jain and Shriprakash Pandey. Varanasi: Pārśvanātha Vidyāpīṭha, pp. 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Yogendra. 2007. Jain Way of Life: A Guide to Compassionate, Healthy and Happy Living. Boston: JAINA. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Prakash C. 2011. Jains in India and Abroad, A Sociological Introduction. New Delhi: ISJS. [Google Scholar]

- Jain e-library (N.N.). 2019. Available online: www.jainelibrary.org (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- JAINA (N.N.). 2018. Available online: www.jaina.org (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- Jainism: Jain Principles, Tradition and Practices (N.N.). 2019. Available online: cs.colostate.edu/~malaiya/jainhlinks.html (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- Jainpedia (N.N.). 2018. Available online: www.jainpedia.org (accessed on 18 December 2018).

- Jainworld (N.N.). 2018. Available online: www.jainworld.com (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- JCCA. 2019. Jain Temple Antwerp. Jain Temple Antwerp Facebook Page. Available online: www.facebook.com/JainTemple.Antwerp (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- JCSF (N.N.). 2018. Jain Center of South Florida. Available online: www.jaincentersfl.org (accessed on 3 December 2018).

- JSGA (N.N.). 2019. Jain Society of Greater Atlanta. Available online: www.jsgatemple.org/ (accessed on 3 December 2018).

- JSOC. 2019. Jain Samaj of Colorado (N.N.). Available online: www.jainsamajofcolorado.org (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- Kapashi, Vinod. 1988. Jainism—Illustrated. London: Sudha Kapashi. [Google Scholar]

- Kapashi, Vinod. 1998. Jainism: The World of Conquerors. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Bhuvanendra. 1996. Jainism in America. Tempe: Jain Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Priya. 2012. Sikh Narratives: An Analysis of Virtual Diaspora Networks. eDiasporas Atlas. Available online: http://www.e-diasporas.fr/wp/kumar-sikh.html (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Miller, Daniel, and Don Slater. 2000. The Internet—An Ethnographic Approach. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Mon, Pann, and Madhukara Phatak. 2010. Search Engines and Asian Languages. In Net. Lang: Towards the Multilingual Cyberspace. Edited by Laurent Vannini and Hervé Le Crosnier. Caen: C&F éditions, pp. 168–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcu, Michaela. 2012. Migrants’ New Transnational Habitus: Rethinking Migration Through a Cosmopolitan Lens in the Digital Age. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38: 1339–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonk, Gijsbert. 2007. Global Indian Diasporas: Exploring Trajectories of Migration and Theory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oonk, Gijsbert. 2013. Settled Strangers, Asian Business Elites in East Africa (1800–2000). New Delhi: Sage Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Oonk, Gijsbert. 2015. Gujarati Asians in East Africa, 1880–2000: Colonization, de-colonization and complex citizenship issues. Diaspora Studies 8: 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paras TV (N.N.). 2019. Available online: www.parastvchannel.com (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- Pingali, Prasad, Jagadeesh Jagarlamudi, and Vasudeva Varma. 2006. WebKhoj: Indian language IR from multiple character encodings. Paper presented at 15th International Conference on World Wide Web, Edinburgh, Scotland, May 23–26; pp. 801–9. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, Alejandro. 2001. Introduction: The debates and significance of immigrant transnationalism. Global Networks 1: 181–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragyasagar (N.N.). 2019. Available online: www.pragyasagar.com (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- Radford, Mikal A. 2004. (Re) Creating Transnational Religious Identity within the Jaina Community of Toronto. In South Asians in Diaspora: Histories and Religious Traditions. Edited by Knut A. Jacobsen and Pratap P. Kumar. Leiden: Brill, pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- Scheifinger, Heinz. 2008. Hinduism and Cyberspace. Religion 38: 233–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheifinger, Heinz. 2018. The Significance of Non-Participatory Digital Religion: The Saiva Siddhanta Church and the Development of Global Hinduism. In Digital Hinduism: Dharma and Discourse in the Age of New Media. Edited by Murali Balaji. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Bindi V. 2011. Vegetarianism and veganism: Vehicles to maintain Ahimsa and reconstruct Jain identity among young Jains in the UK and USA. In Issues in Ethics and Animal Rights. Edited by Manish A. Vyas. New Delhi: Regency Publications, pp. 108–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Bindi V. 2017. Religion, ethnicity and citizenship: The role of Jain institutions in the social incorporation of young Jains in Britain and USA. Journal of Contemporary Religion 32: 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Bindi V., Claire Dwyer, and David Gilbert. 2012. Landscapes of diasporic religious belonging in the edge-city: The Jain temple at Potters Bar, outer London. South Asian Diaspora 4: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, Ninian. 1987. The importance of diasporas. In Gilgul: Essays on Transformation, Revolution and Permanence in the History of Religions. Edited by Anna Seidel, Shaul Shaked, D. Shulman and G. G. Stroumsa. Leiden: Brill, pp. 288–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tanuj, Chopra. 2014. Paras Tv. Apple App Store, vers. 1.2. Available online: https://itunes.apple.com/be/app/paras-tv/id911791519?mt=8 (accessed on 5 June 2018).

