Abstract

Although Jainism has been largely absent from discourses in bioethics and religion, its rich account of life, nonviolence, and contextual ethical response has much to offer the discussion within and beyond the Jain community. In this essay, I explore three possible reasons for this discursive absence, followed by an analysis of medical treatment in the Jain tradition—from rare accommodations in canonical texts to increasing acceptance in the post-canonical period, up to the present. I argue that the nonviolent restraint required by the ideal of ahiṃsā is accompanied by applied tools of carefulness (apramatta) that enable the evolution of medicine. These applied tools are derived from the earliest canonical strata and offer a distinct contribution to current bioethical discourses, demanding a more robust account of: (1) pervasive life forms; (2) desires and aversions that motivate behavior; (3) direct and indirect modes of harm; and (4) efforts to reduce harm in one’s given context. I conclude by examining these tools of carefulness briefly in light of contemporary Jain attitudes toward reproductive ethics, such as abortion and in vitro fertilization.

1. Introduction

The ancient Indian tradition of Jainism is notably absent from contemporary discourses in religion and medical bioethics despite its historical emphasis on ethical action, its exhaustive account of life forms, and its rich history of medicine from antiquity to the present. In this article, I describe three areas of ethical resonance between Jainism and medical bioethics, and three possible reasons for the lack of Jain engagement with this emerging field. In light of this gap, I analyze the under-examined canonical concept of “carefulness” that contributed to the gradual development of Jain medicine, a concept that might also function today as an applied Jain ethical framework. An ethics of carefulness, I argue, aims toward the Jain ideal of ahiṃsā, or nonviolent restraint, while offering four distinct applied tools for bioethical discourses and decision-making for Jains and non-Jains alike. Drawing upon portions of my forthcoming co-authored book Insistent Life: Foundations for Bioethics in Jainism (Donaldson and Bajželj 2019), I conclude by examining a small portion of a survey we conducted with international Jain medical professionals regarding their views on contemporary bioethical issues. I explore survey attitudes toward reproductive dilemmas in abortion and in vitro fertilization in order to evaluate how an “ethics of carefulness” might function in future discourses between Jainism and bioethics.

2. Bioethics and Religion

Bioethics began as a formal discipline in the U.S. in the late 1960s and early 70s, and was pivotally shaped by Judeo-Christian religious ideals from its inception. Protestant Paul Ramsey, Catholic theologian Richard McCormick, and Jewish theologian Immanuel Jakobovits were but a few of the visible figures who applied their respective traditions’ insights on life, death, suffering, and justice, to craft an interdisciplinary field grappling with moral issues in medicine. These issues included establishing informed consent guidelines after several research violations came to light, such as the 40-year Tuskegee syphilis experiment on African American sharecroppers in which researchers failed to provide penicillin to participants after it became a known curative in the 1940s, continuing the study until 1972. Additionally, life sustaining technology, such as the positive pressure ventilator, created new dilemmas surrounding the definition of death and generated questions of resource allocation. For example, is it ethical to spend one million healthcare dollars on life support for a single newborn, or to utilize those funds to immunize an entire neighborhood of children? Religious ethicists were key members of early governmental policy committees that issued federal reports and guidelines for human research subjects, foregoing life-sustaining treatment, health care access, and the definition of death.1 Religious authors wrote academic literature2 and helped initiate organizations that would later become the Kennedy Institute of Ethics at Georgetown University and the Hastings Center in New York.

Non-western traditions began to engage the field of western bioethics in the 1990s. The Dalai Lama was a key figure in opening dialog between Buddhist philosophy of mind and western scientists in a series of publicized conversations beginning in 1989. Many books exist today on Buddhist social or ecological ethics but only a few address bioethics, such as Damien Keown’s Buddhism and Bioethics (1995) or Peter Harvey’s Buddhist Ethics (2000). Likewise, Hindu bioethics has modest representation with two notable titles: Cromwell Crawford’s Hindu Bioethics (2003) and Swasti Bhattacarya’s Magical Progeny, Modern Technology (2006), examining Hindu views of reproduction.

There are no books specifically exploring Jain philosophy in relation to western medical bioethics, leaving a gap in both bioethics and religion, as well as Jain studies. Substantive writings exist on Jain ethics, generally (Bhargava 1968; Williams 1991; Sethia 2004), as well as Jain ecology (Chapple 2002; Rankin 2018; Jain 2010), but bioethics is treated minimally in only a few academic articles, chapters, and online reflections by Jain practitioners.

A Gap in the Field: A Lack of Jain Engagement in Medical Bioethics

The absence of a comparative text on Jainism and medical bioethics is notable since Jainism shares three distinct points of resonance with the field. The first point of resonance is that Jainism emerged from a community centered on ethical practice. Jains consider their tradition to be eternal. There is no founder, but a series of 24 Tīrthaṅkaras, meaning teachers who made a tīrtha, or pathway, across the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, known as saṃsāra.3 The last two of these teachers are historical persons who oversaw a fourfold community of monks and nuns (or “mendicants”), as well as lay men and lay women: the 23rd teacher Pārśvanātha lived approximately in the 9th century BCE, and the 24th and last teacher of this time cycle, Mahāvīra, lived in the 5th–6th century BCE.4

Mahāvīra was an elder contemporary of the Buddha. What we now call Jainism and Buddhism emerged from the influence of non-Vedic renunciate groups in the Ganges plain known as śramaṇa, meaning “to strive or exert,” referring to those communities who believed that rigorous action and ethical restraints—rather than Vedic ritual or sacrifice—provided a means to liberation that was open to all.

Mahāvīra centered his community on five vows: non-harm (ahiṃsā), followed by truthfulness (satya), taking only what is given freely, referring especially to food for mendicants (asteya), celibacy (brahmacarya), and the non-accumulation of goods (aparigraha). Mendicants takes these five vows fully as “great vows” (mahā-vratas) during an initiation that publicly signifies their rebirth into houseless existence, while lay Jains fulfil them partially as “small vows” (aṇu-vratas) in the context of work, family, and home.5 From antiquity to the present, this fourfold community forms a symbiotic relationship. Mendicants offer teaching, guidance, and a living example of the Tīrthaṅkaras for lay Jains who, in turn, take on the karmic cost of preparing food and water and offering temporary shelters to wandering mendicants.

The community eventually divided into two dominants sects due to a few key differences, one of which is the proper clothing for a mendicant, from which the sect names derive. The larger group, the Śvetāmbara, refers to “white clad” mendicants, and the smaller Digambara, or “sky clad” sect, believes mendicants must be nude for complete non-attachment. In spite of these differences, Jains remain strongly united on the ethical primacy of ahiṃsā, or non-harm.

The second point of resonance is that Jainism offers one of the most detailed accounts of living beings among all global worldviews. The Jain universe (loka) is populated by infinite beings existing in a cycle of birth, death, and rebirth who are categorized by the number of senses with which they experience the world, from one through five. Plants and microorganisms in earth, air, fire, water, and wind possess the single sense of touch. Two-, three-, and four-sensed beings including mollusks, worms, spiders, moths, etc. have the additional senses of taste, smell, and sight, respectively, while five-sense beings who possess hearing include mammals, birds, fish, humans, as well as divine and infernal beings (TS 2.8–2.25). The Jain worldview has no transcendent deity. Rather, every living being possesses its own core life force, called jīva, an eternal substance characterized by changing qualities of consciousness (upayoga; with two aspects of pure knowledge and pure perception), energy (vīrya), and bliss (ānanda). Every jīva is inter-dependently supported by a matrix of five non-living substances called ajīva: medium of rest, medium of motion, space, time, and matter (TS 5.1–5.2).

In the Jain biosphere, every embodied being is subject to four instincts of food, competition, reproduction, and the need to accumulate resources, and these instincts cause unavoidable harm to other beings and minute organisms (Jaini 2010, p. 284). Each action attracts karma, which in Jain philosophy is uniquely described as a subtle form of matter (pudgala) that clings to the jīva, obscuring its qualities, resulting in deluded understanding, inevitable injury to self and others, and repeated, lower rebirths.

