1. Prolegomenon

This essay has been a journey of reflection, not simply of a favored motif in religious and secular art, but more personally with the re-emergence of several critical texts upon which much of my thinking has been developed over the years. Despite the scholarly vocation to be thorough both in research and in writing, every one of us stands upon the proverbial “shoulders of giants,” and oftentimes we have so assimilated or reinterpreted their ideas we believe they have become our own. Given the diversity of my scholarly proclivities which are grounded in multi-disciplinary studies of religious art and cultural history with emphases on symbolism and on the iconology of women, I have come to stand on the shoulders of more giants than most of my colleagues. This reality became apparent as I worked through my thinking for this present text, despite the fact that my primary point of entrée was as usual a careful viewing of an image, in particular, Vermeer’s painting of a woman reading.

Through this essay, readers will find references, both in my text and its footnotes, to several of those giants who have been with me, some simply through their books, others through personal encounters. None more significant for this present style of a reflection on a work of art and its effects upon a viewer than André Malraux

1 (1901–1976) whose own writings fused together the experience of art with the discriminating eye of a scholar. A writer who worked outside of the traditional boundaries of academic disciplines, Malraux gave us the vocabulary of the “museum without walls”

2 and of the significance of silence as a communicative mode for the observer engaged with a work of art.

Essential to this capacity for communication is composition, color, light, and form within the frame of the work of art.

3 This exchange can be identified as established through the aesthetic as the etymological foundation of this word is derived from the Greek αισθητικός. By providing an answer to the epistemological question of how we come to know—for we “come to know through the sense

s”—the aesthetic is more than an experience of or vision of the beautiful. The Greek root emphasizes the plurality of the human sense

s, not simply sight or touch, but all of the human senses uniting to transmit and/or to receive meaning and value.

Chief among the elements of form, especially in terms of the aesthetic dimension, is the human body, which expresses emotion and meaning through gesture, posture, position, and facial expression. Again, one of the key words associated with the human senses is haptic, which is derived from the Greek απτική, literally “sense of touch,” which I suggest can be expanded to the “emotive physicality of the human body,” especially in terms of the communicative potential of art (

Apostolos-Cappadona 1992). My exploration of the haptic dimension of the human body in the arts was influenced by the psychologist and composer Louis Danz (1897–1977), who wrote in his psychological study of Picasso’s art, “Picasso’s line is like Martha Graham’s dancing. Martha Graham, dances the path of feeling as it flows through her body. It flows through her body before it comes out.”

4 The artistic milieu that served as an additional support for this interpretation of the aesthetic and the haptic was established in the profound silence that both generates and inspires meditation and contemplation. However, this is not simply silence as an environment devoid of sound, but rather one empty of noise and dissonance. It is a realm of harmony and serenity that invites the observer into the quiet space manifested in a work of art and which allows for thought, reception, and response. This is as much as a sanctuary as it is a creative haven for introspection and spirituality. It is to paraphrase the feminist author Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) that “every woman needs a room of one’s own” (

Woolf 1929).

3. Women Readers in Christian Art and Cultural History

Like seeing, reading is a mediated practice that occurs within the cultural matrix that promotes the appropriate social mores of how to read, what to read, and who is able to read. Over the millennia of Western cultural history, books have been ambiguous symbols of power that have signified authorship, divine inspiration, wisdom, social position, and literacy. Traditionally for Christians, books can lead one to or away from salvation. In earliest Christian art, books signified the Christian message and were only seen in the hands of men. The books of classical authors such as Ovid or Homer, or worse yet, Plato or Aristotle, were deemed to be harmful to the Christian life, should not be read, and were forbidden to women. Therefore, the average Christian, especially female Christians, needed guidance in order to discern the appropriate nature and subject of reading and of books.

This led to the inauguration of a singular Christian form of literature—the advice manual—specifically prepared for Christian women and initiated by Jerome (347–420), best known as one of the church fathers, translator of the

Vulgate, and penitential saint. Given his proclivity to a male-dominated worldview, it is perhaps remarkable that Jerome advocated for female literacy as delineated in his “Letter to Eustochium:

The Virgin’s Profession” (

Jerome 1933a) and in his “Letter to Laeta:

A Girl’s Education” (

Jerome 1933b). It was for him an appropriate mode of Christian nurture as every mother should be able to read the Bible to her children. He compiled a careful reading list for Christian women. Similar advice manuals for women were authored by Christian theologians in the 15th and 16th centuries, particularly in Northern Europe, and again in the 19th century, especially in America.