- Tsagarousianou, Roza. 2004. Rethinking the concept of diaspora: mobility, connectivity and communication in a globalised world. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 1: 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallely, Anne. 2002. From Liberation to Ecology: Ethical Discourses among Orthodox and Diaspora Jains. In Jainism and Ecology. Edited by Christopher Chapple. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Vallely, Anne. 2004. The Jain Plate: The Semiotics of the Diaspora Diet. In South Asians in the Diaspora: Histories and Religious Traditions. Edited by Knut A. Jacobsen and Pratap P. Kumar. Boston: Brill, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, Liwen, and Mike Thelwall. 2004. Search engine coverage bias: Evidence and possible causes. Information Processing & Management 40: 693–707. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, Liwen, and Yanjun Zhang. 2007. Equal Representation by Search Engines? A Comparison of Websites across Countries and Domains. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 888–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2009. Transnationalism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vishal Shah. 2015. Jain Pathshala. Apple App Store, vers. 2.0.1. Available online: https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/jain-pathshala/id948228683?mt=8 (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Vishapp. 2015. Jain Muni Pravachans. Google Play, vers. 1.0. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.andromo.dev331365.app399025 (accessed on 3 June 2018).

- Wiley, Kristi L. 2006. The A to Z of Jainism. New Delhi: Vision Books. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The research-project “Digital religion in a transnational context: Representing and practicing Jainism in diasporic communities” was made possible by a grant from the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO). It was coordinated and supervised by Prof. Dr. Eva De Clercq at University of Ghent, Belgium. |

| 2 | The number of Jains is under discussion. The last census of India, conducted in 2011, consultable on censusindia.gov.in, reported Jainism to be the religion of 0.37% of the population (just under 4.5 million individuals). However, there are concerns that not all Jains report their religion unambiguously in the census, stating caste or clan instead of religion, or combining categories, e.g., Hindu–Jain. If these concerns are correct, the actual number could be significantly higher. Outside India, counting Jains is often even more difficult, as religious affiliation is considered a private affair that should not be included in any census or administrative data. On the basis of estimates made by researchers, and data obtained from Jain organizations, it is assumed that between 250,000 and 300,000 Jains live outside India, in the diaspora. |

| 3 | An estimated 2000 Jains reside in Belgium, concentrated in and around the city of Antwerp. Within Antwerp, the focal point of community life is the suburb of Wilrijk. For more information on South Asian and Jain trade migration to Antwerp, see (Henn 2010, p. 134; Henn and Laureys 2010). |

| 4 | As in other countries, the exact number of Jains in the United Kingdom is unknown. Paul Dundas estimates 25,000–30,000 (Dundas 2002, p. 271), whereas P.C. Jain speaks of 50,000 (Jain 2011, p. 96). As most of my UK respondents thought 30,000 was correct, I will assume P.C. Jain’s figure to be unrealistically high. The first Jain temple was opened in Leicester, but today, most UK Jains live in the Greater London area. |