Ahiṃsā, often translated as nonviolence, is the core principle to stop the inflow of karma from the jīva and clean it away. In Sanskrit, hiṃsā is a desiderative verb meaning a strong desire to hit or strike other living beings. The negation—ahiṃsā—is the absence, even of desire, to harm others. This serious commitment to restrain desires is exemplified in the five vows and the visible iconic practices of Jain mendicants who forego possessions, walk barefoot, cover their mouth when speaking, eat once daily vegetarian food without root vegetables that have a higher karmic cost, avoid all means of transit, and sweep the ground clear before sitting, sleeping, or walking, offering an unparalleled concern for life from which to engage critical questions in bioethics.

The third point of resonance stems from Jainism’s long-standing tradition of medicine from late antiquity to the modern day, a complex history I will revisit shortly. Given these intersections, what explains the lack of Jain engagement with contemporary bioethics? I propose four possibilities.

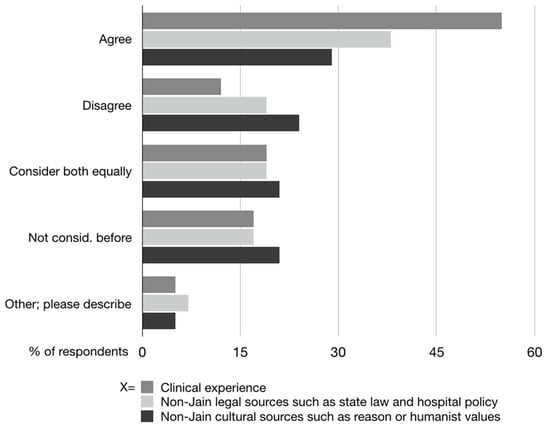

The first reason why Jains may not have engaged modern bioethics is that the ancient philosophy and worldview of Jainism simply does not affect modern Jains’ approach to bioethics. For example, Jains who have undergone secular medical or scientific training, or who have lived much of their professional life outside India, may not feel that their cultural Jain identity has much bearing on the clinical or epistemic frameworks within which they practice medicine or healthcare. However, the present essay—as well as the larger research project and manuscript from which it derives—has been motivated by evidence that Jains are reflecting on modern bioethics. These trends include two international conferences addressing the theme of Jainism and bioethics (in 2012 and 2017)6, active global events exploring Jainism and science7, the development of Jain-created guidelines for hospital staff in the U.S. and U.K. who encounter Jain patients8, a successful political campaign among global Jains to reverse the Indian Supreme Court’s decision banning the Jain end-of-life fast known as sallekhanā or saṃthāra (SC Stays Rajasthan [High Court] Verdict Declaring Santhara Illegal 2016), and a nascent selection of Jain-created responses to bioethical issues which we integrate into our forthcoming book. We also found meaningful disconnects and overlap between Jainism and modern medicine, expressed in the survey. On one hand, Jain medical professionals report utilizing multiple knowledge sources to inform their understanding of ethical challenges in healthcare. Many respondents claimed to be considerably more informed by clinical experience than by Jain sources, and equally or more informed by non-Jain legal sources and non-Jain cultural sources than by Jain sources (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survey question: “X informs my understanding of medicine/healthcare more than Jain sources” (n = 42). This graph is a composite of three questions. (1) “Clinical experience informs my understanding of medicine/healthcare more than Jain sources”; (2) “non-Jain legal sources such as state law and hospital policy inform my understanding of medicine/healthcare more than Jain sources”; and (3) “non-Jain legal sources such as state law and hospital policy inform my understanding of medicine/healthcare more than Jain sources”.

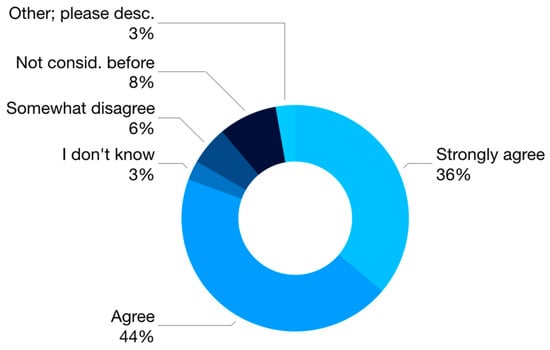

At the same time, the majority of respondents agreed (44%, n = 35) or strongly agreed (36%) that the Jain vow of nonviolence shaped their professional decision-making in a healthcare context (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survey question: “I feel that the Jain vow of nonviolence has influenced my professional decision-making in a medical/healthcare context” (n = 35).

These questions are just two among several that we summarize in Insistent Life to get a sense of the complex relationship between Jains professionals and Jain philosophy as it applies to their medical and healthcare outlook.

The second reason for the lack of engagement between Jainism and bioethics is methodological. Jainism, like all South Asian philosophical traditions, bears the colonial designation of being the “mystic east.” Richard King, in his book Orientalism and Religion (1999), describes the impact of orientalist portrayals of India as the “mystic east,” resulting in the marginalization of its philosophical traditions, largely excising them from the history of philosophy, which now begins with the Greeks. Western philosophy is constructed as the pursuit of rational knowledge, public verifiable processes, aimed at universal principles. This construction takes places over and against the mystical, or transcendent belief of the East, whose knowledge is private and esoteric, always bound to specific geography and culture (King 1999, pp. 27–28).

Though this intellectual history has been actively challenged, the split between religion and philosophy is entrenched in western knowledge regimes, such that Indian traditions are often relegated to religion departments or interfaith dialogues, where centuries of Vedic and non-Vedic debates over fundamental questions in philosophy are avoided entirely, to fit them into comparative religious models suited to monotheist worldviews. In his work on religion and public ethics, sociologist John Evans (2006, p. 62) asks, “Who Legitimately Speaks for Religion in Public Bioethics?” Evans describes three possible such speakers: Theologians, in which he includes scholars of religion, members or “people in the pews,” and religious “authorities” This common framing marginalizes South Asian views that have no concept of Theos, or transcendent God, which includes Jainism, Buddhism, the Cārvāka materialists, the Ājīvika determinist school, and functionally, the Vedic systems of Vaiśeṣika concerned with atomism, and Mīmāṃsā centered on linguistics. Additionally, Jainism lacks formal “authorities” akin to ministers or priests who speak for the tradition. Recall that the primary aim of mendicants is to renounce social participation, not explicate it. So “members” or lay Jains—whose temples have no pews—are constrained from contributing to public discourses—including bioethics—by powerful disciplinary frames of philosophy and religion that bifurcate the logic of their worldview.

The third reason I propose for the lack of Jain engagement with bioethics is epistemological. Jains have a long history of adapting to social surroundings as a minority community. Jainism has always been a small community, today 5–7 million people globally, less than 1% of Indian population. Yet, its cultural impact belies its size. Olle Qvarnström attributes the growth of the Jain community during antiquity to strategies he calls “opposition and absorption” (Qvarnström 2000, pp. 117–18). Jains opposed beliefs that undermined fundamental principles while making, what Qvarnström calls, “ideological room” for converts who retained some cultural beliefs and habits (p. 116). In this process, Jainism absorbed regional temple rituals, claimed Vedic figures such as Krishna in Jain narratives, and recast local goddesses with the Jain virtue of nonviolence (pp. 118–21).

Opposition and absorption was expressed philosophically by an early Jain doctrine called anekāntavāda or, “doctrine of multiple-sided views.” Anekāntavāda originates in the infinite valid viewpoints of each individual jīva, and develops into a formal logic to affirm contradictory views and qualities as simultaneously true (Qvarnström 2000, p. 117). In an early canonical text, the Bhagavatī-sūtra, a student asks Mahāvīra, “Are living beings permanent or impermanent?” To which he replies that jīva is permanent in light of its substance, which is eternal, and impermanent in light of its continually changing qualities (BhS 7.2.47–48). Jains used a seven-fold formula to affirm rival views, while also showing their incompleteness, the Jain view being more complete (TS 1.34; Long 2009, pp. 141–54).9 Opposition and absorption sustained the Jain community throughout history, through integrating regional ideals, and securing royal patronage from kings, in order to survive the shifts of empire, whereas Buddhism had virtually disappeared from the subcontinent, by the 11th century CE.