5 Simultaneously, an iconography of women reading evolved from these theological advisories, and paralleled the history of women’s literacy within Western Christian culture. The dramatic division that has always existed between male readers and female readers was highlighted during the Reformation, when Protestant artists recorded the historical reality that readers were predominantly men of all ages, whereas only old women were depicted reading. Those women were relieved of the duties of childbearing and housekeeping, and thereby were “free” to meditate upon the scriptures as a form of spiritual preparation for death, such as those found in Gerard Dou’s Old Woman Reading a Lectionary (1631–1632: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) or as a form of spiritual instruction by their husbands as depicted in Rembrandt’s The Mennonite Preacher Anslo and His Wife (1641: Staatliche Museum, Berlin).

This iconography is both supported by our traditional assumptions about the Reformation as a literacy revolution, while questioning the presumption that only the upper classes, the elite, were literate. However, given what we believe to be the Protestant accent on literacy and the development of the moveable-type printing press, popular literacy could have become more of a reality from the 17th century forward. In principle, if not in fact, Protestantism advocated a literate laity who regularly studied the Bible as Dou’s old woman and Anslo’s wife did.

The magisterial art historian Leo Steinberg (1920–2011) documented the visual tradition of what he termed “engaged” readers in Western and secular art.

6 Engaged male readers dominated numerically over female readers as reading, Steinberg determined, was not a primary, or perhaps better said appropriate, activity for women. This was due in part because of society’s then-accepted gender distinctions between men and women as it did with the symbolism of the book and the meaning of reading.

Jerome advocated for women’s literacy, especially as a mode of Christian nurture for her children, and compiled a careful reading list for Christian women to follow throughout their lives. Among Jerome’s letters to women are two long and famous treatises on

A Girl’s Education in

Epistola 107 addressed to Laeta, Paula’s daughter-in-law and mother of her grandchild, Paila; and throughout the lengthy text of

Epistola 128 to Gaudentius’ daughter, Pacatila.

7 Both outlined educational programs that stressed an ascetic way of life and emphasized the importance of learning how to read and study Scripture. The letter to Laeta contained famous pedagogical advice; in other words, her education was designed to associate physical play, her bodily experiences, and her very identity of herself in history with her reading of Scripture. He considered education in letters much more essential for defining

who a woman will be rather than for determining what she will

do.

An effective and impassioned champion of women’s rights to read Scripture, his practice of dedicating 12 of his surviving 23 biblical commentaries to women departed radically from his Jewish and Christian predecessors. For example, in his

Commentary on Zephaniah, he inserts a long catalogue of heroic women drawn from the Hebrew Scriptures and from classical history.

8 His authority as a scriptural commentator and theologian began to establish a woman’s right to read while being linked to his understanding of their greater spiritual needs due to their weaker nature.

Further, these varied actions on Jerome’s part—especially his dedication of his texts to esteemed Christian women such as Paula, Eustochium, and others—had significance beyond the theological and the societal because it was neither deemed typical or appropriate to dedicate didactic works or serious religious literature to a lady. Thereby, Jerome departed from the customary ancient gift-giving or dedicatory practice in three meaningful ways: first, his willingness to instruct women in reading Scripture and learning what he considered to be the most important lesson in life, religious truth; second, in his preference for relationships and familial patterns based on spiritual rather than biological bonds; and third, in his confident assumption that the shared experience of reading and meditating on Scripture would create and renew these spiritual bonds linking himself, his chosen readers, and religious truth.

Reading, then, for Christian women was premised upon Jerome’s advice to Demetrias, “Love to occupy your mind with the reading of scripture,” especially as a mode of Christian nurture for her children.

9 Jerome’s admonition provided both a meticulous reading list and emphasized the care which must be taken “with a book in your hands.”

10 As both helpful and harmful, then, books played an ambiguous role in a Christian culture. Caution must be exerted as to who can create, control, hold, and

read books.