| 5 | Respondents in London estimated that as many as 80% of Jains living in the United Kingdom have an East African background, meaning that they or their parents were settled in East Africa (mainly Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda) before they came to the United Kingdom in the 1960s. For more about South Asian migration to Africa, see (Oonk 2007, 2013, 2015; Alpers 2013). For more on Jain migration to Africa and onwards, see Banks 1994. |

| 6 | The exact number of Jains in North America is unknown. Estimates vary from 45,000+ (Dundas 2002, p. 271), over 50,000 (Jain 1998, p. 295) and 60,000 (Kumar 1996, pp. 103–12), to 150,000 (Jain 2011, p. 99). Some respondents estimated the numbers to be significantly higher still. Most large cities in the United States have an active Jain center. The largest Jain populations are found in New Jersey, California, and New York in the United States and Ontario (Toronto) in Canada (Jain 2011, p. 99; Kumar 1996, pp. 104–5). |

| 7 | Of this large number of hits, the majority only mention Jainism in passing. The number of websites that devote a significant amount of attention to Jainism is much smaller. |

| 8 | For the purposes of this research, a website was deemed findable if it was included in Google search results to a simple query, or hyper-linked to by a website that was included in such search results. In the first phase of corpus compilation, I used Google.com as a search engine, within the Mozilla Firefox browser (the latest of which using version 52.5.2). I successively entered ‘Jain’, ‘Jainism’, ‘जैन धर्म’ (Hindi), and ‘જૈન ધર્મ’ (Gujarati) as search terms. Although I discounted websites that did not relate to Jainism in any meaningful way (for example, those that just had the word ‘Jainism’ in a list of South Asian religions), I did include both websites identifying as Jain, and websites containing information about Jainism. I did not limit my search to websites developed by Jain migrants, or indeed Jains. In a second phase of corpus compilation, I opened the first-tier websites and listed all hyperlinks and references. These were all, irrespective of their content, included in the corpus. This second tier functions as a double check for any important sites that may not have featured in the first tier of Google search results, and also allows me to identify important themes and (formal or informal) alliances with non-Jain organizations. For example, the large number of websites dealing with animal welfare or vegetarian and vegan lifestyles in this second tier of data gives some indication that these topics are important to the Jains. The findability of a website is not a fixed value. Rapid updates of Google’s search and ranking algorithms and the constant development of new websites result in a constant flux in ranking and findability, with some websites disappearing from the search results of a general query, even though they do still exist. |

| 9 | PageRank is the algorithm based on incoming hyperlinks that Google pioneered as a means of assessing the quality of a website. |

| 10 | In the case of many European and North American communities, the use of English allows for equal access to the Gujarati speaking majority and Hindi, Bengali, or Kannada speaking individuals living in the area. In addition to this, being understandable to the broader community in the country of residence can be a legal (in the case of charity status) or social requirement. However, in many Jain organizations in the diaspora, the de facto working language at meetings, lectures, and events is most often Gujarati. |

| 11 | Jainpedia.org is an online encyclopaedia project by the London-based Institute of Jainology and Prof. Nalini Balbir (Sorbonne, Paris). |

| 12 | Jainworld.com was started in 1996 by one individual who felt compelled to develop a website to make information on Jainism accessible online when he had moved to the Middle East with his family. The developer has since moved to the United States and the website is now maintained from Atlanta. It brings together vast amounts of information on most Jainism-related topics and, because of an elaborate translation project, is clearly trying to reach both Jain and non-Jain audiences. |

| 13 | The Jain e-library website, jainlibrary.org, is designed and maintained in India, but the organization behind this project is Jain Education International of Pravin K. Shah, who is also the current chairperson of JAINA’s Education Committee. It provides downloadable versions of a very broad range of Jainism-related books and publications. |

| 14 | Paras TV is an Indian television channel dedicated to Jainism and related topics. It can be watched online via a live stream (Paras TV 2019), or using the Paras TV App (Tanuj 2014). |