These practices of tolerance permit modern Jains to encounter non-Jain ideas and absorb some or all of them into Jain views. Knut Auckland (2016) describes this as the “scientization and academization” of Jainism, wherein modern Jains claim the tradition’s compatibility with rational institutions and scientific pursuits. I assert that we can likewise consider bioethics part of these modern expressions that Jains see reflected in their ancient ideals, such that there is little need to address the field as something truly “new.”

Finally, the fourth proposed reason for the lack of Jain engagement with bioethics is sociological. A debate persists between scholars of Jain history and Jain diaspora as to what degree contemporary Jains can apply the tradition’s orthodox principles to contemporary ethical issues. On the historical side, Paul Dundas warns that the ahiṃsā ideal of total restraint from civic engagement “...renders [Jainism] an awkward tradition [for] ecological and social renewal” (Dundas 2002, p. 103), while John Cort asserts that focus on ultimate liberation from the embodied world is “not very conducive to the development of a [positive] environmental ethic” (Cort 2002, p. 70). James Laidlaw (1995, p. 153) provocatively describes ahiṃsā as an “ethic of quarantine” opposed to positive advocacy.

On the other side, diaspora scholars provide a more positive picture of Jain social engagement. However, these views often describe “neo-orthodox”10 trends among modern Jains to recast the tradition for their own secular and scientific contexts (Banks 1991), to (re)construct an individual Jain identity suited to modernity (Shah 2014), or to reinterpret canonical goals “away from a traditional orthodox liberation-centric ethos to a sociocentric or ‘ecological’ one” (Vallely 2002, p. 193). Neither the historical/orthodox nor the diaspora/neo-orthodox analysis has identified an applied framework that one can firmly trace from the early canon to the present to engage medical bioethics while staying connected to mendicant roots.

I argue, however, that the liberalization of Jain medicine does offer an existing precedent—in the form of carefulness—as an applied mode of practice between the orthodox goal of restraint and engaged social participation, to which I will now turn.

3. Rare Accommodations for Medicine in the Early Canon through Practices of Carefulness

The early canon has a negative view of medical care. The “canon” I am referring to includes 45 Jain texts written in Ardhamāghadhī Prākrit beginning around the third-century BCE. This list of 45 was redacted and fixed at the Council of Valabhī in the 5th-century CE11, and is considered “canonical” by the larger Śvetāmbara sect of Jains, who accept most or all of this list. Digambaras consider these teachings lost and identify a different later set of texts.

The earliest canonical texts are manuals of conduct for mendicants. Medicine is forbidden because: (1) it eradicates microorganisms that cause disease; and (2) many mammals, insects, yeasts, and bacteria are destroyed to produce the medicine itself, including common curatives of meat, honey, and alcohol (Stuart 2014, p. 70). Medicine also represents a damaging attachment to the body, such that a doctor is described in the earliest text, the Ācārāṅga-sūtra, as “appearing wise” (paṇḍita-māni), while actually being bound to the pleasures of the body, “profess[ing] to cure ...while he kills, cuts, strikes, destroys, [and] chases away [life]” (ĀS I.2.5.6). Mahāvīra exemplifies the ahiṃsā ideal of restraining activity, desires, and attachments throughout these early teaching manuals. For example, he eats little, fasts often, bears extreme temperatures, tolerates attacks by insects, animals, and people, and accepts disease, injury, aging, and ultimately death without seeking medical care (ĀS I.8.3.1–13). The Niśītha-sūtra (3rd–1st cent. BCE) prohibits monks from washing or cutting into a wound which would destroy skin microorganisms (Stuart 2014, p. 70). Disease is considered one of “22 troubles” that monks should bear (US 2.1), while mature mendicants should not seek food when ill, nor bathe, brush teeth, or protect themselves from sun (SKS 2.2.73). Medical literature (cikitsā-śruta), such as āyurveda, is described as false teaching (Sth 9.27), and medical treatment (3.4) and medicines (3.9) are listed among the fifty-two things that are unacceptable for a devout mendicant.

Those few scholars who look at mendicant medicine emphasize its prohibition in the early Jain canon, due to the strict interpretation of ahiṃsā. Twentieth-century scholar S. B. Deo, as well as contemporary scholar Mari Jyväsjärvi Stuart, both locate the acceptance of medicine in the post-canonical commentaries (bhāṣya), approximately after the 6th-century CE (Deo 1954, pp. 29–33; Stuart 2014, pp. 66–67).12 Phyllis Granoff, although citing one canonical example of Mahāvīra taking medicine in the canonical Bhagavatī-sūtra (BhS 15.393–394), primarily explores the curative practices in later medieval story literature (Granoff 1998a, p. 222). Kenneth Zysk, in his two-volume analysis of medicine in Buddhist monasticism, states that Jain mendicants clearly had knowledge of illness and medical treatments, but “because of the severity of their ascetic discipline ...Jainas did not codify medicine in their monastic texts” (Zysk 1998, p. 38).

While a system of codified medicine is not found in the Jain canon, early canonical texts do include rare examples in which medicine is allowed, challenging an interpretation of pure prohibition. The Uttarādhyayana-sūtra, for instance, said to contain portions of Mahāvīra’s last sermon, describes a “true monk” as one who foregoes medical care (US 15.8), bears disease (21.18), and “should not long for medical treatment ...[but] search for the welfare of his soul (2.33). Yet, the same text implicitly recognizes that not all monks are capable of this level of restrained ahiṃsā, stating that a monk cannot practice the vows if sick (11.3), that mendicants should share their food with fellow monks who are ill (15.12), and are permitted to seek food to treat their own illness if needed (26.33). Another canonical texts instructs monks to “carefully attend [to] a sick brother” (SKS 1.3.3.20), while another commends mendicants to “neither be pleased with nor prohibit” therapeutic activities that another person may offer to them, including treating sore feet and joints, removing splinters, washing wounds, cutting an abscess, removing lice, or bathing (ĀS II.13). A sick monk may vow to accept medical help from fellow mendicants who offer it freely, and to help others who are sick without being asked; others may vow not to give or receive aid when sick; both vows are acceptable, so long as one strives to fulfill the particular vow they make (ĀS I.7.5.2–4). These practices are permitted for a diverse community of monks—whose ahiṃsā restraints are of the “low, high, and highest degree” (ĀS I.4.4.1)—who yet retain membership in the community so long as they remain oriented toward the ahiṃsā ideal through practices of “carefulness.”

Four Tools of Carefulness

Carefulness (Skt: apramatta; Pkt: apammate) is a frequent, under-theorized term found in canonical texts that provides a path of applied practice for mendicants who fall short of the ahiṃsā ideal. For this essay, I am primarily using examples from the earliest canonical text, the Ācārāṅga-sūtra.

Carefulness is juxtaposed with its opposite—carelessness (Skt: pramatta; Pkt: pamatte)—the common failing attributed to monks who have lost sight of ahiṃsā. Pramatta is a past passive participle from the Sanskrit root mad, which means careless, heedless, negligent, inattentive, forgetful, etc. As Mahāvīra states, “Those who are careless (Pkt: pamatte) are outside [religion]; if careful (apamatte), one will always conquer” (ĀS I.4.1.3). At the same time, “Those who are afflicted and careless (pamattā) will be instructed” (ĀS I.4.2.2), and one assumes, not cast out. Canonical texts repeatedly describe distinct practices of carefulness by which one strives toward the ahiṃsā ideal. From these repeated practices, I deduce four “tools of carefulness” that shape canonical accommodations of medicine and its later post-canonical acceptance. These four tools offer a framework of applied ethics that can be traced from the earliest canon up to the present, enabling a distinctly Jain approach to bioethical engagement.

Tool 1: Carefulness requires right worldview of karmic entanglement with infinite living beings, visible and invisible, who, as the Ācārāṅga-sūtra states, are “fond of life, hate pain, …[and] long to live” (ĀS I.2.3.4). There is no empty space in the Jain universe and no population that is naturally killable without cost to self and others. As the text cautions, “[One] should never be careless (Pkt: ṇa u pamāye), knowing pain and pleasure in their various forms” (ĀS I.5.2.2). A careless mendicant forgets the multiplicity of lives and fails to consider their desire to live. One who is careful anticipates both.