By the early medieval period, the symbolism of the book, and thus, of reading, entered into depictions of the Virgin Mary at the Annunciation. Whereas, the tradition of Byzantine iconography of the Annunciation, by contrast, represented the Theotokos holding a spindle or being engaged in the act of weaving the royal purple followed the text of the

Protoevangelion of James. This iconographic motif emphasized the visual analogies between the Annunciate Virgin and the virginal Athena who was the Greek goddess of wisdom and weaving.

11One of the early historians of women, Susan Groag Bell (1926–2015), studied the significance of medieval women book-owners as both commissioners and readers of books, particularly Books of Hours and, more significantly, the interior illuminations.

12 Bell established the introduction of the book into the iconography of the Annunciation scenes as contemporary to the development of the illustrations for Books of Hours commissioned by these women as early as the 11th century and more commonly beginning in the 12th century. This new medieval image of the Annunciate Virgin with a book, Bell indicates, not only gave these medieval women a sacred role model, it allowed their literacy to exist—for if Mary read at this most singular of moments in human history

then what medieval lady shouldn’t learn to read in imitation of Mary?

By the High Renaissance, the image of the Virgin with a book was commonplace as evidenced by Raphael’s

La belle jardinière (1507: Musée du Louvre, Paris) and Vittore Carpaccio,

The Virgin Reading (1510: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Nonetheless, in both of these paintings of the Virgin with a book, it is exactly that—the Virgin

with a book. Her attention is diverted from the act of reading, hers is as Steinberg has noted an interrupted reading. Women readers, he argued, through his three paradigms in western art of the Virgin Annunciate, the Magdalene in the Wilderness, and Francesca from Dante’s

Divina Commedia, were always interrupted by their domestic or marital (read sexual) duties, whereas male readers were protected from such interruptions by dutiful wives, mothers, or daughters. Therefore, women readers in Christian art, be they saints or sinners, were not exempt from interruptions as for example in depictions of Mary as a young mother rocking her son’s cradle as she reads, for example, in Martin Schongauer’s

The Holy Family (c. 1480/1490: Kunsthistoriches, Vienna) or Rembrandt’s

The Holy Family with Angels (1645: Hermitage, St. Petersburg).

13In early Christian art, as noted earlier, the persons depicted with books were predominately, if not solely, men. As an emblem, the book became associated with a diversity of female saints and heroines in the early medieval period. Nonetheless, St. Anne—the mother of the Virgin Mary and the grandmother of Jesus—was represented as a model of the ideal mother who either read to her daughter and/or her grandson, or was engaged in the activity of teaching her daughter and/or her grandson to read. For according to the then-common understanding, mothers were responsible for the early education of children as wives were for the edification of their husbands. This imagery originates and is most popular in 14th/15th century northern European painting.

Similarly, the iconography of the popular female saint Mary Magdalene as a reader developed in the 15th-century work and was related directly to the development of popular literacy, the medieval understanding of reading, and the lay spirituality of the Devotio Moderna and the Brotherhood of the Common Life. Reading was understood to be simultaneously as a spiritual nourishment and as a physical act. Ideally, an audience should assimilate a devotional text enthusiastically and comprehensively

This Magdalene motif emerged in the medieval period as her gesture, pose, and costume designate that the introduction of the symbolism of the book, and therefore of literacy, signified more than emblematic usage. The first representation of the motif of the Magdalene as reader is found in the work of the Flemish artist, Rogier van der Weyden (1400–1464) in the altarpiece fragment of

The Magdalene Reading (1436: The National Gallery, London).

14 Although the motif of a holy woman reading was not unknown by that date, there was no scriptural precedence for the Magdalene to be a reader as, similarly, there was no scriptural justification for the image of the Virgin Mary as a reader. Yet this motif, of the reading Virgin, which began as we now know from Bell’s research as early as the 12th century, flourished in the 14th and 15th centuries. Further Christian iconographic precedents were found in the iconographies of the virginal Saint Barbara and the scholarly Saint Catherine. So, one ponders why the motif of the reading Magdalene didn’t originate earlier and why it began in the 15th century at all?