| 15 | A Samaṇī is a female intermediate level novice ascetic in the Śvetāmbar Terāpanth sect of Jainism. These ‘half-initiated ascetics’ take most of the vows full ascetics take, but do not have to lead a peripatetic life, and are allowed to travel, handle money, and provide their own food if necessary. This enables them to study at universities, visit Jain communities in the diaspora, and so on. They have centers in London (United Kingdom), Houston (TX, United States), Iselin (NJ, United States), and Orlando (FL, United States), where they give classes and lectures regularly. When invited, they also visit other Jain communities. |

| 16 | In the United Kingdom, people like Vinod Kapashi, Natubhai Shah, and Harshad Sanghrajka all hold PhDs in Jainism and are widely considered to be specialists. In Belgium, Amit Bhansali, who holds a PhD on Jainism from the University of Tilburg in the Netherlands, regularly leads svādhyāys. |

| 17 | Dhirubhai Mehta is based in Surat. He visited the Jain Center of Northern California in 2015, and the JCCA in Antwerp in 2018. See also (Dhirajlal 2018). |

| 18 | Tarlaben Doshi is based in Mumbai, but has visited Jain centers in all three of our field sites over the past years to give lecture on Jainism. She visited the Jain Society of Metropolitan Washington for Paryuṣaṇ in 2018. |

| 19 | It deserves mention that ‘Internet’ here refers exclusively to the practice of looking for doctrinal information presented on websites like Wikipedia, Jainpedia, Jainworld, and so on. As every respondent involved in teaching (samaṇīs, pandits, scholars, and volunteer teachers) said they used the internet to find illustrative materials for their classes and most also conceded they used the internet to access materials, for example, by downloading books from Jainlibrary.org, these practices are not included in this analysis. |

| 20 | This includes narratives emphasizing applied ethics, devotional practices, philosophy, and different sectarian narratives. The discourse on many of the diasporic organizational websites seems to emphasize unity across the main Jain groups, often by prioritizing shared customs over differences in historical and doctrinal understandings. However, as the vast majority of Jains in the diaspora belong to the Śvetāmbar Mūrtipūjak group, preliminary analysis indicates that even in discourses that, on the face of it, promote a unified Jainism, Śvetāmbar Mūrtipūjak interpretations are more common. Some websites in the diaspora, and a large number of the websites hosted in India, are more vocal about their sectarian allegiance. Whereas this article does not delve into the narratives present on diasporic and other websites, this will be the subject of future research. |

| 21 | The public Facebook page of the Jain Cultural Centre Antwerp is maintained by one of the committee members and provides pictures and reports on past activities. Only rarely is it used to announce activities. |

| 22 | Whereas the population density around Harrow and Kingsbury is such that new arrivals will find it much easier to find out about the existence of the local Jain organizations by word of mouth, the right communication strategy will impact their choice from the cornucopia of organizations and activities. |

| 23 | Apart from the Jain Cultural Centre Antwerp (JCCA), only one Jain organization is active in Antwerp—the Srimad Rajchandra Mission Centre Antwerp. This is a branch of the guru-led Srimad Rajchandra Mission Dharampur. |

| Local | Pandits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet19 | Books | Teachers | & Local Scholars | Ascetics | |

| Specialist teachers | |||||

| Samaṇīs | x | xx | |||

| Pandit | xx | x | |||

| Scholar | xx | x | |||

| Volunteer teachers | |||||

| Teacher US | x | x | xx | x | |

| Teacher UK | x | x | xx | ||

| Teacher BE | x | xx | x | ||

| Regular Jains (Non-teachers) | |||||

| Jain US | xx | x | x | xx | x |

| Jain UK | x | x | x | xx | x |

| Jain BE | x | x | x | xx | xx |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vekemans, T. Roots, Routes, and Routers: Social and Digital Dynamics in the Jain Diaspora. Religions 2019, 10, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10040252

Vekemans T. Roots, Routes, and Routers: Social and Digital Dynamics in the Jain Diaspora. Religions. 2019; 10(4):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10040252

Chicago/Turabian StyleVekemans, Tine. 2019. "Roots, Routes, and Routers: Social and Digital Dynamics in the Jain Diaspora" Religions 10, no. 4: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10040252

APA StyleVekemans, T. (2019). Roots, Routes, and Routers: Social and Digital Dynamics in the Jain Diaspora. Religions, 10(4), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10040252