Tool 2: Carefulness is enacted through control of three means of mind (mano-gupti), speech (vāg-gupti), and body (kāya-gupti). This karmically-damaging trio appears throughout canonical texts as an exhortation for mendicants to identify mental desires and aversions that drive behavior, one-sided speech, and physical actions oblivious to effects on jīvas.13 Neglecting the three guptis results in the rise of (kaṣāyas) of anger, ego, deceit, and greed, distancing one further from the ahiṃsā ideal.

Tool 3: Carefulness is employed through three methods. Directly doing (kṛta), indirectly causing others to do (kārita), or approving of others doing (anumodana). These three methods recur ubiquitously in canonical texts, as in the Sūtrakṛtānga-sūtra: “If [one] kills living beings, or causes others to kill them, or consents to their killing them, [their] iniquity will go on increasing” (SKS 1.1.1.3).14

Tool 4: Carefulness requires continuous efforts to increase awareness and reduce harm. Even disciplined mendicants may harm living beings. If this happens, the early canon states that the person will receive the karmic cost only in this lifetime rather than the future; but if the act was due to carelessness, “he should repent of it and do penance...[One] who knows the sacred [teaching], recommends penance combined with carefulness” (Pkt: appamāeṇa) (ĀS I.5.4.3).15

4. The Acceptance of Medicine in the Post-Canonical Period if Done Carefully

By the post-canonical period carelessness is formalized as synonymous with violence. The author Umāsvāti states in the Tattvārtha-sūtra, a 2nd–5th century CE text considered authoritative by all Jain sects, that “taking life away out of careless action [pramatta-yogāt] is violence” (TS 7.8). His Digambara contemporary Kundakunda asserts in the Pravacanasāra, “Careless [Skt: pramāda] action ... is the cause of hiṃsā to the [mendicant]” (PS 3.16).

This formal link between violence and carelessness enables a liberalization in Jain medicine that scholars do note, wherein medicine, if it is done carefully, is no longer equated with violence. Stuart attributes the liberalization to Jain mendicants needing to compete with rival groups for members, and the need to keep the lay community satisfied by producing monks and nuns healthy enough to perform austerities (Stuart 2014, pp. 66–67). Granoff (1998b, pp. 286–87) attributes the liberalization to a shifting view of disease from a natural effect of karma that must be lived out to certain diseases being amenable to treatment. In addition to these various reasons, I suggest the acceptance of medicine evolves from an accommodation already present in the early canon through carefulness.

Consequently, the 6th-century CE commentary Bṛhatkalpa-bhāṣya attributed to the Śvetāmbara author Saṅghadāsa, describes eight kinds of doctors of whom two are Jain mendicants (Stuart 2014, p. 82). Monks and nuns can seek a lay Jain physician for free care (Granoff 2013, pp. 232–35) and ordain a person with a “third-sex” gender (paṇḍaka)—who was previously prohibited taking vows—if that person was a doctor (Stuart 2014, p. 83). Jains also began writing their own āyurvedic medical texts, although only two of these are surviving: the Tandulaveyāliya (post-7th-cent. CE; “Reflection on Rice Grains”)16 and the 9th-century Kalyāṇakāraka (“What Brings Goodness”) by the Digambara sage Ugrāditya. The latter describes physicians as “great healers” (uttamā bhiṣak) (Patil et al. 2015, p. 145) and lists several Jain medical sages (Jain 1950, p. 129). These manuals are in conversation with the classical āyurvedic treatises, such as the Caraka- and Suśruta-saṃhitās, but add their own Jain twist by removing three forbidden foods (vikṛti) of honey, alcohol, and meat from the accepted list of medicines, a change that percolates into the wider āyurvedic tradition. In the centuries following, Hemacandra, the 11th-century Śvetāmbara scholar, claimed that the touch and bodily fluids of a Jain monk could function as medicine (YŚ i.8) and that carefully cutting flesh (chavi-cheda) to treat an ailment was acceptable, though mutilating prisoners, enemies, trees, animals or minute organisms was still a violation, (YŚ iii.90, iii.114; Williams 1991, p. 68).

Similar accommodations exist outside the medicine wherein a lay Jain can tie a rope to a bull with care and not commit the violation of keeping captive, or instruct one’s immediate family to restrain or castrate animals if essential for a layman’s duty and not commit a violation of beating or cutting (YŚ iii.76). Such actions still result in harm, but if done with care, they do not accrue the same negative karma to oneself. Śvetāmbara texts from the 14th century onwards list medicine as one of the seven acceptable lay occupations (upāyas), although Digambars do not include medicine on their list (Williams 1991, pp. 121–22).17

Formal practices of carefulness apply differently to mendicants and lay Jains. Mendicants, undertake eleven more rules of carefulness to make their vows concrete in their context. Five rules (samiti18) ensure attention in walking, speaking, drinking/eating, moving objects, and excreting when other jīvas may be affected. Six obligatory practices (āvaśyaka) sharpen perception through meditation, repentance, and fasting, among other activities. Lay Jains have seven optional rules of carefulness—three guṇa-vratas and four śikṣa-vratas—to avoid social and occupational excesses, to feed mendicants with the lowest karmic cost, and other disciplines of study, meditation, or fasting from food, purchasing, or speaking for a set time (Williams 1991, pp. 55–172).

Mendicants avoid harm even toward invisible one-sense life forms (sūkṣma-hiṃsā), explaining the visible mendicant austerities mentioned earlier, while lay Jains are obligated to forego violence toward visible insects, birds, and mammals with two or more senses who can be seen with attention (sthūla-hiṃsā) (Williams 1991, pp. 65–66).

The 10th-century text on Jain karma, the Gommaṭasāra Jīvakāṇḍa by the Digambara philosopher Nemicandra, describes fourteen stages of karmic progression (guṇasthānas) in light of carefulness. Jīvas in the first stage—of any kind of organism—are cloaked with heavy karma, wrong view of reality (mithyā-darśana), and uncontrolled desires that harm self and others. The fourth stage signifies the attainment of right worldview (samyak-darśana); while one can still slide back into delusion after reaching this stage, liberation is guaranteed at some future time. In the fifth stage, lay people can take the small, partial vows, which is the highest stage a lay person can achieve. In the sixth stage, mendicants take the great vows but adhere to them carelessly, called the “carelessness stage” (pramatta-virata); in the seventh stage, mendicants observe the vows carefully—apramatta-virata (Wiley 2009, pp. 243–44; Glasenapp 1942, p. 68), enabling them to continue on toward the ultimate goal of shedding all karma, and eventual liberation, or mokṣa, in the fourteenth stage, though this may take hundreds of thousands of lifetimes.19

Carefulness versus “Intention”

These views of carefulness may lead one to assume that if the intention is to heal or make a living, then any act is permissible. But carefulness is distinct from intention (Pāli and Skt: cetanā), a common Buddhist notion that medieval Jain philosophers rejected as heretical. Granoff (1992, pp. 33–34) describes the Śvetāmbara monk Śīlaṅka’s (9th century CE) response to the following Buddhist argument: if someone mistakenly kills a baby thinking it is a gourd, Buddhists claim that one is not responsible for the death since that person did not mentally intend to kill. Śīlaṅka argues that intention must be matched with knowledge and behavior; ignorance does not excuse violence (34). Likewise, Haribhadra (7th–8th century CE) asserts in his commentary on the lay manual Śrāvaka-prajñāpti20, that “Violence is unmindfulness,” such that right action requires vigorous and active pursuit of knowledge (30). As Granoff summarizes:

The Jains argue ...that it is not possible for a person to be so ignorant and yet not guilty. His very ignorance and carelessness constitute an intent to do violence and imply correspondently his guilt. Only the Jain holy man, who has the right understanding and who is ever mindful of his acts, is truly devoid of the intention to commit violence.(Granoff 1992, p. 32)

In spite of these different interpretations, carefulness is also an important concept in Buddhism (Pāli: appamāda). Some sources say that Buddha’s final words to his community on his deathbed contained an appeal to carefulness, “...[D]ecay is inherent in all things; strive on with heedfulness (appamādena)” (Buswell and Lopez 2014, p. 660). The Buddha is also recorded saying that appamāda, or carefulness, is the only thing attainable in this world that would have value in the next (Saddhatissa 1997, p. 109). The Buddhist concept of carefulness appears to reflect the tradition’s emphasis on the role of mental intention in action, whereas the Jain concept of carefulness emerges from the ongoing pursuit of knowledge of jīva, karma, and other living beings, which is ultimately expressed in right physical action.