The simplest solution to the latter question is that either Rogier van der Weyden’s patron’s wife was named Magdalene or Madeline, or that his patron(s) requested the inclusion of this image within the context of the larger altarpiece from which this fragment survives. However, such assumptions are only that and are much too simplistic for an artist as theologically complex and iconographically original as Rogier van der Weyden. So, we must delve deeper both into his own invention of visual motifs, and the cultural and religious milieu of his world. In this process, this painting is not considered as a singular presentation or invention of an image but within the context of what the British scholar of the social history of art Michael Baxandall (1933–2008) identified as the “period eye.”

15Recent studies in northern European art history have indicated two important factors for this study of the reading Magdalene. First of all is the central importance of individual Christian piety and devotionalism in the thematic presentations of 15th-century Flemish art. Although, northern art is often stereotyped as “cold” or “emotionless” in contrast to the more physically dynamic and passionate images of Italian art. However, the work of Rogier van der Weyden and his contemporaries communicated emotion and meaning through careful innovation in gesture and pose of the human body similar to my understanding of “the haptic.” This style of painting, like the contemplation and meditation advocated by the Devotio Moderna, demanded the viewer’s attention and required receptivity and response.

The northern European art historians Craig Harbison (1944–2018) and James H. Marrow (b. 1942) affirmed the extraordinary ties between Christian piety and devotionalism evidenced in 15th-century Flemish art (

Marrow 1986;

Harbison 1985). They saw this interconnection most clearly expressed by the artists who “found the means to visualize, subtly and fully, the chief religious ideal of the time, lay visions and meditations.” The visual norm became the quiet, simplicity of a devout Christian meditating upon a text until the image of that text became visible within the frame of the painting. Many 15th-century Flemish paintings and manuscript illuminations depicted this exact moment, that is, of a reader who reads in the fullest medieval sense of the term. Following the then-common metaphor of the book as food the reader needed to masticate, swallow, digest, and, by digesting, assimilate the meaning of the text which was visually signified by an excretion of the crucial visualization of the

meaning of the text. Thus, Rogier’s

The Magdalene Reading had both companions, and a religious and artistic context.

It was in fact this relationship between lay piety such as the Devotio Moderna and the rise of vernacular literature

16 that formed the cultural base for Rogier van der Weyden’s

The Magdalene Reading. Further, as Bell had promoted the importance of devotional texts such as Books of Hours for medieval women readers, more recent scholarship in medieval history has revealed among newly found records of medieval book ownership that devotional works were then most widely circulated among women. The purpose of these devotional books favored by women was within the guidelines established by Jerome to increase the religious fervor in the female reader and to instruct readers in the basic principles of the Christian faith.

Thus, the symbolism of women’s literacy was affirmed through images of saintly women from the Virgin Mary, Saint Anne, Saint Mary Magdalene, and Saint Barbara, to Saint Catherine with books. As societal roles for women changed in the ensuing European cultures, the symbol of the book once again became a prop, an object which characterized one as a woman of social position and, perhaps, of some education. However, the exceptions are found in the work of Vermeer.

4. Vermeer’s Women Readers: Reflections on Female Solitude and “Chinese Patience” in Secular Art17

Several centuries and transformed cultural contexts separate the visual evolution of women readers in medieval and Renaissance Christian art from their late 20th-century descendants in the art of the German painter Gerhard Richter (b. 1932) and the British photographer Tom Hunter (b. 1965). One of the foundations for the didactic authority of the visual image is its ability to repeat and reconstruct the commonly recognized masterpieces of earlier societies. Thus, an aura of both respectability and authority descended from one generation to another or from one cultural epoch to another.

While the motif of women readers has had an enduring presence in Western art, its evolution from a religious into a secular motif was bridged by the 17th-century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer, whose oeuvre included his most celebrated

tronie18 known as

Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665: Mauritshuis, The Hague). Both Richter’s

Reader (1994: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco) and Hunter’s

Woman Reading a Possession Order (1998: Victoria and Albert Museum, London) reflect the restrained emotion and contemplative ambiance found in the earlier iconology of Christian women readers, while incorporating significant elements of Vermeer’s works that focused the viewers’ attention on an exquisitely nuanced female subject and her thoughts about the text in her hands within a balanced composition that was filled with a soft, diffused atmosphere.