In sum, the Jain view of carefulness—apramatta—requires applied tools beyond mere mental intention that keep one concretely oriented toward ahiṃsā, even if imperfectly practiced: (1) right view of living beings through multiple viewpoints; (2) an analysis of desires and aversions that motivate mind, speech, and bodily action; (3) attention to direct and indirect harms; and (4) an attempt to minimize harm within one’s given context. If harms occur within this disciplined sphere of carefulness, it accrues much less, or no, negative karma.

5. Reproductive Bioethics and a Jain Ethics of Carefulness

Today, Jains are firmly entrenched in modern medicine. Though less than 1% of the Indian population, the National Health Portal of India lists over 200 Jain-sponsored hospitals and clinics in India.21 There are at least 25 Jain medical colleges, and the Jain Medical Doctors Association of India has a partial directory of 20,000 Jain physicians. Jain medical professionals are also a visible part of the global diaspora. For instance, many Jains came to the United States through the 1965 Immigration Act, which favored those with advanced training in science, engineering, and medicine, so U.S. Jains—an estimated 100,000 live in the U.S.—have high representation in medical fields. As part of the research for our book Insistent Life: Foundations for Bioethics in Jainism (Donaldson and Bajželj 2019), in 2017, my co-author Ana Bajželj and I designed and conducted an online survey of Jain medical professionals, including medical residents, emergency surgeons, and pharmacists, among many others. The survey included one hundred and thirty multiple-choice and open-ended questions, with responses from 35–48 individuals per question. The gender breakdown was female (40%) and male (60%), and participants’ ages extended from the 18–23 year range (8%, n = 48) to the 80–89 year range (4%), with respondents in every decade in between. The survey reveals a community of medical professionals bound both to Jain values—which we gauged through a series of questions related to Jain education, temple involvement, and community leadership—and secular medical principles—which we gauged through questions exploring sources of authority. Although a majority of respondents were born in India (58%, n = 48), most were presently living outside the subcontinent (92%) without access to mendicant guidance.

In this section, I will explore a sampling of Jain attitudes toward reproductive ethics in light of the above analysis of carefulness. While these findings cannot be generalized to the Jain community at large, nor are the findings compared to other religious groups, they do present the first systematic attempt to identify views that Jain medical and healthcare professionals hold regarding contemporary bioethical issues, such as abortion and in vitro fertilization. These views provide a foundational starting point to evaluate how the Jain tradition might contribute to modern discourses between religion and bioethics, through the lens of a Jain “ethics of carefulness.” Readers are invited to explore the full research when it is published in the Insistent Life manuscript in late 2019.

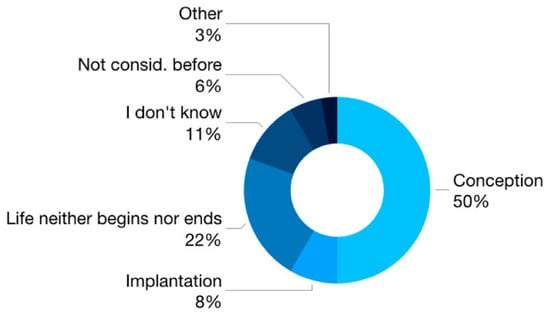

In keeping with the Jain concept of rebirth, a significant minority of respondents felt that life did not begin or end (22%, n = 36), while others privileged positions of philosophical bioethics that place the beginning of life at conception (50%), or implantation (8%) (Figure 3). No participants selected quickening (fetal movement) or viability (when the fetus can survive outside the womb with support). There is also a degree of ambivalence (17%), suggesting that the question of beginning is not all important to ethical action in Jainism.

Figure 3.

Survey question: “I believe life begins at” (n = 36).

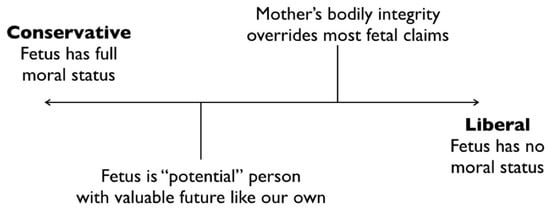

Contemporary bioethics also endeavors to discern the point of legal or moral personhood for fetal life. A simple chart of these contemporary positions might look like as follows (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Modern continuum of fetal moral status.

Unlike this polarity of views, the Jain view of anekāntavāda describes the embryo as having contradictory features simultaneously. In the Bhagavatī-sūtra, a student asks Mahāvīra if “An embryo entering in the womb—is it with or without sense organs?”; he answers, “To some extent (it is) with sense organs [referring to the subjective perception of jīva and an embryo’s single-sense of touch], and to some extent without them [lacking the objective sense organs of eyes, ears, hands, etc.],” (BhS 1.4.241–242). The embryo changes continuously, like all entities, though the jīva is always present, regardless of legal standing or even visibility.

In 2013, the current Bhaṭṭāraka Cārukīrti (bhaṭṭāraka is a title for a small class of celibate clerics in the Digambara tradition of South India) offered a rare interview on bioethical issues including abortion. He states the orthodox view that abortion forces a jīva to be reborn when the goal is to break out of the cycle of rebirth (Sarma 2013). If we know we kill jīvas with each breath, he asks, how can one kill a fetus? He states that thinking about killing brings negative karma, but acting toward abortion and actually doing it, or having someone else do it, invites the worst karmic cost, even if the aim is to save the mother.

Yet the Bhaṭṭāraka does not condemn abortion nor does he describe social or institutional consequences for those involved. Like all actions in a karmic system, if a woman seeks an abortion, she and everyone involved will take the “penalty of karma” as all beings do for the harms they cause (Sarma 2013). The cleric maintains the ahiṃsā ideal of restraint even as he recognizes that lay Jains, and some mendicants, will lack the capacity to pursue that ideal fully in every moment.

The majority of Jain medical professionals in our survey felt that abortion was a form of violence, but, over a third of respondents either disagreed, were unsure, or selected “Other,” providing the following responses beyond mere ahiṃsā restraint.

- “[It] depends on strong medical reason [such as the] mother’s health and her life”

- “[D]epends upon why abortion has to be done”

- “It is [a form of violence], but it needs to be taken on a case by case basis”

- “[I]f you are saving the life of the mother it should be okay. I would rather discourage the need for abortion.”

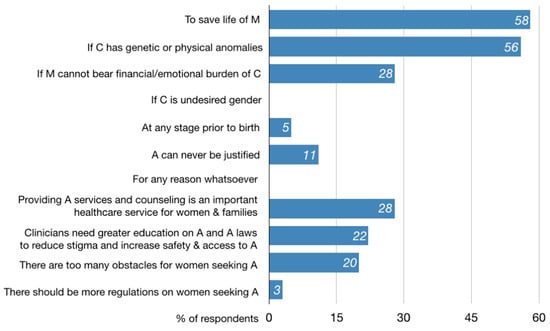

Participants provided greater insight into their views when asked to review a series of statements related to abortion and choose all that apply. Those statements selected by the most respondents were: (1) abortion can be justified only when needed to save the life of the mother (58%, n = 36); (2) if the child may have genetic or physical anomalies that could lead to a life of suffering or early death (56%); or (3) “when a woman feels she cannot emotionally or financially take the burden of another child” (28%) (Figure 5). No respondents felt that abortion could be justified when the child was an undesirable gender (0%), although census numbers show that some Jain communities in India do have gender disparities though usually lower than the surrounding culture, which we discuss in the book. Smaller minorities affirmed that “abortion can be justified at any stage prior to birth” (5%, n = 36), and “abortion can never be justified” (11%). No respondents felt that “abortion can be justified by the mother for any reason whatsoever” (0%).

Figure 5.

Survey question: “Which of the following is most true for you? Choose all that apply”.

At the same time, many respondents felt that “providing abortion services and counseling is an important healthcare service” (28%, n = 36), and that “greater education on abortion and abortion laws among healthcare professionals is needed to reduce stigma and increase safety and accessibility to abortive services” (22%). A similar percentage felt there were too many obstacles for women seeking abortion (20%), while a tiny minority believed “there should be additional regulations” (3%) (Figure 3).