Although the modern perspective of Vermeer is almost one of reverence given the quality of his painting, during his lifetime and into the 19th century he was neither so well known nor his art so immediately recognized as it now has become. A result of both his deliberate style of painting and his early death in 1675, Vermeer’s oeuvre verges on the minimal. While as many as 60 or as few as 40 finished works may have survived into the 21st century, only 35 have been definitively attributed.

Little is known of his early life or his training as a painter. Less is known about his mature career as he had neither pupils or proteges, and the majority of his works were collected by a small circle of patrons in Delft. However, toward the end of the 19th century and early into the 20th, Vermeer’s carefully balanced compositions and his painterly preoccupation with the behavior of light brought him to the attention of a wider public, especially following the May 1921 exhibition of Dutch painting featuring his View of Delft (1660: Mauritshuis, The Hague) and Girl with a Pearl Earring that was on view at the Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume in Paris.

Marcel Proust (1871–1922) was then engaged in the writing of the sixth part (

The Captive) of his multivolume literary masterpiece

À la recherche du temps perdu. Published in several volumes between 1913 and 1927, Proust’s reflection on the passage of life and of time included a discussion of over one hundred artists. However, it was the affect and effect of Vermeer’s

View of Delft as an apprehension of the approaching death of the elderly writer Bergotte that continue to engage the memory of many readers. Often understood as an autobiographical passage, if not a premonition of Proust’s own last days, Bergotte’s last excursion was to see a display of the Vermeer paintings. Remarkably stunned by the Dutch painter’s art, Bergotte never ventured out again and remained apparently transfixed by the “

petit pan de mur jaune”

19 in the

View of Delft until his death.

No less dramatically, the British author Agatha Christie (1890–1976) had her perspicacious detective Hercule Poirot solve the murders of a brother and sister, and then identify an unknown Vermeer as the motive in her 1937 mystery

After the Funeral (1937). When the painter Cora Lansquenet is savagely murdered several days after her brother’s funeral, the family solicitor is concerned and calls upon his friend Poirot. The contents of the painter’s home are to be sold at auction, including her paintings; however, her companion Miss Gilchrist is allowed to keep a painting. She carefully selects a work that fools everyone except for Poirot, who recognizes that there is something amiss when he learns that the scene is derived from a postcard not from life, as was the artist’s inclination. He announces that the disguised painting which had been purchased at a jumble sale is in fact a Vermeer, had been painted over by Miss Gilchrist who recognized its value, and that the uncovered Vermeer would sell at auction for a sum that would have allowed Miss Gilchrist to return to her preferred life owning a tea shop.

20More recent authors, ironically both women, Tracy Chevalier (b. 1962) and Susan Vreeland (1946–2017) have also been inspired by Vermeer and expressly by his paintings of women. Chevalier credited her own decade-long fascination with a poster of Vermeer’s painting for the development of her 1995 bestselling novel

Girl with a Pearl Earring. This fictionalized narrative, which relates how Vermeer came to create a painting, was transformed into a 2003 film starring Colin Firth as Vermeer and Scarlet Johansson as the fictional household servant Griet.

21 The film was an eloquent adaptation of the novel’s major interpretation of Vermeer as an artist of light, color, and silence.

Vreeland’s 1999 novel was inspired not by her first-hand viewing of the extraordinary 1995 exhibition

Johannes Vermeer at the National Gallery of Art in Washington but, rather, by her extended encounter with the exhibition catalogue.

22 While a spectacular presentation, the exhibition was made famous by the simple fact that it had been scheduled to be on view from November 12, 1995, through February 11, 1996, during the unpredictable and unprecedented lengthy shutdowns of the US Government, which resulted in the National Gallery of Art being closed from December 16, 1995 until January 6, 1996. Lines of disappointed foreign visitors who had planned their travel months in advance to see this exhibition became fodder for the international media and Vermeer’s name was suddenly on everyone’s lips.

23However, Vreeland’s proverbially intimate encounter with Vermeer’s paintings, especially his female subjects like Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (c. 1657–1659: Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), Woman with a Pearl Necklace (c. 1662–1665: Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), and Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, came within the confines of her own domestic space. Thereby, Vreeland’s fictional recitation of her imaginary Vermeer painting and its travels through multiple centuries and owners was perhaps created from her own firsthand experiences as a woman reader engaged by the delicate balance of the images and words found throughout the “book in [sic.] her hands.”