These answers do not explicitly suggest that respondents are overtly employing tools of carefulness, but they are certainly not applying a flat restraint of ahiṃsā. Aspects of each tool of carefulness—reflecting on life forms of mother, clinician, and fetus, as well as mixed motivations, direct/indirect injury, and reducing harm, including future harm—are present in the responses. These responses suggest that the four applied tools of carefulness might provide a formal Jain framework for bioethical discourse, within and beyond the Jain community, which directly connects to the orthodox canon. As bioethicist and theologian Lisa Cahill (2006, p. 37) insists, universal language is not required for the bioethics and religion discourse, since secular society is far from neutral; ideals need only be non-dogmatic. A Jain ethics of carefulness permits Jains to maintain their commitment to karmic causality and to the ideal of ahiṃsā while using four applied tools to ask rigorous philosophical questions relevant to Jains and non-Jains.

The Bhaṭṭāraka also indirectly appeals to the applied tools of carefulness when he states, for example, “The Jain answer is not about killing, dying, birth [or] abortion. It is about understanding the karmic consequences of one’s actions. If you want to [harm] someone and you ask someone else to do it, you are still responsible for the [harm]” (Sarma 2013). He further inquires, if our desire for sex leads us to consider killing a nascent life, or having someone else kill for us, might be a different desire that lead us to kill a person or an animal? These questions reveal how an ethics of carefulness exceeds any single issue of life’s beginning, personhood, and any single normative ethical approach. Rather, the Bhaṭṭāraka draws attention to the karmic costs of existence, the role of indirect harms, and a reflection on the link between desires, aversions, and harm.

I conclude with a brief examination of in vitro fertilization (IVF), a reproductive technology (ART) introduced in the 1970s22 to treat infertility in women and men who cannot conceive in the womb. In IVF, a woman typically undertakes hormone injections to over-produce eggs that are then removed and fertilized with sperm in glass, or “in vitro.” The fertilized eggs develop to the blastocyst stage (5–6 days), where nascent embryos are evaluated for quality before one or more are transferred into the mother’s uterus in hopes of implantation.

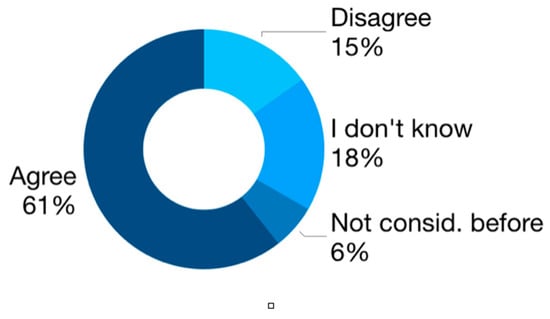

In his brief summary of Jain bioethics, Jain physician D. K. Bobra states that Jainism is indifferent to the method of procreation but more concerned that “children are the cause of attachments and aversions leading to [the] influx of karmas” (Bobra 2008). When presented with the survey statement, “I feel that humans have an ethical responsibility to control the human population by having fewer children” (n = 36), the majority of Jain medical professionals answered affirmatively (61%) (Figure 6). Likewise, The Jain Declaration on Nature—a document Jains presented to Prince Philip at Buckingham Palace in 1990—states that lay Jains “must not procreate indiscriminately lest they overburden the universe or its resources” (Singhvi 2002, pp. 223–24), demonstrating a concern for lives beyond one’s immediate desires or family unit.

Figure 6.

Survey question: “I feel that humans have an ethical responsibility to control the human population by having fewer children.” (n = 36).

Still, we do find instances in Jain literature when lay people benefit from reproductive creativity. The early Śvetāmbara text, the Kalpa-sūtra, actually describes the embryo of Mahāvīra transferred to the womb of another mother (KS 2.26–30). Jain medical texts also detail the ideal time for sex and foods to enhance virility. Yet nearly all birth stories, including those of the Tīrthaṅkaras, result in a child foregoing the bonds of marriage and parenthood to pursue the path of liberation.

Many contemporary lay Jain women feel that childbearing is crucial to their identity. In Whitney Kelting’s analysis of Jain wifehood in Maharastra, she found that many women feared infertility. Children offer emotional support, social status, and economic security in their later years (Kelting 2009, pp. 69–70). In communities where women join their husband’s household, a woman’s first child—especially a son—“mark[s] their full participation in their husband’s lineage” (p. 70). Conversely, Manisha Sethi’s research on Jain nuns revealed that many female mendicants valued their freedom from maternal roles (vairāgya) as “superior to and more fulfilling than anything that [householder] women were capable of achieving in marriage and family” (Sethi 2012, pp. 38–39).23

Feminist ethicist Susan Sherwin highlights a similar tension in philosophical bioethics between family and freedom, when she challenges the claim that IVF expands women’s reproductive independence. She points to social arrangements and values that drive women to take on the burden and risks of IVF, including women’s lack of access to meaningful jobs, a dearth of close friendships with men and women that necessitate intimacy with “one’s own” child, and persistent views that childbearing is a woman’s greatest purpose (Sherwin 2011, pp. 548–49). Likewise, a Jain ethics of carefulness that explores desires and motivations might examine social structures and expectations that shape ideals of motherhood and marriage, alongside conflicting goals of individual development and the aims of family and partnership.

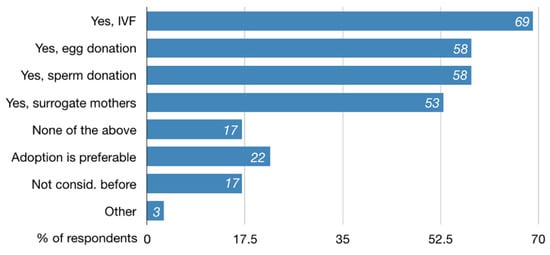

The majority of Jain medical professionals in our survey supported most assisted reproductive technologies, such as IVF (69%, n = 36), egg donation (58%), sperm donation (58%), and surrogate mothers (53%). A significant minority believed “none of the above” treatments was acceptable (17%), while others felt adoption was preferable (22%) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Survey question: “Do you feel that individuals or couples who cannot conceive naturally can ethically use reproductive technologies such as IVF, surrogacy, egg/sperm donation, or surrogate mothers? Choose all that apply.” (n = 36)

Bobra illuminates other collateral costs within IVF that might factor into an ethics of carefulness, including the exploitation of low-income egg donors or surrogate mothers who risk their bodies for financial stability, as well as sperm donors who might produce children they never know (Bobra 2008). Moreover, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control shows only 25% of all IVF cycles in 2016 resulted in live births (ART Success Rate 2016).24 Beyond failed pregnancies, excess embryos produced during IVF pose persistent questions of whether to destroy them, freeze them, or use them for embryonic stem cell research. Multi-fetal pregnancies are also more common with IVF25 and “selective fetal reduction” surgeries to remove excess or diseased fetuses remain a little-discussed cost of IVF treatment (Kulkarni 2013). One Jain author points out that IVF—even among Jains—appears to create life; however, access to pre-implantation selection disguises the destruction of embryos that are not “aborted” but, rather, “selectively transferred” based on viability, gender, or disease (Patel 2014, p. 243). A Jain ethics of carefulness could bring these unseen costs to the fore in bioethical debates, among Jains and non-Jains, along with the fact that physical and emotional desires, maternal norms, social pressures, and new biotechnologies lead to myriad relations of responsibility, from which we are not easily freed.

6. Conclusions

Although Jainism has been largely absent from bioethical discourses, its rich account of life, nonviolence, and contextual ethical response has much to offer in the discussion within and beyond the Jain community. Apramatta, or an ethics of carefulness, provides a rigorous applied framework rooted in the mendicant commitment to the restraints of ahiṃsā. The tools of carefulness require an orientation to ahiṃsā while making “ideological room” for the liberalization of medicine, so long as the action reflects a careful account of: (1) diverse living beings through multiple viewpoints; (2) motivations and aversions of thought, speech, and action; (3) harms we do directly, and those we require others to do on our behalf, or approve of through purchasing, silence, self-interest, institutional pressures, convenience, or inertia; as well as (4) continuous attempts to dial back harm in our given context. Although Jain medical and healthcare professionals offer a range of responses to ethical dilemmas in reproduction, examples of the above tools can be found within their survey responses, suggesting that a Jain ethics of carefulness might provide a lens for modern discourses between religion and bioethics. Ultimately, in a universe in which life itself has a cost, a Jain ethics of carefulness provides tangible tools for individuals and institutions, to seriously reflect on these costs to self and others, and seek out alternate modes of thought and action that actively reduce these harms whenever possible.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

ĀS [Ācārāṇga-sūtra]. 2008. Jaina Sutras, Part I & II. The Âkârâṅga Sûtra. Translated by Hermann Georg Jacobi. Forgotten Books. First published 1884.BhS [Bhagavatī-sūtra]. 1973. Bhagavati Sutra. Translated by K. C. Lalwani. Calcutta: Jain Bhavan.KS [Kalpa-sūtra]. 2008. Jaina Sutras, Part I & II. The Kalpa Sûtra. Translated by Hermann Georg Jacobi. Forgotten Books. First published 1884.PS [Pravacanasāra]. 1984. Śrῑ Kundakundācārya’s Pravacanasāra (Pavayaṇasāra). Translated by A. N. Upadhye. Agas: Parama-Śruta-Prabhāvaka Mandal, Shrimad Rajachandra Ashrama.SKS [Sūtrakṛtāṅga-sūtra]. Jaina Sutras, Part I & II. Sûtrakritâṅga. Translated by Hermann Georg Jacobi. Forgotten Books. First published 1884.Sth [Sthānāṅga-sūtra]. 2004. Illustrated Sthananga Sutra. Vol. 1. Translated by Surendra Bothra. Delhi: Padma Prakashan.TS [Tattvārtha-sūtra]. 2011. That Which Is. Translated by Nathmal Tatia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.US [Uttarādhyayana-sūtra]. 2008. Jaina Sutras, Part I & II. Uttarâdyayana. Translated by Hermann Georg Jacobi. Forgotten Books. First published 1884.YŚ [Yoga-Śastra]. 1989. The Yoga Shastra of Hemchandracharya. Translated by A. S. Gopani. A.S. Jaipur: Prakrit Bharti Academy. http://www.prakritbharati.net/books-online/yoga-shastra-hemachandracharya/000-00-table-contents/.Secondary Sources

- ART Success Rate. 2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/art/artdata/index.html (accessed on 16 May 2018).

- Auckland, Knut. 2016. The Scientization and Academization of Jainism. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 84: 192–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Marcus. 1991. Orthodoxy and Dissent: Varieties of Religious Belief among Immigrant Gujarati Jains in Britain. In The Assembly of Listeners: Jains in Society. Edited by Michael Carrithers and Caroline Hmphrey. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 241–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava, Dayanand. 1968. Jaina Ethics. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Bobra, Dilip K. 2008. Bio Medical Ethics in Jainism. Available online: http://www.herenow4u.net/index.php?id=66653 (accessed on 30 July 2015).

- Buswell, Robert E., and Donald S. Lopez Jr. 2014. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, Lisa Sowle. 2006. Theology’s Role in Public Bioethics. In Handbook of Bioethics and Religion. Edited by David E. Guinn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Caillat, Colette. 2018. On the Medical Doctrines in the Tandulaveyāliya: 1. Teachings of Embryology. Translated by Brianne Donaldson. International Journal of Jaina Studies 14: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Caring for the Jain Patient. n.d. Ashford Peters Health System. Available online: https://www.ashfordstpeters.info/images/other/PAS08.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Chapple, Christopher Key. 2002. Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cort, John. 2002. Green Jainism? Notes and Queries toward a Possible Jain Environmental Ethic. In Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life. Edited by Christopher Key Chapple. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, S. B. 1954. The History of Jaina Monachism from Inscriptions and Literature. Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute 16: 1–137. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, Brianne, and Ana Bajželj. 2019. Insistent Life: Foundations for Bioethics in Jainism, Lexington Books: forthcoming.

- Dundas, Paul. 2002. The Limits of a Jain Environmental Ethic. In Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life. Edited by Christopher Key Chapple. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, John H. 2006. Who Legitimately Speaks for Religion in Public Bioethics. In Handbook of Bioethics and Religion. Edited by David E. Guinn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Glasenapp, Helmuth von. 1942. Doctrine of Karman in Jain Philosophy. Translated by G. Barry Gifford. Bombay: Bai Vijibai Jivanlal Panalal Charity Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 1992. The Violence of Non-Violence: A Study of Some Jain Responses to Non-Jain Religious Practices. The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 15: 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 1998a. Cures and Karma: Attitudes Towards Healing in Medieval Jainism. In Self, soul and Body in Religious Experience. Edited by Albert I. Baumgarten. Leiden: Brill, pp. 218–56. [Google Scholar]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 1998b. Cures and Karma II: Some Miraculous Healings in the Indian Buddhist Story Tradition. Bulletin de l’Ecole Francaise d’Extrême-Orient 85: 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granoff, Phyllis. 2013. Between Monk and Layman: Paścātkṛta and the Care of the Sick in Jain Monastic Rules. In Buddhist and Jaina Studies: Proceedings of the Conference in Lumbini. Lumbini: Lumbini International Research Institute, pp. 229–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for Health Care Providers Interacting with Patients of the Jain Religion and Their Families. n.d. Metropolitan Chicago Healthcare Council. Available online: https://www.kyha.com/assets/docs/PreparednessDocs/cg-jain.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2018).

- Jain, Jyoti Prasad. 1950. Ugrāditya’s Kalyāṇakāraka and Ramagiri. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 13: 127–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Pankaj. 2010. Jainism, Dharma, and Environmental Ethics. Union Seminary Quarterly Review 63: 121–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. 2010. Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Kelting, M. Whitney. 2009. Heroic Wives: Rituals, Stories, and the Virtues of Jain Wifehood. Cambridge: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, Richard. 1999. Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India, and ‘The Mystic East’. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, Aniket D. 2013. Fertility treatments and multiple births. New England Journal of Medicine 369: 2218–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidlaw, James. 1995. Riches and Renunciation: Religion, Economy, and Society among the Jains. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Jeffery. 2009. Jainism: An Introduction. New York: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, Vibhuti. 2014. Sex Determination and Sex Pre-Selection Tests in India. In Global Bioethics and Human Rights: Contemporary Issues. Edited by Wanda Teays, John-Steward Gordon, Alison Dundes and Renteln. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 242–47. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, Dhanashri, Nitin Patel, Darshan Babu N., Umapati C. Baragi, and Gouda H. Pampanna. 2015. Kalyanakarakam: A Gem of Ayurveda. Ayushdhara 2: 141–49. [Google Scholar]

- Qvarnström, Olle. 2000. Stability and Adaptability: A Jain Strategy for Survival and Growth. In Jain Doctrine and Practice: Academic Perspectives. Edited by Joseph T. O’Connell. Toronto: University of Toronto, pp. 113–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, Aidan. 2018. Jainism and Environmental Philosophy: Karma and Web of Life. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Saddhatissa, Hammalawa. 1997. Buddhist Ethics. Somerville: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, Deepak. 2013. Jain Bioethics: Pontiff Charukeerthi Bhattaraka Sri Swamiji [Interview]. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-h-5tTX9R14 (accessed on 5 April 2013).

- SC Stays Rajasthan [High Court] Verdict Declaring Santhara Illegal. 2016. The Hindu. March 29. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/sc-stays-rajasthan-hc-verdict-declaring-santhara-illegal/article7599349.ece (accessed on 18 March 2019).