Here we find what may be the critical elements to the appeal of both Vermeer’s art and his women readers: the social projection of intimate encounters between a woman and a book within the solitude of her own domestic environment. This artist was a master in both the creation of innovative scenes of everyday life and in imbuing them with emotional intensity. The interior of these homes can be characterized as expressions of an aura of privacy, comfort, and personal dignity. Predominately inhabited by women, either by the artist (or patron’s) preference or simply because the domestic environment was then identified as a “woman’s sphere,” the majority of Vermeer’s identifiable oeuvre can be described as soliloquies of female solitude.

His portrayals convey a magical immediacy as the viewer communes with the woman absorbed either in the act of reading or of writing a letter which the artist has subtly substituted for a book. By so doing, Vermeer has added a compelling emotion to the mystique of these paintings as any viewer recognizes the potential of a letter, especially one that demands intense scrutiny by its reader. So, the viewer empathetically wonders if this is a business transmittal, perhaps demanding an overdue payment, or is it more hopefully a love letter? If it is a billet-doux, then the viewer’s curiosity is engaged as to the authorial possibilities—is it from a lover? a husband? a fiancée? or simply from a family member or friend?

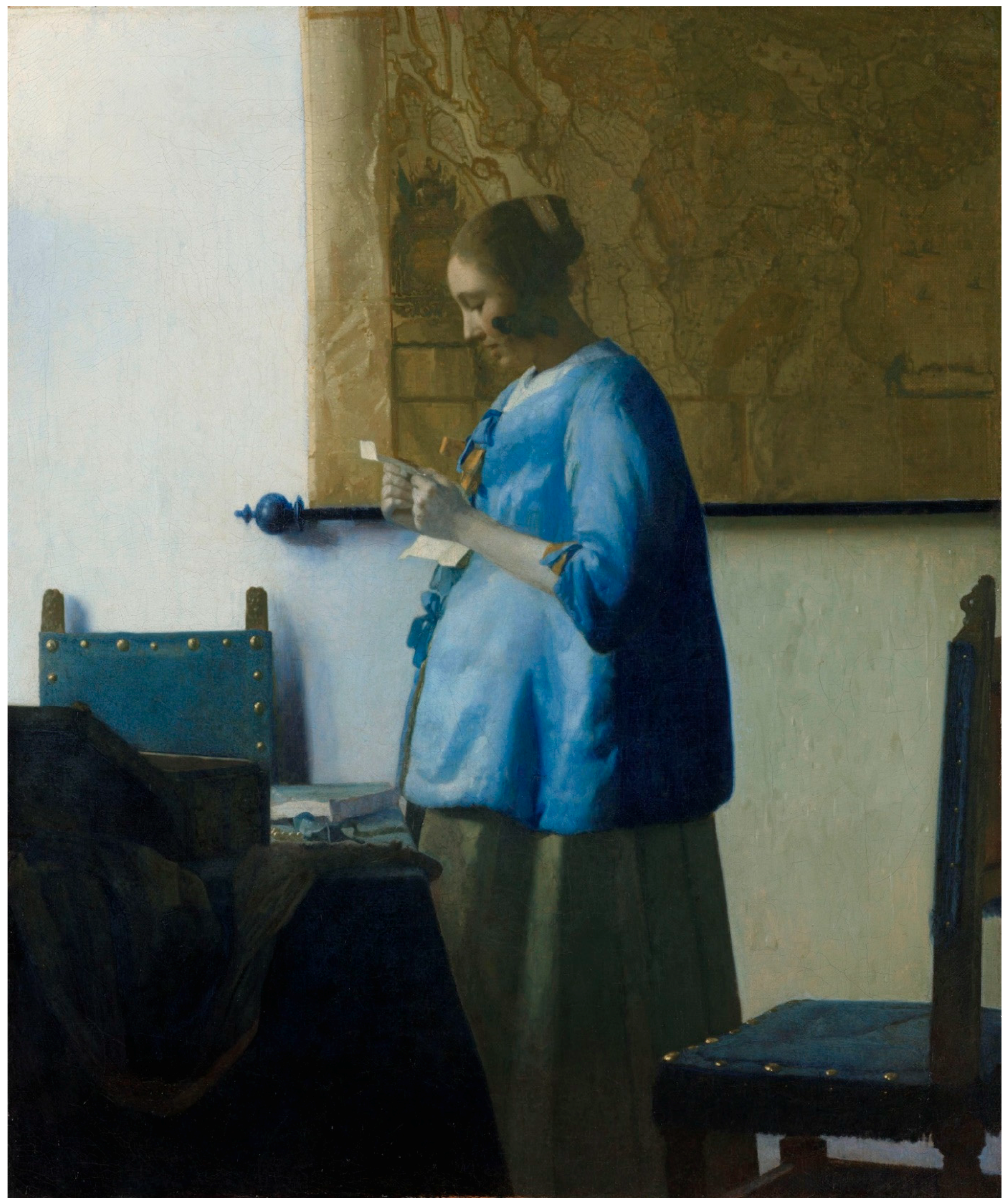

This artist has succeeded, perhaps unintentionally, in creating not merely a work of art but a spatial narrative for the empathetic viewer. The gestures and postures of Vermeer’s women readers (or writers) haptically conveyed an emotional intensity to the viewer and animate the domestic environment they occupy. If we consider his

Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (

Figure 1) as a normative example of Vermeer’s reading (and even of his writing) women, we come to recognize a variety of visual elements that both reflect his careful study of the behavior of and the symbolic possibilities of light, the formal relationships between color and human emotions, and his compassionate empathy with his subjects.

As a painter, Vermeer was intensely preoccupied with imbuing each picture with the world he was creating by means of his methodical working style, time-intensive in detail, and discriminating in the relationships among color, light, and subject. Further, he coordinated his images through naturalistic effects and harmoniously balanced compositions. Thus, the visual subtleties within his pictorial frame were highlighted by the soft blur of the foreground and often also the background as the central figures, especially of his reading (and writing) women, were represented in exacting detail and precise focus. His careful observation of a vanishing point usually between the woman’s face and the letter highlighted his central subject, like the woman reader dressed in a clear blue and mustard-yellow costume in Woman in Blue Reading a Letter. He further emphasized, at least for me, this reader’s power of introspection as representative of her intellectual capacities, even if the text in her hands is a billet-doux. For she holds the letter with reverence and is engaged in an intense, if silent, dialogue with its author.