- Schubring, Walther. 2000. The Doctrine of the Jainas: Described after the Old Sources. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. First published 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, Manisha. 2012. Escaping the World: Women Renouncers among Jains. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sethia, Tara, ed. 2004. Ahiṃsā, Anekānta and Jainism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Bindi V. 2014. Religion in the Everyday Lives of Second-Generation Jains in Britain and the USA: Resources Offered by a Dharma-Based South Asian Religion for the Construction of Religious Biographies, and Negotiating Risk and Uncertainty in Late Modern Societies. The Sociological Review 62: 512–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, Susan. 2011. Feminist Ethics and In Vitro Fertilization. In Biomedical Ethics. Edited by David DeGrazia, Thomas A. Mappes and Jeffrey Brand-Ballard. New York: McGraw Hill, pp. 553–59. [Google Scholar]

- Singhvi, Laxmi Mall. 2002. The Jain Declaration on Nature. In Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life. Edited by Christopher Key Chapple. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 217–24. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, Mari Jyväsjärvi. 2014. Mendicants and Medicine: Āyurveda in Jain Monastic Texts. History of Science in South Asia 2: 63–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallely, Anne. 2002. From Liberation to Ecology: Ethical Discourses among Orthodox and Diaspora Jains. In Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life. Edited by Christopher Key Chapple. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles, Royce. 2006. The Dating of the Jaina Councils: Do Scholarly Presentations Reflect the Traditional Sources? In Studies in Jaina History and Culture: Disputes and Dialogues. Edited by Peter Flügel. New York: Routledge, pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, Kristi. 2009. The A to Z of Jainism. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Robert. 1991. Jaina Yoga: A Survey of the Mediaeval Śrāvakācāras. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Zysk, Kenneth. 1998. Asceticism and Healing in Ancient India: Medicine in the Buddhist Monastery. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | 1 The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1974–78) is generally viewed as the first national bioethics commission; it issued the foundational Belmont Report for consent in human subjects research; The Presidential Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1978–83) produced studies on foregoing life-sustaining treatment, and access to health care, among other topics. The 1981 report Defining Death was the basis of the Uniform Determination of Death Act, a model law that was enacted by most U.S. states. |

| 2 | See, for example Paul Ramsey, The Patient as Person: Explorations in Medical Ethics (Yale University Press 1977), Richard McCormick, How Brave a New World? Dilemmas in Bioethics (Georgetown University Press 1985) and Immanuel Jakobovits, Jewish Medical Ethics (Bloch Publishing Co. 1959/1975). |

| 3 | Tīrthaṅkaras are also called Jinas, meaning “victors,” who show the pathway of perception, knowledge, and action toward mokṣa; the name “Jain” derives from this latter term. |

| 4 | The dates of Mahāvīra’s birth and death vary; Śvetāmbara sources estimate 599-527 BCE; however Digambara sources believe Mahāvīra died in 510 BCE. More recently, scholars have adjusted the dates approximately 100 years later to coincide with the Buddha’s revised dating, i.e., 499-427 BCE (Dundas 2002, p. 24). |

| 5 | This mutuality, however, does not erase the differences. The Sūtrakṛtāṇga-sūtra states plainly that “householders are killers (of beings) and acquirers of property…They themselves kill movable and immovable living beings, have them killed by another person, or consent to another’s killing them” (SKS 2.1.43). |

| 6 | I served on the steering committee for the 2012 International Jain Bioethics Conference (24–25 August 2012), in Claremont, California, see Dilip Shah, “First Ever International Jain Bioethics Conference,” Institute of Jainology, https://www.jainology.org/jain-bioethics-conference/. See also, the 2017 National Seminar: Engaging Jainism With Modern Issues (24–26 February 2017) at Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, Ladnun (summary available at “BMIRC National Seminar” at HereNow4U, http://www.herenow4u.net/index.php?id=123357). |

| 7 | The Gyan Sagar Science Foundation (GSSF), for example, was started in 2009 by 41 founding Jain scientists in India for the purposes of “bridging science and society” (“Gyan Sagar” at HereNow4U, http://www.herenow4u.net/index.php?id=110933). In addition to a hosting annual conferences, GSSF has published a journal with relevant articles, and also co-sponsored the 18th Jaina Studies Workshop on Jainism and Science (2016) at the School of Oriental and Asian Studies (SOAS) in London. |

| 8 | For two examples of such healthcare guidelines in the U.K. and U.S., see (Caring for the Jain Patient n.d.) and (Guidelines for Health Care Providers Interacting with Patients of the Jain Religion and Their Families n.d.). |

| 9 | Anekāntavāda also describes the superior knowledge of the Tīrthaṅkaras who, having shed all deluding karma, possesses perfect perception of all contradictory truths in unison (SKS 1.6.28). |

| 10 | Banks describes the “neo-orthodox” tendency, alongside orthodox and heterodox tendencies, not as fixed groups but rather as three categories of informal belief that can overlap and shift within a given person (Banks 1991, pp. 244–57). |

| 11 | For details on alternate dates for this Council, see Royce Wiles (2006). |

| 12 | Deo identifies the acceptance of medicine within post-canonical commentaries on the Mūla-sūtras, referring to four “root texts” mendicants used at the start of their vocation (Deo 1954, pp. 29–33); Stuart examines three post-canonical commentaries: Niśītha-bhāṣya, Vyavahāra-bhāṣya, and Bṛhatkalpa-bhāṣya (6th–7th-century CE). |

| 13 | A small sampling of verses that reference the desires of mind, speech, and body include ĀS I.1.7.6, I.5.1.1–3, I.5.3.4, I.5.4.5, I.6.5.3–5. |

| 14 | A small sampling of verses that reference direct, indirect, and approved of harms include ĀS I.1.1.5, I.1.2.3, I.1.5.7, I.1.6.6, I.1.7.3, I.2.5.2, I.3.2.3. |

| 15 | evaṃ se appamāeṇa vivegaṃ keṭṭati veyavī. |

| 16 | See https://www.soas.ac.uk/ijjs/ (Caillat 2018). |

| 17 | Williams provides the Śvetāmbara list in a hierarchy of desirability as: trade, practice of medicine, agriculture, artisanal crafts, animal husbandry, service of a ruler, and begging. The Digambara list includes: trade, clerical occupations, agriculture, artisanal crafts, and military occupations (Williams 1991, p. 122). |

| 18 | Samiti is a -ti suffix noun formed from the prefix sam + verbal root √i (to go, come, continue, etc.), often referring to a “coming together” such as an association, council, group, etc. However, in the Jain tradition samiti refers to a series of five supportive rules that mendicants strive to adhere to as a supplement to the five “great vows” taken at ordination (mahā-vratas). Akin to apramatta, samiti vows require extreme care in: (1) walking (i), (2) speaking (bhāṣā-samiti), (3) accepting alms (eṣaṇā-samiti), (4) picking items up and setting items down (ādāna-nikṣepaṇa-samiti), and (5) performing excretory functions (utsarga-samiti). |

| 19 | The 13th and 14th stages describe the shedding of all karma, the full actualization of the jīva’s qualities. In a small twist of Jain cosmology, no liberation is actually possible in our current time cycle until the balance of ignorance and knowledge is regained so that moral decision is possible, which is estimated to be about 80,000 more years (Schubring [1962] 2000, pp. 225–26). |

| 20 | The authorship of the Śrāvaka-prajñāpti is uncertain; it was perhaps written by Umāsvāti or others (Williams 1991, p. 3). |

| 21 | The National Health Portal of India offers a hospital directory database at https://www.nhp.gov.in/directoryservices/hospitals. The number of Jain-sponsored hospitals was calculated by searching this directory using the keywords “Jain,” “Jaina,” “Mahavir” (including alternate spellings), and “Parshva(natha)” (including alternate spellings), arriving at a total of 213 facilities, though there are likely hospitals with Jain affiliations that were not included in this count. |

| 22 | 22 This history of IVF begins in the late 1800s with animal models in Europe. The first successful human procedure was completed by Patrick Steptoe and Robert Edwards when baby Louise Brown was born in the U.K. in 1978. |

| 23 | Sethi also describes commonalities that Jain nuns share in common with lay women, such as “male dominance, vulnerability to sexual and physical violence and so on” (Sethi 2012, p. 39). Sethi’s research describes how renunciation is still portrayed as an essential male pursuit, in spite of its recognition that women are equal participants in the Jain community and spiritual vision (p. 64). |

| 24 | 24 Based on CDC’s 2016 Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report, there were 263,577 ART cycles performed at 463 reporting clinics in the United States during 2016, resulting in 65,996 live births (deliveries of one or more living infants) and 76,930 live born infants. See ART Success Rate (2016). |

| 25 | While some countries permit only two embryos to be transferred during IVF—Canada, U.K., Australia, and New Zealand—The U.S. has no transfer limit. But after an increase in multi-fetal pregnancies through the 80s and late 90s, US medical associations offered a recommended limit rather than prohibition on transfers of 3 or more embryos which has reduced overall numbers. Still, twins or triplets increase the entanglement with children and resources. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).