This artist’s singular pattern of luminosity promotes the viewer’s receptivity of this quiet and mysterious domestic ambience in a painting like Woman in Blue Reading a Letter without initially recognizing that this space is closed off from the larger world. Despite the exchange of light and shadow, within the painting’s frame, there may be an implied window or an actual one as there are in other Vermeer’s depictions of reading and writing women, for example, Girl Reading a Letter at the Open Window or Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid (1670–1671: National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin), there is no exterior view to be seen, to complement the interior action, to identify the geographic location, or to provide a wider scope of “the real world.” Without a recognition of the outside world, either of a landscape, architecture, or personages, Vermeer accentuates his female subject’s privacy within her own enclosed space and thereby within her own narrative. Some scholars have commented that, in the works of Vermeer, this lack of an exterior view of the outside world indicated that such empty window is an obvious metaphor for engagement within this reader’s (or writer’s) interior world. This is the case, especially, for those interpreters with a religious or spiritual perspective who understand interiority as a projection of this woman’s soul. Enclosure, then, is not imprisonment, but rather a private and intimate environment that permits the solitude and silence fundamental to contemplation and introspection. Thus, the viewer recognizes that this artist provides both his subject and his audience with that delicate balance of mind and body essential for intellectual and spiritual activity.

Thereby, these women readers exist within their own unique space as they are absorbed within into a private world of poetic timelessness. A painter of subtle enigmas, Vermeer represents his women readers (and writers) engaged with their epistolary communications. He emphasizes this by positioning them either in profile with their faces turned downward as they concentrated on their tasks, or with their backs toward the viewer. Whenever visible, their faces are not individualized like portraits so that the communicative focus is more abstracted as the viewer becomes mesmerized by the evocation of tranquil solitude. Without the malice of the male gaze, Vermeer transports the viewer into the aura of an awestruck voyeur who is invited to share in this woman’s singular environment.